Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Development of Health Equity Indicators in Primary Health Care Organizations Using A Modified Delphi

Development of Health Equity Indicators in Primary Health Care Organizations Using A Modified Delphi

Uploaded by

jaime polancoCopyright:

Available Formats

You might also like

- Physical Medicine & Rehabilitation - Randall BraddomDocument1,482 pagesPhysical Medicine & Rehabilitation - Randall BraddomSimona Chirică90% (10)

- Whitepaper Spotlight On Regulatory Reforms in ChinaDocument15 pagesWhitepaper Spotlight On Regulatory Reforms in ChinaAlex PUNo ratings yet

- HIS 101 Compiled Notes 3Document10 pagesHIS 101 Compiled Notes 3Rey Ann ConcepcionNo ratings yet

- Stories of Special Children, Paknaan, Mandaue, CebuDocument21 pagesStories of Special Children, Paknaan, Mandaue, CebuErlinda Posadas100% (1)

- Benedict Lust LifeDocument8 pagesBenedict Lust Lifestormbrush100% (1)

- Plenary II SimpsonDocument41 pagesPlenary II Simpsonshekhar groverNo ratings yet

- Sister Blessing Project.Document41 pagesSister Blessing Project.ayanfeNo ratings yet

- Health Literacy: Applying Current Concepts To Improve Health Services and Reduce Health InequalitiesDocument10 pagesHealth Literacy: Applying Current Concepts To Improve Health Services and Reduce Health InequalitiesasriadiNo ratings yet

- Health Promotion Overview: Evidence-Based Strategies For Occupational Health Nursing PracticeDocument9 pagesHealth Promotion Overview: Evidence-Based Strategies For Occupational Health Nursing PracticeAdrîîana FdEzNo ratings yet

- Person-Centred Value-Based Health CareDocument58 pagesPerson-Centred Value-Based Health CarercabaNo ratings yet

- The Health Inequalities Assessment Toolkit: Supporting Integration of Equity Into Applied Health ResearchDocument6 pagesThe Health Inequalities Assessment Toolkit: Supporting Integration of Equity Into Applied Health ResearchAna Porroche-EscuderoNo ratings yet

- A Three-Stage Approach To Measuring Health Inequalities and InequitiesDocument13 pagesA Three-Stage Approach To Measuring Health Inequalities and Inequitiessean8phamNo ratings yet

- 2013-Evidence Based Public HealthDocument15 pages2013-Evidence Based Public HealthEric Yesaya TanNo ratings yet

- Public Preferences For Prioritizing Preventive and Curative Health Care Interventions - A Discrete Choice ExperimentDocument10 pagesPublic Preferences For Prioritizing Preventive and Curative Health Care Interventions - A Discrete Choice ExperimentTheDevchoudharyNo ratings yet

- Monitoring The Implementation of The WHO Global Code of Practice On The International Recruitment of Health Personnel: The Case of IndonesiaDocument63 pagesMonitoring The Implementation of The WHO Global Code of Practice On The International Recruitment of Health Personnel: The Case of IndonesiaFerry EfendiNo ratings yet

- Jurnal IPE B1.1Document15 pagesJurnal IPE B1.1fikri syafiqNo ratings yet

- Interprofessional Teamwork and Collaboration Between Community Health Workers and Healthcare Teams: An Integrative ReviewDocument9 pagesInterprofessional Teamwork and Collaboration Between Community Health Workers and Healthcare Teams: An Integrative ReviewNur HolilahNo ratings yet

- SAGE Open Medicine 2: 2050312114522618 © The Author(s) 2014 A Qualitative Study of Conceptual and Operational Definitions For Leaders inDocument21 pagesSAGE Open Medicine 2: 2050312114522618 © The Author(s) 2014 A Qualitative Study of Conceptual and Operational Definitions For Leaders inascarolineeNo ratings yet

- Ramalho 2019 - Plosone - q2Document20 pagesRamalho 2019 - Plosone - q2nanaloboNo ratings yet

- NQF Roadmap For Promoting Health Equity and Eliminating Disparities Sept 2017Document119 pagesNQF Roadmap For Promoting Health Equity and Eliminating Disparities Sept 2017iggybauNo ratings yet

- Evidence-Based Health Policy: A Preliminary Systematic ReviewDocument5 pagesEvidence-Based Health Policy: A Preliminary Systematic ReviewAndre LanzerNo ratings yet

- Distribution of Self-Reported Health in IndiaDocument18 pagesDistribution of Self-Reported Health in Indiasuchika.jnuNo ratings yet

- Health Affairs BMC Europe's Strong Primary Care Systems Are Linked To Better Population HealthDocument10 pagesHealth Affairs BMC Europe's Strong Primary Care Systems Are Linked To Better Population HealthgmantzaNo ratings yet

- Ebt Litreview CheriDocument8 pagesEbt Litreview Cheriapi-308965846No ratings yet

- Utility and Limitations of Measures of Health Inequities A Theoretical PerspectiveDocument9 pagesUtility and Limitations of Measures of Health Inequities A Theoretical PerspectiveStephanyNo ratings yet

- Journal Pone 0152866Document20 pagesJournal Pone 0152866yulya lasmitaNo ratings yet

- Weaver-2020-Perspective - Guidelines Needed For The Conduct of Human Nutrition Randomized Controlled TrialsDocument3 pagesWeaver-2020-Perspective - Guidelines Needed For The Conduct of Human Nutrition Randomized Controlled TrialsKun Aristiati SusiloretniNo ratings yet

- Social Science & Medicine: Mandy Ryan, Philip Kinghorn, Vikki A. Entwistle, Jill J. FrancisDocument10 pagesSocial Science & Medicine: Mandy Ryan, Philip Kinghorn, Vikki A. Entwistle, Jill J. FrancisAnis KhairunnisaNo ratings yet

- Health Facilities Roles in Measuring Progress of Universal Health CoverageDocument10 pagesHealth Facilities Roles in Measuring Progress of Universal Health CoverageIJPHSNo ratings yet

- Do Efforts To Standardize, Assess and ImproveDocument8 pagesDo Efforts To Standardize, Assess and ImproveWiwit VitaniaNo ratings yet

- Public Health Dissertation TitlesDocument7 pagesPublic Health Dissertation TitlesWriteMyPaperPleaseSingapore100% (1)

- A Framework To Measure The Impact of Investments in Health ResearchDocument16 pagesA Framework To Measure The Impact of Investments in Health ResearchGesler Pilvan SainNo ratings yet

- Awareness Of, Attitude Toward, and Willingness To Participate in Pay For Performance Programs Among Family Physicians A Cross-Sectional StudyDocument9 pagesAwareness Of, Attitude Toward, and Willingness To Participate in Pay For Performance Programs Among Family Physicians A Cross-Sectional StudySanny ChristianNo ratings yet

- Gha 9 29329Document19 pagesGha 9 29329Bahtiar AfandiNo ratings yet

- Jurnal PublikasiDocument29 pagesJurnal PublikasiLisana AzkiaNo ratings yet

- Evidence-Based Practice and The Quadruple AimDocument5 pagesEvidence-Based Practice and The Quadruple Aimmusule veronNo ratings yet

- Perceptions of Factors Associated With Inclusive Work and Learning Environments in Health Care Organizations A Qualitative Narrative AnalysisDocument14 pagesPerceptions of Factors Associated With Inclusive Work and Learning Environments in Health Care Organizations A Qualitative Narrative AnalysisAndrea Guerrero ZapataNo ratings yet

- Primary Health Care Literature ReviewDocument4 pagesPrimary Health Care Literature Reviewafdtbluwq100% (1)

- AJPH CHW Published Jul2013Document9 pagesAJPH CHW Published Jul2013anarobertoNo ratings yet

- Role of Institutions in Public Health EducationDocument5 pagesRole of Institutions in Public Health EducationDeepakNo ratings yet

- Decentralization and Health System Performance - A Focused Review of Dimensions, Difficulties, and Derivatives in IndiaDocument14 pagesDecentralization and Health System Performance - A Focused Review of Dimensions, Difficulties, and Derivatives in IndiaTriana Amaliah JayantiNo ratings yet

- Partnering Health Disparities Research With Quality Improvement Science in PediatricsDocument10 pagesPartnering Health Disparities Research With Quality Improvement Science in PediatricsPaul ReubenNo ratings yet

- Management of Health Organizations - Atefeh MoafianDocument16 pagesManagement of Health Organizations - Atefeh Moafiankhalesian.dkapNo ratings yet

- Leveraging Public Health Nursing To Build A 2014 American Journal of PreventDocument2 pagesLeveraging Public Health Nursing To Build A 2014 American Journal of Preventedi_wsNo ratings yet

