Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Irrigation

Irrigation

Uploaded by

buultoOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Irrigation

Irrigation

Uploaded by

buultoCopyright:

Available Formats

See

discussions, stats, and author profiles for this publication at:

https://www.researchgate.net/publication/249751339

Rescaling Irrigation in Latin

America: The Cultural Images and

Political Ecology of Water Resources

Article in Ecumene · April 2000

DOI: 10.1191/096746000701556680

CITATIONS READS

60 139

1 author:

Karl S. Zimmerer

Pennsylvania State University

98 PUBLICATIONS 2,342 CITATIONS

SEE PROFILE

Available from: Karl S. Zimmerer

Retrieved on: 17 July 2016

RESCALING IRRIGATION IN LATIN

AMERICA: THE CULTURAL IMAGES

AND POLITICAL ECOLOGY OF

WATER RESOURCES

Karl S. Zimmerer

A pair of scales – local canal-based (or village-based) and basin-scale (or valley-wide) – is

featured in the irrigation of the mountain landscapes of Latin America. These scales arose

historically through the interplay of cultural images with the political ecologies of agrarian

transformation. In the Cochabamba region of Bolivia, long the irrigated breadbasket of the

south-central Andes, the Inca state (c. 1495–1539) imposed canal-based irrigation using a

powerful concept of rotational sharing (suyu). Valley basins containing local irrigation were

a part of the territorial web of Inca state geography known later as verticality. The Spanish

empire in Andean South America (1539–1825) was predicated upon a valley-centric colonial

geography. Colonial rescaling involved despoliation and usurpation of waterworks, legal

actions, and struggles over environmental change. Influence of the two irrigation scales has

persisted. Today canal-based irrigation is not a timeless relict of indigenous customs, pace

many postcolonial projects. Rather its usefulness, and its remarkable reinvention as a cul-

tural concept and environmental creation, are the products of major modifications.

Dismantling of multi-scale linkages in irrigation has reduced indigenous or peasant cross-

scale co-ordination. Local containment poses threats to the environmental and socio-

economic sustainability of canal-based irrigation.

G eographical images of distinct scales support the widespread utilization and

continued expansion of irrigated landscapes for farming in Latin America.

Planners, farmers and aid officials have relied primarily on a pair of mental pic-

tures to guide the making of irrigation works. One image is focused on the orga-

nization of water resources at the local scale. Local irrigation refers to

community-based or village-based management, which often is coordinated

along a main canal. Many local, canal-based irrigation works are called juntas,

although such indigenous names as suyus and ceques are used avidly in western

South America (Peru, Bolivia). Local irrigation in Latin America is widely pro-

moted by development projects that are identified as ‘grassroots’, ‘local’, and

Ecumene 2000 7 (2) 0967-4608(00)EU187OA © 2000 Arnold

Rescaling irrigation in Latin America 151

‘sustainable’. During the past 10–15 years the image of local canal- or commu-

nity-based irrigation has been widely diffused, including in major irrigation areas

such as the Guadalajara-Querétaro region of Mexico, the Colca valley region of

Peru, and the Cochabamba region of Bolivia.1 Rights to canal-based irrigation

are often managed by a community or water users’ group, while the creation of

water markets is increasingly common in these arrangements.

A second mental picture is that of irrigated landscapes at the scale of the

basin or valley bottom. Basin irrigation typically is based on the centralized con-

trol of several primary canals that cover a larger area than single canal-based

waterworks. The basin image, like that of local canal-based irrigation, has been

used as a mental guide, although the actual forms of basin irrigation have usu-

ally differed somewhat from the ideal type. Fee arrangements and water mar-

kets are typical of this type of irrigation. Development projects offering this style

of irrigation warrant the labels of western, modern and global. The manage-

ment of water resources at the scale of basins (and closely related units like sub-

basins and multiple basins) has been characteristic of modern development in

Latin America. Project sites for the basin-scale management of water resources

include the Guadalajara–Querétaro region of Mexico (for example, the Santiago

and Autlan basins), the Colca valley region of Peru (the Majes sub-basin), and

the Cochabamba region of Bolivia (the Central Valley basin).2

This study considers how local canal-based and valley-basin irrigation were

shaped by the combined processes of social conflict and co-operation, political

contestation and consolidation, and human environmental change. Irrigation

geographies are taken to comprise both cultural pictures and material ecologi-

cal and social constructs. Of special interest is how interconnected mental and

socio-environmental processes have produced the distinct scaling of irrigation.

I focus on the making of irrigated landscapes in the Andean countries of west-

ern South America during the rule of this world region by paramount world

powers, with special reference to the Inca state (c. 1400–1532) and the early

Spanish colonial empire (1532–1650). I argue that a multi-faceted series of strug-

gles and temporary resolutions led to the rescaling of irrigation between the

1400s and the 1600s. At that time the twin images of irrigation – local canal-

based and basin scale – acquired an influence that has persisted with modifica-

tion until today.

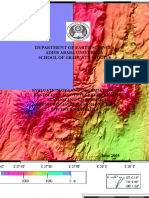

The location of my case study of irrigated landscapes and scale is the greater

Cochabamba region of central Bolivia (Figure 1). This so-called ‘heartland’ of

Bolivia is a tropical highland region of the Andes mountains that occupies inter-

mediate elevations between the westerly high Altiplano and the Andean pied-

mont and Amazon lowlands to the east. The environments of central Bolivia and

the Cochabamba region consist of scattered mountain basins at 2000–3000 m.

and extensive upland settings. Long one of the most irrigated regions of South

America, Cochabamba served under the Inca state and then the early Spanish

colonial empire as the famed bread-basket of the south-central Andes. During

these periods the irrigators and administrative rulers drew on a variety of men-

tal images, ecological functions, and social organizations. Among the scales of

irrigation the most salient were the local canal-based scale and the scale of the

Ecumene 2000 7 (2)

152 Karl S. Zimmerer

Ri

Uca

0 200

Ri M a mor

yal

NORTH

i

Ri

Miles

Lima Huancayo

Uru b a mba

e

os

Di

Huancavelica R i Madre D e

Ayacucho BRAZIL

en i

Ri

Ri B

Cuzco

Vi

ca

l

no

ta Lla Trinidad

PA C I F I C PERU nos

Lago de

Titicaca

de Mojos

OCEAN Ri

G

Puno BOLIVIA

ra

nd

e

Arequipa La Paz

Cochabamba Cetral

CentralValley

Valley Cochabamba

Santa Cruz

Tarata High Valley

Arica Oruro

Cliza Bañados

Ba del

ados del

Oruro Mizque Sucre

Ri

Ca Izozog

Izozog

ine Potosi

Aiquile Salar de

Lago see inset

de Uyuni

Ri

Poop

Pi

Ri PilcomaySucre

Tarija

lco

o

aym

o

Potosi

Antofagasta PA R A G U AY

ARGENTINA

Inset of Central Bolivia

CHILE

San Salvador

de Jujuy

Figure 1 ~ The central and south-central Andes of Peru and Bolivia. (The inset map

shows central Bolivia and the greater Cochabamba region.) During Inca rule (c.

1425–1532) the areas on the main map were the state territories of Collasuyu and

Antisuyu. Under the Spanish empire (c. 1532–1825) the areas shown here belonged to

the Alto Peru (‘High Peru’) subdivision of the Peruvian viceroyalty.

valley basin. As will be seen, the past scaling of irrigation under the Inca and

early Spanish world powers has been taken up in subsequent designs for irri-

gated agriculture and, most recently, in its joining with environmental conser-

vation.

Geographical scale and political ecology

The theme of scale is crucial to my study. I reject the a priori distinctions of

canal-based irrigation as purely local and basin-style irrigation as purely global.

Rather than a simple and fixed dichotomy of local–global, the making of irri-

gation is expected to involve a variety of key pheonomena – social actors and

practices, cultural ideas, political processes, environmental factors and flows –

that take place at several scales. Equally important, the relations of these

causative phenomena across scales suggest the linkages of different identifiable

scales. This insight, presented in the second section, leads my case study to scale

up and scale down in order to comprehend more fully the making of local canal-

based waterworks as well as basin-style irrigation.

