Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Oral Manifestations in Pulmonary Diseases - Too Often A Neglected Problem

Oral Manifestations in Pulmonary Diseases - Too Often A Neglected Problem

Uploaded by

Annastasia MiaCopyright:

Available Formats

You might also like

- Doctor On Call Preview-1Document58 pagesDoctor On Call Preview-1Fourth YearNo ratings yet

- A Systematic Approach To Xerostomia Diagnosis and ManagementDocument10 pagesA Systematic Approach To Xerostomia Diagnosis and ManagementLeHoaiNo ratings yet

- Penyakit Periodontal Yang Berhubungan Dengan Penyakit Saluran PernafasanDocument35 pagesPenyakit Periodontal Yang Berhubungan Dengan Penyakit Saluran PernafasanraniNo ratings yet

- RK PerioDocument17 pagesRK PerioraniNo ratings yet

- Mometasone Furoate Nasal Spray-Systemic ReviewDocument5 pagesMometasone Furoate Nasal Spray-Systemic ReviewRobin ScherbatskyNo ratings yet

- O C I C U: RAL Are in The Ntensive ARE NITDocument1 pageO C I C U: RAL Are in The Ntensive ARE NITeduardoNo ratings yet

- Oral Hygiene Am J Crit Care-2004Document2 pagesOral Hygiene Am J Crit Care-2004Anonymous Gw5KGlpl2cNo ratings yet

- Geriatric Oral Health and Pneumonia RiskDocument5 pagesGeriatric Oral Health and Pneumonia RisknjddNo ratings yet

- Research Title:: HalitosisDocument12 pagesResearch Title:: Halitosisعمار محمد عباسNo ratings yet

- Periodontology 2000 - 2023 - Herrera - Europe S Contribution To The Evaluation of The Use of Systemic Antimicrobials in TheDocument28 pagesPeriodontology 2000 - 2023 - Herrera - Europe S Contribution To The Evaluation of The Use of Systemic Antimicrobials in TheEngku Ahmad MuzhaffarNo ratings yet

- 3 Halitosis 2.3.1 Definiton: 2.3.2 EtiologyDocument5 pages3 Halitosis 2.3.1 Definiton: 2.3.2 EtiologyarinilhaqueNo ratings yet

- Oral Health in Asthmatic Patients: A Review: Clinical and Molecular AllergyDocument8 pagesOral Health in Asthmatic Patients: A Review: Clinical and Molecular AllergyJOSE VALDEMAR OJEDA ROJASNo ratings yet

- OutDocument15 pagesOutIulia IonelaNo ratings yet

- Hygiene Status and Organoleptic Score in Mouth Breathing ChildrenDocument5 pagesHygiene Status and Organoleptic Score in Mouth Breathing ChildrenPhuong ThaoNo ratings yet

- Jcad 13 6 48Document6 pagesJcad 13 6 48neetika guptaNo ratings yet

- Steroid Inhaler Therapy and Oral Manifestation Similar To Median Rhomboid GlossitisDocument3 pagesSteroid Inhaler Therapy and Oral Manifestation Similar To Median Rhomboid GlossitisRochmahAiNurNo ratings yet

- Oral Microbiology Periodontitis PDFDocument85 pagesOral Microbiology Periodontitis PDFSIDNEY SumnerNo ratings yet

- Interrelationship Between Periapical Lesion and Systemic Metabolic DisordersDocument28 pagesInterrelationship Between Periapical Lesion and Systemic Metabolic DisordersmeryemeNo ratings yet

- HALITOSISDocument6 pagesHALITOSISrashui100% (1)

- 261 773 1 PB PDFDocument8 pages261 773 1 PB PDFDr Monal YuwanatiNo ratings yet

- PODJ - Imraan and FarzeenDocument6 pagesPODJ - Imraan and Farzeendaniel_siitompulNo ratings yet

- Oral Manifestations in COVID-19 Patients Associated With Oral Hyg - Jurnal KesmasDocument7 pagesOral Manifestations in COVID-19 Patients Associated With Oral Hyg - Jurnal Kesmasivana fadhilahNo ratings yet

- Salud Periodontal y Sistémica I 2Document2 pagesSalud Periodontal y Sistémica I 2Esau JLNo ratings yet

- Manifiesto PeriodontalDocument8 pagesManifiesto PeriodontalPablo DonosoNo ratings yet

- Dental Management of COPD Patient: SS Rahman1, M Faruque2, MHA Khan3, SA Hossain4Document3 pagesDental Management of COPD Patient: SS Rahman1, M Faruque2, MHA Khan3, SA Hossain4Shirmayne TangNo ratings yet

- Chronic RhinosinusitisDocument8 pagesChronic RhinosinusitisYunardi Singgo100% (1)

- Lo 1 Pengaruh Penyakit Sistemik Terhadap Kesehatan Gigi Dan MulutDocument5 pagesLo 1 Pengaruh Penyakit Sistemik Terhadap Kesehatan Gigi Dan MulutTrie Andini ArianiNo ratings yet

- Topicaldrugtherapiesfor Chronicrhinosinusitis: Lauren J. Luk,, John M. DelgaudioDocument11 pagesTopicaldrugtherapiesfor Chronicrhinosinusitis: Lauren J. Luk,, John M. DelgaudiomilaNo ratings yet

- Managing Xerostomia and Salivary Gland Hypofunction PDFDocument7 pagesManaging Xerostomia and Salivary Gland Hypofunction PDFArief R HakimNo ratings yet

- Ebook - Antibiotics in Dental Practice How Justified Are WeDocument7 pagesEbook - Antibiotics in Dental Practice How Justified Are WeNguyễn Quang HuyNo ratings yet

- Treatment of Acute Otitis Externa With Ciprofloxacin Otic 0.2% Antibiotic Ear SolutionDocument12 pagesTreatment of Acute Otitis Externa With Ciprofloxacin Otic 0.2% Antibiotic Ear SolutionNana HeriyanaNo ratings yet

- Drug Treatment of Oral Sub Mucous Fibrosis - A Review PDFDocument3 pagesDrug Treatment of Oral Sub Mucous Fibrosis - A Review PDFAnamika AttrishiNo ratings yet

- Candida 2Document12 pagesCandida 2Mémoire StomatodynieNo ratings yet

- Jurding RhinosinusistisDocument26 pagesJurding RhinosinusistisIhdina Hanifa Hasanal IbrahimNo ratings yet

- Challenge in DiagnosisDocument6 pagesChallenge in Diagnosissgoeldoc_550661200No ratings yet

- Adherence To Supportive Periodontal TreatmentDocument10 pagesAdherence To Supportive Periodontal TreatmentFabian SanabriaNo ratings yet

- Jpaher 12Document5 pagesJpaher 12AbiNo ratings yet

- Instrumentation For The Treatment of Periodontal DiseaseDocument11 pagesInstrumentation For The Treatment of Periodontal DiseaseEga Tubagus Aprian100% (2)

- Plants: Effect of Propolis Paste and Mouthwash Formulation On Healing After Teeth Extraction in Periodontal DiseaseDocument12 pagesPlants: Effect of Propolis Paste and Mouthwash Formulation On Healing After Teeth Extraction in Periodontal DiseaseSalsabila Tri YunitaNo ratings yet

- Jurnal RhinosinusitisDocument26 pagesJurnal RhinosinusitisFarah F SifakNo ratings yet

