Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Niemeyer Simon - A Defence of Deliberative Democracy

Niemeyer Simon - A Defence of Deliberative Democracy

Uploaded by

Rubén Ignacio Corona CadenaCopyright:

Available Formats

You might also like

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5823)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1093)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (852)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (590)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (898)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (540)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (349)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (823)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (122)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (403)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- 01 - The Legitimacy of Humanitarian Actions and Their Media Representation - The Case of France (Boltanski)Document14 pages01 - The Legitimacy of Humanitarian Actions and Their Media Representation - The Case of France (Boltanski)Rubén Ignacio Corona Cadena100% (1)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- USHRN/APSA Organizing ManualDocument32 pagesUSHRN/APSA Organizing Manualcastenell100% (1)

- Sayer and Corrigan On Marx and State 22012014Document19 pagesSayer and Corrigan On Marx and State 22012014davidsaloNo ratings yet

- Declercq Dieter - The Moral Significance of Humour PDFDocument28 pagesDeclercq Dieter - The Moral Significance of Humour PDFRubén Ignacio Corona CadenaNo ratings yet

- Freedom and Extended SelfDocument30 pagesFreedom and Extended SelfRubén Ignacio Corona CadenaNo ratings yet

- 01 - Liberalism and Multiculturalism (Barry)Document12 pages01 - Liberalism and Multiculturalism (Barry)Rubén Ignacio Corona CadenaNo ratings yet

- 04 - Mysticism - The Transformation of A Love Consumed Into Desire To A Love Without Desire (Moyaert)Document10 pages04 - Mysticism - The Transformation of A Love Consumed Into Desire To A Love Without Desire (Moyaert)Rubén Ignacio Corona CadenaNo ratings yet

- 03 - The Emotional Boundaries of Our Solidarity (Pattyn)Document8 pages03 - The Emotional Boundaries of Our Solidarity (Pattyn)Rubén Ignacio Corona CadenaNo ratings yet

- 04 - The Ethical Meaning of Money in The Thought of Emmanuel Levinas (Burggraeve)Document6 pages04 - The Ethical Meaning of Money in The Thought of Emmanuel Levinas (Burggraeve)Rubén Ignacio Corona CadenaNo ratings yet

- 03 - Christian Ethics and Applied Ethics (Van Gerwen)Document5 pages03 - Christian Ethics and Applied Ethics (Van Gerwen)Rubén Ignacio Corona CadenaNo ratings yet

- Explain How The Political Context in Which Newspapers Are ProducedDocument2 pagesExplain How The Political Context in Which Newspapers Are Producedapi-379275806No ratings yet

- Muhammad Ali JinnahDocument17 pagesMuhammad Ali Jinnahrazarafiq033No ratings yet

- Lomasky Teson Proofs PDFDocument288 pagesLomasky Teson Proofs PDFFrancisco EstevaNo ratings yet

- The Subjection of Women Mill (Handout)Document1 pageThe Subjection of Women Mill (Handout)Jamiah HulipasNo ratings yet

- Carpenter - Participation and MediaDocument5 pagesCarpenter - Participation and MediapofiuloNo ratings yet

- One Party DemocracyDocument6 pagesOne Party DemocracyYuvraj SainiNo ratings yet

- Gr7 Social Studies StandardsDocument10 pagesGr7 Social Studies StandardsShadow 5No ratings yet

- Article370 Essay EnglishDocument4 pagesArticle370 Essay EnglishPrashanth VaidyarajNo ratings yet

- R Guha ArchivesDocument581 pagesR Guha ArchivesAnkit LahotiNo ratings yet

- DECEMBER 1 - Romania's National Day: Union Day or Ziua Marii Uniri (In Romanian), 1 December Commemorates A MemorableDocument1 pageDECEMBER 1 - Romania's National Day: Union Day or Ziua Marii Uniri (In Romanian), 1 December Commemorates A MemorableOana Maria DorosNo ratings yet

- The Role of The United NationDocument4 pagesThe Role of The United Nationnylashahid100% (1)

- CBS News 2016 Battleground Tracker: Arizona, August 2016Document45 pagesCBS News 2016 Battleground Tracker: Arizona, August 2016CBS News PoliticsNo ratings yet

- What Is LiberalismDocument16 pagesWhat Is LiberalismGANESH MANJHINo ratings yet

- Viktor Orbán's Machiavellian Genius - UnHerdDocument8 pagesViktor Orbán's Machiavellian Genius - UnHerdSrinivas RaghavanNo ratings yet

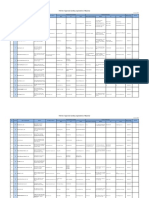

- Full List of Approved Sending Organization of MyanmarDocument22 pagesFull List of Approved Sending Organization of MyanmarZawhtet HtetNo ratings yet

- Reflection 3Document3 pagesReflection 3api-296529803No ratings yet

- Brady Gillerlain There Is No Alternative Russian ElectionsDocument27 pagesBrady Gillerlain There Is No Alternative Russian ElectionsBrady GillerlainNo ratings yet

- Diego Rivera and The Left - The Destruction and Recreation of The Rockefeller Center MuralDocument19 pagesDiego Rivera and The Left - The Destruction and Recreation of The Rockefeller Center Muralla nina100% (1)

- Candidate Statements For Members at Large Toronto 2019Document6 pagesCandidate Statements For Members at Large Toronto 2019Julia BuchananNo ratings yet

- Marxism and Native Americans - Ward ChurchillDocument236 pagesMarxism and Native Americans - Ward Churchilleggalbraith100% (1)

- Robert NozickDocument8 pagesRobert NozickRoberto Barrientos0% (2)

- PICO Action Fund 2018 Civic Engagement Plan - Congressional TargetsDocument17 pagesPICO Action Fund 2018 Civic Engagement Plan - Congressional TargetsJoe SchoffstallNo ratings yet

- Coalition GovernmentDocument19 pagesCoalition Governmentabhi4manyuNo ratings yet

- Max WeberDocument2 pagesMax WeberjenjevNo ratings yet

- Fundamental Rights in India - WikipediaDocument78 pagesFundamental Rights in India - WikipediaJasneet KaurNo ratings yet

- Oral Presentations of Former Colonies-1Document3 pagesOral Presentations of Former Colonies-1Fatima Waqar ZiaNo ratings yet

- CBS News 2016 Battleground Tracker: Pennsylvania, April 24, 2016Document73 pagesCBS News 2016 Battleground Tracker: Pennsylvania, April 24, 2016CBS News PoliticsNo ratings yet

- Kurt Riezler (About)Document6 pagesKurt Riezler (About)Alexandru V. CuccuNo ratings yet

Niemeyer Simon - A Defence of Deliberative Democracy

Niemeyer Simon - A Defence of Deliberative Democracy

Uploaded by

Rubén Ignacio Corona CadenaCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Niemeyer Simon - A Defence of Deliberative Democracy

Niemeyer Simon - A Defence of Deliberative Democracy

Uploaded by

Rubén Ignacio Corona CadenaCopyright:

Available Formats

A Defence of (Deliberative) Democracy in

the Anthropocene

Simon Niemeyer

Australian National University

ABSTRACT. Environmentally focussed scepticism of democracy is often founded

on distrust in the public to choose outcomes consistent with green imperatives.

The spectre of the Anthropocene, with large scale and complex environmental

impacts, increases the stakes. It not only renders the task of governance more

difficult in a technical sense, relating to the ability to deliver outcomes; it also

renders more problematic the task of mobilising citizen support for appropriate

action that serves their best long-term interests. The call to suspend certain

democratic processes to deal with the environmental crisis is intuitively appeal-

ing, but doomed to failure. While eco-authoritarianism is a blunt instrument

that assumes too much on the part of eco-elites, liberal paternalism is sophis-

ticated and empirically robust, yet assumes too little on the part of citizens as

well as being parasitic on the same kind of manipulatory political processes that

have contributed to poor environmental outcomes in the first place. If the

response to the Anthropocene is to reflect the nature of the challenge, then I

argue that governance should involve the active support of citizens who are

attuned to both the urgency and complexity of the task. Such an environmen-

tal citizen is possible when we take into account the democratic context in

which judgements are made and deliberative capacities formed. But this can

only be achieved if democracies develop as a whole in a more deliberative

direction. In the short term, where environmental concern is easily crowded-

out in political debate, deliberation helps to make salient less tangible and

complex dimensions associated with the issue. Over the longer term, the effect

is to transform the polity as a whole, improving deliberative capacity. The pos-

sibilities for achieving these benefits of deliberation in practice, such as enhanc-

ing existing deliberative systems, are considered.

