Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Marital Rape - Violation of Fundamental Rights

Marital Rape - Violation of Fundamental Rights

Uploaded by

simranOriginal Description:

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Marital Rape - Violation of Fundamental Rights

Marital Rape - Violation of Fundamental Rights

Uploaded by

simranCopyright:

Available Formats

MARITAL RAPE: VIOLATION OF FUNDAMENTAL RIGHTS

By: Asha Antony & Anusree P .1

ABSTRACT

Rape is a heinous crime which is considered graver than murder. It is a crime of violence that

not only damages the body but which also leaves a permanent scar in the mind of the victim.

In India rape is a penal offence under S.375 and 376 of IPC. Surprisingly, it unequivocally

avoids marital rape from the ambit of conviction. Marital rape is sex by a husband with his

wife without her assent by compulsion or threat.

S.375 of IPC, mentions in its exception clause that - “Sexual intercourse by a man with his

own wife, the wife not being under 15 years of age is not rape.” The exception prima facie

violates Art.14 as it creates a classification between consent given by a married and

unmarried women. In India marriage is one of the most conventional forms of livelihood for

women where the frequency of undesired intercourse she has to give in to is in all

probabilities higher than that endured by a prostitute. The concept of marital rape goes

beyond the virtues of Article 21 i.e. right to live with human dignity. However women in

Indian setting do not make it an issue of complaint because it is against social norms and it is

considered acceptable for men to force their wives to provide sex as and when they wish. It

may be argued against marital rape as an offence that consequent to marriage between the

spouses, there lies the theory of implied consent where the husband acquires an

unquestionable right to have intercourse with his wife and it is her duty to submit before his

wishes. Though, the Indian law considers domestic violence against women as an offence but

it is mainly confined to physical harm or torture rather than the sexual abuse of wife. Marital

rape though a scar on the face of civilized society has not been criminalised in India whereas,

US and other civil western countries have criminalised them. This paper significantly focuses

on the violation of the fundamental rights guaranteed by the Constitution of India and the

status of marital rape in different countries of the world.

INTRODUCTION

The word ‘rape’ which is derived from the Latin term ‘rapio’ means ‘to seize’. Rape, in its

simplest form, signifies ‘the ravishment of a woman against her will or without her consent or

1

School of Legal Studies, CUSAT

Legal Education in Contemporary Era – 2018

ISBN: 978-93-5187-924-4

with her consent obtained by force, fear, fraud or the carnal knowledge of a woman by force

against her will.’2

The term ‘marital rape’ refers to the unwanted intercourse by a man on his wife obtained by

force, threat of force or physical violence or when she is unable to give consent. The words

‘unwanted intercourse’ refers to all sorts of penetration (whether anal, vaginal or oral)

perpetrated against her will or without her consent. According to the Indian Penal Code,

1860, rape is defined under section 375.3

According to Morton Hunt, “The typical marital rapist is a man who still believes that

husbands are supposed to “rule” their wives. This extends, he feels, to sexual matters: when he

wants her, she should be glad, or at least willing; if she isn’t, he has the right to force her. But

in forcing her he gains far more than a few minutes of sexual pleasure. He humbles her and

reasserts, in the most emotionally powerful way possible, that he is the ruler and she is the

subject.”

2

Bhupinder Sharma v .State of Himachal Pradesh ,A.I.R 2003 S.C 4684

3

[375. Rape.—A man is said to commit “rape” if he—

(a) penetrates his penis, to any extent, into the vagina, mouth, urethra or anus of a woman or

makes her to do so with him or any other person; or

(b) inserts, to any extent, any object or a part of the body, not being the penis, into the vagina, the

urethra or anus of a woman or makes her to do so with him or any other person; or

(c) manipulates any part of the body of a woman so as to cause penetration into the vagina,

urethra, anus or any part of body of such woman or makes her to do so with him or any other person;

or

(d) applies his mouth to the vagina, anus, urethra of a woman or makes her to do so with him or

any other person,

under the circumstances falling under any of the following seven descriptions:—

First. — Against her will

Secondly. — Without her consent.

Thirdly.—With her consent, when her consent has been obtained by putting her or any person in

Whom she is interested, in fear of death or of hurt.

Fourthly.—With her consent, when the man knows that he is not her husband and that her

consent is given because she believes that he is another man to whom she is or believes herself to be

Lawfully married.

Fifthly.—With her consent when, at the time of giving such consent, by reason of unsoundness of

mind or intoxication or the administration by him personally or through another of any stupefying or

unwholesome substance, she is unable to understand the nature and consequences of that to which she

Gives consent.

Sixthly.—with or without her consent, when she is under eighteen years of age.

Seventhly.—when she is unable to communicate consent.

Explanation 1.—for the purposes of this section, “vagina” shall also include labia majora.