- Hematological Pathology Between Diagnosis and Treatment in The Context of Oral Manifestations. Management of The Patient With Leukemia in The Dental Practice. ReviewDocument10 pagesHematological Pathology Between Diagnosis and Treatment in The Context of Oral Manifestations. Management of The Patient With Leukemia in The Dental Practice. ReviewoanaNo ratings yet

- Fungal Infections of Oral Cavity: Diagnosis, Management, and Association With COVID-19Document12 pagesFungal Infections of Oral Cavity: Diagnosis, Management, and Association With COVID-19Roxana Guerrero SoteloNo ratings yet

- 23.balsaraf Et - Al.pubDocument6 pages23.balsaraf Et - Al.pubKamado NezukoNo ratings yet

- Doença Periodontal e Saúde Sistêmica Uma Atualização para MédicosDocument8 pagesDoença Periodontal e Saúde Sistêmica Uma Atualização para Médicos8cv9jx4h8rNo ratings yet

- Jurnal PerodonsiaDocument7 pagesJurnal PerodonsiaLisa Noor SetyaningrumNo ratings yet

- OJDOH - Antimicrobial Resistance &stewardship ProgramDocument7 pagesOJDOH - Antimicrobial Resistance &stewardship Programshayma rafatNo ratings yet

- Current Treatment of Oral Candidiasis A Literature ReviewDocument8 pagesCurrent Treatment of Oral Candidiasis A Literature ReviewRonaldo PutraNo ratings yet

- Schizophrenia and Oral Health - A Literature ReviewDocument8 pagesSchizophrenia and Oral Health - A Literature ReviewJulia DharmawanNo ratings yet

- Hormonal Effect On The Periodontium A Brief ReviewDocument5 pagesHormonal Effect On The Periodontium A Brief ReviewShraddha AgarwalNo ratings yet

- Periodontal Disease and Its Prevention, by Traditional and New Avenues (Review)Document3 pagesPeriodontal Disease and Its Prevention, by Traditional and New Avenues (Review)Louis Hutahaean100% (1)

- The Associations Between Periodontitis and Respiratory DiseaseDocument6 pagesThe Associations Between Periodontitis and Respiratory DiseaseAquila FP SinagaNo ratings yet

- Indications, Efficacy, and Safety of Intranasal Corticosteriods in RhinosinusitisDocument4 pagesIndications, Efficacy, and Safety of Intranasal Corticosteriods in RhinosinusitisMilanisti22No ratings yet

- TOnsillitis in ChildrenDocument5 pagesTOnsillitis in ChildrenTibu DollNo ratings yet

- A Current Approach To Halitosis and Oral MalodorDocument9 pagesA Current Approach To Halitosis and Oral MalodorNadya PuspitaNo ratings yet

- Pedodontics Asthma Assignment 3Document5 pagesPedodontics Asthma Assignment 3islam samirNo ratings yet

- Diagnostic Issues of Allergic Pharingitis: Odessa National Medical University, Odessa, UkraineDocument5 pagesDiagnostic Issues of Allergic Pharingitis: Odessa National Medical University, Odessa, UkraineGaluh EkaNo ratings yet

- Case Report-Hypothyroidism, Adenoid Hypertrophy and GingivitisDocument7 pagesCase Report-Hypothyroidism, Adenoid Hypertrophy and GingivitisDeepak GawandeNo ratings yet

- Laryngopharyngeal and Gastroesophageal Reflux: A Comprehensive Guide to Diagnosis, Treatment, and Diet-Based ApproachesFrom EverandLaryngopharyngeal and Gastroesophageal Reflux: A Comprehensive Guide to Diagnosis, Treatment, and Diet-Based ApproachesCraig H. ZalvanNo ratings yet

- Diagnosis and Treatment of Chronic CoughFrom EverandDiagnosis and Treatment of Chronic CoughSang Heon ChoNo ratings yet

- Whooping Cough Unveiled: From Pathogenesis to Promising TherapiesFrom EverandWhooping Cough Unveiled: From Pathogenesis to Promising TherapiesNo ratings yet

- Co-Existence of Carcinoma Tongue With Pulmonary TuberculosisDocument2 pagesCo-Existence of Carcinoma Tongue With Pulmonary TuberculosisAnnastasia MiaNo ratings yet

- Curriculum Vitae: Personal InformationDocument3 pagesCurriculum Vitae: Personal InformationAnnastasia MiaNo ratings yet

- JadwalDocument1 pageJadwalAnnastasia MiaNo ratings yet

- Senin Selasa Rabu Kamis Jumat: Sabtu MingguDocument1 pageSenin Selasa Rabu Kamis Jumat: Sabtu MingguAnnastasia MiaNo ratings yet

- Final Nutrition in COPDDocument30 pagesFinal Nutrition in COPDAnimesh AryaNo ratings yet

- Giatric NurseDocument5 pagesGiatric NurseKim TanNo ratings yet

- Bronchiolitis in Infants and Children - Clinical Features and Diagnosis - UpToDateDocument32 pagesBronchiolitis in Infants and Children - Clinical Features and Diagnosis - UpToDatedaniso12No ratings yet

- NMPST Month, Day, YeanmppkrDocument5 pagesNMPST Month, Day, Yeanmppkrsylvania heniNo ratings yet

- Textbook Kendigs Disorders of The Respiratory Tract in Children 9Th Edition Robert W Wilmott Ebook All Chapter PDFDocument53 pagesTextbook Kendigs Disorders of The Respiratory Tract in Children 9Th Edition Robert W Wilmott Ebook All Chapter PDFjeanette.shumock768100% (14)

- Respi Update 2019 SpirometryDocument48 pagesRespi Update 2019 SpirometryJashveerBedi100% (1)

- ACCA Toolkit Abridged VersionDocument124 pagesACCA Toolkit Abridged VersionBianca BiaNo ratings yet

- St. Scholastica's Academy of Marikina: I THE Problem AND ITS BackgroundDocument9 pagesSt. Scholastica's Academy of Marikina: I THE Problem AND ITS BackgroundRaffy BayanNo ratings yet

- MAPEHDocument9 pagesMAPEHNoraNo ratings yet

- Project Biology 11Document15 pagesProject Biology 11ABHISHEK SinghNo ratings yet

- Lung Ultrasound As An Emergency Triage Tool in Patients Diagnosed With Covid-19Document5 pagesLung Ultrasound As An Emergency Triage Tool in Patients Diagnosed With Covid-19IJAR JOURNALNo ratings yet

- Health 6 - 3rd Quarter FinalDocument43 pagesHealth 6 - 3rd Quarter Finalmarvin reanzoNo ratings yet

- Spirometry InterpretationDocument4 pagesSpirometry InterpretationSSNo ratings yet

- Major Side Effects of Inhaled Glucocorticoids - UpToDateDocument37 pagesMajor Side Effects of Inhaled Glucocorticoids - UpToDateAmr MohamedNo ratings yet

- MSC Environmental Management Dissertation TopicsDocument7 pagesMSC Environmental Management Dissertation TopicsIWillPayYouToWriteMyPaperSingaporeNo ratings yet

- Pulmonary Rehabilitation - UpToDateDocument37 pagesPulmonary Rehabilitation - UpToDateAlejandro CadarsoNo ratings yet

- Dissertation On Bronchial AsthmaDocument7 pagesDissertation On Bronchial AsthmaInstantPaperWriterSpringfield100% (1)