KEYWORDS. Deliberative democracy, environmental governance, democratic

systems

ETHICAL PERSPECTIVES 21, no. 1(2014): 15-45.

2014 by Centre for Ethics, KU Leuven. All rights reserved. doi: 10.2143/EP.21.1.3017285

97154.indb 15 27/03/14 09:16

ETHICAL PERSPECTIVES MARCH 2014

I. INTRODUCTION

T he activities of humans have now reached a scale relative to the size

of earths available resources that the term Anthropocene has been

coined to describe the transition into a new geological epoch in which

human activities have global consequences (Crutzen and Stoermer 2000).

The phenomenon is usually associated with climate change, although it

covers all human activities that impact on features of natural systems,

some of which such as biodiversity are also reaching a critical juncture

(Zalasiewicz et al. 2008). In geological terms, it implies that the human era

is one that will leave a distinctive lithographic trace. Whether or not we

are technically entering such an era is open to debate, particularly from a

geological perspective (e.g. Crutzen 2002). However, while recognising

this debate, the term Anthropocene is a very useful device for communi-

cating both the scale of human activities and their implications for the

earth systems that make them possible. The term is not supposed to

invoke a sense of triumphalism, celebrating the arrival of humans as mas-

ters of their own global commons. Quite the opposite: it is intended to

highlight the scale of the challenges that humans now face (e.g. Crutzen

2002). And those who invoke the term tend to emphasise just how poorly

prepared we are to deal with the consequences.

These challenges overturn the idea that human and environmental

systems can be thought about independently. In the case of climate

change, the challenge involves not only attempting to mitigate the rate of

change, it also involves responding and adapting to its impacts. Whatever

the solution either via technology or reorganising social relationships in

order to live within real or implied limits it will always require deep

political commitment to support definitive action (Karlsson 2013). That

is certainly the case when it comes to democracies, which are supposed

to govern via the consent of citizens, at least in theory. And here is the

catch. Global environmental challenges such as climate change have

emerged during an era in which liberal democratic values are supposed

16

Ethical Perspectives 21 (2014) 1

97154.indb 16 27/03/14 09:16

SIMON NIEMEYER A DEFENCE OF ( DELIBERATIVE ) DEMOCRACY

to have triumphed over the alternatives famously and controversially

expressed as the end of history (Fukuyama 1992). The failure to antic-

ipate and address the anthropocenic challenge is, then, viewed as a failure

of democracy.

But is democracy the cause? And are democracies really incapable of

adequately anticipating and responding to the challenge? Although it is

true enough that complex modern democracies have produced a weaker

response to environmental pressures than might be expected, the causes

are complex (Burnell 2012) and the solution does not necessarily lie in

simply abandoning or constraining democratic principles. Specific democ-

racies may have failed to realise and address global environmental chal-

lenges such as climate change, but it may reflect particular features of

democratic systems that are not thoroughly democratic rather than the

idea of democracy per se.

Moreover, if democracy is the problem, it is also the solution; or is

the least-worst form of solution from among a range of alternatives, each

involving their own significant weaknesses. In particular, I advocate delib-

erative democracy as a vehicle for taking seriously the way in which citi-

zens form their views and determine collective outcomes. At the heart of

the argument is a more optimistic model of the (environmental) citizen,

at least in deliberative contexts.

When considering the challenge of environmental governance, the

common refrain within eco-political theory has tended to involve a call

for some kind of change in political values which has historically

meant a call for a different kind of environmental ethic, often emphasis-

ing eco-centrism (Hayward 1997). Here I argue that appropriate environ-

mental values already exist, at least to some degree in a latent form that

is crowded-out in contemporary polity. Democracy can meet the chal-

lenge posed by the Anthropocene under the right circumstances. The

solution to the problem is not to give in to an authoritarian impulse and

bypass public debate altogether, but to democratise public discourse along

deliberative democratic lines. There are certainly challenges in doing so,

17

Ethical Perspectives 21 (2014) 1

97154.indb 17 27/03/14 09:16

ETHICAL PERSPECTIVES MARCH 2014

but possibilities emerge when we understand the nature of the delibera-

tive citizen and how their positions are formed via authentic deliberation.

The present contribution begins by outlining the nature of the chal-

lenge of governing in the face of the Anthropocene, which involves large-

scale, complex and cross-boundary environmental issues such as climate

change. It then assesses two different types of response (eco-authoritari-

anism, liberal paternalism) that are discussed in the literature that involves

constraining more idealised forms of democracy. The article then moves

on to advocate a move in the opposite direction in favour of deepening

the democratic process along deliberative lines. After considering the

theoretical arguments for deliberation and empirical evidence I then con-

sider the possibilities for achieving deliberative democracy in the real

world of the Anthropocene.

II. THE CHALLENGE OF GOVERNING IN THE ANTHROPOCENE

Contemporary anthropogenic impacts on the biosphere such as climate

change threaten the environmental functions that underpin many human

activities. And according to scientific consensus they are set to proceed

at an increasingly dramatic rate. These events pose serious challenges to

any system of governance for the climate challenged society (Dryzek et al.

2013). According to some, the most pressing and immediate issue involves

basic problem recognition (Biermann 2007, 328), but even here there

appears to be a level of systemic failure. In some constituencies, support

for taking action on climate change, among other environmental issues,

is softening even as the problem is increasing in urgency (Hansen 2010;

Coorey 2010; GlobeScan Radar 2013).

Here we run into the classic tension in green political theory: environ-

mentalists support substantive outcomes, but democrats support legit-

imate political procedures that cannot guarantee those outcomes (Goodin

1992). If citizens decide that issues such as climate change are not impor-

tant, then there is no democratic case for action, even if there is a strong

18

Ethical Perspectives 21 (2014) 1

97154.indb 18 27/03/14 09:16

SIMON NIEMEYER A DEFENCE OF ( DELIBERATIVE ) DEMOCRACY

moral argument.1 The public might reject action for a number of rea-

sons, including optimism that it will be possible to deal with the conse-

quences in the future. Recently this kind of problem has been described

as a kind of confidence trap: democracies are very good at dealing with

crises, but almost incapable of avoiding them (Runciman 2013). The

kind of optimism this breeds contributes to trapping democracy on the

path of disaster.

The spectre of the Anthropocene increases the challenge of gover-

nance considerably, impacting not only on future generations, but also

across national boundaries. Recognising the real nature of this challenge

is enormous, particularly where the scale and complexity of human

induced perturbations to global environmental systems exceed not only

the knowledge and comprehension of any given individual, but also the

boundaries of knowledge systems as well as the capabilities of individual

nation states. And even if the problem is recognised and there is a deter-

mination for action, there is a question of what course of action should

be taken, which will also require support. The need for large scale mobil-

isation is irrespective of whether one places faith in the prospect of

technological solutions or not, which will, in turn, require the invest-

ments in future outcomes that democracies have thus far failed to achieve

(Karlsson 2013).

Failure to mobilise to address anthropocenic challenges such as cli-

mate change may also undermine the prospect of public mobilisation.

It is possible that intensifying climate change might cause citizens to lose

faith and withdraw even further from collective action aimed at address-

ing the consequences (Niemeyer et al. 2005; Hobson and Niemeyer 2011).

