Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Coppola

Coppola

Uploaded by

Boris MarkovićCopyright:

Available Formats

You might also like

- Deed of Sale of PortionDocument3 pagesDeed of Sale of PortionTmanaligod100% (1)

- Italy - Research PaperDocument46 pagesItaly - Research PaperPatrick J. Wardwell100% (1)

- David Eggenberger - An Encyclopedia of Battles-Dover Publications (1985) PDFDocument543 pagesDavid Eggenberger - An Encyclopedia of Battles-Dover Publications (1985) PDFBoris MarkovićNo ratings yet

- ItalyDocument10 pagesItalyatontsuiNo ratings yet

- The Main Political Problems To Be SolvedDocument2 pagesThe Main Political Problems To Be SolvedRayne AribatoNo ratings yet

- COLONIALISMDocument2 pagesCOLONIALISMOscar MasindeNo ratings yet

- Presentation About ItalyDocument6 pagesPresentation About ItalyArcan Radu AlexandruNo ratings yet

- ItalyDocument3 pagesItalyneenasusanbabuNo ratings yet

- Calchi Novati - Italy and Africa - How To Forget ColonialismDocument18 pagesCalchi Novati - Italy and Africa - How To Forget ColonialismSara AlvarezNo ratings yet

- Italian Reproductive Impotence & Italian Agronomic Infecundity: Manifestations of ExtinctionDocument5 pagesItalian Reproductive Impotence & Italian Agronomic Infecundity: Manifestations of ExtinctionAnthony St. JohnNo ratings yet

- Position paper-MUNUCCLE 2022: Refugees) Des États !Document2 pagesPosition paper-MUNUCCLE 2022: Refugees) Des États !matNo ratings yet

- Sappor 2009 French Neo-Colonialism in Africa After Independence CFA MANIPULATIONDocument5 pagesSappor 2009 French Neo-Colonialism in Africa After Independence CFA MANIPULATIONAFRICANo ratings yet

- Milan Survival Guide: Italy Food & Drinks Lombardia How To Reach UsDocument10 pagesMilan Survival Guide: Italy Food & Drinks Lombardia How To Reach Us4lexxNo ratings yet

- CountriesDocument14 pagesCountriesN.No ratings yet

- Repubblica Italiana: Italy (Document2 pagesRepubblica Italiana: Italy (SophiaNo ratings yet

- Italy (: ListenDocument2 pagesItaly (: ListenSandruNo ratings yet

- The Crisis in French Foreign PolicyDocument27 pagesThe Crisis in French Foreign PolicyaekuzmichevaNo ratings yet

- Canaan HistoryDocument6 pagesCanaan Historymeskig17No ratings yet

- Italy and New Libya Between Continuity and Change: Arturo VarvelliDocument7 pagesItaly and New Libya Between Continuity and Change: Arturo VarvelliAnas ElgaudNo ratings yet

- Refugee Case Study Libyan Refugees To Italy 2011Document2 pagesRefugee Case Study Libyan Refugees To Italy 2011Sophie TalibNo ratings yet

- Cultural AnalysisDocument14 pagesCultural Analysisapi-643339832No ratings yet

- The Foot and The Horse's HeadDocument18 pagesThe Foot and The Horse's HeadJabulani MzaliyaNo ratings yet

- ItalyDocument16 pagesItalywenzercabatu05No ratings yet

- Reimagining Europe S Borderlands The Social and Cultural Impact of Undocumented Migrants On LampedusaDocument6 pagesReimagining Europe S Borderlands The Social and Cultural Impact of Undocumented Migrants On LampedusaMurat YamanNo ratings yet

- Countries 2Document8 pagesCountries 2N.No ratings yet

- Ib League Ethiopia UpdatedDocument7 pagesIb League Ethiopia UpdatedAgiabAberaNo ratings yet

- PopoDocument13 pagesPopogangsterstarxNo ratings yet

- Anglais: Langue Vivante I GroupeDocument3 pagesAnglais: Langue Vivante I GroupeFalilou Mbacke NdiayeNo ratings yet

- Emigrate2 Italy Guide by Emigrate2 and Halo FinancialDocument17 pagesEmigrate2 Italy Guide by Emigrate2 and Halo FinancialJulz RiosNo ratings yet

- Khu Vuc HocDocument2 pagesKhu Vuc HocTrịnh Phương ThảoNo ratings yet

- The Southern European AllianceDocument6 pagesThe Southern European AllianceAnthony St. JohnNo ratings yet

- Italy (: ListenDocument2 pagesItaly (: ListenAzreen Anis azmiNo ratings yet

- Contemporary Immigration DebatesDocument11 pagesContemporary Immigration DebatesPATRICIA MAE CABANANo ratings yet

- Italy Spain The Economist 2019Document3 pagesItaly Spain The Economist 2019Iván Iturbe CarbajalNo ratings yet

- The National System of Political Economy - Friedrich ListDocument281 pagesThe National System of Political Economy - Friedrich ListDouglas Ian Scott100% (1)

- Italy - WikipediaDocument75 pagesItaly - WikipediaMilosNo ratings yet

- Text Project MaltaDocument5 pagesText Project MaltaDianaTamayoNo ratings yet

- Berlin Conference Role CardsDocument4 pagesBerlin Conference Role CardsMichelle Silberberg100% (1)

- This Is Why Italy Is DyingDocument9 pagesThis Is Why Italy Is Dyingjorameugenio.eduNo ratings yet

- Italiana: Italy (Document2 pagesItaliana: Italy (Jordan MosesNo ratings yet

- Playing With Molecules The Italian Approach To LibyaDocument48 pagesPlaying With Molecules The Italian Approach To Libyascouby1No ratings yet

- Migration PresentationDocument3 pagesMigration Presentationapi-299122163100% (1)

- STRATFORSep 29 2011Document2 pagesSTRATFORSep 29 2011archaeopteryxgrNo ratings yet

- IRBR INGLES 3a Fase 2a EtapaDocument14 pagesIRBR INGLES 3a Fase 2a EtapaFrancisco OliveiraNo ratings yet

- France - Britannica Online EncyclopediaDocument103 pagesFrance - Britannica Online EncyclopediaLin MatsushitaNo ratings yet

- Italy - HistoryDocument16 pagesItaly - HistoryLily lolaNo ratings yet

- Scramble For Africa: Conquest of Africa, or The Rape of Africa, (1) (2) Was The InvasionDocument23 pagesScramble For Africa: Conquest of Africa, or The Rape of Africa, (1) (2) Was The InvasionoaifoiweuNo ratings yet