Explanation 2.—Consent means an unequivocal voluntary agreement when the woman by words,

gestures or any form of verbal or non-verbal communication, communicates willingness to participate in

the specific sexual act:

Provided that a woman who does not physically resist to the act of penetration shall not by the reason

Only of that fact, be regarded as consenting to the sexual activity.

Exception 1.—A medical procedure or intervention shall not constitute rape.

Exception 2.—Sexual intercourse or sexual acts by a man with his own wife, the wife not being under

Fifteen years of age, is not rape.

Legal Education in Contemporary Era – 2018

ISBN: 978-93-5187-924-4

HISTORY

The concept of marital rape exception was originated from the idea that by marriage a woman

gives irrevocable consent for her husband to have sex with her at any time he demands it.

According to Sir Matthew Hale, “the husband cannot be guilty of rape committed by himself

upon his lawful wife, for by their mutual consent and contract, the wife hath given up herself

this kind unto her husband which she cannot retract.” A concept of ‘implied consent’ was

introduced by him and it established that once married, a woman does not have the right to

refuse sex with her husband. In ancient societies, American wives were considered to be the

property of their husbands, with only slightly greater rights than beasts of burden. Under the

English common law, marriage came with a meta-physical oddity, known as coverture. At

Common law, coverture was the protection and control of a woman by her husband that gave

rise to various rights and obligations. This rule stipulated that a married woman does not have

a separate legal existence from her husband and upon marriage, a woman’s legal rights were

subsumed by those of her husband. A married woman was a dependent, like an underage

child or a slave, and could not own property in her own name or control her own earnings. It

can be inferred from the coverture rule that once unified by marriage, a spouse could no

longer be charged with raping one’s spouse, any more than be charged with raping oneself.

Kirchberg v. Feenstra (1981) a U.S Supreme Court Case, which marked an end of this rule

and the court held a Louisiana Head and Master law, which gave sole control of marital

property to the husband, unconstitutional.

MARITAL RAPE LAWS IN INDIA

While in other countries either the legislature has criminalized marital rape or the judiciary

has played a crucial role in recognizing it as an offence, whereas in India Marital rape is not

an offence. In India marital rape exists de facto but not de jure. In Bodhisattwa Gautam v.

Subhra Chakraborty4 the SC held that” rape is a crime against basic human rights and a

violation of the victims” most cherished of fundamental rights, namely the right to life

enshrined in Article 21 of the Constitution. Yet it negates this very pronouncement by not

4

(1996) 1 S.C.C. 490 (India).

Legal Education in Contemporary Era – 2018

ISBN: 978-93-5187-924-4

recognizing marital rape.5 Though there have been some advances in Indian legislation in

relation to domestic violence, this has mainly been confined to physical rather than sexual

abuse.

The exception 2 of section 375 of Indian Penal Code states that non-consensual sexual

intercourse by a man with his own wife, if she is over 15 years does not amount to rape. It,

thus keeps outside the ambit of ‘ rape’ a coercive and non-consensual sexual by a ‘’husband’

with his ‘wife’ (above 15 years of age)and thereby allows a ‘husband’ to exercise, with

impunity, his marital right of (non –consensual or undesired) intercourse with his ‘wife’. It is

believed that the husband’s immunity for marital rape is premised on the assumption that a

woman, on marriage, gives forever her consent to the husband for sexual intercourse. The

husband has the right to have sexual intercourse with his wife, whether she is willing or not,

and she is under obligation to surrender or submit to his will and desire. It also aims at the

preservation of family institution by ruling out the possibility of false and fabricated and

motivated complaints of ‘rape’ by ‘wife’ against her ‘husband’ and the pragmatic procedural

difficulties that might arise in such a legal proceeding.6

Further, non- consensual sexual intercourse, in terms of the acts mentioned in sec 375 (a) to

(d), IPC by a person with his own wife who is under a decree of separation or otherwise, is

living separately is made an offence under IPC.7 The punishment provided for non-

consensual sexual intercourse by a man with his wife living separately is, however compared

to that is provided for consensual or non-consensual sexual intercourse with his own wife

when she is below the age of fifteen years of age, which, by virtue of exception 2 of section

375 of the IPC, amounts to rape, is very mild. No court is empowered to take cognizance of

the offence of sexual intercourse by husband upon his wife during separation where the

persons are in a marital relationship, except upon prima facie satisfaction of the facts which

5

Tandon, N. & Oberoi, N., Marital Rape – A Question of Redefinition, Lawyer’s Collective, March 2000, P.24.

6

Dr. K I VIBHUTE, P S A PILLAI’S CRIMINAL LAW, 723(12 TH ed. 2014).

