Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Virginia G

Virginia G

Uploaded by

sujeeOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Virginia G

Virginia G

Uploaded by

sujeeCopyright:

Available Formats

Guest Post: Law Of The Sea Tribunal Implies A

Principle Of Reasonableness In UNCLOS Article 73

by Craig H. Allen

[Craig H. Allen is the Judson Falknor Professor of Law and of Marine and Environmental Affairs at

the University of Washington.]

On April 14, 2014, the International Tribunal for the Law of the Sea (ITLOS) issued its ruling in

the M/V Virginia G case (Panama/Guinea-Bissau), Case No. 19. The dispute arose out of Guinea-

Bissau’s 2009 arrest of the Panama-flag coastal tanker M/V Virginia G after it was detected bunkering

(i.e., delivering fuel to) several Mauritanian-flag vessels fishing in the Guinea-Bissau exclusive

economic zone (EEZ) without having obtained a bunkering permit. The case presented a number of

issues, including whether the 1982 UN Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS), to which both

states are party, grants a coastal state competency to control bunkering activities by foreign vessels

in its EEZ.

After disposing of objections raised over jurisdiction and admissibility (notwithstanding the parties’

special agreement transferring the case to ITLOS), the decision adds a substantial gloss to several

articles of the UNCLOS, particularly with respect to Article 73 on enforcement of coastal state laws

regarding the conservation and management of living resources in the EEZ. Among other things,

Panama alleged that Guinea-Bissau violated each of the four operative paragraphs of Article 73 in its

boarding, arrest and confiscation of the Virginia G and by seizing and withholding the passports of its

crew for more than 4 months. The tribunal’s holding can be summarized as follows:

UNCLOS SUBJECT HOLDING

ARTICLE

73, para. 1 Right to take necessary enforcement Violated in

measures part

73, para. 2 Prompt release of vessel and crew Not violated

73, para. 3 Prohibition on imprisonment of crew Not violated

73, para. 4 Duty to notify flag state Violated

Those who held out hope that the tribunal would, in this decision, breathe life into the UNCLOS Article

91 requirement that “there must exist a genuine link between the [flag] State and the ship” after the

tribunal ruled in 2012 that Guinea-Bissau’s counterclaim that Panama had violated that requirement

was admissible had those hopes dashed. The tribunal merely reaffirmed its 1999 holding in the

M/V Saiga No. 2 case (see decision, paras. 109-113), effectively rendering non-justiciable the

genuine link requirement, which was first imposed by the 1958 Convention on the High Seas to

address growing concerns over lax flag of convenience states. In fairness, however, any omissions by

Panama as the flag state appear to have been largely irrelevant to the Virginia G’s failure to obtain

Guinea-Bissau’s authorization to bunker fishing vessels in its EEZ.

The tribunal went on to hold that the coastal state’s sovereign rights to conserve and manage living

resources in the EEZ and to adopt laws and regulations establishing the terms and conditions for

access by foreign vessels to the EEZ under Articles 56 and 62 empower the coastal state to regulate

foreign vessels engaging in both fishing and fishing-related activities in its EEZ, including vessels that

provision fishing vessels (paras. 207-222). In reaching its decision, the tribunal observed that the list

of permissible coastal state conservation and management measures in Article 62(4) is not

exhaustive (para. 213). Any non-enumerated measure taken must, however, have a direct connection

to fishing (para. 215). Applying that interpretation, the tribunal upheld Guinea-Bissau’s requirement to

obtain prior written authorization to engage in fishing-related activities in the EEZ (para. 235) and to

assess a fee to defray the cost of processing the authorization (para. 234). By bunkering foreign

fishing vessels without Guinea-Bissau’s written authorization, the Virginia Gviolated the coastal state’s

laws.

The tribunal emphasized that because the coastal state’s competency over fishing and fishing-related

activities like bunkering fishing vessels derives from its sovereign rights over living resources in the

EEZ, it did not establish a more general right to regulate bunkering of vessels not engaged in fishing

(para. 223). The majority left open the question whether a coastal state can regulate non-fishing

related bunkering activities in the EEZ under its Part XII jurisdiction to impose marine environmental

protection measures applicable in the EEZ (para. 224). In a separate opinion, Judges Attard and Kelly

indicated their belief that such regulations were within the coastal state’s competency.