A political ecology perspective on scale refers to the interface of human activ-

Ecumene 2000 7 (2)

Rescaling irrigation in Latin America 153

ities and the environment. Geographical political ecology focuses on socio-

natural scaling which occurs in the fusing of biogeophysical processes with

broadly social ones.3 I find that many ‘local–global’ studies tend to overlook the

conditioning of scale by geographical cultural ecology. Yet concrete expressions

of the human environment interface such as irrigation are definitely moulded

by human-shaped biogeophysical factors and flows. (Biogeophysical processes

vary from the directly human-induced to ones that are slightly or indirectly

altered by people.) This recognition leads my case study to incorporate those

environmental changes and biogeophysical factors – including hydrologic,

sediment, and vegetation processes – that have affected people’s rescaling of

irrigation in Latin America. Emphasis on the making of scale suggests that the

irrigated landscape should be thought of as the product of both environmental

and broadly social processes that include the making of cultural images.

A primary significance of this study is its focus on the environmental politics

and political struggles that surround the practice of irrigation development.

Increasingly, the modern western style of irrigation development is held to be

culturally inappropriate, socially unjust and environmentally unsound.4 In

response, local canal-based irrigation has emerged as a main alternative that is

vigorously espoused by several hundreds of institutions throughout Latin

America and in many developing countries worldwide.5 ‘Grassroots’, ‘local’ and

‘sustainable development’, now being undertaken by these government agen-

cies and nongovernmental organizations (NGOs), are planning a marriage of

local canal-based irrigation and environmental conservation, with socioeco-

nomic success. Scale is central to their claims, since local irrigation tends to be

taken as an inherited relict that brings sufficient benefits to both the environ-

ment and the people that irrigate.

My findings challenge this assumption of the inherent character and viability

of local scale irrigation. Rather, I show that local-scale irrigation is steeped in

the selective adoption and alteration (together referred to as reinvention) of his-

torical customs and traditions of resource use. In the Andean countries these

formative historical geographies date to the Inca state and the early Spanish

colonial empire. As will be seen, the local scale of canal-based irrigation has

always depended on key linkages or articulations to processes that are differ-

ently scaled. Several such processes, both broadly social and environmental, have

typically tied local irrigation to basin-scale processes. These twin images should

therefore be seen as contrasts that frequently are interlinked.

This study is guided by ideas of scale that merge the perspectives of

‘local–global’ processes and geographical political ecology. The perspective on

scales of ‘local–global’ processes (or ‘glocalization’) is concerned with the

process-based scaling of sociospatial transformations that are part of so-called

globalization.6 Those processes taking place at the large extra-regional scales

referred to as global are typically associated with other processes that are scaled

over smaller areas and that are referred to as local. Though the popular yet mis-

guided notion of a rigid dualism of ‘local–global’ scales prompts the call for

rejection of the term, my study adopts it, along with the use of quotations. Here

‘local–global’ and ‘glocalization’ indicate the reference to a geographical

Ecumene 2000 7 (2)

154 Karl S. Zimmerer

approach that is focused on sociospatial processes and multiple-level scaling.

Geographical political ecology is an approach or area of inquiry with a major

interest in scale concepts. This approach shows general similaraities to the sub-

fields of cultural and human ecology as well as hazards, geoarcheology, and land

use.7 A dialogue between geographical political ecology and the ‘local–global’

perspective on scale and scaling processes should avoid the one-way exchange

of ideas. Indeed whole-cloth importations tend to preclude the weaving or con-

necting together of ideas and concepts. Rather, I wish to advance an exchange

of ideas between a scale-sensitive ‘local–global’ perspective and geographical

political ecology.

The first exchange stems from the ‘local–global’ perspective on scaling and

territorializing. Scaling processes gain salience as people and institutions orga-

nize their capabilities through social power, conflict, and co-operation . The pre-

sent study shows how the scaling (or rescaling) of irrigation has depended on

the ‘scale capabilities’ of social actors (such as Inca subjects, the Inca state and

its provincial rulers, colonial Indians, Spanish colonists, and the Spanish colo-

nial administrators). Of equal importance is the scaling of the biogeophysical

irrigation environments. Indeed, differently scaled hydrologic, sediment, and

vegetation processes tended to aid, or be exploited by, diverse groups or indi-

vidual irrigators. Given these relations, the crucial scaling of the biogeophysical

processes of irrigation should be interwoven with the account of social forces.

A second exchange rests on the fuller awareness that the dynamism of

‘local–global’ processes was common during European colonialism and even

operated in various places during the periods of powerful pre-European states.8

‘Local–global’ interactions under the rule of colonial empires and pre-European

states periodically invoked the so-called cultural reinvention of traditions and

customs.9 Reinventions were used by the rulers and subjects of the new societies

as they sought to establish or resist new relations of social power, to give the

appearance of social cohesion or identity, and to create legitimacy for new insti-

tutions and status identities. Cultural reinvention, as a conspicuous feature of

‘local–global’ processes, may be similarly common in the realm of human–envi-

ronment relations.10 Indeed, reinventions of the image of irrigation (and espe-

cially its scale associations) were defining features of rule by the Inca state and

the early Spanish colonial empire.

Adjustments of irrigation ecologies coexisted with the rise of new cultural

images. People’s reworking of the ecologies of irrigation occurred through the

alteration of biogeophysical factors and flows. Hydrologic, sediment and vege-

tation processes became managed in different ways and acquired different scalar

properties. As discussed below, these socio-environcultural processes were inte-

grated under Inca rulers into a geographically extended and nested-type model

of territory and land use. By contrast, the Spanish colonial rulers sought to con-

solidate the management of environcultural processes in particular geographi-

cal areas, particularly the valley basins. These altered ecologies, and their allied

geographies, cooccurred alongside the metaphorical and cultural transforma-

tions of irrigation. In a broad sense, the colonial Spanish ecologies were insep-

arable from the reinvented images of irrigation, although to be sure the changes

Ecumene 2000 7 (2)

Rescaling irrigation in Latin America 155

did not always occur in simple tandem, since the space–time parameters of these

processes were complex.

Trenchant critiques of the approaches of ‘local,’ ‘grassroots’, and ‘sustainable

development’ also urge a dialogue between the ‘local–global’ perspective and

geographical political ecology. The ‘green lens’ of these projects, as Zerner calls

their environcultural emphasis, has tended to assume an overarching stability of

the processes that are viewed as the foundations of community resource man-

agement.11 Zerner and others use this insight to critique the frequent failure of

community-based conservation that purports to make use of customary law.

Their studies point out that misplaced or ill-founded assumptions of stability

also apply to alleged spatial fixity, including the crucial elements of territory

and scale.12 By adhering to preconceived ideas of ecological nature that bolster

a claim to the spatial and temporal stability of resources, many projects can

easily damage people and environments that are in or near management

areas.13

The actual making of local, canal-based irrigation, as shown in the case study

below, has been spatially dynamic and historically fluid. Periodic rescaling of

local canal-based irrigation was produced by social contestations and coopera-

tion. Change and alteration of biogeophysical factors and flows were also facets

of rescaling. Modified hydrologic, sediment and vegetation processes acted both

alone and in close concert with sociospatial changes to remake what constituted

the ‘local’ of irrigation. Here I believe a policy message must caution against

the prevalent notion, grounded in mistaken assumptions of stability, that local

irrigation tends to be relatively timeless and independent of differently scaled

processes.

Irrigation and the Cochabamba region: suyu and basin definitions

The making of past irrigation landscapes in Cochabamba cannot be separated

from current dilemmas. At present the greater Cochabamba region of central

Bolivia, as shown in the inset of Figure 1, is home to about 2 million people.

The majority of inhabitants are rural and semi-urban farmers and livestock-

raisers who work part-time, usually seasonally, in jobs in agro-industry and in

the vast informal sector of the Cochabamba urban area (1990 population

c. 900 000).14 Many people of Cochabamba speak Quechua as well as Spanish

while some also rely on the Aymara language. Cultural and livelihood practices

of the region’s cochabambinos are hybrid concoctions of diverse expressions.

