Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Unesco - Eolss Sample Chapters: Cultural and Social Geography

Unesco - Eolss Sample Chapters: Cultural and Social Geography

Uploaded by

soumi mitraOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Unesco - Eolss Sample Chapters: Cultural and Social Geography

Unesco - Eolss Sample Chapters: Cultural and Social Geography

Uploaded by

soumi mitraCopyright:

Available Formats

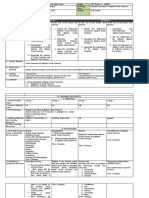

GEOGRAPHY – Vol.

II - Cultural and Social Geography - Paul Claval

CULTURAL AND SOCIAL GEOGRAPHY

Paul Claval

Université de Paris-Sorbonne, Paris, France.

Keywords: communication, culture, environment, factorial ecology, landscape,

Marxism, naturalism, neo-positivism, phenomenology, positivism, society, techniques,

urban ecology

Contents

1. Introduction

1.1. Birth and Development of Cultural and Social Studies in Geography between 1880

and 1950

S

TE S

1.1.1. Cultural Geography as a Study of Landscapes

1.1.2. Cultural Geography as the Study of Genres de Vie

R

AP LS

1.1.3. The Early Forms of Social Geography

1.2. The Impact of the "New" Geography on Cultural and Social Studies: from the

1950s to the early 1970s

C EO

1.2.1. The Time of Social Ecologies

1.2.2. The Social Geography of Rural Areas

1.2.3. Relevance and the Growing Success of Marxist Social Analysis

1.2.4. Cultural Geography: Decline and Unsuccessful Re-orientations

E –

1.3. The Contemporary Situation

H

1.3.1. The Renewal of Cultural Geography

PL O

1.3.2. New Directions of Research in Cultural Geography

1.3.3. New Conceptions of Social Geography

M SC

2. The Cultural Approach and the New Epistemological Bases of Geography

3. Conclusion

Bibliography

SA NE

Biographical Sketch

Summary

U

The interest in cultural and social problems developed in human geography from the

end of the nineteenth century. For half a century, the emphasis was more on culture, its

impact on landscape, the role of techniques, the notion of genre de vie than on social

structures and hierarchies. With the neo-positivist orientations of the new geography of

the 1960s, the interest for culture receded and social themes became increasingly

important. During the last generation, the role of culture appears central in the

reconstruction of geography which was born from the new concerns with the lived

experience of space and social justice. The social and cultural aspects of geography

appear increasingly intertwined.

1. Introduction

In a way, cultural and social geography is as old as human geography. The term social

geography was introduced, as an equivalent to human geography, in the 1880s (Dunbar,

©Encyclopedia of Life Support Systems(EOLSS)

GEOGRAPHY – Vol. II - Cultural and Social Geography - Paul Claval

1977). Friedrich Ratzel, the father of modern Anthropogeographie, stressed the

opposition between Natur- and Kulturvölker, that meant that culture was a fundamental

dimension of the field he was creating (Ratzel, 1882-1891).

The studies dealing with the social and cultural aspects of human distributions played a

significant role during the first half of the twentieth century. Cultural geography and

social geography were then generally considered as independent sectors of the

discipline. The curiosity for the role of cultural factors in geography was stronger than

the interest for social distributions. During the last fifty years, the situation deeply

changed. Between the 1950s and the 1970s, social geography appeared as a research

frontier for the whole discipline. Simultaneously, cultural studies experienced a crisis

which was partly linked with the modernization of cultures, and partly linked with the

new ambitions of geographers. Since the early 1970s, the development of critical and

phenomenological approaches has strengthened the two subfields. They have ceased to

appear as independent.

S

TE S

The paper will analyze rapidly the birth and development of cultural and social studies

R

AP LS

in geography between 1880 and 1950, and the impact of the "new" geography on both

fields during the 1950s, 1960s and early 1970s. It will cover with more detail

contemporary evolution.

C EO

1.1. Birth and Development of Cultural and Social Studies in Geography between

1880 and 1950

E –

Human geography appeared at the end of the nineteenth century. Its birth was linked

H

with the development of evolutionism: human groups had to be analyzed along

PL O

perspectives similar to those used for other live beings; the influence of environment on

the nature of humans, and the social constructions they were responsible for, had to be

M SC

evaluated. As a result, human geography was more considered a natural science than a

social one. Such a view reduced quite evidently its interest for human cultures and

social structures but did not prevent its development.

SA NE

In the prevalent evolutionist perspective, it soon appeared that human groups differed

from animal ones because they were not completely governed by their instincts; they

had developed sets of techniques, know-how, knowledge, which acted as a buffer

U

between them and the environment. Hence the opposition between Naturvölker, which

lacked efficient means of protection against the harshness of nature, and Kulturvölker,

which had developed a full array of tools for harnessing natural forces and using them

(Ratzel, 1882-1891).

1.1.1. Cultural Geography as a Study of Landscapes

Because human geography was essentially conceived as a natural science dealing with

the relations of human groups with their environments, cultural studies were mainly

concerned with man/milieu relationships until mid twentieth century. This perspective

was conducive to an emphasis on a few topics.

How did the environment shape human distributions, human behavior and the human

organization of space? The old hippocratic hypothesis was still alive at the end of the

©Encyclopedia of Life Support Systems(EOLSS)

GEOGRAPHY – Vol. II - Cultural and Social Geography - Paul Claval

nineteenth century (Claval, 1988-a), but it soon appeared that other influences played a

more decisive role. People had to live on the resources of the milieus they inhabited. It

was mainly through the constraints generated in this way that environment controlled

human life. It meant that geographers had to focus on the material cultures of the groups

they studied, the way they got rid of the natural vegetation and fauna, substituted

cultivated ecological pyramids to the natural ones, were struck by endemics linked with

the local living environment, or epidemics born out of human or animal mobility.

In Germany, this interest for the cultural bases of human life was expressed by the

development of landscape studies: they showed how human groups had transformed and

organized natural environments and built cultural landscapes out of them. The emphasis

was on deforestation (Schlüter, 1899), the introduction of cultivated plants and domestic

animals (Hahn, 1896; 1909; 1914), the field systems and the ways they were operated

(Meitzen, 1895): the culture of civilized groups was equated with farming and cattle-

raising, while hunting, fishing and food collecting were considered as the productive

S

TE S

bases of primitive ones. Urban and industrial landscapes showed how social life was

R

AP LS

conducive to other forms of man/milieu relationships, thanks to the mobility of goods

and persons and the relaxation of many local ecological constraints. Geographers did

not display, however, as much interest for urban realities as rural ones.

C EO

The analysis of cultural landscapes was mainly conceived in functional terms: field

structures, for instance, were thought as a way to translate into a spatial form the

imperative of crop rotation and the combination of agriculture and cattle raising within

E –

communities (Claval, 1995-a). Geographers grew increasingly conscious, however, of

H

the existence of inherited features in the landscape: a part of them reflected past

PL O

functional organizations.