- hsr2 254Document16 pageshsr2 254BarneyNo ratings yet

- Practice Size, Financial Sharing and Quality of Care: Researcharticle Open AccessDocument9 pagesPractice Size, Financial Sharing and Quality of Care: Researcharticle Open AccessIndah ShofiyahNo ratings yet

- From Fringe To Centre Stage: Experiences of Mainstreaming Health Equity in A Health Research CollaborationDocument14 pagesFrom Fringe To Centre Stage: Experiences of Mainstreaming Health Equity in A Health Research CollaborationAna Porroche-EscuderoNo ratings yet

- Fisher 2017Document6 pagesFisher 2017Bogdan NeamtuNo ratings yet

- Lmih Rethinking Health Systems StrengtheningDocument8 pagesLmih Rethinking Health Systems StrengtheningArap KimalaNo ratings yet

- Ngos and Government Partnership For Health Systems Strengthening: A Qualitative Study Presenting Viewpoints of Government, Ngos and Donors in PakistanDocument8 pagesNgos and Government Partnership For Health Systems Strengthening: A Qualitative Study Presenting Viewpoints of Government, Ngos and Donors in PakistanGummie Akalal SugalaNo ratings yet

- Review Jurnal Pembiayaan Kesehatan 2Document5 pagesReview Jurnal Pembiayaan Kesehatan 2SUCI PERMATANo ratings yet

- MPH Question 2Document30 pagesMPH Question 2al azar bitNo ratings yet

- Aminu Magaji T-PDocument27 pagesAminu Magaji T-PUsman Ahmad TijjaniNo ratings yet

- Kapil Research OutlineDocument14 pagesKapil Research OutlineLunkaran ChordiyaNo ratings yet

- Role of Health Surveys in National Health Information Systems: Best-Use ScenariosDocument28 pagesRole of Health Surveys in National Health Information Systems: Best-Use ScenariosazfarNo ratings yet

- DiabetesDocument6 pagesDiabetesAyin FajarNo ratings yet

- Patient Empowerment BMC Health Services Research2012Document8 pagesPatient Empowerment BMC Health Services Research2012Constantino SantosNo ratings yet

- Sdi 5294 KumarDocument20 pagesSdi 5294 KumarBharatKumarMaheshwariNo ratings yet

- Community Health Nursing UpdatesDocument6 pagesCommunity Health Nursing UpdatesLoyloy D ManNo ratings yet

- The Role of Quality Improvement in Strengthening HDocument8 pagesThe Role of Quality Improvement in Strengthening Hmikhail.gio.balisiNo ratings yet

- A Preliminary Study On Applying Holistic Health Care Model On Medical Education Behavioral Intention: A Theoretical Perspective of Planned BehaviorDocument7 pagesA Preliminary Study On Applying Holistic Health Care Model On Medical Education Behavioral Intention: A Theoretical Perspective of Planned BehaviorJean o LeraNo ratings yet

- MZQ 028Document7 pagesMZQ 028eliamusa981No ratings yet

- Hca622 Quality Improvement Edsan RevDocument6 pagesHca622 Quality Improvement Edsan Revapi-326980878No ratings yet

- Efficacy, Effectiveness And Efficiency In The Management Of Health SystemsFrom EverandEfficacy, Effectiveness And Efficiency In The Management Of Health SystemsNo ratings yet

- Manual Series REM V1.0 2018Document322 pagesManual Series REM V1.0 2018jaime polancoNo ratings yet

- Jaime Polanco Control8Document4 pagesJaime Polanco Control8jaime polancoNo ratings yet

- Art15 PDFDocument7 pagesArt15 PDFjaime polancoNo ratings yet

- The Road To High Performance Is Paved With Data: Jeffry G. JamesDocument4 pagesThe Road To High Performance Is Paved With Data: Jeffry G. Jamesjaime polancoNo ratings yet

- Jaime Polanco Control6..Document6 pagesJaime Polanco Control6..jaime polancoNo ratings yet

- 2015 - Article - 46 n3Document8 pages2015 - Article - 46 n3jaime polancoNo ratings yet

- Bases Coneo 2016Document49 pagesBases Coneo 2016jaime polancoNo ratings yet

- El Plan AUGE: 2005 Al 2009: Health Care Reform in Chile: 2005 To 2009Document7 pagesEl Plan AUGE: 2005 Al 2009: Health Care Reform in Chile: 2005 To 2009jaime polancoNo ratings yet

- At Issue: Cochrane, Early Intervention, and Mental Health Reform: Analysis, Paralysis, or Evidence-Informed Progress?Document4 pagesAt Issue: Cochrane, Early Intervention, and Mental Health Reform: Analysis, Paralysis, or Evidence-Informed Progress?jaime polancoNo ratings yet

- Hospital Management Autonomy in Chile: The Challenges For Human Resources in HealthDocument5 pagesHospital Management Autonomy in Chile: The Challenges For Human Resources in Healthjaime polancoNo ratings yet

- Ethical Challenges For Accountable Care Organizations: A Structured ReviewDocument8 pagesEthical Challenges For Accountable Care Organizations: A Structured Reviewjaime polancoNo ratings yet

- Pmed.1001676 n2Document3 pagesPmed.1001676 n2jaime polancoNo ratings yet

- The Quest For Equity in Latin America: A Comparative Analysis of The Health Care Reforms in Brazil and ColombiaDocument16 pagesThe Quest For Equity in Latin America: A Comparative Analysis of The Health Care Reforms in Brazil and Colombiajaime polancoNo ratings yet

- Healthcare Reform: Implications For Knowledge Translation in Primary CareDocument11 pagesHealthcare Reform: Implications For Knowledge Translation in Primary Carejaime polancoNo ratings yet

- Making Sense of Joint Commissioning: Three Discourses of Prevention, Empowerment and EfficiencyDocument10 pagesMaking Sense of Joint Commissioning: Three Discourses of Prevention, Empowerment and Efficiencyjaime polancoNo ratings yet

- Group Case Study - Pulmonary TBDocument8 pagesGroup Case Study - Pulmonary TBCj NiñalNo ratings yet

- Letter of ApplicationDocument4 pagesLetter of Applicationmelai_0123No ratings yet

- An Evaluation of Four Decades of Cuban Healthcare: Felipe Eduardo SixtoDocument19 pagesAn Evaluation of Four Decades of Cuban Healthcare: Felipe Eduardo SixtoAvicenna AkbarNo ratings yet

- Quiz - Medical TollsDocument27 pagesQuiz - Medical TollsANTIKA NABILA TOBINGNo ratings yet

- DocumentsDocument118 pagesDocumentsaamirbinrashid.2No ratings yet

- Drug AbuseDocument18 pagesDrug AbuseMark Anthony MaquilingNo ratings yet

- Govt. College of Nursing, Bilaspur (C.G.) Case Study Evaluation FormatDocument2 pagesGovt. College of Nursing, Bilaspur (C.G.) Case Study Evaluation FormatDivya ToppoNo ratings yet

- Plan of ActivitiesDocument3 pagesPlan of ActivitiesLiiza G-GsprNo ratings yet

- Presentation1 of OSCE-OSPEDocument10 pagesPresentation1 of OSCE-OSPETiku SahuNo ratings yet

- Professional Practice Manual-PN-2022-23Document110 pagesProfessional Practice Manual-PN-2022-23pham vanNo ratings yet

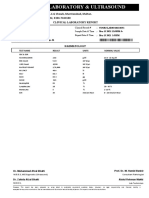

- Noor Laboratory & UltrasoundDocument1 pageNoor Laboratory & UltrasoundZahid BhattiNo ratings yet

- Acute Pain Related To Tissue Trauma and InjuryDocument4 pagesAcute Pain Related To Tissue Trauma and Injuryprickybiik50% (2)

- Arab HealthDocument316 pagesArab HealthMunir AldeekNo ratings yet

- Introduction To MidwiferyDocument27 pagesIntroduction To MidwiferySHOWMAN DEEPAK100% (2)

- Skill Matrix Tech TeamDocument2 pagesSkill Matrix Tech TeamDelfia RahmadhaniiNo ratings yet

- A Concept Analysis of Effective Breastfeeding: in ReviewDocument8 pagesA Concept Analysis of Effective Breastfeeding: in ReviewJumasing MasingNo ratings yet

- Ikmal CVDocument6 pagesIkmal CVshahrilzainul77No ratings yet

- Waldenstrom MacroglobulinemiaDocument11 pagesWaldenstrom MacroglobulinemiaMr. LNo ratings yet

- Exam Bulletin 2015Document2 pagesExam Bulletin 2015wiltechworksNo ratings yet

- Reflections DR PG RamanDocument213 pagesReflections DR PG RamanAbiola Williams Smith100% (1)

