Professional Documents

Culture Documents

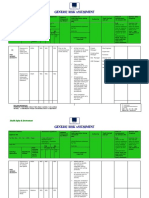

Venezuela. Campesinos

Venezuela. Campesinos

Uploaded by

mjohannakCopyright:

Available Formats

You might also like

- Vogue USA - January 2021Document94 pagesVogue USA - January 2021Andreea Dana100% (6)

- The Neoliberal Turn in Sri Lanka: Global Financial Flows and Construction After 1977Document6 pagesThe Neoliberal Turn in Sri Lanka: Global Financial Flows and Construction After 1977Social Scientists' AssociationNo ratings yet

- Question Paper For GD&T TrainingDocument5 pagesQuestion Paper For GD&T Trainingvivekanand bhartiNo ratings yet

- EtsyBusinessModel PDFDocument1 pageEtsyBusinessModel PDFChâu TheSheep100% (1)

- Farmers ProfileDocument4 pagesFarmers ProfilemeepadsNo ratings yet

- Venezuela Building A Socialist CommunalDocument19 pagesVenezuela Building A Socialist Communalbiru AngkasaNo ratings yet

- Clark-2017-Ecuador, Journal of Agrarian ChangeDocument17 pagesClark-2017-Ecuador, Journal of Agrarian ChangePatrick ClarkNo ratings yet

- 16-12-12 The Achievements of Hugo ChávezDocument6 pages16-12-12 The Achievements of Hugo ChávezWilliam J GreenbergNo ratings yet

- Fact SheetDocument3 pagesFact Sheetapi-327726527No ratings yet

- Murugani Venezuela 2021Document12 pagesMurugani Venezuela 2021Alex JamesNo ratings yet

- Poverty in The PhilippinesDocument7 pagesPoverty in The PhilippinesTon Nd QtanneNo ratings yet

- Module 3 ExamDocument4 pagesModule 3 ExamWol WapNo ratings yet

- Venezuela and The Struggle1Document14 pagesVenezuela and The Struggle1Glenda Guzman AriasNo ratings yet

- Development Is A MythDocument6 pagesDevelopment Is A MythAmir Asraf YunusNo ratings yet

- Notes On Poverty in The Philippines: Asian Development BankDocument6 pagesNotes On Poverty in The Philippines: Asian Development BankStephanie HamiltonNo ratings yet

- Research Paper VenezuelaDocument5 pagesResearch Paper Venezuelafvjawjkt100% (1)

- SIBALDocument17 pagesSIBALapi-26570979No ratings yet

- Barkin Pike Tty RRP eDocument7 pagesBarkin Pike Tty RRP eGerda WarnholtzNo ratings yet

- 2014 Eakin - Et - Al-2014-Agrarian Winners of Neoliberal Reform, The Maize Boom of Sinaloa, MexicoDocument26 pages2014 Eakin - Et - Al-2014-Agrarian Winners of Neoliberal Reform, The Maize Boom of Sinaloa, MexicoJose Manuel FloresNo ratings yet

- Agrarian Reform and Poverty Reduction in The Philippines: Arsenio M. Balisacan andDocument20 pagesAgrarian Reform and Poverty Reduction in The Philippines: Arsenio M. Balisacan andChante CabantogNo ratings yet

- The Welfare State and Global Health: Latin America, The Arab World and The Politics of Social ClassDocument3 pagesThe Welfare State and Global Health: Latin America, The Arab World and The Politics of Social Classjerdionmalaga1981No ratings yet

- Global DemographyDocument39 pagesGlobal DemographyNonito C. Arizaleta Jr.100% (1)

- Summative Land InequalityDocument12 pagesSummative Land InequalityChan KawaiNo ratings yet

- Effects of High Fertility On Economic Development: Emmanuel ObiDocument12 pagesEffects of High Fertility On Economic Development: Emmanuel ObiJude Daniel AquinoNo ratings yet

- Pcaaa 960Document5 pagesPcaaa 960Genesis AdcapanNo ratings yet

- TCW IM Demoraphy and Migration Pages 63 69Document7 pagesTCW IM Demoraphy and Migration Pages 63 69rhika jimenezNo ratings yet

- Problems and Prospects of Rural Development Planning in Nigeria, 1 9 6 0 - 2 0 0 6Document17 pagesProblems and Prospects of Rural Development Planning in Nigeria, 1 9 6 0 - 2 0 0 6Abdullahi AwwalNo ratings yet

- El Salvador's New Leader Enters Accords With Venezuela and Latin American LeftDocument4 pagesEl Salvador's New Leader Enters Accords With Venezuela and Latin American LeftGustavo LopezNo ratings yet

- Lesson 9 Global DemographyDocument55 pagesLesson 9 Global Demographyvalorang0444No ratings yet

- Sher Ob NotesDocument22 pagesSher Ob NotesGul Sanga AzamNo ratings yet

- Rural Poverty Literature ReviewDocument8 pagesRural Poverty Literature Reviewafmzrvaxhdzxjs100% (1)

- GAD v2 FinalDocument15 pagesGAD v2 FinalMA. IRISH ACE MAGATAONo ratings yet

- Escaping Poverty 20Document16 pagesEscaping Poverty 20ehamza654No ratings yet

- Extended Essay Chapter 2Document7 pagesExtended Essay Chapter 2Cristian JairalaNo ratings yet

- Unraveling The Unsustainablity Spiral in Subsaharan Africa: An Agent Based Modelling ApproachDocument26 pagesUnraveling The Unsustainablity Spiral in Subsaharan Africa: An Agent Based Modelling ApproachDániel TokodyNo ratings yet

- Global DemographyDocument20 pagesGlobal DemographyLuna50% (2)

- De Janvry and Lynn Ground-Source, Types and Consequences of Land Reform in Latin America (1978)Document24 pagesDe Janvry and Lynn Ground-Source, Types and Consequences of Land Reform in Latin America (1978)Historia UdeChile DosmilOchoNo ratings yet

- Food Sovereignty: Reconnecting Food, Nature and CommunityDocument13 pagesFood Sovereignty: Reconnecting Food, Nature and CommunityFernwood Publishing50% (2)

- Case Study Series Dark Side of Distribution Policies: Venezuelan Hyperinflation CrisisDocument13 pagesCase Study Series Dark Side of Distribution Policies: Venezuelan Hyperinflation CrisisVaibhav RajoreNo ratings yet

- Outgrowing The Earth - Lester Brown PDFDocument2 pagesOutgrowing The Earth - Lester Brown PDFErcilia DelancerNo ratings yet

- Making Growth Inclusive: Some Lessons From Countries and The LiteratureDocument43 pagesMaking Growth Inclusive: Some Lessons From Countries and The LiteratureOxfamNo ratings yet

- Making Growth Inclusive: Some Lessons From Countries and The LiteratureDocument43 pagesMaking Growth Inclusive: Some Lessons From Countries and The LiteratureOxfamNo ratings yet

- Making Growth Inclusive: Some Lessons From Countries and The LiteratureDocument43 pagesMaking Growth Inclusive: Some Lessons From Countries and The LiteratureOxfamNo ratings yet

- Making Growth Inclusive: Some Lessons From Countries and The LiteratureDocument43 pagesMaking Growth Inclusive: Some Lessons From Countries and The LiteratureOxfamNo ratings yet

- Making Growth Inclusive: Some Lessons From Countries and The LiteratureDocument43 pagesMaking Growth Inclusive: Some Lessons From Countries and The LiteratureOxfamNo ratings yet

- Making Growth Inclusive: Some Lessons From Countries and The LiteratureDocument43 pagesMaking Growth Inclusive: Some Lessons From Countries and The LiteratureOxfamNo ratings yet

- Making Growth Inclusive: Some Lessons From Countries and The LiteratureDocument43 pagesMaking Growth Inclusive: Some Lessons From Countries and The LiteratureOxfamNo ratings yet

