Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Superficial Dry - Trial - Edwards - 2003 PDF

Superficial Dry - Trial - Edwards - 2003 PDF

Uploaded by

michalOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Superficial Dry - Trial - Edwards - 2003 PDF

Superficial Dry - Trial - Edwards - 2003 PDF

Uploaded by

michalCopyright:

Available Formats

6419/37 AIM21(3) 30/9/03 3:02 PM Page 80

Downloaded from aim.bmj.com on July 19, 2012 - Published by group.bmj.com

Papers

Superficial Dry Needling and Active Stretching

in the Treatment of Myofascial Pain –

A Randomised Controlled Trial

Janet Edwards, Nicola Knowles

Janet Edwards Summary

physiotherapist A pragmatic, single blind, randomised, controlled trial was conducted to test the hypothesis that

Lancaster, UK

superficial dry needling (SDN) together with active stretching is more effective than stretching alone, or

Nicola Knowles no treatment, in deactivating trigger points (TrPs) and reducing myofascial pain.

senior lecturer Forty patients with musculoskeletal pain, referred by GPs for physiotherapy, fulfilled inclusion /

School of Health and

Social Science exclusion criteria for active TrPs. Subjects were randomised into three groups: group 1 (n=14) received

Coventry University, UK superficial dry needling (SDN) and active stretching exercises (G1); group 2 (n=13) received stretching

Correspondence:

exercises alone (G2); and group 3 (n=13) were no treatment controls (G3). During the three-week

Janet Edwards intervention period for G1 and G2, the number of treatments varied according to the severity of the

condition and subject/clinician availability. Assessment was carried out pre-intervention (M1), post-

janetedwards_physio

@yahoo.co.uk intervention (M2), and at a three-week follow up (M3). Outcome measures were the Short Form McGill

Pain Questionnaire (SFMPQ) and Pressure Pain Threshold (PPT) of the primary TrP, using a Fischer

algometer. Ninety-one per cent of assessments were blind to grouping.

At M2 there were no significant inter-group differences, but at M3, G1 demonstrated significantly

improved SFMPQ versus G3 (p=0.043) and significantly improved PPT versus G2 (p=0.011). There were

no differences between G2 and G3. The mean PPT and SFMPQ scores correlated significantly in G1

only, though no significant inter-group differences were demonstrated. Numbers of patients requiring

further treatment following the trial were: 6 (G1); 12 (G2); 9 (G3). Conclusion: SDN followed by active

stretching is more effective than stretching alone in deactivating TrPs (reducing their sensitivity to

pressure), and more effective than no treatment in reducing subjective pain. Stretching without prior

deactivation may increase TrP sensitivity.

Keywords

Myofascial trigger point; myofascial pain; acupuncture; superficial dry needling, active stretching

exercise; randomised controlled trial.

Introduction TrPs commonly arise from muscle overload, either

Myofascial Trigger Points (TrPs) are a common as a result of acute strain/trauma, or of a more

source of musculoskeletal pain presenting in prolonged nature due to habitual postures or

primary care.1 General practitioners frequently refer repetitive activities placing abnormal stresses on

these patients to physiotherapy departments for specific muscle groups.4 It is thought that if

treatment. Identifying TrPs requires training and normal healing does not occur, sensitisation of

clinical expertise.2;3 Whilst British undergraduate peripheral nociceptors by endogenous substances

medical and physiotherapy training does not becomes prolonged, leading to increased local

include TrP identification, substantial literature 4;5 tenderness and referred pain. Sensitisation also

and postgraduate training are available. Despite takes place at spinal level, where receptive fields

this there is evidence that TrPs causing in the dorsal horn extend and become sensitive to

musculoskeletal pain often go undiagnosed by lesser stimuli.11 One hypothesis suggests that TrPs

both doctors and physiotherapists, leading to develop at motor end plates, where sensitisation of

chronic conditions. 6-10 sensory and autonomic nerve endings leads to

ACUPUNCTURE IN MEDICINE 2003;21(3):80-86.

