Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Millar1991 PDF

Millar1991 PDF

Uploaded by

narulitta rianOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Millar1991 PDF

Millar1991 PDF

Uploaded by

narulitta rianCopyright:

Available Formats

The Fundal Pile: Bleeding Gastric Varices

By A.J.W. Millar, R.A. Brown, I.D. Hill, H. Rode, and S. Cywes

Cape Town, South Africa

0 Bleeding from esophageal varices is a common cause of ered. This report describes the management and

major upper gastrointestinal tract blood loss in children with outcome of 5 patients who underwent emergency

portal hypertension but usually ceases spontaneously or is

operation to control continued bleeding from gastric

satisfactorily managed by nonoperative measures. Massive

hemorrhage from gastric fundal varices may be difficult to

fundal varices.

control with compression and sclerotherapy; in these cases,

a direct surgical approach may be indicated. Since 1964.27

MATERIALS AND METHODS

children have undergone aggressive injection sclerotherapy Over the period from 1984 through 1988, 27 patients were

for bleeding esophageal/gastric varices. Nine (6 with portal treated at Red Cross War Memorial Children’s Hospital, Cape

vein thrombosis) bled from gastric fundal varices. In 5 of Town for upper gastrointestinal tract bleeding from varices second-

these, medical management and sclerotherapy failed to ary to portal hypertension (Table 1). Their ages at first presenta-

control the acute bleed. In all 5 there was “rupture” of a large tion ranged from 2 to 11 years. There were 12 boys and 15 girls.

gastric fundal varix or “pile” and bleeding was controlled at Initial management included resuscitation with restoration of

emergency laparotomy by underrunning the varices through blood volume and clotting factors, followed within 24 hours by

a high anterior gastrotomy. Four have subsequently been endoscopic identification of the bleeding site. A total of 5 to 10 mL

successfully managed by continued sclerotherapy and one of ethanolamine oleate was injected at the site of the bleed as well

patient with cirrhosis has died of liver failure. In 3 of the as proximally in an upward spiral fashion for a distance of 10 cm.

survivors both esophageal and gastric fundal varices have Initially the sclerosant was injected into the varices using a rigid

been completely obliterated. No further life-threatening hem- esophagoscope. Since 1985 paravariceal injections using a flexible

orrhage has occurred in any case during a follow-up period of fiberoptic endoscope have been used. Gastric varices were identi-

1 to 6 years. Bleeding from gastric varices is more common fied as the source of bleeding in 2 patients at initial endoscopy and

than previously recorded and more difficult to control by in 7 patients subsequently4 after 1 injection and 3 after 2

nonoperative management, including injection sclerother- injections. In 5 of these 9 cases sclerotherapy and other conserva-

apy. In uncontrolled hemorrhage from gastric varices, surgi- tive measures were unable to control active bleeding (Tables 1 and

cal underrunning offers a means of providing initial control. 2).

Thereafter, the inevitable variceal recurrence may be success- Surgical exploration was performed through an upper midline

fully treated with sclerotherapy. abdominal incision and a high anterior gastrotomy. Blood clot was

Copyright o 7997 by W.B. Saunders Company evacuated, and the gastric varices were identified. In 4 cases a

continuous jet of blood was seen arising from one of approximately

INDEX WORDS: Portal hypertension; gastric varices. 4 large varices that coursed from the gastric fundus toward the

esophagogastric junction. In the fifth patient a fresh blood clot

identified the site of the bleed. Commencing with the actively

E SOPHAGEAL VARICES are a common cause

of serious upper gastrointestinal tract hemor-

rhage in children.‘” Morbidity and mortality are

bleeding varix, each of the varices was underrun throughout its

extent from the esophagogastric junction distally using a 2/O

absorbable suture. In all 5 patients there was complete control of

worse in those with varices secondary to an intrahe- the bleeding.

