Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Cornejo Vs Sandiganbayan

Cornejo Vs Sandiganbayan

Uploaded by

Ella PerezCopyright:

Available Formats

You might also like

- INTENGAN Vs CADocument2 pagesINTENGAN Vs CAJoona Kis-ingNo ratings yet

- People of The Philippines vs. Danny GodoyDocument7 pagesPeople of The Philippines vs. Danny GodoyDales BatoctoyNo ratings yet

- Geraldo Vs PeopleDocument3 pagesGeraldo Vs PeopleMarlene TongsonNo ratings yet

- SALINAS, Mark Ian B. (Assignment)Document5 pagesSALINAS, Mark Ian B. (Assignment)Ukulele PrincessNo ratings yet

- (Digest) Malayan Insurance V Phil Nails & Wires CorpDocument3 pages(Digest) Malayan Insurance V Phil Nails & Wires CorpTerasha Reyes-Ferrer100% (1)

- Trans-Pacific Industrial v. CADocument1 pageTrans-Pacific Industrial v. CAKimNo ratings yet

- Hearsay Rule Exception. Dying DeclarationDocument48 pagesHearsay Rule Exception. Dying DeclarationAngeli Pauline JimenezNo ratings yet

- PEOPLE OF THE PHILIPPINES, Plaintiff-Appellee, Vs - EUTIQUIA CARMEN, Celedonia Fabie, Delia Sibonga, Alexander Sibonga, Reynario NuezDocument5 pagesPEOPLE OF THE PHILIPPINES, Plaintiff-Appellee, Vs - EUTIQUIA CARMEN, Celedonia Fabie, Delia Sibonga, Alexander Sibonga, Reynario NuezPearl Anne GumaposNo ratings yet

- Done - 11. Guingona, Jr. v. City Fiscal of Manila - 1984Document2 pagesDone - 11. Guingona, Jr. v. City Fiscal of Manila - 1984sophiaNo ratings yet

- CITY OF MANILA v. CABANGIS PDFDocument2 pagesCITY OF MANILA v. CABANGIS PDFMark Carlo YumulNo ratings yet

- People v. de JoyaDocument1 pagePeople v. de JoyalividNo ratings yet

- Arthur Zarate Vs RTCDocument2 pagesArthur Zarate Vs RTCJigo DacuaNo ratings yet

- People Vs LangcuaDocument1 pagePeople Vs LangcuaTootsie Guzma100% (1)

- R130 S33 People Vs LadaoDocument2 pagesR130 S33 People Vs LadaoOculus DecoremNo ratings yet

- Aguirre vs. People - DigestDocument2 pagesAguirre vs. People - DigestMaria Jennifer Yumul BorbonNo ratings yet

- 130 People V BasayDocument2 pages130 People V BasayJudy Ann ShengNo ratings yet

- G.R. No. 199877 August 13, 2012 PEOPLE OF THE PHILIPPINES, Plaintiff-Appellee, ARTURO LARA y ORBISTA, Accused-AppellantDocument10 pagesG.R. No. 199877 August 13, 2012 PEOPLE OF THE PHILIPPINES, Plaintiff-Appellee, ARTURO LARA y ORBISTA, Accused-AppellantBUTTERFLYNo ratings yet

- Fernandez VsDocument1 pageFernandez VsAnj MerisNo ratings yet

- Solla Vs AscuetaDocument2 pagesSolla Vs AscuetaAilyn AñanoNo ratings yet

- Heirs of Sabanpan Vs Comorposa 408 Scra 692Document2 pagesHeirs of Sabanpan Vs Comorposa 408 Scra 692Racheal SantosNo ratings yet

- Rudecon MGT Corp V Camacho 437 Scra 202Document4 pagesRudecon MGT Corp V Camacho 437 Scra 202emdi19No ratings yet

- Case Digest Case No. 5 Case No. 6Document3 pagesCase Digest Case No. 5 Case No. 6carl fuerzasNo ratings yet

- People vs. VillamarDocument5 pagesPeople vs. VillamarNash LedesmaNo ratings yet

- G.R. No. 139150 Pablo Dela Cruz Vs CADocument2 pagesG.R. No. 139150 Pablo Dela Cruz Vs CAPaul Arman MurilloNo ratings yet

- 040 Republic V SandiganbayanDocument3 pages040 Republic V SandiganbayanJudy Ann ShengNo ratings yet

- People v. YatcoDocument3 pagesPeople v. YatcoStella Marie Ad AstraNo ratings yet

- 133 Geraldo V PeopleDocument2 pages133 Geraldo V PeopleJudy Ann ShengNo ratings yet

- Lee v. Court of Appeals (G.R. No. 90423, September 6, 1991)Document1 pageLee v. Court of Appeals (G.R. No. 90423, September 6, 1991)Migs MarcosNo ratings yet

- Cleofas vs. St. Peter FinalDocument3 pagesCleofas vs. St. Peter Finalandrew estimoNo ratings yet

- 119 People v. IrangDocument2 pages119 People v. IrangPatricia Kaye O. SevillaNo ratings yet

- Auro v. YasisDocument7 pagesAuro v. YasisdenverNo ratings yet

- 36 - People V de JoyaDocument3 pages36 - People V de JoyaIra AgtingNo ratings yet

- Consumido V RosDocument1 pageConsumido V RosElaizza Concepcion0% (1)

- United States vs. Teresa Concepcion GR No. 10396 July 29, 1915Document1 pageUnited States vs. Teresa Concepcion GR No. 10396 July 29, 1915laika corralNo ratings yet

- Digest - Conde To American HomeDocument22 pagesDigest - Conde To American HomeKaye MendozaNo ratings yet

- C3h - 14 MERALCO v. QuisumbingDocument2 pagesC3h - 14 MERALCO v. QuisumbingAaron AristonNo ratings yet

- Hearsay Mallari V PeopleDocument1 pageHearsay Mallari V PeopleJeremiah John Soriano NicolasNo ratings yet

- 23 Fabia v. IACDocument2 pages23 Fabia v. IACTelle MarieNo ratings yet

- #41 Estrada v. Desierto - REYESDocument3 pages#41 Estrada v. Desierto - REYESRuby ReyesNo ratings yet

- (G.R. No. 205172. June 15, 2021) Disini DamagesDocument54 pages(G.R. No. 205172. June 15, 2021) Disini DamagesChatNo ratings yet

- People vs. BaronDocument1 pagePeople vs. BaronMACNo ratings yet

- People vs. FabonDocument13 pagesPeople vs. FabonZoe Kristeun GutierrezNo ratings yet