- The Coming Migration Out of Sub-Saharan Africa - National Review 081419Document11 pagesThe Coming Migration Out of Sub-Saharan Africa - National Review 081419longneck69No ratings yet

- ItalyDocument2 pagesItalyKaotiixNo ratings yet

- BefanaDocument8 pagesBefanaVictoria Isabel Gordillo SerranoNo ratings yet

- The North and South DivideDocument6 pagesThe North and South Dividelifetec2007No ratings yet

- FranceDocument3 pagesFrancesomebody idkNo ratings yet

- About CountriesDocument8 pagesAbout CountriesFABRIZIO DIAZNo ratings yet

- Unitary Parliamentary Republic: Italiana)Document2 pagesUnitary Parliamentary Republic: Italiana)Carmen PanzariNo ratings yet

- NLR 87-88 - Sept-Dec 1974 - Robin Blackburn - The Test in PortugalDocument42 pagesNLR 87-88 - Sept-Dec 1974 - Robin Blackburn - The Test in PortugalMarcelo NovelloNo ratings yet

- Causes of The Italo-Ethiopian War: The Italian Desire To Revenge Against EthiopiaDocument32 pagesCauses of The Italo-Ethiopian War: The Italian Desire To Revenge Against Ethiopiatariku ejiguNo ratings yet

- CRUEL BEAUTY The Self Portrait PaintingsDocument53 pagesCRUEL BEAUTY The Self Portrait PaintingsBoris MarkovićNo ratings yet

- American Foreign Relations ReconsideredDocument280 pagesAmerican Foreign Relations ReconsideredBoris MarkovićNo ratings yet

- CFR Annual Report 2002 0 PDFDocument128 pagesCFR Annual Report 2002 0 PDFBoris MarkovićNo ratings yet

- W. T. Stead and The Eastern Question (1875-1911) Or, How To Rouse England and Why? Stéphanie PrévostDocument28 pagesW. T. Stead and The Eastern Question (1875-1911) Or, How To Rouse England and Why? Stéphanie PrévostBoris MarkovićNo ratings yet

- Stanley I. Kutler - Dictionary of American History. Volume 3-Charles Scribner's Sons (2003) PDFDocument583 pagesStanley I. Kutler - Dictionary of American History. Volume 3-Charles Scribner's Sons (2003) PDFBoris MarkovićNo ratings yet

- Ottoman Fronts in The Balkans!: World War IDocument8 pagesOttoman Fronts in The Balkans!: World War IBoris MarkovićNo ratings yet

- The Naval War: The Women's Army Auxiliary CorpsDocument16 pagesThe Naval War: The Women's Army Auxiliary CorpsBoris MarkovićNo ratings yet

- 1923zimmern PDFDocument13 pages1923zimmern PDFBoris MarkovićNo ratings yet

- Italian Army 8 September 1943-Regio EserDocument15 pagesItalian Army 8 September 1943-Regio EserBoris Marković100% (1)

- 1939 HodenDocument17 pages1939 HodenBoris MarkovićNo ratings yet

- 1933 RooseveltDocument8 pages1933 RooseveltBoris MarkovićNo ratings yet

- 1934 GuntherDocument14 pages1934 GuntherBoris MarkovićNo ratings yet

- British Association For American Studies, Cambridge University Press Journal of American StudiesDocument31 pagesBritish Association For American Studies, Cambridge University Press Journal of American StudiesBoris MarkovićNo ratings yet

- The Urn NBN Si Doc-Uz1ni6qpDocument3 pagesThe Urn NBN Si Doc-Uz1ni6qpBoris MarkovićNo ratings yet

- Regional Office No. 02 (Cagayan Valley) : Epartment of DucationDocument3 pagesRegional Office No. 02 (Cagayan Valley) : Epartment of DucationRonnie Francisco TejanoNo ratings yet

- Ramirez vs. Vda. de Ramirez: VOL. 111, FEBRUARY 15, 1982 705Document8 pagesRamirez vs. Vda. de Ramirez: VOL. 111, FEBRUARY 15, 1982 705Angelie FloresNo ratings yet

- Operation Red Wings Research PaperDocument8 pagesOperation Red Wings Research Paperfys4gjmk100% (1)

- US Internal Revenue Service: I1028Document2 pagesUS Internal Revenue Service: I1028IRSNo ratings yet

- Open Letter From Women Leaders On Women's RightsDocument2 pagesOpen Letter From Women Leaders On Women's RightsThe Guardian100% (4)

- An Exceptional OperationDocument29 pagesAn Exceptional OperationGilman CooperNo ratings yet

- Explain The National ID System With The Risks of Data BreachDocument2 pagesExplain The National ID System With The Risks of Data BreachChristian Diacono PalerNo ratings yet

- Vargas v. RillorazaDocument14 pagesVargas v. RillorazaGia MordenoNo ratings yet

- Reading U11 ConflictDocument35 pagesReading U11 ConflictNhật Anh DoveNo ratings yet

- Miss Diwan ProposalDocument2 pagesMiss Diwan ProposalKent AdolfoNo ratings yet

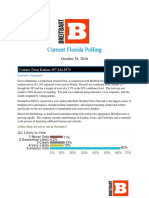

- FL Oct 27 v2Document12 pagesFL Oct 27 v2Breitbart NewsNo ratings yet

- Fisher v. University of Texas at Austin, Brief of Judicial Education Project in Support of PetitionerDocument23 pagesFisher v. University of Texas at Austin, Brief of Judicial Education Project in Support of PetitionerSteve DuvernayNo ratings yet

- Nari Adalat Accessible Alternative Justice Systems PDFDocument2 pagesNari Adalat Accessible Alternative Justice Systems PDFWWENo ratings yet

- May22.2015.docbarangay Krus Na Ligas in UP May Soon Be Sold To Qualified ResidentsDocument2 pagesMay22.2015.docbarangay Krus Na Ligas in UP May Soon Be Sold To Qualified Residentspribhor2No ratings yet

- The Gravest Crime Paolo BarnardDocument53 pagesThe Gravest Crime Paolo BarnardairaghidarioNo ratings yet

- Brit Exercise 4Document3 pagesBrit Exercise 4Princess0305No ratings yet

- San Pablo Manufacturing Corp V CirDocument2 pagesSan Pablo Manufacturing Corp V CirCai CarpioNo ratings yet

