Professional Documents

Culture Documents

04 Handout 1

04 Handout 1

Uploaded by

alhene floresCopyright:

Available Formats

You might also like

- Introduction To CommunicationDocument38 pagesIntroduction To Communicationricha singhNo ratings yet

- W14 - Worksheet 1 (GEC 106)Document3 pagesW14 - Worksheet 1 (GEC 106)obrie diazNo ratings yet

- Unit 1 - Communicate in A Business Environment NVQDocument9 pagesUnit 1 - Communicate in A Business Environment NVQSadiq Ebrahim DawoodNo ratings yet

- Assessment 2 Lesson PlanDocument15 pagesAssessment 2 Lesson Planapi-403689756No ratings yet

- Dia SsssssDocument11 pagesDia SsssssJahna ManinangNo ratings yet

- Communication Concept by MeDocument14 pagesCommunication Concept by MeGaurav SinghNo ratings yet

- Importance: The Significance of CommunicationDocument4 pagesImportance: The Significance of Communicationmisael gizacheNo ratings yet

- Bj0050 SLM Unit 02Document16 pagesBj0050 SLM Unit 02shalakagadgilNo ratings yet

- Communication Nature, Functions and ScopeDocument25 pagesCommunication Nature, Functions and ScopebasuNo ratings yet

- Business Communication Module (Repaired)Document117 pagesBusiness Communication Module (Repaired)tagay mengeshaNo ratings yet

- BTTM 304Document264 pagesBTTM 304akfanNo ratings yet

- Assignment of Effective CommunicationDocument4 pagesAssignment of Effective CommunicationMd. Rashed Mahbub Sumon100% (4)

- Business Communication in An MNC in BD, UnileverDocument20 pagesBusiness Communication in An MNC in BD, UnileverAbdullah Al Mahmud33% (3)

- Business Com. Chapter 4Document43 pagesBusiness Com. Chapter 4Seida AliNo ratings yet

- Communication ChannelsDocument11 pagesCommunication ChannelsSheila692008No ratings yet

- Intro To BCDocument11 pagesIntro To BCpushpender gargNo ratings yet

- Managerial Communications: 4 Year Business AdministrationDocument15 pagesManagerial Communications: 4 Year Business Administrationاحمد صلاحNo ratings yet

- CommunicationDocument27 pagesCommunicationNisha MalhotraNo ratings yet

- Assignment On Business CommunictionDocument2 pagesAssignment On Business CommunictionBro AdhikariNo ratings yet

- Assignment On Business CommunictionDocument2 pagesAssignment On Business CommunictionBro AdhikariNo ratings yet

- Planning Organizing Staffing Directing Controlling: Oral CommunicationDocument9 pagesPlanning Organizing Staffing Directing Controlling: Oral CommunicationmitsriveraNo ratings yet

- All UnitsDocument104 pagesAll UnitsKarthick RajaNo ratings yet

- Chapter II - Administrative and Business CommunicationDocument13 pagesChapter II - Administrative and Business CommunicationYIBELTAL ANELEYNo ratings yet

- Assignment - Introduction To Business CommunicationDocument13 pagesAssignment - Introduction To Business CommunicationRafaNo ratings yet

- Block 4 MCO 1 Unit 4Document17 pagesBlock 4 MCO 1 Unit 4Tushar SharmaNo ratings yet

- Module 1 WORD1Document10 pagesModule 1 WORD1Kristine GonzagaNo ratings yet

- The Tips College of Commerce: Q.1 Define Communication? Also Explain Its Importance?Document48 pagesThe Tips College of Commerce: Q.1 Define Communication? Also Explain Its Importance?Muhammad AkramNo ratings yet

- Business Cummunication Security MGNTDocument50 pagesBusiness Cummunication Security MGNTJonathan SmokoNo ratings yet

- BC PowerPoint PresentationDocument164 pagesBC PowerPoint PresentationMelkamu TuchamoNo ratings yet

- Communication in OrganizationDocument11 pagesCommunication in OrganizationAsim IkramNo ratings yet

- The Discipline of CommunicationDocument42 pagesThe Discipline of CommunicationNadia Caoile IgnacioNo ratings yet

- BC Unit-1Document20 pagesBC Unit-1AbinashNo ratings yet

- Business Communication - Unit 1 & 2Document93 pagesBusiness Communication - Unit 1 & 2VedikaNo ratings yet

- Principles of Management Unit 5Document31 pagesPrinciples of Management Unit 5ajarmohamed2003No ratings yet

- Unit 1 Communication in The Work PlaceDocument27 pagesUnit 1 Communication in The Work PlaceParthiban PartNo ratings yet

