Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Geller1996 PDF

Geller1996 PDF

Uploaded by

Angela EnacheOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Geller1996 PDF

Geller1996 PDF

Uploaded by

Angela EnacheCopyright:

Available Formats

Comorbidity of Juvenile Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder

with Disruptive Behavior Disorders

DANI EL A. GELLER, M.B.B.S., JOSEPH BIEDERMAN , M.D., SUSAN GRIFFIN, B.A., JAN ICE JONES, B.A.,

AND TODD R. LEFKOWITZ, B.A.

ABSTRACT

Objective: To examine the full spectrum of psychiatric comorbidity in juvenile obsessive-compuls ive disorder (OCD)

in a naturalistic manner when no exclusionary criteria are used for sample selection. Method: Consecutive referrals to

a specialized pediatric OCD clinic were evaluated by means of structured diagnostic interviews and rating scales. No

exclusionary criteria were used for sample selection. Findings were compared with those of previously published reports

of juvenile OCD. Results: Compared with previous studies, our sample of juveniles with OCD had high rates of

comorbidity not only with tic, mood, and anxiety disorders but also with disruptive behavior disorders. Conclusions:

Our findings indicate that in the naturalistic setting, juvenile OCD is heavily comorbid with both internalizing and

externalizing disorders. The presence of such a complex comorbid state has important clinical and research implications

and stresses the relevance of limiting exclusionary criteria in studles of juvenile OCD. J. Am. Acad. Child Ado/esc.

Psychiatry, 1996, 35 (12 ):1637-1646. Key Words: obsessive-compulsive disorder, comorbidity, pediatric samples,

disruptive behavior.

In contra st to a body of literature on patterns of Although these studies provided useful clinical infor-

psychiatric comorbidity in clinical samples of adults mation regarding patterns of comorbid ity in juvenile

with obsessive-compulsive disorder (O CD) (Karno O CD, their generalizability is limited because of the

et al., 1988; Rasmussen and Eisen, 1992a,b; Weissman numerous exclusiona ry criteria used. For example ,

et al., 1994), a more limited body of literature exists Swedo et al. (1989) excluded subjects with a concurrent

on this subject in pediatric samples. Several previously diagnosis ofTS, schizophr enia, " primary major depres-

publ ished studies (Hanna, 1995; Last and Strauss, sion," organic mental disorder , or mental retardation.

1989; Riddle et al., 1990; Swedo et al., 1989; Toro This was based in part on their desire to have a

et al., 1992) have reported on psychiatric comorbidity homogeneous group for a pharmacological treatment

in clinically referred juvenile samples. These studies trial. Riddle et al. (1990) excluded almost half of the

reported that, as in adults, children and adolescents subjects from data analysis because of subthreshold

with OCD frequently have high levels of comorbidiry symptoms, a diagnosis of trichotillomania but not

with major depression, other anxiety disorders, and OCD, T S, prior major depression, or psychosis. Also

Tourette's syndrome (T S). excluded were subjects with anorexia nervosa, a " pri-

mary phobic disorder," or pervasive developmental

disorder. Hanna (1995) excluded patients with primary

Accepted April 2, 1996.

major depression, bipolar disorder, psychosis, and an-

From the Pediatric Psychopharmacology Unit , Mcl.ean Hospital, Belmont,

U4 (D rs. Geller and Biederman, Ms. j ones, and M r. Lefkowitz); the Pediatric orexia nervosa; some of his sample were also enrolled

Psychopharmacology Unit, Massachusetts Genera/ Hospital. Boston (D rs. Geller in a clomipramine treatm ent study.

and Biederman. M s. Griffin , M s. j ones, and Mr. Lefkowitz); and the Depart-

The complication of using numerous exclusionary

ment of Psychiatry, H a rva rd M edical School, Boston (D rs. Geller and

Biederman). criteria in previous studies aimed at understanding

Reprint requests to Dr. Geller, joint Program in Pediatric Psychopharmacol- patterns of comorbidity in juvenile OCD is that the

ogy, Mc l.ean Hosp ital, 115 Mill Street, Belmont, U4 02 178; telephone: (617) information provided may not represent the true scope

855-2846; fax : (617) 855-3 722.

0890-8567/96/3512- 1637$03.00/0 ©1996 by the American Academy of comorb idity in clinical samples, since clinicians are

of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. asked to evaluate and treat OCD children without

j . AM . ACA D . CHILD ADOLE SC . PSYCH IATRY, 35:12, DECEMBE R 19 96 1637

GELLER ET AL.

exclusionary rules. For example, although the previous and adolescents with OCD without exclusionary crite-

studies (Last and Strauss, 1989; Riddle et al., 1990; ria. To this end we systematically evaluated the presence

Swedo et al., 1989; Toro et al., 1992) found relatively of comorbid psychiatric disorders in an entire clinical

low rates of comorbid disruptive behavior disorders program dedicated to the assessment and treatment of

among juveniles with OCD, much higher rates appear children and adolescents with OCD and compared

to be common in clinical practice. The low rate of them with findings from the several previously reported

comorbid disruptive behavior disorders in prior studies studies (Hanna, 1995; Last and Strauss, 1989; Riddle

of children with OCD is particularly surprising consid- et al., 1990; Swedo et al., 1989; Toro et al., 1992)

ering that TS (Singer and Walkup, 1991), juvenile on juvenile OCD. We hypothesized that the comor-

major depression (Biederman et al., 1987, 1992), and bidity with disruptive behavior disorders in children

juvenile anxiety disorders (Biederman et al., 1991a,b, and adolescents with OCD would be higher than

1994) are frequently comorbid with disruptive behavior expected by chance (population rates) and higher than

disorders, suggesting that disruptive disorders may be noted in earlier reports.

more prevalent in samples of juveniles with OCD than

previously reported. Thus, there is a need to reevaluate METHOD

patterns of psychiatric comorbidity in juveniles with This was a systematic record review of all subjects aged 18 years

OCD in a more naturalistic manner to secure the and younger referred since 1993 to a specialized outpatient program

for children and adolescents with OCD under the direction of the

ecological validity of findings.

senior author (D.A.G.) for whom complete records were available.

A comprehensive assessment of the full scope of This program offers comprehensive diagnostic evaluation and treat-

psychiatric comorbidity has major therapeutic, research, ment for pediatric subjects with OCD and their families provided

by a specialized multidisciplinary team consisting of a social worker,

and public health implications. From a clinical perspec-

a child and adolescent psychiatrist and psychopharmacologist

tive, comorbid conditions may require a treatment (D.A.G.), and cognitive and behavioral therapists, and it includes

approach that is different from that used in noncomor- regular support group lectures and meetings. To be included in

this record review study, subjects had to fully satisfy DSM-III-R

bid cases. For example, consideration of the high risk

diagnostic criteria (American Psychiatric Association, 1987) for

for added disability and morbidity associated with OCD based on clinical assessment and confirmed on a structured

concomitant disruptive behavior disorders in children diagnostic interview (Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizo-

phrenia for School-Age Children-Epidemiologic version) (K-SADS-

and adolescents with OCD may permit clinicians to

E) (Orvaschel, 1985) administered by trained raters under the

improve the treatment outcome of complex OCD supervision of the service director (J.B.). The K-SADS-E is a

cases. The current enthusiasm for the application of widely used, semistructured, DSM-lII-R-based psychiatric diagnos-

tic interview with established psychometric properties. It was de-

behavioral techniques in the treatment of children and

signed for use in clinical and epidemiological research to obtain a

adolescents with OCD should also take into account past and current history of psychiatric disorders in children and

the presence of any concurrent disruptive behavioral adolescents aged 6 to 17 years. It can be effectively administered

disorders. Pharmacological approaches and responses by clinicians or trained interviewers in 60 to 90 minutes. It provides

a standardized method of obtaining and recording symptoms

for these different diagnostic conditions may be rela- necessary for the assessment of most Axis I DSM-III-R categories.

tively specific, with little therapeutic overlap. From a This study received approval by the Institutional Review Board.

research perspective, the presence of comorbid condi- In addition to diagnostic assessments, we used the DSM-lII-R

Global Assessment of Functioning (GAF) scale (American Psychiat-

tions may help decrease the heterogeneity of psychiatric ric Association, 1987) (l = worst to 90 = best) to assess overall

disorders by identifying more homogeneous subgroups psychosocial functioning. Severiry and type of obsessive and com-

based on cornorbidiry: this in turn permits evaluation pulsive symptoms were rated by the senior author (D.A.G.), using

the Children's Yale-Brown Obsessive Compulsive Scale (CY-

of whether correlates of specific disorders are due to BOCS) (an unpublished instrument). The CY-BOCS, the children's

the disorder of interest, its cornorbidity, or both. From version of the Yale-Brown Obsessive Compulsive Scale (Y-BOCS)

a public health perspective, subjects with high levels (Goodman et al., 1989a, b: Hardin et al., 1991; Riddle et al.,

1993), is a clinician-rated 10-item scale, with each item rated on

of comorbidity may be at greater risk for the develop- a 4-point scale (0 = "no symptoms" to 4 = "extreme symptoms")

ment of more severe dysfunction over time than non- (total range = 0 through 40), with subtotals for obsessions (irems

1 through 5) and compulsions (items 6 through 10). The CY-

comorbid subjects.

