Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Articulo Yang

Articulo Yang

Uploaded by

Alekhine Cubas MarinaCopyright:

You might also like

- Biology Investigatory ProjectDocument41 pagesBiology Investigatory Projectsubitha77% (139)

- Atrazine Contamination of Drinking Water and Adverse Birth Outcomes in Community Water Systems With Elevated Atrazine in Ohio, 2006-2008Document14 pagesAtrazine Contamination of Drinking Water and Adverse Birth Outcomes in Community Water Systems With Elevated Atrazine in Ohio, 2006-2008Instituto Pablo JamilkNo ratings yet

- Literature Review of Water Treatment ProcessDocument6 pagesLiterature Review of Water Treatment Processc5r0qjcf100% (1)

- Determinants of Implementation of County Water and Sanitation Programme in Maseno Division of Kisumu West SubCounty, Kisumu County, KenyaDocument15 pagesDeterminants of Implementation of County Water and Sanitation Programme in Maseno Division of Kisumu West SubCounty, Kisumu County, KenyajournalNo ratings yet

- Literature Review On Drinking Water TreatmentDocument5 pagesLiterature Review On Drinking Water Treatmentafmabbpoksbfdp100% (1)

- Jurnal Ikmas 1Document10 pagesJurnal Ikmas 1ApriliasBMNo ratings yet

- Pnaaq 815Document88 pagesPnaaq 815benjoscoliNo ratings yet

- Water TanzaniaDocument6 pagesWater TanzaniaElite Cleaning ProductsNo ratings yet

- Research Paper On Drinking Water Quality in PakistanDocument6 pagesResearch Paper On Drinking Water Quality in Pakistanafeawckew100% (1)

- Water and Sanitation Thesis TopicsDocument7 pagesWater and Sanitation Thesis Topicsshannongutierrezcorpuschristi100% (2)

- Dissertation Water QualityDocument4 pagesDissertation Water QualityBestWriteMyPaperWebsiteUK100% (1)

- Solomon2020 Article EffectOfHouseholdWaterTreatmenDocument13 pagesSolomon2020 Article EffectOfHouseholdWaterTreatmenSiti lestarinurhamidahNo ratings yet

- An Assessment of Drinking-Water Quality Post-Haiyan: Field Investigation ReportDocument5 pagesAn Assessment of Drinking-Water Quality Post-Haiyan: Field Investigation ReportAhmed Mohamed Shawky NegmNo ratings yet

- Impact of Poorly Maintained Waste Water and Sewage Treatment Plants Lessons From South AfricaDocument16 pagesImpact of Poorly Maintained Waste Water and Sewage Treatment Plants Lessons From South AfricaMark EliasNo ratings yet

- Parasitological and Nutritional AssessmeDocument9 pagesParasitological and Nutritional AssessmezeitastirNo ratings yet

- Wright 2006Document9 pagesWright 2006Nermeen ElmelegaeNo ratings yet

- Final Thesis2023Document17 pagesFinal Thesis2023rueNo ratings yet

- My Published ProjectDocument10 pagesMy Published ProjectIsrael ApehNo ratings yet

- The Treatment of Rainwater For Potable Use: General Manager, Sales & Marketing, Davey Water ProductsDocument7 pagesThe Treatment of Rainwater For Potable Use: General Manager, Sales & Marketing, Davey Water Productsmohammad yaseenNo ratings yet

- 2010 Maternal and Fetal Exposure To Four Carcinogenic Environmental Metals - Huai Guan Et Al.Document8 pages2010 Maternal and Fetal Exposure To Four Carcinogenic Environmental Metals - Huai Guan Et Al.Fabricio Martínez100% (1)

- 1 s2.0 S2666535222000994 MainDocument9 pages1 s2.0 S2666535222000994 MainDea AmandaNo ratings yet

- Holm Et Al. 2016 Achieving The Sustainable Development Goals - A Case Study of The Complexity of Water Quality Health Risk 1Document9 pagesHolm Et Al. 2016 Achieving The Sustainable Development Goals - A Case Study of The Complexity of Water Quality Health Risk 1EddiemtongaNo ratings yet

- Environmental Predictors of Diarrhoeal Infection For Rural andDocument12 pagesEnvironmental Predictors of Diarrhoeal Infection For Rural andrahamansyahilhamNo ratings yet

- Rural Drinking Water at Supply and Household Levels: Quality and ManagementDocument10 pagesRural Drinking Water at Supply and Household Levels: Quality and ManagementEdukondalu BNo ratings yet

- Thesis Rainwater HarvestingDocument6 pagesThesis Rainwater HarvestingScott Donald100% (2)

- Review of Related LiteratureDocument3 pagesReview of Related LiteratureYNA ANGELA ACERO GAMANANo ratings yet

- Jurnal DMT2Document10 pagesJurnal DMT2Ida Ayu DhitayoniNo ratings yet

- Literature Review On Water Supply and SanitationDocument12 pagesLiterature Review On Water Supply and Sanitationgw163ckj100% (1)

- Risk Perception2Document11 pagesRisk Perception2GSPNo ratings yet

- Drinking WaterDocument20 pagesDrinking Watergreskpremium8No ratings yet

- Sage Publications, Inc., Association of Schools of Public Health Public Health Reports (1896-1970)Document26 pagesSage Publications, Inc., Association of Schools of Public Health Public Health Reports (1896-1970)Asniza AbasNo ratings yet

- Occurrence and Health Risk Assessment of Pharmaceutical and Personal Care Products (PPCPS) in Tap Water of ShanghaiDocument8 pagesOccurrence and Health Risk Assessment of Pharmaceutical and Personal Care Products (PPCPS) in Tap Water of ShanghaiTiago TorresNo ratings yet

- Bullwho00048 0043Document13 pagesBullwho00048 0043christ.wong012001No ratings yet

- Water Management Literature ReviewDocument4 pagesWater Management Literature Reviewafmzmxkayjyoso100% (1)

- Impact of Acces To Water and SanitationDocument14 pagesImpact of Acces To Water and Sanitationnur aisyahNo ratings yet

- Artículo LupitaDocument12 pagesArtículo LupitaAna MoralesNo ratings yet

- ClorinationDocument10 pagesClorinationSandeep_AjmireNo ratings yet

- Hepatite A 2Document8 pagesHepatite A 2escabreraNo ratings yet

- Literature Review WaterDocument4 pagesLiterature Review Waterc5pnw26s100% (1)

- capstone-LRRDocument15 pagescapstone-LRRronskierelenteNo ratings yet

- Journal Pone 0012613Document10 pagesJournal Pone 0012613Sena AniakuNo ratings yet

- 6) Raphael C. Mkwate, 2016Document27 pages6) Raphael C. Mkwate, 2016yesuf4assefaNo ratings yet

- A National Wastewater Monitoring Program For A Better Understanding ofDocument12 pagesA National Wastewater Monitoring Program For A Better Understanding ofValentina Rico BermudezNo ratings yet

