Professional Documents

Culture Documents

100%(1)100% found this document useful (1 vote)

262 viewsMIRZOEFF, Nicholas. What Is Visual Culture PDF

MIRZOEFF, Nicholas. What Is Visual Culture PDF

Uploaded by

Júlio SandesCopyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF or read online from Scribd

You might also like

- Citywide Implementation Strategies: The Draft Comprehensive Plan - Team Four, St. Louis, MODocument60 pagesCitywide Implementation Strategies: The Draft Comprehensive Plan - Team Four, St. Louis, MOnextSTL.com100% (1)

- Cable Connector Reference Chart PDFDocument1 pageCable Connector Reference Chart PDFNikolaNo ratings yet

- Susan J. Blackmore - Divination With Tarot Cards: An Empirical StudyDocument3 pagesSusan J. Blackmore - Divination With Tarot Cards: An Empirical StudySorrenne0% (1)

- AP 2002 Multiple Choice ExamDocument18 pagesAP 2002 Multiple Choice ExamJason FriedmanNo ratings yet

- The Gentlewoman PDFDocument17 pagesThe Gentlewoman PDFkirstyfruin75% (4)

- Durex BookletDocument14 pagesDurex BookletCarl GarrettNo ratings yet

- APB Statement No. 4Document3 pagesAPB Statement No. 4Dewi Sintala AnjaniNo ratings yet

- Jack Wills Brand BookDocument55 pagesJack Wills Brand BookSophie Mattacott-Cousins100% (1)

- Intro, Unthinking Eurocentrism PDFDocument7 pagesIntro, Unthinking Eurocentrism PDFyulypolskyNo ratings yet

- Chrono Trigger - The Perfect PDFDocument10 pagesChrono Trigger - The Perfect PDFopenid_yhzaHaxaNo ratings yet

- SpringboardDocument5 pagesSpringboardAlok ShenoyNo ratings yet

- Eisenstein - The Montage of Film Attractions (1924) in Eisenstein Reader Ed TaylorDocument10 pagesEisenstein - The Montage of Film Attractions (1924) in Eisenstein Reader Ed TaylorGert Jan HarkemaNo ratings yet

- Kelly Khumalo Charge SheetDocument5 pagesKelly Khumalo Charge SheeteNCA.comNo ratings yet

- Mx201 Mx312 SchematicsDocument7 pagesMx201 Mx312 SchematicsSteven GlassNo ratings yet

- A Theory of Buyer Behavior - JA Howard, JN Sheth 1969Document21 pagesA Theory of Buyer Behavior - JA Howard, JN Sheth 1969Nguyen Manh Quyen100% (1)

- Louisian 77Document51 pagesLouisian 77Benito de LeonNo ratings yet

- C. W. Mills The PromiseDocument12 pagesC. W. Mills The PromiseAT SuancoNo ratings yet

- Tazhir Prof. Zeev SternhellDocument13 pagesTazhir Prof. Zeev SternhellFreeSpeechIsraelNo ratings yet

- Nancy WetmoreDocument3 pagesNancy WetmoremtuccittoNo ratings yet

- 2007-05-04 Tim Ryan To U.S. Secretary of State Condoleeza RiceDocument2 pages2007-05-04 Tim Ryan To U.S. Secretary of State Condoleeza RiceCongressmanTimRyan100% (1)

- EPBM Papers+Document37 pagesEPBM Papers+Kapil Ashok Jaiswal80% (5)

- Case Study - When The Tail Wags The DogDocument2 pagesCase Study - When The Tail Wags The Dogruchit280950% (2)

- UwongoziDocument27 pagesUwongoziNati ManNo ratings yet

- Sample Test PaperDocument14 pagesSample Test PaperJuhi NathNo ratings yet

- Occupied Wall Street Journal, Issue 3Document4 pagesOccupied Wall Street Journal, Issue 3Daryl LangNo ratings yet

- Public Tenders and Auctions Law No. 23 (2007)Document30 pagesPublic Tenders and Auctions Law No. 23 (2007)Yemen Exposed100% (3)

- Iphone 7 Manual de ServiçoDocument82 pagesIphone 7 Manual de ServiçoHeli Filho100% (1)

- Chapter 10 - Marketing, Competition, CustomerDocument2 pagesChapter 10 - Marketing, Competition, CustomerShayna ButtNo ratings yet