Large numbers of people reside partly in Indian or peasant communities, while

they may also work for extended intervals in modern cities such as Cochabamba

or Santa Cruz, or foreign ones, including Buenos Aires and several in the United

States. Poverty and the lack of basic requirements are commonplace in

Cochabamba; living and working conditions are extremely difficult for the huge

majority of the population.

Irrigation-based agricultural development has been seized upon since the mid-

twentieth century as a main solution to poverty in Cochabamba. Since then a

large number of development agencies of international, national, and regional

Ecumene 2000 7 (2)

156 Karl S. Zimmerer

governments have supported irrigation projects in the region. Neoliberal gov-

ernment cutbacks, decentralization policies, and worsening poverty since 1985

have spurred more than 200 nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) to under-

take projects in Cochabamba. Their recent projects tend to put a priority on

the attempt to fuse development with environcultural conservation.15 Local-scale

irrigation and environment-development objectives are nowadays a main com-

ponent of many ‘grassroots’, ‘local’ and ‘sustainable development’ projects.

Their interests in local canal-based irrigation are typically seen as supporting the

postcolonial alternatives of community autonomy and govern cultural decen-

tralization while opposing private interests and centralized state power. Projects

with these interests have become locally common in Cochabamba and elsewhere

in the Andean countries in the 1980s and the 1990s.16

Present-day irrigation projects of all types in Cochabamba, with the dilemmas

they face, are built upon existing irrigation practices. The social and environ-

mental history of irrigation in the region is extensive and influential, since mod-

erate to large numbers of farmers there have relied on irrigated agriculture for

at least 1200 years.17 Near Tarata, a provincial capital and the site of a major

pre-European irrigation works (Figure 1 inset), the practice of irrigating field

crops likely began as early as 1500 BC and thus may have been one of the earli-

est places of irrigated farming in the Americas. Under the Inca and Spaniards

the irrigated agriculture of Cochabamba was expanded and reorganized, solid-

ifying its identity as the chief bread-basket of the south-central Andes. The

materials used in my study of Cochabamba irrigation in the periods of Inca and

early Spanish colonial rule consisted of published accounts and unpublished

administrative and judicial documents (imperial, viceregal, and regional) that

date to the 1500s. The following case study considered these primary and

secondary historical sources in conjunction with environcultural analysis.

The widespread use of two terms led to their adoption in this case study. Local

canal-based irrigation in Cochabamba was referred to historically by the term

suyu (which still today is widely used). The designation suyu was used by

Quechua-speaking Inca administrators and colonists of Cochabamba and later

by colonial Indians and Spaniards. Suyu applied both to an image of irrigation

and to its actual area of operation. Ecologically and socially, the suyu in

Cochabamba was the organization of irrigation according to the cluster of fields

fed by a primary canal and managed according to this canal-based unit (Figures

2 and 3). In addition to irrigation, the term suyu also referred to the sociospa-

tial division of rights and responsibilities that attached to the management of

other resources, such as the co-ordinated rotation of fields and rangeland

through sectoral fallow.18

‘Basin’ refers to the valley floor or bottom-land that was a scale commonly

referred to in the images of Cochabamba irrigation. The English word ‘basin’

closely resembles the meanings of a variety of terms such as pampa and valle that

were used in speech and writing in Quechua and Spanish during the periods

of Inca and Spanish colonial rule. Pampa and valle, when the latter was applied

to Cochabamba irrigation and land use, were terms that typically designated the

entire floor or bottomland of the valley. The Valle Alto (High Valley) and Valle

Ecumene 2000 7 (2)

Rescaling irrigation in Latin America 157

El Paso

1

2

3 Sacaba

Quillacollo

4

Rí

Ri C

Río a ine

Caine Roi

AAn

5 ngg

ooss

tutu

rara

Sipesipe

NORTH

Approximately 5 Kilometers

Figure 2 ~ The Cochabamba valley (also known as the Central Valley or Valle Central)

and suyu groups made by the Inca Huayna Capac. This map is based on early colonial

documents (Source: Modified from N. Nachtel, ‘The mitmas of Cochambamba Valley:

the colonization policy of Huayna Capac’, in G.A. Collier et al., eds, The Inca and Aztec

states, 1400–1800: anthropology and history (New York; Academic Press, 1982), p. 207)

Central (Central Valley) formed the principal basins for Cochabamba irrigation

(Figure 1 inset). Basin irrigation typically depended on the control of one or a

few water sources. In Cochabamba, this scale of irrigation often came to consist

of a sub-basin of the valley floor, even if irrigation was planned or imagined for

the full basin area.

Suyu irrigation and the web of Inca geography

From their capital city of Cuzco, the armies of the Inca state conquered the

inhabited mountains and coastal lowlands as far north as Pasto in present-day

southern Colombia and to the south in central Chile. The Inca conquests of

this realm were concentrated between about 1440 and 1500. Geopolitical state-

craft of the Inca empire relied on the integration of scores of diverse ethnic

groups and territories. Centred on Cuzco, the Inca state organized its vast

territory into four spatial sub-units known as suyus (sometimes spelled suyos):

(i) Collasuyu to the south and southeast, which included the Cochabamba

valleys that were conquered in the late 1400s by the Inca emperor, Huayna Cápac

(r. 1493–1527); (ii) Cuntisuyu to the southwest; (iii) Chinchaysuyu to the north

Ecumene 2000 7 (2)

158 Karl S. Zimmerer

Jacha

Moco

4

Villa 3

Mercedes

Road to

Cochabamba

2 Santa Cruz

Highway

R

i

Calic

a

n to

Pra

do

Canal

M

Can

am

Canal

an

1

Cardoso

al

ac

a

NORTH

Gringo

Ca

na

Road to

l

Cochabamba

0 300 600

Meters

Main Irrigation Canals

Main Diversion Barriers Tarata

Irrigation Canal Influence Zones

Road to Cliza

Figure 3 ~ Suyu irrigation areas at the Calicanto irrigation complex near Tarata. Map

based on field notes, historical documents, and aerial photographs.

and northwest; and (iv) Antisuyu to the east. In each of the four territories, or

suyus, the provincial administrators of the Inca empire directed extensive irri-

gation and agricultural terrace works.19 Their massive projects affirm the

modern-day designation of the vast Inca empire as one of the world’s pre-

eminent ‘prehistoric hydraulic states’.20

Inca state policy led to the transformation of the valleys of Cochabamba into

the premier bread-basket of the south-central Andes. The ruler Huayna Cápac

ordered the labour drafts and resettlement colonization that marshalled an esti-

mated 14 000 agricultural workers for the state’s production of irrigated maize.21

Irrigation was crucial for the success of the empire’s maize growing in the

Cochabamba valleys. Annual rainfalls that were probably similar to recent means

of 450–550 mm. (approximately 18–22 in.) could not secure rainfed farming in

the tropical, semi-arid climate of Andean valleys such as Cochabamba.22

Ecumene 2000 7 (2)

Rescaling irrigation in Latin America 159

Moreover, past climates of Cochabamba and the greater central Andes that pre-

vailed during the 1400 and 1500s were probably colder than present, which may

have stimulated agricultural intensification such as field terracing in the

favourable growing areas of low–middle elevations.23 Climate and intensification

pressures may thus have contributed to the incentive for irrigation in prime

farmlands such as the Cochabamba valleys.

