Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Bhabha of Mimicry and Man

Bhabha of Mimicry and Man

Uploaded by

Kevin Daniel RozoCopyright:

Available Formats

You might also like

- Moten Fred NotInBetweenLyricPaintingDocument23 pagesMoten Fred NotInBetweenLyricPaintingGray FisherNo ratings yet

- Mimicry BhabhaDocument10 pagesMimicry BhabhaPanji HandokoNo ratings yet

- Bhabha of Mimicry and Men PDFDocument10 pagesBhabha of Mimicry and Men PDFEnzo V. ToralNo ratings yet

- Bhabha - of Mimicry Anb Man - The Ambivalence of Colonial DiscourseDocument10 pagesBhabha - of Mimicry Anb Man - The Ambivalence of Colonial DiscourseGuerrila NowNo ratings yet

- On BhabhaDocument11 pagesOn BhabhaJulianaRocjNo ratings yet

- Acerca Del Colonialismo Inglés en La IndiaDocument2 pagesAcerca Del Colonialismo Inglés en La IndiauriceciliaNo ratings yet

- 10.4324 9780203820551-10 ChapterpdfDocument11 pages10.4324 9780203820551-10 ChapterpdfmnbvcxNo ratings yet

- Nomadic Power and Cultural Resistance - Critical Art EnsembleDocument24 pagesNomadic Power and Cultural Resistance - Critical Art EnsembleFederico AlvarezNo ratings yet

- Bhabha On Mimicry and ManDocument10 pagesBhabha On Mimicry and ManivonebarrigaNo ratings yet

- Dispossession and Civil Society The Ambivalence of Enlightenment Political PhilosophyDocument23 pagesDispossession and Civil Society The Ambivalence of Enlightenment Political Philosophy李璿No ratings yet

- Bahbha-Mimicry and ManDocument5 pagesBahbha-Mimicry and ManJaime GonzalezNo ratings yet

- Stoler Imperial Formations PDFDocument29 pagesStoler Imperial Formations PDFGarrison DoreckNo ratings yet

- 09 Young CH 09Document22 pages09 Young CH 09Marcel PopescuNo ratings yet

- Bhabha, Mimicry and ManDocument10 pagesBhabha, Mimicry and ManMadhupriya SenGuptaNo ratings yet

- Bhabha - of Mimicry and ManDocument10 pagesBhabha - of Mimicry and MankdiemanueleNo ratings yet

- Cesaire DiscourseDocument28 pagesCesaire DiscourseAngel CaméléonNo ratings yet

- Pynchon's Postmodern SublimeDocument12 pagesPynchon's Postmodern SublimeGiwrgosKalogirouNo ratings yet

- Imperial Alterity and Identity Slippage: The Sin of Becoming "Other" in Edmund D. Morel's "King Leopold's Rule in Africa"Document29 pagesImperial Alterity and Identity Slippage: The Sin of Becoming "Other" in Edmund D. Morel's "King Leopold's Rule in Africa"Cyril GerberNo ratings yet

- Stole R 2008Document29 pagesStole R 2008augustobianchiNo ratings yet

- Pocock, JCA. 1995.the Idea of Citizenship Sin Classical Times.Document6 pagesPocock, JCA. 1995.the Idea of Citizenship Sin Classical Times.Renato Benites GodosNo ratings yet

- Recreating The African City in - Ways of DyingDocument11 pagesRecreating The African City in - Ways of DyingGonzalo del AguilaNo ratings yet

- Radical Futurisms - Documentary's Chronopol - T. J. DemosDocument7 pagesRadical Futurisms - Documentary's Chronopol - T. J. DemosAbhisek BarmanNo ratings yet

- Flânerie For Cyborgs: Rob ShieldsDocument12 pagesFlânerie For Cyborgs: Rob ShieldsFelipe Luis GarciaNo ratings yet

- Indeterminate ThePracticeofEvDocument6 pagesIndeterminate ThePracticeofEvsusan_loloNo ratings yet

- Young, 1994, The African Coloniial State in Comparative Perspective - Chapter 1Document12 pagesYoung, 1994, The African Coloniial State in Comparative Perspective - Chapter 1Anelya NauryzbayevaNo ratings yet

- DetournementDocument1 pageDetournementjczenkoanNo ratings yet

- Mimicry Homi BhabhaDocument10 pagesMimicry Homi BhabhaDaniela KernNo ratings yet

- D. Kadir - Postmodernism - Postcolonialism - 1995Document8 pagesD. Kadir - Postmodernism - Postcolonialism - 1995gett13No ratings yet

- Capitalist Realism - Is There No Alternat - Mark FisherDocument86 pagesCapitalist Realism - Is There No Alternat - Mark FisherIon PopescuNo ratings yet

- Aesthetic Cocoon1Document15 pagesAesthetic Cocoon1Martina MiloševićNo ratings yet

- Luis E. Carranza - Le Corbusier and The Problems of RepresentationDocument13 pagesLuis E. Carranza - Le Corbusier and The Problems of Representationchns3No ratings yet

- 6 Doomed Is A Civilization That Glorifies MatterDocument5 pages6 Doomed Is A Civilization That Glorifies MatterSPAHIC OMERNo ratings yet

- Metropolis & KafkaDocument4 pagesMetropolis & Kafkabrandon aguilarNo ratings yet

- F451 - Dystopia HandoutDocument3 pagesF451 - Dystopia HandoutAaliyah GarciaNo ratings yet

- Berghahn BooksDocument14 pagesBerghahn BooksEduardo ParreiraNo ratings yet

- African Lit - Lecture 3Document15 pagesAfrican Lit - Lecture 3tikattungusNo ratings yet

- LE CORBUSIER AND THE PROBLEM OF REPRESENTATION - Luis E. CarranzaDocument13 pagesLE CORBUSIER AND THE PROBLEM OF REPRESENTATION - Luis E. Carranzaanapaula1978No ratings yet

- HOW NEWNESS ENTERS The WORLD Postmodem Space Postcolonial Times and The Trials of Cultural Translation-BkltDocument12 pagesHOW NEWNESS ENTERS The WORLD Postmodem Space Postcolonial Times and The Trials of Cultural Translation-BkltAsis YuurNo ratings yet

- Hayles - Is Utopia ObsoleteDocument8 pagesHayles - Is Utopia ObsoletemzzionNo ratings yet

