Professional Documents

Culture Documents

The Sophists Philosophy

The Sophists Philosophy

Uploaded by

WASIQUECopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

The Sophists Philosophy

The Sophists Philosophy

Uploaded by

WASIQUECopyright:

Available Formats

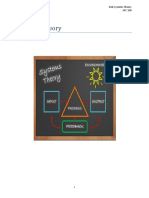

The Sophists

The second period of philosophy opens, in the Sophists, with the problem of the position of man in the universe.

The teaching of the earlier philosophers was exclusively cosmological, that of the Sophists exclusively

humanistic. Later in this second period, these two modes of thought come together and fructify one another. The

problem of the mind and the problem of nature are subordinated as factors of the great, universal, all-embracing,

world-systems of Plato and Aristotle.

It is not possible to understand the activities and teaching of the Sophists without some knowledge of the

religious, political, and social conditions of the time. After long struggles between the people and the nobles,

democracy had almost everywhere triumphed. But in Greece democracy did not mean what we now mean

by{107} that word. It did not mean representative institutions, government by the people through their elected

deputies. Ancient Greece was never a single nation under a single government. Every city, almost every hamlet,

was an independent State, governed only by its own laws. Some of these States were so small that they

comprised merely a handful of citizens. All were so small that all the citizens could meet together in one place,

and themselves in person enact the laws and transact public business. There was no necessity for representation.

Consequently in Greece every citizen was himself a politician and a legislator. In these circumstances, partisan

feeling ran to extravagant lengths. Men forgot the interests of the State in the interests of party, and this ended in

men forgetting the interests of their party in their own interests. Greed, ambition, grabbing, selfishness,

unrestricted egotism, unbridled avarice, became the dominant notes of the political life of the time.

The teaching of the Sophists was merely a translation into theoretical propositions of these practical tendencies

of the period. The Sophists were the children of their time, and the interpreters of their age. Their philosophical

teachings were simply the crystallization of the impulses which governed the life of the people into abstract

principles and maxims.

Who and what were the Sophists? In the first place, they were not a school of philosophers. They are not to be

compared, for example, with the Pythagoreans or{109} Eleatics. They had not, as a school has, any system of

philosophy held in common by them all. None of them constructed systems of thought. They had in common

only certain loose tendencies of thought. They were a professional class rather than a school, and as such they

were scattered over Greece, and nourished among themselves the usual professional rivalries. They were

professional teachers and educators. The rise of the Sophists was due to the growing demand for popular

education, which was partly a genuine demand for light and knowledge, but was mostly a desire for such

spurious learning as would lead to worldly, and especially political, success.

Any man could rise to the highest positions in the State, if he were endowed with cleverness, ready speech,

whereby to sway the passions of the mob, and a sufficient equipment in the way of education. Hence the

demand arose for such an education as would enable the ordinary man to carve out a political career for himself.

It was this demand which the Sophists undertook to satisfy.

They wandered about Greece from place to place, they gave lectures, they took pupils, they entered into

disputations. For these services they exacted large fees. They were the first in Greece to take fees for the

teaching of wisdom. There was nothing disgraceful in this in itself, but it had never been customary. The wise

men of Greece had never accepted any payment for their wisdom. Socrates, who never accepted any

payment, {110} but gave his wisdom freely to all who sought it, somewhat proudly contrasted himself with the

Sophists in this respect.

The Sophists were not, technically speaking, philosophers. They did not specialise in the problems of

philosophy. Their tendencies were purely practical. They taught any subject whatever for the teaching of which

there was a popular demand. For example, Protagoras undertook to impart to his pupils the principles of success

as a politician or as a private citizen.

In consequence of this practical tendency of the Sophists we hear of no attempts among them to solve the

problem of the origin of nature, or the character of the ultimate reality. The Sophists have been described as

teachers of virtue, and the description is correct, provided that the word virtue is understood in its Greek sense,

which did not restrict it to morality alone. For the Greeks, it meant the capacity of a person successfully to

perform his functions in the State. Thus the virtue of a mechanic is to understand machinery, the virtue of a

physician to cure the sick, the virtue of a horse trainer the ability to train horses. The Sophists undertook to train

men to virtue in this sense, to make them successful citizens and members of the State.

They were the first to direct attention to the science of rhetoric, of which they may be considered the founders.

