Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Mobile Phones As Fashion Statements: Evidence From Student Surveys in The US and Japan

Mobile Phones As Fashion Statements: Evidence From Student Surveys in The US and Japan

Uploaded by

RanjanaOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Mobile Phones As Fashion Statements: Evidence From Student Surveys in The US and Japan

Mobile Phones As Fashion Statements: Evidence From Student Surveys in The US and Japan

Uploaded by

RanjanaCopyright:

Available Formats

........................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................

new media & society

Copyright © 2006 SAGE Publications

London, Thousand Oaks, CA and New Delhi

Vol8(2):321–337 [DOI: 10.1177/1461444806061950]

ARTICLE

Mobile phones as fashion

statements: evidence from

student surveys in the US

and Japan

............................................................................................................................................................................................................................................

JAMES E. KATZ

SATOMI SUGIYAMA

Rutgers University, USA

............................................................................................................................................................................................................................................

Abstract

Motivated by new theoretical perspectives that emphasize

communication technology as a symbolic tool and physical

extension of the human body and persona (Apparatgeist

theory and Machines That Become Us), this article explores

how fashion, as a symbolic form of communication, is

related to self-reports of mobile phone behaviors across

diverse cultures. A survey of college students in the United

States and Japan was conducted to demonstrate empirically

the relationship between fashion attentiveness and the

acquisition, use, and replacement of the mobile phone.

The results suggested that young people use the mobile

phone as a way of expressing their sense of self and

perceive others through a ‘fashion’ lens. Hence it may be

useful to investigate further how fashion considerations

could guide both the rapidly growing area of mobile

phone behavior, as well as human communication

behavior more generally.

Key words

fashion • Japan • mobile phone • technology • United

States

321

Downloaded from nms.sagepub.com at PENNSYLVANIA STATE UNIV on March 6, 2016

New Media & Society 8(2)

RATIONALE OF THE PROBLEM

Traditionally, scholarly analysis of the social aspects of communication

technology has emphasized how the technology can solve people’s problems

and needs. Models such as the ‘uses and gratifications’ model developed by

Katz et al. (1974) have become classics in the field of mass media. Even

after a half of a century, the theory continues to exert influence not only

over traditional media analyses but also over traditional and new

interpersonal mediated communication technologies. These include such

technologies as the landline telephone (Dimmick et al., 1994) and the

mobile phone (Leung and Wei, 2000). A large body of research has now

accumulated about how people perceive specific tangible benefits from their

technologies of communication (see Katz, 1999 for an overview).

However, the role that a given technology plays in communicative

activities is not only a matter of its function. As Katz and Aakhus (2002)

noted, people do not look to ‘intrusive technology’ as an answer for

problems or needs in their daily routine. The technological function of a

new tool is not necessarily the most important consideration when people

decide whether to adopt it. People do not always adopt a tool just because

it improves communication or eases a task. Added to this is the

consideration that, even when there is little change in the basic technology

and concept of a tool, people still seem to seek new devices that build on

that technology in a fresh way. This gap brings our attention to the question

of why people decide to adopt technology in their life. If it is not simply to

make daily life more convenient, why do they like to incorporate it into

their routine? This question suggests that it is important to explore other

communicative roles that technology plays in our life.

Domestication theory advanced by Roger Silverstone and Leslie Haddon

is relevant to considering our question since it draws attention to the

symbolic nature of goods (Haddon, 2003). This perspective is valuable in

understanding the degree to which this once bulky, expensive business tool

has become a personal technology, integrated into our bodies and fashion

sense, and thus domesticated. However, domestication alone seems to be

insufficient to account for the important and dynamic role that the

technology and its appearance plays in people’s lives. The mobile phone is

not disappearing from the public sphere. Rather it is intruding ever more, as

a device upon which social identity is created and expressed within people’s

domestic intellectual domain.

As a way of overcoming the limitation of the domestication perspective,

we propose to consider ‘fashion’ as a motive that guides how people use the

mobile phone (see Fortunati, 2002 for more discussion on fashion and

communication technologies). According to Katz and Aakhus (2002),

mobile communication technologies are both utilitarian and symbolic.

The symbolic aspect has been gaining attention as a movement toward

322

Downloaded from nms.sagepub.com at PENNSYLVANIA STATE UNIV on March 6, 2016

Katz and Sugiyama: Mobile phones as fashion statements

‘understanding the body in relationship to machinery, symbolism, the arts,

and fashion’ (Katz, 2003: 16–17). This suggests that considering the

symbolic aspect of the mobile phone by focusing on the role of ‘fashion’ in

our everyday life could be one way of understanding how people use

mobile communication technology in social contexts.

Fashion is an area rich in communicative information about the self.

People use it not only to express their identity but to perceive and

understand others (e.g. Crane, 2000; Davis, 1985, 1992; Kaiser, 1997;

Rubinstein, 2001; Simmel, 1904, 1950; Steele, 1997). How the symbolic

interaction perspective is incorporated into the theoretical discussion of

fashion also suggests the potential relevance of fashion to the mobile phone.

Furthermore, Crane argues that fashion plays a central role in the

determination of the meanings of cultural goods:

[T]o understand contemporary societies, we need to pay more attention to

how meanings for cultural goods are produced, by whom, and in what

contexts; to how widely specific sets of meanings embodied in particular types

of cultural goods circulate; and to the nature of the public spaces in which

they diffuse. (Crane, 2000: 248)

These arguments lead us to think that fashion is an important form of

symbolic communication that could drive human behavior. Therefore, as an

aid to understanding the way in which people use the mobile phone, it is

meaningful to consider the relationship between fashion and the mobile

phone.

FASHION AND THE MOBILE PHONE

Davis (1985) discusses the ambivalent feelings that people experience about

fashion. According to him, such ambivalence includes ‘the subjective tension

of youth versus age, masculinity versus femininity, androgyny versus

singularity, inclusiveness versus exclusiveness, work versus play, domesticity

versus worldliness, revelation versus concealment, license versus restraint, and

conformity versus rebellion’ (1985: 24–5). These binary tensions are likely to

occur when people situate their ‘self ’ within certain social groups. Kaiser

(1997) notes that the identity ambivalence is especially evident in many

cultures today where society and fashion change rapidly. This, in turn,

suggests that ambivalence related to fashion stems from people’s emotional

need to keep abreast of fashion changes in order to maintain their

social identity. This ambivalence fosters people’s attentiveness toward

fashion changes.

