Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Classification and Pathological Anatomy: Anal Abscess and Fistula

Classification and Pathological Anatomy: Anal Abscess and Fistula

Uploaded by

azizaaharisCopyright:

Available Formats

You might also like

- PDF Adhd in The Schools Assessment and Intervention Strategies Dupaul Ebook Full ChapterDocument53 pagesPDF Adhd in The Schools Assessment and Intervention Strategies Dupaul Ebook Full Chapteranne.wood454100% (6)

- FdarDocument2 pagesFdarkasandra dawn Beriso67% (3)

- DLP Communicable DiseasesDocument10 pagesDLP Communicable DiseasesPlacida Mequiabas National High SchoolNo ratings yet

- Management of Anal FistulaDocument5 pagesManagement of Anal Fistulailham adhaniNo ratings yet

- A No Rectal AbscessDocument12 pagesA No Rectal AbscesswawdeniseNo ratings yet

- Anal Fistula Dont DeleteDocument28 pagesAnal Fistula Dont DeleteRazeen RiyasatNo ratings yet

- Anal FistulasDocument9 pagesAnal FistulasikeernawatiNo ratings yet

- Anal FistulaDocument2 pagesAnal FistulayayassssssNo ratings yet

- 2 GYNE 1a - Benign Lesions of The Vagina, Cervix and UterusDocument11 pages2 GYNE 1a - Benign Lesions of The Vagina, Cervix and UterusIrene FranzNo ratings yet

- Anal FistulaDocument7 pagesAnal FistulaKate Laxamana Guina100% (1)

- Symptoms: Anal Fistula, or Fistula-In-Ano, Is An Abnormal Connection Between TheDocument5 pagesSymptoms: Anal Fistula, or Fistula-In-Ano, Is An Abnormal Connection Between ThePandu Nugroho KantaNo ratings yet

- Tinjauan Pustaka Fistula PerianalDocument3 pagesTinjauan Pustaka Fistula PerianalAde Perdana SetiawanNo ratings yet

- Fistula PerianalDocument25 pagesFistula PerianalHafiizh Dwi PramuditoNo ratings yet

- Anorectal Abscess - Background, Anatomy, PathophysiologyDocument9 pagesAnorectal Abscess - Background, Anatomy, Pathophysiology송란다No ratings yet

- Translabprevention CSFJCGPRLDocument5 pagesTranslabprevention CSFJCGPRLJohn GoddardNo ratings yet

- Whiteford2007 Abses PerianalDocument8 pagesWhiteford2007 Abses PerianalPudyo KriswhardaniNo ratings yet

- Anorectal Surgery PDFDocument33 pagesAnorectal Surgery PDFLuminitaDumitriuNo ratings yet

- Art 20195764Document3 pagesArt 20195764Clarence Glenn JocsonNo ratings yet

- Complex Fistulas in Ano: Seton Placement An Effective Solution To Tricky Enigma ShortDocument6 pagesComplex Fistulas in Ano: Seton Placement An Effective Solution To Tricky Enigma ShortIJAR JOURNALNo ratings yet

- Four Cases of Preauricular Fistula Based On Systematic Review Resulted New AlgorithmDocument10 pagesFour Cases of Preauricular Fistula Based On Systematic Review Resulted New AlgorithmMuhammad Dody HermawanNo ratings yet

- Fistula in AnoDocument4 pagesFistula in AnoosamabinziaNo ratings yet

- Operative Management of Anorectal FistulasDocument19 pagesOperative Management of Anorectal Fistulasdim firmNo ratings yet

- Procedure ON: EpisiotomyDocument7 pagesProcedure ON: EpisiotomyShalabh JoharyNo ratings yet

- Anorectal Abscess: Principles of Internal Medicine, 18E. New York, Ny: Mcgraw-Hill 2012Document7 pagesAnorectal Abscess: Principles of Internal Medicine, 18E. New York, Ny: Mcgraw-Hill 2012Irene SohNo ratings yet

- Appendiktomi Translate BookDocument19 pagesAppendiktomi Translate Bookalyntya melatiNo ratings yet

- Fsurg 07 559443Document9 pagesFsurg 07 559443johana.solerNo ratings yet

- Stricture Urethra PDFDocument12 pagesStricture Urethra PDFNasti YL HardiansyahNo ratings yet

- Anal Abscess and FistulaDocument12 pagesAnal Abscess and FistulaGustavoZapataNo ratings yet

- Bulbar Urethroplasty Using The Dorsal Approach: Current TechniquesDocument7 pagesBulbar Urethroplasty Using The Dorsal Approach: Current TechniquesFitrah TulijalrezyaNo ratings yet

- Anal Fistula New TechniqueDocument7 pagesAnal Fistula New TechniqueSuhenri SiahaanNo ratings yet

- Fistula-In-Ano Extending To The ThighDocument5 pagesFistula-In-Ano Extending To The Thightarmohamed.muradNo ratings yet