80 www.medical-acupuncture.co.uk/aimintro.htm

6419/37 AIM21(3) 30/9/03 3:02 PM Page 81

Downloaded from aim.bmj.com on July 19, 2012 - Published by group.bmj.com

Papers

excessive release of acetylcholine, preventing needling. A review of 23 studies of needling

normal functioning of the calcium pump therapies for myofascial pain (mostly DDN)

mechanism, resulting in sustained contraction of concluded that since no method demonstrated

sarcomeres.4 The contracted muscle fibres superiority, patient comfort should be a main

compress blood vessels, causing local hypoxia. An consideration.29

energy crisis ensues as the increased energy Baldry claims minimal patient discomfort

demand from sustained contraction cannot be met during 20 years’ successful practice using SDN at

because of local hypoxia.4 5-10mm depth.23 In common with Baldry, one

Whilst universally accepted classification author (JE) experiences notable success in clinical

criteria have yet to be established, active TrPs are practice in deactivating TrPs by SDN, needling

typified by tender spots in taut muscular bands, to a depth of 4mm. It has been suggested that

pressure on which reproduces the patient’s pain in as the needle pierces the skin, A-delta nerve

typical patterns for each TrP.12 Local twitch fibres are activated, resulting in inhibition of

responses (LTRs) may be elicited by snapping muscular C-fibres conveying pain from the TrP.23

palpation. Spontaneous electrical activity (SEA) Subsequent relaxation of the TrP’s taut muscular

has been identified at minute loci of TrPs.13-15 band enables the energy crisis at the motor end

Macdonald found that both active and passive plate to resolve. Restoring the affected muscle

stretching of muscles containing TrPs, increased to its full range of movement following TrP

pain, whereas movements in which muscles deactivation is an essential part of recovery, with

worked as the agonist (isotonically) did not.16 If three slow active stretches being recommended.4;30

resistance was applied to the muscle (isometric With preceding factors in mind a pragmatic,

contraction) pain was again increased. randomised, single blind controlled trial was carried

TrP deactivation is a term introduced by out to test the hypothesis that SDN together with

Baldry to describe the process whereby an active active stretching is more effective than stretching

TrP becomes inactive i.e. local tenderness on alone, or no treatment, in deactivating TrPs and

palpation is resolved and the taut muscular band reducing myofascial pain.

released, with ensuing symptomatic pain relief.17

Various methods are used to deactivate TrPs, Methods

including ultrasound,18-20 pressure release,21;22 cold The study took place during the five month period

spray and stretch and injection of local from July to Dec 2001. Following Local Research

anaesthetic.4 Dry needling (no substance injected) Ethics Committee approval, subjects were recruited

may be carried out either superficially (SDN)23 or from patients with musculoskeletal pain, referred

with deeper insertion (DDN).24;25 for physiotherapy by five GPs at an inner city

Much discussion has ensued on the merits of Lancaster practice. A small pilot study of one

DDN and SDN, though research evidence on the subject per group preceded the trial. This was

latter is limited.26 An earlier study using SDN (to a useful for the clinicians to standardise algometry

depth of 4mm) on TrPs causing chronic low back techniques and test worthiness of forms for

pain, showed significant benefits for this method.27 recording measurements, to which minor

However study numbers were relatively small (8 adjustments were made. Inclusion criteria were:

SDN, 9 placebo TENS) and since electroacupuncture aged 18 and over; presence of active TrP

was introduced if no improvement was gained identifiable by a) spot tenderness in a taut

from SDN, it is impossible to assess the precise muscular band, b) subject recognition of pain on

effects of needling. A recent RCT comparing the palpation, c) painful limitation of affected

two methods demonstrated DDN to be muscle’s full range of movement, d) LTR, e) pain

significantly superior to SDN in reducing in expected distribution (a, b, c essential to

shoulder myofascial pain.28 This study combined inclusion; d and e not essential but used to

traditional acupuncture points with TrPs, using 13 confirm diagnosis); patient agrees not to receive

needles at each of eight sessions, therefore its additional treatment for their painful condition

conclusions may not equate with individual TrP during the trial (apart from NSAIDs and pain

ACUPUNCTURE IN MEDICINE 2003;21(3):80-86.

www.medical-acupuncture.co.uk/aimintro.htm 81

6419/37 AIM21(3) 30/9/03 3:02 PM Page 82

Downloaded from aim.bmj.com on July 19, 2012 - Published by group.bmj.com

Papers

killers); patient is capable of complying with the tube (4mm). If not secured into the skin, further

trial. Exclusion criteria were: acute condition gentle pressure was applied, fractionally

requiring treatment before six weeks; skin lesion, increasing penetration. The needle was not

infection or inflammatory oedema at TrP site; manipulated or stimulated and was left in situ until

needle phobia; previous adverse reaction to any sensations experienced by the patient,

acupuncture or anaesthetic; serious neurological following needle insertion, had subsided. The

or systemic disorder. Subjects were randomised duration of needle retention was recorded. The

into three groups by selection of numbers 1 to 3 in number of attendances over the three week

sealed brown envelopes, when a witness was treatment depended on the severity of condition

always present. Fourteen subjects were and patient / therapist convenience, as is normal

randomised into group 1 (G1) to receive physiotherapy practice.

