Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Metaanalysis Donation Organ

Metaanalysis Donation Organ

Uploaded by

miallyannaCopyright:

Available Formats

You might also like

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5822)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1093)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (852)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (590)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (898)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (540)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (349)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (822)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (122)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (403)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- Chapter 10 Neuropsychological Assessment and ScreeningDocument26 pagesChapter 10 Neuropsychological Assessment and ScreeningKadir Say'sNo ratings yet

- Care of The Hospitalized Patient With Acute Exacerbation of CopdDocument25 pagesCare of The Hospitalized Patient With Acute Exacerbation of CopdmiallyannaNo ratings yet

- Disruption of Nerves Coordinating Bowel Peristalsis Lab FindingsDocument1 pageDisruption of Nerves Coordinating Bowel Peristalsis Lab FindingsmiallyannaNo ratings yet

- Lead Poisoning and Recurrent Abdominal Pain: Case ReportDocument3 pagesLead Poisoning and Recurrent Abdominal Pain: Case ReportmiallyannaNo ratings yet

- Using Wellbeing For Public Policy: Theory, Measurement, and RecommendationsDocument35 pagesUsing Wellbeing For Public Policy: Theory, Measurement, and RecommendationsmiallyannaNo ratings yet

- Game of Thrones (Literary Committee) : Specialized Committees - 2014EDocument21 pagesGame of Thrones (Literary Committee) : Specialized Committees - 2014EmiallyannaNo ratings yet

- Help-Seeking BehaviorDocument6 pagesHelp-Seeking BehaviormiallyannaNo ratings yet

- Dot Grid PrintableDocument1 pageDot Grid PrintablemiallyannaNo ratings yet

- True Labor vs. False LaborDocument2 pagesTrue Labor vs. False LabormiallyannaNo ratings yet

- Descriptive and Analytical Study Designs: PH 146 - Epidemiology - B.S. Public Health, UP ManilaDocument5 pagesDescriptive and Analytical Study Designs: PH 146 - Epidemiology - B.S. Public Health, UP ManilamiallyannaNo ratings yet

- Carbohydrate MetabolismDocument15 pagesCarbohydrate Metabolismmiallyanna100% (2)

- C1 Atlas C2 Axis C3 - C6 Typical Cervical Vertebra C7 Vertebra ProminensDocument4 pagesC1 Atlas C2 Axis C3 - C6 Typical Cervical Vertebra C7 Vertebra ProminensmiallyannaNo ratings yet

- Musculoskeletal AgeingDocument82 pagesMusculoskeletal Ageingmiallyanna100% (1)

- Why The Bear Has Short TailDocument1 pageWhy The Bear Has Short TailmiallyannaNo ratings yet

- Group3 PH131 TheMusculoskeletalSystemandAging FWRDocument15 pagesGroup3 PH131 TheMusculoskeletalSystemandAging FWRmiallyannaNo ratings yet

- Glandular EpitheliumDocument13 pagesGlandular EpitheliummiallyannaNo ratings yet

- Gra-GO™: Rafaelo Paolo A. Fernandez Grade 7 - Valdocco General Technology Tr. MiggyDocument2 pagesGra-GO™: Rafaelo Paolo A. Fernandez Grade 7 - Valdocco General Technology Tr. MiggymiallyannaNo ratings yet

- Lipids PDFDocument71 pagesLipids PDFmiallyannaNo ratings yet

- Group 2 LIPIDS Formal Written ReportDocument7 pagesGroup 2 LIPIDS Formal Written ReportmiallyannaNo ratings yet

- Academic WritingDocument14 pagesAcademic WritingJulianne Descalsota LegaspiNo ratings yet

- Aicte Internship Approval Pending 1Document7 pagesAicte Internship Approval Pending 1Anisha KumariNo ratings yet

- Front Pages Front PageDocument9 pagesFront Pages Front PageDeepanshu GoyalNo ratings yet

- AlaviaDocument2 pagesAlaviawareternal1No ratings yet

- Psychogenic Pain 1Document23 pagesPsychogenic Pain 1Agatha Billkiss IsmailNo ratings yet

- Constitutional Law AssignmentDocument26 pagesConstitutional Law AssignmentSakshiNo ratings yet

- Private Schools BacoorDocument15 pagesPrivate Schools BacoorWarren Joseph MoisesNo ratings yet

- Peer Pressure Research 1Document30 pagesPeer Pressure Research 1Ezequiel GonzalezNo ratings yet

- PC Hardware Servicing CBCDocument61 pagesPC Hardware Servicing CBCamirvillas100% (1)

- Schools of PhilosophyDocument81 pagesSchools of PhilosophyMike Perez100% (4)

- TMDI Lesson Plan 1Document3 pagesTMDI Lesson Plan 1Diane VillNo ratings yet

- Notes On Time ManagementDocument10 pagesNotes On Time ManagementAldrinmarkquintanaNo ratings yet

- Observations Report StudentDocument12 pagesObservations Report StudentngonzalezkNo ratings yet

- Qulaitative and Quantitative MethodsDocument9 pagesQulaitative and Quantitative MethodskamalNo ratings yet

- Business Mathematics (OBE)Document10 pagesBusiness Mathematics (OBE)irene apiladaNo ratings yet

- SCHEME OF WORK TemplateDocument4 pagesSCHEME OF WORK TemplateIulian RaduNo ratings yet

- Icdl FaqsDocument10 pagesIcdl FaqsmariamdesktopNo ratings yet

- Ted 2011 Wa Less Stuff More Happiness Graham Hill 6 MinDocument3 pagesTed 2011 Wa Less Stuff More Happiness Graham Hill 6 MinPeetaceNo ratings yet

- Water Cycle Lesson Plan-1Document2 pagesWater Cycle Lesson Plan-1api-247375227100% (1)

- Subject: General Chemistry Test,: Date: May 2015Document7 pagesSubject: General Chemistry Test,: Date: May 2015PHƯƠNG ĐẶNG YẾNNo ratings yet

- Michelle D. Kelly RN, FNP, DNP (C) EducationDocument5 pagesMichelle D. Kelly RN, FNP, DNP (C) EducationMiserable*No ratings yet

- Stress in College Students Research PaperDocument6 pagesStress in College Students Research Paperttdqgsbnd100% (1)

- Test Result ConsolidationDocument4 pagesTest Result ConsolidationDONA FE SIADENNo ratings yet

- B1 UNIT 1 Everyday English Teacher's NotesDocument1 pageB1 UNIT 1 Everyday English Teacher's NotesXime OlariagaNo ratings yet

- Portfolio Guidelines For Unit 7 1: First Day of Class November 29 - Last Day of Class December 23Document7 pagesPortfolio Guidelines For Unit 7 1: First Day of Class November 29 - Last Day of Class December 23Edith BaosNo ratings yet