- FORESKIN ANOPLASTY Freeman1984Document5 pagesFORESKIN ANOPLASTY Freeman1984Joaquin Martinez HernandezNo ratings yet

- TECNICADocument7 pagesTECNICASiris Rieder GarridoNo ratings yet

- German S3 Guidelines: Anal Abscess and Fistula (Second Revised Version)Document55 pagesGerman S3 Guidelines: Anal Abscess and Fistula (Second Revised Version)Bunga AmiliaNo ratings yet

- Absceso y Fistula AnalDocument24 pagesAbsceso y Fistula AnalSinue PumaNo ratings yet

- Advances: Management of Fistula in Ano - RecentDocument76 pagesAdvances: Management of Fistula in Ano - Recentyoga_kusmawanNo ratings yet

- Submental Intubation in Patients With Complex Maxillofacial InjuriesDocument4 pagesSubmental Intubation in Patients With Complex Maxillofacial InjuriesMudassar SattarNo ratings yet

- Akira, 2022Document6 pagesAkira, 2022Ahmed SalahNo ratings yet

- A Tour ofDocument10 pagesA Tour ofChaimae OuafikNo ratings yet

- Session 5-Anorectal FistulaDocument34 pagesSession 5-Anorectal FistulanshabimussakolleNo ratings yet

- Perianal AbscessFistula DiseaseDocument9 pagesPerianal AbscessFistula Diseasetri jayaningratNo ratings yet

- Layers of Abdominal Wall When Performing An AppendicectomyDocument2 pagesLayers of Abdominal Wall When Performing An AppendicectomydrsamnNo ratings yet

- Guidelines For The Multidisciplinary Management of Crohn's Perianal Fistulas: Summary StatementDocument8 pagesGuidelines For The Multidisciplinary Management of Crohn's Perianal Fistulas: Summary StatementdeviNo ratings yet

- 4Y7zAw Ccrs23149Document12 pages4Y7zAw Ccrs23149Jefry JapNo ratings yet

- Aetiology, Pathology and Management of Enterocutaneous FistulaDocument34 pagesAetiology, Pathology and Management of Enterocutaneous Fistulabashiruaminu100% (4)

- Jurnal tht7Document5 pagesJurnal tht7Tri RominiNo ratings yet

- Anal FistulaDocument6 pagesAnal Fistulaalaixmunakamala100% (1)

- York Mason Procedure PDFDocument12 pagesYork Mason Procedure PDFMohammed Mustafa ShaatNo ratings yet

- Journal 2015Document3 pagesJournal 2015Rakha Sulthan SalimNo ratings yet

- Abcess PeritonsillarDocument21 pagesAbcess PeritonsillarribeetleNo ratings yet

- Genital Tract InjuriesDocument24 pagesGenital Tract InjuriesManisha ThakurNo ratings yet

- Wiitm 7 17104 PDFDocument4 pagesWiitm 7 17104 PDFZam HusNo ratings yet

- CANALPLASTYDocument7 pagesCANALPLASTYluar3003No ratings yet

- Atlas of Vesicovaginal FistulaDocument7 pagesAtlas of Vesicovaginal FistulaYodi SoebadiNo ratings yet

- Rupture UterusDocument23 pagesRupture Uterushacker ammerNo ratings yet

- The Most Common Hernia in Females IsDocument22 pagesThe Most Common Hernia in Females IsNessreen JamalNo ratings yet

- Anterior Sagittal Approach and Total Urogenital Mobilization For The Treatment of Persistent Urogenital SinusDocument4 pagesAnterior Sagittal Approach and Total Urogenital Mobilization For The Treatment of Persistent Urogenital SinusGunduz AgaNo ratings yet

- Fistula in AnoDocument21 pagesFistula in AnoHannah LeiNo ratings yet

- Lateral Internal Sphincterotomy For Chronic Idiopathic Anal Fissure - An Alterative ApproachDocument5 pagesLateral Internal Sphincterotomy For Chronic Idiopathic Anal Fissure - An Alterative ApproachNicolás CopaniNo ratings yet

- Article Thyroglose 1Document2 pagesArticle Thyroglose 1Jessica Paulina Salazar RuizNo ratings yet

- Endoscopic Ultrasound Management of Pancreatic Lesions: From Diagnosis to TherapyFrom EverandEndoscopic Ultrasound Management of Pancreatic Lesions: From Diagnosis to TherapyAntonio FacciorussoNo ratings yet

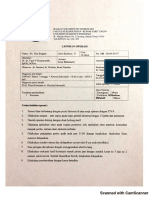

- Tatalaksana Ketergantungan StimulantDocument2 pagesTatalaksana Ketergantungan StimulantazizaaharisNo ratings yet

- Gluteal Abscess: An Unusual Complication of Bacille Calmette-GuérinDocument1 pageGluteal Abscess: An Unusual Complication of Bacille Calmette-GuérinazizaaharisNo ratings yet