- Chapter One:: Introduction and Theoretical BackgroundDocument24 pagesChapter One:: Introduction and Theoretical BackgroundCandido SantosNo ratings yet

- Among Slave Systems A Profile of Late Roman SlaveryDocument34 pagesAmong Slave Systems A Profile of Late Roman SlaveryT.No ratings yet

- Postcolonialism and GlobalisationDocument19 pagesPostcolonialism and GlobalisationExoplasmic ReticulumNo ratings yet

- India and Post-Colonial DiscourseDocument8 pagesIndia and Post-Colonial Discourseankitabehera0770% (1)

- Alien-Nation: Zombies, Immigrants, and Millennial CapitalismDocument28 pagesAlien-Nation: Zombies, Immigrants, and Millennial CapitalismDouglas Ferreira Gadelha CampeloNo ratings yet

- 05 Hatt-Klonk PostcolonialismDocument8 pages05 Hatt-Klonk PostcolonialismStergios SourlopoulosNo ratings yet

- The Aristocratic Touch: A Look Into The Innate Urges and Inevitable Outcomes of The Upper ClassDocument15 pagesThe Aristocratic Touch: A Look Into The Innate Urges and Inevitable Outcomes of The Upper ClassPatrick Tice-CarrollNo ratings yet

- FF Belcourt Issue6Document11 pagesFF Belcourt Issue6Calibán CatrileoNo ratings yet

- Fiend of FolktalesDocument5 pagesFiend of FolktalesPriyanka KumariNo ratings yet

- Folk of Folk Horror Paper Jan 2022 PDFDocument4 pagesFolk of Folk Horror Paper Jan 2022 PDFGerardo TrinidadNo ratings yet

- Sellars Hakim BeyDocument27 pagesSellars Hakim BeyJoachim Emidio Ribeiro SilvaNo ratings yet

- Atkinson OusmaneSembneWe 1993Document7 pagesAtkinson OusmaneSembneWe 1993Khyati ParasharNo ratings yet

- Presentation EssayDocument8 pagesPresentation EssayCall Me SenpaiNo ratings yet

- London William BlakeDocument11 pagesLondon William Blakenoorttv5No ratings yet

- Capitalist Realism IntroDocument17 pagesCapitalist Realism IntroUsama AlshaibiNo ratings yet

- Marxism and OppressionDocument9 pagesMarxism and OppressionPSTordillaNo ratings yet

- Verso - Dystopian On Trial: Alice Coleman's Architectural Determinism by Robert BevanDocument5 pagesVerso - Dystopian On Trial: Alice Coleman's Architectural Determinism by Robert BevanrpmbevanNo ratings yet

- Reality: Simulations - the Analytical Audacity of Jean BaudrillardFrom EverandReality: Simulations - the Analytical Audacity of Jean BaudrillardNo ratings yet

- The Cask of AmontilladoDocument43 pagesThe Cask of AmontilladoZechaina Udo100% (2)

- NMTC Test Papers Prelims All Levels 2016Document15 pagesNMTC Test Papers Prelims All Levels 2016tannyNo ratings yet

- Integration Broker BasicsDocument6 pagesIntegration Broker Basicsharikishore14No ratings yet

- Consti CasesDocument143 pagesConsti CasesPantas DiwaNo ratings yet

- Bacarro Vs CastanoDocument2 pagesBacarro Vs CastanoMaiti LagosNo ratings yet

- Guid Line Drug TX PDFDocument707 pagesGuid Line Drug TX PDFmaezu100% (1)

- IMUNISASIDocument26 pagesIMUNISASINadia KhoiriyahNo ratings yet

- 9702 m19 Ms 12Document3 pages9702 m19 Ms 12And rewNo ratings yet

- Ghana Maketing PlanDocument11 pagesGhana Maketing PlanchiranrgNo ratings yet

- Final Nancy121Document66 pagesFinal Nancy121Sahil SethiNo ratings yet

- PERT Estimation Technique: Optimistic Pessimistic Most LikelyDocument2 pagesPERT Estimation Technique: Optimistic Pessimistic Most LikelysumilogyNo ratings yet

- "Behavioral and Experimental Economics": Written Exam For The M.Sc. in Economics 2010-IDocument4 pages"Behavioral and Experimental Economics": Written Exam For The M.Sc. in Economics 2010-ICoxorange94187No ratings yet

- Educ - MidtermDocument8 pagesEduc - MidtermAn Jannette AlmodielNo ratings yet

- Tanuj Bohra - HRM - Individual Assignment PDFDocument6 pagesTanuj Bohra - HRM - Individual Assignment PDFTanuj BohraNo ratings yet

- Project On Recruit Ment SlectionDocument6 pagesProject On Recruit Ment SlectionSunny KhushdilNo ratings yet

- Whitehead Et Al. 2009Document11 pagesWhitehead Et Al. 2009Benedikt EngelNo ratings yet

- Rune E. A. Johansson - Pali Buddhist Texts, 3ed 1981Document161 pagesRune E. A. Johansson - Pali Buddhist Texts, 3ed 1981Anders Fernstedt100% (9)

- Cricket SepepDocument7 pagesCricket Sepepapi-308918232No ratings yet

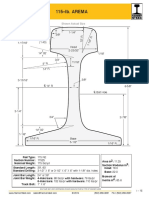

- Arema 115REDocument1 pageArema 115REAntonioNo ratings yet

- Tanjong PLC: Major Shareholder Privatising Tanjong at RM21.80/Share - 02/08/2010Document3 pagesTanjong PLC: Major Shareholder Privatising Tanjong at RM21.80/Share - 02/08/2010Rhb InvestNo ratings yet

- Carrigan 2001Document44 pagesCarrigan 2001TeodoraNo ratings yet

- Grade 3 Home Learning Animal Research ProjectDocument5 pagesGrade 3 Home Learning Animal Research Projectapi-363677682No ratings yet

- Ebook Handbook of The Psychology of Aging PDF Full Chapter PDFDocument67 pagesEbook Handbook of The Psychology of Aging PDF Full Chapter PDFforest.gertelman418100% (39)

- Math Lesson 23Document5 pagesMath Lesson 23api-461550649No ratings yet

- UE18EE325 - Unit1 - Class4 - Performance Characteristics-StaticDocument16 pagesUE18EE325 - Unit1 - Class4 - Performance Characteristics-StaticGAYATHRI DEVI BNo ratings yet

