Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Pronouncing Arabic

Pronouncing Arabic

Uploaded by

Roni Bou SabaCopyright:

Available Formats

You might also like

- Complete Modern Persian Avasshop 231205 094443Document399 pagesComplete Modern Persian Avasshop 231205 094443Raúl RodríguezNo ratings yet

- Skillin, Marjorie E. & Robert M. Gay - Words Into Type, 3e (1974)Document611 pagesSkillin, Marjorie E. & Robert M. Gay - Words Into Type, 3e (1974)Roni Bou Saba100% (14)

- Speech Opening & ClosingDocument2 pagesSpeech Opening & ClosingAgus Sugito86% (22)

- Classical Arabic and The Gulf PDFDocument14 pagesClassical Arabic and The Gulf PDFfhmjnuNo ratings yet

- Spoken LebDocument233 pagesSpoken LebSilviana Abou Nassif Grigore91% (32)

- 2001 MALEK BENNABI and ASMA RASHID - The Conditions of RenaissanceDocument11 pages2001 MALEK BENNABI and ASMA RASHID - The Conditions of Renaissancees23440% (1)

- Persian Conversation GrammarDocument410 pagesPersian Conversation GrammarRoxana BerteanuNo ratings yet

- Chinese Middle ConstructionsDocument232 pagesChinese Middle ConstructionsJason CullenNo ratings yet

- Comparative Morphology of Standard and EDocument260 pagesComparative Morphology of Standard and EknopeNo ratings yet

- Pali Verb Conjugation 1 X A4Document1 pagePali Verb Conjugation 1 X A4Nyanatusita BhikkhuNo ratings yet

- W3 - Hanyu PinyinDocument40 pagesW3 - Hanyu Pinyin趙靜雅-Chingya ChaoNo ratings yet

- Pronunciation Arabic PDFDocument4 pagesPronunciation Arabic PDFSara EldalyNo ratings yet

- ArabicsDocument176 pagesArabicsMia GeorgianaNo ratings yet

- User Friendly Pashto Text EditorDocument9 pagesUser Friendly Pashto Text EditorIjaems JournalNo ratings yet

- Sanskrit An Introduction To The Classical Language by Michael Coulson Teach Yourself Books PP XXX 493 London Hodder and Stoughton 1976 295Document2 pagesSanskrit An Introduction To The Classical Language by Michael Coulson Teach Yourself Books PP XXX 493 London Hodder and Stoughton 1976 295Vani84No ratings yet

- Pinyin (声韵母拼合表)Document2 pagesPinyin (声韵母拼合表)William LiNo ratings yet

- Shariah ProgramDocument17 pagesShariah Programbasyll73No ratings yet

- EngPaliGrammar W.audioDocument42 pagesEngPaliGrammar W.audioDR PRABHAT TANDONNo ratings yet

- Tajweed Qur'AnDocument58 pagesTajweed Qur'AnZiedZiednNo ratings yet

- Buddhism in ThailandDocument128 pagesBuddhism in ThailandHistorica VariaNo ratings yet

- A Vest An CompleteDocument312 pagesA Vest An CompleteNeil YangNo ratings yet

- Fazail e Ahlulbait (A.s.) Vol 1Document75 pagesFazail e Ahlulbait (A.s.) Vol 1FazaileAhlulbaitNo ratings yet

- Accent Handbook Paper RevisedDocument50 pagesAccent Handbook Paper RevisedMarko ŠindelićNo ratings yet

- Burmese LanguageDocument47 pagesBurmese LanguageNanissaro BhikkhuNo ratings yet

- English Adverbs DictionaryDocument37 pagesEnglish Adverbs DictionaryBharti DograNo ratings yet

- Arabic Learning Resources - English Legal TermsDocument31 pagesArabic Learning Resources - English Legal TermsAumnia JamalNo ratings yet

- El Dari El Persa y El Tayiko en Asia CentralDocument22 pagesEl Dari El Persa y El Tayiko en Asia CentralAlberto Franco CuauhtlatoaNo ratings yet

- Pali Chinese DictionaryDocument374 pagesPali Chinese DictionaryMyomyat Thu100% (1)

- Simple Sentence Structure of Standard Arabic Language PDFDocument25 pagesSimple Sentence Structure of Standard Arabic Language PDFtomasgouchaNo ratings yet

- Pali Compounds - Ven. PanditaDocument6 pagesPali Compounds - Ven. PanditakithaironNo ratings yet

- A Dictionary of Colloquial Idioms in The Mandarin Dialect (1873)Document150 pagesA Dictionary of Colloquial Idioms in The Mandarin Dialect (1873)김동훈No ratings yet

- Siyar Al Laam An Nubala SiyarDocument4 pagesSiyar Al Laam An Nubala SiyarScribdTranslationsNo ratings yet

- List of Shia Books WikipediaDocument8 pagesList of Shia Books WikipediaSagar RazaNo ratings yet

- Ancient Greek Grammar PartDocument25 pagesAncient Greek Grammar PartAndyEssayerNo ratings yet

- Norman, K. R., Pali Philology & The Study of BuddhismDocument13 pagesNorman, K. R., Pali Philology & The Study of BuddhismkhrinizNo ratings yet

- Syllabus For M.A. Arabic 2018 OnwardsDocument72 pagesSyllabus For M.A. Arabic 2018 OnwardsAaqib Ibn RiyaadhNo ratings yet

- Unicode - ARABIC SCRIPT TUTORIALDocument16 pagesUnicode - ARABIC SCRIPT TUTORIALalqudsulana89100% (4)

- Siva Sutra PaperDocument16 pagesSiva Sutra PaperShivaram Reddy ManchireddyNo ratings yet