- 27 Testicular PainDocument2 pages27 Testicular PainazizaaharisNo ratings yet

- Laporan Ok ObsgynDocument24 pagesLaporan Ok ObsgynazizaaharisNo ratings yet

- Kangaroo Mother CareDocument8 pagesKangaroo Mother CareSanthosh.S.UNo ratings yet

- Drugs AddictionDocument25 pagesDrugs AddictionReader67% (3)

- Accident and Incident Report ProcedureDocument23 pagesAccident and Incident Report ProcedureWakarusa Co100% (1)

- CHSSDocument8 pagesCHSSsariyu143No ratings yet

- Mammography Sas 10Document11 pagesMammography Sas 10faith mari madrilejosNo ratings yet

- Research Paper On Expert System PDFDocument4 pagesResearch Paper On Expert System PDFgz7vxzyz100% (1)

- How Social Media Impacts The Mental Health of Grade 10 Junior High School StudentsDocument2 pagesHow Social Media Impacts The Mental Health of Grade 10 Junior High School StudentsRegor Salvador ArboNo ratings yet

- School Based ImmunizationDocument28 pagesSchool Based ImmunizationDarell Paguel Permato70% (10)

- 1st Sem Sport Science Assignment ContentDocument9 pages1st Sem Sport Science Assignment ContentKobasen LimNo ratings yet

- Occupational Health ObjectivesDocument1 pageOccupational Health Objectivesbook1manNo ratings yet

- Parent-Teen Talk Facilitator's Guide - LexcodeDocument135 pagesParent-Teen Talk Facilitator's Guide - LexcodeRochelle AdlaoNo ratings yet

- Scope and DelimitationDocument8 pagesScope and DelimitationLiza MarigondonNo ratings yet

- Unit I - Introduction-to-Midwifery-Obstetrical-NursingDocument43 pagesUnit I - Introduction-to-Midwifery-Obstetrical-NursingN. Siva100% (9)

- Community Health NutritionDocument31 pagesCommunity Health NutritionJosephNo ratings yet

- Characteristics of Community HealthDocument2 pagesCharacteristics of Community HealthRichard Balili100% (1)

- CONCLUSIONDocument2 pagesCONCLUSIONÑàgùr BåshaNo ratings yet

- Tamizaje Ca de PulmonDocument11 pagesTamizaje Ca de Pulmonjuan CARLOS vaRGASNo ratings yet

- Clinical Guideline No. 1 (B)Document7 pagesClinical Guideline No. 1 (B)Geetha AswinNo ratings yet

- Gestational DiabetesDocument37 pagesGestational DiabetesSm BadruddozaNo ratings yet

- Research Proposal Senior People and Digital Technology in Singapore Jose RojasDocument35 pagesResearch Proposal Senior People and Digital Technology in Singapore Jose Rojasjz00hjNo ratings yet

- InsulinaDocument1 pageInsulinaRICARDO DEL ANGEL HERNANDEZNo ratings yet

- Jurnal Dinda AuliaDocument14 pagesJurnal Dinda AuliaSalmanNo ratings yet

- Effects of Processing and Preperation On Food and NutrientsDocument6 pagesEffects of Processing and Preperation On Food and Nutrientsapi-1976857050% (2)

- Nephritis by Triveni SidhaDocument23 pagesNephritis by Triveni SidhaTriveni SidhaNo ratings yet

- ObesityxxxDocument45 pagesObesityxxxAnandhi S SiddharthanNo ratings yet

- Clinical PacketDocument6 pagesClinical PacketE100% (1)

- GM FoodsDocument7 pagesGM Foodsapi-276860380No ratings yet

Classification and Pathological Anatomy: Anal Abscess and Fistula

Classification and Pathological Anatomy: Anal Abscess and Fistula

Uploaded by

azizaaharisOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Classification and Pathological Anatomy: Anal Abscess and Fistula

Classification and Pathological Anatomy: Anal Abscess and Fistula

Uploaded by

azizaaharisCopyright:

Available Formats

Books ?

Anal abscess and fistula

Mappes HJ, Farthmann EH.

Publication Details

Anal fistulae and abscesses of the perianal region

are different manifestations of the same clinical

disease. Although spontaneous recovery occurs

recurrence is most common without adequate

surgical therapy (grade C).

Perianal abscesses usually develop from the

proctodeal glands which originate from the

intersphincteric plane and perforate the internal

sphincter with their duct. The abscesses may

break through into the anal canal and resolve

completely (4), but they can also spread by a

submucosal, intersphincteric or transsphincteric

route and develop into fistulae.

Classification and pathological

anatomy

A review of the literature shows a wide variation

in classification and nomenclature of perianal

fistulae and abscesses. Therefore, in this paper the

classification based on A. Parks is used.

According to this, the classification of anorectal

abscesses and fistulae is given by their location

(figure 1).

Figure 1

a. Typical location and extent of

anorectal abscess and fistula: 1

intersphincteric, 2 transsphincteric

(ischiorectal), 3 extrasphincteric, 4

submucosal. b. Therapy: abscess

incision and incision/excision of fistula.

