Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Taylor & Francis, LTD

Taylor & Francis, LTD

Uploaded by

lucky budyOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Taylor & Francis, LTD

Taylor & Francis, LTD

Uploaded by

lucky budyCopyright:

Available Formats

From Savage to Citizen: Education, Colonialism and Idiocy

Author(s): Murray K. Simpson

Source: British Journal of Sociology of Education, Vol. 28, No. 5 (Sep., 2007), pp. 561-574

Published by: Taylor & Francis, Ltd.

Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/30036235 .

Accessed: 15/05/2013 05:48

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at .

http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp

.

JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of

content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms

of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org.

Taylor & Francis, Ltd. is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to British Journal

of Sociology of Education.

http://www.jstor.org

This content downloaded from 155.247.167.222 on Wed, 15 May 2013 05:48:40 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

BritishJournalofSociologyofEducation

Vol. 28, No. 5, September2007, pp. 561-574 RRoutledge

& Francis

Taylor Group

From savage to citizen: education,

colonialism and idiocy

MurrayK. Simpson*

The University

ofDundee, UK

In constructinga frameworkforthe participationand inclusionin politicallife of subjects,the

Enlightenment also produceda seriesofsystematic exclusionsforthosewho did not qualify:includ-

ing'idiots'and 'primitiveraces'. 'Idiocy' emergedas partofwiderstrategiesofgovernancein Europe

and its colonies. This opened up the possibilityforpedagogyto become a keytechnologyforthe

transformation ofthesavage,uncivilisedOtherintothecitizen.This paper exploresthetransforma-

tiverole of pedagogyin relationto colonial discourse,the narrativeof the wild boy ofAveyron-a

feralchild capturedin France in 1800-and the formationof a medico-pedagogicaldiscourseon

idiocyin the nineteenthcentury.In doing so, thepaper showshow learningdisabilitycontinuesto

be influencedby same emphasison competenceforcitizenship,a legacyof the colonial attitude.

Introduction

Learning disabilityis a product of modern westernsocial governance.The tangle of

relations of power and knowledge that constituteit trace back to the emergence of

the normalisingprojects of westerngovernance. The ideas of citizenshipand social

being; the primacyof contractas the dominant formof social relationship;and the

conquest of the natural world, including its 'rude' peoples, have all contributedto

this emergence.

Invariablythishas resultedin social exclusion linkedto the matterof theirputative

social competence (Jenkins,1998) and consequentlyto techniques of pedagogy and

perceptions of capacity forlearning (Trent, 1994; Simpson, 1999). In this respect,

idiots shared with other marginalisedgroups the demand that citizenshiprequired

transformation-citizenshipbeing both a practice and a status. As we shall see, this

theme connected the emergentmodern discourse on idiocy with attemptsto civilise

the uneducated and untamed 'savage' at home in Europe and abroad among the

indigenous peoples of colonised lands.

*SchoolofEducation,

SocialWorkandCommunity The University

Education, ofDundee,Dund-

ee DD1 4HN, UK. Email:m.k.simpson@dundee.ac.uk

ISSN 0142-5692(print)/ISSN

1465-3346(online)/07/050561-14

C 2007 Taylor& Francis

DOI: 10.1080/01425690701505326

This content downloaded from 155.247.167.222 on Wed, 15 May 2013 05:48:40 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

562 M. K. Simpson

The paper exploressome of these interconnectingthreadsin orderto show how the

modern discourse of idiocy emerged in part fromthe same linguisticfield as racial

anthropology.It constructsan analyticframeworkusing eighteenth-century colonial

and racial commentaries,the narrativeof the savage boy of Aveyron-the studyand

attemptededucation of a feralboy at the beginningof the nineteenthcentury--and

the 'physiologicalmethod' in the treatmentof idiocy mid-century.

The savage other

The word 'savage' derivesfromthe Old French sauvage ('from the woods') fromthe

Latin 'silvan' (lyingbeyond the governedrealms of towns and settlements;the largely

uninhabitedwooded lands beyond the shortreach of the law; untamed, uncultivated

and uncivilised). At a time when even the cities and towns were violent places and

crime went largelyunpunished (Rossiaud, 1990), the mediaeval wilderness was a

place inhabited by the 'marginal man', largelyabsent fromthe recorded landscape,

where the banished were treated as wolves and drivenfromthe towns and villages,

and the outlawed roamed (Geremek, 1990). Interestin the 'savage' peoples of other

lands was a consequence of the exploration and colonisation of large parts of the

world by European powers since the fifteenth century.

'Savage' as an aspect of the bucolic and those livingoutside the boundaries of soci-

ety in Europe as well as the 'exotic' peoples of other lands is not accidental. As

Kliewer and Fitzgerald (2001) observe, at the same time as the grasp of colonial

power reaches outwards and associated discourses of subjugation develop, so too

does the internalnexus of governanceof civilsocietyin Europe. Nonetheless, thereis

a pronouncedtendencyin writing,

sincethelastcenturyat least,to projectcontem-

poraryusages of the word; that is, to signify'animal' violence, to refersolely to the

exotic 'other' (forexample, Street, 1975; Jahoda, 1999), or indeed to see it as having

a 'double life' with two 'different'meanings when applied at home and abroad

(Williams, 2003). However, even to distinguishbetween the 'domestic' and 'exotic'

savage involves conceptual retro-projection.The more significantand interesting

question is: how were theyconceived as similar?

Popular interestduring the seventeenthcenturyin the exotic savage was fuelled

froma number of sources. Novels set in newlydiscovered climes,factualor fictional,

and featuringthe culturallyalien were popular: Aphra Behn's Oroonoko (1688),

Daniel Defoe's RobinsonCrusoe (1719), JonathanSwift's Gulliver'sTravels (1726),

Voltaire's Candide (1759), and so forth.Travellers' tales were another rich, if not

always entirelyaccurate, source of information,stemming in particular from the

thirteenth-century travelsof Marco Polo to the Far East.

Of particular interest for this paper were French activities in the eastern

seaboard of what would become Canada and the United States. In the eighteenth

century,French colonial interestslay in two principal directions: first,and most

importantly,they were centres of trade; second, they were outposts of missionary

activity,most significantly by the Jesuits(see, for example, Vaughan, 1978; Greer,

2000; Cooper, 2001). It is this second area that is of greatest interest, both

This content downloaded from 155.247.167.222 on Wed, 15 May 2013 05:48:40 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Education,colonialismand idiocy 563

because the Jesuits provided a great deal of information about the peoples

among whom they worked and also because they provide a paradigm for the

conversion and civilisationof the savage that parallels the interestin the wild boy

of Aveyron.