- FTS - Westville Prisons ApproachDocument1 pageFTS - Westville Prisons ApproachFeeding_the_SelfNo ratings yet

- ID 333 VDA 6.3 Upgrade Training ProgramDocument2 pagesID 333 VDA 6.3 Upgrade Training ProgramfauzanNo ratings yet

- Our Town Thesis StatementDocument7 pagesOur Town Thesis Statementlisarileymilwaukee100% (2)

- Office of The Senior High School Awards Committee: Application Form For Leadership Excellence AwardDocument2 pagesOffice of The Senior High School Awards Committee: Application Form For Leadership Excellence AwardDindo Arambala OjedaNo ratings yet

Metaanalysis Donation Organ

Metaanalysis Donation Organ

Uploaded by

miallyannaCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Metaanalysis Donation Organ

Metaanalysis Donation Organ

Uploaded by

miallyannaCopyright:

Available Formats

Original Clinical ScienceçGeneral

Community-Based Interventions and Individuals'

Willingness to be a Deceased Organ Donor:

Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis

Andrew T. Li,1,2,3 Germaine Wong,2,3,4 Michelle Irving,2,3 Stephen Jan,5 Allison Tong,2,3 Angelique F. Ralph,2,3

and Kirsten Howard2,6

Background. Widespread in-principle community support for organ donation does not necessarily translate to individuals be-

coming organ donors after death. Previous studies have identified factors that influence individuals' decisions to become organ

donors, which may be effectively targeted by interventions. We aimed to describe and evaluate the effectiveness of community-

based interventions to increase the willingness of individuals to be a deceased organ donor. Methods. We systematically reviewed

all randomized controlled trials (RCTs), non-RCTs (NRCTs), and before-after studies that assessed the impact of interventions on

increasing the willingness to be a deceased organ donor (measured as commitment to donate and/or intention to donate). We

searched MEDLINE, Embase, PsycINFO, and CINAHL, without language restriction, to December 2013 and the reference lists

of the included articles. We conducted a risk of bias assessment using the Cochrane risk of bias tools and assessed confidence

in the evidence using the Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development, and Evaluation framework. Results. We

identified 63 studies (11 RCTs, 8 cluster-RCTs, 4 NRCTs, 8 cluster-NRCTs, 27 before-after studies) with over 170000 participants.

Overall, the quality of the evidence was low. Participants who received a broad range of community-based interventions were more

likely to commit as donors (7 cluster-RCTs; 6015 participants; relative risk, 1.70; 95% confidence interval [95% CI], 1.22-2.36;

I2 = 94%, P = 0.002), and had higher levels of willingness to donate (3 RCTs, 393 participants; standardized mean difference,

0.29; 95% CI, 0.01-0.56; I2 = 45%; P = 0.04) than those who did not receive the interventions, but not the intention to donate

(315 participants; relative risk, 1.19; 95% CI, 0.94-1.51; P = 0.14). Conclusions. Community partnerships and active learning

community-based interventions may be effective in increasing the commitment, but not intentions to donate. However, the overall

risk of bias for was high, and this may have led to overestimation of the relative treatment effects of these interventions.

(Transplantation 2015;99: 2634–2643)

F or many patients with end-stage organ failure, transplan-

tation is the only lifesaving treatment option. However,

a critical shortage of donor organs exists worldwide, and

In many countries, strong in-principle support for organ

donation in the community does not always translate into a

personal decision to become an organ donor. 5,6 The factors

in most countries, deceased organ donation rates are inade- that influence such decisions may be multifactorial and in-

quate to address the growing demand for organs. On aver- clude knowledge about organ donation, personal beliefs,

age, more than 1 person in the United Kingdom1 and such as altruism or fear of medical neglect; external influ-

almost 15 people in the United States die each day on the ences, such as family and culture; emotional influences, such

transplant waiting list.2 In Australia, the median waiting time as grief or apathy; and the prevailing institutional and policy

on dialysis for a donor kidney is 3.3 years.3 The rates of de- context, such as the complexity of the consent system.6 These

ceased organ donation vary greatly internationally, from factors may represent potential levers for intervention to in-

36.5 donors per million populations in Croatia to 0.09 do- crease the community's willingness to become a deceased or-

nors per million population in Morocco. 4 gan donor. A considerable variety of approaches have been

taken across and within countries to increase deceased organ

Received 12 February 2015. Revision received 20 May 2015.

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Accepted 3 June 2015.

1

K.H., S.J., M.I., and G.W. designed the study. A.T.L., A.F.R., G.W., and A.T. conducted

Monash School of Medicine, Monash University, Victoria, Australia. the data extraction and analyses. All authors contributed to the interpretation of the

2

Sydney School of Public Health, University of Sydney, New South Wales, Australia. analyses. A.T.L. drafted the article. All authors contributed to the writing and review of

3

Centre for Kidney Research, The Children's Hospital at Westmead, New South the article.

Wales, Australia. Correspondence: Germaine Wong, Centre for Transplant and Renal Research,

4

Centre for Transplant and Renal Research, Westmead Hospital, New South Wales, Westmead Hospital, Cnr Hawkesbury Rd & Darcy Rd, Westmead New South Wales

Australia. 2145, Australia. (germaine.wong@health.nsw.gov.au).

5

The George Institute for Global Health, Camperdown, New South Wales, Australia. Supplemental digital content (SDC) is available for this article. Direct URL citations

6

appear in the printed text, and links to the digital files are provided in the HTML text

The Institute for Choice, University of South Australia, North Sydney, New South of this article on the journal’s Web site (www.transplantjournal.com).

Wales, Australia.

Copyright © 2015 Wolters Kluwer Health, Inc. All rights reserved.

The PAraDOx study is funded by an Australian Research Council Discovery Project

Grant (DP0985187). The funders’ played no role in the research or the decision ISSN: 0041-1337/15/9912-2634

to publish. DOI: 10.1097/TP.0000000000000897

2634 www.transplantjournal.com Transplantation ■ December 2015 ■ Volume 99 ■ Number 12

Copyright © 2015 Wolters Kluwer Health, Inc. All rights reserved.

© 2015 Wolters Kluwer Li et al 2635

donation. The types of interventions for increasing community donor on an organ donor registry, driver's licence, donor

willingness to be a deceased organ donor that have been stud- card, or other official record, and/or communicate to the next

ied are diverse and include mass media campaigns, educa- of kin that one wishes to become an organ donor.

tional materials, and community partnerships, among others.

