Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Reconstruction of Late-Onset Transplant Ureteral Stricture Disease

Reconstruction of Late-Onset Transplant Ureteral Stricture Disease

Uploaded by

tnsourceOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Reconstruction of Late-Onset Transplant Ureteral Stricture Disease

Reconstruction of Late-Onset Transplant Ureteral Stricture Disease

Uploaded by

tnsourceCopyright:

Available Formats

2010 THE AUTHORS.

JOURNAL COMPILATION 2010 BJU INTERNATIONAL

Laparoscopic and Robotic Urology

LATE-ONSET TRANSPLANT URETERAL STRICTURE DISEASE

HELFAND

ET AL.

Reconstruction of late-onset transplant ureteral

BJUI BJU INTERNATIONAL

stricture disease

Brian T. Helfand, Jessica P. Newman, Anne K. Mongiu, Parth Modi,

Joshua J. Meeks and Christopher M. Gonzalez

Department of Urology, Feinberg School of Medicine, Northwestern University, Chicago, IL, USA

Accepted for publication 1 April 2010

Study Type – Therapy (case series) What’s known on the subject? and What does the study add?

Level of Evidence 4 Most of the published literature reporting on ureteral obstruction after renal

transplantation details the outcomes of management when performed within a few

months post-transplantation. The present study attempts to document the management

OBJECTIVE

and outcomes of patients who develop delayed ureteral strictures after renal transplant.

• To describe our experience with surgical

management of transplant ureteral unobstructed outflow not requiring repeat and has remained recurrence-free for 16

strictures over a 6-year period. dilation, ureterotomy or stent placement. months.

PATIENTS AND METHODS RESULTS CONCLUSIONS

• The present study identified patients who • Median age at the time of reconstruction • Patients who present >6 months after

underwent open reconstruction for was 51 years and the mean time from renal transplantation with ureteral strictures

transplant ureteral strictures between March transplantation was 62 months. that are recalcitrant to endoscopic

2002 and May 2008 after kidney or kidney– • Seven of the 13 patients had failed management can safely undergo open

pancreas transplantation. previous balloon dilation. surgical ureteral reconstruction without

• Baseline clinical characteristics were • The patients were followed for a median subsequent renal or graft failure.

documented, including age at of 41 months and a successful repair was • Further investigation involving a larger

transplantation and reconstruction, serum achieved in 10 of 13 patients. patient cohort is required to confirm these

creatinine levels, immunosuppressive drug • Ureteral strictures recurred in two patients initial results.

regimen, and comorbidities. who received ureteroneocystostomies, which

• Postoperative complications were noted, were subsequently managed with chronic KEYWORDS

including urinary tract infections, stricture stent exchanges.

recurrence and graft failure. • Another recurrence involved a 1.5-cm kidney transplant, transplant ureteral

• Successful reconstructions were defined anastomotic stricture 6 months stricture, pyelovesicostomy,

as stable allograft function with postoperatively, which was balloon-dilated ureteroneocystostomy, outcomes

INTRODUCTION ureteral strictures as the cause of obstruction including ureteral stricture disease and

may be initially treated by endoscopic or physical obstruction from lymphoceles,

Urological complications are a significant percutaneous management, including JJ stent kinked or redundant ureters, and extrinsic

cause of morbidity after renal transplantation. insertion or percutaneous balloon dilatation. compression from crossing blood vessels.

In particular, ureteral strictures are one of the However, although these techniques are In addition, most studies only report on the

most common complications in transplant minimally invasive, they are often limited by outcomes of patients at follow-up, 1–2 years

patients, with an incidence in the range 0.6– their success rates, which are in the range after their ureteral reconstruction [9,11].

10.5% [1–3], and appear to be independent of 45–62% [5,6]. When these endoscopic options

whether patients undergo living or cadaveric fail or are not feasible, more definitive surgical Most of the published literature reporting

donor transplantations [4]. corrections are required to prevent on ureteral obstruction after renal

subsequent renal failure and/or allograft loss. transplantation details the outcomes of

Patients who present with acute renal failure management when performed within a few

or deteriorating graft function not related to Several studies have reported the efficacy of months post-transplantation. The aetiology

immunosuppressive therapy often undergo surgical repair of obstructed transplant of early stricture disease is caused by poor

an ultrasound of the transplant kidney and/or ureters [7–10]. These reports encompass a surgical technique or compromised ureteral

renogram to evaluate for mechanical relatively small number of patients with blood supply during surgery. By contrast, the

obstruction. Those patients found to have various causes of ureteral obstruction, aetiology of late stricture disease is relatively

