Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Beyond Diversity Training - A Social Infusion For Cultural Inclusion

Beyond Diversity Training - A Social Infusion For Cultural Inclusion

Uploaded by

JACKSON MEDDOWSOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Beyond Diversity Training - A Social Infusion For Cultural Inclusion

Beyond Diversity Training - A Social Infusion For Cultural Inclusion

Uploaded by

JACKSON MEDDOWSCopyright:

Available Formats

09HRM47_2chavez 5/7/08 11:22 AM Page 331

BEYOND DIVERSITY TRAINING: A

SOCIAL INFUSION FOR CULTURAL

INCLUSION

C A R O LY N I . C H A V E Z A N D J U D I T H Y. W E I S I N G E R

Contemporary organizations, in an effort to reap the benefits of a diverse

workforce, continue to spend millions of dollars on diversity training despite

the tendency of such training to either fail or result in less than desired out-

comes. We introduce an alternative, strategic approach to organizational

diversity designed to create a more inclusive “culture of diversity.” This long-

term, relational approach emphasizes an attitudinal and cultural transforma-

tion, requiring managers to “break barriers” by moving away from “manag-

ing diversity” toward “managing for diversity” to capitalize on the unique

perspectives of a diverse workforce. © 2008 Wiley Periodicals, Inc.

Introduction have cultural diversity programs (Kimley,

1997), and scholars foretell a continuance of

n 1997, Helen Hemphill and Ray Haines this trend as the workforce population

I published a book elucidating the failure

of discrimination, harassment, and

diversity training programs. These au-

thors studied 65 major companies over

three years and found that many programs

not only failed to accomplish the intended

goals, but also resulted in social conflict—

becomes increasingly diverse in terms of

race, gender, and age (Bureau of Labor Statis-

tics, 2004; Jayne & Dipboye, 2004), and as or-

ganizations become more global (Holladay &

Quinones, 2005). Why then, do American

companies continue to invest billions of dol-

lars annually on diversity training?

divisiveness, hostility, backlash, and an The answer is simple. On a strategic

increase in litigation. Likewise, Stephen level, U.S. managers perceive diversity man-

Paskoff (1996) found overwhelming evi- agement as a means to better use talent and

dence that disenchantment with diversity to increase creativity within organizations

programs was rampant. He deemed such (T. Cox & Blake, 1991; Gilbert & Ivancevich,

programs to be a waste of time, resulting in 2000; Nkomo & Cox, 1996), as a method to

superficial results at best. Despite many such attract and retain diverse employees in the

findings, 74% of all Fortune 500 companies face of shifting demographic labor markets

Correspondence to: Carolyn I. Chavez, Assistant Professor, College of Business, P.O. Box 30001/MSC 3DJ, New Mex-

ico State University, Las Cruces, NM 88003, Phone: 505-646-1266, Fax: 505-646-1372, E-mail: cchavez@nmsu.edu.

H u m a n R e s o u r c e M a n a g e m e n t , Summer 2008, Vol. 47, No. 2, Pp. 331–350

© 2008 Wiley Periodicals, Inc.

Published online in Wiley InterScience (www.interscience.wiley.com).

DOI: 10.1002/hrm.20215

09HRM47_2chavez 5/7/08 11:22 AM Page 332

332 HUMAN RESOURCE MANAGEMENT, Summer 2008

(Jayne & Dipboye, 2004), and as an avenue plain “good for business . . . as it lifts morale,

for developing effective interactions with brings greater access to new segments of the

people from different cultures. In short, the marketplace, and enhances productivity” (p.

effective management of diversity has 79). Specifically, our new approach has three

become an important business imperative objectives:

that is perceived to affect organizational

functioning and competitiveness (Harvey, 1. Establish a relational culture within

1999; Kuczynski, 1999), and to result in which people feel proud of their own

increased employee morale, retention, and uniqueness, while becoming socially

days worked (Hemphill & Haines, 1998). integrated into a larger group by cele-

Hence, organizations continue to push brating the “me” within the “we.”

ahead with a variety of diversity training 2. Maintain an inclusive culture within

programs. which employees are intrinsically moti-

The issues surrounding diversity training vated to take ownership of the learning

programs are obvious, real, and in experience and to learn from each other

need of a resolution. However, so that organizational members can dis-

One problem with the solution is neither obvious cover and appreciate multiple perspec-

nor simple. One problem with tives.

current approaches current approaches stems from 3. Incorporate an organizational strategy

the attitudes and processes used that capitalizes on the multiple perspec-

stems from the to implement diversity programs. tives individuals contribute to creativity,

Therefore, we advocate for a re- productivity, organizational attractive-

attitudes and

alignment of the way managers ness, and employee well-being.

processes used to currently think about and con-

duct diversity training. This We foresee accomplishing of these objec-

implement diversity change requires an attitudinal tives as providing a realistic opportunity for

shift away from a “managing di- the emergence of an organizational culture

programs.

versity” intendance toward a that promotes both diversity and inclusion,

strategy of “managing for diver- and that supports a strategy capitalizing on

sity.” Research indicates that or- the contributions of a variety of insights

ganizational culture directly impacts busi- born of personal experiences. It is within

ness performance. Therefore, we recommend such a culture that trainers may have their

placing a strategic emphasis on building a best chance to present various mandated

culture that draws out and acts on the training programs without evoking negative

unique perspectives a diverse workforce can emotional reactions such as guilt, shame,

bring to organizations. defensiveness, stereotyping, and/or resent-

The purpose of this article is to introduce ment.

an alternative approach to traditional diver- We first present an overview of the liter-

sity programs and to stimulate new ideas ature on contemporary diversity training

among human resource practitioners and perspectives, followed by a section summa-

scholars. Drawing from current research, we rizing the shortcomings of many current

use the terms “inclusion” and “diversity” as approaches. We then present an argument

separate but overlapping constructs (Rober- for why we need to “break barriers” by taking

son, 2006). We report on the success of using the next step toward an inclusive diversity

this method in various classroom “organiza- culture, followed by our philosophy in

tions” and then illustrate how business or- developing the proposed approach. To un-

ganizations might use this process to capital- derstand the basis by which this approach

ize on unique perspectives as a strategy for can succeed, we present a short overview of

business success. In addition to the advan- the literature on learning and intrinsic moti-

tages of a diverse workplace already listed, vation. We then share our classroom experi-

D. A. Thomas and Ely (1996) say it is just ences and discuss the transference of this

Human Resource Management DOI: 10.1002/hrm

09HRM47_2chavez 5/7/08 11:22 AM Page 333

Beyond Diversity Training: A Social Infusion for Cultural Inclusion 333

process from a classroom organization to an “managing for diversity” approach, which

ongoing diversity approach in a workforce centers on building an inclusive organiza-

organization. We include suggestions for tional culture within which diversity pro-

evaluating the approach in organizations, grams might be undertaken more effectively.

followed by final thoughts. We use T. Cox’s (1994) definition of di-

versity as being “the representation, in one

Contemporary Perspectives on social system, of people with distinctly dif-

ferent group affiliations of cultural signifi-

Diversity Training

cance” (p. 6); where group affiliations in-

Trainers use diversity training as a means to clude both demographic variables, such as

meet many objectives, such as attracting and race, gender, religion, and cul-

retaining customers and productive workers; ture, and nondemographic vari-

maintaining high employee morale; and/or ables, such as personality type Regardless of the

fostering understanding and harmony be- and political party. However, or-

tween workers (Wentling & Palma-Rivas, ganizations often emphasize rep- objectives, periodic

1999). Some programs are designed to ensure resentational diversity at the ex-

a desired workforce composition that pense of pluralistic diversity, training programs

includes underrepresented groups. Others at- which emphasizes incorporating are by far the most

tempt to capitalize on perceived diversity diverse views into the work of the

benefits by increasing external relationships organization (Weisinger & Sali- commonly used

with underrepresented groups. Some diver- pante, 2005). Roberson (2006) as-

sity procedures are designed to avoid litiga- serts that current diversity re- diversity activity.

tion, while others focus on employee train- search assumes the integration of

Unfortunately,

ing for developing awareness of and diverse individuals in an organi-

sensitivity to discriminatory and prejudicial zation. To insure such integration periodic training

behaviors. In one study, researchers identi- we incorporate a related con-

fied the top three goals of diversity training cept—inclusion—which refers to programs often fail

to be changing trainee workplace behavior, the degree diverse individuals

or fall short of

promoting organizational change, and in- “are allowed to participate and

creasing trainee awareness of discrimination are enabled to contribute fully” meeting the

issues (Bendick, Egan, & Lofhjelm, 1998). (Miller, 1998, p. 151).

