Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Wilson - Kant On Intuition

Wilson - Kant On Intuition

Uploaded by

Dan Radu0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

38 views20 pagesIntuition in Kant's works

Original Title

Wilson - Kant on Intuition

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

PDF or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentIntuition in Kant's works

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF or read online from Scribd

Download as pdf

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

38 views20 pagesWilson - Kant On Intuition

Wilson - Kant On Intuition

Uploaded by

Dan RaduIntuition in Kant's works

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF or read online from Scribd

Download as pdf

You are on page 1of 20

247

KANT ON INTUITION

By Kmx Datias Wuson

Kant’s Logic! begins by dividing objective representations into intuitions

and concepts:

Ali cognitions, that is, all [re]presentations consciously referred to an

object, are either intuttions or concepts. Intuition is a singular {re]-

presentation (repraesentatio singularis), the concept is a general (reprae-

sentatio per notas communes) or reflective [re]presentation (repraesenta-

tio discursiva) (op. cit., § 1).

But, as Frege has noted, this definition of ‘intuition’ contains no mention

of a connection with sensibility,? a connection that dominates the treatment

of intuition in the Transcendenta] Aesthetic? What is more, in contrast

with the Logic definition of intuition in terms of singularity, the opening

sentence of the Transcendental Aesthetic reads,

In whatever manner and by whatever means a mode of knowledge

may relate to objects, intuition is that through which it is in immediate

relation to them. . . . (A19=B34).

Later in the Critique, however, ‘intuition’ is defined by both singularity and

immediacy: intuition, Kant says, “relates immediately to the object and is

[singular (einzeln)}” (A320 B377).

Two problems with Kant’s notion of intuition emerge:

(1) How are the singularity and immediacy criteria for defining in-

tuitive representations related?

(2) How is the connection between intuition and sensibility to be

established?

In the Prolegomena‘ and in the Transcendental Expositions in B, Kant

treats the connection of intuition to sensibility as a consequence of a certain

theory of mathematical construction (see sec. V below); however, the relation

between singularity and immediacy as defining criteria of intuition is never,

as far as I know, made explicit by Kant.

In some recent articles Jaakko Hintikka has argued that the immediacy

criterion is just another formulation of the singularity criterion.® Charles

Parsons has countered that the two criteria are different and, moreover, that

Ummanuel Kant: Logic, trans. Robert 8, Hartman and Wolfgang Schwarz, Library

of Liberal Arts (Indianapolis, 1974). Hereinafter, Logic; references to this work will

appear in the text.

The Foundations of Arithmetic, trans. J. L. Austin (New York, 1960), p. 19.

___20f the Critique of Pure Reason, trans. Norman Kemp-Smith (London, 1963). Here-

inafter, Critique; references will appear in the text.

“Prolegomena to Any Future Metaphyeice, ed. Lewis White Bock, Library of Liberal

Arts (Indianapolis, 1960). Hereinafter, Prolegomena; references will appear in the text.

‘Most notably in “On Kant’a Notion of Intuition (Anschauung)”, in The Firat

ust Reflections on Kant's Critique of Pure Reason, od. T- Penelhum and J. J.

tosh (Belmont, 1969), esp. p. 42. Seo also Hintikie ‘a reply to Parsons, “Kantian

Intuitions”s Inquiry, 15 (1873), pp. 341-5, cop. pe B42

248 KIRK DALLAS WILSON

the singularity criterion is broader than that of immediacy in characterizing

representations as intuitive.* I shall argue that Kant’s two criteria aro

intensionally different but eztensionaily identical. In other words, although

each criterion identifies a different aspect of intuitive representations, any

representation that satisfies the one also satisfies the other. Against Hin-

tikka, therefore, I shall argue that immediacy cannot be reduced to singular-

ity, and against Parsons I shall argue that neither criterion is broader than

the other. The root difficulty in both Hintikka's and Parsons’ positions lies

in their interpretation of Kantian intuitions as corresponding to singular

terms of the Predicate Calculus. Against this interpretation I shall defend

a reconstruction of Kant’s singularity criterion in terms of mereological

primitives and of the immediacy criterion in terms of a suitable notion of

isomorphism.

