Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Organization of American Historians

Organization of American Historians

Uploaded by

mongo_beti471Copyright:

Available Formats

You might also like

- White Money Black PowerDocument225 pagesWhite Money Black Powermongo_beti471No ratings yet

- I Dont Trust You Anymore Nina Simone Culture and Black Activism in The 1960sDocument32 pagesI Dont Trust You Anymore Nina Simone Culture and Black Activism in The 1960sSomething100% (1)

- Hillary Belzer - Words + Guitar: The Riot GRRRL Movement and Third-Wave FeminismDocument121 pagesHillary Belzer - Words + Guitar: The Riot GRRRL Movement and Third-Wave FeminismRiOt GaaNo ratings yet

- Race and The Myth of The Liberal Consensus Gary GerstleDocument9 pagesRace and The Myth of The Liberal Consensus Gary GerstleAlexandre Silva100% (1)

- Lost Prophet: The Life and Times of Bayard RustinFrom EverandLost Prophet: The Life and Times of Bayard RustinRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (19)

- Coronil Listening To The Subaltern The Poetics of Neocolonial StatesDocument17 pagesCoronil Listening To The Subaltern The Poetics of Neocolonial StatesPablo SantibañezNo ratings yet

- Aristocracy Assailed - The Ideology of Back Country AntiFederalistDocument26 pagesAristocracy Assailed - The Ideology of Back Country AntiFederalistM. C. Gallion Jr.0% (1)

- Korstad and Lichtenstein, Opportunities Found and Lost - Labor, Radicals, and The Early Civil Rights MovementDocument27 pagesKorstad and Lichtenstein, Opportunities Found and Lost - Labor, Radicals, and The Early Civil Rights MovementJeremyCohanNo ratings yet

- Bullet Holes in The Wall-The Dudley-A&T Student Revolt of May 1969 - 8-21-14Document19 pagesBullet Holes in The Wall-The Dudley-A&T Student Revolt of May 1969 - 8-21-14Beloved Community Center of Greensboro100% (1)

- American Civil RightsDocument32 pagesAmerican Civil RightsGabriela MitidieriNo ratings yet

- The Long Civil Rights Movement PDFDocument32 pagesThe Long Civil Rights Movement PDFNishanth AravetiNo ratings yet

- Organization of American HistoriansDocument37 pagesOrganization of American HistoriansalexNo ratings yet

- Daily Life of Women During The Civil Rights Era (PDFDrive)Document262 pagesDaily Life of Women During The Civil Rights Era (PDFDrive)Barrasford OpiyoNo ratings yet

- Kelly 2013Document23 pagesKelly 2013felipe delgado torresNo ratings yet

- Gale Researcher Guide for: Capital Punishment: History and ControversyFrom EverandGale Researcher Guide for: Capital Punishment: History and ControversyNo ratings yet

- Making History: The Struggle for Gay and Lesbian Equal Rights, 1945–1990From EverandMaking History: The Struggle for Gay and Lesbian Equal Rights, 1945–1990No ratings yet

- David Glassberg - Public History and The Study of MemoryDocument18 pagesDavid Glassberg - Public History and The Study of MemoryIrenarchNo ratings yet

- Alix Kates Shulman - Sex and Power Sexual Bases of Radical FeminismDocument16 pagesAlix Kates Shulman - Sex and Power Sexual Bases of Radical FeminismJanaína R100% (1)

- Alix Kates Shulman Sex and Power Sexual Bases of Radical Feminism PDFDocument16 pagesAlix Kates Shulman Sex and Power Sexual Bases of Radical Feminism PDFAlicia Hopkins100% (1)

- Alix Kates Shulman Sex and Power Sexual Bases of Radical Feminism PDFDocument16 pagesAlix Kates Shulman Sex and Power Sexual Bases of Radical Feminism PDFDaruku Amane Celsius100% (1)

- Alix Kates Shulman Sex and Power Sexual Bases of Radical Feminism PDFDocument16 pagesAlix Kates Shulman Sex and Power Sexual Bases of Radical Feminism PDFDaruku Amane Celsius100% (1)

- Biografía de Martin Luther King JRDocument7 pagesBiografía de Martin Luther King JRcjb03pt7100% (1)

- Of Light and Struggle: Social Justice, Human Rights, and Accountability in UruguayFrom EverandOf Light and Struggle: Social Justice, Human Rights, and Accountability in UruguayNo ratings yet

- Research Paper On Martin Luther King JRDocument4 pagesResearch Paper On Martin Luther King JRjzneaqwgf100% (1)

- Gilfoyle, Prostitutes in HistoryDocument26 pagesGilfoyle, Prostitutes in HistoryAna Carolina Gálvez ComandiniNo ratings yet

- Clawson and Trice - Poverty As We Know It: Media Portrayals of The PoorDocument13 pagesClawson and Trice - Poverty As We Know It: Media Portrayals of The PoorGiovanna PiccininoNo ratings yet

- Counterculture of 1960sDocument8 pagesCounterculture of 1960sapi-284386588No ratings yet

- PDF-A Zoot Suit Riots and The Role of The Zoot Suit in Chicano CultureDocument23 pagesPDF-A Zoot Suit Riots and The Role of The Zoot Suit in Chicano Cultured92kd93kccck49ck493100% (1)

- Bruce Jackson - Prison FolkloreDocument14 pagesBruce Jackson - Prison FolkloreMilutinRakovicNo ratings yet

- J. Damousi, Socialist Women and Gendered SpaceDocument16 pagesJ. Damousi, Socialist Women and Gendered SpaceFlorencia DuNo ratings yet

- Constructing The "Good Transsexual": Christine Jorgensen, Whiteness, and Heteronormativity in The Mid-Twentieth-Century PressDocument32 pagesConstructing The "Good Transsexual": Christine Jorgensen, Whiteness, and Heteronormativity in The Mid-Twentieth-Century PressArt DocsNo ratings yet

- 2010 Dittmer - Popular Culture, Geopolitics, and IdentityDocument204 pages2010 Dittmer - Popular Culture, Geopolitics, and IdentityLukacsMiNo ratings yet

- Civil Rights MovementDocument11 pagesCivil Rights MovementEllou Jean GerbolingoNo ratings yet

- Significant To Whom - GutierrezDocument22 pagesSignificant To Whom - GutierrezCarlos ReyesNo ratings yet

- Stonewall Riots DissertationDocument4 pagesStonewall Riots DissertationCustomWritingPaperServiceSingapore100% (1)

- I've Got the Light of Freedom: The Organizing Tradition and the Mississippi Freedom Struggle, With a New PrefaceFrom EverandI've Got the Light of Freedom: The Organizing Tradition and the Mississippi Freedom Struggle, With a New PrefaceRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (20)

- 1974, Wells A., The Coup D'etat in Theory and Practice - Independent Black Africa in The 1960sDocument18 pages1974, Wells A., The Coup D'etat in Theory and Practice - Independent Black Africa in The 1960sViacheslav AmelinNo ratings yet

- Gilfoyle 1999Document26 pagesGilfoyle 1999PRIMAVERA PAZ ACEVEDO AGUIRRENo ratings yet

- AnnLStolerTense Tender TiesDocument38 pagesAnnLStolerTense Tender TiesemilioreyesosorioNo ratings yet

- Howard ZinnDocument7 pagesHoward Zinn6500jmk4No ratings yet

- Public History and Public Memory (DIANE F. BRITTON)Document14 pagesPublic History and Public Memory (DIANE F. BRITTON)Juliana Sandoval AlvarezNo ratings yet

- Les Initiatives Visant À Célébrer Et À Promouvoir L'histoire Et La Culture Noires, Comme La Journée Nationale de L'histoire Noire Aux États-Unis PDFDocument3 pagesLes Initiatives Visant À Célébrer Et À Promouvoir L'histoire Et La Culture Noires, Comme La Journée Nationale de L'histoire Noire Aux États-Unis PDFHadrien CostaNo ratings yet

- John-DEmilio RLSC 14.4Document8 pagesJohn-DEmilio RLSC 14.4Alvaro del fresnoNo ratings yet

- Social Movements in American History ANSWER - EditedDocument7 pagesSocial Movements in American History ANSWER - EditedeliaswaliaulaNo ratings yet

- A History of GenderDocument12 pagesA History of Genderthesolomon100% (1)

- Thaddeus StevensDocument4 pagesThaddeus Stevenskurt_mordNo ratings yet

- Modern Feminism in The USADocument11 pagesModern Feminism in The USAshajiahNo ratings yet

- S. 1 SkidmoreDocument24 pagesS. 1 SkidmoreAngie Katherine Lozano BriñezNo ratings yet

- Wbiea1587 PDFDocument8 pagesWbiea1587 PDFWildan rafifNo ratings yet

- Springer: Springer Is Collaborating With JSTOR To Digitize, Preserve and Extend Access To Sociological ForumDocument22 pagesSpringer: Springer Is Collaborating With JSTOR To Digitize, Preserve and Extend Access To Sociological Forumrei377No ratings yet