- Tieken CV 2023Document5 pagesTieken CV 2023api-568999633No ratings yet

- Safety ProgramDocument24 pagesSafety ProgramJuan CruzNo ratings yet

- Recall of KN95 RespiratorsDocument2 pagesRecall of KN95 RespiratorsRadio-CanadaNo ratings yet

- New Jersey Takes Action Against Unlicensed Medical Spas Practicing Botox and Vampire FacialsDocument2 pagesNew Jersey Takes Action Against Unlicensed Medical Spas Practicing Botox and Vampire FacialsranggaNo ratings yet

- International Student Guide: WWW - Tuas.fiDocument36 pagesInternational Student Guide: WWW - Tuas.fifrederic_tranchandNo ratings yet

- Basic Pharma Inc.: ZOLESTAT Discount Card MD's TM: Ritchelle Naconas Area: South DavaoDocument4 pagesBasic Pharma Inc.: ZOLESTAT Discount Card MD's TM: Ritchelle Naconas Area: South DavaoMaryshelle AlvarezNo ratings yet

Development of Health Equity Indicators in Primary Health Care Organizations Using A Modified Delphi

Development of Health Equity Indicators in Primary Health Care Organizations Using A Modified Delphi

Uploaded by

jaime polancoOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Development of Health Equity Indicators in Primary Health Care Organizations Using A Modified Delphi

Development of Health Equity Indicators in Primary Health Care Organizations Using A Modified Delphi

Uploaded by

jaime polancoCopyright:

Available Formats

RESEARCH ARTICLE

Development of Health Equity Indicators

in Primary Health Care Organizations

Using a Modified Delphi

Sabrina T. Wong1,2*, Annette J. Browne1, Colleen Varcoe1, Josee Lavoie3,4, Alycia

Fridkin1, Victoria Smye1,5, Olive Godwin6, David Tu7

1. Critical Research in Health and Healthcare Inequities Unit, School of Nursing, University of British

Columbia, Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada, 2. Centre for Health Services and Policy Research,

University of British Columbia, Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada, 3. Manitoba First Nations Centre for

Aboriginal Health Research, University of Manitoba, Winnipeg, Manitoba, Canada, 4. Community Health

Sciences, Faculty of Medicine, University of Manitoba, Winnipeg, Manitoba, Canada, 5. University of Ontario

Institute of Technology, Oshawa, Ontario, Canada, 6. Prince George Division of Family Practice, Prince

George, British Columbia, Canada, 7. Department of Family Practice, Faculty of Medicine, University of British

Columbia, Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada

*Sabrina.wong@nursing.ubc.ca

OPEN ACCESS

Citation: Wong ST, Browne AJ, Varcoe C, Lavoie

J, Fridkin A, et al. (2014) Development of Health

Equity Indicators in Primary Health Care Abstract

Organizations Using a Modified Delphi. PLoS

ONE 9(12): e114563. doi:10.1371/journal.pone. Objective: The purpose of this study was to develop a core set of indicators that

0114563

could be used for measuring and monitoring the performance of primary health care

Editor: Koustuv Dalal, Orebro University, Sweden

organizations capacity and strategies for enhancing equity-oriented care.

Received: July 2, 2014

Methods: Indicators were constructed based on a review of the literature and a

Accepted: November 5, 2014

thematic analysis of interview data with patients and staff (n5114) using

Published: December 5, 2014

procedures for qualitatively derived data. We used a modified Delphi process where

Copyright: 2014 Wong et al. This is an open- the indicators were circulated to staff at the Health Centers who served as

access article distributed under the terms of the

Creative Commons Attribution License, which participants (n563) over two rounds. Indicators were considered part of a priority

permits unrestricted use, distribution, and repro-

duction in any medium, provided the original author set of health equity indicators if they received an overall importance rating of.8.0,

and source are credited. on a scale of 19, where a higher score meant more importance.

Data Availability: The authors confirm that all data Results: Seventeen indicators make up the priority set. Items were eliminated

underlying the findings are fully available without

restriction. The data from the modified delphi because they were rated as low importance (,8.0) in both rounds and were either

process for this study are available upon request redundant or more than one participant commented that taking action on the

from Dr. Annette Browne, the nominated principal

investigator for this study, due to ethical restric- indicator was highly unlikely. In order to achieve health care equity, performance at

tions. Any requests for these data can be directed

to Dr. Browne. She can be reached at:

the organizational level is as important as assessing the performance of staff. Two

Annette.browne@nursing.ubc.ca. of the highest rated treatment or processes of care indicators reflects the need for

Funding: This study was funded by the Canadian culturally safe and trauma and violence-informed care. There are four indicators

Institutes for Health Research #173182. The

funders had no role in study design, data collection that can be used to measure outcomes which can be directly attributable to equity

and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of responsive primary health care.

the manuscript.

Discussion: These indicators and subsequent development of items can be used

Competing Interests: The authors have declared

that no competing interests exist. to measure equity in the domains of treatment and outcomes. These areas

PLOS ONE | DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0114563 December 5, 2014 1 / 15

Health Equity Indicators in Primary Health Care

represent targets for higher performance in relation to equity for organizations (e.g.,

funding allocations to ongoing training in equity-oriented care provision) and

providers (e.g., reflexive practice, skill in working with the health effects of trauma).

Introduction

Achieving equity in health care is an important goal of most primary health care

(PHC) system reforms. Primary health care plays an important role in reducing

health inequity [1]. The World Health Organization (WHO) suggests one of the

most efficient ways of closing the equity gap is to address the health and health

care needs of those most disadvantaged [2]. International evidence continues to

accumulate, showing that enhancement of PHC services for those who are made

vulnerable by intersecting determinants of health is a critical way in which to

reduce health and health care inequities [35].

Despite extensive reforms and investments in PHC systems across Canada [6]

and abroad [7], measuring equity in health care settings remains challenging.

There are at least two challenges that have impeded progress on measuring equity.

First, there is a lack of consensus on the conceptualization of health equity and

inequity [8]. Second, current PHC indicators and measures do not reflect

important work that organizations do to provide PHC services to groups most

affected by structural inequities [9].

This research is predicated on the importance of distinguishing between

equality and equity. Health equity is defined as the absence of systematic and

potentially remediable differences in one or more characteristics of health across

populations or population groups defined socially, economically, demographi-

cally, or geographically [10, 11]. Whereas equal health care means equal access,

treatment, and treatment outcomes for people in equal need [7]. These

distinctions are important in developing equity-oriented indicators, given the

widening inequities in health and social status in Canada and other nations.

Broadly, equity has been conceptualized as either horizontal (equal treatment

for individuals/groups with similar levels of health care need) or vertical (different

individuals/groups should be treated differently according to their health care

need) [8]. While the delivery of PHC services may be aimed at addressing both

horizontal and vertical equity, it is not straightforward for any one provider, or

practice/organization to operationalize these concepts in everyday practice. Most

practices and measures of their performance are aimed at positively impacting

horizontal equity without attention to vertical inequity. This is inadequate

because, for example, research suggests that 20%25% of patients in a practice

waiting room or in a typical general physician (GP) practice will fit the criteria for

marginalized populations.. That is, all primary care practices will have some

patients who have complex intersecting health and social problems that result

from the inequitable distribution of wealth and/or underlying structural inequities

PLOS ONE | DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0114563 December 5, 2014 2 / 15

Health Equity Indicators in Primary Health Care

related to systemic racism/racialization, colonialism and patriarchy. These patients

are most likely to suffer negative health effects. Yet, these practices may not have

the available resources, or access to the types of interdisciplinary teams that would

be required to more adequately address the needs of the patients most affected by

structural inequities. Other practices are focused on addressing vertical equity for

more marginalized groups (e.g., inner city populations living with HIV/AIDS,

elderly patients, patients with major mental health issues) but are not able to

address horizontal equity that is limited resources mean that all patients with

similar needs will not be able to receive similar care.

Indicators to monitor and measure health care inequities are required within

the three broad areas where inequities in PHC may arise: access, treatment, and

outcomes. To date, currently available PHC indicators fall short of providing

information about health equity, particularly in relation to marginalized

populations [12]. These currently available indicators, while reflecting the various

dimensions of PHC, are primarily useful to monitoring and measuring horizontal

equity.

For example, using existing measures, it is possible to examine access to care to

detect any unequal treatment by gender or age.

However, there are virtually no PHC indicators that focus attention on vertical

equity. For examples, it is not possible to detect treatment inequities such as

collaborating with other health departments, organizations and social service

agencies regarding how to tailor services, programs and approaches to better meet

the needs of marginalized populations (e.g., with emergency departments,

pharmacies, hospital units, walk in clinics, shelters, etc.). That is, indicators such

as access to care and adherence to current clinical guidelines about treatment and

outcomes are most reflective of horizontal equity, also known as equality. These

kinds of indicators do not reflect the essential work of relationship building and

tailoring of care that is often the focus of PHCs organizations serving groups most

affected by structural inequities; This is fundamental to capture PHC organiza-

tions capacity to be optimally responsive and respectful when working with

marginalized populations [9]. The purpose of this study was to develop a

proposed core set of health care equity indicators to be used in PHC. These

indicators are designed for measuring and monitoring and performance of PHC

practices/organizations capacities in enhancing the equity-orientation of the care

and services provided.