M SC

Thanks to Carl Sauer, American geographers imported many ideas from Germany, and

more particularly the idea of cultural geography as a study of landscapes (Sauer, 1925;

Leighly, 1963). Sauer was the first to conceive cultural geography as a subfield within

human geography and to use the term as such. His approach of landscape analysis

SA NE

differed from his German models in one way: he stressed more than them the role of

human beings in transforming the biological components of vegetation, the nature of

soils, and the forms of erosion. He had a keen interest in landscapes as biological

U

realities shaped by human action. For him, a cultural geographer had first to hold a good

knowledge of botany!

The interest in the live components of landscapes had other consequences. From the

1890s in Germany, geographers tried to explain the origin and dispersal of agriculture

and cattle-raising. The leading figure in that field was Eduard Hahn (Hahn, 1909; 1914).

He was the first to underscore the fundamental duality of agricultural systems: one was

based on ploughing, the production of grain and the association of farming and cattle

raising; the other relied on hoeing and the use of cuttings for plant reproduction. Hahn

showed in this way that the problem of agriculture origin and dispersal was a double

one. Geographers had to discover the hearths of the two revolutions which transformed

mesolithic hunters/gatherers into neolithic farmers.

Carl Sauer was also fascinated by the problem of agriculture origins and dispersal

©Encyclopedia of Life Support Systems(EOLSS)

GEOGRAPHY – Vol. II - Cultural and Social Geography - Paul Claval

(Sauer, 1952). He believed that geographers had to analyze the responsibility of human

cultures for the disruption of natural equilibria and the subsequent development of

erosion (Sauer, 1938).

1.1.2. Cultural Geography as the Study of Genres de Vie

Another approach for the study of man/milieu relationships in a cultural perspective

developed in parallel to the landscape school. It flourished mainly in France. Instead of

focusing on landscapes, French geographers considered that their main task was to

explain the distribution of populations. Human densities differed because natural

environments changed from place to place, but also because different social groups did

not use the same array of techniques when exploiting the same environment. Hence the

emphasis on genres de vie. As developed by Vidal de la Blache (1902; 1911), the notion

was a complex one. 1- It had an ecological foundation: genres de vie grew out of the

choice of crops and forms of cattle-raising adapted to specific environments. 2- It had a

S

TE S

technical dimension, since farming and cattle-raising were based on specific cultivated

R

AP LS

plants and domestic animals, involved the use of specific tools and relied on the

development of specific know-how concerning crop rotation, field use, and so on. 3- It

had a social dimension, since it analyzed the work schedule of the group, and the way it

C EO

was intertwined with other social activities (Claval, 1988-b).

The genre de vie approach gave French geography its capacity to enter deeply into the

relations locally woven between human groups and their environments. Because of its

E –

emphasis on techniques, it was conducive to the study of historical sequences in land

H

occupation. Since it was a study of all human activities, it provided a new way to

PL O

conceive social studies (Claval, 1998).

M SC

Jean Brunhes was responsible for the crossbreeding of the French genre de vie analysis

and the German style of landscape studies. He was especially keen on the role of

techniques in the structuring of ways of life; they imprinted cultural marks on

landscapes (Brunhes, 1904; Brunhes and Deffontaines, 1920-1926; Brunhes and

SA NE

Vallaux, 1921). Pierre Deffontaines followed his path (Deffontaines, 1933). In the

1930s and 1940s, he developed a strong school of cultural geography in France: his

main interests were the adaptation of man to harsh environments, and human agency in

U

shaping the landscapes of civilized regions. He developed religious geography

(Deffontaines, 1948).

Pierre Gourou represented another development of the idea of way of life (Gourou,

1973). As Vidal de la Blache, he started from human densities. When they differed

within the same milieu, he considered that cultural factors played a key role: this was a

vidalian theme. For him, however, the techniques upon which genres de vie were built

were both material and social. In this way, he always associated the study of cultures

with a social approach. He was very sensitive to the material and social bases of great

cultures- for instance the Chinese and its derivatives such as the Vietnamese (Gourou,

1936; 1940).

©Encyclopedia of Life Support Systems(EOLSS)

GEOGRAPHY – Vol. II - Cultural and Social Geography - Paul Claval

1.1.3. The Early Forms of Social Geography

The expression “social geography” appeared at the same time as “human geography”,

and for a generation or so it was just an equivalent for it (Dunbar, 1977). It was because

of the genre de vie approach that an interest for social organization developed.

When exploring the foundations of regional specificities, French geographers

discovered, in the early 1900s, that genres de vie did not rely only on technical bases.

They also reflected social conditions. When working on Western Brittany, Camille

Vallaux showed that the local agriculture was linked both with specific ways of

combining tillage and the exploitation of rough pastures, and a hierarchic social

structure which gave landowners a strict control over their farmers (Vallaux, 1907). In

his work on Pays de Caux, Jules Sion went further (Sion, 1908). This plateau was a

wealthy cropland, where cottage industry developed from the sixteenth century: it relied

on the transformation of the flax locally grown, and agricultural surpluses, which

S

TE S

allowed for the existence of a large group of part-time farmers or day’s laborers among

R

AP LS

whom the weavers were recruited. Since the commercialization of linen was highly

profitable, a local bourgeoisie developed. It was responsible for the substitution of

cotton to flax at the end of the eighteenth century, for the harnessing of the local

C EO

streams, the building of small factories and later the use of coal imported from Britain.

Studies such as those of Camille Vallaux or Jules Sion remained exceptional for a long

time. André Cholley tried to systematize this type of approach in rural zones in the early

E –

1930s (Cholley, 1930). In fact, social studies developed mainly in urban areas. In this

H

field, most of them were initiated in the United States by the school of social ecology of

PL O

Chicago, in the 1920s: Park and Burgess had been struck by the diverse social fabric of

the great inland capital of the United States (Burgess, 1924; Park, 1960). Out of the

M SC

Loop and its high-rise buildings, the whole city was made of low houses. Its uniformity

was an illusion: each neighborhood harbored a specific community. When mapped, the

urban area appeared as a set of concentric rings, with a predominance of low-income

recent migrants in the inner area, middle-income blue collars in the second ring, and

SA NE

high-income white collars on the edge.

Further studies showed that the social fabric of Chicago was more complex than this

U

initial model showed. The students of Park and Burgess were the first to stress the fact:

the black population was concentrated in ghettos from which it was unable to escape

(Wirth, 1928). Close to the Loop, there remained a wealthy "Golden Coast", where

high-income groups congregated close to the lake (Zorbaugh, 1929). Other students in

the group stressed the originality of the urban way of life (Wirth, 1938) as opposed to

rural ones (Redfield, 1940). The specificities of peasant and folk populations became a

widely accepted commonplace among sociologists. Concerning the Chicago urban area,

an economist, Homer Hoyt, discovered that the concentric pattern of social distribution

was not the only one: a radial structure was also present. From one sector to the next,

the differences resulted from higher or lower income levels (Hoyt, 1933).

Geographers did not participate in this research orientation until the beginning of the

1940s, when Edward Ullman and Chauncy D. Harris proved that a third pattern of social

distribution existed in the Chicago area: this agglomeration was made of a cluster of

©Encyclopedia of Life Support Systems(EOLSS)

GEOGRAPHY – Vol. II - Cultural and Social Geography - Paul Claval

communities, each with its own ethnic or religious specificities (Harris and Ullman,

1945).