Table 2 shows the long-term follow-up of the 5 patients. One

patic cause rather than extrahepatic portal vein

patient with cirrhosis of the liver died of liver failure 6 months after

obstruction.4 In most cases the bleeding site in the surgery. A further patient developed an esophageal stricture that

esophagus can be identified at endoscopy and con- responded well to dilatation. The surviving patients are well 26 to

trolled with sclerosant injection.*x’jThereafter, preven- 59 months later, with completely obliterated varices in 3. These 4

tion of further bleeding from esophageal varices is patients have continued to undergo follow-up endoscopy at increas-

ing intervals.

possible with repeated endoscopic injection sclerother-

apy.j,’ DISCUSSION

A small proportion of patients presenting with an

Most acute variceal bleeds in children respond to

acute variceal bleed fail to respond to conservative

nonoperative management and bleeding ceases spon-

measures, including intravenous vasopressin infusion,

balloon tamponade, and injection sclerotherapy. One

reason for failure is bleeding from gastric varices.8,9

From the Departments of Paediam’c Surgery and Paediam’cs,

Not only are they difficult to identify while there is Institute of Child Health and Red Cross War Memorial Children’s

active bleeding, but they may be inadequately com- Hospital, Cape Town, South Africa.

pressed by a Sengstaken tube; are difficult to inject, Date accepted: May 9, 1990.

particularly when they protrude into the lumen of the Address reprint requests to A.J. W. Millar, MD, Department of

Paediatric Surgery, Institute of Child Health, Red Cross War Memorial

gastric fundus at the esophagogastric junction; and Children’s Hospital, Rondebosch 7700, Cape Town, South Africa.

they may be associated with major complications.‘O,ll Copyright o 1991 by W.B. Saunders Company

In these patients emergency surgery must be consid- 0022-3468/91/2606-0015$03.00/0

JournalofPediafricSufgery, Vol26,No6(June),1991: ~~707-709 707

708 MILLAR ET AL

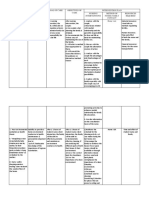

Table 1. Injection Schlerotherapy Management of Bleeding Esophageal and Gastric Varices, Red Cross War Memorial Children’s Hospital

(January lg84-June 1989)

Follow-Up

Total Gastric Mean No. of Outcome

No. of Patients Varices Surgery Injections Until Duration

Etiology (n = 27) (n = 9) (n = 5) Obliteration (mo) Cured Died

Portal vein thrombosis 20 7 4 4.3 20.2 18* 0

(5-59)

Cirrhosis 5 2 1 4.5 33.8 3 2

(45-46)

Hepatic fibrosis 2 0 0 5 41.5 2 0

(3746)

“Two still have a single residual varix after 6 and 7 injections, respectively.

taneously.1’3 Management of those patients who con- strated in 3 of the present patients, attempted gastric

tinue bleeding may include immediate injection scle- variceal compression by tamponade with a Blakemore-

rotherapy or emergency surgical procedures, such as Sengstaken tube may be unsuccessful. In 2 patients it

esophagogastric devascularization or portasystemic did not control the initial hemorrhage; in the third,

shunting.4.‘2 Unfortunately, some postsurgery rebleed- bleeding recommenced immediately on deflation of

ing and development of long-term encephalopathy the balloon.

can be anticipated in shunted patients.4Z13”4Because Recently, Hosking and Johnson proposed a classifi-

of the high morbidity and occasional mortality with cation of gastric varices based on their dominant

emergency surgery, endoscopic sclerotherapy to con- location within the stomach.8 Their classification

trol bleeding from varices has become popular.1X6Z7 divides gastric varices into 3 types. Type II, in which

Howard et al report variceal obliteration by injec- there are gastric varices converging on the cardia, and

tion sclerotherapy in 92% of children with an extrahe- which may be accompanied by smaller esophageal

patic cause of portal hypertension and 75% with an varices above the esophagogastric junction, repre-

intrahepatic cause.’ Of the 108 patients in their sents the bleeding gastric varices encountered in the

series, none had gastric varices identified as the children in this series. The incidence of gastric varices

source of the initial bleed but one child died as a causing variceal hemorrhage in Hosking’s series of

result of uncontrolled hemorrhage from esophagogas- more than 200 patients was 6%. A further 9%

tric varices. Twelve patients subsequently rebled and developed gastric varices during long-term follow-up,