Perhaps the most notable ruling by the tribunal concerns the coastal state’s competency to confiscate

(i.e., forfeit) foreign vessels and their cargoes if found to be in violation of the coastal state’s living

resource laws. The tribunal noted that the list of enforcement measures available to the coastal state

in Article 73(1) includes boarding and arrest of the vessel, but the article does not mention

confiscation (para. 251). At the same time, the article expressly precludes only two forms of sanction:

imprisonment (absent an agreement with the flag state) or any other form of corporal punishment.

Observing that a number of states’ laws include provisions for confiscation (although not cited by the

tribunal, they include the U.S. Magnuson-Stevens Fishery Conservation and Management Act,

Endangered Species Act and Marine Mammal Protection Act), the tribunal interpreted Article 73(1) in

light of that state practice and held that confiscation is not a per seviolation of Article 73(1). The

tribunal went on to adopt a case-by-case approach that amounts to a proportionality test. More

specifically, the tribunal held that a “principle of reasonableness” generally applies to all enforcement

measures under Article 73 (para. 270). Although the tribunal concluded that the Virginia G’s

violations were “serious” (para. 267), mitigating factors persuaded 14 of the tribunal’s 23 judges that

confiscation of the vessel and its cargo was not “necessary” in this case “to ensure compliance with

the laws and regulations adopted by” the coastal state (paras. 256, 269). One might reasonably

question how a coastal state will ever demonstrate that a particular form of sanction is strictly

“necessary.” One is also left wondering how the court’s interpretation of the “necessary” qualifier in

Article 73 might be applied in a future case to that same qualifying term in Article 94(3), which

requires a flag state to take such measures as are “necessary” to ensure safety at sea.

In other sections of the decision a majority of the judges took a somewhat narrow view of what

constitutes “imprisonment” under Article 73(3) (paras. 297-311). Additionally, the tribunal concluded

that Article 225 (imposing a duty to avoid adverse consequences in the exercise of enforcement

powers) applies, by its terms, to all enforcement activities by the coastal state under the convention,

even though that article is in Part XII of the convention, which addresses measures to protect the

marine environment. The tribunal also “reiterated” that general international law establishes a clear

requirement that enforcement activities can be exercised only by duly authorized and identifiable

officials of a coastal state and that their vessels must be clearly marked as being on government

service (para. 342). Finally, the tribunal rejected Panama’s secondary argument that prohibitions in

the Convention for the Suppression of Unlawful Acts against the Safety of Maritime Navigation (SUA)

applied to the actions by Guinea-Bissau’s enforcement vessels (see para. 376, citing the SUA Article

2 exclusion of warships and certain other state vessels).

On a divided vote, the tribunal assessed monetary reparations in favor of Panama totaling $388,506.

In all, there were 13 separate declarations and dissenting opinions.

This is one of the 22 contentious cases presented to ITLOS since it was established in 1996.

Decisions by the tribunal are final and must be complied with by all parties to the dispute; however,

they have no binding force except between the parties and in respect of that particular dispute.

UNCLOS Article 296.

Those weighing the relative merits of U.S. accession to the 1982 Law of the Sea Convention may find

the tribunal’s decision in the M/V Virginia G case troubling. It is, for example, disconcerting that the

tribunal has, on the one hand, determined that a flag state has unreviewable discretion to determine

what constitutes a “genuine link,” while on the other the tribunal has, under a non-textual “principle of

reasonableness,” annexed to itself the power to overrule a coastal state’s decision to impose a

particular form of sanction on a tanker for an admittedly “serious” violation of the coastal state’s laws

implementing its sovereign rights. In this regard, it is noteworthy that Professor Nordquist’s “Virginia

Commentaries” (vol, II, para. 73.10(f)) highlights an important difference between Article 73(3) and

Article 230, which, for most cases, expressly limits coastal state sanctions for marine pollution

violations to “monetary penalties.”

Equally troubling is the scant evidence the tribunal considered before announcing that it had “no

reason to question” whether Panama exercised effective jurisdiction and control over the

tanker Virginia G. At a time when the UN General Assembly is admonishing flag states that cannot

meet their obligations to exercise effective jurisdiction and control over their vessels to essentially “get

out of the flag state business” (UNGA RES/68/70, Feb. 27, 2014, para. 146), and the International

Maritime Organization Assembly seeks to ensure flag states meet their obligations by making the

formerly voluntary audit scheme mandatory, ITLOS appears willing to allow flag states to meet their

effective jurisdiction and control obligation by reviewing applications, issuing the

required documents and technical certificates and delegating annual safety inspections to third

parties (paras. 113-118).