- Thesis Statement I Have A Dream SpeechDocument8 pagesThesis Statement I Have A Dream Speechaflozmfxxranis100% (2)

- Black PanthersDocument27 pagesBlack Panthersjuan manuel hornosNo ratings yet

- S&S Quarterly, Inc. Guilford PressDocument33 pagesS&S Quarterly, Inc. Guilford PressMaría Mónica Sosa VásquezNo ratings yet

- Remembering ZinnDocument4 pagesRemembering ZinnDev OshanNo ratings yet

- Stephenson, 2002, Forging An Indigenous Counterpublic Sphere. The Taller de Historia Oral Andina in Bolivia PDFDocument21 pagesStephenson, 2002, Forging An Indigenous Counterpublic Sphere. The Taller de Historia Oral Andina in Bolivia PDFDomenico BrancaNo ratings yet

- "Uncontrolled Desires": The Response To The Sexual Psychopath, 1920-1960Document25 pages"Uncontrolled Desires": The Response To The Sexual Psychopath, 1920-1960ukladsil7020No ratings yet

- Popular Culture in May 3. in That Event, We Learned About The Origins of May Day, Its History, andDocument1 pagePopular Culture in May 3. in That Event, We Learned About The Origins of May Day, Its History, andLan ZhangNo ratings yet

- Fight The: Cuts and CronyismDocument11 pagesFight The: Cuts and Cronyismmongo_beti471No ratings yet

- The Cultural Politics of Shame in The English-Speaking WorldDocument4 pagesThe Cultural Politics of Shame in The English-Speaking Worldmongo_beti471No ratings yet

- Primary Sources - Archives Unbound - African America Communists and The National Negro Congress 1933 1947 PDFDocument2 pagesPrimary Sources - Archives Unbound - African America Communists and The National Negro Congress 1933 1947 PDFmongo_beti471No ratings yet

- Black Leadership MarableDocument259 pagesBlack Leadership Marablemongo_beti471100% (3)

- Reinventing The Color LineDocument27 pagesReinventing The Color Linemongo_beti471No ratings yet

- Black FeminismDocument52 pagesBlack Feminismmongo_beti471No ratings yet

- Popular Culture BuhleDocument19 pagesPopular Culture Buhlemongo_beti471No ratings yet

- Omi RaceDocument6 pagesOmi Racemongo_beti471No ratings yet

- Malcolm X and The Limits of AutobiographyDocument14 pagesMalcolm X and The Limits of Autobiographymongo_beti471No ratings yet

- Race and Class DawleyDocument10 pagesRace and Class Dawleymongo_beti471No ratings yet

- Writing The South Through AutobioDocument4 pagesWriting The South Through Autobiomongo_beti471No ratings yet

- Revolutionary Road Partial Victory Monthly ReviewDocument11 pagesRevolutionary Road Partial Victory Monthly Reviewmongo_beti471No ratings yet

- Livre T Black HistoriansDocument20 pagesLivre T Black Historiansmongo_beti471No ratings yet

- Hubert HarrisonDocument18 pagesHubert Harrisonmongo_beti471No ratings yet

- Liberator MagazineDocument14 pagesLiberator Magazinemongo_beti471100% (1)

- Siab-1 Discovery-OGDCL PDFDocument1 pageSiab-1 Discovery-OGDCL PDFEHTISHAM ABDUL REHMANNo ratings yet

- Family Law 1, Hindu LawDocument21 pagesFamily Law 1, Hindu Lawguru pratapNo ratings yet

- AS Units Revision Notes IAL EdexcelDocument10 pagesAS Units Revision Notes IAL EdexcelMahbub KhanNo ratings yet

- Valuation of StartupsDocument5 pagesValuation of Startupsomnifin.seoNo ratings yet

- Statement of Account: Date Narration Chq./Ref - No. Value DT Withdrawal Amt. Deposit Amt. Closing BalanceDocument34 pagesStatement of Account: Date Narration Chq./Ref - No. Value DT Withdrawal Amt. Deposit Amt. Closing BalanceMehndi HasanNo ratings yet

- List of Certified Workshop SarawakDocument48 pagesList of Certified Workshop SarawakIkhwan Firdausi SazaliNo ratings yet

- PD 1 of 2019Document11 pagesPD 1 of 2019terencebctanNo ratings yet

- Too Dear! - English NotesDocument7 pagesToo Dear! - English NotesikeaNo ratings yet

- BNA - Lalit DhanukaDocument11 pagesBNA - Lalit Dhanukavoxpopuli518No ratings yet

- Spa Cif DubaiDocument7 pagesSpa Cif DubaiJacob UnionNo ratings yet

- Vajiram and Ravi Prelims 2020 Test 1 QuestionsDocument27 pagesVajiram and Ravi Prelims 2020 Test 1 QuestionstriloksinghmeenaNo ratings yet

- Turn Over and Acceptance Ceremony June 30 2022Document2 pagesTurn Over and Acceptance Ceremony June 30 2022Mio LBPNo ratings yet

- List of Important Articles of The Indian Constitution - Notes, Tips, Tricks and Shortcuts For All Competitive ExamsDocument2 pagesList of Important Articles of The Indian Constitution - Notes, Tips, Tricks and Shortcuts For All Competitive ExamsBhuvnesh KhandelwalNo ratings yet

- Vol.11 Issue 9 June 30-July 6, 2018Document32 pagesVol.11 Issue 9 June 30-July 6, 2018Thesouthasian TimesNo ratings yet

- Albilad Credit Card Application-EnDocument6 pagesAlbilad Credit Card Application-EnHABEEB RAHMANNo ratings yet

- Chuck Peruto For DA Position PaperDocument9 pagesChuck Peruto For DA Position PaperPhiladelphiaMagazine100% (1)

- Book On The Order of ChivalryDocument40 pagesBook On The Order of ChivalryAnathema MaskNo ratings yet

- Electronically Filed Jan 04 2021 11:26 A.M. Elizabeth A. Brown Clerk of Supreme CourtDocument36 pagesElectronically Filed Jan 04 2021 11:26 A.M. Elizabeth A. Brown Clerk of Supreme CourtJannelle CalderonNo ratings yet

- Che Guevara Fundamentals of Guerrilla WarfareDocument35 pagesChe Guevara Fundamentals of Guerrilla WarfareFelix Geromo100% (1)

- DMC College Foundation, Inc. Sta. Filomena, Dipolog City 1 Semester 2018-2019 School of Business and AccountancyDocument1 pageDMC College Foundation, Inc. Sta. Filomena, Dipolog City 1 Semester 2018-2019 School of Business and AccountancyEarl Russell S PaulicanNo ratings yet

- Bloche Settlementagreementandrelease Ausexample 2 503 1929Document8 pagesBloche Settlementagreementandrelease Ausexample 2 503 1929ghilphilNo ratings yet

- Dineshkumar - 3INDIAN E-GOVERNANCESYSTEM: A VIEWDocument7 pagesDineshkumar - 3INDIAN E-GOVERNANCESYSTEM: A VIEWMURUGESAN MURUGESAN.RNo ratings yet

- Fil 12345Document2 pagesFil 12345vabsNo ratings yet

- Health Care Law Medical NegligenceDocument20 pagesHealth Care Law Medical NegligenceKunal MalikNo ratings yet

- Calendar of ActivitiesDocument2 pagesCalendar of ActivitiesGabriel-Fortunato EufracioNo ratings yet

- Con Law Simulation Elonis VDocument15 pagesCon Law Simulation Elonis Vapi-353466722No ratings yet

- Accounting Standards in The East Asia Region: By: M. Zubaidur RahmanDocument16 pagesAccounting Standards in The East Asia Region: By: M. Zubaidur Rahmanemerson deasisNo ratings yet

- Digital Marketing Company Dubai Best SEO Company in DubaiDocument2 pagesDigital Marketing Company Dubai Best SEO Company in Dubaileads dubaiNo ratings yet

- Final - Writ - Petition - For - Filing-PB Singh vs. State of MaharashtraDocument130 pagesFinal - Writ - Petition - For - Filing-PB Singh vs. State of MaharashtraRepublicNo ratings yet

- PDF High Performance Boards Improving and Energizing Your Governance 1St Edition Cossin Ebook Full ChapterDocument53 pagesPDF High Performance Boards Improving and Energizing Your Governance 1St Edition Cossin Ebook Full Chapterdebbie.mitchell437100% (2)

Organization of American Historians

Organization of American Historians

Uploaded by

mongo_beti471Original Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Organization of American Historians

Organization of American Historians

Uploaded by

mongo_beti471Copyright:

Available Formats

Beginnings and Endings: Life Stories and the Periodization of the Civil Rights Movement

Author(s): Kathryn L. Nasstrom

Source: The Journal of American History, Vol. 86, No. 2, Rethinking History and the Nation-

State: Mexico and the United States as a Case Study: A Special Issue (Sep., 1999), pp. 700-711

Published by: Organization of American Historians

Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/2567054 .