© 2010 THE AUTHORS

982 BJU INTERNATIONAL © 2 0 1 0 B J U I N T E R N A T I O N A L | 1 0 7 , 9 8 2 – 9 8 7 | doi:10.1111/j.1464-410X.2010.09559.x

LATE-ONSET TRANSPLANT URETERAL STRICTURE DISEASE

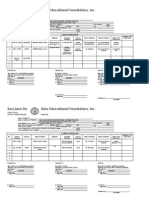

TABLE 1 Patient demographics

Age at

Patient surgery Year of

number (years) Transplant type transplant PMH Immunosuppression

1 55 Kidney, cadaveric 1987 HTN Azathioprine, cyclosporine, prednisone

2 53 Kidney, living, related 2003 HTN, PD × 5 years MMF, tacrolimus

3 51 Kidney, living, related 2002 DM and HTN, HD × 7 months Sirolimus, tacrolimus

4 57 Kidney, cadaveric 2004 PSC, secondary hepatorenal syndrome MMF, tacrolimus

5 60 Kidney, living, unrelated 2004 DM MMF, tacrolimus

6 18 Kidney, living, related 2004 ESRD, secondary to congenital hepatic fibrosis Prednisone, tacrolimus

7 50 SPK, cadaveric 1997 DM MMF, prednisone, tacrolimus

8 51 Kidney, living, unrelated 2005 IDDM, HTN Sirolimus, tacrolimus

9 59 Kidney, cadaveric 1981 Reflux nephropathy w/ chronic pyelonephritis, HTN Azathioprine, prednisone

10 44 Kidney, cadaveric 1997 PCKD Prednisone, tacrolimus

11 41 Kidney, living, unrelated 2006 Pan-urethral stricture MMF, cyclosporine

12 51 Kidney, cadaveric 2004 DM, HTN MMF, tacrolimus

13 23 Kidney, living, related 2006 Potter’s disease MMF, prednisone, tacrolimus

DM, diabetes mellitus; ESRD, end-stage renal disease; HTN, hypertension; IDDM, insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus; MMF, mycophenolate mofetil; PCKD,

polycystic kidney disease; PD, Potter’s disease; PSC, primary sclerosing cholangitis.

unknown and considered to be caused by All of the patients in the cohort were referred After surgical repair, a JJ ureteral stent was

infection, fibrosis or progressive vascular from the transplant service with higher serum placed in all patients. A Jackson–Pratt drain

disease [5,8,11–13]. The various aetiologies of creatinine levels and decreased urine output was placed around the anastamotic site to

stricture disease may affect the long-term (<100 mL/day), with hydronephrosis monitor for the presence of urine leaks. In

outcome of surgical repair in that late confirmed by renal ultrasound at various time addition, all patients had an indwelling Foley

strictures may not be as conducive to repair points after renal transplant. In some cases, catheter both during and after the procedure.

as a result of the potential chronic nature of obstruction was confirmed by renogram. A cystogram was performed before

the disease. Currently, the data on the long- Antegrade pyelography was used to diagnose decatheterization to evaluate for

term outcomes of surgical repair of transplant and determine the location of the stenosis. All extravasation of urine. Patients were screened

strictures presenting late (>6 months) after of the patients were treated initially with postoperatively for recurrence using patient

transplantation are incomplete. Therefore, percutaneous nephrostomy tube placement history and physical examination, assessment

the present study aimed to determine the and JJ stent placement. This does not apply of subjective voiding symptoms, serum

outcomes of patients who underwent for patients early in this series because creatinine levels, urine output, urine culture,

surgical reconstruction of late-presenting balloon dilation was not widely used at our and renal ultrasound and endoscopy with

transplant ureteral strictures over a 6-year institution until 2004. The choice to use either antegrade or retrograde pyelogram

period. balloon dilation as a management strategy when indicated. For the purposes of the

was guided by the location and length of the present study, successful reconstructions

PATIENTS AND METHODS stricture. Pan ureteral strictures were never were defined as stable allograft function with

managed in this regard. unobstructed outflow not requiring repeat

The Northwestern Hospital Enterprise Data dilation, ureterotomy or indwelling stent

Warehouse was used to retrospectively The choice of surgical reconstruction was placement.