We can measure diversity training effec- Roberson (2006) points out intended outcomes.

tiveness several ways to include administer- that it is unclear whether diver-

ing employee opinion surveys, calculating sity and inclusion represent fun-

turnover and absenteeism costs related to damentally different concepts, or whether

underrepresented workers, and by monitor- they simply reflect changing language in re-

ing minority representation (Martinez, sponse to diversity backlash. Her empirical

1995). For example, Nextel Communications study showed that “inclusion” and “diver-

calculated (through participant surveys) a sity” are separate but overlapping concepts.

9.7% increase in retention as a result of its di- Accordingly, we see both constructs as being

versity awareness training program, and an necessary and mutually beneficial to our vi-

overall 163% return on investment (ROI) sion of “managing for diversity.” While re-

from the program (“Getting Results from Di- cruitment of a diverse workforce is impor-

versity Training,” 2003). Regardless of the tant, it is by “managing for diversity”

objectives, periodic training programs are by (creating an inclusive culture) that we stand

far the most commonly used diversity activ- the best chance of lowering turnover among

ity (Wentling & Palma-Rivas, 1999). Unfortu- diverse employees, attracting new employ-

nately, periodic training programs often fail ees, and realizing the benefits from such a

or fall short of meeting the intended out- labor force. In a study illustrating the rele-

comes. The above diversity training objec- vance of individual perceptions to work out-

tives are naturally occurring outcomes of our comes, T. Cox (1993) found that employees’

Human Resource Management DOI: 10.1002/hrm

09HRM47_2chavez 5/7/08 11:22 AM Page 334

334 HUMAN RESOURCE MANAGEMENT, Summer 2008

perceptions of being valued by their organi- tiveness paradigm. This paradigm may lead

zation significantly affected their conscien- to work innovations and enhanced business

tiousness, job involvement, and innovative- results, as diverse perspectives can expand

ness. Therefore, it follows that employees management’s views about what issues are

who feel valued as individuals are more relevant and can help employees to frame

likely to contribute to an organization’s pro- such issues in new and creative ways (D. A.

ductivity and profitability. Thomas & Ely, 1996).

D. A. Thomas and Ely (1996) suggest The more relational “managing for diver-

three paradigms that reflect diver- sity” approach that we propose here is con-

sity approaches in organizations. sistent with D. A. Thomas and Ely’s (1996)

While recruitment The discrimination-and-fairness learning-and-effectiveness paradigm. We

paradigm is the predominant stress the creation of a culture within which

of a diverse one, wherein leaders view diver- people can be proud of their unique perspec-

sity through a lens of equal em- tives and are willing and even eager to share

workforce is ployment, fairness, recruitment, them. Without such an atmosphere, man-

important, it is by and compliance. This paradigm agers cannot incorporate these perspectives

reflects an “assimilationist” view, into the “work of the organization” and they

“managing for with a focus on “color- and gen- miss strategic opportunities to capitalize on

der-blind conformism” (p. 85). these insights. Unfortunately, not enough di-

diversity” (creating The access-and-legitimacy para- versity integration efforts are taking place.

digm emphasizes the acceptance Instead, many managers mistakenly try to

an inclusive culture)

and celebration of differences. Ac- reap the benefits of a diverse workforce by

that we stand the cordingly, a demographically di- conducting training in ways that often cul-

verse workforce is better suited to minate in undesirable outcomes. In the next

best chance of help the organization access dif- section, we present a summary of the weak-

ferentiated market segments. nesses of many diversity training programs.

lowering turnover

Thus, as opposed to assimilation,

among diverse the access-and-legitimacy view is Shortcomings of Nonintegrative

predicated on differentiation. In

employees,

Approaches to Diversity Training

contrast, D. A. Thomas and Ely

see learning-and-effectiveness to While few data exist on diversity training ef-

attracting new

be an emerging paradigm in or- fectiveness, there is significant anecdotal ev-

employees, and ganizations. Rather than reflect- idence that many organizational diversity

ing either assimilation or differ- programs have either failed or brought about

realizing the entiation, the authors suggest less than desired results. Some problems

that the learning-and-effective- cited in the literature include backlash, lack

benefits from such a ness paradigm centers on integra- of needs assessment, inadequate evaluation,

labor force. tion. This emerging paradigm and a lack of contextual relevance.

Backlash may occur in diversity training

. . . enables [companies] to in- efforts because of an overemphasis on differ-

corporate employees’ perspec- ences that uses “blame and shame” ap-

tives into the main work of the organi- proaches to criticize majority-group partici-

zation and to enhance work by pants and/or strengthens existing

rethinking primary tasks and redefin- stereotypes about minority-group members

ing markets, products, strategies, mis- (Beaver, 1995; Christensen & Nemetz, 1996).

sion, business practices, and even cul- Such approaches regularly result in defen-

tures. . . . (p. 85) siveness and the labeling of identity groups

that may perpetuate stereotyping instead of

Diversity training and broader ap- promoting harmony (P. L. Cox, 2001). Diver-

proaches to organizational diversity have sity backlash also may result from ill-con-

not largely embraced the learning-and-effec- ceived training programs (Mobley & Payne,

Human Resource Management DOI: 10.1002/hrm

09HRM47_2chavez 5/7/08 11:22 AM Page 335

Beyond Diversity Training: A Social Infusion for Cultural Inclusion 335

1992). (See Table I for a summary of factors 1998; Hemphill & Haines, 1998; Kennedy,

and perceptions identified by the above re- 1995).

searchers that contribute to backlash out- Likewise, Hite and McDonald (2006)

comes.) warn us of failing to adequately assess diver-

According to Hite and McDonald (2006), sity training programs. Interpretation errors,

the lack of a front-end needs assessment may they assert, may occur when the evaluation

also lead to undesired backlash outcomes via primarily occurs at the participation reaction

unclear training objectives. A good front-end level rather than at the behavioral or cultural

needs assessment presumes that trainers are change level. This criticism suggests that

aware of organizational goals and adjust while training may provide knowledge, it

training efforts to meet those goals. Doing so does not necessarily result in learning unless

is part of a smart organizational strategy for a behavioral change occurs (for a review of

leveraging the benefits of a diverse work- learning theories, see Knowles, Holton, &

force. The likelihood of obtaining a poor out- Swanson, 2005). Therefore, we need to eval-

come increases when diversity training ef- uate actual changes in behavior and/or the

forts occur as a reactive tactic to culture before we assume a successful inter-

environmental demands rather than as a vention. Hence, we suggest methods for as-

proactive, strategic approach to meeting sessing the proposed “managing for diver-

identified organizational needs. For example, sity” approach in the section on “Evaluating

human resource practitioners have expressed Training Effectiveness” and we direct readers

a concern that diversity training may be too to measurement instruments.