BOCS includes a Symptom Checklist of more than 60 examples of

The purpose of this report is to reexamine patterns obsessions and compulsions organized into several larger categories

of psychiatric comorbidity in clinically referred children according to their rhematic content (for example, hoarding or

1638 j. AM. ACAD. CHILD ADOLESC. PSYCHIATRY, 35:12, DECEMBER 1996

DISRUPTIVE BEHAVIOR IN JUVENILE OeD

contamination). Family history of psychopathology in first-degree Analysis of OCD characteristics revealed that more

relatives was obtained at the time of the clinical interview by the

than one third of our sample had poor or no insight

senior author (D.A.G.) by reviewing information provided by the

family at the time of assessment. into the nature of their OCD symptoms, which were

Findings from our sample were compared with those from not reported to be ego-dystonic despite the marked

previous studies reported in the literature (Hanna, 1995; Last and impairment they caused. The number of subjects with

Strauss, 1989; Riddle et al., 1990; Swedo et al., 1989; Toro et aI.,

1992). Swedo et al. (1989) reported on the clinical phenomenology only compulsions (n = 3, 10%) or only obsessions (n =

of 70 consecutively referred children and adolescents seen at the 1, 3%) was quite low, while the large majority of

National Institute of Mental Health who were included in a subjects in our study had both multiple compulsions

clomipramine treatment trial. Assessments included the Diagnostic

Interview for Children and Adolescents (DICA) (Welner et aI.,

and multiple obsessions. The most frequently reported

1987). Riddle et al. (1990), using a standard clinical psychiatric obsessions were those of violent and/or catastrophic

assessment, the Child Behavior Checklist (CBCL) (Achenbach, events, often involving a loved one (60%), followed by

1978; Achenbach and Edelbrock, 1983), and the Yale OCD

those of contamination (53%). Common compulsions

Questionnaire (an unpublished instrument), reported on the phe-

nomenology of 21 clinically referred children and adolescents. included repeating (73%), washing and cleaning (57%),

Structured clinical interviews were not included as part of this checking (43%), and ordering/arranging (40%) rituals.

assessment. Hanna (1995) reported on a clinically referred sample The mean total CY-BOCS score in the 23 subjects

of 31 pediatric OCD patients and described their comorbidity by

using the DICA as well as their demography and symptomatology. with available information was 23, placing the severity

Last and Strauss (1989) identified 20 children and adolescents of OCD symptoms in the moderately severe range.

with OCD from among 190 consecutive referrals to an anxiety Similarly impaired were scores on the DSM-III-R GAF

disorder clinic and assessed rhem and their families for lifetime

psychopathology, using structured interviews (Schedule for Affective

scale; the average (±SD) score was 43 (±8), placing

Disorders and Schizophrenia for School-Age Children-Present Epi- subjects in the severe impairment range. Measures of

sode version [Puig-Antich and Chambers, 1978]). Toro et al. school functioning showed similarly high levels of

(1992) selected and reviewed the clinical records of all cases with

impairment in that 48% of our subjects had received

a diagnosis of OCD from among thousands of patients who had

attended either a hospital or a private clinic in Barcelona over a remedial help, 40% were placed in a special class, and

10-year period. Demographic information, sample ascertainment, 7% had repeated a grade. All of our patients had

exclusion criteria, type and severity of presenting obsessive-compul- received some type of treatment prior to assessment

sive symptoms, comorbid diagnoses, and family history of OCD

were compared between these reports and our sample. in our clinic; 87% had been medicated for their OCD

Because distributions between samples were likely to be different and 37% had required inpatient psychiatric care.

from each other and from nonclinical samples due to ascertainment Comorbid psychopathology was almost universal in

biases, continuous data regarding demographic variables between

groups were not analyzed. Because of such biases, formal statistical

our sample, with only one subject failing to meet

comparisons of rates of presenting symptoms and comorbid diagno- criteria for at least one additional psychiatric diagnosis

ses were deemed invalid and were also not performed. Categorical other than OCD (Fig. 1). Seventy-three percent of

data (gender and intact family) were analyzed using X2 tests as

our subjects had major depression, with 27% also

indicated. All tests were two-tailed and statistical significance was

defined at the 1% level (p < .01). meeting DSM-III-R criteria for mania. Of the entire

sample, 16 (53%) subjects had a diagnosis of at least

RESULTS

100

McLean OCD Sample

The subject pool in this study consisted of 30

consecutively referred subjects who satisfied DSM-III-R %

diagnostic criteria for OCD based on clinical assessment

and confirmed by structured diagnostic interview. The

mean (±SD) age of this group was 12.6 (±2.9) years

and the mean (±SD) age of onset of OCD was 8.5 N=l

(±4.0) years. Seventy percent of the subjects were Mood Disrnptlve Multiple TIcs & Psychosis No Other

Disorders Behavior Anxiety Tourette's Diagnosis

male. The mean socioeconomic status (Hollingshead, Disorders Disorder

1965) was 1.8 (±0.8), and 23 subjects (79%) came Fig.1 Frequency of comorbid diagnoses in pediatric obsessive-compulsive

from intact families. No exclusion criteria were used. disorder patients (N = 30).

j, AM. ACAD. CHILD ADOLESC. PSYCHIATRY, 35:12, DECEMBER 1996 1639

GELLER ET AL.

one disruptive behavior disorder, making disruptive (57%), anxiety disorders (39%), ADHD (32%), OCD

behavior disorders the second most common comorbid (23%), substance use disorders (17%), and chronic tic

condition; 33% had attention-deficit hyperactivity dis- disorders (11%) as the most prevalent conditions. Three

order (ADHD), 43% oppositional defiant disorder, probands (11 %) had a first-degree relative with a history

and 7% conduct disorder. In addition, 43% had multi- of psychiatric hospitalization. Comparisons with respect

ple (two or more) anxiety disorders, 34% had chronic to family psychiatric history with other studies could

tics or TS, 30% had psychosis, 27% had a develop- not be made because of insufficient information

mental speech or language disorder, and 37% had provided.

enuresis.

An analysis of patterns of comorbidity in juvenile Comparison with Previous Studies

OCD subjects with and without comorbid TS found

There was a variable rate of positive family history

higher rates of separation anxiety, simple phobia, and

of OCD in first-degree relatives of young pro bands

encopresis (p S .01) in those with TS. However, when

with OCD, ranging from 8% to 24%; this was assessed

analyses were extended to the presence of non-TS tic

by structured interviews (Last and Strauss, 1989; Swedo

disorders, there were no significant findings. A further

et al., 1989), clinical interview (Riddle et al., 1990;

analysis of OCD subjects found significantly higher

this study), and clinical record review (Toro et al.,

rates of bipolar disorder, developmental speech and

1992) (Table 1).

language (but not learning) disorder, and enuresis (p

Most studies reported that multiple obsessions and

S .01) in subjects with comorbid ADHD. Our data

multiple compulsions are the most common OCD

do not allow us to distinguish between ADD with

presentation in juveniles (Table 2). In our series, we

and without hyperactivity because we used DSM-III-R

found a higher frequency of sexual obsessions and a

criteria, which do not separate the two conditions for

lower rate of somatic obsessions compared with previ-

diagnostic purposes.