7

376B. Sexual intercourse by husband upon his wife during separation.—Whoever has sexual

intercourse with his own wife, who is living separately, whether under a decree of separation or

otherwise, without her consent, shall be punished with imprisonment of either description for a term

which shall not be less than two years but which may extend to seven years, and shall also be liable to

Fine.

Explanation.—In this section, “sexual intercourse” shall mean any of the acts mentioned in clauses

(a) to (d) of section 375.

Legal Education in Contemporary Era – 2018

ISBN: 978-93-5187-924-4

constitute the offence upon a complaint having been filed or made by the wife against the

husband.8

The exception 2 of section 375 of IPC, 1860 violates the fundamental rights guaranteed by

the constitution of India. The concept of marital rape goes beyond the virtues of art.21 of the

constitution of India i.e. right to live with human dignity .The exception prima facie violates

art 14 of the constitution as it creates a classification between married and unmarried women

and denies the equal protection of criminal legislation to the former.

According to the UN Population fund, more than two- thirds of married women in India, aged

15 to 49 years, have been beaten or forced to provide sex. Bertrand Russell in his book

‘Marriage and Morals’ stated that marriage is one of the most conventional forms of

livelihood for a women where the frequency of undesired intercourse she has to give in to is

in all probabilities higher than that endured by a prostitute.

The concept of marital rape goes beyond the virtues of article 21 of the constitution of India

i.e. right to live with human dignity. Marital rape exception prima facie violates Article 14 of

the constitution as it creates a classification between married and unmarried women and

denies equal protection of the criminal legislation to the former.

Article 14 guarantees a fundamental right of equality before the law and equal protection of

laws to every citizen of India. In Hari Ram v State of Haryana9, it was held that equality of

citizen’s right is one of the fundamental pillars on which edifice of Rule of Law rests. All

actions of State have to be fair and for legitimate reasons. If the State leaves the existing

inequalities untouched by its laws, it fails in its duty of providing equal protection its laws to

all persons.10 Every person is entitled to equality before law and the equal protection of laws

where the State is bound to protect every human being from inequality11. Parliament and

State Legislature cannot transgress the principle of equality enshrined in Article 14 which is

the basic structure of the Constitution.12 Doctrine of equality enshrined in Article 14 of the

Constitution which is the basis of Rule of Law is the basic feature of Constitution.13. Article

14 forbids class legislations, but doesn’t forbid reasonable classification. But classification

must not be “arbitrary, artificial or evasive”. It must always rest upon some real and

8

Dr. K I VIBHUTE, P S A PILLAI’S CRIMINAL LAW, 724(12 TH ed. 2014).

9

(2010) 3 S.C.C. 621

10

St. Stephen’s College v. University of Delhi, (1992) 1 S.C.C. 558

11

National Human Rights Commission v.State of Arunachal Pradesh, AIR 1996 S.C 1234

12

IndraSawhney v. Union of India, AIR 2000 SC 498

13

Raghunath Rao Ganapath Rao v Union of India , AIR 1993 S.C 1267

Legal Education in Contemporary Era – 2018

ISBN: 978-93-5187-924-4

substantial distinction bearing a just and reasonable relation to the object sought to be

achieved by the legislation. Classification to be reasonable must fulfil the following two

conditions-

(a) The classification must be founded on an intelligible differentia which distinguishes those

that are grouped together from others; and

(b) The differentia must have a rational relation to the object sought to be achieved by the

legislation14.

Thus any law which makes a classification which is unreasonable or irrelevant to the

purposes of the legislation is deemed to be outside the framework of the Constitution. It is

essential to prevent the stereotyping based on gender in order to curtail the gender biased

differential treatment. Therefore it is important when applying the test of equality that care be

taken so that the stereotyping enjoined by the patriarchal ideology does not predetermine

what is reasonable classification.

Section 375 of the IPC criminalises the offence of rape and protects a woman against forceful

sexual intercourse against her will and without her consent. Thereby the section grants

protection to women against criminal assaults on the bodily autonomy and depicts the State’s

interest in prosecuting those who violate this bodily autonomy. Therefore it is right to say that

Section 375 of the IPC seeks to protect the woman’s right of choice as autonomous individual

also capable of self-expression and also regards rape as a crime of violence which disregards

all such rights granted to the individual. However, Section 375 of the IPC makes a

classification in terms of an exemption that does not regard a forceful sexual intercourse

within a marriage as rape. The exemption withdraws the protection of Section 375 of the IPC

from a married woman on the basis of her marital status. The classification and differential

treatment of married women rests on the assumption that married women, unlike any other

persons, have no interest in receiving protection from the State against violent and sexual

assault. The assumption further stems from the fact that in a marriage, the wife is presumed to

have given an irrevocable consent to sexual relationships with her husband.

