Professional Documents

Culture Documents

B.ing Kinerja

B.ing Kinerja

Uploaded by

ulfaOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

B.ing Kinerja

B.ing Kinerja

Uploaded by

ulfaCopyright:

Available Formats

The Effects of Job Embeddedness on Organizational Citizenship, Job Performance, Volitional

Absences, and Voluntary Turnover

Author(s): Thomas W. Lee, Terence R. Mitchell, Chris J. Sablynski, James P. Burton and

Brooks C. Holtom

Source: The Academy of Management Journal, Vol. 47, No. 5 (Oct., 2004), pp. 711-722

Published by: Academy of Management

Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/20159613 .

Accessed: 15/08/2013 09:20

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at .

http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp

.

JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of

content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms

of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org.

Academy of Management is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to The Academy

of Management Journal.

http://www.jstor.org

This content downloaded from 131.91.169.193 on Thu, 15 Aug 2013 09:20:18 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Academy ofManagement journal

2004, Vol. 47, No. 5, 711-722.

THE EFFECTS OF JOB EMBEDDEDNESS ON ORGANIZATIONAL

CITIZENSHIP, JOB PERFORMANCE, VOLITIONAL ABSENCES, AND

VOLUNTARY TURNOVER

THOMAS W. LEE

TERENCE R. MITCHELL

University of Washington, Seattle

CHRIS J. SABLYNSKI

California State University, Sacramento

JAMES P. BURTON

University of Washington, Bothell

BROOKS C. HOLTOM

Georgetown University

This study extends theory and research on job embeddedness, which was disaggre

gated into its two major subdimensions, on-the-job and off-the-job embeddedness. As

revealed that off-the-job embeddedness was signif

hypothesized, regression analyses

icantly predictive of subsequent "voluntary turnover" and volitional absences,

whereas on-the-job embeddedness was not. Also as hypothesized, on-the-job embed

dedness was significantly predictive of organizational citizenship and job perfor

mance, whereas off-the-job embeddedness was not. In addition, embeddedness mod

erated the effects of absences, citizenship, and performance on turnover. Implications

are discussed.

For over 45 years, management scholars have the decisions to participate and to perform than has

theorized about and investigated the been traditionally thought to exist. Recent theory

empirically

causes of employees' jobs, or and research have suggested new and different

voluntarily leaving

turnover" (Maertz & Cam ways to think about turnover, going beyond a strict

"voluntary employee

pion, 1998). In their classic book, Organizations, focus on an employee decision to participate. Add

March and Simon (1958) provided much of the ing considerable richness have been the work of

theoretical for the psychological re Hulin and associates, on a general withdrawal con

underpinning

search on voluntary turnover. They conceptualized struct 1991); of Lee and associates, on

(e.g., Hulin,

employee turnover as a reflection of an employee's multiple paths for leaving, described in their un

decision to participate in the activities of his or her folding model (e.g., Lee & Mitchell, 1994); and of

organization. They also outlined how such a deci Mitchell and associates, on job embeddedness, a

sion to participate differs in substantial ways from construct including both on- and off-the job causes

a decision to perform. As a result of this conceptu of turnover (e.g., Mitchell, Holtom, Lee, Sablynski,

alization, most research on the participation deci & Erez, 2001). Equally these new ideas

important,

sion has treated the performance decision as a have helped scholars better understand the concep

deliberation. A more thorough tual and empirical links between with

largely independent employee

reading of March and Simon and of other, recent drawal and workperformance.

research a closer link between First, we

suggests, however, This study had two specific purposes.

on job embed

sought to extend theory and research

dedness by demonstrating how its major compo

nents (that is, on- and off-the-job embeddedness)

We thank John Cotton (Marquette University) and Greg

differentially predicted the decision to perform

(or

Bigley (University of Washington) for their suggestions

and and

on a draft and Judith Aptaker (University ofWashington) ganizational citizenship job performance)

for their the decision to participate

(volitional absences and

and Greg Anderson (University of Washington)

with the data. voluntary turnover). Second, we sought to show

help

Susan Jackson served as action editor for this manu how these embeddedness components might be

script. processes through which the decisions to perform

711

This content downloaded from 131.91.169.193 on Thu, 15 Aug 2013 09:20:18 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

712 October

Academy of Management Journal

and to participate could be conceptually and em tualization of withdrawal than is found in most

pirically linked. contemporary turnover research. They advocated

for and empirically demonstrated the validity of a

general withdrawal construct (Hanish & Hulin,

CONCEPTUAL BACKGROUND

1991). More specifically, withdrawal was theorized

March and Simon (1958: Chapters 3 & 4) clearly to include multiple work behaviors occurring se

differentiated between the decisions to perform quentially over time, such as poor de

citizenship,

and to participate. They explained the performance creased job performance, increased absences, and

decision in terms of motivational concepts such as finally leaving. The withdrawing person demon

goals, expectancies, and social control (for in strates "a progression of withdrawal from the very

stance, norms, group pressure, and rewards). In mild and easy to the difficult and decisive" (Hulin,

contrast, they explained the participation decision 1998: 11). These ideas suggest that the decisions

in terms of perceived desirability of movement and to perform and participate are related, with the

perceived ease of movement. Over the years, desir decision to perform the decision to

preceding

ability of movement has come to mean work atti participate.

tudes like job satisfaction or organizational com The research Mc

by Lee, Mitchell, Holtom,

mitment, whereas ease of movement has come to Daniel, and Hill (1999) expresses related ideas in

mean perceived job alternatives or actual unem terms of the unfolding model of turnover, accord

ployment rates. More specifically, most turnover ing to which leaving occurs over time and can

theory has the premise that people leave if they are follow various paths. Some turnover happens

unhappy with their jobs and job alternatives are quickly (for instance, a for

preexisting "script"

available. This focus on dissatisfaction, low com leaving drives an employee to quit in response to

mitment, and prevalent job alternatives dominates some event), and some happens more (for

slowly

the study of voluntary turnover. Although gener instance, accumulated job dissatisfaction leads to a

ally valid, the traditional models have had modest search for alternatives). In addition, many people

success in predicting turnover (e.g., Griffeth, Horn, leave because of discernable events,

precipitating

& Gaertner, 2000), with their variables seldom ex and many of these events occur off the job (a spouse

plaining more than 10 percent of variance. relocates, an unsolicited job offer is received).

New ways to think about turnover may be Thus, specific off-the-job events can precipitate

needed. In this research, we attempted to integrate turnover.

March and Simon's ideas about the links between More recently, Mitchell, Holtom, Lee, Sablynski,

the decisions to perform and to participate with and Erez (2001) focused on why stay rather

people

more recent research on employee withdrawal than on how leave. In

by they particular, they drew

Hulin, Lee, and Mitchell. First, March and Simon attention to the reasons people stay through their

(1958) suggested that withdrawal occurs over time job embeddedness construct. the idea of

Reflecting

and includes more types of participation decisions people's being "situated or connected in a social

than just turnover. They stated, "The motivation to web," embeddedness has

several key aspects: (1)

withdraw factor is a general one that holds for both the extent to which people have links to other

absences and voluntary turnover" (March & Simon, people or activities, (2) the extent to which their

1958: 93). In other words, both absences and turn jobs and communities fit other aspects in their "life

over reflect decisions about participation. Second, spaces," and (3) the ease with which links could be

they suggested that many off-the-job factors are im broken?what they would give up if left their

they

portant determinants of why people stay or leave. present settings. Mitchell and his coauthors called

For instance, as March and Simon wrote, "Families these three dimensions links, fit, and re

sacrifice,

often have attitudes about what jobs are appropri spectively, and they are important both on and off

ate for their members" (1958: 72) and "The integra the job. Thus, one can think of a three by two

tion of individuals into the community has fre matrix that shows six dimensions: links, fit, and

quently been urged by organizations because it sacrifice in an organization and in a community.

offers advantages for public relations and reduces Mitchell and his colleagues (2001) provided ini

voluntary mobility" (1958: 72). Thus, March and tial empirical support for job embeddedness. Draw

Simon theorized that severing participation entails ing on data from a sample of retail employees and

more than dissatisfaction-induced It in another of hospital

leaving. sample employees, they first

volves multiple actions, community, and family. reported that job embeddedness was reliably mea

