Professional Documents

Culture Documents

NEJMoa 074306

NEJMoa 074306

Uploaded by

monamustafaOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

NEJMoa 074306

NEJMoa 074306

Uploaded by

monamustafaCopyright:

Available Formats

The n e w e ng l a n d j o u r na l of m e dic i n e

original article

Mutations and Treatment Outcome in

Cytogenetically Normal Acute Myeloid Leukemia

Richard F. Schlenk, M.D., Konstanze Döhner, M.D., Jürgen Krauter, M.D.,

Stefan Fröhling, M.D., Andrea Corbacioglu, Ph.D., Lars Bullinger, M.D.,

Marianne Habdank, Daniela Späth, Michael Morgan, Ph.D., Axel Benner, M.Sc.,

Brigitte Schlegelberger, M.D., Gerhard Heil, M.D., Arnold Ganser, M.D.,

and Hartmut Döhner, M.D., for the German–Austrian

Acute Myeloid Leukemia Study Group*

A bs t r ac t

Background

Mutations occur in several genes in cytogenetically normal acute myeloid leukemia From the University Hospital of Ulm, Ulm

(AML) cells: the nucleophosmin gene (NPM1), the fms-related tyrosine kinase 3 gene (R.F.S., K.D., S.F., A.C., L.B., M.H., D.S.,

H.D.); Hannover Medical School, Han-

(FLT3), the CCAAT/enhancer binding protein α gene (CEPBA), the myeloid–lymphoid nover (J.K., M.M., B.S., G.H., A.G.); and

or mixed-lineage leukemia gene (MLL), and the neuroblastoma RAS viral oncogene the German Cancer Research Center,

homolog (NRAS). We evaluated the associations of these mutations with clinical Heidelberg (A.B.) — all in Germany. Ad-

dress reprint requests to Dr. H. Döhner

outcomes in patients. at the Department of Internal Medicine

Methods III, University Hospital of Ulm, Robert-

Koch-Straße 8, 89081 Ulm, Germany, or

We compared the mutational status of the NPM1, FLT3, CEBPA, MLL, and NRAS genes at hartmut.doehner@uniklinik-ulm.de.

in leukemia cells with the clinical outcome in 872 adults younger than 60 years of age

Drs. Schlenk and K. Döhner contributed

with cytogenetically normal AML. Patients had been entered into one of four trials equally to the article, as did Drs. Ganser

of therapy for AML. In each study, patients with an HLA-matched related donor and H. Döhner.

were assigned to undergo stem-cell transplantation.

*Members of the German–Austrian Acute

Results Myeloid Leukemia Study Group are list

A total of 53% of patients had NPM1 mutations, 31% had FLT3 internal tandem dupli- ed in the Appendix.

cations (ITDs), 11% had FLT3 tyrosine kinase–domain mutations, 13% had CEBPA N Engl J Med 2008;358:1909-18.

mutations, 7% had MLL partial tandem duplications (PTDs), and 13% had NRAS mu- Copyright © 2008 Massachusetts Medical Society.

tations. The overall complete-remission rate was 77%. The genotype of mutant

NPM1 without FLT3-ITD, the mutant CEBPA genotype, and younger age were each

significantly associated with complete remission. Of the 663 patients who received

postremission therapy, 150 underwent hematopoietic stem-cell transplantation from

an HLA-matched related donor. Significant associations were found between the risk

of relapse or the risk of death during complete remission and the leukemia genotype

of mutant NPM1 without FLT3-ITD (hazard ratio, 0.44; 95% confidence interval [CI],

0.32 to 0.61), the mutant CEBPA genotype (hazard ratio, 0.48; 95% CI, 0.30 to 0.75),

and the MLL-PTD genotype (hazard ratio, 1.56; 95% CI, 1.00 to 2.43), as well as

receipt of a transplant from an HLA-matched related donor (hazard ratio, 0.60; 95%

CI, 0.44 to 0.82). The benefit of the transplant was limited to the subgroup of pa-

tients with the prognostically adverse genotype FLT3-ITD or the genotype consist-

ing of wild-type NPM1 and CEBPA without FLT3-ITD.

Conclusions

Genotypes defined by the mutational status of NPM1, FLT3, CEBPA, and MLL are asso

ciated with the outcome of treatment for patients with cytogenetically normal AML.

n engl j med 358;18 www.nejm.org may 1, 2008 1909

The New England Journal of Medicine

Downloaded from www.nejm.org on October 8, 2010. For personal use only. No other uses without permission.

Copyright © 2008 Massachusetts Medical Society. All rights reserved.

The n e w e ng l a n d j o u r na l of m e dic i n e

A

cute myeloid leukemia (aml) is a ge- going clinical trials involving young adults have

netically heterogeneous disease in which adopted strategies for balancing treatment-related

somatic mutations that disturb cellular toxic effects with the risk of relapse. These strat-

growth, proliferation, and differentiation accumu egies are particularly relevant to allogeneic stem-

late in hematopoietic progenitor cells. The karyo- cell transplantation, in that it is usually offered to

type at the time of diagnosis provides the most patients with high-risk cytogenetic abnormalities

important prognostic information in adults with and not to low-risk patients.

AML,1-3 but 40 to 50% of patients do not have In this study, we aimed to assess the frequen-

clonal chromosomal aberrations.1-3 All such cases cies and interactions of mutations in NPM1, FLT3,

of cytogenetically normal AML are currently cate- CEBPA, MLL, and NRAS. We also planned to evalu-

gorized in the intermediate-risk group, yet this ate the association of the mutations with treat-

group is quite heterogeneous.4,5 ment outcomes and to analyze the role of the

In recent years, acquired gene mutations, as mutations in guiding postremission therapy in

well as deregulation of gene expression, have been patients with cytogenetically normal AML.

identified.6-8 Somatic mutations in AML include

partial tandem duplications (PTDs) of the my- Me thods

eloid–lymphoid or mixed-lineage leukemia gene

(MLL),9 internal tandem duplications (ITDs)10 or SELECTION OF PATIENTS

mutations of the tyrosine kinase domain (TKD)11 Between July 1993 and November 2004, patients

of the fms-related tyrosine kinase 3 gene (FLT3), were enrolled in one of four multicenter prospec-

and mutations in the nucleophosmin gene tive treatment trials of the German–Austrian Acute

(NPM1),12 the CCAAT/enhancer binding protein Myeloid Leukemia Study Group (see Table 1 in the

α gene (CEBPA),13 and the neuroblastoma RAS Supplementary Appendix, available with the full

viral oncogene homolog gene (NRAS).14 These al- text of this article at www.nejm.org). The eligi-

terations appear to fall into two broadly defined bility criteria of the four trials were similar. The

complementation groups.15 One group (class I) inclusion criterion for the individual-patient–data

comprises mutations that activate signal-trans- analysis described here was the presence of a nor-

duction pathways and thereby increase the prolif- mal karyotype on chromosome-banding analysis.

eration or survival, or both, of hematopoietic pro

genitor cells. Mutations that activate the receptor THERAPY

tyrosine kinase FLT316 or RAS17 family members All four trials used double-induction therapy with

are considered to be class I mutations. The other idarubicin, cytarabine, and etoposide; a first cycle

complementation group (class II) comprises mu- of consolidation therapy based on high-dose cyta-

tations that affect transcription factors or compo- rabine; and a second cycle of consolidation ther-

nents of the transcriptional coactivation complex apy during which patients with an HLA-matched

and cause impaired differentiation. On the basis related donor were assigned to undergo stem-cell

of their known physiological functions, mutations transplantation and those without a suitable do-

in CEBPA,18 MLL,19 and possibly also NPM120 fall nor received high-dose cytarabine-based chemo-

into this group. therapy or were randomly assigned either to re-

Mutations in these genes have prognostic rele ceive such chemotherapy or to undergo autologous

vance. FLT3-ITD21-25 and MLL-PTD26,27 have been stem-cell transplantation (Fig. 1 and Fig. 2 in the

associated with short relapse-free and overall Supplementary Appendix). For both autologous

survival, whereas a more favorable outcome is and allogeneic transplantation, a conditioning

associated with cytogenetically normal cases of regimen of hyperfractionated total-body irradia-

AML with mutations in CEBPA28-30 or NPM1 (with- tion (12.0 to 14.4 Gy) or oral busulfan (16 mg per

out concomitant FLT3-ITD).31-34 kilogram of body weight) followed by intrave-

Postremission therapy with repeat cycles of nous cyclophosphamide (120 to 200 mg per kilo-

high-dose cytarabine is an effective treatment gram of body weight) was recommended.

for cytogenetically normal AML.4,5 Hematopoi-

etic stem-cell transplantation involving an HLA- CYTOGENETIC AND MOLECULAR GENETIC STUDIES

matched related donor can reduce the risk of Cytogenetic and molecular genetic studies were

relapse, but this benefit is mitigated by a treat- performed in two central reference laboratories

ment-related mortality of 15 to 25%.4,5 Most on- of the German–Austrian Acute Myeloid Leukemia

1910 n engl j med 358;18 www.nejm.org may 1, 2008

The New England Journal of Medicine

Downloaded from www.nejm.org on October 8, 2010. For personal use only. No other uses without permission.