Married women, exactly like men and unmarried women need protection of the law in their

private spheres. While the rest of the section 375 of the IPC is interested in protecting the

right of a victim from the crime of rape, such a right is withdrawn on marriage and the focus

14

State of West Bengal v. Anwar Ali Sarkar, AIR 1952 S.C 75

Legal Education in Contemporary Era – 2018

ISBN: 978-93-5187-924-4

of the law instead shifts to protecting, the perpetrator of the crime of rape. It takes away a

woman’s right of choice and indeed effectively deprives her of bodily autonomy and her

personhood. Thus the classification is unreasonable, unintelligible and violates the mandate

of Article 14. Withdrawing the protection of Section 375 of the IPC from the victims of the

crime of rape solely on the basis of their marital status is irrelevant for the purposes of

legislation and thus violates the test of classification under Article 14. The Criminal Law

(Amendment) Act, 2013 increased the age of consent for sexual intercourse by a girl from 16

years to 18 years. By virtue of provisions of Protection of Children from Sexual Offences

Act, 2012, Parliament has recognized that a girl less than 18 years is a child and therefore, not

in a physical and mental condition to take an informed decision as to sexual relationship.

However, Exception 2 to Section 375 IPC still retains the age of consent from a married girl

as 15 years. As a result, there is a huge gap of 3 years in the age of consent for a married girl

child, vis-a-vis an unmarried girl child.15

This classification has no rationale nexus with the object sought to be achieved, it submits.

The rationale for increasing the age of consent to 18 years is that a girl below the age of 18

years is considered incapable of realizing the consequences of her consent; She is treated as a

minor under law and, therefore, mentally and physically not mature enough to give a valid

consent.

Therefore, simply because some marriages in India are being performed at an age lower than

18 years, it is not a justification to lower the age of consent to as low as 15 years. Parliament

cannot permit the exploitation [in the name of marriage] of a girl child simply because some

girls are married at an age less than 18 years.”16

Article 21 of the Indian constitution enshrines in it the right to life and personal liberty.

Article 21 although couched in negative language confers on all persons the fundamental

right to life and personal liberty. Post the case of Maneka Gandhi v Union of India it has

become the source of all forms of right aimed at protection of human life and liberty. The

meaning of the term ‘life’ has thus expanded and can be appropriately summed up in the

words of Field J. in Munn v Illinois where he held that life means ‘something more than a

mere animal existence’, which was further in Bandhua Mukthi Morcha v. Union of India

where the SC affirmed that right to live with human dignity.

15

Independent Thought v. Union of India. 2013

16

Independent thought v. Union of India ,2013

Legal Education in Contemporary Era – 2018

ISBN: 978-93-5187-924-4

In light of this expanding jurisprudence of article 21, the doctrine of marital exemption to

rape violates a host of rights that have emerged from the expression ‘right to life and personal

liberty’ under Article 21 .The marital exemption to rape the right to privacy, right to bodily

self-determination and the right to good health, all of which have been recognized as an

integral part of the right to life and personal liberty at various points of time.

The concept of right to life under article 21 of the constitution includes the right to live with

human dignity and all that goes along with it. The right to live with human dignity is one of

the most inherent qualities of the right to life which recognizes the autonomy of an

individual. The SC has held in a catena of cases that the offence of rape violates the right to

life and the right to live with human dignity of the victim of the crime of rape, that it is not

merely an offence under the IPC, but is a crime against the entire society. Rape is less of a

sexual offence than an act of aggression aimed at degrading and humiliating the women.

Thus the marital exemption doctrine is also vocative of a woman’s right to live with human

dignity. Any law which legitimizes the right of a husband to compel the wife into having

sexual intercourse against her will and without her consent goes against the very essence of

right to life under article 21.

Though the constitution does not expressly recognise the right of bodily self-determination,

such a right exists in the larger framework of the right to life and personal liberty under

article 21. The right of self-determination is based on belief that the individual is the ultimate

decision maker in matters closely associated with his/her body or well-being and the more

intimate the choice, the more robust is the right of the individuals to be the authors of their

own fate. Consent to sex is one of the most intimate and personal choice that a women

reserves from herself. It is a form of self-expression and self-determination and a law that

makes away the right of expressing and revoking such consent definitely deprives a person

the constitutional right of bodily self-determination.

The marital rape exemption violates the right to good health of the victim of such a crime.

The right to good health has been recognised as a part of the right to life under the article 21.

Such a right is necessary for the continuous intellectual and spiritual well-being of a person.

The marital exemption doctrine violates to right to good health of a victim as it inevitably

cause serious psychological as well as physical harm in the process. It destroys the

psychology of a women and pushes her into a deep emotional crisis. A more compelling

argument can be made in case where forceful sexual intercourse in a marriage leads to the

Legal Education in Contemporary Era – 2018

ISBN: 978-93-5187-924-4

communication of a sexually transmitted disease to the victim of a crime of rape. The marital

exception effectively deprives a married women of her right to good health.