We aimed to identify and evaluate the totality of evidence re- Risk of Bias

garding the effectiveness of community-based interventions Two authors (A.T.L. and A.F.R.) independently assessed

to increase deceased organ donation. the risk of bias and resolved all discrepancies by consensus

for all included studies. For trials, we used the Cochrane Risk

of Bias Tool, 8 and for before-after studies, we used a modi-

MATERIALS AND METHODS

fied version of the Cochrane Effective Practice and Organi-

We conducted a systematic review based on standard methods sation of Care Group suggested risk of bias criteria for

and reporting in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items interrupted time series studies. 9

for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses statement. 7

Quality of Evidence

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

We assessed the quality of the evidence informing the sum-

We included studies (randomized controlled trials [RCTs],

mary estimates using the Grading of Recommendations As-

non-RCTs [NRCTs], and before-after studies) that quantita-

sessment Development and Evaluation guidelines. 10

tively assessed the impact of interventions to increase the will-

ingness of members of the community to become solid organ Data Synthesis and Statistical Analyses

donors after death. We included studies that used individual We expressed results from individual trials and before-

level assignment (RCTs and NRCTs) and those that used after studies as risk ratios (RR) with 95% confidence inter-

group level assignment (cluster RCTs [CRCTs] and cluster vals (95% CI) for dichotomous outcomes and as standard-

NRCTs). We imposed no restrictions on article language. ized mean differences (SMD) with 95% CI for continuous

We excluded abstracts and non-research articles. outcomes. We obtained the summary estimates of binary out-

Search Strategies comes using the DerSimonian and Laird random effects

We searched MEDLINE, Embase, PsycInfo and CINAHL model. We considered P values ≤0.05 to be statistically sig-

from inception to December 2013. MeSH terms and key- nificant. We quantified heterogeneity using the χ2 test and

words for organ donation, interventions, and comparative I2 statistic and used preplanned subgroup analyses by inter-

studies (eg, “RCT”) were used. The search strategies are pro- vention types and target populations, and retrospective sub-

vided in Appendix 1, SDC, http://links.lww.com/TP/B187. group analyses by geographic location of studies and study

quality, to explore the possible sources of heterogeneity.

Data Extraction Where possible, we undertook a sensitivity analysis based

Two authors (A.T.L. and M.J.I.) independently assessed all on the quality of the studies and assessed publication bias

titles and abstracts for eligible studies and discarded those using funnel plots. We conducted all analyses using Review

that did not meet the inclusion criteria. We extracted data Manager 5. Where appropriate, we also calculated the num-

on study design, geographic location, setting, sample size, ber needed to treat from the population attributable risk

participants, interventions and comparators, and the rates (PAR) using the following formula, where Pe represents the

of commitment to donate and intention to donate. Where total proportion of participants who were exposed to the in-

outcome data were reported in a form that could not be terventions, and RRe represents the relative risks (RRs) given

meta-analyzed, we contacted corresponding authors to seek by the meta-analyses:

the relevant data including the number of events and group

sample sizes for the dichotomous outcomes, and the mean es- 1 1 1 þ Pe ðRRe ‐1Þ

NNT ¼ ¼ ¼

timates, standard deviations, and group sample sizes for the PAR Pe ðRRe ‐1Þ Pe ðRRe ‐1Þ

1þPe ðRRe ‐1Þ

continuous outcome.

Outcomes Measures RESULTS

The 2 prespecified outcomes that we assessed were com- Characteristics of Studies

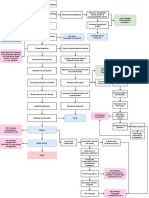

mitment to donate and intention to donate. We defined com- We included 49 articles, incorporating a total of 63 stud-

mitment to donate as documentation of being a donor on an ies as some articles reported findings on multiple studies

organ donor registry, driver's licence, donor card, or other (Figure 1). All articles were from primary sources. The study

official record, communication to the next of kin that one characteristics are summarized in Table 1. Five studies did

wishes to become an organ donor and/or otherwise self- not report their sample size. The remaining 58 studies in-

reporting that one is an organ donor. volved 174,279 participants. Thirty-one studies were trials

Intention to donate could be reported as a dichotomous (8 RCTs, 11 CRCTs, 4 NRCTs, 8 cluster NRCTs) and 32

outcome (“positive intent to donate”) or a continuous out- were before-after studies. In total, 42 of 63 studies (67%)

come (“willingness to donate”). We defined positive intent were included in the meta-analyses. The majority of the stud-

to donate as any action or statement that indicates one is will- ies originated from the United States, and with an average

ing to be an organ donor, document being a donor on an follow-up time of 60.5 days (Table 1).

organ donor registry, driver's licence, donor card, or other of-

ficial record, and/or communicate to the next of kin that they Risk of Bias

wish to become an organ donor, but without committing to Appendix 2 (SDC, http://links.lww.com/TP/B187) shows

donation. We defined willingness to donate as self-assessed the risk of bias assessments for all included studies. Of the

willingness to become an organ donor, document being a 31 trials, 11 (35%) were judged as high risk of bias, 18 trials

Copyright © 2015 Wolters Kluwer Health, Inc. All rights reserved.

2636 Transplantation ■ December 2015 ■ Volume 99 ■ Number 12 www.transplantjournal.com

FIGURE 1. Process of studies selection.

as unclear risk of bias (58%), and 2 trials (6%) as low risk of controlled trials or before-after studies, for which the risk of bias

bias. No trials blinded participants or personnel to the inter- varied between unclear and high. The consistency of the esti-

ventions. Sixteen trials (52%) had high risk of reporting bias. mates of the effects was also variable, with heterogeneity

Allocation concealment was adequate in 9 trials (29%). The ranging from low to high. Publication bias was present.

methods of randomization were adequate in 7 trials (23%), Hence, the overall quality of the evidence was low, indicating

unclear in 14 trials (45%), and inadequate in 10 trials (32%). the confidence we placed in the effect estimates was limited,

Overall, 8 of the 32 before-after studies (25%) were con- and the true estimates were likely to be different from the es-

sidered as high risk of bias, 23 studies as unclear risk of bias timate of effects.10

(72%), and a single study as low risk of bias (3%).

Types of Interventions

Visual assessment of funnel plots (not shown) showed that

the studies were distributed asymmetrically around the com- The included studies examined a diverse range of interven-

bined effect size, suggesting publication bias (Table 2). tions (n = 12). Education was a key strategy in the majority

of interventions, conveying factual, and/or emotive messages

Quality of Evidence relating to the need for organs and/or the process of organ

Table 3 summarizes the quality of evidence for the key find- donation. These interventions included advertising, active learn-

ings of our review. The findings were based on randomised ing, community partnerships, a computer-tailored intervention,

Copyright © 2015 Wolters Kluwer Health, Inc. All rights reserved.

