Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Does Anyone Speak Arabic?: by Franck Salameh

Does Anyone Speak Arabic?: by Franck Salameh

Uploaded by

ChristianOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Does Anyone Speak Arabic?: by Franck Salameh

Does Anyone Speak Arabic?: by Franck Salameh

Uploaded by

ChristianCopyright:

Available Formats

Does Anyone Speak Arabic?

by Franck Salameh

I

n August 2010, Associated Press staffer Zeina Karam wrote an article, picked

up by The Washington Post and other news outlets, that tackled a cultural, and

arguably political, issue that had been making headlines for quite some time in the

Middle East: the question of multilingualism and the decline of the Arabic language in

polyglot, multiethnic Middle Eastern societies.1 Lebanon was Karam’s case study: an

Eastern Mediterranean nation that had for the past century been the testing grounds for

iconoclastic ideas and libertine tendencies muzzled and curbed elsewhere in the Arab

world.2 However, by inquiring into what is ailing the Arabic language—the nimbus and

supreme symbol of “Arabness”—the author aimed straight at the heart of Arab nation-

alism and the strict, linguistic orthodoxy that it mandated, putting in question its most

basic tenet: Who is an Arab?

ian writer and the spiritual father of linguistic

ARABIC AND ARABISM Arab nationalism:

For most of the twentieth century, Arabs, Every person who speaks Arabic is an Arab.

Arab nationalists, and their Western devo- Every individual associated with an Arabic-

tees tended to substitute Arab for Middle speaker or with an Arabic-speaking people is

Eastern history, as if the narratives, storylines, an Arab. If he does not recognize [his

and paradigms of other groups mattered little Arabness] … we must look for the reasons

or were the byproduct of alien sources far re- that have made him take this stand … But

moved from the authentic, well-ordered, har- under no circumstances should we say: “As

long as he does not wish to be an Arab, and as

monious universe of the “Arab world.”3 As

long as he is disdainful of his Arabness, then

such, they held most Middle Easterners to be he is not an Arab.” He is an Arab regardless of

Arab even if only remotely associated with

the Arabs and even if alien to the experiences,

language, or cultural proclivities of Arabs. In

the words of Sati al-Husri (1880-1967), a Syr- 1 Zeina Karam, “Lebanon Tries to Retain Arabic in Polyglot

Culture,” The Washington Post, Aug. 16, 2010. For more on

Arabic language decline, see Mahmoud al-Batal, “Identity and

Language Tension in Lebanon: The Arabic of Local News at

LBCI,” in Aleya Rouchdy, ed., Language Contact and Lan-

guage Conflict in Arabic: Variations on a Sociolinguistic Theme

Franck Salameh is assistant professor of Near (London: Curzon Arabic Linguistics Series, 2002); Al-Ittijah

al-Mu’akis, Al-Jazeera TV (Doha), Aug. 1, 2000, Aug. 28,

Eastern studies at Boston College and author of 2001; Zeina Hashem Beck, “Is the Arabic Language ‘Perfect’ or

Language, Memory, and Identity in the Middle ‘Backwards’?” The Daily Star (Beirut), Jan. 7, 2005; Hashem

Saleh, “Tajrubat al-Ittihad al-‘Urubby… hal Tanjah ‘Arabiyan?”

East: The Case for Lebanon (Lexington Books, Asharq al-Awsat (London), June 21, 2005.

2010). He thanks research assistant Iulia 2 Fouad Ajami, “The Autumn of the Autocrats,” Foreign

Padeanu for her valuable contributions to this Affairs, May-June, 2005.

3 Elie Kedourie, “Not So Grand Illusions,” The New York

essay. Review of Books, Nov. 23, 1967.

Salameh: Arabic Language / 47

training in it. On the other hand, Arabic is also a

multitude of speech forms, contemptuously re-

ferred to as “dialects,” differing from each other

and from the standard language itself to the same

extent that French is different from other Ro-

mance languages and from Latin. Still, Husri’s

dictum, “You’re an Arab if I say so!” became an

article of faith for Arab nationalists. It also con-

densed the chilling finality with which its author

and his acolytes foisted their blanket Arab label

on the mosaic of peoples, ethnicities, and lan-

guages that had defined the Middle East for mil-

lennia prior to the advent of twentieth-century

Arab nationalism.5

But if Husri had been intimidating in his

A rigid and unforgiving under- advocacy for a forced Arabization, his disciple

standing of the role of Arabic as a Michel Aflaq (1910-89), founder of the Baath

means of developing Arab nation- Party, promoted outright violence and cruelty

alism appeared frequently in the against those users of the Arabic language

writings of Baath Party founder who refused to conform to his prescribed,

Michel Aflaq. He promoted violence overarching, Arab identity. Arab nationalists

against those users of the Arabic must be ruthless with those members of the na-

language who refused to conform to tion who have gone astray from Arabism, wrote

his prescribed, overarching, Arab Aflaq,

identity: “hatred unto death, toward

any individuals who embody an idea they must be imbued with a hatred unto death,

contrary to Arab nationalism.” toward any individuals who embody an idea

contrary to Arab nationalism. Arab national-

ists must never dismiss opponents of

Arabism as mere individuals … An idea that

his own wishes, whether ignorant, indiffer- is opposed to ours does not emerge out of

ent, recalcitrant, or disloyal; he is an Arab, nothing! It is the incarnation of individuals

but an Arab without consciousness or feel- who must be exterminated, so that their idea

ings, and perhaps even without conscience.4 might in turn be also exterminated. Indeed,

the presence in our midst of a living oppo-

This ominous admonition to embrace a nent of the Arab national idea vivifies it and

domineering Arabism is one constructed on an stirs the blood within us. And any action we

assumed linguistic unity of the Arab peoples; a might take [against those who have rejected

unity that a priori presumes the Arabic language Arabism] that does not arouse in us living

itself to be a unified, coherent verbal medium, emotions, that does not make us feel the orgas-

used by all members of Husri’s proposed na- mic shudders of love, that does not spark in us

quivers of hate, and that does not send the

tion. Yet Arabic is not a single, uniform language.

blood coursing in our veins and make our pulse

It is, on the one hand, a codified, written stan-

beat faster is, ultimately, a sterile action.6

dard that is never spoken natively and that is

accessible only to those who have had rigorous

5 Franck Salameh, Language Memory and Identity in the

Middle East: The Case for Lebanon (Lanham, Md.: Lexington

4 Abu Khaldun Sati Al-Husri, Abhath Mukhtara fi-l-Qawmiyya Books, 2010), pp. 9-10.

al-‘Arabiya (Beirut: Markaz Dirasat al-Wihda al-‘Arabiya, 1985), 6 Michel Aflaq, Fi Sabil al-Ba’ath (Beirut: Dar at-Tali’a,

p. 80. 1959), pp. 40-1.

48 / MIDDLE EAST QUARTERLY FALL 2011

Therein lay the foundational tenets of Arab ethnic and linguistic heritage.

nationalism and the Arabist narrative of Middle Cultural anthropologist Selim Abou argued

Eastern history as preached by Husri, Aflaq, and that notwithstanding Lebanon’s millenarian his-

their cohorts: hostility, rejection, negation, and tory and the various and often contradictory

brazen calls for the annihilation of the non-Arab interpretations of that history, the country’s en-

“other.” Yet despite the dominance of such dis- dogenous and congenital multilingualism—and

turbing Arabist and Arab nationalist readings, by extension that of the

the Middle East in both its modern and ancient entire Levantine littoral

incarnations remains a patchwork of varied cul- —remains indisputable. Modern Standard

tures, ethnicities, and languages that cannot be He wrote:

tailored into a pure and neat Arab essence with- Arabic is codified

out distorting and misinforming. Other models From the very early and written

of Middle Eastern identities exist, and a spir- dawn of history up to

but never

ited Middle Eastern, intellectual tradition that the conquests of Alex-

ander the Great, and spoken natively.