In a series of cases the SC has recognized that a right to privacy is constitutionally protected

under Article 21 of the Indian Constitution. Justice K.S Puttaswamy and Anr. v. Union of

India and Ors is a landmark judgment of the Supreme Court of India, which holds that the

right to privacy is protected as a fundamental constitutional right under Articles 14, 19 and 21

of the Constitution of India.17 The right to privacy under Article 21 includes a right to be left

alone. Any form of forceful sexual intercourse violates the right of privacy. The exemption to

marital rape violates a married woman’s right to privacy by forcing her to enter into a sexual

relation against her wish. The Supreme Court in the case of State of Maharashtra v.

Madhukar Narayan18 has held that every woman was entitled to sexual privacy and it was not

open for any person to violate her privacy as an when he wished or pleased. In the case of

Vishaka v State of Rajasthan19 , the Supreme Court extended this right to privacy in

workplaces. Further, along the same line, there exists a right to privacy to enter into a sexual

relationship even within a marriage. By decriminalizing rape within a marriage, the marital

rape exemption violates the right to privacy of a married women.

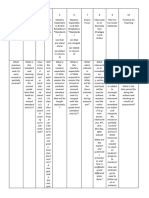

LEGAL POSITION IN OTHER COUNTRIES

In United States marital rape was considered as a crime since 1993. A minority of the States

have abolished the marital rape exemption in its entirety, and that it remains in some proportion

or other in all the rest. In most American States, resistance requirements still apply. In

seventeen States and also in the District of Columbia, there are no exemptions from rape

prosecution which is granted to husbands. However, in the rest thirty-three American States,

there are still some exemptions to rape given to husbands which are: When his wife is most

vulnerable and is legally unable to consent, a husband is exempted from prosecution in many

of these thirty-three States. The existence of some spousal exemptions in the majority of the

American States indicates that rape in marriage is still treated as a lesser crime when compared

to other forms of rape. The existence of any spousal exemption indicates an acceptance of the

17

Bhandari, Vrinda; Kak, Amba; Parsheera, Smriti; Rahman,Fiza.” An analysis of Puttaswamy :The Supreme

Court’s Privacy Verdict “

18

A.I.R 1991 S.C 207

19

A.I.R. 1997 S.C. 3011

Legal Education in Contemporary Era – 2018

ISBN: 978-93-5187-924-4

bygone understanding that wives are the property of their husbands and the marriage contract

is entitlement to sex.

In England, earlier as a general rule, a man could not have been held to be guilty as a principal

of rape upon his wife, for the wife in general is not able to retract to the consent for sexual

intercourse, which is a major part of the contract of marriage. However, the marital rape

exemption was abolished in its entirety in the year 1991. The House of Lords in R. v. R held

that the rule which says a husband cannot be held guilty of raping his wife if he forced her to

have sexual intercourse against her will was an misdated and offensive common-law fiction,

which no longer represented the position of a wife in present-day society, and that it should no

longer be applied.

In Mexico, the country’s Congress ratified a bill that makes domestic violence punishable by

law. If convicted, marital rapists could be imprisoned for 16 years.

In Sri Lanka, the recent amendments to the Penal Code recognize marital rape, but only with

regard to the partners who are judicially separated, and there exists a great reluctance to pass

judgment on rape in the context of partners who are actually living together. However, some

countries have started to legislate against the offence of marital rape, refusing to accept the

marital relationship as a cover for violence in home.

Today there are many States that have either enacted marital rape laws, repealed marital rape

exceptions or have laws that do not distinguish between marital rape and ordinary rape. These

States include Albania, Algeria, Australia, Belgium, Canada, China, Denmark, France,

Germany, Hong Kong, Ireland, Italy, Japan, Mauritania, New Zealand, Norway, the

Philippines, Scotland, South Africa, Sweden, Taiwan, Tunisia, the United Kingdom, the

United States, and recently, Indonesia. Turkey criminalized marital rape in 2005, Mauritius

and Thailand did so in 2007. The criminalization of marital rape in these countries both in

Asia and around the world indicates that marital rape is now recognized as a violation of

human rights. In 2006, it was estimated that marital rape is an offence punished under the

criminal law in at least 100 countries and India is not one among them. Even though marital

rape is prevalent in India, it is hidden behind the sacrosanct curtains of marriage.

CONCLUSION

Rape is a brutal offence which is worse than a cold blooded murder. It is an assassination of a

woman’s dignity. She should not be considered as a property of the husband to do as he

please.

