Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Malaria Control Programmes: Magda Robalo, Josephine Namboze, Melanie Renshaw, Antoinette Ba-Nguz, Antoine Serufilira

Malaria Control Programmes: Magda Robalo, Josephine Namboze, Melanie Renshaw, Antoinette Ba-Nguz, Antoine Serufilira

Uploaded by

triCopyright:

Available Formats

You might also like

- Squeezed by Alissa Quart "Why Our Families Can't Afford America"Document6 pagesSqueezed by Alissa Quart "Why Our Families Can't Afford America"Zahra AfikahNo ratings yet

- Botros, Kamal Kamel - Mohitpour, Mo - Van Hardeveld, Thomas - Pipeline Pumping and Compression Systems - A Practical Approach (2013, ASME Press) - Libgen - lc-1Document615 pagesBotros, Kamal Kamel - Mohitpour, Mo - Van Hardeveld, Thomas - Pipeline Pumping and Compression Systems - A Practical Approach (2013, ASME Press) - Libgen - lc-1PGR ING.No ratings yet

- Infection During PregnancyDocument35 pagesInfection During PregnancyHusnawaty Dayu100% (2)

- Mastercool Air Conditioner Service ManualDocument2 pagesMastercool Air Conditioner Service ManualJubril Akinwande100% (1)

- MPI Painting CodeDocument28 pagesMPI Painting CodeGhayas JawedNo ratings yet

- Malaria Prevention TreatmentDocument6 pagesMalaria Prevention TreatmentjoelNo ratings yet

- Prevention of Mother-To-Child Transmission of HIV: Challenges For The Current DecadeDocument7 pagesPrevention of Mother-To-Child Transmission of HIV: Challenges For The Current DecadeHerry SasukeNo ratings yet

- Malaria in Pregnancy: PC Bhattacharyya, Manabendra NayakDocument4 pagesMalaria in Pregnancy: PC Bhattacharyya, Manabendra NayakKartikNo ratings yet

- Malaria During Pregnancy: DR - MeghnaDocument24 pagesMalaria During Pregnancy: DR - MeghnaMeghna GavaliNo ratings yet

- Hariom ProjectDocument28 pagesHariom Projectlalitsapkal1111No ratings yet

- Hiv On PregnancyDocument37 pagesHiv On PregnancyChristian112233No ratings yet

- Cleveland Clinic Journal of Medicine - Update Viral Hep PregnancyDocument5 pagesCleveland Clinic Journal of Medicine - Update Viral Hep PregnancyRoberto López MataNo ratings yet

- DyspneaDocument2 pagesDyspneaDesya SilayaNo ratings yet

- Effects of Malaria During Pregnancy On Infant Mortality in An Area of Low Malaria TransmissionDocument7 pagesEffects of Malaria During Pregnancy On Infant Mortality in An Area of Low Malaria Transmissiondiaa skamNo ratings yet

- Malaria in Pregnancy - A Literature Review - ScienceDirectDocument8 pagesMalaria in Pregnancy - A Literature Review - ScienceDirectsemabiaabenaNo ratings yet

- Malaria and Most Vulnerable Populations - Global Health and Gender Policy Brief March 2024Document9 pagesMalaria and Most Vulnerable Populations - Global Health and Gender Policy Brief March 2024The Wilson CenterNo ratings yet

- Prevention of Transmisión Review 2010Document17 pagesPrevention of Transmisión Review 2010IsmaelJoséGonzálezGuzmánNo ratings yet

- Livret MF GB21Document20 pagesLivret MF GB21mary15eugNo ratings yet

- Prevention of Mother-To-Child Transmission of HIV/AIDS ProgrammesDocument14 pagesPrevention of Mother-To-Child Transmission of HIV/AIDS ProgrammesFrenky PryogoNo ratings yet

- Dr. Endah Citraresmi, Sp.A (K) - A To Z HIV Exposed InfantDocument35 pagesDr. Endah Citraresmi, Sp.A (K) - A To Z HIV Exposed InfantAsti NuriatiNo ratings yet

- Assessing The Prevalence and Socio-Demographic Determinants of Malaria in Pregnant Women A Study at Fort Portal Regional Referral Hospital, UgandaDocument7 pagesAssessing The Prevalence and Socio-Demographic Determinants of Malaria in Pregnant Women A Study at Fort Portal Regional Referral Hospital, UgandaKIU PUBLICATION AND EXTENSIONNo ratings yet

- CARE Booklet EDocument4 pagesCARE Booklet EAnil MishraNo ratings yet

- Penyakit Infeksi Dan Kesehatan ReproduksiDocument33 pagesPenyakit Infeksi Dan Kesehatan ReproduksiSintia EPNo ratings yet

- Infectious Diseases in PregnancyDocument8 pagesInfectious Diseases in PregnancyPabinaNo ratings yet

- Infections in Pregnancy 2Document26 pagesInfections in Pregnancy 2Karanand Choppingboardd Rahgav MaharajNo ratings yet

- 109 Midterms TransesDocument28 pages109 Midterms TransestumabotaboarianeNo ratings yet

- Malaria Dalam Kehamilan: InfectionDocument40 pagesMalaria Dalam Kehamilan: InfectionBambang SulistyoNo ratings yet

- The Effect of Human Immunodeficiency Virus-1 Infection On Low Birth Weight, Mother To Child HIV Transmission and Infants' Death in African AreaDocument12 pagesThe Effect of Human Immunodeficiency Virus-1 Infection On Low Birth Weight, Mother To Child HIV Transmission and Infants' Death in African AreaariniNo ratings yet

- MCHN Midterm NotesDocument27 pagesMCHN Midterm NotesSeungwoo ParkNo ratings yet

- TorchDocument6 pagesTorchMary Jean HernaniNo ratings yet

- Acute Infections During PregnancyDocument63 pagesAcute Infections During PregnancyHussein AliNo ratings yet

- Torch Infections LectureDocument77 pagesTorch Infections LectureL MollyNo ratings yet

- Bahan Jurding Kaken 2Document7 pagesBahan Jurding Kaken 2Monica Dea RosanaNo ratings yet

- Malaria Prevention Treatment PDFDocument6 pagesMalaria Prevention Treatment PDFMardiyanto GeoNo ratings yet

- Syphilis in Pregnancy: Sexually Transmitted Infections May 2000Document8 pagesSyphilis in Pregnancy: Sexually Transmitted Infections May 2000LuthfianaNo ratings yet

- Viral Infections in Pregnant Women: Departemen Mikrobiologi Fak - Kedokteran USU MedanDocument46 pagesViral Infections in Pregnant Women: Departemen Mikrobiologi Fak - Kedokteran USU MedanSyarifah FauziahNo ratings yet

- Management of Viral Infection During Pregnancy: VaccinationDocument6 pagesManagement of Viral Infection During Pregnancy: VaccinationPOPA EMILIANNo ratings yet

- Malaria HIV Rick WebsiteDocument44 pagesMalaria HIV Rick WebsiteGita AditamaNo ratings yet

- 2023 OGClinNA An Overview of Antiviral Treatments in PregnancyDocument21 pages2023 OGClinNA An Overview of Antiviral Treatments in PregnancyMinerba MelendrezNo ratings yet

- Magnitude of Maternal and Child Health ProblemDocument8 pagesMagnitude of Maternal and Child Health Problempinkydevi97% (34)

- 2024.sifilis CongenitaDocument12 pages2024.sifilis CongenitaWILLIAM ROSALES CLAUDIONo ratings yet

- HIV in Mothers and Children: What's New?Document5 pagesHIV in Mothers and Children: What's New?VeronikaNo ratings yet

- Nihms 1049862Document26 pagesNihms 1049862Gabriella StefanieNo ratings yet

- Malaria in Pregnancy: Ebako Ndip Takem and Umberto D'AlessandroDocument8 pagesMalaria in Pregnancy: Ebako Ndip Takem and Umberto D'AlessandroRara MuuztmuuztmuccuNo ratings yet

