Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Clinical Scales For Assessment of Dehydration in Children With Diarrhea

Clinical Scales For Assessment of Dehydration in Children With Diarrhea

Uploaded by

Muhammad FathurrahmanCopyright:

Available Formats

You might also like

- Treatment Guidelines (Nigeria)Document116 pagesTreatment Guidelines (Nigeria)Laarny De Jesus Garcia - Ame100% (1)

- Keith Edwards Score For Diagnosis of Tuberculosis. IJP.03Document3 pagesKeith Edwards Score For Diagnosis of Tuberculosis. IJP.03Diego Bedon AscurraNo ratings yet

- 07-Acute Diarrheal Diseases (Ward Lectures)Document33 pages07-Acute Diarrheal Diseases (Ward Lectures)Zaryab Umar100% (1)

- Irene EvnDocument4 pagesIrene EvnashniemagdaliNo ratings yet

- The Value of Body Weight MeasuDocument7 pagesThe Value of Body Weight MeasuDina AryaniNo ratings yet

- Summ 1619Document8 pagesSumm 1619novialbarNo ratings yet

- Nested Case Control StudyDocument16 pagesNested Case Control Studyqtftwkwlf100% (1)

- The Value of Body Weight MeasuDocument12 pagesThe Value of Body Weight MeasuDina AryaniNo ratings yet

- Motivations For Weight Loss in Adolescents With Overweight and Obesity A Systematic ReviewDocument8 pagesMotivations For Weight Loss in Adolescents With Overweight and Obesity A Systematic ReviewBruno SilvaNo ratings yet

- BackgroundDocument16 pagesBackgroundLegionella ComanderNo ratings yet

- Zhang 2020Document14 pagesZhang 2020Belen GaleraNo ratings yet

- Cochrane BVS: Oral Zinc For Treating Diarrhoea in ChildrenDocument25 pagesCochrane BVS: Oral Zinc For Treating Diarrhoea in ChildrenLaura AnguloNo ratings yet

- Endoscopic Sleeve Gastroplasty As An Early Tool Against Obesity: A Multicenter International Study On An Overweight PopulationDocument6 pagesEndoscopic Sleeve Gastroplasty As An Early Tool Against Obesity: A Multicenter International Study On An Overweight PopulationduranaxelNo ratings yet

- GROUP 4 EBP On Renal NursingDocument7 pagesGROUP 4 EBP On Renal Nursingczeremar chanNo ratings yet

- Assessment of Self Management in Patients With DiaDocument9 pagesAssessment of Self Management in Patients With DiaPaula Francisca Moraga HidalgoNo ratings yet

- Classification of Feeding and Eating DisordersDocument13 pagesClassification of Feeding and Eating DisordersMagito JayaNo ratings yet

- Evidence Analysis Library Review of Best Practices For Performing Indirect Calorimetry in Healthy and NoneCritically Ill IndividualsDocument32 pagesEvidence Analysis Library Review of Best Practices For Performing Indirect Calorimetry in Healthy and NoneCritically Ill IndividualsNutricion Deportiva NutrainerNo ratings yet

- Saccharomyces Boulardii: Meta-Analysis: For Treating Acute Diarrhoea in ChildrenDocument8 pagesSaccharomyces Boulardii: Meta-Analysis: For Treating Acute Diarrhoea in ChildrenJOSE LUIS PENAGOSNo ratings yet

- Lo Per Amide Therapy For Acute Diarrhea in Children Systematic Review and Meta-AnalysisDocument11 pagesLo Per Amide Therapy For Acute Diarrhea in Children Systematic Review and Meta-AnalysisAprilia R. PermatasariNo ratings yet

- Characteristics of Pediatric Patients With Diarrhea in Indonesia: A Laboratory-Based ReportDocument8 pagesCharacteristics of Pediatric Patients With Diarrhea in Indonesia: A Laboratory-Based ReportDrnNo ratings yet

- Running Head: Cardiovascular Disease Prevention 1Document8 pagesRunning Head: Cardiovascular Disease Prevention 1Sammy GitauNo ratings yet

- Original Article: Saudi Journal of Kidney Diseases and TransplantationDocument7 pagesOriginal Article: Saudi Journal of Kidney Diseases and TransplantationRontiNo ratings yet

- Childhood Obesity Is Associated With A High DegreeDocument14 pagesChildhood Obesity Is Associated With A High DegreeMahd oNo ratings yet

- 2014 Immediate Fluid Management of Children With Severe Febrile Illness and Signs of Impaired Circulation in Low-Income SettingsDocument8 pages2014 Immediate Fluid Management of Children With Severe Febrile Illness and Signs of Impaired Circulation in Low-Income SettingsVladimir BasurtoNo ratings yet

- Complete Summary: Guideline TitleDocument27 pagesComplete Summary: Guideline TitleRudi ArdiyantoNo ratings yet

- Metanalisis 2015Document15 pagesMetanalisis 2015Pitu MinvielleNo ratings yet

- Steroids For Airway EdemaDocument7 pagesSteroids For Airway EdemaDamal An NasherNo ratings yet

- EDA. Pediatrics 2010Document12 pagesEDA. Pediatrics 2010Carkos MorenoNo ratings yet

- 2018 Article 1006Document9 pages2018 Article 1006Daniel PuertasNo ratings yet

- Obesity Reviews - 2023 - Blaxall - Obesity Intervention Evidence Synthesis Where Are The Gaps and Which Should We AddressDocument18 pagesObesity Reviews - 2023 - Blaxall - Obesity Intervention Evidence Synthesis Where Are The Gaps and Which Should We AddressPatyNo ratings yet

- NST Supported by Original Data (Age)Document18 pagesNST Supported by Original Data (Age)Rika LedyNo ratings yet

- Diagnostic Approach in Children With Short Stature PDFDocument12 pagesDiagnostic Approach in Children With Short Stature PDFHandre PutraNo ratings yet

- Nutrients 13 03640 v2Document20 pagesNutrients 13 03640 v2Sophia van de MeerakkerNo ratings yet

- Head Et Al-2018-Cochrane Database of Systematic ReviewsDocument4 pagesHead Et Al-2018-Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviewsasujan58pNo ratings yet

- WNL 2022 201574Document10 pagesWNL 2022 201574triska antonyNo ratings yet

- Taylor Et Al-2006-Australian and New Zealand Journal of Public HealthDocument9 pagesTaylor Et Al-2006-Australian and New Zealand Journal of Public HealthRahmat ullahNo ratings yet

- Nutritional Assessment of Children With CHD CompareDocument9 pagesNutritional Assessment of Children With CHD CompareIntan Robi'ahNo ratings yet

- Short Report: Education and Psychological Aspects Modification and Validation of The Revised Diabetes Knowledge ScaleDocument5 pagesShort Report: Education and Psychological Aspects Modification and Validation of The Revised Diabetes Knowledge ScaleadninaninNo ratings yet