superficial needling and active stretching exercise, Group 2

13 subjects to group 2 (G2) for stretching Patients received instruction in appropriate

exercise, and 13 into group 3 (G3) who were no stretching exercises, as recommended by Simons

treatment controls. et al, for involved muscle(s) containing TrPs.4;5

As with G1 patients they were asked to carry out

Clinical Assessment home exercises, repeating three stretches three

Subjects were given a full musculoskeletal times daily. The importance of relaxing muscles

physiotherapy assessment by JE, an experienced between stretches was stressed. Follow up

senior physiotherapist with training in TrP appointments were made to check / alter exercises

identification and a further two years’ clinical according to the condition.

experience. TrPs relevant to the patient’s pain Groups 1 and 2

complaint were identified by palpation and Both groups were advised on correction of

marked on a body chart, recording precise daytime or sleeping postures if contributing to TrP

measurements from bony landmarks if difficulties activation. Following the three weeks’ intervention,

in ongoing identification were anticipated. A both groups had no treatment for three weeks, but

maximum of six TrPs relevant to the condition continued with home regimes.

were included. In JE’s experience this number is Group 3

treatable in one session and allows for inclusion of Patients randomised to G3 received no treatment

satellite TrPs. The TrP most closely reproducing over the six week study period.

the patient’s pain on palpation was measured for

study purposes. Outcomes

Outcome measures were the Short Form McGill

Interventions Pain Questionnaire (SFMPQ) and pressure pain

Interventions were carried out by JE in the threshold (PPT). The SFMPQ included a visual

physiotherapy department attached to the practice. analogue scale (VAS),31 15 pain descriptors, and

Group 1 a 1 to 5 present pain intensity scale, together

Patients received a course of SDN to affected giving a total pain score. PPT of the primary TrP

TrPs, followed by appropriate stretching exercises was measured in kg/cm2, using a Fischer

to be continued at home. Exercises used were algometer (Pain Diagnostics and Thermography,

those recommended by Simons et al.4;5 TrPs New York). The TrP was identified by JE and

implicated in the condition were palpated and marked on the skin with a small pen mark. With

marked with a small dot on the skin at each the patient comfortably supported and relaxed

treatment session, then needled in turn, usually the algometer was applied directly over the TrP,

working from proximal to distal. Sterile stainless perpendicular to the body surface. Pressure was

steel acupuncture needles (25 x 0.30mm) with applied at the rate of 1kg/s and the patient was

coiled copper handles and plastic guide tubes were instructed to say ‘now’ when the feeling of

used (Helio Medical Supplies, Inc.). The needle pressure turned to pain. Three readings were

was inserted to the depth allowed by the guide taken, allowing 30 to 60 seconds between each,

ACUPUNCTURE IN MEDICINE 2003;21(3):80-86.

82 www.medical-acupuncture.co.uk/aimintro.htm

6419/37 AIM21(3) 30/9/03 3:02 PM Page 83

Downloaded from aim.bmj.com on July 19, 2012 - Published by group.bmj.com

Papers

the average being the final score. Measurement Data Analysis

took place at M1, pre-intervention; M2, after Data was analysed using SPSS Windows 10/11

three weeks of the interventions in G1 and G2, or programmes. Baseline characteristics of age,

three weeks with no treatment in G3; and M3 gender, pain duration, number and site of TrPs,

after a follow-up period of a further three weeks. were analysed using chi square or ANOVA tests to

Measurements were carried out blind by two detect any differences between groups. SFMPQ

trained observers, the surgery’s health care and PPT data were examined visually and found

assistant and a research assistant employed by to be reasonably normally distributed. Analysis

Morecambe Bay PCT. Both received prior was therefore carried out using parametric

training in use of the algometer. On some ANOVA and where this indicated significant

occasions neither assistant was available. This overall difference (p≥0.05) two sample t-tests

necessitated one of the authors (JE) taking 24% were performed. Ninety five percent confidence

of measurements. As the pre-treatment M1 intervals were compared for mean outcome per

measures were still blind to grouping, 9% of group and used to perform significance tests at the

measures were not blinded. At the end of the trial 5% level of significance. Pearson’s correlation

patients were asked if they required further coefficients between change in PPT and SFMPQ

treatment or physiotherapy for their condition. between M1 and M3 were calculated.

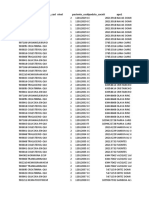

Table 1 Group baseline characteristics, mean and (standard deviation).