- Intro To Genetic EngineeringDocument84 pagesIntro To Genetic EngineeringMhimi ViduyaNo ratings yet

- Children's Classics in Dramatic FormBook Two by Stevenson, AugustaDocument95 pagesChildren's Classics in Dramatic FormBook Two by Stevenson, AugustaGutenberg.orgNo ratings yet

- BABOK V2 - All ChaptersDocument20 pagesBABOK V2 - All ChaptersSmith And YNo ratings yet

- Characteristics That Define Our VictoryDocument5 pagesCharacteristics That Define Our VictoryLouie BiasongNo ratings yet

- Chapter 2 - Auditing IT Governance Controls: True/FalseDocument9 pagesChapter 2 - Auditing IT Governance Controls: True/FalseShanygane Delos SantosNo ratings yet

Bhabha of Mimicry and Man

Bhabha of Mimicry and Man

Uploaded by

Kevin Daniel RozoOriginal Description:

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Bhabha of Mimicry and Man

Bhabha of Mimicry and Man

Uploaded by

Kevin Daniel RozoCopyright:

Available Formats

Of Mimicry and Man: The Ambivalence of Colonial Discourse

Author(s): Homi Bhabha

Source: October, Vol. 28, Discipleship: A Special Issue on Psychoanalysis (Spring, 1984), pp.

125-133

Published by: The MIT Press

Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/778467 .

Accessed: 20/07/2013 12:33

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at .

http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp

.

JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of

content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms

of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org.

The MIT Press is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to October.

http://www.jstor.org

This content downloaded from 129.100.249.53 on Sat, 20 Jul 2013 12:33:09 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Of Mimicry and Man:

The Ambivalence of

Colonial Discourse*

HOMI BHABHA

Mimicryrevealssomething in sofar as it is

distinct

from what might calledan itself

be

thatis behind.The effect ofmimicry is cam-

ouflage.... It is nota questionofharmoniz-

ingwiththebackground, butagainsta mottled

background, ofbecoming mottled-exactly like

thetechniqueofcamouflage practisedinhuman

warfare.

-Jacques Lacan,

"The Line and Light," Of theGaze.

It is outofseasonto questionat thistimeof

day,theoriginalpolicyofconferring on every

colony of theBritishEmpire a mimic represen-

tationof theBritishConstitution. But ifthe

creature so endowedhas sometimes forgotten

its real insignificanceand underthefancied

importance ofspeakers and maces,and all the

paraphernalia and ceremoniesoftheimperial

legislature,has daredtodefythemother coun-

try,shehas tothankherselffor thefollyofcon-

ferringsuchprivileges ona conditionofsociety

thathas no earthly claimtoso exalteda posi-

tion.Afundamental principleappearstohave

beenforgotten or overlookedin oursystem of

colonialpolicy- thatofcolonialdependence.

To givetoa colonytheformsofindependence

is a mockery;shewouldnotbea colony fora

singlehourifshecouldmaintainan indepen-

dentstation.

Sir Edward Cust,

-

"Reflectionson West AfricanAffairs. .

addressed to the Colonial Office,"

Hatchard, London 1839.

This content downloaded from 129.100.249.53 on Sat, 20 Jul 2013 12:33:09 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

126 OCTOBER

The discourse of post-EnlightenmentEnglish colonialism oftenspeaks in

a tongue that is forked,not false. If colonialism takes power in the name of

history,it repeatedlyexercisesits authoritythroughthe figuresof farce. For the

epic intentionof the civilizingmission, "human and not whollyhuman" in the

famous words of Lord Rosebery, "writby the fingerof the Divine" 1 oftenpro-

duces a textrichin the traditionsof trompe l'oeil,irony,mimicry,and repetition.

In this comic turn fromthe high ideals of the colonial imagination to its low

mimeticliteraryeffects,mimicryemerges as one of the most elusive and effec-

tive strategiesof colonial power and knowledge.

Withinthatconflictualeconomy ofcolonial discourse which Edward Said2

describes as the tension between the synchronicpanoptical vision of domina-

tion- the demand for identity,stasis- and the counter-pressureof the dia-

chrony of history- change, difference -

mimicryrepresentsan ironiccompro-

mise. If I may adapt Samuel Weber's formulationof the marginalizingvision of

castration,3then colonial mimicryis the desire for a reformed,recognizable

thatis almostthesame,butnotquite.Which is to say,

Other, as a subjectofa difference

that the discourse of mimicryis constructedaround an ambivalence; in order to

be effective,mimicry must continually produce its slippage, its excess, its

difference.The authorityof that mode of colonial discourse that I have called

mimicryis thereforestrickenby an indeterminacy:mimicryemerges as the

representationof a differencethat is itselfa process of disavowal. Mimicry is,

thus, the sign of a double articulation;a complex strategyof reform,regulation,

and discipline, which"appropriates"the Other as it visualizes power. Mimicry

is also the sign of the inappropriate, however, a differenceor recalcitrance

which coheres the dominant strategicfunctionof colonial power, intensifies

surveillance, and poses an immanent threatto both "normalized"knowledges

and disciplinarypowers.

The effectof mimicryon the authorityof colonial discourse is profound

and disturbing.For in "normalizing"the colonial state or subject, the dream of

post-Enlightenmentcivilityalienates its own language of libertyand produces

another knowledge of its norms. The ambivalence which thus informsthis

strategyis discernible, for example, in Locke's Second Treatise which splits

to reveal the limitationsof libertyin his double use of the word "slave": first

simply,descriptivelyas the locus of a legitimateformof ownership,then as the

* This paper was firstpresented as a contribution to a panel on "Colonialist and Post-

Colonialist Discourse," organized by Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak for the Modern Language

Association Convention in New York, December 1983. I would like to thank ProfessorSpivak for

inviting me to participate on the panel and Dr. Stephan Feuchtwang for his advice in the

preparation of the paper.

1. Cited in Eric Stokes, The PoliticalIdeas ofEnglishImperialism,Oxford, Oxford University

Press, 1960, pp. 17-18.