- Making Growth Inclusive: Some Lessons From Countries and The LiteratureDocument43 pagesMaking Growth Inclusive: Some Lessons From Countries and The LiteratureOxfamNo ratings yet

- Making Growth Inclusive: Some Lessons From Countries and The LiteratureDocument43 pagesMaking Growth Inclusive: Some Lessons From Countries and The LiteratureOxfamNo ratings yet

- Making Growth Inclusive: Some Lessons From Countries and The LiteratureDocument43 pagesMaking Growth Inclusive: Some Lessons From Countries and The LiteratureOxfamNo ratings yet

- Making Growth Inclusive: Some Lessons From Countries and The LiteratureDocument43 pagesMaking Growth Inclusive: Some Lessons From Countries and The LiteratureOxfamNo ratings yet

- Making Growth Inclusive: Some Lessons From Countries and The LiteratureDocument43 pagesMaking Growth Inclusive: Some Lessons From Countries and The LiteratureOxfamNo ratings yet

- Making Growth Inclusive: Some Lessons From Countries and The LiteratureDocument43 pagesMaking Growth Inclusive: Some Lessons From Countries and The LiteratureOxfamNo ratings yet

- Making Growth Inclusive: Some Lessons From Countries and The LiteratureDocument43 pagesMaking Growth Inclusive: Some Lessons From Countries and The LiteratureOxfamNo ratings yet

- Making Growth Inclusive: Some Lessons From Countries and The LiteratureDocument43 pagesMaking Growth Inclusive: Some Lessons From Countries and The LiteratureOxfamNo ratings yet

- Making Growth Inclusive: Some Lessons From Countries and The LiteratureDocument43 pagesMaking Growth Inclusive: Some Lessons From Countries and The LiteratureOxfamNo ratings yet

- Making Growth Inclusive: Some Lessons From Countries and The LiteratureDocument43 pagesMaking Growth Inclusive: Some Lessons From Countries and The LiteratureOxfamNo ratings yet

- Agro-Rural Development As A Source of Socio-Economic Change With Special Reference To IranDocument8 pagesAgro-Rural Development As A Source of Socio-Economic Change With Special Reference To IranAmin MojiriNo ratings yet

- LATERRA Et Al. - Austerity Programs in Argentica - AGS 10 (1) 2021Document29 pagesLATERRA Et Al. - Austerity Programs in Argentica - AGS 10 (1) 2021Agostina CostantinoNo ratings yet

- In The Shadow of The Market - Ontario's Social Economy in The Age of Neo-Liberalism (2002)Document36 pagesIn The Shadow of The Market - Ontario's Social Economy in The Age of Neo-Liberalism (2002)theselongwarsNo ratings yet

- Torri. Multicultural Social Policy and Communityparticipation in Health - New Opportunities Andchallenges For Indigenous People PDFDocument23 pagesTorri. Multicultural Social Policy and Communityparticipation in Health - New Opportunities Andchallenges For Indigenous People PDFanon_731469955No ratings yet

- 3 Cuba Ijhs-2005-De VosDocument19 pages3 Cuba Ijhs-2005-De Vospepinillod13No ratings yet

- Lesson 9 - Global DemographyDocument34 pagesLesson 9 - Global Demographybarreyrochristine.iskolarNo ratings yet

- Gale Researcher Guide for: Poverty Policies in the United StatesFrom EverandGale Researcher Guide for: Poverty Policies in the United StatesNo ratings yet

- Comparison Chart: (Conduction, Convection, Radiation)Document5 pagesComparison Chart: (Conduction, Convection, Radiation)RandyNo ratings yet

- Portfolio Assessment RubricDocument5 pagesPortfolio Assessment RubricMoises RodriguezNo ratings yet

- The VerdictDocument4 pagesThe Verdicthttps://twitter.com/wagelabourNo ratings yet

- Business English Certificate Preliminary Test of ListeningDocument8 pagesBusiness English Certificate Preliminary Test of ListeningBarun BeheraNo ratings yet

- Cigre StatcomDocument170 pagesCigre StatcomМиша ГабриеловNo ratings yet

- TST-Swan Martin PDFDocument15 pagesTST-Swan Martin PDFRini SartiniNo ratings yet

- Cold in Place RecyclingDocument10 pagesCold in Place RecyclingRajesh ChoudharyNo ratings yet

- 2 - Picture Supported Writing Prompts - FEELINGS For SpEd or Autism UnitsDocument51 pages2 - Picture Supported Writing Prompts - FEELINGS For SpEd or Autism UnitsWake UpNo ratings yet

- (Download PDF) On The Trail of Capital Flight From Africa The Takers and The Enablers Leonce Ndikumana Editor Full Chapter PDFDocument69 pages(Download PDF) On The Trail of Capital Flight From Africa The Takers and The Enablers Leonce Ndikumana Editor Full Chapter PDFhadlerktat100% (5)

- Gent's ParlourDocument33 pagesGent's ParlourNiloy Abu NaserNo ratings yet

- Tata Sky ALC Channel ListDocument13 pagesTata Sky ALC Channel ListIndianMascot33% (3)

- E Commerce in TourismDocument30 pagesE Commerce in TourismDHEERAJ BOTHRANo ratings yet

- KyAnh A320F Structure GeneralDocument101 pagesKyAnh A320F Structure Generalnqarmy100% (1)

- Group Activity Questions Buss. MathDocument1 pageGroup Activity Questions Buss. MathIreneRoseMotas100% (1)

- Design Change Connexion - ECN - RegisterDocument3 pagesDesign Change Connexion - ECN - RegisterMbalekelwa MpembeNo ratings yet

- KSB Surge PublicationDocument34 pagesKSB Surge PublicationDiego AguirreNo ratings yet

- FGP WPMP BrochureDocument12 pagesFGP WPMP BrochureArbiMuratajNo ratings yet

- Republic V FNCBDocument6 pagesRepublic V FNCBMp Cas100% (1)

- Risk Assessment Hot WorkDocument5 pagesRisk Assessment Hot WorkRanjit DasNo ratings yet

- Hindi Basic HD 296.77 472.77 SD Channels & Services HD Channels & Services Total Channels & ServicesDocument2 pagesHindi Basic HD 296.77 472.77 SD Channels & Services HD Channels & Services Total Channels & ServicesRitesh JhaNo ratings yet

- Carnaval Owners ManualDocument17 pagesCarnaval Owners Manualmike_net8903No ratings yet

- CORESTIC - 8 (Red) : The ProductDocument1 pageCORESTIC - 8 (Red) : The ProductVikrant KhavateNo ratings yet

- Micro Project Report (English)Document13 pagesMicro Project Report (English)Chaitali KumbharNo ratings yet

- BU3-ENV-SOP-010 (01) Waste ManagementDocument25 pagesBU3-ENV-SOP-010 (01) Waste ManagementJoel Osteen RondonuwuNo ratings yet

- t1l2 Vol.5.3 Lucrari de Drum (Det)Document176 pagest1l2 Vol.5.3 Lucrari de Drum (Det)RaduIS91No ratings yet

- Sample Appoitment LetterDocument4 pagesSample Appoitment LetterSourabh KukarNo ratings yet

Venezuela. Campesinos

Venezuela. Campesinos

Uploaded by

mjohannakCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Venezuela. Campesinos

Venezuela. Campesinos

Uploaded by

mjohannakCopyright:

Available Formats

Journal of Agrarian Change, Vol. 10 No. 2, April 2010, pp. 251–272.

Can the State Create Campesinos?

A Comparative Analysis of the Venezuelan

and Cuban Repeasantization Programmes

TIFFANY LINTON PAGE

I examine Venezuela’s repeasantization programme Vuelta al Campo, which

was part of a larger effort to pursue a redistributive path to development.

Through exploring this case and contrasting it with Cuba’s repeasantization

programme in the 1990s, I draw conclusions that extend our understanding

of what makes such a state-led development programme work. The state in

Venezuela played an indispensable role by providing many forms of necessary

support for launching such an ambitious project – e.g. financial resources and

legal title to the land – but failed to truly increase participation in decision-

making. Increased participation by those affected by the Vuelta al Campo

programme could have prevented or minimized some of the problems that arose.