Needling and Stretch Stretch Untreated Controls

G1 G2 G3

N 14 13 13

Female % 71% 61% 76%

Age 57 (12) 55 (17) 57 (19)

Pain duration in months 16 (23) 10 (12) 16 (19)

No of TrPs involved 4.1 (1.2) 4.6 (1.1) 3.4 (1.6)

Upper body TrPs % 50% 84% 53%

Table 2 Mean SFMPQ and PPT scores at M1, M2 and M3.

Needling and Stretch Stretch Untreated Controls

G1 G2 G3

M1 M2 M3 M1 M2 M3 M1 M2 M3

SFMPQ Mean 24.3 13.0 9.1 23.1 17.1 15.2 20.2 16.5 14.9

(SD) (6.3) (10.2) (11.6) (7.0) (9.4) (8.8) (8.0) (10.2) (11.0)

PPT Mean 1.4 1.8 2.7 1.7 1.8 1.8 1.4 2.0 2.0

(SD) (0.9) (1.0) (1.4) (1.0) (1.1) (0.9) (1.0) (1.4) (1.6)

Table 3 Mean SFMPQ and PPT change scores at M2 and M3 with p values for inter group comparisons.

Needling and Stretch Stretch Untreated Controls

G1 G2 G3

M2-M1 M3-M1 M2-M1 M3-M1 M2-M1 M3-M1

SFMPQ Mean -11.2 -15.2 -6.0 -7.8 -3.7 -5.3

(SD) (11.3) (13.3) (7.0) (7.3) (7.6) (8.7)

p<0.10 vs. G2

p<0.05 vs. G3

PPT Mean +0.5 +1.3 +0.1 +0.1 +0.6 +0.5

(SD) (0.9) (1.0) (0.5) (0.6) (1.0) (1.3)

p<0.05 vs. G2

p<0.10 vs. G3

Two sample t-tests were performed where ANOVA indicated a significant overall difference, p values are p>0.05 unless

otherwise indicated.

ACUPUNCTURE IN MEDICINE 2003;21(3):80-86.

www.medical-acupuncture.co.uk/aimintro.htm 83

6419/37 AIM21(3) 30/9/03 3:02 PM Page 84

Downloaded from aim.bmj.com on July 19, 2012 - Published by group.bmj.com

Papers

Table 4 Treatment sessions during trial and further treatment.

G1 G2 G3

(n=14) (n=13) (n=13)

Mean number of treatment sessions during trial 4.6 2.9 0

Number of patients requiring treatment following trial 6 12 9

Results of physiotherapy on completion if required.

Sixty-six patients were assessed for TrPs. Of these Sixty per cent of patients examined for the trial

40 fulfilled the inclusion criteria and agreed to presented with myofascial pain caused by active

take part in the study. All patients completed the TrPs. Prior GP screening for non-musculoskeletal

trial. A total of 235 needle insertions were carried pain in the present study, could account for lower

out on G1 patients. The average number per session figures (30%) in Skootsky et al’s study, which

was 3.7 (max 5.2, min 2.3). The needles were examined 54 patients presenting with pain of 172

retained for an average of 3.4 minutes (max 4.8, consecutive patients at a primary care centre.1 Other

min 2.5), this time corresponded to the duration of baseline data compare favourably with Skootsky et

sensations experienced by the patient. Sixteen al, indicating a representative sample.

needles (7%) failed to produce any sensation. The study’s findings demonstrate no significant

Baseline characteristics (Table 1) showed no differences between groups after three weeks of

significant differences between groups. SFMPQ treatment (M2), but after a further three weeks

and PPT means at M1, M2 and M3 are shown in follow-up (M3) G1 showed significantly improved

Table 2. Mean change scores at M2 and M3, with SFMPQ scores compared to G3 and significantly

inter-group comparisons (Table 3), indicate no improved PPT scores compared to G2. This would

significant differences at M2. However, at M3, G1 seem to indicate that in the three week period

was significantly different compared to G3 in following treatment, G1 patients continued to

SFMPQ scores (p=0.043), and compared to G2 in improve compared to patients in G2 and G3. Mean

PPT scores (p=0.011). PPT and SFMPQ scores scores for SFMPQ and PPT (table 2) highlight this

correlated significantly (in the expected direction) finding, particularly PPT scores, showing no

only in G1, though no significant difference in improvement between M2 and M3 for G2 and G3.

correlation coefficients was found between the groups. It can be seen that G2 patients showed less

The mean number of treatment sessions was improvement overall in PPT, than the controls (table

lower for G2 (2.9) than for G1 (4.6) (Table 4). The 2), and considerably more patients in G2 required

number of patients requiring further treatment treatment at the end of the trial (table 4). This may

following the trial was considerably lower in G1 suggest that stretching alone has adverse effects on

(Table 4). No side effects following TrP needling TrP sensitivity, supporting Macdonald’s findings

were reported by patients, or observed by the that stretching muscles containing TrPs is more

therapist. There were no dropouts from the study. likely to produce pain than when muscles contract

isotonically as prime movers.16 PPT was not

Discussion measured in Macdonald’s study.