- March 13 PDFDocument72 pagesMarch 13 PDFjcpressdocsNo ratings yet

- Glossary of Diplomatic TermsDocument10 pagesGlossary of Diplomatic TermsAmosOkelloNo ratings yet

- Degree Attestation For Saudi ArabiaDocument4 pagesDegree Attestation For Saudi ArabiaZarrar KhanNo ratings yet

- Indian National Congress Formation - 14221760 - 2023 - 12 - 07 - 13 - 24Document3 pagesIndian National Congress Formation - 14221760 - 2023 - 12 - 07 - 13 - 24deekshaa685No ratings yet

- Title Deed Resoration Procedure - BarbadosDocument5 pagesTitle Deed Resoration Procedure - BarbadosKontrol100% (1)

- Declaration of IndependenceDocument3 pagesDeclaration of IndependenceKhadija SaeedNo ratings yet

- Letter About 243-02 Northern Boulevard ShelterDocument3 pagesLetter About 243-02 Northern Boulevard ShelterMaya KaufmanNo ratings yet

- KC Homicides As of July 21, 2009Document1 pageKC Homicides As of July 21, 2009geekstrNo ratings yet

- Application For Study Permit Made Outside of Canada: Validate Clear FormDocument4 pagesApplication For Study Permit Made Outside of Canada: Validate Clear FormLotfi BenNo ratings yet

- Econ10004 In-Tute (w4)Document2 pagesEcon10004 In-Tute (w4)Dan TaoNo ratings yet

- Benguet Corporation V DenrDocument2 pagesBenguet Corporation V DenrRalph VelosoNo ratings yet

- Nanak Institutions: Bus Pass Application FormDocument2 pagesNanak Institutions: Bus Pass Application FormAsjsjsjsNo ratings yet

Coppola

Coppola

Uploaded by

Boris MarkovićOriginal Description:

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Coppola

Coppola

Uploaded by

Boris MarkovićCopyright:

Available Formats

Italy in the Mediterranean

Author(s): Francesco Coppola

Source: Foreign Affairs, Vol. 1, No. 4 (Jun. 15, 1923), pp. 105-114

Published by: Council on Foreign Relations

Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/20028255 .

Accessed: 15/06/2014 04:37

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at .

http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp

.

JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of

content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms

of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org.

Council on Foreign Relations is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Foreign

Affairs.

http://www.jstor.org

This content downloaded from 195.78.108.40 on Sun, 15 Jun 2014 04:37:56 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

ITALY IN THE MEDITERRANEAN

By Francesco Coppola

I

IT IS impossible to understand the age-long need which has

always determined the general lines of Italian policy with

out taking account of the two principal factors which still

govern Italy's present and future?the growth of her population

and her geographical position in the Mediterranean.

In 1881 Italy's population was a little over 28 millions; in

1921 it had risen to 40 millions in Italy itself and about 8millions

abroad. Thus in forty years it has increased more than seventy

per cent. The area of Italy is 310,000 square kilometers; that

of the United States 9,400,000?or more than 30 times as much.

Consequently Italy has 129 inhabitants per square kilometer

while the United States has only 11. France?to take a Euro

pean example which in history and more closely

geography

resembles Italy?with a

population of 39 millions, has an area

of 551,000 square kilometers; in other words, she has a smaller

population but almost double the territory, and only 70 inhabi

tants per square kilometer. In spite of this, French colonial

over 12 million square kilometers and contain

possessions extend

50 million subjects, without counting Syria. On the other hand,

Italy's colonial possessions have an area of only two million

a half million

square kilometers and contain only one and

France is immensely rich in raw materials?iron,

subjects.

coal, phosphates?both at home and overseas; Italy proper and

the Italian colonies lack them almost entirely. If the comparison

as

be made with England, Italy is ten times badly off.

This entails many unfortunate

disadvantageous position

consequences for Italy. The first is that she finds herself unable

to provide her population with food, and that as far as concerns

raw materials such as iron, coal, cotton, and to a

phosphates,

certain extent wheat, she is in bondage to foreign lands. This

economic dependence inevitably leads to political dependence.

cannot to her

Secondly, Italy give employment growing popu

lation nor can she balance needed imports by developing her

own industries; for, in these indus

facing foreign competition,

tries labor under an initial disadvantage resulting from the

absence of raw materials and proper colonial markets. But the

most terrible consequence of all is the forced emigration. For

This content downloaded from 195.78.108.40 on Sun, 15 Jun 2014 04:37:56 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

io6 FOREIGN AFFAIRS

over of Italians have left

thirty years hundreds of thousands

their country annually; in 1913 the number was almost a million.

A stream of young blood flows uninterruptedly from the open

veins of Italy and spreads itself over the world, adding to the

power and wealth of foreign competitors and soon becoming irre

to Italy. Thus Italy is being stifled by the poverty

vocably lost

of her homeland and by her lack of colonial possessions; she is

to scatter her strength; a priori, she is not only dis

compelled

advantageous^ placed in the field of international competition

but is forced into a position of economic and political dependency.

She is, in short, faced with this major dilemma: either she must

conquer a position for herself proportionate to her needs and the

can offer suita

possessions of others, which implies colonies which

ble land to her children and proper raw materials to her industries;

or else she must forever renounce her as a

position great power,

even as an and thus herself to con

independent power, subject

tinued and accept a subordinate international status.

emigration

Now let us consider the second

factor governing Italy's de

geographical position in the Mediterranean.

velopment?her

Italy is the only European nation which is exclusively Mediter

ranean. The major development of the other great Mediter

ranean nations, France and is on the coasts of the free

Spain,

not touch the Mediterranean, nor does

Atlantic. England does

Germany. The interests of Italy, on the other hand, are wholly

in the Mediterranean; in fact she has no other means of com

munication with the outside world. Her territorial frontiers are

coast lines; and ranged along

insignificant in comparison with her

the former stand the Alps, across which travel is difficult and

Four-fifths of commerce is carried on?and

expensive. Italy's

cannot but be carried sea. Her and her

on?by imports exports,

means of emigration and expansion, her power and her freedom

are on the sea; her future, her very life itself, is on the sea. Her

of the Mediter

destiny is inseparably linked with the equilibrium

ranean. The

problem of the Mediterranean, together with that

of her colonial expansion, is therefore the great, the capital

historic problem for the Italy of today. There enter into it, as

factors of a single problem, the problem of liberty, the problem

of security, the national problem and the colonial problem.

II

Viewed thus in its fourfold aspect, how does this greatest of

Italian problems stand today?