In the face of these challenges, some scholars look for solutions that

circumvent perceived democratic weaknesses. The cause for pessimism

often revolves around the longstanding scepticism about the capacities of

citizens to choose the right course of collective action (e.g. Somin 1998;

Schumpeter 1943 [1976]). The question here, from a democratic point of

view, concerns whether there are any circumstances under which ordinary

19

Ethical Perspectives 21 (2014) 1

97154.indb 19 27/03/14 09:16

ETHICAL PERSPECTIVES MARCH 2014

citizens might recognise the moral imperative to address the challenges

inherent in the Anthropocene and articulate support for the kind of col-

lective action that is required. It invokes the age-old question about

whether citizens have the right stuff when it comes to identifying and

realising their (and, in this case, future generations) interests as part of

the democratic process (Tetlock 1998). Those who are not optimistic

about this prospect tend to seek alternative approaches to the democratic

ideal.

Constraining Democracy: The Eco-authoritarian Impulse

There have been a number of prescriptions to the challenge of governing

in the Anthropocene, many of which involve modifying political institu-

tions in ways that bypass the tension between substantive outcome and

democratic process (Goodin 1992). In many ways, this re-emergence of

eco-authoritarianism resonates with the Neo-Malthusian debates that

began in the 1970s (e.g. Ophuls 1973) as growing environmentalism raised

the question about how we could best govern the environmental com-

mons. The contemporary debate differs in that it now models itself on

the example of China, rather than the central state planning of the Soviet

Union; and there is a much greater level of sympathy with the ideal of

democracy (Shahar forthcoming).

Those who would constrain the democratic process are not necessarily

advocating wholesale authoritarianism. But they do advocate intervention-

ist instruments to improve environmental outcomes that are undermined

by the operation of individual democratic rights (Shahar forthcoming).

Giddens (2009), for example, suggests suspending certain types of demo-

cratic process and firewalling decision making specific to climate change.

Others, such as Shearman and Smith (2007), would go further than merely

constraining certain democratic functions and place decision-making in

respect to climate entirely at the hands of enlightened scientists, or eco-

elites.2 Beeson (2010) takes a more prognostic than prescriptive view,

20

Ethical Perspectives 21 (2014) 1

97154.indb 20 27/03/14 09:16

SIMON NIEMEYER A DEFENCE OF ( DELIBERATIVE ) DEMOCRACY

asserting that the impacts of climate change are likely to contribute to a

movement away from democracy and toward authoritarianism, which is

better placed to achieve environmental outcomes. He cites examples within

Southeast Asia, and China in particular, which are associated with authori-

tarian forms of governance that permit more decisive action and in Chinas

case has been successful in achieving developmental goals.

However appealing, authoritarianism provides a poor foundation for

motivating and coordinating collective action in order to meet ecological

imperatives (Shahar forthcoming). Authoritarian approaches cannot deal

with the complexity of feedbacks that are associated with the Anthro-

pocene (Dryzek 1987).3 But even leaving these technical problems aside,

the most significant problem with eco-authoritarianism is similar to that

of eco-authoritarians distrust of citizens: there is simply no guarantee that

elites will continue to act in the interests of good environmental out-

comes in the long term. The record of authoritarianism is not strong, and

where there have been recent examples identified as environmental suc-

cess, such as Chinas move to curtail greenhouse emissions growth, the

underlying reasons tend to be in the economic interests of the state,

which happen to fortuitously align with the environment (Shahar forth-

coming).

Shearman and Smith (2007) are aware of these problems, but remain

optimistic that an eco-elite can be trained to pursue environmental objec-

tives. In the long run, however, political elites are actually unlikely to

support environmental causes on their own terms, not least because the

logic of the state is skewed toward the functions of accumulation, even

before we take into account the effect of lobbying by well-resourced

interests. There is simply no assurance that elites in an eco-authoritarian

state would continue to act in ways that would meet the challenges posed

by the Anthropocene (Gilley 2012).

Moreover, authoritarianism does not appear to work on its own

terms. The argument that Asia is inclined toward authoritarianism is more

nuanced upon closer inspection. China, for example, might be arguably

21

Ethical Perspectives 21 (2014) 1

97154.indb 21 27/03/14 09:16

ETHICAL PERSPECTIVES MARCH 2014

authoritarian at the national level (Gilley 2012), but when we move to

regional and local governance the picture is indeed more nuanced. Local

elections are increasingly occurring at village level, along with experimen-

tation with deliberative methods such as deliberative polls (Leib and He

2006; He and Warren 2011). He and Warren (2011) argue that even at

the national level there is an increasing recognition of the limits of author-

itarianism in governing complex social systems. The result is a transition

toward authoritarian deliberation, which potentially marks a turning

point toward greater democracy albeit in a different form that would

be recognised by liberal democrats.

These examples of a democratic fabric on an authoritarian super-

structure illustrate what Shahar (forthcoming) argues is the chimeric

nature of eco-authoritarianism. The administrative effectiveness of the

state requires that it must, on some level, be responsive to its citizens.

Citizens might not be enfranchised to vote, but the forces of legitimacy

are still present, albeit in a different form. The idea that in practice the

state can dictate environmental outcomes beyond the express will of its

citizens is both theoretically and historically problematic.

Liberal Paternalism and Nudge Theory

One possibility for explicitly maintaining a democratic superstructure

while improving the prospect for environmental outcomes is to find ways

to encourage citizens to behave more ecologically. Liberal paternalism in

the form of nudge theory (John et al. 2009; Hansen and Jespersen 2013)

is a different kind of top-down mechanism for producing collective out-

comes that dovetails more neatly with liberal democratic ideals. Inspired

by insights from behavioural economics, nudging involves setting up con-

ditions that lead to behavioural changes by citizens in ways that are pre-

sumed to produce outcomes that the citizens themselves would want, but

for muddled thinking in everyday contexts (John et al. 2009; Hansen and

Jespersen 2013).

22

Ethical Perspectives 21 (2014) 1

97154.indb 22 27/03/14 09:16

SIMON NIEMEYER A DEFENCE OF ( DELIBERATIVE ) DEMOCRACY

In short, nudge works by altering the choice architecture to encour-

age citizens to behave in ways that improve collective outcomes or

individual decisions (Thaler and Sunstein 2008). Coming as it does from

the field of behavioural economics, the idea of nudge is consistent with

the assumption from economics that individual preferences are fixed,

or at least the mechanisms whereby individuals arrive at their decisions

(John et al. 2009). What is then needed is a corrective mechanism to make

the right decisions.

In practice there are many different forms of nudge, and it can

sometimes be hard to pin down the precise boundaries of the approach.

Some nudges directly steer individuals toward certain specific kinds of

behaviour, such as changing an opt in scheme to an opt out to increase

participation the use of green energy, for example. Others encourage

them to think about a common issue in different ways, such as associat-

ing nature conservation with more charismatic forms of wildlife such

as pandas (Akerlof and Kennedy 2013).

Some forms of nudge are more consistent with democratic ideals

and citizen autonomy than others (John et al. 2009, 366). However, the

idea is still deeply problematic to the extent that it is divorced from

deeper forms of democratic principle. To begin with, the use of nudge

theory begs the question regarding who makes the decision with respect

to who is nudged, when and how. Nudge may indeed work when it comes

to improving environmental behaviour, but it still requires an arbiter for

what constitutes the right decision. According to John et al. (2009), in

the case of nudge it is the state that is the expert and teacher on the

part of citizens. This then returns us to the problem associated with the

eco-authoritarian impulse because the approach would presumably only

be effective to the extent that there is some form of eco-elite devising

nudges to push citizens in the right direction.

Moreover, such a prescription does not take into account the fact that

citizens are already constantly nudged. Although the science behind nudge

has emerged relatively recently, the practice of nudging the population

23

Ethical Perspectives 21 (2014) 1

97154.indb 23 27/03/14 09:16

ETHICAL PERSPECTIVES MARCH 2014

using various mechanisms is very old. This is achieved via a number of

mechanisms, not least by the use of emotive and symbolic arguments to

induce an emotional response and manipulate political choices (Blatter

2009; Niemeyer 2004). Strategies consistent with nudge have been used

for some time to influence public policy, usually to the benefit of a com-

mercial entity. For example, the strategies used by merchants of doubt

to discredit the science demonstrating the health effects of smoking have

been adopted in the case of climate change to good effect (Oreskes and

Conway 2010).