2. Edward Said, Orientalism, New York, Pantheon Books, 1978, p. 240.

3. Samuel Weber: "The Sideshow, Or: Remarks on a Canny Moment," ModernLanguage

Notes,vol. 88, no. 6 (1973), p. 1112.

This content downloaded from 129.100.249.53 on Sat, 20 Jul 2013 12:33:09 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

of ColonialDiscourse

TheAmbivalence 127

trope foran intolerable, illegitimateexercise of power. What is articulated in

thatdistance between the two uses is the absolute, imagined differencebetween

the "Colonial" State of Carolina and the Original State of Nature.

It is fromthis area between mimicryand mockery,where the reforming,

civilizingmission is threatenedby the displacing gaze of itsdisciplinarydouble,

thatmy instancesof colonial imitationcome. What theyall share is a discursive

process by which the excess or slippage produced by the ambivalence of mimicry

(almost the same, but notquite)does not merely "rupture"the discourse, but

becomes transformedinto an uncertaintywhich fixesthe colonial subject as a

"partial"presence. By "partial"I mean both "incomplete"and "virtual."It is as if

the very emergence of the "colonial" is dependent for its representationupon

some strategiclimitationor prohibitionwithinthe authoritativediscourse itself.

The success of colonial appropriationdepends on a proliferation of inappropriate

objects that ensure its strategicfailure,so that mimicryis at once resemblance

and menace.

A classic text of such partialityis Charles Grant's "Observations on the

State of Society among the Asiatic Subjects of Great Britain"(1792)4 whichwas

only superseded by James Mills's HistoryofIndia as the most influentialearly

nineteenth-century account of Indian manners and morals. Grant's dream of

an evangelical system of mission education conducted uncompromisinglyin

English was partlya belief in political reformalong Christian lines and partly

an awareness that the expansion of company rule in India required a systemof

"interpellation"-a reformof manners, as Grant put it, thatwould provide the

colonial with"a sense of personal identityas we know it." Caught between the

desire for religious reformand the fear that the Indians might become tur-

bulent for liberty,Grant implies that it is, in fact the "partial" diffusionof

Christianity,and the"partial"influenceof moral improvementswhichwill con-

structa particularlyappropriateformof colonial subjectivity.What is suggested

is a process of reformthroughwhich Christian doctrines might collude with

divisive caste practices to preventdangerous political alliances. Inadvertently,

Grant produces a knowledge of Christianityas a formof social controlwhich

conflictswith the enunciatory assumptions which authorize his discourse. In

suggesting,finally,that"partial reform"will produce an emptyformof"the im-

itationof English manners which will induce them [the colonial subjects] to re-

main under our protection,"'5 Grant mocks his moral project and violates the

Evidences of central missionary forbade any

Christianity--a

tolerance of heathen faiths. tenet--which

The absurd extravagance of Macaulay's InfamousMinute(1835)- deeply

influencedby Charles Grant's Observations- makes a mockeryofOriental learn-

4. Charles Grant, "Observations on the State of Society among the Asiatic Subjects of Great

Britain," SessionalPapers1812-13, X (282), East India Company.

5. Ibid., chap. 4, p. 104.

This content downloaded from 129.100.249.53 on Sat, 20 Jul 2013 12:33:09 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

128 OCTOBER

ing untilfaced withthe challenge of conceivingof a "reformed"colonial subject.

Then the greattraditionof European humanismseems capable onlyofironizing

itself.At the intersectionof European learning and colonial power, Macaulay

can conceive of nothingother than "a class of interpretersbetween us and the

millions whom we govern- a class of persons Indian in blood and colour, but

English in tastes, in opinions, in morals and in intellect'6- in other words a

mimic man raised "throughour English School," as a missionaryeducationist

wrote in 1819, "to form a corps of translatorsand be employed in different

departmentsof Labour."' The line of descent of the mimic man can be traced

throughthe worksof Kipling, Forester,Orwell, Naipaul, and to his emergence,

most recently,in Benedict Anderson's excellent essay on nationalism, as the

anomalous Bipin Chandra Pal.8 He is the effectofa flawedcolonial mimesis,in

which to be Anglicized, is emphaticallynot to be English.

The figureof mimicryis locatable withinwhat Anderson describes as "the

inner incompatibilityof empire and nation."' It problematizes the signs of

racial and cultural priority,so that the "national" is no longer naturalizable.

What emerges between mimesis and mimicryis a writing, a mode of represen-

tation, that marginalizes the monumentalityof history,quite simplymocks its

power to be a model, thatpower which supposedly makes it imitable. Mimicry

repeatsrather than re-presents and in that diminishing perspective emerges

Decoud's displaced European vision of Sulaco as

the endlessness of civil strifewhere follyseemed even harder to bear

than its ignominy. . . the lawlessness of a populace of all colours and

races, barbarism, irremediabletyranny.. . . America is ungovern-

able.10

Or Ralph Singh's apostasy in Naipaul's TheMimic Men:

We pretended to be real, to be learning, to be preparing ourselves

forlife,we mimic men of the New World, one unknowncornerof it,

with all its remindersof the corruptionthat came so quickly to the

new.11

Both Decoud and Singh, and in theirdifferent ways Grant and Macaulay, are

the parodists of history.Despite theirintentionsand invocations theyinscribe

the colonial texterratically,eccentricallyacross a body politicthatrefusesto be

6. T. B. Macaulay, "Minute on Education," in SourcesofIndian Tradition,vol. II, ed. William

Theodore de Bary, New York, Columbia University Press, 1958, p. 49.

7. Mr. Thomason's communication to the Church Missionary Society, September 5, 1819, in

The MissionaryRegister,1821, pp. 54-55.

8. Benedict Anderson, ImaginedCommunities, London, Verso, 1983, p. 88.

9. Ibid., pp. 88-89.

10. Joseph Conrad, Nostromo,London, Penguin, 1979, p. 161.

11. V. S. Naipaul, The Mimic Men, London, Penguin, 1967, p. 146.

This content downloaded from 129.100.249.53 on Sat, 20 Jul 2013 12:33:09 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

of ColonialDiscourse

The Ambivalence 129

representative,in a narrativethat refusesto be representational.The desire to

emerge as "authentic" through mimicry- through a process of writing and

repetition-is the final irony of partial representation.

