Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Project Evaluation Systematics PDF

Project Evaluation Systematics PDF

Uploaded by

Sergio Eduardo Silva Diaz0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

11 views49 pagesOriginal Title

PROJECT EVALUATION SYSTEMATICS.pdf

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

PDF or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF or read online from Scribd

Download as pdf

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

11 views49 pagesProject Evaluation Systematics PDF

Project Evaluation Systematics PDF

Uploaded by

Sergio Eduardo Silva DiazCopyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF or read online from Scribd

Download as pdf

You are on page 1of 49

SYSTEMATICS

We are now ready to tum our attention to the principal theme, that of project

evaluation. The first two chapters were in the nature of a prelude, an introduction

that hopefully contributed to the student's perception of the nature of the industrial

environment, and that additionally laid down a mathematical foundation for some

of the evaluation techniques which will follow. In this chapter we return to the

concept, initially explored during our cursory review of the economic basis of

industrial projects (Sec. 1.3), of project economic analysis as a blending of invest-

ment and income analyses pointing toward the examination of a criterion of eco-

nomic performance. We will examine the preferred sequencing of such an eco-

nomic analysis as a first step leading to a more detailed exposition of methodology

in subsequent chapters. We will also examine methods of assembling background

information required for the proper definition of the nature of the project. Specifi-

cally, we will explore ways of making product pricing and demand projections by

using the techniques of marketing research, and we will also examine some of the

ways of defining a processing scheme that can serve as a basis for subsequent

investment and income analyses.

The differences among various project types will be pointed out, but the exposi-

tion of project evaluation systematics will emphasize those aspects which are

common to all projects.

3.1 PRINCIPLES OF PRELIMINARY PROJECT EVALUATION.

Project Types: Similarities and Differences

No two projects are alike. Each one differs in nature and scope, and each one

Presents its own set of challenges. And yet, as we attempt to evaluate projects to

122

SECTION 3.1: PRINCIPLES OF PRELIMINARY PROJECT EVALUATION 123.

establish their economic promise, we find that the mechanism of evaluation has a

number of elements, as well as sequencing of elements, most of which are common

to each project regardless of the project’s nature.

Even one particular project changes in nature in the course of project devel-

opment. For example, the overall process to manufacture a particular product,

spanning the gamut from raw material preparation to final product purification, may

change in such a way as to be virtually unrecognizable during its progress from the

laboratory bench to the pilot plant. We begin by focusing upon project evaluation

at the preliminary stage of development. By prefiminary stage we refer to the stage

of a project when it is still in the laboratory, the product preparation appears to be

technically feasible, and the product itself holds promise of more than casual

acceptance in the world of commerce. We will find that these preliminary-stage

techniques and sequences can be used throughout the lifetime of a project, through-

out the various stages of project development and “fine-tuning,” perhaps with some

refinements. We emphasized in the first chapter that the decision as to when

refinements and more thorough evaluation techniques are to be used is primarily a

matter of judgment and experience. We should perhaps emphasize again that

project evaluation must be attempted at the earliest possible stages of development,

Just as soon as some processing scheme can be visualized, to avoid catastrophic

development expenditures on a project with a dismal economic prospect.

The nature and scope of a project are distinctly influenced by the history of the

product in the corporation, and a product-oriented project classification is a useful

one:

Existing products in company. These projects involve new plants to manufacture

an existing company product on an existing site (for example, to expand production

capacity), new plants in new locations, and plants to produce an existing product

but utilizing a new process.

Existing products but new to company. Even though a great deal of information

may be available on the existing products, the very fact that they are new to the

company increases the complexity of this type of project.

Entirely new products. These projects involve the greatest number of unknowns

and are therefore the most difficult to handle.

Limited-scope projects. There are, of course, those projects which do not really

fit into any of the previous categories, principally because of their limited scope.

‘These include (1) existing plant changes and improvements and (2) pilot plant arid

semiplant projects.

Sequence of Preliminary Project Evaluation

‘The following steps describe the normal sequence used during preliminary project

evaluation. Ay the project progresses toward more advanced stages of develop-

Ment, one OF Another of the sequential items may receive special emphasis, but the

total sequence should be kept up-to-date; it applies to projects up to the stage of

g research

sell at what price?”

3 Process choice. For a new product, this step may be more a matter of process

definition rather than process choice.

4 Flow sheet synthesis, material and energy balances. In preliminary stages,

flow sheet synthesis may involve a great deal of speculation.

5 Equipment choice and design. Shortcut methods or rules of thumb are partic-

ularly useful in preliminary stages.

6 Plant investment estimate. Estimate of the capital required to build a plant to

meet the likely demand.

7 Manufacturing cost estimate. Projection of how much it will cost to produce

the product in the specified plant.

8 Profitability evaluation. Project profitability based upon a chosen criterion of

economic performance.

Some of the sequence items will constitute the subject matter of separate chap-

ters.

Follow-up Evaluation

The product and process development which characterize successive stages of a

project do not occur as quantum jumps but rather as a developmental continuum.

Nevertheless, discrete states of advancement may be approximately identified and

described on the basis of firmness of process, degree of backup toxicological work,

scale-up status, and many other criteria. Often the stages of development are

formally described and numerically identified, although the methodology differs

among corporations. One may speak, for example, about a stage 0 or a stage 1

project, the latter corresponding perhaps to the preliminary stage previously de-

scribed. Projects may also be identified by reference to the status of the corre-

sponding capital investment estimate. In Chap. 1, four estimate categories were

identified. These estimate categories are sometimes characterized as “class levels”

IV (order-of-magnitude) down to I (project control) (Maples and Hyland, 1980).

A project development sequence may be described in terms of a few develop-

mental landmarks:

* Laboratory development work

Definition of desirable product characteristics.

Measurement of physical properties.

Reaction definition, usually batch reaction, often in glass equipment.

Separation studies in laboratory equipment.

Purification studies.

Satellite studies: toxicology, product performance, safe handling, waste

disposal.

You might also like

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5822)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1093)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (852)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (590)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (898)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (540)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (349)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (822)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (122)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (403)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- Términos de Referencia Informe Diseño de Proceso 2018-2Document17 pagesTérminos de Referencia Informe Diseño de Proceso 2018-2Sergio Eduardo Silva DiazNo ratings yet

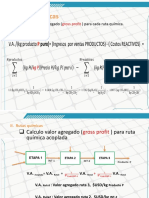

- Selección Ruta Química y Valor AgregadoDocument4 pagesSelección Ruta Química y Valor AgregadoSergio Eduardo Silva DiazNo ratings yet

- Selección Ruta Química y Valor AgregadoDocument4 pagesSelección Ruta Química y Valor AgregadoSergio Eduardo Silva DiazNo ratings yet

- Preguntas SergioDocument4 pagesPreguntas SergioSergio Eduardo Silva DiazNo ratings yet