1.2. The Impact of the "New" Geography on Cultural and Social Studies: from the

1950s to the early 1970s

Geography changed deeply in the 1950s and 1960s. It ceased to be considered mainly as

a natural science. It became increasingly a social science. The process was best

exemplified by the emergence of a "new geography" during the 1960s, but the

transformation started earlier and its consequences were still important in the 1970s,

especially at the beginning of the decade.

As long as geographers were natural scientists, they lacked tools for dealing with

cultural and social facts. Thanks to the new epistemological turn, they could rely on

ideas developed either by sociologists, anthropologists or economists. Since the

S

TE S

majority of them accepted the neo-positivist conception of scientific enquiry, they

R

AP LS

remained, however, more interested into the observable dimension of social and cultural

data, or the analysis of rational behavior, than into their lived dimension.

C EO

1.2.1. The Time of Social Ecologies

The Chicago school of Urban studies had been mainly centered on sociology and

secondarily on anthropology. With the discovery of the complexity of social patterns in

E –

urban areas, problems of methodology became increasingly important. What was the

H

most significant, the ring structure of Park and Burgess, the sector organization of Hoyt

PL O

or the kaleidoscope of Ullman and Harris?

M SC

Psychologists had to confront the same type of problem when interpreting the tests they

had built in order to measure intelligence. The majority of the data collected were

redundant. They reflected the variations of a few factors, among which the factor G

(intelligence) was evidently the most significant. In order to evaluate its influence,

SA NE

psychologists and statisticians developed the techniques of factorial analysis.

Sociologists chose to rely on factorial analysis to map social areas (Shevky and Bell,

1955; Anderson and Egeland 1961).

U

It was a time when Chicago geographers became increasingly present in urban studies.

Thanks to Brian J. L. Berry, they shifted from the study of central places at the level of

urban networks to intra-urban networks of central places (Berry, 1964). By the end of

the 1960s, they decided to use computing facilities to speed up the factorial analysis of

social groupings within urban areas (Berry and Rees, 1969; Berry and Horton, 1970). It

allowed them to show that each of the three models developed in the 1930s and 1940s

explained a part of reality (Murdie, 1969): the concentric model was linked with the

structure of families and the presence or absence of children; the sector model resulted

from a biased knowledge of urban organization, that was conducive to the choice of a

location on the same radial axis when people decided to move to a new house; the

mosaic model expressed the strength of cultural and social proximity networks within

ethnic or religious communities (Berry, 1971; Berry and Smith, 1972).

©Encyclopedia of Life Support Systems(EOLSS)

GEOGRAPHY – Vol. II - Cultural and Social Geography - Paul Claval

According to cities and countries, the weight of factors changed. The social geography

of cities was conducive to some general findings, but also to the idea that, depending on

countries and cultures, some diversity in the patterns of social distribution existed.

This form of social geography was certainly interesting, but it presented evident

weaknesses. It relied exclusively on census data. It described the social geography of

the city when people where at home, at night, but ignored what happened during the

day.

1.2.2. The Social Geography of Rural Areas

During the 1960s, social geography was mainly developed to picture urban and

industrial areas. The interest in rural social structures, which was evident among many

French geographers at the beginning of the twentieth century, had disappeared. The

transformation of rural areas was very rapid. Spheres of relations changed scale: social

S

TE S

life ceased to be mainly local.

R

AP LS

The analytical tools for this type of situation were provided by anthropologists: Robert

Redford had been fascinated, since the early 1940s, by the folk societies he met in rural

C EO

Mexico (Redfield, 1940; 1947; 1956). Their members did not behave in the same way

than the farmers of the American Middle West. The market was for them a nearby

locality where prices varied normally within limits set up by customs. Their main

problem was to reduce the social impact of the instability encapsulated into their

E –

production system.

H

PL O

The specificities of the folk societies of Mexico were similar to those of peasant

societies all over the world. The acceleration of modernization was ruining this form of

M SC

social organization. During the 1960s and the 1970s, the final stage of Western

peasantries became one of the central themes for sociologists (in France: Mendras,

1970), historians (Weber, 1983) and geographers (Franklin, 1969).

SA NE

Rural areas did not disappear, but their societies took new forms. Many research

projects were consequently devoted to the exploration of social life in areas where

farming had often ceased to be the dominant activity. There, the generalization of car

U

ownership and telephone equipment offered new possibilities of access to forms of

sociability until then reserved to urban areas: hence the proliferation of studies on

suburban areas, rurban areas, the urbanized countryside, and on the impact of leisure

and tourism on these areas (Berry, 1976). In Germany, Hartke used the spread of fallow

land as an indicator of the sociological urbanization of rural areas (Hartke, 1956).

1.2.3. Relevance and the Growing Success of Marxist Social Analysis

Geographers grew increasingly uncomfortable with the publications the new geography

produced. Their studies were based on a functional approach. They explained how

society worked, but did not offer critical perspectives on what was wrong in our world.

The existence of social inequalities appeared increasingly as a moral scandal. The

spatial distribution of social groups began to be systematically interpreted in terms of

unequal power between classes and domination of the strongest over the weakest, that

©Encyclopedia of Life Support Systems(EOLSS)

GEOGRAPHY – Vol. II - Cultural and Social Geography - Paul Claval

is, along a Marxist perspective (Harvey, 1973).

Between 1968 and 1972, social studies became one of the most popular frontiers of

geographical research. Thanks to William Bunge, new ways of analyzing segregations

appeared, as exemplified by his study of Fitzgerald, one of the worst black ghettos in

Detroit (Bunge, 1971).

During the 1960s and early 1970s, the scope of social geography had become much

wider. However, some of its limitations remained: it relied heavily on the data provided

by the censuses; it was more interested in social distributions at night than in their

daylight equivalents; it was more focused on social hierarchies than on social life and

processes.

-

-

S

TE S

-

R

AP LS

TO ACCESS ALL THE 21 PAGES OF THIS CHAPTER,

C EO

Visit: http://www.eolss.net/Eolss-sampleAllChapter.aspx

Bibliography

E –

Berque, Augustin, 1990, Médiance. De milieux en paysages, Montpellier, Reclus. [Man/milieu

H

relationship in a phenomenological perspective]

PL O

Berque, Augustin, 1995, Les Raisons du paysage, de la Chine antique aux environnements de synthèse,

Paris, Hazan. [Art and landscape as human creation]

M SC

Berque, Augustin, 2000, Ecoumène. Introduction à l'étude des milieux humains, Paris, Belin. [The

foundations of the idea of human milieux]

Berry, Brian, J. L., 1964, "Cities as systems within systems of cities", Papers of the Regional Science

SA NE

Association, vol. 13, p. 147-164. [The first study of cities analyzed as systems]

Berry, Brian J. L. (ed.), 1971, "Comparative factorial ecology", Economic Geography, vol. 47, p. 209-

367. [The use of factorial analysis in urban studies]

U

Berry, Brian J. L., 1976, Urbanization and Counterurbanization, Beverly Hills, Sage Publications. [Was

there a fundamental break in the trend towards urbanization ?]

