Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Safari - Eastern Philosophy

Safari - Eastern Philosophy

Uploaded by

Niña Dyan0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

86 views1 pagephilosophy

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this Documentphilosophy

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Download as pdf or txt

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

86 views1 pageSafari - Eastern Philosophy

Safari - Eastern Philosophy

Uploaded by

Niña Dyanphilosophy

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Download as pdf or txt

You are on page 1of 1

Wiki Loves Earth photo contest: Upload

photos of natural heritage sites in the

Philippines to help Wikipedia and win

fantastic prizes!

Eastern philosophy

For the album by Apathy, see Eastern Philosophy

(album).

Eastern philosophy or Asian philosophy

includes the various philosophies that

originated in East and South Asia including

Chinese philosophy, Japanese philosophy, and

Korean philosophy which are dominant in East

Asia and Vietnam,[1] and Indian philosophy

(including Buddhist philosophy) which are

dominant in South Asia, Southeast Asia, Tibet

and Mongolia.[2][3]

Indian philosophy

Main article: Indian philosophy

Further information: Hinduism and Hindu philosophy

An ancient image of Valluvar

Indian philosophy refers to ancient

philosophical traditions (Sanskrit: dárśana;

'world views', 'teachings')[4] of the Indian

subcontinent. Jainism may have roots dating

back to the times of the Indus Valley

Civilization.[5][6][7] The major orthodox schools

arose sometime between the start of the

Common Era and the Gupta Empire.[8] These

Hindu schools developed what has been called

the "Hindu synthesis" merging orthodox

Brahmanical and unorthodox elements from

Buddhism and Jainism.[9] Hindu thought also

spread east to the Indonesian Srivijaya empire

and the Cambodian Khmer Empire. These

religio-philosophical traditions were later

grouped under the label Hinduism. Hinduism is

the dominant religion, or way of life,[note 1] in

South Asia. It includes Shaivism, Vaishnavism

and Shaktism[12] among numerous other

traditions, and a wide spectrum of laws and

prescriptions of "daily morality" based on

karma, dharma, and societal norms. Hinduism

is a categorization of distinct intellectual or

philosophical points of view, rather than a rigid,

common set of beliefs.[13] Hinduism, with

about one billion followers[14] is the world's

third largest religion, after Christianity and

Islam. Hinduism has been called the "oldest

religion" in the world and is traditionally called

Sanātana Dharma, "the eternal law" or the

"eternal way";[15][16][17] beyond human

origins.[17] Western scholars regard Hinduism

as a fusion[note 2] or synthesis[18][note 3][18] of

various Indian cultures and traditions,[19][20][21]

with diverse roots[22][note 4] and no single

founder.[27]

Some of the earliest surviving philosophical

texts are the Upanishads of the later Vedic

period (1000–500 BCE). Important Indian

philosophical concepts include dharma, karma,

samsara, moksha and ahimsa. Indian

philosophers developed a system of

epistemological reasoning (pramana) and logic

and investigated topics such as Ontology

(metaphysics, Brahman-Atman, Sunyata-

Anatta), reliable means of knowledge

(epistemology, Pramanas), value system

(axiology) and other topics.[28][29][30] Indian

philosophy also covered topics such as

political philosophy as seen in the Arthashastra

c. 4th century BCE and the philosophy of love

as seen in the Kama Sutra. The Kural literature

of c. 1st century BCE, written by the Tamil

poet-philosopher Valluvar, is believed by many

scholars to be based on Jain

philosophies.[31][32]

Later developments include the development

of Tantra and Iranian-Islamic influences.