The canal-centred area of the suyu served as the chief spatial unit of irrigated

farming in the Cochabamba valleys during the Inca reign.24 In the main Central

Valley of Cochabamba, the largest of the flat-floor grabens produced by fauling

and uplift in the region, the suyus that took shape were long ‘bands’ or ‘stripes’

(Figure 2).25 Major canals brought irrigation to each of the suyu units. An esti-

mated 77 suyus made up the irrigated farming of the Central Valley. In turn this

large number of suyus was grouped into a total of five expansive growing areas

(referred to in colonial documents as chacaras), shown in Figure 2. The Inca

rulers alloted these Cochabamba chacaras and the suyus within them to the chief-

tains, or kurakas, of diverse ethnic groups, to state-operated farmlands, and to

the workers, known as mitimas, who were drafted for state agriculture. In other

Andean valleys, such as Cuzco, the Inca state placed a similar emphasis on coor-

dination of canal-centred irrigation clusters, which state administrators and local

people referred to by such names as ceques.26

Suyus were also the primary spatial unit of Inca farming at the Calicanto irri-

gated area near the village of Tarata in the western corner of the High Valley

(Valle Alto) of Cochabamba, a large graben and presumably once a Pleistocene

lake bed (Figure 1 inset). Canal remains and sedimentary deposits suggest that

the Calicanto suyus were shaped like radial cones (Figure 3).27 Some suyus at

Calicanto were probably constructed, or administered anyway, directly by the

Inca rulers.28 This irrigated maize agriculture would have resembled the state-

led production of the Central Valley, although on a reduced scale. In addition,

the Inca rulers had granted a certain share of the Tarata suyus to the farmers

of diverse ethnic groups. The ethnic groups at Calicanto were referred to as

señorios or ‘nations’ in colonial documents of the sixteenth century. These irri-

gators consisted of various peoples from Mizque in southern Cochabamba and

other Inca subjects belonging to the ethnic groups of the chichas. (The primary

residence of the chichas was located still further to the south.) With the grants

of Calicanto suyus to these ethnic groups, the Inca state sought to ensure their

self-provisioning of staple foodstuffs such as off-season potatoes (mishka papa).

The importance to irrigation of the suyu image as a cultural concept was sug-

gested by the notable extent and significance of the word’s connotations. The

primary gloss of suyu was ‘sector’. The Inca applied this meaning to the chief

territories of the state (e.g., Collasuyu, Cuntisuyu, Chinchasuyu, Antisuyu) as

well as to irrigation units. These primary connotations were supplemented by

other widespread usages. Indeed, the suyu root was contained in more than two

dozen common terms recorded in the early colonial Quechua-Spanish dictio-

naries, especially those of the Jesuit priests Fray Diego González de Holguín and

Fray Domingo de Santo Tomas, who both lived for prolonged periods in south-

central Andean cities such as Cuzco and Puno (Figure 1).29 Their dictionaries

Ecumene 2000 7 (2)

160 Karl S. Zimmerer

attested to the cultural power and wide range of suyu as an Inca concept and

cultural image.

Suyu irrigation was not merely the vivid spatial realization of a powerful cul-

tural image; it was also a product of the social processes that shaped human-

induced environcultural changes. At the Calicanto suyus, the work of irrigators

channelled irrigation water and water-borne sediments over a farming area of

roughly 30 km2. Their work with water and sediment guided the deposition of

huge quantities of sand and silt that were transported via stream channels from

the heavily eroding farmlands of the upper Calicanto watershed.30

(Accumulation of irrigation sediments in the Calicanto irrigated area were

0.5–4.5 m. deep by 1991.) Sedimentology of the irrigation-derived deposits at

Calicanto – especially the vertical continuity and the lateral or areal contiguity

– indicated that its waterworks were probably deployed during Inca rule as well

as before. The colonizing Inca rulers probably devised suyu irrigation by adopt-

ing and expanding the use of existing waterworks.

Suyu irrigation hinged on the modification of various environcultural

processes. Water and sediment flows and deposition, soil characteristics includ-

ing moisture availability, and vegetative cover were common human-shaped mod-

ifications of suyu irrigation.31 The task of irrigators at suyu sites such as Calicanto

was to channel intermittent, high-energy, floodwater-type flows from mountain

streams across low gradient slopes and alluvial fans such as the one that formed

below Tarata. Biogeophysical changes were characteristic of irrigated fields, con-

veyance canals, and drainage and discharge habitats. Presumably undertaken by

Inca corvées and other groups of skilled farm labourers, these environcultural

alterations helped to ensure the usefulness of suyu irrigation. Irrigation struc-

tures associated with these environcultural alterations also provided an incen-

tive for continued use of the suyu arrangements.

The Andean valley basins, such as the Central Valley and the High Valley of

Cochabamba, served as the immediate setting for collections of multiple irri-

gated suyus cultivated with maize. This function of the basin demonstrated its

crucial many sided role in Inca land use and politics. The Inca rulers and their

subjects viewed the subtropical mountain basins and valley bottom-lands (well

suited for maize growing) as one of a handful of similarly scaled environments

(along with temperate alpine farmlands, grass-covered pasture and rangelands,

coastal lowlands, and humid forested foothills). Taken collectively, these envi-

ronments were part of a notable state policy and a conspicuous cultural ideal

through which the state and its subjects, including the conquered ethnic groups,

exercised direct access to the varied environments, including mountain basins,

and the resources they contained.32

The image of the valley basin also was used to showcase Inca state power and

its agro-environcultural prowess. Here too, the use of the valley basin was woven

together with other similarly scaled environments into a web of Inca geography.

The Inca state and its subjects, especially the region-scale ethnic groups or seno-

rios, valued the mountain basins as a crucial node within the web of utilized

environments. This web of Inca geography was later termed ‘verticality’ or

‘vertical archipelago’ (in the case of discontinuous territories) by modern-day

Ecumene 2000 7 (2)

Rescaling irrigation in Latin America 161

ethnohistorians.33 A revealing account of the role of the Cochabamba basins in

the web of Inca geography was authored by the remarkable auto-ethnohistorian

known as ‘The Inca’, Garcilaso de la Vega (1539-1616) (born Gómez Suárez

Figueroa to an Inca colonial noblewoman and a Spanish conquistador of Cuzco).

His influential and popular Comentarios reales de los Incas, first published in Spain

in 1609, gave the following account of valley basins under the Inca state: ‘From

all these cold provinces [Collao and the Altiplano] they [the Inca] removed

many Indians at their own expense and settled them to the east . . . regions of

grand fertile valleys . . . which had been uninhabited . . . totally abandoned, empty as

a desert, because the Indians had had neither the knowledge nor the skill to build canals

to irrigate the fields’ (my translation and emphases).34

Garcilaso’s passage on the mountain basins of Cochabamba blended the geo-

graphical ideals of both the Inca state and Spanish colonial rulers.35 First,

Garcilaso’s empireexalting narrative, written in Seville, where he lived his adult

life, credited the irrigated landscapes of the Cochabamba basins entirely to Inca

power and knowledge. The civilizing Inca were said to have filled the previous

emptiness of these places. To the colonial geography of Spaniards in western

South America the Garcilaso-style rooting of geographical ideals and use pat-

terns in ‘grand fertile valleys’ became a familar ideal: the resplendent qualities

of the Andean valley basins beckoned colonists. Overall, Garcilaso’s account of

the Andean basins thus seemed to fuse a mixture of Inca and Spanish geogra-

phies. This fusion of landscape images and geographies presumably reflected

his own experiences and identity since other expressions of the ‘hybrid’ char-

acter of Garcilaso distinguished one of the most distinctly creole perspectives

on early colonial Latin America.36

Basin irrigation and the geography of Spanish colonialism

Valley basins became a central focus of Spanish colonialism in western South

America beginning with military conquest of the Iberian invaders. In the wake

of the military defeat of the Cochabamba region in 1539, the valley settlement

of Tarata in the High Valley was serving already by 1550 as a colonial district

(corregimiento) and food supplier within the sprawling viceroyalty of Peru and its

mountainous subdivision of Alto Peru (literally High Peru, whose approximate

boundaries were Huancavelica and Jujuy: Figure 1). In the Central Valley not

far from Tarata, the colonial Spaniards founded the Villa de Oropesa, later

renamed Cochabamba.37 In the Cochabamba valleys the rights to the control

and use of land and irrigation were at the core of myriad conflicts among colo-

nial Spaniards and Indians. As discussed below, the local suyu irrigation persisted

in the region albeit with major modifications. At the same time, the valley basins

and their uses such as irrigation were imbued with an unprecedented value in

the new Spanish colonial geography.