challenges the monistic orthodoxies of Arab na-

from the times of Alex-

tionalism endures and deserves recognition and

ander until the dawning

validation. of the first Arab Empire, and finally, from the

coming of the Arabs up until modern times,

the territory we now call Lebanon—and this

THE ARABIC is based on the current state of archaeologi-

LANGUAGE DEBATE cal and historical discoveries—has always

practiced some form of bilingualism and

Take for instance one of the AP article’s polyglossia; one of the finest incarnations of

intercultural dialogue and coexistence.7

interviewees who lamented the waning of the

Arabic language in Lebanese society and the rise

So much, then, for linguistic chauvinism

in the numbers of Francophone and Anglophone

and language protectionism. The Arabic lan-

Lebanese, suggesting “the absence of a com-

guage will survive the onslaught of multilingual-

mon language between individuals of the same

ism but only if its users will it to survive by

country mean[s] losing [one’s] common iden-

speaking it rather than by hallowing it and by

tity”—as if places like Switzerland and India, each

refraining from creating conservation societies

with respectively four and twenty-three official,

that build hedges around it to shield it from des-

national—often mutually incomprehensible—

uetude. Even avid practitioners of multilingual-

speech forms, were lesser countries or suffered

ism in Lebanon, who were never necessarily tal-

more acute identity crises than ostensibly cohe-

ented or devoted Arabophones, have tradition-

sive, monolingual societies. In fact, the opposite

ally been supportive of the idea of preserving

is often true: Monolingualism is no more a pre-

Arabic in the roster of Lebanese languages—

condition or motivation for cultural and ethnic

albeit not guarding and fixing it by way of mum-

cohesiveness than multilingualism constitutes

mification, cultural dirigisme, or rigid linguistic

grounds for national incoherence and loss of a

planning. Though opposed in principle to Arab

common identity. Irishmen, Scotsmen, Welsh,

nationalism’s calls for the insulation of linguis-

and Jamaicans are all native English-speakers

tically libertine Lebanon “in the solitude of a

but not Englishmen. The AP could have ac-

troubled and spiteful nationalism … [and] lin-

knowledged that glaring reality, which has been

guistic totalitarianism,” Lebanese thinker Michel

a hallmark of the polyglot multiethnic Middle

Chiha (1891-1954) still maintained that:

East for millennia. This, of course, is beside the

fact that for many Lebanese—albeit mainly

Christians—multilingualism and the appeal of

Western languages is simply a way of heeding 7 Selim Abou, Le bilinguisme Arabe-Français au Liban (Paris:

Presses Universitaires de France, 1962), pp. 157-8.

history and adhering to the country’s hybrid

Salameh: Arabic Language / 49

Arabic is a wonderful language … the lan- million native Arabophones—or even of a pal-

guage of millions of men. We wouldn’t be try one million such Arabic speakers—without

who we are today if we, the Lebanese of the oversimplifying and perverting an infinitely com-

twentieth century, were to forgo the pros- plex linguistic situation. The languages or dia-

pect of becoming [Arabic’s] most accom-

lects often perfunctorily labeled Arabic might

plished masters to the same extent that we

indeed not be Arabic at all.

had been its masters

some one hundred This is hardly a modern aberration devised

Languages or years ago … But how by modern reformists fancying dissociation from

can one not heed the the exclusivity of modern Arabism and its mono-

dialects often

reality that a country lithic paradigm. Even Ibn Khaldun (1332-1406),

perfunctorily such as ours would be the fourteenth-century Muslim jurist and

labeled Arabic literally decapitated if polymath and arguably the father of modern so-

might not be prevented from being ciology, wrote in his famous 1377 Prolegomena

bilingual (or even trilin- that only the language of Quraish—the Prophet

Arabic at all. gual if possible)? … [We Muhammad’s tribe—should be deemed true Ara-

must] retain this lesson

bic; that native Arabs learn this speech form natu-

if we are intent on pro-

rally and spontaneously; and that this language

tecting ourselves from self-inflicted deafness,

which would in turn lead us into mutism.8 became corrupt and ceased being Arabic when it

came into contact with non-Arabs and assimi-

Another fallacy reiterated in the AP article lated their linguistic habits. Therefore, he argued,

was the claim that “Arabic is believed to be spo-

the language of Quraish is the soundest and

ken as a first language by more than 280 million

purest Arabic precisely due to its remoteness

people.”9 Even if relying solely on the field of

from the lands of non-Arabs—Persians,

Arabic linguistics—which seldom bothers with Byzantines, and Abyssinians … whose lan-

the trivialities of precise cognomens denoting guages are used as examples by Arab philolo-

varieties of language, preferring instead the gists to demonstrate the dialects’ distance

overarching and reductive lahja (dialect/accent) from, and perversion of, Arabic.10

and fusha (Modern Standard Arabic, MSA) di-

chotomy to, say, the French classifications of Thackston has identified five dialectal clus-

langue, langage, parler, dialecte, langue ters that he classified as follows: “(1) Greater

vérnaculaire, créole, argot, patois, etc.—Zeina Syria, including Lebanon and Palestine; (2)

Karam’s arithmetic still remains in the sphere of Mesopotamia, including the Euphrates region

folklore and fairy tale, not concrete, objective of Syria, Iraq, and the Persian Gulf; (3) the Ara-

fact. Indeed, no serious linguist can claim the bian Peninsula, including most of what is Saudi

existence of a real community of “280 million Arabia and much of Jordan; (4) the Nile Valley,

people” who speak Arabic at any level of native including Egypt and the Sudan; and (5) North

proficiency, let alone a community that can speak Africa and [parts of] the … regions of sub-Sa-

Arabic “as a first language.” haran Africa.”11 He acknowledged that although

Harvard linguist Wheeler Thackston—and these five major dialectal regions were speckled

before him Taha Hussein, Ahmad Lutfi al- with linguistic varieties and differences in ac-

Sayyed, Abdelaziz Fehmi Pasha, and many oth- cent and sub-dialects, “there is almost complete

ers—have shown that the Middle East’s mutual comprehension [within each of them]—

demotic languages are not Arabic at all, and

consequently, that one can hardly speak of 280

10 Ibn Khaldun, al-Muqaddimah (Beirut: Dar al-Qalam, 1977),

p. 461.

8 Michel Chiha, Visage et Présence du Liban (Beirut: Editions 11 Wheeler M. Thackston, Jr., The Vernacular Arabic of the

du Trident, 1984), p. 49-52, 164. Lebanon (Cambridge, Mass.: Dept. of Near Eastern Languages

9 Karam, “Lebanon Tries to Retain Arabic.” and Civilizations, Harvard University, 2003), p. vii.

50 / MIDDLE EAST QUARTERLY FALL 2011

that is, a Jerusalemite,

a Beiruti, and an

Aleppan may not

speak in exactly the

same manner, but each

understands practi-

cally everything the

others say.” However,

he wrote,

When one crosses

one or more major

boundaries, as is

the case with a

Baghdadi and a

Damascene for in-

stance, one begins

to encounter diffi-

culty in compre-

hension; and the For some Arabs, like these Beirutis enjoying a night out on the town,

farther one goes, the multilingualism and the appeal of Western languages is a natural

less one under- corollary to their country’s hybrid ethnic and linguistic heritage. The

stands until mutual territory now known as Lebanon has historically practiced some form

comprehension dis-

of polyglossia and was once a shining representative of intercultural

appears entirely. To

coexistence in the Middle East.

take an extreme ex-

ample, a Moroccan

and an Iraqi can no

more understand each other’s dialects than Even Taha Hussein (1889-1973), the doyen

can a Portuguese and Rumanian.12 of modern Arabic belles lettres, had come to this

very same conclusion by 1938. In his The Fu-

In 1929, Tawfiq Awan had already begun ture of Culture in Egypt,14 he made a sharp dis-

making similar arguments, maintaining that the tinction between what he viewed to be Arabic

demotics of the Middle East—albeit arguably tout court—that is, the classical and modern

related to Arabic—were languages in their own standard form of the language—and the sun-

right, not mere dialects of Arabic: dry, spoken vernaculars in use in his contempo-

rary native Egypt and elsewhere in the Near East.