- Industrial Management NotesDocument66 pagesIndustrial Management NotesLearnmore MakwangudzeNo ratings yet

- Nature and Process of CommunicationDocument27 pagesNature and Process of CommunicationBiyas DattaNo ratings yet

- CH 1Document5 pagesCH 1rozina seidNo ratings yet

- Communication Strategies: Description Required Activity Making It WorkDocument7 pagesCommunication Strategies: Description Required Activity Making It WorkEvan CaldwellNo ratings yet

- 03 Chapter 3 - Communications, Pp. 39-48Document10 pages03 Chapter 3 - Communications, Pp. 39-48nforce1No ratings yet

- Bcps Notes 16-17 (II Sem)Document48 pagesBcps Notes 16-17 (II Sem)karamthota bhaskar naikNo ratings yet

- Fed413 - Communications in Educational OrganisationsDocument4 pagesFed413 - Communications in Educational OrganisationsIbrahm ShosanyaNo ratings yet

- Commonly". Therefore, The Word Communication Means Sharing of Ideas, Messages and WordsDocument50 pagesCommonly". Therefore, The Word Communication Means Sharing of Ideas, Messages and WordsMohammed Demssie MohammedNo ratings yet

- Unit 4 PPBMDocument8 pagesUnit 4 PPBMkumaryadavv866No ratings yet

- Factors Influencing Communication in Organizations Research PaperDocument18 pagesFactors Influencing Communication in Organizations Research PaperGUDINA MENGESHA MEGNAKANo ratings yet

- Importance of CommunicationDocument4 pagesImportance of CommunicationTramserNo ratings yet

- 2-Communication - What Is A Communication BreakdownDocument8 pages2-Communication - What Is A Communication BreakdownS.m. ChandrashekarNo ratings yet

- 3 Chapter V-CONCEPT-ON-ORGANIZATIONAL-MANAGEMENT-finalDocument20 pages3 Chapter V-CONCEPT-ON-ORGANIZATIONAL-MANAGEMENT-finalMariane DacalanNo ratings yet

- BC NotesDocument11 pagesBC NotesMeenakshi RajakumarNo ratings yet

- INTERPERSONAL AND ORGANIZATIONAL CommDocument14 pagesINTERPERSONAL AND ORGANIZATIONAL CommGeejay alemanNo ratings yet

- Communication 1st Unit - CompleteDocument17 pagesCommunication 1st Unit - CompleteAnuj SaxenaNo ratings yet

- Employability Final NotesDocument11 pagesEmployability Final NotesAurelia NkongeNo ratings yet

- Communication Skills For Business Task 1Document14 pagesCommunication Skills For Business Task 1maadjei059No ratings yet

- Bhmaecc IIDocument171 pagesBhmaecc IIAnkit Kumar JainNo ratings yet

- PR NotesDocument12 pagesPR NotesMarija DambrauskaitėNo ratings yet

- BCSS Material FinalDocument123 pagesBCSS Material FinalMurthyNo ratings yet

- Communications in OrganisationsDocument11 pagesCommunications in Organisationsdaniel plescaNo ratings yet

- COMMUNICATON-Abebe Yirdaw 2007Document13 pagesCOMMUNICATON-Abebe Yirdaw 2007yirgalemle ayeNo ratings yet

- MTP Supplemental Notes 3Document5 pagesMTP Supplemental Notes 3Kashae JohnsonNo ratings yet

- Communication NotesDocument12 pagesCommunication Notesaniketavaidya66No ratings yet

- Effective Teamwork - Embracing Differences, Optimizing Meetings, And Achieving Team Success: An Introductory Detailed GuideFrom EverandEffective Teamwork - Embracing Differences, Optimizing Meetings, And Achieving Team Success: An Introductory Detailed GuideNo ratings yet

- Community Health Nursing ProcessDocument54 pagesCommunity Health Nursing ProcessAndrea Monique GalasinaoNo ratings yet

- Grade 1 Social Studies Curriculum PDFDocument6 pagesGrade 1 Social Studies Curriculum PDFhlariveeNo ratings yet

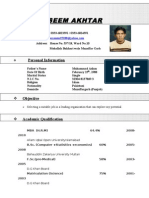

- Waseem Akhtar: Personal InformationDocument5 pagesWaseem Akhtar: Personal InformationWaseem Akhtar GhouriNo ratings yet

- Chapter 9-10 PDFDocument22 pagesChapter 9-10 PDFjey jeyd88% (8)