- AsmaDocument16 pagesAsmaLuis EduardoNo ratings yet

- Acute Respiratory Distress in ChildrenDocument25 pagesAcute Respiratory Distress in Childrensai ram100% (1)

- Primary Care A Collaborative Practice 5th EditionDocument61 pagesPrimary Care A Collaborative Practice 5th Editionthelma.brown536100% (50)

- Case Study Copd P. CongestionDocument80 pagesCase Study Copd P. CongestionBryant Riego IIINo ratings yet

- Respiratory Part 2Document23 pagesRespiratory Part 2api-26938624No ratings yet

- Internalmedicine Sub AnsDocument90 pagesInternalmedicine Sub AnsSaneesh . SanthoshNo ratings yet

- PG UnaniDocument12 pagesPG UnaniTamil SelviNo ratings yet

- Pulmonary Rehab - ECarroll PDFDocument26 pagesPulmonary Rehab - ECarroll PDFSulabh ShresthaNo ratings yet

- 06 Offline Module CourseDocument15 pages06 Offline Module CourseDylan Angelo AndresNo ratings yet

- Unit 5 Hospital EquipmentDocument3 pagesUnit 5 Hospital EquipmentALIFIANo ratings yet

- 8th National Moot CourtDocument12 pages8th National Moot CourtYashasviniNo ratings yet

- Soap Note CoughDocument19 pagesSoap Note CoughlameckwesiNo ratings yet

Oral Manifestations in Pulmonary Diseases - Too Often A Neglected Problem

Oral Manifestations in Pulmonary Diseases - Too Often A Neglected Problem

Uploaded by

Annastasia MiaOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Oral Manifestations in Pulmonary Diseases - Too Often A Neglected Problem

Oral Manifestations in Pulmonary Diseases - Too Often A Neglected Problem

Uploaded by

Annastasia MiaCopyright:

Available Formats

Oral Pathology

ORAL MANIFESTATIONS IN PULMONARY DISEASES – TOO OFTEN A

NEGLECTED PROBLEM

Doina-Clementina COJOCARU1, Andrei GEORGESCU2, Robert D. NEGRU3

1

Lecturer, Ist Medical Department, Faculty of Medicine , “Gr. T. Popa” UMPh of Iaşi, Romania

2

Assist. Prof., Department of Odontology, Faculty of Dental Medicine, “Gr. T. Popa” UMPh of Iaşi, Romania

3

Assist. Prof., Ist Medical Department, Faculty of Medicine, “Gr. T. Popa” UMPh of Iaşi, Romania

Corresponding author: andgeorgescu@yahoo.com

Abstract action, fewer systemic adverse effects and faster

Careful examination of the oral cavity in respiratory

onset of action. Several drug categories are used:

medicine is often neglected, although it represents β2-agonists, corticosteroids, anti-cholinergic

sometimes a clue for clinical diagnosis and it is important agents and their combinations. The increased use

in completely addressing the patient. On the other hand, of inhaled drugs and the fact that a large ratio of

the dental practitioner who treats a patient with unusual

oral lesions should observe correct guidance and medical the inhaled substances remains in the oro–

advice. Oral manifestations are of polymorphic nature, pharyngeal region has raised attention to the oral

being associated with a variety of pulmonary diseases and consequences of this type of medication:

specific therapies. Respiratory obstructive diseases,

xerostomia, mucosal changes, ulcerations, dental

systemic diseases with pulmonary involvement, lung

cancer, cystic fibrosis or tuberculosis all have clinical and/ cavities, halitosis, taste disturbances,

or therapeutic involvement of the oral cavity, which oropharyngeal candidiasis, gingivitis,

underlines the necessity of regular dental services and periodontitis, and signs of gastro-esophageal

careful oral cavity exam, as well as an active collaboration

between dental practitioners and pulmonologists or

reflux [1].

somnologists, for patient’s ultimate benefit. It is now proven that prolonged use of

Keywords: oral cavity, pulmonary disease, diagnosis β2-mimetic agents is associated with an increased

rate of dental cavities [2], which can be explained

1. INTRODUCTION by the various actions of these agents: reduced

salivary production and secretion, alongwith

increased Lactobacillus sp. and Streptococcus mutans

Careful examination of the oral cavity in

populations in the oral cavity [2]. Also, β2-agonists

respiratory medicine is often neglected, although

favor relaxation of the smooth muscle of the lower

it represents sometimes a clue for clinical

esophageal sphincter, followed by gastro-

diagnosis and it is important in completely

esophageal reflux [3] and a lower pH in the mouth,

addressing the patient. On the other hand, the

a pH < 5.5 being correlated with enamel

dental practitioner who treats a patient with

demineralization. Inhaled drugs, especially dry-

unusual oral lesions should observe correct

powders, contain fermentable carbohydrates and

guidance and medical advice. The oral

sugar as carriers, further increasing the rate of

manifestations in this context are polymorphic,

tooth decay [4].

being associated with a variety of pulmonary

Inhaled corticosteroids (ICS) are widely used

diseases and specific therapies.

in asthma and COPD treatments, a significant

percent of the administered dose remaining in the

2. INHALED MEDICATION oro-pharyngeal region and being associated with

several topical effects: oral candidiasis, dysphonia,

Nowadays, inhaled medication represents the perioral dermatitis, pharyngitis, reflex cough,

mainstay of therapy in asthma and COPD, due to sensation of thirst, tongue hypertrophy [5].

its major advantages, including delivery of These local side effects are not as important as

pharmacological agents directly to the site of the systemic secondary effects, yet they can affect

International Journal of Medical Dentistry 117

Doina-Clementina COJOCARU, Andrei GEORGESCU, Robert D. NEGRU

patient’s compliance to treatment. Among ICS, Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease

beclomethasone dipropionate has a more (COPD). Smoking is one of the major risk factors

favorably profile, being inhaled as an inactive for both COPD and oral pathology as a

form, activated in the lung by esterases, with periodontal disease. Epidemiological studies are

little activation in the oropharynx, in contrast to suggesting an association between COPD and

fluticasone propionate and budesonide, which periodontal disease [9] but, most probably, the

are inhaled in the pharmacologically-active form common link between these two conditions is

and have an increased incidence of oral side exposure to tobacco smoke. Some studies are

effects. The “paradoxical” local inflammatory indicating that COPD is associated with marginal

effect associated with the use of an anti– bone loss [10]. Other common issues are thrush

inflammatory drug is caused by the various - the most frequent mucosa ailment, and

components of the inhaled substances: the worsening of the dental status: gingival bleeding

propellant, lubrication components, and lactose, and pocket depth, reduced teeth number or even

which can all be the cause of the direct toothlessness, increased incidence of dental

inflammatory reaction [5,6]. plaque [10-12]. Data are controversial due to the

Corticosteroids are weak acids with little effect different periodontal disease variables involved:

on oral pH, however patients undergoing pocket depth or attachment loss, while the

treatment with ICS experience overgrowth of endpoint used in the trials - tooth loss - is not due

Candida species at oropharyngeal level, often self- only to periodontal diseases, but can be the result

limiting, as due to the inhibition of the immune of dental cavities. Some authors suggest that

system. Clinical aspects of such lesions include chronic airways obstruction is not associated

whitish papulaes and plaques, inflamed or with significant increase in pocket depth or a

bleeding tissue under the lesions. Also, an decreasing number of the remaining teeth,

increased prevalence of gingivitis has been comparatively with smokers with normal

noticed [7,8]. spirometry, when adjusted to age [13]; on the

For pneumologists and dentists, monitoring, opposite side, Wang et al. [12] found out in COPD

early recognition, and appropriate management patients fewer remaining teeth compared to the

of these oral lesions are requested, in order to control group, even if one third of it was

improve the life quality of chronic respiratory represented by current or former smokers. In

patients, while the task of dentists is to carefully addition, these patients have a denture plaque

ask patients about their pulmonary conditions biofilm that acts like a reservoir of pathogens in

and treatment, paying increased attention to the the upper and lower airways, the lower respiratory

characteristic lesions in the mouth. Using a tract being colonized with aspirated pathogenic

spacer, decreasing frequency of administration, bacteria [14].

and properly rinsing the mouth are simple and As to malignancy, a cohort study evaluating

effective measures to prevent oral corticosteroid- the risk of cancer in first-time hospital-diagnosed

related pathology. COPD patients concluded that these patients are

exposed to a considerably increased risk of

3. PULMONARY OBSTRUCTIVE developing tobacco-related cancers, including

DISEASES cancers of the oral cavity, larynx, and tongue,

alongside lung cancer [15].

