Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Effect of DHA Supplementation During Pregnancy On Maternal Depression and Neurodevelopment of Young Children

Effect of DHA Supplementation During Pregnancy On Maternal Depression and Neurodevelopment of Young Children

Uploaded by

gedeOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Effect of DHA Supplementation During Pregnancy On Maternal Depression and Neurodevelopment of Young Children

Effect of DHA Supplementation During Pregnancy On Maternal Depression and Neurodevelopment of Young Children

Uploaded by

gedeCopyright:

Available Formats

ORIGINAL CONTRIBUTION

Effect of DHA Supplementation

During Pregnancy on Maternal Depression

and Neurodevelopment of Young Children

A Randomized Controlled Trial

Maria Makrides, BSc, BND, PhD Context Uncertainty about the benefits of dietary docosahexaenoic acid (DHA) for

Robert A. Gibson, BSc, PhD pregnant women and their children exists, despite international recommendations that

Andrew J. McPhee, MBBS pregnant women increase their DHA intakes.

Lisa Yelland, BSc Objective To determine whether increasing DHA during the last half of pregnancy

will result in fewer women with high levels of depressive symptoms and enhance the

Julie Quinlivan, MBBS, PhD neurodevelopmental outcome of their children.

Philip Ryan, MBBS, BSc Design, Setting, and Participants A double-blind, multicenter, randomized con-

and the DOMInO Investigative Team trolled trial (DHA to Optimize Mother Infant Outcome [DOMInO] trial) in 5 Austra-

lian maternity hospitals of 2399 women who were less than 21 weeks’ gestation with

E

PIDEMIOLOGICAL INVESTIGA - singleton pregnancies and who were recruited between October 31, 2005, and Janu-

tions from the United States and ary 11, 2008. Follow-up of children (n=726) was completed December 16, 2009.

Europe demonstrate that higher Intervention Docosahexaenoic acid–rich fish oil capsules (providing 800 mg/d of

intakes of n-3 long-chain poly- DHA) or matched vegetable oil capsules without DHA from study entry to birth.

unsaturated fatty acids (LCPUFA) from Main Outcome Measures High levels of depressive symptoms in mothers as indi-

fish and seafood during pregnancy are cated by a score of more than 12 on the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale at 6 weeks

associated with a reduced risk of de- or 6 months postpartum. Cognitive and language development in children as assessed

pressive symptoms in the postnatal pe- by the Bayley Scales of Infant and Toddler Development, Third Edition, at 18 months.

riod,1 as well as improved developmen- Results Of 2399 women enrolled, 96.7% completed the trial. The percentage of

tal outcomes in the offspring.2,3 Of the women with high levels of depressive symptoms during the first 6 months postpar-

n-3 LCPUFA, it is hypothesized that tum did not differ between the DHA and control groups (9.67% vs 11.19%; adjusted

docosahexaenoic acid (DHA) may be relative risk, 0.85; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.70-1.02; P=.09). Mean cognitive

responsible for the observed associa- composite scores (adjusted mean difference, 0.01; 95% CI, −1.36 to 1.37; P=.99) and

mean language composite scores (adjusted mean difference, −1.42; 95% CI, −3.07

tions based on estimates of dietary re-

to 0.22; P=.09) of children in the DHA group did not differ from children in the con-

quirements during pregnancy and the trol group.

results of experimental animal stud-

ies.4 However, n-3 LCPUFA interven- Conclusion The use of DHA-rich fish oil capsules compared with vegetable oil cap-

sules during pregnancy did not result in lower levels of postpartum depression in moth-

tion trials in human pregnancy have re- ers or improved cognitive and language development in their offspring during early

ported mixed results and have not been childhood.

conclusive largely because of method-

Trial Registration anzctr.org.au Identifier: ACTRN12605000569606

ological limitations. Studies focused on

JAMA. 2010;304(15):1675-1683 www.jama.com

perinatal mood have had open-label de-

signs, small sample sizes, or large at-

Author Affiliations: Child Nutrition Research Centre, University of Notre Dame Australia, and Sunshine Hos-

trition, and most did not analyze by in- Women’s and Children’s Hospital, Flinders Medical Cen- pital, Melbourne (Dr Quinlivan), Australia.

tention-to-treat. 5 Similarly, trials tre, and Women’s and Children’s Health Research In- The DOMInO Investigative Team members and their

stitute, Adelaide (Drs Makrides and Gibson); Schools author affiliations are listed at the end of this article.

focused on the developmental out- of Pediatrics and Reproductive Health (Dr Makrides), Corresponding Author: Maria Makrides, BSc, BND,

comes of the children have made post- Agriculture, Food and Wine (Dr Gibson), and Popula- PhD, Child Nutrition Research Centre, Women’s and

tion Health and Clinical Practice (Dr Ryan and Ms Yel- Children’s Health Research Institute, Women’s and

land), University of Adelaide, Adelaide; Department of Children’s Hospital, 72 King William Rd, North Ad-

See also p 1717 and Patient Page. Neonatal Medicine, Women’s and Children’s Hospi- elaide SA 5006, Australia (maria.makrides@health.sa

tal, Adelaide (Dr McPhee); and School of Medicine, .gov.au).

©2010 American Medical Association. All rights reserved. (Reprinted) JAMA, October 20, 2010—Vol 304, No. 15 1675

Downloaded From: on 03/17/2018

DHA SUPPLEMENTATION DURING PREGNANCY AND MATERNAL DEPRESSION

randomization exclusions,6,7 had high Randomization and Trial Entry ter enrollment (approximately 22

attrition rates, and lacked power.6-9 De- Women were randomly assigned a weeks’ gestation) and at 28 and 36

spite the paucity of evidence, recom- unique study number and treatment weeks’ gestation to document adverse

mendations exist to increase intake of group allocation through a computer- gastrointestinal or bleeding events and

DHA in pregnancy,4,10 and the nutri- driven telephone randomization ser- to monitor and encourage adherence.

tional supplement industry success- vice according to an independently gen- The concentration of DHA in cord

fully markets prenatal supplements with erated randomization schedule, with blood was measured using capillary gas

DHA to optimize brain function of balanced variable-sized blocks. Strati- chromatography14 to provide an inde-

mother and infant. Before DHA supple- fication was by center and parity (first pendent biomarker of adherence. An-

mentation in pregnancy becomes wide- birth vs subsequent birth). Baseline tenatal hospitalizations, antenatal hem-

spread, it is important to know not only characteristics, including maternal age, orrhage, pregnancy and birth outcomes,

if there are benefits, but also of any risks medical diagnosis of previous or cur- and postpartum hemorrhage were re-

for either the mother or child. The DHA rent depression, current treatment for corded from a review of medical rec-

to Optimize Mother Infant Outcome depression, social support using the Ma- ords.

(DOMInO) trial was designed primar- ternal Social Support Index,11 weight,

ily to assess whether DHA supplemen- highest level of education, occupa- Outcome Assessments

tation during the last half of preg- tion, and smoking status, were re- Women completed a self-adminis-

nancy reduced the risk of depressed corded. tered Edinburgh Postnatal Depression

maternal mood during the postpar- Scale (EPDS) at 6 weeks and 6 months

tum period and improved early cogni- Dietary Treatments postpartum, and the primary mater-

tive development in the offspring. Women allocated to the DHA group nal outcome was a high level of depres-

were asked to consume three 500- sive symptoms documented as a score

METHODS mg/d capsules of DHA-rich fish oil con- of more than 12 on the EPDS at 6 weeks

Study Design centrate, providing 800 mg/d of DHA or 6 months postpartum. Although a

We conducted a double-blind, multi- and 100 mg/d of eicosapentaenoic acid high EPDS score cannot in itself con-

center, randomized controlled trial in (EPA, 20:5n-3; Incromega 500 TG, firm a diagnosis of depression, a score

5 Australian perinatal centers. Ap- Croda Chemicals, East Yorkshire, En- of more than 12 is widely used to in-

proval was granted by the local insti- gland); and women in the control group dicate a probable depressive disorder.

tutional review boards (human re- were asked to take three 500-mg/d veg- Validation studies indicate high sensi-

search ethics committees) of each center etable oil capsules without DHA. The tivity (68%-95%) and high specificity

and written informed consent was ob- dose of 800 mg/d was chosen because (78%-96%) of the EPDS against a clini-

tained from each participant. An inde- this was above the estimated thresh- cal psychiatric diagnosis of depres-

pendent serious adverse event commit- old associated with lower risk of de- sion.15-17 Women with a score of more

tee reviewed all deaths, admissions to pressed maternal mood and higher than 12 on the EPDS were referred to

level III care, and major congenital scores on developmental outcomes of their general practitioners for more for-

abnormalities. children,1 as well as being consistent mal medical assessment. Secondary

Women with singleton pregnancies with the estimated requirement to cover analyses compared the percentage of

at less than 21 weeks’ gestation were ap- 97% of the population. 12 The veg- women medically diagnosed with de-

proached by study research assistants etable oil capsules contained a blend of pression or receiving treatment for de-

while attending routine antenatal ap- 3 nongenetically modified oils (rape- pression, as reported by women dur-

pointments to participate in the trial. seed, sunflower, and palm) in equal ing pregnancy and at 6 weeks and 6

Women were excluded if they were al- proportions. This blend of oils was de- months postpartum, between the 2

ready taking a prenatal supplement with signed to match the polyunsaturated, groups.