- A Complete Grammar of Esperanto by Reed, Ivy Kellerman, 1877-1968Document243 pagesA Complete Grammar of Esperanto by Reed, Ivy Kellerman, 1877-1968Gutenberg.org100% (3)

- Traditional - Tools in Pali Grammar Relational Grammar and Thematic Units - U Pandita BurmaDocument31 pagesTraditional - Tools in Pali Grammar Relational Grammar and Thematic Units - U Pandita BurmaMedi NguyenNo ratings yet

- Fazail e Ahlulbait (A.s.) Vol 2Document77 pagesFazail e Ahlulbait (A.s.) Vol 2FazaileAhlulbait100% (1)

- An Arabic English 00 Came GoogDocument615 pagesAn Arabic English 00 Came GoogRaven Synthx100% (1)

- Sulu Writing PDFDocument193 pagesSulu Writing PDFMitch Delos Santos LuzonNo ratings yet

- The ExpositorDocument301 pagesThe ExpositorAndreina AragonesesNo ratings yet

- Four Advanced Persian Reading UnitsDocument50 pagesFour Advanced Persian Reading UnitsJavier HernándezNo ratings yet

- Why Should We Learn ArabicDocument12 pagesWhy Should We Learn ArabicMohammed EliyasNo ratings yet

- Index of Tangut Characters With Corresponding Tibetan Phonetic GlossesDocument15 pagesIndex of Tangut Characters With Corresponding Tibetan Phonetic GlossesJerry YouNo ratings yet

- Yoyo Chinese Pinyin 2019Document3 pagesYoyo Chinese Pinyin 2019joe wongNo ratings yet

- The University of Chicago PressDocument7 pagesThe University of Chicago PressОктай СтефановNo ratings yet

- TheLifeOfTheProphetMuhammad EnglishTranslationOfIbnKathirsAlSiraAlNabawiyyaVolume3 PDFDocument543 pagesTheLifeOfTheProphetMuhammad EnglishTranslationOfIbnKathirsAlSiraAlNabawiyyaVolume3 PDFkishorebooksscribdNo ratings yet

- TheLifeOfTheProphetMuhammad-EnglishTranslationOfIbnKathirsAlSiraAlNabawiyyaVolume3 (1-100)Document100 pagesTheLifeOfTheProphetMuhammad-EnglishTranslationOfIbnKathirsAlSiraAlNabawiyyaVolume3 (1-100)NASSRONo ratings yet

- Hal Kin 1951Document3 pagesHal Kin 1951Anonymous MGG7vMINo ratings yet

- Ismail R Al FaruqiDocument30 pagesIsmail R Al Faruqisiti aisyahNo ratings yet

- Writing and Cultural Influence Studies in Rhetorical History Orientalist Discourse and Post Colonial Criticism Comparative Cultures and Literature PDFDocument157 pagesWriting and Cultural Influence Studies in Rhetorical History Orientalist Discourse and Post Colonial Criticism Comparative Cultures and Literature PDFnaciye tasdelen100% (1)

- Egyptian Manual of Karaite FaithDocument12 pagesEgyptian Manual of Karaite FaithTommy García100% (1)

- Varisco - Metaphors and Sacred History The Genealogy of Muhammad and The Arab TribeDocument19 pagesVarisco - Metaphors and Sacred History The Genealogy of Muhammad and The Arab TribeRaas4555No ratings yet

- Havelock Eric A The Muse Learns To Write Reflections On Orality and Literacy From Antiquity To The Present PDFDocument156 pagesHavelock Eric A The Muse Learns To Write Reflections On Orality and Literacy From Antiquity To The Present PDFGiselle González Camacho100% (2)

- About Taha HusseinddddddddddddddddddddddddddddDocument20 pagesAbout Taha HusseinddddddddddddddddddddddddddddbascutaNo ratings yet

- The Johns Hopkins University Press The American Journal of PhilologyDocument3 pagesThe Johns Hopkins University Press The American Journal of PhilologyahmadarinalhaqNo ratings yet

- KK-Adi Setia - The Genesis of Greek Intellectuality in Islamic and Western Historiographes of ScienceDocument22 pagesKK-Adi Setia - The Genesis of Greek Intellectuality in Islamic and Western Historiographes of ScienceNoor Aisyah Binti SajuniNo ratings yet

- Barbarians in Arab EyesDocument17 pagesBarbarians in Arab EyesMaria MarinovaNo ratings yet

- Ilm Al Wad A Philosophical AccountDocument19 pagesIlm Al Wad A Philosophical AccountRezart Beka100% (1)

- 2 PDFDocument25 pages2 PDFJawad QureshiNo ratings yet

- Arabicus FelixDocument4 pagesArabicus FelixThinker's NotePadNo ratings yet

- أبو العلاء المعري اللزوميات- مختاراتDocument401 pagesأبو العلاء المعري اللزوميات- مختاراتRoni Bou SabaNo ratings yet

- FSI Levantine Arabic Course - Live Lingua - PDF RoomDocument105 pagesFSI Levantine Arabic Course - Live Lingua - PDF RoomRoni Bou SabaNo ratings yet

- محمود درويش- ذاكرة للنسيانDocument235 pagesمحمود درويش- ذاكرة للنسيانRoni Bou SabaNo ratings yet

- Kymati ThalasisDocument26 pagesKymati ThalasisRoni Bou SabaNo ratings yet

- A Transformational Grammar of Modern Literary Arabic - PDF RoomDocument223 pagesA Transformational Grammar of Modern Literary Arabic - PDF RoomRoni Bou SabaNo ratings yet

- Folk Stories and Personal Narratives in Palestinian Spoken Arabic - A Cultural and Linguistic Study - PDF RoomDocument269 pagesFolk Stories and Personal Narratives in Palestinian Spoken Arabic - A Cultural and Linguistic Study - PDF RoomRoni Bou SabaNo ratings yet