Buddhism mostly disappeared from India after

the Muslim conquest in the Indian

subcontinent, surviving in the Himalayan

regions and south India.[33] The early modern

period saw the flourishing of Navya-Nyāya (the

'new reason') under philosophers such as

Raghunatha Siromani (c. 1460–1540) who

founded the tradition, Jayarama Pancanana,

Mahadeva Punatamakara and Yashovijaya (who

formulated a Jain response).[34]

Orthodox schools

The principal Indian philosophical schools are

classified as either orthodox or heterodox –

āstika or nāstika – depending on one of three

alternate criteria: whether it believes the Vedas

are a valid source of knowledge; whether the

school believes in the premises of Brahman

and Atman; and whether the school believes in

afterlife and Devas.[35][36]

There are six major schools of orthodox Indian

Hindu philosophy—Nyaya, Vaisheshika,

Samkhya, Yoga, Mīmāṃsā and Vedanta, and

five major heterodox schools—Jain, Buddhist,

Ajivika, Ajñana, and Cārvāka. However, there

are other methods of classification; Vidyaranya

for instance identifies sixteen schools of Hindu

Indian philosophy by including those that

belong to the Śaiva and Raseśvara

traditions.[37][38]

Each school of Hindu philosophy has extensive

epistemological literature called Pramana-

sastras.[39][40]

In Hindu history, the distinction of the six

orthodox schools was current in the Gupta

period "golden age" of Hinduism. With the

disappearance of Vaisheshika and Mīmāṃsā, it

became obsolete by the later Middle Ages,

when the various sub-schools of Vedanta

(Dvaita "dualism", Advaita Vedanta "non-

dualism" and others) began to rise to

prominence as the main divisions of religious

philosophy. Nyaya survived into the 17th

century as Navya Nyaya "Neo-Nyaya", while

Samkhya gradually lost its status as an

independent school, its tenets absorbed into

Yoga and Vedanta.

Sāmkhya and Yoga

King Amsuman and the

yogic sage Kapila. The

Samkhya school

traditionally traces itself

back to sage Kapila.

Sāmkhya is a dualist philosophical tradition

based on the Samkhyakarika (c. 320–540

CE),[41] while the Yoga school was a closely

related tradition emphasizing meditation and

liberation whose major text is the Yoga sutras

(c. 400 CE).[42] Elements of proto-Samkhya

ideas can however be traced back all the way

to the period of the early Upanishads.[43] One

of the main differences between the two

closely related schools was that Yoga allowed

for the existence of a God, while most

Sāmkhya thinkers criticized this idea.[44]

Sāmkhya epistemology accepts three of six

pramanas (proofs) as the only reliable means

of gaining knowledge; pratyakṣa (perception),

anumāṇa (inference) and śabda

(word/testimony of reliable sources).[45] The

school developed a complex theoretical

exposition of the evolution of consciousness

and matter. Sāmkhya sources argue that the

universe consists of two realities, puruṣa

(consciousness) and prakṛti (matter).

As shown by the Sāṁkhyapravacana Sūtra (c.

14th century CE), Sāmkhya continued to

develop throughout the medieval period.

Nyāya

The Nyāya school of epistemology, explores

sources of knowledge (Pramāṇa) and is based

on the Nyāya Sūtras (circa 6th-century BCE

and 2nd-century CE).[46] Nyāya holds that

human suffering arises out of ignorance and

liberation arises through correct knowledge.

Therefore, they sought to investigate the

sources of correct knowledge or epistemology.

Nyāya traditionally accepts four Pramanas as

reliable means of gaining knowledge –

Pratyakṣa (perception), Anumāṇa (inference),

Upamāṇa (comparison and analogy) and

Śabda (word, testimony of past or present

reliable experts).[45] Nyāya also traditionally

defended a form of philosophical realism.[47]

The Nyāya Sūtras was a very influential text in

Indian philosophy, laying the foundations for

classical Indian epistemological debates

between the different philosophical schools. It

includes, for example, the classic Hindu

rejoinders against Buddhist not-self (anatta)

arguments.[48] The work also famously argues

against a creator God (Ishvara),[49] a debate

which became central to Hinduism in the

medieval period.

Vaiśeṣika

Vaiśeṣika is a naturalist school of atomism,

which accepts only two sources of knowledge,

perception and inference.[50] This philosophy

held that the universe was reducible to

paramāṇu (atoms), which are indestructible

(anitya), indivisible, and have a special kind of

dimension, called “small” (aṇu). Whatever we

experience is a composite of these atoms.[51]

