Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Almanac AP 1984

Almanac AP 1984

Uploaded by

HeianYi0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

12 views25 pagesExcerpt of an introduction on a previous edition of the Almanac of American Politics

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

PDF or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentExcerpt of an introduction on a previous edition of the Almanac of American Politics

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF or read online from Scribd

Download as pdf

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

12 views25 pagesAlmanac AP 1984

Almanac AP 1984

Uploaded by

HeianYiExcerpt of an introduction on a previous edition of the Almanac of American Politics

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF or read online from Scribd

Download as pdf

You are on page 1of 25

xi

——

THE POLITICS OF CULTURAL VARIETY

‘No other nation has apolitical system whose besic character has remained unchanged fr

longa the United States, We have been holding presidential and congressional elections for

195 years now, and in that time just 39 men have eld our highest office. The senior senator

from New Hampshire stil sits at Daniel Webster's desk; the inkwell is kept filled and sand is

provided for blotting. Our political parties, though not mentioned in the Constitution, are

nearly as old, The Democratic Party was formed inthe early 1830s, under Andrew Jackson's

segs, by that master politician Martin Ven Buren; the Republican Party sprang up almost

Spontaneously in reation to Stephen Douglas's Kansas-Nebraska Act of 1854 and von the

‘Congressional elections that year. The two have remained our major parties ever since. The

‘winner of the Democratic presidential and vice presidential nominations in 1984 willbe part

‘of an unbroken string going back to Jackson and Van Burea, and the Republican nominees

wil be part of a string beginning with John C. Fremont and Wiliam Dayton. No other

ration’ political system comes close to matching ths continuity.

‘Beneath the veneer of continuity, American poiticsand American ife—have ofcourse

changed. The nation of 3 million mostly English colonists who chose the first president in

1790--that is the white males with sufiient property to vote—is a very different place fom

the continental nation of 228 millon which votes in 1984. More to the point, the United

States of 1984 ia very different nation from the United States that launehed the D-Day in-

‘vasion of 1944 or the United States that was unknowingly about to embark on the Vietnam

‘war in 1964, The nation today is large in population, vastly richer (despite the protracted re-

‘cession that began in 1929), more tolerant of diversity, economically more intertwined with

the rest ofthe world Its politics has changed as wel

‘But in ecent history there has been no clear divide, noone date you ean point to—no 1789,

no 1865, no 1914—when everything changed. Yet it is apparent that the rules which

‘governed American politics inthe 1940s or even as recently as the middle 1960s no longer ob-

tain. Examples

Te used to be assumed that there was @ natural Democratic majority in presidential

clections, a majority which would give the Democrats victory absent unusual

‘ircumstances like raging inflation or war. But in the lst four presidental elections

Democrats have averaged 43% of the vote.

Tt used to be assumed that the American people would overwhelmingly reject

deviations from moral norms. As recently 25 1963, remarriage cost Neon Rockefeller

his ead in poll forthe Republicen presidential nomination. Since 1981 the nation has

had a president—a Republican who proclaims himself a conservative—who has been

divorced and remarried. In the middle 1960s, it was unheard of for issues like

abortion, marijuana, pornography, or homosexuality to arse in polities; everyone was

against them. Today all have been explicitly or implicitly legalized, and those who

want to see those decision reversed have been continually frustrated.

Teused tobe assumed that the American people were united in support of «bipartisan

foreign policy and would rally unanimously tothe flag in time of war. Tht, afterall,

had been the experience of World War II (though not of previous wars) and the

postwar years, But that was not how Americans reacted to the Vietnam war,

xii. © THE POLITICS OF CULTURAL VARIETY

‘+t used to be assumed thatthe average American thought of himseif as “the little

‘guy as an average person, a working person far below te tp level of society, & per~

son whose basi tastes and morality nonetheless typified the nation. Americans prided

themselves on being normal, average, ordinary. Today that is far less often the case

People celebrate their differentnes, not thet sameness; their distinction, not th

normality, Politically, there is this effect: a decline in the confidence that working

‘class Democrats and middle clas Republicans had that they represented the solid

middle majority of Americans. Instead, we have developed & politics of cultural

‘variety politics in which cultural and socal characteristics which used tobe thought

irrelevant to polities are increasingly determining political attitudes.

