Professional Documents

Culture Documents

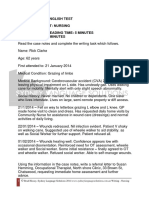

Part B-13-Night Shift Sleep

Part B-13-Night Shift Sleep

Uploaded by

fernanda1rondelliOriginal Description:

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Part B-13-Night Shift Sleep

Part B-13-Night Shift Sleep

Uploaded by

fernanda1rondelliCopyright:

Available Formats

Medical staff working the night shift: can naps help?

R Doug McEvoy and Leon L Lack

MJA 2006; 185 (7): 349-350

Napping at night may benefit both health professionals and their patients

Delivering medical care is a 24-hour business that inevitably involves working the

night shift. However, night shift requires the health professional to work when the

body’s clock (circadian system) demands sleep. Added to this is the problem of “sleep

debt”, arising from both prolonged prior wakefulness on the first night shift and

cumulative sleep debt after several nights’ work and repeated unsatisfactory daytime

sleeps. A further aggravation, particularly for trainee medical staff in teaching

hospitals, has been the demand for excessive work hours across the working week. As

has been dramatically shown in recent well controlled studies, the net result of this

assault on the sleep of health professionals can be impaired patient safety, and the

health and safety of health professionals themselves.

The good news is that health organisations and regulators are beginning to treat the

matter seriously. In Australia, the United States and Europe, work hours of medical

staff have recently been shortened by government regulation, and bodies such as the

Australian Medical Association and professional colleges are advising their members

on strategies to improve their sleep health and thus work safety. A recent publication

prepared by the Royal College of Physicians (London) (RCP), Working the night

shift: preparation, survival and recovery. A guide for junior doctors, is an excellent

example. One proposed countermeasure for excessive sleepiness is the use of

strategically placed naps both before and during the night shift. But does napping

either before or during the night shift reduce sleepiness and improve performance, and,

if so, how practical is it?

There are two important, independent mechanisms of sleep and sleepiness that hold

the key to these questions. Probably the more potent mechanism impairing night-shift

alertness is the circadian system. For most individuals, even those working permanent

night shift, the circadian system is in sleep mode during the night. This causes slowed

reactions, increased feelings of fatigue, impaired concentration, and increased sleep

propensity. The second important mechanism affecting night-time alertness is

homeostatic sleep drive. This increases in intensity the longer we are awake and, like

appetite which is sated by eating, homeostatic sleep drive is reduced by sleeping. If

the first night shift starts at midnight following a normal wake time at about 8 am,

about 16 hours of wake sleep debt has already been accrued and the rest of the night

shift will be performed under intense homeostatic, in addition to circadian, sleep drive.

Performance decrements during this night period can be similar to those measured in

the daytime with a blood alcohol concentration of 0.05%–0.10%. Day sleep in the

home environment is likely to be shorter and less effective than night sleep so, even

though second and subsequent night shifts may follow fewer wakeful hours (8–

10 hours), homeostatic sleep drive is likely to remain elevated during night shifts

because of incomplete repayment of the previous sleep debt.

To a limited extent, it is possible to “bank” sleep (or pay off residual sleep debt)

before the first night shift, potentially reducing subsequent night-time homeostatic

sleep drive and improving alertness and work safety. A long (1–2 hours) nap in the

afternoon, as recommended in the RCP report, is best. Afternoon sleep is more

efficient than early evening sleep as it uses the natural afternoon “dip” in circadian

physiology and avoids the risk of post-sleep grogginess or sleep inertia impinging on

the start of night duty. Between subsequent night shifts, the aim should be to

maximise daytime sleep length (at least 7 hours) and efficiency by including the

afternoon sleepy period (1–4 pm).

What about napping during a night shift to improve alertness and reduce errors and

accidents? Brief afternoon naps of 10–30 minutes (so-called power naps) improve

alertness and performance. We compared afternoon naps of 5, 10, 20, and 30 minutes

of total sleep. The 10 minute sleep (about a 15 minute nap opportunity) produced

improvements over the 3 hour post-nap period in all eight alertness and performance

measures, without any of the post-nap impairment of sleep inertia that followed the

20 and 30 minute naps. Whether these results would be replicated at, say, 3 am in a

night-shift environment, with considerably greater homeostatic and circadian sleep

drive, is now being tested.