narrow (e.g., emphasizing legally mandated These problematic issues suggest that or-

issues), focusing on the interest of a few di- ganizations must place more emphasis on

verse groups at the expense of others (Brown, long-term diversity efforts that ultimately

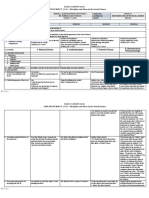

Factors and Perceptions Leading to Backlash According to Beaver (1995)1; Christensen and

TABLE I

Nemetz (1996)2; and Mobley and Payne (1992)3

• Deep-seated biases and prejudices within employees1,3

• Frustration among whites and males at being cast as the oppressors1

• A perception of political correctness as a threat to First Amendment rights2,3

• The perception that race and gender issues are a political football3

• Frustration with being politically correct to the point that well-intentioned people, when making a

mistake, are not recognized for their good intentions1,2,3

• A belief that the point of diversity training is to change white men3

• Sensationalistic journalism that may underscore stereotypes and spawn scapegoats3

• A perception that focusing on multiculturalism will dissolve the unity of the United States2

• A history of poorly implemented and misused affirmative action and EEO programs that has

stigmatized how employees view diversity training3

• A “we vs. they” syndrome—the human tendency to like those who are similar to oneself and to

dislike those who are different than oneself1

• Competition when diverse groups perceive the need to compete against one another for jobs and

promotions. This is especially salient in economically challenging times1,3

• The failure to incorporate diversity training into the organization’s overall approach to a diverse

workforce3

• Training initiatives that fail to respect individual styles3

Human Resource Management DOI: 10.1002/hrm

09HRM47_2chavez 5/7/08 11:22 AM Page 336

336 HUMAN RESOURCE MANAGEMENT, Summer 2008

lead to cultural change, by reconfiguring cur- found that workers’ ability to form support-

rent institutional practices. In an effort to ive relationships at work is among the most

identify the next step, we draw on other re- powerful of 12 predictors of a highly produc-

search streams in human behavior with the tive workplace (Shellenbarger, 2000; cf.

goal of identifying effective strategies of Bacharach et al., 2005). Thus, one approach

“managing for diversity.” to encouraging diversity appreciation among

employees is to cultivate a culture that is

The Call for a Cultural Change supportive of relationships among employ-

ees. Interestingly, diversity researchers have

Through a Relational Approach

made the following observations in support

Jayne and Dipboye (2004) purport that the of such a relational approach:

success of diversity programs is dependent

on organizational situational factors such as • The success of a diversity initiative is

culture, strategy, and operating more probable when employees identify

environments. These authors with the organization as well as with

The willingness and warn that the jobs people per- their teams (Jayne & Dipboye, 2004).

form and their individual charac- • Kochan et al. (2003, p. 9) reported,

ability to accept, teristics influence the success of “Training- and development-focused HR

training initiatives. Therefore, HR practices, including coaching, open com-

understand, and managers must pay attention to munications and interactive listening, as

leverage cultural the distinct organizational con- well as opportunities for development,

text for which they are develop- reduced the negative effects of racial di-

differences is, in ing the training program. There versity on constructive group processes.”

simply is no “one-size-fits-all” so- • Organizations can increase diversity ef-

itself, a process of lution to diversity issues, as the fectiveness by incorporating aspects of

goal of each organization is group learning and diversity perspectives

cultural change. Yet

unique depending on the em- in organizations (e.g., by focusing on

many traditional ployees, environment, and cul- how groups learn from and across differ-

ture. ences; Foldy, 2004).

diversity programs Other advocates of a cultural • The business benefits of diversity may

change perspective suggest that depend on the particular organizational

continue to reflect

businesses modify their culture to context or situation (Jayne & Dipboye,

misguided meet diversity objectives rather 2004; Kochan et al., 2003).

than relying on employees to • The view of “cultural identity” as a so-

expectations about change behaviors in response to cially constructed concept emphasizes

one-time training programs (God- the role that social context plays in shap-

what diversity

dard, 1989; Paskoff, 1996; Ragins, ing those demographic characteristics

training can really 1997, R. R. Thomas, 1996). Suc- that are visible and job-related (Ely &

cessful programs, R. R. Thomas Thomas, 2001).

achieve. argues, require commitment from

all members of the organization The foregoing observations point to the

regardless of position. Top man- importance of group processes in the success

agement must model the behav- of a transition to an effective culture of di-

ioral change if a cultural transformation is to versity. Further, the willingness and ability to

take place. accept, understand, and leverage cultural dif-

Additionally, recent diversity research ferences is, in itself, a process of cultural

emphasizes the importance of supportive change. Yet many traditional diversity pro-

peer relations in the workplace (see grams continue to reflect misguided expecta-

Bacharach, Bamberger, & Vashdi, 2005, for a tions about what diversity training can really

summary of research on this theme). For ex- achieve. For example, many echo an expec-

ample, a Gallup survey of 400 companies tation that one-shot or even multiple train-

Human Resource Management DOI: 10.1002/hrm

09HRM47_2chavez 5/7/08 11:22 AM Page 337

Beyond Diversity Training: A Social Infusion for Cultural Inclusion 337

ing sessions are enough to affect widespread we do not appreciate the differences of oth-

behavioral and structural change within an ers, it is unlikely that we will appreciate their

organization. Others advocate raising the contributions.

status and voice of underrepresented groups Therefore, our interpretation of the word

in order to affect a cultural change (Brickson, “inclusive” refers to a work atmosphere in

2000). We purport that a more realistic per- which each person is valued for his or her dis-

spective on “managing for diversity” is an tinctive skills, experiences, and

ongoing process that emphasizes relational perspectives. We perceive attitudi-

development that values the individual nal differences between the terms

…the greatest asset

within the collective identity of the organi- “diversity training” and “manag-

zation. As part of the Diversity Research Net- ing for diversity” and are biased employees bring to

work, Kochan and colleagues (2003, p. 18) decidedly toward the latter. We

conclude: see “managing for diversity” as an organization is

being a proactive, ongoing strat-

their unique insights

Therefore, managers might do better to egy that creates a culture within

focus on building an organizational which people appreciate and can and perspectives.

culture, human resource practices, and capitalize on individual differ-

the managerial and group process skills ences—regardless of changing

needed to translate diversity into posi- legal, demographic, and eco-

tive organizational, group, and individ- nomic conditions.

ual results. We suspect that problems emerge when

managers use diversity training to react to

Brickson (2000) points out that a rela- legal dictates, or when they pursue diversity

tional orientation facilitates a social aware- issues solely in response to the environment.

ness that better allows us to address demo- In both cases, managers treat diversity issues

graphic identities without overly focusing on as a problem, external to their purported

them. She argues that we should concentrate mission, which they must deal with in order

our diversity efforts on relationships be- to maintain the legitimacy of the organiza-

tween employees rather than on group dif- tion (McDaniel & Walls, 1997). Instead, we

ferences. To her philosophy, we add the need encourage an approach that treats diversity

to honor individuality so that employees are as a strategic opportunity for the greater

willing to share their unique perspectives good of both individuals and groups within

with the organization. We assert that our an organization, as well as for the bottom

proposed approach does so by creating an line.

awareness of human commonalities—re- Problems may also occur when diversity

gardless of demographic differences—by training efforts concentrate on visual identi-

making salient the diversity within demo- ties (age, gender, race, ethnicity, disability),

graphic groups as well as across them, and by without addressing hidden identities (e.g.,

emphasizing that the greatest asset employ- values, beliefs, cultures, attitudes, desires,

ees bring to an organization is their unique and needs), and cognitive and behavioral

insights and perspectives. styles that people bring to the workforce.