DHA, their fetus had a known major ab- monounsaturated, and saturated fatty The primary childhood outcome of

normality, they had a bleeding disor- acid profile of the average Australian neurodevelopment at 18 months was

der in which tuna oil was contraindi- diet.13 Women were asked to take their assessed by 1 of 4 study psychologists

cated, were taking anticoagulant assigned capsules daily, from study en- using the Cognitive and Language

therapy, had a documented history of try until birth of their child. All cap- Composite Scales of the Bayley Scales

drug or alcohol abuse, were participat- sules were similar in size, shape, and of Infant and Toddler Development,

ing in another fatty acid trial, were un- color and donated by Efamol, Surrey, Third Edition (BSID-III). The cogni-

able to give written informed consent, England. tive scale evaluates abilities, such as sen-

or if English was not the main lan- sorimotor development, exploration

guage spoken at home. Recruitment for Treatment Phase Monitoring and manipulation, object relatedness,

the trial began October 31, 2005, and During the intervention period, trial as- concept formation, memory, and simple

ended January 11, 2008. sistants telephoned women 2 weeks af- problem solving, and the language scale

1676 JAMA, October 20, 2010—Vol 304, No. 15 (Reprinted) ©2010 American Medical Association. All rights reserved.

Downloaded From: on 03/17/2018

DHA SUPPLEMENTATION DURING PREGNANCY AND MATERNAL DEPRESSION

is a composite of receptive communi- tent with the epidemiological data from cluded a treatment ⫻ time interaction.

cation (verbal comprehension, vocabu- England.1 We planned to enroll 2280 Separate estimates of treatment effect

lary) and expressive communication women in total, allowing for 2% loss to are presented at each time point if the

(babbling, gesturing, and utterances). follow-up. interaction was significant or if sepa-

The motor scale, which evaluates both A minimum clinically meaningful rate estimates were prespecified. Where

gross and fine motor functioning, as difference in developmental scores is the interaction was not significant, this

well as the parental report scales of so- considered to be of the order of 4 was removed from the model and an

cial-emotional behavior and adaptive points.19 Studies showing differences overall estimate of treatment effect is

behavior were assessed as secondary between nutritional or environment in- presented. Analysis of the primary ma-

outcome measures. The raw scores for terventions of 4 to 5 points or greater ternal depression outcome was per-

each of the scales are standardized to a have been catalysts for changes in health formed on all women and on the sub-

mean of 100 with an SD of 15 (range, policy.20,21 To detect a difference of 5 group with a previous or current

50-150). The standardized scores were points between groups (mean [SD], 100 diagnosis of depression at trial entry.

also classified into the categories of ac- [15]) with 80% power (␣=.05) for boys Outcomes derived from the BSID-III as-

celerated performance (⬎115), within and girls separately, we required a total sessment took into account both the

normal limits (85-115), and delayed sample size of 572 children. We there- sampling design and probability

performance (⬍85). fore randomly sampled 630 term chil- weights, calculated as the inverse of the

All 96 preterm children and 630 ran- dren such that half were male, allow- probability of selection. A priori sec-

domly selected term children from Ad- ing for 10% loss to follow-up. The ondary analyses were performed to test

elaide, Australia, were chosen for BSID- selection process occurred between for effect modification by sex and re-

III assessment (N = 726). The families birth and 1 year. All children born pre- sults are presented both overall and by

and trial staff did not know which chil- term were included in the follow-up to sex, because previous studies suggest

dren had been randomly selected for enable modeling of the effect of DHA that boys and girls may respond differ-

follow-up until the infants were 12 supplementation in pregnancy on all ently to DHA supplementation.

months old. At this time, trial assis- children; those born preterm being Both unadjusted and adjusted analy-

tants in each center were supplied with more nutritionally and more develop- ses were performed, with adjustment

birthday cards for all children, and those mentally vulnerable than children born for the stratification variables, center,

selected for follow-up were informed at term.22 and parity, as well as any prespecified

and invited for a BSID-III appoint- All analyses were performed accord- potential confounders. Statistical sig-

ment. The last BSID-III assessment was ing to the intention-to-treat principle. nificance was assessed at the 2-sided

completed on December 16, 2009. Multiple imputation was used to deal P⬍.05 level. No adjustment was made

with missing data (outcomes and co- for multiple comparisons and results for

Sample Size and Statistical variates) and create 50 complete data secondary outcomes should be inter-

Analysis sets for analysis. Sensitivity analyses preted with caution unless they are

Epidemiological data suggest a 7% to were performed on the original data and highly significant. Analyses were per-

8% absolute reduction (from approxi- on imputed data using different seeds formed by using SAS version 9.2 (SAS

mately 16% to 9%) in the prevalence for imputation and different imputa- Institute Inc, Cary, North Carolina) and

of high levels of depressive symptoms tion models. All produced similar re- Stata Release 11 (Statacorp LP, Col-

when n-3 LCPUFA intake is increased sults; therefore, we reported the re- lege Station, Texas).

from the typically low-level intakes sults of the imputed analyses.

commonly observed in Westernized Continuous outcomes were ana- RESULTS

diets to more than 1 g/d.1 Although lyzed by using linear regression mod- The number of women screened and

these data were derived from a well- els, following log transformations where assessed for the trial, randomly

controlled cohort study, we expected appropriate, with treatment effects ex- assigned to receive either DHA or con-

that any effect size of a DHA-rich in- pressed as mean differences. Binary out- trol supplementation, are shown in

tervention would be smaller because of comes were analyzed using log bino- the FIGURE. A total of 2399 women

possible residual confounding. We mial regression models, with treatment were enrolled and adequate data for

therefore powered our trial to detect an effects expressed as relative risks (RRs) the analysis of the primary outcome

absolute reduction of 4.2% (from 16.9% or Fisher exact test for rare outcomes. were available for 2320 women

to 12.7%) in depressive symptoms with Time-to-event outcomes were ana- (97.3% in the DHA group and 96.1%

80% power (␣=.05), requiring a sample lyzed by using stratified log-rank tests. in the control group). In addition,

size of 1121 women per group. The For outcomes measured at multiple 694 children (95.6% of those

control rate of depressive symptoms time points, dependence was ac- selected for follow-up) were assessed

was estimated from Australian popu- counted for using generalized estimat- at 18 months. Other outcomes and

lation data,18 which was also consis- ing equations. Models initially in- covariates were generally available

©2010 American Medical Association. All rights reserved. (Reprinted) JAMA, October 20, 2010—Vol 304, No. 15 1677

Downloaded From: on 03/17/2018

DHA SUPPLEMENTATION DURING PREGNANCY AND MATERNAL DEPRESSION

for more than 95% of participants. acids, P ⬍ .001 based on a comparison months postpartum did not differ be-

The demographic and clinical char- of mean log-transformed values). At 28 tween the DHA and control groups

acteristics of the women at random- weeks’ gestation, 35.6% of mothers re- (9.67% vs 11.19%; adjusted RR, 0.85;

ization were comparable between the ported that they had not missed tak- 95% CI, 0.70-1.02; P =.09) (TABLE 2).

2 groups, both overall (TABLE 1) and ing any capsules and an additional Depressive symptoms were more com-

for the subset assessed at 18 months 34.5% reported that they had missed 3 mon among women with a previous or

(eTable 1). The families of children se- or less per week (from a total of 21 cap- current diagnosis of depression at trial

lected for follow-up also had similar sules per week). Fewer than 2% of entry but did not differ between groups.

baseline characteristics to those of all mothers in each group chose not to take The percentage of women with a new

other children in the trial (eTable 2). any capsules. medical diagnosis for depression dur-

Docosahexaenoic acid concentration in ing the trial or a diagnosis requiring

the plasma phospholipids of cord blood Efficacy treatment also did not differ between

from women in the high-DHA group The percentage of women reporting groups.

was greater than control (median, high levels of depressive symptoms Mean cognitive scores of children

7.22% vs 6.09% total phospholipid fatty (EPDS score ⬎12) during the first 6 from women allocated to the DHA

group did not differ from mean scores

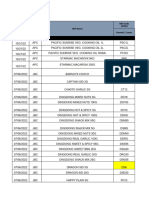

Figure. Flow of Participants Through the Trial of children of women from the con-

trol group, although fewer children

7821 Women screened for eligibility from the DHA group had cognitive

scores indicating delayed cognitive de-

5422 Women excluded velopment compared with controls

3658 Did not meet inclusion criteriaa (TABLE 3). Overall, mean language

303 Gestational age >20 weeks

205 Fetal abnormality scores also did not differ between

45 Multiple pregnancy

525 Poor comprehension of English

groups; however, a significant treat-

245 Contraindication to tuna oil ment ⫻ sex interaction indicated a dif-

114 History of substance abuse

2337 Taking supplements with DHA

ferential response of boys and girls.