Only a few studies have measured the effects of night-shift napping. Long naps of

about 2 hours appear as effective at about 3 am as at 3 pm. However, 1–2 hour naps

were followed by sleep inertia, during which alertness was impaired for up to an hour.

Longer naps, although beneficial once sleep inertia has been dissipated, may be used

reluctantly by medical staff wishing to maintain continuity of patient care. Briefer

naps (18–26 minutes) have also improved performance in night-shift environments.

Therefore, the picture emerging from night-shift napping studies is similar to that

from the afternoon studies. Very brief naps (10–15 minutes of sleep) may improve

alertness immediately without the negative effects of sleep inertia. How long this

improvement lasts and what is the optimal nap length on the night shift remains to be

determined.

In the meantime, as recommended in the recent RCP guide, health professionals who

work night shift should, for the sake of their own health and safety and that of their

patients, consider the benefits of night-shift napping. Optimal benefit and a higher

take-up rate are likely for sleep lengths of 10–15 minutes.

OET reading style questions

Medical staff & the night shift

1. Which of the following is not mentioned a cause of sleep debt?

a) Regular lack of sleep during the day

b) Staying awake for a long period before the first night shift

c) Poor health among health professionals

d) A build up of sleep debt during the night shift period

2. Which of the following statements is not mentioned?

a) Lack of sleep among health professionals can affect the safe treatment of patients

b) Lack of sleep among health professionals can affect the health of health professionals

c) Long hours are very common for trainee medical staff

d) Most health professionals don’t get adequate sleep

3. According to the article which of the following statement is false?

a) people who work the night shift during sleep mode may have increased appetite

b) people who work the night shift during sleep mode may feel exhausted

c) people who work the night shift during sleep mode may be unable to keep their mind

on the job

d) people who work the night shift during sleep mode may respond slowly to certain

situations

4. Which of the following statements is true?

a) It is beneficial to sleep between 1~4PM

b) If you sleep in the early evening you will be fully alert at work

c) Do not sleep more than 7 hours during the day before your night shift

d) All of the above

5. Recent studies have shown that

a) Long 2 hour naps are more beneficial at night

b) Short naps are equally effective at night as they are during the day

c) Short daytime naps are less beneficial than longer daytime naps

d) none of the above

6. Overall the purpose of the article is to explain that

a) Health professionals don’t get enough sleep

b) Both short and long naps during night shift will improve work performance and

patient treatment

c) Short naps during night shift may be the best way to improve work performance and

patient treatment

d) Tired health professionals are less efficient than alert health professionals

Understanding meaning from context

Use you’re the online dictionary http://www.ldoceonline.com/ to help you

understand the vocabulary below.

1. cumulative sleep debt

2. a countermeasure

3. grogginess

4. sleep inertia

5. impinge on

6. to replicate

7. dissipate

Answer Sheet

Question 1

a) Incorrect: Mentioned: repeated unsatisfactory daytime sleeps

b) Incorrect: Mentioned: prolonged prior wakefulness on the first night shift

c) Correct: Not mentioned

d) Incorrect: Mentioned: cumulative sleep debt after several nights’ work

Question 2

a) Incorrect: Mentioned the net result of this assault on the sleep of health professionals can be impaired patient safety,

b) Incorrect: Mentioned ….and the health and safety of health professionals themselves.

c) Incorrect: Mentioned… A further aggravation, particularly for trainee medical staff in teaching hospitals, has been the

demand for excessive work hours across the working week

d) Correct: Not Mentioned

Question 3

a) Correct: False

b) Incorrect: True: increased feelings of fatigue, and increased sleep propensity.

c) Incorrect: True: impaired concentration

d) Incorrect: True: slowed reactions

Question 4

a) Correct: True Between subsequent night shifts, the aim should be to maximise daytime sleep length…..by including

the afternoon sleepy period (1–4 pm).

b) Incorrect:

c) Incorrect

d) Incorrect

Question 5

a) Incorrect:.. of equal benefit

b) Correct: Therefore, the picture emerging from night-shift napping studies is similar to that from the afternoon

studies

c) Incorrect

d) Incorrect:

Question 6

a) Incorrect

b) Incorrect:

c) Correct: Optimal benefit and a higher take-up rate are likely for sleep lengths of 10–15 minutes.

d) Incorrect:

You might also like

- HARVARD MEDICAL Improving Sleep - A Guide To A Good Nights Rest PDFDocument53 pagesHARVARD MEDICAL Improving Sleep - A Guide To A Good Nights Rest PDFdarioarrus79% (14)

- 3BIdMvM5TsW9Xy8kMzZu Baby 4-18 Mo Sleep Guide Baby Sleep Dr. 2021Document98 pages3BIdMvM5TsW9Xy8kMzZu Baby 4-18 Mo Sleep Guide Baby Sleep Dr. 2021dragana novakovic100% (1)

- Is This Statement True or False?: Flag Question: Question 2Document19 pagesIs This Statement True or False?: Flag Question: Question 2Anh Duong Ngoc LanNo ratings yet

- ELC 590 Persuasive SpeechDocument6 pagesELC 590 Persuasive SpeechMohd Zuhairi78% (9)

- Mental Model ExercisesDocument3 pagesMental Model ExercisesAzzam Sabtu100% (1)

- Reading Part A ShinglesDocument6 pagesReading Part A Shinglesfernanda1rondelliNo ratings yet

- Final Marketing Plan BriefDocument40 pagesFinal Marketing Plan Briefapi-285971831100% (1)

- Sleep Pattern DisturbanceDocument4 pagesSleep Pattern DisturbanceVirusNo ratings yet

- Model LettersDocument10 pagesModel Lettersfernanda1rondelli75% (4)

- Model LettersDocument10 pagesModel Lettersfernanda1rondelli75% (4)

- Reading Part A Hip FracturesDocument6 pagesReading Part A Hip Fracturesfernanda1rondelliNo ratings yet

- The Shortcut To SuccessDocument70 pagesThe Shortcut To SuccessAndrew WilliamsNo ratings yet

- Ifa 3 - Students Pack Extra ExercisesDocument28 pagesIfa 3 - Students Pack Extra ExercisesSusana Castro Gil0% (1)

- Test Bank For Pathophysiology Concepts of Human Disease 1st Edition Matthew Sorenson Lauretta Quinn Diane KleinDocument21 pagesTest Bank For Pathophysiology Concepts of Human Disease 1st Edition Matthew Sorenson Lauretta Quinn Diane Kleinedwardfrostxpybgdctkr100% (27)

- 14 Study Guide - SleepDocument4 pages14 Study Guide - SleepHeart FerriolNo ratings yet

- The Ultimate Sleep Optimization Guide - Oliva HealthDocument33 pagesThe Ultimate Sleep Optimization Guide - Oliva HealthJoe Heyob0% (1)

- Refresh For Staying FitDocument47 pagesRefresh For Staying FitilkoltuluNo ratings yet

- "Sleep Hygiene" The Gateway For Efficient Sleep: A Brief ReviewDocument4 pages"Sleep Hygiene" The Gateway For Efficient Sleep: A Brief ReviewFrontiersNo ratings yet

- Outline Informative Speech FinalDocument5 pagesOutline Informative Speech Finalapi-664220760No ratings yet

- Monroe's Motivated Sequence AttentionDocument4 pagesMonroe's Motivated Sequence AttentionadzwinjNo ratings yet

- Tugas Penelitian HakimDocument7 pagesTugas Penelitian HakimSDN009 PetalonganNo ratings yet

- CBTI-MTherapistMaterials 03232020170216354Document83 pagesCBTI-MTherapistMaterials 03232020170216354tinasunxdNo ratings yet

- The Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index PsqiDocument2 pagesThe Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index PsqiUswatun Hasanah IINo ratings yet

- Outline Speech Importance of Sleep For College StudentsDocument10 pagesOutline Speech Importance of Sleep For College StudentsNur NadhirahNo ratings yet

- Outline For Informative SpeechDocument4 pagesOutline For Informative SpeechDAYANG NURHAIZA AWANG NORAWINo ratings yet