4 were found to be bleeding from gastric varices.5 In many after repeated esophageal variceal sclerother-

contrast, a third (9/27) of children with upper gas- apy. Controversy exists as to whether the gastric

trointestinal bleeding secondary to portal hyperten- varices occur ab initio or secondary to obliterative

sion in this series were found to be bleeding from sclerotherapy. The increased incidence of gastric

gastric varices. The diagnosis of bleeding from gastric varices postsclerotherapy may be due to the develop-

rather than esophageal varices may be difficult in the ment of submucosal collaterals around the fundus. In

acute phase because the field is obliterated by active two of the present patients bleeding from gastric

bleeding and the gastroesophageal cardia is relatively varices occurred before any injection sclerotherapy,

inaccessible even with the flexible endoscope. Once suggesting that they were primary in nature.

identified as the source of bleeding, it may still be The name “fundal pile” was thought appropriate

technically difficult to inject sclerosant into or around because of the resemblance of the dependant bleed-

a varix high up on the gastric fundus. As demon- ing fundal varix to a prolapsed bleeding hemorrhoid.

Table 2. Follow-Up After Surgical Control of Gastric Variceal Hemorrhage in 5 patients

Age at Duration of No. of Re- Further

Varices Operation Follow-Up bleeds From Variceal current

W Diagnosis &no) Varices Injections Status

4.5 PVT 59 0 3 No varices, stricture dilated

4.5 PVT 35 0 3 Grade II varix, injected at 24 mo

12 PVT 29 0 2 No varices

4 PW 26 0 2 No varices

10.9 Hepatitis, cirrhosis 5 5 3 Died; liver failure; varices still present

Abbreviation: PVT. portal vein thrombosis.

BLEEDING GASTRIC VARICES 709

In both conditions there is a submucosal varix protrud- could not be controlled by these methods. In all such

ing into the lumen of the gastrointestinal tract. They cases emergency surgery was lifesaving because imme-

both complicate with fresh bleeding and are related diate control of hemorrhage was obtained. Rather

to alimentary canal sphincters-the lower esophageal than use an extensive technically difficult procedure

sphincter and the internal anal sphincter. It is possi- in a hemodynamically unstable patient, we chose a

ble the pinch-cock action of these sphincters plays a relatively simple surgical procedure. The total opera-

role in development of the varix and precipitation of tion time was short, and control of hemorrhage was

bleeding by impeding venous return and increasing rapidly achieved.

intravariceal pressure. The metaphor is further sus- Although there is control of the acute bleed, these

tained by a recent publication, in which it is suggested patients are still at risk because the underlying portal

that bleeding esophageal varices may be treated by hypertension remains. Therefore, repeated injection

“banding” as advocated for hemorrhoids.‘5 sclerotherapy is advocated after surgery until com-

The authors’ management of children with bleed- plete variceal obliteration is obtained. In the present

ing varices entails resuscitation, followed by pitressin series this took a mean of 4 to 5 injections, which is

and immediate injection sclerotherapy, with balloon similar to the 5- to 6-injection sessions reported in the

tamponade if necessary to temporarily control blood Howard et al series.’ The efficacy of this approach is

loss. Subsequent injections are continued at weekly confirmed in 4 of 5 patients in the present series, in

intervals until there is complete variceal obliteration. whom there has been long-term control of variceal

This has been most successful with bleeding from hemorrhage. In 3 of the 4 there were no varices at

esophageal varices and this experience is similar to most recent endoscopy. The one death that occurred

that reported previously.5,6.‘6However, this approach was 6 months after underrunning of bleeding gastric

is less successful when bleeding is from gastric varices varices and was due to progressive liver failure and

and in 50% of the patients in this series blood loss not to variceal hemorrhage.

REFERENCES

1. Fonkalsrud EW, Myers NA, Robinson MJ: Management of tric varices. An endoscopic study of 50 cases. Arch Surg 92:944-947,

extrahepatic portal hypertension in children. Ann Surg 180:487- 1966

493,1974 10. Yassim YM, Eita MS, Hussein A: Endoscopic sclerotherapy

2. Webb LJ, Sherlock S: The aetiology, presentation and natural for bleeding gastricvarices. Gut 26 A:1105, 1985 (abstr)

history of extrahepatic portal venous obstruction. Q J Med 48:627- 11. Trudeau L, Prindiville T: Sclerosis of bleeding gastric