23 Participating in other fatty acid trial Girls from the DHA group had a lower

1764 Refused to participate

mean language score than girls from the

control group, as well as an increased

2399 Women randomized risk of delayed language develop-

ment, and the response of boys did not

differ between groups. For the second-

1197 Women randomized to DHA supplement 1202 Women randomized to control supplement

ary developmental outcomes, motor de-

velopment, social-emotional behav-

1179 Women completed to 6 mo postpartum 1166 Women completed to 6 mo postpartum ior, and adaptive behavior did not differ

17 Women withdrew consent 36 Women withdrew consent

1 Woman lost to follow-up 0 Women lost to follow-up

between groups overall, although girls

exposed to DHA in utero had poorer

mean adaptive behavior scores than

1197 Women included in primary analysis 1202 Women included in primary analysis

girls from the control group.

The secondary clinical outcomes of

351 Infants selected for BSID-III

39 Preterm

375 Infants selected for BSID-III

57 Preterm

the infants are shown in TABLE 4. There

312 Randomly selected term 318 Randomly selected term were fewer very preterm births (⬍34

weeks’ gestation) in the DHA group

333 Infants completed 18 mo BSID-III 361 Infants completed 18 mo BSID-III

compared with the control group

36 Preterm 53 Preterm (1.09% vs 2.25%; adjusted RR, 0.49;

297 Randomly selected term 308 Randomly selected term

95% CI, 0.25-0.94; P =.03), but there

were more postterm births requiring ob-

12 Infants lost to follow-up 13 Infants lost to follow-up stetric intervention (inductions or ce-

1 Infant died after selection 1 Infant died after selection

5 Parents withdrew consent sarean deliveries) in the DHA group

compared with the control group

351 Infants included in BSID-III analysis 375 Infants included in BSID-III analysis

(17.59% vs 13.72%; adjusted RR, 1.28;

95% CI, 1.06-1.54; P=.01). Mean birth

DHA indicates docosahexaenoic acid; BSID-III, Bayley Scales of Infant and Toddler Development, Third Edi- weight was 68 g (95% CI, 23-114 g;

tion. P=.003) heavier and fewer infants were

aWomen could be ineligible for more than 1 reason.

of low birth weight (3.41% vs 5.27%;

1678 JAMA, October 20, 2010—Vol 304, No. 15 (Reprinted) ©2010 American Medical Association. All rights reserved.

Downloaded From: on 03/17/2018

DHA SUPPLEMENTATION DURING PREGNANCY AND MATERNAL DEPRESSION

adjusted RR, 0.65; 95% CI, 0.44-0.96; Thirty-six infants (3.01%) from the jor congenital abnormality, or death

P = .03) in the DHA group compared DHA group compared with 54 infants (Table 5). There were significantly

with the control group. However, mean (4.49%) in the control group experi- fewer infants with any admissions to

birth weight z scores (corrected for ges- enced at least 1 serious adverse event neonatal intensive care in the DHA

tational age and sex) did not differ be- (RR, 0.67; 95% CI, 0.44-1.01; P =.06), group compared with the control group

tween groups, indicating that group dif- defined as admission to level III (in- (1.75% vs 3.08%; RR, 0.57; 95% CI,

ferences in birth size were largely a tensive care) hospital treatment, ma- 0.34-0.97; P =.04), probably driven by

function of gestational age at birth.

Safety Table 1. Baseline Demographic and Clinical Characteristics a

DHA Supplement Control Supplement

The frequency of hemorrhage and an- Characteristics (n = 1197) (n = 1202)

tenatal hospitalizations did not differ Recruitment hospital

between groups. Similarly, there were Campbelltown Hospital 123 (10.3) 123 (10.2)

no differences between the groups in Flinders Medical Center and private 312 (26.1) 313 (26.0)

hospitals

maternal report of nose bleeds, vagi-

Royal Brisbane and Women’s Hospital 67 (5.6) 67 (5.6)

nal blood loss, constipation, nausea, or

Sunshine Hospital 178 (14.9) 181 (15.1)

vomiting at 28 and 36 weeks’ gesta-

Women’s and Children’s Hospital 517 (43.2) 518 (43.1)

tion. More women in the DHA group

Mother’s age at trial entry, mean (SD), y 28.9 (5.7) 28.9 (5.6)

reported eructations compared with the

Gestational age at trial entry, median (IQR), wk 19.0 (19.0-20.0) 19.0 (19.0-20.0)

control group (43.6% vs 25.6%; ad-

Primiparous 471 (39.3) 474 (39.4)

justed RR, 1.68; 95% CI, 1.50-1.89;

Mother completed secondary education 755 (63.1) 760 (63.2)

P ⬍ .001 at 28 weeks’ gestation and

Mother completed further education 816 (68.2) 824 (68.6)

41.5% vs 29.2%; adjusted RR, 1.41; 95%

MSSI score, median (IQR) 28.5 (25.0-31.0) 29.0 (25.0-31.0)

CI, 1.26-1.58; P⬍.001 at 36 weeks’ ges-

Mother smoked at trial entry or leading up to 358 (29.9) 407 (33.9)

tation); however, fewer women from pregnancy

the DHA group reported diarrhea Mother has previous or current medical 298 (24.9) 287 (23.9)

(13.4% vs 16.1%; adjusted RR, 0.83; diagnosis of depression

95% CI, 0.71-0.96; P=.01). There were Mother undergoing current treatment for 61 (5.1) 65 (5.4)

depression

no maternal deaths and 2 women from

Infant male sex 605 (50.5) 591 (49.2)

each group required level III (inten- Abbreviations: DHA, docosahexaenoic acid; IQR, interquartile range; MSSI, Maternal Social Support Index.

sive care) hospital treatment (TABLE 5). a Data are expressed as No. (%), unless otherwise indicated.

Table 2. Outcomes From the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS) a

DHA Supplement Control Supplement

(n = 1197) (n = 1202) Unadjusted Adjusted b

P P

Outcomes No. % (95% CI) No. % (95% CI) RR (95% CI) Value RR (95% CI) Value

EPDS score ⬎12 for all women 116 9.67 (8.36-11.19) 134 11.19 (9.80-12.78) 0.86 (0.71-1.05) .15 0.85 (0.70-1.02) .09

At 6 wk postpartum 115 9.61 (8.04-11.49) 131 10.88 (9.19-12.87) 0.88 (0.69-1.13) .33 0.87 (0.68-1.10) .24

At 6 mo postpartum 117 9.74 (8.17-11.60) 138 11.50 (9.78-13.51) 0.85 (0.67-1.08) .17 0.83 (0.66-1.05) .11

EPDS score ⬎12 for women 63 20.94 (17.37-25.24) 69 24.15 (20.36-28.66) 0.87 (0.67-1.12) .27 0.87 (0.68-1.12) .28

with previous or current

depression at trial entry c

At 6 wk postpartum 63 21.16 (16.91-26.48) 64 22.11 (17.70-27.62) 0.96 (0.70-1.31) .79 0.96 (0.71-1.30) .79

At 6 mo postpartum 62 20.83 (16.65-26.07) 75 26.15 (21.42-31.92) 0.80 (0.59-1.08) .14 0.81 (0.60-1.08) .15

New medical diagnosis 47 3.39 (2.76-4.15) 61 4.12 (3.39-5.01) 0.82 (0.64-1.06) .13 0.80 (0.62-1.02) .07

of depression during the

study period

New or existing diagnosis 59 4.62 (3.81-5.62) 64 4.74 (3.89-5.77) 0.98 (0.75-1.26) .85 0.93 (0.73-1.18) .55

of depression requiring

treatment during the

study period

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; DHA, docosahexaenoic acid; RR, relative risk.

a All data are based on analysis of 50 imputed datasets. For DHA and control groups, data are number at a particular time point or averaged across time points and % (95% CI)

estimated by unadjusted model. P values for treatment ⫻ time interactions were .77 (unadjusted and adjusted) for EPDS score of more than 12 for all women; .30 (unadjusted)

and .32 (adjusted) for EPDS score of more than 12 for women with previous or current depression at trial entry; .08 (unadjusted and adjusted) for new medical diagnosis of

depression during the study period; and .48 (unadjusted and adjusted) for new or existing diagnosis of depression requiring treatment during the study period.

b Adjusted for center, parity, Maternal Social Support Index score, age, history of depression, and smoking status.

c Number of mothers included in this subset were 298 for DHA group and 287 for control group.