- Neonatalandperinatal Infections: Amira M. Khan,, Shaun K. Morris,, Zulfiqar A. BhuttaDocument14 pagesNeonatalandperinatal Infections: Amira M. Khan,, Shaun K. Morris,, Zulfiqar A. BhuttaShofi Dhia AiniNo ratings yet

- Management of Varicella in Neonates and Infants: Sophie Blumental, Philippe LepageDocument6 pagesManagement of Varicella in Neonates and Infants: Sophie Blumental, Philippe LepageMaria Noviyanti FransiskaNo ratings yet

- Act Feb 2023 Congenital Syphilis Clinical Manifestations, EvaluationDocument74 pagesAct Feb 2023 Congenital Syphilis Clinical Manifestations, EvaluationdrirrazabalNo ratings yet

- Varicella During Pregnancy: A Case ReportDocument3 pagesVaricella During Pregnancy: A Case ReportCosmin RăileanuNo ratings yet

- Features and Diagnosis SifilisDocument56 pagesFeatures and Diagnosis SifilisdrirrazabalNo ratings yet

- CMV Pregnancy 20Document20 pagesCMV Pregnancy 20Татьяна ТутченкоNo ratings yet

- Chicken Pox in Pregnancy - A Challenge To The Obstetrician: Hem Kanta SarmaDocument2 pagesChicken Pox in Pregnancy - A Challenge To The Obstetrician: Hem Kanta SarmaDrDevdatt Laxman PitaleNo ratings yet

- TORCH MedscapeDocument17 pagesTORCH MedscapeAndrea RivaNo ratings yet

- NCM 109 Lec PrelimsDocument12 pagesNCM 109 Lec PrelimsAngel Kim MalabananNo ratings yet

- Navti 2016Document7 pagesNavti 2016XXXI-JKhusnan Mustofa GufronNo ratings yet

- Infectious Diseases Trans 2K2KDocument15 pagesInfectious Diseases Trans 2K2Kroselo alagaseNo ratings yet

- Research Chapters 1,2,3Document29 pagesResearch Chapters 1,2,3shafici DajiyeNo ratings yet

- MCN Reviewer 1STDocument10 pagesMCN Reviewer 1STAnthony Joseph ReyesNo ratings yet

- Maternal Note 1Document34 pagesMaternal Note 1JAN REY LANADONo ratings yet

- OB 13 Infectious Disease in PregnancyDocument17 pagesOB 13 Infectious Disease in PregnancyJoher100% (1)

- Framework of MCNDocument3 pagesFramework of MCNAngelica JaneNo ratings yet

- Varicella NeonatalDocument5 pagesVaricella NeonatalTias FirdayantiNo ratings yet

- 1995 Congenital Cytomegalovirus InfectionDocument10 pages1995 Congenital Cytomegalovirus InfectionIndra T BudiantoNo ratings yet

- NCM 109 Gyne Supplemental Learning Material 1Document25 pagesNCM 109 Gyne Supplemental Learning Material 1Zack Skyler Guerrero AdzuaraNo ratings yet

- Micheletti2018 PDFDocument67 pagesMicheletti2018 PDFtriNo ratings yet

- Daftar PustakaDocument4 pagesDaftar PustakatriNo ratings yet

- Menopausal Symptoms and Surgical Complications After Opportunistic Bilateral Salpingectomy, A Register-Based Cohort StudyDocument10 pagesMenopausal Symptoms and Surgical Complications After Opportunistic Bilateral Salpingectomy, A Register-Based Cohort StudytriNo ratings yet

- PDF KBB 139 PDFDocument4 pagesPDF KBB 139 PDFtriNo ratings yet

- Coronary Arteri DiseaseDocument3 pagesCoronary Arteri DiseasetriNo ratings yet

- Myocardial Contractile Dispersion: A New Marker For The Severity of Cirrhosis?Document5 pagesMyocardial Contractile Dispersion: A New Marker For The Severity of Cirrhosis?triNo ratings yet

- JCVTR 11 79Document6 pagesJCVTR 11 79triNo ratings yet

- VBIED Attack July 31, 2007Document1 pageVBIED Attack July 31, 2007Rhonda NoldeNo ratings yet

- Job Hazard AnalysisDocument1 pageJob Hazard AnalysisZaul tatingNo ratings yet

- Artificial Intelligence in PharmacyDocument8 pagesArtificial Intelligence in PharmacyMeraNo ratings yet

- Wired For: Hit Play For SexDocument7 pagesWired For: Hit Play For SexPio Jian LumongsodNo ratings yet

- The History of The Big Bang TheoryDocument6 pagesThe History of The Big Bang Theorymay ann dimaanoNo ratings yet

- To, The Medical Superintendent, Services Hospital LahoreDocument1 pageTo, The Medical Superintendent, Services Hospital LahoreAfraz AliNo ratings yet

- Vespa S 125 3V Ie 150 3V Ie UPUTSTVODocument90 pagesVespa S 125 3V Ie 150 3V Ie UPUTSTVOdoughstoneNo ratings yet

- MCN KweenDocument4 pagesMCN KweenAngelo SigueNo ratings yet

- Autoconceito ShavelsonDocument15 pagesAutoconceito ShavelsonJuliana SchwarzNo ratings yet

- Board Question Paper - March 2023 - For Reprint Update - 641b040f4992cDocument4 pagesBoard Question Paper - March 2023 - For Reprint Update - 641b040f4992cSushan BhagatNo ratings yet

- Nanoengineered Silica-Properties PDFDocument18 pagesNanoengineered Silica-Properties PDFkevinNo ratings yet

- STOC03 (Emissions)Document20 pagesSTOC03 (Emissions)tungluongNo ratings yet

- Benzene - It'S Characteristics and Safety in Handling, Storing & TransportationDocument6 pagesBenzene - It'S Characteristics and Safety in Handling, Storing & TransportationEhab SaadNo ratings yet

- Thermocouple Calibration FurnaceDocument4 pagesThermocouple Calibration FurnaceAHMAD YAGHINo ratings yet

- Piping SpecificationDocument5 pagesPiping SpecificationShandi Hasnul FarizalNo ratings yet

- Towncall Rural Bank, Inc.: To Adjust Retirement Fund Based On Retirement Benefit Obligation BalanceDocument1 pageTowncall Rural Bank, Inc.: To Adjust Retirement Fund Based On Retirement Benefit Obligation BalanceJudith CastroNo ratings yet

- Emotional IntelligenceDocument43 pagesEmotional IntelligenceMelody ShekharNo ratings yet

- Hospital Management System: Dept. of CSE, GECRDocument30 pagesHospital Management System: Dept. of CSE, GECRYounus KhanNo ratings yet

- Tehri DamDocument31 pagesTehri DamVinayakJindalNo ratings yet

- Phason FHC1D User ManualDocument16 pagesPhason FHC1D User Manuale-ComfortUSANo ratings yet

- Columbus CEO Leaderboard - Home Healthcare AgenciesDocument1 pageColumbus CEO Leaderboard - Home Healthcare AgenciesDispatch MagazinesNo ratings yet

- Inorganic Chemistry HomeworkDocument3 pagesInorganic Chemistry HomeworkAlpNo ratings yet

- PintoDocument18 pagesPintosinagadianNo ratings yet

- 2nd Quarter PHILO ReviewerDocument1 page2nd Quarter PHILO ReviewerTrisha Joy Dela Cruz80% (5)

- Long Quiz Earth Sci 11Document2 pagesLong Quiz Earth Sci 11Jesha mae MagnoNo ratings yet

- SRHR - FGD With Young PeopleDocument3 pagesSRHR - FGD With Young PeopleMandira PrakashNo ratings yet

Malaria Control Programmes: Magda Robalo, Josephine Namboze, Melanie Renshaw, Antoinette Ba-Nguz, Antoine Serufilira

Malaria Control Programmes: Magda Robalo, Josephine Namboze, Melanie Renshaw, Antoinette Ba-Nguz, Antoine Serufilira

Uploaded by

triOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Malaria Control Programmes: Magda Robalo, Josephine Namboze, Melanie Renshaw, Antoinette Ba-Nguz, Antoine Serufilira

Malaria Control Programmes: Magda Robalo, Josephine Namboze, Melanie Renshaw, Antoinette Ba-Nguz, Antoine Serufilira

Uploaded by

triCopyright:

Available Formats

CHAPTER 8 III

Malaria control programmes

Magda Robalo, Josephine Namboze, Melanie Renshaw, Antoinette Ba-Nguz, Antoine Serufilira

Malaria is an important health and development challenge in Africa, where pregnant women

and young children are most at risk. Each year approximately 800,000 children die from

malaria. Malaria in pregnancy contributes to a vicious cycle of ill-health in Africa, causing

babies to be born with low birthweight (LBW), which increases the risk of newborn and

infant deaths.