Superficial infections may lead to submucosal or

subcutaneous abscesses. If the abscess perforates

the external sphincter, an ischiorectal abscess

develops. If the intersphincteric abscess spreads

cranially beyond the levator muscles, a pelvirectal

abscess results. Semicircular and, mostly,

posterior progression of the infection leads to a

horseshoe abscess or fistula formation.

A fistula develops as the result of spontaneous

perforation of the abscess, or of surgical incision.

If the external and internal (anal) ostium can be

verified by examination, the so called complete

fistula will be treated as later shown. An

incomplete fistula has only one orifice.

Symptoms

Abscess

Superficial abscesses (subcutaneous, submucosal,

ischiorectal abscesses) show typical symptoms

such as pain, swelling, tenderness, fever. Due to

their anatomic location, they often cause

discomfort on walking and sitting. Usually the

vicinity to the anal canal causes painful

defecation.

Deep abscesses (intermuscular, pelvirectal) often

lack typical symptoms. Diffuse pelvic pain and

raised body temperature are found occasionally.

Besides physical examination, including rectal-

digital examination, CT, MRI or endosonography

have proven to give information about deeper

abscesses (grade B and C).

Fistulae

The symptoms of perianal fistulae depend on the

severity of inflammation. Bland fistulae may

excrete pus, sometimes serous fluid and rarely

feces, leading to pruritus ani, itching and skin

maceration. Severe symptoms occur only

occasionally, when spontaneous closure of the

fistula leads to recurrent abscess formation.

Diagnosis

Diagnostic procedures are aimed at the exact

localization of the abscess or fistula in order to

perform adequate surgical therapy leading to full

functional recovery of the patient.

Abscess

The clinical diagnosis is made by inspection and

palpation. If possible, rectoscopy/proctoscopy

should be performed, although in the case of an

acute abscess this may be too painful. For deeper

abscesses imaging procedures may be employed.

Transanal endosonography and MIR have shown

good results (5, 8) (grade B and C).

Fistulae

Besides obligatory recto- and proctoscopy the

diagnosis of fistulae may include the instillation

of methylene blue solution. The course of the

fistulae can be identified with various probes.

Occasionally, endosonography, if necessary with

contrast medium, and lately MRI have been

helpful to establish the appropriate therapeutic

strategy (5, 6, 8).

Some authors advocate preoperative manometry

in order to choose the therapeutic management

according to the risk of incontinence (grade B).

Therapy

Abscesses

Anorectal abscesses are incised and laid open on

the shortest route. The location of the abscess

determines the surgical approach. The operation

should be performed under regional or general

anesthesia.

In subcutaneous or submucosal abscesses located

within the outer anal canal, a skin excision should

be performed to create free drainage and to

prevent early closure of the skin. In perianal

abscesses synchronous fistulotomy seems not to

impair functional outcome (grade C).

Intermuscular abscesses can be drained

transanally to the inside of the anal canal. The

abscess cavity is opened by incision of the

anoderm and the internal sphincter overlying the

abscess. Ischiorectal abscesses are opened by a

sufficiently large skin incision into the

ischiorectal fossa (6), a synchronous fistulotomy

does not seem to be necessary (grade B and C).

Drainage of pelvirectal abscesses can also be

performed perineally, provided the levators are

opened wide enough to assure adequate drainage.

In a pelvirectal abscess with a fistula towards the

rectum, the drainage may also be performed

transanally.

Anal fistula

Fistulae should be classified prior to surgery,

since the crucial point for the right surgical

approach and functional results is the exact

preoperative localization of the tract of the fistula

(grade B and C). Fistulotomy of subcutaneous or

submucosal fistulae can be performed with a

probe. No extra excision of the fistulous tract is

necessary, the wound can remain open for

secondary healing. Exact localization of the inner

opening of the fistula can be attained by

endosonography or by probes. Alternatively,

some authors describe techniques using primary

closure or marsupialization of the wound edges to

the fistula ground to obtain better functional

results and/or earlier healing (grade B).

If less than the distal two thirds of the internal

sphincter muscle are involved the respective

distal sphincter parts and the anoderm can be cut

as previously described for subcutaneous fistulae.

Impaired continence is unlikely to develop. The

wound should also remain open for secondary

healing. Recent literature suggests an approach

which preserves the sphincter better, because

follow-up studies after surgery for fistula-in-ano

often show a decreased sphincter tonus and

impaired continence. This observations,

combined with EUS findings of occult sphincter

damage after fistulotomy with division of the

internal sphincter is used as argument for

sphincter-preserving procedures (as described for

transsphincteric fistulae (grade B and C)).

Transsphincteric fistulae

If more than two thirds of the sphincter muscle

are affected, division of the sphincter muscle

without loss of continence is unlikely. Therefore,

it is recommended not to severe the sphincter

muscle. Even if there will be no incontinence at

first, physiological aging may cause muscular

weakening in the long-term (grade C).