- Jurnal Cbe 1Document21 pagesJurnal Cbe 1Dewi SurayaNo ratings yet

- Influence of Nutritional Status On Clinical Outcomes in Critically Ill ChildrenDocument5 pagesInfluence of Nutritional Status On Clinical Outcomes in Critically Ill ChildrenAnonymous h0DxuJTNo ratings yet

- Influence of Nutritional Status On Clinical Outcomes in Critically Ill ChildrenDocument5 pagesInfluence of Nutritional Status On Clinical Outcomes in Critically Ill ChildrenIvana YunitaNo ratings yet

- Lins 2016Document8 pagesLins 2016David AzevedoNo ratings yet

- 1625-Article Text-4407-1-10-20230707Document14 pages1625-Article Text-4407-1-10-20230707dewa putra yasaNo ratings yet

- Pedroso Et Al. 2021Document12 pagesPedroso Et Al. 2021seriesediversosNo ratings yet

- Literature Review of Gestational DiabetesDocument10 pagesLiterature Review of Gestational Diabetesc5pnw26s100% (1)

- File 2Document18 pagesFile 2Ikke PrihatantiNo ratings yet

- Severity Scoring Systems: Are They Internally Valid, Reliable and Predictive of Oxygen Use in Children With Acute Bronchiolitis?Document7 pagesSeverity Scoring Systems: Are They Internally Valid, Reliable and Predictive of Oxygen Use in Children With Acute Bronchiolitis?Ivan VeriswanNo ratings yet

- CAGE Questionnaire For Alcohol MisuseDocument10 pagesCAGE Questionnaire For Alcohol MisuseJeremy BergerNo ratings yet

- Current Databases On Biological Variation: Pros, Cons and ProgressDocument10 pagesCurrent Databases On Biological Variation: Pros, Cons and ProgressCarlos PardoNo ratings yet

- Inter-Rater Reliability of The Subjective Global Assessment A Systematic Literature ReviewDocument4 pagesInter-Rater Reliability of The Subjective Global Assessment A Systematic Literature ReviewzxnrvkrifNo ratings yet

- Guidelines For Managing Acute Gastroenteritis Based On A Systematic Review of Published ResearchDocument7 pagesGuidelines For Managing Acute Gastroenteritis Based On A Systematic Review of Published ResearchnikopkunairNo ratings yet

- Treatment of Pediatric ObesityDocument6 pagesTreatment of Pediatric Obesitymaxime wotolNo ratings yet

- Nutrition Screening AssesmentDocument11 pagesNutrition Screening AssesmentIrving EuanNo ratings yet

- Subjective Global Assessment in Chronic Kidney Disease - A ReviewDocument10 pagesSubjective Global Assessment in Chronic Kidney Disease - A ReviewDiana Laura MtzNo ratings yet

- BVS Odontologia: Informação e Conhecimento para A SaúdeDocument3 pagesBVS Odontologia: Informação e Conhecimento para A SaúdeGabriel SilvaNo ratings yet

- HBMOSDocument11 pagesHBMOSekaNo ratings yet

- Evaluation of Nutrition Status Using The Subjective Global Assessment: Malnutrition, Cachexia, and SarcopeniaDocument15 pagesEvaluation of Nutrition Status Using The Subjective Global Assessment: Malnutrition, Cachexia, and SarcopeniaLia. OktarinaNo ratings yet

- The Endocrine Society Clinical Practice Guidelines: A Self-AssessmentDocument4 pagesThe Endocrine Society Clinical Practice Guidelines: A Self-AssessmentRiskha Febriani HapsariNo ratings yet

- Bookshelf NBK315902Document18 pagesBookshelf NBK315902Lucas WillianNo ratings yet

- M CAD Ermatol PrilDocument1 pageM CAD Ermatol PrilValentina AdindaNo ratings yet

- NCP 10589Document8 pagesNCP 10589Mita AriniNo ratings yet

- Complementary and Alternative Medical Lab Testing Part 5: GastrointestinalFrom EverandComplementary and Alternative Medical Lab Testing Part 5: GastrointestinalNo ratings yet

- Gastroenteritis in Children Part II. Prevention and Management 2012Document5 pagesGastroenteritis in Children Part II. Prevention and Management 2012Douglas UmbriaNo ratings yet

- Acute Viral Gastroenteritis in Adults UpToDateDocument12 pagesAcute Viral Gastroenteritis in Adults UpToDateItzrael DíazNo ratings yet

- Management of Medical Complications in Severe Acute Malnutrition (SAM)Document4 pagesManagement of Medical Complications in Severe Acute Malnutrition (SAM)Archana SinghNo ratings yet

- Surprised Samples With Coaching Samples (1) 2Document55 pagesSurprised Samples With Coaching Samples (1) 2EmmanuellaNo ratings yet

- Doh 07Document37 pagesDoh 07Malack ChagwaNo ratings yet

- New Pediatric Guideline Hargeisa Group Hospital by DR NelsonDocument54 pagesNew Pediatric Guideline Hargeisa Group Hospital by DR NelsonKhadar mohamedNo ratings yet

- 10 Steps Wall ChartDocument2 pages10 Steps Wall ChartTommy CharwinNo ratings yet

- Chart Booklet 2013 Final July 2013Document46 pagesChart Booklet 2013 Final July 2013Alazar shenkoruNo ratings yet

- Acute Viral Gastroenteritis in AdultsDocument13 pagesAcute Viral Gastroenteritis in AdultsyessyNo ratings yet

- DGDFHDFDocument6 pagesDGDFHDFFaye IlaganNo ratings yet

- Nelson's MCQ'sDocument150 pagesNelson's MCQ'sDrSheika Bawazir93% (40)

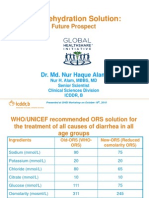

- Oral Rehydration Solution:: Future ProspectDocument48 pagesOral Rehydration Solution:: Future ProspectmustikaarumNo ratings yet

- Oralade Dog BrochureLQDocument4 pagesOralade Dog BrochureLQKatrina MarshallNo ratings yet

- CPG - Acute Infectious DiarrheaDocument52 pagesCPG - Acute Infectious DiarrheaJim Christian EllaserNo ratings yet

- Kwashior and MarasmusDocument17 pagesKwashior and Marasmuszuby_0302No ratings yet

- Approach To The Child With Acute Diarrhea in Resource-Limited Countries - UpToDateDocument17 pagesApproach To The Child With Acute Diarrhea in Resource-Limited Countries - UpToDateNedelcu MirunaNo ratings yet

- PharmCal Lab Finals (H2O2, Alum, Aluminum Magnesium Hydoxide Gel, ORS, Cupric Sulfate)Document10 pagesPharmCal Lab Finals (H2O2, Alum, Aluminum Magnesium Hydoxide Gel, ORS, Cupric Sulfate)a yellow flowerNo ratings yet