Copyright © 2008 Massachusetts Medical Society. All rights reserved.

Gene Mutations in Cytogenetically Normal Acute Myeloid Leukemia

Study Group, one at the University of Ulm and and data for all patients with this variant were

the other at Hannover Medical School. Blood or used in the current analysis (Table 1 in the Supple-

bone marrow specimens from each patient were mentary Appendix). Table 1 lists the baseline char

screened for the recurring gene fusions PML– acteristics of the 872 patients. The availability of

RARA, CBFB–MYH11, and RUNX1–RUNX1T1, by an HLA-matched donor was recorded for 846 of

means of the fluorescence in situ hybridization the 872 patients.

assay or polymerase-chain-reaction assay. Diag-

nostic samples were also analyzed for mutations MOLECULAR MARKERS

in the FLT3 gene (i.e., the ITD and TKD mutations Screening for molecular markers was performed

at codons D835 and I836) and in the CEBPA, MLL, in all available samples of blood or bone marrow,

NPM1, and NRAS genes (Table 2 in the Supple- or both, that were taken at the time of diagnosis:

mentary Appendix). NPM1 was screened in 570 patients, FLT3-ITD in

531 patients, FLT3-TKD in 617 patients, CEBPA in

STATISTICAL ANALYSIS 509 patients, MLL-PTD in 640 patients, and NRAS

The primary end point was relapse-free survival; in 641 patients. The mutational status of all six

secondary end points were complete remission af- markers could be determined in 438 of the 872

ter induction therapy and overall survival. To eval- patients with cytogenetically normal AML (50%),

uate relapse-free survival and overall survival, we and 693 of the 872 patients (79%) had at least one

used relapse or death during complete remission marker analyzed.

and death, respectively. These end points were NPM1 mutations were found in 301 of 570

concordant with those in the primary treatment patients (53%), FLT3-ITD in 164 of 531 patients

trials, and all were based on recommended crite- (31%), FLT3-TKD in 68 of 617 patients (11%),

ria.35 A conditional logistic-regression model in- CEBPA in 67 of 509 patients (13%), MLL-PTD in 47

corporating stratification according to treatment of 640 patients (7%), and NRAS in 82 of 641 pa-

trial was used to analyze associations between tients (13%). Frequencies and distributions of the

baseline characteristics and the achievement of mutations differed slightly between the subgroup

complete remission. A Cox model with stratifica- of the 438 patients with complete mutation data

tion to account for the particular treatment trial (Fig. 1). At least one mutation was identified in

was used to identify prognostic variables. In addi- 369 of the 438 patients (84%). In 312 of the 438

tion to the molecular markers, the presence or ab- patients, there were mutations in hypothetical

sence of hepatosplenomegaly, age, white-cell class II genes (NPM1, CEBPA, and MLL), with only

count, and type of AML were added as explana- minimal overlap: only 17 patients (5%) had more

tory variables in all regression analyses. On the than one class II mutation. Class I mutations

basis of data from previous studies, the marker of (FLT3-ITD, FLT3-TKD, and NRAS) were identified

mutant NPM1 without FLT3-ITD was compared in 241 of the 438 patients, again with a minimal

with all other combinations of these two mark- number of patients (12 patients, 5%) having more

ers.31-34 We estimated missing data for covariates than one class I mutation. FLT3-ITD (P<0.001)

for patients with at least one molecular marker and FLT3-TKD mutations (P = 0.03), but not NRAS

analyzed by using 50 multiple imputations in mutations (P = 0.46), were significantly associated

chained equations incorporating predictive mean with NPM1 mutations. As compared with these

matching.36 All statistical analyses were performed associations, FLT3-ITD (P = 0.03) was less frequent

with the use of the R package (version 2.0-12) of ly associated, and FLT3-TKD (P = 0.40) and NRAS

the R statistical software platform (version 2.4.1).37 (P = 0.34) mutations were not significantly associ-

P values of less than 0.05 were considered to in- ated, with CEBPA. MLL-PTD was not significantly

dicate statistical significance. associated with class I mutations.

R e sult s INDUCTION THERAPY

In all trials, response-adapted, double-induction

ACCRUAL AND CLINICAL CHARACTERISTICS therapy was administered (Fig. 1 in the Supple-

A total of 1919 patients who were 16 to 60 years mentary Appendix). Patients in whom there was

of age and had newly diagnosed AML were en- complete or partial remission after the first course

rolled in the four treatment trials. Cytogenetically of induction therapy received a second course,

normal AML was identified in 872 patients (45%), whereas patients with refractory disease received

n engl j med 358;18 www.nejm.org may 1, 2008 1911

The New England Journal of Medicine

Downloaded from www.nejm.org on October 8, 2010. For personal use only. No other uses without permission.

Copyright © 2008 Massachusetts Medical Society. All rights reserved.

The n e w e ng l a n d j o u r na l of m e dic i n e

Table 1. Baseline Characteristics of the 872 Patients with Cytogenetically Normal Acute Myeloid Leukemia (AML).*

All Patients Patients with ≥1 Molecular

Characteristic (N = 872) Marker Analyzed (N = 693)

Sex — no. (%)

Male 408 (47) 330 (48)

Female 464 (53) 363 (52)

Age — yr

Median 48 48

Range 16–60 16–60

FAB type — no. (%)

M0 39 (5) 31 (5)

M1 141 (18) 108 (18)

M2 206 (27) 166 (27)

M4 236 (31) 185 (31)

M5 108 (14) 92 (15)

M6 29 (4) 20 (3)

M7 4 (<1) 4 (1)

Missing data 109 (13) 87 (13)

Lymphadenopathy — no./total no. (%) 177/829 (21) 157/658 (24)

Hepatosplenomegaly — no./total no. (%) 307/831 (37) 263/661 (40)

Gingival hyperplasia — no./total no. (%) 61/829 (7) 52/673 (8)

CNS involvement — no./total no. (%) 7/816 (1) 6/667 (1)

Type of AML — no. (%)

Primary AML 762 (87) 607 (88)

s-AML 96 (11) 73 (11)

t-AML 13 (1) 12 (2)

Missing data 1 (<1) 1 (<1)

Family donor available — no./total no. (%)† 218/846 (26) 178/670 (27)

White-cell count

Median — ×10−9/liter 16.9 20.1

Range — ×10−9/liter 0.2–372.0 0.2–372.0

Missing data — no. (%) 21 (2) 16 (2)

Platelet count

Median — ×10−9/liter 60 60

Range — ×10−9/liter 4–746 4–746

Missing data — no. (%) 29 (3) 22 (3)

Hemoglobin

Median — g/liter 91 91

Range — g/liter 25–176 30–176

Missing data — no. (%) 29 (3) 21 (3)

Bone marrow blasts

Median — % 80 80

Range — % 0–100 0–100

Missing data — no. (%) 77 (9) 64 (9)

Peripheral-blood blasts

Median — % 41 42

Range — % 0–100 0–100

Missing data — no. (%) 68 (8) 47 (7)

* CNS denotes central nervous system, FAB French–American–British, s-AML AML that developed after a myelodysplas-

tic syndrome, and t-AML AML that developed after chemotherapy or radiation therapy.

† Family donor data were not available for 26 patients because of death during induction therapy or the first cycle of con-

solidation therapy.