Asthma. The most frequent oral health

Pulmonary obstructive diseases represent the

conditions associated with asthma are dental

main spectrum of chronic respiratory maladies

cavities and erosions, periodontal disease and

in the modern world, due to increased exposure

oral candidiasis [16]. The salivary secretion is the

to risk factors, such as smoking, obesity, diabetes,

main protective factor involved in oral health. In

air pollutants, and other noxious environmental

asthmatic patients, the use of β2-agonists reduces

factors. Such diseases share an obstructive

the salivary secretion rates by 26 to 36%,

syndrome located in the inferior or upper

compared to non-asthmatics, affecting

airways, also impacting oral cavity health.

composition, and altering this important

118 Volume 5 • Issue 2 April / June 2015 •

ORAL MANIFESTATIONS IN PULMONARY DISEASES – TOO OFTEN A NEGLECTED PROBLEM

defensive barrier [2,17]. Furthermore, such upper airway obstruction by forward

patients, particularly those of pediatric age, displacement of the mandible, tongue and other

have a prominent oral breathing pattern, oro-pharyngeal structures, indirectly moving

contributing to gingivitis, due to dehydration of the suprahyoid and genioglossus muscles in

alveolar mucosa, alongwith various anterior direction [24-26]. This therapy is

immunological factors which increase gingival frequently associated with several oro-facial

inflammation. Several elements – e.g., excessive side effects, usually acceptable: teeth and jaw

thirst, the attempt to wash away the taste of tenderness, myofascial pain, gum irritation,

inhaled medication, to counterbalance the increased salivation or xerostomia. Nevertheless,

desiccating effect of mouth breathing, and the there are some reports of exaggerated gag reflex,

reduced salivary flow induced by β2-agonists - periodontal lesions or fractures of teeth or dental

are related with an excessive consumption of fillings, while long term use of these devices is

cariogenic drinks [18]. associated with temporo-mandibular joint

An interesting issue is the influence of oral disease and temporary bite change in the

pathogens over allergy, a prominent feature in morning after the removal of the device in

asthma. Several recent studies speculated that almost all patients [27]. Moreover, some authors

exposure to oral pathogens associated with report permanent occlusal alteration after long-

periodontal diseases, such as gingivitis or term treatments [28], evidencing the importance

periodontitis, might play a protective role of regular follow-up and dental examination of

against development of asthma and allergy, the patients using this type of devices.

although large prospective birth cohort studies

are still missing [19]. Previous results of the 4. SYSTEMIC DISEASES WITH ORAL

Third National Health Nutrition Examination AND PULMONARY INVOLVEMENT

Survey (NHANES) [20] highlighted the

importance of oral colonization with

Sarcoidosis is a systemic disease with

Porphyromonas gingivalis, reflected by the higher

granulomas in the lungs and adenopathies,

titers of Ig G antibodies against P. gingivalis,

affecting almost all organs. The oral cavity

associated with a lower prevalence of asthma.

lesions in sarcoidosis are localized swelling or

Card et al. [21] confirmed that allergen-induced

nodules, painless ulcerations of the gingiva,

hyperresponsiveness of the airways is

buccal and labial mucosa, palate, and gingival

significantly decreased when infection with P.

inflammation, hyperplasia or recession,

gingivalis is established after sensitization to

diagnosis being made through biopsy, that

allergen.

reveals non-caseating granulomas. Involvement

Obstructive sleep apnea syndrome (OSAS).

of the tongue is very rare, including swelling,

In patients with OSAS, oral inflammation could

enlargement and ulcerations, as well as of the

play an important pathogenic role, the

salivary gland, which leads to a tumor-like

inflammatory process of the pharynx, uvula,

appearance [29]. Parotid gland impairment

soft palate, and oral cavity being associated

appears in 6% of patients, especially in women,

with increased production of nitric oxide (NO);

the clinical picture including a painless tumor-

measurement of oral exhaled NO, as a marker

like appearance, sometimes with xerostomia. A

of airway inflammation, appears increased in

rare but very suggestive clinical presentation

OSAS, being related to hypoxemia severity and

associated with glandular involvement is the

obstructive episodes [22]. However, the highest

Heerfordt-Waldenström syndrome, which

levels of nitric oxide are found in asthma, even

includes systemic sarcoidosis, xerostomia,

if, in these patients, the NO sources are the

parotid gland swelling – usually bilateral -

bronchi and alveoli [23].

uveitis, and facial nerve palsy [30,31]. The jaw

Dental services are also very helpful in the

bone involvement affects equally the maxilla

therapeutic management of these patients,

and mandible, the symptoms being due to the

preparing and fitting oral devices for mandible

lytic character of the lesion: teeth loosening,

advancement (ODMA), aimed at relieving

International Journal of Medical Dentistry 119

Doina-Clementina COJOCARU, Andrei GEORGESCU, Robert D. NEGRU

radiating pain, nasal obstruction, mandible inflammation. Secondary oral tuberculosis

tumefaction or maxillary bone loss [29]. usually leads to the diagnosis of asymptomatic

Wegener granulomatosis, a necrotizing pulmonary tuberculosis. Therefore, all cases of

granulomatous vasculitis of the small-to- incidentally discovered oral tuberculosis, even

medium vessels, has a common oral involvement, in asymptomatic patients, should be submitted

expressed as ulcerations on oral mucosa or to investigations for identifying its primary site

palate, tooth mobility and loss. The [37-39].

pathognomonic finding is granular hyperplastic Cystic fibrosis is a genetic disorder caused

gingivitis or the so-called “strawberry by mutations in the gene for the cystic fibrosis

gingivitis”, with red interdental papillae transmembrane conductance regulator (CFTR)

covered with hyperplastic purple petechiae. protein, affecting mostly the respiratory tract,

This clinical sign is essential for an early with chronic cough and sputum, dyspnea,

suspicion of diagnosis, and oral biopsy is recurrent infections, and associated pancreatic

mandatory for preventing a serious multiorgan insufficiency and malnutrition [40]. Oral

involvement of the respiratory airways and manifestations of the disease are generated by

kidneys [7, 32-33]. the effects on the salivary glands, the sublingual

ones being the most affected, followed by

5. OTHER PULMONARY DISEASES submandibular glands, due to the presence - at

that level - of mucous acinar cells; parotid

glands are less affected because of their serous

Lung cancer causes more than 25% of the oral structure. The affected glands are enlarged and

metastases, the jawbones being more frequently can be easily palpated; disturbances in the

affected, compared to the soft tissue of the oral composition of saliva could lead to xerostomia

cavity. The mandible is the most exposed bone, and require artificial saliva to keep oral mucosa

more than 55% of the metastases being located moist. The calcium content, mean pH, and

here, while some studies report that oral buffering capacity of the saliva are elevated.

