Professional Documents

Culture Documents

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

26 viewsStraubhaar Et Al 2013 - Inequity in The Technopolis Ch4

Straubhaar Et Al 2013 - Inequity in The Technopolis Ch4

Uploaded by

cowjatexas

austin

digital divide

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF or read online from Scribd

You might also like

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5820)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1093)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (852)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (590)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (898)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (540)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (349)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (822)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (122)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (403)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- Cottom - The Hustle Economy - Dissent MagazineDocument6 pagesCottom - The Hustle Economy - Dissent MagazinecowjaNo ratings yet

- Twitter's Doubling of Character Count From 140 To 280 Had Little Impact On Length of Tweets - TechCrunchDocument2 pagesTwitter's Doubling of Character Count From 140 To 280 Had Little Impact On Length of Tweets - TechCrunchcowjaNo ratings yet

- Dril Is Everyone. More Specifically, He's A Guy Named Paul. - The RingerDocument20 pagesDril Is Everyone. More Specifically, He's A Guy Named Paul. - The RingercowjaNo ratings yet

- New Associated Press Guidelines - Keep It Brief - The Washington PostDocument2 pagesNew Associated Press Guidelines - Keep It Brief - The Washington PostcowjaNo ratings yet

- Ross - The Record Effect - The New YorkerDocument18 pagesRoss - The Record Effect - The New YorkercowjaNo ratings yet

- Christgau - Living Without The BeatlesDocument10 pagesChristgau - Living Without The BeatlescowjaNo ratings yet

- Berthoff - Learning The Uses of ChaosDocument3 pagesBerthoff - Learning The Uses of ChaoscowjaNo ratings yet

- Robert Christgau - Rock Lyrics Are Poetry (Maybe)Document6 pagesRobert Christgau - Rock Lyrics Are Poetry (Maybe)cowjaNo ratings yet

- Neofeudalism - The End of Capitalism - Los Angeles Review of BooksDocument22 pagesNeofeudalism - The End of Capitalism - Los Angeles Review of Bookscowja100% (1)

- Eno - Axis ThinkingDocument6 pagesEno - Axis ThinkingcowjaNo ratings yet

- Fulton Babicke - Impediments To Productive Argument Rhetorical DecayDocument18 pagesFulton Babicke - Impediments To Productive Argument Rhetorical DecaycowjaNo ratings yet

- Badiou - Lacan and The Pre-SocraticsDocument4 pagesBadiou - Lacan and The Pre-SocraticscowjaNo ratings yet

- DiCaglio - Language and The Logic of Subjectivity - Whitehead and Burke in CrisisDocument24 pagesDiCaglio - Language and The Logic of Subjectivity - Whitehead and Burke in CrisiscowjaNo ratings yet

- Kinsella - Critiques of Reflective PracticeDocument4 pagesKinsella - Critiques of Reflective PracticecowjaNo ratings yet

- Aoki - Letters From Lacan Reading and The MathemeDocument310 pagesAoki - Letters From Lacan Reading and The MathemecowjaNo ratings yet

- The Declaration of Independence - The Mystery of The Lost OriginalDocument31 pagesThe Declaration of Independence - The Mystery of The Lost OriginalcowjaNo ratings yet

- CTA Case No. 10063Document16 pagesCTA Case No. 10063Karen Joy JavierNo ratings yet

- Webb vs. de LeonDocument22 pagesWebb vs. de LeonIyaNo ratings yet

- Employment Application: State of Utah Department of Workforce ServicesDocument3 pagesEmployment Application: State of Utah Department of Workforce Servicesapi-283418026No ratings yet

- Notes On The Ninth Degree of AMORC With Additional CommentaryDocument17 pagesNotes On The Ninth Degree of AMORC With Additional Commentarycharly charly50% (2)

- ODEROI Adolescent Study Fact Sheet: Indian OceanDocument9 pagesODEROI Adolescent Study Fact Sheet: Indian OceanHayZara MadagascarNo ratings yet

- Revised E-Tickets With Seat NumberDocument1 pageRevised E-Tickets With Seat NumberMohiminul KhanNo ratings yet

- Chapter - 4 Income of Other Persons Included in Assessees Total IncomeDocument34 pagesChapter - 4 Income of Other Persons Included in Assessees Total IncomeAnanthvasanthaNo ratings yet