What I have called mimicryis not the familiarexerciseof dependent colonial

relations throughnarcissisticidentificationso that, as Fanon has observed,12

the black man stops being an actional person foronly the whiteman can repre-

sent his self-esteem.Mimicry conceals no presence or identitybehind its mask:

it is not what Cesaire describes as "colonization-thingification"13 behind which

therestandsthe essence of thepresence Africaine.The menace ofmimicryis itsdouble

vision which in disclosingthe ambivalence of colonial discourse also disruptsits

authority.And it is a double-vision that is a resultof what I've described as the

partial representation/recognition of the colonial object. Grant's colonial as

partial imitator,Macaulay's translator,Naipaul's colonial politician as play-

actor, Decoud as the scene setterof the opirabouffe of the New World, these are

the appropriate objects of a colonialist chain of command, authorized versions

of otherness.But theyare also, as I have shown, the figuresof a doubling, the

part-objectsof a metonymyof colonial desire which alienates the modalityand

normalityof those dominantdiscoursesin which theyemerge as "inappropriate"

colonial subjects. A desire that, throughthe repetitionofpartialpresence, which

is the basis of mimicry,articulates those disturbances of cultural, racial, and

historicaldifferencethat menace the narcissisticdemand of colonial authority.

It is a desire thatreverses"in part"the colonial appropriationby now producing

a partial vision of the colonizer's presence. A gaze of otherness,that shares the

acuity of the genealogical gaze which, as Foucault describes it, liberates mar-

ginal elements and shattersthe unityof man's being throughwhich he extends

his sovereignty.'4

I want to turn to this process by which the look of surveillancereturnsas

the displacing gaze of the disciplined,where the observerbecomes the observed

and "partial" representation rearticulates the whole notion of identity and

alienates it from essence. But not before observing that even an exemplary

history like Eric Stokes's The English Utilitariansin India acknowledges the

anomalous gaze of otherness but finally disavows it in a contradictoryut-

terance:

Certainly India played no central part in fashioningthe distinctive

qualities of English civilisation. In many ways it acted as a disturb-

ing force, a magnetic power placed at the periphery tending to

distortthe natural development of Britain's character. . . .5

12. Frantz Fanon, Black Skin, WhiteMasks, London, Paladin, 1970, p. 109.

13. Aime Cesaire, Discourseon Colonialism,New York, Monthly Review Press, 1972, p. 21

14. Michel Foucault, "Nietzche, Genealogy, History," in Language, Counter-Memory, Practice,

trans. Donald F. Bouchard and Sherry Simon, Ithaca, Cornell University Press, p. 153.

15. Eric Stokes, TheEnglishUtilitarians

and India, Oxford, Oxford UniversityPress, 1959, p. xi.

This content downloaded from 129.100.249.53 on Sat, 20 Jul 2013 12:33:09 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

130 OCTOBER

What is the nature of the hidden threat of the partial gaze? How does

mimicryemerge as the subject of the scopic drive and the object of colonial

surveillance? How is desire disciplined, authoritydisplaced?

If we turnto a Freudian figureto address theseissues ofcolonial textuality,

that form of differencethat is mimicry-almost the same but not quite-will

become clear. Writing of the partial nature of fantasy,caught inappropriately,

between the unconscious and the preconscious,making problematic,like mim-

icry,the very notion of "origins,"Freud has this to say:

Their mixed and splitoriginis what decides theirfate.We may com-

pare themwithindividuals of mixed race who taken all round resem-

ble white men but who betraytheircoloured descent by some strik-

ing featureor other and on that account are excluded fromsociety

and enjoy none of the privileges.16

Almostthesamebutnotwhite:. the visibilityof mimicryis always produced at

the site of interdiction.It is a formof colonial discourse thatis utteredinterdicta:

a discourse at the crossroads of what is known and permissibleand that which

though known must be kept concealed; a discourse utteredbetween the lines

and as such both against the rules and within them. The question of the

representationof differenceis thereforealways also a problem of authority.

The "desire"of mimicry,which is Freud's striking featurethatreveals so littlebut

makes such a big difference,is not merelythat impossibilityof the Other which

repeatedlyresistssignification.The desire of colonial mimicry- an interdictory

desire-may not have an object, but it has strategicobjectiveswhich I shall call

the metonymy ofpresence.

Those inappropriate signifiersof colonial discourse- the differencebe-

tween being English and being Anglicized; the identitybetween stereotypes

which, throughrepetition,also become different;the discriminatoryidentities

constructedacross traditional cultural norms and classifications,the Simian

Black, the Lying Asiatic- all these are metonymies of presence. They are

strategiesof desire in discourse that make the anomalous representationof the

colonized somethingotherthan a process of "the returnof the repressed,"what

Fanon unsatisfactorilycharacterized as collective catharsis.17These instances

of metonymyare the nonrepressiveproductionsof contradictoryand multiple

belief. They cross the boundaries of the culture of enunciation through a

strategicconfusionof the metaphoricand metonymicaxes of the cultural pro-

duction of meaning. For each of these instances of "a differencethat is almost

the same but not quite" inadvertentlycreates a crisis forthe cultural priority

given to the metaphoric as the process of repression and substitutionwhich

negotiates the difference between paradigmatic systemsand classifications.In

16. Sigmund Freud, "The Unconscious" (1915), SE, XIV, pp. 190-191.

17. Fanon, p. 103.

This content downloaded from 129.100.249.53 on Sat, 20 Jul 2013 12:33:09 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

TheAmbivalence

of ColonialDiscourse 131

mimicry,the representationof identityand meaning is rearticulatedalong the

axis of metonymy.As Lacan reminds us, mimicryis like camouflage, not a

harmonization or repression of difference,but a form of resemblance that

differs/defends presence by displaying it in part, metonymically.Its threat, I

would add, comes fromthe prodigious and strategicproductionof conflictual,

fantastic,discriminatory"identityeffects"in the play of a power that is elusive

because it hides no essence, no "itself."And that formof resemblanceis the most

to

terrifyingthing behold, as Edward Long testifiesin his HistoryofJamaica

(1774). At the end of a tortured,negrophobicpassage, that shiftsanxiouslybe-

tween piety, prevarication, and perversion, the text finallyconfrontsits fear;

nothingother than the repetitionof its resemblance "in part":