It is within this fast-changing fashion environment in the modern world

that technologies have been adopted as accessories in our presentation of

323

Downloaded from nms.sagepub.com at PENNSYLVANIA STATE UNIV on March 6, 2016

New Media & Society 8(2)

self, and thus incorporated into a repertoire of the ‘personal front’

(Goffman, 1959). The way that people select the design and brand of

wristwatches is a good example; such a phenomenon seems to have

extended to the way that people select their mobile phones.

There is an increasing attention to fashion and technology as an

outgrowth of the growing interest in the sociology of the body. The topics

include the way in which technology is incorporated into clothing and

displayed upon the body (Fortunati, 2002). Fortunati considered the mobile

phone’s social implications in Italy, focusing on its aesthetic dimension. She

attributes its success to its ‘fashionableness’. Consequently, she argues, the

mobile phone has become a ‘necessary accessory’ (2002: 54). She also points

out that the mobile was associated with the upper classes in Italian society

until quite recently. Thus, according to Fortunati, ‘the mobile is an accessory

that enriches those who wear it, because it shows just how much they are

the object of communicative interest, and are thereby desired, on the part of

others’ (2002: 54). Fortunati’s argument suggests an interesting point that

mobile phone ownership and its use communicate ‘about’ the person. This

leads us to think of the mobile phone not only as a tool to ‘talk’ but also as

a means to communicate symbolically about oneself. The mobile phone

influences how people perceive others as well as whether people would

hope to form a personal relationship, and in turn it influences how people

decide to incorporate the mobile phone into their self images.

A similar phenomenon is reported in the case of Norway. Ling and Yttri

(2002) introduced ‘Hyper-coordination theory’, which concerns the

symbolic aspect of the mobile phone in addition to its functional and

instrumental aspects. According to Ling and Yttri, hyper-coordination adds

two dimensions to instrumental coordination: ‘the expressive use of the

mobile telephone’ and ‘in-group discussion and agreement about the proper

forms of self-presentation vis-à-vis the mobile telephone’ (2002: 140). The

expressive use of the mobile phone refers to emotional and social

communication, such as a chat with one’s friends. The proper forms of self-

presentation refer to ‘the type of mobile phone that is appropriate, the way

in which it is carried on the body and the places in which it is used’ (2002:

140). In their report of interviews with Norwegian teenagers, they make a

point of noting how teenagers see functionality as a secondary consideration

by quoting how a 17-year-old talked about a big unfashionable phone. Ling

and Yttri report that having the correct style and type of device is a vital

point in self-presentation for teenagers.

Fortunati also argues the importance of ‘how to use’ mobile phones to

look ‘appropriate’, and consequently, ‘fashionable’. She states that, on the

one hand, knowing how to use the mobile with ease gives users prestige; on

the other hand, using it indiscreetly or with anxiety of continual contact is

324

Downloaded from nms.sagepub.com at PENNSYLVANIA STATE UNIV on March 6, 2016

Katz and Sugiyama: Mobile phones as fashion statements

considered vulgar (Fortunati, 2002). This suggests that mobile phone

ownership is not sufficient when considering the ‘fashionableness’ of the

mobile phone. The way that people use their phone is an important aspect

that influences others’ perception of ‘fashionableness’.

APPARATGEIST THEORY

With the emerging importance of the question of the social consequences of

personal communication technology, Katz and Aakhus (2002) created

‘Apparatgeist theory’, which attempts to explain a form of communication

mediated through personal technologies. ‘Apparatgeist’ suggests ‘the spirit of

the machine that influences both the designs of the technology as well as the

initial and subsequent significance accorded them by users, non-users and

anti-users’ (2002: 305). The theory intends to overcome the limitations of

functionalist and structuration theories by drawing attention to such issues as

the way that people use mobile technologies as tools in their daily life in terms

of tool-using behavior and the relationship among technology, body and social

role [and] the rhetoric and meaning-making that occur via social interaction

among users (and non-users). (2002: 315)

In other words, Apparatgeist theory argues that users, non-users and anti-

users of technology, as well as those who use it in different ways, assign

different meanings to it. Consequently, it poses the question of what kinds

of meanings are assigned to them, and by whom.

In considering this question, it is important to draw attention to the use

of communication tools in the context of group membership and social

identity (Katz, 2003). In discussing fashion and culture, Kaiser states that

people bring their own ways of perceiving others’ appearances, and culture

plays a role in forming their ‘lenses’ (1997: 550). Hence it is useful to

compare different cultures in exploring the symbolic meanings of personal

communication technology. Although research on the mobile phone and

fashion based on a specific cultural context is growing (e.g. Fortunati, 2002;

Green, 2003; Kasesniemi and Rautiainen, 2002; Ling and Yttri, 2002),

comparative studies among different cultures still seems to be scarce. In

particular, cultures which are traditionally considered ‘different’ according to

various social values and behaviors have not been well examined yet.

RESEARCH QUESTIONS

Given the growing importance of the mobile phone in relation to fashion as

well as the lack of sufficient comparative study in the issue, we

systematically explore the following research questions:

325

Downloaded from nms.sagepub.com at PENNSYLVANIA STATE UNIV on March 6, 2016

New Media & Society 8(2)

RQ1: How can we understand the role of fashion in mobile phone behavior?

RQ2: Is culture important in understanding mobile communication?

The first research question is often explored by means of ethnographic

research, but this has not been examined based on statistical data. Therefore

we developed a scale for ‘fashion attentiveness’, and explored the relationship

between fashion attentiveness and various behaviors related to the mobile

phone.

Regarding the second research question, we attempt to challenge the

typical argument that emphasizes cultural ‘differences’. Katz et al. (2003)

conducted a comparative study on the perceptions of the mobile phone in

Korea and the US. Based on the findings, accompanied with some data

from Namibia and Norway, they speculate that there appear to be noticeable

‘consistencies’ as well as differences across the cultures examined in terms of

the image of the mobile phone, including ‘style’ and ‘fashion’ considerations.