- Kanzul Hasnain Fi Tahqeeq Yaumul Asnain by Hafiz Muhammad Ali AzamiDocument91 pagesKanzul Hasnain Fi Tahqeeq Yaumul Asnain by Hafiz Muhammad Ali AzamiTariq Mehmood TariqNo ratings yet

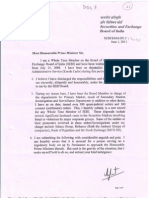

- Pranab Mukherjee Favours Reliance Industries, Sahara Group: SEBI Member Writes To PMDocument9 pagesPranab Mukherjee Favours Reliance Industries, Sahara Group: SEBI Member Writes To PMdharma nextNo ratings yet

- Birds-Animals Have Fundamental Right To Live FreelyDocument8 pagesBirds-Animals Have Fundamental Right To Live FreelyJayesh BhedaNo ratings yet

- Cumberland Metal Industries Enginered Product Division CaseDocument11 pagesCumberland Metal Industries Enginered Product Division Caseveda200% (1)

- Speaking in Tongues - Language Across Contexts and Users by Luis Pérez GonzálezDocument68 pagesSpeaking in Tongues - Language Across Contexts and Users by Luis Pérez GonzálezforonicaNo ratings yet

- MS NavisionDocument2 pagesMS NavisionVinay HegdeNo ratings yet

- Manual Voyager Vr-b1802vDocument43 pagesManual Voyager Vr-b1802vJuliano MachadoNo ratings yet

- Anna Nu PurviDocument9 pagesAnna Nu PurvisrmitkaryNo ratings yet

- Makatiba by Moulana Wakeel Ahmad SikandarpuriDocument17 pagesMakatiba by Moulana Wakeel Ahmad Sikandarpurisunnivoice100% (1)

- Introduction To Engineering Ethics - Chapter 8Document17 pagesIntroduction To Engineering Ethics - Chapter 8Fazal Aziz WaliNo ratings yet

- Mineral Exploration Agreement Between The Republic of Liberia and Liberty Gold and Diamond Mining Inc.Document29 pagesMineral Exploration Agreement Between The Republic of Liberia and Liberty Gold and Diamond Mining Inc.LiberiaEITINo ratings yet

- Sri Mahalakshmi Ammal TrustDocument2 pagesSri Mahalakshmi Ammal TrustMahesh KrishnamoorthyNo ratings yet

- Da Paikar e Noor Pashto by Sharaf QadriDocument26 pagesDa Paikar e Noor Pashto by Sharaf QadriTariq Mehmood TariqNo ratings yet

- Rude Brothers Manufacturing Company Catalog, 1890s - IncompleteDocument16 pagesRude Brothers Manufacturing Company Catalog, 1890s - IncompleteSpecial Collections and University Archives, Iowa State University LibraryNo ratings yet

- Speed Centre Rotterdam CatalogusDocument59 pagesSpeed Centre Rotterdam CatalogusRaymond van der HamNo ratings yet

- UGC On Specification of Degrees July 2014Document18 pagesUGC On Specification of Degrees July 2014Bar & BenchNo ratings yet

- Saab 105Document3 pagesSaab 105dagger21No ratings yet

- ABA-PGT Plastic GearsDocument141 pagesABA-PGT Plastic GearsAnthony Kelley100% (2)

- NDTV Narayan RaoDocument3 pagesNDTV Narayan RaoMoneylife FoundationNo ratings yet

- Zine Human Nature Barrier To SocialismDocument11 pagesZine Human Nature Barrier To SocialismAya Dela Peña100% (2)

- Radmila Graovac Teo - For.Document139 pagesRadmila Graovac Teo - For.JovanaČajovićNo ratings yet

- Laney BC50Document2 pagesLaney BC50doc_nebula100% (1)

- Affirmation - Acoustic GuitarDocument2 pagesAffirmation - Acoustic Guitarparzival D100% (1)

- PDF Parts Catalog Tvs Rockz - CompressDocument104 pagesPDF Parts Catalog Tvs Rockz - CompressaspareteNo ratings yet

- 09 - Chapter 1Document20 pages09 - Chapter 1Dr. POONAM KAUSHALNo ratings yet

- Tema 6. CULTURADocument7 pagesTema 6. CULTURAMarinaNo ratings yet

- Ampacidad AlimentacionDocument1 pageAmpacidad Alimentacionluis miguel sanchez estrellaNo ratings yet