Effective interventions exist to break this cycle, like insecticide treated bednets (ITN) and

intermittent preventive treatment of malaria during pregnancy (IPTp). In recent years,

increased attention to and funding for malaria control has resulted in a significant

improvement in the coverage of malaria interventions, particularly for children. Further

reduction of the burden of malaria and malaria-related problems, especially in pregnancy,

requires strong linkages between malaria control programmes and maternal, newborn, and

child health (MNCH) programmes as well as better communication between homes and

health facilities. MNCH services offer the best mechanism through which malaria prevention

and control interventions can have a significant impact on newborn health. The question

remains, however, as to how these programmes can collaborate most effectively to save more

lives, not only from malaria and its effects, but from other causes, too.

Opportunities for Africa’s Newborns 127

Problem

Africa bears the highest burden of malaria in the world, with approximately 800,000 child deaths and

about 300 million malaria episodes per year.1 Malaria costs Africa more than US$12 billion annually and

slows economic growth of African countries by 1.3 percent per capita per year.2 High levels of malaria

are not just a consequence of poverty; they are also a cause of poverty, as malaria-endemic countries

have lower incomes and have experienced slower economic growth. Every year, 30 million women

become pregnant. For women living in endemic areas, malaria is a threat to both themselves and their

babies. Malaria-related maternal anaemia in pregnancy, low birthweight (LBW) and preterm births are

estimated to cause 75,000 to 200,000 deaths per year in sub-Saharan Africa.2 Pregnant women are

particularly vulnerable to malaria, whose effects are summarised in Figure III.8.1.

Effects on women: Pregnancy alters a woman’s immune response to malaria, particularly in the first

malaria-exposed pregnancy, resulting in more episodes of infection, more severe infection (for example,

cerebral malaria), and anaemia, all of which contribute to a higher risk of death. Malaria is estimated to

cause up to 15 percent of maternal anaemia, which is more frequent and severe in first pregnancies

than in subsequent pregnancies.3-5 The frequency and gravity of adverse effects of malaria in pregnancy

are related to the intensity of malaria transmission.

Effects on the fetus: Malaria is a risk factor for stillbirth, particularly in areas of unstable

transmission, where malaria levels fluctuate greatly across seasons and year to year and result in lower

rates of partial immunity. A study in Ethiopia found that placental parasitaemia was associated with

premature birth in both stable and unstable transmission settings. The investigators also found that

although placental parasitaemia was more common in stable transmission areas, there was a seven-fold

increase in the risk of stillbirth in unstable transmission areas.6 Even in the Gambia, where malaria is

highly endemic, the risk of stillbirth is twice as high in areas of less stable transmission.7

Effects on the baby: Malaria is rarely a direct cause of newborn death, but it has a significant indirect

effect on neonatal deaths since malaria in pregnancy causes LBW – the most important risk factor for

newborn death. Malaria can result in LBW babies who are preterm (born too early), small for

gestational age due to in utero growth restriction (IUGR), or both preterm and too small for

gestational age (See page 10 for more on the definitions of preterm birth and small for gestational age).

Consequently, it is imperative that MNCH programmes address the problem of malaria in pregnancy

while specific newborn care is also incorporated into malaria control programmes, especially in relation

to extra care of LBW babies.

Additionally, malaria in pregnancy indirectly influences newborn and child survival through its effects on

maternal mortality. If a mother dies during childbirth, her baby is more likely to die, and any surviving

children will face serious consequences for their health, development, and survival.8 Several studies

suggest that if a woman dies during childbirth in Africa, the baby will usually not survive.9;10

Recent research on the interaction between malaria and (MTCT), while others have suggested that placental

HIV infection in pregnancy shows that pregnant women malaria has a protective effect in reducing MTCT of

with HIV and malaria are more likely to be anaemic, and HIV.14;15 In any case, in areas with high prevalence of HIV

that the baby is at higher risk of LBW, preterm birth, and and malaria, the interaction between the two diseases has

death than with either HIV infection or malaria infection significant implications for programmes. Effective service

alone.12;13 The same studies suggest that malaria infection delivery to meet the demands of HIV/AIDS and malaria

may also result in an increased risk of postpartum sepsis requires the strengthening of antenatal care (ANC) and

for the mother. Some investigators have shown that postnatal care (PNC) for delivery of a comprehensive and

malaria contributes to increased HIV replication and may integrated package of interventions (Section III chapters

increase the risk of mother-to-child transmission 2, 4 and 7).

128 Opportunities for Africa’s Newborns

III

FIGURE III.8.1 Consequences of malaria infection in pregnancy

Pregnant woman

Morbidity

anemia

febrile illness Fetus

cerebral malaria Abortion

hypoglycaemia Stillbirth Newborn

puerperal sepsis Congenital malaria Low birthweight

Mortality infection (rare) prematurity

severe disease in utero growth restriction

haemorrhage Congenital malaria infection (rare)

Mortality

Adverse consequences of malaria during pregnancy: Adverse consequences of malaria during pregnancy:

Areas of low or unstable transmission Areas of high or moderate (stable) transmission

Acquired immunity – high • in absence of HIV infection,

Acquired immunity – low or none 1st and 2nd pregnancies are

at higher risk

Asymptomatic infection

Clinical illness

Anaemia Placental sequestration

• All pregnancies affected equally

Altered placental integrity

• Recognition and case management

needed in addition to prevention.

Severe disease In utero growth restriction and

increased risk of preterm birth

Risk to mother Risk to fetus

especially of preterm birth Maternal morbidity Low birthweight Higher infant

mortality

Source: Adapted from reference11

This chapter will discuss the current package and • Prevention using vector control, ITN, and IPTp

coverage of malaria interventions during pregnancy and

• Case management of women with malaria and

present opportunities for integrating a comprehensive

malaria-associated severe anaemia

malaria package with MNCH programmes. Challenges

will also be discussed along with practical steps. Strategies for prevention and control of malaria in

pregnancy may vary according to the local transmission

rate and are summarized in Table III.8.1.

Package and current coverage

It is estimated that in some areas, malaria contributes to

almost 30 percent of preventable causes of LBW, and the

majority of all newborn deaths occur among babies with

LBW. It is crucial, therefore, to prevent and manage

LBW, particularly the proportion of cases associated with

preterm birth, which has a much higher risk of death

than term LBW. It was previously thought that malaria

causes IUGR primarily, but recent work has shown that

malaria also results in a significantly increased risk of

preterm birth.16

The evidence based interventions for newborn survival

within the continuum of care have been introduced in

Section II, and the following interventions have been

shown to reduce the effects of malaria during pregnancy.17

Opportunities for Africa’s Newborns 129

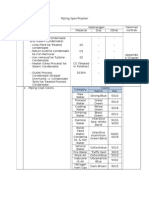

TABLE III.8.1 Malaria intervention strategies during pregnancy, according to transmission intensity

of malaria

Insecticide treated Intermittent preventive treatment Case

bednets (ITN) during pregnancy (IPTp) management

Provide pregnant women with a Limited risk for febrile illness and severe

High/medium standard IPTp dose at first malaria

transmission Begin use of ITN scheduled ANC visit after • Screen and treat anaemia with

Perennial (stable) early in pregnancy quickening. At the next routine antimalarial and iron supplements

and continue after provide an IPTp dose, with a • Promptly recognise and treat all

High/medium childbirth minimum of two doses given at potential malaria illness with an

transmission not less than one-month intervals effective drug

Seasonal (stable) Encourage the

practice of young

Low transmission children sleeping Based on current evidence, IPTp Risk for febrile illness and anaemia is high

(unstable) under ITN cannot be recommended in • Risk of severe malaria illness is high

these areas* • Promptly recognise and treat all

potential malaria illness with effective

drug

• Asymptomatic malaria – Screen and

treat anaemia with antimalarial and iron

supplements. Consider P.vivax in East

Africa

*In low transmission settings, the risk of malaria is low; therefore, the benefit from the presumptive use of drugs is likely to be reduced. And, because women in

these settings are more likely to have symptoms with their malaria infection, control programmes should focus on case management strategies and use of ITN.