Egypt has an Egyptian language; Lebanon has

a Lebanese language; the Hijaz has a Hijazi For Egyptians, Arabic is virtually a foreign lan-

language; and so forth—and all of these lan- guage, wrote Hussein:

guages are by no means Arabic languages. Each

of our countries has a language, which is its Nobody speaks it at home, [in] school, [on]

own possession: So why do we not write the streets, or in clubs; it is not even used in

[our language] as we converse in it? For, the [the] Al-Azhar [Islamic University] itself.

language in which the people speak is the People everywhere speak a language that is

language in which they also write.13 definitely not Arabic, despite the partial re-

semblance to it.15

12 Ibid.

13 Israel Gershoni and James Jankowski, Egypt, Islam, and the 14 Taha Hussein, The Future of Culture in Egypt (Washing-

Arabs: The Search for Egyptian Nationalism, 1900-1930 (New ton, D.C.: American Council of Learned Societies, 1954).

York: Oxford University Press, 1986), p. 220. 15 Ibid., pp. 86-7.

Salameh: Arabic Language / 51

To this, Thackston has recently added that when cliché that the decline of Arabic—like the failure

Arabs speak of a bona fide Arabic language, of Arab nationalism—was the outcome of West-

they always mean ern linguistic intrusions and the insidious,

colonialist impulses of globalization. “Many

Classical [or Modern Standard] Arabic: the Lebanese pride themselves on being fluent in

language used for all written and official com- French—a legacy of French colonial rule,” Karam

munication; a language that was codified, stan- wrote, rendering a mere quarter-century of

dardized, and normalized well over a thou-

French mandatory presence in Lebanon (1920-

sand years ago and that has almost a millen-

46) into a period of classical-style “French colo-

nium and a half of uninterrupted literary legacy

behind it. There is only one problem with nial rule” that had allegedly destroyed the foun-

[this] Arabic: No one speaks it. What Arabs dations of the Arabic language in the country

speak is called Arabi Darij (“vernacular Ara- and turned the Lebanese subalterns into imita-

bic”), lugha ammiyye (“the vulgar language”), tive Francophones denuded of their putative

or lahje (“dialect”); only what they write do Arab personality.18

they refer to as “true [Arabic] language.”16 Alas, this fashionable fad fails to take into

account that French colonialism in its Lebanese

And so, even if context differed markedly from France’s colonial

Modern Standard Ara- experience elsewhere. For one, the founding fa-

Middle Easterners bic were taken to be the thers of modern Lebanon lobbied vigorously for

are steering clear Arabic that the AP was turning their post-Ottoman mountain Sanjak into

of Arabic in speaking of, it is still pa- a French protectorate after World War I.19 And

tently false to say, as with regard to the Lebanese allegedly privileg-

alarming numbers does Karam, that MSA is ing the French language, that too, according to

but not due to anybody’s “first,” native Selim Abou, seems to have hardly been a

Western influence. “spoken language”—let colonialist throwback and an outcome of early

alone the “spoken … first twentieth-century French imperialism. In his 1962

language [of] more than Le binlinguisme Arabe-Français au Liban,

280 million people.” Even Edward Said, a notori- Abou wrote that the French language (or early

ously supple and sympathetic critic when it comes Latin variants of what later became French) en-

to things Arab, deemed Arabic, that is MSA, the tered Mount-Lebanon and the Eastern Mediter-

“equivalent of Latin, a dead and forbidding lan- ranean littoral at the time of the first Crusades

guage” that, to his knowledge, nobody spoke (ca. 1099).20 Centuries later, the establishment

besides “a Palestinian political scientist and poli- of the Maronite College in Rome (1584) and the

tician whom [Said’s] children used to describe as liberal (pro-Christian) policies of then Mount-

‘the man who spoke like a book.’”17 Lebanon’s Druze ruler, Fakhreddine II (1572-

1635), allowed the Maronites to further

strengthen their religious and their religion’s an-

FOREIGN IMPOSITION cillary cultural and linguistic ties to Rome, Eu-

OR SELF AFFLICTION? rope, and especially France—then, still the “el-

der daughter” of the Catholic Church. This un-

Playing into the hands of keepers of leashed a wave of missionary work to Lebanon—

the Arab nationalist canon—as well as Arabists and wherever Eastern Christianity dared flaunt

and lobbyists working on behalf of the Arabic its specificity—and eventually led to the found-

language today—the AP article adopted the

18 Karam, “Lebanon Tries to Retain Arabic.”

16 Thackston, The Vernacular Arabic of the Lebanon, p. vii. 19 See, for instance, Meir Zamir, The Formation of Modern

17 Edward Said, “Living in Arabic,” al-Ahram Weekly (Cairo), Lebanon (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1988).

Feb. 12 - 18, 2004. 20 Abou, Le bilinguisme Arabe-Français au Liban, pp. 177-9.

52 / MIDDLE EAST QUARTERLY FALL 2011

ing of schools tending to the educational needs Yet, irreverent as they had been in shun-

of the Christian—namely Maronite—communi- ning Arabic linguistic autocracy and foster-

ties of the region. Although foundational courses ing a lively debate on MSA and multilingual-

in Arabic and Syriac were generally taught at those ism, Lebanon and Egypt and their Arabic tra-

missionary schools, European languages includ- vails are hardly uncom-

ing French, Italian, and German were also part of mon in today’s Middle

the regular curriculum. French, therefore, can be East. From Israel to Qatar

argued to have had an older pedigree in Lebanon and from Abu Dhabi to

A Druze poet and

than suggested by Karam. And contrary to the Kuwait, modern Middle academic called

classical norms in the expansion and transmis- Eastern nations that on Israel to do

sion of imperial languages—the spread of Arabic make use of some form away with the

included—which often entailed conquests, mas- of Arabic have had to

sacres, and cultural suppression campaigns, the come face to face with

public school

French language can be said to have been adopted the challenges hurled at system’s

willingly by the Lebanese through “seduction” their hermetic MSA and Arabic curricula.

not “subjection.”21 are impelled to respond

It is true that many Lebanese, and Middle to the onslaught of im-

Easterners more generally, are today steering pending polyglotism and linguistic humanism

clear of Arabic in alarming numbers, but con- borne by the lures of globalization.

trary to AP’s claim, this routing of Arabic is not In a recent article published in Israel’s lib-

mainly due to Western influence and cultural eral daily Ha’aretz, acclaimed Druze poet and

encroachments—though the West could share academic Salman Masalha called on Israel’s Edu-

some of the blame; rather, it can be attributed, cation Ministry to do away with the country’s

even if only partially, to MSA’s retrogression, public school system’s Arabic curricula and de-

difficulty, and most importantly perhaps, to the manded its replacement with Hebrew and En-

fact that this form of Arabic is largely a learned, glish course modules. Arabophone Israelis

cultic, ceremonial, and literary language, which taught Arabic at school, like Arabophones

is never acquired natively, never spoken na- throughout the Middle East, were actually taught

tively, and which seems locked in an uphill a foreign tongue misleadingly termed Arabic,

struggle for relevance against sundry sponta- wrote Masalha:

neous, dynamic, natively-spoken, vernacular

languages. Taha Hussein ascribed the decay The mother tongue [that people] speak at

and abnegation of the Arabic language prima- home is totally different from the … Arabic

rily to its “inability of expressing the depths of [they learn] at school; [a situation] that per-

petuates linguistic superficiality [and] leads

one’s feelings in this new age.” He wrote in

to intellectual superficiality … It’s not by

1956 that MSA is

chance that not one Arab university is [ranked]

among the world’s best 500 universities. This

difficult and grim, and the pupil who goes to

finding has nothing to do with Zionism.23

school in order to study Arabic acquires only

revulsion for his teacher and for the language,

Masalha’s is not a lone voice. The abstruse-

and employs his time in pursuit of any other

occupations that would divert and soothe his

ness of Arabic and the stunted achievements of

thoughts away from this arduous effort … those monolingual Arabophones constrained to

Pupils hate nothing more than they hate acquire modern knowledge by way of Modern

studying Arabic.22 Standard Arabic have been indicted in the United

Nations’ Arab Human Development reports—a

21 Ibid., pp. 191-5.

22 Taha Hussein, “Yasiru an-Nahw wa-l-Kitaba,” al-Adab 23 Salman Masalha, “Arabs, Speak Hebrew!” Ha’aretz (Tel

(Beirut), 1956, no. 11, pp. 2, 3, 6. Aviv), Sept. 27, 2010.