The mean age of onset of comorbid conditions (Fig. ous reports. Hanna (1995) reported higher rates of

2) showed a developmental progression with disruptive contamination obsessions and Toro et al. (1992) re-

behavior (ADHD = 1.8 years; ODD = 7.1 years) ported lower rates of aggressive and religious obsessions

beginning much earlier than the onset of OCD (8.5 compared with other studies. Swedo et al. (1989)

years) and major depression (9.1 years). reported lower rates of ordering/arranging and a higher

Family psychiatric history obtained by clinical inter- rate of washing compulsions than was found in our

view at the time of referral and evaluation of juvenile sample. Last and Strauss (1989) reported very low rates

OCD probands showed high rates of Axis I psychopa- of repeating and hoarding compulsions compared with

thology in first-degree relatives, with mood disorders other studies (Table 2). In contrast, we found no

differences in rates of several other common obsessions

(hoarding) and compulsions (checking and counting)

12

N=9 compared with other studies. The relatively common

finding in our sample of poor insight could not be

directly compared with previous studies because its

absence precluded entry into one of the studies (Swedo

Age

et al., 1989) and the others (Hanna, 1995; Last and

Strauss, 1989; Riddle et al., 1990; Toro et al., 1992)

did not report on this issue.

The only other study to report on the mean CY-

BOCS scores (Hanna, 1995) showed no significant

ADHD 1'5 Mult Anx ODD om Conduct Tics MOD Bipolar Psycbosls difference with findings reported in our sample. Other

Fig. 2 Mean age of onset of comorbid psychiatric disorders among measures of impairment such as the GAF scale (Ameri-

pediatric OCD patients (N = 30). ADHD = attention-deficit hyperactivity can Psychiatric Association, 1987) did not lend them-

disorder; TS = Tourettc's syndrome; Mulr Anx = multiple anxiety disorder;

ODD = oppositional defiant disorder; OCD = obsessive-compulsive disor- selves for comparison with the previous studies because

der; MOD = major depressive disorder. of insufficient information.

1640 ]. AM. ACAD. CHILD ADOLESC. PSYCHIATRY, 35:12, DECEMBER 1996

DISRUPTIVE BEHAVIOR IN JUVENILE ocn

TABLE 1

Clinical Characteristics of Samples of Pediatric OCD

Swedo et al. Riddle et al. Hanna Last & Strauss Toro et al. This Study

(N = 70) (N = 21) (N = 31) (N = 20) (N = 72) (N= 30)

Sample Recruited for Clinic referrals Clinic referrals; Anxiety clinic Clinic tecord Clinic referrals

ascertainment clinical drug clinical drug teferrals review

trial trial

Exclusion Major depression; Phobia; Major depression; None reported Organic mental None

criteria Touretre's, Tourerte's: bipolar; disorder; IQ

psychosis psychosis; PDD psychosis; <70

anorexia nervosa

Assessment DICA Clinical DICA K-SADS-P Clinical K-SADS-E

Demographics Mean SD Mean SD Mean SD Mean SD Mean SD Mean SD

Age 13.7 2.7 12.2 3.1 13.5 2.8 12.7 3.2 12 3.3 12.6 2.9

Age of onset 10.1 3.5 9.0 2.9 10.0 3.0 10.7 NR II 2.9 8.5 4.0

SES NR 1.9 1.1 2.2 I.2 3.2 1.1 NC 1.8 0.8

No. % No. % No. % No. % No. % No. %

Males* 47 67 9 43 19 61 12 60 47 65 21 70

Intact

families* NR 16 76 27 87 NR 65 90 23 79

Family history

of OCDa 17 24 4 19 NR 3 8 II 15 7 23

Assessment

source SADS-L/DICA Clinical interview NA SCID/K-SADS-P Record review Clinical interview

Note: OCD = obsessive-compulsive disorder; PDD = pervasive developmental disorder; DICA = Diagnostic Interview for Children and

Adolescents; K-SADS-P and K-SADS-E = Schedule for Mfective Disorders and Schizophrenia for School-Age Children, Present Episode

and Epidemiologic versions; SES = socioeconomic status; NR = not reported; NC = not comparable (reported as "low = 50%, medium =

33%, high = 17%, by father's education"); NA = not applicable; SADS-L = Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia-Lifetime

version; SCID = Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IIJ-R.

a First-degree relatives.

* p < .01 by overall X2•

Rates of comorbid psychiatric diagnoses could not DISCUSSION

often be directly compared because of the numerous

In a systematic reevaluation of patterns of psychiatric

exclusion criteria used in the previous studies (Table

comorbidity in consecutively referred juveniles with

1). Even when data are available, sample ascertainment OCD, we found high levels of comorbidity not only

biases preclude valid statistical comparisons between with TS, mood, and anxiety disorders previously iden-

groups. Subjects with severe or primary major depres- tified in these subjects, but also with disruptive behavior

sion, mania, panic, psychosis, and TS were not included disorders as well. These findings confirm our study

in many of the previous reports, yet these disorders were hypothesis and document that disruptive behavior dis-

commonly found in our subjects (Table 3). Among orders may be more prevalent in clinical practice than

disorders that were assessedin most studies, higher rates previously reported in samples of pediatric OCD

of separation anxiery disorder, ADHD, oppositional patients.

defiant disorder, and enuresis were identified in our The age at referral, age at onset of OCD, gender

subjects compared with the those of previous reports distribution, family history of OCD, and nature of

(Table 3). In contrast, few differences were found presenting OCD symptoms as well as comorbidity

in rates of dysthymia, social phobia, simple phobia, with mood and anxiety disorders are highly consistent

overanxious disorder, conduct disorder, tic disorders, with previous studies ofjuvenile OCD. The consistency

and developmental speech and language disorders. of findings in our sample compared with those of

j, AM. ACAD. CHILD ADOLESC. PSYCHIATRY, 35:12, DECEMBER 1996 1641

GELLER ET AL.

TABLE 2

Phenomenology and Severity of Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder in Pediarric Parients

Swedo er al. Riddle et al. Hanna Last & Strauss Toro et al. This Study

(N= 70) (N = 21) (N = 31) (N = 20) (N = 72) (N = 30)

Presentation % % % % % %

Poor or no insight oa NR NR NR NR 37

Compulsions only NR 10 0 NR NR 10

Single obsession At onset NR 3 NR NR 30

Multiple obsessions Frequent 90 97 NR NR 60

Obsessions only NR NR 0 20 NR 3

Single compulsion At onset NR 0 40 NR 10

Multiple compulsions Frequent 90 100 40 NR 87

Obsessions

Contamination 40 52 87 NR NR 53

Aggressive/catastrophe 28 38 81 NR 13 60

Sexual 4 14 26 NR 6 27

Religious 13 29 23 NR 4 23

Hoarding 11 10 36 NR NR 17

Somatic NR 38 10 NR NR 3

Miscellaneous 10 NR 55 NR 11 23

Compulsions

Repeating 51 76 64 5 74 73

Washing/cleaning 85 67 84 40 56 57

Checking 46 57 64 20 51 43

Ordering/arranging 17 62 61 30 42 40

Counting 18 24 42 20 NR 30

Hoarding 11 10 42 5 3 20

Miscellaneous 26 NR 39 NR NR 53

Severity Mean Mean Mean Mean Mean Mean b

CY-BOCS

Obsessions NR NR NR NR NR 11.8

Compulsions NR NR NR NR NR 11.5

Total NR NR 24.4 NRc NR 23

GAP NR NR NR NR NR 43.1

Note: CY-BOCS = Children's Yale-Brown Obsessive Compulsive Scale; GAP = Global Assessment of Functioning; NR = not reported.

aRituals or thoughts "deemed unreasonable" by patient.

b N = 23 for CY-BOCS.

c Fifty percent or more rated as "severe or very severe."

previous studies indicates that our subjects were not of juveniles treated with fluoxetine for OCD (Geller

atypical but rather representative of clinically referred et al., 1995). This overrepresentation ofADHD among

juveniles with OCD. juveniles with OCD is also consistent with findings

Despite these common characteristics with previous reported by Hanna (1995) of a 16% rate of ADHD

studies, we found a rate of comorbidity with disruptive in his sample of children with OCD.