The Society of Jesus placed great emphasis on the importanceof education in all

theiractivities,includingtheirmissionaryactivitieswithuncivilisedpeoples. Indeed,

it was thisverylack of a proper civilisingeducation that definedsavagery.The Jesuit

missionaryPaul le Jeune wrote of his time among the Montagnais in the sixteenth

centurythus:

... thewell-formed

bodiesandwell-regulated andwell-arranged

organsofthesebarbarians

suggest thattheirmindstoo oughtto function well.Educationand instruction

aloneare

lacking... I naturally

compareourIndianswith[European]villagers, becausebothare

usuallywithout education... (leJeune,2000,p. 33)

le Jeune captures a common connectionbetween the savage abroad and the illiterate

peasantryat home. Also significantis the assertionthatit is thewant ofeducation that

makes the differencebetween the civilised and the uncivilised (Dorsey, 1998). This

view was also linkedto hierarchicaland evolutionaryviews of societies:

... theInhabitants

ofthegreatBretannie

havebinin timespastas sauvageas thoseof

Virginia. quotedinAxtell,1992,p. 68)

(ThomasHarriot,

Towards the end of the eighteenthcentury,scientifictheoriesof race had begun to

emerge also based on linearhierarchies,but rooted in the altogethermore staticidea

of the Great Chain of Being-the deisticidea that all livingand inertthingsoccupy a

place in an infinitely

graduatedscaledesignedbytheCreator(Jahoda,1999). Bonnet,

forexample, presentsa seamless scale fromman down throughquadrupeds, to birds,

fish, and other classes of animals, to plants, stones, ending in the three primary

elementsand 'more subtle matter' (White, 1799). Common to such theorieswas the

settingout of hierarchiesof human races withinwider classificationsof simian and

other animal species; in particular,to situate the negro as a species intermediate

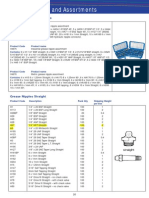

between man and ape (Jahoda, 1999). Charles White illustratessuch approaches, as

well as his adherence to the Great Chain principle, in his classificationof species

according to the cranial front-angle(Figure 1) (White, 1799).

Notwithstandingthe physiognomicaspects of race theories,the principalemphasis

was on the civilisingimpulse. Indeed, therewas no question that this was a primary

dutyforthe colonisers,and it depended fundamentallyon viewingthe savage as capa-

ble of being civilised. For some, the primarycauses of physiologicaland physiogno-

mic differenceswere to be found in environmentalfactors. The Revd Samuel

Stanhope Smith of the American Philosophical Society noted:

... personswho havebeen captivated fromthestates,and grownup, frominfancy to

middle age, in the habits of savage life ... universally

contractsuch a strong-

resemblance of thenativesin theircountenance,and evenin theircomplexion,as to

afford a strikingproofthatthe differences

whichexist,in the same latitude,

between

the Anglo-Americanand the Indian, depend principallyon the state of society.(Smith,

2001,p. 93)

This content downloaded from 155.247.167.222 on Wed, 15 May 2013 05:48:40 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

564 M. K. Simpson

Figure 1. Cranial classification(White,1799)

Attitudestowards the innate goodness of the savage were sharplydivided between

those like Rousseau (1973b) who regarded the nobilityof man in his natural state,

and those who saw theirexistence in a more negative light,marked by cannibalism

and depredation,such as was the Jesuitview (forexample, Chauchetiere, 2000). In

either case, however, there was an unambiguous belief that civil life demanded a

liftingout of the state of 'savage solitude' (Godwin, in Rodway, 1952, p. 217) by

means of education. Although, of course, views on how this education should be

accomplished were equally divided. Understandingthe 'natural man' was, however,

the keyto formulatingthe necessarypedagogy (Rousseau, 1973b).

Anothercrucial point about the place of the savage otherwas theirrole in defining

the normal and acceptable. Williams (2003) observesthatthe process of constructing

the unciviliseduneducated people of ruralFrance was also a constructionof'French-

ness' itself.Said (1991), of course, makes the case forthe much wider construction

of the European throughthe process of Orientalism.Similarly,idiocy would, in due

course, come to play a keyrole in definingthe 'normal' child (Rose, 1985).

From savage to Victor

In spite ofthe two centuriesthathave now passed since the firstsightingsofthe young

Sauvage de l'Aveyron,the interestin the eventssurroundinghis entryinto societyhas

remained strong.The sequence of eventsbegan withthe entryof the feralboy into a

workshopin a village in the Department of Aveyronin January1800, and proceeded

throughhis examinationby some of the finestminds of the French academy, to the

This content downloaded from 155.247.167.222 on Wed, 15 May 2013 05:48:40 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Education,colonialismand idiocy 565

reportson his education at the InstituteforDeaf-Mutes, Paris by Itard. Most of this

concern has centred on such matters as the progress in educational theory and

method since those foundingevents in the historyof pedagogy; or to resolve long-

standingpsychologicalquestions, forinstance on language acquisition or intellectual

development-was the savage mentallyretarded,or perhaps autistic;what could his

storytellus about special education, and so on (forexample, Gaynor, 1972; Shattuck,

1980; Ernct, 1995). Above all, as Harlan Lane puts it in his detailed psychological

profile,

... thewildboywastohelpanswerthecentral

questionoftheEnlightenment,

Whatis the

natureofman?(Lane, 1976,p. 19)

The theme of transforming the boy froma savage to a civil being strucka chord

withwider developmentsin philosophy,anthropology,medicine, the developmentof

race theories and colonial expansion. Itard's effortswith the boy, whom he named

Victor,thus connect withthe precedingpart of the paper. They also connect withthe

succeeding look at the descent of the discourse on idiocy,which took definiteshape

several decades later.

Apropos the connections between colonialism and the education of the savage of

Aveyron,a look at some of the principalfeaturesofItard's workwill serveto highlight

the parallels. For instance,the boy's naturalselfishinterestsand instinctualbehaviour

are described in termsremarkablysimilarto attitudestowardssavage tribesas well as

to Rousseau's eponymous pupil, Emile. He was amoral and lackingin any notion of

property,and thereforetheft.Despite the pessimisticinitialassessmentof many that

the savage was an idiot, Itard believed thatthe savage's state signified,

... thedegreeofunderstanding, andthenatureoftheideasofa youth, from

who,deprived,

hisinfancy, ofall education,

shouldhavelivedentirelyseparatedfromindividuals

ofhis

species... (Itard,1972a,p. 99)

As such, Itard believed that a programme of instruction,carefullyconceived and

experimentally implemented,might'cure thisapparentidiotism' (Itard, 1972a, p. 99).

It is, perhaps,on thispoint thata fullunderstandingofthe lexical fieldofthe savage

can best be approached since it linksdomestic and exotic savagery.In Smith's essay

we find:

Everyobjectthatimpresses

thesenses,andevery emotionthatrilesinthemind,affectsthe

features

ofthefacetheindexofourfeelings,

andcontributes toformtheinfinitely various

countenance ofman.Paucityofideascreatesa vacantand unmeaning aspect.Agreeable

and cultivated

scenescomposethefeatures,

andrenderthemregular andgay.Wild,and

deformed, andsolitary

forests

tendto impress

on thecountenance, an imageoftheirown

rudeness.(Smith,2001,pp. 80-81)

The importance of sensation and experience had been a key theme in European

philosophysince Locke, runningthrougheven such disparate strandsas the empiri-

cism of Berkeleyand Hume, the idealism of Kant, and the sensationismof Condillac.

Apperception,understandingand the capacity forreason became definitiveof Man

in the Enlightenment.Want of these features,whetherthroughphysiologicaldefi-

This content downloaded from 155.247.167.222 on Wed, 15 May 2013 05:48:40 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

566 M. K. Simpson

ciency or environmentalcircumstance,was, above all else, what characterisedthe

uncivilised. Their development marks progress from 'mere private force' (Kant,

1974, p. 185) dominated by animal instincts,towards the state of social being. The

acquisition, multiplicationand combination of ideas 'distinguishes [civilised] man

from... a "clod of the valley"' (Godwin, 1971, p. 60). The absence of manifoldand

complex ideas arisingfromreflectionon sensorystimulationis a recurrenttheme in

discussions on the savage:

Negroes'seemunableto combineideas,orpursuea chainofreasoning'.