©2010 American Medical Association. All rights reserved. (Reprinted) JAMA, October 20, 2010—Vol 304, No. 15 1679

Downloaded From: on 03/17/2018

DHA SUPPLEMENTATION DURING PREGNANCY AND MATERNAL DEPRESSION

the fewer very preterm births in the who died of a malignant rhabdoid tu- trials. The DOMInO trial was designed

DHA group. There were 4 fetal/infant mor of the brainstem at 15 months. to assess the benefits and harms of DHA

deaths (0.33%) in the DHA group com- supplementation during pregnancy. We

pared with 12 deaths (1%) in the con- COMMENT intervened with DHA-rich fish oil, which

trol group at 18 months (RR, 0.33; 95% Recommendations to increase DHA in- provided a DHA dose that was high

CI, 0.11-1.03; P = .06). All deaths oc- take during pregnancy are being imple- enough to cover all the recommenda-

curred during the perinatal period, ex- mented in the absence of well-de- tions for DHA intake in pregnancy,4 and

cept for 1 infant from the DHA group signed, large-scale randomized controlled included women with comparable demo-

Table 3. Outcomes From the Bayley Scales of Infant and Toddler Development, Third Edition a

DHA Supplement Control Supplement

(n = 351) (n = 375) Unadjusted Adjusted b

Weighted Weighted P P

Mean (SD) Mean (SD) Effect (95% CI) Value Effect (95% CI) Value

Cognitive Standardized 101.81 (11.05) 101.75 (12.56) 0.05 (−1.32 to 1.43) .94 0.01 (−1.36 to 1.37) .99

Score

Female 103.00 (10.24) 103.78 (11.31) −0.78 (−2.56 to 1.00) .39 −0.83 (−2.62 to 0.96) .36

Male 100.62 (11.69) 99.81 (13.38) 0.81 (−1.26 to 2.88) .44 0.83 (−1.22 to 2.88) .43

Language Standardized 96.47 (13.63) 97.94 (15.33) −1.47 (−3.16 to 0.23) .09 −1.42 (−3.07 to 0.22) .09

Score

Female 98.73 (13.66) 103.24 (12.99) −4.51 (−6.72 to −2.30) ⬍.001 −4.43 (−6.65 to −2.20) ⬍.001

Male 94.23 (13.23) 92.86 (15.70) 1.37 (−1.04 to 3.78) .26 1.55 (−0.84 to 3.93) .20

Motor Standardized 102.63 (10.17) 102.57 (11.50) 0.06 (−1.19 to 1.30) .93 0.08 (−1.15 to 1.31) .90

Score

Female 104.29 (9.34) 104.94 (10.54) −0.65 (−2.25 to 0.96) .43 −0.69 (−2.31 to 0.93) .40

Male 100.97 (10.68) 100.30 (11.93) 0.67 (−1.18 to 2.53) .48 0.85 (−1.00 to 2.70) .37

Social-Emotional 106.32 (17.49) 107.27 (17.66) −0.95 (−2.99 to 1.08) .36 −0.97 (−3.00 to 1.06) .35

Standardized Score

Female 108.44 (17.05) 110.77 (17.18) −2.32 (−5.10 to 0.45) .10 −2.07 (−4.82 to 0.69) .14

Male 104.21 (17.69) 103.92 (17.47) 0.29 (−2.65 to 3.23) .85 0.11 (−2.85 to 3.08) .94

Adaptive Behavior 99.17 (13.95) 100.75 (14.45) −1.58 (−3.28 to 0.11) .07 −1.53 (−3.18 to 0.13) .07

Standardized Score

Female 101.27 (14.37) 104.88 (13.59) −3.60 (−5.98 to −1.22) .003 −3.55 (−5.89 to −1.20) .003

Male 97.08 (13.20) 96.81 (14.15) 0.27 (−2.01 to 2.56) .81 0.47 (−1.83 to 2.77) .69

Weighted Weighted P P

No. c % (95% CI) No. c % (95% CI) Effect (95% CI) Value Effect (95% CI) Value

Cognitive Standardized 11 2.71 (1.59 to 4.62) 24 6.64 (4.82 to 9.13) 0.41 (0.22 to 0.76) .004 0.41 (0.22 to 0.78) .007

Score ⬍85

Female 3 1.94 (0.82 to 4.59) 6 3.53 (1.90 to 6.57) 0.55 (0.19 to 1.58) .26 0.52 (0.18 to 1.54) .24

Male 7 3.45 (1.78 to 6.69) 17 9.60 (6.63 to 13.88) 0.36 (0.17 to 0.76) .008 0.37 (0.17 to 0.79) .01

Cognitive Standardized 22 5.97 (4.27 to 8.36) 28 7.35 (5.49 to 9.82) 0.81 (0.52 to 1.26) .36 0.80 (0.52 to 1.25) .33

Score ⬎115

Female 14 6.84 (4.42 to 10.59) 14 7.07 (4.67 to 10.72) 0.97 (0.53 to 1.77) .91 0.92 (0.51 to 1.67) .79

Male 8 5.09 (3.00 to 8.64) 14 7.60 (5.07 to 11.38) 0.67 (0.35 to 1.30) .24 0.69 (0.36 to 1.34) .27

Language Standardized 62 17.99 (15.00 to 21.57) 65 17.40 (14.60 to 20.73) 1.03 (0.80 to 1.34) .80 0.97 (0.75 to 1.26) .82

Score ⬍85

Female 20 12.76 (9.21 to 17.68) 14 7.00 (4.60 to 10.63) 1.82 (1.07 to 3.11) .03 1.81 (1.06 to 3.08) .03

Male 41 23.17 (18.60 to 28.86) 52 27.35 (22.65 to 33.04) 0.85 (0.63 to 1.14) .27 0.80 (0.59 to 1.08) .14

Language Standardized 30 8.79 (6.66 to 11.61) 39 10.47 (8.28 to 13.22) 0.84 (0.58 to 1.21) .35 0.83 (0.58 to 1.19) .30

Score ⬎115

Female 19 10.78 (7.64 to 15.21) 27 15.08 (11.47 to 19.83) 0.71 (0.46 to 1.11) .13 0.72 (0.46 to 1.11) .14

Male 11 6.80 (4.25 to 10.88) 12 6.03 (3.91 to 9.32) 1.13 (0.60 to 2.13) .71 1.11 (0.59 to 2.10) .74

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; DHA, docosahexaenoic acid.

a Data are expressed as weighted mean (weighted SD) with effect being difference in means or unweighted number and weighted % (95% CI) with effect being relative risk. All values are

based on analysis of 50 imputed datasets. For treatment ⫻ sex interactions, P=.26 (unadjusted) and P=.23 (adjusted) for cognitive score; P⬍.001 (unadjusted and adjusted) for

language score; P=.29 (unadjusted) and P=.22 (adjusted) for motor score; P=.21 (unadjusted) and P=.29 (adjusted) for social-emotional score; P=.02 (unadjusted and adjusted) for

adaptive behavior; P=.52 (unadjusted) and P=.59 (adjusted) for cognitive score of less than 85; P=.42 (unadjusted) and P=.53 (adjusted) for cognitive score of more than 115; P=.01

(unadjusted) and P=.009 (adjusted) for language score of less than 85; P=.25 (unadjusted) and P=.26 (adjusted) for language score of more than 115.

b Adjusted for center, parity, sex, mother’s secondary education, mother’s further education, and smoking status.

c Unweighted.

1680 JAMA, October 20, 2010—Vol 304, No. 15 (Reprinted) ©2010 American Medical Association. All rights reserved.

Downloaded From: on 03/17/2018

DHA SUPPLEMENTATION DURING PREGNANCY AND MATERNAL DEPRESSION

Table 4. Secondary Clinical Outcomes a

Unadjusted Adjusted b

DHA Supplement Control Supplement P P

Outcomes (n = 1197) (n = 1202) Effect (95% CI) Value Effect (95% CI) Value

Duration of gestation, median (IQR), d 282 (275-288) 281 (275-287) NA .05 c NA .05 c

Birth ⬍37 wk gestation 67 (5.60) 88 (7.34) 0.76 (0.56 to 1.04) .09 0.77 (0.56 to 1.05) .09

Birth ⬍34 wk gestation 13 (1.09) 27 (2.25) 0.49 (0.25 to 0.94) .03 0.49 (0.25 to 0.94) .03

Postterm induction or postterm 211 (17.59) 165 (13.72) 1.28 (1.06 to 1.55) .01 1.28 (1.06 to 1.54) .01

prelabor cesarean delivery

Birth by cesarean delivery 326 (27.25) 350 (29.14) 0.94 (0.82 to 1.06) .31 0.94 (0.83 to 1.07) .34

