Professional Documents

Culture Documents

A 12-Week, Randomized, Controlled Trial With A 4-Week Randomized Withdrawal Period To Evaluate The Effi Cacy and Safety of Linaclotide in Irritable Bowel Syndrome With Constipation

A 12-Week, Randomized, Controlled Trial With A 4-Week Randomized Withdrawal Period To Evaluate The Effi Cacy and Safety of Linaclotide in Irritable Bowel Syndrome With Constipation

Uploaded by

debby claudiOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

A 12-Week, Randomized, Controlled Trial With A 4-Week Randomized Withdrawal Period To Evaluate The Effi Cacy and Safety of Linaclotide in Irritable Bowel Syndrome With Constipation

A 12-Week, Randomized, Controlled Trial With A 4-Week Randomized Withdrawal Period To Evaluate The Effi Cacy and Safety of Linaclotide in Irritable Bowel Syndrome With Constipation

Uploaded by

debby claudiCopyright:

Available Formats

1714 ORIGINAL CONTRIBUTIONS nature publishing group

see related editorial on page 1726

CME

FUNCTIONAL GI DISORDERS

A 12-Week, Randomized, Controlled Trial With a

4-Week Randomized Withdrawal Period to Evaluate

the Efficacy and Safety of Linaclotide in Irritable

Bowel Syndrome With Constipation

Satish Rao, MD1, Anthony J. Lembo, MD2, Steven J. Shiff, MD3, Bernard J. Lavins, MD4, Mark G. Currie, PhD4, Xinwei D. Jia, PhD3,

Kelvin Shi, PhD3, James E. MacDougall, PhD4, James Z. Shao, MS4, Paul Eng, PhD3, Susan M. Fox, PhD3, Harvey A. Schneier, MD3,

Caroline B. Kurtz, PhD4 and Jeffrey M. Johnston, MD4

OBJECTIVES: Linaclotide is a minimally absorbed guanylate cyclase-C agonist. The objective of this trial was

to determine the efficacy and safety of linaclotide in patients with irritable bowel syndrome with

constipation (IBS-C).

METHODS: This phase 3, double-blind, parallel-group, placebo-controlled trial randomized IBS-C patients to

placebo or 290 μg oral linaclotide once daily in a 12-week treatment period, followed by a 4-week

randomized withdrawal (RW) period. There were four primary end points, the Food and Drug

Administration’s (FDA’s) primary end point for IBS-C (responder: improvement of ≥30% in average

daily worst abdominal pain score and increase by ≥1 complete spontaneous bowel movement (CSBM)

from baseline (same week) for at least 50% of weeks assessed) and three other primary end points,

based on improvements in abdominal pain and CSBMs for 9/12 weeks. Adverse events (AEs) were

monitored.

RESULTS: The trial evaluated 800 patients (mean age = 43.5 years, female = 90.5%, white = 76.9%). The FDA

end point was met by 136/405 linaclotide-treated patients (33.6%), compared with 83/395

placebo-treated patients (21.0%) (P < 0.0001) (number needed to treat: 8.0, 95% confidence

interval: 5.4, 15.5). A greater percentage of linaclotide patients, compared with placebo patients,

reported for at least 6/12 treatment period weeks, a reduction of ≥30% in abdominal pain (50.1

vs. 37.5%, P = 0.0003) and an increase of ≥1 CSBM from baseline (48.6 vs. 29.6%, P < 0.0001).

A greater percentage of linaclotide patients vs. placebo patients were also responders for the other

three primary end points (P < 0.05). Significantly greater improvements were seen in linaclotide

vs. placebo patients for all secondary end points (P < 0.001). During the RW period, patients

remaining on linaclotide showed sustained improvement; patients re-randomized from linaclotide

to placebo showed return of symptoms, but without worsening of symptoms relative to baseline.

Diarrhea, the most common AE, resulted in discontinuation of 5.7% of linaclotide and 0.3% of

placebo patients.

CONCLUSIONS: Linaclotide significantly improved abdominal pain and bowel symptoms associated with IBS-C for at

least 12 weeks; there was no worsening of symptoms compared with baseline following cessation of

linaclotide during the RW period.

Am J Gastroenterol 2012; 107:1714–1724; doi:10.1038/ajg.2012.255; published online 18 September 2012

1

Section of Gastroenterology/Hepatology, Georgia Health Sciences University, Augusta, Georgia, USA; 2Division of Gastroenterology, Department of Medicine, Beth

Israel Deaconess Medical Center, Harvard Medical School, Boston, Massachusetts, USA; 3Forest Research Institute, Jersey City, New Jersey, USA; 4Ironwood

Pharmaceuticals, Inc., Cambridge, Massachusetts, USA. Correspondence: Jeffrey M. Johnston, MD, Ironwood Pharmaceuticals, Inc., 301 Binney Street,

Cambridge, Massachusetts 02142, USA. E-mail: jjohnston@ironwoodpharma.com

Portions of this manuscript were presented as an oral presentation at Digestive Disease Week, May 2011, Chicago, IL.

Received 2 April 2012; revised 20 June 2012; accepted 24 June 2012

The American Journal of GASTROENTEROLOGY VOLUME 107 | NOVEMBER 2012 www.amjgastro.com

Linaclotide in IBS-C 1715

INTRODUCTION included in this trial to assess the effect of discontinuing treat-

Irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) is a common gastrointestinal ment with linaclotide.

disorder characterized by frequent and intermittent episodes of

FUNCTIONAL GI DISORDERS

abdominal pain and abdominal discomfort that are associated with

altered bowel habits (1,2). The symptoms of IBS not only adversely METHODS

affect a patient’s health-related quality of life (3) but also place a Trial design

significant financial burden on society due to reduced work pro- This multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-control-

ductivity and increased use of healthcare-related resources (4,5). led, parallel-group trial was conducted at 118 outpatient clinical

IBS with constipation (IBS-C) affects approximately one-third of research centers (111 in the United States, 7 in Canada) from 14

IBS patients (3), occurs more commonly in women than men (6), July 2009 (first patient enrolled) to 12 July 2010 (last patient com-

and frequently includes additional symptoms, such as abdomi- pleted). The protocol and all trial procedures were approved by

nal bloating, hard stools, straining, and sensation of incomplete an Institutional Review Board, and the trial was designed, con-

evacuation (7,8). ducted, and reported in accordance with the principles of Good

Traditional therapies for IBS-C, generally directed towards the Clinical Practice guidelines. All patients gave written informed

patient’s predominant symptoms (9), are frequently associated with consent before their participation in the trial.

patient dissatisfaction (10). More recent therapies, including tegas- After a screening period of up to 21 days followed by a pre-

erod and lubiprostone, have been shown to improve global symp- treatment baseline period of 14–21 days, eligible patients were

toms of IBS-C (9). Tegaserod, a 5-HT4 partial agonist approved randomly assigned with the use of an interactive voice-response

by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for the short-term system (IVRS) to receive once daily an oral capsule of either

treatment of women with IBS-C, was removed from the market linaclotide 290 μg or placebo, in a 1:1 ratio. Patients who com-

in 2007 due to increased cardiovascular events in patients receiv- pleted all 12 weeks of the double-blind treatment period were

ing the medication. Lubiprostone, a chloride channel activator that eligible to enter the double-blind 4-week RW period in which

was approved by the FDA for the treatment of women with IBS-C patients initially randomized to linaclotide were re-randomized

in 2008, has shown efficacy using a global end point (global symp- (1:1) to linaclotide 290 μg or placebo, and patients previously

tom relief) (11). Given the limited treatments currently available randomized to placebo were assigned to receive linaclotide

for patients with IBS-C, additional therapeutic options would be 290 μg once a day. Randomization assignments were generated

of value. in blocks of four and stratified according to trial center. All spon-

Linaclotide, a minimally absorbed 14-amino-acid peptide sor staff involved in the trial, trial center personnel, and patients

structurally related to the endogenous guanylin peptide family were blinded to the allocation of trial treatment. Trial visits were

of hormones that regulate fluid and electrolyte homeostasis in conducted at screening, at the start of the pretreatment base-

the intestine, binds to and activates GCC (guanylate cyclase-C) line period, at randomization (day 1), throughout the treatment

on the luminal surface of the intestinal epithelium. Activation period (weeks 2, 4, 8, and 12), and at the beginning and end

of GCC results in the generation of cyclic guanosine mono- of the RW period (weeks 13 and 16 (end of trial)). Patients

phosphate (cGMP), which is increased in both the intracel- made daily calls to the IVRS to report their symptoms through-

lular and extracellular compartments. The increase in cGMP out the trial.

within intestinal epithelial cells triggers a signal transduction

cascade activating the cystic fibrosis transmembrane conduct- Trial patients

ance regulator (12). This activation causes secretion of chloride Female and male patients were eligible to participate if they were

and bicarbonate into the intestinal lumen; sodium ions and at least 18 years of age, and met modified Rome II criteria for

water follow, resulting in increased luminal fluid secretion and IBS (18). In the 12 months before the screening visit, eligible

a reflex acceleration of intestinal transit. Extracellular cGMP, patients were to have for at least 12 weeks, which need not be

actively transported out of intestinal epithelial cells, is believed consecutive, abdominal pain, or abdominal discomfort that

to reduce visceral hyperalgesia by modulating the activity of had ≥2 of these three features: (i) relieved with defecation, (ii)

afferent pain fibers (13). In animal models, linaclotide treat- onset associated with a change in frequency of stool, and (iii)

ment accelerated gastrointestinal transit and reduced visceral onset associated with a change in form (appearance) of stool,

nociception (14); in human phase 2 clinical studies, it accele- before starting chronic treatment with tegaserod or lubiprostone

rated colonic transit (15) and improved abdominal pain and (if patients had taken these medications); and < 3 spontaneous

constipation associated with IBS-C (16). Likewise, in two large bowel movements (SBMs) per week (SBM = a bowel move-

phase 3 trials in patients with chronic constipation, linaclotide ment (BM) occurring in the absence of any laxative, supposi-

significantly improved bowel and abdominal symptoms over tory, or enema use during the preceding 24 h), and had at least