© 2015 Wolters Kluwer Li et al 2637

TABLE 1. to lead discussion on organ donation within their church

Characteristics of included studies members. The computer-tailored intervention (n = 1, 2%)

used a computer program that asked participants questions

Characteristic No. Studies (%) relating to donation and provided feedback based on their in-

Geographic location put. Educational materials (n = 9, 14%) included written ma-

United States of America 46 (73.02) terials such as brochures, videos, and websites that promoted

Netherlands 4 (6.35) organ donation. Interventions at DMV offices (n = 4, 6%)

Germany 3 (4.76) encompassed a range of educational interventions conducted

Turkey 3 (4.76) at DMVs (or equivalent government agency) offices to en-

United Kingdom 3 (4.76) courage customers to commit as deceased organ donors at

Colombia 1 (1.59) these locations where their decisions can be recorded. Promo-

Croatia 1 (1.59) tional materials and staff training to improve communication

South Africa 1 (1.59) with the public about organ donation were a few examples of

Sweden 1 (1.59) such interventions. Workplace interventions (n = 3, 5%) in-

Year of publication cluded educational interventions conducted in the workplace

≤2000 2 (3.2) setting. Some methods had multiple main components (n = 6,

2001-2005 10 (15.9) 10%), for example, utilization of passive learning combined

2006-2010 32 (50.8) with opportunistic registration procedures. Other nonspecific

≥2011 19 (30.2) interventions did not disseminate facts or arguments in favor

Study design of donation. This category encompassed anticipated regret,

RCT 8 (12.7) (n = 3, 5%) in which participants were asked to consider their

CRCT 11 (17.5) regret if they were to not register as organ donors, and opportu-

NRCT 4 (6.3) nistic registration procedures, (n = 2, 3%), whereby the partici-

CNRCT 8 (12.7) pants were given an opportunity to register immediately.

Before-after study 32 (50.8) The specific interventions used in each included study are sum-

Sample size marized in Appendix 3, SDC, http://links.lww.com/TP/B187.

0-500 38 (60.3)

500-1000 4 (6.3) Efficacy of Interventions

1000-10,000 15 (23.8)

Randomized Controlled Trials

>10,000 1 (1.6)

Not stated 5 (7.9) The types of interventions assessed in the meta-analyses in-

Setting 26 (41.3) cluded anticipated regret (n = 2) and educational materials

General community (n = 1). Participants who received community-based inter-

Schools 11 (17.5) ventions experienced a statistically significant improvement

Universities 12 (19.0) in the willingness to donate compared to those that did not

Churches 3 (4.8) receive the interventions (3 studies, 393 participants: SMD,

Primary care 2 (3.2) 0.29; 95% CI, 0.01-0.56; I2 = 45%; P = 0.04) (Figure 2A).

Motor registry 4 (6.3) Participants who received a personalized letter from the Ohio

Military 1 (1.6) Secretary of State (89413 participants: RR, 1.90; 95% CI,

Workplaces 3 (4.8) 1.78-2.02; P < 0.001) and those who received a personalized

Online 1 (1.6) letter and a brochure (89625 participants: RR, 1.91; 95%

Outcomes CI, 1.80-2.03; P < 0.001) experienced a significant improve-

Commitment to donate 36 (57.1) ment in the commitment to donate compared to those who

Intention to donate 34 (54.0) only received a brochure alone. No significant differences

Follow-up time ( mean, SD), d 60.5 (113.3) were observed in the proportion of participants committing

c

to deceased organ donation between those who received a

Nonrandomized controlled trial.

CNRCT indicates cluster non-RCT. personalized letter and a brochure and those who received

a personalized letter only (85790 participants: RR, 1.01;

95% CI, 0.96-1.06; P = 0.73).11 There were also no signifi-

educational materials, education by health professionals, inter- cant differences in the proportion of participants' expressing

ventions at Department of Motor Vehicles (DMV) offices, passive a positive intention to donate between those who received

learning, and workplace interventions. Advertising interventions passive education compared to those that did not (315 partic-

were disseminated through media, such as television, radio, print, ipants: RR, 1.19; 95% CI, 0.94-1.51; P = 0.14).12 Three ad-

billboard, and/or online (n = 5, 8%). The majority of advertising ditional RCTs13–15 assessed the positive intent to donate,

interventions were targeted at ethnic minorities (n = 4, 80%). Ac- but only 2 of these studies reported a significant increase

tive learning (n = 5, 8%) involved participants to complete tasks in the proportion of participants' expressing a positive inten-

that promote and educate organ donation. This contrasted with tion to donate between the intervention and comparator

interventions that involved passive learning (n = 14, 22%), such groups. The types of interventions found to be effective in-

as presentations and school lessons. cluded educational materials on organ donation compared

Community partnerships (n = 9, 14%) involved lay mem- with education materials on avoiding the common cold15

bers from specific communities to promote organ donation, and passive learning combined with a computer-tailored

such as engagement with African-American church leaders intervention.14

Copyright © 2015 Wolters Kluwer Health, Inc. All rights reserved.

2638 Transplantation ■ December 2015 ■ Volume 99 ■ Number 12 www.transplantjournal.com

TABLE 2.

Outcomes of meta-analyses

Outcome Studies Participants P I2 Outcome (summary estimate)

RCTs

Intention to donate (willingness to donate) 3 393 0.04 45% SMD, 0.29 (0.01-0.56)

CRCTs

Commitment to donate 7 6015 0.002 94% RR, 1.70 (1.22-2.36)

NRCTs

Commitment to donate 2 320 0.91 73% RR, 1.05 (0.45-2.45)

Before-after studies

Commitment to donate 15 3709 <0.001 78% RR, 1.51 (1.22-1.86)

Intention to donate (positive intent to donate) 10 9572 0.01 86% RR, 1.14 (1.03-1.26)

Intention to donate (willingness to donate) 5 645 <0.001 76% SMD, 0.54 (0.23-0.86)

Cluster-Randomized Controlled Trials donor cards compared with mass media only.20 Workplace

The types of interventions assessed included in the meta- intervention also resulted in a significant increase in the rate

analyses were community partnership (n = 2), opportunis- of signing donor cards when compared with no intervention.21

tic registration procedures (n = 2), educational materials Workplace intervention comprising of educational materials

(n = 1), intervention at DMVoffices (n = 1), and a workplace and onsite visits by staff was associated with a significant

intervention (n = 1). Participants who received community- increase in self-reported changes in donor status among

based interventions experienced a significant improvement nondonors compared with no intervention (odds ratio, 1.32;

in the commitment to donate compared to those not exposed P < 0.001) When the same intervention was compared with

(7 studies, 6015 participants: RR, 1.70; 95% CI, 1.22-2.36; another intervention comprising only educational materials,

I2 = 94%; P = 0.002) (Figure 2A). a similar result was reported (odds ratio, 1.17; P < 0.03).22

Additionally, a single study that evaluated the effectiveness of

community partnership reported a significant improvement in Before-After Studies

the willingness to donate compared to those that did not receive Twenty-six before-after studies were included in the meta-

the interventions (1043 participants: RR, 0.21; 95% CI, 0.09- analyses. After the interventions were introduced, a signifi-