639.1979 varices. Gastroenterology 84:1338,1983 (abstr)

3. Househam KC, Bowie MD: Extrahepatic portal venous ob- 12. Superina RA, Weber JL, Shandling B: A modified Sugiura

struction-A retrospective analysis. S Afr Med J 64:234-236, 1983 operation for bleeding varices in children. J Pediatr Surg 18:794-

4. Bismuth H, Franc0 D, Alagille D: Portal diversion for portal 799,1983

hypertension in children. Ann Surg 192:18-24,198O 13. Voorhees AB, Chaitman E, Schneider S: Portal-systemic

5. Howard ER, Stringer MD, Mowat AP: Assessment of injec- encephalopathy in the non-cirrhotic patient: Effect of portal-

tion sclerotherapy in the management of 152 children with oesoph- systemic shunting. Arch Surg 107:659-663, 1973

ageal varices. Br J Surg 75404-408, 1988 14. Alagille D, Corlier JC, Chiva M, et al: Long term neuropsy-

6. Lilly JR: Endoscopic sclerosis of esophageal varices in chil- chological outcome in children undergoing portal systemic shunts

dren. Surg Gynecol Obstet 52:513-514,198l for portal vein obstruction without liver disease. J Pediatr Gastro-

7. Paquet KJ: Ten year experience with paravariceal injection enter01 Nutr 5:861-866,1986

sclerotherapy of esophageal varices in children. J Pediatr Surg 15. van Stiegmann G: Advances in surgical technologies. Endo-

20:109-112,1985 scopic ligation of esophageal varices. Am J Surg 156:9A-12B, 1988

8. Hosking SW, Johnson AG: Gastric varices: A proposed 16. Spence RAJ, Johnston GW, Odling-Smee GW, et al: Bleed-

classification leading to management. Br J Surg 75:195-196,1988 ing oesophageal varices with long term follow-up. Arch Dis Child

9. Dogradi AE, Stempien SJ, Owens LK: Bleeding esophagogas- 59:336-340, 1984

You might also like

- FNCP CommunityDocument4 pagesFNCP CommunityWendy EscalanteNo ratings yet

- Byron Troya GarzonDocument6 pagesByron Troya GarzonByron TroyaNo ratings yet

- Primary Aortoduodenal Fistula Caused by Aortitis: SalmonellaDocument4 pagesPrimary Aortoduodenal Fistula Caused by Aortitis: SalmonellaGordana PuzovicNo ratings yet

- Perdarahan Varises GasterDocument8 pagesPerdarahan Varises Gastermandala22No ratings yet

- VVF RepairDocument4 pagesVVF RepairAdil KhurshidNo ratings yet

- Annsurg00231 0116Document9 pagesAnnsurg00231 0116Dodo MnsiNo ratings yet

- Acute Variceal HemorrhageDocument48 pagesAcute Variceal HemorrhagePRATAPSAGAR TIWARINo ratings yet

- Non Sirosis PHDocument11 pagesNon Sirosis PHHIstoryNo ratings yet

- Large and Bleeding Gastroduodenal Artery Aneurysm 2024 International JournalDocument5 pagesLarge and Bleeding Gastroduodenal Artery Aneurysm 2024 International JournalRonald QuezadaNo ratings yet

- Varices: Esophageal, Gastric, and RectalDocument18 pagesVarices: Esophageal, Gastric, and RectalHưng Nguyễn KiềuNo ratings yet

- Laparoscopic Distal Splenoadrenal ShuntDocument5 pagesLaparoscopic Distal Splenoadrenal ShuntRichard QiuNo ratings yet

- Kizza: Case ReportDocument3 pagesKizza: Case ReportRavindra Mani TiwariNo ratings yet

- ZZ - 1999-12 - Massive Intraperitoneal Hemorrhage From A Pancreatic PseudocystDocument4 pagesZZ - 1999-12 - Massive Intraperitoneal Hemorrhage From A Pancreatic PseudocystNawzad SulayvaniNo ratings yet

- Liver Transplantation - 2009 - Lim - Endoscopic Variceal Ligation For Primary Prophylaxis of Esophageal Variceal HemorrhageDocument6 pagesLiver Transplantation - 2009 - Lim - Endoscopic Variceal Ligation For Primary Prophylaxis of Esophageal Variceal Hemorrhagedarlington D. y ayimNo ratings yet