‘+ Te used to be assumed that virtually all Americans lived in nuclear families with

several children. That pattern is no longer universal. Because of rising divorce rates,

And lower birth rates, 26% of households no longer contain families, and a majority of

hhouscholds-—61%—contain no children

‘This polities of cultural variety has developed ina nation where people have, gradually, be-

come more alike economically, more alike ethnically and repionally, but more diferent

culturally. Since these changes are not obvious, lt ws lok at each in tur,

‘Americans have become more alike economically. Lefish critics of the American economic

system lke to point out thatthe income distribution—the percentage of income going to the

highest, lowest, and middle-income groups—has not ehanged much since 1945. True enough

But real incomes have grown enormously—more than at anyother time in American history.

Real income per person was 245 times in 1980 what it was 40 years before. This still

understate the change, since a larger percentage of Americans were children in 1940: ral

come per adult as increased more than 2 times in 40 years.

Such a vast increase in real income does not obliterate income diferentials. Some people

arestll lot richer than others. But it makes income disparities much easier to tolerate—and

Tess relevant to daily life. Most Americans of 1945 had incomes below the poverty levels oft

day. Most Americans today have real incomes at levels the Americans of 1945 would have re-

tarded as near the top of the scale, In 1960, just 19% of American families had incomes over

'525,000 in 1980 dollar; in 1980, 39% did, And the percentage with incomes under $10,000,

in 1980 dollars, fell rom 28% to 19%, That means, roughly, that twice as many Americans

have incomes that provide a comfortably secure standard of living, and tht the proportion of

low income Families has dropped vastly. That doesn't mean that Americans universally

regard themselves as afluent. But it does mean, for all his complaints about the economy, the

‘ordinary American today takes for granted an access to necessities and many luxuries which

his counterpart along generation ago would have considered utterly beyond his means. Even

‘unemployed Americans today need not worry about sending their children to bed hungry, a8

‘many did 40 years ago. Americans may complain, but the urgency of their complains is

suey mush es han how of 4 or even 20 year a when ny ep ere hey could

‘ot afford necessities.

Real income rises have ather politically significant effects. Despite the model showing

stable distribution of income, there isa vast amount of social mobility in the United States,

both upward and downward, In times of growing real incomes, the possibilities for upwar

‘mobility are great, and the rewards are often greater than people ever dreamed. And rising

‘eal income levels cushion downward social mobility. In such times you can hold job several

notches below your father’s occupational level and stil enjoy the same income. So in

THE POLITICS OF CULTURAL VARIETY xiii

politically significant terms, Americans in 1945-75 came tobe more alike: more alike in the

$ense that they became, apparently securely, part of large, fluent middle-income segment

‘ofthe population. Te sense of deprivation that helped to cement many people in the New

Deal Democratic coalition, the sense af precarious privilege that helped to keep many others

solidly Republican-—these have both tended to fad, silently and gradually, in the long

‘generation after World War IL

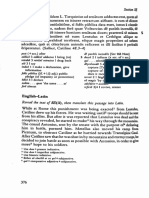

‘One way to measure the narrowing income gap between parts ofthe country isto show

cach state's per capita income as a percentage ofthe national average. The following table

‘oes this for 1940, 1960, and 1980. To some extent it still vertates regional differences,

‘Since a larger percentage of residents of southern sate are children; they count the same for

per capita income figures as single householders in New York or California, who absorb

‘uch higher incomes in just basic living expenses.

‘State Per Capita Income as Percentage of National Average

14019601980 194019601980

EAST west

pe m9 6 aK me

kag W123 ca ws

MN ieee ete 3 w ie oe

MD ip 10s Nv 000113

DE iri ei | 10 WA tie ge | te

ng sae a oe 106

MA ma 1 106 co Bt

Rr Ds | OR ioe 10088

PA cole cole AL Hom

Nt % 886 Mr % «0

ME ee se sl 1D eet is

vr S 8 2 NM 6 8 8

ur aoe

sour

x no % 10

Mipwest vA a ee)

IL oat OK, ewe

xs 1 (98105 i 6 8 OM

MM 14106105 1A eee

MN 2 fe GA SSS

On p os 8 Ne ea

NE (8 w @ nm

ne es N Sele ora st

wi 3 9 Ky “2

No es AL me

N Rk aR B 2 1%

ND 3% OR sc mo

3D ) MS OK

‘Thus the gap between New York and Mississippi was 147-36 in 1940 and 108-69 in

1980-—still considerable, but also offset in considerable part by the lower cost of living in

Misisipp, Northeastern states are regressing toward the mean, though we should remem