Staged procedures are sometimes necessary. In a

first step the fistula is identified and marked with

a seton. This may require anesthesia (1, 7, 9). At

the same time, external tracts of the fistula are

laid open. If there are no inflammatory changes or

if inflamed tissue can be resected, closure of the

internal ostium may be achieved by single stitch

sutures. More often a second intervention is

necessary to excochleate the remaining outer part

of the fistula, if excision is not possible. The inner

ostium is excised out of the sphincter muscle, the

muscle is sutured and the row of sutures is

covered by a mucosal advancement flap (2, 3),

which is dissected from the mucosa cephalad to

the internal aperture and sutured to the lower

margin of the mucosa (figure 2). Alternatively a

full-thickness rectal (wall) advancement flap may

be used, showing better results in certain

indications (grade B and C).

Figure 2

Sliding flap. a, b. Coring out of all the

fistulous tract and anal gland. c.

Mobilization of a mucosal flap. d.

Closure of muscular gap. e. of the

mucosa.

Extrasphincteric fistulae

The cure of extrasphincteric fistulae may also

include several surgical procedures. In a first step

the outer part of the fistula should be excised. If

the internal orifice can be securely identified, the

fistula can be closed either using a mucosal or

rectal advancement flap or with direct suture

protected by a diverting colostomy (2, 3).

Some authors recommend the use of a cutting

seton to avoid surgical division of the sphincter

apparatus. The published data show good

functional and satisfying results, although the

therapy needs a long time (grade C).

Recto-vaginal fistulae

A particular form of fistula is the recto-vaginal

fistula. Exact preoperative diagnosis is essential

to determine exactly size and localization, to

assess the stage of the anal sphincter, and to

reveal the cause of the fistula such as Crohnís

disease, radiation, obstetric injury, neoplasia,

operative trauma. The surgical approach depends

on the level of the opening of the fistula into the

rectum and into the posterior wall of the vagina

[2].

Recto-vaginal fistulae have to be differentiated

from ano-vaginal fistulae which originate from

the anal canal distal to the dentate line. Recto-

vaginal fistulae are classified according to their

location, size, and etiology. Most surgeons

arbitrarily classify a fistula as low when it can be

repaired from a perineal approach and as high if it

can be approached only transabdominally. The

size of recto-vaginal fistulae ranges from less

than 0.5 cm (small) to more than 2.5 cm (large).

The timing of the operation is determined by the

likelihood of spontaneous or non-operative

healing of the fistula. About one half of small

recto-vaginal fistulae secondary to obstetric

trauma may heal spontaneously, whereas recto-

vaginal fistulae due to inflammatory bowel

disease and radiation therapy of neoplasia rarely

will. For this reason in certain cases a

conservative approach for up to six months is

recommended, which should be used to improve

the patientís general condition.

For high fistulae closing should be performed

from an abdominal approach. After mobilizing

the rectum the fistula is transsected. Alternatively

a low anterior resection of the rectum may

become necessary.

Recto-vaginal fistulae opening into the distal

suprasphincteric part of the rectum can be treated

by a mucosal or rectal advancement flap [2]. This

requires a deviation enterostomy or adequate

bowel preparation followed by parenteral

nutrition.

After dissection of the mucosal flap the fistulous

tract is carefully excised from the muscle and the

posterior wall of the vagina, followed by suture

closure of the muscle. These sutures will be

covered by the mucosal flap. The vaginal side of

the fistula remains open.

Prior to operation exact evaluation of the

sphincter muscle is mandatory. To avoid bad

functional outcome additional sphincteroplasty

may be required [grade C].

In conclusion, surgery of perianal abscesses and

fistulae show many possible variations. As shown

in the literature the surgeonís knowledge about

anatomy and function, experience, technical skills

and patience of both patient and surgeon is

needed to achieve satisfying results [grade B and

C].

References

1. Ackermann C, Tondelli P, Herzog U.

Sphinkterschonende Operation der

transsphinkteren Analfistel. Schweiz Med

Wschr/J Suisse Med. (1994);124:1253–1256.

[PubMed]

2. Athanasiadis S, Oladeinde I, Kuprian A,

Keller B. Endorektale

Verschiebelappenplastik vs. Transperinealer

Verschluss bei der chirurgischen Behandlung

der rektovaginalen Fisteln. Eine prospektive

Langzeitstudie bei 88 Patientinnen. Chirurg.

(1995);66:493–502. [PubMed]

3. Farthmann E H, Ruf G. Zur Problematik der

Kontinenzerhaltung bei der Behandlung von

IBD-assoziierten Analfisteln. Schweiz

Rundsch Med Prax. (1997);86:1968–1070.

[PubMed]

4. Hamalainen K P, Sainio A P. Incidence of

fistulas after drainage of acute anorectal

abscesses. Dis Colon Rectum.