identify patients who underwent open determined by the surgeon based upon

reconstruction for late-onset transplant ureteral stricture length, allograft ureter RESULTS

ureteral strictures after kidney or kidney– length, the degree of peri-ureteral fibrosis and

pancreas transplant, as performed by a single personal preference. In brief, all patients BASELINE CHARACTERISTICS

surgeon (C.M.G.) from March 2002 to May underwent general endotracheal anaesthesia

2008. Institutional review board approval was and received prophylactic i.v. broad-spectrum Thirteen patients (10 men and three women)

obtained to perform the study. antibiotics. A modified Gibson incision was who ultimately underwent surgical repair for

used for all but one case where a midline post-transplantation ureteral stricture by

The baseline clinical characteristics of the incision was performed. Ureteral one surgeon (C.M.G.) were included in the

study population were documented, including reconstruction was in the form of excision present study. The median (range) age at

age at renal transplantation, as well as age at and ureteroneocystostomy, excision and transplantation was 41.9 (17.0–59.7) years. Of

ureteral reconstruction. In addition, serum ipsilateral ureteroureterostomy (UU), excision these patients, six underwent cadaveric

creatinine levels, immunosuppressive drug and direct pyelovesicostomy, and/or ureteral transplantations and seven had living donor

regimen and comorbidities were documented. reconstruction using a modified Boari flap. grafts (Table 1). Reasons for renal failure

© 2010 THE AUTHORS

BJU INTERNATIONAL © 2010 BJU INTERNATIONAL 983

H E L F A N D ET AL.

TABLE 2 Patient outcomes after open reconstruction of transplant ureteral strictures

Stricture Time from transplant Follow-up

Patient length Stricture to reconstruction Postoperative length

number (cm) location (months) Procedure Outcome UTI (months)

1 3 Distal 176.1 Transplant ureteral re-implant Success, no further stricture disease No 16.3

2 1.5 Distal, 8.3 Transplant pyelovesicostomy Success, no further stricture disease No 68.3

Ureterovesical

junction

3 3 Distal 20.6 Ureteroureterostomy Success, no further stricture disease No 67.0

4 Length of Length of ureter 5.1 Transplant pyelovesicostomy Recurrent stricture, managed with No 63.7

ureter chronic stent exchange

5* 2.5 Distal 8.9 Transplant ureteral re-implant Success, no further stricture disease No 59.8

6* 1 Distal, 11.4 Transplant pyelovesicostomy Success, no further stricture disease No 55.2

Ureterovesical

junction

7* 4 Distal 91 Transplant ureteral re-implant Success, no further stricture disease Yes 6.8

8 2 Proximal 8.5 Boari flap of bladder to Recurrent stricture 6 months No 44.0

transplanted ureter postoperatively, balloon dilated

successfully

9* 1.3 Distal 309.7 Transplant ureteral re-implant Recurrent stricture, managed with Yes 35.4

chronic stent exchange

10* 3 Distal 118.5 Transplant pyelovesicostomy Success, no further stricture disease No 34.5

11 Length of Length of ureter 6.1 Transplant pyelovesicostomy Success, no further stricture disease No 34.0

ureter

12* 6 Distal 27.1 Transplant ureteral re-implant Success, no further stricture disease No 32.0

13* 2 Distal 26 Transplant ureteral re-implant Success, no further stricture disease No 16.7

*Patients who failed initial management with balloon dilation.

requiring renal transplantation included acute renal failure and decreased urine output adequate ureteral length, five were

hypertension in three patients, diabetes (<100 mL/day), with hydronephrosis reconstructed using direct pyelovesicostomy

mellitus in two patients, both diabetes confirmed by renal ultrasound. All strictures and one underwent ureteral reconstruction

mellitus and hypertension in three patients, were initially managed with percutaneous using a modified Boari flap. The mean (range)

hepatorenal syndrome secondary to primary nephrostomy tube placement, with estimated blood loss from the procedure was

sclerosing cholangitis in one patient, end- subsequent placement and internalization of 354 (0–1400) mL, with two patients requiring

stage renal disease secondary to congenital a stent. Antegrade pyelography was used to intra-operative blood transfusions. There was

hepatic fibrosis in one patient, polycystic diagnose and determine the location of the no obvious association between estimated

kidney disease in one patient, Potter’s disease stenosis. On the basis of the year of balloon blood loss and the type of reconstruction

in one patient, and ureteral stricture disease dilation availability, seven of the 13 patients performed. All resected ureteral segments

in one patient. Of the kidneys, eight were underwent subsequent management with were sent for pathological analysis and

transplanted in the left iliac fossa, four were endoscopic balloon dilatation(s) of the demonstrated histological evidence of fibrosis

transplanted in the right iliac fossa, and one stricture. For these patients, a mean (range) and chronic inflammation.