- RPC 1 (Cases)Document20 pagesRPC 1 (Cases)ZL ZLNo ratings yet

- Repubic Vs Development Resources CorpDocument2 pagesRepubic Vs Development Resources CorpVince Llamazares LupangoNo ratings yet

- Magdayao v. PeopleDocument1 pageMagdayao v. PeopleRomela Eleria GasesNo ratings yet

- People V Estibal G.R. No. 208749Document15 pagesPeople V Estibal G.R. No. 208749Jade Palace TribezNo ratings yet

- Miranda V PDICDocument3 pagesMiranda V PDICJennyNo ratings yet

- EVID (First 5 Digests)Document14 pagesEVID (First 5 Digests)doraemonNo ratings yet

- 32 - Commonweath Act 142, RA 6085Document1 page32 - Commonweath Act 142, RA 6085Regina CoeliNo ratings yet

- People v. DunigDocument9 pagesPeople v. DunigAstrid Gopo BrissonNo ratings yet

- Laragan Vs CADocument1 pageLaragan Vs CAGillian Caye Geniza BrionesNo ratings yet

- 004 People Vs YatcoDocument3 pages004 People Vs YatcoEric TamayoNo ratings yet

- Sps. Dato v. Bank of The Philippine IslandDocument10 pagesSps. Dato v. Bank of The Philippine IslandSamuel John CahimatNo ratings yet

- Zafra Vs PeopleDocument3 pagesZafra Vs PeopleRobertNo ratings yet

- Case #10 Mallilin V. People G.R. No. 172953Document4 pagesCase #10 Mallilin V. People G.R. No. 172953Carmel Grace KiwasNo ratings yet

- People v. Queriza, 279 SCRA 145 (1997)Document13 pagesPeople v. Queriza, 279 SCRA 145 (1997)GioNo ratings yet

- G.R. Nos. 90191-96 January 28, 1991 PEOPLE OF THE PHILIPPINES, Plaintiff-Appellee, Anacleto FuruggananDocument21 pagesG.R. Nos. 90191-96 January 28, 1991 PEOPLE OF THE PHILIPPINES, Plaintiff-Appellee, Anacleto FuruggananJoyleen HebronNo ratings yet

- Sugar Regulatory Administration vs. TormonDocument1 pageSugar Regulatory Administration vs. TormonMaria Florida ParaanNo ratings yet

- Petitioner vs. vs. Respondent: en BancDocument8 pagesPetitioner vs. vs. Respondent: en BancClarence ProtacioNo ratings yet

- Custom Search: Today Is Wednesday, February 21, 2018Document5 pagesCustom Search: Today Is Wednesday, February 21, 2018Marchini Sandro Cañizares KongNo ratings yet

- AKBAYAN Vs AQUINO DigestDocument2 pagesAKBAYAN Vs AQUINO DigestElla PerezNo ratings yet

- 47 - Municipality of San Fernando Vs Judge Firme DigestDocument2 pages47 - Municipality of San Fernando Vs Judge Firme DigestElla PerezNo ratings yet

- 3-Pamatong Vs COMELECDocument3 pages3-Pamatong Vs COMELECElla PerezNo ratings yet

- Robles v. HermanosDocument8 pagesRobles v. HermanosElla PerezNo ratings yet

- 17-Enrile vs. Senate of Electoral Tribunal DigestDocument2 pages17-Enrile vs. Senate of Electoral Tribunal DigestElla PerezNo ratings yet

- Reyes V BagatsingDocument16 pagesReyes V BagatsingElla PerezNo ratings yet

- Rodriguez v. Macapagal-ArroyoDocument28 pagesRodriguez v. Macapagal-ArroyoElla PerezNo ratings yet

- F. Gonzales Vs PeopleDocument6 pagesF. Gonzales Vs PeopleElla PerezNo ratings yet

- B. Ariate Vs PPDocument9 pagesB. Ariate Vs PPElla PerezNo ratings yet

- C. Parel Vs PrudencioDocument14 pagesC. Parel Vs PrudencioElla PerezNo ratings yet

- Appeals Court Upholds Conviction of John HaggertyDocument67 pagesAppeals Court Upholds Conviction of John Haggertyliz_benjamin6490No ratings yet

- Consti Law 2 Reviewer Sec 12 To 14Document2 pagesConsti Law 2 Reviewer Sec 12 To 14May Angelica TenezaNo ratings yet

- Cat WalkDocument36 pagesCat WalkAmir HamdzahNo ratings yet

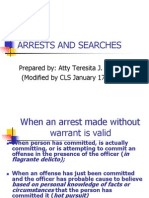

- Arrests, Inquest, Pi, SearchDocument43 pagesArrests, Inquest, Pi, SearchAsiongNo ratings yet

- Affidavit of ClarificationDocument2 pagesAffidavit of Clarificationmarvin dalayapNo ratings yet

- Tible Digest Remedial Law - Docx FinalDocument3 pagesTible Digest Remedial Law - Docx FinalKim Roque-AquinoNo ratings yet

- Roman Motion To Dimiss 010824Document127 pagesRoman Motion To Dimiss 010824Liberty NationNo ratings yet

- To Be Presumed Innocent Until The Contrary Is Proved Beyond Reasonable DoubtDocument4 pagesTo Be Presumed Innocent Until The Contrary Is Proved Beyond Reasonable DoubtVillar John EzraNo ratings yet

- People Vs BasquezDocument3 pagesPeople Vs Basqueztorralba.nash.amethystNo ratings yet

- The Case of Hubert WebDocument2 pagesThe Case of Hubert WebKABACAN BFP12No ratings yet

- 4.carreon vs. Agcaoili DigestDocument2 pages4.carreon vs. Agcaoili DigestCaroline A. LegaspinoNo ratings yet

- Constitution of Criminal CourtsDocument35 pagesConstitution of Criminal CourtsCANNo ratings yet

- 2011.09.30 Motion - To - Correct The Supplemental RecordDocument12 pages2011.09.30 Motion - To - Correct The Supplemental RecordElisa Scribner LoweNo ratings yet

- People of The Philippines vs. Hon. Mariano CastanedaDocument2 pagesPeople of The Philippines vs. Hon. Mariano CastanedaMmm GggNo ratings yet

- People V TulinDocument2 pagesPeople V TulinJerico Godoy100% (1)

- Right Against Self-IncriminationDocument1 pageRight Against Self-IncriminationlmafNo ratings yet

- Sharia Courts CasesDocument14 pagesSharia Courts CasesLou StellarNo ratings yet

- CLJ 106 QuizDocument2 pagesCLJ 106 QuizFlores JoevinNo ratings yet

- Land Acquisition Act 1894Document2 pagesLand Acquisition Act 1894Bidisha GhoshalNo ratings yet