Moreover, the programme had the unintended consequence of demobilizing

participants who had previously been politically engaged. This demobilization

undermined the larger national social project – building ‘21st-century

socialism’._JOAC 251..272

Keywords: repeasantization, development, state, socialism, Venezuela

INTRODUCTION

In Latin America, the rural population as a percentage of the total population has

been decreasing (CEPAL 2001, 41–6). Urban areas in Latin America have been

unable to economically absorb all the migrants from rural areas and, consequently,

shantytowns have grown around the city core. This is the case in Venezuela where,

as of 2007, 93 per cent of the population lived in urban areas (World Bank 2008,

1). Countries have become more dependent on food imports as the size of the rural

population has decreased. Many countries in the Global South increasingly find

themselves confronting issues such as the inaccessibility of affordable food, high

levels of unemployment and economic instability resulting in part from limited

economic diversification.The agricultural sector in Venezuela constitutes only 5 per

Tiffany Linton Page, Department of Sociology, University of California Berkeley, 410 Barrows Hall,

Berkeley, CA 94720-1980, USA. e-mail: paget@berkeley.edu

I would like to acknowledge the financial assistance I received from the Andrew W. Mellon

Fellowship in Latin American Sociology, a research expense grant from the Department of Sociology

at University of California, Berkeley and the Tinker Grant from the Center for Latin American

Studies at U.C. Berkeley. I would like to thank Laura Enríquez and the anonymous reviewers of the

Journal of Agrarian Change for their feedback on earlier drafts of this paper. I also want to thank the

farmers and government employees in Anzoateguí who provided me with support and gave of their

time and knowledge to participate in this study.

© 2010 The Author – Journal compilation © 2010 Blackwell Publishing Ltd

252 Tiffany Linton Page

cent of GDP and the country imports 60 per cent of its food (IFAD 2006, 1).With

fluctuating food prices on the international market, the ability to import sufficient

food to feed the population can, at times, be compromised. This is particularly true

when a country is dependent on a single export commodity, for if the price of that

commodity falls, they will lack the necessary foreign exchange to import the food

they need.

In order to meet domestic demand for food, governments have sometimes

increased the number of people working in agriculture through repeasantization

programmes. These types of programmes have often been carried out by socialist

governments and in times of economic crisis when access to imported food was

limited. Programmes to create small farmers confront a number of challenges.

Urbanization has been considered part of modernization and rural areas are often

regarded as backward. Repeasantization requires a shift in people’s thinking and the

way society values agricultural work. It means both a lifestyle change from the

fast-paced activity of dense urban areas to the more tranquil rural areas, and leaving

behind the community you are part of to build a community from scratch.

Participants must quickly acquire the knowledge that farmers acquire over a lifetime.

In 2001, the Chávez government in Venezuela began promoting a rural devel-

opment plan to expand the agricultural sector, with the objectives of diversifying

the economy, generating employment, redistributing the population geographically

and achieving food self-sufficiency. One of the programmes developed to further

these goals was Vuelta al Campo (VAC), or a Return to the Countryside. It was a

voluntary programme in which urban dwellers could relocate to rural areas with

state support, to establish farming operations. During the period from 2002 to 2005,

57 farms were created across 20 states. Fourteen of these farms were part of the VAC

programme and nine states were home to a VAC farm (INTI 2006, 1–2).While VAC

was not the most important project within the larger agricultural programme (as

measured by the number of farms created through it relative to other programmes1),

the concept VAC represents – a return to the countryside – is fundamental to the

new vision for the agricultural sector (Kott and Felson 2009, 3).

The repeasantization plan in Venezuela is part of a larger effort to expand the role

of the state in the national development project and to pursue a redistributive path

to development. It rejects many of the tenets of the neoliberal model, which

promotes a limited role for the state and a ‘trickle down’ path to redistribution.

Examination of this alternative model seems fruitful considering the neoliberal

model has proven to increase poverty and inequality (Vilas 1996, 1; Wilpert 2007,

107). At the same time, there is research to suggest that large-scale, centrally planned

projects tend to fail (Scott 1998, 4–6; Ferguson 1994, 254–76). What roles can the

state play to facilitate a long-term demographic shift of the population to rural

areas? The Venezuelan case speaks to the possibilities and limitations of an active

1

More of the newly created farms are occupied by cooperatives formed through Misión Vuelvan

Caras, a job-training programme, and many of these cooperatives have some members who are new

to farming. These cooperatives and farms, however, differ in a number of ways from the VAC farms

and consequently are not included in the analysis presented here. The government institution

responsible for these farms differs from the VAC farms; they have access to different pots of money;

the cooperatives generally include both farmers and people new to farming; and these cooperatives

usually establish farms in the state where participants were already living.

© 2010 The Author – Journal compilation © 2010 Blackwell Publishing Ltd

Can the State Create Campesinos? 253

state in pursuit of a redistributive path to development in today’s highly integrated

global economy. The government’s control of the country’s oil revenue provided it

with the financial means to play an active role in development and its socialist-

inspired ideology meant that the government saw an active role for the state as key.

By exploring this case, we can glean some valuable lessons that extend our under-

standing of the processes at work in state-led development programmes. The

empirical evidence I present is from three months of fieldwork in the state of

Anzoateguí, including observations and material from in-depth qualitative

interviews.2

THE ROLE OF THE STATE IN DEVELOPMENT

After nearly three decades of neoliberalism dominating mainstream development

thinking, people, particularly in the Global South, are questioning this model and

trying alternative development models. This has occurred in Venezuela where the

two political parties that alternated power for nearly four decades (1958–1994) lost

legitimacy. Poverty and inequality increased during the years of structural adjust-

ment;3 social, economic and political exclusion came to be seen as permanent

features of Venezuelan society for the poor majority.

Hugo Chávez emerged in the 1990s and gave people hope that he could bring

real change to the political system. When he was elected President in 1998, state

policy took a sharp turn, ushering in a redistributive path to development with the

idea of expanding popular participation. The state initiated a number of redistribu-

tive measures, including the passage of the Ley de Tierras y Desarrollo Agrario (The

Law of Land and Agrarian Development) in 2001. This law provided the legal

framework to carry out land redistribution.

Venezuela was characterized by a highly unequal distribution of land,4 agricul-

tural production was low, and un- and under-employment was high. In promoting

the transformation of the agricultural sector, the Chávez government sought to

expand domestic food production, create jobs, raise living standards, and redistribute

resources to small farmers or people interested in becoming farmers. In the first

years of agrarian reform, state-owned land was redistributed. It was not until 2005

that the state began expropriating privately owned land. Around this time, Chávez

announced that Venezuela was going to build ‘21st-century socialism’. Although this

came about four years after the Land Law was first introduced, the government had

already been promoting redistribution, collective property rights, collective forms of

production, and an emphasis on production to meet basic needs.When the national

development project became explicitly ‘socialist’, the government continued to

2

This research was carried out at the end of 2007 and was part of a larger study on the agrarian

reform.

3

The percentage of people living in poverty increased from 32.2 per cent in 1991 to 48.5 per cent

in 2000, while the rate of extreme poverty increased from 11.8 per cent to 23.5 per cent (World

Bank 2006, 1). The richest 20 per cent of Venezuelans earned 53 per cent of total income, while

the poorest 20 per cent earned 3 per cent of the country’s total income (World Bank 2004, 1).

4

Prior to the land reform that began under Chávez, 75.2 per cent of landholders owned farms of

less than 20 hectares, which constituted 5.7 per cent of total land, while 1 per cent of landholders

owned farms of 1,000 hectares or more, which constituted 46.5 per cent of the land (Delahaye

2004, 17).