- Maintaining Fluid & Electrolyte Balance in The BodyDocument124 pagesMaintaining Fluid & Electrolyte Balance in The BodyKingJayson Pacman06100% (1)

- Child Bronchiolitis 1Document2 pagesChild Bronchiolitis 1sarooah1994100% (2)

- Who Dehidrasi PG 17 PDFDocument52 pagesWho Dehidrasi PG 17 PDFSasha ManoNo ratings yet

- Hidrasec Adults 9-11-07Document81 pagesHidrasec Adults 9-11-07Christian Gallardo, MD100% (1)

- Cisplatin Monograph 1jul2016Document11 pagesCisplatin Monograph 1jul2016Kurnia AnharNo ratings yet

- Food and Personal Hygiene Perceptions and PracticesDocument8 pagesFood and Personal Hygiene Perceptions and PracticesFa MoNo ratings yet

- Diarrhea GuidelineDocument29 pagesDiarrhea GuidelineMonica GabrielNo ratings yet

- Safe Water School: Training ManualDocument120 pagesSafe Water School: Training Manuallisa.piccininNo ratings yet

- Diarrhoea +/ Vomiting: Nurse Practitioner Clinical Protocol Emergency DepartmentDocument10 pagesDiarrhoea +/ Vomiting: Nurse Practitioner Clinical Protocol Emergency DepartmentLalaine RomeroNo ratings yet

- Pedia Exam QuestionsDocument6 pagesPedia Exam QuestionsbNo ratings yet

- Acute Gastroenteritis in Children: Prepared By: Prof. Elizabeth D. Cruz RN, ManDocument12 pagesAcute Gastroenteritis in Children: Prepared By: Prof. Elizabeth D. Cruz RN, ManChaii De GuzmanNo ratings yet

Clinical Scales For Assessment of Dehydration in Children With Diarrhea

Clinical Scales For Assessment of Dehydration in Children With Diarrhea

Uploaded by

Muhammad FathurrahmanOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Clinical Scales For Assessment of Dehydration in Children With Diarrhea

Clinical Scales For Assessment of Dehydration in Children With Diarrhea

Uploaded by

Muhammad FathurrahmanCopyright:

Available Formats

JOURNAL CLUB

Clinical Scales for Assessment of Dehydration in Children with Diarrhea

Source Citation: Falszewska A, Szajewska H, Dziechciarz P. Diagnostic accuracy of three clinical dehydration scales:

a systematic review. Arch Dis Child. 2018;103:383-8.

Section Editor: ABHIJEET SAHA

SUMMARY used for rehydration. On the one hand, inaccurate

estimation of the degree of dehydration can lead to

This systematic review assessed the diagnostic accuracy

under-hydration and organ damage. On the other hand,

of the Clinical Dehydration Scale (CDS), the World

over-enthusiastic rehydration can also lead to another

Health Organization (WHO) Scale and the Gorelick

spectrum of clinical problems [6]. This systematic

Scale in identifying dehydration in children with acute

review [7] explored the diagnostic accuracy of three

gastroenteritis (AGE). Three databases, two registers of

commonly used tools to assess and quantify the degree of

clinical trials and the reference lists from identified

dehydration in children with acute diarrhea. These were:

articles were searched for diagnostic accuracy studies in

(i) Clinical Dehydration Scale (CDS), (ii) World Health

children with AGE. The index tests were the CDS, WHO

Organization (WHO) Scale, and (iii) Gorelick Scale.

Scale and Gorelick Scale, and reference standard was the

The authors concluded that none of the three scales could

percentage loss of body weight. In high-income

reliably predict the presence and degree of dehydration

countries, the CDS provided a moderate to large increase

in children with diarrhea compared to estimation of

in the post-test probability of predicting moderate to

weight loss. Similarly, the scales could not reliably rule

severe (≥6%) dehydration, but it was of limited value for

out dehydration either.

ruling it out. In low-income countries, the CDS showed

limited value both for ruling in and ruling out moderate- Critical appraisal: Table I summarizes critical appraisal

to-severe dehydration. In both settings, the CDS showed of the systematic review [7] using one of several tools

poor diagnostic accuracy for ruling in or out no designed for the purpose [8]. In general, the systematic

dehydration (<3%) or some dehydration (3%-6%). The review was conducted as per the expected standards for

WHO Scale showed no or limited value in assessing such reviews. The authors chose an appropriate

dehydration in children with diarrhea. With one participant age group, used appropriate inclusion and

exception, the included studies did not confirm the exclusion criteria for studies, selected appropriate

diagnostic accuracy of the Gorelick Scale. The authors interventions, and examined multiple sources for

concluded that limited evidence suggests that the CDS potential studies. They examined each included study for

can help in ruling in moderate-to-severe dehydration methodological biases.

(≥6%) in high-income settings only. The WHO and

Gorelick Scales are not helpful for assessing dehydration One of the major challenges in reviews on this

in children with AGE. subject is the choice of the reference (i.e., gold standard)

test. For practical reasons, the currently accepted gold

COMMENTARIES standard for assessing the degree of dehydration is the

Evidence-based Medicine Viewpoint percentage of body weight lost. This poses two separate

challenges.

Relevance: Acute watery diarrhea and associated

dehydration are significant clinical problems in children The biggest problem with using ‘body weight lost’ as

– both at the individual level as well as from the public the reference standard is that it is very difficult to

health perspective [1-3]. Prompt and efficient measure. Since the pre-dehydration weight of children is

rehydration therapy has been instrumental in saving the not usually known, ‘body weight lost by dehydration’ is

lives of thousands of children across the globe [4,5]. generally calculated from ‘body weight gained by

Careful clinical assessment of the dehydrated child is rehydration’. This apparent paradox raises two further

required to guide the quantity, route and type of fluid problems. First, the body weight gained depends on the

INDIAN PEDIATRICS 513 VOLUME 55__JUNE 15, 2018

JOURNAL CLUB

TABLE I CRITICAL APPRAISAL OF THE SYSTEMATIC REVIEW

Parameter Comments

Validity

1. Did the review address aclearly Yes. Although a research question was not explicitly stated, the following PICO question can be

focused question? framed: In children with dehydration associated with diarrhea, what is the diagnostic accuracy

(Outcome) of three designated clinical scales to assess the degree of dehydration (Intervention)

compared to measurement of weight loss (Comparator)? The review was restricted to only three

scales/scoring systems viz. Clinical Dehydration Scale (CDS), World Health Organization (WHO)

Scale, and Gorelick Scale.

2. Did the authors look for Yes. The authors planned to include all study designs that could address the PICO question framed

the right type of papers? above.

3. Were all the important, Yes. Three of the most important electronic databases were searched, besides bibliographic lists of

relevant studies included? the identified publications. The output of these searches was presented separately. In addition, two

important registers of clinical trials were also searched for ongoing and unpublished studies. The

review authors attempted to contact authors of the included studies to obtain raw data. There was no

language restriction. These approaches suggest a low probability of missing relevant publications.