Studies assessing methods of TrP deactivation are Correlations between SFMPQ and PPT changes

often single interventions on one TrP, considering (M1 to M3) may also indicate that stretching

only immediate effects.18;19;24;32;33 It is accepted that without prior SDN increases TrP sensitivity. Only in

several TrPs are commonly affected and may G1 did the changes correlate significantly in the

require a course of treatment.4 Although only the expected direction (i.e. a decrease in SFMPQ

primary TrP was measured by algometry, the correlated with an increase in PPT). G2 scores

present study delivered a course of treatment to up showed least correlation (table 5). However, no

to six affected TrPs, over a three week period, significant difference in correlation coefficients

allowing a further three weeks for follow up was demonstrated between groups. Interestingly,

assessment. All patients completed the trial, which Jaeger and Reeves, treating upper trapezius and

may be due to its pragmatic approach and assurance levator scapulae TrPs with spray and stretch, found

ACUPUNCTURE IN MEDICINE 2003;21(3):80-86.

84 www.medical-acupuncture.co.uk/aimintro.htm

6419/37 AIM21(3) 30/9/03 3:02 PM Page 85

Downloaded from aim.bmj.com on July 19, 2012 - Published by group.bmj.com

Papers

Table 5 Analysis of SFMPQ (M3-M1) vs PPT (M3-M1).

G1 G2 G3

Correlation coefficient -0.67 -0.12 -0.37

95% confidence interval -0.89 to 0.22 -0.63 to +0.46 -0.77 to +0.23

p value 0.009 0.71 0.22

No significant difference in slopes (p=0.12).

no significant correlation between pain and PPT them. SDN is a relatively quick and pain free

scores, suggesting this was due to non treatment of method of TrP deactivation. It is thought to work by

other affected TrPs.34 needle prick stimulation of Aδ fibres inhibiting of C

Baseline characteristics affecting the TrP fibre pain through descending mechanisms and

sensitivity in G2 may be a higher incidence of upper dorsal horn interneurones.23 SDN inevitably causes

body TrPs (table 1), which have lower PPT scores less discomfort to recipients than DDN methods.24;25

than lower body TrPs, but this is not reflected in G2 There is also likely to be lower risk of traumatic side

scores at M1 (table 2).35 Average pain duration was effects, particularly in anticoagulated patients. Since

lower for G2 than G1 or G3 (table 1), which might patient safety and comfort should be prime

be expected to correlate with a better outcome.7;36 considerations in choice of needling therapy for

Although the treatment sessions in G2 were myofascial pain,29 SDN followed by active

significantly fewer than in G1 (table 4), which stretching is an appropriate treatment choice.

might be considered to result in reduced non- Physiotherapists and general practitioners

specific effects (therapeutic interaction and practising acupuncture are well placed to deliver

expectation), Hopwood and Abrams, analysing 193 this treatment, which if provided in a primary care

TrP injections, found that a successful outcome did setting, may well help prevent the development of

not correlate with the number of treatments.36 chronic pain and dysfunction.

PPT threshold measurements in this study

indicate that SDN is an effective method of Study Limitations

deactivating TrPs. The study would appear to show Greater numbers and longer term follow up would

that active TrPs require deactivation prior to have added weight to the study’s findings. As nine

stretching, with probable release of taut muscular percent of measurements were not blind to grouping,

bands and resolution of the energy crisis at motor it is possible that bias was introduced. However,

end plates.4 Stretching muscles without prior every effort was made to maintain impartiality, and

deactivation of the TrP, may reduce subjective pain, previous scores were concealed during

but seems to have minimal effect on TrP sensitivity measurements. In addition, if measures fell between

or overall resolution of the condition, as two scale indices (SFMPQ and PPT) the score in the

demonstrated in G2. Although PPT scores improved opposite direction to expected bias was recorded.

more in G1 than G3, this was not significant

(p<0.10), therefore no treatment was shown to be as Implications for Research

effective as SDN and stretch in reducing TrP Since this study used SDN together with stretch,

sensitivity. However, since SDN with stretch was more research is needed to evaluate the

significantly more effective in reducing pain scores effectiveness of SDN alone, and SDN compared

than no treatment, overall the study demonstrated with SDN and stretch. Also, the duration of TrP

greater benefits from SDN with stretch than either needling warrants further research.

stretching alone or no treatment.

