Professional Documents

Culture Documents

The Transition To Practice in Psychiatry: A Practical Guide

The Transition To Practice in Psychiatry: A Practical Guide

Uploaded by

putrishabrinaOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

The Transition To Practice in Psychiatry: A Practical Guide

The Transition To Practice in Psychiatry: A Practical Guide

Uploaded by

putrishabrinaCopyright:

Available Formats

Down to Earth

The Transition to Practice in Psychiatry:

A Practical Guide

Ryan J. Van Lieshout, M.D., FRCP(C)

James A. Bourgeois, O.D., M.D.

A lthough the transition from residency training to in-

dependent practice is an exciting time in one’s life,

without preparation it can be unnecessarily stressful (1, 2).

their type of practice, what they consider important in

selecting a position, and what they would have done dif-

ferently were they in the resident’s position at the present

Many psychiatry residents feel that although their training time.

programs prepare them well for the rigors of clinical work,

the same cannot be said for the provision of information Making the Practice-Choice Decision

on career options and supporting decision-making around

selecting a post-residency position and starting a practice Borus (3) has outlined the steps that residents com-

(2). monly take in making a practice-choice decision (Table 1),

Below, we provide a brief guide that outlines the and these will provide the framework for our discussion of

career options available to new psychiatry graduates, the optimization of this process. It is of value to initiate

factors relevant to selecting a position, steps that may this transition by the beginning of the last year of resi-

be taken to qualify for independent practice, and how to dency and to consult colleagues, mentors, and loved ones

start a thriving career. We describe these from the per- frequently.

spective of the transition to practice in the province of The first, and potentially most anxiety-inducing stage of

Ontario, Canada. making a practice-choice decision is undertaking the task

itself. The second stage involves the definition of impor-

Practice Options tant professional and personal issues that will affect the

practice choice. Important professional factors to consider

Making informed career decisions requires familiarity include intellectual stimulation and preferred practice

with the options available. In many contexts, numerous style. Remuneration, workload, and protected time for re-

non-academic possibilities exist; these include private of- search, teaching, and administration are also important. In

fice practice, general inpatient or outpatient psychiatry in an academic department, clinician-researchers should have

a hospital setting, providing care in shared-care models, 50%– 80% of their time allotted to research with salary

working for the pharmaceutical or insurance industries, or support for the first few years. A clinician-educator should

a combination of these. Within the academic environment, expect 10%–20% of his or her time to be protected for

one can take a position as a fellow, a clinician-educator, scholarship indefinitely (4). Important personal and family

clinician-administrator, or clinician-researcher. considerations should also be considered (Table 2).

Each type of position provides the psychiatrist with a Developing an “ideal job” profile can help to establish

different mix of payment models and patient populations, the qualities a desired position should possess. A helpful

each with specific advantages and disadvantages. Often, it technique is visualizing the ideal career and personal life

is helpful to ask practicing psychiatrists why they chose “5 years down the road.” Discussions with decision-facil-

itators, including family members and professional men-

Received, accepted February 9, 2011. Dept. of Psychiatry and tors, can aid in this process. It is at this stage, when

Biobehavioural Neurosciences, McMaster University, Hamilton, important issues are prioritized, that feelings of depression

Ontario, Canada. Send correspondence to Dr. Van Lieshout; Drvanlierj@

mcmaster.ca (e-mail). often emerge (3). However, this is generally considered to

Copyright © 2012 Academic Psychiatry be normative and is usually self-limited.

142 http://ap.psychiatryonline.org Academic Psychiatry, 36:2, March-April 2012

VAN LIESHOUT AND BOURGEOIS

Next, the resident prepares a “professional presentation” coworkers. Discussing these experiences with decision-

by updating the curriculum vitae and creating a cover facilitators can be useful.

letter describing qualifications and special skills to poten- Next, the process of contract-negotiation begins. Suc-

tial employers. Having these reviewed by senior col- cessful negotiation relies on preparation and bargaining.

leagues is a helpful exercise. Developing clear professional goals that are congruent