Salameh: Arabic Language / 53

series of reports written by Arabs and for the of translation. Yet, from all source-languages

benefit of Arabs—since the year 2002. To wit, combined, the Arab world’s 330 million people

the 2003 report noted that the Arabic language translated a meager 330 books per year; that is,

is struggling to meet the challenges of modern “one fifth of the number [of books] translated in

times Greece [home to 12 million Greeks].” Indeed, from

the times of the Caliph al-Ma’mun (ca. 800 CE) to

[and] is facing [a] severe … and real crisis in the beginnings of the twenty-first century, the

theorization, grammar, vocabulary, usage, “Arab world” had translated a paltry 10,000

documentation, creativity, and criticism … books: the equivalent of what Spain translates

The most apparent aspect of this crisis is the

in a single year.25

growing neglect of the functional aspects of

But clearer heads are prevailing in Arab

[Arabic] language use. Arabic language skills

in everyday life have deteriorated, and Arabic countries today. Indeed, some Arabs are taking

… has in effect ceased to be a spoken lan- ownership of their linguistic dilemmas; feckless

guage. It is only the language of reading and Arab nationalist vainglory is giving way to prac-

writing; the formal language of intellectuals tical responsible pursuits, and the benefits of

and academics, often used to display knowl- valorizing local speech forms and integrating for-

edge in lectures … [It] is not the language of eign languages into national, intellectual, and

cordial, spontaneous expression, emotions, pedagogic debates are being contemplated. Ar-

daily encounters, and ordinary communica- abs “are learning less Islam and more English in

tion. It is not a vehicle for discovering one’s the tiny desert sheikhdom of Qatar” read a 2003

inner self or outer surroundings.24

Washington Post article, and this overhaul of

Qatar’s educational system, with its integration

And so, concluded the report, the only

of English as a language of instruction—“a to-

Arabophone countries that were able to circum-

tal earthquake” as one observer termed it—was

vent this crisis of knowledge were those like

being billed as the Persian Gulf’s gateway to-

Lebanon and Egypt, which had actively pro-

ward greater participation in an ever more com-

moted a polyglot tradition, deliberately protected

petitive global marketplace. But many Qataris

the teaching of foreign

and Persian Gulf Arabs hint to more pressing

languages, and instated

and more substantive impulses behind curricu-

The Arabs’ failure math and science cur-

lar bilingualism: “necessity-driven” catalysts

ricula in languages other

to modernize may than Arabic.

aimed at replacing linguistic and religious jingo-

be a corollary ism with equality, tolerance, and coexistence;

Translation is an-

changing mentalities as well as switching lan-

of their language’s other crucial means of

guages and textbooks.26

inability to transmitting and acquir-

This revolution is no less subversive in

ing knowledge claimed

conform to the the U.N. report, and

nearby Abu Dhabi where in 2009 the Ministry

exigencies of of Education launched a series of pedagogical

given that “English rep-

reform programs aimed at integrating bilingual

modern life. resents around 85 per-

education into the national curriculum. Today,

cent of the total world

“some 38,000 students in 171 schools in Abu

knowledge balance,”

Dhabi [are] taught … simultaneously in Arabic

one might guess that “knowledge-hungry coun-

and English.”27

tries,” the Arab states included, would take heed

And so, rather than rushing to prop up and

of the sway of English, or at the very least, would

protect the fossilized remains of MSA, the de-

seek out the English language as a major source

25 Ibid., pp. 66-7.

24 Arab Human Development Report 2003 (New York: United 26 The Washington Post, Feb. 2, 2003.

Nations Development Programme, 2003), p. 54. 27 The National (Abu Dhabi), Sept. 15, 2010.

54 / MIDDLE EAST QUARTERLY FALL 2011

bate that should be engaged in today’s Middle

East needs to focus more candidly on the utility,

functionality, and practicality of a hallowed and

ponderous language such as MSA in an age of

nimble, clipped, and profane speech forms. The

point of reflection should not be whether to pro-

tect MSA but whether the language inherited

from the Jahiliya Bedouins—to paraphrase

Egypt’s Salama Musa (1887-1958)—is still an ad-

equate tool of communication in the age of in-

formation highways and space shuttles.28 Ob-

viously, this is a debate that requires a healthy

dose of courage, honesty, moderation, and prag-

matism, away from the usual religious emotions

and cultural chauvinism that have always

stunted and muzzled such discussions.

Taha Hussein, considered the “dean of

LINGUISTIC modern Arabic literature,” recognized

SCHIZOPHRENIA the futility of thinking of classical Arabic

as one unified and unifying language.

AND DECEIT “Nobody speaks it at home,” he wrote,

“[in] school, [on] the streets, or in clubs

Sherif Shubashy’s book Down with

… People everywhere speak a

Sibawayh If Arabic Is to Live on!29 seems to

language that is definitely not Arabic,

have brought these qualities into the debate.

despite the partial resemblance to it.”

An eighth-century Persian grammarian and fa-

ther of Arabic philology, Sibawayh is at the root

of the modern Arabs’ failures according to

… and relegating them to cultural bondage.”30

Shubashy. Down with Sibawayh, which pro-

In a metaphor reminiscent of Musa’s de-

voked a whirlwind of controversy in Egypt and

scription of the Arabic language, Shubashy

other Arab countries following its release in 2004,

compared MSA users to “ambling cameleers from

sought to shake the traditional Arabic linguistic

the past, contesting highways with racecar driv-

establishment and the Arabic language itself out

ers hurtling towards modernity and progress.”31

of their millenarian slumbers and proposed to

In his view, the Arabs’ failure to modernize was a

unshackle MSA from stiff and superannuated

corollary of their very language’s inability (or

norms that had, over the centuries, transformed it

unwillingness) to regenerate and innovate and

into a shrunken and fossilized mummy: a ceremo-

conform to the exigencies of modern life.32 But

nial, religious, and literary language that was

perhaps the most devastating blow that

never used as a speech form, and whose hallowed

Shubashy dealt the Arabic language was his de-

status “has rendered it a heavy chain curbing the

scription of the lahja and fusha (or dialect vs.

Arabs’ intellect, blocking their creative energies

MSA) dichotomy as “linguistic schizophrenia.”33

28 Salama Musa, Maa Hiya an-Nahda, wa Mukhtarat Ukhra 30 Choubachy, Le Sabre et la Virgule, pp. 10, 16-8.

(Algiers: Mofam, 1990), p. 233. 31 Shubashy, Li-Tayhya al-Lugha al-‘Arabiya, p. 18.

29 Sherif al-Shubashy, Li-Tahya al-Lugha al-‘Arabiya, Yasqut 32 Choubachy, Le Sabre et la Virgule, pp. 17-8; Shubashy, Li-

Sibawayh (Cairo: Al-Hay’a al-Misriya li’l-Kitab, 2004); Cherif Tahya al-Lugha al-‘Arabiya, p. 14.

Choubachy, Le Sabre et la Virgule: La Langue du Coran est-

elle à l’origine du mal arabe? (Paris: L’Archipel, 2007). 33 Shubashy, Li-Tahya al-Lugha al-‘Arabiya, pp. 125-42.

Salameh: Arabic Language / 55

For although Arabs spoke their individual MSA from dialects. Foreigners who are

countries’ specific, vernacular languages while versed in MSA, having spent many years

at home, at work, on the streets, or in the mar- studying that language, are taken aback

ketplace, the educated among them were con- when I speak to them in the Egyptian dia-

lect; they don’t understand a single word I

strained to don a radi-

say in that language.36

cally different linguistic

personality and make

Standard Arabic use of an utterly differ-

This “pathology” noted Shubashy, went

is a symbiotic almost unnoticed in past centuries when illit-

ent speech form when eracy was the norm, and literacy was still the

bedmate of Islam reading books and news- preserve of small, restricted guilds—mainly the

and the tool of papers, watching televi- ulema and religious grammarians devoted to the

sion, listening to the ra-

its cultural and dio, or drafting formal,

study of Arabic and Islam, who considered their

literary tradition. own linguistic schizophrenia a model of piety

official reports.34 and a sacred privilege to be vaunted, not con-

That speech form, cealed. Today, however, with the spread of lit-

which was never spontaneously spoken, eracy in the Arab world, and with the numbers

Shubashy insisted, was Modern Standard Ara- of users of MSA swelling and hovering in the

bic: a language which, not unlike Latin in rela- vicinity of 50 percent, linguistic schizophrenia

tion to Europe’s Romance languages, was dis- is becoming more widespread and acute, crip-

tinct from the native, spoken vernaculars of the pling the Arab mind and stunting its capacities.