Methods

The development and identification of a set of priority health care equity

indicators was derived as part of a large study which sought to: (a) examine how

PHC services are provided to meet the needs of people who have been

marginalized by systemic inequities, (b) identify the key dimensions of PHC

services for marginalized populations, and (c) develop PHC indicators to account

for the quality, process, and outcomes of care when marginalized populations are

PLOS ONE | DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0114563 December 5, 2014 3 / 15

Health Equity Indicators in Primary Health Care

explicitly targeted [5]. This study used a mixed methods ethnographic design and

was conducted in partnership with two Urban Aboriginal Health Centers (herein

called Health Centers) located in two different inner cities in Canada.

Data sources to construct the indicators

More in-depth information about the Health Centers and data collection methods

can be found elsewhere [5, 9]. Briefly, both Health Centers have an explicit

mandate to provide health care for Aboriginal people residing in low-income

inner city neighborhoods, and to make their services as accessible as possible to

both Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal people experiencing complex, intersecting

social and health issues. Many of the patients live on less than $1,000 Canadian

dollars (CDN) per month (well below Canadas poverty lines), reside in unstable

or unsafe housing, and experience high rates of trauma and interpersonal and

structural violence in their everyday lives. Structural violence is increasingly seen

in PHC and population health research as a major determinant of the distribution

and outcome of health inequities, and is defined as a host of offensives against

human dignity, including extreme and relative poverty, social inequalities ranging

from racism to gender inequality, and the more spectacular forms of violence

[13], p.8. For example, the well-recognized negative health effects of poverty

intersect with multiple other disadvantages, such as stigma and discrimination

related to mental illness, problematic substance use, and other health conditions.

Research continues to show that people affected by structural inequities, trauma

and violence have higher rates of poor health, including chronic pain and other

chronic illnesses, and higher rates of emergency department visits and preventable

hospital admissions.[1416]

Three sets of data were collected for the larger study, including: (a) participant

observation data collected during intensive immersion in the Health Centers (over

900 hours), and (b) in-depth interviews conducted with a total of 114 patients

and staff, including: (i) individual interviews with 33 staff, and an additional eight

staff who participated in focus groups (n541 staff), and (ii) individual interviews

with 62 patients, and three focus groups with 11 patients (n573 patients).

All data were audio-recorded, transcribed, and anonymized for analysis. All

participants provided signed informed consent. This studys procedures,

including the consent process, were approved by the appropriate ethics

institutional review boards (University of British Columbia and University of

Northern British Columbia) and Memorandums of Understanding were signed

between the Health Centers and the research team.

Initial construction of the health equity indicators

Indicators were constructed based on a review of the literature and a thematic

analysis of the interview data using procedures for qualitatively derived data [17

19]. Interview transcripts and observational notes were repeatedly read by the

members of the research team to identify patterns and themes reflected in the

PLOS ONE | DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0114563 December 5, 2014 4 / 15

Health Equity Indicators in Primary Health Care

data. NVivo [20] was used to organize and code the narrative data. Through the

process of data analysis, we identified (a) four key dimensions of equity-oriented

PHC services, which are particularly relevant when working with marginalized

populations, (b) 10 strategies to guide organizations to enhance their capacity for

equity-oriented services, and (c) a list of short and long terms outcomes related to

these dimensions and strategies [5].

These key dimensions of equity-oriented PHC services include: 1) inequity-

responsive care, addressing social determinants of health as legitimate and routine

aspects of health care; 2) trauma and violence informed care, that is, care that

consists of respectful, trusting and affirming practices informed by understanding

the pervasiveness and effects of trauma and violence; 3) contextually-tailored care,

meaning the tailoring of services in ways that meet the needs of specific

populations within local contexts; and 4) culturally-competent and culturally safe

care, meaning attending to the cultural meanings people ascribe to health and

illness and seriously taking into account their experiences of racism, discrimina-

tion and marginalization [5]. Importantly, trauma- and violence informed care

requires all staff in an organization, inclusive of receptionists, direct care providers

and management, to understand the intersecting health effects of trauma,

structural and individual violence, and other forms of inequity, so that health care

encounters are affirming, and the possibility of re-traumatization is reduced.

Trauma- and violence informed care is not about eliciting trauma histories; rather

it is about creating a safe environment based on an understanding of trauma

effects. These four key dimensions provided the conceptual groundwork for the

development of the health equity indicators. Our construction of the health equity

indicators was also informed by our analysis of the publicly available, extant pan-

Canadian PHC indicators (e.g. Canadian Institute for Health Information Pan-

Canadian PHC Indicators Health Indicators Project: Report from the Third

Consensus Conference on Health Indicators [12]), which have identified

indicators that reflect dimensions of PHC such as accessibility, comprehensive-

ness, continuity, and interpersonal communication, but which have not explicitly

been developed using an equity lens. Importantly, the health equity indicators

reported in this paper were constructed to be complimentary to existing

indicators of PHC, particularly those developed in Canada.

In identifying the key dimensions of equity-oriented PHC, credibility of our

analysis was continuously evaluated by members of the research team, including

the researchers, Health Centre (providers and staff members), and a community

advisory committee comprising patient and health care representatives [5]. Rigor

and trustworthiness of the analysis [5] came from triangulation of observational,

patient, and staff data.

Participants of the Modified Delphi

All Health Centre staff were invited to participate in reviewing and rating the

importance of the indicators on a nine point Likert scale. A total of 63 staff

participated in at least one of the two Delphi rounds, 14 of whom participated in

PLOS ONE | DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0114563 December 5, 2014 5 / 15

Health Equity Indicators in Primary Health Care

both rounds. The number of Health Centre staff respondents in Rounds 1 and 2

was 36 and 27, respectively. Between Rounds one and two, patients were asked to

provide comments on the indicators. The number of patient respondents was 19

and 14 in groups at each Health Center.

Procedures

The Delphi consists of a written consensus process where documents are

circulated to a group of experts [21]. We used a modified Delphi process where

the indicators were circulated to staff over two rounds. We assumed indicators

ought to be considered part of a priority set of health equity indicators if they

received an overall importance rating of$8.0 out of 9.

We considered this a modified Delphi process because it was tailored to each

Health Centre based on their preferences. In one Health Centre, data were

collected through an online survey whereas the other Health Centre preferred to

complete their ratings of the indicators using pen and pencil in conjunction with a

staff meeting in which the researchers were invited to provide an update on the

larger study. In each round, staff participants were asked to rate the importance of

each indicator and modify them if necessary. Importance of the indicator was

defined as: (a) an important way of measuring the services so that Health

Authorities, funders, decision-makers and policy-makers can better understand

what is needed to provide equity-oriented healthcare and (b) an important way of

measuring healthcare because it provides standardized, comparable information

that could be used at Health Centres and other agencies. Participants rated

importance on a 9-point scale where 15 not important and 95 very important.

Participants were also asked to provide comments on redundancy, changes, and

the feasibility to measure the indicators.

Between round one and two, a patient lunch was scheduled on a day at each

Health Center that was considered a typical day. During a face to face group

discussion, patients were invited to provide their feedback on the indicators,

particularly in relation to their face validity and relative importance. Based on

feedback from patients and analysis of their perspectives, which highlighted

theoretically important themes (e.g. the need for PHC services and staff to

acknowledge the pervasiveness of violence and trauma in peoples lives), two

indicators that were scored low by staff participants were kept for round two.

Obtaining feedback from staff and patients on the health care equity indicators

through the modified Delphi process served two functions: 1) content validation

of the work we had done with the Health Centres to develop them and 2)

incorporation of provider and patient views on the importance of these indicators

for monitoring and performance measurement purposes.

We provided participants with definitions of Equity-oriented PHC and

Indicators. Equity-oriented PHC was defined as health care that explicitly aims

to reach out to and close the health equity gap for people who are most affected

by social and structural inequities. We explained to staff and patients that

indicators were defined as ways of measuring the process, effectiveness, and

PLOS ONE | DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0114563 December 5, 2014 6 / 15

Health Equity Indicators in Primary Health Care

impact of health services. Indicators are used by clinics, health authorities,

funders, organizations, and decision-makers as part of the performance

measurement and accountability.

Results

The majority of staff participants were female (71%) and between the ages of 30

59 (76%). Most reported their ethnicity as Caucasian followed by Aboriginal.