metastases could be the first manifestation of this Patients with cystic fibrosis can also present

type of cancer, announcing unfortunately an cheilosis from vitamin deficiency, tooth

advanced stage of neoplastic pulmonary disease discoloration, and hypoplastic defects of

[34]. When located in the soft tissue, the permanent dentition, the latter associated with

metastases appear as a submucosal mass, highly tetracycline use during the period of tooth

vascularized, frequently hemorrhagic, rarely formation; replacing tetracycline with other

ulcerated, or, more frequently, as a hyperplastic antibiotics was followed by a reduction of this

reactive lesion [35]. When the mandible is type of dental defects [41]. Data provided by

interested, insidious paresthesia of the lower lip various studies are conflicting, however, it

on the affected side, rapidly progressing local seems that the incidence of dental cavities in

swelling and pain appear, as tumor invades the pediatric patients with cystic fibrosis is lower

inferior alveolar nerve, bone, and soft tissue [36]. than in age-matched healthy control population,

Clinical profile of the patient with oral metastases although these patients display a higher

also includes male sex, and age > 50 years [34]. incidence of enamel defects. This could be

Pulmonary tuberculosis can lead to oral related to an increased calcium content,

lesions in both primary and secondary stages. buffering capacity of saliva, and prolonged

Mouth involvement in secondary tuberculosis treatment with antibiotics. Some of these

is usually a result of reactivation and patients may also suffer from chronic nose and

hematogenous spread from the primary sinuses obstruction, associated with oral

infection of the lung, the lesions being very breathing pattern and anterior open bite [40-42].

similar to those of a squamous cell carcinoma: The main findings in clinical exam of the oral

irregular ulcerations with peripheral thickening cavity and the different therapeutic options of

and dirty-appearing base, biopsy and culture various pulmonary diseases involving the mouth

being necessary to confirm the granulomatous are summarized in Table 1.

120 Volume 5 • Issue 2 April / June 2015 •

ORAL MANIFESTATIONS IN PULMONARY DISEASES – TOO OFTEN A NEGLECTED PROBLEM

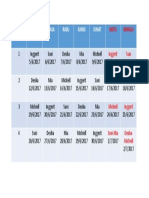

Table 1. Pulmonary conditions and the corresponding oral cavity involvement

Pulmonary conditions Oral cavity involvement

Deleterious effects on the quantity and quality of saliva,

Inhaled medication decreased oral pH (β2-agonists), candidiasis, dysphonia, tongue

hypertrophy (ICS), xerostomia

Chronic obstructive Periodontitis, thrush, worsening dental status, loss of alveolar

pulmonary disease bone, colonization of airways from denture plaque biofilm

Dental cavities and erosions, periodontal disease, candidiasis,

Asthma

colonization with P. gingivalis (lowers prevalence of asthma)

Obstructive sleep apnea Inflammation (pharynx, uvula, soft palate, oral cavity),

syndrome increased oral exhaled NO, therapy (ODMA)

Jaw metastases (mandible), submucosal mass or hyperplastic

Lung cancer

reactive lesion (soft tissue metastases)

“Strawberry gingivitis”, ulcerations (oral mucosa, palate), tooth

Wegener granulomatosis

mobility and loss

Sarcoidosis Painless ulcerations, gingivitis, localized swelling or nodules

Irregular ulcerations (secondary oral tuberculosis,

Pulmonary tuberculosis

hematogenous spread)

Xerostomia, tooth discoloration and hypoplastic defects

Cystic fibrosis (tetracycline), elevated calcium content, pH and buffering

capacity of saliva

6. CONCLUSIONS 2. Ryberg M, Moller C, Ericson T. Saliva composition

and caries development in asthmatic patients trea-

ted with beta-2 adrenoceptor agonists: a 4-year

Considering the comprehensive approach to follow-up study. Scand J Dent Res 1991; 99: 212-218.

chronic pulmonary patients, regular dental ser- 3. Al-Dlaigan YH, Shaw L, Smith AJ. Is there a relati-

vices and careful oral cavity exams are more onship between asthma and dental erosion? A case

than necessary for the management of these control study. Int J Paediatr Dent 2002; 12: 189-200.

4. Maguire A, Rugg-Gunn AJ, Butler TJ. Dental health

diseases, from diagnosis to therapeutic resour- of children taking antimicrobial and non-antimicro-

ces, favoring an early recognition, lowering the bial liquid oral medication long term. Caries Res

rate of infectious exacerbations, and increasing 1996; 30: 16-21.

life quality. An active collaboration among den- 5. Buhl R. Local oropharyngeal side effects of inhaled

tists and pulmonologists or somnologists, for corticosteroids in patients with asthma. Allergy

patient’s ultimate benefit, is absolutely 2006; 61: 518-526.

6. Kelly HW, Nelson HS. Potential adverse effects of

necessary.

the inhaled corticosteroids. J Allergy Clin Immunol

2003; 112: 469-478.

References 7. Casiglia JM, Elston DM. Oral manifestations of

systemic diseases. Medscape reference, http://eme-

1. Godara N, Godara R, Khullar M. Impact of inhala-

dicine.medscape.com/article/1081029-overview,

tion therapy on oral health. Lung India 2011; 28:

Accessed October 6, 2014.

272-275.

International Journal of Medical Dentistry 121

Doina-Clementina COJOCARU, Andrei GEORGESCU, Robert D. NEGRU

8. McDerra EJ, Bjerkeborn K, Dahllof G, Hedlin G, Lin- inflammation bt the oral pathogen Porphyromonas

dell M, Modeer T. Effect of disease severity and gingivalis. Infect Immunol 2010; 78(6): 2488-2496.

pharmacotherapy of asthma on oral health in asth- doi:10.1128/IAI.01270-09

matic children. Scand J Dent Res 1988; 22: 297-301. 22. Culla B, Guida G, Brussino L, Tribolo A, Cicolin A,

9. Katancik JA, Kritchevsky S, Weyant RJ, Corby P, Sciascia S, Badiu I, Mietta S, Bucca C. Increased oral

Bretz W, Crapo RO, Jensen R, Waterer G, Rubin SM, nitric oxide in obstructive sleep apnoea. Respir Med

Newman AB. Periodontitis and airway obstruction. 2010; 104: 316-320.

J Periodontol 2005; 76(11): 2161-2167. 23. Brindicci C, Ito K, Barnes PJ, Kharitonov SA. Diffe-

10. Leuckfeld I, Obregon-Whittle MV, Lund MB, Geiran rential flow analysis of exhaled nitric oxide in pati-

O, Bjørtuft Ø, Olsen I. Severe chronic obstructive ents with asthma of differing severity. Chest 2007;

pulmonary disease: association with marginal bone 131(5): 1353-1362.

loss in periodontitis. Respir Med 2008; 102: 488–494. 24. Hoekma A, Stegenga B, de Bont LGM. Efficacy and

11. Hyman JJ, Reid BC. Cigarette smoking, periodontal co-morbidity of oral appliances in the treatment of

disease: and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. obstructive sleep apnea-hypopnea: a systematic

J Periodontol 2004; 75: 9–15. review. Crit Rev Oral Biol Med 2004; 15(3): 137-155.