Accessed: 19/06/2013 06:21

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at .

http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp

.

JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of

content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms

of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org.

Organization of American Historians is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to

The Journal of American History.

http://www.jstor.org

This content downloaded from 195.221.71.48 on Wed, 19 Jun 2013 06:21:40 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Beginnings and Endings: Life Stories

and the Periodization of the

Civil Rights Movement

Kathryn L. Nasstrom

Overthe lastfifteenyears,historiansof the civilrightsmovementhavebeencharting

a new interpretivecourse.A nationallyorientednarrative,with a chronologycen-

teredon keyeventsin the life of Rev.MartinLutherKingJr.,hasgivenwayto a host

of stateandlocalstudies,with all the varietyone wouldexpectfromsucha turn.As

a result,manybasicquestionsarebeingrevisited,includingperiodization (Whendid

the movementbeginand end?),scope (Whatevents,actions,and issuesconstitute

the movement?), andpersonnelandleadership(Howdo we writea historyof activ-

ism andleadershipin a massmovement?).Often,thesequestionsrefractupon each

other.A narrativethat beginsin the 1930s, for example,will of necessityintro-

duce previouslyignoredactorsand events.To exploreany of thesequestionsis to

ask, as Adam Faircloughdid in a 1990 reviewessaythat still raisesmany timely

issues, "Whatwas the civil rights movement?"'This essay considersthis basic

question, and especiallythe matter of periodization,through the life history

methodof oralhistory.2The storytellingthatemergesfromoralhistorypracticeis

a narrativeact in which experienceis orderedand interpreted,and the life history

approach,which aims at a full narrationof personalhistory,leadsnaturallyto a

considerationof beginningsandendings.Implicitly,eachlife storyopensonto the

question of periodization.3

KathrynL. Nasstrom is assistantprofessorof history at the University of San Francisco.

'Adam Fairclough,"Stateof the Art: Historians and the Civil Rights Movement,"Journalof AmericanStudies,

24 (Dec. 1990), 387-98. Fairclough'sown work took this turn from national to local narrative;see Adam Fair-

clough, ToRedeemthe Soul of America:The SouthernChristianLeadershipConferenceand Martin LutherKingJr.

(Athens, 1987); and Adam Fairclough,Race and Democracy:The Civil RightsStrugglein Louisiana, 1915-1972

(Athens, 1995). A review essay used the Carlson series Martin Luther King Jr. and the Civil Rights Movement,

edited by David J. Garrow,as its jumping-off point to assessthe state of scholarshipas of the early 1990s: Steven F.

Lawson, "FreedomThen, FreedomNow: The Historiographyof the Civil Rights Movement,"AmericanHistorical

Review,96 (April 1991), 456-71.

2For a more general discussion of the value of oral history for studying the civil rights movement specifically,

and recent social movements more generally,see Bret Eynon, "Castupon the Shore: Oral History and New Schol-

arship on the Movements of the 1960s," Journal of American History, 83 (Sept. 1996), 560-70. See also the

review essay,Kim Lacy Rogers, "Oral History and the History of the Civil Rights Movement,"Journal of Ameri-

can History,75 (Sept. 1988), 567-76.

3For a discussion of the oral history interview as an interpretiveact, see Kim Lacy Rogers, "Memory,Struggle,

and Power:On InterviewingPoliticalActivists," OralHistoryReview,15 (Spring 1987), 165-84; and PeterFried-

700 The Journalof AmericanHistory September1999

This content downloaded from 195.221.71.48 on Wed, 19 Jun 2013 06:21:40 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Oral History 701

Over the last severalyears,I recordedthe life story of FrancesFreebornPauley,an

elderly,white, southern, female activist, and edited it for publication.These reflec-

tions on our joint endeavorfollow many happy months spent poring over the docu-

mentary recordand storytellingof a woman I admire tremendously.In particular,I

ponder that part of our collaborationover which I exertedthe most control, which

was to record the history of Frances'sactivism in the 1970s and 1980s, a subject

about which she had spoken little, although she had been interviewedmany times

before we began working together. Frances'snarration of these years provides a

record of civil rights activism that extended well into the supposedly post-civil

rightsera. Moreover,her storytellingsupportsseveralchronologiesof the movement

and encouragesa more nuanced interpretationof periodization. If Francesis any

indication, the life historiesof movement activistsmay be especiallyvaluableat this

particularjuncturein our writing of the history of the movement. In the dialogue of

oral history,the concernsof a new generationof scholarsand the experiencesof nar-

rators merge, allowing us to probe the relationship of the past and present. The

recordingof such historiesis still within our reachfor severalgenerationsof activists.

Frances,at age ninety-four, representsthe outer reachesof memory. By most mea-

sures (age, race,gender),she is also an atypicalfigurein the scholarshipon the move-

ment, and the conclusions her life story supports must be compared with many

others.The perspectivethat Frances,a southernwhite liberal,offerswould certainly

differ from that of a northern black nationalist, for example. Her distinctiveness,

however,affordsa certain advantage:she is unusual enough to offer a fresh vantage

point. I employ her here to pose questions and raiseinterpretivepossibilities.

FrancesPauley,born in 1905, grew up in the segregatedSouth and devoted her

life to the battle against discrimination and prejudice in the region. Her activist

careerspans five decades,from the 1930s to the late 1980s.4Francesfirst took up the

cause of social justice in the era of the Great Depression and New Deal; she helped

establishpublic health clinics for the indigent in DeKalb County, Georgia,immedi-

ately adjacentto Atlanta, and brought a hot lunch programto the county schools.

After World War II, she joined the Georgia League of Women Voters and for the

next fifteen years used the league to support racial desegregationand the broader

issues of democraticcitizenship raised by the civil rights movement. Then, caught

up in what she calls the "newmovement"of the 1960s, Frances,as executivedirector

of the Georgia Council on Human Relations, encouraged interracialorganizing,

lander, "Theory,Method, and Oral History,"in The Oral HistoryReader,ed. Robert Perksand AlistairThomson

(New York, 1998), 311 - 19. More generally,my analysisdrawson historicaland literarytheory of narrativestruc-

ture, particularlyas it relatesto the significanceof beginnings and endings. See William Cronon, "APlace for Sto-

ries: Nature, History, and Narrative,"Journal of AmericanHistory,78 (March 1992), 1347-76; Wallace Martin,

RecentTheoriesof Narrative (Ithaca, 1986), 81-100; Deborah E. McDowell, "In the First Place: Making Fred-

erick Douglass and the Afro-American Narrative Tradition," in Critical Essayson FrederickDouglass, ed. Wil-

liam L. Andrews (Boston, 1991), 192-214; and George Steinmetz, "Reflections on the Role of Social

Narratives in Working-Class Formation: Narrative Theory in the Social Sciences," Social Science History, 16

(Fall 1992), 489-516.

4On "careersof activism," see Kim Lacy Rogers, RighteousLives. Narrativesof the New OrleansCivil Rights

Movement(NewYork, 1993), 195-96.

This content downloaded from 195.221.71.48 on Wed, 19 Jun 2013 06:21:40 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

702 The Journalof AmericanHistory September1999

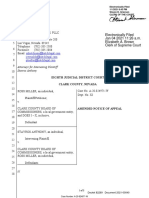

FrancesPauleyandLewisSinclairduringa demonstration at the Imperial

Hotel in downtownAtlanta.Advocatesfor the homelessoccupied

the abandonedhotelin June1990, to protestthe

housingin Atlanta.

lackof affordable

Courtesy

GladysRustay.

advocated enforcement of constitutional rights for African Americans, and, more

generally,championed improvement in the well-being of Georgia'sblacks. From

1968 to 1973, school desegregationconsumed most of her time and energy.As a

civil rights specialist for the United States Department of Health, Education, and

Welfare (HEW), Francesdeployed federal authority to move recalcitrantschool dis-

This content downloaded from 195.221.71.48 on Wed, 19 Jun 2013 06:21:40 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

OralHistory 703

tricts in the South into compliance with school desegregation regulations. She

retiredfrom the federalgovernmentin 1973 and turned her attention more exclu-

sively to poverty.In 1975, at the age of sixty-nine, she founded the GeorgiaPoverty

Rights Organization (GPRO) and coordinated its efforts with and on behalf of the

poor for over a decade.Even afterher "retirement"in the late 1980s, Francescontin-

ued to work, if less energetically,on poverty,homelessness,and gay rights.

Frances is also a consummate and generous storyteller.Scholars, students, and

community activists have found their way to her door for years, because she has

sharedher story so willingly.The result is over one thousand pages of oral history

transcripts(as well as severaluntranscribedtapes) from interviewsrecordedbetween

1974 and 1998, including the interviews that I conducted with Francesover the

four yearswe havebeen workingon this project.I approachedFrancesabout the possi-

bility of an oral history-based book in 1995, just as she turned ninety and at a point

when the onset of maculardegenerationhad diminished her eyesight significantly.