But their rhetoric also had its bad side, which indeed, soon became its only side. The aims of the young

politicians whom they trained were, not to seek out the truth for its own sake, but merely to persuade the

multitude of whatever they wished them to believe. Consequently the Sophists, like lawyers, not caring for the

truth of the matter, undertook to provide a stock of arguments on any subject, or to prove any proposition. They

boasted of their ability to make the worse appear the better reason, to prove that black is white

You might also like

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5835)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1093)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (852)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (590)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (903)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (541)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (350)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (824)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (122)

- H. Richard Niebuhr On Culture - Christ and CultureDocument13 pagesH. Richard Niebuhr On Culture - Christ and CultureDrasko100% (5)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (405)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- CSS General Ability Study Material by Sir SabirDocument70 pagesCSS General Ability Study Material by Sir SabirWASIQUE67% (6)

- Essay WritingDocument20 pagesEssay Writingerinea08100167% (3)

- Science Fiction and Cultural HistoryDocument14 pagesScience Fiction and Cultural Historyfrancisco pizarroNo ratings yet

- Rights of Prisoners in The Perspective of Pakistani and International LawDocument14 pagesRights of Prisoners in The Perspective of Pakistani and International LawWASIQUENo ratings yet

- Plato Educational TheoryDocument4 pagesPlato Educational TheoryWASIQUENo ratings yet

- Inductive Reasoning and TypesDocument7 pagesInductive Reasoning and TypesWASIQUENo ratings yet

- IQBAL PhilosophyDocument6 pagesIQBAL PhilosophyWASIQUE100% (1)

- Law and Morality in H.L.a. Harts Legal PhilosophyDocument18 pagesLaw and Morality in H.L.a. Harts Legal PhilosophyAnonymous pzLjl4jNo ratings yet

- 1 Scivive Outline IntroDocument12 pages1 Scivive Outline IntroMan CosminNo ratings yet

- Relevance and Effort - A Paper For DiscussionDocument7 pagesRelevance and Effort - A Paper For DiscussionMarta QBNo ratings yet

- BGSDocument15 pagesBGSKhan RohitNo ratings yet

- Second POSC EssayDocument5 pagesSecond POSC EssayRedfinNo ratings yet

- Weintraub The Theory and Politics of The Public Private DistinctionDocument23 pagesWeintraub The Theory and Politics of The Public Private DistinctionEsraCanNo ratings yet

- ST - AUGUSTINE, JOHN LOCKE, RENE DESCARTéSDocument4 pagesST - AUGUSTINE, JOHN LOCKE, RENE DESCARTéSZer John GamingNo ratings yet

- Developing Higher Order Thinking PresentationDocument12 pagesDeveloping Higher Order Thinking Presentationsollu786_8891631490% (1)

- Detienne & Vernant - Cunning IntelligenceDocument342 pagesDetienne & Vernant - Cunning IntelligenceMani Insanguinate100% (1)

- Mrr4 VenturaDocument2 pagesMrr4 VenturaJames Brian VenturaNo ratings yet

- Quijano ST., San Juan, San Ildefonso BulacanDocument3 pagesQuijano ST., San Juan, San Ildefonso Bulacanmaroons_01No ratings yet

- The Origin of The JivaDocument125 pagesThe Origin of The JivaDay FriendsNo ratings yet

- Basic Skills Required For GD: Group Discussion Basic TipsDocument4 pagesBasic Skills Required For GD: Group Discussion Basic Tipsroja sujatha s bNo ratings yet

- Mystery StoriesDocument5 pagesMystery Storiesgayathri_seshadriNo ratings yet

- Planning Theory, DR Micahel Elliot, Georgia TechDocument23 pagesPlanning Theory, DR Micahel Elliot, Georgia TechChandra BhaskaraNo ratings yet

- Definition of EssayDocument3 pagesDefinition of EssayJan Mikel RiparipNo ratings yet

- The Sacred Music of IslamDocument26 pagesThe Sacred Music of IslamShahid.Khan1982No ratings yet

- Values Ethics & MoralsDocument4 pagesValues Ethics & Moralspaku deyNo ratings yet

- Siddhartha (Hermann Hesse) (Z-Library)Document112 pagesSiddhartha (Hermann Hesse) (Z-Library)otimasvreiNo ratings yet

- भारत क्या है - -HindiDocument54 pagesभारत क्या है - -HindiSalil GewaliNo ratings yet

- Module 7Document34 pagesModule 7Baher WilliamNo ratings yet

- Realism in EducationDocument32 pagesRealism in EducationRhoa Bustos100% (1)

- Brahmajala Sutra - Maung PawDocument68 pagesBrahmajala Sutra - Maung PawhyakuuuNo ratings yet

- Doc2 CourseheroDocument1 pageDoc2 CourseheroKrystel TungpalanNo ratings yet

- Focolare The Work of Mary-Is It Good For CatholicsDocument59 pagesFocolare The Work of Mary-Is It Good For CatholicsFrancis LoboNo ratings yet

- Systems Theory PaperDocument9 pagesSystems Theory PapermjointNo ratings yet

- Vibration by Dr. Ann DaviesDocument2 pagesVibration by Dr. Ann DaviesLuke R. Corde78% (9)