© 2010 The Author – Journal compilation © 2010 Blackwell Publishing Ltd

254 Tiffany Linton Page

socialize agriculture, primarily through efforts to encourage a shift in thinking from

individualism to a collective mentality (INTI 2007, 1–2). A socialist development

path affords a significant role to the state.5

A number of scholars have argued that the state has an important role to play in

development (Evans 1997, 82–7; Ó Riain 2000, 20–1; Weiss 1997, 3–4). States can

play a useful role in planning, overseeing and/or participating in production and

distribution to make sure social needs are met, public goods provided and balanced

economic growth occurs. However, states also can, and often do, act in ways that

reproduce inequality. Social groups with more economic power tend to wield more

political power. Socialist projects aim to address this tendency by redistributing

political and economic power. In transitions to socialism, although the idea is for

organized popular sectors to play a key role in defining and implementing the new

political vision, the state can end up dominating the process. One rationale that

governments use is that popular sectors are unorganized and tend to lack many of

the necessary skills for constructing the new society (Fagen 1986, 260). Some

governments may then pursue, what Scott (1998, 4) calls, ‘high modernist’ devel-

opment schemes.

Scott (1998, 4) describes ‘high modernism’ as an ideology that optimistically

believes a government can comprehensively plan settlement patterns and produc-

tion. When such grand plans for development did not work, Scott argues that

governments shifted to ‘miniaturization: the creation of a more easily controlled

micro-order in model cities, model villages, and model farms’ (1998, 4). High

modernism, Scott posits, was not associated with any particular political bent, but

rather with ‘those who wanted to use state power to bring about huge, utopian

changes in people’s work habits, living patterns, moral conduct, and worldview’

(1998, 5). Scott (1998, 223–61) examines a number of high modernist schemes,

including compulsory villagization of people living in rural areas in Tanzania in the

late 1960s and into the 1970s. He argues that the movement of people into planned

settlements often results in the destruction of prior communities. The new com-

munities must start from scratch at building cohesion and the ability to act

collectively.

Instead of the unrepeatable variety of settlements closely adjusted to local

ecology and subsistence routines and instead of the constantly changing local

response to shifts in demography, climate and markets, the state would have

created thin, generic villages that were uniform in everything from political

structure and social stratification to cropping techniques. The number of

variables at play would be minimized. In their perfect legibility and sameness,

these villages would be ideal, substitutable bricks in an edifice of state plan-

ning. Whether they would function was another matter. (Scott 1998, 255)

5

Socialism involves production and distribution to meet basic needs, ending privileged access to

goods and increasing popular participation in decision-making (Fagen et al. 1986, 10). Socialist

development paths tend to have an active role for the state.The state, generally, redistributes land and

other resources, provides free or low-cost social services and encourages its supporters – mainly the

relatively unorganized poor majority – to get organized. The state may promote the formation of

production cooperatives and establish new institutional structures within the state to facilitate greater

popular participation.

© 2010 The Author – Journal compilation © 2010 Blackwell Publishing Ltd

Can the State Create Campesinos? 255

Scott (1998, 345–6) explains that planned communities tend to fail because the state

standardizes citizens, or sees them in the abstract without any context. He suggests

that this is not a mistake, but rather a necessary simplification in large-scale

planning. He argues, ‘What is perhaps most striking about high-modernist schemes,

despite their quite genuine egalitarian and often socialist impulses, is how little

confidence they repose in the skills, intelligence, and experience of ordinary people’

(Scott 1998, 346). This is a top-down approach to development, in which the state

fails to recognize the attributes and initiative of the intended beneficiaries of their

projects.

Ferguson (1994, 255–6) notes that although centrally planned development

projects may fail to achieve their objectives in the long term, they tend to have

unintended consequences, such as the expansion of state power and the depoliti-

cization of the populace. Every ‘problem’ identified can become a point of entry for

new state programmes.The state, he argues, tends to turn development and poverty

into a technical problem, thereby depoliticizing these issues.

The Venezuelan government under Chávez took a dominant role in the

national development project. VAC, as well as other programmes in the agricul-

tural sector, aimed to create model farms, not unlike what Scott describes. The

government’s vision involved changing people’s work habits – encouraging

people to work harder and collectively – and changing their living patterns –

creating new communities in the countryside. Changing moral conduct and

worldview were central in the government’s rhetoric as it encouraged citizens to

shift their thinking from a capitalist mentality to a socialist mentality. While VAC

was a voluntary programme, in contrast to the Tanzanian villagization project,

participants also ended up leaving behind their communities to move to an unfa-

miliar place to build a new life and community. Moreover, the Venezuelan gov-

ernment had a relatively standardized plan of what these farms and ultimately

villages would look like, regardless of the locale in which they were situated or

the individuals involved. VAC participants arrived on the farms with no local

know-how because they were coming with little-to-no agricultural knowledge

and were not familiar with the region of the country where they had moved.

The government’s plan was to play a formative role in shaping the thinking of

participants as it trained them in agro-ecological farming and a collective pro-

duction model.

Similar to what Ferguson (1994) describes for Lesotho, the expansion of state

power has occurred in the countryside in Venezuela. New roads were built into

areas of the country that were previously rarely visited due to the difficulties of

navigating the dirt roads. Employees of the government visited existing com-

munities in the areas around the new farms and collected information on the

people who lived there, opening the way for the entrance of other government

programmes into these communities. Yet in contrast to the depoliticization of

poverty and development described by Ferguson (1994), the Venezuelan govern-

ment politicized these issues. It views the mobilization of its supporters as key

to the process of realizing the larger, social project of building ‘21st-century

socialism’. However, the task of establishing new farms in relatively isolated parts

of the country effectively demobilized the formerly highly mobilized VAC

participants.

© 2010 The Author – Journal compilation © 2010 Blackwell Publishing Ltd

256 Tiffany Linton Page

REPEASANTIZATION

Repeasantization is a phenomenon that, in most cases, is state-led and part of a

larger project to reconfigure society and the economy. In the context of a transition

to socialism, there are two fundamental elements in repeasantization programmes:

(a) training people in agricultural production and (b) shifting to a socialist produc-

tion model. The first part involves building the skills and knowledge of the people

who will be, for the most part, new to agriculture. Repeasantization at the begin-

ning of a transition to socialism also involves shifting participant’s thinking from

being a wageworker to working and managing farm operations as part of a

collective. Both require on-going training. Moreover, the government must build

the infrastructure that makes settlement in rural areas attractive. Even if people were

previously living in shantytowns, they are giving up certain amenities by moving to

rural areas. They must feel that their standard of living and quality of life will

improve. Although different in important respects from the Venezuelan case, the

relatively successful repeasantization programme in Cuba in the 1990s illuminates

some of the factors that determine degree of success.

Cuba underwent two earlier agrarian reforms before the agrarian reform of

the 1990s, the first in 1959 and the second in 1963. These first two agrarian

reforms ‘inserted agricultural production in the socialist development project of

Cuba’ (Pérez et al. 1999, 144). In the 1960s, the government expropriated the

farms of large landowners and turned them into state farms. In addition to the

state sector, there existed a private sector composed of smaller farms, which was

composed of agrarian reform beneficiaries and historic small farmers. In 1975, the

Communist Party and the Asociación Nacional de Agricultores Pequeños

(ANAP), the organization of small farmers, decided to move in the direction of

cooperatization. Private producers were encouraged to voluntarily form a coop-

erative with other individual producers, collectivizing their land and the output

produced. The process of cooperatization was viewed as a long-term process,

based on farmers coming to see the advantages of cooperative organization. ‘One

of the principal obstacles for its implementation was rooted in the inexistence of

a cooperative culture in the country’ (Pérez et al. 1999, 146). To encourage coop-

eratization and ensure the economic viability of the cooperatives, ANAP provided

material incentives, including compensation for the value of the land turned over

to the cooperative, the right to retire, credit on preferential terms and the pos-

sibility of constructing houses (Pérez et al. 1999, 146). Cooperative production

was well established when the agrarian reform of the 1990s – of which repeas-

antization was a part – began.