12 weeks (17). one additional bowel symptom (straining, lumpy or hard stools,

The objective of this phase 3 clinical trial was to assess the and sensation of incomplete evacuation during > 25% of BMs),

efficacy and safety of linaclotide administered once daily as before starting chronic treatment with tegaserod, lubipros-

an oral capsule at a dose of 290 μg vs. placebo to patients with tone, polyethylene glycol 3350, or any laxative (if patients had

IBS-C. A 4-week randomized withdrawal (RW) period was taken these medications). In addition, patients had to report an

© 2012 by the American College of Gastroenterology The American Journal of GASTROENTEROLOGY

1716 Rao et al.

average score ≥3.0 for daily abdominal pain at its worst (11- Each BM was assessed for sensation of complete bowel empty-

point NRS (numerical rating scale)) as well as an average of < 3 ing (yes/no), stool consistency (7-point BSFS with 1 = “separate

complete SBMs (CSBMs) per week (CSBM = an SBM associated hard lumps like nuts” to 7 = “watery, no solid pieces”), and sever-

FUNCTIONAL GI DISORDERS

with a sense of complete evacuation, as reported by the patient) ity of straining (5-point ordinal scale). Weekly IVRS assessments

and ≤5 SBMs per week during the 14 days immediately before included IBS severity and constipation severity (both using a 5-

randomization (i.e., the baseline period). point ordinal scale), degree of IBS relief (7-point balanced scale),

Patients were excluded if they reported loose (mushy) or and adequate relief of IBS-C symptoms (yes/no). Assessment of

watery stools for > 25% of their BMs during the 12 weeks before satisfaction with the trial-medication’s ability to relieve IBS symp-

screening or, during the baseline period, a BSFS (Bristol Stool toms (5-point ordinal scale) was captured at all study visits follow-

Form Scale) (19) score of 7 (watery, no solid pieces) for any SBM, ing randomization.

or a BSFS score of 6 (fluffy pieces with ragged edges, a mushy

stool) for > 1 SBM. Other key exclusion criteria included history Primary end points. There were four prespecified primary end

of cathartic colon, laxative or enema abuse, ischemic colitis, or points in the trial, which were all responder end points. One of

pelvic floor dysfunction (unless successful treatment had been the four primary end points was based on the FDA recommenda-

documented by a normal balloon expulsion test); bariatric sur- tions for IBS-C trial design and end points in the recently final-

gery for treatment of obesity or surgery to remove a segment of ized guidance for IBS clinical trials (May 2012) (21); a responder

the gastrointestinal tract at any time before the screening visit, for this end point (to be referred to hereafter as “FDA end point”)

surgery of the abdomen, pelvis, or retroperitoneal structures was defined as a patient who met both of the following criteria

during the 6 months before the screening visit, appendectomy in the same week for at least 6 of the 12 weeks of the treatment

or cholecystectomy during the 60 days before the screening visit, period: (i) an improvement of ≥30% from baseline in the average

or other major surgery during the 30 days before the screen- of the daily worst abdominal pain scores (to be referred to here-

ing visit; history of diverticulitis or any chronic condition that after as “abdominal pain”) and (ii) an increase of ≥1 CSBM from

could be associated with abdominal pain or discomfort and baseline. This combined end point was added after the initiation

could confound the assessments in the trial (e.g., inflammatory of the trial, but before completion of enrollment and database

bowel disease, chronic pancreatitis, polycystic kidney disease, lock, with a protocol amendment (no unblinding had occurred).

ovarian cysts, endometriosis, lactose intolerance); family history The other three primary end points also required patients to meet

of a familial form of colorectal cancer. In general, patients were weekly responder definitions, but for at least 9 of the 12 weeks of

excluded if they were taking drugs that could cause constipation the treatment period. These weekly responder definitions were (i)

(e.g., narcotics); however, patients taking certain drugs for IBS an improvement of ≥30% in abdominal pain, (ii) ≥3 CSBMs and

that might be constipating (e.g., tricyclic antidepressants) were an increase of ≥1 CSBM from baseline, and (iii) a combined end

eligible provided that they were on a stable dose for at least 30 point that defined a responder as a patient who met criteria for

days before the screening visit and there was no plan to change both i and ii in the same week.

the dose after the screening visit. Colonoscopy requirements were

based on the American Gastroenterological Association guide- Secondary end points. The secondary end points included

lines (20). Women of childbearing potential were required to use 12-week change from baseline in abdominal pain, abdominal

contraceptives and have a negative serum pregnancy test. Patients discomfort, abdominal bloating, stool frequency (CSBM and

were asked to refrain from making any major lifestyle changes SBM weekly rates), stool consistency (BSFS), and severity of

(e.g., starting a new diet or changing their exercise pattern) straining; secondary responder end points included abdomi-

during the trial. nal pain and CSBM responders (using the individual compo-

Rescue medication (bisacodyl 5 mg tablet or 10 mg suppository) nents of the FDA end point). A number of other additional end

was allowed for severe constipation (i.e., 72 h after the patient’s points were also assessed, including 12-week change from

previous BM or when symptoms became intolerable). Use of res- baseline in abdominal fullness and abdominal cramping, IBS

cue medication was not allowed on the day before, the day of, and symptom severity, constipation severity, adequate relief of

the calendar day after the randomization visit. Patients on a stable, IBS-C symptoms, degree of relief of IBS symptoms, and treat-

continuous regimen of fiber, bulk laxatives, stool softeners, or pro- ment satisfaction.

biotics during the 30 days before the screening visit were allowed

to continue, provided they maintained a stable dosage throughout Safety assessments

the trial. At each scheduled study visit, all patients were asked an open-

ended question regarding adverse events (AEs). Patients reported

Efficacy assessments and end points AEs by recalling instances since the prior visit. The site investiga-

Daily reports by patients to IVRS included symptom ratings of tor assessed all patient-reported AEs and judged each event for

worst abdominal pain, abdominal discomfort, abdominal cramp- severity and relationship to the blinded trial medication. Other

ing, abdominal fullness, and abdominal bloating (all abdominal safety evaluations included physical examinations, electrocardio-

symptoms were measured using an 11-point NRS), as well as gram recordings, vital sign measurements, and standard clinical

the number of BMs and whether rescue medication was used. laboratory tests.

The American Journal of GASTROENTEROLOGY VOLUME 107 | NOVEMBER 2012 www.amjgastro.com

Linaclotide in IBS-C 1717

Pharmacokinetic assessments an ANCOVA (analysis of covariance) model with fixed-effect terms

During the treatment period, a subset of patients had blood for treatment group and geographic region and the correspond-

samples taken at the randomization and week 4 visits to deter- ing baseline value as a covariate. Least-squares means (i.e., means

FUNCTIONAL GI DISORDERS

mine if linaclotide or its active metabolite, MM 419447, could adjusted for the other effects) from the ANCOVA model based

be detected at quantifiable levels in the plasma. on patients’ overall average scores (except for SBMs and CSBMs,

for which the overall weekly rates were calculated) are presented.

Statistical methods and data analysis Geographic region was used as a factor in the analyses rather than

The overall family-wise type I error rate for testing the primary individual trial centers due to the potential for very small numbers

and secondary efficacy end points was controlled at the 0.05 of patients at some trial centers.

significance level using a five-step serial gate-keeping, multi- If a patient dropped out of the trial or otherwise did not report

ple-comparison procedure. Based on this multiple-comparison efficacy data for a particular treatment-period week (patients were

procedure and the results of a previous phase 2b study (16), required to complete at least four IVRS calls during a treatment

a sample size of 400 patients per treatment arm was selected to week), the patient was not considered a responder for that week.

provide >85% overall power to simultaneously detect a differ- An observed-cases approach to missing data was applied to the

ence between the placebo and linaclotide groups for the primary change-from-baseline secondary end points, such that if a patient

end points. dropped out of the trial or otherwise did not report data, the aver-

Responder end points were analyzed using a Cochran– age of the non-missing data over the 12 weeks of the treatment

Mantel–Haenszel (CMH) test controlling for geographic region. period was the patient’s value. Patients were assumed to have not

Continuous change-from-baseline end points were analyzed using had BMs nor taken rescue medication if the corresponding daily

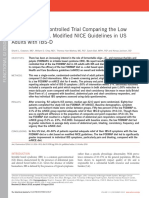

Screening

Patients screened

period

(N = 2424) Excluded (n = 1,621)

• Screen failures (n = 466)

• Pretreatment failures (n = 1,155)

• Did not meet inclusion/exclusion criteria (1,006)

• Adverse event (1)

• Protocol violation (6)

(2 – 3 weeks)

Baseline

• Withdrawal of consent (81)

period

Randomized • Lost to follow-up (34)

(n = 803) • Other (27)

Placebo Linaclotide 290 μg qd

(n = 397) (n = 406)

Discontinued (n = 62) Discontinued (n = 94)