Furthermore, both on- and off-the-job factors are sured as an aggregated score across their six dimen

important antecedents of employee turnover. sions. Second, aggregated job embeddedness corre

Hulin and associates proposed a broader concep lated with intention to leave and predicted

This content downloaded from 131.91.169.193 on Thu, 15 Aug 2013 09:20:18 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

2004 Lee, Mitchell, Burton, and Holtom 713

Sablynski,

subsequent voluntary turnover. Third, job embed That is, leaving a job may have significant effects

dedness significantly predicted turnover after the on an individual's off-the-job life, especially if he

effects of gender, satisfaction, commitment, job or she has to relocate to find new employment.

search, and perceived alternatives had been con More specifically, people who are embedded in

trolled. Thus, job embeddedness was related to one their communities should want to keep their jobs.

of the major decisions about participation, namely, Mitchell and colleagues (2001) reported, for exam

turnover.

ple, that having (1) a working spouse, (2) children

These findings, and the work of March, Simon, in a particular school, or (3) involvement in com

and Hulin, suggest three main ideas: First, job em munity activities was associated with less turnover.

beddedness can be disaggregated into two major To the extent that absences endanger employment

components: embeddedness (that is, or status, they should be lower for people who are

on-the-job

fit, links, and sacrifice) and off-the-job embedded on- and off-the-job.

ganizational

embeddedness (that is, community fit, links, and Extending our reasoning further, off-the-job em

sacrifice). Second, these two components may have beddedness may be more important to the predic

different effects on indicators of performance and tion of turnover and absences than on-the-job em

participation (absences and turnover). Third, em beddedness when satisfaction and commitment

occurs over time, with a deci are on-the-job are controlled.

ployee withdrawal (which constructs)

sion about performing preceding a decision about First, at least some of an

individual's decisions

participating. about absence and

leaving an organization should

be associated with thoughts and considerations

about what would happen if he or she did not have

Hypotheses a job (a hypothetical future or distal state). These

As conceptualized, job embeddedness reflects thoughts (such as job loss owing to being absent too

employees' decisions to participate broadly and di often [Hulin, 1991]) involve potential disruptions

rectly, and itmoves scholarly attention beyond dis to the individual's community involvement, espe

satisfaction-induced leaving. More aptly, job em cially if relocating were required (March & Simon,

beddedness is a retention (or "antiwithdrawal") 1958). In other words, these thoughts do not nec

construct. Hulin

(1998) never directly measured a essarily involve immediate on-the-job consider

general withdrawal construct, instead inferring it ations but do involve off-the-job considerations.

from the occurrence of multiple work behaviors. If Second, Mitchell and his colleagues (2001) re

embeddedness is indeed a broad-based reten ported higher bivariate correlations between on

job

tion (antiwithdrawal) construct and if it captures a the-job embeddedness and

satisfaction, commit

sizable portion of the "decision to participate," ment, and turnover than between off-the-job

both on- and off-the-job embeddedness should pre embeddedness and satisfaction, commitment, and

dict not only employee turnover, but also other turnover. Thus, the effects of on-the-job embedded

withdrawal behaviors, such as decreasing organiza ness on participation may occur in conjunction

tional citizenship behavior, decreasing perfor with work attitudes like satisfaction and commit

mance, and increasing absence. Further, the ex ment, whereas the effects of off-the-job embedded

plained variance in these withdrawal behaviors ness on participation may be less shaped by atti

should exceed that explained by job satisfaction tudes. In other words, on-the-job embeddedness

and organizational commitment. shares more variance with job attitudes than off

In meta-analyses, Griffith and colleagues (2000) the-job embeddedness does; as a result, the higher

showed that job satisfaction and organizational correlation between on-the-job embeddedness and

commitment significantly related to absences and turnover may be mostly due to effects shared with

that absences significantly predicted turnover. Be job attitudes. The lower (but significant) correlation

cause on-the-job embeddedness correlates to satis between off-the-job embeddedness and turnover

faction, commitment, and turnover (Mitchell et al., may reflect different and new information.

2001), it should predict subsequent absences as When considered together, the two arguments

well. However, the effect of on-the-job embedded made above?(1) people think about the future state

ness on absences and turnover may be reduced to of not having a job and its possible effects on com

zero when researchers control for satisfaction and munity involvement and (2) the correlations be

commitment. Further, the ideas of Hulin,

March, tween on- and off-the-job embeddedness and work

Simon, Lee, and Mitchell about nonwork

factors attitudes differ?lead to the following expectation:

suggest that off-the-job embeddedness predicts ab with the attitudes of satisfaction and commitment

sences and turnover, and it may do so even when controlled, the effects of on-the-job embeddedness

satisfaction and commitment are controlled for. on the decision to participate at work should not be

This content downloaded from 131.91.169.193 on Thu, 15 Aug 2013 09:20:18 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

714 Academy Journal October

of Management

significant, but the effects of off-the-job embedded social exchange (Van Dyne & Ang, 1998), norms of

ness on turnover and absences should remain. That reciprocity (Gouldner, 1960), perceived organiza

is, off-the-job embeddedness adds new information tional support (Rhoades & Eisenberger, 2002), and

about why people are absent or leave. work status congruence (Holtom, Lee, & Tidd,

2002) suggest that people come to feel obligated

Hypothesis 1. After job satisfaction and orga

and want to help persons and organizations that

nizational commitment are statistically con

have helped them.

trolled for, off-the-job embeddedness nega Much of the above

reasoning explicitly involves

tively relates to voluntary turnover and

the effect of on-the-job embeddedness on (in-role)

volitional absences, whereas on-the-job em

job performance and (extra-role) organizational cit

beddedness does not predict these withdrawal

izenship. Most importantly, the attributes of a job

behaviors.

and an organization should be significantly more

On the basis of the reviewed theories (Hulin, salient for the immediate motivation (and decision)

1991; Lee & Mitchell, 1994; March & Simon, 1958; to perform than are off-the-job factors. On-the job

Mitchell et al., 2001), we also believe that the de embeddedness should be more proximal to a deci

cision to perform should be related to job embed sion to perform (as manifested by citizenship be

dedness via motivational effects. Because high on haviors and job performance) than the more distal

the-job embeddedness reflects (1) many links, (2) a decision to participate (as reflected by turnover and

good fit, and/or(3) consequential things that an absences, which involve future states and off-the

employee up by quitting,

gives the motivation to job considerations). That is, employees have to per

perform should

be high. That is, employees with form immediately (or right now), whereas they may

high on-the-job embeddedness will (1) be involved be absent next week or quit next month. Although

in and tied to projects and people, (2) feel they fit off-the-job embeddedness should have an effect on

well in their jobs and can apply their skills, and (3) performance, it should be relatively minor. In par

sacrifice valued things if they quit. Correspond ticular, the saliency of the immediate job and orga

ingly, the motivation to perform should be high. nization supersedes, renders less meaningful, or

(Low motivation should occur when on-the-job em makes less potent the more distal effects of off-the

beddedness is low.) job embeddedness on the decision to perform.