12. Wang Z, Zhou X, Zhang J, Zhang L, Song Y, Hu FB, 25. 25.Tegelberg A, Wilhelmsson B, Walker-Engstrom

Wang C. Periodontal health, oral health behaviours, ML, Ringqvist M, Andresson L, Krekmanov L et al.

and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. J Clin Effects and adverse events of a dental appliance for

Periodontol 2009; 36: 750–755. treatment of obstructive sleep apnoea. Swed Dent J

13. Bergstrom J, Cederlund K, Dahlen B, Lantz AS, Ske- 1999; 23: 117-126.

dinger M, Palmberg L, Sundblad BM, Larsson K. 26. Lozano AC, Perez GS, Esteve CG. Dental conside-

Dental health in smokers with and without COPD. rations in patients with respiratory problems. J Clin

PLoS ONE 2013; 8(3): e59492.doi:10.1371/journal. Exp Dent 2011; 3: 222-227.

pone.0059492. 27. Lindman R, Bondemark L. A review of oral devices

14. Przybylowska D, Mierzwińska-Nastalska E, Rubin- in the treatment of habitual snoring and obstructive

sztajn R, Chazan R, Rolski D, Swoboda-Kopeć E. sleep apnoea. Swed Dent J 2001; 25: 39-51.

Influence of denture plaque biofilm on oral mucosal 28. Rose EC, Schnegelsberg C, Staats R, Jonas IE. Occlu-

membrane in patients with chronic obstructive pul- sal side effects caused by a mandibular advance-

monary disease. Adv Exp Med Biol 2015; 839: 25-30. ment appliance in patients with obstructive sleep

15. Kornum JB, Svaerke C, Thomsen RW, Lange P, apnea. Angle Orthod 2001; 71: 452-460.

Sorensen HT. Chronic obstructive pulmonary 29. Suresh L, Radfar L. Oral sarcoidosis: a review of

disease and cancer risk: a Danish nationwide cohort literature. Oral Diseases 2005; 11: 138-145.

study. Respir Med 2012; 106: 845-852. 30. James DG, Sharma OP. Parotid gland sarcoidosis.

16. Thomas MS, Parolia A, Kundabala M, Vikram M. Sarcoidosis Vasc Diffuse Lung Dis 2000; 17: 27-32.

Astma and oral health: a review. Austral Dent J 31. Mandel L, Kaynar A. Sialadenopathy: a clinical

2010; 55: 128-133. doi: 10.1111/j.1834- herald of sarcoidosis. J Oral Maxillofac Surg 1994;

7819.2010.001226.x 52: 1208-1210.

17. Kuo LC, Polson AM, Kang T. Associations between 32. Ruokonen H, Helve T, Arola J, Hietanen J, Lindqvist

periodontal diseases and systemic diseases: a review C, Hagstrom J. “Strawberry like” gingivitis being

of the inter-relationships and interactions with dia- the first sign of Wegener’s granulomatosis. Eur J

betes, respiratory diseases, cardiovascular diseases Intern Med 2009; 20: 651-653.

and osteoporosis. Public Health 2008; 12: 417-433. 33. Aravena V, Beltran V, Cantin M, Fuentes R. Gingival

18. Stensson M, Wendt LK, Koch G, Oldaeus G, Birkhed hyperplasia being the first sign of Wegener’s granu-

D. Oral health in preschool children with asthma. lomatosis. Int J Clin Exp Med 2014; 7: 2373-2376.

Int J Paediatr Dent 2008; 18: 243-250. 34. Kaugars GE, Svirsky JA. Lung malignancies metas-

19. Arbes SJ, Matsui EC. Can oral pathogens influence tatic to the oral cavity. Or Surg Or Med Or Pa 1981;

allergic disease? J Allergy Clin Immunol 2011; 127: 51(2): 179-186.

1119-1127. 35. Maiorano E, Piatelli A, Favia G. Hepatocellular car-

20. Arbes SJ Jr, Sever ML, Vaughn B, Cohen EA, Zeldin cinoma metastatic to the oral mucosa: report of a

DC. Oral pathogens and allergic disease: results case with multiple gingival localizations. J Perio-

from the Third National Health and Nutrition Exa- dontal 2000; 71: 641-645.

mination Survey. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2006; 118: 36. Hirshberg A, Leibovitch P, Buchner A. Metastatic

1169-1175. tumours to the jaw bones: analysis of 390 cases. J

21. Card JW, Carey MA, Voltz JW, Bradbury A, Fergu- Oral Pathol 1994; 23: 337-341.

son CD, Cohen EA, Schwartz S, Flake GP, Morgan 37. Aoun N, El-Haji G, El Toum S. Oral ulcer: an uncom-

DL, Arbes SJ, Barrow DA, Barros SP, Offenbacher S, mon site in primary tuberculosis. Austral Dent J

Zeldin DC. Modulation of allergic airway 2015; 60(1): 119.

122 Volume 5 • Issue 2 April / June 2015 •

ORAL MANIFESTATIONS IN PULMONARY DISEASES – TOO OFTEN A NEGLECTED PROBLEM

38. Singhaniya SB, Barpande SR, Bhavthankar JD. Oral in children affected by cystic fibrosis in a southern

tuberculosis in an asymptomatic pulmonary tuber- Italian region. Eur J Ped Den 2009; 10(2): 65-68.

culosis. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol 41. Kinirons MJ. Increased salivary buffering in asso-

Endod 2011; 111(3): e8-e10. ciation with a low caries experience in children

39. Sezer B, Zeytinoglu M, Tuncay U, Unal T. Oral suffering from cystic fibrosis. J Dent Res 1983; 62:

mucosal ulceration: a manifestation of previously 815-817.

undiagnosed pulmonary tuberculosis. J Am Dent 42. Narang A, Maguire A, Nunn JH, Bush A. Oral

Assoc 2004; 135(4): 336-340. health and related factors in cystic fibrosis and

40. Ferrazzano GF, Orlando S, Sangianantoni G, Cantile other chronic respiratory disorders. Arch Dis Child

T, Ingenito A. Dental and periodontal health status 2003; 88: 702-707.

International Journal of Medical Dentistry 123

You might also like

- Doctor On Call Preview-1Document58 pagesDoctor On Call Preview-1Fourth YearNo ratings yet

- A Systematic Approach To Xerostomia Diagnosis and ManagementDocument10 pagesA Systematic Approach To Xerostomia Diagnosis and ManagementLeHoaiNo ratings yet

- Penyakit Periodontal Yang Berhubungan Dengan Penyakit Saluran PernafasanDocument35 pagesPenyakit Periodontal Yang Berhubungan Dengan Penyakit Saluran PernafasanraniNo ratings yet

- RK PerioDocument17 pagesRK PerioraniNo ratings yet

- Mometasone Furoate Nasal Spray-Systemic ReviewDocument5 pagesMometasone Furoate Nasal Spray-Systemic ReviewRobin ScherbatskyNo ratings yet

- O C I C U: RAL Are in The Ntensive ARE NITDocument1 pageO C I C U: RAL Are in The Ntensive ARE NITeduardoNo ratings yet

- Oral Hygiene Am J Crit Care-2004Document2 pagesOral Hygiene Am J Crit Care-2004Anonymous Gw5KGlpl2cNo ratings yet