• Adverse event (n = 10) • Adverse event (n = 32)

(12 weeks)

Treatment

• Protocol violation (n = 9) • Protocol violation (n = 10)

period

• Withdrew consent (n = 25) • Withdrew consent (n = 25)

• Lost to follow-up (n = 10) • Lost to follow-up (n = 17)

• Insufficient therapeutic response • Insufficient therapeutic response

(n = 4) (n = 5)

• Other (n = 4) • Other (n = 5)

Completed treatment period Completed treatment period

(n = 335) (n = 312)

Assigned Randomized

Linaclotide 290 μg qd Placebo Linaclotide 290 μg qd

(n = 335) (n = 154) (n = 158)

Randomized withdrawal

Discontinued (n = 10) Discontinued (n = 3) Discontinued (n = 4)

(RW) period

• Adverse event (n = 2) • Adverse event (n = 1) • Adverse event (n = 0)

(4 weeks)

• Protocol violation (n = 1) • Protocol violation (n = 1) • Protocol violation (n = 2)

• Withdrew consent (n = 2) • Withdrew consent (n = 0) • Withdrew consent (n = 0)

• Lost to follow-up (n = 3) • Lost to follow-up (n = 0) • Lost to follow-up (n = 2)

• Insufficient therapeutic response • Insufficient therapeutic response • Insufficient therapeutic response

(n = 0) (n = 1) (n = 0)

• Other (n = 2) • Other (n = 0) • Other (n = 0)

Completed RW period Completed RW period Completed RW period

(n = 325) (n = 151) (n = 154)

Figure 1. Patient flow through the study.

© 2012 by the American College of Gastroenterology The American Journal of GASTROENTEROLOGY

1718 Rao et al.

question was not answered. For the analysis of adequate relief,

Table 1. Summary of patient demographic and baseline

degree of relief of IBS symptoms, and treatment satisfaction, a last

characteristics (ITT population)

observation carried forward method was used. All P values were

FUNCTIONAL GI DISORDERS

based on two-sided tests. Placebo, Linaclotide 290 µg,

All randomized patients who took at least one dose of trial N =395 N =405

medication were included in safety analyses (safety popula- Demographic data

tion). Efficacy analyses were based on the ITT (intent-to-treat) Age (years), mean (range) 43.7 (18–84) 43.3 (19–81)

population, which included all patients in the safety population

≥65 years, n (%) 26 (6.6) 19 (4.7)

who had at least one post-randomization entry of the primary

efficacy assessment (i.e., IVRS assessment of abdominal pain Sex, n (%)

or CSBMs). Female 357 (90.4) 367 (90.6)

Male 38 (9.6) 38 (9.4)

Race, n (%)

RESULTS

White 301 (76.2) 314 (77.5)

Patient disposition, demographics, and baseline characteristics

Of the 2,424 patients who were screened for participation in this Black 75 (19.0) 78 (19.3)

trial, 803 (33%) were randomized to treatment (Figure 1). Two Other 19 (4.8) 13 (3.2)

patients were randomized at more than one trial center but only BMI, mean (s.d.) 27.6 (6.2) 28.3 (6.4)

data from the trial center in which they were first randomized

Abdominal symptoms, mean (s.d.)

were included in statistical analyses. Of the 802 patients who

received double-blind trial medication (safety population), 800 Abdominal paina 5.6 (1.7) 5.7 (1.7)

patients had at least one post-randomization entry of the pri- Abdominal discomforta 6.0 (1.7) 6.2 (1.6)

mary efficacy assessment (ITT population). The demographics Abdominal bloatinga 6.5 (1.9) 6.7 (1.8)

of the ITT population are shown in Table 1. Following comple- a

Abdominal fullness 6.5 (1.8) 6.8 (1.7)

tion of the treatment period, a total of 647 (81%) ITT patients

Abdominal crampinga 5.4 (1.9) 5.4 (1.9)

entered the RW period of the trial, of which 645 received at

least one dose of trial medication and were included in the RW Bowel symptoms, mean (s.d.)

population. Mean compliance with the trial-medication dosing CSBMs/week 0.2 (0.5) 0.2 (0.5)

(assessed by counting pills returned at trial visits) up to trial SBMs/week 1.9 (1.4) 1.9 (1.4)

discontinuation/completion of the 12-week treatment period was b

Stool consistency 2.4 (1.0) 2.3 (1.0)

95 and 94% for the placebo and linaclotide groups, respectively.

c

Compliance with the daily IVRS call-in (patients who completed Straining 3.4 (0.8) 3.6 (0.8)

≥80% of scheduled calls) during the treatment period was 73 and Constipation severityd 3.7 (0.6) 3.8 (0.6)

71% for placebo- and linaclotide-treated patients, respectively. IBS severity d

3.7 (0.6) 3.7 (0.6)

During the pretreatment baseline period, 88% of patients expe-

BMI, body mass index; CSBM, complete SBM; IBS, irritable bowel syndrome;

rienced abdominal pain every day and 76% of patients had no ITT, intent-to-treat; SBM, spontaneous bowel movement.

CSBMs. a

Assessed using an 11-point Numerical Rating Scale: 0=none; 10=very severe.

b

Assessed using the BSFS: 1=separate hard lumps, like nuts (hard to pass);

2=sausage-shaped, but lumpy; 3=like a sausage but with cracks on its surface;

Efficacy results 4=like a sausage or snake, smooth and soft; 5=soft blobs with clear cut edges

For all primary and secondary efficacy end points, the linaclotide (passed easily); 6=fluffy pieces with ragged edges, a mushy stool; 7=watery,

no solid pieces (entirely liquid).

290-μg group demonstrated statistically significant improvement c

Assessed using a 5-point ordinal scale: 1=not at all; 2=a little bit; 3=a moderate

compared with the placebo group, controlling for multiplicity. amount; 4=a great deal; 5=an extreme amount.

For the individual components of the FDA end point, a signifi- d

Assessed using a 5-point ordinal scale: 1=none; 2=mild; 3=moderate;

cantly greater percentage of linaclotide-treated patients, compared 4=severe; 5=very severe.

All demographic characteristics were similar between treatment groups. For

with placebo-treated patients, reported a reduction of ≥30% in baseline clinical characteristics, significant differences were observed for

abdominal pain for at least 6 out of the 12 weeks of the treatment abdominal fullness (P=0.011), stool consistency (P=0.046), and straining

(P=0.020).

period (50.1 vs. 37.5%, P = 0.0003 (Figure 2)) or an increase of

≥1 CSBM from baseline for at least 6 out of the 12 weeks of the

treatment period (48.6 vs. 29.6%, P < 0.0001 (Figure 2)). A total of

136 of 405 patients (33.6%) receiving linaclotide compared with

83 of 395 patients (21.0%) receiving placebo (odds ratio: 1.9, 95% which required improvement in abdominal pain (i.e., a reduction

confidence interval: 1.4, 2.7; P < 0.0001) met the FDA end point of ≥30% in abdominal pain), CSBM rate (i.e., ≥3 CSBMs and an

(Table 2; Figure 2). A significantly greater percentage of linaclo- increase of ≥1 CSBM), or both for at least 9 of the 12 weeks of the

tide-treated patients than placebo-treated patients also met the treatment period (Table 2). The NNT (number needed to treat) for

responder requirements for the other three primary end points, the primary end points ranged from 7.6 to 14.3.

The American Journal of GASTROENTEROLOGY VOLUME 107 | NOVEMBER 2012 www.amjgastro.com

Linaclotide in IBS-C 1719

Linaclotide-treated patients also experienced statistically sig- with placebo-treated patients (P < 0.001; Figure 3). At week 12, the

nificantly greater improvements compared with placebo-treated mean decrease from baseline in worst abdominal pain was 2.4%

patients for the secondary and additional end points (Table 3). for linaclotide vs. 1.5% for placebo (P < 0.0001), and the mean

FUNCTIONAL GI DISORDERS

During the first week of treatment and for each subsequent week of increase from baseline in the weekly CSBM rate was 2.4 and 0.9 for

treatment, linaclotide-treated patients reported greater improve- linaclotide and placebo, respectively (P < 0.0001). At the end of the

ments in worst abdominal pain and CSBM frequency compared Treatment Period (week 12), 52% of linaclotide-treated patients

80

≥ 30% Worst abdominal pain

reduction for ≥ 6/12 weeks

60 (secondary)

% Responders

50.1%***

40 37.5%

80

20 FDA end point (primary)

60

% Respoders

0

Placebo Lin 290 μg

40 33.6%****

NNT = 7.9

80 21.0%

Increase ≥1 CSBM from baseline 20

for ≥ 6/12 weeks (secondary)

60

% Responders

48.6%**** 0

Placebo Lin 290 μg

40 NNT= 7.9

29.6%

20

0

Placebo Lin 290 μg

NNT= 5.3

***P<0.001 ****P<0.0001

P values for all analyses based on a comparison of linaclotide versus placebo groups using the

Cochran-Mantel-Haenszel test

Figure 2. FDA end point and components. FDA end point: ≥30% abdominal pain reduction and increase ≥1 CSBM from baseline in the same week

for ≥6/12 weeks. ****P value < 0.0001, *** < 0.001 for linaclotide vs. placebo (Cochran–Mantel–Haenszel (CMH) test). P values met the criterion for

statistical significance based on the multiple-comparison procedure. CSBM, complete spontaneous bowel movement; FDA, Food and Drug Administration;

Lin, linaclotide; NNT, number needed to treat.