was transplanted intra-abdominally as a of 1.42 (1–4) endoscopic balloon dilations

result of the large size of the graft and the were performed before open surgical No patient required blood transfusion

small body habitus of the patient. All reconstruction. postoperatively. A single patient went into

transplant ureteroneocystotomies were clot retention on postoperative day 9, which

performed using a Lich–Gregoir technique. The mean (range) length of the stricture, resolved after irrigation through the Foley

The cohort of patients was maintained on including the two patients with pan-ureteral catheter. One patient had a small bowel

various immunosuppressive regimens strictures, was 3.3 (1.0–7.0) cm. Most patients obstruction after surgery requiring re-

according to transplant surgeon and (n = 10) had a stricture located at the distal exploration of the abdomen and lysis of

nephrologist preference (Table 2). ureter, one patient had a stricture at the adhesions on postoperative day 7. Of the 13

proximal ureter, and two patients had a patients, two developed a postoperative

The median (range) age of patients at the time stricture along the length of the entire ureter. urinary tract infection (one positive for

of ureteral reconstruction was 51.0 (18.0– >100 000 Escherichia coli and the other

60.4) years. The mean (range) time from Of the seven patients with viable positive with Pseudomonas aeruginosa). No

transplantation to diagnosis of the stricture allograft ureters, six underwent patient experienced a wound infection

was 62.8 (5.1–309.6) months. All patients ureteroneocystostomies and one underwent or dehiscence. Time to stent removal

presented post kidney transplantation with ipsilateral UU. Of the six patients without postoperatively was determined both by

© 2010 THE AUTHORS

984 BJU INTERNATIONAL © 2010 BJU INTERNATIONAL

LATE-ONSET TRANSPLANT URETERAL STRICTURE DISEASE

physician preference and patient compliance. One of the largest published series to date seven patients were succesfully treated with

The mean (range) time until stent removal reported the outcomes of 1000 patients after balloon dilatation and stenting. Taken

was 48.2 (29–73) days, excluding the two renal transplantation and identified 36 together, these data suggest that

patients who required chronic stent patients (3.6%) with ureteral obstructions; 20 endourological management may not be

exchanges. The mean (range) time to removal considered to be related to a compromised effective for late-onset ureteral strictures and

of the Jackson–Pratt drain was 4 (2–10) days. vascular supply and 16 related to a physical open repair may be the best choice for first-

The Foley catheter was removed after obstruction other than ureteral stenosis (e.g. line therapy in these patients. Further data are

cystography had confirmed no urine extrinsic compression, kinked ureter) [11]. needed to support this conclusion.

extravasation, with a mean (range) time to These patients presented for corrective

removal of 10.2 (7–16) days. surgery within a median of 4 months after Options for surgical repair depend on several

their initial transplant surgery. By contrast, variables, including the length and location of

Median (range) follow-up after surgery was our cohort of patients had a relatively delayed the stricture, surgeon preference and

41.1 (6.8–68.4) months. All patients initially presentation of ureteral stricture, including degree of fibrosis surrounding the ureter.

improved and had stable renal function one patient with onset of renal failure/ In the present study, transplant UU,

associated with spontaneous adequate urine hydronephrosis over 25 years after renal pyelovesicostomy and reimplantation

output. Successful reconstruction was transplantation. In addition, no patient in our were all performed successfully. In our

achieved in 10 of 13 patients. Ureteral series had an obvious physical/anatomic study population, two of the six

strictures recurred in two patients obstruction as a cause for the ureteral ureteroneocystostomies performed for distal

who had previously undergone stenosis. Therefore, our patient population ureteral disease had stricture recurrence.

