Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Decentralization Boon or Bane Roll No. P39103 Section-B

Decentralization Boon or Bane Roll No. P39103 Section-B

Uploaded by

sharad19960 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

12 views3 pagesThe document discusses political decentralization in India following the 73rd amendment to the constitution. This amendment led to the creation of gram panchayats, panchayat samitis, and zilla parishads to administer villages and districts. However, these local bodies face challenges due to a lack of independent revenue sources, which makes them dependent on state and central governments. For true decentralization, local bodies need more financial autonomy and clearly defined roles. The document also discusses issues like overlapping jurisdiction between local and state bodies, the need for coordination between various planning levels, and ensuring participation of all groups in local governance.

Original Description:

village level governance

Original Title

RDI on 20

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

DOCX, PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentThe document discusses political decentralization in India following the 73rd amendment to the constitution. This amendment led to the creation of gram panchayats, panchayat samitis, and zilla parishads to administer villages and districts. However, these local bodies face challenges due to a lack of independent revenue sources, which makes them dependent on state and central governments. For true decentralization, local bodies need more financial autonomy and clearly defined roles. The document also discusses issues like overlapping jurisdiction between local and state bodies, the need for coordination between various planning levels, and ensuring participation of all groups in local governance.

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as DOCX, PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Download as docx, pdf, or txt

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

12 views3 pagesDecentralization Boon or Bane Roll No. P39103 Section-B

Decentralization Boon or Bane Roll No. P39103 Section-B

Uploaded by

sharad1996The document discusses political decentralization in India following the 73rd amendment to the constitution. This amendment led to the creation of gram panchayats, panchayat samitis, and zilla parishads to administer villages and districts. However, these local bodies face challenges due to a lack of independent revenue sources, which makes them dependent on state and central governments. For true decentralization, local bodies need more financial autonomy and clearly defined roles. The document also discusses issues like overlapping jurisdiction between local and state bodies, the need for coordination between various planning levels, and ensuring participation of all groups in local governance.

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as DOCX, PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Download as docx, pdf, or txt

You are on page 1of 3

Decentralization boon or bane

Roll no. P39103 Section- B

April 24, celebrated in India as national panchayat raj divas. The 73rd amendment in constitution

paved the road for decentralization of political structure in India which was long envisioned by the

constitution makers of India when India got its freedom. The amendment resulted into creation of

gram panchayat, panchayat samiti and Zilla parishad. Gram- panchayats were for the village

administration consisting of 5 or more gram panchayat members and a sarpanch. Sarpanch is a

head of a gram panchayat. Panchayat Simitis which is one for each tehsil consist of panchayat

samite members and committees for water education infrastructure and other. Each committee is

headed by a panchayat samiti member. Zilla parishad is highest body in panchayat raj which is one

for each district and have members depending on population. This decentralization of political

structure was done to bridge the gap between development and rural areas these structures were

created specifically to cater to the rural areas where rampant corruption and top down approach

from bureaucrats was main obstacle in achieving the poorna swaraj as promised by political

leaders.

Analyzing today whether these political structures are doing public good or not, are they

have become really beneficial to rural areas or not is the question we will try to answer. Let’s see

the challenges faced by these structures. Gram panchayat, panchayat samiti and Zilla parishad do

not have a proper revenue generation mechanism. Gram panchayat collects the land rent from the

villagers and water bill but these two are not enough to run the gram panchayat because of this

gram panchayat has to look towards the funding it receives from the state government and central

government. Panchayat samiti and Zilla parishad both of them do not have the proper revenue

generation mechanism this hampers the local level decision making and these local bodies have to

be dependent on the state and central government which makes the decision making and policy

implementation a top down approach. Due to lack of proper revenue generation mechanism these

local bodies cannot take development work on their own also they cannot design the policies which

are suitable to local condition. Gram panchayat receives annual fund. These funds are mostly

related to particular schemes or the most of the funds spent on road construction as often these

funds are inadequate year on year these funds goes spending on roads. Same set of problems are

faced by the Zilla parishad and panchayat samiti.