(Long,1774,in

Jahoda,1999,p. 55)

Victorwas 'deprived... ofall thosesimpleand complexideaswhichreceivefromeduca-

tion,andwhicharecombinedin ourmindsin so manydifferent ways,bymeansonlyof

ourknowledge ofsigns'.(Itard,1972a,p. 99)

The ruraldwellers[ofBrittany] in complexthoughts

are moredeficient thanare the

Mohicansand theredskinsof theAmericannorth... (Balzac Les Chouans,quotedin

2003,p. 485; author'stranslation)

Williams,

The savage was closer to nature,whetherbrutishor noble-nature being the antith-

esis of civilisation;thatwhich must be subordinated and harnessed, individuallyand

globally (Gay, 1977). In this putative propinquityto the natural world we find a

furtherreason why'savage' was applied equally to the feralchild, those who laboured

on the soil and animalisticprimitivetribes.

What we have, then, is a constellationof views about whether,and the extentto

which,physiologyand capacity forcivilisationare immutable fordifferent races and

individuals. What the domestic and exotic savage share, however, is the common

characteristicof deficitin refinedand complex ideas, which are the foundationsof

civil being. In the case of the asocial idiot, this is a more or less permanent state of

affairs;forthe pre-social peasant, it is fromthe want of proper education; while for

the exotic savage or the lunatic, opinion on mutabilitywas more divided. Unsurpris-

ingly,perhaps, proponents of scientificpedagogy were more likelyto emphasise a

common and educable human nature (forexample, Poole, 1825). All are solitary;if

not always in the sense of physical isolation, then in the lack or impoverishmentof

theirsocial relations.

Yousef (2001) contrasts Rousseau's natural man-'isolated and autonomous'

(p. 245)-with the savage who is 'sociable' and the animal, lacking the potential for

the qualities of civilisedman. For Yousef, the 'isolation' of the natural man pertains

to development in the absence of other men. However, the 'sociability' ascribed to

savage tribes by Rousseau and others is really no more than the gregariousnessof

animals. Even in the presence of others,the savage is not a regardedas a social being.

Rousseau explicitlyidentifiessolitude as a definingcharacteristicof the savage, and

uses thatword to referto primitivetribesin Africaand the Americas as well as to the

physicallyisolated. The feral child and the primitivetribesmanmay be in different

states,but theyare both states of nature,not states of society.

Itard's pedagogical endeavours are of particularrelevancehere both in termsof the

symbolic as well as the practical role that education is made to play as the bridge

This content downloaded from 155.247.167.222 on Wed, 15 May 2013 05:48:40 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Education,colonialismand idiocy 567

between the savage and moral man-embodied in the actual transformationof the

savage into Victor. One of Itard's principalsources of support forhis methods were

the precepts of moraltreatment,as expounded by Francis Willis, Alexander Crichton

and Philippe Pinel in the treatmentof insanity.Indeed, the education of the savage

was itselfhis moralisation:

To attachhim to social life,by renderingit morepleasantto him thanthatwhichhe was

thenleading ... [And to] extendthe sphereofhis ideas, by givinghimnew wants,and by

increasingthe number of his relationsto the objects surroundinghim. (Itard, 1972a,

p. 102)

One ofthemethodsemployedbyItardto harnessthedesiresofVictorwas to repeat

enjoyedactivitiesin orderto 'converta pleasureinto a want' (1972a, p. 113); for

example,on finding thattheboyenjoyedan outingto a tavernfora meal.Beforelong

theactivity ceasedto be a pleasurabletreatand Victorbecamedepressedand agitated

whenitwas withheld.

Each ofItard'sobjectiveswarrants a fullexploration,

pregnantas theyarewithall

ofthethemesofthispaper.However,we shalllimitourselvesto a fewkeyobserva-

tions.First,Itard'sapproachshowsclearconsonancewithRousseau's methodthat

thepupilbe led to see theadvantagesofcitizenship intermsofself-interest. Itarddoes

not oppose thesavageboy's naturalinclinations; instead,thesewillbe harnessedin

theprocessofhis moralisation. In thecase ofVictor,theaffinity withnaturalevents

and phenomenais obviouslymorehighly developedthanwithEmileorwouldbe with

otherchildren.Nonetheless,thetargetremainsto securethepre-socialdesiresand to

channelthemtowardscitizenship. Second,thereis theself-evident superiorityofcivil

lifeoverthesavageexistence,whichis matchedby colonialattitudestowardssavage

tribeswhowouldhaveto civiliseor perish(see, forexample,Kriegleder, 2000). The

Jesuits tookseriously whattheysaw as theirobligations to protectindigenouspeoples

fromthemoreruthlesstreatment at thehandsoffinancially motivatedcolonisers.In

South Americatheydevelopedtheirsystemof reducci6nes; settlements in which

nativeswould gainprotectionat the priceof submission(Greer,2000). Third,the

pedagogicalapproachis heavilyrootedin physiology and theeducationofthewhole

body,a pointthatwouldbecomeespeciallyimportant inthetreatment ofidiocy;Itard

comments'thatsensibility is in exactproportion to thedegreeofcivilization' (1972a,

p. 105). Fourth,Itardaimsat thecreationand harnessing ofdesireas a pedagogical

socialisinginstrument. It is perhapsthe most crucialobjective,and difficulties in

accomplishing it are citedas hindering the progressof the intelligenceand civility.

There are to be twoimportant partsto achievingthisobjective;firstly,constructing

the desiresof the subjectand, secondly,establishingthe positionof the subject

relativeto thenaturaland social world.The subjectis thusconstructed in bothhis

internaland externalrelations.

Itardconcludeshisfirst reporton theeducationofthesavageofAveyron bynoting

thatin the 'purestateofnature',isolatedand withan intellectstilllargelydormant,

manis inferior to manyanimals.It is onlywithinandbymeansofcivilisation thatman

is able to riseabove thismiserablestate,and by 'civilisation' is meanttheperpetual

This content downloaded from 155.247.167.222 on Wed, 15 May 2013 05:48:40 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

568 M. K. Simpson

developmentofmind,primarilythroughimitationand the quest fornew experiences.

The power forsuch developmentwanes with age and, consequently,the importance

of effectivepedagogy in childhood is paramount, multiplyingwants, increasingthe

mental capacitynecessaryto secure them. So, while Rousseau and Itard differin their

assessments of the natural state of man, whethernoble or brutish,civil society is at

least a necessarystate of being formodern man, and his education while stilla child

is the only means of preparingthe body and mind thatwill fithim to live in it.

Civilisation, then, stands in a multiple relationshipto education: it provides the

means, creates the need and constitutes a condition of possibility of education

simultaneously. It is the means of education in so far as the experience of social

mostnotably,it is onlyin the context

beingis itselfone of thegreatestinstructors;

of society that the intellectualfaculties,and particularlythe power of speech, can

fully develop. This was manifested in the savage's state of mental stultification

before his education, '... civilizationawoke the intellectual faculties of our savage

from their lethargy...' (Itard, 1972b, p. 168; emphasis added). In addition, Itard

accounts for the failure of his charge to spontaneously discover behaviours that

would allow him to channel his growingsexual urges. The harmonious connection

between human desires and sexual emotions is only 'the fortunatefruitof man's

education'(Itard,1972b,p. 178). It is onlyin thecontextofsocietythatthehigher

feelingscan develop at all; 'sadness, [forexample, is] an emotion belonging entirely

to a civilized man' (Itard, 1972b, p. 171). Lack of any social stimulus,particularly

duringthe developmental period, resultsin a kind of idiocy by sensorydeprivation,

even in the absence of organic lesion. In this firstsense, the termseducation, civili-

sation and moral treatmentare entirelysynonymous.In the second instance, civili-

sation also creates the need for education, the need for new civil subjects to

maintain and progressit. This aspect is manifestin the preceding discussions. The

savage does not develop the higher intellectual and moral functions in the wild

preciselybecause he has no need of them.Lastly,it is onlyin the contextof civil

societythat it becomes possible to conceive of the man as an unnatural occurrence,

as somethingto be moulded and produced fromnature's clay, the child. From the

modern, disciplined citizen, more is demanded than fear and obedience. Modern

societydemands the active participationof subjects in theirown subjection, practic-

ing civilityas though it were instinctual.