Middle East and was used exclusively by those Why was it that Spaniards, Frenchmen, Ameri-

who had adequate formal schooling in it. He cans, and many more of the world’s transparent

even went so far as to note that “upward of 50 and linguistically nimble societies, needed to

percent of so-called Arabophones can’t even use only a single, native language for both their

be considered Arabs if only MSA is taken for acquisition of knowledge and grocery shopping

the legitimate Arabic language, the sole true whereas Arabs were prevented from reading and

criterion of Arabness.”35 Conversely, it was a writing in the same language that they use for

grave error to presume the vernacular speech their daily mundane needs?37

forms of the Middle East to be Arabic, even if As a consequence of the firestorm un-

most Middle Easterners and foreigners were leashed by his book, Shubashy, an Egyptian

conditioned, and often intimidated, into view- journalist and news anchor and, at one time,

ing them as such. The so-called dialects of Ara- the Paris bureau-chief of the Egyptian al-Ahram

bic were not Arabic at all, he wrote, despite the news group, was forced to resign his post as

fact that Egypt’s deputy minister of culture in 2006. The

book caused so much controversy to a point

like many other Arabs, I have bathed in this

linguistic schizophrenia since my very early that the author and his work were subjected to

childhood. I have for very long thought that a grueling cross-examination in the Egyptian

the difference between MSA and the dia- parliament where, reportedly, scuffles erupted

lects was infinitely minimal; and that who- between supporters and opponents of

ever knew one language—especially Shubashy’s thesis. In the end, the book was

MSA—would intuitively know, or at the denounced as an affront to Arabs and was ul-

very least, understand the other. However, timately banned. Shubashy himself was ac-

my own experience, and especially the evi- cused of defaming the Arabic language in

dence of foreigners studying MSA, con- rhetoric mimicking a “colonialist discourse.”38

vinced me of the deep chasm that separated

36 Shubashy, Li-Tahya al-Lugha al-‘Arabiya, pp. 125-6.

34 Ibid., p. 125.

37 Ibid., pp. 126-8, 130; Choubachy, Le Sabre et la Virgule,

35 Choubachy, Le Sabre et la Virgule, p. 119. p. 121.

56 / MIDDLE EAST QUARTERLY FALL 2011

A deputy in the Egyptian parliament—repre-

senting Alexandria, Shubashy’s native city— THE LATIN PRECEDENT

accused the author of “employing the discourse

and argumentation of a colonialist occupier, However understandable, this onslaught

seeking to replace the Arab identity with [the was largely unnecessary. For all his audacity,

occupier’s] own identity and culture.”39 Ahmad spirit, and probity, not to mention his provoca-

Fuad Pasha, advisor to the president of Cairo tive dissection of the linguistic and cultural co-

University, argued that the book “was added nundrum bedeviling the Arabs, Shubashy failed

proof that, indeed, the Zionist-imperialist con- to follow his argument to its natural conclu-

spiracy is a glaring reality,”40 aimed at disman- sion, and his proposed solutions illustrated the

tling Arab unity. Muhammad Ahmad Achour hang-ups and inhibitions that had shackled and

wrote in Egypt’s Islamic Standard that dissuaded previous generations of reformers.

Like Taha Hussein, Salama Moussa, and

Shubashy has taken his turn aiming another Tawfiq Awan, among others, Shubashy seemed

arrow at the heart of the Arabic language. at times to be advocating the valorization and

Yet, the powers that seek to destroy our adoption of dialectal speech forms—and the

language have in fact another goal in mind: discarding of MSA. But then, no sooner had

The ultimate aim of their conspiracy is none he made a strong case for dialects than he

other than the Holy Qur’an itself, and to promptly backed down,

cause Muslims to eventually lose their iden- as if sensing a sword

tity and become submerged into the ocean of

of Damocles hanging Big language

globalization.41

over his head, and re- unification

Even former Egyptian president Husni nounced what he would movements have

now deem a heresy and

Mubarak felt compelled to take a potshot at been met with

Shubashy in a speech delivered on Laylat al- an affront to Arab his-

tory and Muslim tradi- failure, wars,

Qadr, November 9, 2004, the anniversary of the

night that Sunni Muslims believe the Prophet tion—in a sense, resub- genocides, and

Muhammad received his first Qur’anic revela- mitting to the orthodox- mass population

ies of Arab nationalists

tion. Mubarak warned, movements.

and Islamists that he

I must caution the Islamic religious scholars had initially seemed

against the calls that some are sounding for keen on deposing.

the modernization of the Islamic religion, so His initial virulent critiques of the Arabic

as to ostensibly make it evolve, under the language’s religious and nationalist canon not-

pretext of attuning it to the dominant world withstanding, his best solution ended up rec-

order of “modernization” and “reform.” This ommending discarding dialects to the benefit

trend has led recently to certain initiatives of “reawakening” and “rejuvenating” the old

calling for the modification of Arabic vocabu- language. There were fundamental differences

lary and grammar; the modification of God’s

between Latin and MSA, Shubashy argued:

chosen language no less; the holy language in

which he revealed his message to the

Arabic is the language of the Qur’an and

Prophet.42

the receptacle of the aggregate of the Ar-

abs’ scientific, literary, and artistic patri-

mony, past and present. No wise man

38 See, for example, Muhammad al-Qasem, “Li-Tahya al- would agree to relinquish that patrimony

Lugha al-‘Arabiya … wa Yasqut Sibawayh… Limatha?” Islam

Online, July 10, 2004.

under any circumstances.43

39 Choubachy, Le Sabre et la Virgule, p. 181.

40 Ibid., p. 190.

41 Ibid., pp. 189-90.

42 Ibid., p. 190. 43 Shubashy, Li-Tahya al-Lugha al-‘Arabiya, pp. 133-4.

Salameh: Arabic Language / 57

In fact, contrary to Shubashy’s assertions, been doing in their daily lives.

this was a dilemma that Europe’s erstwhile us- Latin, nevertheless, persisted and endured,

ers (and votaries) of Latin had to confront be- especially as the language of theology and phi-

tween the fifteenth and eighteenth centuries. losophy, in spite of the valiant intellectuals who

For, just as MSA is deemed a symbiotic bedmate fought on behalf of their spoken idioms. Even

of Islam and the tool of its cultural and literary during the seventeenth and eighteenth centu-

tradition, so was Latin the language of the ries, students at the Sorbonne who were caught

church, the courts of Europe, and Western lit- speaking French on university grounds—or in

erary, scientific, and cultural traditions. Leav- the surrounding Latin Quarter—were castigated

ing Latin was not by any means less painful and risked expulsion from the university. In-

and alienating for Christian Europeans than the deed, the Sorbonne’s famed Latin Quarter is

abandonment of MSA believed to have earned its sobriquet precisely

might turn out to be for because it remained a sanctuary for the lan-

Successful Muslims and Arabs. Yet guage long after the waning of Latin—and an

language a number of audacious ivory tower of sorts—where only Latin was tol-

unification fifteenth-century Euro- erated as a spoken language. Even René

movements pean iconoclasts, un- Descartes (1596-1659), the father of Cartesian

daunted by the linguis- logic and French rationalism was driven to

normalize speech tic, literary, and theologi- apologize for having dared use vernacular

forms already cal gravitas of Latin or- French—as opposed to his times’ hallowed and

spoken natively. thodoxy, did resolve to learned Latin—when writing his famous trea-

elevate their heretofore tise, Discours de la Méthode, close to a cen-

lowly, vernacular lan- tury after Du Bellay’s Déffence.