The resident then explores practice opportunities. This with those of the proposed employer and having the means

can involve perusing the classified sections of journals, to achieve these can be very persuasive. The resident

web pages of hospitals and academic departments of psy- needs to be aware that there is a power differential

chiatry, contacting department chairs and chiefs of clinical between him/her and departmental chairs. Taking a po-

service, and networking with colleagues and mentors. A sition of courteous assertiveness is generally the best

number of websites list local, national, or international job approach to negotiation in this setting. By the end of the

opportunities. HealthForce Ontario (www.HFOjobs.ca), negotiation process, the resident should understand the

medicalemployers.com, mdsearch.com, mdjobsite.com, balance between clinical and academic expectations rel-

and mentalhealthjobs.co.uk are just a few of the online evant to a position. Because there is no such thing as a

resources that can help connect residents to potential em- “standard contract,” a lawyer should review this docu-

ployers. ment before signing (6). After selection and commit-

The resident then visits and/or interviews at potential ment to practice, a decrease in anxiety and depression is

work settings. Site visits allow for assessment of “good- expected.

ness of fit.” Speaking with other residents, recent gradu-

ates, and senior faculty members can help the resident put Preparing for Practice

his or her marketability into perspective. As relationships

with colleagues are important determinants of professional The last phase of practice-choice decision-making in-

satisfaction (5), it is important to meet potential future volves formally preparing for practice. In Canada, this

begins with the completion of the Royal College of Phy-

sicians and Surgeons of Canada (FRCP(C)) fellowship

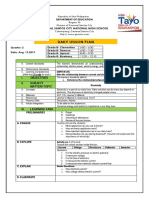

TABLE 1. Steps for Practice-Choice Decision-Making examinations and is followed by the acquisition of an

independent practice license from the College of Physi-

1. Acknowledging and undertaking the practice choice

2. Defining personal and professional issues cians and Surgeons of their province or territory. Since

3. Establishing reward priorities and minimal requirements most psychiatric services rendered by psychiatrists in Can-

4. Professional presentation ada are covered by government-paid health insurance

5. Inquiring about opportunities

6. Interviewing plans, acquiring a billing number is vital. Other pragmatic

7. Negotiating professional issues that should be addressed before start-

8. Committing ing a new position are obtaining hospital privileges, com-

9. Preparing for practice

10. Using decision-facilitatorsa

pleting facility orientations, and the acquisition of security

passes and dictation numbers. For residents training in

a

Affects Steps 1-9. Canada, updating professional liability coverage requires a

TABLE 2. Factors to Consider in Selecting an Independent Practice Choice

Personal Factors Professional Factors

Location Salary

Community size Protected time (research/teaching/administration/CME)

School quality Clinical and clerical support

Spousal employment prospects Office and lab space

Access to leisure activities Non-clinical responsibilities

Potential for maintaining privacy Collegiality of the work environment

Housing cost and availability Opportunities for promotion

Potential for intellectual stimulation Call frequency

Mentorship availability Benefits

Vacation coverage

Scope of practice

Academic Psychiatry, 36:2, March-April 2012 http://ap.psychiatryonline.org 143

PRACTICAL GUIDE TO PRACTICE TRANSITION

change of the Canadian Medical Protective Association review contracts, advise on legal issues relating to starting

code. Because these steps can take months to complete, an office, and help construct a financial plan.

the resident should initiate this process well in advance of

graduation. At this stage, seeking guidance from recent Coping With the Challenges Faced by the Early-

graduates can be of value. Career Psychiatrist

During residency, it is wise to become familiar with

local billing codes. This can be facilitated via billing- New psychiatrists will face myriad challenges in their first

tutorials provided by residency-training programs or by years of independent practice. Although by no means exhaus-

residents’ completing “exercise” billings for patients and tive, the following list is intended to help the trainee antici-

comparing these with their supervising faculty’s billing pate these issues and develop ways of managing them.

submissions (i.e., “shadow billing”). Faculty members The stress of independent decision-making is a chal-

who have private practices can provide important infor- lenge faced by many new psychiatrists. However, adher-

mation to residents on topics ranging from setting up a ence to the principles of diagnosis, treatment, risk-man-

practice and office, to scheduling, medical-record manage- agement, and documentation learned during training can

ment, and professional incorporation. The Canadian Med- mitigate these risks. The newly-graduated psychiatrist

ical Association (www.cma.ca) has produced a series of must realize that he or she is not alone and is encouraged

online documents that can aid trainees in navigating the to discuss cases with colleagues and/or ask for help.

complexities of setting up an office. Understanding one’s limitations can also be helpful in

easing the transition. New graduates often try to live up to

Optimizing Health During the Transition the impossible standards set by the over-idealized “triple-

threat” academic psychiatrists they encounter in training

The end of residency is an exciting time that is marked (9). Attempting to live up to these standards early on is

by new challenges and losses. Leaving the resident peer- unreasonable and can lead to feelings of inadequacy.