Legal Education in Contemporary Era – 2018

ISBN: 978-93-5187-924-4

It is immaterial whether a woman is raped by her husband or by a complete stranger. Though

marital rape is the most common and repugnant form of masochism in the Indian society, it is

well hidden behind the iron curtain of marriage. The concept of marital rape violates Article

14 and 21 of the Constitution of India, i.e. the right to equality and right to life and personal

liberty. When a woman gets married she does not waive her rights as an individual, nor does

she become a second class citizen. Further, she should not be denied the protection of law and

be submitted to the defiling of her body by her husband. When a woman is being forced to

submit herself to the whims of her husband, she is being denied the right to self-

determination and sexual autonomy. The basic difference between rape and consensual sex is

whether the woman consented to the act itself. When a man forces himself on a woman,

irrespective of the relationship they share, the lack of consent from the woman should be

given due weightage and the act must be seen for the offence it is.

Legal Education in Contemporary Era – 2018

ISBN: 978-93-5187-924-4

You might also like

- Marital Rape PresentationDocument18 pagesMarital Rape PresentationGAURAV TRIPATHINo ratings yet

- Karl Marx Mill, J.S., The Subjection of Womened. S.M. Okin, Indianapolis, Hacket, 1988, P. 33Document19 pagesKarl Marx Mill, J.S., The Subjection of Womened. S.M. Okin, Indianapolis, Hacket, 1988, P. 33BhanuNo ratings yet

- Marital Rapes in India: Women and Law:PSDADocument8 pagesMarital Rapes in India: Women and Law:PSDADhruv TyagiNo ratings yet

- Marital RapeDocument4 pagesMarital RapeRitisha ChoudharyNo ratings yet

- Efects of Marital RapeDocument9 pagesEfects of Marital RapeAsthaNo ratings yet

- Dr. Ram Manoha University, Lucknow Dr. Ram Manohar Lohiya National Law University, Lucknow R Lohiya National LawDocument12 pagesDr. Ram Manoha University, Lucknow Dr. Ram Manohar Lohiya National Law University, Lucknow R Lohiya National LawNishkam SinghNo ratings yet

- IndexDocument10 pagesIndexAkanshaNo ratings yet

- Women and Law Marital RapeDocument18 pagesWomen and Law Marital Rapenisha thakurNo ratings yet

- Marital Rape in IndiaDocument4 pagesMarital Rape in IndiaYuktaNo ratings yet

- Marital Rape - A Conitnued DenialDocument5 pagesMarital Rape - A Conitnued DenialJanvi PatidarNo ratings yet

- Marital Rape - It'S High Time NowDocument6 pagesMarital Rape - It'S High Time NowPrakhar DixitNo ratings yet

- Developmental LawyeringDocument6 pagesDevelopmental LawyeringSHWETA MENONNo ratings yet

- The Scandalous Persecution of The Sexual Autonomy of Indian WomenDocument8 pagesThe Scandalous Persecution of The Sexual Autonomy of Indian WomenNaman MishraNo ratings yet

- Chandigarh University Ballb - 4 SEM Research Paper On Marital PaperDocument19 pagesChandigarh University Ballb - 4 SEM Research Paper On Marital Papervaishali thakurNo ratings yet

- Marital Rape by RimaDocument7 pagesMarital Rape by RimaRimz HarrzNo ratings yet

- Research Paper Offences Related To Rape: National University OF Study AND Research IN Law, RanchiDocument11 pagesResearch Paper Offences Related To Rape: National University OF Study AND Research IN Law, RanchiRam Kumar YadavNo ratings yet

- Criminalizing Marital Rape in India: Indian Penal CodeDocument10 pagesCriminalizing Marital Rape in India: Indian Penal CodeParyushi KoshalNo ratings yet

- UK Jud Academy MRapeDocument6 pagesUK Jud Academy MRapeHitesh SharmaNo ratings yet

- Crime PaperDocument15 pagesCrime Paperyukta ambasthaNo ratings yet

- Rape: MeaningDocument12 pagesRape: MeaningAashish RathoreNo ratings yet

- Full PaperDocument8 pagesFull PaperATUL KUMAR DUBEYNo ratings yet

- Rape-R PDocument14 pagesRape-R PPrerna KaushikNo ratings yet

- (2024+issue) +ARDA JOURNAL 17174++ - +AL+Document5 pages(2024+issue) +ARDA JOURNAL 17174++ - +AL+Sajid RahmanNo ratings yet

- Marital RapeDocument5 pagesMarital RapeAdwait KolwalkarNo ratings yet

- Criminalisation of Marital Rape in IndiaDocument4 pagesCriminalisation of Marital Rape in IndiaShalini DwivediNo ratings yet