- Huang 1984Document4 pagesHuang 1984vinicius.alvarez3No ratings yet

- A Retrospective Clinical Study of Perforation Peritonitis in Rural Area in Andhra Pradesh November 2022 9921131660 120 PDFDocument9 pagesA Retrospective Clinical Study of Perforation Peritonitis in Rural Area in Andhra Pradesh November 2022 9921131660 120 PDFVijay KumarNo ratings yet

- Complicated AppendicitisDocument4 pagesComplicated AppendicitisMedardo ApoloNo ratings yet

- Order of PresentationDocument4 pagesOrder of PresentationSherwin SyNo ratings yet

- Jurnal Reading Abses HeparDocument5 pagesJurnal Reading Abses Heparika nur utamiNo ratings yet

- Oesophagocoloplasty For Corrosive Oesophageal Stricture: AbstractDocument12 pagesOesophagocoloplasty For Corrosive Oesophageal Stricture: AbstractSpandan KadamNo ratings yet

- Lesions Portal Gastritis Congestive Gastropathy?: Gastric in Hypertension: InflammatoryDocument7 pagesLesions Portal Gastritis Congestive Gastropathy?: Gastric in Hypertension: InflammatoryAnisa SafutriNo ratings yet

- GI Bleeding (Text)Document11 pagesGI Bleeding (Text)Hart ElettNo ratings yet

- Mrcs Upper GitDocument59 pagesMrcs Upper GitAdebisiNo ratings yet

- Abdomen: International Abstracts of Pediatric Surgery 593Document1 pageAbdomen: International Abstracts of Pediatric Surgery 593Yohanes WilliamNo ratings yet

- Raj KamalDocument5 pagesRaj KamalBhavani Rao ReddiNo ratings yet

- Yilmaz, 2006Document7 pagesYilmaz, 2006titaNo ratings yet

- Management of Gastric Variceal Hemorrhage: S K Sarin, Sanjay NegiDocument4 pagesManagement of Gastric Variceal Hemorrhage: S K Sarin, Sanjay NegiSa 'ng WijayaNo ratings yet

- Anil Degaonkar, Nikhil Bhamare, Mandar Tilak Arterio-Enteric Fistula A Case ReportDocument6 pagesAnil Degaonkar, Nikhil Bhamare, Mandar Tilak Arterio-Enteric Fistula A Case ReportDr. Krishna N. SharmaNo ratings yet

- Endoscopicmanagementof Portalhypertension-Related Bleeding: Andrew Nett,, Kenneth F. BinmoellerDocument17 pagesEndoscopicmanagementof Portalhypertension-Related Bleeding: Andrew Nett,, Kenneth F. BinmoellerAlonso CayaniNo ratings yet

- Bet 4 051Document3 pagesBet 4 051myway999No ratings yet

- Uppergastrointestinalbleeding: Marcie Feinman,, Elliott R. HautDocument11 pagesUppergastrointestinalbleeding: Marcie Feinman,, Elliott R. HautjoseNo ratings yet

- J Epsc 2015 05 012Document4 pagesJ Epsc 2015 05 012Hanung PujanggaNo ratings yet

- Jurnal Hernia UmbicalDocument3 pagesJurnal Hernia UmbicaltutiNo ratings yet

- Hemosuccus Pancreaticus: A Mysterious Cause of Gastrointestinal BleedingDocument6 pagesHemosuccus Pancreaticus: A Mysterious Cause of Gastrointestinal BleedingSINAN SHAWKATNo ratings yet

- Acute Abdomen in Chronic Renal Failure: A. Martinez-Vea, J. Montoliu, C. Monroy, M.Lanuza, J.Lopez Pedret, L. RevertDocument2 pagesAcute Abdomen in Chronic Renal Failure: A. Martinez-Vea, J. Montoliu, C. Monroy, M.Lanuza, J.Lopez Pedret, L. RevertbagussofianNo ratings yet

- Anil Degaonkar, Nikhil Bhamare, Mandar Tilak Arterio-Enteric Fistula A Case ReportDocument6 pagesAnil Degaonkar, Nikhil Bhamare, Mandar Tilak Arterio-Enteric Fistula A Case ReportDr. Krishna N. SharmaNo ratings yet