- PSQIDocument2 pagesPSQIAdrian HartantoNo ratings yet

- c2 Chapter 2 Test KeyDocument3 pagesc2 Chapter 2 Test KeyLaikaNo ratings yet

- Sleep: The secret to sleeping well and waking refreshedFrom EverandSleep: The secret to sleeping well and waking refreshedNo ratings yet

- Elc 590 WanDocument5 pagesElc 590 Wanwan aisyaNo ratings yet

- Epe Rho1 SSDocument8 pagesEpe Rho1 SStasaronezgi10No ratings yet

- Sleep, Recovery, and Human Performance: A Comprehensive Strategy For Long-Term Athlete DevelopmentDocument20 pagesSleep, Recovery, and Human Performance: A Comprehensive Strategy For Long-Term Athlete DevelopmentSpeed Skating Canada - Patinage de vitesse Canada100% (1)

- Overcoming Insomnia Session 3Document13 pagesOvercoming Insomnia Session 3KcNo ratings yet

- EngDocument10 pagesEngapi-558658721No ratings yet

- Eapp Group 1 (Thesis Evidence The Power of Sleep)Document20 pagesEapp Group 1 (Thesis Evidence The Power of Sleep)reneee ruuzNo ratings yet

- PsyDocument3 pagesPsyvelichkinaanzelikaNo ratings yet

- Pre-Intermediate, Chapter 1 Test: Select Readings, Second EditionDocument2 pagesPre-Intermediate, Chapter 1 Test: Select Readings, Second Editionreihaneh azimi100% (1)

- Sleep Study InterpretationDocument4 pagesSleep Study InterpretationgreenNo ratings yet

- Research Paper On Sleep StagesDocument7 pagesResearch Paper On Sleep Stagesnbaamubnd100% (1)

- 21 Tips For Beating Fatigue And Improving Your Health, Happiness And SafetyFrom Everand21 Tips For Beating Fatigue And Improving Your Health, Happiness And SafetyNo ratings yet

- Article 1 - Better SleepDocument29 pagesArticle 1 - Better Sleepnochu skyNo ratings yet

- Paragraf CalismalariDocument100 pagesParagraf CalismalariUfukŞahinNo ratings yet

- Sleep Cycle Research PaperDocument7 pagesSleep Cycle Research Paperaflbtlzaw100% (1)

- Cognitivebehavioral Therapyforsleep Disorders: Kimberly A. Babson,, Matthew T. Feldner,, Christal L. BadourDocument12 pagesCognitivebehavioral Therapyforsleep Disorders: Kimberly A. Babson,, Matthew T. Feldner,, Christal L. BadourJulian PintosNo ratings yet

- PSQIDocument2 pagesPSQIJean_Grey420No ratings yet

- Sleep Disorders in The EderlyDocument12 pagesSleep Disorders in The EderlyManuel Alejandro Pinzon OlmosNo ratings yet

- Persuasive Speech Portfolio Elc590Document6 pagesPersuasive Speech Portfolio Elc590Nur AqillahNo ratings yet

- Why Do We Need Sleep Research PaperDocument8 pagesWhy Do We Need Sleep Research Paperczozyxakf100% (1)

- James Clear - The Science of Sleep - A Brief Guide On How To Sleep Better Every NightDocument17 pagesJames Clear - The Science of Sleep - A Brief Guide On How To Sleep Better Every NightDavid Delpino100% (1)

- Review of Safety and Ef Ficacy of Sleep Medicines in Older AdultsDocument33 pagesReview of Safety and Ef Ficacy of Sleep Medicines in Older AdultsAlberto JaramilloNo ratings yet

- Rolul Somnului in Nutritie PDFDocument18 pagesRolul Somnului in Nutritie PDFCiprian MandrutiuNo ratings yet

- Persuasive Speech OutlineDocument5 pagesPersuasive Speech OutlineSITI KHADIJAH KHAIRUL ANUARNo ratings yet

- Medical Surgical Nursing in Canada 4th Edition Lewis Test BankDocument4 pagesMedical Surgical Nursing in Canada 4th Edition Lewis Test Bankborncoon.20wtw100% (26)

- Ielts General Reading Practice Test 3 8ade6cef3eDocument3 pagesIelts General Reading Practice Test 3 8ade6cef3eisratpatel7119No ratings yet