Berry, Brian J. L., Horton, Frank E., 1970, Geographic Perspectives on Urban Systems, Englewood

Cliffs, Prentice-Hall. [A useful synthesis of the “New Geography” approach to urban studies]

Berry, Brian J. L., Rees, Philip, 1969, "The factorial ecology of Calcutta", American Journal of

Sociology, vol. 74, p. 445-491. [The first factorial ecology of a non-Western city]

Berry, Brian J. L., Smith, Katherine S. (eds.), 1972, City Classification Handbook: Methods and

Applications, New York, John Wiley. [Factorial ecology as a tool for urban classification]

Bonnemaison, Joël, 1981, "Voyage autour du territoire", L'Espace géographique, vol. 10, n° 4, p. 119-

125. [How to combine geographical and ethnological approaches to understand territory?]

Bonnemaison, Joël, 1992, "Le territoire enchanté: croyance et territorialités en Mélanésie", Géographie et

Cultures, vol. 1, n° 3, p. 71-89. [Ten years of research on territory]

©Encyclopedia of Life Support Systems(EOLSS)

GEOGRAPHY – Vol. II - Cultural and Social Geography - Paul Claval

Brunhes, Jean, 1902, L'Irrigation. Ses conditions géographiques, ses modes et son organisation dans la

Péninsule ibérique et dans l'Afrique du Nord, Paris, Masson. [Law as a cultural factor]

Brunhes, Jean, Deffontaines, Pierre, 1920-1926, Géographie humaine de la France, Paris, Plon, 2 vol.

[An early cultural perspective on France]

Brunhes, Jean, Vallaux, Camille, 1921, Géographie de l'histoire, Paris, Alcan. [Geography, history and

culture]

Bunge, William, 1971, Fitzgerald. Geography of a Revolution, Cambridge (Mas.), Schenkman. [The first

radical monograph on a ghetto]

Burgess, Ernest W., 1924, "The growth of a city. An introduction to a research project", Publications of

the American Sociological Society, vol. 18, p. 85-97. [American sociology discovers the first model of

the city]

Cholley, André, 1931, "Essai d'une carte de représentation de l'habitat rural", Congrès International de

Géographie de Paris, Paris, A. Colin, p. 122-123. [The social dimension in cartography]

Claval, Paul, 1973, Principes de géographie sociale, Paris, M.-Th. Genin. [The first French synthesis on

S

TE S

social geography]

Claval, Paul, 1978, Espace et pouvoir, Paris, PUF; [A Weberian approach to political geography]

R

AP LS

Claval, Paul, 1980, Les Mythes fondateurs des sciences sociales, Paris, PUF. [A critique of the

epistemological foundations of social sciences]

C EO

Claval, Paul, 1988-a, "Les géographes français et le monde méditerranéen", Annales de Géographie, vol.

97, n° 542, p. 385-403. [How French geographers developed their intellectual tools]

Claval, Paul, 1988-b, "Les trois niveaux d'analyse des genres de vie", in: G. Bahrenberg et alia (eds.),

Geographie des Menschen. Dietrich Bartels zur Gedanken, Bremen, Bremer Beitrage zur Geographie

und Raumplannung, Heft 11, p. 73-85. [The ecological, social and cultural dimensions of the “genre de

E –

vie”]

H

Claval, Paul, 1995-a, "L'analyse des paysages", Géographie et Cultures, vol. 4, n° 13, p. 55-74. [A

PL O

review of geographers on landscape]

M SC

Claval, Paul, 1995-b, La Géographie culturelle, Paris, Nathan. [The cultural approach in the mid 90s]

Claval, Paul, 1998, Histoire de la Géographie française de 1870 à nos jours, Paris, Nathan. [Social,

cultural, political and landscape curiosities in French geography]

SA NE

Claval, Paul, 1999, "Qu'apporte l'approche culturelle à la géographie", Géographie et cultures, vol. 8, p.

n° 31, p. 5-24. [The cultural approach as responsible for the cultural turn]

Claval, Paul, 2001-a, "The geographical study of myth", Norwegian Journal of Geography, vol. 55, n° 3,

p. 138-151. [How to analyse in a geographic way myths, religions and ideologies]

U

Claval, Paul, 2001-b, "The cultural approach and geography - the perspective of communication",

Norwegian Journal of Geography, vol. 55, n° 3, p. 126-137. [The cultural approach and communication]

Claval, Paul, 2001-c, Epistémologie de la géographie, Paris, Nathan. [The naturalist, neo-positivist and

postmodern conceptions fo geography]

Coates, B. E., Johnston, R. J., Knox, P. L., 1977, Geography and Inequality, London, Oxford University

Press. [A good example of the emerging care for injustice in social geography]

Cosgrove, Denis, 1984, Social Formation and the Symbolic Landscape, London, Croom Helm. [A critical

view over the landscape approach]

Dardel, Eric, 1952, L'Homme et la Terre, Paris, PUF. [How geography discoverdd phenomenology]

Deffontaines, Pierre, 1933, L'Homme et la forêt, Paris, Gallimard. [An example of the cultural approach

in the 30s]

Deffontaines, Pierre, 1948, Géographie et religions, Paris, Gallimard. [The achievements and difficulties

of the cultural approach in the 40s]

©Encyclopedia of Life Support Systems(EOLSS)

GEOGRAPHY – Vol. II - Cultural and Social Geography - Paul Claval

Di Meo, 1991, L'Homme, la société, l'espace, Paris, Anthropos. [A structurationnist interpretation of

social geography]

Driver, Felix, 1985, "Power, space and the body: a critical assessment of Foucault's Discipline and

Punish", Environement and Plannning D: Society and Space, vol. 3, p. 425-446. [Foucault’s impact on

geography]

Driver, Felix, 1988, "Moral geographies, social sciences and the urban environment in mid-nineteenth

century England", Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers, vol. 13, p. 275-287. [How to

build a more critical social geography ?]

Dunbar, G. S., 1977, "Some early occurences of the term 'social geography'", Scottish Geographical

Magazine, Vol. 93, n° 1, p. 15-20. [Social geography as an early synonym of human geography]

Duncan, James S., 1980, "The superorganic in American cultural geography », Annals of the Association

of American Geographers, vol. 70, p. 181-198. [A fierce criticism of Sauer’s tradition]

Duncan, James S., 1990, The City as Text: the Politics of Landscape Interpretation in the Kandyan

Kingdom, Cambridge, Cambridge University Press. [The irruption of linguistics in geography]

S

TE S

Franklin, Harvey, 1969, The European Peasantry. The Final Stage, London, Methuen. [Peasantry as an

historical category]

R

AP LS

Frémont, A., Chevalier, J., Hérin, R., Renard, J., 1983, Géographie sociale, Paris, Masson. [A classical

presentation of French social geography]

Giddens, Anthony, 1981, A Contemporary Critique of Historical Materialism, Londres, Macmillan.

C EO

[How to free marxism from its chains ?]