Advocates of nudge theory appear to presume that those who believe

themselves to be arbiters of what the public really wants can out-nudge

those who are not driven by such civic-mindedness. This, it seems, is a

very heroic assumption, particularly given the resources that can be

mobilised by particular interests who are negatively impacted by any move

to address an issue like climate change.

III. DEMOCRACY AND THE ANTHROPOCENE

Despite the concerns of eco-authoritarians, in theory, a democracy is sup-

posed to produce better environmental outcomes than its alternatives it

also tentatively appears to be the case in practice (Ward 2008). Burnell

(2012) argues that democracy has the advantage of being capable of being

inclusive of a wide range of values in the decision making process that

also lend themselves to improving environmental values. In addition,

democracies are supposed to be more responsive, with built-in account-

ability and sensitivity to legitimacy, ensuring that the system responds to

environmental concern. But in practice, democratic systems often fail to

adequately realize and translate demand for action on climate change into

working policy.

According to the critics of democracy the problem is that, in practice,

citizens as political agents fail to adequately synthesise information and

translate this into demand for accountability on complex issues such as

24

Ethical Perspectives 21 (2014) 1

97154.indb 24 27/03/14 09:16

SIMON NIEMEYER A DEFENCE OF ( DELIBERATIVE ) DEMOCRACY

climate change. The problem is not necessarily linked to lack of knowl-

edge, as is often assumed (Ungar 2000). It can owe its origins to a num-

ber of reasons, including that of motivation. Citizens simply fail to care

enough about the issue, taking the cognitively least demanding path in

decision-making (Winkielman and Berridge 2003). Or they can believe

what they want to, engaging in motivated reasoning to justify their initially

preferred outcome (Redlawsk 2002).

The classic remedy to the problem of environmental inaction has

been to prescribe improved environmental values along eco-centric lines

explicitly recognising the intrinsic value of nature or recognising the

importance of the environment for human needs (for a criticism see,

for example, Weale 1993). However, as Hobson (2013) points out, the

path to the environmental citizen is not so clear-cut. The values of eco-

centrism and anthropocentrism turn out to be at least partly contextual

and differentially expressed, in part with different kinds of environmental

issue.

The real problem, however, might not lie in the domain of values per

se. There is evidence that the public is not inherently anti-environment.

The situation is more aptly characterised as ambivalence than opposition.

The phenomenon is well captured by the idea of an environmental value-

action gap, where environmental concern does not translate directly into

behaviour change (e.g. Blake 1999; Gill et al. 1986). The main problem

is that environmental issues are relatively easily crowded-out in view of

non-salience and issue complexity. And climate change in particular

exhibits these features, rendering it easy to obfuscate and confuse the

issue. While some deep climate sceptics absolutely refuse to countenance

human induced climate change, many hold positions that open up spaces

for causing doubt rather than intractable opposition to action to address

the issue that may not reflect what they actually want when there is an

opportunity to thoroughly consider it (Hobson and Niemeyer 2013).

Thus, in not adequately addressing climate change, democracies may

be acting responsively to their constituents expressed preferences, but

25

Ethical Perspectives 21 (2014) 1

97154.indb 25 27/03/14 09:16

ETHICAL PERSPECTIVES MARCH 2014

not necessarily their underlying will (Manin 1987). Or at least they are

responding in a very particular kind of way, since the prevailing democratic

process cultivates preferences that support short-term outcomes, or at

least fails to induce reflection on longer-term consequences. Giddens

(2009) recognises this phenomenon when he speaks of a paradox where

straightforward concern for the abstract idea of climate change translates

into inaction in the face of intangible, distant and invisible impacts. The

result is that when concrete actions to address climate change are pro-

posed as opposed to vague commitments the intangibility of climate

change competes directly with tangible impacts, such as the direct cost of

increased taxation.

Nudge theory also implicitly recognises the environmental ambiva-

lence of citizens, but only insofar as they remain ambivalent. It is not

possible to nudge individuals in directions that they clearly do not wish

to go. It is merely a way of realising outcomes that individuals would

wish for when they engage with their theoretically better selves which

is determined by elites. The historical lessons contained in the confi-

dence trap (Runciman 2013) suggest that once issues are fully recognised

(i.e. when there is a crisis that cannot be denied), democracies are very

good at resolving them. The problem with the Anthropocene is that a

crisis might come too late for action, or at least herald extraordinary

costs due to feedbacks built into the socio-environmental system.4 What

is needed are mechanisms for harnessing the capacity to deal with crisis

before it occurs a deeper form of problem recognition, particularly

among citizens.

IV. DELIBERATIVE DEMOCRACY IN THEORY AND PRACTICE

Here I argue that the possibility for enhancing awareness of anthropocenic

challenges in a democratic context to the extent that it is demonstrably

undeniable is best served by seeking democratic reform consistent with

deliberative democracy. Emerging around 1990, deliberative democracy

26

Ethical Perspectives 21 (2014) 1

97154.indb 26 27/03/14 09:16

SIMON NIEMEYER A DEFENCE OF ( DELIBERATIVE ) DEMOCRACY

is unified by a central belief that democracy ought to involve more than

voting and decision making by elected representatives.

While there is considerable variation among deliberative scholars on

the specifics, deliberative capacity of a democratic polity can be captured

by the conditions deliberativeness, inclusiveness and consequentiality

(Dryzek 2009). A polity is deliberative insofar as the political debate involves

the exchange of reasons under conditions of fairness and equality among

citizens who are open to competing arguments and, where necessary,

accommodating alternative views. In this sense, deliberative democracy

takes seriously the idea that preferences are formed as part of the political

process (e.g. Gutmann and Thompson 1996; Dryzek 1990) in contrast

to nudge theory, which borrows from economic assumptions that prefer-

ences reflect fixed inner states (John et al. 2009). A polity is inclusive to the

extent that all those individuals who are affected by a decision have the

opportunity to deliberate and provide input into the decision making

process. And it is consequential to the extent that the deliberations of citi-

zens are reflected in the decision being made.

It is notable that the features of democracies that are supposed to be

beneficial to the environment (inclusiveness and responsiveness) cited ear-

lier (Burnell 2012) correspond closely to the features of a deliberative sys-

tem (inclusivity and consequentiality; Dryzek 2009). To these dimensions,

deliberative democracy adds deliberativeness to a democratic system.

For the argument here it is the deliberative dimension that holds the

key to realising the full potential to respond the environmental challenges.

This is because deliberation makes salient the environment, represented

by arguments or discourses (Goodin 1996; Dryzek 1995; Dryzek and

Niemeyer 2008). It also has the potential to attune citizens to environ-

mental complexities (Niemeyer 2004; Baber and Bartlett 2005; Smith

2003). Ideally, deliberation produces reflection by citizens approaching

the kind that Shearman and Smith (2007) prize in advocating rule by eco-

elites and avoids Giddens (2009) paradox, such that citizens come to

reflect on the issue with a view to the long-term.

27

Ethical Perspectives 21 (2014) 1

97154.indb 27 27/03/14 09:16

ETHICAL PERSPECTIVES MARCH 2014

This effect of deliberation is different to the idea of nudge theory,

which involves the use of social marketing and behavioural economics to

nudge behaviour without inducing reflection (Rowson 2011). Delibera-

tion, on the other hand, involves a far more conscious process, which

results in deeper and more enduring solutions (Smith 2001; Fung 2003;

Chambers 2003). It is thus not only more democratic, it is also much

more effective than the alternatives, at least to the extent that ideal delib-

erative outcomes are possible.

The evidence to date on the possibilities for deliberation is cause for

qualified optimism, mainly drawn from examples of group deliberation in

the form of mini-publics, which have also been extensively conducted

on environmental issues (see, for example, Gunderson 1995; Ojala and

Lidskog 2011; Pretty 1995; Niemeyer 2004). Mini-publics are the most

practical expression of deliberative democracy (e.g. Goodin and Niemeyer

2003; Niemeyer 2004, 2011a; Setl et al. 2010), which typically involve

the random selection of citizens to participate in a forum that is (ideally)

held over multiple days where discussion is facilitated to achieve the ideals

of deliberation and information is provided, usually in the form of expert

presentation.