Our second research question serves as a follow-up of this hypothesis,

focusing specifically on the concept of ‘fashion’. For this purpose, the

comparison between the US and Japan is appropriate because traditionally

they are considered as different in various aspects, such as the individualism–

collectivism discussed by Hofstede (1980, 1991). Hall (1976) also

characterizes these two cultures as different using high-context versus low-

context dimensions. These suggest that the Americans and Japanese are quite

divergent in terms of the way that they express themselves, and this

divergence could be extended to the way in which they communicate

through fashion. However, these two cultures are similar in containing a

large number of early technology adopters. Thus the US and Japan provides

a worthwhile comparison for considering the role of fashion in mobile

phone behavior.

Young people were selected to be the focus of this study, given the nature

of our research topic. Numerous scholars pay special attention to the way in

which young people use mobile phones (e.g. Kasesniemi and Rautiainen,

2002; Ling and Yttri, 2002; Skog, 2002). Green argues that young people

negotiate the social and cultural values of the mobile phone ‘in relation to

identity, difference, independence, and interdependence’ (2003: 213). As a

result, she argues, they have established ‘patterns’ of meanings and use, but

at the same time there is also a significant ‘diversity’ among young people.

She points out that there are some young people who are not enthusiastic

about consumption of the mobile phone. This argument theoretically

supports the idea of exploring differences among young people, rather than

treating them as one group. In addition, focusing on young people (in this

study, college students) allows us to keep factors such as age group and

status constant when examining the proposed research questions.

326

Downloaded from nms.sagepub.com at PENNSYLVANIA STATE UNIV on March 6, 2016

Katz and Sugiyama: Mobile phones as fashion statements

DATA

US data source

Given the apparently significant role of fashion in the symbolic aspects of

communication, we developed a scale to assess fashion attentiveness. A

survey questionnaire was administered in a communication class of a US

university in autumn 2001. Of the students, 305 filled out the questionnaire.

Following the approach recommended by Pedhazur and Schmelkin (1991),

factor analysis was used to develop a scale. As a result, 10 items were

selected, including ‘I try to keep up with fashion changes’ and ‘I check out

fashion magazines’. The scale assesses how much people pay attention to

new fashion trends. A five-point Likert scale was used, with 5 = strongly

agree and 1 = strongly disagree. The fashion attentiveness scale yielded

alpha = .89 reliability.

Using this scale (with the addition of two more items that conceptually

fit it) and other questions regarding the mobile phone, a follow-up survey

was conducted in spring 2002. A total of 269 students in an introductory

communication course at a large state university in the northeastern US

filled out the questionnaire. Cases with more than two missing or

implausible values were omitted from the analysis to maximize accuracy. As

a result of this process, a total of 254 cases remained (161 female, 93 male).

Over 95 percent were 18–21 years old. As for ethnic or geographical

background, 23.6 percent were Asian or Pacific Islander, 15.4 percent were

black/African-American/Caribbean, 5.1 percent were Latino/Hispanic/Latin

American, 2.8 percent were Middle Eastern and 52.8 percent were white/

European-American.1 Factor analysis confirmed that the fashion

attentiveness scale was unidimensional. Reliability alpha score on the fashion

attentiveness scale was .90.

Questions to assess mobile phone behavior included: the timing of mobile

phone adoption (more than six years ago, four to five years ago, two to

three years ago, less than one year ago, no phone); frequency of mobile

phone use (heavily, regularly, occasionally, seldom, never); and frequency of

changing the mobile phone (more than three times, twice, once, never, no

phone). In addition, questions regarding the phone’s fashionable image were

asked. For the timing of mobile phone adoption, only a few people said

that they adopted it ‘more than six years ago’, so this category was

combined with ‘four to five years ago’ and labeled ‘more than four

years ago’.

Japanese data source

The survey was translated into Japanese by two bilinguals and administered

in a university located in Tokyo area. Of the Japanese participants, 251

students from a media studies course and research methods course at a

private university in the Tokyo area filled out the questionnaire in spring

327

Downloaded from nms.sagepub.com at PENNSYLVANIA STATE UNIV on March 6, 2016

New Media & Society 8(2)

2002. Consistent with the US dataset process, cases with more than two

missing or implausible values were deleted to obtain accuracy. As a result of

this process, a total of 236 cases remained (79 female, 156 male, one non-

specified). Again, over 95 percent were 18–21 years old, and more than 98

percent of the respondents were born in Japan. The reliability alpha score

for the fashion attentiveness of the Japanese sample was compatible with the

US sample, namely .89.

RESULTS

The data were analyzed with Statistical Package for the Social Sciences

(SPSS) Version 10. We acknowledge that our samples are not representative

of the general population of youth in the US or Japan. Our statistical

analyses are for descriptive purposes, as well as to form a foundation for

theorizing and further testing. The reported significance levels should not be

interpreted as parametric statistics, but rather as a description of potential

relationships among variables in this dataset.

Fashion attentiveness and mobile phone: related?

The mean scores of fashion attentiveness by mobile phone behavior are

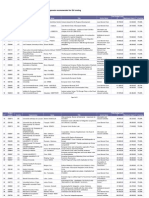

presented in Table 1.

Both the US and Japanese data indicated a similar trend: the more

attentive people were to fashion, the earlier they reported having started

using a mobile phone (F = 5.06, p < .01 for the US sample; F = 7.88,

p < .01 for the Japanese sample).

Regarding fashion attentiveness and changing their mobile phones, the

data indicated that the more attentive they were to fashion, the more

frequently young people changed their mobile phones. Again, this held for

both the US and Japan. The differences were both significant (F = 3.96,

p < .01 for the US sample; F = 7.45, p < .01 for the Japanese sample).

The data also indicated that in both the US and the Japanese samples, heavy

mobile phone users tended to be more attentive to fashion. This trend has

been found repeatedly in the follow-up surveys in the US (autumn 2002,

spring 2003) with similar sample groups.

The samples were catagorized into four groups depending on their

adoption timing and frequency of use in order to explore further the

relationship among the variables. As Figure 1 shows, those in both cultures

who were in the early adoption/heavy use category seemed to be the most

fashion attentive.

Overall, these results suggest that fashion-attentive youths are keen to try

new mobile communication technology and are willing to adopt it, use it

often and are more likely to trade it in for newer models. Thus the data

suggest that fashion attentiveness seems to be an important factor in

predicting how youths use new mobile communication technology.