- AJTMHJuly2014190 FullDocument9 pagesAJTMHJuly2014190 FullRizki WahyuniNo ratings yet

- 10.1007@s12403 019 00299 8Document7 pages10.1007@s12403 019 00299 8mohamed hiflyNo ratings yet

- Ebsco Fulltext 2024 03 20Document18 pagesEbsco Fulltext 2024 03 20api-733654444No ratings yet

- Potability of Water Sources in Northern CebuDocument33 pagesPotability of Water Sources in Northern CebuDelfa CastillaNo ratings yet

- Three Key Factors in Uencing The Bacterial Contamination of Dental Unit Waterlines: A 6-Year Survey From 2012 To 2017Document8 pagesThree Key Factors in Uencing The Bacterial Contamination of Dental Unit Waterlines: A 6-Year Survey From 2012 To 2017khamilatusyNo ratings yet

- Jurnal Sanitasi 2Document13 pagesJurnal Sanitasi 2andhikaadyatmaaNo ratings yet

- 1 s2.0 S0959378020307317 MainextDocument15 pages1 s2.0 S0959378020307317 MainextSiddhant jainNo ratings yet

- 10 1 1 559 175 PDFDocument15 pages10 1 1 559 175 PDFEldhaNo ratings yet

- 12 Economic Toll of PollutiDocument9 pages12 Economic Toll of PollutiEdgarvitNo ratings yet

- Assignment 2 FinalDocument8 pagesAssignment 2 FinalJameson KaundaNo ratings yet

- Term PaperDocument3 pagesTerm Paperdavinceaaron3No ratings yet

- Microbial and Endotoxin Contamination in Water and Dialysate in The Central United StatesDocument4 pagesMicrobial and Endotoxin Contamination in Water and Dialysate in The Central United StatesfarhanomeNo ratings yet

- Water Contamination and The Rate of Infections For Water BirthsDocument16 pagesWater Contamination and The Rate of Infections For Water Birthsmagallanes36No ratings yet

- 3 Articles in ChemistryDocument15 pages3 Articles in ChemistryAngeline OsicNo ratings yet

- Piped Water Access, Child Health and The Complementary Role of Education-Panel Data Evidence From South AfricaDocument20 pagesPiped Water Access, Child Health and The Complementary Role of Education-Panel Data Evidence From South AfricaKhánh ThươngNo ratings yet

- Water Literature ReviewDocument6 pagesWater Literature Reviewdafobrrif100% (1)

- De Soto 1989 North 1990: The Quarterly Journal of Economics (2011) 126, 145-205. Doi:10.1093/qje/qjq010Document61 pagesDe Soto 1989 North 1990: The Quarterly Journal of Economics (2011) 126, 145-205. Doi:10.1093/qje/qjq010pgpsm09030No ratings yet

- The Paradox of Water: The Science and Policy of Safe Drinking WaterFrom EverandThe Paradox of Water: The Science and Policy of Safe Drinking WaterNo ratings yet

- HomatropinDocument11 pagesHomatropinDesma ParayuNo ratings yet

- Resume SampleDocument3 pagesResume Samplebibs_caigas37440% (1)

- Placenta Previa Journal KristalDocument23 pagesPlacenta Previa Journal KristalGabbyNo ratings yet

- Perioperative Anticoagulation Bridging Guideline PostedDocument6 pagesPerioperative Anticoagulation Bridging Guideline PostedNuc Alexandru100% (1)

- Treatment of Constipation in Older Adult AAFPDocument8 pagesTreatment of Constipation in Older Adult AAFPTom KirklandNo ratings yet

- Accoucheurs ManualDocument37 pagesAccoucheurs ManualDrRenu Jain100% (1)

- Ab-Ark Benefit Packages (Private)Document66 pagesAb-Ark Benefit Packages (Private)raamki_99No ratings yet

- 01 Application (Permit To Construct)Document1 page01 Application (Permit To Construct)jherica baltazar100% (1)

- Calculo HGTDocument4 pagesCalculo HGTNestor Mendoza ElíasNo ratings yet

- Newyork-Presbyterian: Morgan Stanley Children'S HospitalDocument41 pagesNewyork-Presbyterian: Morgan Stanley Children'S HospitalTmanoj PraveenNo ratings yet

- Gestational Diabetes - On Broadening The DiagnosisDocument2 pagesGestational Diabetes - On Broadening The DiagnosisWillians ReyesNo ratings yet

- 2010 Era Journal Rank List PDFDocument904 pages2010 Era Journal Rank List PDFHassen M OuakkadNo ratings yet

- Instrument Separation Analysis of Multi-Used Protaper Universal Rotary System During Root Canal TherapyDocument6 pagesInstrument Separation Analysis of Multi-Used Protaper Universal Rotary System During Root Canal TherapyShoaib YounusNo ratings yet

- Day 2 Maternal Fetal Triage Index ToolDocument21 pagesDay 2 Maternal Fetal Triage Index ToolponekNo ratings yet

- English in Nursing - Rheynanda (2011316059)Document3 pagesEnglish in Nursing - Rheynanda (2011316059)Rhey RYNNo ratings yet

- A ObstetricsDocument87 pagesA ObstetricsGeraldine PatayanNo ratings yet

- Gynecological ExaminationDocument20 pagesGynecological Examinationwahyu kijang ramadhanNo ratings yet

- Marijuana Use and Breastfeeding PDFDocument7 pagesMarijuana Use and Breastfeeding PDFmdbackesNo ratings yet

- Hospital ManagementDocument26 pagesHospital Managementsanjib beraNo ratings yet

- EHAQ 4th Cycle Audit Tool Final Feb.10-2022Document51 pagesEHAQ 4th Cycle Audit Tool Final Feb.10-2022Michael Gebreamlak100% (1)

- A Report On Summer Posting AT Jag Pravesh Chandra HospitalDocument25 pagesA Report On Summer Posting AT Jag Pravesh Chandra HospitalDeepti KukretiNo ratings yet

- Evaluation of Guaifenesin-Ketamine-Xylazine and Diazepam-Ketamine-Xylazine Triple Drip For Gelding in EquinesDocument5 pagesEvaluation of Guaifenesin-Ketamine-Xylazine and Diazepam-Ketamine-Xylazine Triple Drip For Gelding in Equinessanjeev pitlawarNo ratings yet

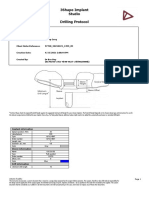

- 3shape Implant Studio Drilling Protocol: Contact InformationDocument2 pages3shape Implant Studio Drilling Protocol: Contact Informationnha khoa NHƯ NGỌCNo ratings yet

- Advancing Partners & Communities: Health Facility Assessment ToolDocument44 pagesAdvancing Partners & Communities: Health Facility Assessment ToolSuhailAlakhliNo ratings yet