Forty percent of the staff participants were either physicians (n513) or registered

nurses or nurse practitioners (n512). Other staff that participated reported their

positions as medical office assistants (n514), outreach workers (n510),

administrative leaders/office managers (n59) or other (n55). Patients who

participated were mainly female (56%) and also between the ages of 3059 years

of age (72%). Most patients reported their ethnicity as Aboriginal followed by

Caucasian.

The evolution of the indicators during the 2 Delphi rounds is displayed in

Table 1. Of the original 42 Indicators, 17 were dropped after round one (Table 2)

and an additional eight were dropped after round two (Table 3). A total of 17

Indicators make up the priority set. Items were eliminated because they were rated

as low importance (,8.0) in both rounds and were either redundant or more than

one participant commented that the ability to take action on the indicator was

highly unlikely.

Table 1 displays the final list of 17 indicators of equity in PHC and the relevant

key dimensions of equity-oriented PHC that they could represent. The majority of

indicators (10/17) represent more than one key dimension of equity-oriented

PHC. While each of the indicators can be used to examine inequity-responsive

care, there are three unique indicators which can be used to examine an

organizations capacity to provide trauma/violence-informed care. This table also

presents the degree of importance for each Indicator.

Four of the 17 indicators are about measuring the practices or organizations

ability to provide an environment where health care equity can be addressed. That

is, in order to achieve health care equity, performance at the practice or

organizational level is as important as assessing the performance of staff. Two of

the highest rated treatment or processes of care indicators reflect the need for

culturally competent and culturally safe care, and trauma and violence-informed

care, particularly given the known negative health effects of trauma, and

interpersonal and structural violence. These indicators point to the importance of

purposefully and intentionally establishing strategies to foster trust with patients

who often experience dismissal and discrimination when seeking care, and in their

everyday lives [5, 22, 23]. Trust between a provider and patient plays a major role

in the equity of treatment and treatment outcomes [7].

Finally, there are four indicators that can be used to measure outcomes which

can be directly attributable to equity responsive PHC. Notably, one outcome

indicator is aimed at measuring staff ability and confidence in provision of care to

PLOS ONE | DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0114563 December 5, 2014 7 / 15

Health Equity Indicators in Primary Health Care

Table 1. Core set of Health Equity Indicators for PHC Organizations After Modified Delphi Consultation.

Round 2 Relevant Key Dimensions

Round 1 Mean Mean of Equity-Oriented PHC Potential Data

Original Indicator (SD) (SD) Final Indicator Services Source

Practice/Clinic Context

1. Funding is allocated to support 8.3 (1.2) 8.2 (1.3) Provide ongoing training Inequity-responsive care, Organizational

ongoing training (including orienta- Modified for all staff to support Contextually-tailored care, Survey

tion) of all staff re: (a) cultural achieving the clinics Culturally-safe care,

competence as it applies to the mandate to promote Trauma/violence-informed

local context (b) inequity-respon- equity care

sive care (e.g. social determinants

of health), (c) trauma-informed care

2. All team members are working to 8.3 (0.9) Same 8.2 (1.2) Ensure staff work to their Inequity-responsive care, Staff Survey,

full scope of practice full scope of practice to Culturally-safe care Organizational

optimize the clinics capa- Survey

city to provide equity-

oriented care or services

3. Vision/mission statement acknowl- 7.8 (1.8) 8.1 (1.3) Include an explicit state- Inequity-responsive care, Organizational

edges that addressing inequity, Modified ment regarding commit- Trauma/violence-informed Survey

trauma, and cultural competence ment to foster health care, Culturally-safe care

are explicit mandates equity in Vision and

Mission Statements

4. Funding is allocated for programs 8.0 (1.1) 8.1 (1.1) Provide strategies to sup- Trauma/violence-informed Organizational Survey,

or strategies to support staff who Modified port staff to deal with the care Staff Survey, Reflexive

work with populations with high emotional impact of work- practice/self-assess-

prevalence of trauma ing with patients who ment, Peer review

experience trauma includ-

ing interpersonal and

structural forms of vio-

lence1

Treatment/Processes of Care/

Outputs

5. Staff demonstrate culturally safe 8.4 (1.0) Same 8.4 (1.1) Provide culturally safe Culturally-safe care Observational Survey,

care (checking assumptions, taking care and practices as evi- Staff Survey, Reflexive

historical context into consideration, denced by, for example, practice/self-assess-

acknowledging and addressing staff questioning their ment, Peer review

context such as language, religion, assumptions about cul-

spirituality) ture, taking sociopolitical

and historical contexts into

consideration, acknowled-

ging and addressing con-

texts such as language,

religion, sexual orienta-

tion, age, geography,

spirituality, etc

6. Patients report experiencing 8.5 (0.7) 8.4 (1.0) Assess patients level of Inequity-responsive care, Patient Survey

increased trust in provider and Modified trust in staff Culturally-safe care,

respectful relations Trauma/violence-informed

care

7. Interprofessional collaboration is a 8.1 (1.0) Same 8.3 (1.2) Engage in interprofes- Inequity-responsive care, Organizational Survey,

routine part of the services and care sional collaboration as a Contextually-tailored care Staff Survey

provided routine aspect of care and

services provided

PLOS ONE | DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0114563 December 5, 2014 8 / 15

Health Equity Indicators in Primary Health Care

Table 1. Cont.

Round 2 Relevant Key Dimensions

Round 1 Mean Mean of Equity-Oriented PHC Potential Data

Original Indicator (SD) (SD) Final Indicator Services Source

8. Services at the clinic support 8.5 (0.9) 8.2 (1.1) Engage and coordinate Inequity-responsive care, Organizational

patients access to various types of Modified with community services, Contextually-tailored care Survey

social assistance services (e.g. and government and non-

income, housing, food assistance, governmental organiza-

residential school programs, dis- tions, in planning and

ability) providing care for patients,

including for example:

Housing services; Social

welfare services; Child

welfare services and sup-

port services for parents;

Counseling services for

trauma or other mental

health issues; Services for

substance use issues;

Elders, traditional healers,

Aboriginal support work-

ers; Acupuncturists or

physiotherapists, if

needed

9. Intersectoral advocacy activities 7.7 (1.1) 8.2 (1.0) Engage and collaborate Inequity-responsive care, Organizational Survey,

occur such as educational colla- Modified with other health depart- Contextually-tailored care Staff Survey, External

borative activities with other health ments, organizations and partner survey (e.g.

agencies/institutes such as hospi- social service agencies ministry stake-

tals regarding how to tailor holders)

services, programs and

approaches to better meet

the needs of marginalized

populations (e.g., with

emergency departments,

pharmacies, hospital

units, walk in clinics, shel-

ters, etc.)

10. Systems are in place to identify and 8.5 (0.9) Same 8.1 (1.2) Create processes to iden- Inequity-responsive care, Organizational

follow up with patients who are at tify and follow-up with Contextually tailored care, Survey

risk of falling through the cracks patients who are at risk of

(e.g., patients who repeatedly miss falling through the

appointments, or who dont follow cracks (e.g., patients who

through referrals, or who dont repeatedly miss appoint-

come in to pick up their meds, etc.) ments or do not follow

through referrals, etc.)

11. Services and programs are avail- 8.3 (1.0) Same 8.1 (1.0) Tailor services and pro- Inequity-responsive care, Organizational

able and tailored to meet the health grams to meet the health Contextually-tailored care, Survey

and healthcare needs of the local and healthcare needs of Culturally-safe care

populations served, for example: local populations served.

outreach and homecare services; (e.g., outreach services;

in-patient visits; meal programs; in-patient visits; assis-

child care; assistance with trans- tance with child care;

portation; gender-specific services assistance with transpor-

such as womens groups; trauma- tation; gender-specific

specific services; assistance with services such as womens

accessing housing, income and or mens groups; trauma-

food specific services; assis-

tance with accessing

housing, income and food)

PLOS ONE | DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0114563 December 5, 2014 9 / 15

Health Equity Indicators in Primary Health Care

Table 1. Cont.