Results thus far suggest that citizen preferences become more sensi-

tive to the environment when they engage in deliberation, and in the case

of climate change, demand stronger global action (Besdted and Klver

2009). However, even if we accept whether preference change should be

the gold standard for measuring deliberative success which is question-

able (Niemeyer 2011a; Niemeyer and Dryzek 2007) environmental con-

cern alone is not sufficient to deal with the complexities and uncertainties

associated with the Anthropocene. Citizens need to be able to evaluate

proposals on their own terms, rather than engage in symbolic expression

of environmental concern.

In short, the Anthropocene requires the kind of cognitive processes

that is captured by the idea of enlarged thinking (Arendt 1961) writ large.

Fortunately, there is also evidence to suggest that following deliberation

28

Ethical Perspectives 21 (2014) 1

97154.indb 28 27/03/14 09:16

SIMON NIEMEYER A DEFENCE OF ( DELIBERATIVE ) DEMOCRACY

citizens often (though not always) exhibit increased awareness of multiple

value positions (Smith 2003) and can engage in integrated inter-subjective

reasoning on complex subjects, dealing with diversity in positions while

finding a way to move forward (Dryzek and Niemeyer 2006).

Hobson and Niemeyer (2011) demonstrate this ability in relation to

climate change adaptation as part of a deliberative experiment comparing

public responses to climate change under business as usual and delib-

erative settings. While exposure to information about climate change

invoked a strong response, they find that these tended to involve a short-

term reflex rather than any deep or lasting consideration of the issue.

By contrast, engaging in deliberation led to a transformation in the way

in which the issue was conceptualised. There was greater appreciation

for the nuance and complexity surrounding climate change, as well as

greater appreciation for different positions. Following deliberation, not

only was there a greater willingness to cooperate, there was also a greater

level of acceptance of individual and community responsibility for mitiga-

tion and adaptation to climate change (Hobson and Niemeyer 2011).

While these results are promising, they are not yet conclusive. The

evidence is mixed when it comes to specific benefits ascribed to delibera-

tion, such as political efficacy (Morrell 2005). There is also scepticism

regarding whether meaningful deliberation on a widespread scale is pos-

sible in practice (Rosenberg 2005), with evidence to suggest that thorough-

going deliberation including ordinary citizens is relatively rare (Rosen-

berg 2007; Mendelberg 2002). However, this is not to say that citizens

are simply incapable of behaving deliberatively engaging with alternative

arguments with an open mind (e.g. Offe 1997; Offe and Preuss 1991).

It appears that the settings in which political discussion is conducted and

the norms operating within the group play an important role in shaping

the behaviour of interlocutors, and in turn their ability to deal with com-

plex issues (Batalha et al. 2012; Niemeyer et al. 2013).

Moreover, when researchers produce findings that speak against the

possibility of deliberation, the results are often obtained in settings that

29

Ethical Perspectives 21 (2014) 1

97154.indb 29 27/03/14 09:16

ETHICAL PERSPECTIVES MARCH 2014

are not actually designed to be deliberative, in some cases stretching the

concept considerably (Steiner 2008). The same also appears to apply to

citizens willingness to participate in political deliberation (Curato and

Niemeyer 2013). In short, there is often a good deal of confusion about

what deliberation looks like and how it should be measured (Steiner

2008). To resolve this there is a need for empirical deliberative research

to inform theory and vice versa (Thompson 2008).

Thus, although overall there is promise in the evidence collected

to date, there is still a good deal of work to be done in understanding

what really happens during deliberation, what constitutes authentic

deliberation and when it actually occurs (Bchtiger et al. 2010). In light

of this, deliberative democrats need to proceed with caution, under-

standing the considerable potential in deliberation for improving global

environmental governance, while also being realistic about the limita-

tions in the state of the field (Arias-Maldonado 2007). They also need

to be aware of how deliberation works in the real world (Parkinson

2006) and be aware of the perverse consequences that this can herald

when deliberative methods are embraced, particularly where there are

high stakes (Boswell et al. 2013).

The Deliberative Democratic Person as an Environmental Citizen

Understanding the feasibility of deliberative democracy brings us back

to the key question about the capabilities of citizens from the perspective

of deliberative theory. In other words, we need to understand the delib-

erative citizen and what happens during the deliberative moment.

It turns out that the theories that underlie nudge can also explain

deliberatively induced changes, but with a different conclusion. Authen-

tic and intensive forms of deliberation appear to improve the ability of

citizens to better deal with complex issues such as climate change. This

occurs because deliberative settings not only provide the environment

in which information can be acquired, they also provide the incentive

30

Ethical Perspectives 21 (2014) 1

97154.indb 30 27/03/14 09:16

SIMON NIEMEYER A DEFENCE OF ( DELIBERATIVE ) DEMOCRACY

structure to engage with that information (Goodin and Niemeyer 2003).

The result is a shift from the primitive citizen, or, less uncharitably,

a cognitive miser, who is prone to drawing conclusions based on

intuitive modes of thinking (referred to as system I or peripheral

processing) toward deeper forms of cognition (system II or cognitive

processing).5

Here marks the important difference between deliberative democracy

and nudge theory. Deliberation ideally involves a shift from system I

to system II thinking, working through various perspectives and dealing

with the value pluralities that compete in relation to environmental issues

(Smith 2003). Nudge, on the other hand, seeks to continue to work with

system I, working with the grain of inherent flaws in everyday human

cognition and steering them in a more desirable direction (Thaler and

Sunstein 2008; John et al. 2009, 363).6

The level of cognition displayed by citizens in deliberative contexts

might not quite achieve the same standard sought by Shearman and

Smith (2007), but it is clearly possible to raise the bar in their assess-

ment of complex issues such as climate change. Deliberation does not

fundamentally change the citizen; they still have roughly the same set of

capabilities after as before (Barabas 2004). The value set of citizens is

also roughly the same, although certain values, such as concern for the

environment, have become activated as part of the process.7 What the

deliberative context appears to do is engender a set of capabilities that

are incipient, but not commonly exercised in everyday politics.

Moreover, in contrast to the alternatives discussed here, deliberation

not only has the capacity to bring to bear citizens capabilities that improve

outcomes in specific instances, it also has the potential to improve the

capacity among citizens to continue to improve the way in which they

continue to process political information. Nudge, for example, assumes

that citizens have more or less fixed preferences and will always and

inevitably remain plagued by biases and heuristics in their choices. The

experiments in deliberative democracy outlined above demonstrate that

31

Ethical Perspectives 21 (2014) 1

97154.indb 31 27/03/14 09:16

ETHICAL PERSPECTIVES MARCH 2014

this need not always be the case. And the effects are not only short-

term. Participants in deliberation experience longer-term improvements

in political efficacy and civic mindedness (Hall et al. 2011; Doheny and

ONeill 2010; Gastil et al. 2008).

Thus, it is just possible that a polity that is more deliberative not

only responds to environmental challenges more constructively, in ways

that reflect the inner desires of its citizens; it may also be able to recreate

the conditions required for proper democratic functioning. In other

words, deliberation may in turn improve the capacity for deliberative

capacity (Dryzek 2009), particularly when it comes to deliberativeness at

the level of the citizen. Authoritarian and paternalistic approaches will not

develop this capacity, perhaps even undermining the very conditions in

which citizens as passive subjects can constructively respond to complex

anthropocenic challenges, relying ever more on a fortuitously enlightened

governing elite.

V. THE PROSPECT OF DELIBERATIVE GOVERNANCE

So much for theory, and the observation of deliberation in small-scale

and highly structured settings: real world politics, of course, poses a much

more complex and problematic test for deliberative ideals (Shapiro 1999).

Deliberative democracy is beset by a number of practical problems.