The relationship between job embeddedness and

Hypothesis 2. After job satisfaction and orga

the decision to perform can be further specified. In

nizational commitment are controlled for, on

the last decade, the domain of performance has

the-job embeddedness positively relates to or

been divided into in-role and extra-role (e.g., Wil

ganizational citizenship and job performance,

liams & Anderson, 1991). In-role performance is

whereas off-the-job embeddedness is unrelated

similar to

job-description-based specifications of

to these performance indicators.

performance, whereas organizational citizenship

behavior is part of a larger family of extra-role be In their original meta-analysis, Horn and Griffeth

haviors (Van Dyne, Cummings, & McLean Parks, (1995) reported an estimated rho of .33 between

1995). Most often, citizenship is seen as an employ volitional absences and voluntary turnover, and an

ee's actions that help others better perform their estimated rho of -.19 between job performance and

jobs (for instance, training co-workers) and thereby employee turnover. In their update, Griffeth et al.

enhance organizational effectiveness. (2000) reported a rho of .20 between absences and

Conceptually, the more an individual is job em turnover and a rho as -.15 between

performance

bedded (or socially enmeshed) in an organization, and turnover. From these summary findings, an

the more likely he or

she should be to display enduring conclusion is that increased absence sig

citizenship behaviors. In particular, people may be nals more turnover and that good performance sig

(or linked to one another), and nals less turnover. We propose that on-the-job em

interdependent

acts may be consistent with their feelings of beddedness moderates of absences

the effect on

helpful

comfort (or fit) stemmingfrom being part of that turnover and the effect of job performance on turn

social network. The morean employee fits a job, over. As suggested above, higher on-the-job embed

colleagues, and organization, the more natural it dedness reflects more links, better fit, and more

should be to perform citizenship behaviors. In ad consequential losses if an employee quits. As such,

dition, helping others may be perceived as promot people with higher on-the-job embeddedness

ing others' future helpful acts. Foregoing the oppor should to some extent believe and be concerned

tunity to help other interdependent people may that more volitional absences and lower job perfor

well be seen as a sacrificed opportunity to gain an mance may endanger the status of being employed

owed favor. Indeed, the theory and research on and/or attached to their jobs. Conversely, people

This content downloaded from 131.91.169.193 on Thu, 15 Aug 2013 09:20:18 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

2004 Lee, Mitchell Burton, and Holtom 715

Sablynski,

with lower on-the-job embeddedness should hold site. In December 1998, an employee survey was

this belief and concern to a lesser extent. conducted. Individuals' names, employee num

bers, personal characteristics, job satisfaction, orga

Hypothesis 3a. On-the-job embeddedness

nizational commitment, and on- and off-the-job

moderates the positive effect of volitional ab were

embeddedness assessed with voluntary self

sences on voluntary turnover in such a way

reported measures. In January 1999, unit supervi

that these effects are stronger for higher than sors rated their subordinates' organizational citi

for lower on-the-job embeddedness.

zenship behavior and job performance. Absences

3b. embeddedness and turnover for calendar year 1999 were collected

Hypothesis On-the-job

moderates the negative from company records.

effect of job perfor

mance on voluntary turnover in such a way Surveys were distributed to 1,650 employees in

that these effects are stronger for higher than five separate organizational units. Of the 1,650 sur

for lower on-the-job embeddedness. veys, 839 surveys (51%) were returned. Ten sur

veys were not included in the analyses because

Less theoretical and empirical evidence exists on a

they: (1) lacked signed consent form, (2) were

the relationships among organizational citizenship had no or (4)

illegible, (3) identifying information,

and participation (absences and turnover) than ex were identifiable but blank. our

Thus, sample's

ists for in-role performance. For example, a review data come from 829 employees a 50

and represent

by Podsakoff, MacKenzie, Pain, and Bachrach rate. Next, the immediate

percent response super

(2000) did not report empirical evidence on these visors unit of these 829 subordi

(the managers)

relationships. To our knowledge, only Chen, Hui, nates rated their subordinates'

in-role performance

and Sego (1998) have reported that supervisor and extra-role Of the 829 surveys, match

behavior.

rated organizational behaviors (OCBs)

citizenship ing unit manager surveys were returned for 636

predict subordinates' subsequent turnover. To the individuals our sample, 75.3 per

(76.7%). Within

extent that OCBs constitute a form of performance, cent were women; the overall average age was 34.2

however, our prior arguments in Hypotheses 3a =

years 9.9), and the average tenure with

(s.d. the

and 3b should hold for a moderating role of job was 6.6 = The

organization years (s.d. 5.1). major

embeddedness on the effects of OCBs on turnover

ity of respondents had "some college" (48.3%) or a

and absences as well. B.A. or B.S. degree (25.1%). Statistical comparisons

4a. On-the-job and off-the-job em between the sample and overall population (all em

Hypothesis

ployees within

the operations center) yielded no

beddedness moderate the negative effects of

on volun significant differences in age, gender, and tenure.

organizational citizenship behavior

In addition, no significant differences were found

tary employee turnover in such a way that

on turnover, job performance, and organizational

these effects are stronger for than for

higher across our five organizational

citizenship units.

lower on-the-job embeddedness.

Significant differences were found in absences in

Hypothesis 4b. On-the-job and off-the-job em one of our units; the other four units did not differ

beddedness moderate the negative effect of or in absences. Moreover, the ratings of the 20 super

ganizational citizenship on volitional absences visors whorated only a single subordinate were

in such a way that these effects are stronger for to a random of another 20

compared sample super

higher than for lower on-the-job embedded visors who rated multiple subordinates. No signif

ness. icant differences were found between supervisors'

ratings for one versus more subordinates on citizen

ship or job performance. These comparisons sug

METHODS

gest that sampling bias, although not completely

In early 1998, we contacted, visited, and gained discounted, was not a major

problem.

access to data at a regional operations center of a

large international financial institution. The local

Measures

labor market for this operations center was excep

tionally tight, with unemployment below 3 per Voluntary turnover. Each month of the year fol

cent. In September 1998, the two senior authors lowing administration of our survey, the host orga

conducted a focus group with ten randomly se nization a list of individuals who had

provided

lected employees, who discussed

how this study's voluntarily or involuntarily left the organization.

major variables might embed them in their jobs and One hundred thirty-six individuals were classified

community. From this focus group's information, as voluntary leavers (16.4%), and 12 others were

our surveys were tailored to this research terminated. To verify these lists, we

particular involuntarily

This content downloaded from 131.91.169.193 on Thu, 15 Aug 2013 09:20:18 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

716 October

Academy of Management Journal

tried to contact each person who was classified as a did Mitchell and colleagues (2001), we averaged

voluntary leaver. Seventy-two of the 136 voluntary items for on- and off-the-job embeddedness over

leavers were telephoned during the month follow their three subdimensions into composite scores

their and confirmed their = .84 and

ing quitting voluntary (a's .82, respectively).

leaving; the other 64 individuals could not be commitment was assessed with

Organizational

reached. In the analysis, were coded as 0

stayers eight items from Meyer and Allen's (1997) measure

and leavers as 1. of affective commitment. A sample item is "I enjoy

Volitional absences. Thehost organization pro my organization with outside of

discussing people

vided absenteeism records for the year following it." fob satisfaction was measured with three items.

administration of the survey. The organization clas A sample item is "All in all, I am satisfied with my

sified absences as paid (excused) or unpaid (unex Likert scales were used, and factor

job." Five-point

cused). Because we were concerned with volitional analyses indicated unidimensionality. Averaged

absences, our analysis focused on unpaid absences. were used in the analysis

composites (respective

The total number of monthly =

unpaid hours absent a's .85 and .86).

per employee was observed for the 12 months fol An factor analysis with varimax ro

exploratory

lowing the administration of the survey. We were tation was conducted on all items for

self-reported

able to obtain absentee data for 761 employees. job embeddedness, commitment,

organizational

Because some employees left the organization and job satisfaction. Visual of the scree

prior inspection

to the end of the 12-month observation an a three-factor solution. Items for job

period, plot suggested

average monthly absenteeism figure was calculated satisfaction, commitment, and the

organizational

for all persons. Our unpaid absence data also ex fit and sacrifice dimensions of on-the-job embed

hibited a positive skew and a kurtosis and lacked dedness "loaded" on factor 1 (however, one sacri

normality. In order to achieve better fitting and fice item did not load at all). All items for the fit

more normal distributional a square and sacrifice dimensions of off-the-job embedded

properties,

root transformation was ness loaded on factor 2. The links items for on- and

applied.