Source: Adapted from reference11

Prevention through insecticide treated bednets (ITN) for achieving the coverage targets in many countries are

The effects of ITN on malaria in pregnancy have been improving. The main reasons for low coverage appear to

studied in five randomised controlled trials. A recent have been the high cost of nets and the historical lack of

Cochrane analysis showed that in Africa, the use of ITN, availability of ITN, especially in eastern and southern

compared with no nets, reduced placental malaria in all Africa. While social marketing and other activities have

pregnancies (relative risk (RR) 0.79, 95 percent been successful in raising ITN coverage among the

confidence interval (CI) 0.63 to 0.98). Use of ITN also wealthier sectors of the community, they were less

reduced LBW (RR 0.77, 95 percent CI 0.61 to 0.98), successful in targeting the poorest rural communities,

stillbirths, and abortions in the first to fourth pregnancy which include those most at risk from malaria. This has

(RR 0.67, 95 percent CI 0.47 to 0.97), but not in led to a recent global shift in policy towards providing

women with more than four previous pregnancies.18 For pregnant women and children with highly subsidised or

anaemia and clinical malaria, results tended to favour free ITN. This is reflected in the revised Roll Back

ITN, but the effects were not significant. In conclusion, Malaria (RBM) ITN strategic framework.19 A recent

ITN beneficially influences pregnancy outcome in WHO resolution called for the application of expeditious

malaria-endemic regions of Africa when used by and cost-effective approaches, including free, or highly

communities or by individual women. Given the subsidised, distribution of materials and medicines to

evidence of efficacy of ITN for children and pregnant vulnerable groups, with the aim of at least 80 percent of

women in both stable and unstable transmission settings, pregnant women receiving IPTp and using ITN,

combined with the opportunity to achieve high coverage wherever that is the vector control method of choice.

of services for women and children through ANC Additionally, an increasing number of pregnant women,

services, recommended programmatic approaches include especially in areas of unstable transmission, are being

distribution of ITN to pregnant women in all protected from malaria infection through the expansion

transmission settings through ANC or similar platforms. of indoor residual spraying programmes.

This way, newborns benefit directly from ITN Prevention through intermittent preventive treatment

interventions, especially during the first few months of during pregnancy (IPTp)

life, when they are particularly vulnerable to malaria. IPTp is the administration of full, curative treatment

A few countries, such as Eritrea and Malawi, have reached doses of an effective antimalarial medicine at predefined

ITN coverage rates of over 60 percent for both pregnant intervals during pregnancy, beginning in the second

women and children (Box III.8.1). Rapid scaling up is trimester or after quickening, and delivered through

happening in several countries such as Benin, Niger, routine antenatal services. Currently, sulfadoxine-

Ethiopia, Kenya, Togo, and Zambia, and the prospects pyrimethamine (SP) is the only available drug for use in

130 Opportunities for Africa’s Newborns

Intermittent preventive treatment

FIGURE III.8.2

with SP is a feasible intervention because SP is III

of malaria during pregnancy (IPTp) adoption administered as a directly observed treatment through

and implementation in the WHO African scheduled ANC visits, and ANC reaches a high

region (August 2006) proportion of pregnant women in most African countries.

However, the effectiveness of SP for IPTp is likely to be

compromised due to the increase in resistance to SP,

particularly in eastern and southern Africa. While

pregnant women may currently benefit from IPTp with

SP, there is an urgent need to identify alternative drugs

that are safe, cheap, and easy to administer.

Figure III.8.2 illustrates the status of policy adoption and

implementation of IPTp in the WHO African region.

With the exception of one country, all countries in the

region have adopted IPTp as a policy for malaria

prevention and control during pregnancy where

recommended, but implementation of this policy remains

very low in most countries. In the remaining countries,

IPTp adopted/being implemented (35) given the transmission pattern, IPTp is not a

IPTp yet to be adopted (1) recommended policy, based on current evidence of IPTp

IPTp not recommended (10)

efficacy in areas of low transmission.

Data from 11 Demographic and Health Surveys (DHS)

within the past three years indicate that although two-

Source: WHO Regional Office for Africa, 2006.

thirds of pregnant women attend at least one ANC visit,

only 10 percent had taken at least one dose of SP (Figure

IPTp. IPTp doses using SP should not be given more

III.8.3). Though slower than perhaps anticipated, IPTp

frequently than monthly. IPTp is recommended in areas

uptake has increased in countries where IPTp has been

of stable malaria transmission, where most malaria

adopted in national policy as a malaria control

infections in pregnancy are asymptomatic and the usual

intervention (1993 in Malawi, 1998 in Kenya, Uganda,

case management approach of treating symptomatic

and Tanzania, and 2002 in Zambia). The ITN coverage

individuals is not applicable. Current evidence on the

in these countries ranges from about 5 to 35 percent.22

effectiveness of IPTp in areas of low transmission, where

symptomatic case management can be used, is insufficient Figure III.8.3 highlights the missed opportunities that

to support its use in these settings. exist when mothers who attend at least one ANC visit are

not provided with effective, integrated services. This is a

The effectiveness of IPTp in reducing maternal anaemia

result of many factors, including a lack of perceived need

and LBW has been demonstrated from studies in Kenya,

for IPTp by pregnant women; late and few ANC visits;

Malawi, Mali, and Burkina Faso. In Kenya, a trial

health system inadequacies, such as supply shortages of

conducted with SP given twice during pregnancy at ANC

ITN, SP, or iron/folate; human resource limitations;

visits reduced maternal anaemia in first pregnancies by

reluctance among service providers to prescribe SP during

about 39 percent, while lowering rates of LBW.20 Another

pregnancy; weak laboratory services to support case

study in western Kenya demonstrated that the two-dose

management; and weak monitoring systems and health

SP regimen was adequate in areas of low HIV prevalence,

referral systems to support case management.

but more doses were needed in areas with higher HIV

prevalence.21 From the programmatic perspective, IPTp

FIGURE III.8.3 Missed opportunities: Key malaria interventions absent in antenatal care

Attended at least one antenatal visit Slept under a net Took SP during pregnancy

Percentage of pregnant women

100 92

88

83

73

75

60

50

24

25 15

12 10 13

5

0.1 11 1

0

Burkina Faso Cameroon Ghana Kenya Nigeria

Source: Demographic and Health Survey data 2003-2004

Opportunities for Africa’s Newborns 131

Although knowledge of malaria and attendance at service, negative perceptions among both health workers

ANC services are both generally high among African and pregnant women regarding the usefulness of the

populations, several studies have shown that this strategy, and concerns over the use of the drug during

knowledge does not necessarily translate to increased pregnancy.25-27 In addition, since SP is only taken in the

demand for IPTp or improved IPTp coverage within second and third trimesters, poor timing of ANC visits

ANC.23-25 These findings have been corroborated by and the recommended IPTp schedule may be adversely

several other studies, and low uptake appears to be related influencing implementation. (Section III chapter 2).

to unavailability of adequate SP supplies at the point of

Progress towards malaria prevention in Malawi: Rapidly scaling up use

BOX III.8.1

of insecticide treated bednets (ITN) and intermittent preventive treatment of

malaria in pregnancy (IPTp)

According to the March 2004 National Household Malaria Survey in Malawi, 53 percent of urban and 22

percent of rural children under the age of five and 36 percent and 17 percent of urban and rural pregnant

women, respectively, sleep under ITN. While inequity between urban and rural populations is still significant,

this marks progress since the

The challenge of reaching the rural population with ITN and IPTp year 2000 and a step in the

right direction for reaching

100%

underserved populations.