- Geriatric Oral Health and Pneumonia RiskDocument5 pagesGeriatric Oral Health and Pneumonia RisknjddNo ratings yet

- Research Title:: HalitosisDocument12 pagesResearch Title:: Halitosisعمار محمد عباسNo ratings yet

- Periodontology 2000 - 2023 - Herrera - Europe S Contribution To The Evaluation of The Use of Systemic Antimicrobials in TheDocument28 pagesPeriodontology 2000 - 2023 - Herrera - Europe S Contribution To The Evaluation of The Use of Systemic Antimicrobials in TheEngku Ahmad MuzhaffarNo ratings yet

- 3 Halitosis 2.3.1 Definiton: 2.3.2 EtiologyDocument5 pages3 Halitosis 2.3.1 Definiton: 2.3.2 EtiologyarinilhaqueNo ratings yet

- Oral Health in Asthmatic Patients: A Review: Clinical and Molecular AllergyDocument8 pagesOral Health in Asthmatic Patients: A Review: Clinical and Molecular AllergyJOSE VALDEMAR OJEDA ROJASNo ratings yet

- OutDocument15 pagesOutIulia IonelaNo ratings yet

- Hygiene Status and Organoleptic Score in Mouth Breathing ChildrenDocument5 pagesHygiene Status and Organoleptic Score in Mouth Breathing ChildrenPhuong ThaoNo ratings yet

- Jcad 13 6 48Document6 pagesJcad 13 6 48neetika guptaNo ratings yet

- Steroid Inhaler Therapy and Oral Manifestation Similar To Median Rhomboid GlossitisDocument3 pagesSteroid Inhaler Therapy and Oral Manifestation Similar To Median Rhomboid GlossitisRochmahAiNurNo ratings yet

- Oral Microbiology Periodontitis PDFDocument85 pagesOral Microbiology Periodontitis PDFSIDNEY SumnerNo ratings yet

- Interrelationship Between Periapical Lesion and Systemic Metabolic DisordersDocument28 pagesInterrelationship Between Periapical Lesion and Systemic Metabolic DisordersmeryemeNo ratings yet

- HALITOSISDocument6 pagesHALITOSISrashui100% (1)

- 261 773 1 PB PDFDocument8 pages261 773 1 PB PDFDr Monal YuwanatiNo ratings yet

- PODJ - Imraan and FarzeenDocument6 pagesPODJ - Imraan and Farzeendaniel_siitompulNo ratings yet

- Oral Manifestations in COVID-19 Patients Associated With Oral Hyg - Jurnal KesmasDocument7 pagesOral Manifestations in COVID-19 Patients Associated With Oral Hyg - Jurnal Kesmasivana fadhilahNo ratings yet

- Salud Periodontal y Sistémica I 2Document2 pagesSalud Periodontal y Sistémica I 2Esau JLNo ratings yet

- Manifiesto PeriodontalDocument8 pagesManifiesto PeriodontalPablo DonosoNo ratings yet

- Dental Management of COPD Patient: SS Rahman1, M Faruque2, MHA Khan3, SA Hossain4Document3 pagesDental Management of COPD Patient: SS Rahman1, M Faruque2, MHA Khan3, SA Hossain4Shirmayne TangNo ratings yet

- Chronic RhinosinusitisDocument8 pagesChronic RhinosinusitisYunardi Singgo100% (1)

- Lo 1 Pengaruh Penyakit Sistemik Terhadap Kesehatan Gigi Dan MulutDocument5 pagesLo 1 Pengaruh Penyakit Sistemik Terhadap Kesehatan Gigi Dan MulutTrie Andini ArianiNo ratings yet

- Topicaldrugtherapiesfor Chronicrhinosinusitis: Lauren J. Luk,, John M. DelgaudioDocument11 pagesTopicaldrugtherapiesfor Chronicrhinosinusitis: Lauren J. Luk,, John M. DelgaudiomilaNo ratings yet

- Managing Xerostomia and Salivary Gland Hypofunction PDFDocument7 pagesManaging Xerostomia and Salivary Gland Hypofunction PDFArief R HakimNo ratings yet

- Ebook - Antibiotics in Dental Practice How Justified Are WeDocument7 pagesEbook - Antibiotics in Dental Practice How Justified Are WeNguyễn Quang HuyNo ratings yet

- Treatment of Acute Otitis Externa With Ciprofloxacin Otic 0.2% Antibiotic Ear SolutionDocument12 pagesTreatment of Acute Otitis Externa With Ciprofloxacin Otic 0.2% Antibiotic Ear SolutionNana HeriyanaNo ratings yet

- Drug Treatment of Oral Sub Mucous Fibrosis - A Review PDFDocument3 pagesDrug Treatment of Oral Sub Mucous Fibrosis - A Review PDFAnamika AttrishiNo ratings yet

- Candida 2Document12 pagesCandida 2Mémoire StomatodynieNo ratings yet

- Jurding RhinosinusistisDocument26 pagesJurding RhinosinusistisIhdina Hanifa Hasanal IbrahimNo ratings yet

- Challenge in DiagnosisDocument6 pagesChallenge in Diagnosissgoeldoc_550661200No ratings yet

- Adherence To Supportive Periodontal TreatmentDocument10 pagesAdherence To Supportive Periodontal TreatmentFabian SanabriaNo ratings yet

- Jpaher 12Document5 pagesJpaher 12AbiNo ratings yet

- Instrumentation For The Treatment of Periodontal DiseaseDocument11 pagesInstrumentation For The Treatment of Periodontal DiseaseEga Tubagus Aprian100% (2)

- Plants: Effect of Propolis Paste and Mouthwash Formulation On Healing After Teeth Extraction in Periodontal DiseaseDocument12 pagesPlants: Effect of Propolis Paste and Mouthwash Formulation On Healing After Teeth Extraction in Periodontal DiseaseSalsabila Tri YunitaNo ratings yet

- Jurnal RhinosinusitisDocument26 pagesJurnal RhinosinusitisFarah F SifakNo ratings yet

- Hematological Pathology Between Diagnosis and Treatment in The Context of Oral Manifestations. Management of The Patient With Leukemia in The Dental Practice. ReviewDocument10 pagesHematological Pathology Between Diagnosis and Treatment in The Context of Oral Manifestations. Management of The Patient With Leukemia in The Dental Practice. ReviewoanaNo ratings yet

- Fungal Infections of Oral Cavity: Diagnosis, Management, and Association With COVID-19Document12 pagesFungal Infections of Oral Cavity: Diagnosis, Management, and Association With COVID-19Roxana Guerrero SoteloNo ratings yet

- 23.balsaraf Et - Al.pubDocument6 pages23.balsaraf Et - Al.pubKamado NezukoNo ratings yet

- Doença Periodontal e Saúde Sistêmica Uma Atualização para MédicosDocument8 pagesDoença Periodontal e Saúde Sistêmica Uma Atualização para Médicos8cv9jx4h8rNo ratings yet

- Jurnal PerodonsiaDocument7 pagesJurnal PerodonsiaLisa Noor SetyaningrumNo ratings yet

- OJDOH - Antimicrobial Resistance &stewardship ProgramDocument7 pagesOJDOH - Antimicrobial Resistance &stewardship Programshayma rafatNo ratings yet

- Current Treatment of Oral Candidiasis A Literature ReviewDocument8 pagesCurrent Treatment of Oral Candidiasis A Literature ReviewRonaldo PutraNo ratings yet