Log blood loss at birth, mean (SD) 5.64 (0.59) 5.65 (0.60) −0.01 (−0.06 to 0.04) .79 −0.01 (−0.05 to 0.04) .79

Postpartum hemorrhage 57 (4.72) 64 (5.28) 0.89 (0.62 to 1.28) .54 0.90 (0.63 to 1.28) .55

Birth weight, mean (SD), g 3475 (564) 3407 (576) 69 (23 to 115) .003 68 (23 to 114) .003

Birth weight z score, mean (SD) 0.28 (1.06) 0.22 (1.02) 0.06 (−0.02 to 0.15) .16 0.06 (−0.02 to 0.14) .16

Birth weight ⬍2500 g 41 (3.41) 63 (5.27) 0.65 (0.44 to 0.95) .03 0.65 (0.44 to 0.96) .03

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; DHA, docosahexaenoic acid; IQR, interquartile range; NA, not applicable.

a Data are expressed as No. (%) with effect being relative risk or mean (SD) with effect being difference in means, unless otherwise indicated. All values are based on analysis of 50 imputed

datasets.

b Adjusted for center and parity (birth ⬍34 weeks’ gestation adjusted for parity only).

c Based on a stratified log-rank test.

graphic characteristics to Australian

Table 5. Serious Adverse Events at 18 Months Postpartum

women giving birth in 2006-2007, al-

No. (%) Unadjusted

though our study seemed to include

more women who smoked at trial en- DHA Supplement Control Supplement P

try.23,24 We observed nonsignificant rela- Serious Adverse Events (n = 1197) (n = 1202) RR (95% CI) Value

tive reductions in the percentage of Any maternal 2 (0.17) 2 (0.17) NA ⬎.99 a

Any level III antenatal 2 (0.17) 2 (0.17) NA ⬎.99 a

women with high levels of depressive hospitalization

symptoms overall and in the subgroup Death 0 0 NA NA

of women with previous medically di- Any infant 36 (3.01) 54 (4.49) 0.67 (0.44-1.01) .06

agnosed depression. Further work is re- Any admission to neonatal 21 (1.75) 37 (3.08) 0.57 (0.34-0.97) .04

quired to establish the effectiveness of intensive care

DHA intervention for women with a his- Major congenital 15 (1.25) 11 (0.92) 1.37 (0.63-2.97) .43

abnormality

tory of depression because of the higher

Death 4 (0.33) 12 (1.00) 0.33 (0.11-1.03) .06

prevalence of depressive symptoms and

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; DHA, docosahexaenoic acid; NA, not applicable; RR, relative risk.

the potentially larger absolute effect size, a Based on Fisher exact test.

especially at 6 months.

A limitation of the depression as-

pect of our study is that we did not expected rate of depressive symptoms had lower language scores and were

verify high EPDS scores with a clinical in the control group had a major affect more likely to have delayed language

diagnosis of depression as part of the on the power of the study. Based on the development than girls from the con-

trial protocol. It is possible that the observed control rate of 11%, a post hoc trol group. There was also a group ⫻

lower than expected rate of women with power estimate indicates that we had sex interaction in our DINO (DHA for

high levels of depressive symptoms in sufficient power to detect a clinically the Improvement of Neurodevelop-

the control group is explained by the meaningful 4% reduction in depres- mental Outcome of Preterm Infants)

Hawthorn effect, in which simply par- sive symptoms between DHA treat- trial19 in which preterm infants were

ticipating in a trial with increased con- ment and control if it existed. treated with higher-dose DHA during

tact with researchers helped to pre- We also found no effect of DHA treat- the equivalent period ex-utero, but the

vent depressive symptoms.25 A study ment during pregnancy on early child- response of the girls was directly op-

comparing regular dietary advice and hood cognitive and language scores, al- posite. This inconsistency may be due

blood glucose monitoring with no in- though in secondary analyses 2 to chance or may highlight the sensi-

tervention in gestational diabetes also contrasting effects were noted. Fewer tivity of girls to DHA intervention. The

reported a reduction in women with children in the DHA-treated group had change in the version of the BSID scales

high levels of depressive symptoms delayed cognitive development com- should be noted. Most previous stud-

from 17% to 8%.26 Nevertheless, the im- pared with the control group, and girls ies, including the DINO trial,19 have

portant issue is whether the lower than exposed to higher-dose DHA in utero used BSID-II (Second Edition), in which

©2010 American Medical Association. All rights reserved. (Reprinted) JAMA, October 20, 2010—Vol 304, No. 15 1681

Downloaded From: on 03/17/2018

DHA SUPPLEMENTATION DURING PREGNANCY AND MATERNAL DEPRESSION

the Mental Development Index com- unlikely that women significantly in- termine whether there are specific ben-

bines elements that are in the Cogni- creased their intake of fish and sea- efits of DHA supplementation for

tive and Language Composite Scores of food or DHA supplemented foods be- women with a previous history of de-

the BSID-III. Cognitive outcome at later cause of participation in the DOMInO pression and for women at risk of pre-

ages will be important to determine trial. The ratio of DHA to EPA in peri- term birth.

whether any positive or negative ef- natal supplements has been controver- Author Contributions: Drs Makrides and Gibson had

fects of DHA supplementation re- sial. Although there is general agree- full access to all of the data in the study and take re-

sponsibility for the integrity of the data and the ac-

main, especially in the domain of lan- ment that supplements containing more curacy of the data analysis.

guage development. DHA than EPA are preferred for child- Study concept and design: Makrides, Gibson, McPhee,

Previous studies of marine oil inter- hood developmental outcomes, au- Yelland, Quinlivan, Ryan.

Acquisition of data: Makrides, Gibson, McPhee, Quin-

ventions designed to prevent preterm thors are divided with regard to depres- livan.

birth used doses of n-3 LCPUFA that sion outcomes and some strongly argue Analysis and interpretation of data: Makrides, Gibson,

McPhee, Yelland, Quinlivan, Ryan.

favored EPA over DHA and were 3 in favor of EPA. However, there is little Drafting of the manuscript: Makrides, Gibson.

times higher than the DOMInO dose. direct evidence of biological plausibil- Critical revision of the manuscript for important in-

tellectual content: Makrides, Gibson, McPhee, Yelland,

The focus on EPA over DHA was tar- ity. Eicosapentaenoic acid does not ac- Quinlivan, Ryan.

geted to alter prostaglandin balance and cumulate in the brain and most ani- Statistical analysis: Makrides, Yelland, Ryan.

delay the initiation of labor. Consis- mal studies investigating n-3 fatty acid Obtained funding: Makrides, Gibson, McPhee,

Quinlivan.

tent with the relevant systematic re- deficient diets implicate DHA in the Administrative, technical, or material support:

view, we demonstrated that supple- function of dopaminergic and seroton- Makrides, Gibson, McPhee, Quinlivan, Ryan.

Study supervision: Makrides, Gibson, McPhee, Yel-

mentation with predominantly DHA in ergic pathways.30 Furthermore, earlier land, Quinlivan, Ryan.

pregnancy caused a small to modest in- trials suggesting EPA was more effec- Financial Disclosures: Dr Makrides reports serving on

scientific advisory boards for Nestle, Fonterra, and

crease in the duration of gestation, al- tive than DHA in reducing depression Nutricia. Dr Gibson reports serving on scientific advi-

though a precise estimate of effect size were plagued by methodological limi- sory boards for Nestle and Fonterra. Associated hono-

raria for Drs Makrides and Gibson are paid to their in-

has been difficult to determine be- tations and do not provide results with stitutions to support conference travel and continuing

cause of obstetric interventions to de- a high level of confidence.5 With this education for postgraduate students and early career

liver infants to minimize the risks as- reasoning, the supplement used in the researchers. No other authors reported any financial

disclosures.

sociated with postterm birth.27,28 Not DOMInO trial contained 800 mg/d of Funding/Support: This work was supported by

surprisingly, the effect of DHA treat- DHA and 100 mg/d of EPA. grant 349301 from the Australian National Health

and Medical Research Council. Treatment and pla-

ment on gestation length was most no- Current recommendations suggest cebo capsules were donated by Efamol, England.

table at the extremes. In the DHA group, that pregnant women increase their di- Infrastructure support was also provided by the

Women’s and Children’s Health Research Institute,

significantly fewer infants were born etary DHA to improve their health out- The University of Adelaide, Women’s and Chil-

less than 34 weeks’ gestation but sig- comes as well as those of their chil- dren’s Hospital Adelaide, Flinders Medical Centre

nificantly more women were induced dren.4,10 Such recommendations are Adelaide, Sunshine Hospital Melbourne, University

of Notre Dame Australia, University of Wollon-

or had cesarean sections because they increasingly being adopted with women gong, Campbelltown Hospital Sydney, Royal Bris-

were postterm. The clinical signifi- taking prenatal supplements with DHA. bane and Women’s Hospital, and University of

Queensland.

cance of these findings is difficult to bal- In fact, 64% of ineligible women Role of the Sponsor: The funding body and the com-

ance, although the reduction in pre- screened for the DOMInO trial were ex- pany donating the capsules had no role in the study

design or conduct; in the data collection, manage-

term birth at less than 34 weeks’ cluded because they were already tak- ment, analysis, or interpretation; or in the prepara-

gestation was also associated with fewer ing a prenatal supplement that con- tion, review, or approval of the manuscript.