Round 2 Relevant Key Dimensions

Round 1 Mean Mean of Equity-Oriented PHC Potential Data

Original Indicator (SD) (SD) Final Indicator Services Source

12. All staff demonstrate reflexive 8.3 (1.0) 8.1 (1.2) Regularly examine how Inequity-responsive care, Staff Survey, Reflexive

practice Modified staff members verbal and Culturally-safe care, practice/self-assess-

non-verbal interactions Trauma/violence-informed ment, Peer review

impact patients care

13. Regular team meetings involve all 8.3 (1.3) 8.0 (1.2) Develop mechanisms to Inequity-responsive care Organizational

staff to address complex health and Modified integrate input from all Contextually-tailored care, Survey

healthcare issues staff members to address Culturally-safe care,

patients complex health Trauma/violence-informed

and health care issues care

(e.g., team meetings, case

conferences, care teams)

Treatment Outcomes/Immediate

Outcomes of PHC

14. Patients report improved quality of 8.4 (0.9) 8.3 (1.0) Assess levels of improve- Inequity-responsive care Patient Survey, Patient

life Modified ments in patients quality Interviews

of life (as a result of

receiving care at the

clinic)

15. Providers have increased knowl- 8.3 (0.9) 8.2 (1.0) Provide ongoing training Trauma/violence-informed Organizational Survey,

edge and skills in working with the Modified on (a) the health effects of care Staff Survey

health effects of trauma and related trauma, violence and

symptoms related symptoms, and (b)

the development of

knowledge, skills, and

confidence to work with

patients affected by

trauma and violence

16. The clinic is able to track whether 8.0 (1.3) 8.2 (1.1) Assess whether patients Inequity-responsive care, Patient surveys,

the patient-population has fewer Modified report that they health and Culturally-safe care, Patient Interviews

unmet health care needs healthcare needs have Trauma/violence-informed

been met care

17. Patient activation is monitored 8.3 (0.8) 7.6 (1.3) Assess patients levels of Inequity-responsive care, Patient survey, Patient

Modified confidence in managing Contextually-tailored care Interviews

their health and health

care needs (e.g., asking

staff for help, making

appointments, following

through with appoint-

ments, etc.)

Note. Participants rated the importance of each indicator on a 9-point scale where 15 not important and 95 very important. A higher score5more

importance. Indicators were modified or kept the same between Round 1 and Round 2.

1

Trauma- and violence-informed care is a relative new concept in most health sectors, despite evidence confirming the high rates of trauma and violence

experienced by people experiencing the negative health effects of health, social and structural inequities. Trauma- and violence informed care requires all

staff in an organization, including receptionists to direct care providers and management, to understand the intersecting health effects of trauma, structural

and individual violence, and other forms of inequity, so that health care encounters are affirming, and the possibility of re-traumatization is reduced. Trauma-

and violence informed care is not about eliciting trauma histories; rather it is about creating a safe environment based on an understanding of trauma effects.

doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0114563.t001

individuals who may be vulnerable. Surprisingly, the outcome indicator related to

patients improved skills, knowledge, and confidence was not rated highly during

the second round. Given past work in this area [9, 2427] and our analysis of the

PLOS ONE | DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0114563 December 5, 2014 10 / 15

Health Equity Indicators in Primary Health Care

Table 2. Potential Health Equity Indicators that were dropped after Round 1.

1. Organizational commitment to equity is reflected in a flattened hierarchy within the team

2. Funding level is adequate to offer competitive (at industry level) compensation for all staff

3. Hiring of staff reflects (in part) the demographics of the population served (i.e. language, gender, age, ethnicity, geography, etc.)

4. Staff orientation (when hired and ongoing) includes education about social, economic, political context of the health of local population and on impacts

on health and health inequities

5. Staff have ongoing training in the health effects of trauma and related symptoms and are shown how to use this knowledge in the provision of care

6. Staff have ongoing training to provide team based care

7. Strategies are in place to help staff address vicarious trauma and working with traumatized and marginalized populations

8. Referrals for patients to appropriate services are completed when patients need assistance for example, with housing services, social welfare

services, counseling services (e.g. for trauma), medical specialists, elders, traditional healers, acupuncturists, Aboriginal support workers, and other

referrals as necessary

9. Patients pain and trauma histories are regularly updated in chart

10. Patients pain and trauma histories are assessed using appropriate assessment tools

11. Actively listening for patients trauma histories

12. Provision of services that address social determinants of health (e.g., residential school healing, womens wellness)

13. Incorporation of cultural practices by staff (e.g., smudging, elder supports to staff)

14. Percentage of patients who are eligible do successfully access income or housing assistance programs (or other types of social assistance

programs)

15. Each member of the team reports feeling valued and that their input is valued

16. Patients report improved health

17. Patients report increased emotional and physical safety

doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0114563.t002

qualitative and observational data, we retained the item in the set proposed in this

paper, and suggest that more work is needed to clarify the wording.

Discussion

Through a modified Delphi, we constructed 17 indicators that could be used in

examining equity in PHC. The value in this work arises from participation of

patients, providers, and staff of clinics or primary care organizations that target

services to patient-populations who are most vulnerable to inequities. The

indicators cover all four key dimensions of equity-oriented PHC services and

could be used to monitor and measure equity in PHC across organizations.

Notably, these indicators and subsequent development of items can be used to

measure the domains of equitable treatment and treatment outcomes.

Given that this work was meant to complement existing PHC indicators where

of access to care is well considered, we did not construct any indicators on that

domain as a component of equity-oriented PHC. Most work has examined

horizontal equity, or equality. For example, a systematic review of the equity

dimension in evaluations of the UK Quality and Outcomes framework found that

most studies had examined indicators of diabetes and coronary heart disease

stratified by age, sex and/or ethnicity [7] suggesting concern for equality. The 17

indicators presented in this paper draw attention to the extent to which PHC

organizations address vertical equity in the areas of treatment and treatment

PLOS ONE | DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0114563 December 5, 2014 11 / 15

Health Equity Indicators in Primary Health Care

Table 3. Potential Health Equity Indicators that were dropped after Round 2.

Relevant Key Dimensions

Round 1 Round 2 of Equity-Oriented PHC

Original Indicator Mean (SD) Mean (SD) Modifications between Rounds 1 and 2 Services

Funding is allocated to support 7.3 (1.6) Modified 7.2 (1.9) Dropped The clinic should develop mechanisms to Contextually-tailored care,

peer workers or volunteers (who optimize patient participation in the organi- Inequity-responsive care

reflect the populations served) zation (e.g., patient representatives on com-

mittees or boards, patient advisory

mechanism, peer workers, volunteers)

There is a low turnover of staff at 7.7 (1.4) Same 7.7 (1.2) Dropped There should be a low turnover of staff at the Contextually-tailored care,

the clinic. clinic Inequity-responsive care

The organization has maximum 7.9 (1.2) Modified 7.8 (1.4) Dropped The clinic should have flexibility to use its Contextually-tailored care,

flexibility to allocate funds to funds to meet the needs of the populations Inequity-responsive care

meet the needs of the popula- served

tions served

Physical environment (e.g., 7.9 (1.3) Same 7.9 (1.3) Dropped The clinics physical environment (e.g., wait- Contextually-tailored care,

waiting room) is tailored to be ing room) should be tailored to be welcoming Culturally safe care,

welcoming and supportive of the and supportive of the target populations Trauma/violence-informed

target populations care

Visible signs (such as posters, 7.0 (1.9) Modified 7.7 (1.2) Dropped The clinic should have ways of supporting Trauma/violence-informed

or pamphlets) that acknowledge people to address issues of violence in their care

the pervasiveness of violence lives (e.g., acknowledging the existence and

are posted in the clinic, and are impact of violence against women with

adapted to the local populations pamphlets available at the clinic, annual

walks, representation at community events,

safety planning, etc.)

Charting reflects an effort to 7.6 (1.7) Modified 7.7 (1.5) Dropped The language used by staff (e.g., charting, in Inequity-responsive care

minimize risks of stigmatization meetings) is as respectful as possible (e.g.,

and bias (e.g. avoiding labels) stigmatizing labels are avoided, for example,

frequent flyer, etc.)

Patients report reduced duration 7.8 (1.3) Same 7.2 (1.6) Dropped Patients who come to the clinic should report Trauma/violence-informed

and effects of trauma-related reduced levels of trauma-related symptoms care

symptoms (e.g. pain, sleep, over time (e.g., sleep disturbances, anxiety

capacity for emotional safe and panic attacks, chronic pain)

guarding)

Patients report increased cus- 7.7 (1.4) Modified 7.4 (1.7) Dropped Patients who come to the clinic should report Inequity-responsive care

tody and access to children increased custody and access to their

children (for families who are involved with

the child welfare system)

Note. Participants rated the importance of each indicator on a 9-point scale where 15 not important and 95 very important. A higher score5more

importance. Indicators were modified or dropped between Round 1 and Round 2.

doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0114563.t003

outcomes. Our results suggest that indicators of vertical equity in the areas of

treatment and treatment outcomes are critical. Additionally, the practice or

organizational context and processes of care (also known as outputs) are

important for the provision of equity-responsive PHC. Indeed, Boeckxstaens, et al

[7] point out that non-disease specific and processes of care indicators are

important for equitable treatment in PHC. Financially driven quality improve-

ment or performance measurement in PHC using purely biomedical indicators, or

indicators based on adherence to clinical guidelines (whether related to disease-

management or health promotion) may lead to a loss of care quality [28] and

ability to measure equity in health care.