guages to the level of legitimate and recognized Descartes’ contemporaries, especially lan-

national idioms. guage purists in many official and intellectual

One of the militant pro-French lobbies at circles (very much akin to those indicting

the forefront of the calls for discarding Latin to Shubashy and his cohorts today), censured

the benefit of an emerging French language was Descartes, arguing French to be too divisive

a group of dialectal poets called La Brigade— and too vulgar to be worthy of scientific, philo-

originally troubadours who would soon adopt sophic, literary, and theological writing. Yet, an

the sobriquet La Pléiade. The basic document undaunted Descartes wrote in his introduction:

elaborating their role as a literary and linguistic

avant-garde was a manifesto titled Déffence et If I choose to write in French, which is the

illustration de la langue Françoyse, believed language of my country, rather than in Latin,

to have been penned in 1549 by Joachim Du which is the language of my teachers, it is

because I hope that those who rely purely on

Bellay (1522-60). The Déffence was essentially

their natural and sheer sense of reason will be

a denunciation of Latin orthodoxy and advo-

the better judges of my opinions than those

cacy on behalf of the French vernacular. Like who still swear by ancient books. And those

Dante’s own fourteenth-century defense and who meld reason with learning, the only ones

promotion of his Tuscan dialect in De vulgari I incline to have as judges of my own work,

eloquentia—which became the blueprint of an will not, I should hope, be partial to Latin to

emerging Italian language and a forerunner of the point of refusing to hear my arguments

Dante’s Italian La Divina Commedia—Du out simply because I happen to express them

Bellay’s French Déffence extolled the virtues of in the vulgar [French] language.44

vernacular French languages and urged six-

teenth-century poets, writers, and administra-

tors to make use of their native vernacular—as

opposed to official Latin—in their creative, lit- 44 René Descartes, Discours de la méthode (Paris: Edition

erary, and official functions, just as they had G.F., 1966), p. 95.

58 / MIDDLE EAST QUARTERLY FALL 2011

Yet, the psychological and emotive domi- MSA is the preserve of a small, select num-

nance of Latin (and the pro-Latin lobby) of sev- ber of educated people, few of whom bother

enteenth-century Europe remained a powerful using it as a speech form. Conversely, what

deterrent against change. So much so that we refer to as “dialectal Arabic” is in truth a

bevy of languages differing markedly from

Descartes’ written work would continue vacil-

one country to the

lating between Latin and French. Still, he re-

other, with vast differ-

mained a dauntless pioneer in that he had dared ences often within the There are few

put into writing the first seminal, philosophical same country, if not

treatise of his time (and arguably the most influ- Arabs doing

within the same city and

ential scientific essay of all times) in a lowly popu- neighborhood … Need- critical work on

lar lahja (to use an Arabic modifier.) He did so less to say, this pathol- Standard Arabic

not because he was loath to the prestige and ogy contradicts the exi-

who do not end

philosophical language of his times but because gencies of a sound,

the French vernacular was simply his natural lan- wholesome national up being cowed

guage, the one with which he, his readers, and life! [And given] that into silence.

true nations deserving

his illiterate countrymen felt most comfortable

of the appellation re-

and intimate. It was the French lahja and its

quire a single common and unifying national

lexical ambiguities and grammatical peculiari- language … [the best solution I can foresee to

ties that best transmitted the realities and the our national linguistic quandary] would be to

challenges of Descartes’ surroundings and inoculate the dialectal languages with elements

worldviews. To write in the vernacular French— of MSA … so as to forge a new “middle

as opposed to the traditional Latin—was to MSA” and diffuse it to the totality of Arabs

function in a language that reflected Descartes’ … This is our best hope, and for the time

own, and his countrymen’s, cultural universe, being, the best palliative until such a day when

intellectual references, popular domains, and more lasting and comprehensive advances can

historical accretions. be made towards instating the final, perfected,

integral MSA.46

This is at best a disappointing and desul-

CONCLUSION

tory solution, not only due to its chimerical am-

This then, the recognition and normaliza- bitions but also because, rather than simplify-

tion of dialects, could have been a fitting con- ing an already cluttered and complicated linguis-

clusion and a worthy solution to the dilemma tic situation, it suggested the engineering of an

that Shubashy set out to resolve. Unfortunately, additional language for the “Arab nation” to

he chose to pledge fealty to MSA and classical adopt as a provisional national idiom. To expand

Arabic—ultimately calling for their normalization on Shubashy’s initial diagnosis, this is tanta-

and simplification rather than their outright re- mount to remedying schizophrenia by inducing

placement.45 In that sense, Shubashy showed a multi-personality disorder—as if Arabs were

himself to be in tune with the orthodoxies in want of yet another artificial language to

preached by Husri who, as early as 1955, had complement their already aphasiac MSA.

already been calling for the creation of a “middle Granted, national unification movements

Arabic language” and a crossbreed fusing MSA and the interference in, or creation of, a national

and vernacular speech forms—as a way of bridg- language are part of the process of nation build-

ing the Arabs’ linguistic incoherence and bring- ing and often do bear fruit. However, success in

ing unity to their fledgling nationhood: the building of a national language is largely

46 For the full text of Husri’s address, see Anis Freyha, al-

Lahajat wa Uslubu Dirasatiha (Beirut: Dar al-Jil, 1989), pp.

45 Shubashy, Li-Tahya al-Lugha al-‘Arabiya, pp. 142, 184-5.

5-8.

Salameh: Arabic Language / 59

dependent upon the size of the community and ing Sibawayh meant also deposing the greatest

the proposed physical space of the nation in ques- Arabic grammarian, the one credited with the

tion.47 In other words, size does matter. Small codification, standardization, normalization, and

language unification movements—as in the spread of the classical Arabic language—and

cases of, say, Norway, Israel, and France—can later its MSA descendent. Yet, calling for the

and often do succeed. But big language unifica- dethroning of one who was arguably the found-

tion movements on the ing father of modern Arabic grammar, and in the

other hand—as in the same breath demanding the preservation, inocu-

It is society and cases of pan-Turkism, lation, and invigoration of his creation, is con-

pan-Slavism, pan-Ger- tradictory and confusing. It is like “doing the

communities of

manism, and yes, pan- same thing over and over again and expecting

users that Arabism—have thus far different results,” to use Albert Einstein’s famous

decide the fate been met with not only definition of insanity. Or could it be that per-

of languages. failure but also devastat- haps an initially bold Shubashy was rendered

ing wars, genocides, and timid by a ruthless and intimidating MSA estab-

mass population move- lishment? After all, there are few Arabs doing

ments. Moreover, traditionally, the small lan- dispassionate, critical work on MSA today, who

guage unification movements that did succeed do not ultimately end up being cowed into si-

in producing national languages benefitted from lence, or worse yet, slandered, discredited, and

overwhelming, popular support among members accused of Zionist perfidy and “Arabophobia.”

of the proposed nation. More importantly, they Salama Musa,49 Taha Hussein,50 and Adonis51

sought to normalize not prestige, hermetic, (writ- are the most obvious and recent examples of

ten) literary languages, but rather lower, de- such character assassinations.

graded speech forms that were often already Ultimately, however, it is society and com-

spoken natively by the national community in munities of users—not advocacy groups, lin-

question (e.g., Creole in Haiti, Old Norse in Nor- guistic guilds, and preservation societies—that

way, and modern, as opposed to biblical He- decide the fate of languages. As far as the sta-

brew in Israel).48 tus and fate of the Arabic language are con-

Shubashy’s call of “down with Sibawayh!” cerned, the jury still seems to be out.

meant purely and simply “down with the classi-

cal language” and its MSA progeny. Overthrow-

49 Ibrahim A. Ibrahim, “Salama Musa: An Essay on Cultural

47 Ronald Waurdhaugh, An Introduction to Sociolinguistics Alienation,” Middle Eastern Studies, Oct. 1979.

(Malden, Mass.: Blackwell Publishing, 2002), pp. 353-74. 50 “Taha Hussein (1889-1973),” Egypt State Information Ser-

48 John Myhill, Language, Religion, and National Identity in vice, Cairo, accessed June 10, 2011.

Europe and the Middle East (Amsterdam and Philadelphia: 51 See Adonis, al-Kitab, al-Khitab, al-Hijab (Lebanon: Dar

John Benjamins Publishing Company, 2006), pp. 9-12. al-Adab, 2009), pp. 9, 14, 16-9.