- Assessment of Community Support For PublDocument136 pagesAssessment of Community Support For Publjomex tundexNo ratings yet

- City Builder (11-19-2020)Document245 pagesCity Builder (11-19-2020)vaneb28540150% (2)

- RQM Assignment 3Document6 pagesRQM Assignment 3nicolekhella1No ratings yet

- 2015 Annual ReportDocument36 pages2015 Annual ReportJohn Humphrey Centre for Peace and Human RightsNo ratings yet

- Community Engagement Officer Cover LetterDocument6 pagesCommunity Engagement Officer Cover Lettereljaswrmd100% (1)

- 10 Jurnal LuarDocument16 pages10 Jurnal LuarAji PangestuNo ratings yet

- Nogor-Haat Reimagining An Urban Marketplace As The Neighborhood SquareDocument88 pagesNogor-Haat Reimagining An Urban Marketplace As The Neighborhood SquareSahar ZehraNo ratings yet

- Public Relation EnglishDocument67 pagesPublic Relation EnglishGargiRanaNo ratings yet

- Community Needs Assessment Survey GuideDocument19 pagesCommunity Needs Assessment Survey GuideshkadryNo ratings yet

- EDUC 101 Syllabus EDE A BDocument13 pagesEDUC 101 Syllabus EDE A BJoseph Gabriel EstrellaNo ratings yet

- Kaiserain G. Arante Humss #CoopfamDocument32 pagesKaiserain G. Arante Humss #Coopfamren renteNo ratings yet

- Antonio, Jaymark C.: College of Teacher Education and Human SciencesDocument2 pagesAntonio, Jaymark C.: College of Teacher Education and Human SciencesMark Anthony AntonioNo ratings yet

- Singapore - Housing Practise SeriesDocument90 pagesSingapore - Housing Practise SeriesMinhHyNo ratings yet

- Pisan CommunityDocument1 pagePisan CommunityEmilie Caja100% (1)

- FINAL Health Education SettingsDocument18 pagesFINAL Health Education SettingsClarisse Santiago100% (1)

- Technology, Pedagogy and Education Reflections On The Accomplishment of What Teachers Know, Do and Believe in A Digital Age LovelessDocument17 pagesTechnology, Pedagogy and Education Reflections On The Accomplishment of What Teachers Know, Do and Believe in A Digital Age LovelessTom Waspe Teach100% (1)

- National Highway, San Pedro, Laguna: San Francisco de Sales SchoolDocument4 pagesNational Highway, San Pedro, Laguna: San Francisco de Sales SchoolRaiza CabreraNo ratings yet

- The Social and Economic Value of Adult Grassroots Football in EnglandDocument131 pagesThe Social and Economic Value of Adult Grassroots Football in EnglandAwseome Vaibhav SahrawatNo ratings yet

- 2 Smith Studies in Social Justice Human Rights CitiesDocument22 pages2 Smith Studies in Social Justice Human Rights CitiesmkrNo ratings yet

- Revised Hematology Course Syllabus Aug 2, 2020Document11 pagesRevised Hematology Course Syllabus Aug 2, 2020Edna Uneta Robles100% (1)

- Competency Framework For TeachersDocument48 pagesCompetency Framework For TeachersMimi AringoNo ratings yet

- Zoom Ice Breaking Idea ViDocument5 pagesZoom Ice Breaking Idea ViWIBER ChapterLampungNo ratings yet

- New Defence PolicyDocument40 pagesNew Defence PolicyStuff NewsroomNo ratings yet

- 12community Outreach Program Understanding The Concepts and Principles of Community ImmersionDocument14 pages12community Outreach Program Understanding The Concepts and Principles of Community ImmersionKayla ParanNo ratings yet

04 Handout 1

04 Handout 1

Uploaded by

alhene floresOriginal Description:

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

04 Handout 1

04 Handout 1

Uploaded by

alhene floresCopyright:

Available Formats

SH1720

Methodologies and Approaches of Community Actions and Involvements Across

Disciplines

Settings, Processes, and Tools in the Discipline of Communication

Communication Settings

Government

Government communication can be defined as all the activities of public sector institutions and

organizations targeted to convey and share information, mainly for presenting and explaining

important government decisions and actions. It is also used for promotion of the legitimacy of

interventions, defending recognized values, and helping to keep social bonds.

Government communication concerns government institutions, which are government’s, courts,

auditor general’s office, etc., as well as the public-sector organizations. Viewed in terms of an

organized process, government communication includes all formal activities, whether written or

oral, regardless of the support used, and involves either interpersonal communication, a specific

group of people, or an undefined body of recipients or mass.