Overall, coverage is

75% 2000 2004 increasing. With the

P e rc e n t c o v e ra g e

distribution of an additional

1.8 million nets since the

50%

March 2004 survey, the

coverage of children and

25% pregnant women using ITN is

estimated to be 60 percent

0%

and 55 percent respectively.

ITN use - U5 (urban) ITN use - U5 (rural) ITN use - pregnant ITN use - pregnant At least one dose At least one dose

women (urban) women (rural) of IPTp (urban) of IPTp (rural) Overall, this demonstrates

that coverage is increasing

and Malawi has likely

achieved the Abuja targets for the distribution of ITNs. The Ministry of Health estimates that coverage of

pregnant women receiving a second dose of IPTp has increased from 55 percent in 2004 to 60 percent by

the end of 2005. These gains have come alongside massive amounts of effort. In addition to ITN

distribution, four million treatment kits were procured and distributed in 2005 and three million nets were

treated with insecticides during an annual net re-treatment campaign.

Malawi’s increased attention to ITN and IPTp could be reflected in decreasing mortality rates. Between

1990 and 2000, infant and child mortality rates remained unchanged at 112 and 187 per 1000 live births,

respectively. Over the past four years (2000-2004), however, a remarkable decline has been observed.

2004 DHS data indicate that infant and child mortality rates decreased to 76 and 133 per 1,000 live births,

respectively. Improvement has occurred in all age groups, most dramatically during the first month of life:

DHS reported a decrease in the neonatal mortality rate (NMR) from 40 to 27 per 1,000 live births. There

are some uncertainties around the NMR measurement, as DHS tends to underestimate NMR, but progress

has certainly been made. While the association between increased malaria prevention efforts and declining

MMR is an ecological level association, it is likely that scaling up malaria interventions contributed

significantly to the observed decline in mortality rates.

Source: Malawi 2000 and 2004 Demographic and Health Surveys and 2004 National Household Malaria Survey

For more discussion of NMR and under-five mortality rate, see Section I and the data notes as well as the country profile for Malawi

(page 200). For more discussion of countries that are progressing towards NMR reduction, see Section IV.

132 Opportunities for Africa’s Newborns

Opportunities to integrate MNCH and promoting the investment in health system strengthening, III

malaria control programmes using funds earmarked for immunisation, a more vertical

programme. Even without this significant level of

Malaria control programmes target pregnant mothers and investment, a similar approach by otherwise vertical

in doing so, benefit the mother and fetus, which malaria programmes to strengthen local infrastructure,

contributes to improved health for the newborn and capacity, and supplies has the potential to benefit both

child. It has been noted that if mothers understand that malaria intervention coverage and other essential MNCH

interventions also protect their unborn babies, they put interventions.

their own fears aside for the health of their unborn child.

In Zambia, uptake of IPTp was found to be low because There are also other opportunities for more innovative

SP was perceived as being “too strong” and dangerous to linkages.

the unborn baby. However, when health workers • Where communities are being sensitised to early care

changed the message to focus on the unborn baby, better seeking for babies with malaria, education about danger

compliance to SP was noted.22 These messages signs for pregnant women and newborns could be

demonstrate the importance of considering the health of included

mother and baby together and the potential benefit of • Where community health workers (CHWs) are being

stronger linkages between malaria programmes and trained in the case management of children with

MNCH. Several opportunities exist to benefit newborn malaria, training in newborn care could also be

health through malaria programmes. These include both undertaken

direct and indirect approaches. • Where supplies for malaria case management are being

strengthened, pre-referral medicines for newborns could

Direct benefit in saving newborn lives will result from also be included for the management of sepsis, which

increasing coverage of IPTp and ITN and improving case also presents with fever

management of pregnant women with malaria. As ANC • Strategies for behaviour change communication could

is the logical point of entry for malaria services (IPTp and be expanded to include health messages that benefit

ITN), strong collaboration is necessary between malaria both mother and newborn while incorporating malaria-

and MNCH programmes, specifically in terms of specific messages, such as the importance of mothers

training, procurement of drugs and supplies, health sleeping alongside their newborns under ITN

education, etc. For example, commodities needed for • The case management of women with malaria or severe

IPTp and ITN delivery are often procured under malaria anaemia could be integrated with emergency obstetric

control programmes, but interventions are normally care

delivered through reproductive health services. This could

provide an opportunity for integration even beyond

malaria programmes and MNCH, but lack of Challenges to integrating MNCH and

communication could minimise possible gains. malaria control programmes

Another under-explored possibility is the use of private Malaria programmes have been extremely successful in

providers and community-based organisations to deliver focusing global attention and seizing policy opportunities.

more services. Historically, ITN distribution has been The RBM partnership in particular has garnered the

linked with community-based programmes, but IPTp is attention of global and national policy agendas. Funding

still limited to health facilities. Many mothers live far for malaria has increased, and coverage of essential

from these facilities and miss out on key services. interventions, particularly ITN, is beginning to

Evidence emerging from community programmes in accelerate. The linking of MNCH and malaria control

Uganda, Kenya, and Zambia shows that not only is programmes has a significant role to play in the

community delivery of IPTp useful in improving achievement of Millennium Development Goals (MDGs)

coverage, but it also increases ANC attendance at an 4 and 5 for child and maternal survival as well as MDG 6

important time during pregnancy. Community outreach for HIV/AIDS, tuberculosis (TB), and malaria. For the

programmes should support and complement health biggest gains in both malaria control and MNCH,

facility services and vice versa. In particular, the implementation of malaria-specific interventions must

development of three-way linkages between outreach take place within an efficient, working health system that

services for newborn health, malaria programmes, and includes effective ANC, strong community health systems

community Integrated Management of Childhood Illness that emphasise the importance of the recognition of

(C-IMCI) should be encouraged. complications, and prompt case management and/or

Indirect benefit to newborns is possible when referral. However, lack of implementation of policies

investment in malaria programmes leads to the promoting these opportunities for integration as well

strengthening of general health system vehicles for service as general health system weaknesses continue to pose

delivery, such as ANC and PNC. The Global Alliance for challenges.

Vaccines and Immunisation (GAVI) is leading the way in

Opportunities for Africa’s Newborns 133

Policy challenges WHO recommendations, most African countries have

At the level of national policy, malaria and reproductive moved from monotherapies to Artemisinin-based

health programmes are usually housed under different combination therapies (ACT). However, Artemisinin

departments or directorates within Ministries of Health. derivatives are not yet recommended for treatment of

This separation can impede collaboration and result in malaria during the first trimester unless there is no

policy duplication or confusion. For example, in one suitable alternative; ACTs are recommended for use in the

country, the reproductive health programme is under the second and third trimesters. Quinine is the drug of choice

commission of community health, while malaria control throughout pregnancy, but this poses adherence

is under the commission for the control of communicable problems, as quinine has to be given over seven days. An

diseases. These two departments have separate meetings; additional issue is that treatment of malaria in children

therefore, decisions are often made without due weighing less than 5 kg with ACTs is not recommended.

consultation on the implications for the other The recommended treatment for these children is also

programme. The problem is magnified when the quinine.

responsibilities of each programme are not clearly

In situations where SP has been withdrawn for routine

defined. Past approaches to malaria prevention have been

treatment of malaria, it is sometimes difficult to

vertical, fragmented, and not always integrated in

rationalise the approval of SP use for IPTp by national

MNCH services, resulting in limited access and public

pharmaceutical boards or other regulatory authorities.

health impact. There is an urgent need for multilateral

The emergence of P. falciparum resistance to SP, which

collaboration in every country to address malaria in

has now been documented in many African countries, has

pregnancy while strengthening routine MNCH services

raised concerns about the efficacy of SP for IPTp. The

and linking with other related interventions, such as HIV

fact that there are limited data to guide countries with

and sexually transmitted infection (STI) care. Ongoing

moderate to high levels of SP resistance on use of SP for

work towards the targets set out in the Abuja Declaration

IPTp threatens the future of this strategy. A WHO

continues to reflect the kind of convergence of political

consultative meeting held in October 2005 has now

momentum, institutional synergy, and technical

clarified this issue (Box III.8.2).

consensus needed in order to combat malaria.