- كليلة ودمنة 1905Document363 pagesكليلة ودمنة 1905Roni Bou SabaNo ratings yet

- Interpretation ReceptionDocument29 pagesInterpretation ReceptionRoni Bou SabaNo ratings yet

- Interpretation ReceptionDocument29 pagesInterpretation ReceptionRoni Bou SabaNo ratings yet

- Bint El ShalabiyaDocument1 pageBint El ShalabiyaRoni Bou SabaNo ratings yet

- Arabic Grammar - ExercisesDocument167 pagesArabic Grammar - ExercisesRaza Bin MuhammadNo ratings yet

- Ruth B Edwards Kadmos The Phoenician A Study in Greek Legends and The Mycenaean AgeDocument280 pagesRuth B Edwards Kadmos The Phoenician A Study in Greek Legends and The Mycenaean AgeRoni Bou Saba100% (7)

- 000644a WWW - AlDocument1,060 pages000644a WWW - AlRoni Bou SabaNo ratings yet

- الجماهر في معرفة الجواهر للبيرونيDocument160 pagesالجماهر في معرفة الجواهر للبيرونيRoni Bou SabaNo ratings yet

- TDS Introduction Language Verse HomerDocument110 pagesTDS Introduction Language Verse HomerRoni Bou SabaNo ratings yet

- Quranic Gems - Juz 25Document2 pagesQuranic Gems - Juz 25Dian HandayaniNo ratings yet

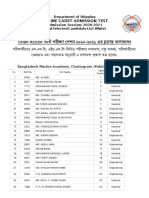

- Admission Result, 1st TimeDocument32 pagesAdmission Result, 1st TimeAli HasanNo ratings yet

- NDU MPhil GAT G Results Spring 2023Document3 pagesNDU MPhil GAT G Results Spring 2023Muhammad Abdul BasitNo ratings yet

- Al Wala Wal BaraDocument138 pagesAl Wala Wal BaraAgustang PuunanggaNo ratings yet

- Hasil Efo-Jt Potential Basic Test1Document28 pagesHasil Efo-Jt Potential Basic Test1u2urhfNo ratings yet

- LITERATUREDocument47 pagesLITERATUREansif anwerNo ratings yet

- 11 Conclusion PDFDocument4 pages11 Conclusion PDFSunny TuvarNo ratings yet

- Why Did Mohammed Get So Many WivesDocument22 pagesWhy Did Mohammed Get So Many WivesSikhSangat BooksNo ratings yet

- Male by CourseDocument19 pagesMale by CourseMohamed AymanNo ratings yet

- Charles GOUNOD: Quinze Melodies Enfantines, Pour Voix Et PianoDocument58 pagesCharles GOUNOD: Quinze Melodies Enfantines, Pour Voix Et PianoEmre ÇetinerNo ratings yet

- Midterm - Shariah IVDocument15 pagesMidterm - Shariah IVchaeny limNo ratings yet

- The Muslim AlmanacDocument1 pageThe Muslim Almanacapi-3710484No ratings yet

- Sir Syed Ahmed KhanDocument2 pagesSir Syed Ahmed Khansanali_81No ratings yet

- 10.1108@ijlma 03 2017 0027Document10 pages10.1108@ijlma 03 2017 0027Bertina AyuNo ratings yet

- Commentary Sura HujuratDocument313 pagesCommentary Sura HujuratMubahilaTV Books & Videos Online100% (1)

- Https Sites - Google.com Site Nusayrilight Home Texts-In-Arabic TMPL /system/app/templates/print/&showPrintDialog 1 PDFDocument4 pagesHttps Sites - Google.com Site Nusayrilight Home Texts-In-Arabic TMPL /system/app/templates/print/&showPrintDialog 1 PDFHazem ShehadehNo ratings yet

- Islamic and Cordillera ArtDocument4 pagesIslamic and Cordillera ArtDiana TanzaNo ratings yet

- Maulidur Rasul Booklet PDFDocument32 pagesMaulidur Rasul Booklet PDFMuhammad IdrusNo ratings yet

- Kelompok Manajemen Farmasi Kelas CDDocument6 pagesKelompok Manajemen Farmasi Kelas CDZaza SaskiaNo ratings yet

- StudentsDocument75 pagesStudentsMilad AkbariNo ratings yet

- Islamic Studies (New-Revised) Course OutlineDocument4 pagesIslamic Studies (New-Revised) Course OutlineMushtak Mufti0% (1)

- Islamic Tourism and Managing TourismDocument11 pagesIslamic Tourism and Managing TourismHenry Farrisch NorteNo ratings yet

- p4 Social Studies Final Test Semester 1Document3 pagesp4 Social Studies Final Test Semester 1wilsonNo ratings yet

- Qur Qur Nic Spell-Ing: Disconnected Letter Series in Islamic Talismans Nic Spell-Ing: Disconnected Letter Series in Islamic TalismansDocument28 pagesQur Qur Nic Spell-Ing: Disconnected Letter Series in Islamic Talismans Nic Spell-Ing: Disconnected Letter Series in Islamic TalismansCarlosNo ratings yet

- Al-Muhannad 'Ala Al-Mufannad TranslationDocument34 pagesAl-Muhannad 'Ala Al-Mufannad TranslationdhumplupukaNo ratings yet

- Hasil To Utbk 4 - SoshumDocument25 pagesHasil To Utbk 4 - Soshumcristinajuniarti hutabaratNo ratings yet

- Preservation of The Sunnah ARTICLEDocument15 pagesPreservation of The Sunnah ARTICLEJ ZarabozoNo ratings yet

- Qureshi Family Information EnglishDocument2 pagesQureshi Family Information EnglishDr. Syed Danish ShahNo ratings yet

Pronouncing Arabic

Pronouncing Arabic

Uploaded by

Roni Bou SabaOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Pronouncing Arabic

Pronouncing Arabic

Uploaded by

Roni Bou SabaCopyright:

Available Formats

Pronouncing Arabic by T. F.