We can neverknow how Francesherself would have produceda book about her life,

but as she and I embarkedon our collaborationit was clear that our projectwould

be shaped largelyby my editorialchoices, although with her approval.

As I preparedfor my own interviews,I noticed that in previousinterviewsFrances

had not made more than passing remarksabout the last major phase of her activist

career,the povertyrightsyears.This omission was especiallystrikingbecauseher per-

sonal and professionalpapersin the SpecialCollections Department of Emory Uni-

versitycontain voluminous materialson the GPRO.5 That seriesin her papersis by far

the largestin the collection. Likewise,Franceshad devoted more of her activistyears

to the GPRO than to severalother of her majororganizationalaffiliations,such as the

GeorgiaCouncil on Human Relationsand HEW. I have puzzled over and worked on

that silence and its implications ever since, seeking both to understandit and to

overcomeit.

Why had Frances omitted from her storytelling the activities to which she

devoted her last extended energyand that were, if anything, a culmination of a life-

time of activism?The scope of earlierinterviews,determinedlargelyby the research

agenda of other scholars,provided part of the answer.Other interviewershad not

askedFrancesabout the GPRO, a pointed reminderfor me of just how much the oral

historiancan shape the historicalrecord.This was not, however,a sufficientexplana-

tion, as Franceson occasion set the agenda in her interviews.As I read through the

transcriptsof earlierinterviews,I noticed that she often did not allow an interviewer

to move on to a new subjectif an aspect of the currenttopic had been missed or not

5 FrancesFreebornPauley Papers(Special Collections Department, Robert W. Woodruff Library,Emory Uni-

versity,Atlanta, Georgia). FrancesPauleyinterview by JacquelynHall, July 18, 1974, transcription,Southern Oral

History Program Collection (Manuscripts Department, Southern Historical Collection, University of North

Carolina, Chapel Hill); Pauleyinterview by Cliff Kuhn, April 11, 1988, transcription,Georgia Government Doc-

umentation Project (Special Collections Department, Pullen Library,Georgia State University,Atlanta); Pauley

interview by Kuhn, May 3, 1988, transcription,ibid.; Pauley interview by Paul Mertz, Aug. 1, 1983, transcrip-

tion, PauleyPapers;Pauleyinterview by Mertz, June 10, 1988, transcription,ibid.; Pauley interview by LeneciaL.

Bruce, Sept. 20, 1983, transcription, League of Women Voters of DeKalb County (Georgia) Records (Special

Collections Department, Woodruff Library).

This content downloaded from 195.221.71.48 on Wed, 19 Jun 2013 06:21:40 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

704 TheJournalof AmericanHistory September1999

sufficientlyelaborated.Even more often, she would bring up subjectswithout being

asked.Finally,a particularlydistinctiveset of recordingsindicatedthat her silence on

the GPRO yearswas largelya matter of choice. Each year from 1987 to 1996, on the

occasion of her birthday,Francesspoke about her lifetime of activism to a small

audience at the Open Door Community, a residentialChristiancommunity serving

the homeless and hungry in Atlanta. Unlike the oral history material, which was

generated in the interview format, the Open Door material is more like a set of

speeches,albeit informallydelivered,before a familiarand congenial audience. Only

rarelydid Francesmention the GPRO years.6 Clearly,she had chosen not to talk about

a phase of her work that I found particularlyinteresting, and I wondered what

would happen when I embarkedon a line of questioning about those years.

When I approachedFrancesabout this matter,she did not object to my desireto

know more about the GPRO; she agreedthese were importantyearsand thought they

should be included in our book. We first worked to recordher history as a poverty

rights advocate in standardone-on-one interviews, but that process generatedvery

little detailed material,certainlynothing like the oral history documentation of her

earlieractivities,recordedwhen Frances'smemory and health were both better. Sev-

eral of Frances'sfamily members and friends helped me chart a different course.

Over time, a plan to involve others in recordingthe history of the GPRO evolved,and

I conducted a number of joint interviewswith Francesand other key people in the

GPRO.7Eventually,we generatedenough materialto make a chapteron the poverty

rights yearspossible. It is the last chapterof Frances'slife story,followed by a much

shorterchapter,in effect an epilogue, on her activitiesin retirement.

As I reflectedon this particularphase of our collaboration,from the vantagepoint

of having completed the book, I found myself contemplating the implications of

having added these last two decades of activism to her life story and therebyestab-

lishing a later ending point than she had previouslynarrated.I have come to appre-

ciate that severalchronologies of the civil rights movement inhere in Frances'slife

story, each one offering a different perspectiveon Francesand on key questions in

the history of the movement.

The first and narrowestchronologicalframeworkis the movement defined as the

decade of the sixties. This, in fact, is Frances'smost direct statement on the matter.

When asked by one interviewerwhat time period encompassedthe movement, she

replied, "to me that means pretty much the sixties."8In explainingits distinguishing

characteristics,Franceshas variouslycalled it a "new movement"and a "grass-roots

6 These recordingsare availablein the Pauley Papers.A portion of this materialis collected in Murphy Davis,

ed., FrancesPauley:Storiesof Struggleand Triumph,1996 (Open Door Community, Atlanta, Ga.).

7 Pauleyand Muriel Lokey interviewby Nasstrom,Jan. 23, 1997, transcription(in Nasstrom'spossession);Pauley

and Betsey Stone interview by Nasstrom, May 31, 1997, transcription (in Nasstrom's possession); Pauley and

Buren Batson interview by Nasstrom, June 11, 1997, transcription(in Nasstrom'spossession). These interviews

will be placed in the Pauley Papersfollowing publication of the book.

8 Pauley interviews by Albert McGovern, Feb. 1994 (in Pauley'spossession; used by permission). These inter-

views will be placed in the Pauley Papers following publication of the book. Throughout this essay, I use the

past tense to describe Frances'sactivities in the past and to identify singular comments she made during one

interview. I use the present tense for her ongoing storytelling and for those comments she has made on a num-

ber of occasions.

This content downloaded from 195.221.71.48 on Wed, 19 Jun 2013 06:21:40 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Oral History 705

movement," "coming up all over the United States, and particularlyall over the

South." "Certainleadersemerged,"she said, but she went on to emphasizethe mass

characterof strugglein the sixties:"Therewere a tremendousnumber of heroes and

heroines on a local level that really were the movement." (And, in a comment to

warm any oral historian'sheart, she added, "In fact, I wish that we could get a grant,

and let'sjust take Georgiaand see if we couldn'tget a list and a little account of what

differentpeople did in differenttowns. Becauseif we don't do it soon, it's going to

be forgotten.")Frances,for her part, traveledthe state of Georgia to organizeinter-

racialcouncils, worked closely with severalmajor civil rights organizations,negoti-

ated desegregation agreements with local officials, and occasionally faced down

mobs of angrywhite segregationists.Like many movement activists,Franceshas her

shareof dramaticstoriesof harassment,threats,and arrest,which she now tells with

relish. Often, however, she finds it difficult to put her experiencesinto words, as

when she describesthe mass meetings of the early 1960s in Albany,Georgia:

That singing was so tremendousthat now I get quite emotional sometimes when I

even hear some of the songs. I don't think that there'sany way of ever readingor

seeing on television or evergetting a realfeeling of what some of those mass meet-

ings were like, and some of that singing was like. Sometimes when I hear those

songs again, they'realmost hollow in comparison with the way they were when

those audiences sang them. It was something about that, the movement and the

feeling of the movement, that was just so compelling. I suppose that'sthe reason

that you alwaysstick with it and keep on trying to do something about it.

No other phase of her activist careerfeaturedsuch intense and extended activity in

the context of a powerfulmovement culture "thefeeling of the movement."This

combination of heightened individualand collectiveexperiencesets the sixties apart

as "themovement"for Frances.9

Despite these directstatements,Frances'sstorytellingsupportsalternateand wider

chronologicalframeworksfor the movement in which the sixties remainpivotal but

not so exclusivelyimportant. In the full body of her storytelling,the sixties take on

meaning in the context of a lifetime of activism begun in the 1930s. Franceshas

said, on many occasions,words to this effect: "The firstthing I ever rememberorga-

nizing was during the Depression."10From this point of origin, Francesnarratesa

bumpy, messy,but clearlydiscerniblestory of progressfrom the New Deal, through

the earlystages of the civil rights movement, with an emphasison voting rights and

desegregation,into the mass action, grass-rootsmovement of the sixties. As she

describes a transition from one phase of her activist career to the next, she also

sketchesthe developmentof a mass movement that broughtsignificantsocial change

to the South. For Frances, two forces made change possible: "good people" who

challenged prejudice and discrimination and a federal government that, when

pushed by these people, lent its clout to the cause of social justice. Francescame of

'All quotations in this paragraph,subsequent to the first, are taken from "Everybody's Grandmotherand

Nobody'sFool":TheLife Storyof FrancesFreebornPauley(Ithaca, forthcoming), chap. 4. In the notes that follow, I

cite the interview itself only in those instances in which a quotation does not appearin the book manuscript.