On a more programmatic level, there is a need to

consider the challenge of malaria treatment policy in the

particular context of malaria during pregnancy. Following

BOX III.8.2 Recommendations from World Health Organization (WHO)

consultative meeting on SP use in settings with different levels of SP resistance

WHO recommends the following for malaria prevention and control during pregnancy in moderate to high

levels of SP resistance:

In areas where up to 30 percent parasitological failure at D14 is reported, countries should:

• Continue implementing or adopt a policy of at least two doses of intermittent preventive treatment

of malaria in pregnancy (IPTp) with SP; implement other malaria control measures, such as insecticide

treated bednet (ITN) use as well as anaemia and malaria case management

• Evaluate the impact of SP for IPTp on an ongoing basis.

In areas where 30 to 50 percent parasitological failure at D14 is reported, countries should:

• Continue implementing or adopt a policy of at least two doses of IPTp with SP

• Emphasize the use of ITN

• Strengthen anaemia and malaria case management

• Evaluate the impact of SP for IPTp on an ongoing basis

In areas where 50 percent parasitological failure at D14 is reported, countries should:

• Emphasise ITN use as well as anaemia and malaria case management

• If an appropriate policy already exists, continue IPTp with at least two doses of SP; evaluate the impact on

an ongoing basis

• In the absence of policy, consider adopting the use of IPTp with SP only after further evidence is available

Source: Reference28

134 Opportunities for Africa’s Newborns

Weak health systems Practical steps to advance integration III

Even where good policy is in place, health system

This chapter has emphasised that the impact of malaria

weaknesses, particularly human resource shortages and

control programmes on newborn health is primarily

commodity procurement and supply, can slow policy

realised through effective MNCH services. There is a

implementation. Malaria diagnosis, especially in high

fundamental need, therefore, for convergence between

transmission settings, already presents a challenge. A

malaria programmes and MNCH; a process which can be

combination of overburdened health workers and

strengthened with the following steps.

changing treatment policies without adequate in-service

training can result in poor quality services. A quality Advocate for a holistic approach that secures funding

assessment of public and private ANC services in to strengthen the continuum of care. Ensuring that a

Tanzania, for example, reveals that guidelines for holistic approach to MNCH is included in malaria

dispensing medicines for anaemia and malaria prevention funding opportunities is of paramount importance. A

are not being followed.29 Africa’s current human resource case in point is the potential for expanding services

challenges and possible solutions are covered in more targeting malaria control during pregnancy to include

detail in Section IV. neonatal interventions through support from the Global

Fund for AIDS, TB and Malaria, the Presidential Malaria

The inadequate or unreliable supply of medication and

Initiative, and the World Bank Malaria Booster

other commodities is a major challenge that threatens the

programme as well as other funds. Premature birth

health system overall. Several of the effective interventions

resulting from malaria parasitaemia can justify the

proposed for significant and rapid improvement of

inclusion of targeted interventions at both community

maternal and newborn health and survival are reliant on

and health facility levels within a malaria funding

the provision of commodities such as SP, ITN, tetanus

proposal.

toxoid vaccine, and antibiotics. The global manufacture

and supply of ITN, especially Long Lasting Insecticidal Integrate policy, implementation guidelines, and

Nets (LLIN), failed to keep pace with demand during delivery with MNCH services. The policies facilitating

2004 and 2005, but these bottlenecks have significantly delivery and use of various strategies need to be

eased in 2006, with global production of nets estimated harmonised across MNCH and malaria control

to exceed 70 million during the year. The need for programmes. In most cases, policies are developed and

accurate and timely procurement forecasting is evident.30 published by one programme without consultation or a

review of potential negative effects on other programmes.

Weak referral systems continue to impede care. The

A review of policy implementation guidelines will need to

recognition of danger signs and complications at the

be undertaken to ensure that newborn health is addressed

community level needs to be complemented by an

rather than implied.

efficient referral process and backed up by high quality,

effective care at health facilities. This will improve the Use the opportunity of strengthening malaria services

management of malaria and ensure that obstetric to improve other care delivered through ANC and

emergencies and other complications identified at integrated management of childhood illness (IMCI)

community level are managed with skilled care at programmes. Addressing constraints in malaria

a facility. management could also benefit mothers and newborns

Health system strengthening requires stronger linkages at

all levels between groups working for MNCH and groups

focusing on specific causes such as malaria or HIV. The

recent integration of global level partnerships to form the

Partnership for Maternal, Newborn & Child Health

(PMNCH) offers great potential for integration and

improved communication with the RBM partnership and

other specific initiatives. Mechanisms to ensure effective

communication and information flow among the

different partnerships are urgently required to facilitate

the exchange of ideas, experiences, and best practices as

well as streamline operations, increase funding, and

ensure supplies, thereby avoiding duplication of effort

and improving outcomes for the betterment of children’s

and mothers’ health.

Opportunities for Africa’s Newborns 135

with other conditions through ANC and IMCI. For women and uptake of IPTp. However, coverage of both

example, while strengthening malaria services in ANC of these interventions currently remains relatively low

and IMCI, other aspects of ANC and IMCI may also be compared to ANC, which can provide an optimum

improved, especially in terms of advocating for the delivery platform. Challenges to scaling up IPTp

provision of other commodities and services. The implementation include the need to create demand

distribution of ITN during ANC visits and other among pregnant women for IPTp through ANC, increase

outreach opportunities has resulted in increased uptake of recognition by families and communities that pregnant

these services. Improved referral of neonatal sepsis could women and their unborn babies are at serious risk from

be integrated with efforts to improve case management of malaria, and improve the supply and management of

children with malaria. Malaria policies are often well commodities. Other limiting factors include increasing

regarded by decision makers, presenting an opportunity resistance to SP, which may ultimately have a negative

to utilise this goodwill by advocating for a minimum impact on the effectiveness of IPTp with SP. Alternative

package to address the special requirements of malaria- antimalarial prophylaxis for IPTp and for the treatment

related fever in newborns, for example. of pregnant women with malaria are urgently required.

Use the opportunity of strengthening laboratory With heightened policy attention and an increased

facilities and supplies for malaria to improve overall availability of resources for malaria prevention and

logistics for supplies in emergency obstetric and control from a variety of sectors, more pregnant women

newborn care and IMCI. Strengthening procurement of will be able to access IPTp, more pregnant women and

drugs and commodities, supplies management, and their babies will be sleeping under ITNs, and the number

laboratory services would benefit not only malaria of mothers and children receiving effective treatment for

programmes but also management of neonatal sepsis and malaria will increase. The funding environment is

provision of emergency obstetric care. Linking with currently supportive of greater integration of MNCH

malaria programmes could strengthen IMCI by with malaria control programmes. Coordination among

addressing the need for supplies of pre-referral drugs that malaria control programmes and MNCH is required for

can be used in the management of neonatal sepsis, in implementation of integrated, effective services.

particular. (Section III chapter 5).