- The Background of The Plastic Surgeon by Dr. Jay Calvert.Document2 pagesThe Background of The Plastic Surgeon by Dr. Jay Calvert.Bentzen94IpsenNo ratings yet

- Mindray: Expanding The Envelope of Performance and FlexibilityDocument8 pagesMindray: Expanding The Envelope of Performance and FlexibilityLeeNo ratings yet

- ReferenceDocument4 pagesReferenceStephani LeticiaNo ratings yet

- Ramos V CADocument3 pagesRamos V CAboomonyou100% (1)

- Mitral Valve Repair Using Robotic Technology: Safe, Effective, and DurableDocument5 pagesMitral Valve Repair Using Robotic Technology: Safe, Effective, and DurablewkwkwNo ratings yet

Articulo Yang

Articulo Yang

Uploaded by

Alekhine Cubas MarinaOriginal Description:

Copyright

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Articulo Yang

Articulo Yang

Uploaded by

Alekhine Cubas MarinaCopyright:

Articles

Association between Chlorination of Drinking Water and Adverse Pregnancy

Outcome in Taiwan

Chun-Yuh Yang,1 Bi-Hua Cheng,2 Shang-Shyue Tsai,1 Trong-Neng Wu,1 Meng-Chiao Lin, and Kuo-Cherng Lin4

'College of Health Science, Kaohsiung Medical University, Kaohsiung City, Taiwan; 2Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology,

Kaohsiung Chang-Gung; Memorial Hospital, Kaohsiung County, Taiwan; 3Department of Health, Kaohsiung City Government,

Kaohsiung City, Taiwan; 4Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Kaohsiung Medical University, Kaohsiung City, Taiwan

of the municipality population was served by

Chlorination has been the major means of disinfecting drinking water in Taiwan. The use of chlorinated water (i.e., > 95% of the resi-

chlorinated water has been hypothesized to lead to several adverse birth outcomes, incuding low dents obtained their drinking water from

birth weight and preterm delivery. We performed a study to exaine the relationship between the unchlorinated water sources). In all, 15

use of chlorinated water and adverse birth outcomes in Taiwan. The study areas induded 14 municipalities satisfied this criterion. These

chlorinating municipalities (CHMs), which were defined as municipalities in which > 90% ofthe 15 NCHMs provided a unique opportunity

municpal population was served by chlorinated water, and 14 matched nonchlorinatn munici- to investigate the issue of chlorination. To

palities (NCHMs), defined as municipalities in which < 5% of the municipal population is served take into account the possible confounding

by chlorinated water. The CHMs and NCHMs were similar to one another in terms of level of effect resulting from differing levels of

urbanization and sociodemographic characteristics. The study population comprised 18,025 urbanization, the urbanization level of the

women residing in the 28 municipalities who had a first parity singleton birth between 1 January nonchlorinating municipalities should be the

1994 and 31 December 1996 and for which complete information on materal age, education, same as that of the chlorinating municipali-

gestational age, birth weight, and sex of the baby were available. The results of our study suggest ties. The assignment of urbanization levels

that there was no association between consumption of chlorinated drinking water and the risk of was based on the urban-rural classification

low birth weight. Key wors: chlorination, disinfection by-products, drinking water, infants, low of Tzeng and Wu (25). This urbanization

birth weight. Environ Health Peect 108:765-768 (2000). [Online 30 June 2000] index has been applied in our previous stud-

htnp://ehpnl.niebs.nih.gov/docs/200/108p765-768yang/abstra./btmIl ies (26-29). Each municipality in Taiwan (n

= 361) was assigned to an urbanization cate-

gory from 1 to 8. Municipalities with the

The economy and effectiveness of chlorine studies to assess the hazard potential posed by highest urbanization score, such as the

in killing waterborne organisms has made exposure to chlorinated drinking water. Taipei metropolitan area, were classified in

water chlorination a tremendous public category 1, whereas mountainous areas with

health success worldwide. However, chlori- Materials and Methods the lowest score were assigned to category 8.

nation of water can produce trace amounts Selection ofstudy municipalities. Taiwan is Each NCHM was matched with a CHM

of by-products such as trihalomethanes divided into 361 administrative districts, with the same urbanization level. Among the

(THMs), which are carcinogenic organic which are referred to here as municipalities. 15 NCHMs, one was excluded because there

halogenated contaminants of water chlorina- We excluded from the analysis 30 aboriginal was no appropriate municipality for match-

tion (1-3). A number of epidemiologic stud- townships and 9 islets that encompassed dif- ing. If an NCHM had more than one appro-

ies have focused on the possible associations ferent lifestyles and living environments; we priate matching CHM, we used a random

between the consumption of chlorinated also excluded the 12 municipalities of the sampling method to select the CHM.

drinking water and cancer mortality or inci- city of Taipei because of Taipei's distinctly Details of the procedure were described by

dence (415). Most studies have shown pos- more urban character and larger population Yang et al. (15). The sociodemographic

itive associations between the use of chlori- than other municipalities in Taiwan. This characteristics of the CHMs and NCHMs

nated drinking water and colorectal and elimination left 310 municipalities. were generally similar except for a higher

bladder cancer risk. Chlorination has been the major means population and a higher percentage of popu-

Recently, several epidemiologic studies of disinfecting drinking water in Taiwan. lation using the chlorinated water among the

have examined the associations between the Chlorine is currently added to approximately CHMs (96.1 vs. 1.5%) (Table 1).

consumption of chlorinated water and 75.8% of the nation's drinking water. The Data collection. Data on pregnancy out-

adverse pregnancy outcomes (16-24). These current Taiwan water system is rather sim- comes were taken from the routine registra-

studies found associations between chlorina- ple. Residents obtain their drinking water tion of births. Registration of births is

tion and risk of spontaneous abortion, infants either from the public drinking water supply required by law in Taiwan. It is the responsi-

being small for gestational age, having low systems served by the Taiwan Water Supply bility of the parents or the family to register

birth weight, or displaying specific birth Corporation or from nonmunicipal sources. infant births at a local household registration

defects. These studies considered a wide range The major sources of municipal water sup- office within 15 days. Computerized data on

of populations and regions but have been plies are almost all surface waters and are live births were collected from the Household

mainly carried out in the United States. The treated with chlorine. The nonmunicipal

present study was carried out because few epi- sources are mainly privately owned wells Address correspondence to: C-Y. Yang, College of

demiologic studies have been conducted out- (groundwater) and are unchlorinated. Health Science, Kaohsiung Medical University,

side the United States (21,23). There was a In this study, we classified an individual 100 Shih-Chuan 1st RD, Kaohsiung, Taiwan

need for additional studies using new inde- municipality as a chlorinating municipality 80708. Telephone: 886 7 3121101 ext 2141. Fax:

pendent data from other populations, so we (CHM) if > 90% of the municipal popula- 886 7 3110811. E-mail: chunyuh@cc.kmu.edu.tw

tion was served by chlorinated water. In all, This study was partially supported by a grant

undertook the present study in Taiwan to from the National Science Council, Executive

explore further the association between 156 of the 310 municipalities satisfied this Yuan, Taiwan (NSC-89-2320-B-037-023).

adverse birth outcomes and the use of chlori- criterion. A nonchlorinating municipality Received 1 February 2000; accepted 11 April

nated water. This paper is one in a series of (NCHM) was defined as one in which < 5% 2000.