This content downloaded from 195.78.108.40 on Sun, 15 Jun 2014 04:37:56 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

ITALY IN THE MEDITERRANEAN

From the point of view of liberty, England, though not really

aMediterranean power, holds Gibraltar and Suez, the two great

Mediterranean ports, controls its central straits by her possession

of Malta, and could, if she wished, cut Italy off completely from

communication with the outside world, could starve and stifle

her in a closed sea. She would have her at her mercy without

a

firing single shot.

From the point of view of security, Italy is compressed east,

west and south a semicircle of formidable naval

by bases?by

France with Toulon, Corsica and Biserta?by England with

Malta?by Greece with the Canal of Corfu?by Jugoslavia with

Cattaro and Sebenico.

From the national point of view, there still are preserved along

the entire Mediterranean coast the traces and traditions of

Imperial Rome, of Venice, Genoa, Pisa, Amalfi, Ragusa, and of

the Kingdoms of Naples and Sicily; and hundreds of thousands

of Italians, greatly outnumbering the children of any other

are

European race, scattered along the basin of the Mediter

ranean. But in Dalmatia are

they Jugoslav subjects; in Con

stantinople and Smyrna they do business under Turkish sover

in are under a French "mandate;" in Palestine

eignty; Syria they

and Egypt (50,000 in Egypt alone) they are under an English

over 150,000 in

protectorate; Algeria and Morocco have been

forcibly denationalized by the systematic absorption of France;

while over 100,000 more are desperately defending their nation

ality against this same absorption in Tunis, which owes its

fertility and prosperity entirely to their labors.

Finally, from the colonial point of view, the Italian peninsula,

projecting from Europe towards Africa, occupies the exact

center of the Mediterranean?the Mediterranean

geographic

which Rome once dominated, which she united beneath her laws

and sealed indelibly with her imperial imprint. Tunis, populated

with Italians, is only a few hours' journey from Sicily. Vast and

fertile Anatolia, rich in wheat and cotton and lumber and

minerals, with a not over three

population per square kilometer,

in a rudimentary state of civilization, lies only three days

distant from the Italian peninsula where the Italian people, one

of the oldest and most civilized in the world, with an

enterprising

expansionist instinct, is being stifled by the poverty and in

sufficiency of its national territory. And yet, from to

Tangiers

Alexandria, the entire African coast of the Mediterranean, with

This content downloaded from 195.78.108.40 on Sun, 15 Jun 2014 04:37:56 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

io8 FOREIGN AFFAIRS

the exception of the great Libyan desert, belongs either to

France or to the Mediterranean nation

England. Italy, par

excellence, is virtually excluded from the control of the Mediter

ranean; she is imprisoned and besieged in her own ocean.

The reasons for this absurd?and from now on intolerable?

situation are to be found in Italy's own past. It must first of all

be remembered that it was only after centuries of dissension and

servitude that Italy became a single state and only a little over

a ago that she became a European power; in other

half-century

words, she arrived at the international feast when the big world

plums, and especially the Mediterranean plums, had been

already grabbed up by the older, better established powers.

And, secondly, one must take into account the inevitable lack of

a

experience of newly formed state and its indifference to any

own borders, absorbed, as it must

thing outside its always be at

first, in strengthening its internal political, economic and

forces. Thus in 1881 the Italian Government did not

spiritual

know enough to forestall, as it undoubtedly could have done, the

French conquest of Tunis, and in 1882 it did not know enough

to grasp the importance of the English invitation to participate

in the occupation of Egypt. A third reason may be found in the

unsatisfactory results of the war of liberation, which had left

both the ethnic and geographic unity of Italy dangerously in

complete. As a result of this, Italy found herself limited in her

actions by the existence of two different but equally serious

obstacles. On the one hand, across the northern and

iniquitous

eastern boundaries, through the wide-opened gates of Trentino

menace

and Friuli, lay the perennial of Austrian invasion,

paralyzing Italy's freedom of action and forbidding her any real

political much less at overseas

liberty, any attempt expansion.

As proof of this it is enough to remember the proposed aggression

of the Austro-Hungarian general staff at the time of the Libyan

War. On the other hand, the silent but passionate longing for

Italian lands and Italian brothers still in foreign servitude con

centrated her every aspiration in a bitter Irredentism and so

to her power of expansion.

contributed paralyze Italy's will?and

Ill

To overcome these threefold to

obstacles, Italy needed

accomplish three things: to grow and to establish herself so

in her own estimation as to build up the determination

firmly

This content downloaded from 195.78.108.40 on Sun, 15 Jun 2014 04:37:56 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

ITALY IN THE MEDITERRANEAN

and the power for her necessary expansion; to assert, especially

against Austria, the indispensable premises of her national unity

and strategical security?that is to say, her moral liberty and her

political freedom; and to shatter the pre-existing international

balance of power in order to acquire in the world and particularly

in the Mediterranean a

position in keeping with her needs.

The first of these conditions?essentially a one?

subjective

was

speedily accomplished, and the meagre but hard won African

colonies were both its reward and measure. The contrast

between the feeble national will and lack of popular enthusiasm

which paralyzed the conduct of the Ethiopian War for Eritrea,

undertaken and directed by the solitary intelligence of Francesco

Crispi, and the young fervor of enthusiasm and pride which only

fifteen years later marked the declaration, the waging and the

winning of the Turkish War for the conquest of Libya, show very

clearly the rapid subjective development of Italy.

The European conflagration of 1914 offered her unexpectedly

an to attain the two essentially aims.

opportunity objective

The international equilibrium from which suffered was

Italy

It was a decisive moment in her She

suddenly upset. history.

had to choose between the tremendous peril and sacrifice of inter

vention, with its possibilities of greater power, and a fainthearted

neutrality, which meant resignation to her own inferiority.

Between mortal risk and quiet resignation Italy, inspired by her

expansionist instinct, did not hesitate; she chose the path of peril

and sacrifice for the sake of the future. Thus inspired, Italy of

her own free will entered the tremendous war; for this she en

dured, she fought, she won. In Italy?as indeed in other Entente

countries?the reasons of justice and right and humanity for

which the war against Germany was fought were a purely popular

ethical myth. Even though the irredentist reasons of Trentino

and Trieste were real motives, were but in some

yet they partial,

ways prejudicial, ones. In truth, although Italy entered the war

to combat the German at and to wrest her his

attempt hegemony

toric frontiers and the control of the Adriatic from Austria, Italy's

traditional instinct really aimed to secure the indispensable

modicum of security and freedom for Mediterranean expansion.