60 / MIDDLE EAST QUARTERLY FALL 2011

You might also like

- An Introduction To Spoken Sinhala - Professor W.S. KarunatillakeDocument521 pagesAn Introduction To Spoken Sinhala - Professor W.S. KarunatillakeDanuma Gyi93% (14)

- Sample-Class Program and Teachers ProgramDocument2 pagesSample-Class Program and Teachers Programmaestro2483% (6)

- Ameen Rihani The FOUNDING FATHER of Arab American PoetryDocument21 pagesAmeen Rihani The FOUNDING FATHER of Arab American PoetryZainab Al QaisiNo ratings yet

- Rejoice o BethanyDocument5 pagesRejoice o BethanyChristianNo ratings yet

- Ethics and Good GovernanceDocument4 pagesEthics and Good Governancepradeepsatpathy100% (2)

- Arab Nationalism PDFDocument36 pagesArab Nationalism PDFApurbo Maity100% (2)

- Ameen Rihani's Humanist Vision of Arab Nationalism - by Nijmeh HajjarDocument15 pagesAmeen Rihani's Humanist Vision of Arab Nationalism - by Nijmeh HajjarBassem KamelNo ratings yet

- Arab Views of Black Africans and Slavery PDFDocument24 pagesArab Views of Black Africans and Slavery PDFDamean SamuelNo ratings yet

- Arab Nationalism: Mistaken IdentityDocument36 pagesArab Nationalism: Mistaken Identityumut66No ratings yet

- Arabesques 2Document13 pagesArabesques 2sarahNo ratings yet

- Ruba RawashdehhiDocument28 pagesRuba Rawashdehhizaina bookshopNo ratings yet

- Pre Islamic Arabia - The Land and The PeopleDocument12 pagesPre Islamic Arabia - The Land and The Peoplereza32393No ratings yet

- Arab Views of Black Africans and SlaveryDocument24 pagesArab Views of Black Africans and SlaveryRahim4411No ratings yet

- Criticism and Theory of Arabic SF: Science Fiction in "Arabic"Document41 pagesCriticism and Theory of Arabic SF: Science Fiction in "Arabic"Abdelhadi EsselamiNo ratings yet

- Module 6 - Arabic LiteratureDocument26 pagesModule 6 - Arabic LiteratureFrancis TatelNo ratings yet

- Patai and The Arab Mind Review and CommentaryDocument9 pagesPatai and The Arab Mind Review and CommentaryMark RowleyNo ratings yet

- 2ndquarter WEEK2 21st Century LiteratureDocument23 pages2ndquarter WEEK2 21st Century LiteratureNoelyn FloresNo ratings yet

- This Content Downloaded From 198.16.66.156 On Mon, 20 Sep 2021 08:17:32 UTCDocument16 pagesThis Content Downloaded From 198.16.66.156 On Mon, 20 Sep 2021 08:17:32 UTCMuhammad Ismail Memon Jr.No ratings yet

- Modern Hebrew Poetry 1960 1990Document16 pagesModern Hebrew Poetry 1960 1990Nahla LeilaNo ratings yet

- Syed Alphabetical Africa's Relationship Between Language and MeaningDocument9 pagesSyed Alphabetical Africa's Relationship Between Language and MeaningAnonymous NtEzXrNo ratings yet

- The Crows of The ArabsDocument11 pagesThe Crows of The ArabsMAliyu2005No ratings yet

- Identity and Alienation: A Study of Mahmoud Darwish's ID Card' and Passport'Document4 pagesIdentity and Alienation: A Study of Mahmoud Darwish's ID Card' and Passport'IJELS Research Journal100% (1)

- The Influence of The Arabic Language: The Muwashshah of Ibn Sahl Al-Andalusi An ExampleDocument8 pagesThe Influence of The Arabic Language: The Muwashshah of Ibn Sahl Al-Andalusi An ExampleYahya Saleh Hasan Dahami (يحيى صالح دحامي)No ratings yet

- The Influence of The Arabic Language: The Muwashshah of Ibn Sahl Al-Andalusi An ExampleDocument8 pagesThe Influence of The Arabic Language: The Muwashshah of Ibn Sahl Al-Andalusi An ExampleAJHSSR JournalNo ratings yet

- ThesisDocument60 pagesThesiskowshikbanerjee2000No ratings yet

- Hausa in The Twentieth Century: An Overview: John Edward PhilipsDocument30 pagesHausa in The Twentieth Century: An Overview: John Edward PhilipsoreoolepNo ratings yet

- حافظ ابراهيم Complete Description Hafiz IbraheemDocument4 pagesحافظ ابراهيم Complete Description Hafiz IbraheemAsmatullah Khan100% (1)

- Introduction To The Arabic LanguageDocument7 pagesIntroduction To The Arabic LanguageM PNo ratings yet

- Arab IdentityDocument7 pagesArab Identityagustin cassinoNo ratings yet

- Problems Spoken WrittenDocument5 pagesProblems Spoken WrittenHussein MaxosNo ratings yet

- Translation in Arab American and Arab British Literature (New YorkDocument4 pagesTranslation in Arab American and Arab British Literature (New YorkDahril VillegasNo ratings yet

- Islam and Iran A Historical Study of Mutual ServicesDocument24 pagesIslam and Iran A Historical Study of Mutual ServicesAfraNo ratings yet

- Allcity Arabic GraffitiDocument15 pagesAllcity Arabic GraffitihaekalmuhamadNo ratings yet

- Book Edcoll 9789004300156 B9789004300156 016-PreviewDocument2 pagesBook Edcoll 9789004300156 B9789004300156 016-PreviewsergiusNo ratings yet

- Arab American PoetsDocument11 pagesArab American PoetsimenmansiNo ratings yet

- The Roots of Her Tongue" (1) The Loss of A LanguageDocument5 pagesThe Roots of Her Tongue" (1) The Loss of A LanguageshelmabelNo ratings yet

- Best Sample Arabic Literature HistoryDocument8 pagesBest Sample Arabic Literature Historyerine5995No ratings yet

- Midterm Exam Eng233Document8 pagesMidterm Exam Eng233Mhmad MokdadNo ratings yet

- Criticism of Arab NationalismDocument16 pagesCriticism of Arab NationalismWanttoemigrate RightnowNo ratings yet

- A Map of Absence: An Anthology of Palestinian Writing on the NakbaFrom EverandA Map of Absence: An Anthology of Palestinian Writing on the NakbaNo ratings yet

- Hebrew Literature and Israeli HistoryDocument11 pagesHebrew Literature and Israeli HistorygujjarlibraryNo ratings yet

- Hebrew Final PPT 3Document32 pagesHebrew Final PPT 3Marelyn SalvaNo ratings yet

- Sudan ArabizationDocument4 pagesSudan ArabizationdebteraNo ratings yet

- Language City: The Fight to Preserve Endangered Mother Tongues in New YorkFrom EverandLanguage City: The Fight to Preserve Endangered Mother Tongues in New YorkNo ratings yet

- Colonizing Palestine: The Zionist Left and the Making of the Palestinian NakbaFrom EverandColonizing Palestine: The Zionist Left and the Making of the Palestinian NakbaNo ratings yet

- Excerpt From "The Image of Arabs in Modern Persian Literature" by Joya Blondel SaadDocument5 pagesExcerpt From "The Image of Arabs in Modern Persian Literature" by Joya Blondel Saadmimem100% (1)

- Counter - Representational Discourse of Islam in Islamophobic States: The Case of Mohja Kahf's The Girl in Tangerine Scarf (2006)Document6 pagesCounter - Representational Discourse of Islam in Islamophobic States: The Case of Mohja Kahf's The Girl in Tangerine Scarf (2006)IJELS Research JournalNo ratings yet

- Afro - Asian LiteratureDocument49 pagesAfro - Asian LiteratureJehanessa PalacayNo ratings yet

- Ishaq Al-Shami and The Predicament of The Arab-Jew in Palestine PDFDocument17 pagesIshaq Al-Shami and The Predicament of The Arab-Jew in Palestine PDFאמיר אמירNo ratings yet

- Ture. London: James Currey Nairobi: Heinemann Kenya Portsmouth, N. H.: HeineDocument2 pagesTure. London: James Currey Nairobi: Heinemann Kenya Portsmouth, N. H.: HeineFrannNo ratings yet

- African LiteratureDocument31 pagesAfrican LiteratureCanny ChalNo ratings yet

- Snir1IF PDFDocument46 pagesSnir1IF PDFsacripal100% (1)