Additional Authors/Members of the DOMInO In-

low birth weight infants and fewer ad- tained DHA. However, the results of the vestigative Team: Lex W. Doyle, MBBS, PhD, Peter

missions to neonatal intensive care in DOMInO trial do not support routine Anderson, MPsych, PhD, Neonatal Services, Royal

the DHA group. DHA supplementation for pregnant Women’s Hospital and University of Melbourne, Aus-

tralia; Paul L. Else, PhD, Barbara J. Meyer, PhD, School

Our trial could be criticized be- women to reduce depressive symp- of Health Sciences, University of Wollongong and

cause we did not assess dietary intake toms or to improve cognitive or lan- Campbelltown Hospital, NSW, Australia; Paul Colditz,

MBBS, PhD, Margo Pritchard, RN, PhD, Perinatal Re-

of n-3 LCPUFA and because of the guage outcomes in early childhood. Our search Centre and Neonatal Unit, Royal Brisbane and

choice of supplement. Women in Aus- results are at odds with the results of Women’s Hospital and University of Queensland, Aus-

tralia; Shao Zhou, BND, PhD, Carmel T. Collins, RM,

tralia are known to have low dietary in- some large-scale epidemiological stud- RN, PhD, Zoe Gulpers, BSc, MPsych, Suzanne

takes of n-3 LCPUFA13; this was evi- ies. 1 - 3 It may be that even well- McCusker, BSc, Nicola Naccarella, MND, Karen Best,

denced by the fact the median plasma conducted epidemiological studies RM, RN, Helen Loudis, BSc, Women’s and Children’s

Health Research Institute, Adelaide SA, Australia;

phospholipid DHA concentration in overestimate effect size and do not ad- Amanda Anderson, PhD, Elizabeth Griffith, BA, Grad

cord blood of the DOMInO control equately deal with residual confound- Dip Pub Health, Data Management and Analysis Cen-

tre, School of Population Health and Clinical Prac-

group was virtually identical to the con- ing, or that other nutrients in fish and tice, The University of Adelaide, Adelaide, Australia.

centration observed in a cohort of seafood, beyond DHA, contribute to the Steering Committee: Maria Makrides, BSc, BND, PhD

(chair), Robert A. Gibson, BSc, PhD (deputy chair),

Dutch pregnant women with biochemi- observations from epidemiological stud- Andrew J. McPhee, MBBS, Lisa Yelland, BSc, Julie

cal DHA insufficiency.29 It is therefore ies. Further studies are required to de- Quinlivan, MBBS, PhD, Philip Ryan, MBBS, BSc.

1682 JAMA, October 20, 2010—Vol 304, No. 15 (Reprinted) ©2010 American Medical Association. All rights reserved.

Downloaded From: on 03/17/2018

DHA SUPPLEMENTATION DURING PREGNANCY AND MATERNAL DEPRESSION

Serious Adverse Event Committee: Elinor Atkinson, efits infant visual acuity at four but not six months of birth: results of an Australian population based survey.

MBBS, FRANZCOG (chair), Department of Obstet- age. Lipids. 2007;42(2):117-122. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 1998;105(2):156-161.

rics and Gynaecology, Flinders Medical Centre, Ad- 9. Malcolm CA, McCulloch DL, Montgomery C, 19. Makrides M, Gibson RA, McPhee AJ, et al. Neu-

elaide, Australia; Nick Manton, MBBS, FRCPA, His- Shepherd A, Weaver LT. Maternal docosahexaenoic rodevelopmental outcomes of preterm infants fed high-

topathology, Women’s and Children’s Hospital, acid supplementation during pregnancy and visual dose docosahexaenoic acid: a randomized controlled

Adelaide, Australia; Chad Andersen, MBBS, FRACP, evoked potential development in term infants: a trial. JAMA. 2009;301(2):175-182.

Neonatal Medicine, Women’s and Children’s Hospi- double blind, prospective, randomised trial. 20. Carpenter DO. Effects of metals on the nervous

tal, Adelaide, Australia. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed. 2003;88(5): system of humans and animals. Int J Occup Med En-

Online-Only Material: eTables 1 and 2 are available F383-F390. viron Health. 2001;14(3):209-218.

at http://www.jama.com. 10. Koletzko B, Cetin I, Brenna JT; Perinatal Lipid In- 21. Walter T, De Andraca I, Chadud P, Perales CG.

Additional Contributions: We thank the families who take Working Group; Child Health Foundation; Dia- Iron deficiency anemia: adverse effects on infant psy-

participated; the medical, nursing, and research staff betic Pregnancy Study Group; European Association chomotor development. Pediatrics. 1989;84(1):

in each participating center; the staff of the Child Nu- of Perinatal Medicine; European Association of Peri- 7-17.

trition Research Centre; and the staff of the Data Man- natal Medicine; European Society for Clinical Nutri- 22. Anderson PJ, Doyle LW. Cognitive and educa-

agement and Analysis Centre, University of Ad- tion and Metabolism; European Society for Paediat- tional deficits in children born extremely preterm. Se-

elaide, Adelaide, Australia. ric Gastroenterology, Hepatology and Nutrition, min Perinatol. 2008;32(1):51-58.

Committee on Nutrition; International Federation of 23. Chan A, Scott J, Nguyen A-M, Sage L. Preg-

Placenta Associations; International Society for the nancy Outcome in South Australia 2007. Adelaide:

REFERENCES Study of Fatty Acids and Lipids. Dietary fat intakes for Pregnancy Outcome Unit, South Australian Depart-

pregnant and lactating women. Br J Nutr. 2007; ment of Health; 2008.

1. Golding J, Steer C, Emmett P, Davis JM, Hibbeln 98(5):873-877. 24. Chan A, Scott J, Nguyen A-M, Sage L. Preg-

JR. High levels of depressive symptoms in pregnancy 11. Pascoe JM, Ialongo NS, Horn WF, Reinhart MA, nancy Outcome in South Australia 2006. Adelaide:

with low omega-3 fatty acid intake from fish. Perradatto D. The reliability and validity of the ma- Pregnancy Outcome Unit, South Australian Depart-

Epidemiology. 2009;20(4):598-603. ternal social support index. Fam Med. 1988;20 ment of Health; 2007.

2. Hibbeln JR, Davis JM, Steer C, et al. Maternal sea- (4):271-276. 25. Braunholtz DA, Edwards SJL, Lilford RJ. Are ran-

food consumption in pregnancy and neurodevelop- 12. Hibbeln JR, Davis JM. Considerations regarding domized clinical trials good for us (in the short term)?

mental outcomes in childhood (ALSPAC study): an ob- neuropsychiatric nutritional requirements for intakes evidence for a “trial effect.” J Clin Epidemiol. 2001;

servational cohort study. Lancet. 2007;369(9561): of omega-3 highly unsaturated fatty acids. Prosta- 54(3):217-224.

578-585. glandins Leukot Essent Fatty Acids. 2009;81(2-3): 26. Crowther CA, Hiller JE, Moss JR, McPhee AJ, Jeffries

3. Oken E, Radesky JS, Wright RO, et al. Maternal 179-186. WS, Robinson JS; Australian Carbohydrate Intoler-

fish intake during pregnancy, blood mercury levels, 13. Meyer BJ, Mann NJ, Lewis JL, Milligan GC, Sinclair ance Study in Pregnant Women (ACHOIS) Trial Group.

and child cognition at age 3 years in a US cohort. Am AJ, Howe PR. Dietary intakes and food sources of Effect of treatment of gestational diabetes mellitus on

J Epidemiol. 2008;167(10):1171-1181. omega-6 and omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids. pregnancy outcomes. N Engl J Med. 2005;352

4. Brenna JT, Lapillonne A. Background paper on Lipids. 2003;38(4):391-398. (24):2477-2486.

fat and fatty acid requirements during pregnancy 14. Smithers LG, Gibson RA, McPhee A, Makrides 27. Makrides M, Duley L, Olsen SF. Marine oil, and

and lactation. Ann Nutr Metab. 2009;55(1-3): M. Effect of two doses of docosahexaenoic acid other prostaglandin precursor, supplementation for

97-122. (DHA) in the diet of preterm infants on infant fatty pregnancy uncomplicated by pre-eclampsia or intra-

5. Ramakrishnan U, Imhoff-Kunsch B, DiGirolamo AM. acid status: results from the DINO trial. Prostagland- uterine growth restriction. Cochrane Database Syst Rev.