There is still a good deal of work to be done by deliberative democrats

to articulate how deliberation can be achieved beyond specialised mini-

publics (Niemeyer 2014 [forthcoming]) and how public deliberation can

best be articulated with liberal democratic institutions to arrive at timely

decisions (Smith 2003). And even if these questions can be addressed,

it will take time to develop the capacity for democratic systems to develop

the deliberative capacity to deal with complex and diffuse anthropocenic

issues.

If deliberative democracy is to provide real and practical solutions

to problems of governance related to climate change, it is necessary to

32

Ethical Perspectives 21 (2014) 1

97154.indb 32 27/03/14 09:16

SIMON NIEMEYER A DEFENCE OF ( DELIBERATIVE ) DEMOCRACY

ascertain if and how it might be possible to coax polities in a more delib-

erative direction. It is simply not possible to simulate the workings of a

deliberative mini-public in ways that involve everyone affected by a deci-

sion deliberating together. For Goodin (2000), the solution is to encour-

age greater internal reflection within a deliberative system by individuals.

But this is not straightforward. As previously mentioned, exposure to the

information about climate change alone (e.g. via scenarios) certainly fails

to induce deep reflection (Hobson and Niemeyer 2011). It may be that

deliberation properly takes place in groups for a reason we are simply

hard-wired to deliberate via discussion (Mercier and Landemore 2012).

Deliberation by individuals is indeed possible (via internal discus-

sion); even desirable. But it is harder to achieve. And it may not be rea-

sonable to expect citizens to devote the cognitive resources to deliberate

deeply on every political issue they encounter. Even the most diligent

citizen cannot exhaustively consider every facet of every issue (Taylor

1981). As Offe (1997) points out, there is an opportunity cost for the

effort applied. Moreover, there is a strong question mark concerning how

easy it is to achieve deliberative modes of behaviour in anything but very

specific settings (Rosenberg 2007).

However, improving environmental outcomes may not require

achieving ideal deliberation in all sites in the public sphere, as much as

developing the capacity to avoid the distortion of public opinion by

entrenched interests who seek to nudge citizens in directions that suit

particular ends (Niemeyer 2011a). Achieving this likely involves the steady

building of deliberative capacity and development of deliberative cultures

(Rosenberg 2007; Griffin 2011), so that citizens can develop reflective

capacities and improve their resistance to political manipulation using

methods such as symbolic politics (Edelman 1985) and issue framing

(Slothuus and de Vreese 2010).

In contrast to the short time scales associated with mini-publics, the

process of developing deliberative capacity on a wider scale requires a

long-term view, involving a moral learning process (Doheny and ONeill

33

Ethical Perspectives 21 (2014) 1

97154.indb 33 27/03/14 09:16

ETHICAL PERSPECTIVES MARCH 2014

2010).8 Rosenberg (2007) argues that any such long-term strategy would

necessarily involve the use of exemplary forms of deliberation to provide

a vehicle for learning how to deliberate. The most obvious deliberative

institution in western democracies is that of parliament (Steiner et al. 2004),

but there is a question about just how deliberative these institutions are

in contemporary practice.

Where parliament fails, another possible exemplar for public delibera-

tion could be that of the mini-public (Rosenberg 2007). From a transfor-

mative perspective, it could be possible to scale up specific transformative

features of mini-publics to the polity as a whole. This can involve mini-

publics acting in a number of capacities. They can act as information

regulators. This is something that the mass media is supposed to do, by

checking different sides of the argument, synthesising and providing the

results of the analysis for public consideration, as well as exposing argu-

ments that are deceptive, against the public interest or downright untrue

at task in which it increasingly fails (Page 1996). Mini-public participants

could act to filter and synthesise the issues into a series of arguments that

are communicative (as opposed to strategic), and reflective of community

norms (Niemeyer 2014 [forthcoming]). In other words, mini-publics can

act as a trusted arbiter of public reason where mini-public deliberators

are trusted because they are people like us, rather than products of polit-

ical party machinery or journalists responding to the logic of mass media

or the directives of activist editors (MacKenzie and Warren 2012).

Beyond the use of mini-publics for scaling up deliberation, there

are potentially many ways that democratic decision making could be

democratised along deliberative lines. Smith (2003) considers a number

of options in addition to mini-publics, including mediation and stake-

holder engagement and referendums. Baber and Bartlett (2005) consider

a number of existing legal and administrative instruments such as envi-

ronmental impact assessment for their contribution to deliberativeness.

I do not have the space here to suggest options for institutional reform

extensively. In any case it is a question that remains to be thoroughly

34

Ethical Perspectives 21 (2014) 1

97154.indb 34 27/03/14 09:16

SIMON NIEMEYER A DEFENCE OF ( DELIBERATIVE ) DEMOCRACY

resolved. Where assessments have been conducted on specific institu-

tional reforms, none of these real world innovations constitute delibera-

tive capacity building in a complete sense (e.g. Smith 2003).

However, the latest turn in deliberative democracy in the form

of deliberative systems offers tantalizingly promising possibilities for

enhancing the deliberativeness of political systems. From a deliberative

systems perspective, it may not be necessary to think of deliberative

democracy in terms of single settings, institutions or innovations, but

as a whole involving specific sites that work together (Parkinson and

Mansbridge 2012).

Many of the sites that have been assessed as part of systems thinking

are more commonly associated with liberal democratic than deliberative

systems although this is not particularly new, since deliberative dem-

ocrats tend to assume liberal democratic institutions at the same time

in which they critique them (Squires 2002). In other words, it is not

necessary to think of deliberative democracy as a wholesale rethinking

of democratic institutions, but a concerted assessment of features of

the democratic system that contribute to, or undermine deliberative

capacity with the judicial deployment of methods to nudge the

system as a whole in a deliberative direction rather than individual citizens

toward particular outcomes. A deliberative system can also work in tandem

with knowledge systems, such as those that coalesce around ques-

tions involving the Anthropocene, with improved sites for transferring

knowledge in both directions (Christiano 2012) and possibly, again, via

mini-publics, among other mechanisms.

The idea of deliberative systems is at the very early stage of advance-

ment, but it brings considerable opportunity. The concept of deliberative

systems can be used as a framework for understanding the sources and

generators of deliberative capacity and the relationship between them

and democratic institutions (Niemeyer 2014 [forthcoming]). And, like the

economics that ultimately informed nudge theory, it can be used to

develop research on the nature of the deliberative person, which builds a

35

Ethical Perspectives 21 (2014) 1

97154.indb 35 27/03/14 09:16

ETHICAL PERSPECTIVES MARCH 2014

comprehensive picture of the deliberative capabilities of citizens within the

deliberative system as a whole (Niemeyer 2011b, 2014 [forthcoming]).9

However, doing so will take time, which might be problematic in terms

of governing in the face of the Anthropocene.

VI. ANTHROPOCENIC URGENCY AND DELIBERATIVE GOVERNANCE

The term Anthropocene connotes a time frame of human activities on

a geological scale, but those who identify its challenges also tend to

emphasise the need for quick and decisive action to forestall future

impacts in the light of positive environmental feedback (with strongly

negative consequences).

In light of the need for more development of green deliberative

theory, advocating more deliberative forms of governance in the Anthro-

pocene could seem at best ineffective and, at worst, a dangerous luxury.

However, if we are to take seriously the long-term challenge of living in

a global environmental system involving complex feedback and connec-

tions with economic and socio-political systems, then there is a strong

case for finding mechanisms that improve anticipation and response

within those systems along democratic lines to avoid the confidence trap

of democracy alluded to above (Runciman 2013).

In this contribution I have tended to focus on the public and their

capacity to understand the nature of the challenge posed by the Anthro-

pocene. This is based on the premise that citizens, irrespective of the

overarching system of governance, must support meaningful action.

Whether or not this understanding via deliberative mechanisms would

lead directly to behaviour change by citizens is a relatively open ques-

tion although there is promising evidence to support the possibility

of improved pro-environmental behaviours associated with deliberation

(e.g. Hobson 2003).