- American Thoracic Society Documents: An of Ficial American Thoracic Society Statement: The Importance of Healthy SleepDocument9 pagesAmerican Thoracic Society Documents: An of Ficial American Thoracic Society Statement: The Importance of Healthy Sleepguidance mtisiNo ratings yet

- Altered Sleeping PatternDocument4 pagesAltered Sleeping PatternIan Kenneth Da SilvaNo ratings yet

- Session 1Document15 pagesSession 1Feona82No ratings yet

- RasizolomegefulogewalurDocument2 pagesRasizolomegefulogewaluryusupovayubxon42No ratings yet

- Benefits of SleepDocument64 pagesBenefits of Sleepkalikiri616No ratings yet

- 02 RestDocument18 pages02 RestDiaconu DanielNo ratings yet

- Metabolism During Sleep: How Does LED and OLED Light Affect It?Document7 pagesMetabolism During Sleep: How Does LED and OLED Light Affect It?Bhushan Subhash GhotkarNo ratings yet

- Why Do We Sleep Term PaperDocument5 pagesWhy Do We Sleep Term Paperbeemwvrfg100% (1)

- Medical-Surgical Nursing Assessment and Management of Clinical Problems 9e Chapter 8Document4 pagesMedical-Surgical Nursing Assessment and Management of Clinical Problems 9e Chapter 8sarasjunkNo ratings yet

- Sleep DisordersDocument9 pagesSleep DisordersCharmaine LowNo ratings yet

- Review ArticleDocument19 pagesReview ArticlePriyanshi PrajapatiNo ratings yet

- Rest and Sleep Study Guide AnswersDocument7 pagesRest and Sleep Study Guide AnswersvickisscribdNo ratings yet

- PIIS2352721823001663Document20 pagesPIIS2352721823001663Mateus RikerNo ratings yet

- FAQ Sleep LearningDocument33 pagesFAQ Sleep Learningmy_Scribd_pseudoNo ratings yet

- Soal Bahas Main IdeaDocument4 pagesSoal Bahas Main IdeaWulanAsriningrumNo ratings yet

- 07Document1 page07fernanda1rondelliNo ratings yet

- 09Document1 page09fernanda1rondelliNo ratings yet

- 10Document1 page10fernanda1rondelli100% (1)

- 13Document1 page13fernanda1rondelliNo ratings yet

- 22Document1 page22fernanda1rondelli0% (1)

- Writing 1Document2 pagesWriting 1fernanda1rondelli100% (1)

- 21Document1 page21fernanda1rondelliNo ratings yet

- Oet Tips of All ModulesDocument7 pagesOet Tips of All Modulesfernanda1rondelliNo ratings yet

- Writing OETDocument4 pagesWriting OETfernanda1rondelliNo ratings yet

- OET - Writing - Parallel - SentencesDocument3 pagesOET - Writing - Parallel - Sentencesfernanda1rondelli100% (1)

- Occupational English Test - Acute Appendicitis - NursingDocument1 pageOccupational English Test - Acute Appendicitis - Nursingfernanda1rondelli0% (2)

- Nurse - PatientMs Pauline HendersonDocument2 pagesNurse - PatientMs Pauline Hendersonfernanda1rondelli50% (2)

- Nurse-Olivia Merriman DeconditioningDocument2 pagesNurse-Olivia Merriman Deconditioningfernanda1rondelli0% (2)

- OET Writing 7Document3 pagesOET Writing 7fernanda1rondelli100% (1)

- Rules For Writing (Vvi)Document22 pagesRules For Writing (Vvi)fernanda1rondelliNo ratings yet

- Nursing Original Cerebrovascular AccidentDocument1 pageNursing Original Cerebrovascular Accidentfernanda1rondelli75% (4)

- OET Writing PreetDocument1 pageOET Writing Preetfernanda1rondelliNo ratings yet

- Sample Model Letter 4Document1 pageSample Model Letter 4fernanda1rondelli88% (8)

- Sample Model Letter 3Document1 pageSample Model Letter 3fernanda1rondelli83% (6)

- Sample Model Letter 5Document1 pageSample Model Letter 5fernanda1rondelliNo ratings yet

- Sample Writing Task 5Document1 pageSample Writing Task 5fernanda1rondelli100% (2)