If the development planning process has to be decentralised down to the panchayat

level, this should go hand in hand with the Government of India reducing the range and volume of

the centrally sponsored plan schemes, and allowing the State Governments to function freely in

their allotted spheres. It should further be accompanied by suitable devolution of financial

resources between them and from them to the panchayats. PRIs may lose interest in the preparation

of plans unless adequate funds are provided for meeting the expenditure. Therefore, there is a need

to increase the panchayat’s area of discretion in spending their own funds and to ensure that the

sectoral schemes of the line departments are coordinated and integrated by them. The functions to

be performed at each level of panchayats must be clearly identified. The implementation of such

functions would call for simultaneous amendments to subject-matter legislation to enable

assumption of such functions by the panchayats. A clear delegation of powers may have to be

given in matters not covered by legislation such as antipoverty programmes, preparation of local

plans, construction of roads, etc. The panchayats must be given specific powers to pool resources

and undertake integrated local development. There should be no requirement to get any approval

from higher levels of bureaucracy in the department of Panchayati Raj or in any other Government

department.

The problem of overlapping functions and jurisdiction between the State

Governments and the PRIs need not necessarily be seen as reflecting an unsatisfactory situation

with potential conflicts and confusion. The present situation actually presents a challenge to our

polity which can be met by evolving systems of synergy between different levels of governance.

We already have cooperative federalism evolved in this country where the Central Government

formulates various schemes and shapes policy relating to several State subjects besides providing

funds to implement such schemes. Another issue that has the potential of conflict between the State

Government and the PRIs relates to the integration of district plans with the State and national

plans. Admittedly, the national plans have several objectives, which can be achieved only in the

long run whereas district plans reflect the immediate needs of the people, which may sometimes

overlook the long term need. Presently, the Planning Commission does the work of coordinating

the State plans with the national plan. On this basis, Five Year Plans and the annual plans are

finalised. A similar process will have to be adopted for approving the district plans at the State

level. This could perhaps be done either by the State Planning Department or by setting up a State

Development Council which will help in establishing the necessary coordination at all levels both

in physical and financial terms. Availability of functionaries is as important as the provision of

functions and funds to the PRIs.

The overlapping control of PRIs and State Government over

the administrative machinery for implementing development programmes entrusted to the PRIs

reduces the functional autonomy of all these bodies to a considerable extent. In addition, the

panchayat functionaries, who are on deputation to these institutions from the State Government,

as in Karnataka, may continue to regard themselves as government servants only and may tend to

look up to their State level seniors than the elected leaders of the panchayats for guidance and

leadership. This situation is further compounded in some States by the control exercised by the

legislators over local administration through the mechanism of annual transfer of officials which

is effected by the State administration largely at the initiative of the legislators and the other State

level political leaders. This practice of large scale official transfers at the initiative of legislators

can seriously undermine the functional autonomy of PRIs, besides contributing to the dilution of

administrative accountability. A series of changes would therefore be required in the

administrative arrangements for programme planning and implementation in respect of the

schemes and programmes transferred to the PRIs for implementation. Many States have, over a

period of time, set up a number of parastatal organisations to meet the self-employment and

economic development requirements of vulnerable sections of society. Some of these institutions

have an in-built bias for social justice. For instance, the Finance Development and Housing

Corporations set up for the Scheduled Castes, the Scheduled Tribes, the Backward Classes, the

minorities and women, both at the Central and State levels invariably deal with subjects which

have now been assigned to the PRIs. These institutions were basically conceived for mobilising

finances from leading development institutions such as the NABARD, the Land Development

Banks, etc. Budgetary grants are also made in favour of these institutions by the State and Central

Government to facilitate mobilisation of further finances from commercial institutions, using these

provisions as margin or seed money.

The caste favoritism has been practicing in the village institutions in

India, this leads to the unstable participation of the lower caste people. It is one of the unavoidable

questions while talking about political decentralization; can we combine decentralization and

participatory government? Participatory government means not only few can participate in the

governing process. To Gandhi it is the participation of all in the region of the government.