Vaiśeṣika organized all objects of experience

into what they called padārthas (literally: 'the

meaning of a word') which included six

categories; dravya (substance), guṇa (quality),

karma (activity), sāmānya (generality), viśeṣa

(particularity) and samavāya (inherence). Later

Vaiśeṣikas (Śrīdhara and Udayana and

Śivāditya) added one more category abhava

(non-existence). The first three categories are

defined as artha (which can perceived) and

they have real objective existence. The last

three categories are defined as budhyapekṣam

(product of intellectual discrimination) and they

are logical categories.[52]

Mīmāṃsā

Mīmāṃsā is a school of ritual orthopraxy and is

known for its hermeneutical study and

interpretation of the Vedas.[53] For this

tradition, the study of dharma as rituals and

social duties was paramount. They also held

that the Vedas were "eternal, authorless, [and]

infallible" and that Vedic injunctions and

mantras in rituals are prescriptive actions of

primary importance.[53] Because of their focus

on textual study and interpretation, Mīmāṃsā

also developed theories of philology and the

philosophy of language which influenced other

Indian schools.[54] They primarily held that the

purpose of language was to clearly prescribe

proper actions, rituals and correct dharma

(duty or virtue).[55] Mīmāṃsā is also mainly

atheistic, holding that the evidence for the

existence of God is insufficient and that the

Gods named in the Vedas have no existence

apart from the names, mantras and their

power.[56]

A key text of the Mīmāṃsā school is the

Mīmāṃsā Sūtra of Jaimini and major Mīmāṃsā

scholars include Prabhākara (c. 7th century)

and Kumārila Bhaṭṭa (fl. roughly 700). The

Mīmāṃsā school strongly influenced Vedānta

which was also known as Uttara-Mīmāṃsā,

however while Mīmāṃsā emphasized

karmakāṇḍa, or the study of ritual actions,

using the four early Vedas, the Vedānta

schools emphasized jñanakāṇḍa, the study of

knowledge, using the later parts of Vedas like

the Upaniṣads.[53]

Vedānta

Adi Shankara (8th century

CE) the main exponent of

Advaita Vedānta

Vedānta (meaning "end of the Vedas") or

Uttara-Mīmāṃsā, are a group of traditions

which focus on the philosophical issues found

in the Prasthanatrayi (the three sources),

which are the Principal Upanishads, the

Brahma Sutras and the Bhagavad Gita.[57]

Vedānta sees the Vedas, particularly the

Upanishads, as a reliable source of knowledge.

The central concern for these schools is the

nature of and relationship between Brahman

(ultimate reality, universal consciousness),

Ātman (individual soul) and Prakriti (empirical

world).

The sub-traditions of Vedānta include Advaita

(non-dualism), Vishishtadvaita (qualified non-

dualism), Dvaita (dualism) and Bhedabheda

(difference and non-difference).[58] Due the

popularity of the bhakti movement, Vedānta

came to be the dominant current of Hinduism

in the post-medieval period.

Other

While the classical enumeration of Indian

philosophies lists six orthodox schools, there

are other schools which are sometimes seen as

orthodox. These include:[37]

Paśupata, an ascetic school of Shaivism

founded by Lakulisha (~2nd century CE).

Śaiva Siddhānta, a school of dualistic

Shaivism which was strongly influenced by

Samkhya.

Pratyabhijña (recognition) school of

Utpaladeva (10th century) and

Abhinavagupta (975–1025 CE), a form of

non-dual Shaiva tantra.

Raseśvara, the mercurial school

Pāṇini Darśana, the grammarian school

(which clarifies the theory of Sphoṭa)

Heterodox or Śramaṇic

schools

Main article: Śramaṇa

The nāstika or heterodox schools are

associated with the non-vedic Śramaṇic

traditions that existed in India since before the

6th century BCE.[59] The Śramaṇa movement

gave rise to diverse range of non-vedic ideas,

ranging from accepting or denying the

concepts of atman, atomism, materialism,

atheism, agnosticism, fatalism to free will,

extreme asceticism, strict ahimsa (non-

violence) and vegetarianism.[60] Notable

philosophies that arose from Śramaṇic

movement were Jainism, early Buddhism,

Cārvāka, Ajñana and Ājīvika.[61]