IO"Everybodys Grandmotherand NobodysFool,"chap. 3.

This content downloaded from 195.221.71.48 on Wed, 19 Jun 2013 06:21:40 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

706 TheJournalof AmericanHistory September1999

age politicallywith the New Deal, a time of vigoroussocial movementsand growing

public responsibilityfor social welfare, and the combination of citizen action and

government responsivenessremained for her a model approachto social problems.

The sixties, then, brought trendsbegun in the 1930s to fruition. In her storytelling,

Francesmost naturallyturns to the people and events of these yearsto representthe

significanceof her activist career.This tendency lends a certain timeless quality to

her storytelling,as she freezesthese moments in time and makes them speak for the

meaning of a life'swork. The effect is to suggest that the sixties were the last, best,

and most representativetimes. These yearstake on such force in storytellingnot sim-

ply because of the events of the decade but also because of the cumulativeweight

the decade bears.I consider this arc from the 1930s to the sixties to be the internal

periodization of the movement in Frances'sstorytelling. What comes after, the

1970s and 1980s, she is willing to narrate,but she does not naturallyincorporate

these yearsinto her storytelling.

That Francessimultaneouslyattachesgreat importanceto the sixties and contex-

tualizes that decade with referenceto her earlierhistory of activism makes her an

interestingfoil for other reminiscencesof the sixties. In some respects,Francesfits

neatly with a large group of activists for whom that decade remains, in memory,

exceedingly important. Much of the recent researchon the sixties was written by

participantsthemselves, and some of these works blend memoir with analysis.As

one scholarnoted recently,"The activistsof the [1960s] erakeep relivingtheir youth

by writing books about it, while their conservativeopponents . . . never tire of

invoking it as the root of all evil.""1Yet most of these participantsturned authors

were of the student generation, and the meaning of the sixties is debated most

fiercely by those, whether on the right or left, who cut their political teeth on the

social movements of the decade.The sixties are the standardby which they measure

everythingthat followed. Frances,who was in her fiftiesand sixties, not her twenties,

in these years, trains our sights in the opposite direction. She frames the sixties by

what came before.The life storiesof elderlyactivistsplace the sixties in a wider con-

text and thereby reveal the extent to which we have been under the generational

sway of student activistswhen assessingthe sixties. Yet Francestakes nothing away

from the mystique of the decade;indeed, she adds to it. When a pudgy, gray-haired,

white woman tells her stories of demonstrationsand arrest,it is harderto view the

activism of the sixties as solely the product of youthful idealism and rebellion.The

sixties can be freighted with just as much political and emotional weight if they

came toward the end, ratherthan the beginning, of an activist life. At this stage in

" MorrisDickstein quoted in William Dudley, ed., The 1960s: OpposingViewpoints(San Diego, 1997), 214. A

burst of scholarshipproduced by New Leftistsemerged in the mid- to late-I 980s. See Maurice Isserman,If I Had

a Hammer:TheDeath of the Old Leftand the Birth of the New Left (New York, 1987); James Miller, "Democracy Is

in the Streets":

FromPort Huron to the Siegeof Chicago(New York, 1987); Todd Gitlin, TheSixties:Yearsof Hope,

Days of Rage (New York, 1987); David Caute, The Yearof the Barricades:A Journeythrough1968 (New York,

1988); and Ronald Fraseret al., 1968: A StudentGenerationin Revolt(New York, 1988). More recently,revisionist

accounts have been produced, largely by a younger generation of scholars. For an excellent discussion of these

works, see Rick Perlstein,"Who Owns the Sixties?The Opening of a ScholarlyGeneration Gap," LinguaFranca,

6 (May/June 1996), 30-37.

This content downloaded from 195.221.71.48 on Wed, 19 Jun 2013 06:21:40 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Oral History 707

Fa eicurd.er

Pale,

arina.oleau

wt.Jm in e.....

. Geog.i. ey ..R.i.ghs .

....

:a2. ...x: z

...::.B.i - : i . ' : : :::: ::::'::.: ' .#i::: . ...::BE. .::: :B.:.:>:::S;.. 'B.:.

:':::i::B'.@

:

g.. . i;-..:............... ..'' 8 : . . :':

.............E':.:-::-:.

. :. i:.:E.:':.' : .:a - ^E.. E:E:S:N

:g.:'' 1''-_ z

g,~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~..,...... 2 . . .. .

Noticing g~~~~~~~~~ig~~~~~~~

...and.an. alyzing th ~,

. 8 ...B

internalperiodi.zat.i g

2.....

;.:S.Xa , .BB.

i.;;.

}..'.-... ..>

"as

2w

in F .race' storytellinghelped

mepinpoint, in turn, the implications my.ecsio.t of extend the frm.o.erlf

story alter

to icu th17sa

meaning

not olne

in .adde

any significant

Fanc.s.herself.ishes way 1theme 90.Hw g that c.on ,bto impart

I.did

about her he life. earlier

tionsto As Frances

activism, narrated .~

......._the Vshe

as when

commented.that.thepoor"werethe.ones

GPRO years for me, she made explicit connec-

............... ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ .

thge

haistrigrph maysof

the,,sixties,;

we, ler mor about tat ioaltm bok

.ip ..i......

t. u ...............ecson

n to e te d th fa e f e lf

stre

...r abu.........dth

. dead'

........H actvis.'

h ..... w ha e Ic a g d h o m c n e t n

meaning.... ......

Frncs' stry ..... soewyvr ite addcnet u i

not .le . ... ....

....n sig ifian .........esefmea in ihe t mp r

that hadn't

abou her

..... had a chance to have their

logical.

to... voices

try....

to..

........es narae........asfo heard.

......... So it just seemed

e h m d x lci o nc

earie

.. ......a

..her.....

..... hnse o m nedta h p o w reteoe

that hadn't had a chance see... to hve .............y.t

their voices heard. So itjust

get..o

.......

..ete

.n have

Iaesrnt the relz that the d n

....

12. thnstoTay .KMee orhlin eunesan rncssaciim nrlaintotestdn

generation........

getporpOpleniztiogetherRand

haventhem

rnealrtizethat thely didsthaovie

srntn

12orMy tankst toeTracya.d'eyer fo eligmeudrsadrnessatiiminrlaintotestdn

gNerticin. n nlzn h nenlproiaini rne' trtlighle

This content downloaded from 195.221.71.48 on Wed, 19 Jun 2013 06:21:40 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

708 TheJournalof AmericanHistory September1999

power."'3More generally,her descriptionsof the GPRO contain numerousparallelsto

her earlieractivism, rangingfrom the methods used to build povertyrights chapters

around the state to her returnto the extensivelegislativework that characterizedher

yearswith the Leagueof Women Voters.In short, when Francesansweredmy ques-

tions about the GPRO, she told a story organizedaroundcontinuity.Ratherthan gen-

erate a differentview of herself,she elaboratedthe essentialFrances,this time with

antipovertywork as the content. Reminiscencesamong the elderly often have this

quality;narrativesdeliveredin later life tend to bring on retrospection,summation,

and a definition of the whole.14 Franceshad been speakingretrospectivelyabout her

life since 1974, and her storytelling was well under way when I arrivedin 1995.

There is little reasonto believe that getting her to talk about one particularphase of

her life would generatea significantlydifferentsense of her life'swork.

In other ways, however,my addition of two decadesof activismdoes have conse-

quences, both for the view of Francesthat emergesand for the question of the peri-

odization of the civil rightsmovement.These derivefrom the laterending point that

I establishedfor her activist career.Whereas Francesmost naturallyends with the

1960s, when she was at her peak, my addition tracesthe winding down of a career,a

portraitof an aging activist in her seventies and eighties. For many people who are

familiarwith Frances'swork, myself included, these are especiallyremarkableyears,

because we know so little about activism in this age group. The longevity of her

careerwas what drew me to Francesin the first place. We became acquainted in

1991 when she was eighty-five, and one image of our first meeting remains fixed

in my mind: Frances'scar sported a bumper sticker-"Fight AIDS, Not People with

AIDS.'15 I rememberbeing impressedthat an eighty-plus-year-oldwoman was taking

a stand on AIDS (acquiredimmune deficiency syndrome). As I learned more about

Frances,I came to know that she was an activist who continually rose to the next

challenge, whether it was voting rights in the 1940s or homelessnessin the 1980s.