I

Though much is said of the ambiguity between act and content im Kant's

notion of representation, Kant rarely used ‘representation’ to mean the act

of representing. While such acts are necessarily tied to our representations,

representations themselves are objects of consciousness {mental entities).

Our representations are the content of our acts of apprehending; they are

the what of what is apprehended. Accordingly, in this paper I shall use

‘representation’ in the content-sense.

Let us begin by noting a prima facie case for the intensional difference

but extensional identity of the singularity and immediacy criteria. Though

prima facie, this case prohibits one kind of reconstruction of Kant’s notion

of intuition,

Concepts are said to be general representations because they represent

many objects by marks or characteristics that these objects have in common.

By implication, then, intuitions do not represent their objects by marks or

characteristics. But because Kant holds the transcendental thesis that

intuitions are connected with sensibility, which therefore places the study

of singular representations outside the scope of general logic and inside that

of aesthetic (A52=B76), Kant does not explain in the logic how intuitions

represent in virtue of their singularity. In formal logic Kant mentions the

singularity of intuitive representations as a contrast with the generality of

conceptual representations. Nevertheless, we shall find that it is possible

through the contrast with the generality of concepts to reconstruct the

singularity of representations with logical mechanisms (sec. III below). Thus

we obtain one of Kant’s criteria for distinguishing kinds of representations

—singularity versus generality—as a distinction regarding the logical strwe-

ture of a representation.

On the other hand, while singularity is mentioned at least seven times

as the defining feature of intuitions in the logic lectures during the critical

“Kant’s Philosophy of Arithmetic”, in Philosophy, Soience, and Method, ed. Sidney

Morgonbosser, ef al. (New York, 1969), p. 670,

KANT ON INTUITION 249

period, the immediacy criterion is alluded to only twice.” This imbalance is

quite understandable, since logic, according to Kant, abstracts from the

mode in which a representation relates to an object (A55<=B79). Immediacy

versus mediacy, as modes of representation, constitute a critica] distinction

between ways in which a representation is said to represent its object. The

critical character of this distinction emerges from the important letter to

Marcus Herz of February 1772 in which Kant first raised the critical question.

Although he later formulated the critical question in terms of the syn-

thetic a priori character of judgments, Kant originally questioned “the

grounds of the relation of that in us which we call ‘representation’ to the

object”.* Kant immediately added that “passive or sensuous representations

ie. intuitions] have an understandable relationship to objects”, since they

are the immediate effects on the mind of the objects themselves, Even in

the mature critical philosophy there is some evidence that Kant tended to

identify the object represented by intuition with the cause of the intuition;*

it is easy to sce in this argument the justification of intuition’s immediate,

and critically unproblematic, relation to its object. The critical difficulty,

on the other hand, concerns “intellectual representations”, for these depend

upon the “inner activity of the mind” and, therefore, cannot stand in im-

mediate relation to their objects.1° This early formulation of the critical

problem is reflected in the Critique by the doctrine that concepts are predi-

cates of possible judgments (A69=B94) and, hence, require a mediating

representation in order to relate to objects. According to this doctrine, all

concepts contain other representations under themselves as the mediating

elements in their relation to objects (A69=B93-94). Thus, of the two criteria

In Kants Vorlesungen: Forlesungen tiber Logik, Kants Gesammelte Schriften, hrs

von der Deutschen Akademie der Wisaonschaften zu Berlin, vol. 24 (Berlin, 1966),

References to intuition as singular representation oecur in Logzk Philippi, p. 451: Logik

Potitz, pp. 565, 568; Logik Buaolt, p. 653; Logik Dohna-Wundlacken, p. 754; and Wiener

Logik, pp. 904, 905. Thtuition as immediate representation is assumed but not directly

stated in Logik Politz, p. 569, during a discussion of the impossibility of infimae species

(or lowest species). Immediacy is explicitly associated with intuition in Logik Dokna-

Wundlacken, p. 754; but by 1792 one might expect that aspects of the critical philosophy

would be creeping into the logic lectures, Further references to these notes will appear

in the text; the translations are mine.

"In Kant: Philosophical Correspondence 1759-99, trans. and ed. Arnulf Zweig (Chicago,

1967), p. 71.

*See Norman Kemp Smith, 4 Commentary to Kant's Critique of Pure Reason (Now

York, 1962), p. 80.