328

Downloaded from nms.sagepub.com at PENNSYLVANIA STATE UNIV on March 6, 2016

Katz and Sugiyama: Mobile phones as fashion statements

• Table 1 Means of fashion attentiveness by mobile phone behaviors

US JAPAN

MEAN (SD) MEAN (SD)

Adoption +4 years ago 47.58 (10.78) 35.21 (9.56)

N = 40 N = 99

2–3 years ago 47.17 (7.93) 31.03 (8.92)

N = 115 N = 102

< 1 years ago 43.29 (9.13) 28.68 (11.70)

N = 62 N = 19

No phone 42.05 (9.96) 25.19 (7.16)

N = 37 N = 16

Use Heavily 50.37 (9.20) 34.97 (9.42)

N = 27 N = 87

Regularly 47.46 (7.56) 31.82 (9.23)

N = 89 N = 67

Occasionally 43.60 (8.04) 30.73 (9.90)

N = 50 N = 45

Seldom 44.04 (11.23) 26.45 (8.43)

N = 45 N = 22

Never 42.37 (9.72) 30.67 (11.01)

N = 43 N = 15

Change + 3 times 50.57 (7.65) 35.35 (9.39)

N = 14 N = 40

Twice 47.95 (7.86) 35.10 (8.92)

N = 38 N = 42

Once 46.60 (8.53) 32.99 (9.42)

N = 90 N = 93

Never 43.58 (9.80) 27.37 (9.62)

N = 77 N = 49

No phone 42.51 (10.09) 25.17 (6.34)

N = 35 N = 12

Is the mobile phone fashionable?

To understand how young people see the mobile phone in society, we used

the following two statements:

(1) Fashionable people use mobile phones more than other people.

(2) Some people get a mobile phone just because it is fashionable.

As Figures 2 and 3 reveal, heavier mobile phone users were less likely to

associate the mobile phone with fashionable people than non or less

frequent mobile phone users did for both cultures.

Is the style of the mobile phone important?

Although those who use a mobile phone frequently do not consider it as a

technology for the fashionable, they are in fact quite conscious of the style

characteristics of their own mobile phone. In addition, those who adopted

329

Downloaded from nms.sagepub.com at PENNSYLVANIA STATE UNIV on March 6, 2016

New Media & Society 8(2)

55

US Japan

50

Fashion attentiveness (mean)

45

40

35

30

25

20

15

10

0

Late adopt/ Late adopt/ Early adopt/ Early adopt/

light use heavy use light use heavy use

• Figure 1 Fashion attentiveness by adoption/use

3.0

2.9

US

2.8 Japan

Fashionable image

2.7

2.6

2.5

2.4

2.3

2.2

2.1

2.0

No MP Seldom Occasionally Regularly Heavily

N =254 for US, N=236 for Japan

• Figure 2 ‘Fashionable people use the mobile phone more than other people’ by mobile

phone use

330

Downloaded from nms.sagepub.com at PENNSYLVANIA STATE UNIV on March 6, 2016

Katz and Sugiyama: Mobile phones as fashion statements

4.0

3.8 US

Japan

3.6

Fashionable image

3.4

3.2

3.0

2.8

2.6

2.4

2.2

2.0

No phone Seldom Occasionally Regularly Heavily

N = 254 for US, N =236 for Japan

• Figure 3 ‘Some people get a mobile phone just because it is fashionable’ by mobile phone

use

mobile phones earlier were more likely to think that the style of the phone

would be an important factor in selecting their own phone (Figure 4). In

the same way, in both cultures, those who changed their mobile phone

more frequently seemed to be more conscious of the style of their mobile

phone.

Perceptions of the importance of style were compared further with

perceptions of the importance of battery life. Battery life is a relatively

straightforward functional aspect of the mobile phone. Yet for both the US

and Japanese respondents, heavy users valued style more than non-users or

light users (Figures 5 and 6). Moreover, Japanese heavy users even preferred

style over battery life. This latter point is particularly revealing since it flies

in the face of functional logic, which would suggest that heavy users would

put a premium on long battery life.

DISCUSSION

The results support the perspective that ‘fashion’ plays a significant role in

mobile phone adoption and usage behavior among the US and Japanese

youths. It seems that the degree of attentiveness to fashion is relevant to the

timing of adopting a mobile phone, frequency of use and frequency of

changing to a newer model. These findings support the existing research on

fashion and the mobile phone discussed earlier.

331

Downloaded from nms.sagepub.com at PENNSYLVANIA STATE UNIV on March 6, 2016

New Media & Society 8(2)

4.1

4.0

3.9

Importance of MP style

3.8

3.7

3.6

3.5

3.4

3.3 US

3.2 Japan

3.1

3.0

No MP < 1 yr 2–3 yrs > 4 yrs

• Figure 4 Style importance of own mobile phone by adoption timing

4.5

Heavy

Non/occasional

4.0

Importance

3.5

3.0

2.5

2.0

Battery Style

• Figure 5 Style versus battery life (US)

Meanings of the mobile phone: heavier vs lighter

(non-)users

The way in which American and Japanese youths view their ‘self ’ and

perceive ‘others’ via the mobile phone appears to be different depending on

their mobile phone-related behaviors. Heavier mobile phone users in our

study were fashion-attentive, and this extended to awareness of styles of

332

Downloaded from nms.sagepub.com at PENNSYLVANIA STATE UNIV on March 6, 2016

Katz and Sugiyama: Mobile phones as fashion statements

4.5

Heavy

Non/occasional

4.0

Importance

3.5

3.0

2.5

2.0

Battery Style

• Figure 6 Style versus battery life (Japan)

mobile communication technology. On the one hand, it is noteworthy that

this is characteristic of how they described their ‘self ’, but that they do not

think that mobile communication technology is for fashionable people. This

is characteristic of how they described ‘others’ in regard to the mobile

phone. The discrepancy between the way in which they described their self

and others in relation to fashion and the mobile phone may be worth

examining in light of what Fisher and Katz (2000) argue, that if you ask

people whether they get a phone for status, they are likely to say ‘no’, even

if it is true. If you ask them whether other people get phones for status,

they say ‘yes’. Since people tend not to be very comfortable about stating ‘I

am fashionable’, active users may well have said that the mobile phone is

not for the fashionable.