Article73

Enforcement of laws and regulations of the coastal State

1. The coastal State may, in the exercise of its sovereign rights to explore, exploit,

conserve and manage the living resources in the exclusive economic zone, take

such measures, including boarding, inspection, arrest and judicial proceedings, as

may be necessary to ensure compliance with the laws and regulations adopted by it

in conformity with this Convention.

2. Arrested vessels and their crews shall be promptly released upon the posting of

reasonable bond or other security.

3. Coastal State penalties for violations of fisheries laws and regulations in the

exclusive economic zone may not include imprisonment, in the absence of

agreements to the contrary by the States concerned, or any other form of corporal

punishment.

4. In cases of arrest or detention of foreign vessels the coastal State shall promptly

notify the flag State, through appropriate channels, of the action taken and of any

penalties subsequently imposed.

You might also like

- Admiralty Law for the Maritime ProfessionalFrom EverandAdmiralty Law for the Maritime ProfessionalRating: 1 out of 5 stars1/5 (1)

- B-Speech GPS2Document2 pagesB-Speech GPS2tforraiNo ratings yet

- Waitt Institute Re-Navigation RPTDocument100 pagesWaitt Institute Re-Navigation RPTWaitt Institute100% (1)

- Dispute Concerning Delimitation of The Maritime Boundary Between Ghana and Côte D'ivoire in The Atlantic OceanDocument7 pagesDispute Concerning Delimitation of The Maritime Boundary Between Ghana and Côte D'ivoire in The Atlantic OceanSovanrangsey KongNo ratings yet

- Separate and Dissenting Opinion of Judge Ad Hoc OxmanDocument19 pagesSeparate and Dissenting Opinion of Judge Ad Hoc OxmanHMEHMEHMEHMENo ratings yet

- Territorial Sea (Additional Material)Document2 pagesTerritorial Sea (Additional Material)AnonymousNo ratings yet

- International Tribunal For The Law of The SeaDocument11 pagesInternational Tribunal For The Law of The SeaNaga NagendraNo ratings yet

- The High Seas and The International Seabed AreaDocument18 pagesThe High Seas and The International Seabed AreahidhaabdurazackNo ratings yet

- Fallo ICJ NICOLDocument19 pagesFallo ICJ NICOLKevin De La CruzNo ratings yet

- This Content Downloaded From 106.79.237.34 On Sat, 27 Mar 2021 19:50:14 UTCDocument18 pagesThis Content Downloaded From 106.79.237.34 On Sat, 27 Mar 2021 19:50:14 UTCRaj ChouhanNo ratings yet

- The Right of Innocent Passage by Florian H. Th. Wegelein in Seattle - February, 1999Document16 pagesThe Right of Innocent Passage by Florian H. Th. Wegelein in Seattle - February, 1999KBPLexNo ratings yet

- The Right and Duties of Other States in The EEZDocument6 pagesThe Right and Duties of Other States in The EEZOmank Tiny SanjivaniNo ratings yet

- Gulf of Maine CaseDocument3 pagesGulf of Maine CaseJashaswee MishraNo ratings yet

- UNCLOSDocument24 pagesUNCLOSAman Gautam100% (1)

- Assignment (Unclos)Document9 pagesAssignment (Unclos)Ayeta Emuobonuvie GraceNo ratings yet

- ANTUNES, Nuno. Antunes, N. (2001) - The 1999 Eritrea-Yemen Maritime Delimitation Award and The Development of International Law.Document47 pagesANTUNES, Nuno. Antunes, N. (2001) - The 1999 Eritrea-Yemen Maritime Delimitation Award and The Development of International Law.Leo LeoNo ratings yet

- The Obligation of Self-Restraint Under Arts. 74 (3) and 83 (3) of UNCLOSDocument10 pagesThe Obligation of Self-Restraint Under Arts. 74 (3) and 83 (3) of UNCLOSRaquel Soto SanchezNo ratings yet

- Libyan: T H E AgentDocument3 pagesLibyan: T H E Agentprasanth rajuNo ratings yet