Such approaches may hinder the emergence

of an inclusive environment by overempha-

Our Philosophy

sizing differences rather than commonali-

Our primary concern is the well-being of in- ties, and/or collective identities at the ex-

dividuals, whether they are students in a pense of individual identities.

classroom or employees in the workplace. We designed this approach with the in-

We suspect that as humans, when we do not tent of fostering appreciation for cultural dif-

feel comfortable with our own uniqueness, ferences within our organization—the class-

we will not be eager to share “that which we room. We used individual life stories coupled

are” with the organization. Alternatively, if with food in a semester-long, socially inclu-

Human Resource Management DOI: 10.1002/hrm

09HRM47_2chavez 5/7/08 11:22 AM Page 338

338 HUMAN RESOURCE MANAGEMENT, Summer 2008

sive process. Because the sharing of food is . . . The other set of forces impels him

typically viewed as a simplistic way to create forward toward wholeness to Self and

awareness of other cultures, our emphasis uniqueness of Self. . . . We grow forward

was on the life stories, with food serving when the delights of growth and anxi-

only to tempt participation. The eties of safety are greater than the anx-

individual stories prompted the ieties of growth and the delights of

Stories prompted the explorations of differences. This safety. (Maslow, 1972, pp. 44–45)

approach resulted in an atmos-

explorations of phere of openness and dialogue These quotes define learning from two

within which participants shared perspectives. The former comes from an edu-

differences. This aspects of themselves (the “me”) cational scholar, and the latter originates

approach resulted in that might otherwise have been from insights on human behavior—specifi-

overlooked in the collective iden- cally, motivation. Both philosophies in-

an atmosphere of tity (the “we”) of the organiza- formed the development of our approach.

tion. Using food stories is only Both require an active learning methodol-

openness and one way to engage employees re- ogy.

lationally, without an explicit Active learning is a process by which

dialogue within

focus on diversity per se. It is the learners actively engage in applying, analyz-

which participants sharing of stories that enhances ing, and synthesizing knowledge (W. S.

an understanding and apprecia- Thomas, Prater, Luckner, Rhine, & Rude,

shared aspects of tion for each other’s uniqueness. 1998). Research suggests that the use of ac-

We present other modes of trans- tive learning methods facilitates absorption

themselves (the

ferring this approach to an ongo- and retention of information better than

“me”) that might ing diversity effort in organiza- conventional techniques (McCarthy & An-

tions in the section entitled “An derson, 2000). Pedagogically, they are suc-

otherwise have been Organizational Approach.” cessful because they provide learners the op-

In summary, by focusing on in- portunity to experience concepts in addition

overlooked in the

terpersonal, relational processes, to reading and hearing about them. Motiva-

collective identity we may have the best chance of tionally, learners are better able to internalize

enhancing organizational diversity and infuse the theoretical concepts through

(the “we”) of the efforts. To understand the basis by personalization.

which this approach can succeed, Internalization refers to people’s “taking

organization. we draw upon the education litera- in” a value or regulation (Ryan & Deci,

ture on learning and motivational 2000), while infusion refers to the further

literature on intrinsic motivation. transformation of that regulation into their

own, so that subsequently, it will emanate

from their sense of self. Internalization and

The Case for an Active Learning

infusion require the involvement of values,

Approach attitudes, and/or emotions in the learning

process. In active learning environments, the

Learning is a change in the individual, brain continuously constructs meanings

due to the interaction of that individ- from the situations in which knowledge is

ual, and his environment, which fills a learned and used (Gazzaniga, 1995). This oc-

need and makes him more capable of curs because learners are more likely to focus

dealing adequately with his environ- attention on something they are doing, as

ment. (Burton, 1963, p. 7) the process of doing requires the involvement

of all our senses and the coordination of

Every human being has both sets of movement with thought (Chavez & Poirier,

[competing] forces within him. . . . One 2007).

set clings to safety and defensiveness Another rationale is that employees

out of fear, tending to regress backward. come with different life experiences and

Human Resource Management DOI: 10.1002/hrm

09HRM47_2chavez 5/7/08 11:22 AM Page 339

Beyond Diversity Training: A Social Infusion for Cultural Inclusion 339

therefore will gain different learning from develop a sense of “ownership” in the learn-

the same work experience. Everyone brings ing process.

bias to his or her work, including diversity We combined what science tells us about

trainers, human resource managers, and the intrinsic motivation, the learning process,

authors of this manuscript. While biases are social needs, culture, and human behavior to

not necessarily bad, they must be acknowl- improve on our approach to diversity train-

edged. At best, we can attempt to make our ing. We found that students responded with

biases salient to ourselves and to others by spontaneous interest, an appreciation for ex-

expressing who we are. Doing so provides us ploration, and enjoyment in the discovery

with an understanding of underlying as- process. In the following sections, we share

sumptions and philosophies born of unique our classroom experience followed by a dis-

experiences so that collectively we can better cussion on replicating the process in the

understand each other. Hence, proponents workforce, suggestions for evaluating such

of active learning paradigms (Anderson & an approach, and a discussion ex-

Speck, 1998; Boggs, 2001; Knowles et al., plicating our final thoughts. For

2005; Kolb, 1984) invite trainers to take re- detailed instructor plans, see

sponsibility for providing trainees with ac- Chavez and Poirier (2007). Research across a

tivities that can enhance learning. Trainers

are encouraged to move away from a top- variety of activities

The Classroom Experience

down paradigm and move toward an active indicates that

learning environment. In order to tap into this inherent

A main component of active-learning enjoyment of the learning learners show more

methodologies and intrinsic motivation is process, the instructors relin-

“contextualization.” Contextualization is a quished their tendency to control enjoyment and

process of placing learning topics in context. the classroom by providing stu-

perform better on a

These contexts involve themes or characters dents with choices. Through

of particular interest to learners so that learn- choice, students were able to myriad of learning

ers are more likely to internalize the material bring to the classroom a personal

and become intrinsically motivated to learn. view of life from which others activities when they

Many researchers commend the motiva- could benefit. The students re-

have a choice of

tional and instructional benefits of contextu- portedly took ownership of the

alization (e.g., Lepper & Cordova, 1992; learning process. They became subject matter, even

Parker & Lepper, 1992). They emphasize that excited, autonomous, self-di-

traditional training efforts conducted out- rected learners—eager to share when choices seem

side the work of the organization are less their ideas and insights.

trivial.

likely to be as effective as those that are tied The instructors invited stu-

directly to the organization’s context. dent teams of three to four stu-

“Self-determination” (choice) is another dents to use food to introduce a

key component of active learning and in- story that had meaning to them. The “food

trinsic motivation (Deci & Ryan, 1987). stories” were to follow academic presenta-

Choice enhances intrinsic motivation tions scheduled throughout the semester. It

through acknowledgment of feelings and is important to note that students were in-

through opportunities for self-direction vited—not assigned—to share a part of

(Deci & Ryan, 1985). Research across a vari- themselves through the use of food. All

ety of activities indicates that learners show teams chose to do so. Some teams jointly

more enjoyment and perform better on a presented a story, while other teams pre-

myriad of learning activities when they have sented two or three food stories. By the end

a choice of subject matter, even when of the semester, individuals were asking if

choices seem trivial (Langer, 1975; Zuker- they could present additional food stories.

man, Porac, Lathin, Smith, & Deci, 1978). Student teams had complete autonomy to

Through choice, learners are more likely to use any food to discuss any issue they chose.