Role of docosahexaenoic acid in maternal and child ins Leukot Essent Fatty Acids. 2008;79(3-5):141- 2006;3(issue 3):CD003402. doi:10.1002/14651858

mental health. Am J Clin Nutr. 2009;89(3):958S- 146. .CD003402.pub2.

962S. 15. Boyce P, Stubbs J, Todd A. The Edinburgh Post- 28. Olsen SF, Secher NJ, Tabor A, Weber T, Walker

6. Helland IB, Smith L, Saarem K, Saugstad OD, Drevon natal Depression Scale: validation for an Australian JJ, Gluud C; Fish Oil Trials In Pregnancy (FOTIP) Team.

CA. Maternal supplementation with very-long-chain sample. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 1993;27(3):472- Randomised clinical trials of fish oil supplementation

n-3 fatty acids during pregnancy and lactation aug- 476. in high risk pregnancies. BJOG. 2000;107(3):382-

ments children’s IQ at 4 years of age. Pediatrics. 2003; 16. Cox JL, Holden JM, Sagovsky R. Detection of post- 395.

111(1):e39-e44. natal depression. Development of the 10-item Edin- 29. Al MD, van Houwelingen AC, Kester AD, Hasaart

7. Dunstan JA, Simmer K, Dixon G, Prescott SL. Cog- burgh Postnatal Depression Scale. Br J Psychiatry. 1987; TH, de Jong AE, Hornstra G. Maternal essential fatty

nitive assessment of children at age 2(1/2) years af- 150(Jun):782-786. acid patterns during normal pregnancy and their re-

ter maternal fish oil supplementation in pregnancy: a 17. Murray L, Carothers AD. The validation of the Ed- lationship to the neonatal essential fatty acid status.

randomised controlled trial. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neo- inburgh Post-natal Depression Scale on a community Br J Nutr. 1995;74(1):55-68.

natal Ed. 2008;93(1):F45-F50. sample. Br J Psychiatry. 1990;157(Aug):288- 30. Innis SM. Perinatal biochemistry and physiology

8. Judge MP, Harel O, Lammi-Keefe CJ. A docosa- 290. of long-chain polyunsaturated fatty acids. J Pediatr.

hexaenoic acid-functional food during pregnancy ben- 18. Brown S, Lumley J. Maternal health after child- 2003;143(4)(suppl):S1-S8.

©2010 American Medical Association. All rights reserved. (Reprinted) JAMA, October 20, 2010—Vol 304, No. 15 1683

Downloaded From: on 03/17/2018

You might also like

- Breastfeeding, Cognitive and Noncognitive Development in Early Childhood: A Population StudyDocument11 pagesBreastfeeding, Cognitive and Noncognitive Development in Early Childhood: A Population StudyNick DiMarcoNo ratings yet

- RP Diet Template Quick Tips: Welcome To The TemplatesDocument9 pagesRP Diet Template Quick Tips: Welcome To The TemplatesRom Rom100% (3)

- Healthy Kids, Happy Moms: 7 Steps to Heal and Prevent Common Childhood IllnessesFrom EverandHealthy Kids, Happy Moms: 7 Steps to Heal and Prevent Common Childhood IllnessesNo ratings yet

- Volume 11 CompleteDocument143 pagesVolume 11 CompletePhúcNo ratings yet

- Bi-Phasic Diet ProtocolDocument10 pagesBi-Phasic Diet ProtocolSigit Prastowo0% (1)

- Nejm ArticleDocument10 pagesNejm Articlemadimadi11No ratings yet

- Carlson, 2013 DHA Supplementation and Pregnancy OutcomesDocument8 pagesCarlson, 2013 DHA Supplementation and Pregnancy OutcomesDaniela Patricia Alvarez AravenaNo ratings yet

- NutrientsDocument11 pagesNutrientsTri WidodoNo ratings yet

- Essential n-3 Fatty Acids in Pregnant Women and Early Visual Acuity Maturation in Term InfantsDocument15 pagesEssential n-3 Fatty Acids in Pregnant Women and Early Visual Acuity Maturation in Term InfantsRia AchmadNo ratings yet

- Essential n-3 Fatty Acids in Pregnant Women and Early Visual Acuity Maturation in Term InfantsDocument15 pagesEssential n-3 Fatty Acids in Pregnant Women and Early Visual Acuity Maturation in Term InfantsRia AchmadNo ratings yet

- Nicu 1Document7 pagesNicu 1PPDS ANAK FK USUNo ratings yet

- Campoy, 2012 Omega 3 Fatty Acids On Child Growth, Visual Acuity and NeurodevelopmentDocument22 pagesCampoy, 2012 Omega 3 Fatty Acids On Child Growth, Visual Acuity and NeurodevelopmentDaniela Patricia Alvarez AravenaNo ratings yet

- 2016 (ANZ DOHaD) Scientific MeetingDocument1 page2016 (ANZ DOHaD) Scientific MeetingNguyễn Tiến HồngNo ratings yet

- Docosahexaenoic Acid (DHA) : MonographDocument9 pagesDocosahexaenoic Acid (DHA) : MonographBen ClarkeNo ratings yet

- Perbandingan Kadar Brain Derived Neurotrophic Factor (BDNF) Serum Tali Pusat Bayi Baru Lahir Antara Ibu Hamil Yang Mendapat Dengan Tidak Mendapat Docosahexaenoic Acid (DHA)Document6 pagesPerbandingan Kadar Brain Derived Neurotrophic Factor (BDNF) Serum Tali Pusat Bayi Baru Lahir Antara Ibu Hamil Yang Mendapat Dengan Tidak Mendapat Docosahexaenoic Acid (DHA)sabisiNo ratings yet

- Dietary Docosahexaenoic Acid Supplementation in Children With AutismDocument8 pagesDietary Docosahexaenoic Acid Supplementation in Children With AutismAnonymous 18GsyXbNo ratings yet

- Algae Omega or DhaDocument6 pagesAlgae Omega or Dharudresh gcNo ratings yet

- Poster Session: Wellness and Public Health: Tuesday, October 2Document1 pagePoster Session: Wellness and Public Health: Tuesday, October 2Rio Michelle CorralesNo ratings yet

- Maternal High-Dose DHA Supplementation and Neurodevelopment at 18-22 Months of Preterm ChildrenDocument10 pagesMaternal High-Dose DHA Supplementation and Neurodevelopment at 18-22 Months of Preterm ChildrenEduardo Rios DuboisNo ratings yet

- Eicosapentaenoic and Docosahexaenoic Acids, Cognition, and Behavior inDocument8 pagesEicosapentaenoic and Docosahexaenoic Acids, Cognition, and Behavior inVũ Hoàng MaiNo ratings yet

- 2023 - Suplementación de Ácido Araquidónico y Docosaexanoico y Resultados Respiratorios en Infantes @wendelDocument7 pages2023 - Suplementación de Ácido Araquidónico y Docosaexanoico y Resultados Respiratorios en Infantes @wendelJorge Toshio Yazawa ChaconNo ratings yet

- Randomized Controlled Trial of A Primary Care-Based Child Obesity Prevention Intervention On Infant Feeding PracticesDocument9 pagesRandomized Controlled Trial of A Primary Care-Based Child Obesity Prevention Intervention On Infant Feeding PracticesSardono WidinugrohoNo ratings yet

- Effect of A Baby-Led Approach To Complementary Feeding On Infant Growth and Overweight A Randomized Clinical TrialDocument9 pagesEffect of A Baby-Led Approach To Complementary Feeding On Infant Growth and Overweight A Randomized Clinical TrialMATHIAS NORAMBUENA VIDELANo ratings yet

- Nresearch PaperDocument14 pagesNresearch Paperapi-400982160No ratings yet

- Grzeskowiak Et al-2016-BJOG: An International Journal of Obstetrics & GynaecologyDocument10 pagesGrzeskowiak Et al-2016-BJOG: An International Journal of Obstetrics & GynaecologyPrima Hari PratamaNo ratings yet

- Jurnal PerinaDocument7 pagesJurnal PerinaBhismo PasetyoNo ratings yet

- Depresion en El EmbarazoDocument9 pagesDepresion en El EmbarazoVICTOR CLAUDIO ARENAS OCAMPONo ratings yet

- 1 s2.0 S1875957222000195 MainDocument7 pages1 s2.0 S1875957222000195 MainElenaNo ratings yet

- Naps1 Ob PaperDocument15 pagesNaps1 Ob Paperapi-324081700No ratings yet

- Acizi Grasi CarinaDocument7 pagesAcizi Grasi CarinaBîcă OvidiuNo ratings yet

- Varuzza Et Al-2019-Environmental ToxicologyDocument10 pagesVaruzza Et Al-2019-Environmental ToxicologyCharles santos da costaNo ratings yet

- Comparison of Growth Pattern in Neonates On BreastDocument7 pagesComparison of Growth Pattern in Neonates On BreastOman SantosoNo ratings yet