Organizational citizenship behavior. The im off-the-job embeddedness loaded on factor 3, ex

mediate supervisor of each survey respondent rated cept for two that did not load at all. Given their

the latter's citizenship behavior on eight items that the loading of all items for

conceptual overlap,

were adapted from the Van Dyne and LePine (1998) satisfaction,commitment, and on-the-job embed

organizational citizenship scale. Response options dedness, fit and sacrifice, onto a single factor was to

were 1 ("never") to 5 ("always"), and a sample item be expected and suggested some evidence for con

is "volunteers to do things that are not required." A vergent validity. The separate factors for off-the-job

total of 632 (76.2%) employees were rated. A factor embeddedness, fit and sacrifice, and for links sug

analysis indicated unidimensionality, and an aver gest some evidence of discriminant validity. (The

was used in the analysis = factor pattern matrix is available

aged composite [a .93). upon request to

Job performance. The participants' unit manag the senior author.)

ers assessed their job performance with the six-item Analyses. Logistic regression equations were cal

scale developed by Williams and Anderson (1991). culated for Hypotheses 1, 3a, 3b, and 4a, and ordi

Its response options were 1 ("never") to 5 ("al nary least squares (OLS) regressions were calcu

ways"), and a sample item is "performs all tasks lated for Hypotheses 2 and 4b. We examined the

that are expected of him or her." Job performance main underlying assumptions of all the statistical

ratings were completed for 632 of the employees tests of hypotheses and found no major violations

(76.2%). A factor analysis indicated unidimension (such as outliers, major deviations from normality,

ality, and an averaged composite was used in the or In the variance in

multicolinearity). particular,

=

analysis [a .92). flation factors for the regressions that contained

Job embeddedness. Although most items corre only "main effects" were all below 3. As expected,

sponded directly to Mitchell and associates' mea however, did emerge when in

multicollinearity

sure of job embeddedness, a few minor edits were teraction terms were entered into the regression

required to fit the measure to the current

sample's analyses.

setting. These changesincorporated unique "en

meshing" opportunities available to the employees RESULTS

within the host organization and its local commu

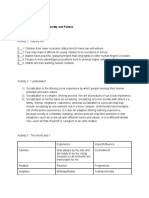

nity. In addition, additional items emerged from Table 1 shows the means, standard deviations,

the focus group and meetings with representative and correlations for all variables in this study. Off

employees, managers, and upper management. The and on-the-job embeddedness significantly related

Appendix shows all our embeddedness items. As to turnover, citizenship, performance, satisfaction,

This content downloaded from 131.91.169.193 on Thu, 15 Aug 2013 09:20:18 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

2004 Lee, Mitchell, Sablynski, Burton, and Holtom 717

TABLE 1

b

Means, Standard Deviations, and Correlations*'

Variable Mean s.d.

1. Voluntary turnover 0.16 0.37

2. Performance (in-role) 4.08 0.65 -.12**

3. OCB (extra-role) 3.07 0.88 -.08* .62***

-in-k * *

4. Volitional absences 3.49 7.43 .22***

5. On-the-job embeddedness 2.67 0.49 -.11** .11** .19*** .01

6. Off-the-job embeddedness 2.88 0.54 -.13*** .10** .11** -.16*** .33***

7. Job satisfaction 3.60 0.84 -.10** .02 .07 .03 .73*** .23***

8. Organizational commitment 2.91 0.71 -.09** .02 .06 .07 71 * * * .22*** .69***

a

n = 805

for column 1 (turnover); n > 809 for all other variables [n

> 623 for

performance and OCB).

b

Column 1 reports point-biserial correlations; all other columns report product-moment correlations (two-tailed tests of significance).

The correlations for volitional absences are based on square-root transformations.

* <

p .05

** <

p .01

< .001

***p

and commitment. Whereas off-the-job embedded reports the results of analyses of the hypothesized

ness did, on-the-job embeddedness did not relate direct effects, shows the regression of turnover onto

to volitional absences. satisfaction, commitment, and on- and off-the-job

significantly

embeddedness. As hypothesized, the coefficient for

off-the-job embeddedness is significant and shows

Tests of Hypotheses

a negative effect, whereas the coefficient for on-the

Hypothesis 1 holds that, when satisfaction and job embeddedness is nonsignificant. Equation 2

commitment are statistically controlled, off-the-job shows the regression of absences onto satisfaction,

embeddedness remains negatively related with commitment, and off- and on-the-job embedded

turnover and absences, whereas on-the-job embed ness. The coefficient for off-the-job embeddedness

dedness is unrelated. Equation 1 in Table 2, which is significant and negative, whereas the coefficient

TABLE 2

Effects of Job Embeddedness

Dependent Variables

Equation 1: Equation 2: Equation 4:

Voluntary Voluntary Equation 3: Organizational

Predictors Turnover3 Absences1* Job Performance1* Citizenship Behavior'1

Job satisfaction .91 .01 -.19** .10

Organizational commitment .92 .11* .06 .11

On-the-job embeddedness .80 -.02 .27*** .32***

Off-the-job embeddedness .60** -.18*** .07 .05

-

F or 2 log-likelihood 706.78 6.78*** 6.24*** 8.52***

R2 .04 .04 .05

AR2 or A*2

On-the-job embeddedness .02* .04*

Off-the-job embeddedness 7.75** .03*

17 805 739 620 620

a

Logistic regression. The entries are b's. Entries above 1.00 indicate effects, and entries below 1.00 indicate

exponentiated positive

negative effects.

b

The entries are standardized regression coefficients when all variables are entered into the equation.

* <

p .05

** <

p .01

< .001

***p

Two-tailed tests.

This content downloaded from 131.91.169.193 on Thu, 15 Aug 2013 09:20:18 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

718 Journal October

Academy of Management

for on-the-job embeddedness is nonsignificant. TABLE 3

Thus, Hypothesis 1 is supported. Moderating Effects of Job Embeddedness and

Hypothesis 2 holds that, when satisfaction and Work Behaviors on Voluntary Turnover3

commitment are controlled, on-the-job embedded

Predictors 1 Equation 2 Equation 3

ness remains positively related with citizenship

Equation

and performance, whereas off-the-job embedded 0.89 0.76

Job satisfaction 0.76

ness is unrelated. Equation 3 in Table 2 shows the 0.83 0.85 0.89

Organizational

regression of performance onto satisfaction, com commitment

and off- and on-the-job embeddedness. embeddedness 0.49 14.27 7.26*

mitment, On-the-job

**

Off-the-job embeddedness 0.68 0.09 0.09

As hypothesized, only the coefficient for on-the-job

Voluntary absences 0.60

embeddedness is significant and positive, whereas 0.89

Job performance

the coefficient for off-the-job embeddedness is not 0.78

Organizational

significant. Equation 4 shows the regression of cit citizenship behavior

izenship onto satisfaction, commitment, and off

and on-the-job embeddedness. The coefficient for

On-the-job embeddedness 1.37*

on-the-job embeddedness is significant and posi X absences

voluntary

tive, whereas the coefficient for off-the-job embed

Off-the-job embeddedness 1.01

dedness is not significant. Thus, Hypothesis 2 is X

voluntary absences

On-the-job embeddedness 0.50*

supported. X

3a predicts that on-the-job embed job performance

Hypothesis embeddedness 1.65

Off-the-job

dedness moderates the positive effect of volitional X

job performance

absences on quitting, and Hypothesis 3b predicts embeddedness 0.49*

On-the-job

that on-the-job embeddedness moderates the nega X

organizational

tive effect of job performance on quitting. In each citizenship behavior

Off-the-job embeddedness 1.92*

case the moderation is such that the effects are

X

organizational

stronger for higher than for lower on-the-job em

citizenship behavior

beddedness. Equation 1 in Table 3, which reports

the results of analyses of the hypothesized moder

ation effects, shows the regression of turnover onto -2 log-likelihood 622.92 505.40 504.80

on- and off-the-job em A#2b 6.05* 4.82+ 11.15***

satisfaction, commitment, n

740 621 621

beddedness, absences, and the interactions be

tween on-the-job embeddedness and absences and a

Logistic regressions. The entries are exponentiated b's. En

between off-the-job embeddedness and absences. tries above 1.00 indicate positive effects, and entries below 1.00

As hypothesized, the coefficient for the interaction indicate negative effects.

b

For interactions.

between on-the-job embeddedness and absences is +

p < .10

statistically significant and shows a positive effect, * < .05

p

whereas the interaction between off-the-job embed **p

< .01

*** <

dedness and absences is nonsignificant. To de p .001

scribe this interaction, we calculated re Two-tailed tests.

separate

gressions for high and low groups based on a

median split of on-the-job embeddedness. The high low groups based on a median split of on-the-job

group has a steeper positive slope than the low embeddedness. The high group has a negative and

on turnover = = <

group for absences regressed (exp b significant slope (exp b 0.41, p .001), whereas