The pedagogical treatment of idiocy

Contemporaneous with Itard's work was a radical conceptual rupturein theoriesof

evolution and racial variation.The linearframeworksof developmentoutlined above

explode into the branchinggenealogical economies of biology and evolution,paving

the way for the evolutionarytheories of Darwin (Foucault, 1970). Indeed, by the

middle of the nineteenth century,theories on the inequalities of the races were

rejecting any notion that all races and societies are or ever could be on the same

developmental trajectory(for example, Galton, 1869; de Gobineau, 1970). In their

place were theoriespredicated on natural selection (Darwin, 1930).

This content downloaded from 155.247.167.222 on Wed, 15 May 2013 05:48:40 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Education,colonialismand idiocy 569

Itard's work straddles this divide. As Rose notes, Itard's work crosses-indeed,

creates-the thresholdat which modern psychologycan trulybe said to exist (Rose,

1985). The wild boy of Aveyronwas by no means the firstferalchild to have been

discovered in Europe in the nineteenthcenturyand to have aroused considerable

public interest(Newton, 2002). What made this case different was the way in which

effortsto educate him were based on systematicand rigorousobservation,experimen-

tation and measurement.

Nonetheless, the conceptual frameworkis stillinfluencedby the legacy of classical

notionsoflineardevelopment.Opinionwas dividedas to whetherthefailurein the

experimentwithVictorwas due to lack of progressin scientific

pedagogy,as Itard

believed, or the congenital idiocy of the boy, as others believed (Esquirol, 1965).

However, what was not seriouslycalled into question was thatthe differencebetween

the savage and the civil man was education, unless there be some qualitative

pathological reason forfailureto develop (i.e. idiocy).

His effortswere, however, to undergo a radical reappraisal by a young protege,

Edouard Seguin. Taking the view that Itard's charge had been an idiot fromthe

outset, Seguin began to reassess the success of Itard's methods, which,ifVictorwas

indeed an idiot,was remarkable.Seguin set about perfectinga systemof experimental

pedagogical treatmentfor idiots in the same experimentaltraditionthat Itard had

established (Seguin, 1866).

Seguin's workprovides anothernode in the complex: the introductionofbiological

defect. Kliewer and Fitzgerald (2001) discuss the ideological dilemma for Europe

engaged in colonisationacross the globe; namely,havingto account forthe deformed

and enfeebled at home in the face of a colonial discourse premised on the European

as more perfectand godly.It is withinthisideological lacuna, theyargue,thatmodern

discourses of disabilitydevelop. Increasingly,the conquest ofthe naturalworld meant

that the savage became less of a threatand more of a challenge of governance. The

savage, the pauper, the cripple, the idiot, they argue, all signifiedthe fundamental

problem of sloth. The effortsof Seguin and contemporarypedagogues was both a

response to and a cementingof the connections between learningand liberty,most

especially the 'contract' of humane confinementforthe inabilityto become normal,

self-governing and self-sufficient.

Seguin produced the firstsystematicallyexpounded theoryof education foridiot

children.Althoughthereis neitherthe space nor advantage in outliningthe method

here, thereare a number of featuresthat are important.The method derived empiri-

cal and theoreticalsupport from a number of quarters-most importantlyphysiol-

ogy-in addition to those already mentioned: Itard, Rousseau and the exponents of

moral treatment.Seguin's method ofpedagogicaltreatment both targetedand utilised

the whole body. Idiocy came to be redefinedas pathologyof normalbodily function-

ing and not simplyan organic impairment.The corollaryto thisview was a method

that aimed at invigoratingthe torpidwill,nervous and muscular systemsof the idiot.

There are many points in Seguin's systemof physiologicaleducation that derive

some degree of influencefromItard. Principal among these, forthis paper at least,

are, firstly,the development of a systemof experimentalpedagogy that targetsthe

This content downloaded from 155.247.167.222 on Wed, 15 May 2013 05:48:40 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

570 M. K. Simpson

body in orderto educate the mind. For Seguin thisis relatedto anotherpivotal

move-namely,the conceptualdiffusion of idiocythroughout thebody-regarding it

notsimplyas locatedinthebrainormind(see,forexample,Seguin,1976). Secondly,

we havethemedicalisation ofpedagogy.Thirdly,bothsharetheview,establishedfor

themostpartbyRousseau(forexample,Rousseau,1973a, 1991), thateducationwas

a processof producingcitizens;'a constantascensionon the steps leadingfrom

isolationto sociability'(Seguin,1866,p. 209).

The firsttwo of thesepointsare closelyinterlinked. In additionto the already

mentionedcontextualpoints mentioned,Itard's work also takes place against

backgroundshiftsin westernmedicine(Lesch, 1984) towardsphysiology, infusing

the inertanatomicalbodywithtime,lifeand movement.The physiological turnin

medicinewas profoundly important for the pedagogicalsystems of both Itard and

Seguin. Both emphasisedthe stimulation and harnessingof the functionalsystems

of the body; forSeguin,however,it was to prove even more significant. By the

timeSeguinproducedthe seminaliterationof his systemin 1866, physiology not

only lay at the heartof the treatment of idiocy,but idiocyitselfhad come to be

redefinedas a physiologicaldisorder.The physiologicalmethodwas, therefore,

morethanmerelya systemforthe educationof idiots,it was a directtherapeutic

intervention on idiocyitself(Simpson,1999). Also, in keepingwiththe develop-

ment of a specificallymedicalscience, the physiologicalinstitutionadvances

knowledgeprimarily throughclinicalcase data. Even the institution's teachershad

the dutyplaced upon themby Seguinto recordobservations on the childreneach

day. In thiswaythe scientific pedagogyand treatment of idiocywould advanceby

the dissemination of clinicaldata and the 'repeatedtestsof experience'(Seguin,

1866,p. 278).

These pointsare bestillustrated in Seguin'sconceptofthe 'psycho-physiological

circulus'.The idiotbodyis sluggishandinsensitive. As a resultitprovidesbutill-nour-

ishmentforthemindin termsofthesensorypabulumneededto formthoughtsand

purposiveaction.The physiological method,therefore, aimsto stimulatethebody's

musclesand sensesso as to energisethesenses,floodingthemindwithstimuli,and

bringthe errantbody underthe controlof the mind. This producesa cyclethat

underpins Seguin's method: sensory stimulation-reception-apperception-will-

action-sensory stimulation, and so forth.