Table 2. Primary efficacy parameter results (ITT population)

Primary efficacy parameters Placebo Linaclotide

responder responder Odds ratio NNT

(N=395), n (%) (N=405), n (%) Difference (95% CI) P valuea (95% CI)

FDA end point (each week, ≥30% decrease in 83 (21.0) 136 (33.6) 12.6 1.9 (1.4, 2.7) < 0.0001 8.0 (5.4, 15.5)

worst abdominal pain + an increase ≥1 CSBM

from baseline for at least 6/12 weeks)

≥30% Decrease in worst abdominal pain (each 107 (27.1) 139 (34.3) 7.2 1.4 (1.0, 1.9) 0.0262 13.8 (7.4, 116.1)

week, ≥30% decrease in abdominal pain from

baseline for at least 9/12 weeks)

≥3 CSBMs and an increase of ≥1 CSBM (each 25 (6.3) 79 (19.5) 13.2 3.7 (2.3, 5.9) < 0.0001 7.6 (5.6, 11.6)

week, ≥3 CSBM + an increase ≥1 CSBM from

baseline for at least 9/12 weeks)

Combined responder (each week ≥30% decrease 20 (5.1) 49 (12.1) 7.0 2.6 (1.5, 4.5) 0.0004 14.2 (9.2, 31.3)

in worst abdominal pain + ≥3 CSBM + an increase

≥1 CSBM from baseline for at least 9/12 weeks)

CI, confidence interval; CSBM, complete spontaneous bowel movement; FDA, Food and Drug Administration; ITT, intent-to-treat; NNT, number needed to treat.

a

P values were based on a comparison of linaclotide vs. the placebo group using the Cochran–Mantel–Haenszel test.

© 2012 by the American College of Gastroenterology The American Journal of GASTROENTEROLOGY

1720 Rao et al.

Table 3. Other efficacy parameter results (ITT population)

Placebo, Linaclotide NNT

FUNCTIONAL GI DISORDERS

N =395 290 µg, N =405 Difference P value (95% CI)

Worst abdominal pain

Mean (11-point NRS scale) 4.4 3.7

a

Change from baseline, meanb,c − 1.1 − 1.9 − 0.7 < 0.0001

% of patients with ≥30% decrease in worst abdominal pain for at least

a

37.5 50.1 12.7 0.0003 7.9 (5.1, 17.1)

6/12 weeksd

Abdominal discomfort

Mean (11-point NRS scale) 4.7 4.1

a

Change from baseline, meanb,c − 1.2 − 2.0 − 0.7 < 0.0001

% of patients with ≥30% decrease in abdominal discomfort for at least 6/12 weeks d

37.0 48.1 11.2 0.0013 8.9 (5.6, 22.8)

Abdominal bloating

Mean (11-point NRS scale) 5.3 4.6

a b,c

Change from baseline, mean − 1.1 − 1.9 − 0.8 < 0.0001

% of patients with ≥30% decrease in abdominal bloating for at least 6/12 weeks d

29.9 43.5 13.6 < 0.0001 7.4 (5.0, 14.3)

Abdominal fullness

Mean (11-point NRS scale) 5.3 4.6

b,c

Change from baseline, mean − 1.1 − 2.0 − 0.9 < 0.0001

% of patients with ≥30% decrease in abdominal fullness for at least 32.9 44.0 11.0 0.0012 9.1 (5.6, 23.0)

6/12 weeksd

Abdominal cramping

Mean (11-point NRS scale) 4.1 3.5

b,c

Change from baseline, mean − 1.1 − 1.7 − 0.6 < 0.0001

% of patients with ≥30% decrease in abdominal cramping for at least 39.5 49.9 10.4 0.0029 9.6 (5.8, 28.3)

6/12 weeksd

CSBMs

Mean CSBMs/week 1.0 2.6

a

Change from baseline, meanb,c 0.7 2.3 1.6 < 0.0001

CSBM ≤24 h first dose (%)c 13.2 32.3 19.2 < 0.0001 5.2 (4.0, 7.4)

a

% of patients w/ CSBM rate increase ≥1 per week for at least 6/12 weeks d

29.6 48.6 19.0 < 0.0001 5.3 (3.9, 8.1)

SBMs

Mean SBMs/week 3.2 6.0

a b,c

Change from baseline 1.1 3.9 2.8 < 0.0001

SBM ≤24 h after first dose (%)c 43.8 67.4 23.6 < 0.0001 4.2 (3.3, 5.9)

% of patients w/ SBM rate increase ≥2 per week from baseline for at least 6/12 29.4 57.5 28.2 < 0.0001 3.6 (2.9, 4.6)

weeksd

Stool consistency

Mean BSFS score (1–7) 3.1 4.5

a

Change from baseline, meanb,c 0.7 2.1 1.4 < 0.0001

Mean weekly % of SBMs without hard or lumpy stools (BSFS ≥3) 60.7 79.4 18.7 < 0.0001

Straining

Mean straining score (1–5) 2.8 2.2

a b,c

Change from baseline, mean − 0.7 − 1.3 − 0.7 < 0.0001

Mean weekly % of SBMs without significant straining (i.e., score ≤3) 71.7 85.3 13.6 < 0.0001

Table continued on following page

The American Journal of GASTROENTEROLOGY VOLUME 107 | NOVEMBER 2012 www.amjgastro.com

Linaclotide in IBS-C 1721

Table 3. Continued

Placebo, Linaclotide NNT

FUNCTIONAL GI DISORDERS

N=395 290 µg, N=405 Difference P value (95% CI)

Constipation severity

Mean constipation severity score (1–5) 3.1 2.6

Change from baseline, meanb,c − 0.6 − 1.2 − 0.6 < 0.0001

% of patients with decrease of ≥1 for at least 6/12 weeks d

42.5 59.5 17.0 < 0.0001 5.9 (4.2, 9.9)

IBS severity

Mean IBS severity score (1–5) 3.1 2.7

b,c

Change from baseline, mean − 0.5 − 1.0 − 0.5 < 0.0001

% of patients with decrease of ≥1 for at least 6/12 weeks d

37.5 56.3 18.8 < 0.0001 5.3 (3.9, 8.3)

Adequate relief

% of patients reporting adequate relief of IBS symptoms for at least 75% of the 21.3 36.8 15.5 < 0.0001 6.4 (4.6, 10.7)

weeks (i.e., 9/12 weeks)d

% of patients reporting adequate relief of IBS symptoms for at least 50% of the 34.2 48.9 14.7 < 0.0001 6.8 (4.7, 12.6)

weeks (i.e., 6/12 weeks)d

Degree of relief e

% of patients reporting “Somewhat Relieved,” “Considerably Relieved,” or 24.3 41.2 16.9 < 0.0001 5.9 (4.3, 9.5)

“Completely Relieved” for 100% of the weekly scores or “Considerably

Relieved” or “Completely Relieved” for at least 50% of the weekly scoresd

BSFS, Bristol Stool Forms Scale; CI, confidence interval; CSBM, complete SBM; IBS, irritable bowel syndrome; ITT, intent-to-treat; NNT, number needed to treat; NRS,

numerical rating scale; SBM, spontaneous bowel movement.

a

Secondary end point.

b

Changes from baseline are the least-squares means from the analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) model.

c

P values were based on a comparison of linaclotide vs. the placebo group using the ANCOVA model.

d

P values were based on a comparison of linaclotide vs. the placebo group using the Cochran–Mantel–Haenszel test.

e

Degree of Relief scale: 1=completely relieved; 2=considerably relieved; 3=somewhat relieved; 4=unchanged; 5=somewhat worse; 6=considerably worse; 7=as bad as

I can imagine.

were either “very satisfied” or “quite satisfied” with treatment com- diarrhea (P < 0.0001), flatulence (P = 0.0084), and abdominal

pared with 23% of placebo-treated patients (P < 0.0001). pain (P = 0.0462) TEAEs were significantly greater in the lina-

During the 4-week RW Period, patients who were re-randomized clotide-treated patients compared with placebo-treated patients.

from linaclotide to placebo showed an increase in worst abdominal The most common TEAE in the 12-week treatment period was

pain and a decrease in CSBMs to levels similar to those observed diarrhea, experienced by 19.5% of linaclotide-treated patients

in the placebo group during the Treatment Period. The patients compared with 3.5% of placebo-treated patients. The occur-

who continued to take linaclotide showed sustained improvement rences of diarrhea were reported to be mild or moderate in 71

in worst abdominal pain and CSBMs similar to that previously of 79 linaclotide-treated patients (89.9%) and 13 of 14 placebo-

observed during the Treatment Period. These improvements were treated patients (92.9%) who experienced diarrhea. There were no

statistically significant compared to patients re-randomized to pla- SAEs of diarrhea reported during the trial. None of the patients

cebo for weeks 13–16 for CSBMs (P < 0.001) and weeks 14–16 for who reported diarrhea experienced clinically significant sequelae

worst abdominal pain (P < 0.05). Patients who switched from pla- (e.g., orthostatic hypotension or dehydration). More than half of

cebo to linaclotide showed levels of improvement similar to those linaclotide-treated patients who experienced diarrhea had onset

experienced by linaclotide-treated patients during the Treatment within the first 2 weeks of treatment. Diarrhea was the most com-

Period (Figure 3). mon AE resulting in treatment discontinuation in linaclotide-

treated patients (5.7 vs. 0.3% in placebo-treated patients); overall,

Safety AEs resulted in the premature discontinuation of 32 patients

A total of 228 of 406 linaclotide-treated patients (56.2%) reported (7.9%) and 11 patients (2.8%) taking linaclotide and placebo,

at least one treatment-emergent AE (TEAE) compared with 210 respectively, in the treatment period.

of 396 placebo-treated patients (53.0%) in the 12-week treat- Rates of serious AEs (SAEs) did not differ between linaclo-

ment period (Table 4). Most TEAEs were mild or moderate in tide and placebo groups (two patients in each group (0.5%)). In

severity (93.8%, linaclotide; 98.1%, placebo). The incidences of the linaclotide group, the SAEs consisted of one patient who

© 2012 by the American College of Gastroenterology The American Journal of GASTROENTEROLOGY

1722 Rao et al.

experienced asthma and a second patient who experienced peri- experienced chronic cholecystitis and a second patient who expe-

cardial effusion and pericarditis leading to withdrawal from the rienced duodenitis, gastroenteritis, hiatal hernia, esophagitis, renal

trial. In the placebo group, the SAEs consisted of one patient who cyst, and urinary tract infection. There were no deaths during the

FUNCTIONAL GI DISORDERS

treatment period; one screened patient died as a result of cardio-

a respiratory arrest and ventricular fibrillation due to a possible drug

3

Treatment Period* RW Period** overdose, but this patient died before randomization and did not

receive trial medication.