However, the basis for choosing the three included scales was not specified. Further, the detailed

search strategy was not presented.

4. Did the review authors assess Yes. The authors used the QUADAS 2 instrument for assessment of methodological quality. Most

quality of the included studies? of the included studies appeared to have low risk of bias.

5. Is it reasonable to combine Although it is reasonable to combine data across studies, the authors did not do so. Instead they

the results from different studies? displayed the results of diagnostic accuracy of each study individually and provided a summary

estimate by presenting the range of individual study estimates, rather than a weighted summary

pooling the studies together. The authors attempted to stratify results by the setting where studies

were performed, using the country income status as a surrogate marker. However, variations between

studies were not explored in detail.

Results

1. What are the overall results? Clinical Dehydration Scale

• Dehydration <3%: 4 studies, 534 participants, Sensitivity ranging from 0.00 to 0.33, Specificity

ranging from 0.80 to 1.00, LR+ ranging from 1.64 to 2.20, LR- ranging from 0.79 to 0.84.

• Dehydration 3-6%: 4 studies, 534 participants, Sensitivity ranging from 0.62 to 0.75, Specificity

ranging from 0.30 to 0.67, LR+ ranging from 1.10 to 1.88, LR- ranging from 0.57 to 0.90.

• Dehydration >6%: 5 studies, 582 participants, Sensitivity ranging from 0.31 to 0.68, Specificity

ranging from 0.38 to 0.97, LR+ ranging from 1.08 to 11.79, LR- ranging from 0.60 to 0.87.

World Health Organization Scale

• Dehydration <5%: 2 studies, 222 participants, Sensitivity ranging from 0.03 to 0.55, Specificity

ranging from 0.73 to 0.94, LR+ ranging from 0.48 to 2.00, LR- ranging from 0.60 to 1.03.

• Dehydration 5-10%: 3 studies, 271 participants, Sensitivity 5 studies, 463 participants, Sensitivity

ranging from 0.36 to 0.86, Specificity ranging from 0.22 to 0.69, LR+ ranging from 1.09 to 1.28,

LR- ranging from 0.65 to 0.90

• Dehydration >10%: 5 studies, 463 participants, Sensitivity ranging from 0.00 to 0.79, Specificity

ranging from 0.43 to 0.84, LR+ ranging from 0.00 to 2.1, LR- ranging from 0.00 to 1.22

Gorelick abridged Scale

• Dehydration 5-10%: 4 studies, 457 participants, Sensitivity ranging from 0.10 to 0.79, Specificity

ranging from 0.69 to 0.87, LR+ ranging from 0.40 to 6.25, LR- ranging from 0.24 to 1.20.

• Dehydration >10%: 4 studies, 457 participants, Sensitivity ranging from 0.33 to 1.00, Specificity

ranging from 0.23 to 0.83, LR+ ranging from 0.43 to 4.85, LR- ranging from 0.00 to 2.88.

Gorelick scale

• Data from different studies could not be compared on account of differences in criteria used.

2. How precise are the results? The authors did not pool the data through formal meta-analysis, hence estimate of precision could not

be made. However, given that the individual studies had widely differing precision estimates, it is

likely that the overall results may not be very precise.

INDIAN PEDIATRICS 514 VOLUME 55__JUNE 15, 2018

JOURNAL CLUB

amount of fluid used for rehydration, which in turn Clinical Dehydration Scale, the studies listed in the

depends upon the clinical estimation of dehydration Table are different from those included in the Figure.

severity (which is based on the very signs being Further, one of the studies in the figure shows 99

investigated by the included studies). Further, the timing participants; although, only 98 were included.

of the measurement of post-rehydration weight is not One important issue that the authors did not consider

standardized. In this systematic review [7], three of the is that their results and conclusions pertain only to

included studies used the discharge weight as the diagnosing the degree of dehydration in a dichotomous

surrogate for pre-dehydration weight, and three studies fashion (i.e., present or absent). They did not consider

calculated this on the basis of consecutive measurements whether the scales could be useful in quantifying the

showing nil or minimal variation, two studies did not exact amount of dehydration. Further, despite being an

specify how and when the final weight was measured, apparently continuous variable, percentage weight loss

and one study stated ‘rehydration weight’ but did not beyond the outer limit of each scale was not quantified.

clearly define this. In short, the reference standards in the Thus (for example) 11% body weight loss was

various included studies were neither uniform nor even considered the same as 16% loss. In such a setting, the

independent of the index test in some studies. value of these scales (if any) in quantifying dehydration

The second challenge with calculating percentage models was not explored through logistic regression.

body weight lost is that although the measure is a Extendibility: None of the included studies was

continuous variable and intuitively appealing, in reality conducted in India; although, some were conducted in

its interpretation can be difficult. For example, a child other developing countries. The authors also tried to

with 2% body weight loss is twice as dehydrated as a stratify the data from individual studies by the income

child with 1% body weight loss, but is not necessarily level of the country where it was performed. However,

twice as sick, or having twice the risk of complications. the major problem with interpretation of the data is the

Further, changes in the absolute percentage points can total lack of consideration to pre-existing or underlying

mean different things depending on the baseline status. malnutrition. In India, a significant proportion of

For example, alteration in body weight lost from 2% to children less than five years suffers from malnutrition

3% (i.e., 1% decline) does not have the same [9]. In most such settings, malnutrition is an independent

implications as change in body weight lost from 7% to driver of mortality in children with diarrhea and

8% (also a 1% decline). Of course, the practical dehydration [10]. Further, many of the clinical signs of

problems associated with weighing sick children dehydration are confounded by similarity with signs

multiple times during and after rehydration (even in representing severe malnutrition. In addition, in settings

hospital settings) also needs consideration. where nutritional supplementation is provided along

with rehydration, the final or discharge body weight may

Further the clinical scales are based on subjective

not accurately reflect the degree of dehydration.

observations by personnel with varying levels of training

and/or experience. Some of the criteria may be difficult Further, even though the systematic review did not

to distinguish across levels of dehydration severity. For find any of the clinical scales to have sufficient

example, application of the terms ‘sunken’ and ‘very diagnostic accuracy for use in clinical practice, it should

sunken’ (for eyeballs) may be highly subjective. It is also be emphasized that treatment decisions based on these

important to recognize that many of the signs included in very clinical observations have resulted in saving

the clinical scales actually represent hypovolemic shock millions of lives. This apparent paradox highlights the

(which is an adverse outcome or complication of gap between evidence of efficacy (from research studies)

dehydration), rather than dehydration alone. and evidence of effectiveness (from real-world

experience); although, in this situation the latter seems

To be fair, many of the challenges highlighted above superior to the former (unlike most situations).

are inherent to the scales themselves and hence beyond

the scope of the systematic review [7]. However, some Conclusion: This systematic review suggested that none

issues pertaining to the review itself need to be of the three clinical dehydration scales can be considered

addressed. For example, the authors constructed plots of accurate for the purpose of determining the degree of

the results of individual studies evaluating Clinical dehydration in children with diarrhea. This is in contrast

Dehydration Scale, but did not pool the results through to real-world experience wherein treatment decisions

meta-analysis. Instead only ranges of each outcome based on these scales (or components thereof) are

measure (sensitivity, specificity etc.) were presented. believed to be highly effective.