- General Surgery: Ruptured Liver Abscess: A Novel Surgical TechniqueDocument3 pagesGeneral Surgery: Ruptured Liver Abscess: A Novel Surgical TechniqueRahul SinghNo ratings yet

- The Causes of Upper Gastrointestinal Bleeding in The National Referral Hospital: Evaluation On Upper Gastrointestinal Tract Endoscopic Result in Five Years PeriodDocument4 pagesThe Causes of Upper Gastrointestinal Bleeding in The National Referral Hospital: Evaluation On Upper Gastrointestinal Tract Endoscopic Result in Five Years PeriodSyawal PratamaNo ratings yet

- ZZ - 2016-12 - Splenic Artery Pseudoaneurysm Rupture Into A Pancreatic Pseudocyst With Its Subsequent Perforation As The Cause of A Massive Intra-Abdominal Bleeding - Case ReportDocument6 pagesZZ - 2016-12 - Splenic Artery Pseudoaneurysm Rupture Into A Pancreatic Pseudocyst With Its Subsequent Perforation As The Cause of A Massive Intra-Abdominal Bleeding - Case ReportNawzad SulayvaniNo ratings yet

- Diagnosis of Gastrointestinal Bleeding in AdultsDocument8 pagesDiagnosis of Gastrointestinal Bleeding in AdultsSaeed Al-YafeiNo ratings yet

- 6665 PDFDocument4 pages6665 PDFerindah puspowatiNo ratings yet

- Left SidedDocument3 pagesLeft SidedElisabeth ZzMick GtNo ratings yet

- Soleimani 2007Document9 pagesSoleimani 2007ceciliaNo ratings yet

- Lane1999 PDFDocument6 pagesLane1999 PDFkatsuiaNo ratings yet

- A Giant Gastrointestinal Stromal Tumor Revealed by A L - 2024 - International JoDocument5 pagesA Giant Gastrointestinal Stromal Tumor Revealed by A L - 2024 - International JoRonald QuezadaNo ratings yet

- Varices: Esophageal, Gastric, and RectalDocument18 pagesVarices: Esophageal, Gastric, and Rectallourdes marquezNo ratings yet

- Perbaikan AnastomosisDocument6 pagesPerbaikan AnastomosisReagen DeNo ratings yet

- International Wound Journal - 2016 - Bobkiewicz - Management of Enteroatmospheric Fistula With Negative Pressure WoundDocument10 pagesInternational Wound Journal - 2016 - Bobkiewicz - Management of Enteroatmospheric Fistula With Negative Pressure WoundDiana Carolina RochaNo ratings yet

- Introduction of Case Study BristyDocument11 pagesIntroduction of Case Study BristyJoy Chakraborty RoniNo ratings yet

- 5 Case Study Flood SyndromeDocument2 pages5 Case Study Flood SyndromeMenche DapulagNo ratings yet

- Acosta 2003Document5 pagesAcosta 2003Mihaela MocanNo ratings yet

- Acute GIDocument8 pagesAcute GIFerry SahraNo ratings yet

- Treatment Antacid: of Hemorrhagic GastritisDocument5 pagesTreatment Antacid: of Hemorrhagic GastritisIsabella Martins AndersenNo ratings yet

- Primary Aortoenteric FistulaDocument5 pagesPrimary Aortoenteric FistulaKintrili AthinaNo ratings yet

- Rheumatology Journal Club Gut Vasculitis: by DR Nur Hidayati Mohd SharifDocument36 pagesRheumatology Journal Club Gut Vasculitis: by DR Nur Hidayati Mohd SharifEida MohdNo ratings yet

- Hepatology - July 1995 - D'amico - The Treatment of Portal Hypertension A Meta Analytic ReviewDocument23 pagesHepatology - July 1995 - D'amico - The Treatment of Portal Hypertension A Meta Analytic ReviewDiah SafitriNo ratings yet

- Journal of Pediatric SurgeryDocument6 pagesJournal of Pediatric SurgeryEkaNo ratings yet