0.33; P < 0.001).16 Interventions in the form of passive learning cant improvement in the proportion of participants commit-

did not increase the proportion of participants with positive in- ting as donors (15 studies, 3709 participants: RR, 1.51; 95%

tent to donate (187 participants: RR, 1.16; 95% CI, 0.80-1.67; CI, 1.22-1.86; I2 = 78%; P < 0.001), intending to become

P = 0.44). 17 Also, an intervention at DMVoffices was more ef- donors (10 studies, 9572 participants: RR, 1.14; 95% CI,

fective in improving the proportion of participants committed 1.03-1.26, I2 = 86%, P = 0.01,), and in the willingness to do-

to being an organ donor compared with passive display of or- nate (5 studies, 645 participants: SMD, 0.54; 95% CI, 0.23-

gan donation materials. 14 0.86, I2 = 76%, P < 0.001) was observed in the participants

(Figure 2B). The types of interventions assessed for commit-

Non–Randomized Controlled Trials ment to donate included community partnership (n = 6), ac-

tive learning (n = 4), passive learning (n = 3), advertising

Anticipated regret (n = 1) and education by health profes-

(n = 1), and education by health professional (n = 1). The

sional (n = 1) were the 2 major forms of interventions included

types of interventions assessed for positive intent to donate

in the meta-analysis. There were no significant differences in

included advertising (n = 5), passive learning (n = 4), and ed-

the participants' commitment to donate between the inter-

ucational materials (n = 1). The types of interventions

vention and control arms (2 studies, 320 participants: RR,

assessed for willingness to donate included active learning

1.05; 95% CI, 0.45-2.45; I2 = 73%; P = 0.91). Two other

(n = 2), educational materials (n = 1), passive learning (n =1),

studies that examined the benefits of passive learning (17, 18)

and intervention that comprised both passive learning and

did not report a significant increase in the willingness to do-

opportunistic registration procedures (n = 1).

nate and positive intent to donate.

Five other before-after studies examined changes in the

commitment to donate.23–27 Two studies that focused on ed-

Cluster NRCTs ucational materials (n = 1) and passive learning combined

Participants who were shown a videotaped presentation with opportunistic registration procedures (n = 1) reported

containing demographic information about potential organ a significant increase in the proportion of participants agree-

recipients were more likely to take a donor sticker and card ing and committing to being donors compared with baseline

than participants who were shown the same video without results.24,25 Two studies examined changes in the intention to

the demographic information (328 participants: RR, 1.34; donate28,29 and one reported a significant improvement in

95% CI, 1.12-1.61; P = 0.002).18 On the contrary, passive the willingness to donate using educational materials.28

learning with classroom education did not improve the posi-

Subgroup Analyses

tive intent to donate (69 participants: RR, 0.73; 95% CI,

0.40-1.33; P = 0.31).19 A combined intervention of mass me- Types of Intervention

dia and interpersonal approach was associated with a signif- Compared with those not exposed to any form of interven-

icant improvement in the number of participants signing tion, active partnership with the communities was associated

Copyright © 2015 Wolters Kluwer Health, Inc. All rights reserved.

© 2015 Wolters Kluwer

TABLE 3.

Grading of recommendations assessment, development, and evaluation evidence profile of studies for commitment to donate and intention to donate after community-based

interventions

Quality of assessment (decrease in quality score) Summary of findings

Summary outcome Quality of

No. studies (type of study) Risk of bias/quality of eEvidence Consistency Directness Precision Publication Bias (95% CI)* evidence

Community-based interventions (all types)

7 CRCTs All CRCTs; mostly unclear risk of bias (+3) Large inconsistency; I2 = 94% (−2) Direct (0) No serious imprecision Suspected publication bias (−1) Commitment to donate

RR, 1.70 (1.22-2.36) Very low

Active learning

4 Before-after studies Lack RCTs; unclear risk of bias (+2) No inconsistency; I2 = 0% Direct (0) No serious imprecision Suspected publication bias (−1) Commitment to donate

96.4% (91.6-98.5%) Very low

Anticipated regret

2 RCTs All RCTs; mostly unclear risk of bias (+3) Some inconsistency; I2 = 32% (−1) Direct (0) No serious imprecision Suspected publication bias (−1) Willingness to donate

SMD, 0.39 (0.09-0.69) Low

Community partnership

2 CRCTs All CRCTs; high risk of bias (+2) Some inconsistency; I2 = 42% (−1) Direct (0) No serious imprecision Suspected publication bias (−1) Commitment to donate

RR, 3.00 (2.14-4.20) Very low

Advertising

5 Before-after studies Lack RCTs; unclear risk of bias (+2) No inconsistency; I2 = 0% Direct (0) No serious imprecision No publication bias (0) Positive intent to donate

Copyright © 2015 Wolters Kluwer Health, Inc. All rights reserved.

RR, 1.00 (0.97-1.03) Low

Li et al

2639

2640 Transplantation ■ December 2015 ■ Volume 99 ■ Number 12 www.transplantjournal.com

FIGURE 2. A, Meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials for commitment to donate and intention to donate. B, Meta-analysis of before-after

studies for commitment to donate and intention to donate.

with a significant increase in the proportion of participants CI, 0.09-0.69; I2 = 32%; P = 0.010). Participants who re-

documenting as committed donors (2 CRCTs, 4043 partici- ceived interventions that required active learning, such as im-

pants: RR, 3.00; 95% CI, 2.14-4.20; I2 = 42%; P < 0.001; plementing their own donation campaigns, experienced

PAR, 49.6%). Interventions that involved anticipated regret improved commitment to donate after being exposed to the

were associated with an improvement in the willingness to interventions (4 before-after studies, 322 participants: RR,

donate compared to questionnaires that did not use antici- 2.82; 95% CI, 2.13-3.72; I2 = 0%; P < 0.001). There was

pated regret (2 RCTs, 284 participants: SMD, 0.39; 95% no significant improvement in the proportion of participants

Copyright © 2015 Wolters Kluwer Health, Inc. All rights reserved.

© 2015 Wolters Kluwer Li et al 2641

FIGURE 2, continued. B. Meta-analysis of before-after studies for commitment to donate and intention to donate.

with positive intentions to donate after the introduction of 4536 participants: RR, 1.83; 95% CI, 0.99-3.37; I2 = 95%;

the advertising interventions (5 before-after studies, 6380 par- P = 0.05; PAR, 29.2%). A significant improvement in the

ticipants: RR, 1.00; 95% CI, 0.97-1.03; I2 = 0%; P = 0.93). commitment to donate (3 CRCTs, 4199 participants: RR,

2.28; 95% CI, 1.22-4.27; I2 = 91%; P = 0.01) was observed

after exclusion of a single study in which ethnically targeted

Targeted Populations educational materials with a religious focus were compared

Interventions targeted at ethnic minorities did not show a with ethnically targeted educational materials without a reli-

significant improvement in commitment to donate (4 CRCTs, gious focus.