1912 n engl j med 358;18 www.nejm.org may 1, 2008

The New England Journal of Medicine

Downloaded from www.nejm.org on October 8, 2010. For personal use only. No other uses without permission.

Copyright © 2008 Massachusetts Medical Society. All rights reserved.

Gene Mutations in Cytogenetically Normal Acute Myeloid Leukemia

NPM1 54% Hypothetical class II

mutations impairing

differentiation

CEBPA 14% Class I mutations con-

ferring a proliferative

advantage

MLL-PTD 7%

FLT3-ITD 32%

FLT3-TKD 12%

NRAS 14%

Data for Each of the 438 Patients

Figure 1. Frequencies and Distribution of the NPM1, CEBPA, MLL, FLT3, and NRAS Mutations, According to Muta-

tion Class.

Frequencies are given for the 438 patients in whom data on all genes were available. ITD denotes internal tandem

duplication, PTD partial tandem duplication, and TKD mutation of the tyrosine kinase domain.

ICM

AUTHOR: Schlenk (Dohner) RETAKE 1st

FIGURE: 1 of 3 2nd

REG F

3rd

CASE Revised

a salvage regimen. Complete EMailremission was Line spectively)

4-C or according

SIZE to the treatment actually

ARTIST: ts

achieved in 668 of the 872 patients

Enon (77%), 130 H/T received

Combo

H/T

(P = 0.65

22p3and P = 0.88, respectively); nor

patients (15%) had refractory disease, andAUTHOR, 74 pa- PLEASE

wereNOTE:

there significant differences according to the

tients (8%) had early death or death Figurewith hypo-

has been redrawn mutational

and type has beenstatus.

reset. Therefore, the no-donor group

Please check carefully.

plastic bone marrow. was considered an appropriately uniform treat-

Multivariable analysis ofJOB:data

35818from the 693 ment group for 05-01-08

ISSUE: comparison with the donor group.

patients with at least one molecular marker ana-

lyzed revealed that two genotypes were signifi- SURVIVAL ANALYSES

cantly associated with a complete remission: The median follow-up for survival was 51.6 months.

mutant CEBPA (odds ratio, 1.33; 95% confidence Of the 872 patients, 471 (54%) died; the median

interval [CI], 1.01 to 1.74) and mutant NPM1 overall survival was 30.4 months, and the 4-year

without FLT3-ITD (odds ratio, 1.48; 95% CI, 1.21 rate of overall survival was 43% (95% CI, 39 to 47).

to 1.80). The odds ratio for a complete remission Of the 668 patients in whom complete remission

for each 10-year increase in age was 0.91 (95% was achieved, 80 died in complete remission and

CI, 0.84 to 0.99). 294 had a relapse; the median relapse-free survival

was 22.2 months, and the 4-year rate of relapse-

POSTREMISSION THERAPY free survival was 42% (95% CI, 38 to 46). To ad-

A matched donor was available for 182 of the 663 dress a potential source of bias, we compared the

patients (27%) in complete remission (the donor 693 patients who had at least one molecular

group); allogeneic transplantation was actually marker analyzed and the 179 patients without

performed in 150 patients (82%). Of the 481 pa- any marker analyzed. The 693 patients with at least

tients without a matched donor (the no-donor one marker analyzed had significantly higher leu-

group), 147 were assigned to receive chemother- kocyte counts and higher percentages of bone

apy and 334 were randomly assigned either to marrow blasts than the 179 patients without any

receive chemotherapy or to undergo autologous marker analyzed. However, there was no signifi-

stem-cell transplantation. There was no signifi- cant difference between the two subgroups in the

cant difference in relapse-free or overall survival primary end point (relapse-free survival, P = 0.87)

between those receiving chemotherapy and those or the secondary end points (complete remission,

undergoing autologous transplantation, on an P = 0.55; overall survival, P = 0.57).

intention-to-treat basis (P = 0.78 and P = 0.44, re- Of the 693 patients with at least one marker

n engl j med 358;18 www.nejm.org may 1, 2008 1913

The New England Journal of Medicine

Downloaded from www.nejm.org on October 8, 2010. For personal use only. No other uses without permission.

Copyright © 2008 Massachusetts Medical Society. All rights reserved.

The n e w e ng l a n d j o u r na l of m e dic i n e

analyzed, 526 (76%) had a complete remission. ITD and for those with other genotypes. Data for

Five patients died before the start of postremis- the 62 patients with mutant CEBPA were excluded,

sion therapy. Table 2 lists data from the multi- because there were too few patients for a mean-

variable analysis for the primary end point and a ingful statistical analysis.

secondary end point. Figure 2 shows the Kaplan–

Meier curves for relapse-free and overall survival, TREATMENT AND SURVIVAL AFTER RELAPSE

according to genotype. In all, 54 patients in the donor group and 240 pa-

tients in the no-donor group had a relapse, and a

ALLOGENEIC TRANSPLANTATION second complete remission was achieved in 25 pa-

A univariable analysis of data for patients with a tients (46%) and 102 patients (42%), respectively.

complete remission, comparing the donor group (Details of treatment after relapse are given in

with the no-donor group, revealed a significantly Table 3 in the Supplementary Appendix.) Among

longer relapse-free survival (P = 0.009) in the do- the patients with a relapse, the median survival

nor group, but this difference did not translate at 3 years was 6.1 months in the no-donor group

into a significant difference in overall survival and 7.3 months in the donor group, and the 3-year

(P = 0.54). The treatment-related mortality rate survival rate was 12% (95% CI, 4 to 23) in the

among the patients who underwent allogeneic no-donor group and 24% (95% CI, 18 to 30) in the

transplantation was 21%. To explore the role of donor group (P = 0.44 by the log-rank test for sur-

allogeneic transplantation according to genotype, vival). The 3-year survival rate among the 94 pa-

we performed an analysis based on indirect as- tients who received a transplant from an HLA-

sessment with separated tests.38 Cox regression matched unrelated donor after relapse was 49%

analyses of relapse-free survival were performed (95% CI, 38 to 60).

with the use of data from two subgroups: 130 pa-

tients with mutant NPM1 without FLT3-ITD, a prog Dis cus sion

nostically favorable subgroup, and 172 patients

with other genotypes. Among the patients with Our analysis, based on four prospective clinical

mutant NPM1 without FLT3-ITD, there was no ben- trials by the German–Austrian Acute Myeloid Leu-

efit for the donor group as compared with the kemia Study Group, was performed to evaluate the

no-donor group (hazard ratio for the risk of re- prognostic and predictive value of NPM1, FLT3,

lapse or the risk of death during complete remis- CEBPA, MLL, and NRAS mutations in patients with

sion, 0.92; 95% CI, 0.47 to 1.81), whereas in the cytogenetically normal AML. Our results show

subgroup of patients with other, less prognostical that, beyond cytogenetic risk classification, mo-

ly favorable genotypes, there was a significant ad- lecular genetic markers are clinically significant

vantage for the donor group (hazard ratio, 0.61; factors in the response to therapy and survival.

95% CI, 0.40 to 0.94). Figure 3 shows relapse- The frequencies of mutations that we found

free–survival curves, according to donor status, are consistent with those in previous studies.6,21‑34

for the patients with mutant NPM1 without FLT3- The clustering of certain mutations supports the

concept of different classes of mutations (Fig. 1).

Table 2. Hazard Ratios for End Points in the 521 Patients with a Complete Among the hypothetical class II mutations —

Remission, According to Risk Factor. that is, mutations in CEBPA, MLL, and NPM1 that

Risk Factor Hazard Ratio (95% CI) are thought to impair hematopoietic-cell differ-

Relapse or death during complete remission

entiation18-20 — there was only minimal overlap.

Mutant CEBPA 0.48 (0.30–0.75)

Likewise, the class I mutations in FLT3 and NRAS,

which confer a proliferation and survival advan-

Mutant NPM1 without FLT3-ITD 0.44 (0.32–0.61)

tage to the cell,16,17 were largely nonoverlapping.

MLL-PTD 1.56 (1.00–2.43)

In addition, the associations between the two

Family donor available 0.60 (0.44–0.82)

classes of mutations were not equally distributed.