The reasons for this are unclear. Similarly, for the Funding: None; Competing interests: None stated.

INDIAN PEDIATRICS 515 VOLUME 55__JUNE 15, 2018

JOURNAL CLUB

JOSEPH L MATHEW combination of signs have better predictability.

Department of Pediatrics,

PGIMER, Chandigarh, India. The systematic review suffers from an important

dr.joseph.l.mathew@gmail.com lacuna, as it could not find adequate studies from

REFERENCES developing countries, particularly those assessing the

adequacy of scales in children with mild to moderate

1. World Health Organization. Diarrhoeal Disease. Available dehydration. It is important, as applicability of these

from: http://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/ scales of dehydration has never been validated in

diarrhoeal-disease. Accessed May 12, 2018.

malnourished children who form a significant proportion

2. UNICEF. Diarrhoeal Disease. Available from: https://

data.unicef.org/topic/child-health/diarrhoeal-disease/. of diarrheal children in the developing countries.

Accessed May 12, 2018. WHO system of dehydration assessment was

3. Lakshminarayanan S, Jayalakshmy R. Diarrheal diseases introduced not as a scientific scale (it does not have

among children in India: Current scenario and future

numerical values attached to various features) but more

perspectives. J Nat Sci Biol Med. 2015;6: 24-8.

4. Fontaine O, Garner P, Bhan MK. Oral rehydration therapy: as a tool to simplify rehydration protocol in hands of

the simple solution for saving lives. BMJ. 2007;334(Suppl health workers and peripheral physicians in countries

1):s14. with limited resources. It basically helped to separate

5. Drucker G. 500,000 lives saved each year. ORT 10 years children who could be managed with oral hydration

after. Int Health News. 1988;9:2 alone (some dehydration) versus those who required

6. Houston KA, Gibb JG, Maitland K. Oral rehydration of immediate resuscitation with intravenous fluids (severe

malnourished children with diarrhoea and dehydration: A dehydration). It also eliminated the complexities of

systematic review. Wellcome Open Res. 2017;2:66. calculating biochemical compositions of rehydration

7. Falszewska A, Szajewska H, Dziechciarz P. Diagnostic

and maintenance fluids and just recommended using

accuracy of three clinical dehydration scales: a systematic

review. Arch Dis Child. 2018;103:383-8. Ringer’s lactate for all intravenous rehydration and

8. Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP). Available WHO oral rehydration salt (ORS) solution for all other

from: https://casp-uk.net/wp-content/uploads/2018/03/ rehydration. Although not scientifically very accurate, it

CASP-Systematic-Review-Checklist-Download.pdf. has served well in the field situations for which it was

Accessed April 28, 2018. created and recommended. However, it does not take

9. Ministry of Health and Family Welfare. National Family into consideration special problems of assessment of

Health Survey - 4. Available from: http://rchiips.org/nfhs/ dehydration in malnourished children or those children

pdf/NFHS4/India.pdf. Accessed April 29, 2018. who are unable to take adequate ORS solution because

10. Ravelomanana N, Razafindrakoto O, Rakotoarimanana

of vomiting. To overcome these possible lacunae, the

DR, Briend A, Desjeux JF, Mary JY. Risk factors for fatal

diarrhoea among dehydrated malnourished children in a WHO system can be even further simplified to divide

Madagascar hospital. Eur J Clin Nutr. 1995;49:91-7. diarrheal children into 2 categories: (i) those who are

alert and thirsty ready to drink adequate ORS; and (ii)

Pediatric Gastroenterologist’s Viewpoint those who are lethargic, drowsy or vomiting excessively,

unable to drink or retain adequate ORS. The former

Diarrheal dehydration is so common in pediatric practice category can be managed safely at peripheral level with

that it falls more in the domain of General Pediatrics oral rehydration under supervision while the latter

rather than of a Pediatric Gastroenterologist. category needs intravenous rehydration.

Nevertheless, a gastroenterologist could possibly view it

with more critical eyes. Diarrheal dehydration is not only fluid imbalance but

is also accompanied by a complex spectrum of

The systematic review by Falszewska, et al. [1] dyselectrolytemias, which need to be managed at

assessed the diagnostic accuracy of three clinical individual level. From the point of view of a

dehydration scales, and reported that all the three scales gastroenterologist, any clinical system of assessment of

had limited sensitivity and specificity over different dehydration that does not keep dyselectrolytemias in

degrees of dehydration as reported in different studies consideration, can only be a starting point of dehydration

analyzed for this review. They concluded that WHO [2] management, That further needs to be modified for

and Gorelick scales [3] are not helpful in assessment of individual patients.

dehydration both in developed and developing countries

while CDS scale [4] has better reliability in predicting Thus, for trained pediatricians, a system of

moderate to severe dehydration in developed countries. dehydration assessment and management, which we

It is important to note that individual signs of learnt as trainee residents in Pediatrics during late

dehydration have limited predictability and only a sixties, at the All India Institute of Medical Sciences

INDIAN PEDIATRICS 516 VOLUME 55__JUNE 15, 2018

JOURNAL CLUB

(New Delhi) was probably much better. We followed a 2004;145:201-7.

10-point score where increased thirst, sunken eyes, lost 5. Narchi H. Serum bicarbonate and dehydration severity in

skin turgor and dry mucus membranes were each given a gastroenteritis. Arch Dis Child. 1998;78:70-1.

score of one while acidosis (deep and fast breathing), 6. Molla AM, Rehman AM, Sarkar SA, Sack DA, Molla A.

Stool electrolyte content and purging rates in diarrhea

severe oliguria or anuria and shock were given 2 points

caused by rotavirus, enetrotoxigenic E coli and V. cholerae

each. The total score reflected the percentage of in children. J Pediatr. 1981;98:835-6.

dehydration and each percent score required

administration of 10 mL/kg rehydration fluids, which Pediatrician’s Viewpoint

were given over 8 hours together with maintenance

requirements (30-50 mL/kg for 8 hours). Interestingly, Dehydration due to diarrhea remains a major cause of

the rehydration fluid recommended was 1:2:3 solution, morbidity and mortality in developing countries.

with 1 part one-sixth molar Sodium bicarbonate, 2 parts Dehydration assessment tools with high diagnostic

Normal saline and 3 parts 5% Dextrose, acknowledging accuracy, good discriminative ability and interrater

the universality of metabolic acidosis [5] in moderate to reliability are of utmost importance in low- and middle-

severe diarrheal dehydration. income countries where children have to travel hours to

reach a healthcare facility and resources are limited.