In the 1990s, cooperative production was further expanded with the transfor-

mation of the state farms into Basic Units of Cooperative Production (UBPCs),

which were modelled on the cooperatives established earlier (Powell 2004, 9). The

state decentralized management to increase participation in production decision-

making and, as a result, UBPC members felt more empowered (Deere 1998, 80). In

1992, the government began allowing workers on the state farms to have a small

parcel of their own to farm for family consumption. By 1998, the number of

parceleros had increased by 80 per cent (Valdés Paz 2000, 111). ‘This increase of

parceleros, although it strengthened the forms of smallholder exploitation, permitted

© 2010 The Author – Journal compilation © 2010 Blackwell Publishing Ltd

Can the State Create Campesinos? 257

a better use of land and the reincorporation of the urban or semi-urban sector of

the workforce’ (2000, 111).

The primary reason for launching the repeasantization programme, which began

in 1990 in Cuba, was a labour shortage in the agricultural sector. This had been a

problem since the beginning of the revolution. It worsened in the 1990s with the

fall of COMECON, the Soviet-led trade bloc, when the government no longer

had easy access to fuel and other inputs needed for mechanized agriculture. The

government created both a short-term and a two-year agricultural work pro-

gramme. ‘In order to ensure that urban workers, indeed, volunteer, major invest-

ments were made throughout Havana province in new and attractive camps, which

offer[ed] quite decent accommodation’ (Deere 1998, 69). The economic hardship

during this time further encouraged individuals to move from non-agricultural

work to agricultural work.The latter had the additional benefit of providing people

with food, which they might not otherwise have had (Enríquez 2003, 208–9). The

relatively attractive nature of the agricultural sector in the context of the economic

crisis can be seen in Sáez’s (2003, 19–20) description of an agricultural cooperative

that turned away applicants for membership because the cooperative could not

incorporate all of them. During these hard economic times, small farmers were

doing relatively well economically.

Although there were efforts to increase permanent housing in the countryside,

there were shortages in building materials due to the economic crisis, which limited

the number of houses constructed. Consequently, upon completion of their two-

year contract, some people decided not to continue working in agriculture due to

the lack of permanent housing in the countryside (Deere 1998, 70). Enríquez

(forthcoming), however, found that a number of people who participated in the

temporary agricultural work programme decided to stay in agriculture. Not only

did the state create ‘the material and legal conditions for peasantization, it also

engaged in an effort to politically valorize small farming’ (Enríquez forthcoming,

222). The small farmers were viewed as key economic actors in the national

development project. ‘The urgency of the National Food Programme brought

attention to the important role of individual producers in guaranteeing the food

supply for the country’ (Pérez et al. 1999, 148).

There are a number of differences between the Venezuelan and Cuban cases.

First, they differ in terms of the timing of the repeasantization programme in

relation to the transition to socialism. Cuba had been socialist for some time

preceding the repeasantization programme, in contrast to Venezuela, which intro-

duced its repeasantization programme early on in its transition to a more redis-

tributive development model.This meant that the government had the challenge of

simultaneously training people to become farmers and encouraging a shift in

thinking to embrace a socialist-inspired model. In Venezuela, many of the people

who became involved in agriculture under the current government were not only

moving from working in urban areas, in other sectors of the economy, to working

in agriculture, but also moving from wage-work to collective production and

management via participation in cooperatives. A significant amount of training and

ongoing support was necessary to facilitate this transition to a collective produc-

tion model. Piñeiro (2007, 18) found that the development of solidarity among

cooperative members in new, non-agricultural cooperatives in Venezuela was

© 2010 The Author – Journal compilation © 2010 Blackwell Publishing Ltd

258 Tiffany Linton Page

undermined by internal conflicts that resulted mainly from inexperience in admin-

istration, and which were magnified by lack of collective supervisory mechanisms.

As Pérez et al. (1999) point out in their discussion of the Cuban case, when

cooperativization was first introduced in the 1970s it was seen as a long-term

process because a cooperative culture did not exist. By the time repeasantization was

introduced in Cuba, cooperative production was well established.

Secondly, the Venezuelan government was not resource-constrained in the way

Cuba was because the price of oil was extremely high during the first four years of

the VAC programme.6 Moreover, Venezuela was not subject to a trade embargo as

Cuba was; it did not face the possibility of widespread hunger from insufficient

access to food. There was not a pressing need to expand agricultural production

because the government had foreign exchange from high oil prices and the ability

to purchase food abroad. This affected people’s perceptions of the need for repeas-

antization and their desire to work in such an arduous profession. And, finally, the

rural population in Cuba had ‘basic access to schools, housing, and healthcare’ (Sáez

2003, 37) in contrast to the Venezuelan countryside, which was lacking basic

infrastructure. In sum, the incentives for participating in the repeasantization pro-

gramme were fewer in the Venezuelan case and the challenges more numerous.

THE VUELTA AL CAMPO PROGRAMME IN VENEZUELA7

At the end of 2007, there were five VAC farms in the state of Anzoateguí.8,9

Participants arrived on the land at different times between 2003 and 2006. The

farms were located in fairly isolated areas. Participants faced challenges both on a

social level and on a technical farming level. I present interview and ethnographic

data that explore the Catch-22 in infrastructure construction that participants and

the government found themselves in and the social and cultural shift required in

making this life change. I examine the degree of community that existed among

VAC participants prior to relocating to rural areas, the impact on participants of the

relative isolation on the new farms, the process of learning to work collectively and

starting a business, and the challenge presented by oil. On the technical side, I

examine the problems around the participant training programmes, the environ-

mental challenges, and the lack of familiarity with the local environmental

6

In 2003, the average price of crude oil was US$27 per barrel. Over the next four and a half years

the price skyrocketed, hitting US$126 in June and July of 2008. Although 2008 had, on average, the

highest price of oil yet, the price fell significantly in the second half of the year to $33 in December

(Illinois Oil and Gas Association: http://www.ioga.com/Special/crudeoil_Hist.htm).

7

I use pseudonyms for all interview subjects and farms throughout.

8

One of these farms was not technically classified as VAC, but, like the VAC, was composed of

people from urban areas, who had never farmed before. The only difference that resulted from its

non-VAC classification that I could surmise was that INTI was not in charge of managing it;

consequently, more of its funding came from other government institutions.

9

Not all states had VAC farms, as it is one of many programmes that exist in the agricultural sector.

The other state where I did extensive fieldwork (Yaracuy) did not have them, most likely because

it was an agricultural state that already had a number of people who wanted to farm. However, I

visited a VAC farm in another state (Lara) that was experiencing the same problems that the VAC

farms in Anzoateguí faced. I also interviewed a government employee who worked in the National

Land Institute’s headquarters in Caracas and he acknowledged that VAC farms throughout the

country were facing similar problems.

© 2010 The Author – Journal compilation © 2010 Blackwell Publishing Ltd

Can the State Create Campesinos? 259

conditions (such as rainfall and temperature patterns). I end with an examination of

participant responses to these challenges.

Infrastructure

The government sent participants to the land before construction of infrastructure

began. None of the farms had houses, a well, or electricity when the first participants

arrived. Three of the VAC farms did not have a school nearby for the children to

attend. As a result, many participants left their families in the cities. By the end of

2007, the government had built some infrastructure on some of the farms.The farm

that was founded first had houses, electricity, a well, a classroom, an irrigation system,

tractor and a chicken coop.All the other farms lacked houses; some already had access

to electricity; one had a well. Many more infrastructure projects were planned.

Juan and his cooperative were on a farm with minimal infrastructure and had

been there for two and a half years. I asked if they began farming right away and

he responded,

No, we didn’t begin to work the land. We were getting to know the farm

because the problem was that of machinery, that we began to buy it [the

machinery]. This took a lot of time because they brought it from Brazil and

in this we lost a lot of time. It continues to take time . . . We thought that a

truck would be bought tomorrow, that they were going to deliver it at once

in order to begin work. But it is not like that. There is a lot of competition.