According to him people’s participation is a must in proposing political decentralization. He

believed that it is possible to attain his aim of the classless society through it. To him

decentralization is the one of the best means to promote the people’s participation in governmental

affairs. The power transformation without accountable participation is useless, at the same time

the promotion of people’s participation without adequate power is empty.

There by we can conclude that the concept of political

decentralization and participation are very relevant and co-operative to each other. Gandhi’s

concept of democratic decentralization especially the village government (Panchayat raj) brings

adequate power to the people by their participation. That’s why it is called as the democracy within

democracy. But there are some hurdles for its success in India. As I have already said that, India

is the multifaceted country, it’s most crucial and dangerous complexity is rested in the Indian caste

system. It is the biggest obstacle against his aim of classless and decentralized society. All these

challenges remain still today’s India. Our policy makers with aim of a participatory government

implemented PRI it’s our responsibility to protect and make function them as missioned by policy

makers.

You might also like

- Legal Advice Letter SampleDocument4 pagesLegal Advice Letter SampleMichelle Hatol100% (5)

- Theoretical Framework SampleDocument8 pagesTheoretical Framework SampleRey PeregilNo ratings yet

- MRA Questionnaire On Online News AppDocument6 pagesMRA Questionnaire On Online News Appsharad1996No ratings yet

- En Banc Resolution On GR Nos. 234359 (Almora v. Dela Rosa) and 234484 (Daño v. PNP)Document13 pagesEn Banc Resolution On GR Nos. 234359 (Almora v. Dela Rosa) and 234484 (Daño v. PNP)RapplerNo ratings yet

- Drafting of Criminal Bail Application in Non-Bailable OffencesDocument14 pagesDrafting of Criminal Bail Application in Non-Bailable OffencesBharat JoshiNo ratings yet

- Sample Fellowship Offer LetterDocument2 pagesSample Fellowship Offer LetterandviraniNo ratings yet

- Private Equity Shareholders Agreements PresentationDocument23 pagesPrivate Equity Shareholders Agreements Presentationmayor78No ratings yet

- Democratic Decentralization in IndiaDocument18 pagesDemocratic Decentralization in IndiaMadhurima MukherjeeNo ratings yet

- Mpa 16 PDFDocument12 pagesMpa 16 PDFFirdosh Khan100% (1)

- Panchayati Raj Institutions and Participative DemocracyDocument6 pagesPanchayati Raj Institutions and Participative DemocracyYuvraj GogoiNo ratings yet

- Public Administration Unit-91 Problems and Prospects of Panchayati RajDocument8 pagesPublic Administration Unit-91 Problems and Prospects of Panchayati RajDeepika SharmaNo ratings yet

- Command Area Development ProgrammeDocument12 pagesCommand Area Development ProgrammeRaj Thilak SNo ratings yet

- Unit 21 Capacity Building of Grassroots Functionaries: 21.0 Learning OutcomeDocument11 pagesUnit 21 Capacity Building of Grassroots Functionaries: 21.0 Learning OutcomeC SathishNo ratings yet

- Unit 7 Panchayati RajDocument14 pagesUnit 7 Panchayati RajVirendra PratapNo ratings yet

- Public Administration Unit-80 District PlanningDocument11 pagesPublic Administration Unit-80 District PlanningDeepika SharmaNo ratings yet

- The Panchayat Raj InstitutionDocument6 pagesThe Panchayat Raj InstitutionUPASANA GARGNo ratings yet

- Problem of Local Govt. System: Absence of Real AutonomyDocument2 pagesProblem of Local Govt. System: Absence of Real Autonomytalha hasibNo ratings yet

- Asoka Mehta Committee Report PDFDocument22 pagesAsoka Mehta Committee Report PDFck_chandrasekaranNo ratings yet