Valley basins like the High Valley and the Central Valley of Cochabamba

fired the geographical imaginations of the Spanish rulers of the Andean colony

in a remarkably far-reaching fashion. A majority of early colonial town settle-

ments in the Andes were located in valley basins (with notable exceptions such

Ecumene 2000 7 (2)

162 Karl S. Zimmerer

as mining centres at Potosí and Oruro and Altiplano locations like La Paz). The

High Valley had its principal settlements at Tarata and Cliza, while the early

colonial towns of Quillacollo and Oropesa/Cochabamba were major settlements

of the Central Valley (Figures 1 and 2). Other major valley towns in High Peru

were founded by the colonial viceroyalty at La Plata or Chuquisaca (now Sucre)

(1538–9) and Tarija (1550). By 1590 the new Peruvian viceroyalty had officially

founded more than 100 valley towns in the Andes mountains between Antioquia

in present-day Colombia and Tucuman in the Andean foothills of northwestern

Argentina. In the colonial geography of the Spanish rulers, these Andean val-

ley towns functioned as centres of military strength and political control.

Many towns in the valley basins took shape through the nucleations of Indians

forced to relocate from the remote uplands and surrounding mountain slopes.

The preferred location in valley basins of these forced resettlements, known in

South America as reducciones, simultaneously made and mirrored the power geog-

raphy of Spanish Andean colonialism.38. . . Reducciones were designed and

enacted by Francisco de Toledo (r. 1569–81), who as viceroy was the head admin-

istrator and chief architect of crown policy in western South America under the

Spanish emperor Phillip II. For Toledo, securing the valley settlements of the

mountainous Peruvian colony was a geopolitical imperative.

In Cochabamba more than 100 pre-Spanish settlements were nucleated by

colonial administrators into an estimated dozen reducción towns, all located in

valley basins. Valley settlements of Cochabamba that were founded by colonial

edict included Capinota, Tiraque, Mizque, Aiquile, Tiquipaya, El Paso, and Sipe

Sipe (Figure 2).39 With these forced resettlements and the consolidation of the

remaining rural population into Indian communities, Spain’s colonial govern-

ment destroyed the once powerful role of the region-scale ethnic groups or seño-

rios. Indeed, the early colonial administrators purposefully dismantled the

region-scale patterns of land use that powerful ethnic groups had co-ordinated

under the Inca policy of verticality or vertical archipelago. Under the geogra-

phy of early Spanish colonialism the Andean valley basins became, in a broad

sense, the geographical successor to the once powerful region–scale webs of the

ethnic groups.

Farmlands around the new valley settlements of the Peruvian viceroyalty fed

the colonial population centres. Irrigated where possible, the valley farmlands

gained a multi-faceted importance. The economic and agro-ecological value of

the valley farmlands was featured in the Spanish crown’s imperial geographical

reports, or relaciones geográficas. The regional reports commissioned by the

Empire contained the responses of magistrates and other local officials to a stan-

dardized imperial survey. Sanctioned by Phillip II (r. 1556–98), the 49-question

survey had been drafted and distributed by imperial cosmographers and states-

men through the Council of the Indies during the 1570s and 1580s.40 Preserved

copies of relaciones geográficas were completed for Cochabamba in 1585 and

1586.41 According to these reports, the region was a pre-eminent supplier of

foodstuffs to Spanish colonial settlements throughout the south-central Andes.

Wheat, and wheat flour in particular, signified a special place for the valley

basins of Cochabamba. Wheat itself was a dietary staple among colonial

Ecumene 2000 7 (2)

Rescaling irrigation in Latin America 163

Spaniards, and wheat bread was a sine qua non of their accustomed cuisine, their

staff of life.42 In short wheat fortified colonial rule. To colonial Spaniards and

to crown administrators, the Cochabamba granary evoked the geographical

image of irrigated valley basins.43 Widely read and influential accounts of High

Peru (Alto Peru), the Peruvian viceroyalty, and Spanish colonial geography

touted this image of the Cochabamba basins. In the early 1600s, for example,

Reginaldo Lizárraga and Antonio Vázquez de Espinosa remarked on the fame

of the irrigated ‘valleys of Cochabamba’ as premier wheat producers.

The renown of the irrigated valley basins of Cochabamba as primary wheat

producers stemmed also from the magnitude of inter-regional trade under

Spanish colonialism. Hacienda estates located in the Cochabamba valleys, owned

by Spaniards and located in the vicinity of town settlements, supplied wheat that

was shipped via transport and trade circuits to colonial mining centres and other

population nucleii in places unsuited to wheat growing. Most notable among

these wheat importers was the mining metropolis of Potosí, a city of more than

100 000 inhabitants by 1600. The irrigation basins of Cochabamba also shipped

much wheat to the Altiplano and especially the settlement of Ciudad Nueva,

later renamed La Paz and made into the legislative capital of Bolivia. By treat-

ing the irrigated basins as producing units, the rhetoric of official colonial

reports tended to overlook wheat production and trading by Indians. Their over-

sight belied the extensiveness of Indian production and commerce, including

wheat cultivation and trade, that was an integral part of the colonial economy

in High Peru and throughout much of the Peruvian viceroyalty.44

Irrigation was inevitably given mention in major colonial descriptions of the

geography of the Cochabamba valley basins. Reginaldo Lizárraga, a high-rank-

ing colonial official, predicted that irrigation of the Cochabamba valleys (taken

to be the basin-wide scale) would fuel a severalfold expansion of wheat pro-

duction.45 That amplification, Lizárraga claimed, would be sufficient to provi-

sion wheat flour and unmilled wheat to both the burgeoning populations of

Potosí and the densely settled Altiplano – particularly its new colonial trade

nexus at the city of La Paz. According to Lizárraga’s account, the wheat from

the Cochabamba valleys was the ‘best in the world’. Similarly, the wheat of irri-

gated Cochabamba valleys garnered high praise in other imperial compendiums

on New World colonial geography. For example, high praise for irrigated wheat

growing was featured in a well-known account of Cochabamba entitled ‘The

famous valley . . . and its district’ written by the perspicacious Antonio Vásquez

de Espinosa.46

Colonial geographical descriptions of Andean valley irrigation were also

deeply cultural works. These mid-elevation tropical mountain valleys were dis-

tinguished by a mild climate, a seasonality of precipitation, and growing condi-

tions suited to wheat and a variety of Mediterranean food plants that were staples

of Spanish colonial cuisine.47 Colonial accounts emphasized favourable com-

parisons between these particular food-growing landscapes of the Peruvian

viceroyalty and familiar southern European environs. The valley basin of

Cajamarca, located in the northern sierra of present-day Peru, could be covered

with wheat that ‘grows as well as in Sicily’, according to the pioneering Andean

Ecumene 2000 7 (2)

164 Karl S. Zimmerer

chronicle of Pedro de Cieza de León, a soldier–scribe and later chronicler whose

1553 book was widely read at the time in Spain, Europe, and the New World

colonies.48

The image of the irrigated basins of the Andes wove together the imperative

of strategically familiar landscapes and allusions to divine providence. Abundant

instances of the latter, in which irrigated valley basins were seen as signs of

earthly paradise, peppered both the pioneering and most scholarly treatises on

Andean landscapes and geography.49 The irrigated basins were divinely favoured

or beneficent, not to mention well suited and inviting to Spanish colonial use.

In addition to irrigation, the soil fertility and climate were often registered as

most favourable. Indeed, the leading chronicles of colonial landscape and geog-

raphy gave the impression of a valley-specific concentration of marvels that

invited and justified Spanish colonialism in the Andes in a way akin to the rhetor-

ical support of Spanish imperialism throughout their New World colonies.50

Divine wonders of the Andean basins were also naturalized.51 For instance, early

Spanish colonial geographical accounts compared the irrigation of mountain

basins to the natural rainfall runoff from upland slopes, a process also referred

to as regar.

Suyu irrigation of Cochabamba did not disappear in the 1530s; rather the

existing waterworks became reformulated with the onset of Spanish colonialism.

To my knowledge, the suyu irrigation of Cochabamba was unmentioned by the

high-ranking cosmographers, chroniclers, and chief colonial administrators of

the region. A contrast to the conspicuous imperial codification of Cochabamba

irrigation as valley- or basin-scale in scope, the suyu irrigation was reformed with-

out official pronouncement. Suyu irrigation was remade in a manner that fitted

within new colonial institutions in the irrigated valleys. Colonial land use and

property institutions in Cochabamba such the encomienda, the lease to a land

tract replete with tribute-paying Indian residents, and the hacienda, the well-

known manorial estate, were faced with conditions, including ecological ones,

that encouraged the adoption of the suyu.