- Task - 14 - Part B.going Blind PassageDocument9 pagesTask - 14 - Part B.going Blind Passagefernanda1rondelli100% (1)

- Sample Model Letter 2Document1 pageSample Model Letter 2fernanda1rondelli92% (12)

- Reading Part A SIDSDocument6 pagesReading Part A SIDSfernanda1rondelliNo ratings yet

- Task 9 Part B.latin AmericaDocument9 pagesTask 9 Part B.latin Americafernanda1rondelliNo ratings yet

- Reading Part A Hair LossDocument6 pagesReading Part A Hair Lossfernanda1rondelliNo ratings yet

- How To Study - WikiHowDocument6 pagesHow To Study - WikiHowCristian ȘtefanNo ratings yet

- Ndlec SleepHygieneandRecoveryStrategiesinEliteSoccerPlayers SportsMed2015Document16 pagesNdlec SleepHygieneandRecoveryStrategiesinEliteSoccerPlayers SportsMed2015JULIÁN PRIETONo ratings yet

- Another CaseDocument1 pageAnother Caseapi-400032207No ratings yet

- Life PreDocument12 pagesLife PreKarlita-BNo ratings yet

- OUMH1203 ContohDocument13 pagesOUMH1203 ContohEllaNo ratings yet

- Fatigue PowerPoint Presentation Compatibility ModeDocument96 pagesFatigue PowerPoint Presentation Compatibility ModePouryaNo ratings yet

- Unit 1 LifestyleDocument7 pagesUnit 1 LifestyleAiman HakimNo ratings yet

- Complete The Table Below Write ONE WORD ONLY For Each AnswerDocument7 pagesComplete The Table Below Write ONE WORD ONLY For Each AnswerMai LêNo ratings yet

- Ecology of Human SleepDocument49 pagesEcology of Human SleepsamkarpNo ratings yet

- The Effects of Sleep Deprivation On College StudentsDocument45 pagesThe Effects of Sleep Deprivation On College StudentsReignlyNo ratings yet

- HAI PHONG Đề thi DHBB Lần X Năm 2016 2017 Anh 11 ĐỀ ĐỀ XUẤT.Tổng hợp.02Document18 pagesHAI PHONG Đề thi DHBB Lần X Năm 2016 2017 Anh 11 ĐỀ ĐỀ XUẤT.Tổng hợp.02Tran Phan Bao NgocNo ratings yet

- A Siesta For JackilouDocument5 pagesA Siesta For JackilouGilbert Base Jr.No ratings yet

- B2+ Review Test 1 HigherDocument6 pagesB2+ Review Test 1 HigherNikoglayNo ratings yet

- Tucker Et Al. - 2006 - A Daytime Nap Containing Solely non-REM Sleep EnhaDocument7 pagesTucker Et Al. - 2006 - A Daytime Nap Containing Solely non-REM Sleep Enhaelminister666No ratings yet

- Serif Newsletter 2Document3 pagesSerif Newsletter 2api-451663411No ratings yet

- Ielts General Reading Practice Test 3 8ade6cef3eDocument3 pagesIelts General Reading Practice Test 3 8ade6cef3eisratpatel7119No ratings yet

- Sleep, Recovery, and Human Performance: A Comprehensive Strategy For Long-Term Athlete DevelopmentDocument20 pagesSleep, Recovery, and Human Performance: A Comprehensive Strategy For Long-Term Athlete DevelopmentSpeed Skating Canada - Patinage de vitesse Canada100% (1)

- Life 2e Bre Pre-Inter SB U01 Part A, B, CDocument44 pagesLife 2e Bre Pre-Inter SB U01 Part A, B, CTrang HoangNo ratings yet

- Sleeping PodsDocument1 pageSleeping PodsSamrin ZeyaNo ratings yet

- Sleep Phylogeny & OntogenyDocument7 pagesSleep Phylogeny & OntogenyVivian PNo ratings yet

- Materi Speaking For Kids (DOM 2)Document51 pagesMateri Speaking For Kids (DOM 2)farmasi igdNo ratings yet

- Benefits of Power Napping 1. Make You HappierDocument3 pagesBenefits of Power Napping 1. Make You HappierTâm HoàngNo ratings yet