Change in CSBM

There were no clinically significant differences between the lina-

2

clotide and placebo groups in the incidence of abnormal labora-

Rate

tory parameters, vital signs, or electrocardiogram parameters.

1

Serum bicarbonate levels were below the lower limit of normal at

the end of treatment in seven patients receiving linaclotide com-

0

BL 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 pared with one patient receiving placebo. None of these patients

Weeks reported diarrhea as an AE or other AEs that were considered to

Treatment Period RW Treatment Sequence be related to low bicarbonate levels.

Placebo Placebo / Linaclotide 290 μg In the subset of patients who were assessed for linaclotide

Linaclotide 290 μg Linaclotide 290 μg / Linaclotide 290 μg exposure, no quantifiable plasma levels of linaclotide were

Linaclotide 290 μg / Placebo

detected following trial-medication dosing at the randomiza-

Least-squares mean change in CSBM rate ± standard error

*P< 0.0001 for linaclotide patients compared to placebo patients for each of

tion and week 4 trial visits. All patients tested (72 placebo and 64

the 12 Treatment Period weeks (ANCOVA) linaclotide) had levels lower than the limit of quantification for

**P < 0.001 for linaclotide-linaclotide patients compared to linaclotide-placebo

patients for RW Period weeks 13-16 (ANCOVA) linaclotide ( < 0.2 ng/ml) and its primary metabolite, MM-419447

( < 2.0 ng/ml).

b Treatment Period* RW Period**

0

Change in Worst

Abdominal Pain

–1 Table 4. Treatment-emergent adverse events (safety population)

Adverse event Placebo Linaclotide 290 µg

–2 (preferred term) (N=396), n (%) (N=406), n (%) P value

Patients with at 210 (53.0) 228 (56.2) 0.3949

–3 least 1 TEAE

BL 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16

Weeks Diarrhea 14 (3.5) 79 (19.5) < 0.0001

Treatment Period RW Treatment Sequence Abdominal pain 10 (2.5) 22 (5.4) 0.0462

Placebo Placebo / Linaclotide 290 µg Flatulence 6 (1.5) 20 (4.9) 0.0084

Linaclotide 290 μg Linaclotide 290 μg / Linaclotide 290 μg

Linaclotide 290 μg / Placebo Headache 14 (3.5) 20 (4.9) 0.3825

Least-squares mean change in worst abdominal pain ± standard error

Abdominal 3 (0.8) 9 (2.2) 0.1434

*P< 0.001 for linaclotide patients compared to placebo patients for each of

the 12 Treatment Period weeks (ANCOVA) distension

**P < 0.05 for linaclotide-linaclotide patients compared to linaclotide-placebo

patients for RW Period weeks 14, 15, and 16 (ANCOVA) Treatment-emergent adverse events (TEAEs) reported in ≥2% of linaclotide-

treated patients and at an incidence greater than reported in placebo-treated

patients during the treatment period.

c Treatment Perioed* RW Period**

P value was based on a Fisher’s exact test comparing linaclotide and placebo.

0

% Change in Worst

–10

Abdominal Pain

–20

–30

–40

Figure 3. Weekly results for complete spontaneous bowel movement

–50

(CSBM) frequency (a, *P < 0.0001 for linaclotide patients compared with

–60 placebo patients for each of the 12 Treatment-Period weeks, **P < 0.001

BL 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16

Weeks for linaclotide–linaclotide patients compared with linaclotide–placebo

patients for RW Period weeks 13–16); reduction in worst abdominal pain

Treatment Period RW Treatment Sequence

(b, *P < 0.001 for linaclotide patients compared with placebo patients for

Placebo Placebo / Linaclotide 290 μg

each of the 12 Treatment Period weeks, **P < 0.05 for linaclotide–linaclotide

Linaclotide 290 μg Linaclotide 290 μg / Linaclotide 290 μg patients compared with linaclotide–placebo patients for RW Period weeks

Linaclotide 290 μg / Placebo 14–16); and percent reduction in worst abdominal pain (c,*P < 0.001

Least-squares mean percent change in worst abdominal pain ± standard error for linaclotide patients compared with placebo patients for each of the

*P< 0.001 for linaclotide patients compared to placebo patients for each of 12 Treatment Period weeks, **P < 0.05 for linaclotide–linaclotide patients

the 12 Treatment Period weeks (ANCOVA)

**P < 0.05 for linaclotide-linaclotide patients compared to linaclotide-placebo compared with linaclotide–placebo patients for RW Period week 14).

patients for RW Period week 14 (ANCOVA) All P values were derived from an analysis of covariance model.

The American Journal of GASTROENTEROLOGY VOLUME 107 | NOVEMBER 2012 www.amjgastro.com

Linaclotide in IBS-C 1723

During the RW period, TEAEs occurred in 22.2% of linaclo- without signs of a “rebound” or worsening of symptoms relative

tide–linaclotide patients, 22.1% of linaclotide–placebo patients, to baseline.

and 30.6% of placebo–linaclotide patients. With the exceptions of In addition to abdominal pain, linaclotide improved several

FUNCTIONAL GI DISORDERS

diarrhea and abdominal pain, the incidence of TEAEs was similar other important abdominal symptoms that are frequently

across the three treatment sequences. The incidence of diarrhea reported by IBS-C patients, including abdominal bloating and

was 1.9, 0.6, and 11.7%, in linaclotide–linaclotide, linaclotide– abdominal discomfort, beginning during the first week of treat-

placebo, and placebo–linaclotide patients, respectively. The inci- ment and continuing throughout the 12-week treatment period.

dence of abdominal pain was 1.3% in the linaclotide–linaclotide Linaclotide also improved bowel function, including SBM and

patients and 2.4% in the placebo–linaclotide patients; there CSBM frequency, straining, stool consistency, and constipation

were no TEAEs of abdominal pain in the linaclotide–placebo severity. However, in contrast to the gradual improvement in

patients. There was no evidence of “rebound” (i.e., worsening abdominal symptoms, improvement in bowel function occurred

in IBS-C symptoms compared with the baseline period in the more rapidly. Most linaclotide-treated patients experienced an

linaclotide–placebo patients). No SAEs were reported during the SBM within 24 h of the first dose of linaclotide (67.4 vs. 43.8%

RW period. for placebo, P < 0.0001); maximal improvement in bowel func-

tion usually occurred within the first week. Thus, improvement

with linaclotide in abdominal (sensory) symptoms such as

DISCUSSION abdominal pain may be attributable to more than improvement

In this large phase 3 clinical trial, a greater percentage of IBS-C in bowel function alone. Preclinical data suggest that cGMP,

patients who were treated with linaclotide achieved statistically which is released intra- and extracellularly following GCC acti-

significant improvement in the key symptoms of IBS-C, including vation by linaclotide, can reduce the firing of pain-sensing vis-

abdominal pain and constipation, compared with placebo. Four ceral afferent fibers (13). Further studies are under way that may

primary outcomes measures were assessed, including the FDA provide a better understanding of the mechanisms by which

end point. This end point required that patients experience a ben- linaclotide exerts its beneficial effects directly on abdominal

efit of at least 30% when compared with baseline in abdominal sensory symptoms.

pain and an increase of ≥1 CSBM from baseline in the same week Diarrhea was the most common TEAE in linaclotide-treated

for at least 6 out of the 12 weeks of the treatment period. In spite patients and appears to be an extension of linaclotide’s pharmaco-

of the rigor of this end point, 33.6% of linaclotide-treated patients logical effects. Although diarrhea was reported in 19.5% of

were responders compared with 21.0% of placebo-treated patients linaclotide-treated patients, only 2% reported that they had

(P < 0.0001). Furthermore, statistically significant differences in severe diarrhea and only 5.7% discontinued the drug due to

responder rates were also demonstrated for the three other pri- diarrhea. The incidence of SAEs was similar between linaclotide-

mary end points, which required (i) a decrease in abdominal pain and placebo-treated patients (n = 2 patients in each group); diarrhea

of ≥30%, (ii) both an absolute value of ≥3 CSBMs and an increase was not reported as an SAE.

of ≥1 CSBM from baseline, and (iii) both abdominal pain and In conclusion, linaclotide significantly improved abdominal

CSBM criteria for at least 9 of the 12 weeks of the treatment and bowel symptoms in this phase 3 trial (12-week treatment

period. period + 4-week RW period).