behavior disorders that was much higher than in most In contrast, the majority of previous studies of

previously reported studies. Moreover, when present, juvenile OCD failed to identify an excess of disruptive

disruptive behavior disorders developed years before behavior disorders. While the numerous exclusionary

the onset of OCD, suggesting that the finding of criteria used by previous investigators (Hanna, 1995;

disruptive behavior in our sample is not an artifact of Last and Strauss, 1989; Riddle et al., 1990; Swedo

diagnosis of OCD but instead may represent a genuine et al., 1989; Toro et al., 1992) may be understood in

clinical observation. The excess of disruptive behavior light of their desire to collect relatively homogeneous

disorders in this sample of referred juveniles with OCD patients unencumbered by other diagnoses at a time

is consistent with our own recent report of a 32% when the clinical entity of juvenile OCD was less

overlap between OCD and ADHD in a separate sample clearly recognized, these exclusions could nevertheless

1642 J. AM. ACAD. CHILD ADOLESC. PSYCHIATRY, 35:12, DECEMBER 1996

DISRU PTIVE BE HAVIOR I N JUVEN ILE OCD

TABLE 3

Comorbid Psychiat ric D iagnoses in Pediatric O bsessive-Compu lsive D isorder Pat ients

Swedo et al. Riddle et al. H anna Last & Strauss Toro et al. T his Study

(N = 7 0)a (N = 2W (N = 3 1)a (N= 2W (N = 72)a (N=3W

No. % No . % No . % No . % No . % No. %

Mood disorders

Major depression" 23 33 2 10 4 13 NR 16 22 22 73

Dysthymia NR 4 19 3 10 NR 11 15 2 7

Man ia" NR NR Excluded NR NR 8 27

Any mood disorder" NR 6 29 10 32 4 20 27 38 22 73

Anxiety disorders

Panic NR NR NR NR NR 8 28

Agoraphobia NR Exclud ed NR NR NR 7 23

Social phobia NR Excluded NR 4 20 NR 3 10

Simp le phobia" 12 17 Excluded 2 6 7 35 7 10 5 17

Overanxious 11 16 5 24 4 13 5 25 20 28 11 38

Separation anxiety 5 7 5 24 2 6 4 20 3 4 10 33

Multiple anxiety disorder NR NR NR NR NR 13 43

Any anxiety disorder" NR 8 38 8 26 14 70 30 42 21 70

Disruptive behavio r disorders

ADHD 7 10 2 10 5 16 NR 4 6 10 33

Conduct disorder 5 7 NR 1 3 NR 0 0 2 7

ODD 8 11 NR 5 16 NR 2 3 13 43

Any disruptive behavio r NR NR 9 29 NR NR 16 53

Tic disorde rs

Tourerre's b Excluded Excluded 4 13 NR 11 15 3 11

Chronic tics NR NR NR NR NR 7 23

Any tics 14 20 5 24 8 26 NR 12 17 12 40

O ther

Psychosis" Excluded Excluded Exclude d NR 1 9 30

PDDb NR Excluded 1 3 NR NR 2 7

Development al S/L 17 24 3 14 7 23 NR NR 8 27

Enuresislenco presis 5 7 NR 2 6 NR 11 15 11 37

Mental retardation NR Excluded NR NR Excluded 2 7

No orher disorder" 18 26 8 38 5 16 4 20 16 27 1 3

Note: ADHD = atte ntion-deficit hyperactivity diso rder; O D D = oppositional defiant disorder; PDD = pervasive developmental disorder;

S/L = speechlla nguage disorder; NR = not reported .

a Ca tegories are nor mutually exclusive.

b Exclusion criteria used; see T able 1.

have led to an und erestimation of ADH D in their because this issue has not been systematically investi-

O CD subjects. In addition, the Riddle et al. (1990) gated in samples of adults with OCD . Adult O CD

and Toro et a!' (1992) studies did not use structured patients are typically not screened for the presence of

diagnostic interviews, which may also have led to ADHD because, for the most part, structu red diagnos-

underdiagnosis of these disorders. Last and Strauss tic interviews lack modules for this disorder and its

(1989) used structured diagnostic interviews but did occurrence in adults is still a matter of debate in some

not report at all on the presence of AD H D or other circles. Because comorbidity with AD H D has been

disruptive behavior disorders in their sample of 20 linked to early-onset mood (Biederman et a!', 1995a)

pediatric O CD subjects, making it difficult to know and panic disorder (Biederman et al., 1995b), it could

whether disruptive behavior disorders were not found represent a marker for a developmental subtype of early-

or not assessed. onset OCD. An analysis of patterns of comorbidity in

Whether the comorbidity of O CD with disruptive our juvenile OCD subjects found preliminary evidence

behavior disorders is a correlate of juvenile forms of for such subtypes with higher rates of anxiety and

OCD only or of OCD at any age remains unknown developmental disorders (in subjects with TS) and

]. AM . ACAD. C H I LD ADO LESC . PSYCHIATRY, 35: 12 , DEC EM BER 1996 1643

GELLER ET AL.

bipolar and developmental disorders (in subjects with The finding of comorbidity with psychosis in our

ADHD), although the numbers are small and further sample of OCD juveniles is consistent with recent

studies are needed. reports highlighting this overlap. While once thought

Considering the likely heterogeneity of OCD, atten- to be rare, the co-occurrence of psychotic symptoms

tion to a developmental subtype may lead to the in adult patients with OCD was recently reviewed by

identification of more homogeneous subgroups of the Dowling et al. (1995), who concluded that comorbidity

disorder. For example, a number of reports have indi- between OCD and psychotic disorders may not be

cated that the familiality and, by extension, the genetic rare and that earlier hierarchical approaches to diagnoses

contribution to the etiology of OCD is increased may have minimized the study of psychotic symptoms

in younger-age-of-onset subjects (Geller et al., 1995; in OCD patients. Considering that the comorbidity

Lenane et al., 1990; Pauls et al., 1995; Swedo et al., with mania and psychosis was the major factor account-

1989). Furthermore, childhood-onset OCD is signifi-

ing for the high rate of psychiatric hospitalization

cantly male-predominant compared with adult-onset

documented in our sample (37%), the appropriate

OCD and may be associated with other prototypical

identification of these disorders is of much clinical

neurodevelopmental disabilities. Thus, continuities and

relevance.

discontinuities between very-early-onset (childhood)

In our study, subjects given diagnoses of mania and

and late-onset (adult) OCD have yet to be established

psychosis met full DSM-III-R diagnostic criteria for

(Pauls, 1995).

these disorders. In particular, subjects were not consid-

In addition to an excessof disruptive behavior disor-

ered psychotic based on lack of insight into their

ders in our sample of juveniles with OCD, we also

obsessive-compulsive symptoms, a fact important to

found high rates of mania and psychosis in our sample.

Inasmuch as these two diagnoses have also been a record in view of the DSM-IVfield trial recommenda-

primary target of exclusionary criteria in previous stud- tions (Foa and Kozak, 1995) to deemphasize insight

ies of juvenile OCD, it is not at all surprising that as a diagnostic requirement of OCD and the new

the rates of these disorders were low or nonexistent in DSM-IV specifier of "with poor insight" (American

previous studies. In fact, the need to exclude OCD Psychiatric Association, 1994).

subjects with mania and psychosis suggests that these If confirmed, the wider scope of psychiatric cornor-

comorbid diagnoses do exist. bidity of juvenile OCD not only with TS, unipolar

Although the diagnosis of juvenile mania remains depression, and other anxiety disorders but also with

controversial, work by our group and others has begun disruptive behavior disorders, mania, and psychosis has

to challenge the notion that mania is uncommon or important clinical and scientific implications. Clini-

nonexistent in juveniles (Kafantaris, 1995; Weller et al., cally, because treatment decisions follow diagnosis, the

1995; Wozniak et al., 1995). Our finding of a high identification of these comorbid diagnoses may lead

rate of mania in juveniles with OCD fits well with to more successful treatment approaches and perhaps

recent reports documenting a higher than expected a more successful outcome for affected children and

overlap between OCD and mania (Kruger et al., 1995), adolescents with complex OCD. In contrast to the

TS and mania (Kerbeshian et al., 1995), and panic potential benefits of antiobsessional medications for

disorder and mania (Biederman et al., 1995b); these comorbid depression and anxiety, these compounds

novel patterns of comorbidity have never before been have no known benefits in the treatment of disruptive

reported. Also, considering that juvenile major depres- behavior disorders. In addition, the potential impact

sion is frequently bipolar (Geller et al., 1993; Strober of comorbid disruptive behavior disorders on the effi-

and Carlson, 1982; Strober et al., 1988), and that cacy of recently emphasized behavioral treatments

unipolar depression is a recognized comorbidity of (March, 1995; March et al., 1994) for young subjects

OCD in children and adolescents, it is not surprising with OCD should be considered. Because these behav-

to find an excess of bipolarity in these subjects. In ioral techniques require a fair degree of cooperation

that respect we view the additional comorbidity with on the part of subjects and their families, their ability

psychosis as a correlate of mania since psychotic symp- to participate may be compromised by inattentiveness

toms are common in mania (Wozniak et al., 1995). and oppositionalism.