Giddens, Anthony, 1984, The Constitution of Society. Outline of the Theory of Structuration,

Basingstoke, Polity Press. [Sociology discovers space]

Gourou, Pierre, 1936, Les Paysans du delta tonkinois. Etude de géographie humaine, Paris, Editions

E –

d'Art et d'Histoire. [Culture and social organization as fundamental geographical factors]

H

Gourou, Pierre, 1940, La Terre et l'homme en Extrême-Orient, Paris, A. Colin. [The cultural and social

PL O

bases of the Chinese civilization]

M SC

Gourou, Pierre, 1973, Pour une Géographie humaine, Paris, Flammarion. [Gourou’s ideas about human

geography]

Gregory, Derek, 1994, Geographical Imaginations, Oxford, Blackwell. [A postmodern view of

geography]

SA NE

Hägerstrand, Torstein, 1970, "What about people in regional science?" Papers of the Regional Science

Association, vol. 24, p. 7-21. [To start from the individual !]

Hahn, Eduard, 1896, Die Haustiere und ihre Beziehungen zur Wirtschaft des Menschen, Leipzig,

U

Duncker and Humblot. [Domestication as a fundamental cultural geography]

Hahn, Eduard, 1909, Die Entstehung der Pflug-Kultur, Heidelberg, Carl Winter. [The genesis of

agricultural techniques in the Middle East]

Hahn, Eduard, 1914, Von der Hacke zum Pfluge, Leipzig, Quelle and Meyer. [The dichotomy between

two types of farminng activities]

Harries, K. D., 1974, The Geography of Crime and Justice, New York, McGraw-Hill. [A social

geography of unrest and deviant behaviors]

Harris, C. D., Ullman, E., 1945, "The nature of cities", Annals of the American Academy of Political and

Social Sciences, vol. 242, p. 7-17. [The third model of the American city]

Hartke, Wolfgang, 1956, "Die 'Soziabrache' als Phänomenon der geographischen Differenzierung der

Landschaft", Erdkunde, vol. 10, n° 4, p. 257-269. [German geography introduces a social dimension in

the study of cultural landscapes]

©Encyclopedia of Life Support Systems(EOLSS)

GEOGRAPHY – Vol. II - Cultural and Social Geography - Paul Claval

.Harvey, David, 1973, Social Justice and the City, London, Arnold. [The irruption of a critical

perspective in geography]

Hoyt, Homer, 1933, One Hundred Years of Land Values in Chicago, Chicago, Chicago University Press.

[The second model of the American city]

Jackson, John B., 1984, Discovering the Vernacular Landscape, New Haven, Yale University Press. [A

democratic view of landscape geography]

Jones, Emrys, Eyle, John, 1977, An Introduction to Social Geography, London, Oxford University Press.

[A classical view of British social geography]

Leighly, John (ed.), 1963, Land and Life: a Selection from the Writings of Carl Ortwin Sauer, Berkely,

University of California Press. [The essentials of Sauer]

Le Roy Ladurie, Emmanuel, 1975, Montaillou, village occitan. De 1294 à 1324, Paris, Gallimard. [From

mega- to micro-approaches in the social sciences]

Lewis, Martin W., Wigen, Kären E., 1997, The Myths of Continents: a Critique of Metageography,

Berkeley and Los Angeles, University of California Press. [How geography is built with words]

S

TE S

Mann, Michael, 1986, The Sources of Social Power. Tome 1, A History of Power from the Beginning to

A. D. 1760, Cambridge, Cambridge University Press. [A combined social, cultural and political approach

R

AP LS

to history]

Meitzen, August, Siedelung und Agrarwesen der Westgermanen und Ostgermanen, der Kelten, Römer,

Finnen und Slawen, Berlin, Hertz, 4 vol. [German geography relates ethnicity and rural landscapes]

C EO

Mendras, Henry, 1967, La Fin des paysans, Paris, SEDEIS. [A view on the historicity of peasantry]

Murdie, Robert A., 1969, Factorial Ecology of Metropolitan Toronto, 1951-1961. An Essay on the Social

Geography of the City, Chicago, Department of Geography, University of Chicago, Research Paper n°

116. [The best example of factorial analysis used in a temporal perspective]

E –

H

Olwig, Kenneth R., 1996, "Recovering the substantial nature of landscape", Annals of the Association of

American Geographers, vol. 86, p. 630-653. [Landscape and local community: origins – and future ?]

PL O

Olwig, Kenneth R., 2001, "Landscape as a contested topic of place, community and self", in: Adams,

M SC

Paul et al. (eds.), Textures of Place: Geographies of Imagination, Experience, and Paradox, Minneapolis,

University of Minnesota Press, p. 95-119. [Variations on the theme of landscape and community]

Park, Robert E., 1960, Human Communities. The City and Human Ecology, Glencoe, The Free Press.

[The essentials of Park]

SA NE

Peet, R., 1975, "The Geography of Crime: a Political Critique", Professional Geographer, vol. 27, p.

277-280. [Introducing disorder and the subversion of the society in social geography]

Philo, Chris, 1992, "Foucault's geography", Environment and Planning D: Society and Space, vol. 10, p

U

137-161. [Sight, power and control]

Pitte, Jean-Robert, 1991, Gastronomie française. Histoire et géographie d'une passion, Paris, Fayard.

[How to introduce the body as a geographic theme through the analysis of senses]

Planhol, Xavier de, 1979, "Forces économiques et composantes culturelles dans les structures

commerciales des villes islamiques", L'Espace géographique, vol. 8, n° 4, p. 315-322. [A critical view of

the cultural geography of Moslem cities]

Planhol, Xavier de, 1984, "La cour, la place, le parvis: éléments pour une morphologie sociale comparée

des villes islamiques et ouest-européennes", in: Paul Claval (ed.), Géographie historique des villes de

l'Europe occidentale, Paris, Publications du Département de Géographie de l'Université de Paris-

Sorbonne, n° 12, vol. 1. [The social and cultural significance of morphological urban features]

Ratzel, Friedrich, 1882-1891, Anthropogeographie oder Grundzüge der Anwendung der Erdkunde auf

die Geschichte, Stuttgart, Engelhorn, 2 vol. [How human geography was based on a cultural perspective]

Redfield, Robert, 1940, "The Folk society and culture", American Journal of Sociology, vol. 45, p. 731-

742. [The links between culture and social forms]

©Encyclopedia of Life Support Systems(EOLSS)

GEOGRAPHY – Vol. II - Cultural and Social Geography - Paul Claval

Redfield, Robert, 1947, "The Folk Society", American Journal of Sociology, vol. 52, p. 293-308. [The

peasant societies of Latin America as examples of social and cultural formations]

Redfield, Robert, 1956, Peasant Society and Culture, Chicago, Chicago University Press. [From the idea

of folk society to a reflection on peasantry]

Relph, Edward, 1970, "An enquiry on the relations between geography and phenomenology", Canadian

Geographer, vol. 14, p. 193-201. [A rediscovery of Dardel and of phenomenology]

Richardson, M., 1981, "On the ‘superorganic in American cultural geography’. Commentary of Duncan’s

paper", Annals of the Association of American Geographers, vol. 71, p. 284-287. [A commentary of

Duncan’s critical views on American cultural geography which was also a methodological program]

Roger, Alain, 1997, Court Traité du paysage, Paris, Gallimard. [Philosophy and landscape]

Said, Edward, 1978, Orientalism, New York, Vintage. [How the post-colonial perspective was born]

Sauer, C. O., 1925, "The morphology of landscape", University of California Publications in Geography,

vol. 2, p. 19-53. [The founding text of American cultural geography]

Sauer, C. O., 1938, "Theme of plant and animal destruction in economic history", Journal of Farm

S

TE S

Economics, vol. 20, 765-775. [The role of life in cultural geography]

R

AP LS

Sauer, C. O., 1941, "The Personality of Mexico", American Geographical Review, vol. 31, p. 353-364.