Environmental Health Perspectives * VOLUME 108 1 NUMBER 8 1 August 2000 765

Articles * Yang et al.

Registration System, which is managed by the nal education (< 12 or 2 12 years), and sex of drinking water and the risk of term low

Department of Interior in Taipei. The regis- baby. The analyses were performed using SAS birth weight.

tration form, which asks for information on software (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC). All A few previous studies have looked at the

maternal age, education, parity, gestational statistical tests were two-sided. Values of p < relation between birth weight and preterm

age, date of delivery, infant sex, and birth 0.05 were considered statistically significant. delivery and water chlorination (17,19-22).

weight, is completed by the physician attend- Kramer et al. (17) carried out a population-

ing the delivery. Because most deliveries in Results based case-control study in Iowa. Chloroform

Taiwan take place in either a hospital or dinic Altogether, 18,025 (10,007 CHMs and 8,018 concentrations > 10 ppb in drinking water

(30) and the birth certificates are completed NCHMs) first-parity singleton live births with were associated with a small increase in risk

by physicians attending the delivery, and complete information were included in the of LBW (OR, 1.3; CI, 0.8-2.2) and preterm

because it is mandatory to register all live analysis. Table 2 shows the distribution of delivery (OR, 1.1; CI, 0.7-1.6). Bove et al.

births at local household registration offices, birth outcomes and maternal characteristics by (19) carried out a large retrospective cohort

the birth registration data are considered chlorination practice. The mean birth weights study in New Jersey. Elevated ORs were

complete and accurate. We did not include in the CHMs and NCHMs were 3,181.8 and found for term LBW at THM concentra-

twins or multiple pregnancies in the analysis. 3,170.6 g, respectively. The prevalences of tions > 100 ppb (OR, 1.42; CI, 1.22-1.65)

Gestational ages for live births that were preterm delivery in the CHMs and NCHMs when compared with the reference level of <

outside the range of 20-50 weeks were con- were 4.48 and 3.38%, respectively. The 20 ppb. No association was found between

sidered invalid (31). CHMs had a significantly higher rate of concentrations of THMs and preterm birth

There were 43,807 singleton deliveries in preterm delivery than the CHMs. (OR not shown). Savitz et al. (20) conduct-

the study municipalities between 1 January The CHMs had a lower rate of term ed a population-based case-control study in

1994 and 31 December 1996. Of the LBW than the CHMs (2.49 vs. 2.81%) but North Carolina. THM concentrations

43,782 births with information on parity, the difference was not statistically significant. (82.2-168.8 vs. 40.8-63.3 ppb) were not

first-parity births accounted for 43.76%. Of Table 3 shows the ORs for term LBW and associated with preterm delivery (OR, 0.9;

19,159 first-parity singleton live births, we preterm delivery based on comparisons CI, 0.6-1.5) and LBW (OR, 1.3; CI,

excluded 163 subjects who had invalid or between CHMs and NCHMs using logistic 0.8-2.1). Dodds et al. (21) conducted a

missing information on gestational age. regression. After controlling for possible con- large retrospective cohort study in Canada.

Among the remaining 18,996 subjects, 656 founders (including maternal age, marital The authors did not find excess risk for

were missing birth weight data or maternal status, maternal education, and sex of the LBW (OR, 1.04; CI, 0.92-1.18) or preterm

age data. Of the 18,340 first-parity births infant), the adjusted ORs were 1.34 [95% delivery (OR, 0.97; CI, 0.87-1.09) for

with complete information on these vari- confidence interval (CI), 1. 15-1.56)] for women whose water contained 2 100 ppb

ables, we excluded 315 births because data preterm delivery and 0.90 (CI, 0.75-1.09) THM. Gallagher et al. (22) carried out a ret-

were missing on at least one of three vari- for term LBW, respectively, when compar- rospective cohort study in Colorado. The

ables: maternal educational, maternal marital ing CHMs with NCHMs. Analysis using authors found an excess risk for LBW (OR,

status, or infant birth place. These exclusions term birth weight as a continuous variable 2.1; CI, 1.0-4.8) and term LBW (OR, 5.9;

left 18,025 births for the final analysis. did not indicate an association between birth CI, 2.0-17.0) for those exposed to 2 60 ppb

Statistics. The outcomes of interest in this weight and the use of chlorinated water THM compared with those in the low-expo-

study included term low birth weight (LBW) (data not shown). sure group (< 20 ppb), but no association

(2 37 gestational weeks and < 2,500 g) and between preterm delivery (OR, 1.0; CI,

preterm delivery (< 37 gestational weeks). We Discussion 0.3-2.8) and THM concentrations. Various

used an unconditional logistic regression The results of this study suggest that there is epidemiologic studies point toward an associ-

model to estimate the effects of chlorination no association between the use of chlorinated ation between THMs and term LBW (> 37

practice on the risk of term LBW and

preterm delivery. All odds ratios (ORs) were Table 2. Maternal characteristics, mean birth weight, and prevalences of term LBW and preterm delivery

adjusted for maternal age (< 25 or . 25 years), in first-parity singleton live births in CHMs and NCHMs.

marital status (married or unmarried), mater- Variables CHMs NCHMs p-Value

Table 1. Some characteristics of two groups of Singleton live births (n) 10,007 8,018

Taiwan municipalities, grouped according to Mean birth weight 3,181.8 ± 440.6 3,170.6 ± 439.0 0.089

chlorination practice. Gestational age 0.001

< 37 weeks 448 (4.48%) 271 (3.38%)

Characteristic 14 CHMs 14 NCHMs 2 37 weeks 9,559 (95.52%) 7,747 (96.62%)

Total population 11989) 463,657 397,588 Term LBW (%) 238 (2.49%) 218 (2.81%) 0.148

Mean population 28,399 33,118 Maternal age 0.001

Population density 611.2 600.4 <25 years 4,156 (41 .53%) 3,801 (47.41%)

(per ki2) >25years 5,851 (58.47%) 4,217 (52.59%)

Population served by 96.1 1.5 Marital status 0.888

chlorinating water (%) Married 9,773 (97.66%) 7,833 (97.69%)

White collar (%)a 25.4 24.8 Unmarried 234 (2.34%) 185 (2.31%)

Blue collar (%)b 24.6 22.2 Maternal education 0.001

Agriculture (%(c < 12 years 8,544 (85.38%) 7,167 (89.39%)

50.0 53.0 > 12 years 1,463 (14.62%) 851 (10.61%)