Mitchell

Review by: Alan S. Kaye

Journal of the American Oriental Society, Vol. 112, No. 1 (Jan. - Mar., 1992), pp. 137-138

Published by: American Oriental Society

Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/604599 .

Accessed: 18/06/2014 02:32

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at .

http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp

.

JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of

content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms

of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org.

American Oriental Society is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Journal of

the American Oriental Society.

http://www.jstor.org

This content downloaded from 195.78.109.119 on Wed, 18 Jun 2014 02:32:46 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Reviews of Books 137

the cult of the book, in the cult of eloquence, in the Pronouncing Arabic. By T. F. MITCHELL.Oxford: CLARENDON

methodology of instruction, in self-teaching, in all PRESS, 1990. Pp. xii + 167. $49.95.

phases of the humanist community, both the amateur

and the professional, in the relationship between hu- Every Arabist working today knows (or should know) some

manism and law, in the art of the notary and the episto- of the outstanding research published over the past four de-

lary art, in the florilegia and the formularies of letters cades by one of Great Britain's most erudite specialists in

and formal legal documents, in many-sidedness, in the Arabic linguistics, T. F. Mitchell, Professor of Linguistics

cult of fame and glory, in the practice of ridicule and Emeritus at the University of Leeds, formerly at the School of

wit, in individualism generally and in many other as- Oriental and African Studies, University of London. This

pects . . . (pp. 348-49). book was already in the making some thirty-eight years ago as

Mitchell's WritingArabic (Oxford University Press, 1953) al-

Makdisi refutes the "common spirit" theory (that is supposed ready made reference to it. Happily for Arabic studies, it is

to have hovered over the Mediterraneanworld in the Middle now a reality. One will instantly recognize both Mitchell's

Ages), not just by a clever reference to the colonial poetics of Firthianbackground, including a solid knowledge of phonetics

Rudyard Kipling ("East is East and West is West, And never a la Daniel Jones, and his reliance on the excellent and pio-

the twain shall meet"), but by the more compelling argument neering The Phonetics of Arabic by W. H. T. Gairdner (Ox-

that the common spirit was not at the north and south, east and ford University Press, 1925). As Mitchell notes in appendix B

west of the Mediterranean simultaneously, and that "both

(pp. 156-58), almost all the Arabic phonetic terms used are

movements [scholasticism and humanism] find their raison

discussed by Gairdner (1925), such as 'imalah 'closing and/or

d'etre in classical Islam, from their genesis to their full devel-

fronting of fathah', 'itbaq 'full emphaticization or emphasis',

opment, involving a long historical process. In the Christian and so on.

West both movements came upon the scene in the second half

Mitchell's prose is both accurate and illuminating, and thus

of the eleventh century, without an adequate Western histori-

the book can be highly recommended for students and special-

cal background . . ." (p. 349).

ists, too. It might seem strange to witness the use of the term

When otherwise perfectly serious scholars, whom Makdisi

"guttural"(p. 32 and passim; Arabic halqf) in a modem lin-

identifies simply as "Eurocentric historians," are willing and

guistic treatise, referring to the natural class of /x, gh, h, c, h,

able to refer to "a spontaneous movement of the human mind"

and '/; however, I believe this term is still justifiable, since

for the origin of universities, or to a "mysterious urge" for the

those consonants share a similar morphophonemic behavior

rise of humanism, an innate socio-psychological barrier must

by preferring, e.g., a fathah as the vowel of the imperfect

be in operation much stronger than the possibility of scholarly

stem. As Mitchell writes (ibid.), this tendency is more observ-

open-mindedness. Makdisi is rathertimid in his indictment:

able in colloquial dialects than in Classical Arabic, yet any

Except for some scholars of broad vision, Western his- Arabist who is familiar with Hebrew morphophonology will

torians have thus been at odds on the matter of influ- readily admit that the term "guttural"makes sense for many of

ence from classical Islam on the Christian West, the Semitic languages. Mitchell (ibid.) also correctly points

leading them to span the spectrum, from positing the out that the gutturals as a group have incompatibility in their

common spirit theory, to declaring the utter otherness root-patterningcapabilities.

of two opposed spirits. Although contradictory, both The Arabic pronunciation described by Mitchell reflects an

theories aim at the same result. For with either theory, educated Egyptian (i.e., Cairene, very much in the "Azhari"

there would be no use to discuss even the possibility of tradition) interpretation of the Arabic graphemes with, of

influence from Islam on the West; with either theory, course, some influence of the spoken colloquial dialect, which

the parallels are simply parallels, nothing else (p. 349). Mitchell characterizes as "a more relaxed reading style"

(p. 154). One such instance which is very common is the

What Makdisi leaves blank between his carefully constructed omission of the final -h of the pausal pronunciation of the td'

paragraphsis the source and significance of the tension, of the marbfitah.It is, however, in matters of accentuation (pp. 102-

negation of any outside influence-particularly that of Is- 17) where one most easily notices the Egyptian vernacular

lam-on the "West." That, however, is the power of a myth. influence imposed on both Modern StandardArabic and Clas-

And precisely for that reason, Makdisi's magnificent book sical Arabic (however, Qur'dnic recitation and chant, i.e.,

will, once again, face resistance in having its argument con- tajwfd, are beyond what Mitchell tries to do in the book, al-

sidered seriously by Eurocentric Medievalists. though the faatihah 'opening sara of the Koran' (not fatfihah,

p. 154) is dealt with. Mitchell discusses this continuum of ver-

HAMID DABASHI

nacular influence by pointing out: "In general, from a phonetic

COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY

standpoint, the degree of divergence from vernacular practice

may be used to assess the 'grade' of Classical pronunciation-

This content downloaded from 195.78.109.119 on Wed, 18 Jun 2014 02:32:46 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