ureteroneocystostomies, which were had ureteral obstructions solely from Perhaps alternative surgical techniques such

subsequently managed with chronic stent strictures, whereas previous series reported as pyeloureterostomy should be considered in

exchanges. Interestingly, one of these patients on all causes of obstruction that may have this population with distal stenosis. For

experienced a perioperative urinary tract influenced outcomes [7,10,11]. example, Salomon et al. [9] evaluated 10

infection. The third patient with a stricture patients who presented with distal ureteral

recurrence underwent a Boari flap ureteral Minimally invasive endoscopic or stricture disease a mean of 13 months after

reconstruction and was found to have a 1.5- percutaneous management is often the first renal transplantation. All patients were

cm anastomotic stricture 6 months option for patients with ureteral strictures corrected with pyeloureterostomy with the

postoperatively. The ureteral stricture was after renal transplant surgery. Percutaneous patient’s native ipsilateral collecting system

subsequently balloon-dilated and the patient balloon dilation success rates in patients have and experienced no further ureteral

has remained recurrence-free 16 months been reported as 50% [5,6]. Prognostic factors complications after surgery, with a mean

post-procedure. During the extended follow- for successful dilatation include early follow-up of 2 years. Thus, although ureteral

up, four patients had allograft failure diagnosis after transplant, length of stricture reimplant is a useful option, other alternatives

secondary to acute rejection and were unable and a previous episode of rejection [6]. should be considered.

to be rescued by immunosuppression However, in many patients, acute renal

therapies; three of which were irreversible. failure/oliguria/hydronephrosis representing Pyelovesicostomy is beneficial when

There were no reported cases of BK virus or stricture disease does not present early after the native ureter is not suitable for

cytomegalovirus infection in this population. renal transplantation, and endoscopic reconstruction. This technique has an

Two patients subsequently died of unrelated management is less likely to be a viable increased risk of VUR, with subsequent

causes (myocardial infarction; sepsis option. The findings of the present study infection, decreased renal function and

secondary to neutropenia) over 6 months support this notion because patients in our possible graft failure [16]. However, the five

postoperatively. series presented several months after patients in the present series who underwent

transplantation and had failed endoscopic a pyelovesicostomy all did well without

management of transplant ureteral strictures. evidence of VUR or recurrent infections.

DISCUSSION Ureteral strictures that fail percutaneous Ureteroureterostomy with native ureter is an

or endourological management require attractive option if there is adequate length

Ureteral strictures are a relatively common definitive surgical correction. Open surgery and viable tissue remaining in the native

complication after renal transplantation with has the advantage of using a more proximal ureter. The UU technique has been associated

a reported incidence of 31 per 1000 and healthy ureter for repair [11]. with a decreased risk of VUR and urinary

transplants [14]. Early transplant ureteral fistulas, and also spares the ureter for further

strictures, which are diagnosed within 3 In one study of 56 patients with ureteral repair if recurrent complications arise [17]. In

months of surgery, are commonly the result stenosis after kidney transplant, initial the present series, the patient who underwent

of inadequate surgical technique, treatment with percutaenous nephrostomy UU repair with the native ureter experienced

overdissection of the ureter, compromise of followed by balloon dilatation and stenting no recurrence or complications. However,

the blood supply during surgery or ischaemic resulted in a 45% success rate [6]. Considering it should be noted that the native ureter

fibrosis secondary to poor harvesting patients in the same series who presented was rather atretic in appearance, probably

technique and rejection [5,11]. The aetiology more than 5 months after initial transplant related to a lack of native urine production

of later complications may be related to surgery, the success rate of endourologic from renal failure. In our opinion, the atretic

repeat urinary tract infections, retroperitoneal treatment was only 11% (P = 0.6) [6]. In our appearance should not preclude subsequent

fibrosis or vascular insufficiency [5,8,12,15]. series of late-onset ureteral strictures, none of UU repair.

© 2010 THE AUTHORS

BJU INTERNATIONAL © 2010 BJU INTERNATIONAL 985

H E L F A N D ET AL.

FIG. 1. Proposed alogrithm for the management of transplant ureteral strictures. patients should be performed to confirm the

success of surgical outcomes of delayed

Obstruction in transplant ureteral strictures.

Transplant Kidney

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

Perc. Nephrostomy Tube None declared.