- State Responsibility in Disputed Areas On Land and at SeaDocument54 pagesState Responsibility in Disputed Areas On Land and at SeaWorstWitch TalaNo ratings yet

- 1381 Kaye Freedom of Navigation in A Post 911 WorldDocument15 pages1381 Kaye Freedom of Navigation in A Post 911 WorldJuniorNo ratings yet

- Law of The SeaDocument16 pagesLaw of The SeaErastoNo ratings yet

- Memorial On Behalf of The ApplicantDocument5 pagesMemorial On Behalf of The ApplicantNietesh NidhiNo ratings yet

- Maritime Transport Security (Kenneth)Document26 pagesMaritime Transport Security (Kenneth)manohar killiNo ratings yet

- Nat Res MidTerm Review Materials Oct 7 2022Document26 pagesNat Res MidTerm Review Materials Oct 7 2022Errisha PascualNo ratings yet

- INNOCENT PASSAGE-1 (Additional Material)Document2 pagesINNOCENT PASSAGE-1 (Additional Material)AnonymousNo ratings yet

- Challenge To UNCLOSDocument13 pagesChallenge To UNCLOSTran Van ThuyNo ratings yet

- Magalona Vs ErmitaDocument3 pagesMagalona Vs ErmitaRaven TailNo ratings yet

- 154 20230713 Jud 01 00 enDocument36 pages154 20230713 Jud 01 00 enSebastián ArenasNo ratings yet

- EEC (Additional Material)Document5 pagesEEC (Additional Material)AnonymousNo ratings yet

- Hydrographic Surveying in Exclusive Economic Zones: Jurisdictional IssuesDocument10 pagesHydrographic Surveying in Exclusive Economic Zones: Jurisdictional Issueskumar kartikeyaNo ratings yet

- Magalona Vs ErmitaDocument3 pagesMagalona Vs ErmitaAlyssa joy TorioNo ratings yet

- Utsav - International Law Moot MemoDocument8 pagesUtsav - International Law Moot MemoUtsav SinghNo ratings yet

- Maintaining Freedom of Navigation and OverflightDocument19 pagesMaintaining Freedom of Navigation and Overflightstjarnalf804No ratings yet

- Law of The Sea: UNCLOS. It Also Includes Matters Submitted To It Under Any OtherDocument11 pagesLaw of The Sea: UNCLOS. It Also Includes Matters Submitted To It Under Any OtherThemis ArtemisNo ratings yet

- Cellar .0002.06 DOC 1Document9 pagesCellar .0002.06 DOC 1Pintilii AndraNo ratings yet

- GUYANA VS SURINAME BriefDocument6 pagesGUYANA VS SURINAME BriefThremzone17No ratings yet

- Dbsec2 3Document173 pagesDbsec2 3Juan Luis ValleNo ratings yet

- Victory Carriers, Inc. v. Law, 404 U.S. 202 (1972)Document18 pagesVictory Carriers, Inc. v. Law, 404 U.S. 202 (1972)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Jessie Verdine v. Ensco Offshore Co., Defendant-Third Party v. Centin LLC, Formerly Known As Centin Corp., Third Party, 255 F.3d 246, 3rd Cir. (2001)Document9 pagesJessie Verdine v. Ensco Offshore Co., Defendant-Third Party v. Centin LLC, Formerly Known As Centin Corp., Third Party, 255 F.3d 246, 3rd Cir. (2001)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- PC Pfeiffer Co. v. Ford, 444 U.S. 69 (1979)Document13 pagesPC Pfeiffer Co. v. Ford, 444 U.S. 69 (1979)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Maritime Eez Journal MaritimeDocument18 pagesMaritime Eez Journal MaritimeSyahrul Rizki RamadhanNo ratings yet

- Role of Flags States Under Unc Los I I IDocument10 pagesRole of Flags States Under Unc Los I I IKishore nawal100% (1)

- LAW 403 (International Law II)Document3 pagesLAW 403 (International Law II)Anupom Hossain SoumikNo ratings yet

- BLOCK B, GROUP 1 - Characteristics of Criminal Law - PROGRAM MODULE NO. 2Document84 pagesBLOCK B, GROUP 1 - Characteristics of Criminal Law - PROGRAM MODULE NO. 2DerfLiwNo ratings yet