- Si Tu Supieras - Trumpet 1Document3 pagesSi Tu Supieras - Trumpet 1Jose Boggiano AudiovisualesNo ratings yet

- Economía Michael Parkin 8e Cap 1Document16 pagesEconomía Michael Parkin 8e Cap 1lismaryNo ratings yet

- ElvisDocument1 pageElvismaui3No ratings yet

- b12r SpecificationsDocument2 pagesb12r SpecificationsPaul TemboNo ratings yet

MIRZOEFF, Nicholas. What Is Visual Culture PDF

MIRZOEFF, Nicholas. What Is Visual Culture PDF

Uploaded by

Júlio Sandes100%(1)100% found this document useful (1 vote)

262 views11 pagesOriginal Title

MIRZOEFF, Nicholas. What is visual culture.pdf

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

PDF or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF or read online from Scribd

Download as pdf

100%(1)100% found this document useful (1 vote)

262 views11 pagesMIRZOEFF, Nicholas. What Is Visual Culture PDF

MIRZOEFF, Nicholas. What Is Visual Culture PDF

Uploaded by

Júlio SandesCopyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF or read online from Scribd

Download as pdf

You are on page 1of 11

Chapter 1

Nicholas Mirzoeff

WHAT IS VISUAL CULTURE?!

EEING IS A GREAT DEAL MORE than believing these days. You can buy a

photograph of your house taken from an orbiting satellite or have your internal

organs magnetically imaged. If that special moment didn't come out quite right in

your photography, you can digitally manipulate it on your computer. At New

York's Empire State Building, the queues are longer for the virtual reality

New York Ride than for the lifts to the observation platforms, Alternatively, you

could save yourself the trouble by catching the entire New York skyline, rendered

in attractive pastel colours, at the New York, New York resort in Las Vegas. This

virtual city will be joined shortly by Paris Las Vegas, imitating the already care-

fully manipulated image of the city of light. Life in this alter-reality is sometimes

more pleasant than the real thing, sometimes worse. In 1997 same-sex marriage

was outlawed by the United States Congress but when the sitcom character Ellen

came out on television, 42 million people watched. On the other hand, virtual

reality has long been favoured by the military as a training arena, put into prac-

tice in the Gulf War at great cost of human life, This is visual culture. It is not

just a part of your everyday life, it is your everyday life.

Understandably, this newly visual existence can be confusing. For observing

the new visuality of culture is not the same as understanding it. Indeed, the gap

between the wealth of visual experience in contemporary culture and the ability

to analyse that observation marks both the opportunity and the need for visual

culture as a field of study. Visual culture is concerned with visual events in which

information, meaning or pleasure is sought by the consumer in an interface with

visual technology. By Tal tecincTogys Tear a fogy, Tmean any form of apparatus designed

“Sither to be Tooked at oF to enhance natural vision, from oll painting to televisjon

amd the Internet, Such criticism Res account oF the mportan aR of image making,

the Tormal components of a given image, and the crucial completion of that work

by its cultural reception.

4 NICHOLAS MIRZOEFF

This volume offers a selection of the best critical and historical work in the

past decade that has both created and developed the new field. It is a little different

to some other Readers currently in circulation. As the field is still so fluid and

subject to debate, it is as much an attempt to define the subject as to present a

commonly agreed array of topics. As a result, it does not simply offer latest

‘cutting-edge’ (i.e. most recent) material, but a mixture of new writing and a

reprise of the best pioneering work that has given rise to this field, an under:

standing of which is often assumed by current literature. After digesting this Reader,

you will be ready to plunge into the critical maelstrom and equipped to deal with

the unceasing flow of images from the swirl of the global village

Postmodernism is visual culture

Postmodernism has often been defined as the crisis of modernism, that is to say,

the wide-ranging complex of ideas and modes of representation ranging from over-

arching beliefs in progress to theories of the rise of abstract painting or the modern

novel. Now these means of representation no longer seem convincing without any

alternative having emerged. As a result, the dominant postmodern style is ironic:

a knowing pastiche that finds comment and critique to be the only means of inno-

vation. The postmodern reprise of modernism involves everything from the rash

of classical motifs on shopping malls to the crisis of modern painting and the popu-