Although IBS is a disorder with multiple symptoms, abdominal

pain is one of the cardinal manifestations and strongly correlates ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

with IBS severity (22) and utilization of healthcare resources (23). Annie Neild, PhD, of Ironwood Pharmaceuticals, provided editorial

Also, an improvement in abdominal pain of ≥30% has been shown assistance.

to be clinically important in IBS patients (23), and in patients

reporting pain relief in general (24). In this trial, more than half of CONFLICT OF INTEREST

linaclotide-treated patients reported an improvement in abdomi- Guarantor of the article: Jeffrey M. Johnston, MD.

nal pain of ≥30% for at least 6 out of 12 weeks compared with Specific author contributions: Wrote the initial draft of the manu-

37.5% of placebo-treated patients, for an NNT of 7.9. Improve- script, assisted in the interpretation of data, and provided critical

ment in abdominal pain began within the first week of therapy, revision: Satish Rao and Anthony J. Lembo; designed the trial:

and once reaching maximum at 6–8 weeks, was sustained through- Jeffrey M. Johnston, Bernard J. Lavins, Harvey A. Schneier, and

out the remainder of the treatment period. By the last week of the Steven J. Shiff; assisted in the interpretation of data and critical

treatment period (week 12), linaclotide-treated patients reported revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: Jeffrey

a mean improvement of 43.2% in abdominal pain compared with M. Johnston, Bernard J. Lavins, Caroline B. Kurtz, Mark G. Currie,

27.5% for placebo-treated patients. During the 4-week RW period, Harvey A. Schneier, and Steven J. Shiff; provided statistical design,

patients re-randomized to remain on linaclotide had continued analyses, and interpretation: James E. MacDougall, Xinwei D. Jia,

relief of abdominal pain, showing durability of response, while Kelvin Shi, and James Z. Shao; coordinated acquisition of data and

those re-randomized from linaclotide to placebo showed a gradual trial supervision: Paul Eng and Susan M. Fox.

worsening of abdominal pain symptoms to the level experienced Financial support: This trial was funded by Forest Research

by patients receiving placebo during the treatment period, but Institute and Ironwood Pharmaceuticals, Inc.

© 2012 by the American College of Gastroenterology The American Journal of GASTROENTEROLOGY

1724 Rao et al.

Potential competing interests: Jeffrey M. Johnston, Caroline B. results from LOGIC (Longitudinal Outcomes Study of Gastrointestinal

Symptoms in Canada), a naturalistic study. Clin Ther 2006;28:1726–35.

Kurtz, James E. MacDougall, James Z. Shao, Bernard J. Lavins, and

5. Cash B, Sullivan S, Barghout V. Total costs of IBS: employer and managed

Mark G. Currie are employees of Ironwood Pharmaceuticals and care perspective. Am J Manag Care 2005;11:S7–S16.

FUNCTIONAL GI DISORDERS

own stock/stock options in Ironwood Pharmaceuticals. Harvey A. 6. Mayer EA. Clinical practice: irritable bowel syndrome. N Engl J Med

2008;358:1692–9.

Schneier, Steven J. Shiff, Paul Eng, Susan M. Fox, Xinwei D. Jia, and

7. Hungin AP, Chang L, Locke GR et al. Irritable bowel syndrome in the

Kelvin Shi are employees of Forest Laboratories and own stock/stock United States: prevalence, symptom patterns and impact. Aliment

options in Forest Laboratories. Anthony J. Lembo and Satish Rao are Pharmacol Ther 2005;21:1365–75.

8. Hungin AP, Whorwell PJ, Tack J et al. The prevalence, patterns and impact

paid consultants to Ironwood Pharmaceuticals and Forest Research

of irritable bowel syndrome: an international survey of 40,000 subjects.

Institute. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2003;17:643–50.

9. Brandt LJ, Chey WD, Foxx-Orenstein AE et al. An evidence-based position

statement on the management of irritable bowel syndrome. Am J Gastro-

Study Highlights enterol 2009;104 (Suppl 1): S1–S35.

10. Hulisz D. The burden of illness of irritable bowel syndrome: current

challenges and hope for the future. J Manag Care Pharm 2004;10:299–309.

WHAT IS CURRENT KNOWLEDGE

11. Drossman DA, Chey WD, Johanson JF et al. Clinical trial: lubiprostone in

3The hallmark symptoms of irritable bowel syndrome with patients with constipation-associated irritable bowel syndrome—results

constipation (IBS-C) are abdominal pain and constipation- of two randomized, placebo-controlled studies. Aliment Pharmacol Ther

related complaints including hard stools, straining, and 2009;29:329–41.

a sense of incomplete evacuation. 12. Bryant AP, Busby RW, Bartolini WP et al. Linaclotide is a potent and

3There are few effective treatments for IBS-C. selective guanylate cyclase C agonist that elicits pharmacological effects

locally in the gastrointestinal tract. Life Sci 2010;8:19–20.

3Linaclotide is a minimally absorbed, 14-amino-acid peptide 13. Castro J, Martin C, Hughes PA et al. A novel role of cyclic GMP in colonic

guanylate cyclase-C agonist (GCCA). sensory neurotransmission in healthy and TNBS-treated mice. Gastro-

3In phase 2 clinical studies, linaclotide accelerated colonic enterology 2011;140:S–538.

14. Eutamene H, Bradesi S, Larauche M et al. Guanylate cyclase C-mediated

transit and improved abdominal pain and constipation antinociceptive effects of linaclotide in rodent models of visceral pain.

associated with IBS-C. Neurogastroenterol Motil 2010;22:312–22.

WHAT IS NEW HERE 15. Andresen V, Camilleri M, Busciglio IA et al. Effect of 5 days linaclotide

on transit and bowel function in females with constipation-predominant

3In this phase 3 trial, patients treated with linaclotide irritable bowel syndrome. Gastroenterology 2007;133:761–8.

experienced statistically significant improvements in 16. Johnston JM, Kurtz CB, Macdougall JE et al. Linaclotide improves

abdominal symptoms (including abdominal pain) and abdominal pain and bowel habits in a phase IIb study of patients with

bowel function (including increased frequency of bowel irritable bowel syndrome with constipation. Gastroenterology 2010;139:

movements). 1877–86.

3Linaclotide improved other important irritable bowel 17. Lembo AJ, Schneier HA, Shiff SJ et al. Two randomized trials of linaclotide

for chronic constipation. N Engl J Med 2011;365:527–36.

syndrome with constipation (IBS-C) symptoms including 18. Thompson WG, Longstreth GF, Drossman DA et al. Functional bowel

bloating, stool consistency, and straining. disorders and functional abdominal pain. Gut 1999;45 (Suppl 2): II43–7.

3Linaclotide led to a significantly greater proportion of 19. Lewis SJ, Heaton KW. Stool form scale as a useful guide to intestinal transit

time. Scand J Gastroenterol 1997;32:920–4.

patients reporting adequate relief of their IBS-C symptoms

20. Winawer S, Fletcher R, Rex D et al. Colorectal cancer screening and

than placebo.

surveillance: clinical guidelines and rationale-update based on new

3Patients who completed 12 weeks of linaclotide treatment evidence. Gastroenterology 2003;124:544–60.

and were then re-randomized to placebo experienced 21. Guidance for industry: irritable bowel syndrome – clinical evaluation of

a return of IBS-C symptoms, without experiencing drugs for treatment. Food and Drug Administration 2012; Available at: URL:

“rebound” symptoms (worsening of symptoms beyond http://www.fda.gov/downloads/Drugs/GuidanceComplianceRegulatory

baseline levels). Information/Guidances/UCM205269.pdf Accessed 4 June 2012.

22. Lembo A, Ameen VZ, Drossman DA. Irritable bowel syndrome: toward an

3The most common adverse event with linaclotide treatment understanding of severity. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2005;3:717–25.

was diarrhea. 23. Spiegel B, Bolus R, Harris LA et al. Measuring irritable bowel syndrome

patient-reported outcomes with an abdominal pain numeric rating scale.

Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2009;30:1159–70.

REFERENCES 24. Farrar JT, Young JP, LaMoreaux L et al. Clinical importance of changes

1. Longstreth GF, Thompson WG, Chey WD et al. Functional bowel in chronic pain intensity measured on an 11-point numerical pain rating

disorders. Gastroenterology 2006;130:1480–91. scale. Pain 2001;94:149–58.

2. Hellstrom PM, Saito YA, Bytzer P et al. Characteristics of acute pain

attacks in patients with irritable bowel syndrome meeting Rome III criteria.

Am J Gastroenterol 2011;106:1299–307. This work is licensed under the Creative Commons

3. Drossman DA, Camilleri M, Mayer EA et al. AGA technical review on

irritable bowel syndrome. Gastroenterology 2002;123:2108–31.