Anterograde Nephrostogram

REFERENCES

Early Stricture Late Stricture 1 Breda A, Bui MH, Liao JC, Gritsch HA,

+/− +/−

Stricture < 3 cm

Schulam PG. Incidence of ureteral

Stricture > 3 cm

strictures after laparoscopic donor

nephrectomy. J Urol 2006; 176: 1065–

Consider Balloon Dilation, Operative Repair 8

Stent Placement, Wait 6 wks 2 Emiroglu R, Karakayall H, Sevmis S,

Akkoc H, Bilgin N, Haberal M. Urologic

complications in 1275 consecutive renal

Remove Stent transplantations. Elsevier Sci 2001; 33:

Radiographic and Lab

2016–7

Follow-up

3 Fuller TF, Deger S, Büchler A et al.

Ureteral complications in the renal

transplant recipient after laparoscopic

Persistent Obstruction No Obstruction living donor nephrectomy. Eur Urol 2006;

50: 535–41

4 Cimic J, Meuleman EJ, Oosterhof GO,

Hoitsma AJ. Urological complications in

Operative Repair Continue to Follow renal transplantation. A comparison

between living-related and cadaveric

grafts. Eur Urol 1997; 31: 433–5

5 Bachar GN, Mor E, Bartal G, Atar E,

The patients included in the present study favourable selection bias for the outcomes Goldberg N, Belenky A. Percutaneous

were prescribed various immunosuppressive reported. balloon dilatation for the treatment of

regimens after transplantation, which could early and late ureteral strictures after

have predisposed them to subsequent On the basis of our institutional experience, renal transplantation: long-term follow-

infection or wound dehiscence [18,19]. we propose an algorithm for the management up. CardioVascular Interventional Radiol

However, no complications of this nature of transplant ureteral strictures (Fig. 1). In 2004; 27: 335–8

were observed; therefore, the results this algorithm, we propose that patients 6 Juaneda B, Alcaraz A, Bujons A et al.

obtained in the present study are similar to who are found to have hydronephrosis of Endourological management is better in

previous reports of urological surgery in the transplant kidney should undergo early-onset ureteral stenosis in kidney

immunosuppressed patients after kidney or percutaneous nephrostomy tube placement. transplantation. Transplant Proc 2005;

kidney–pancreas transplants, which showed a Endourologic management (i.e. balloon 37: 3825–7

similar incidence of postoperative morbidity dilation) should be considered as initial 7 Dinckan A, Tekin A, Turkyilmaz S et al.

between transplant and non-transplant therapy in a subset of patients based upon Early and late urological complications

patients [20]. timing after nephrostomy tube placement (i.e. corrected surgically following renal

<3 months) and ureteral stricture length transplantation. Transplant Int 2007; 20:

The results obtained in the present study <3 cm. Finally, definitive operative repair can 702–7

should be evaluated within the context of the be considered in patients with late-onset 8 Faenza A, Nardo B, Fuga G et al.

study limitations, including its retrospective disease and/or longer strictures. Urological Complications in Kidney

nature and the relatively small patient Transplantation: Ureterocystostomy

population. In addition, it was not possible to In conclusion, the prevalence of successful versus Uretero-Ureterostomy. Elsevier

determine the overall prevalence of ureteral endoscopic management of delayed stricture 2005; 37: 2518–20

stricture disease or patients who underwent a disease is unknown. However, the data 9 Salomon L, Saporta F, Amsellem D et al.

successful endoscopic management within obtained in the present study suggest that Results of pyeloureterostomy after

the transplant population at our institution as open surgical reconstruction is a safe ureterovesical anastomosis complications

a result of patient referral biases and procedure that does not appear to be in renal transplantation. Urology 1999;

incomplete datasets. Finally, median stricture associated with graft failure, rejection or 53: 908–12

length in this series was relatively short at increased morbidities. Future studies 10 van Roijen JH, Kirkels W, Zietse R,

3.3 cm, which may have introduced a involving a larger cohort of transplant Roodnat JI, Weimar W, Ijzermans J.

© 2010 THE AUTHORS

986 BJU INTERNATIONAL © 2010 BJU INTERNATIONAL

LATE-ONSET TRANSPLANT URETERAL STRICTURE DISEASE

Long-term graft survival after urological ureteric stenosis in 1298 renal transplant tacrolimus. Transplantation 2004; 77:

complications of 695 kidney patients. Transplant Int 1994; 7: 253–7 1555–61

transplantations. J Urol 2001; 165: 1884– 15 Karam G, Hetet JF, Maillet F et al. 19 Humar A, Ramcharan T, Denny R,

7 Late ureteral stenosis following renal Gillingham KJ, Payne WD, Matas AJ.

11 Shoskes DA, Hanbury D, Cranston D, transplantation: risk factors and impact Are wound complications after a kidney

Morris PJ. Urological complications in on patient and graft survival. Am J transplant more common with modern