They are forming a lot of fundos zamoranos [new farms]. To some they [the

vehicles] arrive, to others no.You need to wait until they send it to you from

Brazil. In order to get one of these trucks that they give you, you have to wait

three or four months. (Personal interview, 24 November 2007)10

Participants waited for months for the necessary equipment and infrastructure to

begin farming activities. Living in a remote area without transportation made it

difficult to establish farming operations and integrate into nearby communities.

Since initially the farms lacked infrastructure, only a few members of the

cooperatives decided to go to the farms when the government informed them that

it was available. They built makeshift structures so that they had a shelter to sleep

under and a place to cook. Many cooperative members who decided to go

temporarily left behind their children and partners in the city with the intention of

bringing their family once the infrastructure was constructed. Juan said,

For me the most difficult is to have my family in Caracas, to leave them

there . . . It is not that I left them, abandoned them. Rather it is I can’t bring

them because in reality there aren’t conditions here [adequate enough] in

order to bring them. There is no school nearby. We still don’t have houses.

Because, yes, I would be delighted with a life here working, producing, and

with my family. This is one of the most difficult parts. But we are moving

forward. (Personal interview)

10

Although I visited these farms multiple times and spoke informally with participants during these

visits, for logistical reasons I carried out most of the formal interviews on 24 November 2007. Unless

otherwise stated, subsequent references to personal interviews were carried out on this date as well.

© 2010 The Author – Journal compilation © 2010 Blackwell Publishing Ltd

260 Tiffany Linton Page

He went on to say, ‘When one goes to war, one doesn’t bring one’s family.This, for

us, is like a war, a beautiful war. Pretty. We don’t come here to shoot anybody.

This is a commitment so the family waits for you there.When everything is in good

condition, they will come here, for the war ended.’ Jorge, on Fundo Gato, echoed

Juan’s sentiments. ‘We are waiting for the houses in order to bring our families. We

are only the heads of households here.The family is not here.They are far away.We

are awaiting the houses for this [to bring the family]’ (Personal interview). Many

participants mentioned that one of the most difficult parts of the process was leaving

family behind during the initial phases of the project, which often lasted years.

Some who came to the farm left to return to their families in the city after waiting

for so long on the infrastructure and equipment (Personal interview).

There were few people actually on the farms. Participant estimates of the

number of ‘active’ members and the numbers listed on project documents were

always higher than the number I saw on the farms. David explained: ‘Originally,

we were 86 [people] . . . Now there are 36 but there is a little conflict because

the majority don’t want to come here until they [the government] give them

houses’ (Personal interview). At the time of interview, there were only two people

living on David’s farm. The remaining ‘active’ participants were still in the city.

Gonzalo explained, ‘Some have work and don’t want to come here. And there are

others that want both things, more than anything they are confused . . . They

thought the land was going to be . . . but it wasn’t that way. So many left’

(Personal interview). According to Juan, his cooperative had seven working

members, though I never saw more than three people on the farm when I

visited.11 According to Luis, a member of Fundo Revolución, originally there were

117 families organized into five cooperatives on his farm. Now there are three

cooperatives – one with one member, one with five members and one with ten

members. On Fundo Sueños I was told that six families were living on it, though

only two families were actively involved in the farming operations. This farm

was different from the others because it had houses, making it a more desirable

place to live. As a result, there was a slight twist on the project abandonment

phenomenon – more people on this farm than were actually working.12

Not all the absent cooperative members had abandoned the project according to

those on the farms. On Fundo Gato there were ten cooperative members on the

farm and I was told that there were ten more members in Caracas, who were still

planning on eventually moving to the farm. When asked about the cooperative

members who were in Caracas, Julia said, ‘Yes, they are involved. We call them and

they participate:“look there is this idea; we are going to do this thing” and they give

their opinion, whether yes or no’ (Personal interview). Alonso explained, ‘For now

the yield is not sufficient for twenty people because we have a family to maintain.

We are rotating. For a time one group goes; for another time comes a group’

(Personal interview). The yield was too low to sustain the whole cooperative. The

11

I suspect that the figures on ‘active’ membership included people who had not arrived, but had

not said that they were abandoning the project; or people who had been on the farm for months

and relatively recently had returned to Caracas.

12

Some cooperative members were living on the farm, but not helping out with the work. As a

result, there was not much planted. However, the farm had a couple thousand egg-producing

chickens. The eggs were bartered at the state subsidized grocery store chain for food to feed all

members on the farm.

© 2010 The Author – Journal compilation © 2010 Blackwell Publishing Ltd

Can the State Create Campesinos? 261

farms did not have many hectares sown because the trial period, during which they

obtained agricultural inputs, learned to plant different crops and tested out crops to

see which grew the best, was lengthy. Moreover, they lacked an irrigation system in

a part of the country that is extremely dry half the year.

All the VAC farms were waiting on ‘approved’ projects that kept getting post-

poned, including houses, wells and irrigation systems.The participants in many cases

did not really know why projects were not moving forward. They travelled to

Caracas to talk to people in the Land Institute and the Ministry of Agriculture to

get an explanation for the delays. They realized that the government was reluctant

to implement projects originally designed for a much larger group of people, but

the government was not saying that the projects had been cancelled. Instead, they

were often told in two more weeks, or in a month, the resources would arrive. But

the resources did not come when they said they would (VAC participant, personal

interview, 29 November 2007). They felt frustrated because they were promised

resources and they took an enormous risk, leaving behind what they had in the

cities to start a new life as farmers. These promised projects were integrally tied to

the success of their farming operations. Without a well from which to get water, a

pump to pump the water out and an irrigation system, they would only be able to

farm part of the year when there was rain.

The farmers and the government found themselves in a Catch-22. On the one

hand, people were reluctant to leave what they had to go to land with no

infrastructure, with only the promise that the government would build the infra-

structure. On the other hand, the government was reluctant to invest the resources

they promised in these farms when they saw that there were very few people

actually on the farms (Government employee, personal interview, 23 November

2007). From the government’s perspective, investment of resources on these farms

could potentially be a waste. The farm could fail and the entire site could be

abandoned. Ricardo, an employee of the Land Institute at the state level, said that

there were many projects approved for Fundo Revolución. They had received half of

the resources they had been promised. Ricardo said that the government’s head-

quarter offices in Caracas did not want to distribute the rest of the resources to

build the wells and houses until the other cooperative members showed up on the

farm (Ibid.). At the same time cooperative members still in the urban areas did not

want to come to the farm until there were houses for them. Luis, of Fundo

Revolución, said that there were still 20 more families in Caracas who planned to

come once the houses were built. Meanwhile, those who had come to the farm

were getting impatient and frustrated with the government because the promised

projects were not arriving along the timeline outlined at the beginning of the

process. David, from Fundo Zamora, explained,‘The project was to raise cattle, sheep,

goats and chickens. But we have problems in the cooperative . . . they haven’t given

us anything yet.’ He went on to say,‘We have a conflict.With the division that exists

[in our cooperative], it [the project] is paralyzed’ (Personal interview).

Social and Cultural Changes

Prior to arriving in Anzoateguí, some members of the cooperatives knew each other,

while others did not. Some of the participants on Fundo Gato recounted how they

organized meetings in their community in Caracas to find more families interested in

© 2010 The Author – Journal compilation © 2010 Blackwell Publishing Ltd

262 Tiffany Linton Page

participating in VAC (Personal interview). When I asked if the members of the

cooperative on Fundo Zamora were neighbours in the city where they came from, one

member told me, ‘No, we were from the same sector, but at a distance’ (personal

interview). Juan, from Fundo Rodríguez, replied to this same question,

Yes, almost all of us are from the same sector. Of course, some aren’t but

similarly [someone] was a family member of him [another cooperative

member] or we knew each other. At the root of this, we were interested and

we formed the cooperative. They gave us a loan and we came here to

experiment in Anzoateguí (Personal interview).