The medico-pedagogical constructionofcitizensalso linksthesavageand theidiot

to moraltreatment, whichpermeatesSeguin'ssystemjustat it did forItard's(Kraft,

1961). As withthealienistswhopioneeredit (Pinel,1962; Tuke, 1996), moraltreat-

mentdoes not merely,or evenprincipally, implya 'humane'or 'kindly'approach;

neitherdoes it referto the moralityof the physicianor educator.Moral treatment

emphasisesthe social relations of the subject as the primarytargetof treatment

(Foucault,1965); indeed,itis theprocessoftheirsubjectionand subjectification: 'the

systematic actionofa willupon another, in view of itsimprovement' (Seguin,1866,

p. 214). The rationaleof the moralmethodis quite clearforits proponents;it is

proposed forreasonsof its effectiveness, ratherthan its ethicality(Scull, 1989).

Seguin reiterates

the same objectiveof the 'moralisation' oftheidiot.

This content downloaded from 155.247.167.222 on Wed, 15 May 2013 05:48:40 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Education,colonialismand idiocy 571

Anotherfeatureof the discourse on the savage of Aveyronthatis also worthnoting

is the familiarconnection between the savage state, social being and solitude. The

idiot came to be identifiedwiththose unable to be educated by virtueof intellectual

defector deficiency.The idiot was stillthe idiotes,the solitary;socially cut offby the

failingsof his body; unable to followthe developmentalpath to civilisation.The idiot

was not uneducable because idiotic, but idiotic because uneducable. The idiot was

one who proved unable to become disciplined,at least by means ofthe normalinstru-

mentsofsocialisation.

The savage,however,had fadedfromthelexiconofidiocy.The fragmentation of

theoriesofsocial and racialevolution,unencumbered bythelinearsequentialism of

theeighteenth century,reliedlessand lesson explanations ofsocialand environmen-

tal learningto accountforhumandiversity. Social relationsamongthe uncivilised

differ morein kindthanin quantity,and theanthropological studyoftheexoticother

splitsdecisivelyfromthepsychological studyof abnormality. That said, recapitula-

tiontheory-thebeliefthatthedevelopment oftheembryoin thewombfolloweda

similarevolutionaryline as the species of which it is a member (Borthwick,1994)-

leftopen the door forthe continuationof racial theoriesof idiocy. In Seguin's case,

idiocy constitutedan arrestedstate of development'analogous to the ... formsof the

lower animals' (1866, p. 40). This opens the way forothereven more sinisterstrate-

gies and conclusions, such as Gobineau's stark conclusions about the intrinsic

inequalityof races (de Gobineau, 1970).

Conclusion

The connections between the colonial attitude and the formationof the modern

discourse on idiocy were several, although largely indirect. First, as Kliewer and

Fitzgerald (2001) observed, thereis a directlink between the discourse of colonial-

ism abroad and internalregulationof deviants at home (i.e. by standingin apparent

exception to the position that ought to occupy by birthin the racial hierarchy).In

the case of idiocy, theirimpassivityto the normal scholastic techniques of disciplin-

ary control implied two things.Firstly,theyhad to be constructedpathologically-

indeed, it had to become possible to even speak of them.Secondly, they became

subject to a formof social contractthatguaranteed,howevernotionally,a basic level

of public provision in exchangefor the surrenderof liberty:a system of domestic

reducciones.

Second, the impact of popular and scientificinterestin the exotic uncivilised

peoples of the new worlds undoubtedlyshaped the conditionsthatmade Itard's work

of such relevance in EnlightenmentFrance. Observers looked to Itard's experiment

forclues to the developmentof a civilisingpedagogy at home and abroad. The savage

of Aveyron was directly analogous to the new world savage. This connection,

however,began to break down in the earlynineteenthcenturyas the linearmodels on

which theyrested began to give way. The residue of this attitude,however,remains

in the threadof Itard's workthatruns directlyinto thatof Seguin and the pedagogical

treatmentof idiocy. The education of idiots aims directlyat the stimulationof their

This content downloaded from 155.247.167.222 on Wed, 15 May 2013 05:48:40 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

572 M. K. Simpson

relationswiththe physicaland social world-it is a release fromthe putativesolitude

that definestheirverybeing.

This leads to a thirdconnection, which is that,even afterthe two discourses split

into ethnology and psychology and move in differentdirections, the 'civilising

impulse' at home, withchildrenand idiots, and abroad, among 'backward' colonised

nations, continued unabated. Education was firmlyestablished as the process of

transforming its targets-child, idiot, savage-into social subjects. Neither makes the

same assumptions about equality of potential,but each sees the objective of produc-

ing social beings, fittedforlife according to the demands of Eurocentric culture,as

an unquestionably necessary duty forteacher/coloniserand aspiration forthe child/

idiot/native.

Each stationshouldbe likea beaconon theroadtowardsbetter a centerfortrade

things,

ofcourse,butalsoforhumanizing, improving, (Conrad,1990,p. 29)

instructing.

A fourth pointofconnectionis themorecomplicatedone thatwe findin thefigure

of the savage. To begin with, the wild boy of Aveyronwas seen as paralleling the

uncivilisedpeoples of the new world. Subsequently, Seguin would reinterpretItard's

worktakingthe assumptionthatVictorwas afterall an idiot. This connectionis there-

foreone thatproduces a relationshipdefiningdifference,ratherthan similitude.The

constructionof the exotic savage, the domestic savage and the idiot were all linkedto

the project of constructingthe civilised,white,European man.

In this sense the savage and the idiot share much in common withthose placed at

the boundaries by the Enlightenment,such as women, children and criminals; in

being constructedas Other,theirown voices are silenced (cf. Spivak, 2003). They are

spoken foras well as about: 'The Other is silenced becauseshe is Other' (Kitzinger&

Wilkinson, 1996, p. 10). Certainly,these eventsmarkthe beginningof a long silence

forpeople withintellectual

disabilities.However,it seemsequallyclearthatneither

the idiot nor the savage had a voice priorto the point of theirconstructionqua idiot

and savage preciselybecause to take any otherview would lead us into the paradox of

retrospectively incorporatingvoices into the Other anachronistically.

Finally,we should note that there are of course many other aspects to the raciali-

sation of idiocythatwould come later: Carl Vogt's positingof the idiot as the 'missing

link'betweennegro and ape (Jahoda, 1999); JohnLangdon Down's racial typography

of idiocy (Down, 1866; Kevles, 2004; Wright,2004), and perhaps most significantly,

eugenics (for example, Karier, 1976; Trent, 1994). What this paper has demon-

strated are some of the ways in which complex interconnectionsbetween race,

empire,education and idiocy can produce concepts and practicesthatleave a residue

of imperialistthinking,even when the question of empire itselfbecomes silenced.

References

Axtell,J.(1992) Beyond1492:encounters

inColonialNorth

America (NewYork,OxfordUniversity

Press).

Borthwick, C. (1994) Racism,IQ andDown'ssyndrome, andSociety,

Disability 11(3), 403-410.

This content downloaded from 155.247.167.222 on Wed, 15 May 2013 05:48:40 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Education,colonialismand idiocy 573

Chauchetibre, C. (2000) LetterofOctober14, 1682, in: A. Greer(Ed.) TheJesuitrelations: nativesand

missionaries NorthAmerica(Boston,MA, Bedford/St.

in seventeenth-century Martin's),147-154.

Conrad,J.(1990) Heartofdarkness(New York,Dover).

Cooper, N. (2001) Francein Indochina:colonialencounters (New York,Berg).

Darwin, C. (1930) Thedescent ofman (London, Watts& Co.).

de Gobineau, A. (1970). Gobineau: selectedpoliticalwritings(M. D. Biddiss, Ed. and intro.)

(London, JonathanCape).