This study indicates that significant numbers of Conclusion

patients with musculoskeletal pain referred by This study supports the hypothesis that SDN

general practitioners to physiotherapy departments followed by active stretching is more effective

may suffer from myofascial TrP pain. As TrPs are than stretching alone, or no treatment, in the

frequently located some distance from the pain, management of myofascial pain caused by active

skill and training are required in order to detect TrPs. Stretching alone, in some cases, may

ACUPUNCTURE IN MEDICINE 2003;21(3):80-86.

www.medical-acupuncture.co.uk/aimintro.htm 85

6419/37 AIM21(3) 30/9/03 3:02 PM Page 86

Downloaded from aim.bmj.com on July 19, 2012 - Published by group.bmj.com

Papers

increase TrP sensitivity, leading to delayed 17. Baldry PE. Acupuncture, trigger points & musculoskeletal

resolution. pain. 2nd ed. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone; 1993.

18. Hong C-Z, Chen Y-C, Pon C,Yu J. Immediate effects of

various physical modalities on pain threshold of active

Acknowledgements myofascial trigger points. J Musculoskele Pain 1993;1(2):37-53.

The authors wish to thank Chris Wright, School of 19. Lee J, Lin D, Hong C-Z .The effectiveness of simultaneous

Health and Social Sciences, Coventry University thermotherapy with ultrasound and electrotherapy with

combined AC and DC current on the immediate pain relief of

and Sally Hollis, Medical Statistics Unit,

myofascial trigger points. J Musculoskele Pain 1997;5(1):81-91.

Lancaster University, for guidance on statistical 20. Gam AN, Warming S, Larsen LH, Jensen B, Hoydalsmo O,

analysis, and Bob Charman for his comments on Allon I, et al. Treatment of myofascial trigger points with

the article. ultrasound combined with massage and exercise- a

randomised controlled trial. Pain 1998;77(1):73-9.

21. Hanten WP, Olson SL, Butts NL, Nowicki AL. Effectiveness

Reference list of a home program of ischemic pressure followed by

1. Skootsky SA, Jaeger B, Oye RK. Prevalence of myofascial sustained stretch for treatment of myofascial trigger points.

pain in general internal medicine practice. West J Med Phys Ther 2000;80(10):997-1003.

1989;151(2):157-60. 22. Simons DG. Understanding effective treatments of

2. Gerwin RD, Shannon S, Hong CZ, Hubbard D, Gevirtz R. myofascial trigger points. J Bodywork Mov Ther

Interrater reliability in myofascial trigger point examination. 2002;6(2):81-8.

Pain 1997;69(1-2):65-73. 23. Baldry PE. Superficial dry needling at myofascial trigger

3. Hsieh CY, Hong CZ, Adams AH, Platt KJ, Danielsen CD, point sites. J Musculoskele Pain 1995;3(3):117-26.

Hoehler FK, Tobis JS. Interexaminer reliability of the 24. Hong CZ. Lidocaine injection versus dry needling to

palpation of trigger points in the trunk and lower limb myofascial trigger point. The importance of the local

muscles. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2000;81(3):258-64. response. Am J Phys Med Rehabil 1994;73(4):256-63.

4. Simons DG, Travell JG, Simons PT. Travell & Simons' 25. Gunn CC. The Gunn Approach to the Treatment of Chronic

Myofascial Pain & Dysfunction. The Trigger Point Manual. Pain. New York: Churchill Livingstone 1996.

Volume 1. Upper Half of Body. 2nd ed. Baltimore: Williams 26. Baldry PE. Superficial versus deep dry needling. Acupunct

& Wilkins; 1999. Med 2002;20(2-3):78-81.

5. Travell JG, Simons DG. Myofascial Pain & Dysfunction. The 27. Macdonald AJ, Macrae KD, Master BR, Rubin AP.

Trigger Point Manual. Volume 2. The Lower Extremities. Superficial acupuncture in the relief of chronic low back

Baltimore: Williams & Wilkins; 1992. pain. Ann R Coll Surg Engl 1983;65(1):44-6.