A growing number of Spaniards laid claim to hacienda estates of valley farm-

land, together with the riparian rights to irrigation, in the Cochabamba valleys.52

Their claims were established through crowngrants, acquisitions, and frequently

the outright theft of Indian resources.53 In some cases the colonial Spaniards

and their workers destroyed the off-takes of Indian canal arrangements in order

to divert irrigation into their own waterworks. In many cases, however, they pre-

ferred the tactic of usurping the intact Indian waterworks. In the High Valley

near Tarata, the canal-based territories of suyus outlined the new boundaries of

Spanish colonial haciendas. These colonial estates included those such as Prado

de San Luís and Mamanaca, formed in the Calicanto irrigated area.54 The largest

hacienda estates, such as Chullpas, which was located midway between Tarata

and Cliza, contained as many as ten suyus within its boundaries.

Use of suyu-based irrigation by colonial haciendas in the Cochabamba

valleys grew from a mix of the selective borrowing and alteration of existing

practices. Colonial haciendas at Tarata and other High Valley sites, which

were estimated to number 24 by 1692, presumably found it advantageous to

Ecumene 2000 7 (2)

Rescaling irrigation in Latin America 165

adopt the technical infrastructure of suyu irrigation.55 Suyu off-takes and diver-

sion weirs from the river channels, extensive networks of primary and secondary

canals, drainage devices connecting between fields, and the ubiquitous embank-

ments along field borders (known as ‘bunds’ in irrigation parlance) were key

infrastructural elements. These technical features of irrigation, which had been

created by the human shaping of biogeophysical processes via the labours of

Indian farmers, could be converted to hacienda use. Rights to suyu irrigation

were made to correspond to the legal customs of Spanish water law. In the

Peruvian viceroyalty, that legal tradition was modified to make use of the rota-

tional style of irrigation scheduling that had been a basis of the Inca-sponsored

mit’a.56

The centrality of irrigation suyus and other canal-based spatial units was rein-

forced by the resistance of colonial Indians to Spanish domination. Attempted

protection of water rights became a main form of Indian resistance. Resistance

efforts pivoted on the control of irrigation territory, and sometimes entailed

legal tactics that appeared in judicial documents. Several legal cases were filed

with respect to irrigation disputes in Cochabamba’s valleys, especially its Central

Valley. Following military conquest, the Peruvian viceroyalty had granted the lat-

ter’s farmlands, water resources, and Indian residents as two prize encomienda

leases to high-ranking Spaniards. By 1540, one valley lease, held by the renowned

viceregal lawyer Juan Polo de Ondegardo, was being hotly contested.57 (Juan

Polo de Ondegardo was a leading expert of the Spanish empire on Inca history,

land tenure, and land use.)

In 1556 the leader of a group of colonial Indians known as the Paria filed

suit in Spanish colonial court against Polo de Ondegardo and the Indians liv-

ing on his Cochabamba encomienda.58 The Paria were an ethnic group, which

had earlier been recognized by the Inca and whose principal territory was

located near Oruro (Figure 1). Hernando Asacalla, the leader of the Paria

Indians in 1556, deposed exhaustive information about his group’s rights to land

and water in the Central Valley. Asacalla’s deposition showed in convincing detail

how the Paria people, along with eight other ethnic groups, had been granted

irrigation suyus by the Inca ruler Huayna Cápac. While their primary residence

was located in Paria, located in the Altiplano about 100 km from Cochabamba,

they reported that during the Inca reign their group regularly sent members to

work the irrigated farmlands of Cochabamba on either a seasonal or a year-

round basis.

Legal efforts by Asacalla and the Paria people to regain their lost lands did

not succeed, yet their desperate attempts illustrated how the everyday impor-

tance of suyus and allied land units were reinforced by resource conflicts.

Asacalla and the Paria people staked their water and land claims to suyu units

even decades after conquest. These subjects of the Peruvian viceroyalty, like

other colonial Indians, wished to demonstrate that their previous rights had

been fully established under the Inca, and had then been removed illegally.

Legal claims of encomenderos, hacendados, and other landowners (mostly

Spaniards), for their part, also relied on claims to Inca territories such as the

suyu. The tactics of these colonial landowners aimed to prove that their prop-

Ecumene 2000 7 (2)

166 Karl S. Zimmerer

erties were descended directly from holdings of the vanquished Inca state rather

than gained through the usurpation of other Indian holdings.

Reinforcement of suyu territories by judicial disputes could thus stem from

the actions begun either by colonial Indians or by Spaniards. Of course, the two

parties tended to marshal the past traditions of suyu use for their own contrasting

purposes. Deft manipulation of the contradiction was deployed by the well-

informed Polo de Ondegardo in the dispute over his Cochabamba encomienda.

Responding in 1540 to a local judge’s issuance of a set of 14 questions, a so-

called interagatorio, Polo de Ondegardo elabourated how his encomienda had con-

sisted of lands that had belonged to certain Inca chacaras, which were large land

areas each made up of groups of suyus.59 Polo de Ondegardo testified in the

same legal deposition that these irrigated chacaras (and the suyus they contained)

had never been possessed by the Paria Indians or others. Justifying his own land

claim, the legalist swore that these irrigated valley lands had never been used

by a nonlocal ethnic group.

By relying on claims to Inca ownership, the practice of colonial law in west-

ern South America was reinforcing the spatial domain of certain resource insti-

tutions, in particular the suyu. This consequence was surely paradoxical, at least

at first glance, for legal codes in the Spanish colonies were conceived of as major

instruments for the integration of subject territories into the overseas empire.

Spanish rulers counted on such codes in order to establish property rights and

rules for the use of resources. Still, the colonial rulers of Andean South America

were also compelled to incorporate references to Inca property precedents. Such

considerations were both legal theoretic and socio–political.60

The importance of suyus and other canal-based territories continued amid the

cascade of colonial conflicts over irrigation resources. It was noted even by

Viceroy Francisco de Toledo, chief architect of the colonial design of valley-based

geography. During his royal inspection (visita) of Cochabamba in 1574, Toledo

reported how Indians and Spaniards were embroiled in local disputes over irri-

gation at the scale of individual canals.61 Visiting the Mizque valley of southern

Cochabamba, Toledo witnessed a heated dispute over irrigated land. Mizque

Indians had lodged a complaint against a colonist named Diego de Valera.

According to the account contained in Toledo’s visita, the Indians complained

that the colonist had stolen their water rights by diverting a main canal, and

that he was trying to steal their lands by devaluing them. At each attempt of the

Mizque Indians to rebuild the canal system, Diego de Valera was said to order

his oxen teams be be used to destroy the connections of canals to their fields,

thereby altering water flow and sediment transport that was crucial to irrigated

farming.

A similar struggle took place on the outskirts of El Paso (then Santiago del

Paso), a reducción resettlement of Indians in the Low Valley located about 10 km

from the Villa de Oropesa (later to become Cochabamba).62 Indian towns-

people and their crown-appointed legal representative (known as the protector de

los naturales) initiated the suit by addressing a letter of complaint directly to

Phillip II, the Spanish emperor. The defendant in their complaint was Gerónimo

de Ondegardo, heir of the famous legalist. The El Paso people and their

Ecumene 2000 7 (2)

Rescaling irrigation in Latin America 167

representative denounced Gerónimo de Ondegardo for having stolen so much

water that the Indians were left ‘drinking it from puddles’ (beberla de charcos).

The lawyer of Gerónimo de Ondegardo, acting in his absence since the defen-

dant resided in La Plata (later Buenos Aires), tried to marshal a defence on

grounds that the disputed irrigation source and the watered farmland were

derived from an Inca suyu rather than from Indian lands.

If such legal disputes preserved the salience of suyus within the colonial sys-

tem, just as important to their survival was their practical usefulness. Suyu irri-

gation utilized by Gerónimo de Ondegardo, for example, was claimed by the

defendant to produce an annual wheat crop of 300 fanegas on his estate (about

3000 kg.).63 His defence also claimed that the disputed water source provided

turning power for three grist mills that ground wheat flour. Wheat and wheat

flour, emblematic foodstuffs of the Spanish overseas empire, thus flowed from

the reinvented use of local irrigation arrangements. The actual commonness of

local, canal-based arrangements continued to contrast the image of basin-scale

or valley-wide irrigation that had been created as a foundation of Spanish colo-

nial geography in the Andes.