group and a familiar clinical system can be difficult. Un- Setting limits can help to guard against one’s tendency

derstanding the emotions associated with these changes to work too much or too long. Educating patients and

and utilizing supports can be helpful. Coping mechanisms referral sources on the scope of available services can help

listed by new psychiatrists as very helpful in adapting to promote an enjoyable workplace. Setting a reasonable

early psychiatric practice include emotional support from number of work hours per week and guarding this closely

spouse, play and recreation, ad-hoc consultations with col- may also help. Factoring extra time into one’s day for

leagues, relationships with peers, vacation or time off, administration and paperwork can save headaches and late

reading, creative activities, hobbies, and exercise (2). home-arrivals, and maintain a healthy set of order and

Avoiding isolation is very important to one’s success. boundaries.

Professional isolation is associated with increased levels It is inevitable that psychiatrists will receive patient

of work-related stress and dissatisfaction with one’s posi- care-related complaints during their careers. These can

tion (7). As a result, many new physicians in independent feel hurtful, but it is important to remain calm and, if

practice find it helpful to join a practice-group, where possible, take some time before responding to them. Doc-

knowledge and experiences can be shared with other psy- umenting complaints and one’s responses is sound, from a

chiatrists and the transition normalized. Unfortunately, medico-legal perspective. If it is appropriate, one should

physicians are often not very good at prioritizing and not be afraid to apologize to the patient (and/or family

managing their personal health. In addition to attending to member(s)). Under the Apology Act in Ontario, apologies

one’s own psychological health, Puddester recommends cannot be used as evidence of liability against a physician

that early-career physicians get their own primary-care (10), and disclosure may actually lessen the risk of being

physicians, participate in recreational activities, get ade- sued (11).

quate rest and proper nutrition, and nurture professional

and personal relationships (8). Conclusions

The early-career psychiatrist should consider retaining

the services of an accountant, lawyer, and financial adviser The transition to independent practice in psychiatry is

as a means of easing the transition to practice. These an exciting time in a physician’s life. Knowledge of the

professionals can help physicians optimize their earnings, transition and its impact can be helpful, as can the nurtur-

144 http://ap.psychiatryonline.org Academic Psychiatry, 36:2, March-April 2012

VAN LIESHOUT AND BOURGEOIS

ance of familial and collegial relationships. Consultation 4. Saha S, Saint S, Christakis DA, et al: A survival guide for

with decision-facilitators is vital throughout the transition generalist physicians in academic fellowships. J Gen Intern

Med 1999; 14:750 –755

process and beyond and can help ease the transition to

5. Bernston A: Are you ready for the country? CPA Bull 2003;

independent professional life. 15–16

Manuscripts authored by an editor of Academic Psy- 6. Belitz J: Negotiating with the department chair, in Handbook

of Career Development in Academic Psychiatry and Behav-

chiatry or a member of its editorial or advisory board

ioral Sciences. Edited by Roberts LW, Hilty DM. Washing-

undergo the same editorial review process, including ton DC, American Psychiatric Publishing, Inc., 2006

blinded peer-review, applied to all manuscripts. Also, the 7. St. George I: Professional isolation and performance assess-

editor is recused from any editorial decision-making. ment in New Zealand. J Cont Educ Health Prof 2006; 26:

216 –221

References 8. Puddester D: The early-career psychiatrist: perspective on

academic and personal development. CPA Bull 2003;

1. Borus JF: The transition-to-practice seminar. Am J Psychia- 11–14

try 1978; 135:1513–1516 9. Cavanaugh JL: Career decisions in the early post-residency

2. Looney JH, Harding RK, Blotcky MJ, et al: Psychiatrists’ years. Am J Psychiatry 1975; 132:277–280

transition from training to career: stress and mastery. Am J 10. College of Physicians and Surgeons of Ontario: Disclosure of

Psychiatry 1980; 137:32–36 Harm. Dialogue 2010; 2

3. Borus JF: The transition to practice. J Med Educ 1982; 11. Wu A: Handling hospital errors: is disclosure the best de-

57:593– 601 fense? Ann Intern Med 1999; 131:970 –972

Academic Psychiatry, 36:2, March-April 2012 http://ap.psychiatryonline.org 145

You might also like

- Advanced Practice Nursing Essentials For Role Development 4e PDFDocument531 pagesAdvanced Practice Nursing Essentials For Role Development 4e PDFCELINE MARTJOHNS100% (6)