- Ipc Project 6th SemDocument13 pagesIpc Project 6th SemsahilNo ratings yet

- Nimisha Pal Marital RapeDocument14 pagesNimisha Pal Marital RapeSaurabh KumarNo ratings yet

- Marital Rape and Violation of Constitutional ProvisionsDocument6 pagesMarital Rape and Violation of Constitutional ProvisionsAdvikaNo ratings yet

- Liscence To Rape ? Oh Well !! Society Calls It MarriageDocument9 pagesLiscence To Rape ? Oh Well !! Society Calls It MarriageShourya KulshresthaNo ratings yet

- Marital RapeDocument17 pagesMarital RapeKumar NaveenNo ratings yet

- Adultery General DefinitionDocument3 pagesAdultery General DefinitionishratNo ratings yet

- Legal Academic WritingDocument9 pagesLegal Academic WritingParul MeenaNo ratings yet

- People Vs Jumawan RapeDocument57 pagesPeople Vs Jumawan RapeKanraMendozaNo ratings yet

- Gender Justice and FeminismDocument7 pagesGender Justice and FeminismAnirudhaRudhraNo ratings yet

- IPC Sample 2 PDFDocument18 pagesIPC Sample 2 PDFSachin HoodaNo ratings yet

- Fariya and Siddharth Marital Rape PaperDocument3 pagesFariya and Siddharth Marital Rape PaperSiddharth AnandNo ratings yet

- The Criminalization of Marital Rape in India - A Distant DreamDocument12 pagesThe Criminalization of Marital Rape in India - A Distant DreamGlobal Research and Development ServicesNo ratings yet

- ipc-II Assignment by AnveshaDocument16 pagesipc-II Assignment by AnveshaAnvesha ChaturvdiNo ratings yet

- 1 Intl JLMGMT Human 44Document8 pages1 Intl JLMGMT Human 44ishitaNo ratings yet

- Marital Rape An Undefined CrimeDocument8 pagesMarital Rape An Undefined CrimeAnusuyaNo ratings yet

- Marital Rape - A Crime Against WomenDocument12 pagesMarital Rape - A Crime Against WomenShayan ZafarNo ratings yet

- Updated Legalisation of Maritial RapeDocument13 pagesUpdated Legalisation of Maritial RapedeveshNo ratings yet

- Assignment On Marital Rape As A Ground For Divorce: Submitted ToDocument18 pagesAssignment On Marital Rape As A Ground For Divorce: Submitted ToAishwarya MathewNo ratings yet

- Criminalization of Marital RapeDocument6 pagesCriminalization of Marital RapeAnuj Singh RaghuvanshiNo ratings yet

- AssignmentDocument16 pagesAssignmentpriyanshu yadavNo ratings yet

- Marital Rape A Crime Not CriminalizedDocument7 pagesMarital Rape A Crime Not CriminalizedShubhamSinghNo ratings yet

- Marital Rape As A Ground For DivorceDocument5 pagesMarital Rape As A Ground For DivorceIshan JhaNo ratings yet

- Family Law ProjectDocument14 pagesFamily Law ProjectPriya Sewlani67% (3)

- Women and Law Article ReviewDocument5 pagesWomen and Law Article Reviewnikhil saiNo ratings yet

- Marital Rape - When Rape Is Not A CrimeDocument21 pagesMarital Rape - When Rape Is Not A Crimeshubhangi sharmaNo ratings yet

- Adultery Law in India: A CritqueDocument3 pagesAdultery Law in India: A CritqueRunal BhanamgiNo ratings yet

- Law and MoralityDocument21 pagesLaw and MoralityShashank PandeyNo ratings yet

- Marital Rape Case of StalemateDocument13 pagesMarital Rape Case of StalemateYogesh AnandNo ratings yet

- Evolution of Anti Rape Laws in India Since IndependenceDocument9 pagesEvolution of Anti Rape Laws in India Since IndependenceJinal MistryNo ratings yet

- Consensual Sexual Intercourse On False Pretext of Marriage If Rape: A Socio - Legal StudyDocument7 pagesConsensual Sexual Intercourse On False Pretext of Marriage If Rape: A Socio - Legal StudyKavita DeviNo ratings yet

- IPC Project, 6th TrimesterDocument16 pagesIPC Project, 6th TrimesterAkshay SarjanNo ratings yet

- Rape: MeaningDocument15 pagesRape: MeaningtrishaNo ratings yet

- Case Law FinalDocument14 pagesCase Law FinalsimranNo ratings yet

- Case Law 2nd SemDocument17 pagesCase Law 2nd SemsimranNo ratings yet

- 2 - TreatiesDocument18 pages2 - TreatiessimranNo ratings yet

- 1 - Concept of SourcesDocument24 pages1 - Concept of SourcessimranNo ratings yet