- Part IIB IIIDocument14 pagesPart IIB IIIarmeruNo ratings yet

- Public International Law: Law of The SeaDocument19 pagesPublic International Law: Law of The SeasandeepNo ratings yet

- Casualty Investigation CodeDocument22 pagesCasualty Investigation CodeAlfi Delfi100% (2)

- Meaning and DefinitionDocument3 pagesMeaning and Definitiondivyanshi singhalNo ratings yet

- Chapter 13 Int LawDocument35 pagesChapter 13 Int Lawmarta vaquerNo ratings yet

- The Law of The SeaDocument22 pagesThe Law of The SeaElizabeth Lau100% (3)

- UNCLOS III - Pollution Control in The Exclusive Economic ZoneDocument27 pagesUNCLOS III - Pollution Control in The Exclusive Economic ZoneAvinash PanditNo ratings yet

- Foremost Ins. Co. v. Richardson, 457 U.S. 668 (1982)Document16 pagesForemost Ins. Co. v. Richardson, 457 U.S. 668 (1982)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Turecamo of Savannah, Inc. v. United States, 36 F.3d 1083, 11th Cir. (1994)Document9 pagesTurecamo of Savannah, Inc. v. United States, 36 F.3d 1083, 11th Cir. (1994)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Criminal Jurisdiction Over Terrritorial WatersDocument6 pagesCriminal Jurisdiction Over Terrritorial WatersKaran BhardwajNo ratings yet

- British Transport Comm'n v. United States, 354 U.S. 129 (1957)Document12 pagesBritish Transport Comm'n v. United States, 354 U.S. 129 (1957)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Magallona V Ermita DigestDocument7 pagesMagallona V Ermita DigestPouǝllǝ ɐlʎssɐNo ratings yet

- United States v. Flores, 289 U.S. 137 (1933)Document12 pagesUnited States v. Flores, 289 U.S. 137 (1933)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- 7 The MV Virginia G CaseDocument4 pages7 The MV Virginia G CaseStephen SalemNo ratings yet

- Module 6 AssignmentDocument2 pagesModule 6 AssignmentdaryllNo ratings yet

- Law of The SeaDocument10 pagesLaw of The SeaFarhah NajihaNo ratings yet

- 2018LLB057 Maritime RPDocument20 pages2018LLB057 Maritime RPnikhila katupalliNo ratings yet

- Maritime Labour ConventionFrom EverandMaritime Labour ConventionRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- Joint Department Circular NoDocument4 pagesJoint Department Circular NosujeeNo ratings yet

- Boon or BaneDocument5 pagesBoon or BanesujeeNo ratings yet

- Golden RiceDocument2 pagesGolden RicesujeeNo ratings yet

- Name of Feature Status Maritime EntitlementDocument1 pageName of Feature Status Maritime EntitlementsujeeNo ratings yet

- The Issue: Chanroblesvirtuallaw Lib RaryDocument3 pagesThe Issue: Chanroblesvirtuallaw Lib RarysujeeNo ratings yet

- MONDENO Vs SILVOSADocument1 pageMONDENO Vs SILVOSAsujeeNo ratings yet

- Vios Receipt EditedDocument2 pagesVios Receipt EditedsujeeNo ratings yet

- WHEREFORE, Premises Considered, Judgment Is Rendered Confirming The Title of The Applicant RemmanDocument3 pagesWHEREFORE, Premises Considered, Judgment Is Rendered Confirming The Title of The Applicant RemmansujeeNo ratings yet

- Tax 1 CasesDocument34 pagesTax 1 CasessujeeNo ratings yet

- Election Laws 123Document6 pagesElection Laws 123sujeeNo ratings yet

- Salient Features of The Revised Guidelines For Continuous Trial of Criminal CasesDocument3 pagesSalient Features of The Revised Guidelines For Continuous Trial of Criminal CasessujeeNo ratings yet

- K. Liability: vs. Fortune Tobacco Corporation, G.R. No. 141309, June 19, 2007)Document5 pagesK. Liability: vs. Fortune Tobacco Corporation, G.R. No. 141309, June 19, 2007)sujeeNo ratings yet

- Labor Review SyllabusDocument56 pagesLabor Review SyllabussujeeNo ratings yet

- Regulation - 1031 - OHS - General Safety RegulationsDocument24 pagesRegulation - 1031 - OHS - General Safety Regulationsmubeenhassim100% (1)