- Schizophrenia and Oral Health - A Literature ReviewDocument8 pagesSchizophrenia and Oral Health - A Literature ReviewJulia DharmawanNo ratings yet

- Hormonal Effect On The Periodontium A Brief ReviewDocument5 pagesHormonal Effect On The Periodontium A Brief ReviewShraddha AgarwalNo ratings yet

- Periodontal Disease and Its Prevention, by Traditional and New Avenues (Review)Document3 pagesPeriodontal Disease and Its Prevention, by Traditional and New Avenues (Review)Louis Hutahaean100% (1)

- The Associations Between Periodontitis and Respiratory DiseaseDocument6 pagesThe Associations Between Periodontitis and Respiratory DiseaseAquila FP SinagaNo ratings yet

- Indications, Efficacy, and Safety of Intranasal Corticosteriods in RhinosinusitisDocument4 pagesIndications, Efficacy, and Safety of Intranasal Corticosteriods in RhinosinusitisMilanisti22No ratings yet

- TOnsillitis in ChildrenDocument5 pagesTOnsillitis in ChildrenTibu DollNo ratings yet

- A Current Approach To Halitosis and Oral MalodorDocument9 pagesA Current Approach To Halitosis and Oral MalodorNadya PuspitaNo ratings yet

- Pedodontics Asthma Assignment 3Document5 pagesPedodontics Asthma Assignment 3islam samirNo ratings yet

- Diagnostic Issues of Allergic Pharingitis: Odessa National Medical University, Odessa, UkraineDocument5 pagesDiagnostic Issues of Allergic Pharingitis: Odessa National Medical University, Odessa, UkraineGaluh EkaNo ratings yet

- Case Report-Hypothyroidism, Adenoid Hypertrophy and GingivitisDocument7 pagesCase Report-Hypothyroidism, Adenoid Hypertrophy and GingivitisDeepak GawandeNo ratings yet

- Laryngopharyngeal and Gastroesophageal Reflux: A Comprehensive Guide to Diagnosis, Treatment, and Diet-Based ApproachesFrom EverandLaryngopharyngeal and Gastroesophageal Reflux: A Comprehensive Guide to Diagnosis, Treatment, and Diet-Based ApproachesCraig H. ZalvanNo ratings yet

- Diagnosis and Treatment of Chronic CoughFrom EverandDiagnosis and Treatment of Chronic CoughSang Heon ChoNo ratings yet

- Whooping Cough Unveiled: From Pathogenesis to Promising TherapiesFrom EverandWhooping Cough Unveiled: From Pathogenesis to Promising TherapiesNo ratings yet

- Co-Existence of Carcinoma Tongue With Pulmonary TuberculosisDocument2 pagesCo-Existence of Carcinoma Tongue With Pulmonary TuberculosisAnnastasia MiaNo ratings yet

- Curriculum Vitae: Personal InformationDocument3 pagesCurriculum Vitae: Personal InformationAnnastasia MiaNo ratings yet

- JadwalDocument1 pageJadwalAnnastasia MiaNo ratings yet

- Senin Selasa Rabu Kamis Jumat: Sabtu MingguDocument1 pageSenin Selasa Rabu Kamis Jumat: Sabtu MingguAnnastasia MiaNo ratings yet

- Final Nutrition in COPDDocument30 pagesFinal Nutrition in COPDAnimesh AryaNo ratings yet

- Giatric NurseDocument5 pagesGiatric NurseKim TanNo ratings yet

- Bronchiolitis in Infants and Children - Clinical Features and Diagnosis - UpToDateDocument32 pagesBronchiolitis in Infants and Children - Clinical Features and Diagnosis - UpToDatedaniso12No ratings yet

- NMPST Month, Day, YeanmppkrDocument5 pagesNMPST Month, Day, Yeanmppkrsylvania heniNo ratings yet

- Textbook Kendigs Disorders of The Respiratory Tract in Children 9Th Edition Robert W Wilmott Ebook All Chapter PDFDocument53 pagesTextbook Kendigs Disorders of The Respiratory Tract in Children 9Th Edition Robert W Wilmott Ebook All Chapter PDFjeanette.shumock768100% (14)

- Respi Update 2019 SpirometryDocument48 pagesRespi Update 2019 SpirometryJashveerBedi100% (1)

- ACCA Toolkit Abridged VersionDocument124 pagesACCA Toolkit Abridged VersionBianca BiaNo ratings yet

- St. Scholastica's Academy of Marikina: I THE Problem AND ITS BackgroundDocument9 pagesSt. Scholastica's Academy of Marikina: I THE Problem AND ITS BackgroundRaffy BayanNo ratings yet

- MAPEHDocument9 pagesMAPEHNoraNo ratings yet

- Project Biology 11Document15 pagesProject Biology 11ABHISHEK SinghNo ratings yet

- Lung Ultrasound As An Emergency Triage Tool in Patients Diagnosed With Covid-19Document5 pagesLung Ultrasound As An Emergency Triage Tool in Patients Diagnosed With Covid-19IJAR JOURNALNo ratings yet

- Health 6 - 3rd Quarter FinalDocument43 pagesHealth 6 - 3rd Quarter Finalmarvin reanzoNo ratings yet

- Spirometry InterpretationDocument4 pagesSpirometry InterpretationSSNo ratings yet

- Major Side Effects of Inhaled Glucocorticoids - UpToDateDocument37 pagesMajor Side Effects of Inhaled Glucocorticoids - UpToDateAmr MohamedNo ratings yet

- MSC Environmental Management Dissertation TopicsDocument7 pagesMSC Environmental Management Dissertation TopicsIWillPayYouToWriteMyPaperSingaporeNo ratings yet

- Pulmonary Rehabilitation - UpToDateDocument37 pagesPulmonary Rehabilitation - UpToDateAlejandro CadarsoNo ratings yet

- Dissertation On Bronchial AsthmaDocument7 pagesDissertation On Bronchial AsthmaInstantPaperWriterSpringfield100% (1)

- AsmaDocument16 pagesAsmaLuis EduardoNo ratings yet

- Acute Respiratory Distress in ChildrenDocument25 pagesAcute Respiratory Distress in Childrensai ram100% (1)

- Primary Care A Collaborative Practice 5th EditionDocument61 pagesPrimary Care A Collaborative Practice 5th Editionthelma.brown536100% (50)

- Case Study Copd P. CongestionDocument80 pagesCase Study Copd P. CongestionBryant Riego IIINo ratings yet

- Respiratory Part 2Document23 pagesRespiratory Part 2api-26938624No ratings yet

- Internalmedicine Sub AnsDocument90 pagesInternalmedicine Sub AnsSaneesh . SanthoshNo ratings yet

- PG UnaniDocument12 pagesPG UnaniTamil SelviNo ratings yet

- Pulmonary Rehab - ECarroll PDFDocument26 pagesPulmonary Rehab - ECarroll PDFSulabh ShresthaNo ratings yet

- 06 Offline Module CourseDocument15 pages06 Offline Module CourseDylan Angelo AndresNo ratings yet

- Unit 5 Hospital EquipmentDocument3 pagesUnit 5 Hospital EquipmentALIFIANo ratings yet

- 8th National Moot CourtDocument12 pages8th National Moot CourtYashasviniNo ratings yet

- Soap Note CoughDocument19 pagesSoap Note CoughlameckwesiNo ratings yet