- DecentralisationDocument3 pagesDecentralisationtanuNo ratings yet

- Democratic DecentralisationDocument2 pagesDemocratic DecentralisationPrashantNo ratings yet

- Social Welfare and DevelopmentDocument10 pagesSocial Welfare and DevelopmentDebanjanaChakrabortyNo ratings yet

- Decentralised Planning KarnatakaDocument2 pagesDecentralised Planning KarnatakaP B PatilNo ratings yet

- Unit-11 Impact of Decentralised DevelopmentDocument14 pagesUnit-11 Impact of Decentralised DevelopmentsumanpuniaNo ratings yet

- Communication For Panchayat Raj SystemDocument22 pagesCommunication For Panchayat Raj SystemConcave StudioNo ratings yet

- Chap 01Document2 pagesChap 01Sugi MNo ratings yet

- Politics of Urban Development in India: Dr. Purobi SharmaDocument8 pagesPolitics of Urban Development in India: Dr. Purobi SharmaAr Aayush GoelNo ratings yet

- L17 Crux F Grassroot Democracy 2 and Federalism 1 1668389953Document30 pagesL17 Crux F Grassroot Democracy 2 and Federalism 1 1668389953kunalNo ratings yet

- Effectiveness of Panchayati Raj Systems, Problems and National DeclarationDocument3 pagesEffectiveness of Panchayati Raj Systems, Problems and National DeclarationRana GurtejNo ratings yet

- Ps NotesDocument13 pagesPs Noteslavanyaawasthi24091No ratings yet

- Mpa 16Document7 pagesMpa 16Babu Nair100% (1)

- 73rd AmendmentDocument26 pages73rd AmendmentSakshiNo ratings yet

- Indian Political System: Centre-State RelationDocument18 pagesIndian Political System: Centre-State RelationJason DunlapNo ratings yet

- Book For Theme Based GPDP Prepration Process Document - English - Compressed - 1680512145656Document51 pagesBook For Theme Based GPDP Prepration Process Document - English - Compressed - 1680512145656jhaakshay894No ratings yet

- Policy Designing and ImplementationDocument14 pagesPolicy Designing and Implementationgokulramlal06No ratings yet

- Grassroot Planning - From Conceptualisation To Institutionalisation - A Case Study of Madhya Pradesh, IndiaDocument10 pagesGrassroot Planning - From Conceptualisation To Institutionalisation - A Case Study of Madhya Pradesh, IndiaYogesh MahorNo ratings yet

- An Action Programme For The Eleventh Five Year Plan SummaryDocument3 pagesAn Action Programme For The Eleventh Five Year Plan Summaryabcdef1985No ratings yet

- 15th Finance Commission - Review & RecommendationsDocument6 pages15th Finance Commission - Review & RecommendationsSaurabh SinhaNo ratings yet

- Local Government Purpose Structure and RDocument14 pagesLocal Government Purpose Structure and RA R ShuvoNo ratings yet

- The Concept of Engaged Governance.: Develop A Given People You Can Only Help Them To Develop Themselves. As ADocument5 pagesThe Concept of Engaged Governance.: Develop A Given People You Can Only Help Them To Develop Themselves. As Aapi-16508427No ratings yet

- Status of PeopleDocument16 pagesStatus of PeopleThingtlangpa PachuauNo ratings yet

- Local Self-Government in India: An Overview: Dr. D RajasekharDocument8 pagesLocal Self-Government in India: An Overview: Dr. D RajasekharRaman PatelNo ratings yet

- Decentralization Problem in MalaysiaDocument5 pagesDecentralization Problem in MalaysiaMuhammad Irffan SabriNo ratings yet

- This Content Downloaded From 157.39.94.180 On Tue, 24 Nov 2020 08:49:54 UTCDocument11 pagesThis Content Downloaded From 157.39.94.180 On Tue, 24 Nov 2020 08:49:54 UTCSanad AroraNo ratings yet

- Public Policy SpeachDocument4 pagesPublic Policy SpeachKhushi SikkaNo ratings yet