1°Kant; Philosophical Correspondence 1759-99, p. 72.

MBy repudiating the traditional doctrine of infimae species (see Logic, § 11, Note;

and Logit Politz, p. 569), Kant proves that it is part of the logical theory of concepts

that aii concepta contain other concopts under themselves, for this repudiation guaran-

toes at least in principle that any concept can be a genus. What is critical about this

doctrine is that concepts are used as predicates in judgments when they are used to

provide a conceptualization of objects. However, Manley Thompson is mistaken when

ho argues that the repudiation of the doctrine of infimae species entails that Kant would

havo used the first-order scheme ‘Fz° as the form of predication rather than the form

of classical logic ‘S is P* (“Si lar Terms and Intuition: in Kant's Epistemology”,

The Review of Metaphysics, XXVI (1972), pp. 326-326). The repudiation of the doctrine

Of tnfimae species is only @ necessary condition for Kant’s critical use of concepts as

mediate representations in the eritical philosophy.

You might also like

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5825)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1093)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (852)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (590)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (903)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (541)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (349)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (823)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (122)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (403)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- 6th Central Pay Commission Salary CalculatorDocument15 pages6th Central Pay Commission Salary Calculatorrakhonde100% (436)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- 05 - Build Crate ChairDocument4 pages05 - Build Crate ChairMartin GyurikaNo ratings yet

- Ramniranjan Jhunjhunwala College of Arts, Science and Commerce (Autonomous)Document1 pageRamniranjan Jhunjhunwala College of Arts, Science and Commerce (Autonomous)Angelina JoyNo ratings yet

- Selling Blue ElephantsDocument45 pagesSelling Blue ElephantsDan RaduNo ratings yet

- Manual 1000 HP Quintuplex MSI QI 1000 PumpDocument106 pagesManual 1000 HP Quintuplex MSI QI 1000 Pumposwaldo58No ratings yet

- Vahid - A Priori KnowledgeDocument16 pagesVahid - A Priori KnowledgeDan RaduNo ratings yet

- City in The Sky - The Best of OpethDocument2 pagesCity in The Sky - The Best of OpethDan RaduNo ratings yet

- The Sublime and The OtherDocument20 pagesThe Sublime and The OtherDan RaduNo ratings yet

- Setlist Omnium Gatherum OttawaDocument1 pageSetlist Omnium Gatherum OttawaDan RaduNo ratings yet

- Setlist Omnium Gatherum LondonDocument1 pageSetlist Omnium Gatherum LondonDan RaduNo ratings yet

- Setlist Omnium Gatherum TorontoDocument1 pageSetlist Omnium Gatherum TorontoDan RaduNo ratings yet

- Setlist Moonspell, Krakow, Poland, Kwadrat, October, 28th, 2013Document2 pagesSetlist Moonspell, Krakow, Poland, Kwadrat, October, 28th, 2013Dan RaduNo ratings yet

- Setlist Moonspell, Rostov, Russia Arena Rostov, November 6th, 2013Document2 pagesSetlist Moonspell, Rostov, Russia Arena Rostov, November 6th, 2013Dan RaduNo ratings yet

- Setlist Moonspell ST Petersburg 02.11.2013Document2 pagesSetlist Moonspell ST Petersburg 02.11.2013Dan RaduNo ratings yet

- Metal / Rock Setlist For TMN Ao Vivo: 3.satyricon - Black Crow On A TombstoneDocument2 pagesMetal / Rock Setlist For TMN Ao Vivo: 3.satyricon - Black Crow On A TombstoneDan RaduNo ratings yet

- at Tragic Heights 2. Grandstand 3. Everything Invaded 4. Love Crimes 6. Opium 7. White SkiesDocument1 pageat Tragic Heights 2. Grandstand 3. Everything Invaded 4. Love Crimes 6. Opium 7. White SkiesDan RaduNo ratings yet

- Lance Hickey - Kant's Transcendental ObjectDocument37 pagesLance Hickey - Kant's Transcendental ObjectDan RaduNo ratings yet

- Husserl Edmund - Psychological and Transcendental PhenomenologyDocument441 pagesHusserl Edmund - Psychological and Transcendental PhenomenologyTom Rue100% (3)