Use the opportunity of social mobilisation and

behaviour change communication techniques to

increase demand for MNCH services. Early recognition Priority actions for integrating

of danger signs in mothers, newborns, and children needs malaria control programmes

to be incorporated into social mobilisation and with MNCH

communication interventions at the community level,

using a range of tools and approaches, from mass media • Advocate for a holistic approach that secures

to interpersonal communication. Recognition of malaria funding to strengthen essential MNCH packages

danger signs and home management of malaria and programmes along the continuum of care

programmes could be extended to include recognition • Integrate malaria policy, implementation

of newborn danger signs and signs of obstetric guidelines, and delivery with MNCH services

complications. Communication interventions can create

• Use the opportunity of strengthening malaria

demand for newborn health care services, especially in

services to improve other care delivered through

countries where mothers and newborns traditionally

ANC and IMCI in particular

remain in the home for several days. Another potential

opportunity is the addition of clean birth kits to the • Use the opportunity of strengthening lab facilities

pre-packaged drug kits provided for home management and supplies for malaria to improve logistics for

of malaria. supplies in emergency obstetric and neonatal care

and IMCI

• Use the opportunity of social mobilisation and

Conclusion

behaviour change communication techniques to

Improving newborn health in resource-poor settings is an increase demand for MNCH services

enormous challenge but not an insurmountable one,

particularly because newborn morbidity and mortality is

not attributable to a single cause, but to a multiplicity of

factors, of which many can be addressed through existing

programmes. Malaria is one of these factors affecting the

health of the mother and leading to ill health of the

newborn. Effective interventions are available to address

malaria in pregnancy - the use of ITN by pregnant

136 Opportunities for Africa’s Newborns

You might also like

- Squeezed by Alissa Quart "Why Our Families Can't Afford America"Document6 pagesSqueezed by Alissa Quart "Why Our Families Can't Afford America"Zahra AfikahNo ratings yet

- Botros, Kamal Kamel - Mohitpour, Mo - Van Hardeveld, Thomas - Pipeline Pumping and Compression Systems - A Practical Approach (2013, ASME Press) - Libgen - lc-1Document615 pagesBotros, Kamal Kamel - Mohitpour, Mo - Van Hardeveld, Thomas - Pipeline Pumping and Compression Systems - A Practical Approach (2013, ASME Press) - Libgen - lc-1PGR ING.No ratings yet

- Infection During PregnancyDocument35 pagesInfection During PregnancyHusnawaty Dayu100% (2)

- Mastercool Air Conditioner Service ManualDocument2 pagesMastercool Air Conditioner Service ManualJubril Akinwande100% (1)

- MPI Painting CodeDocument28 pagesMPI Painting CodeGhayas JawedNo ratings yet

- Malaria Prevention TreatmentDocument6 pagesMalaria Prevention TreatmentjoelNo ratings yet

- Prevention of Mother-To-Child Transmission of HIV: Challenges For The Current DecadeDocument7 pagesPrevention of Mother-To-Child Transmission of HIV: Challenges For The Current DecadeHerry SasukeNo ratings yet

- Malaria in Pregnancy: PC Bhattacharyya, Manabendra NayakDocument4 pagesMalaria in Pregnancy: PC Bhattacharyya, Manabendra NayakKartikNo ratings yet

- Malaria During Pregnancy: DR - MeghnaDocument24 pagesMalaria During Pregnancy: DR - MeghnaMeghna GavaliNo ratings yet

- Hariom ProjectDocument28 pagesHariom Projectlalitsapkal1111No ratings yet

- Hiv On PregnancyDocument37 pagesHiv On PregnancyChristian112233No ratings yet

- Cleveland Clinic Journal of Medicine - Update Viral Hep PregnancyDocument5 pagesCleveland Clinic Journal of Medicine - Update Viral Hep PregnancyRoberto López MataNo ratings yet

- DyspneaDocument2 pagesDyspneaDesya SilayaNo ratings yet

- Effects of Malaria During Pregnancy On Infant Mortality in An Area of Low Malaria TransmissionDocument7 pagesEffects of Malaria During Pregnancy On Infant Mortality in An Area of Low Malaria Transmissiondiaa skamNo ratings yet

- Malaria in Pregnancy - A Literature Review - ScienceDirectDocument8 pagesMalaria in Pregnancy - A Literature Review - ScienceDirectsemabiaabenaNo ratings yet

- Malaria and Most Vulnerable Populations - Global Health and Gender Policy Brief March 2024Document9 pagesMalaria and Most Vulnerable Populations - Global Health and Gender Policy Brief March 2024The Wilson CenterNo ratings yet

- Prevention of Transmisión Review 2010Document17 pagesPrevention of Transmisión Review 2010IsmaelJoséGonzálezGuzmánNo ratings yet

- Livret MF GB21Document20 pagesLivret MF GB21mary15eugNo ratings yet

- Prevention of Mother-To-Child Transmission of HIV/AIDS ProgrammesDocument14 pagesPrevention of Mother-To-Child Transmission of HIV/AIDS ProgrammesFrenky PryogoNo ratings yet

- Dr. Endah Citraresmi, Sp.A (K) - A To Z HIV Exposed InfantDocument35 pagesDr. Endah Citraresmi, Sp.A (K) - A To Z HIV Exposed InfantAsti NuriatiNo ratings yet

- Assessing The Prevalence and Socio-Demographic Determinants of Malaria in Pregnant Women A Study at Fort Portal Regional Referral Hospital, UgandaDocument7 pagesAssessing The Prevalence and Socio-Demographic Determinants of Malaria in Pregnant Women A Study at Fort Portal Regional Referral Hospital, UgandaKIU PUBLICATION AND EXTENSIONNo ratings yet

- CARE Booklet EDocument4 pagesCARE Booklet EAnil MishraNo ratings yet

- Penyakit Infeksi Dan Kesehatan ReproduksiDocument33 pagesPenyakit Infeksi Dan Kesehatan ReproduksiSintia EPNo ratings yet

- Infectious Diseases in PregnancyDocument8 pagesInfectious Diseases in PregnancyPabinaNo ratings yet

- Infections in Pregnancy 2Document26 pagesInfections in Pregnancy 2Karanand Choppingboardd Rahgav MaharajNo ratings yet

- 109 Midterms TransesDocument28 pages109 Midterms TransestumabotaboarianeNo ratings yet

- Malaria Dalam Kehamilan: InfectionDocument40 pagesMalaria Dalam Kehamilan: InfectionBambang SulistyoNo ratings yet

- The Effect of Human Immunodeficiency Virus-1 Infection On Low Birth Weight, Mother To Child HIV Transmission and Infants' Death in African AreaDocument12 pagesThe Effect of Human Immunodeficiency Virus-1 Infection On Low Birth Weight, Mother To Child HIV Transmission and Infants' Death in African AreaariniNo ratings yet

- MCHN Midterm NotesDocument27 pagesMCHN Midterm NotesSeungwoo ParkNo ratings yet

- TorchDocument6 pagesTorchMary Jean HernaniNo ratings yet

- Acute Infections During PregnancyDocument63 pagesAcute Infections During PregnancyHussein AliNo ratings yet

- Torch Infections LectureDocument77 pagesTorch Infections LectureL MollyNo ratings yet

- Bahan Jurding Kaken 2Document7 pagesBahan Jurding Kaken 2Monica Dea RosanaNo ratings yet

- Malaria Prevention Treatment PDFDocument6 pagesMalaria Prevention Treatment PDFMardiyanto GeoNo ratings yet

- Syphilis in Pregnancy: Sexually Transmitted Infections May 2000Document8 pagesSyphilis in Pregnancy: Sexually Transmitted Infections May 2000LuthfianaNo ratings yet

- Viral Infections in Pregnant Women: Departemen Mikrobiologi Fak - Kedokteran USU MedanDocument46 pagesViral Infections in Pregnant Women: Departemen Mikrobiologi Fak - Kedokteran USU MedanSyarifah FauziahNo ratings yet

- Management of Viral Infection During Pregnancy: VaccinationDocument6 pagesManagement of Viral Infection During Pregnancy: VaccinationPOPA EMILIANNo ratings yet

- Malaria HIV Rick WebsiteDocument44 pagesMalaria HIV Rick WebsiteGita AditamaNo ratings yet

- 2023 OGClinNA An Overview of Antiviral Treatments in PregnancyDocument21 pages2023 OGClinNA An Overview of Antiviral Treatments in PregnancyMinerba MelendrezNo ratings yet

- Magnitude of Maternal and Child Health ProblemDocument8 pagesMagnitude of Maternal and Child Health Problempinkydevi97% (34)

- 2024.sifilis CongenitaDocument12 pages2024.sifilis CongenitaWILLIAM ROSALES CLAUDIONo ratings yet

- HIV in Mothers and Children: What's New?Document5 pagesHIV in Mothers and Children: What's New?VeronikaNo ratings yet