138 Journal of the American Oriental Society 112.1 (1992)

the greater the divergence, the more Classical the perfor- Mitchell's book is absolutely first rate, and there are many

mance" (p. 102). other points I would have liked to discuss in a longer review,

Egyptian pronunciation is chosen by Mitchell because, in such as his discovery of clicks in Arabic dialects (as in Zulu,

addition to Egypt's being the most populous Arab country, Hottentot, and Bushman) (see p. 44 for the report concerning

with a corresponding admirationof and respect for its pronun- the Al-Karnakdialect of Qena, Upper Egypt). Two of his pho-

ciation tradition, there is a norm based on the speech of the netic claims, however, await further research (p. 56). First, he

Culamad' of Al-Azhar, Dar al-cUlum, and various other organi- states that Moroccan Arabic, e.g., has a pharyngeal stop as a

zations and universities. As is well known, the facts of which variant of /q/, yet there is no IPA symbol for such a consonant

syllable to stress in polysyllabic Arabic words differ remark- because, as almost all have claimed, pharyngeal stops are

ably throughout the Arab world. For an Egyptian from Cairo, (supposedly) impossible to produce. Secondly, he maintains

for instance, even the same word has a different stress pattern that "in much of Syria, Kuwait, and Iraq, ' is usually glottal-

(due to different syllabic structure)depending on whether it is ized, i.e., pronounced with a simultaneous glottal stop, but in

a pausal form or not: mu'allimun 'teacher' (masculine, nom. Egypt, North Africa, and much of the Levant, ' is simply the

sg.) but mu'dllim. I shall not dwell here on these tricky de- voiced counterpartof h" (p. 56). I am skeptical about this be-

tails, except to note that native Arabic speakers from different cause if this were true, then one could (very frequently) tell a

areas in reading standard Arabic katabatd 'they (fem. dual) Syrian from an Egyptian, simply by this one difference of

wrote' may stress any of the four syllables and still be correct glottalization-a feat which is, in my opinion, not easily

(Egyptians from Cairo pronounce katabdtd; cf. the Cairene accomplished.

pronunciation kdtdibata'they (fem. dual) corresponded with'.

These facts are but part of the story of why I deemed Modern ALAN S. KAYE

StandardArabic to be ill-defined, but all colloquial dialects to CALIFORNIA STATE UNIVERSITY, FULLERTON

be well-defined (see my "Modern Standard Arabic and the

Colloquials," Lingua 24.4 [1970]: 374-91, 412). Indeed one

can spot a Lebanese pronunciation in katabata, a Jordanian

one in katdbatd, and an Upper Egyptian one in kditabatd.

Another typical case of the interference of colloquial The Isma'ilis: Their History and Doctrines. By FARHAD

Cairene on Modern Standard Arabic pronunciation is in the DAFTARY. Cambridge: CAMBRIDGE UNIVERSITY PRESS, 1990.

matter of the unvoicing of final consonant clusters, "particu- Pp. xviii + 804.

larly noticeable with final liquids" such as hus~n 'beauty'

(p. 98). This is probably a very old feature in Cairene, and one In 1973 the new Encyclopaedia of Islam published an article

can see a parallel with other Arabic dialects such as Nigerian by Wilferd Madelung on the "Isma'iliyya." At the time this ar-

Arabic [juwdpm I (the raised m refers to a nasal plosion) 'an- ticle seemed both a model summaryof all that had been discov-

swer' (MSA jawdb) and Maltese biep 'gate' (MSA bdb). Con- ered about the history and doctrines of this obscure and difficult

cerning the latter development of devoicing, it should be kept Shi'ite sect and an outline for a much largerstudy of it. Because

in mind that Maltese has other non-Maghribine features, too the Ismailis have existed in so many differentforms, and at both

(and thus, in my view, cannot be considered a North-African the center and at the peripheryof the Islamic world, few scholars

Arabic dialect although, to be sure, it does have many affini- other than Madelung were conversant with all of these phases

ties with the Maghribine dialects), such as Arabic /q/ > Mal- and manifestations. Nevertheless, the importance of tracing all

tese /D/, written as q (as in Cairene and elsewhere), and Arabic this in a single account is undeniable: the Ismailis are a prime

P! > Maltese 0, which is not written in the language. example of a continuous sub-movement within the Islamic con-

I save for last a discussion of the hamzatuIwasl (pp. 93-98) text over at least a millennium.

since this is an importantproblem in comparativeArabic dialec- As useful as the EI article was, however, it provided only

tology. While I can agree, for the most part, with Mitchell's ob- an outline of the subject, almost as if to indicate the promise

servations on words such as 'iDndni 'two', 'ibn 'son', 'ibnah of a full-length study. With the recent appearance of this

'daughter', 'ist 'buttock', 'imra' 'man', 'imra'ah 'woman' (note major work by Farhad Daftary, that promise has now been

that 'alimra'ah 'the woman' is also possible in addition to the achieved. Here at last is a complete account of the Ismailis,

cited 'almar'ah, p. 93), I have pointed out the evidence for a bringing together in one volume the history of such individual

word such as 'ism 'name'(ibid.) as its hamzatuIwasl has shifted groups as the Carmatians, the Fatimids, the Assassins, the

over to the hamzatu lqatc category. See my "The Hamzat al- Khojas and Bohras, to name only major phases.