It was for this reason that in the fundamental pact of alliance

?the Treaty of London of April, 1915?Baron Sonnino stipu

lated for Italian colonial compensations in Africa in the event of

a a

Franco-English partition of the German colonies, and for

This content downloaded from 195.78.108.40 on Sun, 15 Jun 2014 04:37:56 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

no FOREIGN AFFAIRS

zone in Southern Anatolia in the event of Allied

corresponding

acquisitions in the Levant. It was also for this reason that, later

of a

on, when he got wind the complete plan of tripartite partition

of the Ottoman Empire (disloyally concluded in 1916 between

France, Russia, and England without the knowledge of Italy

who had been fighting for more than a year by their side,) he

forced the Allies to reopen the question and to give an adequate

share to Italy. The new treaty was discussed in April, 1917,

between Sonnino, Ribot and Lloyd George at Saint Jean de

Maurienne?from which it took its name?and was concluded

and signed in London in August of the same year. While leaving

Constantinople and the Caucasus, Armenia and part of the

Anatolian coast of the Black Sea to Russia, and Cilicia to

Syria

France, and and the over Arabia to

Mesopotamia protectorate

England, this treaty assigned to Italy southwestern Anatolia,

the whole Vilayet of Aidin with Smyrna, the whole Vilayet of

Konia with Adalia and a small part of the Vilayet of Adana.

Palestine was to be internationalized under the collective control

of the great allies. But this very treaty contained the poison

which was later to weaken it. The new clauses regarding Italy

depended upon Russian ratification; such ratification, doubtful

enough in April, 1917, when the revolution in Russia was begin

ning, became manifestly unobtainable by the following August

when the revolution was turning to Bolshevism. Shortly after

wards the Bolshevik catastrophe and the peace of Brest-Litovsk

eliminated Russia simultaneously from among the belligerents

and from among the great powers. In any event this

European

collapse (which, contrary to the terms of the original treaty, left

Italy to face alone the forces of the Austro-Hungarian Empire)

should have given her an added rather than a lesser claim upon

Allied Instead, even before the war was over, the

gratitude.

Allies hastened to avail themselves of the pretext of the absence

of Russia's signature to denounce the Treaty of Saint Jean de

Maurienne. This was particularly true of Mr. Lloyd George who

at all cost to western Anatolia to

wanted give Smyrna and

Greece, already selected him as the vassal and the instru

by

ment of eastern

England's policy.

Greece, indeed, guided by Venizelos who had been brought

back to Athens by French bayonets, did after three years of

was no

equivocal neutrality and when Allied victory longer in

doubt finally take the field. And in her few months of frontier

This content downloaded from 195.78.108.40 on Sun, 15 Jun 2014 04:37:56 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

ITALY IN THE MEDITERRANEAN

warfare against the Bulgars she may perhaps have lost 500 men

?or less than a thousandth part of Italy's losses. But Venizelos

knew how to flatter President Wilson by standing

as the cham

pion of the principle of nationality, of "the rights of small

nations;" he knew how to flatter France on the one

by posing

hand as the enemy of the "boche" Constantine, and on the other

as an obstacle to Italian

expansion; and above all he found grace

in English eyes by offering himself as a political mercenary of

the Turks and as a tool of British in

England against hegemony

the Levant. Thus it came about that in the spring of 1919

Lloyd George, taking advantage of the weakness and temporary

absence of Orlando and violating the Treaty of Saint Jean de

Maurienne and the Armistice of Mudros, was able to

arrange

that Smyrna and the surrounding neighborhood be given to

Greece. This was done with the full consent of Wilson, who,

absolutely ignorant of European and Mediterranean affairs,

allowed himself to be idealistic

blindly governed by impulses and

natural prejudices, and with the approbation of Clemenceau,

who was only too delighted to be able to "jouer un mauvais tour

? l'Italie." The Greeks occupied Smyrna and by sack and

massacre the first Turkish resistance, which later de

provoked

veloped into the great victorious Kemalist reaction.

In order not to be left out of everything, Italy thereupon

Scala Nova to the south of Sokia in the valley

occupied Smyrna,

of the Meander, and Adalia on the coast of Anatolia, whence de

tachments were sent into the interior as far as Konia. These

troops were everywhere acclaimed by the Turks as liberators.

But the Allies protested even this occupation, and

against

Tittoni, who succeeded Sonnino as head of the Italian delegation

at Paris, had to exert all his

eloquence in defending it. Not satis

fied with having deprived Italy of Smyrna?the biggest city, the

the center of all the

greatest port, railroads?Lloyd George forced

her to present the Dodecanese islands to Greece, who had never

possessed them. They had been acquired by Italy in the Libyan

War prior to the Great War, and were

definitely promised her in

the Treaty of London. Tittoni was weak enough to promise to

cede them over to Greece in the accord concluded with Venizelos

in 1919?which has since been denounced (1922). At the same

time the original outright partition of the Ottoman Empire

among the victors was changed by the Wilsonian formula into

"mandates;" was a "mandate" over

England given Mesopotamia

This content downloaded from 195.78.108.40 on Sun, 15 Jun 2014 04:37:56 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

112 FOREIGN AFFAIRS

and Palestine, France a "mandate" over Syria and Cilicia. Italy,

of should at least have been a "mandate"

deprived Smyrna, given

over most of Anatolia.

IV

We now reach the spring of 1920 and the Conference of San

Remo where the peace with Turkey, embodied later on in the

Treaty of S?vres, was drawn up. This treaty gave Greece

Smyrna and all of the extensive region of Aivali and Ephesus;

it gave France the mandate over

Syria, and England that over

and Palestine; alone was given nothing.

Mesopotamia Italy

one of her had The

Every political acquisitions disappeared.

Tripartite Agreement between Nitti, Lloyd George and Millerand

conceded a "privileged economic zone" to Italy (corresponding

to the cession of Cilicia to France) including the Vilayet of Konia

and the greater part of the Vilayet of Brusa?a zone without

ports or railroads, without either or

independent geographic

economic autonomy and very difficult of access. Greece, on the

other hand, received directions from the Entente, in spite of the

of Italy, to crush the Kemalist resistance by armed

opposition

force and to impose upon Turkey the execution of the Treaty of

S?vres. This absurd commission, which as Italy had foreseen

was quite out of to the military and economic strength

proportion

of the Greeks, uselessly prolonged a dreadful and bloody war,

in the catastrophe

brought about the fall of Venizelos and ended

of September, 1922, which was not a Greek defeat but also

only

an Allied defeat, a defeat of the West by the East.