larity of Nickelodeon repeats. In the context of this book, the postmoder is the

lern

crisis caused by modernism ture confronting the failure of its own

Sieg oiling other words, itis the visual crisis of culture that creates

0

posmmodemity, not its textuaity, While print culture is certainly not going to

ARappear, the Tascination with the visual and its effects that was a key feature of

modernism has engendered a postmodern culture that is at its most postmodern

when itis visual

During this volume’s compilation, visual culture has gone from being a useful

phrase for people working in art history, film and media studies, sociology and

other aspects of the visual to a fashionable, if controversial, new means of doing

interdisciplinary work, following in the footsteps of such fields as cultural studies,

queer theory and African-American studies, The reason most often advanced for

this heightened visibility is that human experience is now more visual and visual-

ized than ever before. In many ways, people in industrialized and post-industrial

societies now live in visual cultures to an extent that seems to divide the present

from the past. Popular journalism constantly remarks on digital imagery in cinema,

the advent of post-photography and developments in medical imaging, not to

mention the endless tide of comment devoted to the Internet. This globalization

of the visual, taken collectively, demands new means of interpretation, At the

same time, this transformation of the postmodern present also requires a rewriting

of historical explanations of modernism and modernity in order to account for ‘the

visual turn’,

Postmodernism is not, of course, simply a visual experience, In what Arjun

Appadurai has called the ‘complex, overlapping, disjunctive order’ of postmod-

crnism, such tidiness is not to be expected (Appadurai 1990). Nor can it be found

WHAT IS VISUAL CULTURE? 5

in past epochs, whether one looks at the eighteenth-century coffee-house public

ccalture celebrated by Jirgen Habermas, or the nineteenth-century print capitalism

of newspapers and publishing described by Benedict Anderson. In the same way

that these authors highlighted one particular characteristic of a period as a means

to analyse it, despite the vast range of alternatives, visual culture is a tactic with

which to study the genealogy, definition and functions of postmodern everyday

life, ‘The disjunctured and fragmented culture that we call postmodernism is best

ragined and understood visually, just as the nineteenth century was classically

represented in the newspaper atid the novel

Western culture has consistently privileged the spoken word as the highest

form of intellectual practice and seen visual representations as second-rate illus

trations of ideas. Now, however, the emergence of visual culture as a subject has

Contested this hegemony, developing what W.].T. Mitchell has called “picture

theory". In this view, Western philosophy and science now use a pictorial, rather

than textual, model of the world, marking a significant challenge to the notion of

the world a¢ a written text that dominated so much intellectual discussion in the

wake of such linguistics-based movements as structuralism and poststructuralism,

In Mitchell's view, picture theory stems from

the realization that spectatorship (the look, the gaze, the glance, the prac-

tices of observation, surveillance and visual pleasure) may be as deep

a problem as various forms of reading (decipherment, decoding, inter-

pretation, etc,) and that “visual experience’ or ‘visual literacy’ might

not be fully explicable in the model of textuality

(Mitchell 1994: 16)

While those already working on or with visual media. might find such remarks

sather patronizing, they are a measure of the extent to which even literary stuies

Ive been forced to conclude that the world-as-a-text has been challenged by the

workd-as-a-picture. Such world pictures cannot be purely visual, but by the same

wren, the visual disrupts and challenges any attempt t0 define culture in purely

linguistic terms.

“That is not to suggest, however, that a simple dividing line can be drawn

hewween the past (mover) and the present (postmodern). As Geoffrey Batchen

far argued, “the threatened dissolution of boundaries and! oppositions [the post

mnovdern} is presumed to represent # not something peculiar to a particular

Trehnolagy ot to postmodern discourse but i rather one ofthe fundamental cond

tions of modernity itself” (Batchen 1996: 28). Understood in this fashion, visual

tltare hos a history that needs exploring and defining in the modern as well as

pestmodem period. However, many current uses of the term have suffered from

PeNMgwenees that makes x hitle more than a buzzword. For some etites, visual

culture is

sentation (Bryson, Holly and Moxey 1994: xsi), This definition creates a body of

sel ao teat that no-one person or cven department could ever cover the field

ranerthers it iv a means of creating a sociology of visual culture that wil estab-

Tish a “social theory of visuality’ (Jenks 1995: 1). This approach seems open to the

al independence from the other senses that

‘imply ‘the history of images” handled with a semiotic notion of repre

charge that the visual is given an ar

You might also like

- Citywide Implementation Strategies: The Draft Comprehensive Plan - Team Four, St. Louis, MODocument60 pagesCitywide Implementation Strategies: The Draft Comprehensive Plan - Team Four, St. Louis, MOnextSTL.com100% (1)