Copyright © 2015 Wolters Kluwer Health, Inc. All rights reserved.

2642 Transplantation ■ December 2015 ■ Volume 99 ■ Number 12 www.transplantjournal.com

Interventions that did not target specific ethnic groups also latter, of translating a broad willingness to donate into a for-

resulted in a significant improvement in commitment to mal commitment, but are less consistently effective in shifting

donate (3 CRCTs, 1479 participants: RR, 1.43; 95% CI, people's attitudes toward donation. The implication of this is

1.03-1.98; I2 = 88%; P = 0.03). that intervention through community programs is best suited

to encouraging individuals already disposed to organ dona-

Geographic Location tion to formally register and in doing so, more generally, cap-

The majority of included studies (n = 46, 73%) were orig- italizing on the high level of support for organ donation that is

inated from the United States. There were no significant dif- known to exist in many countries. However, another possible

ferences in outcomes, such as willingness to donate, the explanation for these findings is that actions such as registra-

commitment to donate or positive intent to donate between tion and notifying family members are more objective and

studies conducted in the United States and those conducted hence may be more conclusively measured than studies that in-

elsewhere. cluded behavioural intentions.

Overall, our findings are broadly consistent with findings

Study Quality of previous reviews that suggest specific interventions may

Only 1 study30 was judged to have low-risk bias when con- be effective in increasing the willingness to be a deceased or-

sidering the commitment to donate as an outcome. This study gan donor,32,33 in the general community and ethnic minor-

reported a smaller but statistically significant improvement in ities.32,34 Additionally, this review quantifies the potential

commitment to donate between the intervention and control effectiveness of several specific intervention types, namely

arms (1 study, 952 participants: RR, 1.16; 95% CI, 1.08- community partnerships, active learning, and anticipated re-

1.24; P < 0.001). Similarly, the single RCT31 that reported gret, in improving the community willingness to be a deceased

willingness to donate as an outcome and was deemed to have organ donor.

a low risk of bias reported no significant differences in willing- Our study has several strengths. The inclusiveness of

ness to donate between intervention and controlled arm. our review enables it to assess the overall effectiveness of

community-based interventions in general and to compare

Adverse Events across different types of interventions and target populations.

Adverse events were not reported in any of the included We have also used the standardized approach of conducting

studies. a systematic review whereby a systematic search of medical

databases, data extraction and analysis, and trial quality as-

DISCUSSION sessment by 2 independent reviewers was conducted based

There was considerable variation in the types of community- on a prespecified protocol. Our review has several limita-

based interventions used to promote and improve the rates of tions. First, the mean follow-up time of all included studies

deceased donation in the general population. Broadly, interven- is short (60.5 days) so longer term outcomes are not avail-

tions included advertising, active learning, anticipated regret, able. Additionally, the included studies were of generally

community partnerships, a computer-tailored intervention, edu- low quality. Publication bias may also exist leading to an

cational materials, education by health professionals, interven- overestimation of treatment effect because trials or observa-

tions at DMV offices, opportunistic registration procedures, tional data with more favourable outcomes are more likely

passive learning, workplace interventions, and interventions to be published than studies with negative results. Although

with multiple main components. Evidence from RCTs sug- enquiry of the authors did not reveal additional information,

gested that community-based interventions, such as community there were insufficient studies to formally evaluate such bias.

partnerships and anticipated regret were effective in improving Systematic bias, such as performance bias and sampling bias,

the commitment to donate. Participants who received an inter- also exists when observational studies, particularly before

vention were 1.7 times (95% CI, 1.22-2.36) more likely to com- and after studies, were used to evaluate the effectiveness of

mit to being an organ donor compared to those that did not an intervention. We acknowledge that the limited number

receive any specific intervention. However, the overall risk of of participants in the included studies may preclude accurate

bias for individual studies was high, and this may have led to assessment of heterogeneity beyond chance. Our subgroup

overestimation of the true treatment effects of the interventions. analyses, although limited by the small number of included

In general, strategies that involved community partnership studies (n = 2-5), showed that the heterogeneity may partly

and active participation involving participants achieved the be explained by the effects of intervention types.

greatest impact in promoting deceased organ donation. Inter- Data were sparse in a number of areas. Reporting of

ventions that included active partnership with the community potential harms was only reported in a single study.30 In

increased the number of committed donors by approximately addition, given the relatively small number of studies avail-

50%, compared with no intervention. Specific interventions able in the meta-analyses, we were unable to explore all

that targeted ethnic communities with culturally sensitive outcomes across all study designs, or to perform detailed

approaches were also effective in increasing the number of subgroup analyses to explore interactions between the

committed donors by 29.2% compared to those who did types of interventions on the treatment efficacy between

not receive the interventions. the various types of intervention. Additionally, our review

The studies examined in this review highlight how the deci- included only studies that directly reported on changes in

sion to become an organ donor consists of 2 distinct steps: the willingness to be a deceased organ donor and did not

first, the adoption of in-principle support for donation and sec- consider indirect outcomes such as knowledge or opinions

ond, the translation of this support to a formal commitment about donation. The extent to which changes in these indi-

through registration. Our findings suggest that community- rect outcomes translate into actual increases in deceased

based interventions are generally effective in relation to the organ donations remains unclear.

Copyright © 2015 Wolters Kluwer Health, Inc. All rights reserved.

© 2015 Wolters Kluwer Li et al 2643

Overall, the evidence suggests that interventions may be ef- 13. Reubsaet A, Brug J, De Vet E, et al. The effects of practicing registration of

organ donation preference on self-efficacy and registration intention: an

fective in improving the willingness to be a deceased organ

enactive mastery experience. Psychol Health. 2003;18:585–594.

donor, however the quality of the current evidence is poor. 14. Reubsaet A, Brug J, Nijkamp MD, et al. The impact of an organ dona-

Well-powered and well-designed RCTs are needed to evalu- tion registration information program for high school students in the

ate the impact of opportunistic registration procedures, antic- Netherlands. Soc Sci Med. 2005;60:1479–1486.

ipated regret, and active learning on improving the number 15. Vinokur AD, Merion RM, Couper MP, et al. Educational web-based inter-

vention for high school students to increase knowledge and promote

of committed donors in the community. Process evaluations positive attitudes toward organ donation. Health Educ Behav. 2006;33:

alongside these intervention studies are also needed to iden- 773–786.

tify the barriers and facilitators to commit as organ donors 16. Andrews AM, Zhang N, Magee JC, et al. Increasing donor designation

and the impact that specific types of interventions may ulti- through black churches: results of a randomized trial. Prog Transplant.