[Culture, it is also the personality of countries]

Sauer, C. O., 1952, Agricultural Origins and Dispersals, New York, American Geographical Society. [A

C EO

review of one of the founding themes of cultural geography]

Sautter, Gilles, 1979, "Le paysage comme connivence", Hérodote, n° 16, 1979, p. 40-67. [From a

functionalist to a subjective perspective in landscape analysis]

Schlüter, Otto, 1899, "Bermerkungen zur Siedelungsgeographie", Geographisch Zeitschrift, vol. 5, p. 65-

E –

84. [The origins of German studies on the cultural landscape]

H

Shevky, W, Bell, E., 1955, Social Area Analysis: Theory, Illustrative Application and Computational

PL O

Procedures, Stanford, Stanford University Press. [The link between the Chicago School of Urban

sociology of the 20s and 30s and the Chicago school of urban geography of the 60s]

M SC

Sion, Jules, 1908, Les Paysans de Normandie orientale, Paris, A. Colin. [How to explain history and

forms of settlements through an analysis of social evolution]

Smith, David M., 1973, The Geography of Social Well-being in the United States, New York, McGraw-

SA NE

Hill. [Another dimension of social analysis in the 70s]

Smith, David M., 1977, Human Geography. A Welfare Approach, London, Arnold. [The theoretical

foundations of the welfare approach in social geograph ]

U

Trochet, Jean-René, 1998, Géographie historique. Hommes et territoires dans les sociétés traditionnelles,

Paris, Nathan. [The past relations between territorial control and social structures]

Vallaux, Camille, 1907, La Basse-Bretagne. Etude de géographie humaine, Paris, A. Colin. [How

geography reflects the particularities of law and land tenure]

Vidal de la Blache, Paul, 1902, "Les conditions géographiques des faits sociaux", Annales de

Géographie, vol. 11, p. 13-23. [The foundations of French human geography]

Vidal de la Blache, Paul, 1903, Tableau de la géographie de la France, Paris, Hachette. [The foundations

of French regional approach]

Vidal de la Blache, Paul, 1911, "Les genres de vie dans la géographie humaine", Annales de Géographie,

vol. 20, n° 111, p. 193-212; n° 112, p. 289-304. [The fundamental article on the notion of genre de vie]

Weber; Eugen, 1983, La Fin des terroirs. La modernisation de la France rurale, Paris, Fayard. [The

oddness of peasantry and its disappearance in the contemporary world]

©Encyclopedia of Life Support Systems(EOLSS)

GEOGRAPHY – Vol. II - Cultural and Social Geography - Paul Claval

Weber, Max, 1905, Die protestantische Ethik und die Geist der Kapitalismus; éd. française, 1963,

L’Ethique protestante et l’esprit du capitalisme, Paris, Plon. [The fundamental text on the relations

between culture and social forms]

Werlen, Benno, 1988, Gesellschaft, Handlung und Raum, Stuttgart, Franz Steiner. [A refoundation of

human geography based on the more recent development in phenomenology and social reflection]

Wirth, Eugen, 1974, "Zum Problem des Bazars (sùq, çarsi)", Der Islam, p. 203-260; 1975, p. 6-46. [A

critical view on the cultural geography of Moslem city]

Wirth,Eugen, 1993, "Esquisse d'une conception de la ville islamique", Géographie et Cultures, vol. 2, n°

5, p. 71-90. [idem]

Wirth, Louis, 1928, The Ghetto, Chicago, Chicago University Press. [Social scientists discover the worst

aspects of social distributions]

Wirth, Louis, 1938, "Urbanism as a way of life", American Journal of Sociology, vol. 44, p. 1-24. [How

morphology explains social and cultural differentiation]

Zorbaugh, H.W; 1929, The Gold Coast and the Slum, Chicago, Chicago University Press. [How cities are

S

TE S

divided into poor and wealthy neighborhoods]

R

AP LS

Biographical Sketch

Born in 1932, Paul Claval graduated from the University of Toulouse and taught in the Universities of

C EO

Besançon and Paris-Sorbonne. His main interest was on the history and epistemology of geography, and

its relations with other social sciences: he focused on geography and economics in the 1960s, geography,

sociology and political sciences between 1970 and 1985, and geography and anthropology since 1985.

His most recent book is on L'épistémologie de la géographie.

E –

H

PL O

M SC

SA NE

U

©Encyclopedia of Life Support Systems(EOLSS)

You might also like

- Symbols in ActionDocument24 pagesSymbols in ActionMarcony Lopes Alves50% (2)

- DLP DIASS Week A - Applied Social SciencesDocument5 pagesDLP DIASS Week A - Applied Social SciencesMALOU ELEVERANo ratings yet

- Hbef1103 - Educational Sociology and Philosophy 1Document237 pagesHbef1103 - Educational Sociology and Philosophy 1Marliel Paguiligan CastillejosNo ratings yet

- DLL FORMAT APPLIED ECONOMICS 1 Week TRUEDocument4 pagesDLL FORMAT APPLIED ECONOMICS 1 Week TRUEmichelle garbin100% (6)

- Trends and Issues in Social Studies/Social ScienceDocument5 pagesTrends and Issues in Social Studies/Social ScienceMichele100% (7)

- Fundamentals of Human GeographyDocument120 pagesFundamentals of Human Geographyhussain200055100% (1)

- Unesco - Eolss Sample Chapters: Population GeographyDocument9 pagesUnesco - Eolss Sample Chapters: Population GeographySyed Fawad Ali ShahNo ratings yet

- Population Geography As A Field of StudyDocument17 pagesPopulation Geography As A Field of StudyNafiu Zakari FaggeNo ratings yet

- Gep 424 Social and Cultural Geo CourseDocument20 pagesGep 424 Social and Cultural Geo Courseangenina739No ratings yet

- Schools of ThoughtDocument8 pagesSchools of Thoughtkinyi200275% (8)

- Fundamentals of Human Geography - Chapter 1Document9 pagesFundamentals of Human Geography - Chapter 1AHMAD HABIBI0% (1)

- ABM201-Dela Cruz - Grace-ARG1Document12 pagesABM201-Dela Cruz - Grace-ARG1joshuamacinasdeleonNo ratings yet

- Annales School Matter ForDocument8 pagesAnnales School Matter ForAvantik KushaNo ratings yet

- The Diversion of CultureDocument10 pagesThe Diversion of CultureJulio FerreiraNo ratings yet