Death NPM1 mutations were associated with both types

Mutant CEBPA 0.50 (0.30–0.83) of activating FLT3 mutations. In contrast, CEBPA

Mutant NPM1 without FLT3-ITD 0.51 (0.37–0.70) mutations and FLT3-ITD were rarely found con-

10-year increase in age 1.33 (1.16–1.53) currently.

The considerable prognostic implications of

1914 n engl j med 358;18 www.nejm.org may 1, 2008

The New England Journal of Medicine

Downloaded from www.nejm.org on October 8, 2010. For personal use only. No other uses without permission.

Copyright © 2008 Massachusetts Medical Society. All rights reserved.

Gene Mutations in Cytogenetically Normal Acute Myeloid Leukemia

the mutations we analyzed confirm and substan-

A

tially extend the results of previous studies.21-34

100

Logistic-regression analyses showed that the gen-

90

otype of mutant NPM1 without FLT3-ITD was

associated with a complete remission after con- 80

Relapse-free Survival (%)

ventional anthracycline and cytarabine–based in- 70

duction therapy. Similarly, the mutant CEBPA gen- 60 Mutant NPM1 without FLT3-ITD

otype was associated with a complete remission, 50

Mutant CEBPA

a correlation that had not been found in previous 40

studies of CEBPA as a single genetic marker.28-30

30

In Cox regression analyses with relapse-free and

20

overall survival as end points, the genotype of

10 Other genotypes

mutant NPM1 without FLT3-ITD and the mutant P<0.001

CEBPA genotype again appeared to be associated 0

0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10

with a favorable outcome. The 4-year rate of over-

Years

all survival for patients with the mutant NPM1

genotype without FLT3-ITD was 60% and for No. at Risk

Other genotypes 212 90 60 38 27 14 9 5 4 2 0

those with mutant CEBPA was 62%. These out- Mutant NPM1 without 136 102 83 64 50 34 24 13 8 3 1

come data are similar to those for patients with FLT3-ITD

Mutant CEBPA 62 40 32 26 17 11 6 4 4 3 0

core-binding-factor leukemias, which are catego-

rized as diseases with cytogenetically favorable B

risks.39-41 In contrast, the subgroups of patients 100

with the FLT3-ITD genotype or the triple-nega- 90

tive genotype consisting of wild-type NPM1 and

80

CEBPA without FLT3-ITD had similarly poor out-

70

Overall Survival (%)

comes, with 4-year rates of relapse-free survival Mutant CEBPA

of 24% and 25%, respectively, and 4-year rates of 60

overall survival of 24% and 33%, respectively. 50

Mutant NPM1

The influence of FLT3-TKD mutations on the 40 without FLT3-ITD

outcome is unsettled. A negative influence was 30

reported in a meta-analysis,42 but in a recent 20

study by the Medical Research Council, TKD mu- Other genotypes

10 P<0.001

tations were associated with a favorable outcome

0

in the entire cohort as well as in patients with 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10

cytogenetically normal AML.43 In our study, FLT3- Years

TKD mutations were not significantly associated

No. at Risk

with the outcome, possibly because other genetic Other genotypes 266 153 90 68 39 22 15 9 7 4 0

markers, NPM1 in particular, were considered in Mutant NPM1 without 150 123 101 75 56 38 25 14 10 4 2

FLT3-ITD

the multivariable analysis. Notably, 54% of pa- Mutant CEBPA 67 54 39 30 19 13 8 6 5 3 0

tients with the mutant FLT3-TKD genotype were

in the subgroup of patients with the prognosti- Figure 2. Kaplan–Meier Survival Estimates, According to Genotype.

cally favorable genotype of mutant NPM1 with- Data are shown for relapse-free survival (Panel A) and overall survival

(Panel B). “Other genotypes” is defined as the FLT3-ITD genotype and the

out FLT3-ITD; in contrast, patients with a FLT3- AUTHOR: Schlenk (Dohner) RETAKE

genotype consisting of wild-type NPM1 and CEBPA

triple-negativeICM

1st

without

2nd

TKD mutation as the sole aberration had a poor REG F FIGURE: 2 of 3

FLT3-ITD. Tick marks represent patients whose data were censored 3rd at the

outcome. last time they CASE

were known to be alive and in complete Revised

remission (Panel A)

Line 4-C were known

Among the various clinical and genetic fea- or whose dataEMail

were censored at the last

ARTIST: ts H/T

time they

H/T

SIZE to be alive

tures at presentation, besides genotype, the only (Panel B). Enon

Combo 22p3

significant factor for overall survival in our study AUTHOR, PLEASE NOTE:

Figure has been redrawn and type has been reset.

was age, and this result was mainly due to the not influence relapse-free survival

Please in the donor

check carefully.

favorable outcome among younger patients who group or in the no-donor group. In contrast,

received a stem-cell transplant from a matched recently published

JOB: 35818data from the Dutch–Belgian ISSUE: 05-01-08

unrelated donor after relapse. However, age did Hemato-Oncology Cooperative Group and the

n engl j med 358;18 www.nejm.org may 1, 2008 1915

The New England Journal of Medicine

Downloaded from www.nejm.org on October 8, 2010. For personal use only. No other uses without permission.

Copyright © 2008 Massachusetts Medical Society. All rights reserved.

The n e w e ng l a n d j o u r na l of m e dic i n e

respect to overall survival, by the favorable re-

A Mutant NPM1 without FLT3-ITD

sults of receipt of a transplant from an HLA-

100

matched unrelated donor after relapse in the no-

90

donor group.

80 The type of AML did not influence any of the

Donor

Relapse-free Survival (%)

70 end points we analyzed, and among patients who

60 had the favorable genotype of mutant NPM1 with-

50 out FLT3-ITD or the favorable mutant CEBPA geno-

40

type, the outcome for patients in whom AML

developed after a myelodysplastic syndrome or

30

No donor after chemotherapy, radiation therapy, or both

20

and the outcome of those with primary AML

10 P=0.71 were similarly favorable.

0 We could assess any association of genotypes

0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10

with the result of postremission therapy,38 since

Years

the four trials we analyzed included assignment

No. at Risk

No donor 97 71 60 46 41 28 19 10 7 3 1

to a treatment group according to whether an

Donor 38 31 23 18 9 6 5 3 1 0 0 HLA-matched donor was available. Notably, only

patients with none of the favorable genotypes

B Other Genotypes — that is, the patients with the FLT3-ITD muta-

100 tion or the genotype consisting of wild-type NPM1

90 and CEBPA without FLT3-ITD — benefited from

80 an allogeneic transplant performed during the

Relapse-free Survival (%)

70 first complete remission (Fig. 3). In contrast,

60

within the subgroup of patients with the favor-

able genotype of mutant NPM1 without FLT3-ITD,

50

the probability of relapse-free survival did not

40 Donor differ according to whether a related donor was

30 available. Similarly, no benefit of an allogeneic

20

No donor transplant has been shown in patients with core-

10 P=0.003 binding-factor leukemias.39-41 In our analysis of

0 cytogenetically normal AML, however, the num-

0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 ber of patients with the mutant CEBPA genotype

Years was too small to draw conclusions regarding the

No. at Risk value of related-donor transplantation during

No donor 148 57 36 19 13 8 6 3 2 1 0

Donor 60 33 24 19 14 6 3 2 2 1 0

the first complete remission. In a recent study,

Gale et al.45 found no beneficial effect of alloge-

Figure 3. Relapse-free Survival among Patients in Whom a Complete Remission neic transplantation in patients with FLT3-ITD. In

Was Achieved, According to the Availability of an HLA-Matched Related Donor. contrast, we focused on subgroups of patients

Data are shown for patients with mutant NPM1 without FLT3-ITD (Panel A) with cytogenetically normal AML who had unfa-

and for patients with AUTHOR:

other genotypes, excluding the mutant

Schlenk (Dohner) RETAKE CEBPA

1st genotype

ICM

(Panel B). Tick marksFIGURE:

represent

vorable genotypes, not only the FLT3-ITD geno-

3 ofpatients

3 whose data were censored

2nd at the

REG F

last time they were known to be alive and in complete remission. 3rd type but also the triple-negative genotype con-

CASE

Line 4-C

Revised

sisting of wild-type NPM1 and CEBPA without

EMail SIZE

ARTIST: ts H/T H/T FLT3-ITD. In the cohort reported on by Gale et al.,

Enon 22p3

Combo

Swiss Group for Clinical Cancer Research showed the rate of allogeneic transplantation during the

that an AUTHOR, PLEASE

age of less thanNOTE:

40 years (the median age

Figure has been redrawn and type has been reset.

first period of complete remission was only 63%

of the studyPleasepopulation)

check carefully. was associated with a (173 of 273 patients), and treatment-related mor-

survival advantage for patients who received a tality was as high as 30%, whereas in our cohort,

JOB: 35818 ISSUE: 05-01-08

transplant from a matched related donor.44 We these values were 82% and 21%, respectively.

found that receipt of an allogeneic transplant Our data provide a basis for refining the risk

from a matched related donor improved relapse- classification of AML. Cytogenetically normal

free survival, but this benefit was mitigated, with AML involving the genotype of mutant NPM1

1916 n engl j med 358;18 www.nejm.org may 1, 2008

The New England Journal of Medicine

Downloaded from www.nejm.org on October 8, 2010. For personal use only. No other uses without permission.