There is a general distinction between the active government communication and the passive

public communication. Active communication refers to activities provided, unsolicited, and

organized to the public or specific target groups by the authorities and the administration. MOst

communication activities by the government are said to be active for they are planned, organized,

and financed. On the other hand, passive communication refers to the information transmitted by

the administration to those who ask for it under the provisions of access to information laws now

current in most countries.

Civil Society

The communication process in society has three (3) functions.

1. Surveillance of the environment – it is the disclosing of threats and opportunities affecting

the value position of the community and of the component parts within it.

2. Correlation of the components of the society in making a response to the environment

3. Transmission of the social inheritance

In society, the processes of communication show special characteristics when the ruling is afraid

of the internal and external environment.

In gauging the efficiency of communication in any given context, it is necessary to consider the

values at stake, and the identity of the group whose position is examined. In democratic societies,

rational choices depend on enlightenment, which in turn depends upon communication; and

especially upon the equivalence of attention among leaders, experts, and regular members.

Private Sector

In an organization, informal and formal communications are used and many pathways, channels,

or media can be used to convey messages within an organization.

When sending a message within an organization, we need to consider channel, message type, and

audience or target. Choosing the right channel to get a certain message through a certain audience

can be more difficult that is first apparent according to Philip Clampitt in his book, communicating

for managerial effectiveness.

04 Handout 1 *Property of STI

Page 1 of 5

SH1720

The Communication Process

The function of the elements of the promotional mix is to communicate, so promotional planners

must understand the communication process.

This process can be very complex. Successful marketing communications depend on several

factors, including the nature of the message, the audience’s interpretation of it, and the

environment in which it is received. For effective communication to occur, the sender must encode

a message in such a way that it will be decoded by the receiver in an intended manner. Feedback

from the receiver helps the sender determine whether proper decoding has occurred or whether

noise has interfered with the communication process.

http://blogs.articulate.com/rapid-elearning/how-do-you-communicate-with-your-e-learners/

Elements of Communication

Source/Sender – the person or organization that has information to share

Receiver – person(s) with whom the sender is sharing thoughts

Message – the information the source hopes to convey

Channel – method by which the communication travels from source to receiver

Encoding – putting thoughts, ideas, or information into symbolic form

Decoding – transforming the sender's message back into thought

Response - receiver’s reactions after seeing, hearing, or reading the message

Feedback – part of the receiver’s response communicated back to the sender

Noise – unplanned distortion or interference

Tools of Communication

1. A memo is a poor choice while a small group meeting is a better choice in a situation where

a midsize construction firm wants to announce a new employee benefit program. Some

employees may have literacy problems. Synchronous communication means

communication sent and received at the same time.

2. The phone is a poor choice while email or voicemail is a better choice in a situation where

a manager wishes to confirm a meeting time with 10 employees (because there is no need

to use a rich and synchronous medium for a simple message).

3. Interpersonal channels are more likely to meet specific needs of organizational members

in overcoming risk and complexity associated with a change. When high risk or complexity

are not major factors, mediated channels are more effective in providing general

information.

4. Most mediated communications (e.g. reports, newspapers, videos, posters, chief executive

officer’s CEO presentations, closed-circuit TV shows) are centered on the CEO’s message,

which can be counterproductive. Research suggests that employees change only if they

receive rationales for change from their immediate supervisor rather than others further up

the food chain of the organization.

04 Handout 1 *Property of STI

Page 2 of 5

SH1720

In understanding organizations and the patterns of communication within them, one (1) for the

critical concepts is directionality.

Vertical communication refers to sending and receiving messages between the levels of a

hierarchy, whether downward or upward.

Horizontal communication refers to sending and receiving messages between individuals at the

same level a hierarchy.

Methods of Community Action Implementation

1. Finding Partners, Finding Focus

It is important to understand the relationship between the partners and the substantive focus.

The partners decide the focus and the substantive focus decides the partners. That

interrelationship is the guiding principle in assembling an effective partnership.

For Example:

The leaders of two (2) youth-serving organizations with their new partners may decide their

community needs a comprehensive youth development agenda. Once the partners make that

their focus, other partners need to be included to work on that task; and some of the original

partners may choose to not move forward. In other words, the focus needs to fit the interests

and resources of each of the partners, otherwise, a partner will not see a reason to stay at the

table.

2. Getting the Partnership Started

Some conveners start a community partnership by reaching out to people they already know.

Others want to reach out to everyone, making sure they do not exclude anyone. Resist both

natural courses of action and start with some analysis that creates a correlation between the

potential partners and the potential focus. To start, a small group of leaders can systematically

discuss a series of questions that help navigate one of the first tensions of a partnership — how

to be inclusive on the one hand, and how to keep the partnership to a manageable size on the

other.