(Negroes) are representedby all authors as the vilestof human kind,

to which they have littlemore pretensionof resemblance thanwhat

arisesfromtheirexterior

forms(my italics).18

From such a colonial encounterbetween the white presence and its black

semblance, there emerges the question of the ambivalence of mimicryas a

problematicof colonial subjection. For if Sade's scandalous theatricalizationof

language repeatedlyremindsus thatdiscourse can claim "no priority,"then the

workof Edward Said will not let us forgetthatthe"ethnocentricand erraticwill

to power fromwhich textscan spring"''19 is itselfa theaterof war. Mimicry, as

the metonymyof presence is, indeed, such an erratic, eccentric strategyof

authorityin colonial discourse. Mimicry does not merely destroynarcissistic

authoritythroughthe repetitiousslippage of differenceand desire. It is the pro-

cess of thefixationof the colonial as a formofcross-classificatory, discriminatory

knowledge in the defilesof an interdictorydiscourse, and thereforenecessarily

raises the question of the authorization of colonial representations.A question of

authority that goes beyond the subject's lack of priority(castration) to a

historicalcrisis in the conceptualityof colonial man as an objectof regulatory

power, as the subject of racial, cultural, national representation.

"This culture . . . fixed in its colonial status," Fanon suggests,"(is) both

presentand mummified,it testifiedagainst its members. It definesthem in fact

without appeal.'"20 The ambivalence of mimicry- almost but not quite - sug-

gests that the fetishizedcolonial culture is potentiallyand strategicallyan in-

surgent counter-appeal. What I have called its "identity-effects," are always

crucially split. Under cover of camouflage, mimicry, like the fetish,is a part-

object that radically revalues the normative knowledges of the priorityof race,

writing,history. For the fetishmimes the formsof authorityat the point at

18. Edward Long, A HistoryofJamaica, 1774, vol. II, p. 353.

19. Edward Said, "The Text, the World, the Critic," in TextualStrategies,

ed. J. V. Harari,

Ithaca, Cornell University Press, 1979, p. 184.

20. Frantz Fanon, "Racism and Culture," in Toward theAfricanRevolution,London, Pelican,

1967, p. 44.

This content downloaded from 129.100.249.53 on Sat, 20 Jul 2013 12:33:09 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

132 OCTOBER

which it deauthorizes them. Similarly,mimicryrearticulatespresence in terms

of its "otherness,"that which it disavows. There is a crucial differencebetween

this colonialarticulationof man and his doubles and that which Foucault de-

scribes as "thinkingthe unthought"21 which, fornineteenth-century Europe, is

the ending of man's alienation by reconcilinghim withhis essence. The colonial

discourse that articulatesan interdictory

"otherness"is preciselythe "otherscene"

of this nineteenth-centuryEuropean desire for an authentic historical con-

sciousness.

The "unthought"across whichcolonial man is articulatedis thatprocess of

classificatoryconfusionthatI have describedas themetonymyofthe substitutive

chain of ethical and cultural discourse. This results in the splitting

of colonial

discourse so thattwo attitudestowardsexternalrealitypersist;one takes reality

into consideration while the other disavows it and replaces it by a product of

desire that repeats, rearticulates"reality"as mimicry.

So Edward Long can say withauthority,quoting variously, Hume, East-

wick, and Bishop Warburton in his support, that:

Ludicrous as the opinion may seem I do not thinkthatan orangutang

husband would be any dishonour to a Hottentotfemale.22

Such contradictoryarticulations of reality and desire- seen in racist

stereotypes,statements,jokes, myths- are not caught in the doubtfulcircle of

the returnof the repressed. They are the effectsof a disavowal that denies the

differencesofthe otherbut produces in its stead formsof authorityand multiple

beliefthat alienate the assumptions of "civil"discourse. If, fora while, the ruse

of desire is calculable for the uses of discipline soon the repetitionof guilt,

justification,pseudoscientifictheories, superstition,spurious authorities,and

classificationscan be seen as the desperate effortto "normalize"formallythe

disturbance of a discourse of splittingthat violates the rational, enlightened

claims of its enunciatorymodality. The ambivalence of colonial authorityre-

peatedly turns from mimicry-a differencethat is almost nothing but not

quite-to menace-a differencethat is almost total but not quite. And in that

other scene of colonial power, where historyturns to farce and presence to "a

part," can be seen the twin figuresof narcissismand paranoia that repeat furi-

ously, uncontrollably.

In the ambivalent world of the "not quite/notwhite," on the margins of

metropolitandesire, thefoundingobjectsof the Western world become the er-

of the colonial discourse- the part-objects

ratic,eccentric,accidentalobjetstrouvis

of presence. It is then that the body and the book loose theirrepresentational

authority.Black skin splitsunder the racist gaze, displaced into signs of besti-

21. Michel Foucault, The Orderof Things,New York, Pantheon, 1970, part II, chap. 9.

22. Long, p. 364.

This content downloaded from 129.100.249.53 on Sat, 20 Jul 2013 12:33:09 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

of ColonialDiscourse

TheAmbivalence 133

ality, genitalia, grotesquerie,which reveal the phobic mythof the undifferenti-

ated whole white body. And the holiest of books - the Bible - bearing both the

standard of the cross and the standard of empire findsitselfstrangelydismem-

bered. In May 1817 a missionarywrote fromBengal:

Still everyonewould gladly receive a Bible. And why?- that he may

lay it up as a curiosityfora fewpice; or use it forwaste paper. Such

it is well known has been the common fate of these copies of the

Bible. . . . Some have been bartered in the markets, others have

been thrownin snuffshops and used as wrapping paper.23

23. The MissionaryRegister,May 1817, p. 186.

This content downloaded from 129.100.249.53 on Sat, 20 Jul 2013 12:33:09 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

You might also like

- Moten Fred NotInBetweenLyricPaintingDocument23 pagesMoten Fred NotInBetweenLyricPaintingGray FisherNo ratings yet

- Mimicry BhabhaDocument10 pagesMimicry BhabhaPanji HandokoNo ratings yet

- Bhabha of Mimicry and Men PDFDocument10 pagesBhabha of Mimicry and Men PDFEnzo V. ToralNo ratings yet

- Bhabha - of Mimicry Anb Man - The Ambivalence of Colonial DiscourseDocument10 pagesBhabha - of Mimicry Anb Man - The Ambivalence of Colonial DiscourseGuerrila NowNo ratings yet