(1998);41:1357–1361. [PubMed]

5. Poen A C, Felt-Bersma R J, Eijsbouts Q A,

Cuesta M A, Meuwissen S G. Hydrogen

peroxide-enhanced transanal ultrasound in the

assessment of fistula-in-ano. Dis Colon

Rectum. (1998);41:1147–1152. [PubMed]

6. Sailer M, Fuchs KH, Kraemer M, Thiede A

(1998) Stufenkonzept zur Sanierung

komplexer Analfisteln. Zbl Chir 123: 840–

805; discussion 846 . [PubMed]

7. Spencer J A, Chapple K, Wilson D, Ward J,

Windsor A C, Ambrose N S. Outcome after

surgery for perianal fistula. Am J Roentgenol.

(1998);171:403–406. [PubMed]

8. Stoker J, Fa V E, Eijkemans M J, Schouten W

R, Lameris J S. Endoanal MIR of perianal

fistulas: the optimal imaging planes. Eur

Radiol. (1998);8:1212–1216. [PubMed]

9. Van Tets W F, Kuijpers J H. Seton treatment

of perianal fistula with high anal or rectal

opening. Br J Surg. (1995);82:895–897.

[PubMed]

Publication Details

Author Information

Authors

H.J. Mappes and E.H. Farthmann.

Affiliations

Department of Surgery, University od Freiburg, Freiburg,

Germany

Copyright

Copyright © 2001, W. Zuckschwerdt Verlag GmbH.

Publisher

Zuckschwerdt, Munich

NLM Citation

Mappes HJ, Farthmann EH. Anal abscess and fistula. In:

Holzheimer RG, Mannick JA, editors. Surgical Treatment:

Evidence-Based and Problem-Oriented. Munich:

Zuckschwerdt; 2001.

Prev Next

You might also like

- PDF Adhd in The Schools Assessment and Intervention Strategies Dupaul Ebook Full ChapterDocument53 pagesPDF Adhd in The Schools Assessment and Intervention Strategies Dupaul Ebook Full Chapteranne.wood454100% (6)

- FdarDocument2 pagesFdarkasandra dawn Beriso67% (3)

- DLP Communicable DiseasesDocument10 pagesDLP Communicable DiseasesPlacida Mequiabas National High SchoolNo ratings yet

- Management of Anal FistulaDocument5 pagesManagement of Anal Fistulailham adhaniNo ratings yet

- A No Rectal AbscessDocument12 pagesA No Rectal AbscesswawdeniseNo ratings yet

- Anal Fistula Dont DeleteDocument28 pagesAnal Fistula Dont DeleteRazeen RiyasatNo ratings yet

- Anal FistulasDocument9 pagesAnal FistulasikeernawatiNo ratings yet

- Anal FistulaDocument2 pagesAnal FistulayayassssssNo ratings yet

- 2 GYNE 1a - Benign Lesions of The Vagina, Cervix and UterusDocument11 pages2 GYNE 1a - Benign Lesions of The Vagina, Cervix and UterusIrene FranzNo ratings yet

- Anal FistulaDocument7 pagesAnal FistulaKate Laxamana Guina100% (1)

- Symptoms: Anal Fistula, or Fistula-In-Ano, Is An Abnormal Connection Between TheDocument5 pagesSymptoms: Anal Fistula, or Fistula-In-Ano, Is An Abnormal Connection Between ThePandu Nugroho KantaNo ratings yet

- Tinjauan Pustaka Fistula PerianalDocument3 pagesTinjauan Pustaka Fistula PerianalAde Perdana SetiawanNo ratings yet

- Fistula PerianalDocument25 pagesFistula PerianalHafiizh Dwi PramuditoNo ratings yet

- Anorectal Abscess - Background, Anatomy, PathophysiologyDocument9 pagesAnorectal Abscess - Background, Anatomy, Pathophysiology송란다No ratings yet

- Translabprevention CSFJCGPRLDocument5 pagesTranslabprevention CSFJCGPRLJohn GoddardNo ratings yet

- Whiteford2007 Abses PerianalDocument8 pagesWhiteford2007 Abses PerianalPudyo KriswhardaniNo ratings yet

- Anorectal Surgery PDFDocument33 pagesAnorectal Surgery PDFLuminitaDumitriuNo ratings yet

- Art 20195764Document3 pagesArt 20195764Clarence Glenn JocsonNo ratings yet

- Complex Fistulas in Ano: Seton Placement An Effective Solution To Tricky Enigma ShortDocument6 pagesComplex Fistulas in Ano: Seton Placement An Effective Solution To Tricky Enigma ShortIJAR JOURNALNo ratings yet

- Four Cases of Preauricular Fistula Based On Systematic Review Resulted New AlgorithmDocument10 pagesFour Cases of Preauricular Fistula Based On Systematic Review Resulted New AlgorithmMuhammad Dody HermawanNo ratings yet

- Fistula in AnoDocument4 pagesFistula in AnoosamabinziaNo ratings yet

- Operative Management of Anorectal FistulasDocument19 pagesOperative Management of Anorectal Fistulasdim firmNo ratings yet