Coda: the subsequent rescaling of irrigation to the grassroots

The basin scale acquired further salience as the chief geographical image of

Cochabamba irrigation under the later period of Spanish colonial rule. This

geospatial vision culminated in the plans of late colonial Bourbon rulers. Basin-

scale irrigation at Cochabamba was advocated in the survey of Francisco de

Viedma, a high-ranking Bourbon administrator who directed reforms in the

sprawling Intendencia of Santa Cruz.64 Following Bolivian independence from

the Spanish empire in 1826, a variety of schemes for basin-scale irrigation were

proposed and constructed, to varying degrees, in the Cochabamba valleys.65

Economic liberalism, foreign investment and an ethos of modernization moti-

vated these basin-scale irrigation schemes. Influence of the national and mod-

ern image of irrigation owed much to the conflictive encounters and

geographies of Spanish colonialism, even though the more recent schemes were

also created as postcolonial constructions.

Basin-scale irrigation increasingly became a reality in the mid-twentieth cen-

tury. Typically the modern schemes for basin-scale irrigation, which became

common in Cochabamba after the populist 1952 National Revolution, sought to

centralize water authority and enforce a fee agreement. Ideally, the development

of modern irrigation in the region would have occurred in conjunction with

populist agrarian reform. Basin-scale irrigation and allied modern institutions

were exemplified by the National Irrigation System Project No. 1, otherwise

known as La Angostura. Inaugurated in 1950, the La Angostura project created

a large reservoir in the High Valley (known as Laguna de Angostura; Figure 1

inset) in order to irrigate a large part of Cochabamba’s Central Valley. The La

Angostura project was the largest irrigation scheme in Bolivia until the mid-

1990s.66 It epitomized the centralization of basin-scale irrigation projects and

institutions in the prized valley bottoms.

Ecumene 2000 7 (2)

168 Karl S. Zimmerer

Most recently, a number of development agencies, including many NGOs, are

offering support to local canal-based suyu irrigation in Cochabamba.67 The

region’s largest example of local canal-based suyu irrigation is the Multiple-Use

Laka Laka Project (Proyecto Multiple de Laka Laka). Led by a ‘grassroots’ NGO

and funded by international aid agencies in support of ‘sustainable develop-

ment’, the claim of the Laka Laka project is that its incorporation of suyus is

ensuring the preservation of tradition. The project also believes that the local

scale of its suyu irrigation traditions will ensure the socioeconomic advantage of

even distribution of benefits among water users and the environcultural bene-

fit of sound resource management. To date, both their claims and their promises

have been hotly contested. The claim to preserve tradition is challenged espe-

cially by a group of former occasional irrigators, known as tail-end users, whose

fields are located at the outer ends of the earlier suyu canals. These tail-end

users were excluded by the spatial planning and boundary fixing of the Laka

Laka Project. Indeed, the struggles for water rights by tail-end irrigators illus-

trates the blatant reinvention, based upon spatial fixing of the local scale, that

is a cornerstone of the local development being undertaken at the Laka Laka

Project.

Similarly, local struggles have arisen over the extra-local distribution of the

benefits and costs of the Laka Laka Project. These social struggles revolve around

both socioeconomic and environcultural features of the project. One conspicu-

ous struggle is being waged by the inhabitants of the neighbouring Calicanto

uplands in the hill country west of Tarata. These upland land users are being

pressed to undertake soil conservation works, perhaps even drastic measures, in

response to the severe erosion that is resulting in sedimentation that threatens

the irrigation works.68 The people whose principal lands are located in the

upland watershed, who already were much poorer than the irrigators, are

angered over the local scaling of the benefits and costs of the Laka Laka Project.

The upland land users are embittered that they were excluded as participants

or beneficiaries of the project and are, at the same time, being asked or even

required to make sacrifices and concessions in order to implement the conser-

vation measures.

Conclusion: images of scale and scales of irrigation

Rulers of the Inca state and the Spanish colonial empire conceived of canal-

based suyus and Andean valley basins, respectively, as chief scalar images of

irrigated farming. The rulers utilized these scales of irrigated farming to situate

the choice irrigated landscapes of such sites as Cochabamba within their own

distinct geographical orders. Irrigation of suyus and valley basins highlighted

the political power of the Inca and Spanish rulers, added to their economic

domination, and made more governable the nonInca ethnic groups and later

colonial Indians. To empire-building Spaniards in the 1500s and 1600s, the

Andean basins served to anchor a new colonial geography of the Andes.

Irrigated agriculture, like forced resettlement, was emblematic of the new

empire’s conspicuous control of the Andean valley basins that were geopolitical

Ecumene 2000 7 (2)

Rescaling irrigation in Latin America 169

strongholds in High Peru and other subdivisions of the sprawling Peruvian

viceroyalty.

Notwithstanding the dichotomous images of the local canal-based suyu and

the larger basin unit, the scaling of irrigation took place in processes that were

interlinked. Social co-ordination, conflict, and human environcultural changes

conditioned a more complex and multiple-level scaling of irrigation than could

be seen in the dual pair of images. Inca suyu irrigation was tied to the larger

‘vertical’ web of state geography that featured valley basins as a principal node.

That Inca geography sought to consolidate rule over diverse ethnic groups and

to co-ordinate their local land use. Intermediate-scale co-ordination of irrigation

and other local resource management was central to the Inca state. Colonial

Spanish administrators dismantled those scales of land use that were co-ordi-

nated over region-size areas larger than strictly local communities. As part of

that dismantling of existing social and environcultural processes, the new

European rulers reinvented suyu irrigation as a key feature of local water man-

agement that fitted into their basin-centred domination of the Andean peoples.

Related rescaling and reinvention of local resource use under Spanish colo-

nialism featured mit’a riparian water rights, ayllu rural communities, and manay

sectoral fallow.

Current development efforts in the Andean countries and throughout Latin

America are heavily influenced by the contrasting images of local canal-based

irrigation and basin-wide schemes. The influence of this present-day perception

is deeply rooted in the irrigation geographies of the pre-European and early

colonial periods, although this influence has been overlooked. Rapidly growing

interests in ‘local’, ‘grassroots’, and ‘sustainable development’ can benefit by

paying close attention to the reinvention and occasional rescaling of irrigated

landscapes. Recent and ongoing changes in the use of these water resources

need to be compared to former irrigation practices. Indeed, the increasing role

of ‘tradition’ in a variety of present-day development approaches urges a criti-

cal and reflexive familiarity with the existing and past geographies of irrigation.

Contemporary local-scale irrigation projects, such as the suyu arrangements of

the Laka Laka Project must be seen as having their own roots in colonial and

modern historical geographies.69 Of special importance is how these connec-

tions to the past, as well as the associated historical discontinuities, are shaping

the present-day practices of irrigation.

Irrigation planning would do well to abandon the preconceived dichotomy

of scale between local irrigation and basin irrigation schemes. The idea of a sin-

gle all-defining scale, most recently seen in local irrigation initiatives, is in need

of substantial rethinking. Local irrigation must be recognized as taking shape

in relation to key processes that operate at other scales such as the basin. This

geographical awareness can be readily applied to the monumental contrast

between local suyu irrigation under the Inca state and such recent attempts at

‘grassroots’ suyu irrigation as the Laka Laka Project. The former was integrated

with region-scale political and economic organization and resource manage-

ment. Those articulations stand in sharp contrast to most current projects of

canal-based irrigation that lack scaled-up linkages. In order to move beyond a

Ecumene 2000 7 (2)

170 Karl S. Zimmerer

priori notions of scales, the current interest in local irrigation must be sensitive

to scale linkages, rescaling at multiple levels, and the joint socio-environcultural

construction of scale changes. Such awareness will improve the assessment of

small-scale irrigation and should improve its future viability.