1644 ]. AM. ACAD. CHILD ADOLESC. PSYCHIATRY, 35:12, DECEMBER 1996

DISRUP T IVE BEHAV IOR IN JUVEN I LE OC D

Cl inically, the presence of an additional disruptive adolescents. Ho wever, likely un even distributions re-

behavior disorder is also likely to confer more severe sulting from ascertainment biases in reviewed reports

impairment and may even represent the most troubling precluded valid formal statistical comparisons ofcornor-

set of symptoms to children and their families. For bidi ty between groups.

example, H anna (1995 ) found that th e O CD subjects Another limitation is that the structu red diagno stic

with a concurr ent disruptive behavior disorder had interview information was not collected blindly to the

higher Internalizing, Externalizing, and T otal Problem diagnoses of OCD. Ho wever, O CD patients received

scores on the CBCL (Achenbach, 1991) . In contrast, a systematic assessment battery administered to all

C BCL scores did not correlate with any demograph ic referred children and adolescents in our center with and

variables. Scientifically, stratification of O CD subjects without O CD. T he use of such structured diagnostic

on the basis of patterns of comorbidity may lead to interviews minimizes the biases in assigning diagnoses

the identifi cation of more homogeneous subtypes with and may lead to more accurate estimates of

differing correlates, outcome, and treatment responses. psychopathology.

This in turn may yield more fruitful research when Finally, the findings obtained by the different meth-

identified subgroups are studied. odologies used in our and in previous studies may not

The findin gs reported here should be examined in be easily amenable to direct comp arisons. For example,

light of their methodological limitations. M ost studies, a direct comparison of the present ing symptoms of

including this one, reported only small numbers of O CD is limit ed by a lack of clarity and information

pediatric O CD cases. H owever, the cum ulative tot al regarding the definiti on of symptom clusters, e.g..

of OCD subjects reviewed here is 244 in six samples. aggression/catastrophe obsessions.

Because the samples in th is and the other studies Despite these limitations, using structured diagno stic

reviewed in this report are of clinically referred children interview meth odology and no exclusionary criteria,

and adolescents, and because it might be assumed that we found that patterns of psychiatric comorbidity in

patients seeking care in a specialized clinical sett ing juvenile O CD may include not only tics, depression,

are likely to have mo re than one diagnosis (Berkson's and anxiety disorders, bur also disruptive behavior

bias), we do not know whether these findings will disorders, mania, and psychosis as well. Although these

generalize to nonreferred samples. T o date, pediatric findin gs await confirmation, they highlight a need for

epidemio logical studies on O CD have repo rted only careful assessment of psychiatric comorbidity in clinical

on adolescent samples (Flament et al., 1989; Valleni- and research samples of pediatric O CD subjects.

Basile et al., 1994). Thus, although OCD cases iden -

tified through epidemiological studies may differ from

clinically referred cases, th e failure to find a higher

than expected prevalence of ADHD or mania in epide- REFERENCES

miological studies may also reflect errors of omission Achenbach T (1978), The Child Behavior Profile: I. Boys aged 6-11. J

rath er than the absence of these comorbid conditions. Consult Clin PsychoI 46:478-488

Achenbach TM (1991), Manual of the Child Behavior Checklistl4-18

Alth ough more work is needed to furt her evaluate this and 1991 Profile. Burlington: University of Vermo nt Department

important issue, even if not generalizable to epidem io- of Psychiatry

Achenbach TM, Edelbrock C (1983), The Child Behavior Checklist. Burl-

logical samples, our findin gs may generalize to other ington : Un iversity Associates in Psychi atry

clinically referred samples. American Psychiatric Association (1987), Diagnostic and Statistical Ma nual

Because patients in our study were evaluated in a of M ental Disorders, 3rd edition-revised (DSM -lJI-R). Washington , DC:

American Psychiatric Association

tertiary care specialized pro gram for juveniles with American Psychiatric Association (1994), Diagnostic and Statistical Manual

OCD, it could be argued that our cases are more ofMental Disorders, 4th edition (DSM -I V). Washington , D C: American

Psychiatric Association

severe or complex than in other samples of pediatric Biederman J, Faraone 5, Lapey K (1992), Co morbidity of diagnosis in

OCD patients. However, as we described above, our attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Child Adolesc Psychiatr Clin

patients' characteristics closely resemble those of oth er North Am 1:335-360

Biederman J, Faraone 5, Mick E, Lelon E (l99 5a), Psychiatric comorbidity

referred pediatric OCD samples, suggesting that our among referred juveniles with major depression : fact or artifact? JAm

findings could generalize to other referred OCD sam- Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 34:579-590

Biederman J, Faraone SV, Marrs A et al. (l 995b) , Developmental aspects

ples treated in cente rs with specialized interest or exper- of panic disorder. Presented at the Annu al Meeti ng of the American

tise in the management of OCD childr en and Academy of C hild and Adolescent Psychiatry, New O rleans

J. AM . ACAD . C H ILD ADOLES C. PSYCH IA TRY , 35 : 12 , DECEMB ER 1996 1645

GELLER ET AL.

Biederman ], Munir K, Knee D et al. (1987), High rate of affective with obsessive compulsive disorder. ] Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychia-

disorders in probands with attention deficit disorder and in their try 29:407-412

relatives: a controlled family study. Am] Psychiatry 144:330-333 Match ]S (1995), Cognitive-behavioral psychotherapy for children and

Biederman ], Newcom ], Sprich S (1991a), Co morbidity of attention adolescents with OCD: a review and recommendations for treatment.

deficit hyperactivity disorder with conduct, depressive, anxiety, and ] Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 34:7-18

orher disorders. Am] Psychiatry 148:564-577 March ]S, Mulle K, Herbel B (1994), Behavioral psychotherapy for children

Biederman ]B, Faraone SV, Keenan K, Steingard R, Tsuang MT (1991b), and adolescents with obsessive-compulsive disorder: an open trial of a

Familial association between attention deficit disorder and anxiery new protocol-driven treatment package. ] Am Acad Child Adolesc

disorders. Am] Psychiatry 148:251-256 Psychiatry 33:333-34 I

Biederman ]B, Milberger S, Faraone SV, Guite ], Warburton R (1994), Orvaschel H (1985), Psychiatric interviews suitable for use in research with

Associations between childhood asthma and AD HD: issuesof psychiatric children and adolescents. Psychopharmacol Bull 21:737-745

comorbidity and familiality. ] Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry Pauls D (1995), Continuities and discontinuities in obsessive compulsive

33:842-848 disorder across the life span. Presented at the Annual Meeting of the

Dowling FG, Pato MT, Pato CN (1995), Comorbidiry of obsessive- American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, New Orleans

Pauls D, Alsobrook] II, Goodman W, Rasmussen S, Leckman] (1995),

compulsive and psychotic symptoms: a review. Harv Rev Psychiatry

A family study of obsessive-compulsive disorder. Am] Psychiatry

3:75-83

152:76-84

Flament M, Whitaker A, Rapoport I. Davies M, Berg C, Shaffer D

Puig-Antich ], Chambers WJ (1978), Schedule fOr Affictive Disorders and

(1989), An epidemiological study of obsessive-compulsive disorder in

Schizophrenia for School-Age Children (Present Episode Version) (K-SADS-

adolescence. In: Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder in Children and Adoles-