While not all participants necessarily knew each other beforehand, most participants

had some connection to the community. Beyond this, Juan is suggesting that, more

importantly, they shared a desire to participate in this social project and to support

the government. Some participants who did not know each other beforehand got

a chance to get to know each other through a course they took in Caracas, in

which they formed cooperatives and learned some basics about agriculture. Other

participants came from other cities in the country and never took these courses. On

Fundo Sueños, the members from Maracaibo had never met any of the other

participants until they arrived on the farm. Some people had to start from scratch

in building relationships and trust on the new farms; all had to start from scratch in

building a new community.

In rural Anzoateguí, there were vast stretches of relatively unpopulated space.

Consequently, the farms, for the most part, did not have neighbours close by.

VAC participants were not moving into an existing community. Rather they were

expected to be founders of new communities in which the government would build

infrastructure for basic social services, including a school and a health clinic. As the

pioneers of this plan,VAC participants found themselves alone.This sense of isolation

was exacerbated by the fact that so few cooperative members had come to the farm.

The people who volunteered to be part of this programme were generally people

who were highly mobilized, urban supporters of Chávez. In rural areas of Anzoateguí,

there was not an organized farmer movement for them to join. While there were

some loosely organized groups in the northern part of the state, they did not meet

regularly (Campesino leader, personal interview, 10 January 2008). None of the VAC

farms in this state were part of any organized farmer group. When I asked if they

heard about meetings or marches, Gonzalo responded,‘Here the radio signal is really

weak and there is no TV. . . . the marches, when we hear, they have already happened.

We can’t go.We are very few [on the farm].We have work to do.We can’t leave the

work to go to the marches’ (Personal interview). They also cannot leave the farms

unattended because of the rampant theft problem.The small number of people on the

farm put those on the farm in greater danger. Theft in the countryside, though less

than in urban areas, was still common; with only a few people on the farm (and if the

farm is abandoned altogether) theft of the invested resources, and potentially assault,

was likely.13 This effectively meant that these formerly politically mobilized people

13

During my time in Anzoateguí, I heard about a lot of theft from the farms. One farm had their

cows stolen in the middle of the night. Another farm, that had only two people on the land, was held

up at gunpoint. The farmers were tied up and everything was stolen (their vehicle, the transformer

for the electricity, the pump that brought the water up out of the well and their cows).

© 2010 The Author – Journal compilation © 2010 Blackwell Publishing Ltd

Can the State Create Campesinos? 263

did not hear about or were not able to participate in political activity.The lack of an

organized small farmer movement may not have been the case in every area of the

country where VAC farms were located. However, the government intentionally

locatedVAC farms in areas where there was not much agricultural production, which

increased the likelihood that there was also not much small farmer organizing. This

demobilization of VAC participants – who were strong supporters of the President –

was not in the government’s interest as it was struggling against the destabilizing

efforts of the domestic elite.

When they relocated, participants lost their social networks and had to adapt to

the changes involved in moving from an urban area with activity to a remote rural

area where, in many cases, the closest pueblo was at least a half hour away by car.

David told me,‘Being here is different . . .We went out [in the city], went to a party,

here no . . . there is nothing here.The closest pueblo is 15 to 20 kilometres’ (Personal

interview).The town he referred to was extremely small and had very little activity,

a sharp contrast from the urban areas the participants came from. Many participants

expressed the sentiment that they were not prepared for life in the countryside.

Roberto reported that the government asked potential participants,‘Do you like the

countryside? Do you want to work in the countryside?’ And if people said yes, they

were sent to the farm. Roberto felt that they did not know what they were getting

into when they decided to participate. Luis, from Fundo Revolución, said that the

government promised them things and it was not the way they thought that it

would be. Part of the disappointment some members experienced on the farm was

due to the failure of the government to provide in a timely manner basic infra-

structure and equipment, as well as training; part was due to the isolation and

loneliness participants experienced; and part was due to the difficulty of shifting

one’s mindset from a capitalist model to a socialist model. Participants were used to

getting paid a certain amount per hour of work and that being the end of their

responsibility. For some it was difficult shifting their thinking to embrace their new

relationship vis-à-vis work – running a business as part of a collective and earning

based on your portion of profits, not wages. It was particularly difficult at the

beginning when the farming operations brought in little income.

The Dutch Disease effects of oil, prevalent in the oil-producing state of

Anzoateguí, further reduced the purchasing power of the new farmers.14 Many

people living in rural areas of Anzoateguí were not farming because they could earn

more working only three months of the year for one of the oil companies than

farming year-round. As a result, there was not much agricultural production in this

part of the country. Ironically, the limited agricultural production was a factor that

led the government to place the VAC farms there. The oil industry (because of its

capital-intensive nature) tends to pay relatively high wages. Consequently, other

employers, competing with the oil industry for workers, must pay higher wages than

they would pay in an area of the country without oil operations. Labour is one of

the inputs in production so higher wages gets passed along to consumers in the way

14

When the price of oil increases, it hurts other sectors of the economy, such as agriculture and

manufacturing.The export of oil at these higher prices generates more foreign exchange, making the

currency stronger. It becomes cheaper to import goods than to produce domestically so, ultimately,

other sectors of the economy are crowded out (http://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/fandd/2003/

03/ebra.htm).

© 2010 The Author – Journal compilation © 2010 Blackwell Publishing Ltd

264 Tiffany Linton Page

of higher prices for the finished product. As a result, price inflation occurs locally;

goods and services in oil states tend to cost more than in non-oil states. Farmers in

cooperatives and family farmers do not work for wages. Their income depends on

how much they produce and sell. They do not benefit from the higher wages, but

they face the higher prices on goods and services. This inflation effect from the oil

industry discourages people from going into agriculture. When asked about the

most difficult part of the VAC process, Gonzalo replied,‘The agriculture . . . because

if you go to the market to sell your produce . . . the feeling that you have is that you

aren’t earning anything, you are recuperating a part of what you invested and

nothing more.You don’t earn anything’ (Personal interview).The local effects of oil

in Anzoateguí made agriculture an economically unattractive profession.

Learning to Farm

Although some of the VAC participants may have been born in the countryside

and learned about agriculture as a child, it had been many years since then. Many

migrated to the cities before adulthood or as young adults and were never

responsible for farming operations in their household. Moreover, much of what

they did learn had been forgotten. Gonzalo explained, ‘I was in the countryside.

I was a campesino, like everybody, we come from the countryside . . . but the little

that you learn, after years you forget it’ (Personal interview). Raul mentioned that

he had grown a few crops, but had much to learn. ‘I have experience in the

cultivation of bananas and planting yucca. While I lack a lot of experience, each

day one learns more. And for this we are here, to learn’ (Personal interview).

Others had no experience at all. Participants depended on the government to

provide them with the knowledge they lacked. They decided to participate in

VAC based on the faith that the government would provide the necessary train-

ing. Jorge said that although they did not have the experience or knowledge to

know when it would rain, what they had was ‘help from the President, like a

guaranteed help that we did not have before. This gives us the belief that I can

go to the countryside because I can project what I want because he [President

Hugo Chávez] is going to help me’ (Personal interview). They viewed the gov-

ernment as their partner.

Yet, many of the VAC participants felt that they had not received the necessary

training in agriculture. Although some received some training prior to moving

to Anzoateguí, since arrival on the farm they felt abandoned. Juan told me that

they had not received an intensive course on farming since they arrived on the

farm. ‘When we began we were 19 people, but always something happens, not

everything is perfect. A lot left because in reality there hasn’t been technical

assistance’ (Personal interview). Lack of technical support was one factor that led to

project abandonment.

I was told that INTI, the government institution responsible for all but one of

these farms, came ‘once a month or so’ (VAC participant, personal interview).