- Nihms 1049862Document26 pagesNihms 1049862Gabriella StefanieNo ratings yet

- Malaria in Pregnancy: Ebako Ndip Takem and Umberto D'AlessandroDocument8 pagesMalaria in Pregnancy: Ebako Ndip Takem and Umberto D'AlessandroRara MuuztmuuztmuccuNo ratings yet

- Neonatalandperinatal Infections: Amira M. Khan,, Shaun K. Morris,, Zulfiqar A. BhuttaDocument14 pagesNeonatalandperinatal Infections: Amira M. Khan,, Shaun K. Morris,, Zulfiqar A. BhuttaShofi Dhia AiniNo ratings yet

- Management of Varicella in Neonates and Infants: Sophie Blumental, Philippe LepageDocument6 pagesManagement of Varicella in Neonates and Infants: Sophie Blumental, Philippe LepageMaria Noviyanti FransiskaNo ratings yet

- Act Feb 2023 Congenital Syphilis Clinical Manifestations, EvaluationDocument74 pagesAct Feb 2023 Congenital Syphilis Clinical Manifestations, EvaluationdrirrazabalNo ratings yet

- Varicella During Pregnancy: A Case ReportDocument3 pagesVaricella During Pregnancy: A Case ReportCosmin RăileanuNo ratings yet

- Features and Diagnosis SifilisDocument56 pagesFeatures and Diagnosis SifilisdrirrazabalNo ratings yet

- CMV Pregnancy 20Document20 pagesCMV Pregnancy 20Татьяна ТутченкоNo ratings yet

- Chicken Pox in Pregnancy - A Challenge To The Obstetrician: Hem Kanta SarmaDocument2 pagesChicken Pox in Pregnancy - A Challenge To The Obstetrician: Hem Kanta SarmaDrDevdatt Laxman PitaleNo ratings yet

- TORCH MedscapeDocument17 pagesTORCH MedscapeAndrea RivaNo ratings yet

- NCM 109 Lec PrelimsDocument12 pagesNCM 109 Lec PrelimsAngel Kim MalabananNo ratings yet

- Navti 2016Document7 pagesNavti 2016XXXI-JKhusnan Mustofa GufronNo ratings yet

- Infectious Diseases Trans 2K2KDocument15 pagesInfectious Diseases Trans 2K2Kroselo alagaseNo ratings yet

- Research Chapters 1,2,3Document29 pagesResearch Chapters 1,2,3shafici DajiyeNo ratings yet

- MCN Reviewer 1STDocument10 pagesMCN Reviewer 1STAnthony Joseph ReyesNo ratings yet

- Maternal Note 1Document34 pagesMaternal Note 1JAN REY LANADONo ratings yet

- OB 13 Infectious Disease in PregnancyDocument17 pagesOB 13 Infectious Disease in PregnancyJoher100% (1)

- Framework of MCNDocument3 pagesFramework of MCNAngelica JaneNo ratings yet

- Varicella NeonatalDocument5 pagesVaricella NeonatalTias FirdayantiNo ratings yet

- 1995 Congenital Cytomegalovirus InfectionDocument10 pages1995 Congenital Cytomegalovirus InfectionIndra T BudiantoNo ratings yet

- NCM 109 Gyne Supplemental Learning Material 1Document25 pagesNCM 109 Gyne Supplemental Learning Material 1Zack Skyler Guerrero AdzuaraNo ratings yet

- Micheletti2018 PDFDocument67 pagesMicheletti2018 PDFtriNo ratings yet

- Daftar PustakaDocument4 pagesDaftar PustakatriNo ratings yet

- Menopausal Symptoms and Surgical Complications After Opportunistic Bilateral Salpingectomy, A Register-Based Cohort StudyDocument10 pagesMenopausal Symptoms and Surgical Complications After Opportunistic Bilateral Salpingectomy, A Register-Based Cohort StudytriNo ratings yet

- PDF KBB 139 PDFDocument4 pagesPDF KBB 139 PDFtriNo ratings yet

- Coronary Arteri DiseaseDocument3 pagesCoronary Arteri DiseasetriNo ratings yet

- Myocardial Contractile Dispersion: A New Marker For The Severity of Cirrhosis?Document5 pagesMyocardial Contractile Dispersion: A New Marker For The Severity of Cirrhosis?triNo ratings yet

- JCVTR 11 79Document6 pagesJCVTR 11 79triNo ratings yet

- VBIED Attack July 31, 2007Document1 pageVBIED Attack July 31, 2007Rhonda NoldeNo ratings yet

- Job Hazard AnalysisDocument1 pageJob Hazard AnalysisZaul tatingNo ratings yet

- Artificial Intelligence in PharmacyDocument8 pagesArtificial Intelligence in PharmacyMeraNo ratings yet

- Wired For: Hit Play For SexDocument7 pagesWired For: Hit Play For SexPio Jian LumongsodNo ratings yet

- The History of The Big Bang TheoryDocument6 pagesThe History of The Big Bang Theorymay ann dimaanoNo ratings yet

- To, The Medical Superintendent, Services Hospital LahoreDocument1 pageTo, The Medical Superintendent, Services Hospital LahoreAfraz AliNo ratings yet

- Vespa S 125 3V Ie 150 3V Ie UPUTSTVODocument90 pagesVespa S 125 3V Ie 150 3V Ie UPUTSTVOdoughstoneNo ratings yet

- MCN KweenDocument4 pagesMCN KweenAngelo SigueNo ratings yet

- Autoconceito ShavelsonDocument15 pagesAutoconceito ShavelsonJuliana SchwarzNo ratings yet

- Board Question Paper - March 2023 - For Reprint Update - 641b040f4992cDocument4 pagesBoard Question Paper - March 2023 - For Reprint Update - 641b040f4992cSushan BhagatNo ratings yet

- Nanoengineered Silica-Properties PDFDocument18 pagesNanoengineered Silica-Properties PDFkevinNo ratings yet

- STOC03 (Emissions)Document20 pagesSTOC03 (Emissions)tungluongNo ratings yet

- Benzene - It'S Characteristics and Safety in Handling, Storing & TransportationDocument6 pagesBenzene - It'S Characteristics and Safety in Handling, Storing & TransportationEhab SaadNo ratings yet

- Thermocouple Calibration FurnaceDocument4 pagesThermocouple Calibration FurnaceAHMAD YAGHINo ratings yet

- Piping SpecificationDocument5 pagesPiping SpecificationShandi Hasnul FarizalNo ratings yet

- Towncall Rural Bank, Inc.: To Adjust Retirement Fund Based On Retirement Benefit Obligation BalanceDocument1 pageTowncall Rural Bank, Inc.: To Adjust Retirement Fund Based On Retirement Benefit Obligation BalanceJudith CastroNo ratings yet

- Emotional IntelligenceDocument43 pagesEmotional IntelligenceMelody ShekharNo ratings yet

- Hospital Management System: Dept. of CSE, GECRDocument30 pagesHospital Management System: Dept. of CSE, GECRYounus KhanNo ratings yet

- Tehri DamDocument31 pagesTehri DamVinayakJindalNo ratings yet

- Phason FHC1D User ManualDocument16 pagesPhason FHC1D User Manuale-ComfortUSANo ratings yet

- Columbus CEO Leaderboard - Home Healthcare AgenciesDocument1 pageColumbus CEO Leaderboard - Home Healthcare AgenciesDispatch MagazinesNo ratings yet

- Inorganic Chemistry HomeworkDocument3 pagesInorganic Chemistry HomeworkAlpNo ratings yet

- PintoDocument18 pagesPintosinagadianNo ratings yet

- 2nd Quarter PHILO ReviewerDocument1 page2nd Quarter PHILO ReviewerTrisha Joy Dela Cruz80% (5)

- Long Quiz Earth Sci 11Document2 pagesLong Quiz Earth Sci 11Jesha mae MagnoNo ratings yet

- SRHR - FGD With Young PeopleDocument3 pagesSRHR - FGD With Young PeopleMandira PrakashNo ratings yet