1.63, p < .001, vs. 1.27, p < .01). Equation 2 in the low group has a negative but nonsignificant

Table 3 shows the regression of turnover onto sat slope for performance regressed on turnover. Thus,

isfaction, commitment, on- and off-the-job embed Hypotheses 3a and 3b are supported.

dedness, performance, and the interactions be Hypothesis 4a predicts that on- and off-the-job

tween on-the-job embeddedness and performance embeddedness moderate the negative effect of or

and between embeddedness and perfor on quitting (turnover), and

off-the-job ganizational citizenship

mance. The coefficient for the interaction between Hypothesis 4b makes a similar prediction for voli

on-the-job embeddedness and performance is sig tional absences. In both cases, the moderation is

nificant and shows a negative effect, whereas the such that these effects are stronger for higher than

coefficient interaction

for the between off-the-job for lower on-the-job embeddedness. In Table 3,

embeddedness and performance is nonsignificant. equation 3 shows the regression of turnover onto

To describe the significant interaction, we calcu satisfaction, commitment, on- and off-the-job em

lated separate regression equations for high and beddedness, citizenship, and the interactions be

This content downloaded from 131.91.169.193 on Thu, 15 Aug 2013 09:20:18 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

2004 Lee, Mitchell, Burton, and Holtom 719

Sablynski,

tween embeddedness and citizenship dedness, and off-the-job embeddedness) with the

on-the-job

and between off-the-job embeddedness and citizen variance explained in the corresponding regres

As the coefficients for the in sions containing satisfaction, commitment, and

ship. hypothesized,

teractions between on-the-job embeddedness and overall embeddedness. For the corresponding lo

and between embeddedness gistic regression analyses, we compared d?viances

citizenship off-the-job

and citizenship are statistically To de from these two equations with a G-test (Hosmer &

significant.

scribe these interactions, we calculated separate Lemeshow, 2000). To reiterate, the new regressions

for high and low groups based on a (both the OLS and logistic versions), with their

regressions

median split of both on- and off-the-job embedded coefficients for overall embeddedness, allowed for

ness. For the high on-the-job embeddedness group, stronger inferences on the strength of predictions.

the slope for citizenship on turnover is For absences, the four-variable model explained 4

regressed

b = < of variance = whereas the three

negative and significant (exp 0.55, p .01), percent [R2 .04),

3 percent =

whereas the slope for the low group is nonsignifi variable model explained [R2 .03; both

cant. For the high off-the-job embeddedness group, p < .001). The difference between the two R2s was

on turnover = < a

the slope for citizenship regressed is significant [F 3.20, p .05, with one-tailed test,

nonsignificant, whereas the slope for the low group but p < .10, with a two-tailed test). For perfor

=

is negative and significant (exp b 0.65, p < .05). mance, the four- and three-variable models had the

Thus, Hypothesis 4a is supported. same respective explained variances as the models

For Hypothesis 4b, absences were regressed onto for absences (both p < .001). The difference in ?2s

on- and off-the-job em was - < .05 with one- and

satisfaction, commitment, significant [F 6.01, p

beddedness, and the interactions between on-the two-tailed tests). For citizenship, the four-variable

job embeddedness and citizenship and between model explained 5 percent of variance, and the

embeddedness and (This re three-variable model, 4 (both p < .001).

off-the-job citizenship. percent

not is The difference in fl2s was =

gression is shown but available upon request significant (F 11.51,

to the senior author.) Only the interaction for on p < .001, with one- and two-tailed tests). For turn

the-job embeddedness and citizenship is statisti over, the four-variable model had -2 log-likelihood

=

cally significant (? -0.56, p < .05). To describe of 706.78, whereas the three-variable model had a

this interaction, we calculated separate regression -2 log-likelihood of 707.31. The difference be

equations for high and low groups based on a me tween them (G) was nonsignificant. In sum, these

dian split of on-the-job embeddedness. The high data generally support the stronger inferences.

group showed a negative and significant slope that

was steeper than the low group's = =

(? -0.19, p DISCUSSION

.001, vs. -0.12, p < .05). Thus, Hypothesis 4b is

only partially supported. This study expands understanding of job embed

dedness. First, off-the-job embeddedness predicted

turnover and absences, whereas on-the-job embed

dedness did not (Hypothesis 1). In contrast, on-the

Post Hoc Analyses

job embeddedness predicted organizational citi

Table 2 shows different

patterns of significant zenship and job performance, whereas off-the-job

contribution towardprediction of turnover, ab embeddedness did not (Hypothesis 2). Second, the

sences, performance, and citizenship for on- and two components of job embeddedness may be pro

off-the-job embeddedness. Post hoc, we tested the cesses through which the decisions to perform and

stronger inferences that off-the-job embeddedness to participate can be conceptually and empirically

is a better predictor than on-the-job embeddedness linked. On-the-job embeddedness moderated the

for turnover and absences and that on-the-job em positive effect of volitional absences on turnover

beddedness is a better predictor than off-the-job (Hypothesis 3a), the negative effect of job perfor

embeddedness for performance and citizenship. mance on turnover (Hypothesis 3b), and the nega

First, by adding scores for on- and off-the-job em tive effect of citizenship on absences; the modera

beddedness we created an overall

job embedded tion was such that these effects were stronger for

ness score. Second, we

regressed each dependent higher than for lower on-the-job embeddedness

variable onto the predictors of satisfaction, commit (Hypothesis 4a).

ment, and overall embeddedness. Third, we com Three particular limitations of this study should

pared the difference in variance explained [R2) in be noted. First, the timing for some of our measures

the three OLS regressions shown in Table 2 (that is, provides only limited support for causal infer

predicting absences, performance, and citizenship ences. Although our four behavioral outcome vari

with satisfaction, commitment, on-the-job embed ables were measured independently from and after

This content downloaded from 131.91.169.193 on Thu, 15 Aug 2013 09:20:18 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

720 Journal October

Academy of Management

our respondents' of satisfaction, com that measure

self-reports job embeddedness immediately be

mitment, and embeddedness, organizational citi fore and after acts of organizational citizenship and

zenship and job performance were only a

assessed formal appraisals of in-role performance, absence

month after the self-reported survey. Although it is spells, or individual quitting might yield valuable

likely that job embeddedness was a cause of our evidence on causal effects.

outcome variables, the reverse direction may hold. In our view, the managerial of this

implications

Second, the measures of on- and off-the-job embed study are clear. Job embeddedness (which can be

dedness are still preliminary and evolving. Al established through building community, develop

though our data on factor structures and internal ing a sense of belonging, ties

establishing deep

consistencies produce empirical findings similar to among employees, and deepening social capital)

earlier work, these measures are not yet established may increase retention, attendance, citizenship,

and standard researchinstruments. Third, we dis and job performance. Furthermore, organizations

aggregated embeddedness into on- and off-the job can be proactive about job embeddedness: links can

components. In the future, profiles of the six em be increased through teams and long-term projects;

beddedness dimensions may be useful for predic sacrifice can be increased by connecting job and

tion and understanding. organizational rewards to longevity; and fit can be

It should be mentioned that Meyer and Allen's increased by matching employees' knowledge,

(1997) dimension of continuance commitment and skills, and attitudes with

abilities, a job's require

the embeddedness subdimension of organization ments. Equally important, managers can increase

related sacrifice (sacrifice?organization) are simi off-the-job embeddedness by providing people

lar. Both dimensions share notions of "sunk cost" with information about the community surround

and reluctance to give things up by leaving. How ing their workplace and by providing social sup

ever, the original continuance commitment con port for local activities and events (Mitchell, Hol

struct combined reluctance with the availability of tom, & Lee, 2001).

alternatives, which organization-related sacrifice In closing, our results suggest that studying em

does not. Even if items for alternatives are omitted reasons for both and

ployees' staying leaving may

from the continuous commitment measure, items enrich knowledge of retention, increasing it beyond

for organization-related sacrifice have much more what the current focus on leaving permits. This

specific and targeted referents such as perks, re broader perspective suggests an interesting and po

spect, compensation, benefits

(retirement and tentially fruitful direction for future research.

health care), and promotional opportunities. Thus,

our measure omits the "alternatives" idea and of

fers more detail in terms of the specific REFERENCES

topics than

continuance commitment. (See Yao, Lee, Mitchell, X. &

Chen, P., Hui, C, Seg?, D. J. 1998. The role of

Burton, and Sablynski [2004] for a comprehensive organizational citizenship behavior in turnover:

comparison between job embeddedness and related Conceptualization and preliminary test of key hy

constructs, continuance commitment.) potheses. Journal of Applied Psychology, 83: 922

including

our results indicate the appropriateness 931.