- THE NEWS July 25, 2011 Money Matters Maximising Benefits: by DR Ishrat HusainDocument3 pagesTHE NEWS July 25, 2011 Money Matters Maximising Benefits: by DR Ishrat HusainABM2014No ratings yet

- Peoples EstimateDocument53 pagesPeoples Estimatedorababu2007No ratings yet

- Panchayat Raj System-Dr - Rashmi v.Document7 pagesPanchayat Raj System-Dr - Rashmi v.RakeshNo ratings yet

- Governance and DevelopmentDocument19 pagesGovernance and DevelopmentFenil PatelNo ratings yet

- Review of 30 Years of Panchayati Raj InstitutionsDocument6 pagesReview of 30 Years of Panchayati Raj InstitutionsKadashettihalli SatishNo ratings yet

- 3348 9657 1 PBDocument15 pages3348 9657 1 PBHusniNo ratings yet

- Social Issues & Social Justice Hand Notes by Sweta Mam-1Document440 pagesSocial Issues & Social Justice Hand Notes by Sweta Mam-1Socio-political PrakashNo ratings yet

- Synopsis 20-8-12Document11 pagesSynopsis 20-8-12Seema ChelatNo ratings yet

- Role of Civil Services in A DemocracyDocument9 pagesRole of Civil Services in A DemocracyVenki VenkateshNo ratings yet

- SamarthSansar - 218099 - Economics 1Document10 pagesSamarthSansar - 218099 - Economics 1samarth sansarNo ratings yet

- CA 1 GovernanceDocument8 pagesCA 1 GovernanceNikhil mosesNo ratings yet

- Upsc Gs Mains Paper - 2: HintsDocument14 pagesUpsc Gs Mains Paper - 2: HintsRatika AroraNo ratings yet

- M. A Pub. Admn. IV Sem (404) Stste Control Over Panchayati Raj Institution in M. PDocument12 pagesM. A Pub. Admn. IV Sem (404) Stste Control Over Panchayati Raj Institution in M. Pmsjantabrickfield2022No ratings yet

- Constitutional Base For Panchayati Raj in IndiaDocument10 pagesConstitutional Base For Panchayati Raj in IndiaShilpa SmileyNo ratings yet

- Social - Sansad Gram Adarsh YojanaDocument22 pagesSocial - Sansad Gram Adarsh YojanaLîjö JôhñNo ratings yet

- 6th Local GovernanceDocument47 pages6th Local Governancegopichand456No ratings yet

- Improving Governance: All Rights ReservedDocument4 pagesImproving Governance: All Rights Reservedscramjet32No ratings yet

- Revenue Generation at Panchayat Level - FinalDocument13 pagesRevenue Generation at Panchayat Level - Finaladiti kaviwalaNo ratings yet

- 73rd and 74th Amendments in Indian ConstitutionDocument5 pages73rd and 74th Amendments in Indian ConstitutionSweta SharmaNo ratings yet

- Chapter - V Summary and ConclusionDocument16 pagesChapter - V Summary and ConclusionAnjaliNo ratings yet

- Social Accountability In Ethiopia: Establishing Collaborative Relationships Between Citizens and the StateFrom EverandSocial Accountability In Ethiopia: Establishing Collaborative Relationships Between Citizens and the StateNo ratings yet

- #1 e Scan ProtectedDocument1 page#1 e Scan Protectedsharad1996No ratings yet

- #0 e Scan ProtectedDocument1 page#0 e Scan Protectedsharad1996No ratings yet

- Qarm Assignment-1 Section C: Group MembersDocument8 pagesQarm Assignment-1 Section C: Group Memberssharad1996No ratings yet

- HW11 Team6 BUAN6398Document4 pagesHW11 Team6 BUAN6398sharad19960% (1)

- VDR PPT 1Document23 pagesVDR PPT 1sharad1996No ratings yet

- Age Dependency Ratio IndiaDocument3 pagesAge Dependency Ratio Indiasharad1996No ratings yet