Dorsey,P. A. (1998) Going to school withsavages: authorshipand authorityamongtheJesuitsof

New France, Williamand Mary Quarterly, 55(3), 399-420.

Down, J.L. (1866) Observationson an ethnicclassificationof idiots,ClinicalLectureReportsofthe

LondonHospital,3, 259-262.

Ernct,S. (1995) Un admirableechec: Victorde l'Aveyron,l'enfantsauvage,Les TempsModernes,

50, 151-182.

Esquirol, J. E. D. (1965) Mental maladies:a treatiseon insanity(New York, Hafner Publishing

Company).

Foucault, M. (1965) Madness and civilization:a history ofinsanityin theage ofreason(New York,

Pantheon).

Foucault,M. (1970) Theorderofthings: an archaeology ofthehumansciences(New York,Routledge).

Galton,F. (1869) Hereditary genius:an inquiryintoitslawsand consequences (London, Macmillan).

Gay, P. (1977) TheEnlightenment, an interpretation:thescienceoffreedom (New York,W.W. Norton).

Gaynor,J.(1972) The 'failure'ofJ.M.G. Itard,JournalofSpecialEducation,7, 439-444.

Geremek,B. (1990) The marginalman, in: J. le Goff(Ed.) The medievalworld(London, Collins

and Brown),347-372.

Godwin, W. (1971) Enquiryconcerning politicaljustice(K. C. Carter,abridgedand ed. from3rd

edn) (New York,OxfordUniversityPress).

Greer, A. (Ed.) (2000) The Jesuitrelations:nativesand missionaries in seventeenth-century North

America(Boston,MA, Bedford/St. Martin's).

Itard,J. (1972a) Of the firstdevelopmentsof the young savage of Aveyron,in: The wild boyof

Aveyron(London, NLB), 91-140.

Itard,J.(1972b) Reporton theprogressofVictorofAveyron,in: ThewildboyofAveyron (London,

NLB), 141-179.

Jahoda,G. (1999) Imagesofsavages:ancientrootsofmodern prejudicein western culture(New York,

Routledge).

Jenkins,R. (1998) Culture, classificationand (in)competence,in: R. Jenkins(Ed.) Questionsof

competence: and intellectual

culture,classification disability(Cambridge, CambridgeUniversity

Press), 1-24.

Kant, I. (1974) Anthropology froma pragmatic pointofview(The Hague, MartinusNijhoff).

Karier,C. J. (1976) Testingfororderand controlin the corporateliberalstate,in: N. J.Block &

G. Dworkin(Eds) TheIQ controversy (New York,Pantheon),339-373.

Kevles, D. J.(2004) 'Mongolian imbecility':race and itsrejectionin theunderstanding of a mental

disease, in: S. Noll & J.Trent,Jr.(Eds) Mentalretardation inAmerica:a historical reader(New

York,New York UniversityPress), 120-129.

Kitzinger,C. & Wilkinson,S. (1996) Theorizingrepresenting the Other,in: S. Wilkinson& C.

Kitzinger(Eds) Representing theOther:a feminism and psychology reader(Thousand Oaks, CA,

Sage), 1-32.

Kliewer, C. & Fitzgerald,L. M. (2001) Disability,schooling,and the artifactsof colonialism,

TeachersCollegeRecord,103(3), 450-470.

Kraft,I. (1961) Edward Seguin and the 19th centurymoral treatmentof idiots,Bulletinof the

HistoryofMedicine,35, 393-418.

Kriegleder,W. (2000) The AmericanIndian in Germannovelsup to the 1850s, GermanLifeand

Letters,53(4), 487-498.

Lane, H. (1976) ThewildboyofAveyron(Cambridge,MA, HarvardUniversity Press).

This content downloaded from 155.247.167.222 on Wed, 15 May 2013 05:48:40 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

574 M. K. Simpson

le Jeune,P. (2000) On thegood thingswhichare foundamong theIndians,in: A. Greer (Ed.) The

Jesuitrelations:nativesand missionaries in seventeenth-century NorthAmerica (Boston, MA,

Bedford/St. Martin's),32-35.

Lesch, J.E. (1984) Scienceand medicine inFrance:theemergence ofexperimental 1790-1855

physiology,

(Cambridge,MA, HarvardUniversityPress).

Newton,M. (2002) Savage girlsand wildboys:a history offeralchildren (London, Faber and Faber).

Pinel, P. (1962) A treatiseon insanity(New York,HafnerPublishingCo.).

Poole, R. (1825). An essayon education,applicabletochildren ingeneral;thedefective; thecriminal;the

poor;theadultand aged (Edinburgh,Waugh and Innes).

Rodway,A. E. (Ed.) (1952) Godwinand theage oftransition (London, George G. Harrap and Co.).

Rose, N. (1985) Thepsychological complex(London, Routledgeand Kegan Paul).

Rossiaud, J. (1990) The city-dweller and lifein citiesin towns,in: J. le Goff(Ed.) The medieval

world(London, Collins and Brown), 139-179.

Rousseau, J.-J.(1973a) A discourse on political economy,in: The social contractand discourses

(London, Dent).

Rousseau, J.-J.(1973b) A discourseon the originof inequality,in: Thesocialcontract and discourses

(London, Dent).

Rousseau, J.-J.(1991) Emileoron education(New York,Penguin).

Said, E. (1991) Orientalism (New York,Penguin).

Scull, A. (1989) Social order/mental disorder:Anglo-American psychiatry in historicalperspective

(Berkeley,CA, Universityof CaliforniaPress).

Seguin,E. (1866) Idiocyanditstreatment bythephysiological method (New York,WilliamWood & Co.).

Seguin, E. (1976) Psycho-physiological trainingof an idiotichand, in: M. Rosen, G. R. Clark &

M. S. Kivitz (Eds) The history ofmentalretardation (vol. 1) (Baltimore,MD, UniversityPark

Press), 163-167.

Shattuck,R. (1980) Theforbidden experiment: thestoryofthewildboyofAveyron (New York, Farrar

StrausGiroux).

Simpson,M. K. (1999) Bodies, brainsand behaviour:the returnof the threestooges in learning

disability,in: M. Corker& S. French (Eds) Disabilitydiscourse (Buckingham,Open University

Press), 148-156.

Smith,S. S. (2001) An essay on the causes of the varietyof complexionand figurein the human

species, in: R. Bernasconi (Ed.) Conceptsof race in the eighteenth century(vol. 6) (Bristol,

Thoemmes).

Spivak,G. C. (2003) Can the subalternspeak?,in: L. Cahoone (Ed.) Frommodernism topostmod-

ernism:an anthology (Malden, MA, Blackwell),319-341.

Street,B. V. (1975) The savage in literature: representationsof 'primitive' societyin Englishfiction

1858-1920 (London, Routledgeand Kegan Paul).

Trent,J.(1994) Inventing thefeeblemind:a history ofmentalretardation in theUnitedStates(Berke-

ley,CA, Universityof CaliforniaPress).

Tuke, S. (1996). Description oftheretreat: an institutionnear Yorkforinsanepersonsofthesocietyof

friends(London, Process Press).

Vaughan, A. T. (1978) 'Expulsion of the salvages': Englishpolicy and the VirginiaMassacre of

1622, The Williamand Mary Quarterly, 35(1), 57-84.

White,C. (1799) An accountoftheregulargradationofmen,and in different animalsand vegetables;

andfromtheformer tothelatter(London, C. Dilly).

Williams,H. (2003) Writingto Paris: poets, nobles and savages in nineteenth-century Brittany,

FrenchStudies,57(4), 475-490.