And although it seems that deliberation improves political choices

in an environmental sense, I would also stress that such support is not

36

Ethical Perspectives 21 (2014) 1

97154.indb 36 27/03/14 09:16

SIMON NIEMEYER A DEFENCE OF ( DELIBERATIVE ) DEMOCRACY

unqualified, as good deliberation means that citizens consider compet-

ing values (Smith 2003). However, rather than being a weakness, this

is the strength of the approach. It involves a more measured approach

to public issues and adopting a wider view. And the understanding that

is developed may not (and perhaps should not) lead to consensus per

se, it does produce a situation where mutual understanding renders

political issues more tractable (Dryzek and Niemeyer 2006; Gutmann

and Thompson 1996).

A deliberative polity might even endorse strategies that borrow

from nudge theory to facilitate behavioural change. Thus citizens can

consent to the use of nudge in ways that may actually improve its efficacy

perhaps where endorsement improves buy-in, although this is some-

thing that would require empirical clarification. At the very least, the

public debate regarding the use of nudge will make salient the reasons for

implementing such strategies.

Building deliberative capacity in democratic systems, including among

citizens, will take time, but it is also possible to incrementally improve

the deliberativeness of existing institutions, capture the opportunities

provided by specifically deliberative innovations such as mini-publics,

and identify those features of democratic systems that impede delibera-

tiveness. This is something that can begin immediately.

VII. CONCLUDING COMMENTS

Deliberative democracy, which began as a normative theory, has the

potential to transform the public response to challenges posed by the

Anthropocene, which are large in scale, crossing political boundaries and

complex, involving multiple feedback mechanisms and often temporally

displaced.

The approach is not without its weaknesses, but it is the least-worst

among the alternatives, particularly from a longer-term point of view.

Although the evidence is mixed, many studies suggest that improving the

37

Ethical Perspectives 21 (2014) 1

97154.indb 37 27/03/14 09:16

ETHICAL PERSPECTIVES MARCH 2014

deliberativeness of decision making in respect to challenges posed by

Anthropocene brings considerable potential benefits in producing citizens

that are responsive to the complexity of the task, inclusive of competing

considerations and attuned to the temporal dimension of environmental

challenges.

Certainly, achieving deliberation in real world politics is exceedingly

challenging, at least in prevailing political settings. But, arguably, it is not

impossible. Although there is more that needs to be done to understand

the nature of deliberation and the institutions that facilitate it, a delibera-

tive systems point of view opens up possibilities for incremental changes

that could help nudge the system as a whole in a deliberative direction.

Although deliberative democracy might be difficult to achieve perhaps

even elusive in any ideal sense there is potential for feedback within the

deliberative system where good examples of deliberation contribute to

further improvement in deliberative capacity.

WORKS CITED

Akerlof, Karen and Chris Kennedy. 2013. Nudging Toward a Healthy Natural Environment:

How Behavioural Change Research can Inform Conservation. Fairfax, VA: George Mason

University, Centre for Climate Change Communication.

Arendt, Hannah. 1961. Between Past and Future: Six Exercises in Political Thought. London:

Faber and Faber.

Arias-Maldonado, Manuel. 2007. An Imaginary Solution? The Green Defence of Delib-

erative Democracy. Environmental Values 16/2: 233-252.

Baber, Walter F. and Robert V. Bartlett. 2005. Deliberative Environmental Politics: Democracy

and Ecological Rationality. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Bchtiger, Andr, Simon Niemeyer, Michael Neblo, Marco R. Steenbergen and Jrg

Steiner. 2010. Disentangling Diversity in Deliberative Democracy: Competing

Theories, Their Empirical Blind-Spots, and Complementarities. Journal of Political

Philosophy 18/1: 32-63.

Barabas, Jason. 2004. How Deliberation Affects Policy Opinions. American Political

Science Review 98/4: 687-701.

Batalha, Luisa, Simon John Niemeyer, Nicole Curato and John S. Dryzek. 2012. Group

Dynamics and Deliberative Processes: Affective and Cognitive Aspects. Annual

Scientific Meeting of the International Society of Political Psychology, Chicago, IL,

July 69. http://tinyurl.com/o4of5fy [accessed February 1, 2013].

38

Ethical Perspectives 21 (2014) 1

97154.indb 38 27/03/14 09:16

SIMON NIEMEYER A DEFENCE OF ( DELIBERATIVE ) DEMOCRACY

Beeson, Mark. 2010. The Coming of Environmental Authoritarianism. Environmental

Politics 19/2: 276-294.

Besdted, Bjrn and Lars Klver. 2009. World Wide Views on Global Warming: From the

Worlds Citizens to Climate Policy Makers. Copenhagen: Danish Board of Technology.

http://wwviews.org/files/AUDIO/WWViews Policy Report FINAL Web

version.pdf.

Biermann, Frank. 2007. Earth System Governance as a Crosscutting Theme of Global

Change Research. Global Environmental Change 17/3-4: 326-337.

Blake, James. 1999. Overcoming the Value-Action Gap in Environmental Policy:

Tensions Between National Policy and Local Experience. Local Environment 4/3:

257-278.

Blatter, Joachim. 2009. Performing Symbolic Politics and International Environmental

Regulation: Tracing and Theorizing a Causal Mechanism Beyond Regime Theory.

Global Environmental Politics 9/4: 81-110.

Boswell, John, Simon John Niemeyer and Carolyn M. Hendricks. 2013. Julia Gillards

Citizens Assembly Proposal for Australia: A Deliberative Democratic Analysis.

Australian Journal of Political Science 48/2: 164-178.

Burnell, Peter. 2012. Democracy, Democratization and Climate Change: Complex Rela-

tionships. Democratization 19/5: 813-842.

Chambers, Simone. 2003. Deliberative Democratic Theory. Annual Review of Political

Science 6: 307-326.

Christiano, Thomas. 2012. Rational Deliberation Among Experts and Citizens. In

Deliberative Systems: Deliberative Democracy at the Large Scale. Edited by John Parkinson

and Jane J. Mansbridge, 27-51. Cambridge, Cambridge University Press.

Coorey, Phillip. 2010. Climate Policy Backlash Takes Shine Off Rudd. Sydney Morning

Herald. February 8, 2010. http://www.smh.com.au/environment/climate-change/

climate-policy-backlash-takes-shine-off-rudd-20100207-nkxc.html [accessed Novem-

ber 20, 2011].

Crutzen, Paul J. 2002. Geology of Mankind. Nature 415/6867: 23.

Crutzen, Paul and Eugene F. Stoermer. 2000. The Anthropocene. Global Change News-

letter 41: 17-18.

Curato, Nicole and Simon John Niemeyer. 2013. Reaching Out to Overcome Political

Apathy: Building Participatory Capacity through Deliberative Engagement. Politics

& Policy 41/3: 355-383.

Doheny, Shane and Claire ONeill. 2010. Becoming Deliberative Citizens: The Moral

Learning Process of the Citizen Juror. Political Studies 58/4: 630-648.

Dryzek, John S. 1987. Rational Ecology: Environment and Political Ecology. New York: Black-

well.

Dryzek, John S. 1990. Discursive Democracy: Politics, Policy and Political Science. Cambridge:

Cambridge University Press.

Dryzek, John S. 1995. Political and Ecological Communication. Environmental Politics 4:

13-30.

39

Ethical Perspectives 21 (2014) 1

97154.indb 39 27/03/14 09:16

ETHICAL PERSPECTIVES MARCH 2014

Dryzek, John S. 2009. Democratization as Deliberative Capacity Building. Comparative

Political Studies 42/11: 1379-1402.

Dryzek, John S. and Simon John Niemeyer. 2006. Reconciling Pluralism and Consen-

sus as Political Ideals. American Journal of Political Science 50/3: 634-649.

Dryzek, John S. and Simon John Niemeyer. 2008. Discursive Representation. American

Political Science Review 102/4: 481-494.

Dryzek, John S., Richard B. Norgaard and David Schlosberg. 2013. Climate Challenged

Society. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Edelman, Murray J. 1985. The Symbolic Uses of Politics. Urbana, IL: University of Illinois Press.