- Metropolitan Bank and Trust Comp. v. Absolute Management Corp.Document8 pagesMetropolitan Bank and Trust Comp. v. Absolute Management Corp.Romar John M. GadotNo ratings yet

- 118 Balila v. IACDocument1 page118 Balila v. IACJoshua Alexander CalaguasNo ratings yet

- Basic Legal GlossaryDocument14 pagesBasic Legal GlossaryDale GilmartinNo ratings yet

- Bimeda Vs PerezDocument5 pagesBimeda Vs PerezAnjNo ratings yet

- Mayes Et Al v. Sportsstuff, Inc. Et Al - Document No. 2Document2 pagesMayes Et Al v. Sportsstuff, Inc. Et Al - Document No. 2Justia.comNo ratings yet

- Republic of The Philippines Cagayan State University College of Law Andrews Campus, Tuguegarao City, Cagayan Evidence Final Examination (Part I)Document6 pagesRepublic of The Philippines Cagayan State University College of Law Andrews Campus, Tuguegarao City, Cagayan Evidence Final Examination (Part I)Mikes FloresNo ratings yet

- TJoinDocument4 pagesTJoinHollyRustonNo ratings yet

- Surrender PetitionDocument2 pagesSurrender PetitionAdityaNo ratings yet

- PAT Compromise Agreement Cases Full TextDocument33 pagesPAT Compromise Agreement Cases Full TextLea NajeraNo ratings yet

- Allgemaine Vs Metrobank Case DigestDocument2 pagesAllgemaine Vs Metrobank Case Digestkikhay11No ratings yet

- US vs. KieneDocument2 pagesUS vs. Kieneerlaine_franciscoNo ratings yet

Cornejo Vs Sandiganbayan

Cornejo Vs Sandiganbayan

Uploaded by

Ella PerezOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Cornejo Vs Sandiganbayan

Cornejo Vs Sandiganbayan

Uploaded by

Ella PerezCopyright:

Available Formats

EN BANC

[G.R. No. L-58831. July 31, 1987.]

ALFREDO R. CORNEJO, SR. , petitioner, vs. THE HON.

SANDIGANBAYAN , respondent.

SYLLABUS

1. REMEDIAL LAW; EVIDENCE; CREDIBILITY OF WITNESSES; FINDINGS OF

FACT OF THE TRIAL COURT ACCORDED FULL WEIGHT ON APPEAL. — The testimony of

complainant Beth Chua should be taken in its entirety. Not to be overlooked is her

categorical statement that although she initially entertained doubts as to the

personality of the petitioner and the veracity of his representations, she finally believed

him because he talked nicely and also because he warned her that unless she complied

with the purported requirements of the Metro Manila Commission, she could be liable

for the penal sanctions under the Building Code. She further stated that she believed

petitioner's statement that having her store measured and a plan thereof made would

prevent her eviction from the subject premises. This portion of the testimony of Beth

Chua was accorded full weight and credence by the trial court and We find no cogent

reason to disturb such assessment, particularly where the veracity of said statements

was demonstrated by complainant's own act of agreeing to have her store measured

and a plan thereof sketched as per advice of petitioner.

2. ID.; ID.; ADMISSIBILITY THEREOF; DOCUMENTARY EVIDENCE PRESENTED

NOT AS AN INDEPENDENT EVIDENCE BUT AS PART OF THE TESTIMONY OF THE

COMPLAINANT; NOT COVERED BY THE HEARSAY RULE. — Anent petitioner's objection

to the admissibility of Exhibit B, the certification issued by Pasay City Engineer Jesus

Reyna to the effect that petitioner was not authorized to inspect and investigate

privately-owned buildings. We find no reversible error, much less grave abuse of

discretion on the part of the trial court in admitting the same. It must be noted that

Exhibit B was not presented as an independent evidence to prove the want of authority

of petitioner to inspect and investigate privately-owned buildings, but merely as part of

the testimony of the complainant that such certification was issued in her presence and

the declaration of Assistant Pasay City Engineer Ceasar Contreras that the signature

appearing thereon was that of Engineer Reyna. Where the statement or writings

attributed to a person who is not on the witness stand are being offered not to prove

the truth of the facts stated therein but only to prove that such statements were

actually made or such writings were executed, such evidence is not covered by the

hearsay rule.

3. CRIMINAL LAW; ENTRAPMENT; STRATEGY EMPLOYED BY THE POLICE IN

EFFECTING ARREST. — Petitioner further attempts to convince Us that he was induced

and instigated by complainant and the police to commit the crime charged. The facts

of the case do not support such assertion. When petitioner returned to complainant's

house on the day he was arrested, he had already committed the deceit punished by

law and had effectively defrauded complainant of her money. His act of going to

complainant's house was a mere continuation of the unlawful scheme, already

consummated within the contemplation of the law, so that the strategy employed by

the police in affecting his arrest was a clear case of entrapment, which is recognized as

a lawful means of law enforcement.

CD Technologies Asia, Inc. © 2016 cdasiaonline.com

4. REMEDIAL LAW; EVIDENCE; PRESUMPTION OF REGULARITY IN THE

PERFORMANCE OF OFFICIAL DUTIES; APPLIED IN CASE AT BAR. — Suffice it to say

that the other grounds cited by petitioner in his supplemental petition deserve scant

consideration for they either do not have any relevance to the petition at bar [such as

petitioner's allegation that the prosecution is politically-motivated] or could not alter

the result of the case, such as petitioner's bare allegation of lack of preliminary

investigation, which cannot overcome the presumption of regularity in the performance

of official duties [Sec. 5(m), Rule 131, Rules of Court];

DECISION

FERNAN , J : p

Petitioner Alfredo R. Cornejo, Sr. seeks a review on certiorari of the decision

dated September 9, 1981 of the Sandiganbayan in Criminal Case No. 2495 entitled

"People of the Philippines, Plaintiff, vs. Alfredo Cornejo, Sr. and Rogelio Alzate

Cornejo * , Accused", nding him "guilty beyond reasonable doubt as principal of

the crime of Estafa [Swindling] as de ned and penalized under Article 315,

paragraph 4th, sub-paragraph 2-(a), in relation to Article 214, both of the Revised

Penal Code; and, appreciating against him the aggravating circumstance of

advantage of public position, without any mitigating circumstance in offset; . . .

[and] sentencing him to Four (4) months and Twenty-One (21) Days of arresto

mayor, with the accessories provided by law; to suffer perpetual special

disquali cation, to indemnify the complainant, Beth Chua, in the amount of One

Hundred Pesos [P100.00], and to pay his proportionate share of the costs." 1

The facts of the case, as found by the trial court, are as follows:

"For already more than 14 years, complainant Beth Chua had been

renting the premises at 105 Moana Street, Pasay City, owned by one

Crisanto Bautista, which she devoted as a residence and a sari-sari store. In

the morning of December 11, 1979, accused Alfredo R. Cornejo, Sr.