&Professional, technical, administrative, superintendents, Sex of infant 0.289

clerical, sales, and service workers as a percentage of Male 5,209 (52.05%) 4,110 (51.26%)

the total employed (. 15 years of age) population. Female 4,798 (47.95%) 3,908 (48.74%)

hProducers, transportation operators, and laborers as a Birth place 0.999

percentage of the total employed population. cFarmers, Hospital/clinic 10,006 (99.99%)

loggers, grazers, fisherman, hunters, and related work- 8,018 (100.0%)

ers as a percentage of the total employed population. Other 1 (0.01%) 0 (0.00%)

766 VOLUME 1081 NUMBER 8 1 August 2000 * Environmental Health Perspectives

Articles * Water chlorination and birth weiqh

gestational weeks and < 2,500 g) (19,22) but drinking water as a risk factor for LBW has By-Products: Some Other Halogenated Compounds;

not LBW (< 2,500 g) (17,20,21). The not received public attention in Taiwan. Cobalt and Cobalt Compounds. IARC Monogr Eval

Carcinog Risk Hum 52 (1991).

absence of an association with term LBW in Recently, Gallagher et al. (22) reported 4. Cantor KP, Hoover R, Hartge P. Bladder cancer, drinking

our study is not consistent with the associa- an association between LBW, in particular water sources, and tap water consumption: a case-con-

tion found in New Jersey (19) and Colorado term LBW (OR, 5.9; CI, 2.0-17.0) and trol study. J NatI Cancer Inst 79:1269-1279 (1987).

5. Bean JA, Isacson P, Hausler WJ. Drinking water and

(22). Furthermore, our finding appears to be exposure to THMs. The authors have taken cancer incidence in Iowa. I: Trends and incidence by

the first investigation to report a significant an important step in reducing misclassifica- source of drinking water and size of municipality. Am J

association between the use of chlorinated tion of exposure by using the hydraulic Epidemiol 116:912-923 (1982).

drinking water and preterm delivery. model to identify census blocks for which 6. Gottlieb MS, Carr JK, Clarkson JR. Drinking water and

cancer in Louisiana: a retrospective mortality study. Am

Because there is no evidence to date for an individual THM exposure levels were all J Epidemiol 116:652-667 (1982).

association between THMs and preterm well represented by one or more sampling 7. Carpenter LM, Beresford SAA. Cancer mortality and type

delivery (17,19-22), the possibility that this point measurement. Their ability to reduce of water source: findings from a study in the UK. Int J

Epidemiol 15:312-319 (1986).

is a chance finding should be considered. misclassification may account for the 8. Cech I, Holguin AH, Littell AS, Henry JP, O'Connell J.

The major difficulty in studying health stronger effect estimate, despite the relatively Health significance of chlorination byproducts in drink-

effects associated with chlorination lies in low levels of THMs observed in their study. ing water: the Houston experience. Int J Epidemiol

16:198-207 (1987).

assessing exposure (32). In our study, we A number of factors are known or sus- 9. Lawrence CE, Taylor PR, Trock BJ, Reilly AA.

investigated the effects of drinking water pected to affect birth weight, including Trihalomethanes in drinking water and human colorectol

chlorination on adverse birth outcomes using maternal nutrition and prepregnancy weight cancer. J NatI Cancer Inst 72:563-568 (1984).

10. Flaten TP. Chlorination of drinking water and cancer

an extreme points contrast to maximize the and weight gain (35), cigarette smoking incidence in Norway. lnt J Epidemiol 21:6-15 (1992).

inherent power of the design (33,34). We (36), and occupational exposures (37-41). 11. McGeehin MA, Reif JS, Becher JC, Mangione EJ. Case-

used this method in our previous studies Unfortunately, there is no information avail- control study of bladder cancer and water disinfection

methods in Colorado. Am J Epidemiol 138:492-501 (1993).

(15,28). The percentage of the population able on these variables for individual study 12. Morris RD, Audet AM, Angelillo IF, Chalmers TC,

served by chlorinated water in the CHMs subjects and they could not be adjusted for Mosteller F. Chlorination, chlorination by-products, and

and NCHMs was 96.1 and 1.5%, respective- directly in the analysis. However, none of cancer: a meta-analysis. Am J Public Health 82:955-963

ly. Also, the municipalities selected for this these variables are likely to be associated with (1992).

13. Young TB, Wolf DA, Kanarek MS. Case-control study of

study were rural municipalities, and it is chlorination practice, and therefore the esti- colon cancer and drinking water trihalomethanes in

unlikely that the residents would be able to mated effects of chlorination are likely to be Wisconsin. Int J Epidemiol 16:190-197 (1987).

afford bottled water, thus reducing the likeli- free of confounding by these factors. 14. Zierler S, Fiengold L, Danley RA, Craun G. Bladder can-

cer in Massachusetts related to chlorinated and chlo-

hood that water came from a source other We used the extreme point contrast raminated drinking water: a case-control study. Arch

than the home. In line with this assumption, method to assess exposure. Nonetheless, the Environ Health 43: 195-200 (1988).

we expect that women living in the CHMs potential misclassification of exposure 15. Yang CY, Chiu HF, Cheng MF, Tsai SS. Chlorination of

drinking water and cancer mortality in Taiwan. Environ

drink water from the public supply and that remains. Mobility between CHMs and Res 78:1-6 (1998).

women living in NCHMs drink water from NCHMs during pregnancy is likely to be a 16. Shaw GM, Malcoe LH, Milea A, Swan SH. Chlorinated

the private wells (nonchlorinated water). problem in this study. Two U.S. studies water exposures and congenital cardiac anomalies.

Epidemiology 2:459-460 (1991).

THMs are common contaminants of reported that approximately 25% (42) and 17. Kramer MD, Lunch CF, lsacson P, Hanson JW. The asso-

chlorinated drinking water and are the most 37% (43) of women changed residency dur- ciation of waterborne chloroform with intrauterine

consistently measured contaminants in treat- ing pregnancy. No data were available about growth retardation. Epidemiology 3:407-413 (1992).

18. Aschengrau A, Zierler S, Cohen A. Quality of community

ed water. Previous studies attempted to women who moved between the CHMs and drinking water and the occurrence of late adverse preg-

quantify the concentration of THMs and NCHMs during pregnancy. Because misclas- nancy outcomes. Arch Environ Health 48:105-113 (1993).

assign exposure values to women (17,19-22). sification of exposure is likely to be nondiffer- 19. Bove FJ, Fulcomer MC, Klotz JB, Esmart J, Dufficy EM,

In our study we made no attempt to quanti- ential with respect to outcome and effect esti- Savrin JE. Public drinking water contamination and birth

outcomes. Am J Epidemiol 141:850-862 (1995).

fy exposure to THMs in chlorinated water. mates are likely to be biased toward the null 20. Savitz DA, Andrews KW, Pastore LM. Drinking water and

However, we assumed that women living in (34), whatever the level of such misclassifica- pregnancy outcome in central North Carolina: source,

CHMs, on average, experience a higher tion, its effect would likely bias the effect esti- amount, and trihalomethane levels. Environ Health

Perspect 103:592-596 (1995).

exposure to THMs than women living in mates reported here toward the null. 21. Dodds L, King W, Woolcott C, Pole J. Trihalomethanes in

NCHMs (nonchlorinated water) (23). Fear In summary, the present study provides public water supplies and adverse birth outcomes.

of delivering an LBW baby should not have no evidence of an increased risk of term Epidemiology 10:233-237 (1999).