Acknowledgments

I am grateful for the comments and the collaboration of Luís Rojas, Suzy

Portillo, Jorge Santanalla, Guido Gúzman, Susan Paulson, Florencia Mallon,

Steve Stern, Margarita Zamora, William M. Denevan, Yi-Fu Tuan, Thomas Vale,

and Robert Sack. Special thanks to the Ecumene reviewers and to Don Mitchell.

Thanks to the Wisconsin Humanities Research Institute and the Berkeley

Environmental Politics Workshop for their generous comments and insights.

Notes

1

For examples see P. Sijbrandig and P. van der Zaag. ‘Canal maintenance: a key to

restructuring irrigation management’, Irrigation and Drainage Systems 7 (1993), pp.

189–204; D.W. Guillet, Covering ground: Communal water management and the state in the

Peruvian highlands (Ann Arbor, University of Michigan Press, 1992); P. H. Gelles,

‘Channels of power, fields of contention: the politics of irrigation and land recovery

in an Andean peasant community’, in W. P. Mitchell and D. Guillet, eds, The social

organization of water control systems in the Andes (Washington, DC, American

Anthropological Association, 1994), pp. 233–74; G. Knapp, Riego precolonial y tradi-

cional en la sierra norte del Ecuador (Quito: Abya-Yala, 1992); W. E. Doolittle, Canal irri-

gation in prehistoric Mexico (Austin: University of Texas Press, 1990); W.P. Mitchell,

‘Irrigation and community in the Central Peruvian highlands’, American Anthropologist

78 (1976), pp. 35–44; R. C. Hunt and E. Hunt, ‘Canal irrigation and local social orga-

nization’, Current Anthropology 17 (1976), pp. 388–411.

2

For examples see D. Barkin and T. King, Regional economic development: the river basin

approach in Mexico (Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, 1970); F. Posada, J.

Antonio, and J. de Posada, The CVC: challenge to underdevelopment and traditionalism.

(Bogotá, Ediciones Tercer Mundo, 1966); J. O. Maos, The spatial organization of new

land settlement in Latin America (Boulder, Westview Press, 1984); M. E. Murphy, Irrigation

in the Bajío region of colonial Mexico (Boulder, Westview Press, 1986).

3

Within the broad scope of geographical cultural ecology I refer especially to a criti-

cal political ecology ‘which works from an ecocentric view of the biophysical envi-

ronment but stresses social forces as the major causal factors’. See Buttel and

Sunderlin, cited in J. Friedmann and H. Rangan, eds, In defense of livelihood (West

Hartford, Kumarian Press, 1993), p. 3. This sort of political ecology is elabourated on

in other descriptions. See K. S. Zimmerer, ‘Ecology as cornerstone and chimera in

human geography’, in C. Earle, K. Mathewson, and M. S. Kenzer, eds, Concepts in

human geography (London, Rowman & Littlefield, 1996), pp. 161–88, and R. Peet and

M. Watts, eds, Liberation ecology: environment, development, social movements (London,

Routledge, 1996). It also resembles the idea of a political ecology ‘that is rooted in

productions of nature that hold environcultural concerns in tension with social, cul-

tural, and political economic considerations’. See C. Katz, ‘Whose nature, whose cul-

ture? private productions of space and the ‘preservation’ of nature’, in B. Braun and

N. Castree, eds, Remaking reality: nature at the millennium (London, Routledge, 1998),

pp. 46–63.

Ecumene 2000 7 (2)

Rescaling irrigation in Latin America 171

4

The powerful critique and criticisms of modern Western development schemes cen-

tred on irrigated agriculture have been a major impetus for the ‘grassroots,’ ‘local,’

and ‘sustainable development’ approaches. This study’s perspective on these

approaches is informed by such works as Peet and Watts, Liberation ecology; J. Crush,

ed, Power of development (London, Routledge, 1995); S. Corbridge, ‘Third World devel-

opment’, Progress in Human Geography 15 (1991), pp. 311–21; A. Escobar, Encountering

development: the making and unmaking of the Third World (Princeton, Princeton University

Press, 1995). My study is engaged with specific aspects of these critques in the next

section.

5

See, for example, E. Goldsmith, ‘Learning to live with nature: the lessons of tradi-

tional irrigation’, Ecologist 28 (1998), pp. 162–70.

6

Examples of this perspective include the following: E. Swyngedouw, ‘Neither global

nor local: “glocalization” and the politics of scale’, in K. R. Cox, ed., Spaces of global-

ization: reasserting the power of the local (New York, Guilford Press, 1997), pp. 137–66;

N. Smith, ‘Homeless/global: scaling places’, in J. Bird, B. Curtis, T. Putnam, G.

Robertson, and L. Tickner, eds, Mapping the futures: local cultures, global change

(London, Routledge, 1993), pp. 89–119; A. Herod, ‘The production of scale in United

States labour relations’, Area 23 (1991), pp. 82–8; A. Pred and M. J. Watts, Reworking

modernity: capitalisms and symbolic discontent (New Brunswick, Rutgers University Press,

1992); D. Harvey, Justice, nature, and the geography of difference (Oxford, Blackwell, 1996).

7

T. J. Bassett and K. S. Zimmerer, ‘Cultural ecology in the 1990s’, in G. Gaile and C.

Wilmott, eds, Geography in America, Benchmark 2000 (Oxford, Oxford University Press,

1999); B. L. Turner II, ‘Spirals, bridges, and tunnels: engaging human–environment

perspectives in geography’, Ecumene 4 (1997), pp. 196–217; Zimmerer, ‘Ecology as cor-

nerstone and chimera’; K. S. Zimmerer, ‘Introduction: geographies of landscape

change’, in K. S. Zimmerer and K. R. Young, eds, Nature’s geography: new lessons for

conservation in developing countries (Madison, University of Wisconsin Press, 1998), pp.

3–38. See also Peet and Watts, Liberation ecologies; P. Parajuli, ‘Beyond capitalized

nature: ecological ethnicity as an arena of conflict in the regime of globalization’,

Ecumene 5 (1998), pp. 186–217. The grouping together of these approaches under the

label ‘geographical cultural ecology’ is based on their common ground, a defining

interest in the relations of people to the environment. Grouping for this purpose does

not downplay the differences among these approaches within the people–environ-

ment area.

8

R. Fardon, Counterworks: managing the diversity of knowledge (London, Routledge, 1995),

pp. 2–21; O. Harris, ‘Knowing the past: plural identities and the antinomies of loss

in Highland Bolivia’, in Fardon, Counterworks, pp. 105–23.

9

See, for example, E. Hobsbawm and T. Ranger, eds, The invention of tradition

(Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, 1983).

10

K. S. Zimmerer, Changing fortunes: biodiversity and peasant livelihood in the Peruvian Andes

(Berkeley and Los Angeles, University of California Press, 1996).

11

C. Zerner, ‘Through a green lens: The construction of customary environcultural law

and community in Indonesia’s Maluku Islands’, Law and Society Review 28 (1994),

pp.1079–1122; C. Zerner, ‘Transforming customary law and coastal management prac-

tices in the Maluku Islands, Indonesia, 1870-1992’ in D. Western and R. M. Wright,

eds, Natural connections: perspectives in community-based conservation (Covalo, CA, Island

Press, 1994), pp. 80–112.

12

A similar emphasis is found, for example, in the works of Vandergeest. See P.

Vandergeest, ‘Mapping nature: territorialization of forest rights in Thailand’, Society

and Natural Resources 9 (1996), pp. 159–75.

Ecumene 2000 7 (2)

172 Karl S. Zimmerer

13

These ecological ideas centred around assumptions of spatial and temporal stability,

together with the opposing theoretical directions of current trends in ecology, are an

area of considerable promise for the rethinking of human–environment relations, and

are especially significant for the proliferating environment–development projects that

include conservation and environmentally sound or sustainable resource use. See K.

S. Zimmerer, ‘The reworking of conservation geographies: non-equilibrium land-

scapes and nature–society hybrids’, Annals of the Association of American Geographers 90

(2000), pp. 251–76.

14

C. Sage, ‘Intensification of commodity relations: agricultural specialization and dif-

ferentiation in the Cochabamba serranía, Bolivia’, Bulletin of Latin American Research

3 (1984), pp. 81–97; M. Lagos, Autonomy and power: the dynamics of class and culture in