[hereinafter referred to as accused Engineer], then a City Public Works

Supervisor in Pasay City, called at the store of complainant looking for a

woman who supposedly called him up from there. In the course of his

conversations with complainant, during which he introduced himself to be

connected with the City Engineer's Of ce, accused Engineer represented to

complainant that he was empowered to inspect private buildings and that,

pursuant to the Building Code, the Metro Manila Commission requires that

the oor area of all houses be measured, a service for which a fee of P3.00

per square meter is charged, but that, if said service is undertaken by him,

the charge would be only P0.50 per square meter. In addition, said accused

assured complainant's that, while her premises were under investigation, she

could not be ejected despite the pending ejectment suit against her.

Although she initially entertained doubts about the personality of accused

Engineer, complainant eventually believed him not only because he talked

nicely but also because he warned her that unless she complies with said

requirements, she could be liable for the penal sanctions under the Building

Code. Complainant was thus prevailed upon to agree that the required

service be undertaken by accused Engineer for which she would pay from

P300.00 to P400.00 and, since the entire procedure had to be done step by

CD Technologies Asia, Inc. © 2016 cdasiaonline.com

step, she would have to initially pay P150.00 for the measurement and the

preparation of the Floor plan of the house. As agreed with accused Engineer,

at 3:00 o'clock in the afternoon of that day, accused Rogelio Alzate Cornejo

(hereinafter referred to as accused Draftsman], nephew of accused Engineer,

together with one Conrado Ocampo, showed up at Complainant's place and

made measurements therein. However, because complainant was short of

funds, she was able to deliver to accused Draftsman only P100.00 out of the

P150.00 agreed upon with accused Engineer. For that amount, accused

Draftsman issued complainant a receipt [Exh. A] and at the same time asked

her to sign a bunch of blank forms and other papers which he took back.

"The following morning, December 12, 1979, because complainant

saw accused Engineer go to the house of her neighbor, a Mrs. Dalisay

Bernal, complainant asked the latter what said accused was there for and

she was told that he went there also for the same purpose. Since Mrs. Bernal

share the doubts previously entertained by her, the two of them decided to

see Barangay Captain Carmen Robles about the matter. With the Barangay

Captain, complainant and Mrs. Bernal then went to the Pasay City Hall

where they saw City Engineer Jesus I. Reyna who told them that accused

Engineer was not authorized to conduct inspection and investigation of

privately owned buildings — a fact later con rmed by a certi cation issued

to that effect by said City Engineer [Exhibit B]. With this discovery, the matter

was reported to the Intelligence and Special Operations Group, Pasay City

Police. It developed that in the morning of December 14, 1979, Conrado

Ocampo called on complainant at the instance of accused Engineer to

collect the balance of P50.00 but complainant did not then pay him. Instead,

she asked that accused Engineer be the one to pick up the money that

afternoon because she wanted to ask him something. This was brought to

the attention of Captain Manuel Malonzo of the ISOG who caused the

statement of complainant to be taken by then Police Sergeant Nicanor del

Rosario [Exhibit C] and an entrapment was planned.

"With money consisting of two 20-pesos bill and one 10 peso bill

previously xerox-copied to be used by complainant as pay-off money

[Exhibits E and E-1], an ISOG team composed of Sgt. Del Rosario, Sgt. Pablo

Canlas and Pfc. Anacleto Lacad and Pascual de la Cruz, repaired to the

vicinity of complainant's store. At about 1:00 o'clock that afternoon, accused

Engineer showed up at complainant's store and, there, complainant handed

to him an envelope containing the pay-off money which he received. As said

accused was in the act of placing the envelope in his attache case, the

police accosted him and took the money from him. Thereafter, said accused

was taken to the police Headquarters, together with complainant whose

supplementary statement [Exhibit D] was taken. In due course, with the

evidence gathered, as well as the statements of accused Engineer, the police

of cers and other witnesses, the case was referred to the City Fiscal of

Pasay City. [Exhibit F]" 2

The judgment of conviction was based on the ndings of the trial court that

petitioner Cornejo employed criminal deceit in falsely holding himself out as duly

authorized by reason of his of ce to inspect and investigate privately-owned

buildings, by which misrepresentation he was able to inveigle complainant to

agree to have the oor area of her house and store measured and to have a plan

thereof drawn by the petitioner for a fee less than that supposedly of cially

charged for said service. cdrep

CD Technologies Asia, Inc. © 2016 cdasiaonline.com

In his main petition, petitioner contends that the respondent court

committed grave abuse of discretion in:

a] considering only that part of the testimony of the private

complainant which favored the prosecution and ignoring completely those

which exculpated the petitioner;

b] admitting in evidence Exhibit B [Certi cation of Pasay City

Engineer Jesus Reyna] without the author thereof taking the witness stand

and thereby depriving the petitioner of his constitutional right of

confrontation;

c] nding that petitioner had no authority to conduct inspection

and investigation of privately-owned buildings and in concluding that the

element of deceit was suf ciently proved to make the latter liable for estafa;

and

d] in holding that the arrest of petitioner in the afternoon of December

14, 1979 was the result of an entrapment when the prosecution evidence

clearly showed that the latter was set up by the complainant and the police.

Petitioner likewise led a supplemental petition with a special prayer for the

remand of the case to the court a quo on the ground that he was deprived of his

constitutional right to due process as 1] there was no preliminary investigation

actually conducted by the Tanodbayan Special Prosecutor; 2] the Sandiganbayan

should have granted his motion for reconsideration which is allegedly highly

meritorious; 3] the Information is utterly defective; 4] the prosecution is politically-

motivated and stage-managed to ease him out as a possible mayoralty candidate

against the son of then Pasay City Mayor Pablo Cuneta; and, 5] the pendency of

Civil Case No. 6302-P before the CFI of Rizal, Pasay City, a petition led by

petitioner to have his duties as City Public Works Supervisor de ned, constitutes a

prejudicial question to the case at bar. 3

In support of his rst contention, petitioner points to certain portions of the

testimony of the complainant Beth Chua as containing exculpatory evidence, thus:

"Q: All these 14 years, did you receive any notice from the Metro Manila

Commission requiring you to have those measurements?

A: Never.

Q: You were never approached by any person from the Metro Manila

Commission telling you that your premises needed measuring?

A: None, sir.

Q: And this is the first time there is such a thing as a Metro Manila

Commission requirement as you explained now as told to you by

Engr. Cornejo?