22. Gallagher MD, Nuckols JR, Stallones L, Savitz DA.

deterred women from drinking chlorinated LBW related to the consumption of chlori- Exposure to trihalomethanes and adverse pregnancy

water because the possible role of THMs in nated water. More accurate means of expo- outcomes. Epidemiology 9:484-489 (1998).

sure assessment, including quantifying indi- 23. Magnus P, Jaakkola JJK, Skrondal A, Alexander J,

Becher G, Krogh T, Dybing E. Water chlorination and

Table 3. Adjusted ORs for term LBW and preterm vidual exposure to THMs or other disinfec- birth defects. Epidemiology 10:513-517 (1999).

delivery in first-parity singleton live births by tion by-products from tap water at home, 24. Wailer K, Swan SH, DeLorenze G, Hopkins B.

logistic regression. work, and elsewhere, and other water uses or Trihalomethanes in drinking water and spontaneous

abortion. Epidemiology 9:134-140 (1998).

Variablesa Term LBW (Cl) Preterm (CI) use of more sophisticated modeling tech- 25. Tzeng GH, Wu TY. Characteristics of urbanization levels

CHMsb 0.90 (0.75-1.09) 1.34 (1.15-1.56) niques, may help clarify the effect of water in Taiwan districts. Geograph Res 12:287-323 (1986).

Maternal agec 1.17 (0.96-1.42) 1.02 (0.87-1.21) chlorination on reproduction (24). 26. Yang CY, Chiu JF, Chiu HF, Wang TN, Lee CH, Ko YC.

Relationship between water hardness and coronary

Marital statusd 1.29 (0.75-2.23) 1.83 (1.24-2.70) mortality in Taiwan. J Toxicol Environ Health 49:1-9

Maternal 1.32 (0.95-1.83) 0.98 (0.78-1.23) REFERENCES AND NOTES (1996).

educatione 27. Yang CY, Chiu JF, Lin MC, Cheng MF. Geographic varia-

Sex of infantf 1.34 (1.11-1.62) 0.81 (0.70-0.95) 1. Reuber MD. Carcinogenicity of chloroform. Environ tions in mortality from motor vehicle crashes in Taiwan.

Health Perspect 31:171-182 (1979). J Trauma 43:74-77 (1997).

"Logistic models include all five variables in the model. 2. Dunnick JK, Melnick RL. Assessment of the carcinogenic 28. Yang CY, Chiu HF, Chiu JF, Kao WY, Tsai SS, Lan SJ.

bThe reference group was NCHMs. cThe reference potential of chlorinated water: experimental studies of Cancer mortality and residence near petrochemical

groups was > 25 years of age. "The reference group was chlorine, chloramine, and trihalomethanes. J NatI industries in Taiwan. J Toxicol Environ Health 50:265-273

married women. eThe reference group was 2 12 years of Cancer Inst 85:817-822 (1993). (1997).

education. 'the reference group was male. 3. IARC. Chlorinated Drinking-Water; Chlorination 29. Yang CY, Cheng MF, Tsai SS, Hung CF. Fluoride in drinking

Environmental Health Perspectives * VOLUME 1081 NUMBER 81 August 2000 767

Articles * Yang et al.

water and cancer mortality in Taiwan. Environ Res 35. Paige D, Davis LR. Fetal growth, maternal nutrition, and 40. Xu X, Ding M, Li B, Christiani DC. Association of rotating

82:189-193 (2000). dietary supplementation. Clin Nutr 5:191-199(1986). shiftwork with preterm births and low birthweight among

30. Wu SC, Young CL. Study of the birth reporting system. J 36. Sexton M, Hebel JR. A clinical trial of change in mater- never smoking women textile workers in China. Occup

NatI Public Health Assoc 6:15-27 (1986). nal smoking and its effect on birth weight. JAMA Environ Med 51:470-474 (1994).

31. Alexander GR, Tompkins ME, Cornely DA. Gestational 251:911-915 (1984). 41. Nurminen T, Kurpaa K. Occupational noise exposure and

age reporting and preterm delivery. Public Health Rep 37. Taylor PR, Stelma JM, Lawrence CE. The relation of poly- course of pregnancy. Scand J Work Environ Health

105:267-275 (1990). chlorinated biphenyls to birth weight and gestational age 15:117-124 (1989).

32. Swan SH, Wailer K. Disinfection by-products and in the offspring of occupationally exposed mothers. Am J 42. Shaw GM, Malcoe LH. Residential mobility during preg-

adverse pregnancy outcomes: what is the agent and Epidemiol 129:395-406(1989). nancy for mothers of infants with or without congenital

how it should be measured [Editorial]. Epidemiology 38. Teitelman AM, Welch LS, Hellenbrand KG, Bracken MB. cardiac anomalies: a reprint. Arch Environ Health

9:479-481 (1998). Effect of maternal work activity on preterm birth and low 47:236-238 (1992).

33. Miettinen OS. Theoretical Epidemiology. New York:John birthweight. Am J Epidemiol 131:104-113 (1990). 43. Khoury M, Stewart W, Weinstein A, Panny S, Lindsay P,

Wiley & Sons, 1985. 39. Axelsson G, Rylander R, Molin I. Outcome of pregnancy Eisenberg M. Residential mobility during pregnancy:

34. Rothman KJ, Greenland S. Modern Epidemiology. 2nd ed. in relation to irregular and inconvenient work schedules. implications for environmental teratogenesis. J Clin

Philadelphia:Lippincott-Raven Publishers, 1998. Br J Ind Med 46:393-398 (1989). Epidemiol 41:15-20 (1988).

Not if you subscribe to Environmental

Health Perspectives. With each monthly issue,

Environmental Health Perspectives gives you

comprehensive, cutting-edge environmental health

and medicine research and news.

When it comes to outfitting your lab with the best

research tools, Environmental Health Perspectives is

the state of the art._

Call 1-800-315-3010 today to

subscribe and visit us online.