- A N M C C, 2018 T C: Mity Ational OOT Ourt OmpetitionDocument48 pagesA N M C C, 2018 T C: Mity Ational OOT Ourt OmpetitionsimranNo ratings yet

- 2 - TreatiesDocument18 pages2 - TreatiessimranNo ratings yet

- Case LawDocument22 pagesCase LawsimranNo ratings yet

- The XXVI BPW International Congerss ProceedingDocument123 pagesThe XXVI BPW International Congerss Proceedinganon_863652862No ratings yet

- Uts - Political SelfDocument23 pagesUts - Political SelfCassia ィNo ratings yet

- 11 EnlightenmentDocument52 pages11 Enlightenmentjacksm3No ratings yet

- COMELEC Vs Hon. Thelma CanlasDocument1 pageCOMELEC Vs Hon. Thelma CanlasClint D. LumberioNo ratings yet

- The Globe and Mail 2019-10-22 PDFDocument48 pagesThe Globe and Mail 2019-10-22 PDFParfait IshNo ratings yet

- Great Men and WomenDocument25 pagesGreat Men and Womenrotsacrejav31No ratings yet

- Primicias v. Ocampo, G.R. No. L-6120, June 30, 1953.full TextDocument6 pagesPrimicias v. Ocampo, G.R. No. L-6120, June 30, 1953.full TextRyuzaki HidekiNo ratings yet

- Fandry and Sairat AnalysisDocument2 pagesFandry and Sairat AnalysisRachit KumarNo ratings yet

- Quiz 3Document2 pagesQuiz 3ivejdNo ratings yet

- Ethnicity of The Ancient MacedoniansDocument6 pagesEthnicity of The Ancient Macedonianspelister makedonNo ratings yet

- SLRPDocument6 pagesSLRPPhoebe DaisogNo ratings yet

- Research ProposalDocument5 pagesResearch Proposalapi-311261133No ratings yet

- Refany Meiarlan Fadhli Xipa2: Components What You Write Write Your Draft Here OrientationDocument2 pagesRefany Meiarlan Fadhli Xipa2: Components What You Write Write Your Draft Here OrientationRefany meiarlanNo ratings yet

- Polsc Flowchart Power Sharing 3 231217 152443Document3 pagesPolsc Flowchart Power Sharing 3 231217 152443hishantkumar2009No ratings yet

- 5th UnitDocument30 pages5th UnitrannnbirrrNo ratings yet

- 6026 Krithika JayadasanDocument28 pages6026 Krithika JayadasanMR GODFATHER ZZNo ratings yet

- Cynthia Case 1 - Collective BargDocument5 pagesCynthia Case 1 - Collective BargCynthiaNo ratings yet

- LEA 4 ComparativeDocument196 pagesLEA 4 ComparativeJoy Estela MangayaNo ratings yet

- San Diego and Tijuana Sewage Pollution Problems and Policy's SolutionsDocument6 pagesSan Diego and Tijuana Sewage Pollution Problems and Policy's SolutionsAssignmentLab.comNo ratings yet

- We Vote Because We CareDocument1 pageWe Vote Because We CareShefferd BernalesNo ratings yet

- Alma Ata DeclarationDocument20 pagesAlma Ata DeclarationGloriaCoronado50% (2)

- ANGELITA SIMUNDAC vs. KeppelDocument1 pageANGELITA SIMUNDAC vs. KeppelGLORILYN MONTEJO0% (1)

- NLG 2014 Convention CLE Materials Vol IIIDocument1,224 pagesNLG 2014 Convention CLE Materials Vol IIILukaNo ratings yet

- The Caveman and The Bomb - Does Trump Grasp The Horror of His Threat To - Totally Destroy - North KoreaDocument6 pagesThe Caveman and The Bomb - Does Trump Grasp The Horror of His Threat To - Totally Destroy - North KoreaBruna RodriguesNo ratings yet

- 8 Rgnul N M C C, 2019: Ational OOT Ourt OmpetitionDocument2 pages8 Rgnul N M C C, 2019: Ational OOT Ourt OmpetitionMudit GuptaNo ratings yet

- UCSP Chapter 1 SlidesDocument18 pagesUCSP Chapter 1 SlidesKyle Darren PunzalanNo ratings yet

- Tata Tea - Jaago Re!Document19 pagesTata Tea - Jaago Re!Siddhesh MaralNo ratings yet

- United States Court of Appeals, Second Circuit.: No. 237, Docket 83-2162Document8 pagesUnited States Court of Appeals, Second Circuit.: No. 237, Docket 83-2162Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Attack Spectrum and CountermeasuresDocument12 pagesAttack Spectrum and CountermeasuresskjvdnskdjNo ratings yet

- Caunca V SalazarDocument9 pagesCaunca V SalazarCJ VillaluzNo ratings yet