- Human Geography - WikipediaDocument7 pagesHuman Geography - WikipediaJai NairNo ratings yet

- Evolution of Social GeographyDocument4 pagesEvolution of Social Geographysoumi mitraNo ratings yet

- The Historical Dimension of French Geography: Paul ClavalDocument17 pagesThe Historical Dimension of French Geography: Paul ClavalAnonymous YDyX1TrM2No ratings yet

- 2009 - Ian Hodder - Symbols in Action - EthnoarchaeoIogicaI Studies of Material CultureDocument25 pages2009 - Ian Hodder - Symbols in Action - EthnoarchaeoIogicaI Studies of Material CultureByron Vega BaquerizoNo ratings yet

- Approaches To HistoryDocument90 pagesApproaches To Historysanazh100% (2)

- Human GeographyDocument55 pagesHuman GeographyPranav VatsNo ratings yet

- French Geographers: Phillippe Buache (1752)Document7 pagesFrench Geographers: Phillippe Buache (1752)Asna JaferyNo ratings yet

- Viveiros de Castro - Images of Nature and Society in Amazonian EthnologyDocument22 pagesViveiros de Castro - Images of Nature and Society in Amazonian EthnologyMark WeaveNo ratings yet

- Definition For Cultural GeographyDocument2 pagesDefinition For Cultural GeographylovejaneNo ratings yet

- 2 - Tomaney - IEHG - RegionDocument15 pages2 - Tomaney - IEHG - RegionMelisa AngelinaNo ratings yet

- Understanding Historical GeographyDocument6 pagesUnderstanding Historical GeographyPenis BobNo ratings yet

- Reading 6 Human EcologyDocument6 pagesReading 6 Human EcologyRhemaNo ratings yet

- Kemper-Rollwagen - Urban - Anthropology - Encyclopedia - of - Cultural Anthropology PDFDocument10 pagesKemper-Rollwagen - Urban - Anthropology - Encyclopedia - of - Cultural Anthropology PDFM PNo ratings yet

- V. Gordon Childe and The Urban Revolution: A Historical Perspective On A Revolution in Urban StudiesDocument29 pagesV. Gordon Childe and The Urban Revolution: A Historical Perspective On A Revolution in Urban StudiesMichael SchomackerNo ratings yet

- Untitled DocumentDocument1 pageUntitled DocumentVikas BabbarNo ratings yet

- Untitled DocumentDocument1 pageUntitled DocumentVikas BabbarNo ratings yet

- African History and Environmental HistoryDocument34 pagesAfrican History and Environmental HistoryPearl Irene Joy NiLoNo ratings yet

- Social Anthropology Is The Dominant Constituent of Anthropology Throughout The United Kingdom and Commonwealth and Much of EuropeDocument9 pagesSocial Anthropology Is The Dominant Constituent of Anthropology Throughout The United Kingdom and Commonwealth and Much of EuropesnehaoctNo ratings yet

- Human GeographyDocument2 pagesHuman GeographyMariana EneNo ratings yet

- L'homme Et La Destruction Des Ressources Naturelles: La Raubwirtschaft Au Tournant Du SiècleDocument23 pagesL'homme Et La Destruction Des Ressources Naturelles: La Raubwirtschaft Au Tournant Du SiècleTayla.No ratings yet

- Community Conflicts.Document5 pagesCommunity Conflicts.Neha ChawlaNo ratings yet

- Unesco - Eolss Sample Chapters: Local Cultures and Global DynamicsDocument4 pagesUnesco - Eolss Sample Chapters: Local Cultures and Global DynamicsKurt ReyesNo ratings yet

- Evirment Policies of British IndiaDocument11 pagesEvirment Policies of British IndiaShivansh PamnaniNo ratings yet

- Abay, E., & Çevik, Ö. (2005) - "Interaction and Migration" Issues in Archaeological Theory. Altorientalische Forschungen, 32 (1) .Document12 pagesAbay, E., & Çevik, Ö. (2005) - "Interaction and Migration" Issues in Archaeological Theory. Altorientalische Forschungen, 32 (1) .bugratesNo ratings yet

- Annales DDocument5 pagesAnnales DJuanito TevesNo ratings yet

- Paul Claval Regional GeographyDocument21 pagesPaul Claval Regional GeographyAsier ArtolaNo ratings yet

- An Investigation of Historical GeographyDocument5 pagesAn Investigation of Historical GeographyNikos MarkoutsasNo ratings yet

- Pluciennik 2001Document18 pagesPluciennik 2001Antonia CáceresNo ratings yet

- Approach Types of HistoryDocument18 pagesApproach Types of HistoryAhmad Khalilul Hameedy NordinNo ratings yet

- Contemporary ArtDocument8 pagesContemporary Artrosemarie docogNo ratings yet

- Human Geography: Definition, Scope and Principles Contemporary RelevanceDocument9 pagesHuman Geography: Definition, Scope and Principles Contemporary RelevanceSN JHA100% (2)

- Hunt New Cultural History IntroDocument12 pagesHunt New Cultural History IntroIvanFrancechyNo ratings yet

- Unesco - Eolss Sample Chapters: Main Stages of Development of GeographyDocument10 pagesUnesco - Eolss Sample Chapters: Main Stages of Development of GeographySifat ullah shah pakhtoonNo ratings yet

- Chris Hann The - Theft - of - AnthropologyDocument22 pagesChris Hann The - Theft - of - AnthropologyFlorentaNo ratings yet

- Historical and Anthropological Archaeology: Forging AlliancesDocument37 pagesHistorical and Anthropological Archaeology: Forging AlliancesAsbelNo ratings yet

- Human Geography PDFDocument23 pagesHuman Geography PDFRoseMarie Masongsong100% (1)

- Gill Valentine - Whatever Happened To The Social. Reflections On The 'Cultural Turn' in British Human GeographyDocument7 pagesGill Valentine - Whatever Happened To The Social. Reflections On The 'Cultural Turn' in British Human GeographyTrf BergmanNo ratings yet

- Geography of Bengal - Conceptual IssuesDocument5 pagesGeography of Bengal - Conceptual IssuesUrbana RaquibNo ratings yet

- Geography Fact Sheet Chapter 5&6Document5 pagesGeography Fact Sheet Chapter 5&6Ma Ronielyn Umantod MayolNo ratings yet

- The Origin of Social GeographyDocument2 pagesThe Origin of Social GeographyJintu moni BhuyanNo ratings yet

- The Theoretical Foundations of Environmental HistoryDocument21 pagesThe Theoretical Foundations of Environmental HistoryMoisés Quiroz MendozaNo ratings yet

- Evolution of RegionDocument2 pagesEvolution of RegiondasnavneepNo ratings yet

- Adelaida Reyes SchrammDocument18 pagesAdelaida Reyes SchrammDialy MussoNo ratings yet

- Assingment-1 Conservation, Science and Technology, 1800 To 2000Document19 pagesAssingment-1 Conservation, Science and Technology, 1800 To 2000Allana MierNo ratings yet

- The Archaeology of Native American-European Culture Contact: Perspectives from Historical ArchaeologyFrom EverandThe Archaeology of Native American-European Culture Contact: Perspectives from Historical ArchaeologyNo ratings yet