As a result the Turks?whom Italy alone of the victorious

a

powers had always treated in friendly manner?to whom Italy

had held open the ports of Adalia and Scala Nova at a time

when the Anglo-Greeks and Franco-Armenians of Cilicia were

besieging them in the Sea of Marmora, the Black Sea and the

Italy alone had managed to have recognized as

Aegean?whom

to the London Convention of March,

belligerents and admitted

1921?these very Turks obstinately refused to accept the Tri

partite Accord, which guaranteed victorious Italy her last small

in the Levant. And thus it came about that the

advantage

Turks, encouraged by the growth of Pan-Islamic solidarity,

their alliance with the Soviet and the evident dissension within

the Entente produced by the Franklin-Bouillon peace, little by

little began to forget their benefactors and included even

Italy

This content downloaded from 195.78.108.40 on Sun, 15 Jun 2014 04:37:56 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

ITALY IN THE MEDITERRANEAN 113

in their growing anti-western xenophobia. This occurred just

as Italy was withdrawing her troops from Konia and Adalia and

finally to the Meander. So that at Lausanne not only was the

Accord no but the Turkish delegates

Tripartite longer mentioned

demanded the total abolition of the capitulations?the diplo

matic protection of foreign citizens in Turkey. This protection

is of special concern to Italy since her subjects inTurkey greatly

outnumber those of any other great power. Today the Turks

are even return of the little island of Castelorizo,

asking for the

which is victorious Italy's only remaining acquisition in theMediter

ranean. Even in Africa (if we except part of British Somaliland,

not yet turned over to her,) she has not

promised Italy but

obtained from France or England, despite the Treaty of London,

any compensation for the partition between these two powers of

the whole German Colonial Empire.

V

In spite of victory, then, Italy's position in the Mediterranean

has changed for the worse. It has changed for the worse as far

as her not

liberty is concerned, for England has only retained

Gibraltar and Suez and strengthened her strategic control of the

latter by acquiring the coast of Palestine and the great fortifi

cations of Haifa, but at Chanak and Gallipoli she has laid hold

of the Dardanelles, the third great Mediterranean port?and

heaven only knows when she will let go! Italy's position has

been adversely affected from the point of view of security, be

cause the naval bases of the eastern coast of the Adriatic are no

at least to a

longer in the hands of Austria, which belonged

alliance hostile to the group, but are

political Franco-English

now under the control of Jugoslavia and Greece, satellites

respectively of France and England. Italy's position is worse,

too, from the national point of view, for the Italians of Syria and

Palestine have passed under the control of France and England,

and the Italians in Turkey have lost even their capitulatory

protection. Her position is also more unfavorable from the

colonial point of view as she has had to reconquer Tripoli and

arms and because the to her

Cyrenaica by force of disproportion

needs increases with the growth of her population. And, finally,

her position grows more and more unsatisfactory from the point

of view of aMediterranean balance of power; for the new French

acquisition of and the new British acquisitions of Palestine

Syria

This content downloaded from 195.78.108.40 on Sun, 15 Jun 2014 04:37:56 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

ii4 FOREIGN AFFAIRS

and Mesopotamia are not balanced

by any corresponding gains

for Italy and have in consequence rendered the former Mediter

ranean status still more unfair and intolerable. This has been

due partly to the greed and intemperance of others, but also to

the innate weakness of Italian policy resulting from the profound

depression which existed in Italy during the four years following

the Great War, and particularly in 1920 and 1921.

But today Italy's internal condition (which is the really

decisive factor) has undergone a radical and definitive change.

Once more Italy has become conscious of her national and inter

national strength. She has realized that her victory was un

justly mutilated and that it is her right to retrieve it. She is

again fully conscious of her vital need for expansion and she is

deliberately determined to satisfy it. The political security given

by the possession of her natural frontiers and the virtual satis

faction of her irredentist claims, which the war has given, are

today finally recognized as the long awaited stepping-stone to the

solution of the great problem of the Mediterranean. Her

external problem is the same today as before the war: either to

or to

expand in the Mediterranean resign herself to being stifled

in it. But subjectively it has been solved, and solved forever;

to be stifled?and

Italy will not allow herself this inevitably

means that she will

expand. The problem is thus reversed. Its

solution is no longer up to Italy but to the other great Mediter

ranean powers; room for

they will either make Italy in the

Mediterranean or she will make it for herself?in spite of them

?against their wishes if need be.

Indeed, one has only to consider the last sixty years of Italian

sure of the future. Sixty years ago Italy did not

history to be

even exist she was but a mass of small communities,

politically;

more or less to a

power. she is a great

subject foreign Today

national state, victorious in the greatest war of history and fully

conscious of her own strength. Two formidable historic powers

?the temporal dominion of the Popes and the Austro-Hungarian

in her to bar her way.

Empire?have stood path and attempted

Italy has overthrown them one after the other. If any other

power should insist upon barring her way today, Italy will sooner

or later know how to force it aside also.

This content downloaded from 195.78.108.40 on Sun, 15 Jun 2014 04:37:56 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

You might also like

- Deed of Sale of PortionDocument3 pagesDeed of Sale of PortionTmanaligod100% (1)

- Italy - Research PaperDocument46 pagesItaly - Research PaperPatrick J. Wardwell100% (1)

- David Eggenberger - An Encyclopedia of Battles-Dover Publications (1985) PDFDocument543 pagesDavid Eggenberger - An Encyclopedia of Battles-Dover Publications (1985) PDFBoris MarkovićNo ratings yet

- ItalyDocument10 pagesItalyatontsuiNo ratings yet

- The Main Political Problems To Be SolvedDocument2 pagesThe Main Political Problems To Be SolvedRayne AribatoNo ratings yet

- COLONIALISMDocument2 pagesCOLONIALISMOscar MasindeNo ratings yet

- Presentation About ItalyDocument6 pagesPresentation About ItalyArcan Radu AlexandruNo ratings yet

- ItalyDocument3 pagesItalyneenasusanbabuNo ratings yet

- Calchi Novati - Italy and Africa - How To Forget ColonialismDocument18 pagesCalchi Novati - Italy and Africa - How To Forget ColonialismSara AlvarezNo ratings yet

- Italian Reproductive Impotence & Italian Agronomic Infecundity: Manifestations of ExtinctionDocument5 pagesItalian Reproductive Impotence & Italian Agronomic Infecundity: Manifestations of ExtinctionAnthony St. JohnNo ratings yet