A: Yes, sir.

Q: So it was not for that purpose that you gave that P150.00; it was for

the services of Rogelio Alzate Cornejo who prepared for you a plan

which you testified is still in their possession, is this not correct?

A: Yes, sir.

Q: So that money was for the services of Rogelio Cornejo, as a matter of

fact, you even signed that sketch that Rogelio prepared, is this not

correct?

A: Yes, sir." 4

CD Technologies Asia, Inc. © 2016 cdasiaonline.com

and,

"Justice Kallos:

Q: But you admitted to Atty. Villa in his question that you agreed to pay

the sum of P150.00 for the preparation of a plan and sketch to this

other accused, Rogelio Alzate y Cornejo. In other words, the P150.00

which you agreed to pay was in payment of Rogelio Alzate's work in

preparing the plan?

A: I do not know whether the amount of P150.00 would go to Rogelio

Alzate because we agreed to the entire amount.

Q But the fact of the matter is that the P150.00 which you agree to pay

first was intended as payment for the preparation of the plan?

A: Yes, your Honor.

Q: And in fact, you admitted to Atty. Villa that you even signed the

sketch?

A: Yes, sir." 5

From the above testimony of complainant Beth Chua, petitioner would

conclude that the gravamen of the charge was not proved because the person

sought to be defrauded did not fall prey to the alleged fraudulent acts or

misrepresentations and that the money was in fact paid for services rendered by

Rogelio Alzate Cornejo. llcd

This conclusion drawn by petitioner is unwarranted. The testimony of

complainant Beth Chua should be taken in its entirety. Not to be overlooked is her

categorical statement that although she initially entertained doubts as to the

personality of the petitioner and the veracity of his representations, she nally

believed him because he talked nicely and also because he warned her that unless

she complied with the purported requirements of the Metro Manila Commission,

she could be liable for the penal sanctions under the Building Code. She further

stated that she believed petitioner's statement that having her store measured and

a plan thereof made would prevent her eviction from the subject premises. 6 This

portion of the testimony of Beth Chua was accorded full weight and credence by

the trial court and We nd no cogent reason to disturb such assessment,

particularly where the veracity of said statements was demonstrated by

complainant's own act of agreeing to have her store measured and a plan thereof

sketched as per advice of petitioner. Complainant had no reason to have such

work undertaken and in the process, incur expenses, other than her belief in and

reliance on petitioner's misrepresentations. Otherwise stated, if complainant did

not believe petitioner's misrepresentations, she would not have agreed to said

advice. Thus, it was precisely petitioner's misrepresentations that induced

complainant to part with her money. That actual services were performed cannot

exculpate petitioner because said services rendered were an integral part of the

modus operandi, without which petitioner would have no reason to obtain money

from the complainant. These services likewise served as a smokescreen to

prevent the complainant from realizing that she was being swindled.

Anent petitioner's objection to the admissibility of Exhibit B, the certi cation

issued by Pasay City Engineer Jesus Reyna to the effect that petitioner was not

authorized to inspect and investigate privately-owned buildings. We nd no

reversible error, much less grave abuse of discretion on the part of the trial court in

admitting the same. It must be noted that Exhibit B was not presented as an

CD Technologies Asia, Inc. © 2016 cdasiaonline.com

independent evidence to prove the want of authority of petitioner to inspect and

investigate privately-owned buildings, but merely as part of the testimony of the

complainant that such certi cation was issued in her presence and the declaration

of Assistant Pasay City Engineer Ceasar Contreras that the signature appearing

thereon was that of Engineer Reyna. Where the statement or writings attributed to

a person who is not on the witness stand are being offered not to prove the truth

of the facts stated therein but only to prove that such statements were actually

made or such writings were executed, such evidence is not covered by the hearsay

rule. 7

Besides, the nding of the trial court that petitioner had no authority to

conduct inspections and investigations of privately-owned buildings was reached,

not solely on the basis of Exhibit B, but principally from a consideration and study

of Section 18 of R.A. No. 5185, the law which rst allowed the city governments to

create the position of City Public Works Supervisor, in relation to P.D. No. 549,

which placed the city public works supervisors under the supervision of the city

engineers.

Of course, petitioner would likewise nd fault in the conclusion [third

assignment of error]. However, rather than overturn the trial court in this regard as

petitioner would pray of Us, We nd ourselves in complete agreement with the trial

court's observations and conclusion that: LLphil

". . . Easily, the authority claimed should be a matter of law or

regulation. To begin with, the position of City Public Works Supervisor, which

is admittedly the position held by accused Engineer, was rst allowed to be

created by City Governments pursuant to Section 18 of Republic Act No.

5185, which expressly con ned the functions thereof to `public works and

public highways projects nanced out of local funds'. Nowhere in that

statute was any authority granted to city public works supervisors relative to

privately-owned buildings. Later, with the advent of Presidential Decree No.

549, on September 5, 1974, city public works supervisors were placed under

the direct supervision of the City Engineer, although, by virtue of Letter of

Instruction No. 789, dated December 26, 1978, as further implemented by

Ministry Order No. 3-79, Ministry of Finance, dated January 23, 1979, the

officials therein mentioned were —

"'. . . enjoined to abolish the Of ce of the City Public Works

Supervisor, return all personnel to the Department of Engineering and

Public Works of the City without reduction in salaries, place City

Public Works Supervisors under the direct control and supervision of

City Engineers and for City Engineers to carry out all public works

constructions, repairs and improvements of the City nanced by City

Funds, pursuant to the respective charters of the Cities.'

"Clearly, then as of December, 1979, when the offense here charged is

alleged to have been perpetrated, accused Engineer's position as City Public

Works Supervisor could not have subsisted and, although he remained in

of ce, he was then placed under the direct control and supervision of the

City Engineer, performing functions con ned to `public works and public

highways projects nanced out of local funds', As such he had no authority

to conduct inspection or investigation of privately-owned buildings — a fact

duly certi ed by Pasay City Engineer Jesus L. Reyna [Exhibit B] and

con rmed on the witness stand by Pasay City Assistant City Engineer

Ceasar C. Contreras. In this posture, the basic representation of accused

Engineer that he was authorized to conduct inspection and investigation of

CD Technologies Asia, Inc. © 2016 cdasiaonline.com

privately-owned buildings was an outright falsehood.

"Accused Engineer's insistent claim that he had that authority is futile.