- Horton V MasterDocument2 pagesHorton V MasterNicole GardnerNo ratings yet

- General Arrangement Plan Lecture PDFDocument58 pagesGeneral Arrangement Plan Lecture PDFAktarojjaman Milton100% (2)

- German ATV DVWK A 157E Sewer System Structures 2000 PDFDocument32 pagesGerman ATV DVWK A 157E Sewer System Structures 2000 PDFJosip Medved100% (2)

- Boatus20130809 DLDocument94 pagesBoatus20130809 DLjoeblidaNo ratings yet

- Body Electrical BodyDocument298 pagesBody Electrical BodyLoc TruongNo ratings yet

- AHM565 Turkish Airlines - A320-232Document46 pagesAHM565 Turkish Airlines - A320-232Nguyen Duc BinhNo ratings yet

- Dark Elf RaidersDocument1 pageDark Elf RaidersafwsefwefvNo ratings yet

- Ansonfarm Malaysia 安顺农业机械 ⼯程: PhotosDocument1 pageAnsonfarm Malaysia 安顺农业机械 ⼯程: PhotosAhmad AqilNo ratings yet

- Go FL DMT and Ee A 40164421357Document3 pagesGo FL DMT and Ee A 40164421357कुँ. विकास सिंह राजावतNo ratings yet

- Design of Steel Bridges: Components and ClassificationDocument67 pagesDesign of Steel Bridges: Components and ClassificationMohamed HalimNo ratings yet

- Scope of Work EC14638Document12 pagesScope of Work EC14638Anantha NarayananNo ratings yet

- Road Freight Learning Unit 1Document25 pagesRoad Freight Learning Unit 1percyNo ratings yet

- TunnelEngineering - COWIDocument44 pagesTunnelEngineering - COWIantoniusnoro100% (1)

- SlidesDocument563 pagesSlidessalomao321No ratings yet

- Step by Step Redelivery Guide SagawaDocument2 pagesStep by Step Redelivery Guide SagawaSyafri WardiNo ratings yet

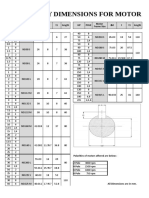

- Standard Key Dimensions For Motor: HP Pole Ød T t1 Length HP Pole Ød T t1 Length Motor Frame Size Motor Frame SizeDocument7 pagesStandard Key Dimensions For Motor: HP Pole Ød T t1 Length HP Pole Ød T t1 Length Motor Frame Size Motor Frame Sizeketan mehtaNo ratings yet

- Sdre14-14 Bol 1-5-1dec17Document6 pagesSdre14-14 Bol 1-5-1dec17Yam BalaoingNo ratings yet

- TC and TCDS Revision 6 ApprovedDocument19 pagesTC and TCDS Revision 6 ApprovedKrishna bogiNo ratings yet

- Schematic - ESP32 ESP-WROOM-32 Breakout Rev 1 Copy - 2021-05-28Document2 pagesSchematic - ESP32 ESP-WROOM-32 Breakout Rev 1 Copy - 2021-05-28Razwan ali saeedNo ratings yet

- CW 2-1 Comparing Groups (Boxplots)Document2 pagesCW 2-1 Comparing Groups (Boxplots)cruzk788724No ratings yet

- Product Knowledge GR500EXL-3 and OperationDocument54 pagesProduct Knowledge GR500EXL-3 and OperationYacob PangihutanNo ratings yet

- Highwall Miner HWM 300Document20 pagesHighwall Miner HWM 300Amit100% (1)

- Axle Boot MarutiDocument2 pagesAxle Boot MarutinrjmanitNo ratings yet

- Cat05 PDF 80-99Document20 pagesCat05 PDF 80-99Rafael ReisNo ratings yet

- BOP TRANSPORTATION SKID SAFE OPERATING MANUAL - Rev.1Document20 pagesBOP TRANSPORTATION SKID SAFE OPERATING MANUAL - Rev.1cmrig7467% (3)

- Newtrasdata Ecu ListDocument7 pagesNewtrasdata Ecu ListdoktorskiNo ratings yet

- Outline Design Specification For Phase IV Revision 2 July 2021 10082021Document145 pagesOutline Design Specification For Phase IV Revision 2 July 2021 10082021CIVIL ENGINEERINGNo ratings yet