- Final Exam HSC 312Document5 pagesFinal Exam HSC 312Milgrid GuzmanNo ratings yet

- 513.1 Understand The Theory and Principles That Underpin Outcome BasedDocument4 pages513.1 Understand The Theory and Principles That Underpin Outcome BasedChrystina Elena100% (1)

- Author's Accepted Manuscript: Current Problems in Diagnostic RadiologyDocument12 pagesAuthor's Accepted Manuscript: Current Problems in Diagnostic Radiologyanon_580507788No ratings yet

- Career Counseling Thesis PDFDocument8 pagesCareer Counseling Thesis PDFheduurief100% (2)

- Advocating For The Counselling PROFESSIONDocument7 pagesAdvocating For The Counselling PROFESSIONOkumuNo ratings yet

- Common Role HR in BpoDocument10 pagesCommon Role HR in Bpoashwin thakurNo ratings yet

- How To Plan A Successful Associateship and Practice TransitionDocument10 pagesHow To Plan A Successful Associateship and Practice TransitionГулпе АлексейNo ratings yet

- Student Clinic Manual 2017-2018Document34 pagesStudent Clinic Manual 2017-2018Daniel - Mihai LeşovschiNo ratings yet

- Professionalism in Healthcare Professionals: Research ReportDocument68 pagesProfessionalism in Healthcare Professionals: Research ReportSueNo ratings yet

- EPID Masters Practicum Proposal Form 2017Document5 pagesEPID Masters Practicum Proposal Form 2017George HillNo ratings yet

- CIF Razonamiento ClinicoDocument16 pagesCIF Razonamiento ClinicoDavid ParraNo ratings yet

- Healthcare Management CourseworkDocument7 pagesHealthcare Management Courseworkfrebulnfg100% (2)

- Nurse CourseworkDocument5 pagesNurse Courseworkshvfihdjd100% (1)

- Writing Thesis Evaluation ReportDocument7 pagesWriting Thesis Evaluation ReportHeather Strinden100% (1)

- Interpersonal SkillsDocument2 pagesInterpersonal SkillsUmarameshKNo ratings yet

- Ot CourseworkDocument4 pagesOt Courseworkpqdgddifg100% (2)

- Chiropractic Course WorkDocument6 pagesChiropractic Course Workkllnmfajd100% (1)

- 4010a3sampleno 2Document6 pages4010a3sampleno 2Derick CheruyotNo ratings yet

- Coursework For Occupational TherapistDocument5 pagesCoursework For Occupational Therapistf1vijokeheg3100% (2)

- Work Experience For Nursing CourseDocument4 pagesWork Experience For Nursing Coursef5d7ejd0100% (2)

- HRM Prakhar AswaniDocument5 pagesHRM Prakhar Aswaniprakhar aswaniNo ratings yet

- Finding Your First Job Are Orthopedists in Training and Hiring Medical Practices On The Same PageDocument7 pagesFinding Your First Job Are Orthopedists in Training and Hiring Medical Practices On The Same PageAthenaeum Scientific PublishersNo ratings yet

- Chapter 4 Physical Therapist As Patient Client ManagerDocument21 pagesChapter 4 Physical Therapist As Patient Client Managersdr fahadNo ratings yet

- Professional Portfolio Assignment Part DDocument6 pagesProfessional Portfolio Assignment Part Dapi-651962342No ratings yet

- Q1 W7 Mod7 PlanningTechniqueToolsDocument4 pagesQ1 W7 Mod7 PlanningTechniqueToolsCharlene EsparciaNo ratings yet

- Climbing The Ladder From Novice To Expert Plastic SurgeonDocument7 pagesClimbing The Ladder From Novice To Expert Plastic SurgeonLuiggi FayadNo ratings yet

- Interpersonal SkillsDocument3 pagesInterpersonal Skillsluciana fardilaNo ratings yet

- The Role of The Occupational TherapistDocument4 pagesThe Role of The Occupational TherapistMD Luthfy LubisNo ratings yet

- Good Professional Practice For Biomedical ScientistsDocument6 pagesGood Professional Practice For Biomedical ScientistsErick InsuastiNo ratings yet

- ProfessionalismDocument3 pagesProfessionalismEbronicaIvyNo ratings yet

- HSO 408 Assessment Task 3 ThingsDocument7 pagesHSO 408 Assessment Task 3 Thingssidney drecotteNo ratings yet