P). Pittsburgh: Western Psychiatric Institute and Clinic, Universiry of

cents, Rapoport ], ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Press, Pittsburgh School of Medicine

pp 253-267 Rasmussen S, Eisen] (1992a), The epidemiology and clinical features of

Foa E, Kozak M (1995), DSM-IVfield trial: obsessive-compulsivedisorder. obsessive compulsive disorder. Psychiatr Clin North Am 15:743-758

Am] Psychiatry 152:90-96 Rasmussen S, Eisen] (1992b), The epidemiology and differential diagnosis

Geller B, Fox L, Fletcher M (1993), Effect of tricyclic antidepressants on of obsessive compulsive disorder. ] Clin Psychiatry 53:4-10

switching to mania and on the onset of bipolariry in depressed 6- to Riddle M, Scahill L, King R er al. (1990), Obsessive compulsive disorder

12-year-olds. ] Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 32:43-50 in children and adolescents: phenomenology and family history. ] Am

Geller D, Biederman], Reed E, Spencer T, Wilens T (1995), Similarities Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 29:766-772

in response to Huoxetine in the treatment of children and adolescents Riddle MA, Scahill L, Smith] er al. (1993), Children's Yale-Brown

with obsessive-compulsive disorder. ] Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychia- Obsessive Compulsive Scale (CY-BOCS). Scientific Proceedings, 48th

try 34:36-44 Annual Meeting of the Society of Biological Psychiatry 33:103A-I04A

Goodman WK, Price LH, Rasmussen SA et al. (1989a), The Yale-Brown Singer HS, Walkup]T (1991), Tourette syndrome and other tic disorders:

Obsessive Compulsive Scale: 1. Development, use, and reliabiliry. Arch diagnosis, pathophysiology, and treatment (review). Medicine (Balti-

Gen Psychiatry 46:1006-1011 more) 70:15-32

Goodman WK, Price LH, Rasmussen SA et al. (1989b), The Yale-Brown Strober M, Carlson G (1982), Bipolar illness in adolescents with major

Obsessive Compulsive Scale: 11. Validity. Arch Gen Psychiatry depression: clinical, genetic, and psychopharmacological predictors in

46:1012-1016 a three- to four-year prospective follow-up investigation. Arch Gen

Hanna GL (1995), Demographic and clinical features of obsessive-compul- Psychiatry 39:549-555

sive disorder in children and adolescents. ] Am Acad Child Adolesc Strober M, Morrell W, Burroughs ], Lampert C, Danforth H, Freeman

Psychiatry 34: 19-27 R (1988), A family study of bipolar 1 disorder in adolescence: early

Hardin MT, Epperson N, Riddle MA, Scahill L, King RA, Orr SI (1991), onset of symptoms linked to increased familial loading and lithium

Children's Yale-Brown Obsessive Compulsive Scale (CY-BOCS): psy- resistance. ] Affict Disord 15:255-268

chometrics, reliabiliry, and validiry. In: Scientific Proceedings, 38th Swedo S, Rapoport], Leonard H, Lenane M, Cheslow D (1989), Obsessive-

Annual Meeting of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent compulsive disorder in children and adolescents. Arch Gen Psychiatry

Psychiatry 7:51 46:335-341

Hollingshead A (1965), Two Factor Index of Social Position. New Haven, Toro J. Cervera M, Osejo E, Salamero M (1992), Obsessive-compulsive

disorder in childhood and adolescence: a clinical study. ] Child Psychol

CT: Yale University Department of Sociology

Psychiatry 33:1025-1037

Kafantaris V (1995), Treatment of bipolar disorder in children and adoles-

Valleni-BasileL, Garrison C,]ackson K et al. (1994), Frequency of obsessive-

cents. ] Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 34:732-741

compulsive disorder in a communiry sample of young adolescents. ]

Karno M, Golding], Sorenson S, Burnam A (1988), The epidemiology

Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 33:782-791

of obsessive-compulsive disorder in five US communities. Arch Gen Weissman M, Bland R, Canino G et al. (1994), The cross national

Psychiatry 45:1094-1099 epidemiology of obsessivecompulsive disorder. Am] Psychiatry 55:5-10

Kerbeshian ], Burd L, Klug MG (1995), Comorbid Tourette's disorder Weller EB, Weller RA, Fristad MA (1995), Bipolar disorder in children:

and bipolar disorder: an etiologic perspective. Am] Psychiatry misdiagnosis, underdiagnosis, and future directions. ] Am Acad Child

152:1646-1651 Adolesc Psychiatry 34:709-714

Kruger S, Cooke RG, Hasey GM, lorna T, Persad E (1995), Comorbidiry Weiner Z, Reich T, Herjanic B, lung K, Amado H (1987), Reliabiliry,

of obsessive-compulsive disorder in bipolar disorder. ] Affict Disord validiry and child agreement studies of the Diagnostic Interview for

34:117-120 Children and Adolescents (OlCA). ] Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychia-

Last CG, Strauss CC (1989), Obsessive-compulsive disorder in childhood. try 26:649-653

] Anxiety Disord 3:295-302 Wozniak ], Biederman ], Kiely K et al. (1995), Mania-like symptoms

Lenane M, Swedo S, Leonard H, Pauls D, Sceery W, Rapoport] (1990), suggestive of childhood-onset bipolar disorder in clinically referred

Psychiatric disorders in first degree relatives of children and adolescents children. ] Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 34:867-876

1646 ]. AM. ACAD. CHILD ADOLESC. PSYCHIATRY, 35:12, DECEMBER 1996

You might also like

- Fear of IntimacyDocument21 pagesFear of Intimacygraess100% (2)

- Anxiety Disorder EbookDocument260 pagesAnxiety Disorder Ebookzoesobol100% (5)

- The Cognitive Neuroscience of NarcissismDocument9 pagesThe Cognitive Neuroscience of NarcissismAlex RodriguesNo ratings yet

- Depression Worksheet - 02 - Behavioural Activation PDFDocument1 pageDepression Worksheet - 02 - Behavioural Activation PDFsolNo ratings yet

- Summary of Behavioral TheoriesDocument9 pagesSummary of Behavioral TheoriesNoverlyn UbasNo ratings yet

- Executive Functions by Thomas Brown 1Document6 pagesExecutive Functions by Thomas Brown 1api-247044545No ratings yet

- Social Story FormulaDocument16 pagesSocial Story Formulasafa_sabaNo ratings yet

- Egger Angold 2006emot Behav Problems in PreschoolerDocument25 pagesEgger Angold 2006emot Behav Problems in PreschoolerccarmogarciaNo ratings yet

- Egger & Angold, 2006 Disorders - DiscussionDocument25 pagesEgger & Angold, 2006 Disorders - DiscussionAlkistis MarinakiNo ratings yet

- 1 s2.0 S0890856709626150 Main PDFDocument15 pages1 s2.0 S0890856709626150 Main PDFJúlia JanoviczNo ratings yet

- A Pilot Investigation of Cognitive Therapy For Generalized Anxiety Disorder in Children Aged 7-17 YearsDocument9 pagesA Pilot Investigation of Cognitive Therapy For Generalized Anxiety Disorder in Children Aged 7-17 Yearsstudent8218No ratings yet

- Cognitive Distortions and Psychiatric Diagnosis in Dually Diagnosed AdolescentsDocument6 pagesCognitive Distortions and Psychiatric Diagnosis in Dually Diagnosed AdolescentsBosondos BedooNo ratings yet

- TCCG e Sertralina AshbarDocument9 pagesTCCG e Sertralina Ashbarsuporteflnc02No ratings yet

- Childhood-Onset Schizophrenia: The Severity of Premorbid CourseDocument11 pagesChildhood-Onset Schizophrenia: The Severity of Premorbid CourseLuis MiguelNo ratings yet

- Milberger 1996Document9 pagesMilberger 1996JohnnyNo ratings yet

- Developmental and Clinical Predictors of Comorbidity For Youth With OCDDocument7 pagesDevelopmental and Clinical Predictors of Comorbidity For Youth With OCDViktória Papucsek LelkesNo ratings yet