As aforesaid, the pertinent law is explicit that the functions of a city public

works supervisor, as the title of the of ce clearly suggests, refer only to the

supervision of public works and, for this purpose, this means 'public works

and public highways projects nanced out of local funds'. This statutory

speci cation of duties can not be varied by the mere certi cation presented

by said accused that he 'is a duly accredited employee of this Of ce [of the

City Engineer] and is entitled to all assistance and courtesies in the

performance of his duties' [Exhibit 10]. Much less could the notation under

the column 'Remarks' in his Daily Time Records [Exhibits 11, 11-A to 11-C], to

wit, 'Overseeing PW-BUILDING INVESTIGATION' or 'Bldg. Investigations', be

accorded the force of an investiture of authority for that purpose. At best,

said notations are only self-servicing statements made by said accused and

the mere fact that the daily time records aforesaid are approved by the City

Engineer cannot add an iota of probative force thereto as proof of any

authority to inspect and investigate privately-owned buildings." 8

Petitioner further attempts to convince Us that he was induced and

instigated by complainant and the police to commit the crime charged. The facts

of the case do not support such assertion. When petitioner returned to

complainant's house on the day he was arrested, he had already committed the

deceit punished by law and had effectively defrauded complainant of her money.

His act of going to complainant's house was a mere continuation of the unlawful

scheme, already consummated within the contemplation of the law, so that the

strategy employed by the police in affecting his arrest was a clear case of

entrapment, which is recognized as a lawful means of law enforcement. 9

Worthy of note is the fact that except for a eeting reference to the

pendency of Civil Case No. 6302-P of the then CFI of Rizal, Pasay City as

constituting a prejudicial question to the present prosecution, the other grounds

cited in petitioner's supplemental petition were neither discussed nor elaborated

on in his brief. Suf ce it to say then that the other grounds cited by petitioner in his

supplemental petition deserve scant consideration for they either do not have any

relevance to the petition at bar [such as petitioner's allegation that the prosecution

is politically-motivated] or could not alter the result of the case, such as

petitioner's bare allegation of lack of preliminary investigation, which cannot

overcome the presumption of regularity in the performance of of cial duties [Sec.

5(m), Rule 131, Rules of Court]; the complaint about the Information * which We do

not nd defective; and the matter of prejudicial question which must be raised

after the Information has been filed in the trial court, but not at this late stage. 1 0

Finding no reversible error nor grave abuse of discretion to have been

committed by the trial court, and convinced beyond reasonable doubt that

petitioner is guilty of the offense charged, the decision of the trial court is

affirmed.

WHEREFORE, the instant petition is hereby denied for lack of merit. The

decision of the Sandiganbayan in Criminal Case No. 2495 is af rmed en toto.

Costs against petitioner.

SO ORDERED.

Teehankee, (C.J.), Yap, Narvasa, Melencio-Herrera, Gutierrez, Jr., Cruz, Paras, Feliciano,

CD Technologies Asia, Inc. © 2016 cdasiaonline.com

Gancayco, Padilla, Bidin Sarmiento and Cortes, JJ., concur.

Footnotes

* Petitioner's co-accused Rogelio Alzate Cornejo was acquitted on the ground of reasonable

doubt.

1. p. 43, Rollo.

2. pp. 25-29, Rollo.

3. pp. 75-79, Rollo.

4. TSN, pp. 47-48, June 1, 1981.

5. TSN, pp. 50-51, June 1, 1981.

6. TSN, pp. 3-4, 5-9, 12-13, 15-16, June 1, 1981.

7. People v. Cusi, 14 SCRA 944.

8. Decision, pp. 33-35, Rollo.

9. People v. Luz Chua, et al., 56 Phil. 53.

** The Information in Criminal Case No. 2495 reads:

"That on or about the 11th day of December, 1979, in Pasay City, Philippines and within

the jurisdiction of this Honorable Court, the abovenamed accused, Engr. Alfredo Cornejo,

Sr., a public officer being then a City Public Works Supervisor of the Pasay City

Engineer's Office, and Rogelio Alzate Cornejo, a private individual, by means of deceit,

false pretenses and fraudulent manifestations, the former taking advantage of his

position and committing said offense in relation to his office, conspiring and

confederating and mutually helping and aiding one another, did then and there willfully,

unlawfully and feloniously inform and misrepresent to Beth Chua that as per instruction

of the Metro Manila Commission, the floor area of the apartment occupied by Beth Chua

has to be measured, inspected and investigated and that at the same time, structural

plan of the said apartment must be prepared, for which the latter would allegedly pay

P3.00 per square meter to the Metro Manila Commission if said work would be done by

the latter office, but if they would be the one to do the job, it would only cost P0.50 per

sq. meter, when in truth and in fact, accused Engr. Alfredo R. Cornejo, Sr., as per

certification issued by the Pasay City Engineer's Office, has no authority to conduct

inspection and investigation of privately-owned houses or buildings and accused

Rogelio Alzate Cornejo is not even connected with the Local City Engineer's Office, that

complainant Beth Chua, believing the representations of the said accused to be true, did

in fact give and deliver to the accused the total amount of P150.00 which amount

accused misappropriated and misapplied to their own use and benefit, to the damage

and prejudice of said Beth Chua in the aforesaid amount of P150.00." [pp. 24-25, Rollo].

10 . Estrella v. Orendain, et al., 37 SCRA 640; Isip, et al. v. Gonzales, 39 SCRA 255.

CD Technologies Asia, Inc. © 2016 cdasiaonline.com

You might also like

- INTENGAN Vs CADocument2 pagesINTENGAN Vs CAJoona Kis-ingNo ratings yet

- People of The Philippines vs. Danny GodoyDocument7 pagesPeople of The Philippines vs. Danny GodoyDales BatoctoyNo ratings yet

- Geraldo Vs PeopleDocument3 pagesGeraldo Vs PeopleMarlene TongsonNo ratings yet

- SALINAS, Mark Ian B. (Assignment)Document5 pagesSALINAS, Mark Ian B. (Assignment)Ukulele PrincessNo ratings yet

- (Digest) Malayan Insurance V Phil Nails & Wires CorpDocument3 pages(Digest) Malayan Insurance V Phil Nails & Wires CorpTerasha Reyes-Ferrer100% (1)

- Trans-Pacific Industrial v. CADocument1 pageTrans-Pacific Industrial v. CAKimNo ratings yet

- Hearsay Rule Exception. Dying DeclarationDocument48 pagesHearsay Rule Exception. Dying DeclarationAngeli Pauline JimenezNo ratings yet

- PEOPLE OF THE PHILIPPINES, Plaintiff-Appellee, Vs - EUTIQUIA CARMEN, Celedonia Fabie, Delia Sibonga, Alexander Sibonga, Reynario NuezDocument5 pagesPEOPLE OF THE PHILIPPINES, Plaintiff-Appellee, Vs - EUTIQUIA CARMEN, Celedonia Fabie, Delia Sibonga, Alexander Sibonga, Reynario NuezPearl Anne GumaposNo ratings yet