- On BhabhaDocument11 pagesOn BhabhaJulianaRocjNo ratings yet

- Acerca Del Colonialismo Inglés en La IndiaDocument2 pagesAcerca Del Colonialismo Inglés en La IndiauriceciliaNo ratings yet

- 10.4324 9780203820551-10 ChapterpdfDocument11 pages10.4324 9780203820551-10 ChapterpdfmnbvcxNo ratings yet

- Nomadic Power and Cultural Resistance - Critical Art EnsembleDocument24 pagesNomadic Power and Cultural Resistance - Critical Art EnsembleFederico AlvarezNo ratings yet

- Bhabha On Mimicry and ManDocument10 pagesBhabha On Mimicry and ManivonebarrigaNo ratings yet

- Dispossession and Civil Society The Ambivalence of Enlightenment Political PhilosophyDocument23 pagesDispossession and Civil Society The Ambivalence of Enlightenment Political Philosophy李璿No ratings yet

- Bahbha-Mimicry and ManDocument5 pagesBahbha-Mimicry and ManJaime GonzalezNo ratings yet

- Stoler Imperial Formations PDFDocument29 pagesStoler Imperial Formations PDFGarrison DoreckNo ratings yet

- 09 Young CH 09Document22 pages09 Young CH 09Marcel PopescuNo ratings yet

- Bhabha, Mimicry and ManDocument10 pagesBhabha, Mimicry and ManMadhupriya SenGuptaNo ratings yet

- Bhabha - of Mimicry and ManDocument10 pagesBhabha - of Mimicry and MankdiemanueleNo ratings yet

- Cesaire DiscourseDocument28 pagesCesaire DiscourseAngel CaméléonNo ratings yet

- Pynchon's Postmodern SublimeDocument12 pagesPynchon's Postmodern SublimeGiwrgosKalogirouNo ratings yet

- Imperial Alterity and Identity Slippage: The Sin of Becoming "Other" in Edmund D. Morel's "King Leopold's Rule in Africa"Document29 pagesImperial Alterity and Identity Slippage: The Sin of Becoming "Other" in Edmund D. Morel's "King Leopold's Rule in Africa"Cyril GerberNo ratings yet

- Stole R 2008Document29 pagesStole R 2008augustobianchiNo ratings yet

- Pocock, JCA. 1995.the Idea of Citizenship Sin Classical Times.Document6 pagesPocock, JCA. 1995.the Idea of Citizenship Sin Classical Times.Renato Benites GodosNo ratings yet

- Recreating The African City in - Ways of DyingDocument11 pagesRecreating The African City in - Ways of DyingGonzalo del AguilaNo ratings yet

- Radical Futurisms - Documentary's Chronopol - T. J. DemosDocument7 pagesRadical Futurisms - Documentary's Chronopol - T. J. DemosAbhisek BarmanNo ratings yet

- Flânerie For Cyborgs: Rob ShieldsDocument12 pagesFlânerie For Cyborgs: Rob ShieldsFelipe Luis GarciaNo ratings yet

- Indeterminate ThePracticeofEvDocument6 pagesIndeterminate ThePracticeofEvsusan_loloNo ratings yet

- Young, 1994, The African Coloniial State in Comparative Perspective - Chapter 1Document12 pagesYoung, 1994, The African Coloniial State in Comparative Perspective - Chapter 1Anelya NauryzbayevaNo ratings yet

- DetournementDocument1 pageDetournementjczenkoanNo ratings yet

- Mimicry Homi BhabhaDocument10 pagesMimicry Homi BhabhaDaniela KernNo ratings yet

- D. Kadir - Postmodernism - Postcolonialism - 1995Document8 pagesD. Kadir - Postmodernism - Postcolonialism - 1995gett13No ratings yet

- Capitalist Realism - Is There No Alternat - Mark FisherDocument86 pagesCapitalist Realism - Is There No Alternat - Mark FisherIon PopescuNo ratings yet

- Aesthetic Cocoon1Document15 pagesAesthetic Cocoon1Martina MiloševićNo ratings yet

- Luis E. Carranza - Le Corbusier and The Problems of RepresentationDocument13 pagesLuis E. Carranza - Le Corbusier and The Problems of Representationchns3No ratings yet

- 6 Doomed Is A Civilization That Glorifies MatterDocument5 pages6 Doomed Is A Civilization That Glorifies MatterSPAHIC OMERNo ratings yet

- Metropolis & KafkaDocument4 pagesMetropolis & Kafkabrandon aguilarNo ratings yet

- F451 - Dystopia HandoutDocument3 pagesF451 - Dystopia HandoutAaliyah GarciaNo ratings yet

- Berghahn BooksDocument14 pagesBerghahn BooksEduardo ParreiraNo ratings yet

- African Lit - Lecture 3Document15 pagesAfrican Lit - Lecture 3tikattungusNo ratings yet

- LE CORBUSIER AND THE PROBLEM OF REPRESENTATION - Luis E. CarranzaDocument13 pagesLE CORBUSIER AND THE PROBLEM OF REPRESENTATION - Luis E. Carranzaanapaula1978No ratings yet

- HOW NEWNESS ENTERS The WORLD Postmodem Space Postcolonial Times and The Trials of Cultural Translation-BkltDocument12 pagesHOW NEWNESS ENTERS The WORLD Postmodem Space Postcolonial Times and The Trials of Cultural Translation-BkltAsis YuurNo ratings yet

- Hayles - Is Utopia ObsoleteDocument8 pagesHayles - Is Utopia ObsoletemzzionNo ratings yet

- Chapter One:: Introduction and Theoretical BackgroundDocument24 pagesChapter One:: Introduction and Theoretical BackgroundCandido SantosNo ratings yet

- Among Slave Systems A Profile of Late Roman SlaveryDocument34 pagesAmong Slave Systems A Profile of Late Roman SlaveryT.No ratings yet

- Postcolonialism and GlobalisationDocument19 pagesPostcolonialism and GlobalisationExoplasmic ReticulumNo ratings yet

- India and Post-Colonial DiscourseDocument8 pagesIndia and Post-Colonial Discourseankitabehera0770% (1)

- Alien-Nation: Zombies, Immigrants, and Millennial CapitalismDocument28 pagesAlien-Nation: Zombies, Immigrants, and Millennial CapitalismDouglas Ferreira Gadelha CampeloNo ratings yet