Overall,

of studying retention and performance as tandem Gouldner, A. W. 1960. The norm of A pre

reciprocity:

job behaviors and viewing job embeddedness as a liminary statement. American Sociological Re

meaningful mechanism through which to under view, 25: 161-178.

stand this linkage. In particular, Mitchell and co Griffeth, R. W., Horn, P. W., & Gaertner, S. 2000. A meta

authors (2001) reported significant predictive asso of antecedents and correlates of

analysis employee

ciations between aggregated job embeddedness and turnover:

Update, moderator tests, and research im

turnover in two In this study, disaggre plications for the millennium. Journal of Manage

samples.

embeddedness ab ment, 26: 463-488.

gated job predicted turnover,

sences, in-role performance, and organizational cit Hanish, K. A., & Hulin, C. L. 1991. General attitudes and

izenship. Thus, meaningful statistical effects were organizational withdrawal: an evaluation of a causal

found over three diverse and sizable In model. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 39: 110

samples.

the future, itmay be timely for researchers to move 128.

beyond simple prediction and predictive validity Holtom, B. C, Lee, T. W., & Tidd, S. T. 2002. The rela

designs. Given the existing studies, research de tionship between work status congruence and work

that allow for stronger causal inferences are related attitudes and behaviors. Journal of Applied

signs

now needed. Field or quasi field experiments that Psychology, 87: 903-915.

include interventions aimed at altering job embed Horn, P. W., & Griffeth, R. W. 1995. Employee turnover.

dedness are suggested. Alternatively, field studies Cincinnati: South-Western.

This content downloaded from 131.91.169.193 on Thu, 15 Aug 2013 09:20:18 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

2004 Lee, Mitchell, Burton, and Holtom 721

Sablynski,

Hosmer, D. W., & Lemeshow, S. 2000. Applied logistic Van Dyne, L., Cummings, L. L., &McLean Parks, J. 1995.

regression (2nd ed.). New York: Wiley. Extra-role behaviors: In pursuit of construct and def

C. L. 1998. constructs time: Pot

initional clarity (a bridge over muddied waters). In

Hulin, Behaviors, and

L. L. Cummings & B. M. Staw (Eds.), Research in

holes on the road well traveled. Invited address,

behavior, vol. 17: 215-285. Green

annual meeting of the Society for Industrial and organizational

wich, CT: JAI Press.

Organizational Psychology, Dallas.

Williams, L. J., & Anderson, S. E. 1991. Job satisfaction

Hulin, C. L. 1991. and commit

Adaptation, persistence

and commitment as of cit

ment in In M. D. Dunnette & L. M. organizational predictors

organizations.

izenship and in-role behaviors. Journal of Manage

Hough (Eds.), Handbook

of industrial and organi

ment, 17: 601-617.

zational psychology (2nd ed.): 445-507. Palo Alto,

CA: Consulting Psychologists Press. Yao, X., Lee, T. W., Mitchell, T. R., Burton, J. P., &

Hulin, C. L. 2002. Lessons from industrial and organiza Sablynski, C. S. 2004. Job embeddedness: Current

research and future directions. In R. Griffeth & P.

tional psychology. In J. Brett & F. Drasgow (Eds.),

Horn (Eds.), Understanding employee retention

The psychology of work: Theoretically based em

and turnover: 153-187. Greenwich, CT: Information

pirical evidence. Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum.

Age.

Lee, T. W., & Mitchell, T. R. 1994. An alternative ap

proach: The unfolding model of voluntary employee APPENDIX

turnover. Academy Review, 19:

of Management

51-89.

Job Embeddedness Itemsa

Lee, T. W., Mitchell, T. R., Holtom, B. C, McDaniel, L., & Fit, community

Hill, J.W. 1999. Theoretical development and exten I really love the place where I live.b

sion of the unfolding model of voluntary turnover. I like the family-oriented environment of my

Academy of Management Journal, 42: 450-462. community.

This community I live in is a good match for me.

Maertz, C. P., & Campion, M. A. 1998. 25 years of volun

I think of the community where I live as home.b

tary turnover research: A review and Inter

critique. The area where I live offers the leisure activities that

national Review of Industrial and Organizational

I like sports, outdoors, cultural, arts).

(e.g.,

Psychology, 13: 49-81.

March, J. G, & Simon, H. A. 1958. Organizations. New Fit, organization

York: Wiley. My job utilizes my skills and talents well.b

I feel like I am a good match for this organization.13

Meyer, J. P., & Allen, N. J. 1997. Commitment in the

I feel personally valued by (name of the

workplace: Theory, research, and application.

Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. organization).

I like my work schedule (e.g., flextime, shift).

Mitchell, T. R., Holtom, B. C, & Lee, T. W. 2001. How to I fit with this organization's culture.b

keep your best employees: The development of an I like the authority and responsibility I have at this

effective attachment policy. Academy of Manage company.13

ment Executive, 15(4): 96-108.

Mitchell, T. R., Holtom, B. C, Lee, T. W., C. J., Links, community

Sablynski,

& Erez, M. 2001. Why Are married?b

people stay: Using job embed you currently

to If you are married, does your spouse work outside

dedness turnover.

predict voluntary Academy of

44: 1102-1121. the home?b

Management Journal,

Do you own the home you live in? (mortgaged or

Podsakoff, P. M., MacKenzie, S. B., Pain, J. B., & Bach

outright)

rach, D. G. 2000. behav

Organizational citizenship

My family roots are in the community where I live.

iors: A critical review of the theoretical and empiri

cal literature and suggestions for future research.

Links, organization

Journal of Management, 26: 513-564. How long have you been in your present position?

Rhoades, L., & Eisenberger, R. 2002. Perceived (years)b

organiza

tional support: A review of the literature. Journal How long have you worked for this organization?

of

Applied Psychology, 87: 698-714. (years).b

How long have you worked in the (banking)

Van Dyne, L., & Ang, S. 1998. Organizational citizenship

behavior of contingent workers in Singapore. Acad industry? (years).b

How many coworkers do you interact with

emy of Management Journal, 41: 692-703.

regularly?b

Van Dyne, L., & LePine, J. A. 1998. Helping and voice How many coworkers are highly dependent on you?b

extra-role behaviors: Evidence of construct and pre How work teams are on?b

many you

dictive validity. Academy of Management Journal, How many work committees are you on?b

41: 108-119. Continued

This content downloaded from 131.91.169.193 on Thu, 15 Aug 2013 09:20:18 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

722 Academy of Management Journal October

APPENDIX Continued A

Sacrifice, community

Leaving this community would be very hard.b Thomas W. Lee (orcas@u.washington.edu) is a professor

me a lot in my of human resource and be

People respect community.13 management organizational

My neighborhood is safe.b havior and the Evert McCabe Faculty Fellow at the Uni

versity of Washington Business School. He earned his

Sacrifice, organization Ph.D. in organizational studies at the University of Ore

I have a lot of freedom on this job to decide how to gon. His current research interests include employee

re

pursue my goals.b tention, staffing, work motivation, and research methods.

The perks on this job are outstanding.13

Terence R. Mitchell (trm@u.washington.edu) is the Ed

I feel that people at work respect me a great deal.b

ward E. Carlson Professor of Business Administration

Iwould incur very few costs if I left this

and a professor of psychology at the University of Wash

organization.0

ington Business School. He earned his Ph.D. in social

Iwould sacrifice a lot if I left this job.b

psychology at the University of Illinois. His current re

are excellent here.b

My promotional opportunities

search interests include employee retention, work moti

I am well for my level of

compensated performance.13

vation, and decision making.