Copyright © 2008 Massachusetts Medical Society. All rights reserved.

Gene Mutations in Cytogenetically Normal Acute Myeloid Leukemia

without FLT3-ITD or the mutant CEBPA genotype volving an unrelated donor — should be explored

should no longer be classified as intermediate- further in patients with the unfavorable geno-

risk leukemia but rather should be classified as type FLT3-ITD or the unfavorable genotype con-

favorable-risk leukemia, together with the core- sisting of wild-type NPM1 and CEBPA without

binding-factor AMLs. We recommend that screen- FLT3-ITD, at least while no successful targeted

ing for NPM1, FLT3, and CEBPA mutations be part therapies are available.

of the initial workup for newly diagnosed AML. Supported by grants from the Bundesministerium für Bildung

Patients with mutant NPM1 without FLT3-ITD may und Forschung (01GI9981 and 01KG0605), the Deutsche José

not benefit from related-donor transplantation as Carreras Leukämie–Stiftung (DJCLS R06/06v), and the Else Kröner-

Fresenius-Stiftung (P38/05//A49/05//F03).

first-line treatment. In contrast, transplantation No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was

involving a related donor — and possibly that in reported.

appendix

Members of the German–Austrian Acute Myeloid Leukemia Study Group were as follows: German Centers: Klinikum Augsburg, Augsburg

— G. Schlimok; Charité, Berlin — R. Arnold, Robert-Rössle Klinik, Berlin — A. Pezzutto; Universitätsklinikum Bonn, Bonn — A. Glasmacher;

Universitätsklinikum Düsseldorf, Düsseldorf — U. Germing; Krankenhaus Essen-Werden, Essen — W. Heit; Universitätsklinikum Frankfurt, Frankfurt

— D. Hoelzer; Städtische Kliniken Frankfurt am Main-Höchst, Frankfurt — H.G. Derigs; Universitätsklinikum Freiburg, Freiburg — M. Lübbert;

Universitätsklinikum Gießen, Gießen — H. Pralle; Wilhelm-Anton-Hospital, Goch — V. Runde; Universitätsklinikum Göttingen, Göttingen — F. Gries-

inger; Universität Hamburg, Hamburg — W. Fiedler; Allgemeines Krankenhaus Altona, Hamburg — H. Salwender; Krankenhaus Siloah, Hannover

— H. Kirchner; Universitätsklinikum Heidelberg, Heidelberg — M. Hensel; Universitätsklinikum Hamburg–Saar, Hamburg — F. Hartmann; Städ

tisches Klinikum Karlsruhe, Karlsruhe — J.T. Fischer; Universitätsklinikum Kiel, Kiel — M. Kneba; Wissenchaftlicher Service Pharma, Langenfeld — A.

Hinke; Caritas-Krankenhaus Lebach, Lebach — S. Kremers; Technische Universität München, Munich — K. Götze; Klinikum München-Schwabing,

Munich — C. Waterhouse; Klinikum Oldenburg, Oldenburg — F. del Valle; Caritas-Klinik St. Theresia, Saarbrücken — A. Matzdorff; Bürgerhospital

Stuttgart, Stuttgart — W. Grimminger; Katharinenhospital Stuttgart, Stuttgart — H.G. Mergenthaler; Krankenhaus der Barmherzigen Brüder, Trier

— H. Kirchen; Universitätsklinikum Tübingen, Tübingen — P. Brossart; Universitätsklinikum Ulm, Ulm — L. Bergmann; Klinikum Wuppertal,

Wuppertal — Aruna Raghavachar; Austrian Centers: Universitätsklinikum Innsbruck, Innsbruck — A. Petzer; Hanuschkrankenhaus, Vienna — E.

Koller; Belgian Center: Universitair Ziekenhuis Gent, Gent — L. Noens.

References

1. Byrd JC, Mrózek K, Dodge RK, et al. Prognostically useful gene-expression pro- 16. Stirewalt DL, Radich JP. The role of

Pretreatment cytogenetic abnormalities files in acute myeloid leukemia. N Engl J FLT3 in haematopoietic malignancies. Nat

are predictive of induction success, cumu- Med 2004;350:1617-28. Rev Cancer 2003;3:650-65.

lative incidence of relapse, and overall sur- 9. Caligiuri MA, Schichmann SA, Strout 17. Schubbert S, Bollag G, Shannon K.

vival in adult patients with de novo acute MP, et al. Molecular rearrangement of the Deregulated Ras signaling in developmen-

myeloid leukemia: results from Cancer ALL-1 gene in acute myeloid leukemia tal disorders: new tricks for an old dog.

and Leukemia Group B (CALGB 8461). without cytogenetic evidence of 11q23 Curr Opin Genet Dev 2007;17:15-22.

Blood 2002;100:4325-36. chromosomal translocations. Cancer Res 18. Nerlov C. C/EBPalpha mutations in

2. Grimwade D, Walker H, Oliver F, et al. 1994;54:370-3. acute myeloid leukaemias. Nat Rev Cancer

The importance of diagnostic cytogenet- 10. Nakao M, Yokota S, Iwai T, et al. In- 2004;4:394-400.

ics on outcome in AML: analysis of 1,612 ternal tandem duplication of the flt3 gene 19. Ernst P, Wang J, Korsmeyer SJ. The role

patients entered into the MRC AML 10 found in acute myeloid leukemia. Leuke- of MLL in hematopoiesis and leukemia.

trial. Blood 1998;92:2322-33. mia 1996;10:1911-8. Curr Opin Hematol 2002;9:282-7.

3. Mrózek K, Heerema NA, Bloomfield 11. Yamamoto Y, Kiyoi H, Nakano Y, et al. 20. Grisendi S, Mecucci C, Falini B, Pan-

CD. Cytogenetics in acute leukemia. Blood Activating mutation of D835 within the ac- dolfi PP. Nucleophosmin and cancer. Nat

Rev 2004;18:115-36. tivation loop of FLT3 in human hemato- Rev Cancer 2006;6:493-505.

4. Estey E, Döhner H. Acute myeloid leu- logic malignancies. Blood 2001;97:2434-9. 21. Whitman SP, Archer KJ, Feng L, et al.

kaemia. Lancet 2006;368:1894-907. 12. Falini B, Mecucci C, Tiacci E, et al. Absence of the wild-type allele predicts

5. Löwenberg B, Griffin JD, Tallman MS. Cytoplasmic nucleophosmin in acute my- poor prognosis in adult de novo acute my-

Acute myeloid leukemia and acute promy- elogenous leukemia with a normal karyo- eloid leukemia with normal cytogenetics

elocytic leukemia. Hematology Am Soc type. N Engl J Med 2005;352:254-66. [Erra and the internal tandem duplication of

Hematol Educ Program 2003:82-101. tum, N Engl J Med 2005;352:740.] FLT3: a Cancer and Leukemia Group B

6. Mrózek K, Dohner H, Bloomfield CD. 13. Pabst T, Mueller BU, Zhang P, et al. study. Cancer Res 2001;61:7233-9.

Influence of new molecular prognostic Dominant-negative mutations of CEBPA, 22. Kottaridis PD, Gale RE, Frew ME, et al.

markers in patients with karyotypically encoding CCAAT/enhancer binding pro- The presence of a FLT3 internal tandem

normal acute myeloid leukemia: recent ad- tein-alpha (C/EBP alpha), in acute myeloid duplication in patients with acute myeloid

vances. Curr Opin Hematol 2007;14:106- leukemia. Nat Genet 2001;27:263-70. leukemia (AML) adds important prognos-

14. 14. Bos JL, Toksoz D, Marshall CJ, et al. tic information to cytogenetic risk group

7. Bullinger L, Döhner K, Bair E, et al. Amino-acid substitutions at codon 13 of and response to the first cycle of chemo-

Use of gene-expression profiling to iden- the N-ras oncogene in human acute mye therapy: analysis of 854 patients from the

tify prognostic subclasses in adult acute loid leukaemia. Nature 1985;315:726-30. United Kingdom Medical Research Coun-

myeloid leukemia. N Engl J Med 2004;350: 15. Gilliland DG, Griffin JD. The roles cil AML 10 and 12 trials. Blood 2001;98:

1605-16. of FLT3 in hematopoiesis and leukemia. 1752-9.