6. Ingber RS. Iliopsoas myofascial dysfunction: a treatable 28. Ceccheerelli F, Bordin M, Gagliardi G, Caravello M.

cause of ‘failed’ low back syndrome. Arch Phys Med Rehabil Comparison between superficial and deep acupuncture in the

1989;70(5):382-6. treatment of the shoulder’s myofascial pain: a randomised

7. Hong C-Z, Simons DG. Response to treatment for pectoralis and controlled study. Acupunct Electrother Res

minor myofascial pain syndrome after whiplash. J 2001;26(4):229-38.

Musculoskele Pain 1993;1(1):89-131. 29. Cummings TM, White AR. Needling therapies in the

8. Ingram-Rice B. Carpal tunnel syndrome: more than a wrist management of myofascial trigger point pain: a systematic

problem. J Bodywork Mov Ther 1992;1(3):155-62. review. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2001;82(7):986-92.

9. Feinberg BI, Feinberg RA. Persistent pain after total knee 30. Hubbard DR. Persistent muscular pain: approaches to

arthroplasty: treatment with manual therapy and trigger point relieving trigger points. J Musculoskele Med 1998;15(5):16-26.

injections. J Muscoloskele Pain 1998;6(4):85-95. 31. Melzack R. The short form McGill Pain Questionnaire. Pain

10. Tay A, Chua K, Chan K-F. Upper quarter myofascial pain 1987;30(2):191-7.

syndrome in Singapore: Characteristics and treatment. J 32. Hsueh TC, Cheng PT, Kuan TS, Hong CZ. The immediate

Musculoskele Pain 2000;8(4):49-56. effectiveness of electrical nerve stimulation and electrical

11. Mense S. Nociception from skeletal muscle in relation to muscle stimulation on myofascial trigger points. Am J Phys

clinical muscle pain. Pain 1993;54(3):241-89. Med Rehabil 1997;76(6):471-6.

12. Russell J. Reliability of clinical assessment measures for 33. Hanten W, Barret M, Gillespie-Plesko M, Jump K, Olson S.

classification of myofascial pain syndrome. J Musculoskele Effects of active head retraction with retraction/ extension

Pain 1999;7(1-2):309-24. and occipital release on the pressure pain threshold of

13. Hubbard DR, Berkoff GM. Myofascial trigger points show cervical and scapular trigger points. Physiother Theory Pract

spontaneous needle EMG activity. Spine 1993;18(13):1803-7. 1997;13:285-91.

14. Simons D, Hong C-Z, Simons LS. Prevalence of spontaneous 34. Jaeger B, Reeves JL. Quantification of changes in myofascial

electrical activity at trigger spots and at control sites in rabbit trigger point sensitivity with the pressure algometer

skeletal muscle. J Musculoskele Pain 1995;3(1):35-48. following passive stretch. Pain 1986;27(2):203-10.

15. Ward AA. Spontaneous electrical activity at combined 35. Fischer AA. Pressure algometry over normal muscles.

acupuncture and myofascial trigger point sites. Acupunct Standard values, validity and reproducibility of pressure

Med 1996;14(2):75-9. threshold. Pain 1987;30(1):115-26.

16. Macdonald AJ. Abnormally tender muscle regions and 36. Hopwood MB, Abram SE. Factors associated with failure of

associated painful movements. Pain 1980;8(2):197-205. trigger point injections. Clin J Pain 1994;10(3):227-34.

ACUPUNCTURE IN MEDICINE 2003;21(3):80-86.

86 www.medical-acupuncture.co.uk/aimintro.htm

Downloaded from aim.bmj.com on July 19, 2012 - Published by group.bmj.com

Superficial dry needling and active

stretching in the treatment of myofascial

pain − a randomised controlled trial

Janet Edwards and Nicola Knowles

Acupunct Med 2003 21: 80-86

doi: 10.1136/aim.21.3.80

Updated information and services can be found at:

http://aim.bmj.com/content/21/3/80

These include:

References Article cited in:

http://aim.bmj.com/content/21/3/80#related-urls

Email alerting Receive free email alerts when new articles cite this article. Sign up in

service the box at the top right corner of the online article.