On the other hand, non-users and lighter users were comparatively less

fashion attentive. They also placed less value on the style aspect of their own

mobile phone. This result is consistent with what Robbins and Turner

(2002) mention, based on research in 1997 which was prepared for the

Cellular One Groups by Roper Starch Worldwide. According to the data,

only 24 percent of technology acceptors said that they did not care about

the style of a mobile phone so long as it works, while as many as 48

percent of technology rejecters agreed with this statement.

While non-users and lighter users of the mobile phone reported

themselves as less attentive to fashion and placing less value on the style of

their mobile phone, they associated the mobile phone with a fashionable

image more than heavier users – that is, they associated the mobile phone

with ‘fashionable others’. The same data that Robbins and Turner reviewed

333

Downloaded from nms.sagepub.com at PENNSYLVANIA STATE UNIV on March 6, 2016

New Media & Society 8(2)

show that only 10 percent of acceptors agreed with the statement: ‘I would

like people to admire the wireless phone I have’, while 28 percent of

rejecters agreed with the statement. Considering this report in conjunction

with our findings, non-users and lighter users might see others using a

mobile phone with some sort of admiration yet decide not to adopt it or

use it frequently. The reasons could be affordability or necessity, but our

results suggest that non-users and lighter users may think that the mobile

phone is a fashionable technology and does not fit in with their self-image.

Katz and Aakhus (2002) argue that people oscillate between explicit and

implicit reasons for their mobile phone use. Explicit reasons refer to form,

function and price, and implicit reasons refers to how others perceive them,

beliefs about its usefulness and appropriateness to one’s concept of ‘self ’

(2002: 309–10). The case of college students in the US and Japan that we

have examined seems to highlight this regard. As Katz and Aakhus argue:

Social actors must constantly perform a series of ever-changing and highly

complex social roles. They must also deal with other actors who themselves are

performing a series of ever-changing and highly complex social roles. This in

itself represents an uncertain and complex scenario in which communication

takes place. (2002: 314)

The way that people act and perceive others in public places within the

modern world, filled as they are with constantly changing personal

technologies, are part of a continuous and often tacit negotiation process.

Part of this struggle is to clarify many inherent ambivalences and layers of

meaning of the choreography of human communication.

Globalized meanings

As for the cultural meaning of the mobile phone, both the US and Japanese

youths showed many similarities. This suggests that young people from these

traditionally divergent cultures are quite convergent in using and perceiving

new communication technology as a fashion tool, and supports the findings

that Katz et al. (2003) reported as a result of comparison among US, Korea,

Namibia, and Norway. Given the current global environment, where similar

fashion trends catch on (Kaiser, 1997) and similar communication

technologies are available at about the same time, these findings make sense.

In fact, Meyrowitz (1997) states that the more people cross national

boundaries, the more similar social arenas that were once very different

become. Although cultural differences are expected, some near-universal

meanings of the mobile phone may be emerging in relation to fashion

among youths.

Although tangential to our original research question, one of the

unexpected results was that US students reported higher fashion

attentiveness than Japanese students in both gender groups. This was rather

334

Downloaded from nms.sagepub.com at PENNSYLVANIA STATE UNIV on March 6, 2016

Katz and Sugiyama: Mobile phones as fashion statements

surprising, since traditionally the Japanese are known for valuing the

aesthetic aspects of objects. They are also known for their enthusiasm for

shopping for ‘branded goods’ in the postmodern era (Clammer, 1992). We

suspect that the difference might be attributable to the potential cultural

differences in responding to surveys (Iwao, 1993). However, further research

is needed in this area.

This research is preliminary, and merely scratches the surface of the issue.

The samples were limited to college students who happened to be enrolled

in the classes from which we drew our participants and who happened to

be present on the day on which the surveys were administered. Despite the

limitations, however, the results suggest important trends about how youths

use the mobile phone symbolically – more specifically as ‘fashion’ – to

express themselves and evaluate others. Indeed, despite many assertions in

popular and academic articles as to the importance of fashion in mobile

phone behavior, little research from a quantitative perspective has been done

to document the phenomenon. Further research with random samples and

from other cultures would be useful to understand the area better.

CONCLUSION

This study of the relationship between fashion and the mobile phone among

American and Japanese youths provides evidence that fashion is a highly

relevant influence on personal communication technology adoption, use and

replacement. Consequently, scholarly attention to fashion is neither frivolous

nor irrelevant. Moreover, as Apparatgeist theory argues, there are markedly

different perceptions of the technology in question driven, not by the

functionality of devices, but by the perceptions and social location of the

users and non-users. That is, mobile phone users and non-users seem to

assign different symbolic meanings to it. Moreover, the symbolic meanings

were largely consistent across both the US and Japanese cultures. How

people incorporate them into their self-image and rely on them as status

markers to perceive others, suggests that mobile communication technology

is becoming part of them symbolically as well as physically. In this sense, the

‘machines that become us’ perspective, which emphasizes the physical

manipulation of the devices around the body, and their incorporation into

the body (Katz, 2003), may foster further understanding of human

communication behavior and the place of technology in society.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Akira Nogami, Jenny Mandelbaum, and Mark Frank

for assisting with data collection, and the students who participated in the survey at

Nishogakusha University and Rutgers University. An earlier version of this article was

presented at ‘Front Stage/Back Stage – Mobile Communication and the Renegotiation

of the Social Sphere’, Grimstad, Norway, 23 June 2003.

335

Downloaded from nms.sagepub.com at PENNSYLVANIA STATE UNIV on March 6, 2016

New Media & Society 8(2)

Note

1 This total does not add up to 100% due to the elimination of cases with missing

data.

References

Clammer, J. (1992) ‘Aesthetics of the Self: Shopping and Social Being in Contemporary

Urban Japan’, in R. Shields (ed.) Lifestyle Shopping: the Subject of Consumption, pp.

195–215. New York: Routledge.

Crane, D. (2000) Fashion and Its Social Agendas: Class, Gender, and Identity in Clothing.

Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

Davis, F. (1985) Clothing and Fashion as Communication’, in M.R. Solomon (ed.) The

Psychology of Fashion, pp. 15–27. Lexington, MA: Lexington Books.

Davis, F. (1992) Fashion, Culture, and Identity. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

Dimmick, J.W., J. Sikand and S.J. Patterson (1994) ‘The Gratifications of the Household

Telephone’, Communication Research 21(5): 641–61.

Fisher, R.J. and J.E. Katz (2000) ‘Social Desirability Bias of the Validity of Self-reported

Values’, Psychology and Marketing 17(2): 105–20.

Fortunati, L. (2002) ‘Italy: Stereotypes, True and False’, in J.E. Katz and M. Aakhus (eds)

Perpetual Contact, pp. 42–62. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Goffman, E. (1959) The Presentation of Self in Everyday Life. New York: Anchor.

Green, N. (2003) ‘Outwardly Mobile: Young People and Mobile Technologies’, in J.E.

Katz (ed.) Machines That Become Us, pp. 201–17. New Brunswick, NJ: Transaction.

Haddon, L. (2003) ‘Domestication and Mobile Telephony’, in J.E. Katz (ed.) Machines

That Become Us, pp. 43–55. New Brunswick, NJ: Transaction.

Hall, E.T. (1976) Beyond Culture. New York: Doubleday.

Hofstede, G. (1980) Culture’s Consequences: International Differences in Work-related Values.

Beverly Hills, CA: Sage.

Hofstede, G. (1991) Cultures and Organizations: Software of the Mind. Berkshire: McGraw-

Hill.

Iwao, S. (1993) The Japanese Woman: Traditional Image and Changing Reality. New York:

Free Press.

Kaiser, S. (1997) The Social Psychology of Clothing (2nd edn). New York: Macmillan.

Kasesniemi, E. and P. Rautiainen (2002) ‘Mobile Culture of Children and Teenagers in

Finland’, in J.E. Katz and M. Aakhus (eds) Perpetual Contact, pp. 170–92. Cambridge:

Cambridge University Press.

Katz, J.E. (1999) Connection. New Brunswick, NJ: Transaction Publishers.

Katz, J.E. (ed.) (2003) Machines That Become Us. New Brunswick, NJ: Transaction.

Katz, J.E. and M. Aakhus (eds) (2002) Perpetual Contact. Cambridge: Cambridge

University Press.

Katz, E., J.G. Blumler and M. Gurevitch (1974) ‘Utilization of Mass Communication by

the Individual’, in J.G. Blumler and E. Katz (eds) The Uses of Mass Communications:

Current Perspectives on Gratifications Research, pp. 20–30. Beverly Hills, CA: Sage.

Katz, J.E., M. Aakhus, H.D. Kim and M. Turner (2003) ‘Cross-Cultural Comparison of

ICTs’, in L. Fortunati, J.E. Katz and R. Riccini (eds) Mediating the Human Body, pp.

75–86. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

Leung, L. and R. Wei (2000) ‘More than Just Talk on the Move: Uses and Gratification

of Cellular Phones’, Journalism and Mass Communication Quarterly 77(2): 308–20.

Ling, R. and B. Yttri (2002) ‘Hyper-coordination Via Mobile Phones in Norway’, in J.E.

Katz and M. Aakhus (eds) Perpetual Contact, pp. 139–69. Cambridge: Cambridge

University Press.

336

Downloaded from nms.sagepub.com at PENNSYLVANIA STATE UNIV on March 6, 2016

Katz and Sugiyama: Mobile phones as fashion statements

Meyrowitz, J. (1997) ‘Shifting Worlds of Strangers: Medium Theory and Changes in

“them” Versus “Us”’, Sociological Inquiry 67(1): 59–71.

Pedhazur, E.J. and L.P. Schmelkin (1991) Measurement, Design, and Analysis: An Integrated

Approach. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

Robbins, K.A. and M.A. Turner (2002) ‘United States: Popular, Pragmatic and

Problematic’, in J.E. Katz and M. Aakhus (eds) Perpetual Contact, pp. 80–93.

Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Rubinstein, R.P. (2001) Dress Codes. Boulder, CO: Westview Press.

Simmel, G. (1904) ‘Fashion’, The International Quarterly 10(1): 130–55.

Simmel, G. (1950) The Sociology of George Simmel (trans. W. Kurt). Glencoe, IL: Free

Press.

Skog, B. (2002) Mobiles and the Norwegian Teen: Identity, Gender and Class’, in J.E.

Katz and M. Aakhus (eds) Perpetual Contact, pp. 255–73. Cambridge: Cambridge

University Press.

Steele, V. (1997) Fifty Years of Fashion. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

JAMES E. KATZ is a professor in the Department of Communication, Rutgers University. He

has published numerous articles and books on mobile communication, including his most

recent book, Machines That Become Us (Transaction, 2003), which he edited based on a

conference held at Rutgers University.

Address: Department of Communication, School of Communication, Information and Library

Studies, Rutgers University, 4 Huntington Street, New Brunswick, NJ 08901–1071: USA. [email:

jimkatz@scils.rutgers.edu]

SATOMI SUGIYAMA is NEH Fellow at Colgate University and a PhD candidate at the

Department of Communication, Rutgers University. Her research interests includes questions

of fashion and self-representation in communication technology in various cultural contexts.

337

Downloaded from nms.sagepub.com at PENNSYLVANIA STATE UNIV on March 6, 2016

You might also like

- Ascor Research Program 2022 2026Document9 pagesAscor Research Program 2022 2026hamdiNo ratings yet

- Drummer Hoff Ai LessonDocument1 pageDrummer Hoff Ai Lessonapi-316911731No ratings yet

- Bogaert Understanding AsexualityDocument101 pagesBogaert Understanding AsexualitySsdfsNo ratings yet

- Answer Key CH 2Document8 pagesAnswer Key CH 2Thien HuongNo ratings yet

- Staying Connected While On The Move:: Cell Phone Use and Social ConnectednessDocument20 pagesStaying Connected While On The Move:: Cell Phone Use and Social Connectednessdena dgNo ratings yet

- COM3705 Jadie-Lee Moodly Exam PortfolioDocument19 pagesCOM3705 Jadie-Lee Moodly Exam Portfoliojadie leeNo ratings yet