3. Getting the Partnership Ready for the Action

There are many conceptual frameworks for developing a plan. Most partners have gone

through an exercise such as developing a vision and an action plan or walking through the steps

of building a mission, goals, and objectives. Most partnerships start a community assessment

process that allows them to tackle a basic question. To make progress in their area of focus,

does the community need more of the same (e.g., more services, more playgrounds, more social

workers) or does the community need to rethink how it approaches the challenge? In most

cases, the answer is both. That latter challenge—rethinking the approach—is where the

partnership must engage in hard work—tackling difficult issues ranging from turf and ego to

power and oppression.

Community Profiling

Partnerships develop different strategies based on the opportunities and needs in their

community. The types of services partnerships may offer are the following:

• Coordinate services and strengthen communication between agencies and clients.

• Provide technical assistance and training to increase the skills and/or knowledge of

personnel and build capacity within the field.

04 Handout 1 *Property of STI

Page 3 of 5

SH1720

• Organize resource development and sharing through coordination of purchasing

programs or by creating joint grant proposals.

• Organize community residents to be stronger advocates and take more responsibility

for their community.

• Conduct research projects to assess the needs of the community and help identify gaps

in service.

• Promote service needs and advocate for changes through legislative and other policy

avenues.

• Educate the community on the issue by promoting events, establishing a speakers’

bureau and/or publishing a community newsletter.

4. Action

This is an exciting step for the group. It brings people together, increases people’s

ownership and motivation for the project, and can lead to new people wanting to be at the

table. Though there is much excitement, there are still issues to address during this time.

5. Assessing the Growing Community Action Plan and the Community Partnership

Building and maintaining effective community and partnerships requires dedicated time

and ongoing attention to the collaborative process.

The use of the assessment, such as checklists or survey form that will help you understand

the community and the local groups where it may need attention. Assessing the community

before and after the action helps the local government monitor the community and its

developments.

Various Aspects of Group Process

When we speak of group aspects, we refer to group properties or regularities in the interaction

among the individuals, and in their activities over time. These properties of the group are essential

to uncover the dynamics of each member in pursuing his goals and aspirations.

Types of Group Involvement

1. Primary group – greater degree of personal involvement, informal. Example: friends,

family

2. Secondary group – formal and lesser degree of personal involvement. Example: Club or

Sorority

3. Exclusive group – membership limited to certain class of individuals.

4. Inclusive group – greater interaction with the context of equalization in society.

5. “In” group or “We” group – strong feeling of loyalty, sympathy, and devotion.

6. “Our” group or “They” group – more detached and less cohesive.

A group refers to two (2) or more persons engaged in any kind of relationship. When two (2)

members disagree with a third (triad), the group is called a coalition. Group membership is affected

by the following:

1. Satisfaction (reward)

2. Problem (cost), which serve to interfere or inhibit performance of action

3. Influence upon others (social pressure)

4. Each member influencing others (reciprocal or mutual control)

5. Cohesiveness – forces acting on the group member to remain in the group (commitment)

6. Compatibility – ability of the people to develop harmonious relationships with one another

04 Handout 1 *Property of STI

Page 4 of 5

SH1720

7. Norms – adherence to uniform patterns of behaviour of the group

8. Morale – optimistic feelings and confidence in the group with respect to problems or tasks

9. Social climate – emotional atmosphere of the group, which may be characterized by warm

or cold acceptance, hostilities, being detached or relaxed

10. Reference group – any group that has a normative effect on behaviour or standard of the

group.

Purpose of Group Formation

1. Accidental or Voluntary

The accidental formation is beyond control not at all deliberated.

The voluntary formation is the result of mutual attraction or goals.

2. Task-oriented or Social Function

Task-oriented – formed to accomplish a job

Social function – developed to enhance human interaction or improve the interpersonal

relationship.

Factors Affecting Group Activity

It is important to remember that the group members are made, not born to see their own efforts in

relation to those of the group. To make the kind of contribution that makes group activity more

effective, it will depend on several factors: size of the group and physical condition, absence or

presence of stress or anxiety, kind of leadership, goals and objectives, roles and needs, and

assessment and evaluation.

1. Size of the Group – The size of the group should not be small or too big. The ideal number

of participants is 12 to 20 members. Bigger groupings can cause people to withdraw.