Attribution-NonCommercial-No Derivative Works 3.0

4. Paré P. Health-related quality of life, work productivity, and health care Unported License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creative-

resource utilization of subjects with irritable bowel syndrome: baseline commons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0/

The American Journal of GASTROENTEROLOGY VOLUME 107 | NOVEMBER 2012 www.amjgastro.com

You might also like

- Original PDF Willard and Spackmans Occupational Therapy 12th Edition PDFDocument41 pagesOriginal PDF Willard and Spackmans Occupational Therapy 12th Edition PDFtrenton.bill86998% (44)

- ACG Clinical Guideline Management of Irritable.11Document28 pagesACG Clinical Guideline Management of Irritable.11adri20121989No ratings yet

- Chronic Suppurative Otitis Media in AdultsDocument10 pagesChronic Suppurative Otitis Media in AdultsRstadam TagalogNo ratings yet

- 02 Current Strategies in Anesthesia and AnalgesiaDocument14 pages02 Current Strategies in Anesthesia and AnalgesiakenthepaNo ratings yet

- Induction AgentsDocument100 pagesInduction AgentsSulfikar TknNo ratings yet

- Medical Therapies For IBS - DDocument27 pagesMedical Therapies For IBS - DBryan TorresNo ratings yet

- 2022 - Lingyu - Acupuncture For The Treatment of Diarrhea-Predominant - EcaDocument11 pages2022 - Lingyu - Acupuncture For The Treatment of Diarrhea-Predominant - EcaesmargarNo ratings yet

- A Candidate Probiotic With Unfavourable Effects in Subjects With Irritable Bowel Syndrome: A Randomised Controlled TrialDocument7 pagesA Candidate Probiotic With Unfavourable Effects in Subjects With Irritable Bowel Syndrome: A Randomised Controlled Trialdolo2000No ratings yet

- Efficacy of Linaclotide For Patients With Chronic ConstipationDocument11 pagesEfficacy of Linaclotide For Patients With Chronic ConstipationKzerk100No ratings yet

- Low FODMAP Diet vs. mNICE Guidelines in IBSDocument9 pagesLow FODMAP Diet vs. mNICE Guidelines in IBSMohammedNo ratings yet

- Aliment Pharmacol Ther - 2011 - Schmulson - Review Article The Treatment of Functional Abdominal Bloating and DistensionDocument16 pagesAliment Pharmacol Ther - 2011 - Schmulson - Review Article The Treatment of Functional Abdominal Bloating and DistensionSara VelezNo ratings yet

- The Role of Drotaverine in IbsDocument5 pagesThe Role of Drotaverine in IbsAli Abd AlrezaqNo ratings yet

- Nej Mo A 1505180Document12 pagesNej Mo A 1505180Verina Kartika PutriNo ratings yet

- Madisch Treatment of Irritable Bowel Syndrome With Herbal PreparationsDocument9 pagesMadisch Treatment of Irritable Bowel Syndrome With Herbal Preparationsoliffasalma atthahirohNo ratings yet

- Tugas Akhir Jurnal QodrunnadaDocument34 pagesTugas Akhir Jurnal QodrunnadaAnonymous 2CvtIRVNo ratings yet

- Sii ArtículoDocument5 pagesSii ArtículoMonserrat Garduño FonsecaNo ratings yet

- Polyethylene Glycol 3350 in The Treatment of Chronic IdiopathicDocument8 pagesPolyethylene Glycol 3350 in The Treatment of Chronic IdiopathicJose SalazarNo ratings yet

- IBS DiareDocument12 pagesIBS Diarejokeshua34No ratings yet

- AlkalineDocument9 pagesAlkalineFemma ElizabethNo ratings yet

- Moayyedi P The Effect of Fiber Supplementation On IrritableDocument8 pagesMoayyedi P The Effect of Fiber Supplementation On Irritableoliffasalma atthahirohNo ratings yet

- Tratamiento Actualizado en Intestino IrritableDocument12 pagesTratamiento Actualizado en Intestino IrritableCarlos Eduardo PlascenciaNo ratings yet

- El Efecto Del Kiwi en La Función de La Salud IntestinalDocument11 pagesEl Efecto Del Kiwi en La Función de La Salud IntestinalCatiuscia BarrilliNo ratings yet

- Capello CDocument10 pagesCapello CSreeja CherukuruNo ratings yet

- Original Research Bacillus Coagulans Significantly Improved Abdominal Pain and Bloating in Patients With IBSDocument7 pagesOriginal Research Bacillus Coagulans Significantly Improved Abdominal Pain and Bloating in Patients With IBSKaren RevelesNo ratings yet

- Begtrup, LuiseDocument10 pagesBegtrup, LuiseSreeja CherukuruNo ratings yet

- Efficacy of Bio-Optimized Extracts of Turmeric and Essential Fennel Oil On The Quality of Life in Patients With Irritable Bowel SyndromeDocument7 pagesEfficacy of Bio-Optimized Extracts of Turmeric and Essential Fennel Oil On The Quality of Life in Patients With Irritable Bowel SyndromeNejc KovačNo ratings yet

- S510A Prevalence of Irritable Bowel Syndrome IBS .511Document2 pagesS510A Prevalence of Irritable Bowel Syndrome IBS .511Lauren FavelaNo ratings yet

- PIIS1542356522000349Document12 pagesPIIS1542356522000349AaNo ratings yet

- Dispepsia Manajemen Dan TatalaksanaDocument8 pagesDispepsia Manajemen Dan TatalaksanaNovita ApramadhaNo ratings yet

- Martoni C.J Et. Al.Document16 pagesMartoni C.J Et. Al.Sreeja CherukuruNo ratings yet

- RESEARCH - GERD-Q Score DLBS2411-hiresDocument8 pagesRESEARCH - GERD-Q Score DLBS2411-hiresNanangNo ratings yet

- SucralfatDocument6 pagesSucralfathasan andrianNo ratings yet

- Systematic Review: The Effects of Fibre in The Management of Chronic Idiopathic ConstipationDocument7 pagesSystematic Review: The Effects of Fibre in The Management of Chronic Idiopathic Constipationadinny julmizaNo ratings yet

- PIIS0016508522003900 AGA IBS Constipation2022Document19 pagesPIIS0016508522003900 AGA IBS Constipation2022GP RS EMCNo ratings yet

- Pi Is 0016508522003912Document15 pagesPi Is 0016508522003912kevincruz9618No ratings yet

- Efficacy of Buspirone, A Fundus-Relaxing Drug, in Patients With Functional DyspepsiaDocument7 pagesEfficacy of Buspirone, A Fundus-Relaxing Drug, in Patients With Functional DyspepsiaIndra AjaNo ratings yet

- Rao BaloneteDocument8 pagesRao BaloneteAna Clara VilasboasNo ratings yet

- WJG 18 2067Document9 pagesWJG 18 2067CarlaToneliNo ratings yet

- Nutrients 12 01410 v2Document11 pagesNutrients 12 01410 v2Dwi atikaNo ratings yet

- GavisconDocument8 pagesGavisconletisha mamaNo ratings yet

- Ref 9 - García AlmeidaDocument2 pagesRef 9 - García AlmeidajavierNo ratings yet

- 1471 230X 12 42Document12 pages1471 230X 12 42alfred1294No ratings yet

- Double Blind Study of Ispaghula in Irritable Bowel SyndromeDocument4 pagesDouble Blind Study of Ispaghula in Irritable Bowel SyndromeDeepa PansareNo ratings yet

- Functional Constipation in Children: Investigation and Management of Anorectal MotilityDocument4 pagesFunctional Constipation in Children: Investigation and Management of Anorectal MotilityWinny Herya UtamiNo ratings yet

- Cisapride Use in Pediatric Patients With Intestinal Failure and Its Impact On Progression of Enteral NutritionDocument6 pagesCisapride Use in Pediatric Patients With Intestinal Failure and Its Impact On Progression of Enteral Nutritionmango91286No ratings yet

- Functional Dyspepsia in ChildrenDocument13 pagesFunctional Dyspepsia in ChildrenTimothy Eduard A. SupitNo ratings yet

- Comparison of Octreotide and Hyoscine in Controlling Gastrointestinal Symptoms Due To Malignant Inoperable Bowel ObstructionDocument4 pagesComparison of Octreotide and Hyoscine in Controlling Gastrointestinal Symptoms Due To Malignant Inoperable Bowel ObstructionThiago GomesNo ratings yet

- Itopride and DyspepsiaDocument9 pagesItopride and DyspepsiaRachmat AnsyoriNo ratings yet

- SIBO EritromicinaDocument8 pagesSIBO EritromicinaKat HerreraNo ratings yet

- Drisko 2006Document10 pagesDrisko 2006Elton MatsushimaNo ratings yet

- E 948Document13 pagesE 948ps piasNo ratings yet

- 2021 Behavioral and Diet Therapies in Integrated Care For Patients With IBSDocument16 pages2021 Behavioral and Diet Therapies in Integrated Care For Patients With IBSanonNo ratings yet

- A Placebo-Controlled Trial of Itopride in Functional DyspepsiaDocument9 pagesA Placebo-Controlled Trial of Itopride in Functional DyspepsiaSerley WulandariNo ratings yet

- HHS Public Access: Author ManuscriptDocument20 pagesHHS Public Access: Author ManuscriptMarin GregurinčićNo ratings yet

- Optimum Dosage of Ispaghula Husk in Patients With Irritable Bowel Syndrome Correlation of Symptom Relief With Whole Gut Transit Time and Stool WeightDocument6 pagesOptimum Dosage of Ispaghula Husk in Patients With Irritable Bowel Syndrome Correlation of Symptom Relief With Whole Gut Transit Time and Stool WeightDeepa PansareNo ratings yet

- Nej Mo A 2206038Document12 pagesNej Mo A 2206038dravlamfNo ratings yet

- PROTBIOTICS-Effect On IBS Duolac Vitality Clinical Study 2014Document10 pagesPROTBIOTICS-Effect On IBS Duolac Vitality Clinical Study 2014raju1559405No ratings yet