Human Resource Management DOI: 10.1002/hrm

09HRM47_2chavez 5/7/08 11:22 AM Page 340

340 HUMAN RESOURCE MANAGEMENT, Summer 2008

The stories did not have to tie into the aca- class, and politics in a calm and appreciative

demic presentation, even though many did. environment. Students appeared to take

Instead, students could use the food stories pride in sharing their differences.

to expose the class to something new, old, These outcomes indicate that we were

interesting, or different. The base of interest able to meet our first two objectives: to cre-

could be ethnic, religious, economic, politi- ate a relational culture of integration while

cal, or social. celebrating the “me” within the “we” and to

The instructor set the example, early in maintain a culture within which members

the semester, by being the first to introduce are intrinsically motivated to take ownership

a food story (see examples of food stories in of the learning experience and to learn from

the “An Organizational Approach” section). each other. This suggests that an apprecia-

The instructor then invited the students to tion for differences, based on a commonality,

follow the model during their team presen- can be an effective training approach. Shar-

tations. From the instructor ex- ing food makes salient our oneness while re-

ample, students learned the size inforcing pleasant experiences with different

and scope of the food sample. people (as indicated by the stories).

By selecting their Thereafter, each student team Through “self-determination” about

presented one time during the se- which foods and stories to share, we were

own areas of mester. Following academic pre- able to sidestep anxieties about stereotypes.

interest, students sentations, each team shared one Participants chose what they shared. Some

or more individual stories and chose to use the food stories to identify with

brought a portion of then invited students to share in particular groups, while others chose to

eating the food. While presenters demonstrate their uniqueness either within

themselves into the passed out the samples and stu- or despite their group identity. By selecting

dents tasted, the instructor initi- their own areas of interest, students brought

presentation.

ated a class discussion tying a portion of themselves into the presenta-

course concepts to the stories tion. Students were able to portray what is

when possible. When not possi- important in their lives based on their own

ble, the instructors brought up general topics life’s conditioning and experiences. In doing

such as intracultural diversity, ethnocentric- so, students moved culturally diverse life ex-

ity, or the role one’s experiences play in sub- periences from an abstract idea into the con-

sequent expectations and decisions. Often, text of personal reality.

the food stories triggered a curiosity—thus The whole endeavor became a true class

providing an opportunity for appreciative project in which a community of learners

inquisitiveness. taught each other. In one class, students—

Through the use of food (a commonal- without provocation—took photographs of

ity), an open atmosphere emerged within presenters, solicited recipes of the foods

which students began to appreciate differ- shared, and recorded the stories. The instruc-

ences. Students enthusiastically tried differ- tor then copied, collated, bound, and distrib-

ent foods, listened with interest to the sto- uted books to each class member as a keep-

ries, and asked many questions during the sake. In another class, students wrote and

discussions. Students willingly contributed submitted the exercise to the Eastern Acad-

their own experiences and ideas—and they emy of Management conference where it

did so with positive reception and genuine won a “best experiential exercise” award.

interest. As the classroom culture changed, Three students attended and presented their

so too did the number of students requesting food stories at the conference. They dis-

to participate. Hence, students did take own- cussed the process, the insights, and some of

ership of the experience. Within an atmos- the emotional realizations that occurred

phere of positive reception, the class was throughout the semester. Such outcomes in-

able to discuss heretofore emotionally dicate that the process had a strong impact

charged subjects such as race, religion, social on student learning, enjoyment, and com-

Human Resource Management DOI: 10.1002/hrm

09HRM47_2chavez 5/7/08 11:22 AM Page 341

Beyond Diversity Training: A Social Infusion for Cultural Inclusion 341

mitment to each other, their teams, and the those written by many students on course

classroom. evaluations:

At the end of each semester, we use the

nominal group brainstorming technique to • “As a senior I finally got to know my fel-

obtain feedback about the course. We ask low students. I wish I had this type of

students to list the activities or concepts that class as a freshman.”

were of the most interest or from which they • “I suspect 25 years from now if you ask

learned the most. We visibly record all sug- the students in this class which course

gestions. We typically begin the voting with they remember most, it will be yours for

30–40 ideas. Students then vote (one for the single reason that there was a lot of

each five to six suggestions) for their favorite interaction both in and out of class be-

idea. We then eliminate the half that receives tween people who would not have other-

the least votes and allow students to vote wise associated with each other—a very

again for the remaining suggestions. Each uncommon teaching prac-

time, we have used this approach to teaching tice.”

diversity, food stories have emerged as the • “Wow, I never knew [that In all cases, we

top activity. Likewise, 70 to 80% of students phrase] could be interpreted

(without provocation from instructors) so many different ways.” were able to create

wrote positive evaluative comments regard- • “You truly have brought a re-

ing the exercise and level of interaction. In- spect for differences to the a culture of

structors received course evaluations near class.”

inclusiveness within

and/or at the top of their respective colleges • “When I started, I was afraid

during the semesters in which they used the because I am different. Now I which individual

food approach. have many friends and I like

We have used this semester-long my difference.” perspectives

approach to diversity appreciation in both • “Thanks for letting us share

contributed to the

undergraduate and MBA courses, in courses ourselves.”

on organizational behavior, strategic man- context of the

agement, human resource management, and

An Organizational course.

cultural diversity at three large public uni-

versities located in the northeast, northwest,

Approach

and the southwest United States. The north- We can apply the same principles

eastern university has a diverse international (developed in the classroom) to a workforce

and a diverse American student body. The setting with the goal of developing an inclu-

southwest university is designated as a “His- sive organizational culture. Such an atmos-

panic-serving” university and has been rated phere provides management a strategic op-

as one of the best universities for minorities portunity to capitalize on the unique

to attend. The northwest university has a perspectives a diverse workforce offers.

more homogeneous student body. Class- Just as the instructors did, organizational

room results were the same across all three facilitators can either dictate or leave up to

universities, indicating that this approach volunteers the choice of whether or not to

truly does address uniqueness both across use teams. One advantage to dyadic or team

and within groups. In all cases, we were able presentations is that it affords an opportu-

to create a culture of inclusiveness within nity to participate to those who might not

which individual perspectives contributed to do so individually. We recommend that sto-

the context of the course. We suspect that ries be structured around something of gen-

the success we have experienced within a 13- eral interest to all participants (e.g., music, a

week semester would be amplified in an on- favorite book, art, or favorite quote). This

going organizational effort. provides volunteers with some structure

As further evidence of success, we report while allowing for choice of what they want

the following testimonials as typical of to share as well as the intensity or shallow-

Human Resource Management DOI: 10.1002/hrm

09HRM47_2chavez 5/7/08 11:22 AM Page 342

342 HUMAN RESOURCE MANAGEMENT, Summer 2008

ness of that which they choose to share. It is chose to share her dreams rather than

our experience that once the leader/instruc- her experiences or her heritage.

tor/manager sets the example, others will • Another ostensibly Anglo, French-named

follow in kind. student contributed Chinese tamales and

It is imperative that top management be related how she learned to prepare them

the first to present a story. Doing so sends while living in China where she met her

the message that management supports the husband. This person chose to share her

procedure and defines the scope of the exer- cultural experiences rather than her her-

cise (e.g., size of the food snack, itage. Our discussion centered on what it

length and intensity of the story). is like to be an American living in a Chi-

Likewise, by demonstrating open nese culture contrasted with what it is

It is imperative that and sharing behaviors, manage- like to be a Chinese living in an Ameri-

ment describes a cultural expecta- can culture.

top management be tion that others are then more • One Native American student caught,

the first to present likely to replicate. cooked, and served up fresh trout. He

Second, management must shared information about his heritage

a story. Doing so allow choice about what people and his tribe’s celebratory customs. An-

want to share. Just as instructors other participant observed that there

sends the message relinquished control of the class- were noticeable differences in celebra-

room, so too must top managers tory schedules between Native Ameri-

that management

learn to relinquish some power can tribes and nations that need to be

supports the in the process. R. R. Thomas respected when scheduling group inter-

(1990) identifies the reluctance actions.

procedure and of top managers to relinquish • One of the instructors brought beer

power as one reason for poor di- (nonalcoholic) and told a story about

defines the scope

versity training results. He points having had cancer that necessitated an

of the exercise out that diversity workshops typ- operation. The night before the opera-

ically have to depend on the tion, her doctor asked if there was any-

(e.g., size of the goodwill of top managers, who thing special she wanted the next day.

themselves may not be commit- She told him she would like a beer. The

food snack, length ted to change. Thus, much train- doctor agreed to prescribe the beer. Fol-

and intensity of the ing occurs top-down, which lowing a successful operation, and just as

places the burden for behavioral soon as she felt well enough to eat, she

story). change on new recruits rather asked for the beer. The nurse left and

than on management. came back with directions to the beer.