- TMP CD3Document4 pagesTMP CD3FrontiersNo ratings yet

- Case 2Document4 pagesCase 2Malavika RaoNo ratings yet

- Damage Control in Trauma Care: An Evolving Comprehensive Team ApproachFrom EverandDamage Control in Trauma Care: An Evolving Comprehensive Team ApproachJuan DuchesneNo ratings yet

- Beyond the Aorta: Exploring the Depths of Abdominal Aortic AneurysmFrom EverandBeyond the Aorta: Exploring the Depths of Abdominal Aortic AneurysmNo ratings yet

- A New Automated Method For The Determination of Erythrocyte Sedimentation Rate (ESR)Document7 pagesA New Automated Method For The Determination of Erythrocyte Sedimentation Rate (ESR)RaffaharianggaraNo ratings yet

- Second Periodical Test in HealthDocument2 pagesSecond Periodical Test in HealthKate BatacNo ratings yet

- List of The Hospital Empanelled With DDA (June 2021)Document24 pagesList of The Hospital Empanelled With DDA (June 2021)ygkrchNo ratings yet

- Summative Test Mapeh 6Document4 pagesSummative Test Mapeh 6Roldan SarenNo ratings yet

- WEEK 7 Clinical Microscopy - UrinalysisDocument11 pagesWEEK 7 Clinical Microscopy - Urinalysisioperez1868qcNo ratings yet

- Ass SciDocument87 pagesAss ScigheinbaNo ratings yet

- Miriam Hospital Code PosterDocument1 pageMiriam Hospital Code PosterLucas TobingNo ratings yet

- AluminaDocument3 pagesAluminaG AnshuNo ratings yet

- Spinal Cord InjuriesDocument17 pagesSpinal Cord InjuriesspinalcordNo ratings yet

- JASMIN, Kisha Jane P.Document2 pagesJASMIN, Kisha Jane P.Kisha Jane JasminNo ratings yet

- Antidiabetic Molecular DockingDocument19 pagesAntidiabetic Molecular DockingChristianAvelinoNo ratings yet

- Healthmeans 20 Ways To Beat FatigueDocument20 pagesHealthmeans 20 Ways To Beat Fatiguesandrashalom2No ratings yet

- AlbuminDocument16 pagesAlbuminMaroofAliNo ratings yet

- Digestive SystemDocument58 pagesDigestive SystemseibdNo ratings yet

- Rat-Park-acceptedman Bruce K. AlexanderDocument9 pagesRat-Park-acceptedman Bruce K. AlexanderLevente BalázsNo ratings yet

- Denka Letter To EPADocument108 pagesDenka Letter To EPAThe GuardianNo ratings yet

- CHNDocument5 pagesCHNAnnaAlfonsoNo ratings yet

- American EskimosDocument21 pagesAmerican EskimosJorie RocoNo ratings yet

- Autism and Adhd 1,222Document4 pagesAutism and Adhd 1,222NJ BesanaNo ratings yet

- Bio Ijso PDFDocument15 pagesBio Ijso PDFSidNo ratings yet

- 39207618Document6 pages39207618api-301074100% (1)

- General Studies (Paper-I) Full Length Test (FLT) - 7: Time Allowed: 2 Hours Maximum Marks: 200 InstructionsDocument20 pagesGeneral Studies (Paper-I) Full Length Test (FLT) - 7: Time Allowed: 2 Hours Maximum Marks: 200 InstructionsSweety SriramaNo ratings yet

- Tropical Haematology and Blood Transfusion PDFDocument77 pagesTropical Haematology and Blood Transfusion PDFZiauddin AzimiNo ratings yet

- Frank E. Berkowitz-Case Studies in Pediatric Infectious Diseases (2007)Document399 pagesFrank E. Berkowitz-Case Studies in Pediatric Infectious Diseases (2007)moldovanka88_6023271100% (3)

- Literature On DFS Technology and Pure ElectronicDocument62 pagesLiterature On DFS Technology and Pure ElectronicEdson BastoNo ratings yet

- Natural History of Cervical CancerDocument27 pagesNatural History of Cervical CancerAri AsriniNo ratings yet

- The New Rome IV CriteriaDocument13 pagesThe New Rome IV CriteriaM Marliando Satria PangestuNo ratings yet