2012;22:161–167.

mately have on deceased organ donation rates.

17. Rodrigue JR, Krouse J, Carroll C, et al. A department of motor vehicles

intervention yields moderate increases in donor designation rates. Prog

Transplant. 2012;22:18–24.

CONCLUSIONS 18. Singh M, Katz RC, Beauchamp K, et al. Effects of anonymous information

about potential organ transplant recipients on attitudes toward organ

Overall, we found a lack of consistency in methods and out- transplantation and the willingness to donate organs. J Behav Med.

come measures in studies. The overall quality of the evidence is 2002;25:469–476.

also low. Despite this, existing evidence suggests that commu- 19. Weaver M, Spigner C, Pineda M, et al. Knowledge and opinions about or-

nity partnerships, anticipated regret, and active learning may gan donation among urban high school students: pilot test of a health ed-

ucation program. Clin Transplant. 2000;14:292–303.

be promising approaches to increase individuals' willingness

20. Morgan SE, Stephenson MT, Afifi W, et al. The University Worksite Organ

to be a deceased organ donor in both the general community Donation Project: a comparison of two types of worksite campaigns on

and ethnic minorities. Future studies in the forms of well- the willingness to donate. Clin Transplant. 2011;25:600–605.

powered randomised controlled trials comparing the various 21. Morgan SE, Miller J, Arasaratman LA. Signing cards, saving lives: an eval-

forms of interventions, using consistent outcome measures, uation of the worksite organ donation promotion project. Commun

Monogr. 2002;69:253.

are likely to have a major impact on improving our confi- 22. Morgan SE, Harrison TR, Chewning LV, et al. The effectiveness of high-

dence in the treatment effectiveness of these techniques. and low-intensity worksite campaigns to promote organ donation: the

workplace partnership for life. (Author abstract)(Report). Commun Monogr.

2010;77:341–356.

23. D'Alessandro AM, Peltier JW, Dahl AJ. Use of social media and college

student organizations to increase support for organ donation and advo-

REFERENCES cacy: a case report. Prog Transplant. 2012;22:436–441.

1. NHS Blood and Transplant. Organ Donation and Transplantation 24. Fahrenwald NL, Belitz C, Keckler A. Outcome evaluation of 'sharing the gift

Activity Report 2012/13. London: NHS; 2013. Available at: http://www. of life': an organ and tissue donation educational program for American

organdonation.nhs.uk/statistics/transplant_activity_report/current_activity_ Indians. Am J Transplant. 2010;10:1453–1459.

reports/ukt/activity_report_2012_13.pdf. 25. Siegel JT, Alvaro EM, Crano WD, et al. Passive-positive organ donor reg-

2. Based on OPTN data as of 17 January 2014. istration behavior: a mixed method assessment of the IIFF Model. Psychol

3. Wright J, Narayan S. Analysis of kidney allocation during 2013. 2014. Health Med. 2010;15:198–209.

4. International Registry in Organ Donation and Transplantation. IRODaT 26. Harrison TR, Morgan SE, King AJ, et al. Saving lives branch by branch: the

Newsletter 2012. Available at: http://www.irodat.org/img/database/grafics/ effectiveness of driver licensing bureau campaigns to promote organ do-

newsletter/IRODaT Newsletter 2012.pdf. nor registry sign-ups to African Americans in Michigan. J Health Commun.

5. The Gallup Organisation. National Survey of Organ and Tissue Donation 2011;16:805–819.

Attitudes and Behaviors. Rockville, MD: Health Resources and Services 27. Zaramo CE, Morton T, Yoo JW, et al. Culturally competent methods

Administration; 2005. to promote organ donation rates among African-Americans using venues

6. Irving MJ, Tong A, Jan S, et al. Factors that influence the decision to be an of the Bureau of Motor Vehicles. Transplant Proc. 2008;40:1001–1004.

organ donor: a systematic review of the qualitative literature. Nephrol Dial 28. Merion RM, Vinokur AD, Couper MP, et al. Internet-based intervention to

Transplant. 2012;27:2526–2533. promote organ donor registry participation and family notification. Trans-

7. Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J; PRISMA Group, et al. Preferred reporting plantation. 2003;75:1175–1179.

items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. 29. Meier D, Schulz KH, Kuhlencordt R, et al. Effects of an educational seg-

BMJ. 2009;339:b2535. ment concerning organ donation and transplantation. Transplant Proc.

8. Higgins J, Green S. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Inter- 2000;32:62–63.

ventions. T.C. Collaboration; 2012. 30. Thornton JD, Alejandro-Rodriguez M, León JB, et al. Effect of an iPod

9. Cochrane Effective Practice and Organisation of Care Group. Suggested video intervention on consent to donate organs: a randomized trial. Ann

risk of bias criteria for EPOC reviews. 2012. Intern Med. 2012;156:483–490.

10. Guyatt GH, Oxman AD, Vist GE; GRADE Working Group, et al. GRADE: 31. McDonald DD, Ferreri R, Jin C, et al. Willingness to communicate organ

an emerging consensus on rating quality of evidence and strength of rec- donation intention. Public Health Nurs. 2007;24:151–159.

ommendations. BMJ. 2008;336:924–926. 32. Feeley TH, Moon S-i. A meta-analytic review of communication cam-

11. Quick BL, Bosch D, Morgan SE. Message framing and medium consider- paigns to promote organ donation. Commun Rep. 2009;22:63–73.

ations for recruiting newly eligible teen organ donor registrants. Am J 33. Li AH, Rosenblum AM, Nevis IF, et al. Adolescent classroom education on

Transplant. 2012;12:1593–1597. knowledge and attitudes about deceased organ donation: a systematic

12. Smits M, van den Borne B, Dijker AJ, et al. Increasing Dutch adolescents' review. Pediatr Transplant. 2013;17:119–128.

willingness to register their organ donation preference: the effectiveness of 34. Deedat S, Kenten C, Morgan M. What are effective approaches to in-

an education programme delivered by kidney transplantation patients. Eur creasing rates of organ donor registration among ethnic minority popula-

J Public Health. 2006;16:106–110. tions: a systematic review. BMJ Open. 2013;3:e003453.

Copyright © 2015 Wolters Kluwer Health, Inc. All rights reserved.