- Hudziak 2004Document9 pagesHudziak 2004Alar Urrutikoetxea VicenteNo ratings yet

- Effect Size Lithium, Divalproex Sodium, Carbamazepine in Children Adolescents With BipolarDocument8 pagesEffect Size Lithium, Divalproex Sodium, Carbamazepine in Children Adolescents With BipolarKaren SánchezNo ratings yet

- Behavior Problems in Children of Parents With Anxiety DisordersDocument6 pagesBehavior Problems in Children of Parents With Anxiety DisordersRaquel de Azevedo de SouzaNo ratings yet

- Jansen 2000Document12 pagesJansen 2000dimasprastiiaNo ratings yet

- Clinical Features of Young Children Referred For Impairing Temper OutburstsDocument9 pagesClinical Features of Young Children Referred For Impairing Temper OutburstsRafael MartinsNo ratings yet

- Συννοσηρή Ψυχοπαθολογία Και Κλινική Συμπτωματολογία Σε Παιδιά Και Εφήβους Με Ιδεοψυχαναγκαστική ΔιαταραχήDocument10 pagesΣυννοσηρή Ψυχοπαθολογία Και Κλινική Συμπτωματολογία Σε Παιδιά Και Εφήβους Με Ιδεοψυχαναγκαστική ΔιαταραχήEviKapaNo ratings yet

- Management Guidelines For Anxiety Disorders in Children and AdolescentsDocument23 pagesManagement Guidelines For Anxiety Disorders in Children and AdolescentsHari HaranNo ratings yet

- 2004 Rest-Activity Cycles in Childhood andDocument9 pages2004 Rest-Activity Cycles in Childhood andsomya mathurNo ratings yet

- Prospective 10-Year Follow-Up in Adolescent Anorexia Nervosa-Course, Outcome, Psychiatric Comorbidity, and Psychosocial AdaptationDocument10 pagesProspective 10-Year Follow-Up in Adolescent Anorexia Nervosa-Course, Outcome, Psychiatric Comorbidity, and Psychosocial AdaptationCătălina LunguNo ratings yet

- Child Psychiatry - Introduction PDFDocument7 pagesChild Psychiatry - Introduction PDFRafli Nur FebriNo ratings yet

- Tourette Syndrome in The General Child Population: Cognitive Functioning and Self-PerceptionDocument9 pagesTourette Syndrome in The General Child Population: Cognitive Functioning and Self-PerceptionIdoia PñFlrsNo ratings yet

- Prior Juvenile Diagnosis in Adults With Mental DisorderDocument9 pagesPrior Juvenile Diagnosis in Adults With Mental DisorderAdhya DubeyNo ratings yet

- Childhood Onset Schizophrenia - The Severity of Premorbid CourseDocument12 pagesChildhood Onset Schizophrenia - The Severity of Premorbid CourseDaniel NakakuraNo ratings yet

- Clinical and Diagnostic Implications of Lifetime Attention-Deficit-Hyperactivity Disorder Comorbidity in Adults With Bipolar DisorderDocument7 pagesClinical and Diagnostic Implications of Lifetime Attention-Deficit-Hyperactivity Disorder Comorbidity in Adults With Bipolar DisorderCarla NapoliNo ratings yet

- Bühler (2011)Document9 pagesBühler (2011)Diane MxNo ratings yet

- Symptom Profiles in Children With ADHDDocument10 pagesSymptom Profiles in Children With ADHDSimona VladNo ratings yet

- Szatmari1995asperger, AutyzmDocument10 pagesSzatmari1995asperger, Autyzm__aguNo ratings yet

- Somatic Symptoms in Children and Adolescents With Anxiety DisordersDocument9 pagesSomatic Symptoms in Children and Adolescents With Anxiety DisordersDũng HồNo ratings yet

- Symptom Profiles of Autism Spectrum Disorder in Tuberous Sclerosis ComplexDocument14 pagesSymptom Profiles of Autism Spectrum Disorder in Tuberous Sclerosis ComplexWhyra Namikaze ComeyNo ratings yet

- ADHD, Asperger Syndrome, and High-Functioning Autism: ArticleDocument4 pagesADHD, Asperger Syndrome, and High-Functioning Autism: Articlelaura2121No ratings yet

- Farrell 2012 PDFDocument9 pagesFarrell 2012 PDFLaura HdaNo ratings yet

- A Parent-Report Instrument For Identifying One-Year-Olds Risk TEADocument20 pagesA Parent-Report Instrument For Identifying One-Year-Olds Risk TEADani Tsu100% (1)

- Bryson, Zwaigenbaum Et Al 2007Document13 pagesBryson, Zwaigenbaum Et Al 2007mariaNo ratings yet

- Autism in ToodlerDocument15 pagesAutism in ToodlerPar DoNo ratings yet

- 1 s2.0 S0890856709609552 MainDocument9 pages1 s2.0 S0890856709609552 Main서혜주No ratings yet

- Barrett 2004Document17 pagesBarrett 2004danielblancozepaNo ratings yet

- TBH & TDAH Comorbidity of Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder With Early - and Late-Onset BipDocument3 pagesTBH & TDAH Comorbidity of Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder With Early - and Late-Onset BipVeio MacieiraNo ratings yet

- 1 s2.0 S0890856709626472 MainDocument6 pages1 s2.0 S0890856709626472 Mainsiltu7No ratings yet

- Treatment Options For The Cardinal Symptoms of Disruptive Mood Dysregulation DisorderDocument14 pagesTreatment Options For The Cardinal Symptoms of Disruptive Mood Dysregulation DisorderRafael MartinsNo ratings yet

- Problemas de Conducta en Enf CronicosDocument15 pagesProblemas de Conducta en Enf Cronicoscarolina riveraNo ratings yet

- Abbe M. Garcia - Phenomenology of Early Childhood Onset Obsessive Compulsive DisorderDocument8 pagesAbbe M. Garcia - Phenomenology of Early Childhood Onset Obsessive Compulsive DisorderGerti SqapiNo ratings yet

- JCPP 12590Document15 pagesJCPP 12590Javier CáceresNo ratings yet

- Schizophr Bull 1994 Gordon 697 712Document16 pagesSchizophr Bull 1994 Gordon 697 712EdwardVargasNo ratings yet

- The Child and Adolescent First-Episode Psychosis Study (CAFEPS) : Design and Baseline ResultsDocument12 pagesThe Child and Adolescent First-Episode Psychosis Study (CAFEPS) : Design and Baseline ResultsQwerty QwertyNo ratings yet

- Disruptive Mood Dysregulation Disorder at Ages 13-18: Results From The National Comorbidity Survey-Adolescent SupplementDocument7 pagesDisruptive Mood Dysregulation Disorder at Ages 13-18: Results From The National Comorbidity Survey-Adolescent SupplementRafael MartinsNo ratings yet

- Depression in Children AdolescentsDocument7 pagesDepression in Children AdolescentstoddhavelkaNo ratings yet

- Can Children With Autism Recover Helt Fein Etal FINALDocument28 pagesCan Children With Autism Recover Helt Fein Etal FINALkarthick vasudevanNo ratings yet

- Artículo Wender UtahDocument7 pagesArtículo Wender UtahHelenaNo ratings yet

- Child Psychology Psychiatry - 2012 - Simonoff - Severe Mood Problems in Adolescents With Autism Spectrum DisorderDocument10 pagesChild Psychology Psychiatry - 2012 - Simonoff - Severe Mood Problems in Adolescents With Autism Spectrum DisorderlidiaNo ratings yet

- A-Hudson, Hall & Harkness (2019)Document11 pagesA-Hudson, Hall & Harkness (2019)Jordanitha BhsNo ratings yet

- Epidemiología de Los Trastornos Psiquiátricos en Niños y Adolescentes Revisión 2009Document12 pagesEpidemiología de Los Trastornos Psiquiátricos en Niños y Adolescentes Revisión 2009Javiera Luna Marcel Zapata-SalazarNo ratings yet

- Management of Psychiatric Disorders in Children and Adolescents With Atypical AntipsychoticsDocument17 pagesManagement of Psychiatric Disorders in Children and Adolescents With Atypical Antipsychoticsnithiphat.tNo ratings yet