2. Threat Reduction and Degree of Intimacy – Removal of the element of uncertainty or

surprises. It is important that people feel accepted and are comfortable. It is vital that people

should know one another, e.g. by having name tags or allowing social interactions. A brief

introduction of oneself or relating some funny incident about oneself will promote

familiarity. There must be a climate of mutual trust.

3. Distributive Leadership with Focus of Control on Group Activity – The absence of stress

and tension will develop trust and confidence to the accepted leader who will work for the

welfare of the group.

4. Goal Formation – Must share purposes and aspiration

5. Flexibility – Adaptable to the need of the group.

6. Consensus and Degree of Solidarity – Discussion and deliberation of issues, where

everyone is given a chance to express his views and be gratified for giving a solution to the

problem.

7. Process Awareness and Continue Evaluation – There must be an increasing sensitivity to

the roles and needs of different members. Close follow-up and honest evaluation of activity

must be made.

References:

Arcinas, M. (2016). Discipline and ideas in applied social sciences. Quezon, City. Phoenix Publishing

House, Inc.

Institute for Educational Leadership. (n.d.). Building effective community partnerships. Washington, DC.:

Author

Tria, G. & Jao, L. (1999). Introductory course in group dynamics. Rex Book Store. Manila, Philippines.

04 Handout 1 *Property of STI

Page 5 of 5

You might also like

- Introduction To CommunicationDocument38 pagesIntroduction To Communicationricha singhNo ratings yet

- W14 - Worksheet 1 (GEC 106)Document3 pagesW14 - Worksheet 1 (GEC 106)obrie diazNo ratings yet

- Unit 1 - Communicate in A Business Environment NVQDocument9 pagesUnit 1 - Communicate in A Business Environment NVQSadiq Ebrahim DawoodNo ratings yet

- Assessment 2 Lesson PlanDocument15 pagesAssessment 2 Lesson Planapi-403689756No ratings yet

- Dia SsssssDocument11 pagesDia SsssssJahna ManinangNo ratings yet

- Communication Concept by MeDocument14 pagesCommunication Concept by MeGaurav SinghNo ratings yet

- Importance: The Significance of CommunicationDocument4 pagesImportance: The Significance of Communicationmisael gizacheNo ratings yet

- Bj0050 SLM Unit 02Document16 pagesBj0050 SLM Unit 02shalakagadgilNo ratings yet

- Communication Nature, Functions and ScopeDocument25 pagesCommunication Nature, Functions and ScopebasuNo ratings yet

- Business Communication Module (Repaired)Document117 pagesBusiness Communication Module (Repaired)tagay mengeshaNo ratings yet

- BTTM 304Document264 pagesBTTM 304akfanNo ratings yet

- Assignment of Effective CommunicationDocument4 pagesAssignment of Effective CommunicationMd. Rashed Mahbub Sumon100% (4)

- Business Communication in An MNC in BD, UnileverDocument20 pagesBusiness Communication in An MNC in BD, UnileverAbdullah Al Mahmud33% (3)

- Business Com. Chapter 4Document43 pagesBusiness Com. Chapter 4Seida AliNo ratings yet

- Communication ChannelsDocument11 pagesCommunication ChannelsSheila692008No ratings yet

- Intro To BCDocument11 pagesIntro To BCpushpender gargNo ratings yet

- Managerial Communications: 4 Year Business AdministrationDocument15 pagesManagerial Communications: 4 Year Business Administrationاحمد صلاحNo ratings yet

- CommunicationDocument27 pagesCommunicationNisha MalhotraNo ratings yet

- Assignment On Business CommunictionDocument2 pagesAssignment On Business CommunictionBro AdhikariNo ratings yet

- Assignment On Business CommunictionDocument2 pagesAssignment On Business CommunictionBro AdhikariNo ratings yet

- Planning Organizing Staffing Directing Controlling: Oral CommunicationDocument9 pagesPlanning Organizing Staffing Directing Controlling: Oral CommunicationmitsriveraNo ratings yet

- All UnitsDocument104 pagesAll UnitsKarthick RajaNo ratings yet

- Chapter II - Administrative and Business CommunicationDocument13 pagesChapter II - Administrative and Business CommunicationYIBELTAL ANELEYNo ratings yet

- Assignment - Introduction To Business CommunicationDocument13 pagesAssignment - Introduction To Business CommunicationRafaNo ratings yet

- Block 4 MCO 1 Unit 4Document17 pagesBlock 4 MCO 1 Unit 4Tushar SharmaNo ratings yet

- Module 1 WORD1Document10 pagesModule 1 WORD1Kristine GonzagaNo ratings yet

- The Tips College of Commerce: Q.1 Define Communication? Also Explain Its Importance?Document48 pagesThe Tips College of Commerce: Q.1 Define Communication? Also Explain Its Importance?Muhammad AkramNo ratings yet