- Position paper-MUNUCCLE 2022: Refugees) Des États !Document2 pagesPosition paper-MUNUCCLE 2022: Refugees) Des États !matNo ratings yet

- Sappor 2009 French Neo-Colonialism in Africa After Independence CFA MANIPULATIONDocument5 pagesSappor 2009 French Neo-Colonialism in Africa After Independence CFA MANIPULATIONAFRICANo ratings yet

- Milan Survival Guide: Italy Food & Drinks Lombardia How To Reach UsDocument10 pagesMilan Survival Guide: Italy Food & Drinks Lombardia How To Reach Us4lexxNo ratings yet

- CountriesDocument14 pagesCountriesN.No ratings yet

- Repubblica Italiana: Italy (Document2 pagesRepubblica Italiana: Italy (SophiaNo ratings yet

- Italy (: ListenDocument2 pagesItaly (: ListenSandruNo ratings yet

- The Crisis in French Foreign PolicyDocument27 pagesThe Crisis in French Foreign PolicyaekuzmichevaNo ratings yet

- Canaan HistoryDocument6 pagesCanaan Historymeskig17No ratings yet

- Italy and New Libya Between Continuity and Change: Arturo VarvelliDocument7 pagesItaly and New Libya Between Continuity and Change: Arturo VarvelliAnas ElgaudNo ratings yet

- Refugee Case Study Libyan Refugees To Italy 2011Document2 pagesRefugee Case Study Libyan Refugees To Italy 2011Sophie TalibNo ratings yet

- Cultural AnalysisDocument14 pagesCultural Analysisapi-643339832No ratings yet

- The Foot and The Horse's HeadDocument18 pagesThe Foot and The Horse's HeadJabulani MzaliyaNo ratings yet

- ItalyDocument16 pagesItalywenzercabatu05No ratings yet

- Reimagining Europe S Borderlands The Social and Cultural Impact of Undocumented Migrants On LampedusaDocument6 pagesReimagining Europe S Borderlands The Social and Cultural Impact of Undocumented Migrants On LampedusaMurat YamanNo ratings yet

- Countries 2Document8 pagesCountries 2N.No ratings yet

- Ib League Ethiopia UpdatedDocument7 pagesIb League Ethiopia UpdatedAgiabAberaNo ratings yet

- PopoDocument13 pagesPopogangsterstarxNo ratings yet

- Anglais: Langue Vivante I GroupeDocument3 pagesAnglais: Langue Vivante I GroupeFalilou Mbacke NdiayeNo ratings yet

- Emigrate2 Italy Guide by Emigrate2 and Halo FinancialDocument17 pagesEmigrate2 Italy Guide by Emigrate2 and Halo FinancialJulz RiosNo ratings yet

- Khu Vuc HocDocument2 pagesKhu Vuc HocTrịnh Phương ThảoNo ratings yet

- The Southern European AllianceDocument6 pagesThe Southern European AllianceAnthony St. JohnNo ratings yet

- Italy (: ListenDocument2 pagesItaly (: ListenAzreen Anis azmiNo ratings yet

- Contemporary Immigration DebatesDocument11 pagesContemporary Immigration DebatesPATRICIA MAE CABANANo ratings yet

- Italy Spain The Economist 2019Document3 pagesItaly Spain The Economist 2019Iván Iturbe CarbajalNo ratings yet

- The National System of Political Economy - Friedrich ListDocument281 pagesThe National System of Political Economy - Friedrich ListDouglas Ian Scott100% (1)

- Italy - WikipediaDocument75 pagesItaly - WikipediaMilosNo ratings yet

- Text Project MaltaDocument5 pagesText Project MaltaDianaTamayoNo ratings yet

- Berlin Conference Role CardsDocument4 pagesBerlin Conference Role CardsMichelle Silberberg100% (1)

- This Is Why Italy Is DyingDocument9 pagesThis Is Why Italy Is Dyingjorameugenio.eduNo ratings yet

- Italiana: Italy (Document2 pagesItaliana: Italy (Jordan MosesNo ratings yet

- Playing With Molecules The Italian Approach To LibyaDocument48 pagesPlaying With Molecules The Italian Approach To Libyascouby1No ratings yet

- Migration PresentationDocument3 pagesMigration Presentationapi-299122163100% (1)

- STRATFORSep 29 2011Document2 pagesSTRATFORSep 29 2011archaeopteryxgrNo ratings yet

- IRBR INGLES 3a Fase 2a EtapaDocument14 pagesIRBR INGLES 3a Fase 2a EtapaFrancisco OliveiraNo ratings yet

- France - Britannica Online EncyclopediaDocument103 pagesFrance - Britannica Online EncyclopediaLin MatsushitaNo ratings yet

- Italy - HistoryDocument16 pagesItaly - HistoryLily lolaNo ratings yet

- Scramble For Africa: Conquest of Africa, or The Rape of Africa, (1) (2) Was The InvasionDocument23 pagesScramble For Africa: Conquest of Africa, or The Rape of Africa, (1) (2) Was The InvasionoaifoiweuNo ratings yet

- The Coming Migration Out of Sub-Saharan Africa - National Review 081419Document11 pagesThe Coming Migration Out of Sub-Saharan Africa - National Review 081419longneck69No ratings yet

- ItalyDocument2 pagesItalyKaotiixNo ratings yet

- BefanaDocument8 pagesBefanaVictoria Isabel Gordillo SerranoNo ratings yet

- The North and South DivideDocument6 pagesThe North and South Dividelifetec2007No ratings yet

- FranceDocument3 pagesFrancesomebody idkNo ratings yet

- About CountriesDocument8 pagesAbout CountriesFABRIZIO DIAZNo ratings yet

- Unitary Parliamentary Republic: Italiana)Document2 pagesUnitary Parliamentary Republic: Italiana)Carmen PanzariNo ratings yet

- NLR 87-88 - Sept-Dec 1974 - Robin Blackburn - The Test in PortugalDocument42 pagesNLR 87-88 - Sept-Dec 1974 - Robin Blackburn - The Test in PortugalMarcelo NovelloNo ratings yet

- Causes of The Italo-Ethiopian War: The Italian Desire To Revenge Against EthiopiaDocument32 pagesCauses of The Italo-Ethiopian War: The Italian Desire To Revenge Against Ethiopiatariku ejiguNo ratings yet

- CRUEL BEAUTY The Self Portrait PaintingsDocument53 pagesCRUEL BEAUTY The Self Portrait PaintingsBoris MarkovićNo ratings yet