Third, managers must be The doctor had fulfilled his promise.

ready for anything. The exercise leads to However, he had arranged for the beer to

some very interesting results. Some exam- be on the other side of the hospital with

ples: instructions that the patient had to get it

herself. Obviously, the doctor wanted his

• One ostensibly Anglo, non-Hispanic-sur- patient to exercise as soon as possible fol-

named student contributed tamales and lowing the operation. At the time, we

related how his Mexican abuela (grand- were studying conflict/negotiation is-

mother) made them each year at Christ- sues. This became an example of a

mas. This person welcomed the opportu- win/win (collaborative) strategy.

nity to introduce his Hispanic heritage. • A student from Mexico brought a cactus

• In contrast, an African American student salad. We learned that Mexicans often

brought escargot in a rich cream sauce. substitute cactus for meat because of the

She introduced her love for cooking expense. We also learned about family

French food and her dreams of becoming eating customs in Mexico. Dinners are

a professional gourmet cook. This person family-oriented and leisurely. At the

Human Resource Management DOI: 10.1002/hrm

09HRM47_2chavez 5/7/08 11:22 AM Page 343

Beyond Diversity Training: A Social Infusion for Cultural Inclusion 343

time, we were doing a case study on Ken- nature of human beings?” “How can we

tucky Fried Chicken (KFC). We tied Mex- apply the lessons learned here to our work

ican culture into the probability of suc- unit, department, or organization?” “What

cess for KFC’s impending expansion into issues introduced in this story can we capi-

Mexico. Based on the presentation cen- talize on in an effort to honor and make

tering on Mexican eating customs, stu- comfortable every member of our work-

dents decided that KFC’s fast-food con- force?” and “What issues introduced in this

cept would fail (which it initially did). story can we capitalize on in our business . .

• A Chinese-born American student told a . or with our products/services?” Participants

story of starvation as a youngster in can be surprisingly insightful.

China. Her family, she relayed, spent Our examples come from the

much time discussing and dreaming classroom so we tied stories to

about the possibility of turning newspa- course content. However, the The skill of the

per into food. Her sister grew up to be- Pringles story is an example of

come a chemist working with the team how early experiences inform facilitator to “tease

that created Pringles Potato Chips later perceptions and how—if em-

printed with edible ink (see your local ployees are willing to share—the out” and adapt the

grocery store shelf). organization can capitalize on stories to key

• Another student brought what he per- those experiences. Would KFC

ceived to be “good old American have approached its expansion issues within the

coleslaw.” He told of being extremely into Mexico differently if the cac-

poor relative to other kids in his high tus presentation had occurred in organization is

school. Consequently, he was embar- their organization? Might the in-

important. In this

rassed to join his friends for hamburgers. structor’s “beer” story serve as a

Still, the social desire to be included was prompt to fitness or health organ- vein, facilitators

strong. Therefore, the young man pre- izations, or organizations that

tended to be a vegetarian. He noticed stress wellness or preventative must be open-

that very few people ate the coleslaw care? The realization that the tim-

minded, allowing

often served with the food orders. It be- ing of religious and other celebra-

came his practice to eat the leftover tions differs among different discussion topics to

coleslaw. The positive outcome, he said, groups might lead an organiza-

is that “I absolutely love coleslaw and I tion to change from a traditional emerge from the

make the best coleslaw of anyone. I am Christian-based holiday schedule

questions,

sharing my best recipe with you today. If toward a more flexible schedule

you do not like it, please set it aside; I will (say everyone gets to take seven comments, and

be around to collect the leftovers.” (For holidays per year scheduled ac-

an elaboration on these and other stories, cording to individual and organi- enhancements that

see Chavez & Poirier, 2007.) zational needs). This would better

serve the needs of employees members present.

The skill of the facilitator to “tease out” while sending a clear message

and adapt the stories to key issues within the that everyone is valued. Likewise,

organization is important. In this vein, facil- by knowing the needs of individuals, man-

itators must be open-minded, allowing dis- agers could more efficiently schedule the

cussion topics to emerge from the questions, work of the organization.

comments, and enhancements that mem- The “Slaw Boy” story occurred in a mas-

bers present. Only then can we be confident ter-level course on understanding human be-

that we are addressing the issues relevant to havior in organizations. Therefore, discus-

the environment within which we are oper- sions of motivation theories (McClelland’s

ating. Trainers can ask leading questions n/affiliation, Maslow’s social, and Alderfer’s

such as “What issues can we identify for fur- relatedness needs, etc.) as well as the concept

ther discussion towards understanding the of social desirability were appropriate topics.

Human Resource Management DOI: 10.1002/hrm

09HRM47_2chavez 5/7/08 11:22 AM Page 344

344 HUMAN RESOURCE MANAGEMENT, Summer 2008

Had this story emerged in a work setting, volunteers must choose what they want to

then perhaps topics such as ethics or fa- share. Not all participants will volunteer,

voritism (in-group vs. out-group dynamics) while others will seek multiple opportunities

would have emerged. The suggested topics to share. However, most members look for-

for exploration are included to show the ward to the presentations and learning

magnitude of this exercise—how one might something about others. Once sharing activ-

apply it to various situations. ities become an expectation or cultural

Numerous stories exist about business norm, volunteerism tends to increase. In the

failures due to cultural misunderstandings classroom, volunteerism was sluggish at the

(CultComm, 2004) that might have been beginning of the semester, whereas we could

avoided had the organizations had a diverse not accommodate all the volunteers in the

workforce that they listened to before at- second half. Some individuals have personal

tempting to enter new markets. For example, reasons for not sharing (e.g., fear or shyness),

McDonald’s developed advertise- while others share only surface differences,

ments directed at Hispanics. They opting instead to avoid sensitive issues. We

did not distinguish within the value the individuals’ right to choose their

Numerous stories Hispanic population until they level (if any) and depth of sharing, as this is

received complaints from Puerto an element of their uniqueness.

exist about business Rico that the “ads were too Mexi- An alternative approach is to ask partici-

failures due to can.” Likewise, Gerber marketed pants to bring a symbol that represents a

its famous baby food in Africa defining moment in their lives. Ask them to

cultural with the picture of the Gerber share how that event changed who they are

baby on the label. It is no wonder or informed who they became. The Pringles

misunderstandings. Gerber failed, as in Africa labels story is one example. Management can first

are used to present a picture of split participants into groups to share stories

the food inside the container. among themselves, and/or have them select a

Ford introduced its Pinto in Brazil under the group story to share externally. To encourage

name of Corcel. Following a failed, albeit ex- sharing, award a “silly but fun” prize for the

pensive, marketing campaign Ford belatedly most interesting story or most creative adap-

learned that the word “corcel” was Por- tation of a story into the work of the organi-

tuguese slang for “a small male appendage.” zation. We believe that people inherently