Wright,D. (2004) Mongols in our midst:JohnLangdon Down and the ethnicclassificationof

idiocy,1858-1924, in: S. Noll & J.W. Trent,Jr.(Eds) Mentalretardation inAmerica:a histori-

cal reader(New York,New York University Press), 92-119.

Yousef,N. (2001) Savage or solitary?The wild child and Rousseau's man of nature,Journalofthe

HistoryofIdeas, 62(2), 245-263.

This content downloaded from 155.247.167.222 on Wed, 15 May 2013 05:48:40 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

You might also like

- Luigi Luca Cavalli-Sforza Genes, Peoples and Languages 2001Document245 pagesLuigi Luca Cavalli-Sforza Genes, Peoples and Languages 2001André Cidade100% (2)

- The Penguin Dictionary of ProverbsDocument8 pagesThe Penguin Dictionary of Proverbslucky budy33% (3)

- Cultural Exchanges between Brazil and FranceFrom EverandCultural Exchanges between Brazil and FranceRegina R. FélixNo ratings yet

- Kearney, Michael (1986) PDFDocument32 pagesKearney, Michael (1986) PDFYume Diminuto-Habitante Del-BosqueNo ratings yet

- InvoiceDocument1 pageInvoicelucky budyNo ratings yet

- Wag The Dog EssayDocument6 pagesWag The Dog Essaykbmbwubaf100% (2)

- MacLeod Nature & Empire 2000Document14 pagesMacLeod Nature & Empire 2000paulusmilNo ratings yet

- Textbook Ebook Theorising Childhood 1St Ed Edition Claudio Baraldi All Chapter PDFDocument43 pagesTextbook Ebook Theorising Childhood 1St Ed Edition Claudio Baraldi All Chapter PDFrita.cargle173100% (3)

- Conclusion The Anatomy of Blackness.Document10 pagesConclusion The Anatomy of Blackness.Ricardo SoaresNo ratings yet

- Dreams of Europe and Western Civilization: Culture and FrontiersDocument15 pagesDreams of Europe and Western Civilization: Culture and Frontiersyogeshwithraj3914No ratings yet

- Final Exam IdeasDocument7 pagesFinal Exam IdeasMarkee JoyceNo ratings yet

- The Shackle HistoryDocument6 pagesThe Shackle HistoryMAli fahadNo ratings yet

- Why Interculturalidad Is Not InterculturalityDocument25 pagesWhy Interculturalidad Is Not InterculturalityValentina PellegrinoNo ratings yet

- Stolcke - Talking Culture: New Boundaries, New Rhetorics of Exclusion in EuropeDocument25 pagesStolcke - Talking Culture: New Boundaries, New Rhetorics of Exclusion in EuropeRodolfo Rufián RotoNo ratings yet

- Stolcke v. 1995. New Boundaries New Rhetorics of Exclusion in Europe. Current Anthropology Vol. 36 No. 1 Pp. 1 24Document25 pagesStolcke v. 1995. New Boundaries New Rhetorics of Exclusion in Europe. Current Anthropology Vol. 36 No. 1 Pp. 1 24Andrea AlvarezNo ratings yet

- In Search of The InterculturalDocument11 pagesIn Search of The InterculturalΔημήτρης ΑγουρίδαςNo ratings yet

- Aesthetico-Cultural Cosmopolitanism and French Youth: The Taste of the WorldFrom EverandAesthetico-Cultural Cosmopolitanism and French Youth: The Taste of the WorldNo ratings yet

- Modern Western Civilization Research Paper TopicsDocument7 pagesModern Western Civilization Research Paper Topicsefkm3yz9No ratings yet

- On Coloniality Colonization of Languages PDFDocument35 pagesOn Coloniality Colonization of Languages PDFhenaretaNo ratings yet

- Rachik, Hassan, Moroccan - IslamDocument16 pagesRachik, Hassan, Moroccan - IslamHassan RachikNo ratings yet

- Open University EssaysDocument5 pagesOpen University Essaysezmpjbta100% (2)

- Fortes StructureDescentGroups 1953Document26 pagesFortes StructureDescentGroups 1953Francois G. RichardNo ratings yet

- 1982 - R. J. Vincent - Race in International RelationsDocument14 pages1982 - R. J. Vincent - Race in International RelationsSuely LimaNo ratings yet

- Knowledge Justice As Global Justice: Epistemicide, Decolonialising The University and The Struggle For Planetary SurvivalDocument19 pagesKnowledge Justice As Global Justice: Epistemicide, Decolonialising The University and The Struggle For Planetary SurvivalAlice FeldmanNo ratings yet

- Meyer - Fortes 1953Document26 pagesMeyer - Fortes 1953JHollomNo ratings yet

- Amsterdam University Press Secularism, Assimilation and The Crisis of MulticulturalismDocument25 pagesAmsterdam University Press Secularism, Assimilation and The Crisis of MulticulturalismAissatou FAYENo ratings yet

- Braudel Annales HalfDocument17 pagesBraudel Annales HalfShathiyah KristianNo ratings yet

- Global Citizenship and the University: Advancing Social Life and Relations in an Interdependent WorldFrom EverandGlobal Citizenship and the University: Advancing Social Life and Relations in an Interdependent WorldNo ratings yet

- A Critique of Eurocentric Social Science and The Question of AlternativesDocument10 pagesA Critique of Eurocentric Social Science and The Question of AlternativesJaideep A. PrabhuNo ratings yet

- Evirment Policies of British IndiaDocument11 pagesEvirment Policies of British IndiaShivansh PamnaniNo ratings yet

- Impressionism EssayDocument7 pagesImpressionism Essayafabkkgwv100% (2)

- On Ethnographic Authority (James Clifford)Document30 pagesOn Ethnographic Authority (James Clifford)Lid IaNo ratings yet

- Mapping The WorldDocument11 pagesMapping The WorldTrevor SinghNo ratings yet

- Heterogeneities Net: Materialities, Globalities, SpatialitiesDocument20 pagesHeterogeneities Net: Materialities, Globalities, SpatialitiespedroacaribeNo ratings yet

- Violence: Louise EdwardsDocument712 pagesViolence: Louise EdwardsMrNegustiNo ratings yet

- Africa in The World A History of ExtraversionDocument52 pagesAfrica in The World A History of ExtraversionAhmed AbdeltawabNo ratings yet

- Los Invisibles: A History of Male Homosexuality in Spain, 1850-1940From EverandLos Invisibles: A History of Male Homosexuality in Spain, 1850-1940Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1)

- Theorising Childhood: Citizenship, Rights and ParticipationFrom EverandTheorising Childhood: Citizenship, Rights and ParticipationNo ratings yet

- James Joyce and The English ViceDocument14 pagesJames Joyce and The English Vicejanna100% (1)

- Abandoned Children of The Italian RenaisDocument3 pagesAbandoned Children of The Italian RenaisSahil BhasinNo ratings yet

- Society For Comparative Studies in Society and History: Cambridge University PressDocument29 pagesSociety For Comparative Studies in Society and History: Cambridge University PressZeru YacobNo ratings yet

- The Scholastic Method in Medieval Education: An Inquiry Into Its Origins in Law and Theology - George MakdisiDocument23 pagesThe Scholastic Method in Medieval Education: An Inquiry Into Its Origins in Law and Theology - George MakdisikalligrapherNo ratings yet

- Britannia's children: Reading colonialism through children's books and magazinesFrom EverandBritannia's children: Reading colonialism through children's books and magazinesNo ratings yet