- Business Cummunication Security MGNTDocument50 pagesBusiness Cummunication Security MGNTJonathan SmokoNo ratings yet

- BC PowerPoint PresentationDocument164 pagesBC PowerPoint PresentationMelkamu TuchamoNo ratings yet

- Communication in OrganizationDocument11 pagesCommunication in OrganizationAsim IkramNo ratings yet

- The Discipline of CommunicationDocument42 pagesThe Discipline of CommunicationNadia Caoile IgnacioNo ratings yet

- BC Unit-1Document20 pagesBC Unit-1AbinashNo ratings yet

- Business Communication - Unit 1 & 2Document93 pagesBusiness Communication - Unit 1 & 2VedikaNo ratings yet

- Principles of Management Unit 5Document31 pagesPrinciples of Management Unit 5ajarmohamed2003No ratings yet

- Unit 1 Communication in The Work PlaceDocument27 pagesUnit 1 Communication in The Work PlaceParthiban PartNo ratings yet

- Industrial Management NotesDocument66 pagesIndustrial Management NotesLearnmore MakwangudzeNo ratings yet

- Nature and Process of CommunicationDocument27 pagesNature and Process of CommunicationBiyas DattaNo ratings yet

- CH 1Document5 pagesCH 1rozina seidNo ratings yet

- Communication Strategies: Description Required Activity Making It WorkDocument7 pagesCommunication Strategies: Description Required Activity Making It WorkEvan CaldwellNo ratings yet

- 03 Chapter 3 - Communications, Pp. 39-48Document10 pages03 Chapter 3 - Communications, Pp. 39-48nforce1No ratings yet

- Bcps Notes 16-17 (II Sem)Document48 pagesBcps Notes 16-17 (II Sem)karamthota bhaskar naikNo ratings yet

- Fed413 - Communications in Educational OrganisationsDocument4 pagesFed413 - Communications in Educational OrganisationsIbrahm ShosanyaNo ratings yet

- Commonly". Therefore, The Word Communication Means Sharing of Ideas, Messages and WordsDocument50 pagesCommonly". Therefore, The Word Communication Means Sharing of Ideas, Messages and WordsMohammed Demssie MohammedNo ratings yet

- Unit 4 PPBMDocument8 pagesUnit 4 PPBMkumaryadavv866No ratings yet

- Factors Influencing Communication in Organizations Research PaperDocument18 pagesFactors Influencing Communication in Organizations Research PaperGUDINA MENGESHA MEGNAKANo ratings yet

- Importance of CommunicationDocument4 pagesImportance of CommunicationTramserNo ratings yet

- 2-Communication - What Is A Communication BreakdownDocument8 pages2-Communication - What Is A Communication BreakdownS.m. ChandrashekarNo ratings yet

- 3 Chapter V-CONCEPT-ON-ORGANIZATIONAL-MANAGEMENT-finalDocument20 pages3 Chapter V-CONCEPT-ON-ORGANIZATIONAL-MANAGEMENT-finalMariane DacalanNo ratings yet

- BC NotesDocument11 pagesBC NotesMeenakshi RajakumarNo ratings yet

- INTERPERSONAL AND ORGANIZATIONAL CommDocument14 pagesINTERPERSONAL AND ORGANIZATIONAL CommGeejay alemanNo ratings yet

- Communication 1st Unit - CompleteDocument17 pagesCommunication 1st Unit - CompleteAnuj SaxenaNo ratings yet

- Employability Final NotesDocument11 pagesEmployability Final NotesAurelia NkongeNo ratings yet

- Communication Skills For Business Task 1Document14 pagesCommunication Skills For Business Task 1maadjei059No ratings yet

- Bhmaecc IIDocument171 pagesBhmaecc IIAnkit Kumar JainNo ratings yet

- PR NotesDocument12 pagesPR NotesMarija DambrauskaitėNo ratings yet

- BCSS Material FinalDocument123 pagesBCSS Material FinalMurthyNo ratings yet

- Communications in OrganisationsDocument11 pagesCommunications in Organisationsdaniel plescaNo ratings yet

- COMMUNICATON-Abebe Yirdaw 2007Document13 pagesCOMMUNICATON-Abebe Yirdaw 2007yirgalemle ayeNo ratings yet

- MTP Supplemental Notes 3Document5 pagesMTP Supplemental Notes 3Kashae JohnsonNo ratings yet

- Communication NotesDocument12 pagesCommunication Notesaniketavaidya66No ratings yet