Wasl in ContemporaryModem Standard Arabic," JAOS III Madelung had already indicated a rich collection of earlier

(1991): 572-73. It is interestingto note the vowel-shortening of partial studies. Daftary, whose academic training was not orig-

md 'what'in ma smuk'what'syour name?' in addition to the very inally in Islamic history, therefore found many facets of

classical elision of the glottal stop of 'ism (p. 95). Ismaili studies reasonably well documented. To these, how-

This content downloaded from 195.78.109.119 on Wed, 18 Jun 2014 02:32:46 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

You might also like

- Complete Modern Persian Avasshop 231205 094443Document399 pagesComplete Modern Persian Avasshop 231205 094443Raúl RodríguezNo ratings yet

- Skillin, Marjorie E. & Robert M. Gay - Words Into Type, 3e (1974)Document611 pagesSkillin, Marjorie E. & Robert M. Gay - Words Into Type, 3e (1974)Roni Bou Saba100% (14)

- Speech Opening & ClosingDocument2 pagesSpeech Opening & ClosingAgus Sugito86% (22)

- Classical Arabic and The Gulf PDFDocument14 pagesClassical Arabic and The Gulf PDFfhmjnuNo ratings yet

- Spoken LebDocument233 pagesSpoken LebSilviana Abou Nassif Grigore91% (32)

- 2001 MALEK BENNABI and ASMA RASHID - The Conditions of RenaissanceDocument11 pages2001 MALEK BENNABI and ASMA RASHID - The Conditions of Renaissancees23440% (1)

- Persian Conversation GrammarDocument410 pagesPersian Conversation GrammarRoxana BerteanuNo ratings yet

- Chinese Middle ConstructionsDocument232 pagesChinese Middle ConstructionsJason CullenNo ratings yet

- Comparative Morphology of Standard and EDocument260 pagesComparative Morphology of Standard and EknopeNo ratings yet

- Pali Verb Conjugation 1 X A4Document1 pagePali Verb Conjugation 1 X A4Nyanatusita BhikkhuNo ratings yet

- W3 - Hanyu PinyinDocument40 pagesW3 - Hanyu Pinyin趙靜雅-Chingya ChaoNo ratings yet

- Pronunciation Arabic PDFDocument4 pagesPronunciation Arabic PDFSara EldalyNo ratings yet

- ArabicsDocument176 pagesArabicsMia GeorgianaNo ratings yet

- User Friendly Pashto Text EditorDocument9 pagesUser Friendly Pashto Text EditorIjaems JournalNo ratings yet

- Sanskrit An Introduction To The Classical Language by Michael Coulson Teach Yourself Books PP XXX 493 London Hodder and Stoughton 1976 295Document2 pagesSanskrit An Introduction To The Classical Language by Michael Coulson Teach Yourself Books PP XXX 493 London Hodder and Stoughton 1976 295Vani84No ratings yet

- Pinyin (声韵母拼合表)Document2 pagesPinyin (声韵母拼合表)William LiNo ratings yet

- Shariah ProgramDocument17 pagesShariah Programbasyll73No ratings yet

- EngPaliGrammar W.audioDocument42 pagesEngPaliGrammar W.audioDR PRABHAT TANDONNo ratings yet

- Tajweed Qur'AnDocument58 pagesTajweed Qur'AnZiedZiednNo ratings yet

- Buddhism in ThailandDocument128 pagesBuddhism in ThailandHistorica VariaNo ratings yet

- A Vest An CompleteDocument312 pagesA Vest An CompleteNeil YangNo ratings yet

- Fazail e Ahlulbait (A.s.) Vol 1Document75 pagesFazail e Ahlulbait (A.s.) Vol 1FazaileAhlulbaitNo ratings yet

- Accent Handbook Paper RevisedDocument50 pagesAccent Handbook Paper RevisedMarko ŠindelićNo ratings yet

- Burmese LanguageDocument47 pagesBurmese LanguageNanissaro BhikkhuNo ratings yet

- English Adverbs DictionaryDocument37 pagesEnglish Adverbs DictionaryBharti DograNo ratings yet

- Arabic Learning Resources - English Legal TermsDocument31 pagesArabic Learning Resources - English Legal TermsAumnia JamalNo ratings yet

- El Dari El Persa y El Tayiko en Asia CentralDocument22 pagesEl Dari El Persa y El Tayiko en Asia CentralAlberto Franco CuauhtlatoaNo ratings yet

- Pali Chinese DictionaryDocument374 pagesPali Chinese DictionaryMyomyat Thu100% (1)

- Simple Sentence Structure of Standard Arabic Language PDFDocument25 pagesSimple Sentence Structure of Standard Arabic Language PDFtomasgouchaNo ratings yet

- Pali Compounds - Ven. PanditaDocument6 pagesPali Compounds - Ven. PanditakithaironNo ratings yet

- A Dictionary of Colloquial Idioms in The Mandarin Dialect (1873)Document150 pagesA Dictionary of Colloquial Idioms in The Mandarin Dialect (1873)김동훈No ratings yet

- Siyar Al Laam An Nubala SiyarDocument4 pagesSiyar Al Laam An Nubala SiyarScribdTranslationsNo ratings yet

- List of Shia Books WikipediaDocument8 pagesList of Shia Books WikipediaSagar RazaNo ratings yet

- Ancient Greek Grammar PartDocument25 pagesAncient Greek Grammar PartAndyEssayerNo ratings yet

- Norman, K. R., Pali Philology & The Study of BuddhismDocument13 pagesNorman, K. R., Pali Philology & The Study of BuddhismkhrinizNo ratings yet

- Syllabus For M.A. Arabic 2018 OnwardsDocument72 pagesSyllabus For M.A. Arabic 2018 OnwardsAaqib Ibn RiyaadhNo ratings yet

- Unicode - ARABIC SCRIPT TUTORIALDocument16 pagesUnicode - ARABIC SCRIPT TUTORIALalqudsulana89100% (4)