You might also like

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5822)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1093)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (852)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (590)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (898)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (540)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (349)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (822)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (122)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (403)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- Chapter 10 Neuropsychological Assessment and ScreeningDocument26 pagesChapter 10 Neuropsychological Assessment and ScreeningKadir Say'sNo ratings yet

- Care of The Hospitalized Patient With Acute Exacerbation of CopdDocument25 pagesCare of The Hospitalized Patient With Acute Exacerbation of CopdmiallyannaNo ratings yet

- Disruption of Nerves Coordinating Bowel Peristalsis Lab FindingsDocument1 pageDisruption of Nerves Coordinating Bowel Peristalsis Lab FindingsmiallyannaNo ratings yet

- Lead Poisoning and Recurrent Abdominal Pain: Case ReportDocument3 pagesLead Poisoning and Recurrent Abdominal Pain: Case ReportmiallyannaNo ratings yet

- Using Wellbeing For Public Policy: Theory, Measurement, and RecommendationsDocument35 pagesUsing Wellbeing For Public Policy: Theory, Measurement, and RecommendationsmiallyannaNo ratings yet

- Game of Thrones (Literary Committee) : Specialized Committees - 2014EDocument21 pagesGame of Thrones (Literary Committee) : Specialized Committees - 2014EmiallyannaNo ratings yet

- Help-Seeking BehaviorDocument6 pagesHelp-Seeking BehaviormiallyannaNo ratings yet

- Dot Grid PrintableDocument1 pageDot Grid PrintablemiallyannaNo ratings yet

- True Labor vs. False LaborDocument2 pagesTrue Labor vs. False LabormiallyannaNo ratings yet

- Descriptive and Analytical Study Designs: PH 146 - Epidemiology - B.S. Public Health, UP ManilaDocument5 pagesDescriptive and Analytical Study Designs: PH 146 - Epidemiology - B.S. Public Health, UP ManilamiallyannaNo ratings yet

- Carbohydrate MetabolismDocument15 pagesCarbohydrate Metabolismmiallyanna100% (2)

- C1 Atlas C2 Axis C3 - C6 Typical Cervical Vertebra C7 Vertebra ProminensDocument4 pagesC1 Atlas C2 Axis C3 - C6 Typical Cervical Vertebra C7 Vertebra ProminensmiallyannaNo ratings yet

- Musculoskeletal AgeingDocument82 pagesMusculoskeletal Ageingmiallyanna100% (1)

- Why The Bear Has Short TailDocument1 pageWhy The Bear Has Short TailmiallyannaNo ratings yet

- Group3 PH131 TheMusculoskeletalSystemandAging FWRDocument15 pagesGroup3 PH131 TheMusculoskeletalSystemandAging FWRmiallyannaNo ratings yet

- Glandular EpitheliumDocument13 pagesGlandular EpitheliummiallyannaNo ratings yet

- Gra-GO™: Rafaelo Paolo A. Fernandez Grade 7 - Valdocco General Technology Tr. MiggyDocument2 pagesGra-GO™: Rafaelo Paolo A. Fernandez Grade 7 - Valdocco General Technology Tr. MiggymiallyannaNo ratings yet

- Lipids PDFDocument71 pagesLipids PDFmiallyannaNo ratings yet

- Group 2 LIPIDS Formal Written ReportDocument7 pagesGroup 2 LIPIDS Formal Written ReportmiallyannaNo ratings yet

- Academic WritingDocument14 pagesAcademic WritingJulianne Descalsota LegaspiNo ratings yet

- Aicte Internship Approval Pending 1Document7 pagesAicte Internship Approval Pending 1Anisha KumariNo ratings yet

- Front Pages Front PageDocument9 pagesFront Pages Front PageDeepanshu GoyalNo ratings yet

- AlaviaDocument2 pagesAlaviawareternal1No ratings yet

- Psychogenic Pain 1Document23 pagesPsychogenic Pain 1Agatha Billkiss IsmailNo ratings yet

- Constitutional Law AssignmentDocument26 pagesConstitutional Law AssignmentSakshiNo ratings yet

- Private Schools BacoorDocument15 pagesPrivate Schools BacoorWarren Joseph MoisesNo ratings yet

- Peer Pressure Research 1Document30 pagesPeer Pressure Research 1Ezequiel GonzalezNo ratings yet

- PC Hardware Servicing CBCDocument61 pagesPC Hardware Servicing CBCamirvillas100% (1)

- Schools of PhilosophyDocument81 pagesSchools of PhilosophyMike Perez100% (4)

- TMDI Lesson Plan 1Document3 pagesTMDI Lesson Plan 1Diane VillNo ratings yet

- Notes On Time ManagementDocument10 pagesNotes On Time ManagementAldrinmarkquintanaNo ratings yet

- Observations Report StudentDocument12 pagesObservations Report StudentngonzalezkNo ratings yet

- Qulaitative and Quantitative MethodsDocument9 pagesQulaitative and Quantitative MethodskamalNo ratings yet

- Business Mathematics (OBE)Document10 pagesBusiness Mathematics (OBE)irene apiladaNo ratings yet

- SCHEME OF WORK TemplateDocument4 pagesSCHEME OF WORK TemplateIulian RaduNo ratings yet

- Icdl FaqsDocument10 pagesIcdl FaqsmariamdesktopNo ratings yet

- Ted 2011 Wa Less Stuff More Happiness Graham Hill 6 MinDocument3 pagesTed 2011 Wa Less Stuff More Happiness Graham Hill 6 MinPeetaceNo ratings yet

- Water Cycle Lesson Plan-1Document2 pagesWater Cycle Lesson Plan-1api-247375227100% (1)

- Subject: General Chemistry Test,: Date: May 2015Document7 pagesSubject: General Chemistry Test,: Date: May 2015PHƯƠNG ĐẶNG YẾNNo ratings yet

- Michelle D. Kelly RN, FNP, DNP (C) EducationDocument5 pagesMichelle D. Kelly RN, FNP, DNP (C) EducationMiserable*No ratings yet

- Stress in College Students Research PaperDocument6 pagesStress in College Students Research Paperttdqgsbnd100% (1)

- Test Result ConsolidationDocument4 pagesTest Result ConsolidationDONA FE SIADENNo ratings yet

- B1 UNIT 1 Everyday English Teacher's NotesDocument1 pageB1 UNIT 1 Everyday English Teacher's NotesXime OlariagaNo ratings yet

- Portfolio Guidelines For Unit 7 1: First Day of Class November 29 - Last Day of Class December 23Document7 pagesPortfolio Guidelines For Unit 7 1: First Day of Class November 29 - Last Day of Class December 23Edith BaosNo ratings yet

- FTS - Westville Prisons ApproachDocument1 pageFTS - Westville Prisons ApproachFeeding_the_SelfNo ratings yet

- ID 333 VDA 6.3 Upgrade Training ProgramDocument2 pagesID 333 VDA 6.3 Upgrade Training ProgramfauzanNo ratings yet

- Our Town Thesis StatementDocument7 pagesOur Town Thesis Statementlisarileymilwaukee100% (2)

- Office of The Senior High School Awards Committee: Application Form For Leadership Excellence AwardDocument2 pagesOffice of The Senior High School Awards Committee: Application Form For Leadership Excellence AwardDindo Arambala OjedaNo ratings yet