For Frances,however, her years in the GPRO held another meaning, signaled most

clearly by her tendency not to talk about them. The key to Frances'sreticence, I

believe, lies in the nature and timing of this work. Much of it verged on drudgery:

following bills through the legislature;buttonholing representativesto lobby for an

unpopular measure, usually one to benefit the poor; and constantly doing battle

with government bureaucracy.Franceshad worked on similar projectsfor decades,

but those tasks had previously been leavened by a strong dose of organizing, an

activity she enjoyed tremendously.With advancing age, Francestraveledthe state

13 Grandmotherand Nobody'sFool,"chap. 6.

"Everybodys

14On the synthesizing quality of memory and for an introduction to historical memory generally,see David

Thelen, "Memory and American History,"Journal of American History, 75 (March 1989), 1117-29. On life

review among the elderly, see Robert N. Butler, "The Life Review: An Interpretationof Reminiscence in the

Aged," Psychiatry,26 (Feb. 1963), 65-76; and Robert N. Butler, "The Life Review:An Unrecognized Bonanza,"

InternationalJournalof Aging and Human Development,12 (1980-1981), 35-46.

15Pauley interview by Nasstrom, Aug. 9, 1991, tape recording (in Nasstrom'spossession). I conducted this

interview as part of my dissertation research.See Kathryn L. Nasstrom, "Women, the Civil Rights Movement,

and the Politics of Historical Memory in Atlanta, 1946-1973" (Ph.D. diss., University of North Carolina at

Chapel Hill, 1993).

This content downloaded from 195.221.71.48 on Wed, 19 Jun 2013 06:21:40 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Oral History 709

less often to organizeGPRO chapters.Then, in the mid- to late 1980s, the impetus

for much of the organization'swork passed to other individuals. Letting go of the

GPRO was an admission that a life of activism was most definitely winding down.

Franceswrote to a good friend in 1986: "Totell you the truth, Paul, I am sick of the

whole thing. I think ten yearsis enough. A lot of people are picking up. If they can

carry it, O.K. If not, O.K., also.... If we had done better, the children of Georgia

wouldn'tbe so bad off today."'16 There is acceptancein these words, but a grudging

acceptance, and there is recognition of how much more needs to be done. As

Franceslooked about her in the mid-1980s-and today-the problems of poverty

and homelessnessweigh on her. She has not turned this information into stories, I

suspect, because it is still painful. As an activist she caresdeeply about these issues,

and as an elderlyperson she is frustratedby her inability to do much. In one inter-

view, she sighed, "Itwould be nice to be young again."'17 In her storytelling,Frances

constructs an activist self who always found a way to work around obstacles and

make a difference.She prefersto rememberherself,and be remembered,as she was

in the sixties, at her best.18

As I reflect now on the chapter on the GPRO years, I find parallels between

Frances'sstorytelling and her activism. Much as Franceshad let go of the GPRO in

the 1980s, she also relinquishedcontrol, ten years later, over narratingthose years,

by allowingme to recordmaterialshe had previouslyomitted and by allowing others

to determine, in part, how the history of the GPRO would come across.The text I

created is marked by the particularitiesof these circumstances.The form of the

chapteron the GPRO is quite differentfrom the others. It contains, not a first-person

narrative,but a conversationbetween Francesand friends. On severalmajor topics,

the narrativeis carriedless by Francesthan by these other interviewees.I originally

planned to pull out only Frances'swords from the joint interviews,but the ideas and

reminiscenceswere so deeply intertwined, as Francesand her friends traded stories

and prompted each other'smemories, that separatingone from the other was impos-

sible. Thus, late in the book and late in Frances'snarrationof her life story, the

readerencounters a significantly different form of storytelling. There is a certain

awkwardnessin this shift, but the form, which reflectsthe assistanceFrancesrequired

to narratethese years, capturesthe difficulty of both tasks: bringing a careerto a

close and then telling the story of its end. The form of the chapter,much more than

the content, conveys the emotional weight of the matter.

As the historianwho helped Francestell this story, and as a historian of the civil

rights movement, I am interestedin both the content and timing of this last phase

16FrancesPauley,"Historyof work on increasingbenefitsfor AFDC-as I rememberit" [addressedto PaulRilling],

Jan. 1, 1986, Pauley Papers.

17Pauleyand Stone interview.

181n a conversation with me on June 11, 1997, Murphy Davis of the Open Door Community helped me

understandthe difficulties Francesfaced in her last yearswith the GPRO. On life stories as constructions of self, see

Daphne Patai, "Introduction:Constructing a Self," in Brazilian WomenSpeak: ContemporaryLife Stories(New

Brunswick, 1988), 1-35; Rogers, RighteousLives; and Susan E. Chase and Colleen S. Bell, "Interpretingthe

Complexity of Women's Subjectivity,"in InteractiveOral HistoryInterviewing,ed. Eva M. McMahan and Kim

Lacy Rogers (Hillsdale, N.J., 1994), 63 - 8 1.

This content downloaded from 195.221.71.48 on Wed, 19 Jun 2013 06:21:40 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

710 TheJournalof AmericanHistory September1999

of her activist career,as they establishyet a third periodizationfor the civil rights

movement that reachesfrom the 1930s to the 1980s. In many ways, Frances'scivil

rights movement ended only with her retirementin the late 1980s. While scholars

of the movement have pushed back its origins into the 1930s and 1940s, very little

attention has been paid to the yearsafter 1970.19Both scholarlyand popularassess-

ments most often lament a movement in decline and disarray,especiallyfollowing

Martin LutherKing'sdeath in 1968. The life stories of activistswho worked beyond

the sixties will be criticalin telling a fuller story of these years, one that respectsthe

unique characterof the sixties ("thefeeling of the movement,"as Francessays) but

also recognizesongoing activism. In terms of content, the civil rights movement, as

framedby the entiretyof Frances'scareer,can be seen as beginning and ending with

advocacy for the poor: the public health clinics and school lunch programof the

1930s and the poverty rights organizingof the 1970s and 1980s. With the 1930s

and 1980s as anchor points, the centralityof poverty to her fifty-yearactivist career

comes into focus. Even as desegregationdominated the agenda of the Georgia

League of Women Voters during Frances'spresidency in the 1950s, the leaguealso

studiedthe state'swelfareprogramand advocatedfor the needs of welfarerecipientsin

Georgia.While she traveledthe state for the Georgia Council on Human Relations

in the 1960s, Francesalso establishedwelfarerightsgroupsin numerouscommunities.

The civil rights movement, seen through the trajectoriesof lifelong careers,may be

much more centrallyabout addressingthe needs of the poor than we have believed

to date, something that the extended arc of the 1930s to the 1980s makes it easier

to appreciate.

In the life story of FrancesFreebornPauleythat I assembled,these differentperi-

odizationscoexist and the overalleffect is one of layering.There is the chronologyof

Francesthe storyteller,who most naturallyends her story in the sixties, holding out

as an ideal the best of herself,the movement, and her government.And there is the

chronology of Francesthe activist,who began in the 1930s and continued to work

in remarkablysimilar ways into the 1980s. That Frances'slife story supports these

distinct but overlappinginterpretationsof the movement suggeststhat the question

of periodization is irreduciblycomplex. There is no single beginning nor ending

point, even for one person, much less an organization,a community, or the move-

19 For historians who emphasize a civil rights movement that began earlier than the 1950s and 1960s, see

Charles M. Payne, I've Got the Light of Freedom:The Organizing Traditionand the MississippiFreedomStruggle

(Berkeley, 1995); John Dittmer, Local People: The Strugglefor Civil Rights in Mississippi(Urbana, 1994); Fair-

clough, Race and Democracy;Robert Korstad and Nelson Lichtenstein, "Opportunities Found and Lost: Labor,

Radicals, and the Early Civil Rights Movement," Journal of AmericanHistory,75 (Dec. 1988), 786-811; and

Robert J. Norrell, Reapingthe Whirlwind:The Civil RightsMovementin Tuskegee(New York, 1985). For an argu-

ment that the movement spans the twentieth century, see August Meier, "Epilogue:Toward a Synthesis of Civil

Rights History,"in New Directionsin Civil RightsStudies,ed. Armstead L. Robinson and PatriciaSullivan (Char-

lottesville, 1991), 211-24. Most scholarsconclude their civil rights studies with events in the late 1960s or early

1970s, treating the later decades as an epilogue. See, for example, Robert Weisbrot, FreedomBound:A Historyof

AmericasCivil RightsMovement(New York, 1990). Studies that emphasize black political empowerment in rela-

tionship to the civil rights movement, such as Steven F. Lawson'sRunningforFreedom:Civil Rightsand BlackPoli-

tics in Americasince 1941 (New York, 1997), are more likely to push past the 1960s into the decades when black

officeholding increased. Charles Payne, whose study draws heavily on oral history and life histories, traces some

activist lives beyond the sixties in Payne, I've Got the Lightof Freedom.