- CreonDocument12 pagesCreonNikola StojsicNo ratings yet

- Evaluating The Quality of Life of Adult Patients oDocument1 pageEvaluating The Quality of Life of Adult Patients opspd anakNo ratings yet

- Eight Weeks of Esomeprazole Therapy Reduces Symptom Relapse, Compared With 4 Weeks, in Patients With Los Angeles Grade A or B Erosive EsophagitisDocument9 pagesEight Weeks of Esomeprazole Therapy Reduces Symptom Relapse, Compared With 4 Weeks, in Patients With Los Angeles Grade A or B Erosive EsophagitisBeau PhatruetaiNo ratings yet

- Topic 1 Bibliography: Harvard System Abstract of The Study: Justification For Citing The MaterialDocument6 pagesTopic 1 Bibliography: Harvard System Abstract of The Study: Justification For Citing The MaterialMercurial AssasinNo ratings yet

- Abdominal Massage May Decrease Gastric Residual Volumes and Abdominal Circumference in Critically Ill PatientsDocument2 pagesAbdominal Massage May Decrease Gastric Residual Volumes and Abdominal Circumference in Critically Ill PatientsDiah PermatasariNo ratings yet

- Halawi 2017Document10 pagesHalawi 2017Mirilláiny AnacletoNo ratings yet

- Complementary and Alternative Medical Lab Testing Part 5: GastrointestinalFrom EverandComplementary and Alternative Medical Lab Testing Part 5: GastrointestinalNo ratings yet

- Raval PDFDocument5 pagesRaval PDFdebby claudiNo ratings yet

- ArnoldDocument5 pagesArnolddebby claudiNo ratings yet

- Demir 2015Document2 pagesDemir 2015debby claudiNo ratings yet

- Liquid Versus Gel Handrub Formulation: A Prospective Intervention StudyDocument8 pagesLiquid Versus Gel Handrub Formulation: A Prospective Intervention Studydebby claudiNo ratings yet

- The Pain, Agitation, and Delirium Practice Guidelines For Adult Critically Ill Patients: A Post-Publication PerspectiveDocument9 pagesThe Pain, Agitation, and Delirium Practice Guidelines For Adult Critically Ill Patients: A Post-Publication Perspectivedebby claudiNo ratings yet

- Management of Pain in The Intensive Care UnitDocument6 pagesManagement of Pain in The Intensive Care Unitdebby claudiNo ratings yet

- Spinal Epidural Synovial Sarcoma A Case of Homogen PDFDocument5 pagesSpinal Epidural Synovial Sarcoma A Case of Homogen PDFdebby claudiNo ratings yet

- Bestsoap PDFDocument1 pageBestsoap PDFdebby claudiNo ratings yet

- Urn - Isbn - 978-952-61-1781-2Document92 pagesUrn - Isbn - 978-952-61-1781-2debby claudiNo ratings yet

- Common Sense Talk About Antibacterial ProductsDocument2 pagesCommon Sense Talk About Antibacterial Productsdebby claudiNo ratings yet

- Best SoapDocument8 pagesBest Soapdebby claudiNo ratings yet

- NIH Public Access: Etiology and Treatment of Hypogonadism in AdolescentsDocument22 pagesNIH Public Access: Etiology and Treatment of Hypogonadism in Adolescentsdebby claudiNo ratings yet

- 2014 Article 3830Document8 pages2014 Article 3830debby claudiNo ratings yet

- Coffee and Herbal Tea Consumption Is Associated With Lower Liver Stiffness in The General Population: The Rotterdam StudyDocument10 pagesCoffee and Herbal Tea Consumption Is Associated With Lower Liver Stiffness in The General Population: The Rotterdam Studydebby claudiNo ratings yet

- Ese 125 Dihydroxyvitamin D 3 Ante Rev.12.15 Low 1Document6 pagesEse 125 Dihydroxyvitamin D 3 Ante Rev.12.15 Low 1debby claudiNo ratings yet

- 4.original SharifahDocument9 pages4.original Sharifahdebby claudiNo ratings yet

- Jovin2017 PDFDocument12 pagesJovin2017 PDFdebby claudiNo ratings yet

- Nutrients: Vitamin D and Graves' Disease: A Meta-Analysis UpdateDocument15 pagesNutrients: Vitamin D and Graves' Disease: A Meta-Analysis Updatedebby claudiNo ratings yet

- NEL243403R03 Karasek Lewinski WRDocument6 pagesNEL243403R03 Karasek Lewinski WRdebby claudiNo ratings yet

- Vitamin D and Thyroid Diseases: Institute of Endocrinology, Prague, Czech RepublicDocument6 pagesVitamin D and Thyroid Diseases: Institute of Endocrinology, Prague, Czech Republicdebby claudiNo ratings yet

- 1 s2.0 S0002961011000638 Main PDFDocument7 pages1 s2.0 S0002961011000638 Main PDFdebby claudiNo ratings yet

- Musa Shirmohammadie, Alireza Ebrahim Soltani, Shahriar Arbabi, Karim NasseriDocument6 pagesMusa Shirmohammadie, Alireza Ebrahim Soltani, Shahriar Arbabi, Karim Nasseridebby claudiNo ratings yet

- 21 Employee Benefits Cas. 1250, Pens. Plan Guide (CCH) P 23935u Nancy Martin v. Blue Cross & Blue Shield of Virginia, Inc., 115 F.3d 1201, 4th Cir. (1997)Document15 pages21 Employee Benefits Cas. 1250, Pens. Plan Guide (CCH) P 23935u Nancy Martin v. Blue Cross & Blue Shield of Virginia, Inc., 115 F.3d 1201, 4th Cir. (1997)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Eric Berne Define Transactional Analysis AsDocument3 pagesEric Berne Define Transactional Analysis Aspragyanmishra19No ratings yet

- Osteo PetDocument14 pagesOsteo PetSana RashidNo ratings yet

- Article Wjpps 1435657336 PDFDocument6 pagesArticle Wjpps 1435657336 PDFTEJBIR SINGHNo ratings yet

- Differentiating Anxiety and Depression: A Test of The Cognitive Content-Specificity HypothesisDocument5 pagesDifferentiating Anxiety and Depression: A Test of The Cognitive Content-Specificity HypothesismiraNo ratings yet

- Root Causes of Behaviour DifferencesDocument5 pagesRoot Causes of Behaviour DifferencesarunaNo ratings yet

- DysfagiaDocument4 pagesDysfagiaVarvara MarkoulakiNo ratings yet

- Acls Course HandoutsDocument8 pagesAcls Course HandoutsRoxas CedrickNo ratings yet

- 5.infecciones Micóticas Del Sistema Nervioso CentralDocument13 pages5.infecciones Micóticas Del Sistema Nervioso CentralLiz NuñezNo ratings yet

- The Harmonic MindDocument3 pagesThe Harmonic MindfinmacmillanNo ratings yet

- Nursing Process: Nursing Diagnosis Expected Outcomes Implementation EvaluationDocument4 pagesNursing Process: Nursing Diagnosis Expected Outcomes Implementation EvaluationMohamed KhaledNo ratings yet

- Inventory List at in Emergei (Cy: PrsentDocument1 pageInventory List at in Emergei (Cy: PrsentVirginia BennettNo ratings yet

- What Happens When Your Career Becomes Your Whole IdentityDocument7 pagesWhat Happens When Your Career Becomes Your Whole IdentityvvvNo ratings yet

- Priming IV TubingDocument10 pagesPriming IV Tubinglainey101No ratings yet

- Breast Reconstruction With Microvascular MS-TRAM and DIEP FlapsDocument8 pagesBreast Reconstruction With Microvascular MS-TRAM and DIEP FlapsisabelNo ratings yet

- The FinerMinds Guide To An Inspired LifeDocument30 pagesThe FinerMinds Guide To An Inspired LifeSeye KuyinuNo ratings yet

- NCP PsychDocument2 pagesNCP PsychJray Inocencio50% (4)

- Azzi, R., Fix, D. S. R., Keller, F. S., & Rocha e Silva, M. I. (1964) - Exteroceptive Control of Response Under Delayed Reinforcement. Journal of The Experimental Analysis of Behavior, 7, 159-162.Document4 pagesAzzi, R., Fix, D. S. R., Keller, F. S., & Rocha e Silva, M. I. (1964) - Exteroceptive Control of Response Under Delayed Reinforcement. Journal of The Experimental Analysis of Behavior, 7, 159-162.Isaac CaballeroNo ratings yet

- Getting A Second OpinionDocument12 pagesGetting A Second OpinionwindsorstarNo ratings yet

- AnemiaDocument11 pagesAnemiadewiq_wahyuNo ratings yet

- Standard Guidebook 022010 WithhealthwayDocument77 pagesStandard Guidebook 022010 WithhealthwayMaria AgnostikaNo ratings yet

- Non Accidental Injury GuidelinesDocument60 pagesNon Accidental Injury GuidelinesShahidatul Nadia SulaimanNo ratings yet

- Dysphagia in CPDocument19 pagesDysphagia in CPMaria Alejandra RengifoNo ratings yet

- CBG Coverage CBG Coverage: Actrapid Sliding ScaleDocument10 pagesCBG Coverage CBG Coverage: Actrapid Sliding ScaleSerious LeoNo ratings yet

- Ama Deus ResearchDocument174 pagesAma Deus ResearchyahyiaNo ratings yet

- Nej M 200009073431001Document8 pagesNej M 200009073431001Asri Ani NurchasanahNo ratings yet