- Siva Sutra PaperDocument16 pagesSiva Sutra PaperShivaram Reddy ManchireddyNo ratings yet

- A Complete Grammar of Esperanto by Reed, Ivy Kellerman, 1877-1968Document243 pagesA Complete Grammar of Esperanto by Reed, Ivy Kellerman, 1877-1968Gutenberg.org100% (3)

- Traditional - Tools in Pali Grammar Relational Grammar and Thematic Units - U Pandita BurmaDocument31 pagesTraditional - Tools in Pali Grammar Relational Grammar and Thematic Units - U Pandita BurmaMedi NguyenNo ratings yet

- Fazail e Ahlulbait (A.s.) Vol 2Document77 pagesFazail e Ahlulbait (A.s.) Vol 2FazaileAhlulbait100% (1)

- An Arabic English 00 Came GoogDocument615 pagesAn Arabic English 00 Came GoogRaven Synthx100% (1)

- Sulu Writing PDFDocument193 pagesSulu Writing PDFMitch Delos Santos LuzonNo ratings yet

- The ExpositorDocument301 pagesThe ExpositorAndreina AragonesesNo ratings yet

- Four Advanced Persian Reading UnitsDocument50 pagesFour Advanced Persian Reading UnitsJavier HernándezNo ratings yet

- Why Should We Learn ArabicDocument12 pagesWhy Should We Learn ArabicMohammed EliyasNo ratings yet

- Index of Tangut Characters With Corresponding Tibetan Phonetic GlossesDocument15 pagesIndex of Tangut Characters With Corresponding Tibetan Phonetic GlossesJerry YouNo ratings yet

- Yoyo Chinese Pinyin 2019Document3 pagesYoyo Chinese Pinyin 2019joe wongNo ratings yet

- The University of Chicago PressDocument7 pagesThe University of Chicago PressОктай СтефановNo ratings yet

- TheLifeOfTheProphetMuhammad EnglishTranslationOfIbnKathirsAlSiraAlNabawiyyaVolume3 PDFDocument543 pagesTheLifeOfTheProphetMuhammad EnglishTranslationOfIbnKathirsAlSiraAlNabawiyyaVolume3 PDFkishorebooksscribdNo ratings yet

- TheLifeOfTheProphetMuhammad-EnglishTranslationOfIbnKathirsAlSiraAlNabawiyyaVolume3 (1-100)Document100 pagesTheLifeOfTheProphetMuhammad-EnglishTranslationOfIbnKathirsAlSiraAlNabawiyyaVolume3 (1-100)NASSRONo ratings yet

- Hal Kin 1951Document3 pagesHal Kin 1951Anonymous MGG7vMINo ratings yet

- Ismail R Al FaruqiDocument30 pagesIsmail R Al Faruqisiti aisyahNo ratings yet

- Writing and Cultural Influence Studies in Rhetorical History Orientalist Discourse and Post Colonial Criticism Comparative Cultures and Literature PDFDocument157 pagesWriting and Cultural Influence Studies in Rhetorical History Orientalist Discourse and Post Colonial Criticism Comparative Cultures and Literature PDFnaciye tasdelen100% (1)

- Egyptian Manual of Karaite FaithDocument12 pagesEgyptian Manual of Karaite FaithTommy García100% (1)

- Varisco - Metaphors and Sacred History The Genealogy of Muhammad and The Arab TribeDocument19 pagesVarisco - Metaphors and Sacred History The Genealogy of Muhammad and The Arab TribeRaas4555No ratings yet

- Havelock Eric A The Muse Learns To Write Reflections On Orality and Literacy From Antiquity To The Present PDFDocument156 pagesHavelock Eric A The Muse Learns To Write Reflections On Orality and Literacy From Antiquity To The Present PDFGiselle González Camacho100% (2)

- About Taha HusseinddddddddddddddddddddddddddddDocument20 pagesAbout Taha HusseinddddddddddddddddddddddddddddbascutaNo ratings yet

- The Johns Hopkins University Press The American Journal of PhilologyDocument3 pagesThe Johns Hopkins University Press The American Journal of PhilologyahmadarinalhaqNo ratings yet

- KK-Adi Setia - The Genesis of Greek Intellectuality in Islamic and Western Historiographes of ScienceDocument22 pagesKK-Adi Setia - The Genesis of Greek Intellectuality in Islamic and Western Historiographes of ScienceNoor Aisyah Binti SajuniNo ratings yet

- Barbarians in Arab EyesDocument17 pagesBarbarians in Arab EyesMaria MarinovaNo ratings yet

- Ilm Al Wad A Philosophical AccountDocument19 pagesIlm Al Wad A Philosophical AccountRezart Beka100% (1)

- 2 PDFDocument25 pages2 PDFJawad QureshiNo ratings yet

- Arabicus FelixDocument4 pagesArabicus FelixThinker's NotePadNo ratings yet

- أبو العلاء المعري اللزوميات- مختاراتDocument401 pagesأبو العلاء المعري اللزوميات- مختاراتRoni Bou SabaNo ratings yet

- FSI Levantine Arabic Course - Live Lingua - PDF RoomDocument105 pagesFSI Levantine Arabic Course - Live Lingua - PDF RoomRoni Bou SabaNo ratings yet

- محمود درويش- ذاكرة للنسيانDocument235 pagesمحمود درويش- ذاكرة للنسيانRoni Bou SabaNo ratings yet

- Kymati ThalasisDocument26 pagesKymati ThalasisRoni Bou SabaNo ratings yet

- A Transformational Grammar of Modern Literary Arabic - PDF RoomDocument223 pagesA Transformational Grammar of Modern Literary Arabic - PDF RoomRoni Bou SabaNo ratings yet