This content downloaded from 195.221.71.48 on Wed, 19 Jun 2013 06:21:40 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Oral History 711

ment as a whole. We are urged instead to more subtle questions, open to multiple

beginnings and endings: When, why, and how did the movement draw in partici-

pants of varying backgrounds,and when, why, and how did they leave?How did

these individualsunderstandtheir involvementin the movement, at the time and in

memory?Which issues and eventswere defined at the time, and aredefined in retro-

spect, as part of the movement?To answer these questions, many life stories are

needed; Frances'sis one. The promise of the method lies in recording sufficient

numbersof life stories to createa mosaic of memory, to trace the contours of many

activistcareersover time, and therebyto write a history of the civil rightsmovement

rooted in life stories.

This content downloaded from 195.221.71.48 on Wed, 19 Jun 2013 06:21:40 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

You might also like

- White Money Black PowerDocument225 pagesWhite Money Black Powermongo_beti471No ratings yet

- I Dont Trust You Anymore Nina Simone Culture and Black Activism in The 1960sDocument32 pagesI Dont Trust You Anymore Nina Simone Culture and Black Activism in The 1960sSomething100% (1)

- Hillary Belzer - Words + Guitar: The Riot GRRRL Movement and Third-Wave FeminismDocument121 pagesHillary Belzer - Words + Guitar: The Riot GRRRL Movement and Third-Wave FeminismRiOt GaaNo ratings yet

- Race and The Myth of The Liberal Consensus Gary GerstleDocument9 pagesRace and The Myth of The Liberal Consensus Gary GerstleAlexandre Silva100% (1)

- Lost Prophet: The Life and Times of Bayard RustinFrom EverandLost Prophet: The Life and Times of Bayard RustinRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (19)

- Coronil Listening To The Subaltern The Poetics of Neocolonial StatesDocument17 pagesCoronil Listening To The Subaltern The Poetics of Neocolonial StatesPablo SantibañezNo ratings yet

- Aristocracy Assailed - The Ideology of Back Country AntiFederalistDocument26 pagesAristocracy Assailed - The Ideology of Back Country AntiFederalistM. C. Gallion Jr.0% (1)

- Korstad and Lichtenstein, Opportunities Found and Lost - Labor, Radicals, and The Early Civil Rights MovementDocument27 pagesKorstad and Lichtenstein, Opportunities Found and Lost - Labor, Radicals, and The Early Civil Rights MovementJeremyCohanNo ratings yet

- Bullet Holes in The Wall-The Dudley-A&T Student Revolt of May 1969 - 8-21-14Document19 pagesBullet Holes in The Wall-The Dudley-A&T Student Revolt of May 1969 - 8-21-14Beloved Community Center of Greensboro100% (1)

- American Civil RightsDocument32 pagesAmerican Civil RightsGabriela MitidieriNo ratings yet

- The Long Civil Rights Movement PDFDocument32 pagesThe Long Civil Rights Movement PDFNishanth AravetiNo ratings yet

- Organization of American HistoriansDocument37 pagesOrganization of American HistoriansalexNo ratings yet

- Daily Life of Women During The Civil Rights Era (PDFDrive)Document262 pagesDaily Life of Women During The Civil Rights Era (PDFDrive)Barrasford OpiyoNo ratings yet

- Kelly 2013Document23 pagesKelly 2013felipe delgado torresNo ratings yet

- Gale Researcher Guide for: Capital Punishment: History and ControversyFrom EverandGale Researcher Guide for: Capital Punishment: History and ControversyNo ratings yet

- Making History: The Struggle for Gay and Lesbian Equal Rights, 1945–1990From EverandMaking History: The Struggle for Gay and Lesbian Equal Rights, 1945–1990No ratings yet

- David Glassberg - Public History and The Study of MemoryDocument18 pagesDavid Glassberg - Public History and The Study of MemoryIrenarchNo ratings yet

- Alix Kates Shulman - Sex and Power Sexual Bases of Radical FeminismDocument16 pagesAlix Kates Shulman - Sex and Power Sexual Bases of Radical FeminismJanaína R100% (1)

- Alix Kates Shulman Sex and Power Sexual Bases of Radical Feminism PDFDocument16 pagesAlix Kates Shulman Sex and Power Sexual Bases of Radical Feminism PDFAlicia Hopkins100% (1)

- Alix Kates Shulman Sex and Power Sexual Bases of Radical Feminism PDFDocument16 pagesAlix Kates Shulman Sex and Power Sexual Bases of Radical Feminism PDFDaruku Amane Celsius100% (1)

- Alix Kates Shulman Sex and Power Sexual Bases of Radical Feminism PDFDocument16 pagesAlix Kates Shulman Sex and Power Sexual Bases of Radical Feminism PDFDaruku Amane Celsius100% (1)

- Biografía de Martin Luther King JRDocument7 pagesBiografía de Martin Luther King JRcjb03pt7100% (1)

- Of Light and Struggle: Social Justice, Human Rights, and Accountability in UruguayFrom EverandOf Light and Struggle: Social Justice, Human Rights, and Accountability in UruguayNo ratings yet

- Research Paper On Martin Luther King JRDocument4 pagesResearch Paper On Martin Luther King JRjzneaqwgf100% (1)

- Gilfoyle, Prostitutes in HistoryDocument26 pagesGilfoyle, Prostitutes in HistoryAna Carolina Gálvez ComandiniNo ratings yet

- Clawson and Trice - Poverty As We Know It: Media Portrayals of The PoorDocument13 pagesClawson and Trice - Poverty As We Know It: Media Portrayals of The PoorGiovanna PiccininoNo ratings yet

- Counterculture of 1960sDocument8 pagesCounterculture of 1960sapi-284386588No ratings yet

- PDF-A Zoot Suit Riots and The Role of The Zoot Suit in Chicano CultureDocument23 pagesPDF-A Zoot Suit Riots and The Role of The Zoot Suit in Chicano Cultured92kd93kccck49ck493100% (1)

- Bruce Jackson - Prison FolkloreDocument14 pagesBruce Jackson - Prison FolkloreMilutinRakovicNo ratings yet

- J. Damousi, Socialist Women and Gendered SpaceDocument16 pagesJ. Damousi, Socialist Women and Gendered SpaceFlorencia DuNo ratings yet

- Constructing The "Good Transsexual": Christine Jorgensen, Whiteness, and Heteronormativity in The Mid-Twentieth-Century PressDocument32 pagesConstructing The "Good Transsexual": Christine Jorgensen, Whiteness, and Heteronormativity in The Mid-Twentieth-Century PressArt DocsNo ratings yet

- 2010 Dittmer - Popular Culture, Geopolitics, and IdentityDocument204 pages2010 Dittmer - Popular Culture, Geopolitics, and IdentityLukacsMiNo ratings yet

- Civil Rights MovementDocument11 pagesCivil Rights MovementEllou Jean GerbolingoNo ratings yet

- Significant To Whom - GutierrezDocument22 pagesSignificant To Whom - GutierrezCarlos ReyesNo ratings yet

- Stonewall Riots DissertationDocument4 pagesStonewall Riots DissertationCustomWritingPaperServiceSingapore100% (1)

- I've Got the Light of Freedom: The Organizing Tradition and the Mississippi Freedom Struggle, With a New PrefaceFrom EverandI've Got the Light of Freedom: The Organizing Tradition and the Mississippi Freedom Struggle, With a New PrefaceRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (20)

- 1974, Wells A., The Coup D'etat in Theory and Practice - Independent Black Africa in The 1960sDocument18 pages1974, Wells A., The Coup D'etat in Theory and Practice - Independent Black Africa in The 1960sViacheslav AmelinNo ratings yet

- Gilfoyle 1999Document26 pagesGilfoyle 1999PRIMAVERA PAZ ACEVEDO AGUIRRENo ratings yet

- AnnLStolerTense Tender TiesDocument38 pagesAnnLStolerTense Tender TiesemilioreyesosorioNo ratings yet

- Howard ZinnDocument7 pagesHoward Zinn6500jmk4No ratings yet

- Public History and Public Memory (DIANE F. BRITTON)Document14 pagesPublic History and Public Memory (DIANE F. BRITTON)Juliana Sandoval AlvarezNo ratings yet

- Les Initiatives Visant À Célébrer Et À Promouvoir L'histoire Et La Culture Noires, Comme La Journée Nationale de L'histoire Noire Aux États-Unis PDFDocument3 pagesLes Initiatives Visant À Célébrer Et À Promouvoir L'histoire Et La Culture Noires, Comme La Journée Nationale de L'histoire Noire Aux États-Unis PDFHadrien CostaNo ratings yet

- John-DEmilio RLSC 14.4Document8 pagesJohn-DEmilio RLSC 14.4Alvaro del fresnoNo ratings yet

- Social Movements in American History ANSWER - EditedDocument7 pagesSocial Movements in American History ANSWER - EditedeliaswaliaulaNo ratings yet

- A History of GenderDocument12 pagesA History of Genderthesolomon100% (1)

- Thaddeus StevensDocument4 pagesThaddeus Stevenskurt_mordNo ratings yet

- Modern Feminism in The USADocument11 pagesModern Feminism in The USAshajiahNo ratings yet