- Procedure ON: EpisiotomyDocument7 pagesProcedure ON: EpisiotomyShalabh JoharyNo ratings yet

- Anorectal Abscess: Principles of Internal Medicine, 18E. New York, Ny: Mcgraw-Hill 2012Document7 pagesAnorectal Abscess: Principles of Internal Medicine, 18E. New York, Ny: Mcgraw-Hill 2012Irene SohNo ratings yet

- Appendiktomi Translate BookDocument19 pagesAppendiktomi Translate Bookalyntya melatiNo ratings yet

- Fsurg 07 559443Document9 pagesFsurg 07 559443johana.solerNo ratings yet

- Stricture Urethra PDFDocument12 pagesStricture Urethra PDFNasti YL HardiansyahNo ratings yet

- Anal Abscess and FistulaDocument12 pagesAnal Abscess and FistulaGustavoZapataNo ratings yet

- Bulbar Urethroplasty Using The Dorsal Approach: Current TechniquesDocument7 pagesBulbar Urethroplasty Using The Dorsal Approach: Current TechniquesFitrah TulijalrezyaNo ratings yet

- Anal Fistula New TechniqueDocument7 pagesAnal Fistula New TechniqueSuhenri SiahaanNo ratings yet

- Fistula-In-Ano Extending To The ThighDocument5 pagesFistula-In-Ano Extending To The Thightarmohamed.muradNo ratings yet

- FORESKIN ANOPLASTY Freeman1984Document5 pagesFORESKIN ANOPLASTY Freeman1984Joaquin Martinez HernandezNo ratings yet

- TECNICADocument7 pagesTECNICASiris Rieder GarridoNo ratings yet

- German S3 Guidelines: Anal Abscess and Fistula (Second Revised Version)Document55 pagesGerman S3 Guidelines: Anal Abscess and Fistula (Second Revised Version)Bunga AmiliaNo ratings yet

- Absceso y Fistula AnalDocument24 pagesAbsceso y Fistula AnalSinue PumaNo ratings yet

- Advances: Management of Fistula in Ano - RecentDocument76 pagesAdvances: Management of Fistula in Ano - Recentyoga_kusmawanNo ratings yet

- Submental Intubation in Patients With Complex Maxillofacial InjuriesDocument4 pagesSubmental Intubation in Patients With Complex Maxillofacial InjuriesMudassar SattarNo ratings yet

- Akira, 2022Document6 pagesAkira, 2022Ahmed SalahNo ratings yet

- A Tour ofDocument10 pagesA Tour ofChaimae OuafikNo ratings yet

- Session 5-Anorectal FistulaDocument34 pagesSession 5-Anorectal FistulanshabimussakolleNo ratings yet

- Perianal AbscessFistula DiseaseDocument9 pagesPerianal AbscessFistula Diseasetri jayaningratNo ratings yet

- Layers of Abdominal Wall When Performing An AppendicectomyDocument2 pagesLayers of Abdominal Wall When Performing An AppendicectomydrsamnNo ratings yet

- Guidelines For The Multidisciplinary Management of Crohn's Perianal Fistulas: Summary StatementDocument8 pagesGuidelines For The Multidisciplinary Management of Crohn's Perianal Fistulas: Summary StatementdeviNo ratings yet

- 4Y7zAw Ccrs23149Document12 pages4Y7zAw Ccrs23149Jefry JapNo ratings yet

- Aetiology, Pathology and Management of Enterocutaneous FistulaDocument34 pagesAetiology, Pathology and Management of Enterocutaneous Fistulabashiruaminu100% (4)

- Jurnal tht7Document5 pagesJurnal tht7Tri RominiNo ratings yet

- Anal FistulaDocument6 pagesAnal Fistulaalaixmunakamala100% (1)

- York Mason Procedure PDFDocument12 pagesYork Mason Procedure PDFMohammed Mustafa ShaatNo ratings yet

- Journal 2015Document3 pagesJournal 2015Rakha Sulthan SalimNo ratings yet

- Abcess PeritonsillarDocument21 pagesAbcess PeritonsillarribeetleNo ratings yet

- Genital Tract InjuriesDocument24 pagesGenital Tract InjuriesManisha ThakurNo ratings yet

- Wiitm 7 17104 PDFDocument4 pagesWiitm 7 17104 PDFZam HusNo ratings yet

- CANALPLASTYDocument7 pagesCANALPLASTYluar3003No ratings yet

- Atlas of Vesicovaginal FistulaDocument7 pagesAtlas of Vesicovaginal FistulaYodi SoebadiNo ratings yet

- Rupture UterusDocument23 pagesRupture Uterushacker ammerNo ratings yet

- The Most Common Hernia in Females IsDocument22 pagesThe Most Common Hernia in Females IsNessreen JamalNo ratings yet