8. Valk PJ, Verhaak RG, Beijen MA, et al. Blood 2002;100:1532-42. 23. Fröhling S, Schlenk RF, Breitruck J, et

n engl j med 358;18 www.nejm.org may 1, 2008 1917

The New England Journal of Medicine

Downloaded from www.nejm.org on October 8, 2010. For personal use only. No other uses without permission.

Copyright © 2008 Massachusetts Medical Society. All rights reserved.

Gene Mutations in Cytogenetically Normal Acute Myeloid Leukemia

al. Prognostic significance of activating tic markers in intermediate-risk AML. core binding factor acute myeloid leuke-

FLT3 mutations in younger adults (16 to Hematol J 2003;4:31-40. mia: a survey of the German Acute My-

60 years) with acute myeloid leukemia and 31. Döhner K, Schlenk RF, Habdank M, eloid Leukemia Intergroup. J Clin Oncol

normal cytogenetics: a study of the AML et al. Mutant nucleophosmin (NPM1) pre- 2004;22:3741-50.

Study Group Ulm. Blood 2002;100:4372- dicts favorable prognosis in younger adults 40. Marcucci G, Mrózek K, Ruppert AS, et

80. with acute myeloid leukemia and normal al. Prognostic factors and outcome of core

24. Thiede C, Steudel C, Mohr B, et al. cytogenetics: interaction with other gene binding factor acute myeloid leukemia pa-

Analysis of FLT3-activating mutations in mutations. Blood 2005;106:3740-6. tients with t(8;21) differ from those of

979 patients with acute myelogenous leu- 32. Schnittger S, Schoch C, Kern W, et al. patients with inv(16): a Cancer and Leuke-

kemia: association with FAB subtypes and Nucleophosmin gene mutations are pre- mia Group B study. J Clin Oncol 2005;23:

identification of subgroups with poor dictors of favorable prognosis in acute 5705-17.

prognosis. Blood 2002;99:4326-35. myelogenous leukemia with a normal 41. Delaunay J, Vey N, Leblanc T, et al.

25. Schnittger S, Schoch C, Dugas M, et al. karyotype. Blood 2005;106:3733-9. Prognosis of inv(16)/t(16;16) acute myeloid

Analysis of FLT3 length mutations in 1003 33. Verhaak RG, Goudswaard CS, van leukemia (AML): a survey of 110 cases

patients with acute myeloid leukemia: Putten W, et al. Mutations in nucleophos- from the French AML Intergroup. Blood

correlation to cytogenetics, FAB subtype, min (NPM1) in acute myeloid leukemia 2003;102:462-9.

and prognosis in the AMLCG study and (AML): association with other gene ab- 42. Yanada M, Matsuo K, Suzuki T, Kiyoi

usefulness as a marker for the detection normalities and previously established H, Naoe T. Prognostic significance of FLT3

of minimal residual disease. Blood 2002; gene expression signatures and their fa- internal tandem duplication and tyrosine

100:59-66. vorable prognostic significance. Blood kinase domain mutations for acute my-

26. Döhner K, Tobis K, Ulrich R, et al. 2005;106:3747-54. eloid leukemia: a meta-analysis. Leukemia

Prognostic significance of partial tandem 34. Thiede C, Koch S, Creutzig E, et al. 2005;19:1345-9.

duplications of the MLL gene in adult pa- Prevalence and prognostic impact of NPM1 43. Mead AJ, Linch DC, Hills RK, Wheat-

tients 16 to 60 years old with acute my- mutations in 1485 adult patients with ley K, Burnett AK, Gale RE. FLT3 tyrosine

eloid leukemia and normal cytogenetics: acute myeloid leukemia (AML). Blood 2006; kinase domain mutations are biologically

a study of the Acute Myeloid Leukemia 107:4011-20. distinct from and have a significantly

Study Group Ulm. J Clin Oncol 2002;20: 35. Cheson BD, Bennett JM, Kopecky KJ, more favorable prognosis than FLT3 inter-

3254-61. et al. Revised recommendations of the nal tandem duplications in patients with

27. Caligiuri MA, Strout MP, Lawrence D, International Working Group for Diagno- acute myeloid leukemia. Blood 2007;110:

et al. Rearrangement of ALL1 (MLL) in sis, Standardization of Response Criteria, 1262-70.

acute myeloid leukemia with normal cyto- Treatment Outcomes, and Reporting Stan- 44. Cornelissen JJ, van Putten WL, Ver-

genetics. Cancer Res 1998;58:55-9. dards for Therapeutic Trials in Acute donck LF, et al. Results of a HOVON/SAKK

28. Fröhling S, Schlenk RF, Stolze I, et al. Myeloid Leukemia. J Clin Oncol 2003;21: donor versus no-donor analysis of myelo

CEBPA mutations in younger adults with 4642-9. ablative HLA-identical sibling stem cell

acute myeloid leukemia and normal cyto- 36. Harrell FE. Regression modeling strat- transplantation in first remission acute

genetics: prognostic relevance and analy- egies: with applications to linear models, myeloid leukemia in young and middle-

sis of cooperating mutations. J Clin Oncol logistic regression, and survival analysis. aged adults: benefits for whom? Blood

2004;22:624-33. New York: Springer-Verlag, 2001. 2007;109:3658-66.

29. Preudhomme C, Sagot C, Boissel N, et 37. R: a language and environment for 45. Gale RE, Hills R, Kottaridis PD, et al.

al. Favorable prognostic significance of statistical computing. Vienna: R Founda- No evidence that FLT3 status should be con

CEBPA mutations in patients with de novo tion for Statistical Computing, 2007. sidered as an indicator for transplantation

acute myeloid leukemia: a study from the 38. Sargent DJ, Conley BA, Allegra C, Col- in acute myeloid leukemia (AML): an analy

Acute Leukemia French Association (ALFA). lette L. Clinical trial designs for predic- sis of 1135 patients, excluding acute promy-

Blood 2002;100:2717-23. tive marker validation in cancer treatment elocytic leukemia, from the UK MRC AML10

30. Barjesteh van Waalwijk van Doorn- trials. J Clin Oncol 2005;23:2020-7. and 12 trials. Blood 2005;106:3658-65.

Khosrovani S, Erpelinck C, Meijer J, et al. 39. Schlenk RF, Benner A, Krauter J, et al. Copyright © 2008 Massachusetts Medical Society.

Biallelic mutations in the CEBPA gene and Individual patient data-based meta-analy-

low CEBPA expression levels as prognos- sis of patients aged 16 to 60 years with

posting presentations at medical meetings on the internet

Posting an audio recording of an oral presentation at a medical meeting on the

Internet, with selected slides from the presentation, will not be considered prior

publication. This will allow students and physicians who are unable to attend the

meeting to hear the presentation and view the slides. If there are any questions

about this policy, authors should feel free to call the Journal’s Editorial Offices.

1918 n engl j med 358;18 www.nejm.org may 1, 2008

The New England Journal of Medicine

Downloaded from www.nejm.org on October 8, 2010. For personal use only. No other uses without permission.

Copyright © 2008 Massachusetts Medical Society. All rights reserved.