- S. 1 SkidmoreDocument24 pagesS. 1 SkidmoreAngie Katherine Lozano BriñezNo ratings yet

- Wbiea1587 PDFDocument8 pagesWbiea1587 PDFWildan rafifNo ratings yet

- Springer: Springer Is Collaborating With JSTOR To Digitize, Preserve and Extend Access To Sociological ForumDocument22 pagesSpringer: Springer Is Collaborating With JSTOR To Digitize, Preserve and Extend Access To Sociological Forumrei377No ratings yet

- Thesis Statement I Have A Dream SpeechDocument8 pagesThesis Statement I Have A Dream Speechaflozmfxxranis100% (2)

- Black PanthersDocument27 pagesBlack Panthersjuan manuel hornosNo ratings yet

- S&S Quarterly, Inc. Guilford PressDocument33 pagesS&S Quarterly, Inc. Guilford PressMaría Mónica Sosa VásquezNo ratings yet

- Remembering ZinnDocument4 pagesRemembering ZinnDev OshanNo ratings yet

- Stephenson, 2002, Forging An Indigenous Counterpublic Sphere. The Taller de Historia Oral Andina in Bolivia PDFDocument21 pagesStephenson, 2002, Forging An Indigenous Counterpublic Sphere. The Taller de Historia Oral Andina in Bolivia PDFDomenico BrancaNo ratings yet

- "Uncontrolled Desires": The Response To The Sexual Psychopath, 1920-1960Document25 pages"Uncontrolled Desires": The Response To The Sexual Psychopath, 1920-1960ukladsil7020No ratings yet

- Popular Culture in May 3. in That Event, We Learned About The Origins of May Day, Its History, andDocument1 pagePopular Culture in May 3. in That Event, We Learned About The Origins of May Day, Its History, andLan ZhangNo ratings yet

- Fight The: Cuts and CronyismDocument11 pagesFight The: Cuts and Cronyismmongo_beti471No ratings yet

- The Cultural Politics of Shame in The English-Speaking WorldDocument4 pagesThe Cultural Politics of Shame in The English-Speaking Worldmongo_beti471No ratings yet

- Primary Sources - Archives Unbound - African America Communists and The National Negro Congress 1933 1947 PDFDocument2 pagesPrimary Sources - Archives Unbound - African America Communists and The National Negro Congress 1933 1947 PDFmongo_beti471No ratings yet

- Black Leadership MarableDocument259 pagesBlack Leadership Marablemongo_beti471100% (3)

- Reinventing The Color LineDocument27 pagesReinventing The Color Linemongo_beti471No ratings yet

- Black FeminismDocument52 pagesBlack Feminismmongo_beti471No ratings yet

- Popular Culture BuhleDocument19 pagesPopular Culture Buhlemongo_beti471No ratings yet

- Omi RaceDocument6 pagesOmi Racemongo_beti471No ratings yet

- Malcolm X and The Limits of AutobiographyDocument14 pagesMalcolm X and The Limits of Autobiographymongo_beti471No ratings yet

- Race and Class DawleyDocument10 pagesRace and Class Dawleymongo_beti471No ratings yet

- Writing The South Through AutobioDocument4 pagesWriting The South Through Autobiomongo_beti471No ratings yet

- Revolutionary Road Partial Victory Monthly ReviewDocument11 pagesRevolutionary Road Partial Victory Monthly Reviewmongo_beti471No ratings yet

- Livre T Black HistoriansDocument20 pagesLivre T Black Historiansmongo_beti471No ratings yet

- Hubert HarrisonDocument18 pagesHubert Harrisonmongo_beti471No ratings yet

- Liberator MagazineDocument14 pagesLiberator Magazinemongo_beti471100% (1)

- Siab-1 Discovery-OGDCL PDFDocument1 pageSiab-1 Discovery-OGDCL PDFEHTISHAM ABDUL REHMANNo ratings yet

- Family Law 1, Hindu LawDocument21 pagesFamily Law 1, Hindu Lawguru pratapNo ratings yet

- AS Units Revision Notes IAL EdexcelDocument10 pagesAS Units Revision Notes IAL EdexcelMahbub KhanNo ratings yet

- Valuation of StartupsDocument5 pagesValuation of Startupsomnifin.seoNo ratings yet

- Statement of Account: Date Narration Chq./Ref - No. Value DT Withdrawal Amt. Deposit Amt. Closing BalanceDocument34 pagesStatement of Account: Date Narration Chq./Ref - No. Value DT Withdrawal Amt. Deposit Amt. Closing BalanceMehndi HasanNo ratings yet

- List of Certified Workshop SarawakDocument48 pagesList of Certified Workshop SarawakIkhwan Firdausi SazaliNo ratings yet

- PD 1 of 2019Document11 pagesPD 1 of 2019terencebctanNo ratings yet

- Too Dear! - English NotesDocument7 pagesToo Dear! - English NotesikeaNo ratings yet

- BNA - Lalit DhanukaDocument11 pagesBNA - Lalit Dhanukavoxpopuli518No ratings yet

- Spa Cif DubaiDocument7 pagesSpa Cif DubaiJacob UnionNo ratings yet

- Vajiram and Ravi Prelims 2020 Test 1 QuestionsDocument27 pagesVajiram and Ravi Prelims 2020 Test 1 QuestionstriloksinghmeenaNo ratings yet

- Turn Over and Acceptance Ceremony June 30 2022Document2 pagesTurn Over and Acceptance Ceremony June 30 2022Mio LBPNo ratings yet

- List of Important Articles of The Indian Constitution - Notes, Tips, Tricks and Shortcuts For All Competitive ExamsDocument2 pagesList of Important Articles of The Indian Constitution - Notes, Tips, Tricks and Shortcuts For All Competitive ExamsBhuvnesh KhandelwalNo ratings yet

- Vol.11 Issue 9 June 30-July 6, 2018Document32 pagesVol.11 Issue 9 June 30-July 6, 2018Thesouthasian TimesNo ratings yet

- Albilad Credit Card Application-EnDocument6 pagesAlbilad Credit Card Application-EnHABEEB RAHMANNo ratings yet

- Chuck Peruto For DA Position PaperDocument9 pagesChuck Peruto For DA Position PaperPhiladelphiaMagazine100% (1)

- Book On The Order of ChivalryDocument40 pagesBook On The Order of ChivalryAnathema MaskNo ratings yet

- Electronically Filed Jan 04 2021 11:26 A.M. Elizabeth A. Brown Clerk of Supreme CourtDocument36 pagesElectronically Filed Jan 04 2021 11:26 A.M. Elizabeth A. Brown Clerk of Supreme CourtJannelle CalderonNo ratings yet

- Che Guevara Fundamentals of Guerrilla WarfareDocument35 pagesChe Guevara Fundamentals of Guerrilla WarfareFelix Geromo100% (1)

- DMC College Foundation, Inc. Sta. Filomena, Dipolog City 1 Semester 2018-2019 School of Business and AccountancyDocument1 pageDMC College Foundation, Inc. Sta. Filomena, Dipolog City 1 Semester 2018-2019 School of Business and AccountancyEarl Russell S PaulicanNo ratings yet

- Bloche Settlementagreementandrelease Ausexample 2 503 1929Document8 pagesBloche Settlementagreementandrelease Ausexample 2 503 1929ghilphilNo ratings yet

- Dineshkumar - 3INDIAN E-GOVERNANCESYSTEM: A VIEWDocument7 pagesDineshkumar - 3INDIAN E-GOVERNANCESYSTEM: A VIEWMURUGESAN MURUGESAN.RNo ratings yet

- Fil 12345Document2 pagesFil 12345vabsNo ratings yet

- Health Care Law Medical NegligenceDocument20 pagesHealth Care Law Medical NegligenceKunal MalikNo ratings yet

- Calendar of ActivitiesDocument2 pagesCalendar of ActivitiesGabriel-Fortunato EufracioNo ratings yet

- Con Law Simulation Elonis VDocument15 pagesCon Law Simulation Elonis Vapi-353466722No ratings yet

- Accounting Standards in The East Asia Region: By: M. Zubaidur RahmanDocument16 pagesAccounting Standards in The East Asia Region: By: M. Zubaidur Rahmanemerson deasisNo ratings yet

- Digital Marketing Company Dubai Best SEO Company in DubaiDocument2 pagesDigital Marketing Company Dubai Best SEO Company in Dubaileads dubaiNo ratings yet

- Final - Writ - Petition - For - Filing-PB Singh vs. State of MaharashtraDocument130 pagesFinal - Writ - Petition - For - Filing-PB Singh vs. State of MaharashtraRepublicNo ratings yet

- PDF High Performance Boards Improving and Energizing Your Governance 1St Edition Cossin Ebook Full ChapterDocument53 pagesPDF High Performance Boards Improving and Energizing Your Governance 1St Edition Cossin Ebook Full Chapterdebbie.mitchell437100% (2)