- 05 Hatt-Klonk PostcolonialismDocument8 pages05 Hatt-Klonk PostcolonialismStergios SourlopoulosNo ratings yet

- The Aristocratic Touch: A Look Into The Innate Urges and Inevitable Outcomes of The Upper ClassDocument15 pagesThe Aristocratic Touch: A Look Into The Innate Urges and Inevitable Outcomes of The Upper ClassPatrick Tice-CarrollNo ratings yet

- FF Belcourt Issue6Document11 pagesFF Belcourt Issue6Calibán CatrileoNo ratings yet

- Fiend of FolktalesDocument5 pagesFiend of FolktalesPriyanka KumariNo ratings yet

- Folk of Folk Horror Paper Jan 2022 PDFDocument4 pagesFolk of Folk Horror Paper Jan 2022 PDFGerardo TrinidadNo ratings yet

- Sellars Hakim BeyDocument27 pagesSellars Hakim BeyJoachim Emidio Ribeiro SilvaNo ratings yet

- Atkinson OusmaneSembneWe 1993Document7 pagesAtkinson OusmaneSembneWe 1993Khyati ParasharNo ratings yet

- Presentation EssayDocument8 pagesPresentation EssayCall Me SenpaiNo ratings yet

- London William BlakeDocument11 pagesLondon William Blakenoorttv5No ratings yet

- Capitalist Realism IntroDocument17 pagesCapitalist Realism IntroUsama AlshaibiNo ratings yet

- Marxism and OppressionDocument9 pagesMarxism and OppressionPSTordillaNo ratings yet

- Verso - Dystopian On Trial: Alice Coleman's Architectural Determinism by Robert BevanDocument5 pagesVerso - Dystopian On Trial: Alice Coleman's Architectural Determinism by Robert BevanrpmbevanNo ratings yet

- Reality: Simulations - the Analytical Audacity of Jean BaudrillardFrom EverandReality: Simulations - the Analytical Audacity of Jean BaudrillardNo ratings yet

- The Cask of AmontilladoDocument43 pagesThe Cask of AmontilladoZechaina Udo100% (2)

- NMTC Test Papers Prelims All Levels 2016Document15 pagesNMTC Test Papers Prelims All Levels 2016tannyNo ratings yet

- Integration Broker BasicsDocument6 pagesIntegration Broker Basicsharikishore14No ratings yet

- Consti CasesDocument143 pagesConsti CasesPantas DiwaNo ratings yet

- Bacarro Vs CastanoDocument2 pagesBacarro Vs CastanoMaiti LagosNo ratings yet

- Guid Line Drug TX PDFDocument707 pagesGuid Line Drug TX PDFmaezu100% (1)

- IMUNISASIDocument26 pagesIMUNISASINadia KhoiriyahNo ratings yet

- 9702 m19 Ms 12Document3 pages9702 m19 Ms 12And rewNo ratings yet

- Ghana Maketing PlanDocument11 pagesGhana Maketing PlanchiranrgNo ratings yet

- Final Nancy121Document66 pagesFinal Nancy121Sahil SethiNo ratings yet

- PERT Estimation Technique: Optimistic Pessimistic Most LikelyDocument2 pagesPERT Estimation Technique: Optimistic Pessimistic Most LikelysumilogyNo ratings yet

- "Behavioral and Experimental Economics": Written Exam For The M.Sc. in Economics 2010-IDocument4 pages"Behavioral and Experimental Economics": Written Exam For The M.Sc. in Economics 2010-ICoxorange94187No ratings yet

- Educ - MidtermDocument8 pagesEduc - MidtermAn Jannette AlmodielNo ratings yet

- Tanuj Bohra - HRM - Individual Assignment PDFDocument6 pagesTanuj Bohra - HRM - Individual Assignment PDFTanuj BohraNo ratings yet

- Project On Recruit Ment SlectionDocument6 pagesProject On Recruit Ment SlectionSunny KhushdilNo ratings yet

- Whitehead Et Al. 2009Document11 pagesWhitehead Et Al. 2009Benedikt EngelNo ratings yet

- Rune E. A. Johansson - Pali Buddhist Texts, 3ed 1981Document161 pagesRune E. A. Johansson - Pali Buddhist Texts, 3ed 1981Anders Fernstedt100% (9)

- Cricket SepepDocument7 pagesCricket Sepepapi-308918232No ratings yet

- Arema 115REDocument1 pageArema 115REAntonioNo ratings yet

- Tanjong PLC: Major Shareholder Privatising Tanjong at RM21.80/Share - 02/08/2010Document3 pagesTanjong PLC: Major Shareholder Privatising Tanjong at RM21.80/Share - 02/08/2010Rhb InvestNo ratings yet

- Carrigan 2001Document44 pagesCarrigan 2001TeodoraNo ratings yet

- Grade 3 Home Learning Animal Research ProjectDocument5 pagesGrade 3 Home Learning Animal Research Projectapi-363677682No ratings yet

- Ebook Handbook of The Psychology of Aging PDF Full Chapter PDFDocument67 pagesEbook Handbook of The Psychology of Aging PDF Full Chapter PDFforest.gertelman418100% (39)

- Math Lesson 23Document5 pagesMath Lesson 23api-461550649No ratings yet

- UE18EE325 - Unit1 - Class4 - Performance Characteristics-StaticDocument16 pagesUE18EE325 - Unit1 - Class4 - Performance Characteristics-StaticGAYATHRI DEVI BNo ratings yet

- Intro To Genetic EngineeringDocument84 pagesIntro To Genetic EngineeringMhimi ViduyaNo ratings yet

- Children's Classics in Dramatic FormBook Two by Stevenson, AugustaDocument95 pagesChildren's Classics in Dramatic FormBook Two by Stevenson, AugustaGutenberg.orgNo ratings yet

- BABOK V2 - All ChaptersDocument20 pagesBABOK V2 - All ChaptersSmith And YNo ratings yet

- Characteristics That Define Our VictoryDocument5 pagesCharacteristics That Define Our VictoryLouie BiasongNo ratings yet

- Chapter 2 - Auditing IT Governance Controls: True/FalseDocument9 pagesChapter 2 - Auditing IT Governance Controls: True/FalseShanygane Delos SantosNo ratings yet