- 2158-Article Text-2860-1-10-20120515Document12 pages2158-Article Text-2860-1-10-20120515Cherry ChoiNo ratings yet

- Uma Biografia de Zaki Al-Arsuzi (Capítulo 2)Document54 pagesUma Biografia de Zaki Al-Arsuzi (Capítulo 2)wilsonNo ratings yet

- Africas Variety of Arabo Islamic LiteratDocument14 pagesAfricas Variety of Arabo Islamic LiteratDIRAKIS YOANNISNo ratings yet

- Reflecting On The Life and Work of Mahmoud DarwishDocument22 pagesReflecting On The Life and Work of Mahmoud DarwishEditaNo ratings yet

- KRAMER Arab Nationalism - Mistaken IdentityDocument37 pagesKRAMER Arab Nationalism - Mistaken IdentitygregalonsoNo ratings yet

- Evolution Theory African Dramatic LiteraDocument15 pagesEvolution Theory African Dramatic LiteraAkpevweOghene PeaceNo ratings yet

- 21st CenturyDocument115 pages21st Centurychristian jay pilar0% (2)

- Adder OF Ivine Scent: T OHN LimacusDocument131 pagesAdder OF Ivine Scent: T OHN LimacusChristianNo ratings yet

- Eva Juliana PurbaDocument30 pagesEva Juliana PurbaChristianNo ratings yet

- Basic Law: The State Comptroller (5748 - 1988) (Unofficial Translation by Dr. Susan Hattis Rolef)Document3 pagesBasic Law: The State Comptroller (5748 - 1988) (Unofficial Translation by Dr. Susan Hattis Rolef)ChristianNo ratings yet

- Jadwal Baca Ladder of Divine AscentDocument1 pageJadwal Baca Ladder of Divine AscentChristianNo ratings yet

- Basic Law: The State Economy (5735 - 1975) (Unofficial Translation by Dr. Susan Hattis Rolef)Document5 pagesBasic Law: The State Economy (5735 - 1975) (Unofficial Translation by Dr. Susan Hattis Rolef)ChristianNo ratings yet

- Basic Law: Freedom of Occupation (5754 - 1994) (Unofficial Translation by Dr. Susan Hattis Rolef)Document2 pagesBasic Law: Freedom of Occupation (5754 - 1994) (Unofficial Translation by Dr. Susan Hattis Rolef)ChristianNo ratings yet

- BasicLawIsraelLands PDFDocument1 pageBasicLawIsraelLands PDFChristianNo ratings yet

- Basic Law: The President of The State (5724 - 1964) (Unofficial Translation by Dr. Susan Hattis Rolef)Document10 pagesBasic Law: The President of The State (5724 - 1964) (Unofficial Translation by Dr. Susan Hattis Rolef)ChristianNo ratings yet

- The Status and Issues of The Ecumenical Patriarchate of ConstantinopleDocument10 pagesThe Status and Issues of The Ecumenical Patriarchate of ConstantinopleChristianNo ratings yet

- Is The Western Wall Judaism's Holiest Site?: by F.M. LoewenbergDocument9 pagesIs The Western Wall Judaism's Holiest Site?: by F.M. LoewenbergChristianNo ratings yet

- 2018 06 14 Pakistan ENDocument2 pages2018 06 14 Pakistan ENChristianNo ratings yet

- Qaradawi's View On The Israeli-Palestinian Con Ict: by Nesya Rubinstein-ShemerDocument24 pagesQaradawi's View On The Israeli-Palestinian Con Ict: by Nesya Rubinstein-ShemerChristianNo ratings yet

- The Trinitarian Theology of Irenaeus of Lyons PDFDocument291 pagesThe Trinitarian Theology of Irenaeus of Lyons PDFChristian100% (3)

- Is There Any Democracy Fo Indegineous PeopleDocument2 pagesIs There Any Democracy Fo Indegineous PeopleChristianNo ratings yet

- A Jewish State: Theodor HerzlDocument1 pageA Jewish State: Theodor HerzlChristianNo ratings yet

- WWL2018 - 36 PalestinianTerritories CountryCard PDFDocument1 pageWWL2018 - 36 PalestinianTerritories CountryCard PDFChristianNo ratings yet

- How Anti-Semitism Prevents Peace: by David PattersonDocument11 pagesHow Anti-Semitism Prevents Peace: by David PattersonChristianNo ratings yet

- Reflection PLLPDocument1 pageReflection PLLPKen ServillaNo ratings yet

- Thesis Statement For Religion in Public SchoolsDocument4 pagesThesis Statement For Religion in Public Schoolsrobynnelsonportland100% (2)

- Communication TheoryDocument12 pagesCommunication TheoryKathNo ratings yet

- 1-Process of Democratisation - PRASANTA SAHOO-FINAL-1Document36 pages1-Process of Democratisation - PRASANTA SAHOO-FINAL-1Srishti50% (2)

- Gilyard - Composition and Cornel WestDocument177 pagesGilyard - Composition and Cornel WesthiphopclassNo ratings yet

- Creacion o Caos - RC SproulDocument50 pagesCreacion o Caos - RC SproulRuben Condori Apaza100% (1)

- Final MOTHER TONGUE MELCS With CG CodesDocument12 pagesFinal MOTHER TONGUE MELCS With CG CodesMarisol G. LausNo ratings yet

- Employee Information: Bilal Bilal Performance Assessment - Jacobs 2016Document4 pagesEmployee Information: Bilal Bilal Performance Assessment - Jacobs 2016billNo ratings yet

- Language and IdentityDocument12 pagesLanguage and Identityannacviana100% (1)

- Islam in Black America Identity, Liberation, and Difference in African-American Islamic ThoughtDocument179 pagesIslam in Black America Identity, Liberation, and Difference in African-American Islamic ThoughtChandell HudsonNo ratings yet

- Contoh Penulisan RujukanDocument2 pagesContoh Penulisan RujukaniffahdanishahNo ratings yet

- Diff Rep Vs Orbecido and Rep Vs IyoyDocument3 pagesDiff Rep Vs Orbecido and Rep Vs IyoyKael de la CruzNo ratings yet

- Republic of The Philippines PolytechnicDocument5 pagesRepublic of The Philippines PolytechnicEduardo TalamanNo ratings yet

- How Americans Spend Leisure TimeDocument55 pagesHow Americans Spend Leisure TimeBa Thi Van AnhNo ratings yet

- William H. Whyte: Seeing, Looking, Observing, and Learning From The CityDocument2 pagesWilliam H. Whyte: Seeing, Looking, Observing, and Learning From The CityWina Erica GarciaNo ratings yet

- A Call To Action For Animal RIghtsDocument2 pagesA Call To Action For Animal RIghtsDaniellee93100% (1)

- Mind ReaderDocument3 pagesMind Readereva.bensonNo ratings yet

- Ethnic Identity and AcculturationDocument17 pagesEthnic Identity and AcculturationYuana Parisia AtesNo ratings yet

- Chapter IIDocument30 pagesChapter IIJarito Linno MorilloNo ratings yet

- Marriage Plan B-Wps OfficeDocument2 pagesMarriage Plan B-Wps Officeokasamuel068No ratings yet

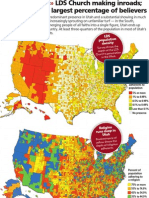

- LDS Census MapDocument1 pageLDS Census MapThe Salt Lake TribuneNo ratings yet

- English Communication and CompositionDocument6 pagesEnglish Communication and CompositionRocky100% (1)

- Smith Fotip Pop Cycle 3Document5 pagesSmith Fotip Pop Cycle 3api-378363663No ratings yet

- MAKALAH Cooperative PrincipleDocument7 pagesMAKALAH Cooperative Principlenurul fajar rahayuNo ratings yet

- KierkegaardDocument6 pagesKierkegaardKathleenReyesNo ratings yet

- Culture Inclusion Reflection Assignment 1-BecharaDocument5 pagesCulture Inclusion Reflection Assignment 1-Becharaapi-362170340No ratings yet

- Human Flourishing in Science and Technology: Technology As A Mode of RevealingDocument26 pagesHuman Flourishing in Science and Technology: Technology As A Mode of Revealingmirai desuNo ratings yet