- Done - 11. Guingona, Jr. v. City Fiscal of Manila - 1984Document2 pagesDone - 11. Guingona, Jr. v. City Fiscal of Manila - 1984sophiaNo ratings yet

- CITY OF MANILA v. CABANGIS PDFDocument2 pagesCITY OF MANILA v. CABANGIS PDFMark Carlo YumulNo ratings yet

- People v. de JoyaDocument1 pagePeople v. de JoyalividNo ratings yet

- Arthur Zarate Vs RTCDocument2 pagesArthur Zarate Vs RTCJigo DacuaNo ratings yet

- People Vs LangcuaDocument1 pagePeople Vs LangcuaTootsie Guzma100% (1)

- R130 S33 People Vs LadaoDocument2 pagesR130 S33 People Vs LadaoOculus DecoremNo ratings yet

- Aguirre vs. People - DigestDocument2 pagesAguirre vs. People - DigestMaria Jennifer Yumul BorbonNo ratings yet

- 130 People V BasayDocument2 pages130 People V BasayJudy Ann ShengNo ratings yet

- G.R. No. 199877 August 13, 2012 PEOPLE OF THE PHILIPPINES, Plaintiff-Appellee, ARTURO LARA y ORBISTA, Accused-AppellantDocument10 pagesG.R. No. 199877 August 13, 2012 PEOPLE OF THE PHILIPPINES, Plaintiff-Appellee, ARTURO LARA y ORBISTA, Accused-AppellantBUTTERFLYNo ratings yet

- Fernandez VsDocument1 pageFernandez VsAnj MerisNo ratings yet

- Solla Vs AscuetaDocument2 pagesSolla Vs AscuetaAilyn AñanoNo ratings yet

- Heirs of Sabanpan Vs Comorposa 408 Scra 692Document2 pagesHeirs of Sabanpan Vs Comorposa 408 Scra 692Racheal SantosNo ratings yet

- Rudecon MGT Corp V Camacho 437 Scra 202Document4 pagesRudecon MGT Corp V Camacho 437 Scra 202emdi19No ratings yet

- Case Digest Case No. 5 Case No. 6Document3 pagesCase Digest Case No. 5 Case No. 6carl fuerzasNo ratings yet

- People vs. VillamarDocument5 pagesPeople vs. VillamarNash LedesmaNo ratings yet

- G.R. No. 139150 Pablo Dela Cruz Vs CADocument2 pagesG.R. No. 139150 Pablo Dela Cruz Vs CAPaul Arman MurilloNo ratings yet

- 040 Republic V SandiganbayanDocument3 pages040 Republic V SandiganbayanJudy Ann ShengNo ratings yet

- People v. YatcoDocument3 pagesPeople v. YatcoStella Marie Ad AstraNo ratings yet

- 133 Geraldo V PeopleDocument2 pages133 Geraldo V PeopleJudy Ann ShengNo ratings yet

- Lee v. Court of Appeals (G.R. No. 90423, September 6, 1991)Document1 pageLee v. Court of Appeals (G.R. No. 90423, September 6, 1991)Migs MarcosNo ratings yet

- Cleofas vs. St. Peter FinalDocument3 pagesCleofas vs. St. Peter Finalandrew estimoNo ratings yet

- 119 People v. IrangDocument2 pages119 People v. IrangPatricia Kaye O. SevillaNo ratings yet

- Auro v. YasisDocument7 pagesAuro v. YasisdenverNo ratings yet

- 36 - People V de JoyaDocument3 pages36 - People V de JoyaIra AgtingNo ratings yet

- Consumido V RosDocument1 pageConsumido V RosElaizza Concepcion0% (1)

- United States vs. Teresa Concepcion GR No. 10396 July 29, 1915Document1 pageUnited States vs. Teresa Concepcion GR No. 10396 July 29, 1915laika corralNo ratings yet

- Digest - Conde To American HomeDocument22 pagesDigest - Conde To American HomeKaye MendozaNo ratings yet

- C3h - 14 MERALCO v. QuisumbingDocument2 pagesC3h - 14 MERALCO v. QuisumbingAaron AristonNo ratings yet

- Hearsay Mallari V PeopleDocument1 pageHearsay Mallari V PeopleJeremiah John Soriano NicolasNo ratings yet

- 23 Fabia v. IACDocument2 pages23 Fabia v. IACTelle MarieNo ratings yet

- #41 Estrada v. Desierto - REYESDocument3 pages#41 Estrada v. Desierto - REYESRuby ReyesNo ratings yet

- (G.R. No. 205172. June 15, 2021) Disini DamagesDocument54 pages(G.R. No. 205172. June 15, 2021) Disini DamagesChatNo ratings yet

- People vs. BaronDocument1 pagePeople vs. BaronMACNo ratings yet

- People vs. FabonDocument13 pagesPeople vs. FabonZoe Kristeun GutierrezNo ratings yet

- RPC 1 (Cases)Document20 pagesRPC 1 (Cases)ZL ZLNo ratings yet

- Repubic Vs Development Resources CorpDocument2 pagesRepubic Vs Development Resources CorpVince Llamazares LupangoNo ratings yet

- Magdayao v. PeopleDocument1 pageMagdayao v. PeopleRomela Eleria GasesNo ratings yet

- People V Estibal G.R. No. 208749Document15 pagesPeople V Estibal G.R. No. 208749Jade Palace TribezNo ratings yet

- Miranda V PDICDocument3 pagesMiranda V PDICJennyNo ratings yet

- EVID (First 5 Digests)Document14 pagesEVID (First 5 Digests)doraemonNo ratings yet

- 32 - Commonweath Act 142, RA 6085Document1 page32 - Commonweath Act 142, RA 6085Regina CoeliNo ratings yet

- People v. DunigDocument9 pagesPeople v. DunigAstrid Gopo BrissonNo ratings yet

- Laragan Vs CADocument1 pageLaragan Vs CAGillian Caye Geniza BrionesNo ratings yet

- 004 People Vs YatcoDocument3 pages004 People Vs YatcoEric TamayoNo ratings yet

- Sps. Dato v. Bank of The Philippine IslandDocument10 pagesSps. Dato v. Bank of The Philippine IslandSamuel John CahimatNo ratings yet

- Zafra Vs PeopleDocument3 pagesZafra Vs PeopleRobertNo ratings yet

- Case #10 Mallilin V. People G.R. No. 172953Document4 pagesCase #10 Mallilin V. People G.R. No. 172953Carmel Grace KiwasNo ratings yet