PLOS ONE | DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0114563 December 5, 2014 12 / 15

Health Equity Indicators in Primary Health Care

The health equity indicators proposed in this paper highlight areas that

organizations(e.g., funding allocations to ongoing training in key dimensions of

equity-oriented care provision) and providers (e.g., reflexive practice, increased

knowledge, skill in working with the health effects of trauma) can work towards in

striving for higher performance of equal treatment. Measuring performance for

complex vulnerable patients is itself a test of health system performance.

As noted, whereas equal health care means equal access, treatment, and

treatment outcomes for people in equal need [7]. The proposed health equity

indicators suggest policy makers and researchers move beyond comparative need,

which is akin to horizontal equity [8]. That is, researchers and policy makers

ought to move beyond only comparing access, treatment, and treatment outcomes

by characteristics such as income, gender, or age. Normative need, those which are

defined by an expert (e.g. GP, nurse practitioner, pharmacist), and felt need,

asking people what they feel they need [29, 30] ought to be taken into account in

trying to attain vertical equity.

This work took place with staff and patients from two Urban Aboriginal Health

Centres that focus on delivering PHC services to groups marginalized by poverty,

racism and other structural inequities. Further work is needed to pilot test

whether these indicators can capture the activities of primary care settings or PHC

organizations in fostering greater equity in health care. More feedback on the

indicators is needed from staff and patients who obtain their PHC from other

models of care such as solo or group practices. Next steps need to include items

and scales that will reliable and validly measure indicators of health care equity as

well as methods to collect the necessary information from patients, providers and

other clinical staff, chart audits, and organizational surveys. Some of these

indicators will not currently be measurable using already existing data sources.

Most work on PHC indicators to date has not explicitly used an equity lens,

creating potential gaps in what is counted as worthwhile to measure. In particular,

little attention has been paid to whether current indicators: (1) are sensitive

enough to detect the impacts of services, programs and policies relative to the

health needs of marginalized groups or (2) adequately capture the complexity of

delivering PHC or PH services to diverse groups of marginalized populations. As

work on operationalizing these indicators continues, so will their potential to

serve as a core set of monitoring and performance measures, and the potential for

scaling-up their applicability across diverse contexts and jurisdictions.

Acknowledgments

This research was funded by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research. The

funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to

publish, or preparation of the manuscript. We would like to acknowledge the

patients and staff at the PHC Centres for their generous contributions to this

work. We thank to Dr. Koushambhi Khan for her leadership as our research

manager and research assistant Leena Chau for her careful editorial work.

PLOS ONE | DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0114563 December 5, 2014 13 / 15

Health Equity Indicators in Primary Health Care

Author Contributions

Conceived and designed the experiments: STW AJB CV VS JL. Performed the

experiments: STW AJB CV JL AF VS OG DT. Analyzed the data: STW AJB CV JL

AF VS OG DT. Contributed reagents/materials/analysis tools: STW AJB CV JL AF

VS. Wrote the paper: STW AJB CV JL AF. Contributed critical and substantive

feedback to this manuscript: VS DT OG. Coded data using NVIVO: AF.

Facilitated access to the study site: OG DT.

References

1. World Health Organization (2008) The world health report 2008: Primary health care now more than

ever. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization. Available: http://www.who.int/whr/2008/whr08_

en.pdf.

2. World Health Organization (2008) Commission on Social Determinants of Health - final report. Geneva,

Switzerland: World Health Organization. Available: http://www.who.int/social_determinants/

thecommission/finalreport/en/. Accessed: 2014 Apr 8.

3. Starfield B (2006) State of the art in research on equity in health. J Health Polit Policy Law 31: 1132.

4. Kringos DS, Boerma WGW, Hutchinson A, van der Zee J, Groenewegen PP (2010) The breadth of

primary care: A systematic literature review of its core dimensions. BMC Health Serv Res 10: 65.

doi:10.1186/1472-6963-10-65

5. Browne AJ, Varcoe CM, Wong ST, Smye VL, Lavoie J, et al. (2012) Closing the health equity gap:

evidence-based strategies for primary health care organizations. Int J Equity Health 11: 59. doi:10.1186/

1475-9276-11-59

6. Aggarwal M, Hutchison B (2012) Toward a primary care strategy for Canada. Ottawa, ON: Canadian

Working Group for Primary Healthcare Improvement. Available: http://www.cfhi-fcass.ca/

SearchResultsNews/12-12-11/e73966b0-766d-4f62-98c6-39efa71578dd.aspx.

7. Boeckxstaens P, Smedt D De, Maeseneer J De, Annemans L, Willems S (2011) The equity

dimension in evaluations of the quality and outcomes framework: A systematic review. BMC Health Serv

Res 11: 209. doi:10.1186/1472-6963-11-209

8. Ward PR (2009) The relevance of equity in health care for primary care: Creating and sustaining a fair

go, for a fair innings. Qual Prim Care 17: 4954.

9. Wong ST, Browne AJ, Varcoe C, Lavoie J, Smye V, et al. (2011) Enhancing measurement of primary

health care indicators using an equity lens: An ethnographic study. Int J Equity Heal 10: 38. doi:1475-

9276-10-38 [pii] 10.1186/1475-9276-10-38

10. Clair M (2000) Commission detude sur les services de sante et les services sociaux: Les solutions

emergentes, rapport et recommentaions. Quebec: Gouvernement du Quebec.

11. Stewart AL, Napoles-Springer AM (2003) Advancing health disparities research: can we afford to

ignore measurement issues? Med Care 41: 12071220.

12. Canadian Institute for Health Information (2009) The Health Indicators Project: Report from the Third

Consensus Conference on Health Indicators. Ottawa, ON: Canadian Institute for Health Information

(CIHI). Available: https://secure.cihi.ca/estore/productFamily.

htm?locale5en&pf5PFC1392&lang5FR&mediatype50. Accessed: 2014 Apr 8.

13. Farmer P (2005) Pathologies of Power: Health, Human Rights, and the New War on the Poor. Berkeley,

CA: University of California Press. Available: http://books.google.ca/books/about/Pathologies_of_Power.

html?id52sbP7J-lckoC&pgis51. Accessed: 2014 Apr 8.

14. Wuest J, Ford-Gilboe M, Merritt-Gray M, Varcoe C, Lent B, et al. n.d.) Abuse-related injury and

symptoms of posttraumatic stress disorder as mechanisms of chronic pain in survivors of intimate

partner violence. Pain Med 10: 739747. doi:10.1111/j.1526-4637.2009.00624.x

15. Wathen CN, Jamieson E, Wilson M, Daly M, Worster A, et al. (2007) Risk indicators to identify

intimate partner violence in the emergency department. Open Med 1: e11322.

PLOS ONE | DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0114563 December 5, 2014 14 / 15

Health Equity Indicators in Primary Health Care

16. Browne AJ, Varcoe C, Wong ST, Smye V, Lavoie J, et al. (2012) Closing the Health Equity Gap:

Strategies for Primary Healthcare Organizations. Int J Heal Equity.

17. Denzin NK, Lincoln YS (2011) The Sage handbook of qualitative research. Thousand Oaks, Calif:

Sage.

18. Sandelowski M (2004) Using Qualitative Research. Qual Health Res 14: 13661386. doi:10.1177/

1049732304269672

19. Thorne S (2008) Interpretive description. Walnut Creek, CA: Left Coast Press.

20. QSR International (2012) NVivo: Qualitative software program. Available: http://www.qsrinternational.

com/contact.aspx.

21. Haggerty J, Burge F, Gass D, Levesque J, Pineault R, et al. (2007) Operational definitions of

attributes of primary health care to be evaluated: Consensus among Canadian experts. Ann Fam Med 5:

336344.

22. Varcoe C, Browne AJ, Wong S, Smye VL (2009) Harms and benefits: Collecting ethnicity data in a

clinical context. Soc Sci Med 68: 16591666. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2009.02.034

23. Stuber J, Meyer I, Link B (2008) Stigma, prejudice, discrimination and health. Soc Sci Med 67: 351

357. Available: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/18440687. Accessed: 2014 Apr 5.

24. Hibbard JH (2009) Using systematic measurement to target consumer activation strategies. Med Care

Res Rev 66: 9S27S.