- Folk Stories and Personal Narratives in Palestinian Spoken Arabic - A Cultural and Linguistic Study - PDF RoomDocument269 pagesFolk Stories and Personal Narratives in Palestinian Spoken Arabic - A Cultural and Linguistic Study - PDF RoomRoni Bou SabaNo ratings yet

- كليلة ودمنة 1905Document363 pagesكليلة ودمنة 1905Roni Bou SabaNo ratings yet

- Interpretation ReceptionDocument29 pagesInterpretation ReceptionRoni Bou SabaNo ratings yet

- Interpretation ReceptionDocument29 pagesInterpretation ReceptionRoni Bou SabaNo ratings yet

- Bint El ShalabiyaDocument1 pageBint El ShalabiyaRoni Bou SabaNo ratings yet

- Arabic Grammar - ExercisesDocument167 pagesArabic Grammar - ExercisesRaza Bin MuhammadNo ratings yet

- Ruth B Edwards Kadmos The Phoenician A Study in Greek Legends and The Mycenaean AgeDocument280 pagesRuth B Edwards Kadmos The Phoenician A Study in Greek Legends and The Mycenaean AgeRoni Bou Saba100% (7)

- 000644a WWW - AlDocument1,060 pages000644a WWW - AlRoni Bou SabaNo ratings yet

- الجماهر في معرفة الجواهر للبيرونيDocument160 pagesالجماهر في معرفة الجواهر للبيرونيRoni Bou SabaNo ratings yet

- TDS Introduction Language Verse HomerDocument110 pagesTDS Introduction Language Verse HomerRoni Bou SabaNo ratings yet

- Quranic Gems - Juz 25Document2 pagesQuranic Gems - Juz 25Dian HandayaniNo ratings yet

- Admission Result, 1st TimeDocument32 pagesAdmission Result, 1st TimeAli HasanNo ratings yet

- NDU MPhil GAT G Results Spring 2023Document3 pagesNDU MPhil GAT G Results Spring 2023Muhammad Abdul BasitNo ratings yet

- Al Wala Wal BaraDocument138 pagesAl Wala Wal BaraAgustang PuunanggaNo ratings yet

- Hasil Efo-Jt Potential Basic Test1Document28 pagesHasil Efo-Jt Potential Basic Test1u2urhfNo ratings yet

- LITERATUREDocument47 pagesLITERATUREansif anwerNo ratings yet

- 11 Conclusion PDFDocument4 pages11 Conclusion PDFSunny TuvarNo ratings yet

- Why Did Mohammed Get So Many WivesDocument22 pagesWhy Did Mohammed Get So Many WivesSikhSangat BooksNo ratings yet

- Male by CourseDocument19 pagesMale by CourseMohamed AymanNo ratings yet

- Charles GOUNOD: Quinze Melodies Enfantines, Pour Voix Et PianoDocument58 pagesCharles GOUNOD: Quinze Melodies Enfantines, Pour Voix Et PianoEmre ÇetinerNo ratings yet

- Midterm - Shariah IVDocument15 pagesMidterm - Shariah IVchaeny limNo ratings yet

- The Muslim AlmanacDocument1 pageThe Muslim Almanacapi-3710484No ratings yet

- Sir Syed Ahmed KhanDocument2 pagesSir Syed Ahmed Khansanali_81No ratings yet

- 10.1108@ijlma 03 2017 0027Document10 pages10.1108@ijlma 03 2017 0027Bertina AyuNo ratings yet

- Commentary Sura HujuratDocument313 pagesCommentary Sura HujuratMubahilaTV Books & Videos Online100% (1)

- Https Sites - Google.com Site Nusayrilight Home Texts-In-Arabic TMPL /system/app/templates/print/&showPrintDialog 1 PDFDocument4 pagesHttps Sites - Google.com Site Nusayrilight Home Texts-In-Arabic TMPL /system/app/templates/print/&showPrintDialog 1 PDFHazem ShehadehNo ratings yet

- Islamic and Cordillera ArtDocument4 pagesIslamic and Cordillera ArtDiana TanzaNo ratings yet

- Maulidur Rasul Booklet PDFDocument32 pagesMaulidur Rasul Booklet PDFMuhammad IdrusNo ratings yet

- Kelompok Manajemen Farmasi Kelas CDDocument6 pagesKelompok Manajemen Farmasi Kelas CDZaza SaskiaNo ratings yet

- StudentsDocument75 pagesStudentsMilad AkbariNo ratings yet

- Islamic Studies (New-Revised) Course OutlineDocument4 pagesIslamic Studies (New-Revised) Course OutlineMushtak Mufti0% (1)

- Islamic Tourism and Managing TourismDocument11 pagesIslamic Tourism and Managing TourismHenry Farrisch NorteNo ratings yet

- p4 Social Studies Final Test Semester 1Document3 pagesp4 Social Studies Final Test Semester 1wilsonNo ratings yet

- Qur Qur Nic Spell-Ing: Disconnected Letter Series in Islamic Talismans Nic Spell-Ing: Disconnected Letter Series in Islamic TalismansDocument28 pagesQur Qur Nic Spell-Ing: Disconnected Letter Series in Islamic Talismans Nic Spell-Ing: Disconnected Letter Series in Islamic TalismansCarlosNo ratings yet

- Al-Muhannad 'Ala Al-Mufannad TranslationDocument34 pagesAl-Muhannad 'Ala Al-Mufannad TranslationdhumplupukaNo ratings yet

- Hasil To Utbk 4 - SoshumDocument25 pagesHasil To Utbk 4 - Soshumcristinajuniarti hutabaratNo ratings yet

- Preservation of The Sunnah ARTICLEDocument15 pagesPreservation of The Sunnah ARTICLEJ ZarabozoNo ratings yet

- Qureshi Family Information EnglishDocument2 pagesQureshi Family Information EnglishDr. Syed Danish ShahNo ratings yet