-r >< f What you know is more

important than what you have.

http://ehis.niehs.nih. gov/

768 VOLUME 1081 NUMBER 81 August 2000 * Environmental Health Perspectives

You might also like

- Biology Investigatory ProjectDocument41 pagesBiology Investigatory Projectsubitha77% (139)

- Atrazine Contamination of Drinking Water and Adverse Birth Outcomes in Community Water Systems With Elevated Atrazine in Ohio, 2006-2008Document14 pagesAtrazine Contamination of Drinking Water and Adverse Birth Outcomes in Community Water Systems With Elevated Atrazine in Ohio, 2006-2008Instituto Pablo JamilkNo ratings yet

- Literature Review of Water Treatment ProcessDocument6 pagesLiterature Review of Water Treatment Processc5r0qjcf100% (1)

- Determinants of Implementation of County Water and Sanitation Programme in Maseno Division of Kisumu West SubCounty, Kisumu County, KenyaDocument15 pagesDeterminants of Implementation of County Water and Sanitation Programme in Maseno Division of Kisumu West SubCounty, Kisumu County, KenyajournalNo ratings yet

- Literature Review On Drinking Water TreatmentDocument5 pagesLiterature Review On Drinking Water Treatmentafmabbpoksbfdp100% (1)

- Jurnal Ikmas 1Document10 pagesJurnal Ikmas 1ApriliasBMNo ratings yet

- Pnaaq 815Document88 pagesPnaaq 815benjoscoliNo ratings yet

- Water TanzaniaDocument6 pagesWater TanzaniaElite Cleaning ProductsNo ratings yet

- Research Paper On Drinking Water Quality in PakistanDocument6 pagesResearch Paper On Drinking Water Quality in Pakistanafeawckew100% (1)

- Water and Sanitation Thesis TopicsDocument7 pagesWater and Sanitation Thesis Topicsshannongutierrezcorpuschristi100% (2)

- Dissertation Water QualityDocument4 pagesDissertation Water QualityBestWriteMyPaperWebsiteUK100% (1)

- Solomon2020 Article EffectOfHouseholdWaterTreatmenDocument13 pagesSolomon2020 Article EffectOfHouseholdWaterTreatmenSiti lestarinurhamidahNo ratings yet

- An Assessment of Drinking-Water Quality Post-Haiyan: Field Investigation ReportDocument5 pagesAn Assessment of Drinking-Water Quality Post-Haiyan: Field Investigation ReportAhmed Mohamed Shawky NegmNo ratings yet

- Impact of Poorly Maintained Waste Water and Sewage Treatment Plants Lessons From South AfricaDocument16 pagesImpact of Poorly Maintained Waste Water and Sewage Treatment Plants Lessons From South AfricaMark EliasNo ratings yet

- Parasitological and Nutritional AssessmeDocument9 pagesParasitological and Nutritional AssessmezeitastirNo ratings yet

- Wright 2006Document9 pagesWright 2006Nermeen ElmelegaeNo ratings yet

- Final Thesis2023Document17 pagesFinal Thesis2023rueNo ratings yet

- My Published ProjectDocument10 pagesMy Published ProjectIsrael ApehNo ratings yet

- The Treatment of Rainwater For Potable Use: General Manager, Sales & Marketing, Davey Water ProductsDocument7 pagesThe Treatment of Rainwater For Potable Use: General Manager, Sales & Marketing, Davey Water Productsmohammad yaseenNo ratings yet

- 2010 Maternal and Fetal Exposure To Four Carcinogenic Environmental Metals - Huai Guan Et Al.Document8 pages2010 Maternal and Fetal Exposure To Four Carcinogenic Environmental Metals - Huai Guan Et Al.Fabricio Martínez100% (1)

- 1 s2.0 S2666535222000994 MainDocument9 pages1 s2.0 S2666535222000994 MainDea AmandaNo ratings yet

- Holm Et Al. 2016 Achieving The Sustainable Development Goals - A Case Study of The Complexity of Water Quality Health Risk 1Document9 pagesHolm Et Al. 2016 Achieving The Sustainable Development Goals - A Case Study of The Complexity of Water Quality Health Risk 1EddiemtongaNo ratings yet

- Environmental Predictors of Diarrhoeal Infection For Rural andDocument12 pagesEnvironmental Predictors of Diarrhoeal Infection For Rural andrahamansyahilhamNo ratings yet

- Rural Drinking Water at Supply and Household Levels: Quality and ManagementDocument10 pagesRural Drinking Water at Supply and Household Levels: Quality and ManagementEdukondalu BNo ratings yet

- Thesis Rainwater HarvestingDocument6 pagesThesis Rainwater HarvestingScott Donald100% (2)

- Review of Related LiteratureDocument3 pagesReview of Related LiteratureYNA ANGELA ACERO GAMANANo ratings yet

- Jurnal DMT2Document10 pagesJurnal DMT2Ida Ayu DhitayoniNo ratings yet

- Literature Review On Water Supply and SanitationDocument12 pagesLiterature Review On Water Supply and Sanitationgw163ckj100% (1)

- Risk Perception2Document11 pagesRisk Perception2GSPNo ratings yet

- Drinking WaterDocument20 pagesDrinking Watergreskpremium8No ratings yet

- Sage Publications, Inc., Association of Schools of Public Health Public Health Reports (1896-1970)Document26 pagesSage Publications, Inc., Association of Schools of Public Health Public Health Reports (1896-1970)Asniza AbasNo ratings yet

- Occurrence and Health Risk Assessment of Pharmaceutical and Personal Care Products (PPCPS) in Tap Water of ShanghaiDocument8 pagesOccurrence and Health Risk Assessment of Pharmaceutical and Personal Care Products (PPCPS) in Tap Water of ShanghaiTiago TorresNo ratings yet

- Bullwho00048 0043Document13 pagesBullwho00048 0043christ.wong012001No ratings yet

- Water Management Literature ReviewDocument4 pagesWater Management Literature Reviewafmzmxkayjyoso100% (1)

- Impact of Acces To Water and SanitationDocument14 pagesImpact of Acces To Water and Sanitationnur aisyahNo ratings yet

- Artículo LupitaDocument12 pagesArtículo LupitaAna MoralesNo ratings yet

- ClorinationDocument10 pagesClorinationSandeep_AjmireNo ratings yet

- Hepatite A 2Document8 pagesHepatite A 2escabreraNo ratings yet

- Literature Review WaterDocument4 pagesLiterature Review Waterc5pnw26s100% (1)

- capstone-LRRDocument15 pagescapstone-LRRronskierelenteNo ratings yet

- Journal Pone 0012613Document10 pagesJournal Pone 0012613Sena AniakuNo ratings yet

- 6) Raphael C. Mkwate, 2016Document27 pages6) Raphael C. Mkwate, 2016yesuf4assefaNo ratings yet

- A National Wastewater Monitoring Program For A Better Understanding ofDocument12 pagesA National Wastewater Monitoring Program For A Better Understanding ofValentina Rico BermudezNo ratings yet

- AJTMHJuly2014190 FullDocument9 pagesAJTMHJuly2014190 FullRizki WahyuniNo ratings yet

- 10.1007@s12403 019 00299 8Document7 pages10.1007@s12403 019 00299 8mohamed hiflyNo ratings yet

- Ebsco Fulltext 2024 03 20Document18 pagesEbsco Fulltext 2024 03 20api-733654444No ratings yet

- Potability of Water Sources in Northern CebuDocument33 pagesPotability of Water Sources in Northern CebuDelfa CastillaNo ratings yet