- Cable Connector Reference Chart PDFDocument1 pageCable Connector Reference Chart PDFNikolaNo ratings yet

- Susan J. Blackmore - Divination With Tarot Cards: An Empirical StudyDocument3 pagesSusan J. Blackmore - Divination With Tarot Cards: An Empirical StudySorrenne0% (1)

- AP 2002 Multiple Choice ExamDocument18 pagesAP 2002 Multiple Choice ExamJason FriedmanNo ratings yet

- The Gentlewoman PDFDocument17 pagesThe Gentlewoman PDFkirstyfruin75% (4)

- Durex BookletDocument14 pagesDurex BookletCarl GarrettNo ratings yet

- APB Statement No. 4Document3 pagesAPB Statement No. 4Dewi Sintala AnjaniNo ratings yet

- Jack Wills Brand BookDocument55 pagesJack Wills Brand BookSophie Mattacott-Cousins100% (1)

- Intro, Unthinking Eurocentrism PDFDocument7 pagesIntro, Unthinking Eurocentrism PDFyulypolskyNo ratings yet

- Chrono Trigger - The Perfect PDFDocument10 pagesChrono Trigger - The Perfect PDFopenid_yhzaHaxaNo ratings yet

- SpringboardDocument5 pagesSpringboardAlok ShenoyNo ratings yet

- Eisenstein - The Montage of Film Attractions (1924) in Eisenstein Reader Ed TaylorDocument10 pagesEisenstein - The Montage of Film Attractions (1924) in Eisenstein Reader Ed TaylorGert Jan HarkemaNo ratings yet

- Kelly Khumalo Charge SheetDocument5 pagesKelly Khumalo Charge SheeteNCA.comNo ratings yet

- Mx201 Mx312 SchematicsDocument7 pagesMx201 Mx312 SchematicsSteven GlassNo ratings yet

- A Theory of Buyer Behavior - JA Howard, JN Sheth 1969Document21 pagesA Theory of Buyer Behavior - JA Howard, JN Sheth 1969Nguyen Manh Quyen100% (1)

- Louisian 77Document51 pagesLouisian 77Benito de LeonNo ratings yet

- C. W. Mills The PromiseDocument12 pagesC. W. Mills The PromiseAT SuancoNo ratings yet

- Tazhir Prof. Zeev SternhellDocument13 pagesTazhir Prof. Zeev SternhellFreeSpeechIsraelNo ratings yet

- Nancy WetmoreDocument3 pagesNancy WetmoremtuccittoNo ratings yet

- 2007-05-04 Tim Ryan To U.S. Secretary of State Condoleeza RiceDocument2 pages2007-05-04 Tim Ryan To U.S. Secretary of State Condoleeza RiceCongressmanTimRyan100% (1)

- EPBM Papers+Document37 pagesEPBM Papers+Kapil Ashok Jaiswal80% (5)

- Case Study - When The Tail Wags The DogDocument2 pagesCase Study - When The Tail Wags The Dogruchit280950% (2)

- UwongoziDocument27 pagesUwongoziNati ManNo ratings yet

- Sample Test PaperDocument14 pagesSample Test PaperJuhi NathNo ratings yet

- Occupied Wall Street Journal, Issue 3Document4 pagesOccupied Wall Street Journal, Issue 3Daryl LangNo ratings yet

- Public Tenders and Auctions Law No. 23 (2007)Document30 pagesPublic Tenders and Auctions Law No. 23 (2007)Yemen Exposed100% (3)

- Iphone 7 Manual de ServiçoDocument82 pagesIphone 7 Manual de ServiçoHeli Filho100% (1)

- Chapter 10 - Marketing, Competition, CustomerDocument2 pagesChapter 10 - Marketing, Competition, CustomerShayna ButtNo ratings yet

- Kanzul Hasnain Fi Tahqeeq Yaumul Asnain by Hafiz Muhammad Ali AzamiDocument91 pagesKanzul Hasnain Fi Tahqeeq Yaumul Asnain by Hafiz Muhammad Ali AzamiTariq Mehmood TariqNo ratings yet