- Anxiety Problems in Young People With Asperger Syndrome 19 10 09Document30 pagesAnxiety Problems in Young People With Asperger Syndrome 19 10 09simoilieNo ratings yet

- Acceptance or Despair Maternal Adjustment To Having A ChildDocument11 pagesAcceptance or Despair Maternal Adjustment To Having A ChildKarel GuevaraNo ratings yet

- Insight in Pediatric Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder: Associations With Clinical PresentationDocument9 pagesInsight in Pediatric Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder: Associations With Clinical PresentationHelenaNo ratings yet

- Early Stages in The Development of Bipolar Disorder - 2010Document9 pagesEarly Stages in The Development of Bipolar Disorder - 2010cesia leivaNo ratings yet

- CBCL Profiles of Children and Adolescents With Asperger Syndrome - A Review and Pilot StudyDocument12 pagesCBCL Profiles of Children and Adolescents With Asperger Syndrome - A Review and Pilot StudyWildan AnrianNo ratings yet

- A Prospective Follow-Up Study of Pediatric Bipolar Disorder in Boys With TDAHDocument7 pagesA Prospective Follow-Up Study of Pediatric Bipolar Disorder in Boys With TDAHCarla NapoliNo ratings yet

- Tulburari Afective StudiuDocument10 pagesTulburari Afective StudiuStanculescu AlinaNo ratings yet

- Diagnosis and Treatment of Children With Autism Spectrum DisordersFrom EverandDiagnosis and Treatment of Children With Autism Spectrum DisordersRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- A PRISMA Systematic Review of Adolescent Gender Dysphoria Literature: 1) EpidemiologyDocument38 pagesA PRISMA Systematic Review of Adolescent Gender Dysphoria Literature: 1) EpidemiologyAngela EnacheNo ratings yet

- Schizophrenia: Epidemiology, Causes, Neurobiology, Pathophysiology, and TreatmentDocument37 pagesSchizophrenia: Epidemiology, Causes, Neurobiology, Pathophysiology, and TreatmentAngela EnacheNo ratings yet

- Relatii InterpersonaleDocument12 pagesRelatii InterpersonaleAngela EnacheNo ratings yet

- Insomnia 1Document38 pagesInsomnia 1Angela EnacheNo ratings yet

- Exploration and Support in Psychotherapeutic Environments For Psychotic PatientsDocument11 pagesExploration and Support in Psychotherapeutic Environments For Psychotic PatientsAngela EnacheNo ratings yet

- Digital Technologies For Schizophrenia Management: A Descriptive ReviewDocument22 pagesDigital Technologies For Schizophrenia Management: A Descriptive ReviewAngela EnacheNo ratings yet

- Conceptul Actual de Psihoză: RezumatDocument8 pagesConceptul Actual de Psihoză: RezumatAngela EnacheNo ratings yet

- Barriers and Facilitators To User Engagement With Digital Mental Health Interventions: A Systematic ReviewDocument30 pagesBarriers and Facilitators To User Engagement With Digital Mental Health Interventions: A Systematic ReviewAngela EnacheNo ratings yet

- Amintirile Nasterii, Trauma Nasterii Si AnxietateaDocument12 pagesAmintirile Nasterii, Trauma Nasterii Si AnxietateaAngela EnacheNo ratings yet

- Introduction To The Special Issue On Pre-Therapy: Person-Centered & Experiential PsychotherapiesDocument6 pagesIntroduction To The Special Issue On Pre-Therapy: Person-Centered & Experiential PsychotherapiesAngela EnacheNo ratings yet

- Lee 2021Document11 pagesLee 2021Angela EnacheNo ratings yet

- Psychotic Depressive Disorder: A Separate Entity?Document7 pagesPsychotic Depressive Disorder: A Separate Entity?Angela EnacheNo ratings yet

- Ethnic Factors in Group Process: Cultural Dynamics in Multi-Ethnic Therapy GroupsDocument7 pagesEthnic Factors in Group Process: Cultural Dynamics in Multi-Ethnic Therapy GroupsAngela EnacheNo ratings yet

- The Cardiff Anomalous Perceptions Scale (CAPS) : A New Validated Measure of Anomalous Perceptual ExperienceDocument12 pagesThe Cardiff Anomalous Perceptions Scale (CAPS) : A New Validated Measure of Anomalous Perceptual ExperienceAngela EnacheNo ratings yet

- International Journal of Nursing Studies: Wai-Tong Chien, Ian NormanDocument20 pagesInternational Journal of Nursing Studies: Wai-Tong Chien, Ian NormanAngela EnacheNo ratings yet

- The Effect of Previous Psychotic Mood Episodes On Cognitive Impairment in Euthymic Bipolar PatientsDocument10 pagesThe Effect of Previous Psychotic Mood Episodes On Cognitive Impairment in Euthymic Bipolar PatientsAngela EnacheNo ratings yet

- Narcism Ronningstam1996Document15 pagesNarcism Ronningstam1996Angela EnacheNo ratings yet

- Defensive Coping Related To Perceived Lack of Self-Efficacy As Evidenced by Denial of Obvious ProblemsDocument2 pagesDefensive Coping Related To Perceived Lack of Self-Efficacy As Evidenced by Denial of Obvious ProblemsJeyser T. GamutiaNo ratings yet

- Remedial Part 2Document13 pagesRemedial Part 2Prince Rener Velasco PeraNo ratings yet

- GINDocument169 pagesGINdragan100% (2)

- Drawing A Family MapDocument14 pagesDrawing A Family MapJack Greene100% (5)

- Sullivan's Interpersonal TheoryDocument12 pagesSullivan's Interpersonal TheorySumam NeveenNo ratings yet

- The Soloist PaperDocument6 pagesThe Soloist Paperapi-326282879No ratings yet

- Transactional AnalysisDocument52 pagesTransactional AnalysisHitesh Parmar100% (2)

- Principles of Instruction Barak RosenshineDocument1 pagePrinciples of Instruction Barak RosenshineSoroush SabbaghanNo ratings yet

- Family Functioning, Coping, and Psychological AdjustmentDocument7 pagesFamily Functioning, Coping, and Psychological AdjustmentexellionNo ratings yet

- Burn OutDocument8 pagesBurn OutAtiqahAzizanNo ratings yet

- Creativity Process & Blocks To CreativityDocument28 pagesCreativity Process & Blocks To CreativityDhiraj YAdavNo ratings yet

- Adhd 2Document6 pagesAdhd 2api-259262734No ratings yet

- Review TopicsDocument12 pagesReview TopicsFalguniNo ratings yet

- Mindscape TransportationDocument2 pagesMindscape TransportationSunčica Nisam100% (1)

- Test HDRS EnglishDocument4 pagesTest HDRS EnglishReisya GinaNo ratings yet

- Psychoanalytical Approach To Juvenile DelinquencyDocument2 pagesPsychoanalytical Approach To Juvenile DelinquencyChandan BhatiNo ratings yet

- Sigmund Freud Topic 2Document5 pagesSigmund Freud Topic 2aileen elizagaNo ratings yet

- A.12 PARENTING 2016 Amended PDFDocument29 pagesA.12 PARENTING 2016 Amended PDFHelenaNo ratings yet

- Michael White'S Narrative Therapy: Alan CarrDocument19 pagesMichael White'S Narrative Therapy: Alan Carrmadalina mihaelaNo ratings yet

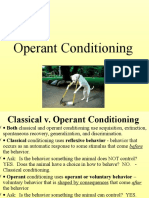

- Operant ConditioningDocument76 pagesOperant ConditioningJiya JanjuaNo ratings yet

- Problem: Pain at 6/10 For A "Sore Right Shoulder" Date Evaluated: December 14, 2020Document2 pagesProblem: Pain at 6/10 For A "Sore Right Shoulder" Date Evaluated: December 14, 2020florenzoNo ratings yet

- Ideational Apraxia. A Deficit in Tool Selection and UseDocument4 pagesIdeational Apraxia. A Deficit in Tool Selection and UseAlejandro Israel Garcia EsparzaNo ratings yet

- CACG Bibliography 7 23Document26 pagesCACG Bibliography 7 23simmy221No ratings yet

- Sex AddictionDocument33 pagesSex AddictionShabaz Akhtar100% (2)