Jain philosophy

Jain philosophy deals extensively with the

problems of metaphysics, reality, cosmology,

ontology, epistemology and divinity. Jainism is

essentially a transtheistic religion of ancient

India.[62]:182 It continues the ancient Śramaṇa

tradition, which co-existed with the Vedic

tradition since ancient times.[63][64] The

distinguishing features of Jain philosophy

includes a mind-body dualism, denial of a

creative and omnipotent God, karma, an

eternal and uncreated universe, non-violence,

the theory of the multiple facets of truth, and a

morality based on liberation of the soul. Jain

philosophy attempts to explain the rationale of

being and existence, the nature of the Universe

and its constituents, the nature of bondage

and the means to achieve liberation.[65] It has

often been described as an ascetic movement

for its strong emphasis on self-control,

austerities and renunciation.[66] It has also

been called a model of philosophical liberalism

for its insistence that truth is relative and

multifaceted and for its willingness to

accommodate all possible view-points of the

rival philosophies.[67] Jainism strongly upholds

the individualistic nature of soul and personal

responsibility for one's decisions; and that self-

reliance and individual efforts alone are

responsible for one's liberation.[68]

The contribution of the Jains in the

development of Indian philosophy has been

significant. Jain philosophical concepts like

Ahimsa, Karma, Moksa, Samsara and the like

are common with other Indian religions like

Hinduism and Buddhism in various forms.[69]

While Jainism traces its philosophy from

teachings of Mahavira and other Tirthankaras,

various Jain philosophers from Kundakunda

and Umasvati in ancient times to Yasovijaya

and Shrimad Rajchandra in recent times have

contributed to Indian philosophical discourse in

uniquely Jain ways.

Cārvāka

Cārvāka or Lokāyata was an atheistic

philosophy of scepticism and materialism, who

rejected the Vedas and all associated

supernatural doctrines.[70] Cārvāka

philosophers like Brihaspati were extremely

critical of other schools of philosophy of the

time. Cārvāka deemed the Vedas to be tainted

by the three faults of untruth, self-

contradiction, and tautology.[71] They declared

the Vedas to be incoherent rhapsodies

invented by man whose only usefulness was to

provide livelihood to priests.[72]

Likewise they faulted Buddhists and Jains,

mocking the concept of liberation,

reincarnation and accumulation of merit or

demerit through karma.[73] They believed that,

the viewpoint of relinquishing pleasure to avoid

pain was the "reasoning of fools".[71] Cārvāka

epistemology holds perception as the primary

source of knowledge, while rejecting inference

which can be invalid.[74] The primary texts of

Cārvāka, like the Barhaspatya sutras (c. 600

BCE) have been lost.[75]

Ājīvika

Ājīvika was founded by Makkhali Gosala, it was

a Śramaṇa movement and a major rival of early

Buddhism and Jainism.[76]

Original scriptures of the Ājīvika school of

philosophy may once have existed, but these

are currently unavailable and probably lost.

Their theories are extracted from mentions of

Ajivikas in the secondary sources of ancient

Hindu Indian literature, particularly those of

Jainism and Buddhism which polemically

criticized the Ajivikas.[77] The Ājīvika school is

known for its Niyati doctrine of absolute

determinism (fate), the premise that there is no

free will, that everything that has happened, is

happening and will happen is entirely

preordained and a function of cosmic

principles.[77][78] Ājīvika considered the karma

doctrine as a fallacy.[79] Ājīvikas were

atheists[80] and rejected the authority of the

Vedas, but they believed that in every living

being is an ātman – a central premise of

Hinduism and Jainism.[81][82]

Ajñana

Ajñana was a Śramaṇa school of radical Indian

skepticism and a rival of early Buddhism and

Jainism. They held that it was impossible to

obtain knowledge of metaphysical nature or

ascertain the truth value of philosophical

propositions;[83] and even if knowledge was

possible, it was useless and disadvantageous

for final salvation. They were seen as sophists

who specialized in refutation without

propagating any positive doctrine of their own.