Fundación CIARA (CIARA), a government institution that provides technical assis-

tance to farmers, visited on a weekly basis and other institutions of the government

came every once in a while.When I witnessed these institutions’ visits to the farm,

they often spent about five minutes looking at the crops, then they briefly told the

© 2010 The Author – Journal compilation © 2010 Blackwell Publishing Ltd

Can the State Create Campesinos? 265

one cooperative member, who was walking around with them, one or two things

that ought to be done, then they spent five to ten minutes filling out their report

on the visit, which they later turned into their boss.The majority of their time was

spent driving to and from the farm. Even when they did visit, it was not clear that

the VAC participants learned much from them.

VAC participants wished that the agricultural extensionists spent more time on

the farms and taught through demonstration. One farmer described the classes they

received in the following way: ‘They give us a seat and we listen . . . Them. There.

Like professors and a blackboard. There one learns, for example, the ABC vaccine

that is given every fifteen days or every month. They put a vaccine to prevent a

sickness or something like that. They come for a little bit and then they go’

(Personal interview). Another member of this farm said, ‘It needs to be more

continuous that they come’ (Personal interview). Raul wanted the technical experts

to come to the farm and teach two hours every day.

In the countryside one must work both the practical and the theoretical. The

agronomists have the theory. The campesino has the practical experience. We

are not going to say no to the theory. The theory is necessary. Experience is

demonstrated with actions. It is not saying this is the way it is done. Let’s go

to the fields and let’s do it to see how it is, to learn through doing. (Personal

interview)

They wanted the agricultural extensionists to show them rather than tell them how

to farm. ‘For this reason I say practice and theory need to be managed in this way

because if they only tell us, tomorrow I won’t remember what they told me’

(Personal interview). They felt that much of what they had learned had been

through trial and error.

The problem is that there are a lot of technical experts but they do not teach

what they should. I believe that the objectives that they have drawn up, they

do not meet.Therefore, we continue practically in the same way because what

we are doing here is the experience that we brought of the little that we

learned. (Personal interview)

Participants wanted both more training and more effective training.

Part of the reason the agricultural extensionists did not come to the farms more

often was a lack of transportation. In rural areas of Anzoateguí, often there was no

public transportation. The extensionists were dependent on whether they could

secure access to a vehicle to visit the farms.The INTI office in El Tigre, the closest

city to most of the farms, had a vehicle shortage and as a result they rarely visited the

farms. Employees who had their own vehicles would use those to visit the farms, but

few government employees had their own vehicles. In early November 2007, an

agricultural extensionist from the government institution Instituto Nacional de Desar-

rollo Rural (INDER), The National Rural Development Institute, came to Fundo

Revolución to inform the farmers that two Cuban extensionists could come daily to

the farm to teach them. However, the cooperative would have to drive a long distance

each morning to pick them up and in the evening to take them home. In addition,

they were going to have to feed them during the day. Since the monthly stipend that

© 2010 The Author – Journal compilation © 2010 Blackwell Publishing Ltd

266 Tiffany Linton Page

participants received at the beginning had come to an end and their farming

operations had yet to really take off, they had very little money to even buy food for

themselves.15 They asked if the Cubans could live in the town nearby where the kids

went to school because then it would be easier for them to transport them back and

forth from the farm.According to Elsa, the cooperative’s President, the representative

from INDER, did not consider that a possibility. She was told the Cubans needed to

be near medical facilities and there were not any in the nearby town. In the end, the

people on the farm opted not to have the support of the Cubans (VAC participant,

personal interview, 29 November 2007). A similar problem occurred on Fundo

Rodríguez. When I asked about the Cuban technical experts, Juan explained, ‘The

Cubans, yes, they came but there is a problem.They don’t have transportation. One

has to go get them.And we don’t have transportation either’ (Personal interview). On

Fundo Sueños, there was a vacant house, which was supposed to house some Cubans

from Misión Campo Adentro, the government programme that brought Cuban

agricultural experts to Venezuela to advise the government and help implement the

new policies. But, according to Roberto, the President of the cooperative, the Cubans

did not want to live on the farm.

An additional difficulty participants placed in Anzoateguí faced was the poor soil

quality, which made farming more difficult. In some parts, the soil looked almost

like sand. Juan explained how they had to begin:

We planted cantaloupe, watermelon, corn and other little things over there

but not in large extensions, not on a large scale. Rather, since this is a test

period, also for the type of soil, the soil is really acidic. So one can’t run the

risk, neither the institutions nor us, of planting a lot because we don’t know

if we are going to lose it. This is a test of what can be done, of what can be

planted in order to see if the land is suitable. But now we know that the land

is suitable. After we clear [the land] again, we can do a complete planting of

whichever crop. (Personal interview)

Juan’s comment suggests that the government placed people with little-to-no

farming experience on land that the government was not sure was agriculturally

fertile. It turned out to be sufficiently fertile to grow some crops, but required more

work and knowledge than soils of higher quality. When I asked Gonzalo what had

been the most difficult part of the process, he said,

The agriculture. The land here is really poor. You plant something and you

need to be constant because suddenly the plant dies and it doesn’t give you

production. Or we are going to need to make [raised] beds with organic

material and plant these beds. I think this is better. But we are lacking organic

material. (Personal interview)

The participants struggled with the agricultural production not only because they

lacked the necessary knowledge, but also because they had to deal with difficult

environmental conditions.

15

Each cooperative member was given a monthly stipend for eight months, which they got

extended for another three months. The stipend had ended.

© 2010 The Author – Journal compilation © 2010 Blackwell Publishing Ltd

Can the State Create Campesinos? 267

Participant Responses

As mentioned earlier, some participants responded to these challenges by abandon-

ing the project. As Juan put it, ‘If the institutions [of the government] don’t fulfil

[their duties], sometimes we begin to think about our kids, our wives, who are very

far away’ (Personal interview). Others had not given up: ‘We came here first almost

three years ago, cultivating, raising animals. And it was a little difficult. There was

nothing easy to get where we are today. But when one wants things and one puts

one’s heart into it, one gets it’ (Personal interview).

This cooperative had become creative about ways to survive in the short term

until farming operations took-off. ‘And now that there is no more social support

[the monthly stipend from the government], we could die of hunger. We need to

be inventive, to be intelligent. How can we, ourselves, look for food in order to have

something more secure’ (Personal interview). Since the resources were slow to come

and agricultural production had got off to a slow start, the members of Fundo Gato

came up with a business plan to supplement their income.

Cooperativism is flexible. We are an agricultural cooperative, but we have the

option that we can also be business people because this can be included in our

cooperative.Why? Because we take what is the weakness and the strength.We

have strength over there. Over there is a national highway and we want to be

farmers, but the agriculture for now is not going to give enough to sustain us

so we are going to take advantage of the strength.The strength is the highway

that is there. We are going to put a restaurant there, without abandoning the

planting that permits us at least food. Because if not, there is no food; there

is no life. (Personal interview)

Although their farm was in a remote rural area, it was along a highway, albeit one

with limited traffic. They were planning on opening a restaurant on the side of the

highway in which they would use some of their farm produce to make food.

This is our project. It is to ensure the food . . . and have something to send to

the family there, because this money one sees daily. Because if you plant

something . . . you have to wait three months and if a pest comes . . . it isn’t

certain. With this that we are doing there, we are not going to forget about

raising animals or the agriculture. No. There [in the restaurant] one person

will be assigned, and us here raising the animals and planting the crops. This

is to guarantee food . . . until we are productive. After the work is productive

and there is production there, much better. But to have a base where one can

hold on to survive here while there isn’t production, this is the decision that

we are making here (Personal interview).

Back in the city, many of the members had been involved in the informal economy

making and selling goods; they wanted to put their skills to use in this new context

to generate supplemental income. The idea for the restaurant came about because

one participant had worked as a cook in the past. Others were talking about making

goods to sell in their roadside restaurant/store. This move, if successful, would allow

cooperative members to gain some financial independence from the government.

All the VAC farms, and the people on these farms, were completely dependent on

© 2010 The Author – Journal compilation © 2010 Blackwell Publishing Ltd