Not all stories are going to be relevant to enjoy sharing their experiences, thoughts,

the organization’s strategy. However, all pre- and perceptions. However, they will only do

sentations are relevant to those presenting so when they feel valued as they are.

and allow people to get to know one an- A technology research unit in the Idaho

other. Thomas Edison required his workers State Government has employees play “King

to submit ideas on a regular basis. He set a for the Day.” They hold monthly meetings

personal quota of one minor invention idea designated solely to brainstorming ideas

every ten days and a major invention idea that the “King for the Day” brings. The

every six months. While the majority of “King” is encouraged to be creative and even

these ideas did not come to fruition, those silly. Meeting participants are also encour-

that did made a very big difference (Dubrin, aged to be creative and silly in further de-

1998). veloping the ideas. The technology director

With these caveats in mind, one ap- often acts as a court jester in order to keep

proach is to set aside time for this process on ideas flowing. Several ideas have led to

a regular basis. The time could be at the be- change. One such idea led to a sharing of

ginning of a meeting, during lunch, or dur- common resources (answering services, on-

ing afternoon or morning breaks. Following call technical expertise, etc.) among several

a managerial demonstration, invite employ- information technology units within the

ees to schedule and share a story at future state government (D. Fournier, personal

meetings. Sharing must be voluntary and communication, 2007).

Human Resource Management DOI: 10.1002/hrm

09HRM47_2chavez 5/7/08 11:22 AM Page 345

Beyond Diversity Training: A Social Infusion for Cultural Inclusion 345

Additionally, we can ask that participants each organization. Thus, evaluating diversity

research the origination of the foods they training effectiveness should reflect a process

choose. By discovering the history of foods, that integrates training needs, objectives,

we may discover some interesting connec- and outcomes with key strategic objectives

tions to the rest of the people of the world and goals, and examines training within the

and to each other. However, stories do not context of the organization’s culture. One

need to be embedded within an eating activ- problem with nonintegrative approaches is

ity. Having participants design a story around the failure to assess diversity interventions

a favorite poem, quote, book, or movie can within this context. Other problems stem

be just as effective. Likewise, the history of from the type of evaluation.

these modes can also reveal interesting con- Typically, trainers evaluate participants’

nections among seemingly disparate groups reactions to the training and/or what partici-

of people. Management can use a combina- pants say they learned from the training con-

tion of activities in conjunction with each tent. We re-emphasize the impor-

other or subsequent to each other. For exam- tance of evaluating either at the

ple, this year we share food stories, next year behavioral level or at the organiza-

we share music stories, and so on. The key to tional level—assessing whether Our inclusion

sharing is in the stories. To that end, have the culture has become more in-

participants select stories based on a personal clusive as a result of the interven- approach rests

meaning or fond association that is unique to tion. The evaluation approaches upon the premise

themselves. In the next section, we present discussed below are general and

several avenues for evaluating the success of varied. They may be used in isola- that management

such an approach in organizations. tion or together and can be

adapted or modified to suit the desires a holistic

particular purposes of each organ-

Evaluating Training Effectiveness change, one that

ization that adopts our inclusion

Our inclusion approach rests upon the prem- approach. advances a change

ise that management desires a holistic

change, one that advances a change in orga- • Wardley (2006) suggests using in organizational

nizational culture. Necessary attitudes a combination of qualitative

culture.

within an inclusive environment include a and quantitative data when

belief in the business case for diversity, a using culture as a catalyst for

desire to develop sensitivity and awareness change. Qualitative assess-

about diversity, and a willingness to engage ments include interviews and focus

in behavioral change. Such characteristics groups. Wardley then proposes using root-

“facilitate a transformation in thinking” cause analysis to sort through this qualita-

(Guillory & Guillory, 2004, p. 25). Strategies tive data to get at the two or three key

for successful transformation include provid- areas (root causes) that will have the great-

ing members with an organizational impera- est impact on organizational performance.

tive for change, building on the successes of • Glaser (2005) advises managers to ask

those who are committed to change, and seven questions to assess culture and as a

coaching for leadership skills to support the way to guide organizational transition.

change process (Miller, 1998). We can meas- We have adapted those questions to as-

ure the existence of such attitudes and the sess the presence of an inclusive culture.

degree to which such strategies exist. We ex- The questionnaire can be administered

pect a positive association between the both before and after any training and/or

processes and attitudes needed to create an intervention, or across a time span. Addi-

inclusive culture and the successful transfor- tionally, we have added two questions

mation to an inclusive culture. The degree of (“b” questions). We recommend using a

inclusiveness will be unique to the context, Likert scale where 1 = not at all and 7 =

goals, work, and diversity of members within to a great extent.

Human Resource Management DOI: 10.1002/hrm

09HRM47_2chavez 5/7/08 11:22 AM Page 346

346 HUMAN RESOURCE MANAGEMENT, Summer 2008

1. Are conversations about diversity orities for change (see Carr, 2004, for an

healthy? example of how one company used this

1b. Does everyone participate in diversity survey tool). This tool identifies cultural

discussions? norms that make the difference between

2. Is there a spirit of appreciation, or a pos- profitable and unprofitable companies:

itive spirit, regarding diversity? adaptability, mission, consistency, and

2b. Do you enjoy sharing and hearing involvement.

about diversity issues? • See Taras (2007) for a catalogue of 140 in-

3. Are leaders providing direction with struments measuring cultures. Many

respect to honoring diverse perspectives? measure organizational culture and con-

4. Are diverse employees collaborating and tain original items, scoring keys, and in-

bonding across boundaries? formation about reliabilities.

5. In what ways are diverse colleagues en-

gaging each other for mutual success? Within the context of evaluating our in-

6. Is there a feeling that we are all in this to- clusion approach, management can adopt a

gether? “pre-post” evaluation design whereby the

7. Is there a spirit of discovery and inquiry culture is assessed before the start of the in-

in the enterprise that includes diverse tervention, then again at later predeter-

employees? mined time periods. Since we view our

• In addition to these qualitative assess- approach as a longer-term endeavor,

ments, the Organizational Cul- postassessment(s) might not take place for a

ture Inventory, or OCI (Human period of years or periodically across several

Synergistics International, 2005) years. Additionally, organizations can meas-

We also remind the

can serve as a useful quantitative ure specific key organizational outcomes

reader that there is a diagnostic tool. It measures vari- such as turnover, retention rates, or absen-

ous behavioral norms termed teeism among various identity groups (in-

difference between “cultural styles” that identify cluding underrepresented groups) to evalu-

shared beliefs, values, and expec- ate the impact of the inclusion process on

visual and hidden tations that guide interactions both groups and individuals.

identities and that by among organizational members.