Fukuyama, Francis. 1992. The End of History and the Last Man. New York: Free Press.

Fung, Archon. 2003. Recipes for Public Spheres: Eight Institutional Design Choices

and their Consequences. Journal of Political Philosophy 113: 338-367.

Gastil, John, Laura W. Black, E. Pierre Deess and Jay Leighter. 2008. From Group

Member to Democratic Citizen: How Deliberating with Fellow Jurors Reshapes

Civic Attitudes. Human Communication Research 34: 137-169.

Giddens, Anthony. 2009. The Politics of Climate Change. Cambridge, MA: Polity.

Gill, James D., Lawrence A. Crosby and James R. Taylor. 1986. Ecological Concern,

Attitudes, and Social Norms in Voting Behaviour. Public Opinion Quarterly 50: 537-

554.

Gilley, Bruce. 2012. Authoritarian Environmentalism and Chinas Response to Climate

Change. Environmental Politics 21/2: 287-307.

GlobeScan Radar. 2013. Environmental Concerns at Record Lows: Global Poll.

http://www.globescan.com/commentary-and-analysis/press-releases/press-

releases-2013/98-press-releases-2013/261-environmental-concerns-at-record-lows-

global-poll.html [accessed October 8, 2013].

Goodin, Robert E. 1992. Green Political Theory. Oxford: Polity.

Goodin, Robert E. 1996. Enfranchising the Earth and its Alternatives. Political Studies

44/5: 835-849.

Goodin, Robert E. 2000. Democratic Deliberation Within. Philosophy and Public Affairs

29/1: 81-109.

Goodin, Robert E. and Simon John Niemeyer. 2003. When Does Deliberation Begin?

Internal Reflection Versus Public Discussion in Deliberative Democracy. Political

Studies 51/4: 627-649.

Griffin, Martyn. 2011. Developing Deliberative Minds: Piaget, Vygotsky and the Delib-

erative Democratic Citizen. Journal of Public Deliberation 7/1: 1-28.

Gunderson, Adolf G. 1995. Environmental Promise of Democratic Deliberation. Madison, WI.

University of Wisconsin Press.

Gutmann, Amy and Dennis F. Thompson. 1996. Democracy and Disagreement. Cambridge,

MA: Belknap.

Hall, Troy E., Patrick Wilsony and Jennie Newman. 2011. Evaluating the Short- and

Long-term Effects of a Modified Deliberative Poll on Idahoans Attitudes and Civic

Engagement Related to Energy Options. Journal of Public Deliberation 7/1: Article 6.

40

Ethical Perspectives 21 (2014) 1

97154.indb 40 27/03/14 09:16

SIMON NIEMEYER A DEFENCE OF ( DELIBERATIVE ) DEMOCRACY

Hansen, Fergus. 2010. The Lowy Institute Poll 2010: Australia and the World, Public Opinion

and Foreign Policy. Sydney: The Lowy Institute. http://lowyinstitute. org/Publication.

asp?pid=1305 [accessed March 1,2012].

Hansen, Pelle Guldborg and Andreas Maale Jespersen. 2013. Nudge and the Manip-

ulation of Choice: A Framework for the Responsible Use of the Nudge Approach

to Behaviour Change in Public Policy. European Journal of Risk Regulation 1: 3-28.

Hayward, Tim. 1997. Anthropocentrism: A Misunderstood Problem. Environmental

Values 6: 49-63.

He, Baogang and Mark E. Warren. 2011. Authoritarian Deliberation: The Deliberative

Turn in Chinese Political Development. Perspectives on Politics 9/2: 269-289.

Hobson, Kersty. 2013. On the Making of the Environmental Citizen. Environmental

Politics 22/1: 56-72.

Hobson, Kersty Pamela. 2003. Thinking Habits into Action: The Role of Knowledge

and Process in Questioning Household Consumption Practices. Local Environ-

ment 8/1: 95-112.

Hobson, Kersty Pamela and Simon John Niemeyer. 2011. Public Responses to Climate

Change: The Role of Deliberation in Building Capacity for Adaptive Action.

Global Environmental Change 21: 957-971.

Hobson, Kersty Pamela and Simon John Niemeyer. 2013. What Do Climate Sceptics

Believe? Discourses of Scepticism and their Response to Deliberation. Public

Understanding of Science 22/4: 396-412.

John, Peter, Graham Smith and Gerry Stoker. 2009. Nudge Nudge, Think Think: Two

Strategies for Changing Civic Behaviour. Political Quarterly 80/3: 361-370.

Karlsson, Rasmus. 2013. Ambivalence, Irony, and Democracy in the Anthropocene.

Futures 46: 1-9.

Leib, Ethan and Baogang He. 2006. The Search for Deliberative Democracy in China. New

York: Palgrave Macmillan.

MacKenzie, Michael K. and Mark E. Warren. 2012). Two Trust-Based Uses of Mini-

Publics in Democratic Systems. In Deliberative Systems: Deliberative Democracy at the

Large Scale. Edited by John Parkinson and Jane J. Mansbridge, 95-124. Cambridge,

Cambridge University Press.

Manin, Bernard. 1987. On Legitimacy and Political Deliberation. Political Theory 15/3:

338-368.

Meadowcroft, James. 2007. Who is in Charge Here? Governance for Sustainable Devel-

opment in a Complex World. Journal of Environmental Policy & Planning 9/3-4:

299-314.

Mendelberg, Tali. 2002. The Deliberative Citizen: Theory and Evidence. Political Deci-

sion Making, Deliberation and Participation 6: 151-193.

Mercier, Hugo and Helene E. Landemore. 2012. Reasoning is for Arguing: Understand-

ing the Successes and Failures of Deliberation. Political Psychology 33/2: 243-258.

Morrell, Michael E. 2005. Deliberation, Democratic Decision-Making and Internal

Political Efficacy. Political Behavior 27/1: 49-69.

41

Ethical Perspectives 21 (2014) 1

97154.indb 41 27/03/14 09:16

ETHICAL PERSPECTIVES MARCH 2014

Niemeyer, Simon J., Judith Petts and Kersty P. Hobson. 2005. Rapid Climate Change

and Society: Assessing Responses and Thresholds. Risk Analysis 25/6: 1443-1456.

Niemeyer, Simon J. 2004. Deliberation in the Wilderness: Displacing Symbolic Politics.

Environmental Politics 13/2: 347-372.

Niemeyer, Simon J. 2011a. The Emancipatory Effect of Deliberation: Empirical Lessons

from Mini-Publics. Politics & Society 39/1: 103-140.

Niemeyer, Simon J. 2011b. In Search of the Deliberative Person: Building the Founda-

tions of a Deliberative System and the Implications for Climate Change Gover-

nance. ECPR General Conference. Reykjavic. http://www.ecprnet.eu/ conferences/

general_conference/reykjavik/paper_details.asp?paperid=4127 [accessed March 1,

2012].

Niemeyer, Simon J. 2014. Scaling Up Deliberation to Mass Publics: Harnessing Mini-

publics in a Deliberative System. In Deliberative Mini-Publics: Practices, Promises, Pitfalls.

Edited by Kimmo Grnlund, Andr Bchtiger and Maija Setl. Colchester: ECPR

Press (forthcoming).

Niemeyer, Simon J., Luisa Batalha and John S. Dryzek. 2013. Changing Dispositions

to Australian Democracy in the Course of the Citizens Parliament. In The

Australian Citizens Parliament and the Future of Deliberative Democracy. Edited by

Lyn Carson and John Gastil. University Park, PA: Pennsylvania State University

Press.

Niemeyer, Simon J. and John S. Dryzek. 2007. The Ends of Deliberation: Metacon-

sensus and Intersubjective Rationality as Deliberative Ideals. Swiss Political Science

Review 13/4: 497-526.

Offe, Claus. 1997. Micro Aspects of Democratic Theory: What Makes for the Delib-

erative Competence of Citizens? In Democracys Victory and Crisis. Edited by Axel

Hadenius, 81-104. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Offe, Claus and Ulrich K. Preuss. 1991. Democratic Institutions and Moral Resources.