Jayarāśi Bhaṭṭa (fl. c. 800), author of the

skeptical work entitled Tattvopaplavasiṃha

("The Lion that Devours All Categories"/"The

Upsetting of All Principles"), has been seen as

an important Ajñana philosopher.[84]

Sikh philosophy

Main article: Sikh religious philosophy

Sikhism is an Indian religion developed by Guru

Nanak (1469–1539) in the Punjab region during

the Mughal Era. Their main sacred text is the

Guru Granth Sahib. The fundamental beliefs

include constant spiritual meditation of God's

name, being guided by the Guru instead of

yielding to capriciousness, living a

householder's life instead of monasticism,

truthful action to dharam (righteousness, moral

duty), equality of all human beings, and

believing in God's grace.[85][86] Key concepts

include Simran, Sewa, the Three Pillars of

Sikhism, and the Five Thieves.

Modern Indian philosophy

From left to right: Virchand Gandhi,

Anagarika Dharmapala, Swami

Vivekananda, (possibly) G. Bonet

Maury. Parliament of World

Religions, 1893

In response to colonialism and their contact

with Western philosophy, 19th century Indians

developed new ways of thinking now termed

Neo-Vedanta and Hindu modernism. Their

ideas focused on the universality of Indian

philosophy (particularly Vedanta) and the unity

of different religions. It was during this period

that Hindu modernists presented a single

idealized and united "Hinduism." exemplified by

the philosophy of Advaita Vedanta.[87] They

were also influenced by Western ideas.[88] The

first of these movements was that of the

Brahmo Samaj of Ram Mohan Roy (1772–

1833).[89] Swami Vivekananda (1863–1902)

was very influential in developing the Hindu

reform movements and in bringing the

worldview to the West.[90] Through the work of

Indians like Vivekananda as well as westerners

such as the proponents of the Theosophical

society, modern Hindu thought also had an

influence on western culture.[91]

The political thought of Hindu nationalism is

also another important current in modern

Indian thought. The work of Mahatma Gandhi,

Rabindranath Tagore, Aurobindo, Krishna

Chandra Bhattacharya and Sarvepalli

Radhakrishnan have had a large impact on

modern Indian philosophy.[92]

Jainism also had its modern interpreters and

defenders, such as Virchand Gandhi, Champat

Rai Jain, and Shrimad Rajchandra (well known

as a spiritual guide of Mahatma Gandhi).

Buddhist philosophies

Main articles: Buddhist philosophy and Buddhist ethics

The Buddhist Nalanda university and

monastery was a major center of

learning in India from the 5th century

CE to c. 1200.

Play media

You might also like

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5822)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1093)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (852)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (590)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (898)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (540)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (349)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (822)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (122)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (403)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- The Visions of Isobel Gowdie - Emma WilbyDocument619 pagesThe Visions of Isobel Gowdie - Emma WilbySharon Wazurka94% (18)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The Positive Version - Ten Offences Against The Holy NameDocument26 pagesThe Positive Version - Ten Offences Against The Holy NameDina-Anukampana DasNo ratings yet

- Reflection Paper On "Babette's Feast" - by Maria Grace, Ph.D.Document5 pagesReflection Paper On "Babette's Feast" - by Maria Grace, Ph.D.Monika-Maria Grace100% (3)

- BRAHMA SUTRAS - According To Sri Sankara Translated by Swami VireswaranandaDocument614 pagesBRAHMA SUTRAS - According To Sri Sankara Translated by Swami VireswaranandaEstudante da Vedanta100% (8)

- The Doctrine of Paticcasamuppada - Ven Mogok SayatawDocument105 pagesThe Doctrine of Paticcasamuppada - Ven Mogok SayatawBuddhaDhammaSangahNo ratings yet

- Answer Sheets 35 - 40 - 50 ItemsDocument4 pagesAnswer Sheets 35 - 40 - 50 ItemsNiña DyanNo ratings yet

- Ap Action Plan 2022-2028Document2 pagesAp Action Plan 2022-2028Niña DyanNo ratings yet

- Parents Teacher ClearanceDocument2 pagesParents Teacher ClearanceNiña DyanNo ratings yet

- List of Students UpdatedDocument2 pagesList of Students UpdatedNiña DyanNo ratings yet

- Mid Year Review Form For Proficient TeachersDocument11 pagesMid Year Review Form For Proficient TeachersNiña DyanNo ratings yet

- UPDATED Teachers Assignment 3RD EDITDocument28 pagesUPDATED Teachers Assignment 3RD EDITNiña DyanNo ratings yet