‘beethat in the period on the table, the national per capita income, in real dollars, roughly tri-

pled, and 99% of a tripled income is a lot more than 123% of the original amount

Metropolitan areas typically have higher incomes than rural ones, but the gap again has

xiv THE POLITICS OF CULTURAL VARIETY

narrowed. Local events, lke the collapse of the textile industry in Massachusetts and Rhode

Island in the postwar years, are readily apparent. So is the continuing rise in southern

‘incomes. It should not have been so surprising that they woud rie in time of war that usually

Ihappens in backward parts of a country. But their rise in the 1960-80. period is an

‘extraordinary event, and one cause may bave been the civil rights revolution, which made the

‘South more attractive to talented blacks, reduced black outmigraton, and gave blacks more

‘opportunity 1 be economically productive.

Political preferences in the America ofthe 1940s correlated to afar degre with income,

Republican strength was greater than average in high income stats like Now York,

Connecticut, New Jersey, and Delaware (all of which Thomas Dewey cartied over Harry

‘Truman in 1948), while Roosevelt and Truman carried virtually every state with incomes

below the national lve (the exceptions were rockribbed Republican since the Civil War:

Maine and Vermont, Nebraska and Kansas). But today there is virtually no correlation

between income level and politcal preference. Utah, with one of the lowest per capita,

incomes, was the nation’s most Republican state in 1980; its low per capita income reflects

the large numberof children inthe state, and family tis andthe presence of children began,

{tobe correlated with Republican preference by 1980. Inthe Midwest high income Minos i

‘more Democratic than low income Tndiana; in the East New Hampshire is the most

‘Republican and one of the lowest income stats. Only in the South does the old correlation of

conomic situation and political preference still hold, to some extent: the oibrch states of

‘Texas, Louisiana, and Oklahoma all had fastsing incomes inthe late 1970s and trended

sharply to Ronald Reagan's Republicans in 1980. Even so, economic factors seem less and

Jess to explain politcal preference, and cultural variety seems todo it more and mor.

Americans have tended to become more alike ethnically and regionally. Because writers of|

the history of racial and ethnic groups have concentrated on discrimination and oppression,

‘we lose sight of how tolerant and welcoming the United Stats has been. Comparison with

‘other countries is illuminating: almost every athe country with a multiracial population has 2

‘worse race problem, and few countries have been as open to immigrants as we have during

‘mast of our existence (and are today infact, if notin legal theory). Certainly i is clear that

‘ethnic and religious origin have become much ess important as barriers to advancement Itis

‘lear aswell that being & Catholic ora Jew, being of Italian or Polish descent, is simply a less

‘istinctive experience in the America of the 1980s than it was inthe America of, say, the

1950s, Religious practic is far les likely to set one apart; contact between various groups is

{greater intermarriage is so common that many people fear these groups will lose their

distinctiveness entirely. Ethnic festivals and ethnic studies programs show that people are

stllnterested in their diverse origins. But even if thei origins at different, their preset lives

re rather like those of other Americans.

Racial eiferenes still matter much more. But we should not lose sight ofthe fact thatthe

Civil rights revolution ofthe 1960s changed the lives of black-—and many white—Americans

‘more than any other peaceful change in anyother nation’s history. To understand that, you

only have to recall that many serious and well-informed people, of both races, said that

southern whites would never accept blacks on the ob or inthe poling booth in restaurants of

in their neighborhoods or in thei childrens schools. Now outward resistance to any ofthese

forms of integration has just about vanished. Its true that racial discrimination in housing

still seems the rule, although even here some progress being made: small numbers of blacks

now lve in hundreds of suburbs and city neighborhoods acrass the nation which, a generation

ago, would have been all white, And there wil always be some concentration of blacks in

THE POLITICS OF CULTURAL VARIETY xv

neighborhoods, by chee, forthe tame reason there is some clustering of whites of particular

cthnie backgrounds or cultural preferences: pople like to live in neighborhoods with others of

similar tastes, Inthe meantime, there is no question that there has been avast change in white

attitudes and black opportunites, just as there is no question that itis dificult for blacks to

‘overcome the handicaps imposed by generations of slavery and segregation.

Regional differences have also become muted. This is not just because announcers on

Dallas TV have the same accents as those on Boston TV; local accents have some vitality let.

‘A more important reason is thatthe income gap between the regions has narrowed. In 1940

[New York's per capita income was four times Mississippi's; today New York’s per capita

income is about SO higher, but much ofthe diference is eaten up by a higher cost of living.