- People v. Queriza, 279 SCRA 145 (1997)Document13 pagesPeople v. Queriza, 279 SCRA 145 (1997)GioNo ratings yet

- G.R. Nos. 90191-96 January 28, 1991 PEOPLE OF THE PHILIPPINES, Plaintiff-Appellee, Anacleto FuruggananDocument21 pagesG.R. Nos. 90191-96 January 28, 1991 PEOPLE OF THE PHILIPPINES, Plaintiff-Appellee, Anacleto FuruggananJoyleen HebronNo ratings yet

- Sugar Regulatory Administration vs. TormonDocument1 pageSugar Regulatory Administration vs. TormonMaria Florida ParaanNo ratings yet

- Petitioner vs. vs. Respondent: en BancDocument8 pagesPetitioner vs. vs. Respondent: en BancClarence ProtacioNo ratings yet

- Custom Search: Today Is Wednesday, February 21, 2018Document5 pagesCustom Search: Today Is Wednesday, February 21, 2018Marchini Sandro Cañizares KongNo ratings yet

- AKBAYAN Vs AQUINO DigestDocument2 pagesAKBAYAN Vs AQUINO DigestElla PerezNo ratings yet

- 47 - Municipality of San Fernando Vs Judge Firme DigestDocument2 pages47 - Municipality of San Fernando Vs Judge Firme DigestElla PerezNo ratings yet

- 3-Pamatong Vs COMELECDocument3 pages3-Pamatong Vs COMELECElla PerezNo ratings yet

- Robles v. HermanosDocument8 pagesRobles v. HermanosElla PerezNo ratings yet

- 17-Enrile vs. Senate of Electoral Tribunal DigestDocument2 pages17-Enrile vs. Senate of Electoral Tribunal DigestElla PerezNo ratings yet

- Reyes V BagatsingDocument16 pagesReyes V BagatsingElla PerezNo ratings yet

- Rodriguez v. Macapagal-ArroyoDocument28 pagesRodriguez v. Macapagal-ArroyoElla PerezNo ratings yet

- F. Gonzales Vs PeopleDocument6 pagesF. Gonzales Vs PeopleElla PerezNo ratings yet

- B. Ariate Vs PPDocument9 pagesB. Ariate Vs PPElla PerezNo ratings yet

- C. Parel Vs PrudencioDocument14 pagesC. Parel Vs PrudencioElla PerezNo ratings yet

- Appeals Court Upholds Conviction of John HaggertyDocument67 pagesAppeals Court Upholds Conviction of John Haggertyliz_benjamin6490No ratings yet

- Consti Law 2 Reviewer Sec 12 To 14Document2 pagesConsti Law 2 Reviewer Sec 12 To 14May Angelica TenezaNo ratings yet

- Cat WalkDocument36 pagesCat WalkAmir HamdzahNo ratings yet

- Arrests, Inquest, Pi, SearchDocument43 pagesArrests, Inquest, Pi, SearchAsiongNo ratings yet

- Affidavit of ClarificationDocument2 pagesAffidavit of Clarificationmarvin dalayapNo ratings yet

- Tible Digest Remedial Law - Docx FinalDocument3 pagesTible Digest Remedial Law - Docx FinalKim Roque-AquinoNo ratings yet

- Roman Motion To Dimiss 010824Document127 pagesRoman Motion To Dimiss 010824Liberty NationNo ratings yet

- To Be Presumed Innocent Until The Contrary Is Proved Beyond Reasonable DoubtDocument4 pagesTo Be Presumed Innocent Until The Contrary Is Proved Beyond Reasonable DoubtVillar John EzraNo ratings yet

- People Vs BasquezDocument3 pagesPeople Vs Basqueztorralba.nash.amethystNo ratings yet

- The Case of Hubert WebDocument2 pagesThe Case of Hubert WebKABACAN BFP12No ratings yet

- 4.carreon vs. Agcaoili DigestDocument2 pages4.carreon vs. Agcaoili DigestCaroline A. LegaspinoNo ratings yet

- Constitution of Criminal CourtsDocument35 pagesConstitution of Criminal CourtsCANNo ratings yet

- 2011.09.30 Motion - To - Correct The Supplemental RecordDocument12 pages2011.09.30 Motion - To - Correct The Supplemental RecordElisa Scribner LoweNo ratings yet

- People of The Philippines vs. Hon. Mariano CastanedaDocument2 pagesPeople of The Philippines vs. Hon. Mariano CastanedaMmm GggNo ratings yet

- People V TulinDocument2 pagesPeople V TulinJerico Godoy100% (1)

- Right Against Self-IncriminationDocument1 pageRight Against Self-IncriminationlmafNo ratings yet

- Sharia Courts CasesDocument14 pagesSharia Courts CasesLou StellarNo ratings yet

- CLJ 106 QuizDocument2 pagesCLJ 106 QuizFlores JoevinNo ratings yet

- Land Acquisition Act 1894Document2 pagesLand Acquisition Act 1894Bidisha GhoshalNo ratings yet

- Metropolitan Bank and Trust Comp. v. Absolute Management Corp.Document8 pagesMetropolitan Bank and Trust Comp. v. Absolute Management Corp.Romar John M. GadotNo ratings yet

- 118 Balila v. IACDocument1 page118 Balila v. IACJoshua Alexander CalaguasNo ratings yet

- Basic Legal GlossaryDocument14 pagesBasic Legal GlossaryDale GilmartinNo ratings yet

- Bimeda Vs PerezDocument5 pagesBimeda Vs PerezAnjNo ratings yet

- Mayes Et Al v. Sportsstuff, Inc. Et Al - Document No. 2Document2 pagesMayes Et Al v. Sportsstuff, Inc. Et Al - Document No. 2Justia.comNo ratings yet

- Republic of The Philippines Cagayan State University College of Law Andrews Campus, Tuguegarao City, Cagayan Evidence Final Examination (Part I)Document6 pagesRepublic of The Philippines Cagayan State University College of Law Andrews Campus, Tuguegarao City, Cagayan Evidence Final Examination (Part I)Mikes FloresNo ratings yet

- TJoinDocument4 pagesTJoinHollyRustonNo ratings yet

- Surrender PetitionDocument2 pagesSurrender PetitionAdityaNo ratings yet

- PAT Compromise Agreement Cases Full TextDocument33 pagesPAT Compromise Agreement Cases Full TextLea NajeraNo ratings yet

- Allgemaine Vs Metrobank Case DigestDocument2 pagesAllgemaine Vs Metrobank Case Digestkikhay11No ratings yet

- US vs. KieneDocument2 pagesUS vs. Kieneerlaine_franciscoNo ratings yet