- Week 13 15Document14 pagesWeek 13 15Marjorie QuitorNo ratings yet

- Frankie and Johnny: Moderate SwingDocument1 pageFrankie and Johnny: Moderate SwingGEORGESNo ratings yet

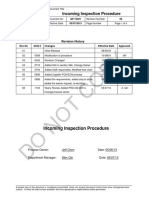

- QP 74301 Rev 08 Incoming Inspection ProcedureDocument9 pagesQP 74301 Rev 08 Incoming Inspection ProcedureAngeline D'AlmaidaNo ratings yet

- Building Interview SkillsDocument3 pagesBuilding Interview Skillscomedesroseann108No ratings yet

- Gregorio Araneta Vs RodasDocument2 pagesGregorio Araneta Vs RodasLeomar Despi LadongaNo ratings yet

- XXXDocument2 pagesXXXtony alvaNo ratings yet

- MOL Pakistan - CORA DirectorateDocument18 pagesMOL Pakistan - CORA DirectorateAsad IrfanNo ratings yet

- QATAR: Major ChangesDocument11 pagesQATAR: Major ChangesVivekanandNo ratings yet

- Allan Symes CV 1Document3 pagesAllan Symes CV 1api-368993634No ratings yet

- Files Example Darty PDFDocument12 pagesFiles Example Darty PDFMalick DiattaNo ratings yet

- Trabajo Colaborativo Ingles IIDocument8 pagesTrabajo Colaborativo Ingles IIVivianaGaitanNo ratings yet

- JASS AR FY2022 - FinalDocument63 pagesJASS AR FY2022 - FinalJo ClioNo ratings yet

- Maguayo: Maguayo Is A Barrio in The Municipality of Dorado, PuertoDocument4 pagesMaguayo: Maguayo Is A Barrio in The Municipality of Dorado, PuertoChristopher ServantNo ratings yet

- EnglishFile4e Upp-Int TG PCM Vocab 3ADocument1 pageEnglishFile4e Upp-Int TG PCM Vocab 3AღDaff ღNo ratings yet

- M W Patterson - The Church of EnglandDocument464 pagesM W Patterson - The Church of Englandds1112225198No ratings yet

- A Summary Critique - The Works of M. Scott Peck by Howard PepperDocument4 pagesA Summary Critique - The Works of M. Scott Peck by Howard PepperthunderdomeNo ratings yet

- Jimeno ArthurDocument69 pagesJimeno ArthurOdessa DysangcoNo ratings yet

- Brigada Eskwela Certificates 2022Document23 pagesBrigada Eskwela Certificates 2022RITCHEL DAGUPANNo ratings yet

- OSRL UNDP Webinar On Oil Spill Mitigation and Management NTTDocument13 pagesOSRL UNDP Webinar On Oil Spill Mitigation and Management NTTBUMI ManilapaiNo ratings yet

- Barangay San Jose Demographics and CoordinatesDocument2 pagesBarangay San Jose Demographics and CoordinatesEmmanuel AzuelaNo ratings yet

- Barangay of Comagaycay: Republic of The Philippines Province of Catanduanes Municipality of San AndresDocument5 pagesBarangay of Comagaycay: Republic of The Philippines Province of Catanduanes Municipality of San AndresEllarence RafaelNo ratings yet

- Now Platform™: Single Data Model Multi-InstanceDocument3 pagesNow Platform™: Single Data Model Multi-InstanceMarcusViníciusNo ratings yet

- Topic: Summary:: Discussion Relevant To TopicDocument3 pagesTopic: Summary:: Discussion Relevant To TopicAmber AncaNo ratings yet

Straubhaar Et Al 2013 - Inequity in The Technopolis Ch4

Straubhaar Et Al 2013 - Inequity in The Technopolis Ch4

Uploaded by

cowja0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

26 views12 pagestexas

austin

digital divide

Original Title

Straubhaar Et Al 2013 - Inequity in the Technopolis Ch4

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

PDF or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this Documenttexas

austin

digital divide

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF or read online from Scribd

Download as pdf

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

26 views12 pagesStraubhaar Et Al 2013 - Inequity in The Technopolis Ch4

Straubhaar Et Al 2013 - Inequity in The Technopolis Ch4

Uploaded by

cowjatexas

austin

digital divide

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF or read online from Scribd

Download as pdf

You are on page 1of 12

ZEYNEP TUPEKCI

CHAPTER 4

PAST AND FUTURE DIVIDES.