‘The South and West now have metropolitan areas as rich and cosmopolitan as any in the

[Northeast and universities as learned and well endowed. The South is no longer set apart

from the rest ofthe country by virtue of racial segregation or the presence of Backs.

"Many of the historically important divisions in American politics have been regional and

ethni, Democrats could once count on carrying «Solid Sout, and blacks used to vote (where

they could) almost unanimously forthe party of Linco. The Irish immigrants of the 1840s,

‘encountering Whig and later Republican Yankees, found they were weleomed into the

‘minocty Democratic Party—to the point where it wasn'ta minority any more. Some later im

migrants, shut out of poltce by the Irish, responded by becoming Republicans or even

Socialists, Franklin Roosevel’s New Deal brought disparate and sometimes hostile groups

together into the Democratic Party: blacks and southern whites, most of the products of

1840-1924 immigration, The result was # majority party made up of self-conscious

‘minorities, just as the popular base ofthe minority Republican Party were the white Anglo-

‘Saxon Protestants who considered themselves, inaccurately, as a majority group.

"The FDR coalition didn't last. For some years its breakup was considered the result of

‘quarrels that might be patched up. Southern whites abandoned Democratic presidential and

‘many local candidates in the middle 1960s, n protest of the national party's support of civil

tights laws, By 1970 in state races and 1976 inthe presidental race, many southern whites

‘voted Democratic agai, But as the 1980 election showed, this was not an invariable loyalty

‘The real eason the Democratic coalition could not last was thatthe ethnic and economic con-

-sousness of its members—or their chldren—was fading. The minorities, whether they were

‘Jews or southern whites, blacks ot Irish or Italians or Poles, weren't very self-conscious any

‘more. They were much less often the abject of discrimination or persecution. They needed

less from government or politics. They were becoming much more like other Americans—

and other Americans much more like them.

‘Americans are becoming more different culturally. In vivid contrast to the era of

‘onformism, Americans value themacives now for how they ere diferent from each other

more than for how they re alike. What has happened is this. Inan increasingly affiuent and

tolerant nation, people have been able to choose their own identity. Distinctivenes is no

longer something determined by birth, but something you ean chonse. A once economically,

and ethnically heterogeneous people have become culturally heterogeneous.

‘The results that increasingly we havea politics of cultural variety. This has been replacing

the polities of economic class which was inspired by the New Deal andthe polities of ethnic,

" tacil, and regional rivalries which was never entirely eradicated by the New Deal, and

important vestiges of which survived the Roosevelt years. Such a process i never total, not at

"least in a country at peace and untouched by economic cataclysm.

“The emergence of the polities of cultural variety i further camouflaged by the fact that

You might also like

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5823)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1093)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (852)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (590)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (898)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (540)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (349)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (823)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (122)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (403)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- Chess Novag Jasper SpecialDocument21 pagesChess Novag Jasper SpecialHeianYi100% (1)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- HeresyAndAuthority (Peters) WholeDocument322 pagesHeresyAndAuthority (Peters) WholeHeianYi100% (6)

- Inclusiveness of NationalitiesDocument59 pagesInclusiveness of NationalitiesHeianYiNo ratings yet

- Reading Latin 416 To 435Document20 pagesReading Latin 416 To 435HeianYiNo ratings yet

- Reading Latin 376 To 395Document20 pagesReading Latin 376 To 395HeianYiNo ratings yet

- Mercer MM Gpi Pension Report 2012Document66 pagesMercer MM Gpi Pension Report 2012HeianYi100% (1)

- Reading Latin 136 To 155Document20 pagesReading Latin 136 To 155HeianYiNo ratings yet

- Reading Latin 496 To 515Document20 pagesReading Latin 496 To 515HeianYiNo ratings yet

- Reading Latin 156 To 175Document20 pagesReading Latin 156 To 175HeianYiNo ratings yet

- Reading Latin 296 To 315Document20 pagesReading Latin 296 To 315HeianYiNo ratings yet

- Reading Latin 216 To 235Document20 pagesReading Latin 216 To 235HeianYiNo ratings yet

- Reading Latin 056 To 075Document20 pagesReading Latin 056 To 075HeianYiNo ratings yet

- Reading Latin 176 To 195Document20 pagesReading Latin 176 To 195HeianYiNo ratings yet

- Reading Latin 076 To 095Document20 pagesReading Latin 076 To 095HeianYiNo ratings yet

- Reading Latin 036 To 055Document20 pagesReading Latin 036 To 055HeianYiNo ratings yet