- Three Key Factors in Uencing The Bacterial Contamination of Dental Unit Waterlines: A 6-Year Survey From 2012 To 2017Document8 pagesThree Key Factors in Uencing The Bacterial Contamination of Dental Unit Waterlines: A 6-Year Survey From 2012 To 2017khamilatusyNo ratings yet

- Jurnal Sanitasi 2Document13 pagesJurnal Sanitasi 2andhikaadyatmaaNo ratings yet

- 1 s2.0 S0959378020307317 MainextDocument15 pages1 s2.0 S0959378020307317 MainextSiddhant jainNo ratings yet

- 10 1 1 559 175 PDFDocument15 pages10 1 1 559 175 PDFEldhaNo ratings yet

- 12 Economic Toll of PollutiDocument9 pages12 Economic Toll of PollutiEdgarvitNo ratings yet

- Assignment 2 FinalDocument8 pagesAssignment 2 FinalJameson KaundaNo ratings yet

- Term PaperDocument3 pagesTerm Paperdavinceaaron3No ratings yet

- Microbial and Endotoxin Contamination in Water and Dialysate in The Central United StatesDocument4 pagesMicrobial and Endotoxin Contamination in Water and Dialysate in The Central United StatesfarhanomeNo ratings yet

- Water Contamination and The Rate of Infections For Water BirthsDocument16 pagesWater Contamination and The Rate of Infections For Water Birthsmagallanes36No ratings yet

- 3 Articles in ChemistryDocument15 pages3 Articles in ChemistryAngeline OsicNo ratings yet

- Piped Water Access, Child Health and The Complementary Role of Education-Panel Data Evidence From South AfricaDocument20 pagesPiped Water Access, Child Health and The Complementary Role of Education-Panel Data Evidence From South AfricaKhánh ThươngNo ratings yet

- Water Literature ReviewDocument6 pagesWater Literature Reviewdafobrrif100% (1)

- De Soto 1989 North 1990: The Quarterly Journal of Economics (2011) 126, 145-205. Doi:10.1093/qje/qjq010Document61 pagesDe Soto 1989 North 1990: The Quarterly Journal of Economics (2011) 126, 145-205. Doi:10.1093/qje/qjq010pgpsm09030No ratings yet

- The Paradox of Water: The Science and Policy of Safe Drinking WaterFrom EverandThe Paradox of Water: The Science and Policy of Safe Drinking WaterNo ratings yet

- HomatropinDocument11 pagesHomatropinDesma ParayuNo ratings yet

- Resume SampleDocument3 pagesResume Samplebibs_caigas37440% (1)

- Placenta Previa Journal KristalDocument23 pagesPlacenta Previa Journal KristalGabbyNo ratings yet

- Perioperative Anticoagulation Bridging Guideline PostedDocument6 pagesPerioperative Anticoagulation Bridging Guideline PostedNuc Alexandru100% (1)

- Treatment of Constipation in Older Adult AAFPDocument8 pagesTreatment of Constipation in Older Adult AAFPTom KirklandNo ratings yet

- Accoucheurs ManualDocument37 pagesAccoucheurs ManualDrRenu Jain100% (1)

- Ab-Ark Benefit Packages (Private)Document66 pagesAb-Ark Benefit Packages (Private)raamki_99No ratings yet

- 01 Application (Permit To Construct)Document1 page01 Application (Permit To Construct)jherica baltazar100% (1)

- Calculo HGTDocument4 pagesCalculo HGTNestor Mendoza ElíasNo ratings yet

- Newyork-Presbyterian: Morgan Stanley Children'S HospitalDocument41 pagesNewyork-Presbyterian: Morgan Stanley Children'S HospitalTmanoj PraveenNo ratings yet

- Gestational Diabetes - On Broadening The DiagnosisDocument2 pagesGestational Diabetes - On Broadening The DiagnosisWillians ReyesNo ratings yet

- 2010 Era Journal Rank List PDFDocument904 pages2010 Era Journal Rank List PDFHassen M OuakkadNo ratings yet

- Instrument Separation Analysis of Multi-Used Protaper Universal Rotary System During Root Canal TherapyDocument6 pagesInstrument Separation Analysis of Multi-Used Protaper Universal Rotary System During Root Canal TherapyShoaib YounusNo ratings yet

- Day 2 Maternal Fetal Triage Index ToolDocument21 pagesDay 2 Maternal Fetal Triage Index ToolponekNo ratings yet

- English in Nursing - Rheynanda (2011316059)Document3 pagesEnglish in Nursing - Rheynanda (2011316059)Rhey RYNNo ratings yet

- A ObstetricsDocument87 pagesA ObstetricsGeraldine PatayanNo ratings yet

- Gynecological ExaminationDocument20 pagesGynecological Examinationwahyu kijang ramadhanNo ratings yet

- Marijuana Use and Breastfeeding PDFDocument7 pagesMarijuana Use and Breastfeeding PDFmdbackesNo ratings yet

- Hospital ManagementDocument26 pagesHospital Managementsanjib beraNo ratings yet

- EHAQ 4th Cycle Audit Tool Final Feb.10-2022Document51 pagesEHAQ 4th Cycle Audit Tool Final Feb.10-2022Michael Gebreamlak100% (1)

- A Report On Summer Posting AT Jag Pravesh Chandra HospitalDocument25 pagesA Report On Summer Posting AT Jag Pravesh Chandra HospitalDeepti KukretiNo ratings yet

- Evaluation of Guaifenesin-Ketamine-Xylazine and Diazepam-Ketamine-Xylazine Triple Drip For Gelding in EquinesDocument5 pagesEvaluation of Guaifenesin-Ketamine-Xylazine and Diazepam-Ketamine-Xylazine Triple Drip For Gelding in Equinessanjeev pitlawarNo ratings yet

- 3shape Implant Studio Drilling Protocol: Contact InformationDocument2 pages3shape Implant Studio Drilling Protocol: Contact Informationnha khoa NHƯ NGỌCNo ratings yet

- Advancing Partners & Communities: Health Facility Assessment ToolDocument44 pagesAdvancing Partners & Communities: Health Facility Assessment ToolSuhailAlakhliNo ratings yet

- The Background of The Plastic Surgeon by Dr. Jay Calvert.Document2 pagesThe Background of The Plastic Surgeon by Dr. Jay Calvert.Bentzen94IpsenNo ratings yet

- Mindray: Expanding The Envelope of Performance and FlexibilityDocument8 pagesMindray: Expanding The Envelope of Performance and FlexibilityLeeNo ratings yet

- ReferenceDocument4 pagesReferenceStephani LeticiaNo ratings yet

- Ramos V CADocument3 pagesRamos V CAboomonyou100% (1)

- Mitral Valve Repair Using Robotic Technology: Safe, Effective, and DurableDocument5 pagesMitral Valve Repair Using Robotic Technology: Safe, Effective, and DurablewkwkwNo ratings yet