SOCIAL MOBILITY,

INEQUALITY, AND THE

DIGITAL DIVIDE IN AUSTIN

DURING THE TECH BOOM

This caer examines te ecnomie con

sequences of the technopolis development strategy adopted by Aus-

‘in, Texas. It concentrates on inequality, the digital divide, and labor

market outcomes for low-income people, with a focus on the tech

‘boom of the late 19908 and early 2000s in Austin, often considered

4 paradigmatic example of the “new economy” high-tech metropolis

and of the (successful) deliberate reinvention of a city. In particular, [

will examine the theoretical assuraptions that structure the technop.

olis strategy and proposed remedies to negative economic outcomes

caused by the digital divide such s job training, and how these play

out within the context of a self-proclaimed technopolis.

Job training in fields such as in‘ormation technology is a standard

policy prescription for low-income workers, especially during eco-

nomic downturns [including the current Great Recession that be

gan in 2008], which makes the Austin example particularly relevant.

However, actual labor-market outcomes for population segments that

increase their computer skills have received less attention in schol-

arly work on the digital divide. The digital divide rubric often con-

fates two topics: individual outcomes resulting from lack of access

to or competence with using the internet, on the one hand, and the

overall changes to the structure of the labor market caused by the in-

creasing prevalence of information technologies, on the other hand.

While those two aspects of the divide overlap, they are not identical;

a conceptual and analytic distinction must be maintained.

In this chapter, I start by briefly reviewing theories about the

Iabor-market consequences of information technology. Concerns

46

Tees

about the workforce effects of computers precede the digital divide

discourse, which emerged only in the 19908. Within the digital divide

framework, there are two interrelated issues concerning labor-market

outcomes and information technology. The first concerns the over-

all effect of increasingly powerful information technologies on the

structure of the labor marke. Which kinds of occupations are grow-

ing, and which are shrinking? How does new technology alter power

relations between employer and employees? Which occupations gain

in prestige and pay, and which lose? What can a locality do to cre-

ate a better environment for its residents? A commonly proposed an-

swer to these problems has teen the technopolis strategy, examined

at Jength in Chapter 3 of this book.

‘The second major issue concerns feasible strategies for generat-

ing upward mobility, or in some cases strategies for stopping or sta-

bilizing downward mobility, for those segments of the labor market

that are either already disadvantaged or threatened by technological

changes. The commonly proposed remedy is job training. However,

the two issues are clearly intertwined: the success of individual strat-

egies will obviously depend on the opportunity structures in the la-

bor market.

INFORMATION TECHNOLOGIES AND LAROR MARKETS:

COMPETING THEORIES, NARROW PUBLIC DIALOGUE

While there is significant debate within the academic commu-

nity about these topics, muct: of the civic discourse on the economic

aspects of information technology policy subscribes implicitly to a

viewpoint generally associated with social theorists such as Daniel

Bell (1973) or Manuel Castel’s (1996). While not identical, and gen-

erally much more nuanced than their public articulations, these

theories essentially propose an economy in which information-

technology-related skills are rewarded well and provide social mobil.

ity, increased job opportunities, and economic benefit to their hold-

ers, This view is often associated with terms such as “information

age,” “knowledge economy," and “postindustrial society.”

In particular, Bell's theory of postindustrial society makes specific

predictions about the relationship between work, skill, and reward,

following from the key premise that information and the tools for ac-

cessing and manipulating information form the critical resource for,

and thus the main path to, social mobility (Giddens 1981, 21; Lyon

Past and Futute Divides

1988, 2-5) Webster and Robins 1986 32-48). Postindustrial society

‘theorists all claim to some degree thet we have witnessed an epochal

shift from industrial society, where the critical resource was capi-

tal, to postindustrial society, where the critical resource is technical

competence and education.