- How About Demons?: Possession and Exorcism in the Modern WorldFrom EverandHow About Demons?: Possession and Exorcism in the Modern WorldRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (6)

- Prehistoric Man: Researches into the Origin of Civilization in the Old and the New WorldFrom EverandPrehistoric Man: Researches into the Origin of Civilization in the Old and the New WorldNo ratings yet

- The Concept of The Cultural Region and The Importance of Coincidence Between Administrative and Cultural RegionsDocument6 pagesThe Concept of The Cultural Region and The Importance of Coincidence Between Administrative and Cultural Regionssoumi mitraNo ratings yet

- Quiz FlyerDocument1 pageQuiz Flyersoumi mitraNo ratings yet

- 0204 Part A DCHB Kullu PDFDocument362 pages0204 Part A DCHB Kullu PDFsoumi mitraNo ratings yet

- Which Place in India Bhagirathi Merges With Alaknanda River To Formed River Ganga? A. B. C. DDocument2 pagesWhich Place in India Bhagirathi Merges With Alaknanda River To Formed River Ganga? A. B. C. Dsoumi mitraNo ratings yet

- Characterization and Evolution of Primary and Secondary Laterites in Northwestern Bengal Basin, West Bengal, India PDFDocument28 pagesCharacterization and Evolution of Primary and Secondary Laterites in Northwestern Bengal Basin, West Bengal, India PDFsoumi mitraNo ratings yet

- 3.2. Ecology and Environment of Mangrove Ecosystems: Prof. K. KathiresanDocument15 pages3.2. Ecology and Environment of Mangrove Ecosystems: Prof. K. Kathiresansoumi mitraNo ratings yet

- Channel Processes: River Stability ConceptsDocument2 pagesChannel Processes: River Stability Conceptssoumi mitraNo ratings yet

- Very Short Type QuestionsDocument1 pageVery Short Type Questionssoumi mitraNo ratings yet

- The Soil Profile: Four Soil Forming ProcessesDocument2 pagesThe Soil Profile: Four Soil Forming Processessoumi mitraNo ratings yet

- All About A BANK CARD: Debit CardsDocument20 pagesAll About A BANK CARD: Debit Cardssoumi mitraNo ratings yet

- NSP Learning21stCentury GollobDocument3 pagesNSP Learning21stCentury Gollobsoumi mitraNo ratings yet

- DSHB S24PGS 2009Document105 pagesDSHB S24PGS 2009soumi mitraNo ratings yet

- Conceptual Framework of Social Well-Being: Chapter-3Document19 pagesConceptual Framework of Social Well-Being: Chapter-3soumi mitraNo ratings yet

- Refer Slide Time: 00:21Document41 pagesRefer Slide Time: 00:21soumi mitraNo ratings yet

- Module-In-Humss 224 (Chapters 1-12)Document112 pagesModule-In-Humss 224 (Chapters 1-12)Ma'am Digs VlogNo ratings yet

- Academic Disciplines and School SubjectsDocument5 pagesAcademic Disciplines and School SubjectsAngelica Faye LitonjuaNo ratings yet

- Educating Lawyers For A Changing WorldDocument1 pageEducating Lawyers For A Changing WorldAbhiNo ratings yet

- Advantages of Civilization Approach To Studying The Development of SocietyDocument3 pagesAdvantages of Civilization Approach To Studying The Development of SocietyresearchparksNo ratings yet

- Bolman and Deal FrameDocument1 pageBolman and Deal Frameapi-393900181No ratings yet

- English For Speci Fic Purposes: Maria-Lluïsa Gea-Valor, Jesús Rey-Rocha, Ana I. MorenoDocument13 pagesEnglish For Speci Fic Purposes: Maria-Lluïsa Gea-Valor, Jesús Rey-Rocha, Ana I. Morenoannavolkova79No ratings yet

- Sourcesof Academic Stressamong Higher Secondary SchoolDocument6 pagesSourcesof Academic Stressamong Higher Secondary SchoolWan ArifuddinNo ratings yet

- ANTH 320 - Qualitative Research Methods - Ali KhanDocument10 pagesANTH 320 - Qualitative Research Methods - Ali KhanMuhammad Irfan RiazNo ratings yet

- Generic Structure and Rhetorical Moves in English-Language Empirical Law ResearchDocument14 pagesGeneric Structure and Rhetorical Moves in English-Language Empirical Law ResearchRegina CahyaniNo ratings yet

- Comparative Politics OutlineDocument13 pagesComparative Politics OutlineMuhammad Nadeem MirzaNo ratings yet

- Erasmus Oferta Na 2023 - 24Document20 pagesErasmus Oferta Na 2023 - 24mihalina1123No ratings yet

- DISS ANSWER SHEETsDocument9 pagesDISS ANSWER SHEETsMa rosario JaictinNo ratings yet

- HHW Class - XDocument14 pagesHHW Class - XCorona hai Corona thaNo ratings yet

- 5398 1 14999 1 10 20160905 PDFDocument22 pages5398 1 14999 1 10 20160905 PDFCrombone CarcassNo ratings yet

- 263 533 1 SM PDFDocument27 pages263 533 1 SM PDFRaluca DrbNo ratings yet

- Criticism of Human Geography PDFDocument15 pagesCriticism of Human Geography PDFtwiceokNo ratings yet

- Social Sciences Definition and OverviewDocument19 pagesSocial Sciences Definition and OverviewClaud NineNo ratings yet

- Diass Week 3-4Document4 pagesDiass Week 3-4Hilaria AguinaldoNo ratings yet

- Sociology & Anthropology: ContactDocument7 pagesSociology & Anthropology: ContactFaithNo ratings yet

- Effect of Learning Model Double Loop Problem Solving Using Powerpoint Media On Critical Thinking Skills and Learning Results of Social Studies in Elementary School StudentsDocument13 pagesEffect of Learning Model Double Loop Problem Solving Using Powerpoint Media On Critical Thinking Skills and Learning Results of Social Studies in Elementary School StudentsInternational Journal of Innovative Science and Research TechnologyNo ratings yet

- Human Geography: Definition, Scope and Principles Contemporary RelevanceDocument9 pagesHuman Geography: Definition, Scope and Principles Contemporary RelevanceSN JHA100% (2)

- Ajit Kumarroy: Aguidetoresearchmethodology For BeginnersDocument43 pagesAjit Kumarroy: Aguidetoresearchmethodology For BeginnersibrahimNo ratings yet

- Narrative AnalysisDocument22 pagesNarrative AnalysisOvidiu Bunea100% (2)

- Understanding Research Paradigms PDFDocument10 pagesUnderstanding Research Paradigms PDFFrea Mae ZerrudoNo ratings yet

- Araling Panlipunan - Syllabus Grades 9&10Document17 pagesAraling Panlipunan - Syllabus Grades 9&10Dinahrae valienteNo ratings yet

- Understanding Culture, Society and Politics: Arcelino C. Regis Integrated SchoolDocument9 pagesUnderstanding Culture, Society and Politics: Arcelino C. Regis Integrated SchoolArnel LomocsoNo ratings yet