The benefits are good on this job.b

I believe the prospects for continuing employment Chris J. Sablynski is an assistant

(sablynsk@csus.edu)

with this are excellent.13 of behavior and environment at

company professor organizational

California State University, Sacramento. He earned his

a

Items 1-3 for links, community, and links, organization, Ph.D. in behavior and human resource

organizational

were standardized before being analyzed or included in any

management at the University of Washington Business

composites. School. His current research interests include employee

b

Item used by Mitchell, Holtom, Lee, Sablynski, and Erez retention and deviance.

workplace

(2001).

c is an assistant

Reverse coded. James P. Burton (jburton@uwb.edu) pro

fessor of management at the University of Washington,

Bothell. He earned his Ph.D. in organizational behavior

and human resource management at the of

University

Business School. His current research inter

Washington

ests include fairness, retention, and

workplace employee

teaching effectiveness in university settings.

Brooks C. Holtom (bch6@msb.edu) is an assistant profes

sor of management in the McDonough School of Business

at Georgetown University. He earned his Ph.D. in orga

nizational behavior and human resource at

management

the University of Washington Business School. His cur

rent research interests include human and social capital

development and employee retention.

This content downloaded from 131.91.169.193 on Thu, 15 Aug 2013 09:20:18 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

You might also like

- Relationship Between Employee Engagement and Turnover Intention - An Empirical Evidence.Document15 pagesRelationship Between Employee Engagement and Turnover Intention - An Empirical Evidence.patrick Mutihinda Bambe BanonNo ratings yet

- Job EmbeddednessDocument28 pagesJob EmbeddednessHarsh KhemkaNo ratings yet

- Handbook of Zen, Mindfulness and Spiritual Health PDFDocument324 pagesHandbook of Zen, Mindfulness and Spiritual Health PDFMatthew Grayson100% (3)

- A Review of Job Embeddedness:: Conceptual, Measurement, and Relative Study ConclusionsDocument5 pagesA Review of Job Embeddedness:: Conceptual, Measurement, and Relative Study Conclusionsmamdouh mohamedNo ratings yet

- Jain University Bharathraj Shetty A K (Phdaug2011-93)Document55 pagesJain University Bharathraj Shetty A K (Phdaug2011-93)পার্থপ্রতীমদওNo ratings yet

- Proactive and Creative BehaviorDocument13 pagesProactive and Creative Behavioragus mustofaNo ratings yet

- Bolino Et Al (2002) Citizenship Behavior and The Creation of Social Capital in OrganizationsDocument19 pagesBolino Et Al (2002) Citizenship Behavior and The Creation of Social Capital in OrganizationsMiguelNo ratings yet

- Why People Stay: Using Job Embeddedness To Predict Voluntary TurnoverDocument21 pagesWhy People Stay: Using Job Embeddedness To Predict Voluntary TurnoverTie MieNo ratings yet

- Job Engagement: Antecedents and Effects On Job PerformanceDocument19 pagesJob Engagement: Antecedents and Effects On Job PerformanceMuhammad Ali BhattiNo ratings yet

- Antecedents and Consequences of Employee Engagement (2006, Saks, A. M.)Document21 pagesAntecedents and Consequences of Employee Engagement (2006, Saks, A. M.)John GrahamNo ratings yet

- Antecedents and Consequences of Employee EngagemenDocument21 pagesAntecedents and Consequences of Employee EngagemenkanikamleshNo ratings yet

- Relations Industrielles Industrial Relations: Olivier Doucet, Gilles Simard and Michel TremblayDocument24 pagesRelations Industrielles Industrial Relations: Olivier Doucet, Gilles Simard and Michel Tremblaymanga avini gael fabriceNo ratings yet

- Organi Zationa L Behavi OURDocument4 pagesOrgani Zationa L Behavi OURhaseeb ahmedNo ratings yet

- The Role of Organizational Citizenship Behavior in Turnover: Conceptualization and Preliminary Tests of Key HypothesesDocument10 pagesThe Role of Organizational Citizenship Behavior in Turnover: Conceptualization and Preliminary Tests of Key HypothesesJavaid Ali ShahNo ratings yet

- Konsekuensi ManajemenDocument21 pagesKonsekuensi Manajemenanita theresiaNo ratings yet

- Job Stress and Employee Behaviors 1Document15 pagesJob Stress and Employee Behaviors 1Onii ChanNo ratings yet

- 10 1108 - Lodj 01 2012 0014Document17 pages10 1108 - Lodj 01 2012 0014mamdouh mohamedNo ratings yet

- Jiang, Liu, McKay, Lee, Mitchell, 2012, When and How Is Job Embeddedness Predictive of TurnoverDocument20 pagesJiang, Liu, McKay, Lee, Mitchell, 2012, When and How Is Job Embeddedness Predictive of TurnoverFanny MartdiantyNo ratings yet

- Brownand Leigh 1996Document13 pagesBrownand Leigh 1996Egle UselieneNo ratings yet

- Hill Et All Defining FlexDocument17 pagesHill Et All Defining FlexghcghNo ratings yet

- Barley 2001 Bringing Work Back in OrganizationsDocument21 pagesBarley 2001 Bringing Work Back in OrganizationsNanNo ratings yet

- Chen Ferris Kwan Yan Zhou Hong 2013Document22 pagesChen Ferris Kwan Yan Zhou Hong 2013Michelle PorterNo ratings yet

- Keterlibatan KerjaDocument16 pagesKeterlibatan KerjaBaharudin BahrinNo ratings yet

- Organizational DevelopmentDocument12 pagesOrganizational DevelopmentLuisa Fernanda ClavijoNo ratings yet

- How Does Bureaucracy Impact Individual C PDFDocument19 pagesHow Does Bureaucracy Impact Individual C PDFMeseretNo ratings yet

- Fpsyg 12 552581Document13 pagesFpsyg 12 552581Lucia CristinaNo ratings yet

- Fardapaper Perceptions of Organizational Politics Knowledge Hiding and Employee Creativity The Moderating Role of Professional CommitmentDocument6 pagesFardapaper Perceptions of Organizational Politics Knowledge Hiding and Employee Creativity The Moderating Role of Professional CommitmentDR. Mahmoud DwedarNo ratings yet

- Burnout and Engagement BIG 5Document9 pagesBurnout and Engagement BIG 5Smitha ShankarNo ratings yet

- Determent's of Employee's Engagement in Bank IndustryDocument9 pagesDeterment's of Employee's Engagement in Bank IndustryNSRanganathNo ratings yet

- Yuan & Woodman (2010)Document21 pagesYuan & Woodman (2010)Marielle LituanasNo ratings yet

- Chang2009 PDFDocument24 pagesChang2009 PDFJawad AliNo ratings yet

- Organizational Commitment, Supervisory Commitment, and Employee Outcomes in The Chinese Context: Proximal Hypothesis or Global Hypothesis?Document22 pagesOrganizational Commitment, Supervisory Commitment, and Employee Outcomes in The Chinese Context: Proximal Hypothesis or Global Hypothesis?Phuoc NguyenNo ratings yet

- Jackson Et Al. - 1991 - Some Differences Make A Difference Individual DisDocument14 pagesJackson Et Al. - 1991 - Some Differences Make A Difference Individual DisRMADVNo ratings yet

- Relationship Between Psychological Climate and Turnover Intentions and Its Impact On Organisational Effectiveness: A Study in Indian OrganisationsDocument9 pagesRelationship Between Psychological Climate and Turnover Intentions and Its Impact On Organisational Effectiveness: A Study in Indian OrganisationsFarhan PhotoState & ComposingNo ratings yet

- Organizational RolesDocument18 pagesOrganizational RolesFabiano Pires de OliveiraNo ratings yet

- Changes in The Frequency of Coworker Incivility - Roles of Work Hours, Workplace Sex Ratio, Supervisor Leadership Style, and IncivilityDocument13 pagesChanges in The Frequency of Coworker Incivility - Roles of Work Hours, Workplace Sex Ratio, Supervisor Leadership Style, and Incivilitytâm đỗ uyênNo ratings yet

- Structure of Organizational Commitment and Job Engagement by Exploratory Factor AnalysisDocument8 pagesStructure of Organizational Commitment and Job Engagement by Exploratory Factor Analysisilham rosyadiNo ratings yet