Bell (1973) underlines three major characteristics (or predictions}

of the new information society: 1) a shift in emphasis from manufac-

turing and material production to a service-oriented economy, (2) the

importance of information as a commodity, and (3) an increase in

the proportion of the workforce engaged in. “knowledge wark.” Such

changes, Bell contends, will fundamentally change the structure of

work and the power relations at work, increasing the power of the

skilled knowledge worker and thus expanding the base of meritoc:

racy, since social mobility will no longer be limited by access to capi-

tal, the critical resource of the industrial society:

‘The postindustrial society adds a new criterion to the definitions

of base and access, Technical skill becomes a condition of opera

tive power, and higher education means the obtaining of technical

skill, As a result, there has been a shift in the slope of power as,

in key institutions, technical competence becomes the overriding

consideration. ... The postindustrial society, in this dimension

of status and power, is the logical extension of the meritocracy; it

is the codification of new social order based, in principle, on the

priority of educated talent. (1973, 426)

Here, Bell joins together multiple assumptions that can be ana-

lytically separated. The importance of information as a commodity

could increase without necessarily :ncreasing the number of highly

‘paid, skilled jobs. Polarization theory, discussed below, proposes such

‘a scenario, Also, educated talent could be valued without capital be-

‘coming less important by comparison. On the contrary, in some set-

tings, the importance of capital covld increase at a faster rate since

‘most educated labor requires extensive capital layout to practice.

‘What good are advanced biotechnology skills without a correspond.

ing expensive laboratory?

Following from the Bell-Castells tradition, the “skill-biased tech:

nological change” school of thought argues that new technologies re-

quire up-skilling from the workforce, and that those who do not fare

‘well in the new economy are those who suffer from lack of educa

PY rafkes

tion and appropriate high-level skills, The most common data point

offered as proof of this theory is the strong positive return on edu:

cation; on the average, a person with a college degree earns much

more than a high school graiuate, while a person with an advanced

degree cars more than someone with only a college degree [Autor

et al. 1997). (PRD holders, however, average less than holders of MAs,

MBAs, or other professional graduate degrees.) The reasoning for why

higher-educated people are puid more is usually that there is a short

age of them. This explanation is commonly cited by policy makers

at all levels~including presidents, For example, President Clinton

noted in his State of the Union address in 2000 that “today's income

‘sap is largely a skills gap” Clinton 2000). Such rhetoric has been

‘echoed by both George W. Bush and Barack Obama, whose adminis-

tration launched a major effort to promote job training in response to

the “Great Recession.”

Indeed, while average wages have been mostly stagnant since the

19708, low-skilled workers have experienced a wage collapse, whereas

higherskilled workers have fared less badly. The disparity between

the fates of differently educsted segments of the labor market, cou:

pled with the ubiquity of iniormation technology in the workplace,

guided many to what seemed like an obvious conclusion: we are mov-

ing toward an economy in waich skills are rewarded, and those that,

are lefe behind could get ahead if they acquired the right skills.

However, the Bell-Castells model also incorporates several leaps

in logic, First it assumes that working with high technology is uni-

formly a high-skilled endeavor, In fact, many advances in technology

have been made with the explicit goal of lowering skill requirements

(Noble 1984; Zuboff 1988), Thus, by itself, the prevalence of comput-

ers in the workplace does not warrant the assumption that the jobs

associated with them have been up-skilled.

Second, many activities related to technology, such as assembling

computers, are themselves low-skill jobs. A sector can thus be classi-

fied as high tech even though its occupational effects on the economy

are mostly confined to the .ow-skilled, low-paid sector. This con

founding of sector and occupational structure bedevils much of the

public discourse on the topic.

‘Third, there are data clearly in conflict with the received wisdom

about developed countries in general, and the United States in partic-

ular, becoming a predominantly high-skilled economy. In most in-

dustrialized nations, the majority of the population is now employed

8

ost and Future Divides

in what is termed the “service” industrya relatively misleading cat-

‘egory that lumps together low-wage corporate positions and McJobs

with high-paid, high-skilled professions like doctor and lawyer. Dis-

aggregating the service sector into occupational categories reveals 2

more exact and sobering conclusion: most service sector jobs are low

paid and low skilled. More precisely, these countries have seen the

replacement of high-paid, often unionized jobs in capital-intensive

‘manufacturing industries with low-peid jobs, many of which involve

providing services rather than producing goods.

By contrast, polarization theorists have argued that information

technology may have negative effects on the lower segments of labor

markets, either in part or as a whole, even while requiring up-skilling

for some segments. Polarization theory, or labor-market-segmentation

theory, makes the case that, as a result of advances in technology,

jobs requiring medium-level skills ate reduced in number or elimi-

nated, with the majority of employees reallocated to low-skilled jobs,

while at the same time a relatively small number of new ond higher-

skilled planning and monitoring jobs is created |Kubicek 1985, 76}.