- Executive Summary 1Document12 pagesExecutive Summary 1lizNo ratings yet

- Hospital Administration Dissertation PDFDocument6 pagesHospital Administration Dissertation PDFOnlinePaperWritingServicesSingapore100% (1)

- PTJ 0416Document15 pagesPTJ 0416EemaNo ratings yet

- InternshipDocument8 pagesInternshipmahmoudNo ratings yet

- Human Services CourseworkDocument4 pagesHuman Services Courseworkydzkmgajd100% (2)

- Formative 1 - Ans KeyDocument47 pagesFormative 1 - Ans KeyDhine Dhine ArguellesNo ratings yet

- Reflective Practice ToolkitDocument4 pagesReflective Practice ToolkitPhyoNyeinChanNo ratings yet

- Career Guidance and CounsellingDocument23 pagesCareer Guidance and CounsellingAhimbisibwe BakerNo ratings yet

- Instructor Manual - Chapter 4Document35 pagesInstructor Manual - Chapter 4Nam BanhNo ratings yet

- Implementation PlanDocument4 pagesImplementation Planapi-557858701No ratings yet

- Managing Performance ConcernsDocument17 pagesManaging Performance ConcernsN VNo ratings yet

- Notes - Strategic Planning in Healthcare OrganizationsDocument7 pagesNotes - Strategic Planning in Healthcare Organizationsalodia_farichaiNo ratings yet

- OT Profile As A GuideDocument8 pagesOT Profile As A GuideClara WangNo ratings yet

- Registered Nurse Research Paper ConclusionDocument4 pagesRegistered Nurse Research Paper Conclusiongw0935a9100% (1)

- Fundamental Characteristics of A ProfessionDocument14 pagesFundamental Characteristics of A ProfessionNega TesfaNo ratings yet

- Ethics Form For Dissertation TemplateDocument8 pagesEthics Form For Dissertation TemplateCustomNotePaperAtlanta100% (1)

- Level 2 Unit Hsc2028 Move and Position Individuals in Accordance With Their Plan of CareDocument4 pagesLevel 2 Unit Hsc2028 Move and Position Individuals in Accordance With Their Plan of CareMohammad Tayyab KhanNo ratings yet

- Nursing Program Course WorkDocument7 pagesNursing Program Course Workafjwfzekzdzrtp100% (2)

- Occupational Therapy Thesis PaperDocument7 pagesOccupational Therapy Thesis PaperBria Davis100% (2)

- Case Report: A Tool For Clinical Reasoning and Reflection Using The InternationalDocument15 pagesCase Report: A Tool For Clinical Reasoning and Reflection Using The InternationalNishtha singhalNo ratings yet

- Lesson 2 Reviewer - Decision Making and PlanningDocument3 pagesLesson 2 Reviewer - Decision Making and PlanningmanuelNo ratings yet

- Issues Related To Training Professional TherapistsDocument11 pagesIssues Related To Training Professional TherapistsSaroja Roy100% (1)

- Student Nurse CourseworkDocument4 pagesStudent Nurse Courseworkshvfihdjd100% (2)

- Apply Qaulity ControlDocument47 pagesApply Qaulity Controlnatnael danielNo ratings yet

- Supervision Resource Manual Second Edition March 2009Document27 pagesSupervision Resource Manual Second Edition March 2009sumbelmalik17No ratings yet

- Personal DevelopmentDocument16 pagesPersonal DevelopmentKim Rose BorresNo ratings yet

- Standards of Proficiency Biomedical ScientistsDocument20 pagesStandards of Proficiency Biomedical ScientistsIlfan KazaroNo ratings yet

- Orthopedic Practice Management: Strategies for Growth and SuccessFrom EverandOrthopedic Practice Management: Strategies for Growth and SuccessEric C. MakhniNo ratings yet

- Ino 1Document1 pageIno 1putrishabrinaNo ratings yet

- Meds CapeDocument13 pagesMeds CapeputrishabrinaNo ratings yet

- Tea Tree Oil AcneDocument6 pagesTea Tree Oil AcneputrishabrinaNo ratings yet

- Chapter IIDocument23 pagesChapter IIputrishabrinaNo ratings yet

- Evidence-Based Medicine Intrapericardial Left Ventricular Assist Device For Advanced Heart FailureDocument9 pagesEvidence-Based Medicine Intrapericardial Left Ventricular Assist Device For Advanced Heart FailureputrishabrinaNo ratings yet