You might also like

- Record Sheet, Year 1: Please Submit These Record Sheets To Your Instructor After Completing The Simulation. Thank You!Document5 pagesRecord Sheet, Year 1: Please Submit These Record Sheets To Your Instructor After Completing The Simulation. Thank You!Randi Kosim SiregarNo ratings yet

- Awesome Engineering Activities For Kids - 50+ Exciting STEAM Projects To Design and Build (Awesome STEAM Activities For Kids)Document227 pagesAwesome Engineering Activities For Kids - 50+ Exciting STEAM Projects To Design and Build (Awesome STEAM Activities For Kids)Leonardo Rodrigues86% (7)

- CH 5 Test BankDocument75 pagesCH 5 Test BankJB50% (2)

- New England Journal Medicine: The ofDocument16 pagesNew England Journal Medicine: The ofMauricio FemeníaNo ratings yet

- JAMA Leukemia 1Document3 pagesJAMA Leukemia 1indra_gosalNo ratings yet

- Ebmt Book AmlDocument15 pagesEbmt Book AmlAlessandro AlmeidaNo ratings yet

- Acute Myeloid Leukemia With Mutated NPM1 Mimics Acute Promyelocytic Leukemia PresentationDocument9 pagesAcute Myeloid Leukemia With Mutated NPM1 Mimics Acute Promyelocytic Leukemia PresentationMunawwar SaukaniNo ratings yet

- BMT 2016194Document8 pagesBMT 2016194Hito OncoNo ratings yet

- How I Treat Pediatri CacutemyeloidleukemiaDocument10 pagesHow I Treat Pediatri CacutemyeloidleukemiaValeria FuentesNo ratings yet

- Biol Blood Marrow Transplant 21 (2015) 653e660Document8 pagesBiol Blood Marrow Transplant 21 (2015) 653e660Rhinaldy DanaraNo ratings yet

- Atm AllDocument6 pagesAtm AllsccNo ratings yet

- Abnormalities of RUNX1, CBFB, CEBPA, and NPM1 Genes in Acute Myeloid LeukemiaDocument10 pagesAbnormalities of RUNX1, CBFB, CEBPA, and NPM1 Genes in Acute Myeloid LeukemiaAndikhaNo ratings yet

- Evaluation of C3435T MDR1 Gene Polymorphism in Adult Patient With Acute Lymphoblastic LeukemiaDocument4 pagesEvaluation of C3435T MDR1 Gene Polymorphism in Adult Patient With Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemiaali99No ratings yet

- Nejme 1200409Document2 pagesNejme 1200409Arie Krisnayanti Ida AyuNo ratings yet

- Minimal Residual Disease in Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia: Dario CampanaDocument6 pagesMinimal Residual Disease in Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia: Dario CampanaJAIR_valencia3395No ratings yet

- The Immune Microenvironment, Genome-Wide Copy Number Aberrations, and Survival in MesotheliomaDocument10 pagesThe Immune Microenvironment, Genome-Wide Copy Number Aberrations, and Survival in MesotheliomaTaloipaNo ratings yet

- Anemia Aplastic JournalDocument13 pagesAnemia Aplastic JournalGenoveva Maditias Dwi PertiwiNo ratings yet

- How I Treat Acute Myeloid LeukemiaDocument10 pagesHow I Treat Acute Myeloid LeukemiaSutiara Prihatining TyasNo ratings yet

- 2007 MLH1Document6 pages2007 MLH1Mericia Guadalupe Sandoval ChavezNo ratings yet

- Aml NGSDocument13 pagesAml NGSRobie MikhelashviliNo ratings yet

- JPTM 2019 02 08Document8 pagesJPTM 2019 02 08m8f5mwpzwyNo ratings yet

- Acute Myeloid LeukemiaDocument20 pagesAcute Myeloid LeukemiahemendreNo ratings yet

- CNCR 21619Document7 pagesCNCR 21619Syed Shah MuhammadNo ratings yet

- The Pathophysiology of Pure Red Cell Aplasia: Implications For TherapyDocument9 pagesThe Pathophysiology of Pure Red Cell Aplasia: Implications For TherapyPhương NhungNo ratings yet

- Genomic Mutations of Primary and Metastatic LungDocument9 pagesGenomic Mutations of Primary and Metastatic LungDiana AyuNo ratings yet

- Tse 2014Document5 pagesTse 2014Ke XuNo ratings yet

- Aberrant DNA Methylation Is A Dominant Mechanism in MDS Progression To AMLDocument11 pagesAberrant DNA Methylation Is A Dominant Mechanism in MDS Progression To AMLJuan GomezNo ratings yet

- Immunotherapy For Head and Neck CancerDocument21 pagesImmunotherapy For Head and Neck CancerLuane SenaNo ratings yet

- Article 2Document5 pagesArticle 2Mahadev HaraniNo ratings yet

- Jones PA Et Al. 2019 Epigetnic Therapy in Immune-OncologyDocument11 pagesJones PA Et Al. 2019 Epigetnic Therapy in Immune-OncologyJasmyn KimNo ratings yet

- Pi Is 1083879117306547Document6 pagesPi Is 1083879117306547Umang PrajapatiNo ratings yet

- How I Treat T-Cell Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia in AdultsDocument10 pagesHow I Treat T-Cell Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia in AdultsIndahNo ratings yet

- Identification of Recurring Tumor Specific Somatic Mutations in AML by Transcriptome Seq Greif2011Document7 pagesIdentification of Recurring Tumor Specific Somatic Mutations in AML by Transcriptome Seq Greif2011mrkhprojectNo ratings yet

- Methylation Profiling in Acute Myeloid Leukemia: Neoplasia Gene ExpressionDocument8 pagesMethylation Profiling in Acute Myeloid Leukemia: Neoplasia Gene ExpressionJuan GomezNo ratings yet

- After CorrectionDocument22 pagesAfter CorrectionRania GebbaNo ratings yet

- Prognostic Factors in Acute Myeloid Leukaemia 4: Bob LoèwenbergDocument11 pagesPrognostic Factors in Acute Myeloid Leukaemia 4: Bob LoèwenbergStephania SandovalNo ratings yet

- A Novel Somatic K-Ras Mutation in Juvenile Myelomonocytic LeukemiaDocument2 pagesA Novel Somatic K-Ras Mutation in Juvenile Myelomonocytic LeukemiamahanteshNo ratings yet

- Prognosis and Therapy When Acute Promyelocytic Leukemia and Other "Good Risk" Acute Myeloid Leukemias Occur As A Therapy Myeloid NeoplasmDocument7 pagesPrognosis and Therapy When Acute Promyelocytic Leukemia and Other "Good Risk" Acute Myeloid Leukemias Occur As A Therapy Myeloid NeoplasmClinica MonserratNo ratings yet

- Abstract NKI KnoopsDocument1 pageAbstract NKI Knoopsakbar_rozaaqNo ratings yet

- CoverDocument7 pagesCoveryasmineNo ratings yet

- Aproximación A La LLA T Del AdultoDocument9 pagesAproximación A La LLA T Del AdultoJuan Antonio LópezNo ratings yet

- Article OralDocument36 pagesArticle Oralamina-fakirproNo ratings yet

- Therapy Induced Mutagenesis in Relapsed ALL Is Supported by Mutatio - 2020 - BloDocument3 pagesTherapy Induced Mutagenesis in Relapsed ALL Is Supported by Mutatio - 2020 - BloJose Luis Agudelo MosqueraNo ratings yet

- Parcial 1 - TP 4. Chagas BENEFITDocument12 pagesParcial 1 - TP 4. Chagas BENEFITVictoria ChristieNo ratings yet

- KLP 1Document15 pagesKLP 1Arig Al Fath OdeNo ratings yet

- SF3B1 and Other Novel Cancer Genes: in Chronic Lymphocytic LeukemiaDocument10 pagesSF3B1 and Other Novel Cancer Genes: in Chronic Lymphocytic LeukemiaRafael ColinaNo ratings yet

- Neuroblastoma: Biological Insights Into A Clinical Enigma: Garrett M. BrodeurDocument14 pagesNeuroblastoma: Biological Insights Into A Clinical Enigma: Garrett M. BrodeurMouris DwiputraNo ratings yet