25. Hibbard JH, Stockard J, Mahoney ER, Tusler M (2004) Development of the Patient Activation

Measure (PAM): Conceptualizing and Measuring Activation in Patients and Consumers. Health Serv Res

39: 10051026. doi:10.1111/j.1475-6773.2004.00269.x

26. Wong ST, Peterson S, Black C (2011) Patient Activation in Primary Healthcare: A Comparison between

Healthier Individuals and Those with a Chronic Illness. Med Care 49: 469479. doi:10.1097/

MLR.0b013e31820bf970

27. Wong ST, Yin D, Bhattacharyya O, Wang B, Liu L, et al. (2010) Developing a performance

measurement framework and indicators for community health service facilities in urban China. BMC Fam

Pract 11: 91. doi:10.1186/1471-2296-11-91

28. Gillies JCM, Mercer SW, Lyon A, Scott M, Watt GCM (2009) Distilling the essence of general practice:

A learning journey in progress. Br J Gen Pract 59: e16776. doi:10.3399/bjgp09X420626

29. Bradshaw JA (1994) The conceptualization and measurement of need. In: Popay J, Williams G, editors.

Research the Peoples Health. London, England: Routledge. pp. 4557. Available: http://books.google.

com/books?hl5en&lr5&id5hRuIAgAAQBAJ&pgis51. Accessed: 2014 Apr 8.

30. Bradshaw JA (1972) A taxonomy of social need. In: McLachlan G, editor. Problems and Progress in

Medical Care. Oxford, England: Nuffield Provincial Hospital Trust.

PLOS ONE | DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0114563 December 5, 2014 15 / 15

You might also like

- Physical Medicine & Rehabilitation - Randall BraddomDocument1,482 pagesPhysical Medicine & Rehabilitation - Randall BraddomSimona Chirică90% (10)

- Whitepaper Spotlight On Regulatory Reforms in ChinaDocument15 pagesWhitepaper Spotlight On Regulatory Reforms in ChinaAlex PUNo ratings yet

- HIS 101 Compiled Notes 3Document10 pagesHIS 101 Compiled Notes 3Rey Ann ConcepcionNo ratings yet

- Stories of Special Children, Paknaan, Mandaue, CebuDocument21 pagesStories of Special Children, Paknaan, Mandaue, CebuErlinda Posadas100% (1)

- Benedict Lust LifeDocument8 pagesBenedict Lust Lifestormbrush100% (1)

- Plenary II SimpsonDocument41 pagesPlenary II Simpsonshekhar groverNo ratings yet

- Sister Blessing Project.Document41 pagesSister Blessing Project.ayanfeNo ratings yet

- Health Literacy: Applying Current Concepts To Improve Health Services and Reduce Health InequalitiesDocument10 pagesHealth Literacy: Applying Current Concepts To Improve Health Services and Reduce Health InequalitiesasriadiNo ratings yet

- Health Promotion Overview: Evidence-Based Strategies For Occupational Health Nursing PracticeDocument9 pagesHealth Promotion Overview: Evidence-Based Strategies For Occupational Health Nursing PracticeAdrîîana FdEzNo ratings yet

- Person-Centred Value-Based Health CareDocument58 pagesPerson-Centred Value-Based Health CarercabaNo ratings yet

- The Health Inequalities Assessment Toolkit: Supporting Integration of Equity Into Applied Health ResearchDocument6 pagesThe Health Inequalities Assessment Toolkit: Supporting Integration of Equity Into Applied Health ResearchAna Porroche-EscuderoNo ratings yet

- A Three-Stage Approach To Measuring Health Inequalities and InequitiesDocument13 pagesA Three-Stage Approach To Measuring Health Inequalities and Inequitiessean8phamNo ratings yet

- 2013-Evidence Based Public HealthDocument15 pages2013-Evidence Based Public HealthEric Yesaya TanNo ratings yet

- Public Preferences For Prioritizing Preventive and Curative Health Care Interventions - A Discrete Choice ExperimentDocument10 pagesPublic Preferences For Prioritizing Preventive and Curative Health Care Interventions - A Discrete Choice ExperimentTheDevchoudharyNo ratings yet

- Monitoring The Implementation of The WHO Global Code of Practice On The International Recruitment of Health Personnel: The Case of IndonesiaDocument63 pagesMonitoring The Implementation of The WHO Global Code of Practice On The International Recruitment of Health Personnel: The Case of IndonesiaFerry EfendiNo ratings yet

- Jurnal IPE B1.1Document15 pagesJurnal IPE B1.1fikri syafiqNo ratings yet

- Interprofessional Teamwork and Collaboration Between Community Health Workers and Healthcare Teams: An Integrative ReviewDocument9 pagesInterprofessional Teamwork and Collaboration Between Community Health Workers and Healthcare Teams: An Integrative ReviewNur HolilahNo ratings yet

- SAGE Open Medicine 2: 2050312114522618 © The Author(s) 2014 A Qualitative Study of Conceptual and Operational Definitions For Leaders inDocument21 pagesSAGE Open Medicine 2: 2050312114522618 © The Author(s) 2014 A Qualitative Study of Conceptual and Operational Definitions For Leaders inascarolineeNo ratings yet

- Ramalho 2019 - Plosone - q2Document20 pagesRamalho 2019 - Plosone - q2nanaloboNo ratings yet

- NQF Roadmap For Promoting Health Equity and Eliminating Disparities Sept 2017Document119 pagesNQF Roadmap For Promoting Health Equity and Eliminating Disparities Sept 2017iggybauNo ratings yet

- Evidence-Based Health Policy: A Preliminary Systematic ReviewDocument5 pagesEvidence-Based Health Policy: A Preliminary Systematic ReviewAndre LanzerNo ratings yet

- Distribution of Self-Reported Health in IndiaDocument18 pagesDistribution of Self-Reported Health in Indiasuchika.jnuNo ratings yet

- Health Affairs BMC Europe's Strong Primary Care Systems Are Linked To Better Population HealthDocument10 pagesHealth Affairs BMC Europe's Strong Primary Care Systems Are Linked To Better Population HealthgmantzaNo ratings yet

- Ebt Litreview CheriDocument8 pagesEbt Litreview Cheriapi-308965846No ratings yet

- Utility and Limitations of Measures of Health Inequities A Theoretical PerspectiveDocument9 pagesUtility and Limitations of Measures of Health Inequities A Theoretical PerspectiveStephanyNo ratings yet

- Journal Pone 0152866Document20 pagesJournal Pone 0152866yulya lasmitaNo ratings yet

- Weaver-2020-Perspective - Guidelines Needed For The Conduct of Human Nutrition Randomized Controlled TrialsDocument3 pagesWeaver-2020-Perspective - Guidelines Needed For The Conduct of Human Nutrition Randomized Controlled TrialsKun Aristiati SusiloretniNo ratings yet

- Social Science & Medicine: Mandy Ryan, Philip Kinghorn, Vikki A. Entwistle, Jill J. FrancisDocument10 pagesSocial Science & Medicine: Mandy Ryan, Philip Kinghorn, Vikki A. Entwistle, Jill J. FrancisAnis KhairunnisaNo ratings yet

- Health Facilities Roles in Measuring Progress of Universal Health CoverageDocument10 pagesHealth Facilities Roles in Measuring Progress of Universal Health CoverageIJPHSNo ratings yet

- Do Efforts To Standardize, Assess and ImproveDocument8 pagesDo Efforts To Standardize, Assess and ImproveWiwit VitaniaNo ratings yet

- Public Health Dissertation TitlesDocument7 pagesPublic Health Dissertation TitlesWriteMyPaperPleaseSingapore100% (1)

- A Framework To Measure The Impact of Investments in Health ResearchDocument16 pagesA Framework To Measure The Impact of Investments in Health ResearchGesler Pilvan SainNo ratings yet

- Awareness Of, Attitude Toward, and Willingness To Participate in Pay For Performance Programs Among Family Physicians A Cross-Sectional StudyDocument9 pagesAwareness Of, Attitude Toward, and Willingness To Participate in Pay For Performance Programs Among Family Physicians A Cross-Sectional StudySanny ChristianNo ratings yet

- Gha 9 29329Document19 pagesGha 9 29329Bahtiar AfandiNo ratings yet

- Jurnal PublikasiDocument29 pagesJurnal PublikasiLisana AzkiaNo ratings yet

- Evidence-Based Practice and The Quadruple AimDocument5 pagesEvidence-Based Practice and The Quadruple Aimmusule veronNo ratings yet

- Perceptions of Factors Associated With Inclusive Work and Learning Environments in Health Care Organizations A Qualitative Narrative AnalysisDocument14 pagesPerceptions of Factors Associated With Inclusive Work and Learning Environments in Health Care Organizations A Qualitative Narrative AnalysisAndrea Guerrero ZapataNo ratings yet

- Primary Health Care Literature ReviewDocument4 pagesPrimary Health Care Literature Reviewafdtbluwq100% (1)

- AJPH CHW Published Jul2013Document9 pagesAJPH CHW Published Jul2013anarobertoNo ratings yet

- Role of Institutions in Public Health EducationDocument5 pagesRole of Institutions in Public Health EducationDeepakNo ratings yet