- Nresearch PaperDocument13 pagesNresearch Paperapi-399638162No ratings yet

- Pi Is 0002937812001317Document7 pagesPi Is 0002937812001317harold.atmajaNo ratings yet

- Ahmed 2010Document7 pagesAhmed 2010patricia brucellariaNo ratings yet

- DHA Supplementation Improved Both Memory and Reaction Time in Healthy Young Adults: A Randomized Controlled TrialDocument10 pagesDHA Supplementation Improved Both Memory and Reaction Time in Healthy Young Adults: A Randomized Controlled TrialtrealNo ratings yet

- ABSTRACT AED Paola BarrigueteDocument5 pagesABSTRACT AED Paola BarrigueteDaniNo ratings yet

- Duration of Breastfeeding and Developmental Milestones During The Latter Half of InfancyDocument6 pagesDuration of Breastfeeding and Developmental Milestones During The Latter Half of InfancyErwin SetiawanNo ratings yet

- Pediatric JournalDocument9 pagesPediatric JournalSatrianiNo ratings yet

- Docosahexaenoic Acid Administered in The Acute Phase Protects Nutritional Status of Septic Neonates - Nutrition 2006Document7 pagesDocosahexaenoic Acid Administered in The Acute Phase Protects Nutritional Status of Septic Neonates - Nutrition 2006Talia Porras SuarezNo ratings yet

- International Breastfeeding JournalDocument7 pagesInternational Breastfeeding Journalastuti susantiNo ratings yet

- Pi Is 0002937813005139Document5 pagesPi Is 0002937813005139fenskaNo ratings yet

- Improving The Neurodev TAYANGAN FINAL SETYORINIDocument41 pagesImproving The Neurodev TAYANGAN FINAL SETYORINIFeni RiandariNo ratings yet

- Oral Plenary Session I: Results: ResultsDocument2 pagesOral Plenary Session I: Results: ResultsfujimeisterNo ratings yet

- Obsos 8Document9 pagesObsos 8Depri AndreansyaNo ratings yet

- Attention Among Very Low Birth Weight Infants Following Early Supplementation With Docosahexaenoic and Arachidonic AcidDocument6 pagesAttention Among Very Low Birth Weight Infants Following Early Supplementation With Docosahexaenoic and Arachidonic AcidpleetalNo ratings yet

- Neurodevelopmental Outcomes of Extremely Preterm InfantsDocument10 pagesNeurodevelopmental Outcomes of Extremely Preterm Infantsmarta.sanz.alvarezNo ratings yet

- Omega-3 Fatty Acids EPA and DHA: Health Benefits Throughout LifeDocument7 pagesOmega-3 Fatty Acids EPA and DHA: Health Benefits Throughout LifeDaniel GrigoreNo ratings yet

- Nutritional Neuroscience and Education5Document14 pagesNutritional Neuroscience and Education5Ingrid DíazNo ratings yet

- LCPUFAs AS CONDITIONALLY ESSENTIAL NUTRIENTS FOR VLBW AND LBW INFANTSDocument11 pagesLCPUFAs AS CONDITIONALLY ESSENTIAL NUTRIENTS FOR VLBW AND LBW INFANTSlink0105No ratings yet

- Effect of Maternal Nutrition On Cognitive Function of ChildrenDocument3 pagesEffect of Maternal Nutrition On Cognitive Function of ChildrenMariela PrietoNo ratings yet

- Jurnal ReadingDocument11 pagesJurnal ReadingTasya SylviaNo ratings yet

- Maternal Obesity and High-Fat Diet Program Offspring Metabolic SyndromeDocument13 pagesMaternal Obesity and High-Fat Diet Program Offspring Metabolic SyndromeMuhammad BasriNo ratings yet

- 18381-Article Text-59445-1-10-20171011Document6 pages18381-Article Text-59445-1-10-20171011maxmaxNo ratings yet

- 4396-20802-1-PB (Efek Insulin)Document5 pages4396-20802-1-PB (Efek Insulin)FikriakbarNo ratings yet

- Journal Pone 0133010 PDFDocument14 pagesJournal Pone 0133010 PDFAlejandro CuxumNo ratings yet

- Amamentação e DepressãoDocument8 pagesAmamentação e Depressãolouisepfreitas1010No ratings yet

- Sciencedirect: Sara Dokuhaki, Maryam Heidary, Marzieh AkbarzadehDocument8 pagesSciencedirect: Sara Dokuhaki, Maryam Heidary, Marzieh AkbarzadehRatrika SariNo ratings yet

- Omega3 Treatment of Childhood Depression: A Controlled, Double-Blind Pilot StudyDocument4 pagesOmega3 Treatment of Childhood Depression: A Controlled, Double-Blind Pilot Studyreg ethicalNo ratings yet

- Neurodesarrollo y Reciperacion Despues de Desnutricion AgudaDocument10 pagesNeurodesarrollo y Reciperacion Despues de Desnutricion AgudaJesusMiguelCorneteroMendozaNo ratings yet

- Sdarticle 142 PDFDocument1 pageSdarticle 142 PDFRio Michelle CorralesNo ratings yet

- BreastfeedingDocument13 pagesBreastfeedingSintya AulinaNo ratings yet

- Fil Industries Limited KohinoorDocument39 pagesFil Industries Limited KohinoorimadNo ratings yet

- Starbucks - Case StudyDocument8 pagesStarbucks - Case StudyalookachalooNo ratings yet

- Swami Vivekananda 04 PDFDocument429 pagesSwami Vivekananda 04 PDFdaneshnedaie100% (1)

- The Different Types of Vegetable Cutting Styles: Check Basic Knife Skills VideoDocument3 pagesThe Different Types of Vegetable Cutting Styles: Check Basic Knife Skills VideoJenelyn Mae AbadianoNo ratings yet

- An Introduction To Freshwater Planktons and Their Role in AquacultureDocument8 pagesAn Introduction To Freshwater Planktons and Their Role in AquacultureAlok Kumar JenaNo ratings yet

- Lays Pakistan PDFDocument28 pagesLays Pakistan PDFHanan KhaliqNo ratings yet

- PARNGSSONDocument4 pagesPARNGSSONrain rainyNo ratings yet

- FST 362Document26 pagesFST 362गणेश सुधाकर राउत0% (1)

- Shredded Like Wolverine Workout - Build A Leaner, More Muscular Physique - Muscle & StrengthDocument19 pagesShredded Like Wolverine Workout - Build A Leaner, More Muscular Physique - Muscle & Strengthyoucef mohamedNo ratings yet

- June 27 2014Document48 pagesJune 27 2014fijitimescanadaNo ratings yet

- Unit 2Document12 pagesUnit 2Quỳnh Anh TrầnNo ratings yet

- Product Development & Training CenterDocument8 pagesProduct Development & Training CenterFredisminda DolojanNo ratings yet

- Get Become Change Rise Improve Fall IncreaseDocument21 pagesGet Become Change Rise Improve Fall IncreaseBelinha Ferreira100% (1)

- February 2014 9-12 Lunch MenuDocument1 pageFebruary 2014 9-12 Lunch MenuMedford Public Schools and City of Medford, MANo ratings yet

- Moringa Leaf ExtractDocument70 pagesMoringa Leaf Extractiqba1429No ratings yet

- PG1 ExcelDocument90 pagesPG1 ExceljhtanchongcoNo ratings yet

- Appetizer Summative TestDocument36 pagesAppetizer Summative TestArgelynPadolinaPedernalNo ratings yet

- Beekeeping BasicsDocument12 pagesBeekeeping BasicsEric SNo ratings yet

- Neotropical Rainforest Mammals TalkDocument7 pagesNeotropical Rainforest Mammals TalkMisterJanNo ratings yet

- My New Words Picture Word Book g3-g6Document79 pagesMy New Words Picture Word Book g3-g6Alina Costin100% (2)

- Instrumental and Sensory Evaluation of Textural Changes During Roasting of Cashew KernelsDocument13 pagesInstrumental and Sensory Evaluation of Textural Changes During Roasting of Cashew KernelsTrần Minh ChinhNo ratings yet

- Marketing StrategyDocument3 pagesMarketing StrategyRocky ShahNo ratings yet

- DK2802 ch01Document64 pagesDK2802 ch01Reza JafariNo ratings yet

- A-B Case StudyDocument18 pagesA-B Case StudyNeha PatelNo ratings yet

- 2016 Ontario Hunting Regulations EnglishDocument104 pages2016 Ontario Hunting Regulations EnglishfostbarrNo ratings yet

- Bird Town Trail 10 KDocument21 pagesBird Town Trail 10 KnetbuzzyNo ratings yet

- 1.1.3.8 Lab Analyze A Process 2 PDFDocument2 pages1.1.3.8 Lab Analyze A Process 2 PDFmuah mnasNo ratings yet