- Attachment TheoryDocument16 pagesAttachment Theoryfayçal chehabNo ratings yet

- Human - Ijhrm - Employee Engagement-T. S PrasannaDocument6 pagesHuman - Ijhrm - Employee Engagement-T. S Prasannaiaset123No ratings yet

- Article 1Document10 pagesArticle 1Srirang JhaNo ratings yet

- Study of Organizational Members BurnoutDocument16 pagesStudy of Organizational Members BurnoutexponentialdoctorNo ratings yet

- Bernerth 2020 JBRDocument10 pagesBernerth 2020 JBRZerohedge JanitorNo ratings yet

- Job Engagement Antecedents and Effects On Job PerformanceDocument20 pagesJob Engagement Antecedents and Effects On Job Performance91akshathNo ratings yet

- Akhtar 2015Document6 pagesAkhtar 2015Loredana LaviniaNo ratings yet

- Trust Research PaperDocument21 pagesTrust Research PapermocksnapNo ratings yet

- Stevens Beyer Trice1978Document18 pagesStevens Beyer Trice1978Robert BagarićNo ratings yet

- Staw TheoryDocument10 pagesStaw TheorySerien SeaNo ratings yet

- Effect of Workplace Incivility On OCB Through BurnoutDocument14 pagesEffect of Workplace Incivility On OCB Through BurnoutDuaa ZahraNo ratings yet

- Work Engagement: Evolution of The Concept and A New InventoryDocument27 pagesWork Engagement: Evolution of The Concept and A New InventoryADITYA RANJANNo ratings yet

- Impact of Employee Engagement On Organization Citizenship BehaviourDocument9 pagesImpact of Employee Engagement On Organization Citizenship BehaviourSadhika KatiyarNo ratings yet

- J Organ Behavior - 2024 - Dhanani - Inclusion Near and Far A Qualitative Investigation of Inclusive OrganizationalDocument18 pagesJ Organ Behavior - 2024 - Dhanani - Inclusion Near and Far A Qualitative Investigation of Inclusive Organizationalrafaeladuarte01No ratings yet

- JMP200419 169 81Document14 pagesJMP200419 169 81Jamburano PizzariaNo ratings yet

- Synthesizing Content Models of Employee Turnover PDFDocument17 pagesSynthesizing Content Models of Employee Turnover PDFIqhsan IbrNo ratings yet

- Lawrence Et Al 2010 Institutional Work Refocusing Institutional Studies of OrganizationDocument7 pagesLawrence Et Al 2010 Institutional Work Refocusing Institutional Studies of OrganizationBettina D'AlessandroNo ratings yet

- A Very Good ArticleDocument8 pagesA Very Good ArticleridaNo ratings yet

- An Overview of Job Embeddedness: A Review StudyDocument3 pagesAn Overview of Job Embeddedness: A Review StudyInternational Journal of Innovative Science and Research TechnologyNo ratings yet

- Big Five Personality Traits in The Workplace - Investigating Personality Differences Between Employees, Supervisors, Managers, and EntrepreneursDocument8 pagesBig Five Personality Traits in The Workplace - Investigating Personality Differences Between Employees, Supervisors, Managers, and EntrepreneursJoão VitorNo ratings yet

- Grounded ConfucianDocument8 pagesGrounded ConfucianjmtimbolNo ratings yet

- OB Art 4Document31 pagesOB Art 4ahinavNo ratings yet

- Strategic Planning Research Toward A Theory Driven AgendaDocument4 pagesStrategic Planning Research Toward A Theory Driven AgendaArare Abdisa100% (1)

- Jhana Grove Retreat Selected Q&ADocument311 pagesJhana Grove Retreat Selected Q&ACNo ratings yet

- Introduction To Community B.SC Ii Yr CHNDocument77 pagesIntroduction To Community B.SC Ii Yr CHNJOSEPH IVO A. AGUINALDONo ratings yet

- Lesson Plan and Observation: Alverno CollegeDocument3 pagesLesson Plan and Observation: Alverno Collegeapi-140174622No ratings yet

- Journal of Business Research: Cayetano Medina-Molina, Manuel Rey-Moreno, Rafael Peri A Nez-Crist ObalDocument7 pagesJournal of Business Research: Cayetano Medina-Molina, Manuel Rey-Moreno, Rafael Peri A Nez-Crist Obalkings manNo ratings yet

- Exploring Health Beliefs and Determinants of HealthDocument8 pagesExploring Health Beliefs and Determinants of Healthapi-283575067No ratings yet

- Music, Meaning, and The Brain Comment On "Towards A Neural Basis of Processing Musical Semantics" by Stefan KoelschDocument2 pagesMusic, Meaning, and The Brain Comment On "Towards A Neural Basis of Processing Musical Semantics" by Stefan KoelschTlaloc GonzalezNo ratings yet

- What Are Learning DisabilitiesDocument4 pagesWhat Are Learning DisabilitiesSiyad SiddiqueNo ratings yet

- Camera Shots AS Media G322Document13 pagesCamera Shots AS Media G322Ms-CalverNo ratings yet

- Session No. 2 - Cultural Environment and International BusinessDocument23 pagesSession No. 2 - Cultural Environment and International BusinessHeshan Nikitha AmarasinghaNo ratings yet

- The Theory of Conceptual FieldsDocument12 pagesThe Theory of Conceptual FieldsAmerika Sánchez LeónNo ratings yet

- EGE 3103 Engineer & SocietyDocument19 pagesEGE 3103 Engineer & SocietyYousab CreatorNo ratings yet

- Forgiveness As Repairing An Internal Object Relationship - Ronald BrittonDocument8 pagesForgiveness As Repairing An Internal Object Relationship - Ronald BrittonMădălina Silaghi100% (1)

- Review of The CMHTs in Kingston For Adults of Working AgeDocument48 pagesReview of The CMHTs in Kingston For Adults of Working AgechomiziNo ratings yet

- Chapter Five: Exploratory Research Design: Qualitative ResearchDocument49 pagesChapter Five: Exploratory Research Design: Qualitative ResearchMuhammad AreebNo ratings yet

- ASSIGNMENT 1 Henri Fayols 14 PrincipleDocument55 pagesASSIGNMENT 1 Henri Fayols 14 PrincipleMuhammadFarhanShakeeNo ratings yet

- Nonaka and TakeuchiDocument10 pagesNonaka and TakeuchimainartNo ratings yet

- Oral Communication Week 1 Module 1Document15 pagesOral Communication Week 1 Module 1Derley Hanne Cubacub100% (1)

- Naranjo - Supressive TechniquesDocument14 pagesNaranjo - Supressive TechniquestamaraNo ratings yet

- Issues & Debates Essay PlansDocument21 pagesIssues & Debates Essay Planstemioladeji04100% (1)

- Grade 8 Araling Panlipunan SyllabusDocument10 pagesGrade 8 Araling Panlipunan SyllabusIanBesina100% (2)

- Card Template Form 138Document2 pagesCard Template Form 138Amie Azcona Pasustento100% (2)

- Pathways Rw4 2e U9 TestDocument16 pagesPathways Rw4 2e U9 TestĐỗ Viết Hà TXA2HNNo ratings yet

- Limitations and Criticisms of The Cognitive Behavioral ApproachesDocument5 pagesLimitations and Criticisms of The Cognitive Behavioral ApproachesKaanesa Moorthy100% (1)

- The Author's Profile: Motivation and InspirationDocument3 pagesThe Author's Profile: Motivation and InspirationKathie De Leon VerceluzNo ratings yet

- Course Outline Fall 2022 MBA - Business CommunicationDocument6 pagesCourse Outline Fall 2022 MBA - Business CommunicationSaman KhanNo ratings yet

- 03.HG Theories of Child BehaviorDocument9 pages03.HG Theories of Child BehaviorEthel KanadaNo ratings yet

- Anya S. Salik G12-STEM - Sison Understanding Culture, Society and Politics Quarter 1 - Module 5Document3 pagesAnya S. Salik G12-STEM - Sison Understanding Culture, Society and Politics Quarter 1 - Module 5Naila SalikNo ratings yet

- Shift Leadership ResponsibilityDocument3 pagesShift Leadership ResponsibilityRandolph LatimerNo ratings yet