- Effective Teamwork - Embracing Differences, Optimizing Meetings, And Achieving Team Success: An Introductory Detailed GuideFrom EverandEffective Teamwork - Embracing Differences, Optimizing Meetings, And Achieving Team Success: An Introductory Detailed GuideNo ratings yet

- Community Health Nursing ProcessDocument54 pagesCommunity Health Nursing ProcessAndrea Monique GalasinaoNo ratings yet

- Grade 1 Social Studies Curriculum PDFDocument6 pagesGrade 1 Social Studies Curriculum PDFhlariveeNo ratings yet

- Waseem Akhtar: Personal InformationDocument5 pagesWaseem Akhtar: Personal InformationWaseem Akhtar GhouriNo ratings yet

- Chapter 9-10 PDFDocument22 pagesChapter 9-10 PDFjey jeyd88% (8)

- Assessment of Community Support For PublDocument136 pagesAssessment of Community Support For Publjomex tundexNo ratings yet

- City Builder (11-19-2020)Document245 pagesCity Builder (11-19-2020)vaneb28540150% (2)

- RQM Assignment 3Document6 pagesRQM Assignment 3nicolekhella1No ratings yet

- 2015 Annual ReportDocument36 pages2015 Annual ReportJohn Humphrey Centre for Peace and Human RightsNo ratings yet

- Community Engagement Officer Cover LetterDocument6 pagesCommunity Engagement Officer Cover Lettereljaswrmd100% (1)

- 10 Jurnal LuarDocument16 pages10 Jurnal LuarAji PangestuNo ratings yet

- Nogor-Haat Reimagining An Urban Marketplace As The Neighborhood SquareDocument88 pagesNogor-Haat Reimagining An Urban Marketplace As The Neighborhood SquareSahar ZehraNo ratings yet

- Public Relation EnglishDocument67 pagesPublic Relation EnglishGargiRanaNo ratings yet

- Community Needs Assessment Survey GuideDocument19 pagesCommunity Needs Assessment Survey GuideshkadryNo ratings yet

- EDUC 101 Syllabus EDE A BDocument13 pagesEDUC 101 Syllabus EDE A BJoseph Gabriel EstrellaNo ratings yet

- Kaiserain G. Arante Humss #CoopfamDocument32 pagesKaiserain G. Arante Humss #Coopfamren renteNo ratings yet

- Antonio, Jaymark C.: College of Teacher Education and Human SciencesDocument2 pagesAntonio, Jaymark C.: College of Teacher Education and Human SciencesMark Anthony AntonioNo ratings yet

- Singapore - Housing Practise SeriesDocument90 pagesSingapore - Housing Practise SeriesMinhHyNo ratings yet

- Pisan CommunityDocument1 pagePisan CommunityEmilie Caja100% (1)

- FINAL Health Education SettingsDocument18 pagesFINAL Health Education SettingsClarisse Santiago100% (1)

- Technology, Pedagogy and Education Reflections On The Accomplishment of What Teachers Know, Do and Believe in A Digital Age LovelessDocument17 pagesTechnology, Pedagogy and Education Reflections On The Accomplishment of What Teachers Know, Do and Believe in A Digital Age LovelessTom Waspe Teach100% (1)

- National Highway, San Pedro, Laguna: San Francisco de Sales SchoolDocument4 pagesNational Highway, San Pedro, Laguna: San Francisco de Sales SchoolRaiza CabreraNo ratings yet

- The Social and Economic Value of Adult Grassroots Football in EnglandDocument131 pagesThe Social and Economic Value of Adult Grassroots Football in EnglandAwseome Vaibhav SahrawatNo ratings yet

- 2 Smith Studies in Social Justice Human Rights CitiesDocument22 pages2 Smith Studies in Social Justice Human Rights CitiesmkrNo ratings yet

- Revised Hematology Course Syllabus Aug 2, 2020Document11 pagesRevised Hematology Course Syllabus Aug 2, 2020Edna Uneta Robles100% (1)

- Competency Framework For TeachersDocument48 pagesCompetency Framework For TeachersMimi AringoNo ratings yet

- Zoom Ice Breaking Idea ViDocument5 pagesZoom Ice Breaking Idea ViWIBER ChapterLampungNo ratings yet

- New Defence PolicyDocument40 pagesNew Defence PolicyStuff NewsroomNo ratings yet

- 12community Outreach Program Understanding The Concepts and Principles of Community ImmersionDocument14 pages12community Outreach Program Understanding The Concepts and Principles of Community ImmersionKayla ParanNo ratings yet