Polarization theory dovetails with the work of theorists who have

‘suggested that computers can be useé for significantly different pur-

poses at the upper and lower levels of the occupational structure; in

the large low-paid, low-skilled job sector, information technology is

used to automate, deskill, and control (Braverman 1975} rather than

to enhance and "informate” (Zuboff x988]. In fact, a 2006 paper (AU:

tor, Katz, and Kearney] finds that the nature of the existing economic

polarization, as well as increases thereof, corresponds closely with

differential application of computers in higher and lower segments of

the labor market.

In his book The Work of Nations, published in 1991, Robert Reich

‘sums up the polarization approach to analyzing the structure of work

in an information society and predic:s roughly the occupational re-

sults depicted above

All Americans used to be in the same economic boat. Most rose or

fell together, as the corporations in which they were employed, the

industries comprising such corporations, and the national econ-

‘omy as a whole became more productive—or languished. But na

tional borders no longer define our economic fates, We are now in

different boats, one sinking rapidly, cne sinking more slowly, and

the third rising steadily. (Reich 1991, 208)

You might also like

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5820)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1093)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (852)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (590)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (898)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (540)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (349)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (822)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (122)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (403)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- Cottom - The Hustle Economy - Dissent MagazineDocument6 pagesCottom - The Hustle Economy - Dissent MagazinecowjaNo ratings yet

- Twitter's Doubling of Character Count From 140 To 280 Had Little Impact On Length of Tweets - TechCrunchDocument2 pagesTwitter's Doubling of Character Count From 140 To 280 Had Little Impact On Length of Tweets - TechCrunchcowjaNo ratings yet

- Dril Is Everyone. More Specifically, He's A Guy Named Paul. - The RingerDocument20 pagesDril Is Everyone. More Specifically, He's A Guy Named Paul. - The RingercowjaNo ratings yet

- New Associated Press Guidelines - Keep It Brief - The Washington PostDocument2 pagesNew Associated Press Guidelines - Keep It Brief - The Washington PostcowjaNo ratings yet

- Ross - The Record Effect - The New YorkerDocument18 pagesRoss - The Record Effect - The New YorkercowjaNo ratings yet

- Christgau - Living Without The BeatlesDocument10 pagesChristgau - Living Without The BeatlescowjaNo ratings yet

- Berthoff - Learning The Uses of ChaosDocument3 pagesBerthoff - Learning The Uses of ChaoscowjaNo ratings yet

- Robert Christgau - Rock Lyrics Are Poetry (Maybe)Document6 pagesRobert Christgau - Rock Lyrics Are Poetry (Maybe)cowjaNo ratings yet

- Neofeudalism - The End of Capitalism - Los Angeles Review of BooksDocument22 pagesNeofeudalism - The End of Capitalism - Los Angeles Review of Bookscowja100% (1)

- Eno - Axis ThinkingDocument6 pagesEno - Axis ThinkingcowjaNo ratings yet

- Fulton Babicke - Impediments To Productive Argument Rhetorical DecayDocument18 pagesFulton Babicke - Impediments To Productive Argument Rhetorical DecaycowjaNo ratings yet

- Badiou - Lacan and The Pre-SocraticsDocument4 pagesBadiou - Lacan and The Pre-SocraticscowjaNo ratings yet

- DiCaglio - Language and The Logic of Subjectivity - Whitehead and Burke in CrisisDocument24 pagesDiCaglio - Language and The Logic of Subjectivity - Whitehead and Burke in CrisiscowjaNo ratings yet

- Kinsella - Critiques of Reflective PracticeDocument4 pagesKinsella - Critiques of Reflective PracticecowjaNo ratings yet

- Aoki - Letters From Lacan Reading and The MathemeDocument310 pagesAoki - Letters From Lacan Reading and The MathemecowjaNo ratings yet

- The Declaration of Independence - The Mystery of The Lost OriginalDocument31 pagesThe Declaration of Independence - The Mystery of The Lost OriginalcowjaNo ratings yet

- CTA Case No. 10063Document16 pagesCTA Case No. 10063Karen Joy JavierNo ratings yet

- Webb vs. de LeonDocument22 pagesWebb vs. de LeonIyaNo ratings yet

- Employment Application: State of Utah Department of Workforce ServicesDocument3 pagesEmployment Application: State of Utah Department of Workforce Servicesapi-283418026No ratings yet