- Research Proposal (2) - 3Document16 pagesResearch Proposal (2) - 3zhiarabas31No ratings yet

- Bitstream 3555034Document14 pagesBitstream 3555034m20231000862No ratings yet

- What Would Mcluhan Say About The SmartphoneDocument7 pagesWhat Would Mcluhan Say About The SmartphoneNelson Marinelli FilhoNo ratings yet

- Surveillance CapitalismDocument19 pagesSurveillance CapitalismJey Fei ZeiNo ratings yet

- E302b V3 Mur-AhmDocument4 pagesE302b V3 Mur-AhmMurtza AmjadNo ratings yet

- Research PaperDocument42 pagesResearch Papersrishti kansalNo ratings yet

- Lesson 2 - Elements - Characteristics of A TrendDocument20 pagesLesson 2 - Elements - Characteristics of A TrendGerald SioquimNo ratings yet

- Coleman - Annual Review of Anthropology & Digital MediaDocument23 pagesColeman - Annual Review of Anthropology & Digital MediaLuke SimulacrumNo ratings yet

- Defining Social TechnologiesDocument10 pagesDefining Social TechnologiesAnn KamauNo ratings yet

- Media Culture NotedDocument16 pagesMedia Culture NotedAyesha AamirNo ratings yet

- Deuze, M., Blank, P., Speers, L. (2010) - Media Life. Working PaperDocument45 pagesDeuze, M., Blank, P., Speers, L. (2010) - Media Life. Working PapercecimarandoNo ratings yet

- The Mobile Phone: An Indispensible Part of Our Lives. But Does It Hold Creative Production Potential?Document12 pagesThe Mobile Phone: An Indispensible Part of Our Lives. But Does It Hold Creative Production Potential?vickigeorgiouNo ratings yet

- The Effect of Social Media Influencers' On Teenagers Behavior: An Empirical Study Using Cognitive Map TechniqueDocument14 pagesThe Effect of Social Media Influencers' On Teenagers Behavior: An Empirical Study Using Cognitive Map Technique2023844318No ratings yet

- Title Smartphone Impact Narinder KaurDocument9 pagesTitle Smartphone Impact Narinder Kaurgurleenkauraulakh43No ratings yet

- Front Matter 2018Document10 pagesFront Matter 2018Delia VrânceanuNo ratings yet

- 2 Slouching Toward The Ordinary Current Trends in CoDocument12 pages2 Slouching Toward The Ordinary Current Trends in CoCode DeathNo ratings yet

- Reading Materials in Trends Sy 2021-2022 (First Quarter)Document24 pagesReading Materials in Trends Sy 2021-2022 (First Quarter)kat dizonNo ratings yet

- DatDang (2019) - Has Social Media Made Students More or Less ConnectedDocument27 pagesDatDang (2019) - Has Social Media Made Students More or Less Connectedjohanrein730No ratings yet

- INTRODUCTORY UNIT: New Media TechnologiesDocument6 pagesINTRODUCTORY UNIT: New Media TechnologiesadamrobbinsNo ratings yet

- Research PaperDocument28 pagesResearch PaperJenny EllordaNo ratings yet

- Farman - Stories Spaces and Bodies The Production of Embodied Space Through Mobile Media StorytellingDocument17 pagesFarman - Stories Spaces and Bodies The Production of Embodied Space Through Mobile Media Storytellinggilbert0queNo ratings yet

- Living in The It Era Bsce1a Paligutan R.Document4 pagesLiving in The It Era Bsce1a Paligutan R.Rialyn Mae PaligutanNo ratings yet

- The Future of Social Media in MarketingDocument17 pagesThe Future of Social Media in MarketingAsad SiddiquiNo ratings yet

- Roots, Routes, and Routers: Communications and Media of Contemporary Social MovementsDocument45 pagesRoots, Routes, and Routers: Communications and Media of Contemporary Social MovementspablodelgenioNo ratings yet

- Elements & Characteristics of A Trend: Errol P. BayonetaDocument20 pagesElements & Characteristics of A Trend: Errol P. BayonetaMarivic EstemberNo ratings yet

- Critique PaperDocument7 pagesCritique PaperJRussell IgnacioNo ratings yet

- Global PerspectiveDocument6 pagesGlobal PerspectiveDaisy Rose EliangNo ratings yet

- The Internet and Youth Culture: Gustavo S. MeschDocument11 pagesThe Internet and Youth Culture: Gustavo S. Meschxlitx02No ratings yet

- Role of New Media Communication Technologies en Route Information Society - Challenges and ProspectsDocument10 pagesRole of New Media Communication Technologies en Route Information Society - Challenges and Prospectsharry grantNo ratings yet

- 1 s2.0 S0747563222003181 MainDocument11 pages1 s2.0 S0747563222003181 Maintrongmanh.travelgroupNo ratings yet

- Smartphone: January 2019Document12 pagesSmartphone: January 2019BinTatta KhaanNo ratings yet

- Report On The Mobile Communications Workshop 9 January 2004Document4 pagesReport On The Mobile Communications Workshop 9 January 2004abhinavshankar987No ratings yet

- The Effect of Technology On FaceDocument23 pagesThe Effect of Technology On FaceJamie BagundolNo ratings yet

- Ito PPPDocument15 pagesIto PPPurara98No ratings yet

- Influence of Social MediaDocument21 pagesInfluence of Social MediaOmar JfreeNo ratings yet

- Scroll, Like, Repeat - The Psychological Impact of Social Media On The Attention Span of Gen Z'sDocument13 pagesScroll, Like, Repeat - The Psychological Impact of Social Media On The Attention Span of Gen Z'slux luciNo ratings yet

- Essay On Technology & SocietyDocument8 pagesEssay On Technology & SocietyalfreddemaisippequeNo ratings yet

- Crogan, P. and Kinsley, S. (2012) Paying Attention - Toward A Cri - Tique of The Attention Economy.Document30 pagesCrogan, P. and Kinsley, S. (2012) Paying Attention - Toward A Cri - Tique of The Attention Economy.Brett Michael LyszakNo ratings yet

- The Structural Transformation of Mobile Communication: Implications For Self and SocietyDocument14 pagesThe Structural Transformation of Mobile Communication: Implications For Self and SocietymichaelmorandomNo ratings yet