- New England Journal Medicine: The ofDocument12 pagesNew England Journal Medicine: The ofJuan Pablo AnselmoNo ratings yet

- Acute Myeloid Leukemia...Document20 pagesAcute Myeloid Leukemia...hemendre0% (1)

- 976 FullDocument7 pages976 FullFirda PotterNo ratings yet

- Successful Management of Granulocytic Sarcoma With Co - 2016 - Pediatric HematolDocument2 pagesSuccessful Management of Granulocytic Sarcoma With Co - 2016 - Pediatric HematolHawin NurdianaNo ratings yet

- Leucemia GenomicaDocument14 pagesLeucemia GenomicaNathalie Soler BarreraNo ratings yet

- Bacher 2005Document7 pagesBacher 2005Josué Cristhian Del Valle HornaNo ratings yet

- Wu 2016Document8 pagesWu 2016Anonymous n2DPWfNuNo ratings yet

- Nej Mo A 1100391Document12 pagesNej Mo A 1100391Abran HadiqNo ratings yet

- Recent Advances in Managing Acute Lymphoblastic LeukemiaDocument13 pagesRecent Advances in Managing Acute Lymphoblastic LeukemiaAndra GeorgianaNo ratings yet

- Jco 2001 19 18 3852Document9 pagesJco 2001 19 18 3852Luis SanchezNo ratings yet

- Adult Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia: Concepts and StrategiesDocument12 pagesAdult Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia: Concepts and StrategiesdrravesNo ratings yet

- Immuno TherapyDocument20 pagesImmuno TherapyAttis PhrygiaNo ratings yet

- American J Hematol - 2006 - Takahashi - Methylprednisolone Pulse Therapy For Severe Immune Thrombocytopenia Associated WithDocument5 pagesAmerican J Hematol - 2006 - Takahashi - Methylprednisolone Pulse Therapy For Severe Immune Thrombocytopenia Associated WithMohan PrasadNo ratings yet

- Biology of Blood and Marrow TransplantationDocument6 pagesBiology of Blood and Marrow TransplantationFrankenstein MelancholyNo ratings yet

- Imatinib Phase3 NEJM2003Document11 pagesImatinib Phase3 NEJM2003Stefán Broddi DaníelssonNo ratings yet

- Tumor Immune Microenvironment in Cancer Progression and Cancer TherapyFrom EverandTumor Immune Microenvironment in Cancer Progression and Cancer TherapyPawel KalinskiNo ratings yet

- Early Online Release: The DOI For This Manuscript Is Doi: 10.5858/ arpa.2013-0384-RADocument5 pagesEarly Online Release: The DOI For This Manuscript Is Doi: 10.5858/ arpa.2013-0384-RAmonamustafaNo ratings yet

- The Impact of Accreditation To ISO/IEC 17025 in Testing Laboratories in MauritiusDocument105 pagesThe Impact of Accreditation To ISO/IEC 17025 in Testing Laboratories in Mauritiusfayiz100% (1)

- Leukaemia or Leukaemoid, Down Syndrome or Not?: Case ReportDocument2 pagesLeukaemia or Leukaemoid, Down Syndrome or Not?: Case ReportmonamustafaNo ratings yet

- RTK InhDocument9 pagesRTK InhmonamustafaNo ratings yet

- Unit 1: A1 Coursebook AudioscriptsDocument39 pagesUnit 1: A1 Coursebook AudioscriptsRaul GaglieroNo ratings yet

- Siemens 3VT MCCBDocument39 pagesSiemens 3VT MCCBerkamlakar2234No ratings yet

- Job Hazard Analysis: Basic Job Steps Potential Hazards Recommended Actions or ProcedureDocument3 pagesJob Hazard Analysis: Basic Job Steps Potential Hazards Recommended Actions or ProcedureBernard Christian DimaguilaNo ratings yet

- Evaluation of Trajectory Model For Differential Steering Using Numerical MethodDocument6 pagesEvaluation of Trajectory Model For Differential Steering Using Numerical MethodNaufal RachmatullahNo ratings yet

- Torrent WorkingDocument7 pagesTorrent WorkingsirmadamstudNo ratings yet

- Bangladesh University of Professionals (Bup)Document17 pagesBangladesh University of Professionals (Bup)oldschoolNo ratings yet

- Unit 4 ListeningDocument3 pagesUnit 4 ListeningAnh TamNo ratings yet

- CBC TMDocument108 pagesCBC TMChryz SantosNo ratings yet

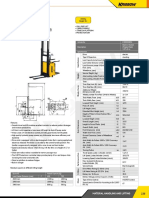

- Electric Stacker: Article No. KW0500894 Description Electric Stacker (Triplex Mast) 1.5T x3 M SpecificationDocument1 pageElectric Stacker: Article No. KW0500894 Description Electric Stacker (Triplex Mast) 1.5T x3 M SpecificationAsty RikyNo ratings yet

- Mos-Installation Stainless Steel Eye Bolt Filter TankDocument5 pagesMos-Installation Stainless Steel Eye Bolt Filter Tankhabibullah.centroironNo ratings yet

- ATS Kingston Heath CustomerDocument63 pagesATS Kingston Heath CustomerDevNo ratings yet

- Pivot 4A Lesson Exemplar Using The Idea Instructional ProcessDocument14 pagesPivot 4A Lesson Exemplar Using The Idea Instructional ProcessJocelyn100% (1)

- PET-UT-U4 Without AnswersDocument2 pagesPET-UT-U4 Without AnswersAlejandroNo ratings yet

- Prist University, Trichy Campus Department of Comnputer Science and Engineering B.Tech - Arrear Details (Part Time)Document2 pagesPrist University, Trichy Campus Department of Comnputer Science and Engineering B.Tech - Arrear Details (Part Time)diltvkNo ratings yet

- Week 10 RPH ENGLISHDocument4 pagesWeek 10 RPH ENGLISHAin HazirahNo ratings yet

- Letters From England: by Don Manuel Alvarez EspriellaDocument2 pagesLetters From England: by Don Manuel Alvarez EspriellaPickering and ChattoNo ratings yet

- SSP 666 Audi A8 Type 4N Infotainment and Audi ConnectDocument72 pagesSSP 666 Audi A8 Type 4N Infotainment and Audi Connectylk1No ratings yet

- Online Shop Dengan Norma Subjektif Sebagai Variabel ModerasiDocument13 pagesOnline Shop Dengan Norma Subjektif Sebagai Variabel ModerasiNicky BrenzNo ratings yet

- RAMMINGDocument3 pagesRAMMINGmatheswaran a sNo ratings yet

- Temario Final Ingles 5°b PrimariaDocument1 pageTemario Final Ingles 5°b PrimariainstitutovalladolidNo ratings yet

- Israel's Agriculture BookletDocument58 pagesIsrael's Agriculture BookletShrikant KajaleNo ratings yet

- Make Wire Transfers Through Online Banking From AnywhereDocument2 pagesMake Wire Transfers Through Online Banking From AnywhereDani PermanaNo ratings yet

- The Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule, Module 4: Application of The Revised Algorithms in An Independent, Well-Defined, Dutch Sample (N 93)Document11 pagesThe Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule, Module 4: Application of The Revised Algorithms in An Independent, Well-Defined, Dutch Sample (N 93)Laura CamusNo ratings yet

- The Piano Lesson Hand Out - Ma Rainey QuizDocument5 pagesThe Piano Lesson Hand Out - Ma Rainey QuizJonathan GellertNo ratings yet

- Supervisi Akademik Melalui Pendekatan Kolaboratif Oleh Kepala Sekolah Dalammeningkatkan Kualitas Pembelajarandisd Yari DwikurnaningsihDocument11 pagesSupervisi Akademik Melalui Pendekatan Kolaboratif Oleh Kepala Sekolah Dalammeningkatkan Kualitas Pembelajarandisd Yari DwikurnaningsihKhalid Ibnu SinaNo ratings yet

- MODBUS TCP/IP (0x/1x Range Adjustable) : HMI SettingDocument5 pagesMODBUS TCP/IP (0x/1x Range Adjustable) : HMI SettingÁnh VũNo ratings yet

- Sccan Resourcemanual Allpages Update v2Document154 pagesSccan Resourcemanual Allpages Update v2SiangNo ratings yet