- Notes On The Ninth Degree of AMORC With Additional CommentaryDocument17 pagesNotes On The Ninth Degree of AMORC With Additional Commentarycharly charly50% (2)

- ODEROI Adolescent Study Fact Sheet: Indian OceanDocument9 pagesODEROI Adolescent Study Fact Sheet: Indian OceanHayZara MadagascarNo ratings yet

- Revised E-Tickets With Seat NumberDocument1 pageRevised E-Tickets With Seat NumberMohiminul KhanNo ratings yet

- Chapter - 4 Income of Other Persons Included in Assessees Total IncomeDocument34 pagesChapter - 4 Income of Other Persons Included in Assessees Total IncomeAnanthvasanthaNo ratings yet

- Week 13 15Document14 pagesWeek 13 15Marjorie QuitorNo ratings yet

- Frankie and Johnny: Moderate SwingDocument1 pageFrankie and Johnny: Moderate SwingGEORGESNo ratings yet

- QP 74301 Rev 08 Incoming Inspection ProcedureDocument9 pagesQP 74301 Rev 08 Incoming Inspection ProcedureAngeline D'AlmaidaNo ratings yet

- Building Interview SkillsDocument3 pagesBuilding Interview Skillscomedesroseann108No ratings yet

- Gregorio Araneta Vs RodasDocument2 pagesGregorio Araneta Vs RodasLeomar Despi LadongaNo ratings yet

- XXXDocument2 pagesXXXtony alvaNo ratings yet

- MOL Pakistan - CORA DirectorateDocument18 pagesMOL Pakistan - CORA DirectorateAsad IrfanNo ratings yet

- QATAR: Major ChangesDocument11 pagesQATAR: Major ChangesVivekanandNo ratings yet

- Allan Symes CV 1Document3 pagesAllan Symes CV 1api-368993634No ratings yet

- Files Example Darty PDFDocument12 pagesFiles Example Darty PDFMalick DiattaNo ratings yet

- Trabajo Colaborativo Ingles IIDocument8 pagesTrabajo Colaborativo Ingles IIVivianaGaitanNo ratings yet

- JASS AR FY2022 - FinalDocument63 pagesJASS AR FY2022 - FinalJo ClioNo ratings yet

- Maguayo: Maguayo Is A Barrio in The Municipality of Dorado, PuertoDocument4 pagesMaguayo: Maguayo Is A Barrio in The Municipality of Dorado, PuertoChristopher ServantNo ratings yet

- EnglishFile4e Upp-Int TG PCM Vocab 3ADocument1 pageEnglishFile4e Upp-Int TG PCM Vocab 3AღDaff ღNo ratings yet

- M W Patterson - The Church of EnglandDocument464 pagesM W Patterson - The Church of Englandds1112225198No ratings yet

- A Summary Critique - The Works of M. Scott Peck by Howard PepperDocument4 pagesA Summary Critique - The Works of M. Scott Peck by Howard PepperthunderdomeNo ratings yet

- Jimeno ArthurDocument69 pagesJimeno ArthurOdessa DysangcoNo ratings yet

- Brigada Eskwela Certificates 2022Document23 pagesBrigada Eskwela Certificates 2022RITCHEL DAGUPANNo ratings yet

- OSRL UNDP Webinar On Oil Spill Mitigation and Management NTTDocument13 pagesOSRL UNDP Webinar On Oil Spill Mitigation and Management NTTBUMI ManilapaiNo ratings yet

- Barangay San Jose Demographics and CoordinatesDocument2 pagesBarangay San Jose Demographics and CoordinatesEmmanuel AzuelaNo ratings yet

- Barangay of Comagaycay: Republic of The Philippines Province of Catanduanes Municipality of San AndresDocument5 pagesBarangay of Comagaycay: Republic of The Philippines Province of Catanduanes Municipality of San AndresEllarence RafaelNo ratings yet

- Now Platform™: Single Data Model Multi-InstanceDocument3 pagesNow Platform™: Single Data Model Multi-InstanceMarcusViníciusNo ratings yet

- Topic: Summary:: Discussion Relevant To TopicDocument3 pagesTopic: Summary:: Discussion Relevant To TopicAmber AncaNo ratings yet