- Pranab Mukherjee Favours Reliance Industries, Sahara Group: SEBI Member Writes To PMDocument9 pagesPranab Mukherjee Favours Reliance Industries, Sahara Group: SEBI Member Writes To PMdharma nextNo ratings yet

- Birds-Animals Have Fundamental Right To Live FreelyDocument8 pagesBirds-Animals Have Fundamental Right To Live FreelyJayesh BhedaNo ratings yet

- Cumberland Metal Industries Enginered Product Division CaseDocument11 pagesCumberland Metal Industries Enginered Product Division Caseveda200% (1)

- Speaking in Tongues - Language Across Contexts and Users by Luis Pérez GonzálezDocument68 pagesSpeaking in Tongues - Language Across Contexts and Users by Luis Pérez GonzálezforonicaNo ratings yet

- MS NavisionDocument2 pagesMS NavisionVinay HegdeNo ratings yet

- Manual Voyager Vr-b1802vDocument43 pagesManual Voyager Vr-b1802vJuliano MachadoNo ratings yet

- Anna Nu PurviDocument9 pagesAnna Nu PurvisrmitkaryNo ratings yet

- Makatiba by Moulana Wakeel Ahmad SikandarpuriDocument17 pagesMakatiba by Moulana Wakeel Ahmad Sikandarpurisunnivoice100% (1)

- Introduction To Engineering Ethics - Chapter 8Document17 pagesIntroduction To Engineering Ethics - Chapter 8Fazal Aziz WaliNo ratings yet

- Mineral Exploration Agreement Between The Republic of Liberia and Liberty Gold and Diamond Mining Inc.Document29 pagesMineral Exploration Agreement Between The Republic of Liberia and Liberty Gold and Diamond Mining Inc.LiberiaEITINo ratings yet

- Sri Mahalakshmi Ammal TrustDocument2 pagesSri Mahalakshmi Ammal TrustMahesh KrishnamoorthyNo ratings yet

- Da Paikar e Noor Pashto by Sharaf QadriDocument26 pagesDa Paikar e Noor Pashto by Sharaf QadriTariq Mehmood TariqNo ratings yet

- Rude Brothers Manufacturing Company Catalog, 1890s - IncompleteDocument16 pagesRude Brothers Manufacturing Company Catalog, 1890s - IncompleteSpecial Collections and University Archives, Iowa State University LibraryNo ratings yet

- Speed Centre Rotterdam CatalogusDocument59 pagesSpeed Centre Rotterdam CatalogusRaymond van der HamNo ratings yet

- UGC On Specification of Degrees July 2014Document18 pagesUGC On Specification of Degrees July 2014Bar & BenchNo ratings yet

- Saab 105Document3 pagesSaab 105dagger21No ratings yet

- ABA-PGT Plastic GearsDocument141 pagesABA-PGT Plastic GearsAnthony Kelley100% (2)

- NDTV Narayan RaoDocument3 pagesNDTV Narayan RaoMoneylife FoundationNo ratings yet

- Zine Human Nature Barrier To SocialismDocument11 pagesZine Human Nature Barrier To SocialismAya Dela Peña100% (2)

- Radmila Graovac Teo - For.Document139 pagesRadmila Graovac Teo - For.JovanaČajovićNo ratings yet

- Laney BC50Document2 pagesLaney BC50doc_nebula100% (1)

- Affirmation - Acoustic GuitarDocument2 pagesAffirmation - Acoustic Guitarparzival D100% (1)

- PDF Parts Catalog Tvs Rockz - CompressDocument104 pagesPDF Parts Catalog Tvs Rockz - CompressaspareteNo ratings yet

- 09 - Chapter 1Document20 pages09 - Chapter 1Dr. POONAM KAUSHALNo ratings yet

- Tema 6. CULTURADocument7 pagesTema 6. CULTURAMarinaNo ratings yet

- Ampacidad AlimentacionDocument1 pageAmpacidad Alimentacionluis miguel sanchez estrellaNo ratings yet

- Si Tu Supieras - Trumpet 1Document3 pagesSi Tu Supieras - Trumpet 1Jose Boggiano AudiovisualesNo ratings yet

- Economía Michael Parkin 8e Cap 1Document16 pagesEconomía Michael Parkin 8e Cap 1lismaryNo ratings yet

- ElvisDocument1 pageElvismaui3No ratings yet

- b12r SpecificationsDocument2 pagesb12r SpecificationsPaul TemboNo ratings yet