Another simplified version of the same was giving Various diagnostic tools have been developed and used

50/100/150 mL/kg over 8 hours (which included over the years [1].

maintenance requirements for 8 hours) for mild (<5%),

moderate (5-10%) and severe dehydration (10%), So far in literature, the established reference

respectively. Here fluids containing 75 mEq/L of Sodium standard to assess degree of dehydration and validate

(N/2 saline) was used for rehydration, acknowledging these diagnostic scales, is the percentage difference

the fact of higher sodium losses in severe diarrhea. [6]. If between pre-illness and admission weight. In case of

acidosis was clinically apparent or if documented by non-availability of pre-illness weight, percentage weight

plasma bicarbonate levels, sodium bicarbonate was change before and after resuscitation correlates best with

given in bolus as one-sixth molar solution (3-5 mL/kg). percentage volume loss. But it is of retrospective use, has

Potassium (20 mEq/L) was added to IV fluids only after been shown to be poor predictor of dehydration among

passage of urine. Fluids containing 30-40 mEq/L of infants, and of no value in emergency settings [2].

sodium were used for maintenance purposes.

In this systematic review, the authors have analyzed

Either of these two systems adequately served the the evidence so far on diagnostic accuracy of three

purpose of initiating the rehydration therapy in large clinical dehydration scales namely CDS (created at

majority of diarrheal children not only for restoring hospital for sick children in Toronto), WHO

hydration status but also taking care of frequently (recommended by world health organization) and

observed electrolyte disturbances. Gorelick Scale (created at the children’s hospital of

Funding: None; Competing interests: None stated. Philadelphia) in identifying dehydration among children

SANTOSH KUMAR MITTAL with acute gastroenteritis, both in developing and

Consultant Pediatric Gastroenterologist, developed countries. All the three scales are based on

New Delhi, India. subjective findings which lack high sensitivity,

skmittal44@yahoo.com specificity and reliability. WHO scale integrated with

IMCI (Integrated Management of Childhood Illness) has

REFERENCES been universally followed in India based on expert

1. Falszewska A, Szajewska H, Dziechciarz P. Diagnostic opinion [3-5]. In 2008, ESPGHAN and ESPID had

accuracy of three clinical dehydration scales: a systematic concluded that none of the dehydration scales have been

review. Arch Dis Child. 2018;103:383-8. validated in individual patients, and there was

2. World Health Organization. Treatment of Diarrhea: A insufficient evidence to support its use for management

Manual for Physicians and Other Senior Health Workers. of individual child. A decade later, the authors conclude

Available from: http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/

that the clinical scales evaluated provide some improved

43209/19241593180.pdf. Accessed May 07, 2018.

3. Gorelick MH, Shaw KN, Murphy KD. Validity and diagnostic accuracy but their ability to identify children

reliability of clinical signs in the diagnosis of dehydration with some dehydration and without dehydration is

in children. Pediatrics. 1997:99:e6 suboptimal. There is limited evidence in favour of CDS

4. Friedman JN, Goldman RD, Srivastava R, Parkin PC. in ruling-in severe dehydration in high income settings

Development of a clinical dehydration scale for use in while WHO and Gorelick scales are not helpful for

children between 1 and 36 months of age. J Pediatr. assessing dehydration.

INDIAN PEDIATRICS 517 VOLUME 55__JUNE 15, 2018

JOURNAL CLUB

Clinical scales which seem to perform well in high- REFERENCES

resource settings might not be accurate in low-income

1. Jauregui J, Nelson D, Choo E, Stearns B, Levine AC,

countries where there are higher number of Liebmann O, et al. External validation and comparison of

undernourished children, severe forms of diarrhea (e.g., three pediatric clinical dehydration scales. PLoS One.

cholera) and the first contact is with community health 2014;9:e95739.

workers who have limited training. Inappropriate 2. Pruvost I, Dubos F, Chazard E, Hue V, Duhamel A,

categorization of children with diarrhea can cause direct Martinot A. The value of body weight measurement to

harm to the child and lead to misuse of limited resources assess dehydration in children. PLoS One. 2013; 8:e55063.

and longer hospital stays. 3. WHO. The Treatment of Diarrhoea: A Manual for

Physicians and Other Senior Health Workers. Geneva:

This review highlights the need for more research World Health Organization; 2005.

into better bedside methods and objective tools for 4. WHO. Handbook: IMCI Integrated Management of

detecting the severity of dehydration in low-income Childhood Illness. Geneva: World Health Organization;

countries. Newer scales like Dhaka score need to be 2005.

5. Levine AC, Glavis-Bloom J, Modi P, Nasrin S, Atika

externally validated [5]. Other imaging tools like

B, Rege S, et al. External validation of the DHAKA score

bedside ultrasound and capillary digital videography are and comparison with the current IMCI algorithm for the

also promising [6]. assessment of dehydration in children with diarrhoea: a

Funding: None; Competing interests: None stated. prospective cohort study. Lancet Glob Health.

2016;4:e744-51.

SHIVANI DESWAL 6. Freedman SB, Vandermeer B, Milne A, Hartling L.

Department of Pediatrics, Pediatric Emergency Research Canada Gastroenteritis

PGIMER & Dr RML Hospital, Study Group. Diagnosing clinically significant dehydration

New Delhi, India. in children with acute gastroenteritis using noninvasive

shivanipaeds@gmailcom methods: a meta-analysis. J Pediatr. 2015;166:908-16.

INDIAN PEDIATRICS 518 VOLUME 55__JUNE 15, 2018

You might also like

- Treatment Guidelines (Nigeria)Document116 pagesTreatment Guidelines (Nigeria)Laarny De Jesus Garcia - Ame100% (1)

- Keith Edwards Score For Diagnosis of Tuberculosis. IJP.03Document3 pagesKeith Edwards Score For Diagnosis of Tuberculosis. IJP.03Diego Bedon AscurraNo ratings yet

- 07-Acute Diarrheal Diseases (Ward Lectures)Document33 pages07-Acute Diarrheal Diseases (Ward Lectures)Zaryab Umar100% (1)

- Irene EvnDocument4 pagesIrene EvnashniemagdaliNo ratings yet

- The Value of Body Weight MeasuDocument7 pagesThe Value of Body Weight MeasuDina AryaniNo ratings yet

- Summ 1619Document8 pagesSumm 1619novialbarNo ratings yet

- Nested Case Control StudyDocument16 pagesNested Case Control Studyqtftwkwlf100% (1)

- The Value of Body Weight MeasuDocument12 pagesThe Value of Body Weight MeasuDina AryaniNo ratings yet

- Motivations For Weight Loss in Adolescents With Overweight and Obesity A Systematic ReviewDocument8 pagesMotivations For Weight Loss in Adolescents With Overweight and Obesity A Systematic ReviewBruno SilvaNo ratings yet