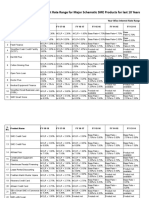

- Interest Rates For Last 10 Yr For Major SME ProductsDocument6 pagesInterest Rates For Last 10 Yr For Major SME Productssharad1996No ratings yet

- 053 BANAT v. COMELEC 595 SCRA 477Document24 pages053 BANAT v. COMELEC 595 SCRA 477JNo ratings yet

- Bureau of CorrectionsDocument26 pagesBureau of CorrectionsJvnRodz P GmlmNo ratings yet

- Invitation Letter PDFDocument2 pagesInvitation Letter PDFgogo1No ratings yet

- BDO - Secretary's CertificateDocument2 pagesBDO - Secretary's CertificateMiguel Rey Ramos100% (2)

- Lesson 5Document10 pagesLesson 5Jane AntonioNo ratings yet

- Differences of Diplomacy, Litigation, Arbitration, and AdrDocument2 pagesDifferences of Diplomacy, Litigation, Arbitration, and AdrUtty F. SeieiNo ratings yet

- Law of Torts: Nuisance-Concept and Defences in An Action For NuisanceDocument15 pagesLaw of Torts: Nuisance-Concept and Defences in An Action For NuisanceGayatri MisraNo ratings yet

- Petition For Writ of Mandate With ExhibitsDocument256 pagesPetition For Writ of Mandate With ExhibitsKelly Aviles100% (3)

- PolSci 1 PRELIM MODULEDocument15 pagesPolSci 1 PRELIM MODULEJohara BayabaoNo ratings yet

- Notes On Labor Standards: San Beda University - College of LawDocument119 pagesNotes On Labor Standards: San Beda University - College of LawFLA100% (1)

- Student Confidentiality Agreement 2Document2 pagesStudent Confidentiality Agreement 2trellon_devteamNo ratings yet

- Employer-Employee Relationships: Republic of The Philippines Peǹfrancia Avenue, Naga City S / y 2 0 1 8 - 2 0 1 9Document24 pagesEmployer-Employee Relationships: Republic of The Philippines Peǹfrancia Avenue, Naga City S / y 2 0 1 8 - 2 0 1 9Crisby PachionNo ratings yet

- TradeunionDocument41 pagesTradeunionShashi ShekharNo ratings yet

- Indian Evidence ActDocument73 pagesIndian Evidence Actsumitkumar_sumanNo ratings yet

- NehaDocument5 pagesNehaVishal ChoudharyNo ratings yet

- Local Government Code of The PhilippinesDocument3 pagesLocal Government Code of The PhilippinesBon Jovi RosarioNo ratings yet

- Codilla Vs MartinezDocument3 pagesCodilla Vs MartinezMaria Recheille Banac KinazoNo ratings yet

- Metropolitan Traffic Command vs. GonongDocument8 pagesMetropolitan Traffic Command vs. GonongXryn MortelNo ratings yet

- Competitive Examination (CSS) - 2019 PDFDocument7 pagesCompetitive Examination (CSS) - 2019 PDFMuhammad Saad Bin UbaidNo ratings yet

- 16.2 Appointment Letter SampleDocument2 pages16.2 Appointment Letter SampleCathy DugganNo ratings yet

- Trans-Asia Shipping Lines, Inc. v. CADocument3 pagesTrans-Asia Shipping Lines, Inc. v. CABen EncisoNo ratings yet

- Cantimbuhan v. Cruz Jr. G.R. No. L-51813-14Document4 pagesCantimbuhan v. Cruz Jr. G.R. No. L-51813-14Gigi HadidmybestNo ratings yet

- LaborlawupdatesDocument129 pagesLaborlawupdatesAngel UrbanoNo ratings yet

- Samala v. CADocument8 pagesSamala v. CAApril IsidroNo ratings yet

- Green Courts PaperDocument6 pagesGreen Courts PaperKrystalynne AguilarNo ratings yet