The OCI identifies three cultural

Final Thoughts

failing to address styles: constructive, aggressive/

defensive, and passive/defensive. Our experiences indicate that we were able

deep-seated The survey instrument is adapted to meet our objectives: to create a relational

from Kotter and Heskett’s (1992) culture of integration while celebrating the

differences, we may

study wherein they identified “me” within the “we”; to maintain a culture

be relegating those effective organizational cultures within which members are intrinsically mo-

as “adaptive” and ineffective cul- tivated to take ownership of the learning ex-

differences to the tures as “unadaptive.” The OCI’s perience and thus learn from each other; and

“constructive” cultural style is to incorporate a strategy into our classroom

realm of something

consistent with Kotter and Hes- organizations that capitalizes on the multi-

“unspeakable” that kett’s adaptive culture and is ple perspectives of individuals. We initially

characterized as being, among were surprised at the richness of the stories.

carries a negative other things, proactive and trust- However, after experiencing the results de-

ing, having leadership that pro- scribed across numerous training efforts, we

connotation.

duces change, and members who are confident that we would obtain similar

believe they can effectively man- results in other social environments.

age any problem. In our experience, there is enough diver-

• Another tool is the Denison Organiza- sity across and within most groups to afford

tional Culture Survey (Denison & Neale, very interesting discussions, realizations, and

1996), which helps organizations set pri- sensitivities about differences in values, atti-

Human Resource Management DOI: 10.1002/hrm

09HRM47_2chavez 5/7/08 11:22 AM Page 347

Beyond Diversity Training: A Social Infusion for Cultural Inclusion 347

tudes, and perspectives. We also remind the tudes that can lead to cultural change. We

reader that there is a difference between vi- encourage HR managers to focus more effort

sual and hidden identities and that by failing on the continuous support of relationships

to address deep-seated differences, we may among employees with an occasional lesson

be relegating those differences to the realm in more sensitive issues (e.g., training neces-

of something “unspeakable” that carries a sitated by circumstances such as sexual ha-

negative connotation. Through empower- rassment or other legally mandated train-

ment, the approach presented here “gets at” ing). Our contention is that negative

the differences that participants deem im- emotional reactions (defensiveness, blame,

portant. Participants decide what is worth shame, etc.) will be subdued within a culture

sharing rather than being victims of social that first stresses supportive relationships.

norms and negative expectations. Therefore, we encourage human resource

For example, through choice, a variety of managers to seriously consider this

concerns may emerge for discussion that approach (epicurean or other-

management might otherwise overlook. By wise) to an inclusive culture of

allowing employees to direct topics through diverse employees.

their stories, we are reasonably confident that Like T. Cox and Blake (1991), We assert that

discussion topics will be uniquely suited to we view an attitude of valuing

the needs and interests of each particular or- diversity as a strategic means to “managing for

ganization and the needs of each employee. enhancing organizational effec- diversity” can be a

The lessons learned occur within the particu- tiveness. We assert that “manag-

lar organizational context or situation as rec- ing for diversity” can be a com- competitive

ommended by Kochan et al. (2003) and Jayne petitive advantage through the

and Dipboye (2004). Trainers avoid focusing attraction, retention, and leverag- advantage through

on the interests of a few diverse groups at the ing of the unique capacities of a

the attraction,

expense of others. Rather, the training is so- diverse workforce. Rather than

cially inclusive and circumvents this concern. using a discrimination-and-fair- retention, and

Another potential benefit of this approach ness paradigm based on assimila-

is that it encourages open communications tion, or an access-and-legitimacy leveraging of the

and interactive listening—a practice that model predicated on differentia-

unique capacities of

should reduce any negative effects of diversity tion, we advocate a learning-and-

on group processes as purported by Kochan et effectiveness approach centered a diverse workforce.

al. (2003). Instead, we speculate that these el- on integration as described by D.

ements will enhance relational developments, A. Thomas and Ely (1996). This is

which, in turn, should result in greater em- a win-win approach with many

ployee identification with their work units possible benefits to both individual members

and the organizational culture. When mem- and the organization. Within such an atmos-

bers of a group have a relational orientation, phere, people interact and share something

social cognitions can address such differences of themselves. Most importantly, they be-

(e.g., demographic identities) without becom- come positively disposed to listen to one an-

ing the focus, as there is a balance between other. To this end, we must create a safe and

personal and social identities in such cultures open culture within which employees can

(Kreiner, Hollensbe, & Sheep, 2006). Thus, we discover and appreciate differences: a culture

avoid the “blame and shame” approach, and within which workers can take ownership of

people are less likely to become defensive. the learning process, can teach each other,

Kochan et al. (2003) recommended the and can feel “comfortable” in their own

need for a long-term approach that empha- skin—a culture to which people want to be-

sizes group processes and relational develop- long. In short, we strongly advocate a

ment as a means to leveraging diversity in change in attitude that moves away from a

organizations. We assert that our method focus on “managing diversity” toward an at-

does promote changes in institutional atti- titude of “managing for diversity.”

Human Resource Management DOI: 10.1002/hrm

09HRM47_2chavez 5/7/08 11:22 AM Page 348

348 HUMAN RESOURCE MANAGEMENT, Summer 2008

CAROLYN I. CHAVEZ is an assistant professor in the College of Business at New Mexico

State University. She received her PhD from the State University of New York at Albany

(SUNY). Her research interests include power and influence, leadership development,

management education, and training. Her publications include articles in the Journal of

Applied Psychology, the Journal of Organizational Behavior, Leadership Quarterly, and

the Journal of Management Education.

JUDITH Y. WEISINGER is an associate professor in the College of Business at New

Mexico State University. She received her PhD from Case Western Reserve University.

Her research interests include cross-cultural management and diversity. Her publica-

tions include articles in the Journal of Managerial Issues, the Irish Journal of Manage-

ment, and the Journal of Management Inquiry.

REFERENCES Chavez, C. I., & Poirier, V. P. (2007). Stimulating cul-

tural appetites: A gourmet approach. Journal of

Anderson, R. S., & Speck, B. W. (1998). “Oh what a dif- Management Education, 31, 505–520.

ference a team makes:” Why team teaching makes

Christensen, S. L., & Nemetz, P. L. (1996). The chal-

a difference. Teaching and Teacher Education, 14,

lenge of cultural diversity: Harnessing a diversity

671–686.

of views to understand multiculturalism. Academy

Bacharach, S. B., Bamberger, P. A., & Vashdi, D. (2005). of Management Review, 21, 434–462.

Diversity and homophily at work: Supportive rela-

Cox, P. L. (2001). Teaching business students about di-

tions among white and African-American peers.

versity: An experiential, multimedia approach.

Academy of Management Journal, 48, 619–644.

Journal of Behavioral and Applied Management, 2,

Beaver, W. (1995). Let’s stop diversity training and 169–185.

start managing for diversity. Industrial Manage-

Cox, T. (1993). Cultural diversity in organizations: The-

ment, 37, 7.

ory, research, and practice. San Francisco, CA:

Bendick, M., Jr., Egan, M., & Lofhjelm, S. (1998). Work- Berrett-Koehler

force diversity training: From anti-discrimination

Cox, T. (1994). Cultural diversity in organization: The-

compliance to organizational development. Wash-

ory, research, and practice. San Francisco, CA:

ington, DC: Human Resource Planning, U.S. Gen-

Berrett-Koehler.

eral Accounting Office.

Cox, T., & Blake, S. (1991). Managing cultural diversity:

Boggs, G. R. (2001). The meaning of scholarship in

implications for effectiveness. Academy of Man-

community colleges. Community College Journal,

agement Executive, 5, 45–56.

72, 23–26.

CultComm. (2004). Cultural misunderstandings. Re-

Brickson, S. (2000). The impact of identity orientation

trieved August 2, 2004, from http://www.css.edu/

on individual and organizational outcomes in de-

users/dswenson/web/335ARTIC/CULTCOMM.HTM

mographically diverse settings. Academy of Man-

agement Review, 25, 82–101. Deci, E. L., & Ryan, R. M. (1985). Intrinsic Motivation

and self-determination in human behavior. New

Brown, Q. (1998, October 19). Diversity training chal-

York: Plenum.

lenges assumptions. The Gazette (Colorado

Springs), p. 4. Deci, E. L., & Ryan, R. M. (1987). The support of

autonomy and the control of behavior. Journal

Bureau of Labor Statistics. (2004). Tomorrow’s jobs.

of Personality and Social Psychology, 53,

Retrieved June 6, 2007, from http//www.bls.gov/

1024–1037.

oco/oco2003.htm