- BackgroundDocument16 pagesBackgroundLegionella ComanderNo ratings yet

- Zhang 2020Document14 pagesZhang 2020Belen GaleraNo ratings yet

- Cochrane BVS: Oral Zinc For Treating Diarrhoea in ChildrenDocument25 pagesCochrane BVS: Oral Zinc For Treating Diarrhoea in ChildrenLaura AnguloNo ratings yet

- Endoscopic Sleeve Gastroplasty As An Early Tool Against Obesity: A Multicenter International Study On An Overweight PopulationDocument6 pagesEndoscopic Sleeve Gastroplasty As An Early Tool Against Obesity: A Multicenter International Study On An Overweight PopulationduranaxelNo ratings yet

- GROUP 4 EBP On Renal NursingDocument7 pagesGROUP 4 EBP On Renal Nursingczeremar chanNo ratings yet

- Assessment of Self Management in Patients With DiaDocument9 pagesAssessment of Self Management in Patients With DiaPaula Francisca Moraga HidalgoNo ratings yet

- Classification of Feeding and Eating DisordersDocument13 pagesClassification of Feeding and Eating DisordersMagito JayaNo ratings yet

- Evidence Analysis Library Review of Best Practices For Performing Indirect Calorimetry in Healthy and NoneCritically Ill IndividualsDocument32 pagesEvidence Analysis Library Review of Best Practices For Performing Indirect Calorimetry in Healthy and NoneCritically Ill IndividualsNutricion Deportiva NutrainerNo ratings yet

- Saccharomyces Boulardii: Meta-Analysis: For Treating Acute Diarrhoea in ChildrenDocument8 pagesSaccharomyces Boulardii: Meta-Analysis: For Treating Acute Diarrhoea in ChildrenJOSE LUIS PENAGOSNo ratings yet

- Lo Per Amide Therapy For Acute Diarrhea in Children Systematic Review and Meta-AnalysisDocument11 pagesLo Per Amide Therapy For Acute Diarrhea in Children Systematic Review and Meta-AnalysisAprilia R. PermatasariNo ratings yet

- Characteristics of Pediatric Patients With Diarrhea in Indonesia: A Laboratory-Based ReportDocument8 pagesCharacteristics of Pediatric Patients With Diarrhea in Indonesia: A Laboratory-Based ReportDrnNo ratings yet

- Running Head: Cardiovascular Disease Prevention 1Document8 pagesRunning Head: Cardiovascular Disease Prevention 1Sammy GitauNo ratings yet

- Original Article: Saudi Journal of Kidney Diseases and TransplantationDocument7 pagesOriginal Article: Saudi Journal of Kidney Diseases and TransplantationRontiNo ratings yet

- Childhood Obesity Is Associated With A High DegreeDocument14 pagesChildhood Obesity Is Associated With A High DegreeMahd oNo ratings yet

- 2014 Immediate Fluid Management of Children With Severe Febrile Illness and Signs of Impaired Circulation in Low-Income SettingsDocument8 pages2014 Immediate Fluid Management of Children With Severe Febrile Illness and Signs of Impaired Circulation in Low-Income SettingsVladimir BasurtoNo ratings yet

- Complete Summary: Guideline TitleDocument27 pagesComplete Summary: Guideline TitleRudi ArdiyantoNo ratings yet

- Metanalisis 2015Document15 pagesMetanalisis 2015Pitu MinvielleNo ratings yet

- Steroids For Airway EdemaDocument7 pagesSteroids For Airway EdemaDamal An NasherNo ratings yet

- EDA. Pediatrics 2010Document12 pagesEDA. Pediatrics 2010Carkos MorenoNo ratings yet

- 2018 Article 1006Document9 pages2018 Article 1006Daniel PuertasNo ratings yet

- Obesity Reviews - 2023 - Blaxall - Obesity Intervention Evidence Synthesis Where Are The Gaps and Which Should We AddressDocument18 pagesObesity Reviews - 2023 - Blaxall - Obesity Intervention Evidence Synthesis Where Are The Gaps and Which Should We AddressPatyNo ratings yet

- NST Supported by Original Data (Age)Document18 pagesNST Supported by Original Data (Age)Rika LedyNo ratings yet

- Diagnostic Approach in Children With Short Stature PDFDocument12 pagesDiagnostic Approach in Children With Short Stature PDFHandre PutraNo ratings yet

- Nutrients 13 03640 v2Document20 pagesNutrients 13 03640 v2Sophia van de MeerakkerNo ratings yet

- Head Et Al-2018-Cochrane Database of Systematic ReviewsDocument4 pagesHead Et Al-2018-Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviewsasujan58pNo ratings yet

- WNL 2022 201574Document10 pagesWNL 2022 201574triska antonyNo ratings yet

- Taylor Et Al-2006-Australian and New Zealand Journal of Public HealthDocument9 pagesTaylor Et Al-2006-Australian and New Zealand Journal of Public HealthRahmat ullahNo ratings yet

- Nutritional Assessment of Children With CHD CompareDocument9 pagesNutritional Assessment of Children With CHD CompareIntan Robi'ahNo ratings yet

- Short Report: Education and Psychological Aspects Modification and Validation of The Revised Diabetes Knowledge ScaleDocument5 pagesShort Report: Education and Psychological Aspects Modification and Validation of The Revised Diabetes Knowledge ScaleadninaninNo ratings yet

- Jurnal Cbe 1Document21 pagesJurnal Cbe 1Dewi SurayaNo ratings yet

- Influence of Nutritional Status On Clinical Outcomes in Critically Ill ChildrenDocument5 pagesInfluence of Nutritional Status On Clinical Outcomes in Critically Ill ChildrenAnonymous h0DxuJTNo ratings yet

- Influence of Nutritional Status On Clinical Outcomes in Critically Ill ChildrenDocument5 pagesInfluence of Nutritional Status On Clinical Outcomes in Critically Ill ChildrenIvana YunitaNo ratings yet

- Lins 2016Document8 pagesLins 2016David AzevedoNo ratings yet

- 1625-Article Text-4407-1-10-20230707Document14 pages1625-Article Text-4407-1-10-20230707dewa putra yasaNo ratings yet

- Pedroso Et Al. 2021Document12 pagesPedroso Et Al. 2021seriesediversosNo ratings yet

- Literature Review of Gestational DiabetesDocument10 pagesLiterature Review of Gestational Diabetesc5pnw26s100% (1)

- File 2Document18 pagesFile 2Ikke PrihatantiNo ratings yet

- Severity Scoring Systems: Are They Internally Valid, Reliable and Predictive of Oxygen Use in Children With Acute Bronchiolitis?Document7 pagesSeverity Scoring Systems: Are They Internally Valid, Reliable and Predictive of Oxygen Use in Children With Acute Bronchiolitis?Ivan VeriswanNo ratings yet

- CAGE Questionnaire For Alcohol MisuseDocument10 pagesCAGE Questionnaire For Alcohol MisuseJeremy BergerNo ratings yet