Notes

To request permissions go to:

http://group.bmj.com/group/rights-licensing/permissions

To order reprints go to:

http://journals.bmj.com/cgi/reprintform

To subscribe to BMJ go to:

http://group.bmj.com/subscribe/

You might also like

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5821)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1093)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (852)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (590)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (898)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (540)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (349)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (822)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (122)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (403)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- SAB HLTAAP001 Recognise Healthy Body SystemsDocument67 pagesSAB HLTAAP001 Recognise Healthy Body SystemsBbas T.95% (20)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- 1503 KJSDLJFLSDF X10Document219 pages1503 KJSDLJFLSDF X10Aaron WallaceNo ratings yet

- Cell Lab ReportDocument3 pagesCell Lab ReportJosé SuárezNo ratings yet

- Mock Test SeriesDocument3 pagesMock Test SeriesHumsafer ALiNo ratings yet

- Category A Agents 11Document31 pagesCategory A Agents 11Us ShortaNo ratings yet

- Question PaperDocument18 pagesQuestion PaperRajeshwari Srinivasan100% (1)

- BOOK - Advances in Land Remote Sensing PDFDocument499 pagesBOOK - Advances in Land Remote Sensing PDFViri100% (1)

- Bagaimana Petani Di Malaysia Mempunyai Pabrik PupukDocument14 pagesBagaimana Petani Di Malaysia Mempunyai Pabrik PupukShamNo ratings yet

- CV of Professor Henrik Hagberg, Centre For The Developing Brain, King's College LondonDocument2 pagesCV of Professor Henrik Hagberg, Centre For The Developing Brain, King's College LondonIsraelssonNo ratings yet

- Observing Chemical Changes: Purpose: MaterialDocument2 pagesObserving Chemical Changes: Purpose: Materialctremblaylcsd150No ratings yet

- 1.16509 BuiHongQuangetDocument25 pages1.16509 BuiHongQuangetNguyen Minh TrongNo ratings yet

- 3540660208Document223 pages3540660208Iswahyudi AlamsyahNo ratings yet

- Scientific Validation of Standardization of Narayana Chendrooram (Kannusamy Paramparai Vaithiyam) Through The Siddha and Modern TechniquesDocument12 pagesScientific Validation of Standardization of Narayana Chendrooram (Kannusamy Paramparai Vaithiyam) Through The Siddha and Modern TechniquesBala Kiran GaddamNo ratings yet

- Tce 3Document6 pagesTce 3Yasser Mahdi AbdelhamidNo ratings yet

- DAFTAR PUSTAKA - Docx2Document2 pagesDAFTAR PUSTAKA - Docx2AQ GhesTyNo ratings yet

- History 6Sem621History English HistoryandCulDocument207 pagesHistory 6Sem621History English HistoryandCul12nakulNo ratings yet

- ICSE Class 10 Biology 2003Document6 pagesICSE Class 10 Biology 2003SACHIDANANDA SNo ratings yet

- Learning Plan in Grade 7bakawanDocument2 pagesLearning Plan in Grade 7bakawanCaren Fangon TejanoNo ratings yet

- Peptide PresentationDocument21 pagesPeptide Presentationapi-366464825100% (1)

- Inflammation and Repair Wound HealingDocument29 pagesInflammation and Repair Wound Healingakshay dhootNo ratings yet

- Auxologic Categorization and Chronobiologic Specification For The Choice of Appropriate Orthodontic TreatmentDocument14 pagesAuxologic Categorization and Chronobiologic Specification For The Choice of Appropriate Orthodontic TreatmentSofia Huertas MartinezNo ratings yet

- Experiment LipidsDocument5 pagesExperiment LipidsSHAFIKANOR3661No ratings yet

- Plant ReproductionDocument31 pagesPlant ReproductionelezabethNo ratings yet

- Autosomal Dominant Polycystic Kidney DiseaseDocument11 pagesAutosomal Dominant Polycystic Kidney DiseaserutwickNo ratings yet

- Literature Review On Finger MilletDocument4 pagesLiterature Review On Finger Milletafmzbzdvuzfhlh100% (1)

- 1 TISSUES Online Teaching - REVISED 2021 AnaphyDocument38 pages1 TISSUES Online Teaching - REVISED 2021 AnaphySerendipity ParkNo ratings yet

- Rips Lebrija Mes de AbrilDocument240 pagesRips Lebrija Mes de AbrilNatalia PinillaNo ratings yet

- 09 Science Notes Ch05 Fundamental Unit of LifeDocument5 pages09 Science Notes Ch05 Fundamental Unit of Lifemunnithakur5285No ratings yet

- Envelope - Answer Key The Ebola Wars General Edition Answers PDF 5879456 Smithkeelin1234 Gmail ComDocument10 pagesEnvelope - Answer Key The Ebola Wars General Edition Answers PDF 5879456 Smithkeelin1234 Gmail ComKeelin smithNo ratings yet

- Quiz Lipids and LipoproteinsDocument9 pagesQuiz Lipids and LipoproteinsAllyah Ross DuqueNo ratings yet