- R.T. Leuchtkafer's BibliographyDocument23 pagesR.T. Leuchtkafer's BibliographysmallakeNo ratings yet

- ERDGEISTDocument73 pagesERDGEISTJorge RauberNo ratings yet

- SALES Reviewer 2Document7 pagesSALES Reviewer 2Mav Zamora100% (1)

- Tijam vs. Sibonghanoy (23 Scra 29)Document2 pagesTijam vs. Sibonghanoy (23 Scra 29)Teresa Cardinoza100% (1)

- UCSPDocument1 pageUCSPMEAH BAJANDENo ratings yet

- Graduate Chemical Kinetics & TransportDocument6 pagesGraduate Chemical Kinetics & Transportnanofreak3No ratings yet

- Daily Lesson Plan: I. Objectives II. Subject Matter/ TopicDocument2 pagesDaily Lesson Plan: I. Objectives II. Subject Matter/ TopicANGELIQUE DIAMALONNo ratings yet

- Endocrine Problems of The Adult ClientDocument18 pagesEndocrine Problems of The Adult ClientMarylle AntonioNo ratings yet

- SPM Biology NotesDocument32 pagesSPM Biology NotesAin Fza0% (1)

- Fs 8Document12 pagesFs 8May Cruzel TorresNo ratings yet

- MCQ Class X Polynomials Question Answers (40) 1Document10 pagesMCQ Class X Polynomials Question Answers (40) 1Anonymous gfo1wgNo ratings yet

- Ventolin Nebules CmiDocument3 pagesVentolin Nebules CmiJashim JumliNo ratings yet

- Analysis of Colonialism and Its Impact in Africa Ocheni and Nwankwo CSCanada 2012 PDFDocument9 pagesAnalysis of Colonialism and Its Impact in Africa Ocheni and Nwankwo CSCanada 2012 PDFkelil Gena komichaNo ratings yet

- LUTHERAN Gregorian Psalter and Canticles Matins Vespers 1897Document488 pagesLUTHERAN Gregorian Psalter and Canticles Matins Vespers 1897Peter Brandt-SorheimNo ratings yet

- Yoruba and Benin Kingdom - Ile Ife The Final Resting Place of HistoryDocument5 pagesYoruba and Benin Kingdom - Ile Ife The Final Resting Place of HistoryugwakaluNo ratings yet

- CHAPTER IV KamalDocument19 pagesCHAPTER IV KamalABNo ratings yet

- Mains Filter 250V 25A Article Number B3058365K BarcoDocument3 pagesMains Filter 250V 25A Article Number B3058365K Barcojay leeNo ratings yet

- Unit 3 Mark Scheme June 2011Document49 pagesUnit 3 Mark Scheme June 2011PensbyPsyNo ratings yet

- CDCP - 02.28.11 - Titration Excel PracticeDocument2 pagesCDCP - 02.28.11 - Titration Excel PracticeSeleneblueNo ratings yet

- John Carter of Mars QuickstartDocument27 pagesJohn Carter of Mars QuickstartCarl Dettlinger100% (2)

- Harley Davison AssigementDocument12 pagesHarley Davison Assigementamarachi chris-maduNo ratings yet

- PronunciationDocument54 pagesPronunciationsddadhak90% (20)

- SentinaDocument10 pagesSentinaakayaNo ratings yet

- High-Rise Climb V0.6a SmokeydotsDocument10 pagesHigh-Rise Climb V0.6a SmokeydotsRomi MardianaNo ratings yet

- Sales Manager: About Role at Whitehat JRDocument2 pagesSales Manager: About Role at Whitehat JRjoy 11No ratings yet

- Fairchild V.glenhaven Funeral Services LTDDocument9 pagesFairchild V.glenhaven Funeral Services LTDSwastik SinghNo ratings yet

- STB1093 Lect Schedule Sem 2 2018 - 2019Document3 pagesSTB1093 Lect Schedule Sem 2 2018 - 2019Alex XanderNo ratings yet

- 10th 2nd Lang Eng 1Document31 pages10th 2nd Lang Eng 1Pubg KeliyeNo ratings yet

- Free Body Diagrams - Essential PhysicsDocument37 pagesFree Body Diagrams - Essential PhysicsHendra du NantNo ratings yet

- Running Head: Anssoff Matrix Analysis of Adnams CompanyDocument6 pagesRunning Head: Anssoff Matrix Analysis of Adnams CompanyMichaelNo ratings yet