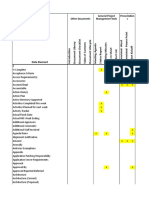

- Project Management Tools Document MatrixDocument35 pagesProject Management Tools Document MatrixtabaquiNo ratings yet

- Complexe Scolaire Et Universitaire Cle de La Reussite 2022-2023 Composition 2e TrimestreDocument6 pagesComplexe Scolaire Et Universitaire Cle de La Reussite 2022-2023 Composition 2e TrimestreBruno HOLONOUNo ratings yet

- Earthing Design Calculation 380/110/13.8kV SubstationDocument19 pagesEarthing Design Calculation 380/110/13.8kV Substationhpathirathne_1575733No ratings yet

- Commonwealth Edison: Project DescriptionDocument1 pageCommonwealth Edison: Project DescriptionAtefeh SajadiNo ratings yet

- Ats22 User Manual en Bbv51330 02Document85 pagesAts22 User Manual en Bbv51330 02Catalin PelinNo ratings yet

- Paintng Works U#3 Boiler Turbine Area: DuplicateDocument1 pagePaintng Works U#3 Boiler Turbine Area: DuplicatevenkateshbitraNo ratings yet

- What Is A Clone?Document6 pagesWhat Is A Clone?Mohamed Tayeb SELTNo ratings yet

- Worksheet 1Document2 pagesWorksheet 1beshahashenafe20No ratings yet

- Activity Heal The Environmentpermentilla-Michael-Ray-E.Document1 pageActivity Heal The Environmentpermentilla-Michael-Ray-E.Michael Ray PermentillaNo ratings yet

- Canal SystemsDocument69 pagesCanal SystemsAnter TsatseNo ratings yet

- Demand Forecasting PDFDocument18 pagesDemand Forecasting PDFChhaviGuptaNo ratings yet

- Catalogo de Partes GCADocument20 pagesCatalogo de Partes GCAacere18No ratings yet

- University of Dundee: Hanson, Christine JoanDocument5 pagesUniversity of Dundee: Hanson, Christine JoanTotoNo ratings yet

- Ives - Stilwell Experiment Fundamentally FlawedDocument22 pagesIves - Stilwell Experiment Fundamentally FlawedAymeric FerecNo ratings yet

- Self Balancing RobotDocument48 pagesSelf Balancing RobotHiếu TrầnNo ratings yet

- Normalisation in MS AccessDocument11 pagesNormalisation in MS AccessFrances VorsterNo ratings yet

- AutoBiography of A RiverDocument4 pagesAutoBiography of A Riversukhamoy2571% (21)

- Lexicology: - Structure of The LexiconDocument16 pagesLexicology: - Structure of The LexiconAdina MirunaNo ratings yet

- Intimate Partner Violence Among Pregnant Women in Kenya: Forms, Perpetrators and AssociationsDocument25 pagesIntimate Partner Violence Among Pregnant Women in Kenya: Forms, Perpetrators and AssociationsNove Claire Labawan EnteNo ratings yet

- Design of Basic ComputerDocument29 pagesDesign of Basic ComputerM DEEPANANo ratings yet

- Tapo C100 (EU&US) 1.0 DatasheetDocument4 pagesTapo C100 (EU&US) 1.0 DatasheetkelvinNo ratings yet

- Astrolabe Free Chart From HTTP - AlabeDocument2 pagesAstrolabe Free Chart From HTTP - AlabeArijit AcharyaNo ratings yet

- Temas de Ensayo de MacroeconomíaDocument6 pagesTemas de Ensayo de Macroeconomíag69zer9d100% (1)

- Mode of Failure FoundationDocument11 pagesMode of Failure FoundationFirash ImranNo ratings yet

- FGD Vs CompetitorCustomer - Final - LF14000NN & P559000Document9 pagesFGD Vs CompetitorCustomer - Final - LF14000NN & P559000munhNo ratings yet

- As 1330-2004 Metallic Materials - Drop Weight Tear Test For Ferritic SteelsDocument7 pagesAs 1330-2004 Metallic Materials - Drop Weight Tear Test For Ferritic SteelsSAI Global - APACNo ratings yet

- Basic Hydrocyclone OperationDocument23 pagesBasic Hydrocyclone Operationgeo rayfandyNo ratings yet