- SOYER, Faith, Culture Fear ,, Islamophobia in Early Modern Spain ,, ISLAM, GEWALT, MYT, THEORY, OKDocument20 pagesSOYER, Faith, Culture Fear ,, Islamophobia in Early Modern Spain ,, ISLAM, GEWALT, MYT, THEORY, OKDienifer VieiraNo ratings yet

- The Process of Social ChangeDocument20 pagesThe Process of Social Changeeldad.shahar1592No ratings yet

- Making Sense of Our Everyday ExperiencesDocument26 pagesMaking Sense of Our Everyday ExperiencesMary Joy Dailo100% (1)

- CR David CahillDocument11 pagesCR David CahillCorbel VivasNo ratings yet

- BODIAN, Mirian - Men of The Nation PDFDocument30 pagesBODIAN, Mirian - Men of The Nation PDFLuca BrasiNo ratings yet

- Oral History and MigrationDocument15 pagesOral History and MigrationArturo CristernaNo ratings yet

- Within Between Above and Beyond Pre Positions For A History of The Internationalisation of Educational Practices and KnowledgeDocument18 pagesWithin Between Above and Beyond Pre Positions For A History of The Internationalisation of Educational Practices and KnowledgeZenaideCastroNo ratings yet

- Origins of the Celts: As you have never read them before !From EverandOrigins of the Celts: As you have never read them before !No ratings yet

- Carneiro EnlightenmentSciencePortugal 2000Document30 pagesCarneiro EnlightenmentSciencePortugal 2000Hori GagakuNo ratings yet

- Journal of Refugee Studies-1990-MARX-189-203 PDFDocument15 pagesJournal of Refugee Studies-1990-MARX-189-203 PDFimisa2No ratings yet

- Understanding Social Distance in Intercultural CommunicationDocument20 pagesUnderstanding Social Distance in Intercultural CommunicationpotatoNo ratings yet

- The American Society For EthnohistoryDocument16 pagesThe American Society For EthnohistoryAgustina LongoNo ratings yet

- Tu Dimunn Pu Vini Kreol The Mauritian CR PDFDocument17 pagesTu Dimunn Pu Vini Kreol The Mauritian CR PDFkhaw amreenNo ratings yet

- Hannerz - Ulf - The World in Creolisation 1987Document15 pagesHannerz - Ulf - The World in Creolisation 1987elianeapvNo ratings yet

- Inaugural LectureDocument24 pagesInaugural LectureThabiso EdwardNo ratings yet

- Definition of ConceptsDocument8 pagesDefinition of ConceptsKamalito El CaballeroNo ratings yet

- Amina WadudDocument9 pagesAmina Wadudlucky budyNo ratings yet

- Mock Exam CorrectionDocument5 pagesMock Exam Correctionlucky budyNo ratings yet

- Revision Summarize The Following ParagraphsDocument3 pagesRevision Summarize The Following Paragraphslucky budyNo ratings yet

- Ware Top Five Regrets of The Dying AeJT2 FormattedDocument2 pagesWare Top Five Regrets of The Dying AeJT2 Formattedlucky budy100% (2)

- French Alphabetical List of 681 Most Common French VerbsDocument5 pagesFrench Alphabetical List of 681 Most Common French Verbslucky budyNo ratings yet

- Capsicum Annuum: Antibacterial Activities of Endophytic Fungi From L. (Siling Labuyo) Leaves and FruitsDocument10 pagesCapsicum Annuum: Antibacterial Activities of Endophytic Fungi From L. (Siling Labuyo) Leaves and FruitsMeynard Angelo M. JavierNo ratings yet

- BC 30s (2P)Document2 pagesBC 30s (2P)PT Bintang Baru MedikaNo ratings yet

- Il Pleut Prevert ProjectDocument1 pageIl Pleut Prevert Projectapi-239640128No ratings yet

- LMS Project ThesisDocument46 pagesLMS Project Thesisraymar2kNo ratings yet

- Christian Leadership Who Is A Christian?Document10 pagesChristian Leadership Who Is A Christian?Kunle AkingbadeNo ratings yet

- Personal Nutrition 9th Edition Boyle Solutions ManualDocument32 pagesPersonal Nutrition 9th Edition Boyle Solutions Manualthoabangt69100% (29)

- Notes On Purposive CommunicationDocument27 pagesNotes On Purposive CommunicationChlea Marie Tañedo AbucejoNo ratings yet

- WhitePaper WePowerDocument46 pagesWhitePaper WePowerOnur OnukNo ratings yet

- Social MediaDocument4 pagesSocial MediaJeff_Yu_5215No ratings yet

- Reynolds Number, Department of Biomedical Engineering, University of MalayaDocument7 pagesReynolds Number, Department of Biomedical Engineering, University of MalayaMuhammad Faiz Bin ZulkefleeNo ratings yet

- How To Impress Someone at First MeetingDocument1 pageHow To Impress Someone at First MeetingMohammad Fahim HossainNo ratings yet

- L&T Aquaseal Butterfly Check Valves PDFDocument24 pagesL&T Aquaseal Butterfly Check Valves PDFnagtummalaNo ratings yet

- DR Anand Bajpai - DelhiDocument16 pagesDR Anand Bajpai - DelhiDrAnand BajpaiNo ratings yet

- P Block Elements Group 15Document79 pagesP Block Elements Group 1515 Kabir Sharma 10 HNo ratings yet

- English Project Work Xii 2022-23Document2 pagesEnglish Project Work Xii 2022-23Unusual Crossover0% (1)

- 2PGW Lessons Learned 01Document135 pages2PGW Lessons Learned 01Jonathan WeygandtNo ratings yet

- Merton On Structural FunctionalismDocument6 pagesMerton On Structural FunctionalismJahnaviSinghNo ratings yet

- List of IP Reference Substances Available at IPC, Ghaziabad List of ImpuritiesDocument4 pagesList of IP Reference Substances Available at IPC, Ghaziabad List of ImpuritiesUrva VasavadaNo ratings yet

- Engineers Syndicate Company ProfileDocument17 pagesEngineers Syndicate Company ProfileSakshi NandaNo ratings yet

- Abap Code PracticeDocument35 pagesAbap Code PracticeAkhilaNo ratings yet

- Cluster SamplingDocument3 pagesCluster Samplingken1919191100% (1)

- Padre Island National Seashore Superintendent's StatementDocument7 pagesPadre Island National Seashore Superintendent's StatementcallertimesNo ratings yet

- TrabDocument3 pagesTrabwilliam.123No ratings yet

- ShowPDF Paper - AspxDocument14 pagesShowPDF Paper - AspxShawkat AhmadNo ratings yet

- Symbiosis School of Banking and Finance (SSBF)Document20 pagesSymbiosis School of Banking and Finance (SSBF)bkniluNo ratings yet

- Pointers, Virtual Functions and PolymorphismDocument9 pagesPointers, Virtual Functions and PolymorphismSANJAY MAKWANANo ratings yet

- Tecalemit Grease NipplesDocument2 pagesTecalemit Grease NipplesAntonius DickyNo ratings yet

- Analysis of ToothGrowth Data SetDocument4 pagesAnalysis of ToothGrowth Data SetJavo SantibáñezNo ratings yet

- Sample Test 1Document3 pagesSample Test 1Bình Phạm ThịNo ratings yet

- Critical Thinking Definitions PDFDocument2 pagesCritical Thinking Definitions PDFAlpha Niño S SanguenzaNo ratings yet