- Anterior Sagittal Approach and Total Urogenital Mobilization For The Treatment of Persistent Urogenital SinusDocument4 pagesAnterior Sagittal Approach and Total Urogenital Mobilization For The Treatment of Persistent Urogenital SinusGunduz AgaNo ratings yet

- Fistula in AnoDocument21 pagesFistula in AnoHannah LeiNo ratings yet

- Lateral Internal Sphincterotomy For Chronic Idiopathic Anal Fissure - An Alterative ApproachDocument5 pagesLateral Internal Sphincterotomy For Chronic Idiopathic Anal Fissure - An Alterative ApproachNicolás CopaniNo ratings yet

- Article Thyroglose 1Document2 pagesArticle Thyroglose 1Jessica Paulina Salazar RuizNo ratings yet

- Endoscopic Ultrasound Management of Pancreatic Lesions: From Diagnosis to TherapyFrom EverandEndoscopic Ultrasound Management of Pancreatic Lesions: From Diagnosis to TherapyAntonio FacciorussoNo ratings yet

- Tatalaksana Ketergantungan StimulantDocument2 pagesTatalaksana Ketergantungan StimulantazizaaharisNo ratings yet

- Gluteal Abscess: An Unusual Complication of Bacille Calmette-GuérinDocument1 pageGluteal Abscess: An Unusual Complication of Bacille Calmette-GuérinazizaaharisNo ratings yet

- 27 Testicular PainDocument2 pages27 Testicular PainazizaaharisNo ratings yet

- Laporan Ok ObsgynDocument24 pagesLaporan Ok ObsgynazizaaharisNo ratings yet

- Kangaroo Mother CareDocument8 pagesKangaroo Mother CareSanthosh.S.UNo ratings yet

- Drugs AddictionDocument25 pagesDrugs AddictionReader67% (3)

- Accident and Incident Report ProcedureDocument23 pagesAccident and Incident Report ProcedureWakarusa Co100% (1)

- CHSSDocument8 pagesCHSSsariyu143No ratings yet

- Mammography Sas 10Document11 pagesMammography Sas 10faith mari madrilejosNo ratings yet

- Research Paper On Expert System PDFDocument4 pagesResearch Paper On Expert System PDFgz7vxzyz100% (1)

- How Social Media Impacts The Mental Health of Grade 10 Junior High School StudentsDocument2 pagesHow Social Media Impacts The Mental Health of Grade 10 Junior High School StudentsRegor Salvador ArboNo ratings yet

- School Based ImmunizationDocument28 pagesSchool Based ImmunizationDarell Paguel Permato70% (10)

- 1st Sem Sport Science Assignment ContentDocument9 pages1st Sem Sport Science Assignment ContentKobasen LimNo ratings yet

- Occupational Health ObjectivesDocument1 pageOccupational Health Objectivesbook1manNo ratings yet

- Parent-Teen Talk Facilitator's Guide - LexcodeDocument135 pagesParent-Teen Talk Facilitator's Guide - LexcodeRochelle AdlaoNo ratings yet

- Scope and DelimitationDocument8 pagesScope and DelimitationLiza MarigondonNo ratings yet

- Unit I - Introduction-to-Midwifery-Obstetrical-NursingDocument43 pagesUnit I - Introduction-to-Midwifery-Obstetrical-NursingN. Siva100% (9)

- Community Health NutritionDocument31 pagesCommunity Health NutritionJosephNo ratings yet

- Characteristics of Community HealthDocument2 pagesCharacteristics of Community HealthRichard Balili100% (1)

- CONCLUSIONDocument2 pagesCONCLUSIONÑàgùr BåshaNo ratings yet

- Tamizaje Ca de PulmonDocument11 pagesTamizaje Ca de Pulmonjuan CARLOS vaRGASNo ratings yet

- Clinical Guideline No. 1 (B)Document7 pagesClinical Guideline No. 1 (B)Geetha AswinNo ratings yet

- Gestational DiabetesDocument37 pagesGestational DiabetesSm BadruddozaNo ratings yet

- Research Proposal Senior People and Digital Technology in Singapore Jose RojasDocument35 pagesResearch Proposal Senior People and Digital Technology in Singapore Jose Rojasjz00hjNo ratings yet

- InsulinaDocument1 pageInsulinaRICARDO DEL ANGEL HERNANDEZNo ratings yet

- Jurnal Dinda AuliaDocument14 pagesJurnal Dinda AuliaSalmanNo ratings yet

- Effects of Processing and Preperation On Food and NutrientsDocument6 pagesEffects of Processing and Preperation On Food and Nutrientsapi-1976857050% (2)

- Nephritis by Triveni SidhaDocument23 pagesNephritis by Triveni SidhaTriveni SidhaNo ratings yet

- ObesityxxxDocument45 pagesObesityxxxAnandhi S SiddharthanNo ratings yet

- Clinical PacketDocument6 pagesClinical PacketE100% (1)

- GM FoodsDocument7 pagesGM Foodsapi-276860380No ratings yet