- Current Databases On Biological Variation: Pros, Cons and ProgressDocument10 pagesCurrent Databases On Biological Variation: Pros, Cons and ProgressCarlos PardoNo ratings yet

- Inter-Rater Reliability of The Subjective Global Assessment A Systematic Literature ReviewDocument4 pagesInter-Rater Reliability of The Subjective Global Assessment A Systematic Literature ReviewzxnrvkrifNo ratings yet

- Guidelines For Managing Acute Gastroenteritis Based On A Systematic Review of Published ResearchDocument7 pagesGuidelines For Managing Acute Gastroenteritis Based On A Systematic Review of Published ResearchnikopkunairNo ratings yet

- Treatment of Pediatric ObesityDocument6 pagesTreatment of Pediatric Obesitymaxime wotolNo ratings yet

- Nutrition Screening AssesmentDocument11 pagesNutrition Screening AssesmentIrving EuanNo ratings yet

- Subjective Global Assessment in Chronic Kidney Disease - A ReviewDocument10 pagesSubjective Global Assessment in Chronic Kidney Disease - A ReviewDiana Laura MtzNo ratings yet

- BVS Odontologia: Informação e Conhecimento para A SaúdeDocument3 pagesBVS Odontologia: Informação e Conhecimento para A SaúdeGabriel SilvaNo ratings yet

- HBMOSDocument11 pagesHBMOSekaNo ratings yet

- Evaluation of Nutrition Status Using The Subjective Global Assessment: Malnutrition, Cachexia, and SarcopeniaDocument15 pagesEvaluation of Nutrition Status Using The Subjective Global Assessment: Malnutrition, Cachexia, and SarcopeniaLia. OktarinaNo ratings yet

- The Endocrine Society Clinical Practice Guidelines: A Self-AssessmentDocument4 pagesThe Endocrine Society Clinical Practice Guidelines: A Self-AssessmentRiskha Febriani HapsariNo ratings yet

- Bookshelf NBK315902Document18 pagesBookshelf NBK315902Lucas WillianNo ratings yet

- M CAD Ermatol PrilDocument1 pageM CAD Ermatol PrilValentina AdindaNo ratings yet

- NCP 10589Document8 pagesNCP 10589Mita AriniNo ratings yet

- Complementary and Alternative Medical Lab Testing Part 5: GastrointestinalFrom EverandComplementary and Alternative Medical Lab Testing Part 5: GastrointestinalNo ratings yet

- Gastroenteritis in Children Part II. Prevention and Management 2012Document5 pagesGastroenteritis in Children Part II. Prevention and Management 2012Douglas UmbriaNo ratings yet

- Acute Viral Gastroenteritis in Adults UpToDateDocument12 pagesAcute Viral Gastroenteritis in Adults UpToDateItzrael DíazNo ratings yet

- Management of Medical Complications in Severe Acute Malnutrition (SAM)Document4 pagesManagement of Medical Complications in Severe Acute Malnutrition (SAM)Archana SinghNo ratings yet

- Surprised Samples With Coaching Samples (1) 2Document55 pagesSurprised Samples With Coaching Samples (1) 2EmmanuellaNo ratings yet

- Doh 07Document37 pagesDoh 07Malack ChagwaNo ratings yet

- New Pediatric Guideline Hargeisa Group Hospital by DR NelsonDocument54 pagesNew Pediatric Guideline Hargeisa Group Hospital by DR NelsonKhadar mohamedNo ratings yet

- 10 Steps Wall ChartDocument2 pages10 Steps Wall ChartTommy CharwinNo ratings yet

- Chart Booklet 2013 Final July 2013Document46 pagesChart Booklet 2013 Final July 2013Alazar shenkoruNo ratings yet

- Acute Viral Gastroenteritis in AdultsDocument13 pagesAcute Viral Gastroenteritis in AdultsyessyNo ratings yet

- DGDFHDFDocument6 pagesDGDFHDFFaye IlaganNo ratings yet

- Nelson's MCQ'sDocument150 pagesNelson's MCQ'sDrSheika Bawazir93% (40)

- Oral Rehydration Solution:: Future ProspectDocument48 pagesOral Rehydration Solution:: Future ProspectmustikaarumNo ratings yet

- Oralade Dog BrochureLQDocument4 pagesOralade Dog BrochureLQKatrina MarshallNo ratings yet

- CPG - Acute Infectious DiarrheaDocument52 pagesCPG - Acute Infectious DiarrheaJim Christian EllaserNo ratings yet

- Kwashior and MarasmusDocument17 pagesKwashior and Marasmuszuby_0302No ratings yet

- Approach To The Child With Acute Diarrhea in Resource-Limited Countries - UpToDateDocument17 pagesApproach To The Child With Acute Diarrhea in Resource-Limited Countries - UpToDateNedelcu MirunaNo ratings yet

- PharmCal Lab Finals (H2O2, Alum, Aluminum Magnesium Hydoxide Gel, ORS, Cupric Sulfate)Document10 pagesPharmCal Lab Finals (H2O2, Alum, Aluminum Magnesium Hydoxide Gel, ORS, Cupric Sulfate)a yellow flowerNo ratings yet

- Maintaining Fluid & Electrolyte Balance in The BodyDocument124 pagesMaintaining Fluid & Electrolyte Balance in The BodyKingJayson Pacman06100% (1)

- Child Bronchiolitis 1Document2 pagesChild Bronchiolitis 1sarooah1994100% (2)

- Who Dehidrasi PG 17 PDFDocument52 pagesWho Dehidrasi PG 17 PDFSasha ManoNo ratings yet

- Hidrasec Adults 9-11-07Document81 pagesHidrasec Adults 9-11-07Christian Gallardo, MD100% (1)

- Cisplatin Monograph 1jul2016Document11 pagesCisplatin Monograph 1jul2016Kurnia AnharNo ratings yet

- Food and Personal Hygiene Perceptions and PracticesDocument8 pagesFood and Personal Hygiene Perceptions and PracticesFa MoNo ratings yet

- Diarrhea GuidelineDocument29 pagesDiarrhea GuidelineMonica GabrielNo ratings yet

- Safe Water School: Training ManualDocument120 pagesSafe Water School: Training Manuallisa.piccininNo ratings yet

- Diarrhoea +/ Vomiting: Nurse Practitioner Clinical Protocol Emergency DepartmentDocument10 pagesDiarrhoea +/ Vomiting: Nurse Practitioner Clinical Protocol Emergency DepartmentLalaine RomeroNo ratings yet

- Pedia Exam QuestionsDocument6 pagesPedia Exam QuestionsbNo ratings yet

- Acute Gastroenteritis in Children: Prepared By: Prof. Elizabeth D. Cruz RN, ManDocument12 pagesAcute Gastroenteritis in Children: Prepared By: Prof. Elizabeth D. Cruz RN, ManChaii De GuzmanNo ratings yet