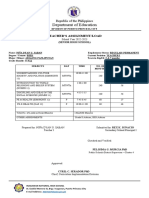

- Nina Saban Teacher's AssignmentDocument1 pageNina Saban Teacher's AssignmentNiña DyanNo ratings yet

- Safari - 7 May 2019 at 1:39 AMDocument1 pageSafari - 7 May 2019 at 1:39 AMNiña DyanNo ratings yet

- Elite Package Marketing PlanDocument30 pagesElite Package Marketing PlanNiña DyanNo ratings yet

- BibliographyDocument4 pagesBibliographyBruno DiasNo ratings yet

- The Seven Mountain Mandate - Andrei Van WykDocument4 pagesThe Seven Mountain Mandate - Andrei Van WykA vWNo ratings yet

- Hazrat Syedna Ahmed KabirDocument5 pagesHazrat Syedna Ahmed Kabirspider.xNo ratings yet

- Ben Chenoweth A Critique of Two Recent Interpretations of The Parable of The TalentsDocument157 pagesBen Chenoweth A Critique of Two Recent Interpretations of The Parable of The TalentsLazar PavlovicNo ratings yet

- Daily PrayersDocument66 pagesDaily PrayersShenphen Ozer100% (2)

- Augustine and City of GodDocument10 pagesAugustine and City of GodMario Cruz100% (1)

- A Study of Buddhist Bhaktism With Special Reference To The Esoteric BuddhismDocument5 pagesA Study of Buddhist Bhaktism With Special Reference To The Esoteric BuddhismomarapacanaNo ratings yet

- HSL Great White BrotherhoodDocument5 pagesHSL Great White BrotherhoodusrmosfetNo ratings yet

- Ad Gentes Vatican DecreeDocument34 pagesAd Gentes Vatican DecreeEdilbert ConcordiaNo ratings yet

- Kannada StotrasDocument16 pagesKannada StotrasAnonymous xKEjITvij2100% (2)

- Chikulupi Cha UsilamuDocument110 pagesChikulupi Cha UsilamuIslamHouseNo ratings yet

- Sermon Notes First Ecumenical Church Service 1 Sunday After Pentecost June 3, 2012Document3 pagesSermon Notes First Ecumenical Church Service 1 Sunday After Pentecost June 3, 2012api-180169039No ratings yet

- The DasabhumikasutraDocument3 pagesThe DasabhumikasutraAtul BhosekarNo ratings yet

- Introduction To Romans: by Ed Stevens - Then and Now Podcast - Oct 27, 2013Document37 pagesIntroduction To Romans: by Ed Stevens - Then and Now Podcast - Oct 27, 2013Marcosroso10No ratings yet

- Jesuit Vatican New World OrderDocument103 pagesJesuit Vatican New World OrderServant Of Truth100% (1)

- Importance of SacramentsDocument11 pagesImportance of SacramentsCrispin Nduu MuyeyNo ratings yet

- December Prayer Letter 2014 OfficialDocument2 pagesDecember Prayer Letter 2014 OfficialLuigi BellaNo ratings yet

- Gospel Wheel Verses - NKJV Gospel Wheel Verses - NKJV: God GodDocument1 pageGospel Wheel Verses - NKJV Gospel Wheel Verses - NKJV: God GodDanAcarNo ratings yet

- Comprehensive Reflection PaperDocument7 pagesComprehensive Reflection PaperKingPattyNo ratings yet

- Santeria PowerpointDocument13 pagesSanteria PowerpointTiseannaNo ratings yet

- Hypostatic UnionDocument11 pagesHypostatic Unionjesse_reichelt_10% (1)

- The Seven SacramentsDocument4 pagesThe Seven SacramentsAlfie AbaliliNo ratings yet

- Durga Pancharatnam DetailsDocument4 pagesDurga Pancharatnam DetailsSuresh IndiaNo ratings yet

- Church Leadership Connection: Mif #: 20449.AC0Document4 pagesChurch Leadership Connection: Mif #: 20449.AC0DannyCurvinNo ratings yet

- Augustine's Last Pneumatology: Michel René BarnesDocument3 pagesAugustine's Last Pneumatology: Michel René BarnesNjono SlametNo ratings yet