- ZMZ 027Document5 pagesZMZ 027Bela PristicaNo ratings yet

- The Role of Media On Socio Cultural ChangeDocument6 pagesThe Role of Media On Socio Cultural ChangeIJAR JOURNALNo ratings yet

- Technological ConvergenceDocument8 pagesTechnological ConvergenceRex FanaiNo ratings yet

- Media and Democratization in The Information Society by Marc RaboyDocument5 pagesMedia and Democratization in The Information Society by Marc RaboyGeorge LimbocNo ratings yet

- The Impact of Personality Traits On Social Media Use and Engagement: An OverviewDocument19 pagesThe Impact of Personality Traits On Social Media Use and Engagement: An OverviewPeleus Adven MesinaNo ratings yet

- "What Is Computer-Mediated Communication?"-An Introduction To The Special IssueDocument5 pages"What Is Computer-Mediated Communication?"-An Introduction To The Special IssueerikNo ratings yet

- DMSM Assignment 1Document9 pagesDMSM Assignment 1Melika MundžićNo ratings yet

- Module 2 The Evolution of Traditional To New MediaDocument8 pagesModule 2 The Evolution of Traditional To New MediaLeo Niño Gonzales DulceNo ratings yet

- The Interplay Between Technology and Humanity and Its Effect in The SocietyDocument53 pagesThe Interplay Between Technology and Humanity and Its Effect in The SocietyXander EspirituNo ratings yet

- Mass Communication Theories in A Time of Changing TechnologiesDocument10 pagesMass Communication Theories in A Time of Changing TechnologiesFikri AmirNo ratings yet

- Project Hate SpeechDocument10 pagesProject Hate SpeechGlascow universityNo ratings yet

- Abireham AdamDocument33 pagesAbireham AdamadaneNo ratings yet

- Culture and HciDocument17 pagesCulture and HciakheelasajjadNo ratings yet

- Sadie PlantDocument45 pagesSadie PlantLucia SanNo ratings yet

- TNCT (Trends Network and Critical Thinking in The 21st Century)Document17 pagesTNCT (Trends Network and Critical Thinking in The 21st Century)Cleofe SobiacoNo ratings yet

- Sociological Aspects of Science and TechnologyDocument4 pagesSociological Aspects of Science and Technologycreo williamsNo ratings yet

- Digital Culture & Society (DCS): Vol. 3, Issue 2/2017 - Mobile Digital PracticesFrom EverandDigital Culture & Society (DCS): Vol. 3, Issue 2/2017 - Mobile Digital PracticesNo ratings yet

- Skill Gap Study - UKDocument229 pagesSkill Gap Study - UKsowmiyaNo ratings yet

- RPi - GPIO Cheat Sheet PDFDocument4 pagesRPi - GPIO Cheat Sheet PDFadebolajo sundayNo ratings yet

- Impacts of Social Media Towards Academic Excellence Among The Senior High School Students of Headwaters CollegeDocument62 pagesImpacts of Social Media Towards Academic Excellence Among The Senior High School Students of Headwaters CollegeLea Mhar P. Matias100% (1)

- Types of Learning: 2) Operant ConditioningDocument3 pagesTypes of Learning: 2) Operant ConditioningazuristicNo ratings yet

- BMEC Centre Approval Application Form v3Document3 pagesBMEC Centre Approval Application Form v3jojoalexanderNo ratings yet

- Jean Monnet Programme 2012 List of FundedDocument11 pagesJean Monnet Programme 2012 List of FundedBoban StojanovicNo ratings yet

- Acsi Position On Common Core State StandardsDocument4 pagesAcsi Position On Common Core State Standardsapi-322721211No ratings yet

- A Responsible Approach To Higher Education Curriculum DesignDocument21 pagesA Responsible Approach To Higher Education Curriculum Designanime MAVCNo ratings yet

- SAP Functional & Business AnalystDocument3 pagesSAP Functional & Business Analysttk009No ratings yet

- Modified Offline AF3Document2 pagesModified Offline AF3Ian BarrugaNo ratings yet

- CM ResumeDocument3 pagesCM Resumeapi-297808467No ratings yet

- THE Organizational Policies V Procedures DocumentDocument5 pagesTHE Organizational Policies V Procedures DocumentfarotimitundeNo ratings yet

- Positive ThinkingDocument9 pagesPositive ThinkingSridhar Rao KudavellyNo ratings yet

- 5th Grade Collaborative LessonDocument6 pages5th Grade Collaborative Lessonms02759No ratings yet

- Kryon MetaphysicsDocument13 pagesKryon MetaphysicsSiStar Aset100% (1)

- Resume 2018Document1 pageResume 2018api-280142822No ratings yet

- The Perspective of Grade 12 HUMSS Students On Using Gamification in Improving Engagement in Online ClassDocument10 pagesThe Perspective of Grade 12 HUMSS Students On Using Gamification in Improving Engagement in Online ClassLeonorico BinondoNo ratings yet

- United States Court of Appeals, Tenth CircuitDocument15 pagesUnited States Court of Appeals, Tenth CircuitScribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Prakash Abraham Resume Nebosh IgcDocument3 pagesPrakash Abraham Resume Nebosh IgcSumanth ReddyNo ratings yet

- Tugas Textbook AnalysisDocument1 pageTugas Textbook AnalysisKiplyNo ratings yet

- Dress For Success Workshop by ExeqserveDocument6 pagesDress For Success Workshop by ExeqserveWilson BautistaNo ratings yet

- Fs 5 Episode 8Document3 pagesFs 5 Episode 8Sharina Mae EnriquezNo ratings yet

- Write Code.: Catch BananasDocument1 pageWrite Code.: Catch BananasLuis JavierNo ratings yet

- English 10Document1 pageEnglish 10Dolorfey SumileNo ratings yet

- Teacher'S Weekly Learning PlanDocument3 pagesTeacher'S Weekly Learning PlanMA. CHONA APOLENo ratings yet

- Chapter 1-What Is Organizational BehaviourDocument21 pagesChapter 1-What Is Organizational BehaviourMudassar IqbalNo ratings yet

- 21st Century Lit Q1W2Document17 pages21st Century Lit Q1W2MJ Toring Montenegro100% (1)