- American Foreign Relations ReconsideredDocument280 pagesAmerican Foreign Relations ReconsideredBoris MarkovićNo ratings yet

- CFR Annual Report 2002 0 PDFDocument128 pagesCFR Annual Report 2002 0 PDFBoris MarkovićNo ratings yet

- W. T. Stead and The Eastern Question (1875-1911) Or, How To Rouse England and Why? Stéphanie PrévostDocument28 pagesW. T. Stead and The Eastern Question (1875-1911) Or, How To Rouse England and Why? Stéphanie PrévostBoris MarkovićNo ratings yet

- Stanley I. Kutler - Dictionary of American History. Volume 3-Charles Scribner's Sons (2003) PDFDocument583 pagesStanley I. Kutler - Dictionary of American History. Volume 3-Charles Scribner's Sons (2003) PDFBoris MarkovićNo ratings yet

- Ottoman Fronts in The Balkans!: World War IDocument8 pagesOttoman Fronts in The Balkans!: World War IBoris MarkovićNo ratings yet

- The Naval War: The Women's Army Auxiliary CorpsDocument16 pagesThe Naval War: The Women's Army Auxiliary CorpsBoris MarkovićNo ratings yet

- 1923zimmern PDFDocument13 pages1923zimmern PDFBoris MarkovićNo ratings yet

- Italian Army 8 September 1943-Regio EserDocument15 pagesItalian Army 8 September 1943-Regio EserBoris Marković100% (1)

- 1939 HodenDocument17 pages1939 HodenBoris MarkovićNo ratings yet

- 1933 RooseveltDocument8 pages1933 RooseveltBoris MarkovićNo ratings yet

- 1934 GuntherDocument14 pages1934 GuntherBoris MarkovićNo ratings yet

- British Association For American Studies, Cambridge University Press Journal of American StudiesDocument31 pagesBritish Association For American Studies, Cambridge University Press Journal of American StudiesBoris MarkovićNo ratings yet

- The Urn NBN Si Doc-Uz1ni6qpDocument3 pagesThe Urn NBN Si Doc-Uz1ni6qpBoris MarkovićNo ratings yet

- Regional Office No. 02 (Cagayan Valley) : Epartment of DucationDocument3 pagesRegional Office No. 02 (Cagayan Valley) : Epartment of DucationRonnie Francisco TejanoNo ratings yet

- Ramirez vs. Vda. de Ramirez: VOL. 111, FEBRUARY 15, 1982 705Document8 pagesRamirez vs. Vda. de Ramirez: VOL. 111, FEBRUARY 15, 1982 705Angelie FloresNo ratings yet

- Operation Red Wings Research PaperDocument8 pagesOperation Red Wings Research Paperfys4gjmk100% (1)

- US Internal Revenue Service: I1028Document2 pagesUS Internal Revenue Service: I1028IRSNo ratings yet

- Open Letter From Women Leaders On Women's RightsDocument2 pagesOpen Letter From Women Leaders On Women's RightsThe Guardian100% (4)

- An Exceptional OperationDocument29 pagesAn Exceptional OperationGilman CooperNo ratings yet

- Explain The National ID System With The Risks of Data BreachDocument2 pagesExplain The National ID System With The Risks of Data BreachChristian Diacono PalerNo ratings yet

- Vargas v. RillorazaDocument14 pagesVargas v. RillorazaGia MordenoNo ratings yet

- Reading U11 ConflictDocument35 pagesReading U11 ConflictNhật Anh DoveNo ratings yet

- Miss Diwan ProposalDocument2 pagesMiss Diwan ProposalKent AdolfoNo ratings yet

- FL Oct 27 v2Document12 pagesFL Oct 27 v2Breitbart NewsNo ratings yet

- Fisher v. University of Texas at Austin, Brief of Judicial Education Project in Support of PetitionerDocument23 pagesFisher v. University of Texas at Austin, Brief of Judicial Education Project in Support of PetitionerSteve DuvernayNo ratings yet

- Nari Adalat Accessible Alternative Justice Systems PDFDocument2 pagesNari Adalat Accessible Alternative Justice Systems PDFWWENo ratings yet

- May22.2015.docbarangay Krus Na Ligas in UP May Soon Be Sold To Qualified ResidentsDocument2 pagesMay22.2015.docbarangay Krus Na Ligas in UP May Soon Be Sold To Qualified Residentspribhor2No ratings yet

- The Gravest Crime Paolo BarnardDocument53 pagesThe Gravest Crime Paolo BarnardairaghidarioNo ratings yet

- Brit Exercise 4Document3 pagesBrit Exercise 4Princess0305No ratings yet

- San Pablo Manufacturing Corp V CirDocument2 pagesSan Pablo Manufacturing Corp V CirCai CarpioNo ratings yet

- March 13 PDFDocument72 pagesMarch 13 PDFjcpressdocsNo ratings yet

- Glossary of Diplomatic TermsDocument10 pagesGlossary of Diplomatic TermsAmosOkelloNo ratings yet

- Degree Attestation For Saudi ArabiaDocument4 pagesDegree Attestation For Saudi ArabiaZarrar KhanNo ratings yet

- Indian National Congress Formation - 14221760 - 2023 - 12 - 07 - 13 - 24Document3 pagesIndian National Congress Formation - 14221760 - 2023 - 12 - 07 - 13 - 24deekshaa685No ratings yet

- Title Deed Resoration Procedure - BarbadosDocument5 pagesTitle Deed Resoration Procedure - BarbadosKontrol100% (1)

- Declaration of IndependenceDocument3 pagesDeclaration of IndependenceKhadija SaeedNo ratings yet

- Letter About 243-02 Northern Boulevard ShelterDocument3 pagesLetter About 243-02 Northern Boulevard ShelterMaya KaufmanNo ratings yet

- KC Homicides As of July 21, 2009Document1 pageKC Homicides As of July 21, 2009geekstrNo ratings yet

- Application For Study Permit Made Outside of Canada: Validate Clear FormDocument4 pagesApplication For Study Permit Made Outside of Canada: Validate Clear FormLotfi BenNo ratings yet

- Econ10004 In-Tute (w4)Document2 pagesEcon10004 In-Tute (w4)Dan TaoNo ratings yet

- Benguet Corporation V DenrDocument2 pagesBenguet Corporation V DenrRalph VelosoNo ratings yet

- Nanak Institutions: Bus Pass Application FormDocument2 pagesNanak Institutions: Bus Pass Application FormAsjsjsjsNo ratings yet