1,000 consecutive renal transplant Transplant 2006; 6: 352–6 immunosuppression? Transplantation

recipients. J Urol 1995; 153: 18–21 16 Del Pizzo JJ, Jacobs SC, Bartlett ST, 2001; 72: 1920–3

12 Akbar SA, Jafri SZH, Amendola MA, Sklar GN. The use of bladder for total 20 Meeks JJ, Gonzalez CM. Urethroplasty

Madrazo BL, Salem R, Bis KG. transplant ureteral reconstruction. J Urol in patients with kidney and pancreas

Complications of renal transplantation 1. 1998; 159: 750–3 transplants. J Urol 2008; 180: 1417–20

RadioGraphics 2005; 25: 1335–56 17 Gurkan A, Yakupoglu YK, Dinckan

13 Maier U, Madersbacher S, Banyai- A et al. Comparing two ureter Correspondence: Chris M. Gonzalez,

Falger S, Susani M, Grunberger T. Late reimplantation techniques in kidney Department of Urology, Feinberg School of

ureteral obstruction after kidney transplant recipients. Transplant Int 2006; Medicine, Northwestern University, 675 North

transplantation. Fibrotic answer to 19: 802–6 Saint Clair Street, Suite 20–150, Chicago, IL

previous rejection? Transpl Int 1997; 10: 18 Dean PG, Lund WJ, Larson TS et al. 60611, USA.

65–8 Wound-healing complications after e-mail: cgonzalez@nmff.org

14 Keller H, Nöldge G, Wilms H, Kirste G. kidney transplantation: a prospective,

Incidence, diagnosis, and treatment of randomized comparison of sirolimus and Abbreviation: UU, ureteroureterostomy

© 2010 THE AUTHORS

BJU INTERNATIONAL © 2010 BJU INTERNATIONAL 987

Copyright of BJU International is the property of Wiley-Blackwell and its content may not be copied or emailed

to multiple sites or posted to a listserv without the copyright holder's express written permission. However,

users may print, download, or email articles for individual use.

You might also like

- Assessment of Eyes and EarsDocument31 pagesAssessment of Eyes and EarsShahmeerNo ratings yet

- Proceedings of The 54th Annual Convention of The American Association of Equine PractitionersDocument4 pagesProceedings of The 54th Annual Convention of The American Association of Equine PractitionersJorge HdezNo ratings yet

- ANC OB and GYN HISTORY Taking SampleDocument43 pagesANC OB and GYN HISTORY Taking SampleGebremichael Reta100% (3)

- Reconstruction of Late-Onset Transplant Ureteral Stricture DiseaseDocument6 pagesReconstruction of Late-Onset Transplant Ureteral Stricture DiseaseAnanda KumarNo ratings yet

- Finally Ileal Ureter Corrected (1) (1) IbjuDocument11 pagesFinally Ileal Ureter Corrected (1) (1) IbjuSheshang KamathNo ratings yet

- Safety and Effectiveness Evaluation of Open Reanastomosis For Obliterative or Recalcitrant Anastomotic Stricture After Radical Retropubic ProstatectomyDocument9 pagesSafety and Effectiveness Evaluation of Open Reanastomosis For Obliterative or Recalcitrant Anastomotic Stricture After Radical Retropubic Prostatectomyjuan jose velascoNo ratings yet

- Use of Locking-Loop Pigtail Nephrostomy Catheters in Dogs and Cats 20 Cases (2004 2009)Document10 pagesUse of Locking-Loop Pigtail Nephrostomy Catheters in Dogs and Cats 20 Cases (2004 2009)Bernardo BertoldiNo ratings yet

- NeurogenicbladdermanagementwithcompleteurethraldistructionDocument11 pagesNeurogenicbladdermanagementwithcompleteurethraldistructionPutri Rizky AmaliaNo ratings yet

- Ureteric ComplicationsDocument7 pagesUreteric ComplicationstnsourceNo ratings yet

- FP & NC Kidney SurgeryDocument48 pagesFP & NC Kidney SurgeryancoursNo ratings yet

- Continuous Ambulatory Peritoneal Dialysis Catheter Placement Is Omentectomy Necessary 2016Document3 pagesContinuous Ambulatory Peritoneal Dialysis Catheter Placement Is Omentectomy Necessary 2016waldemar russellNo ratings yet

- Journal CholeDocument3 pagesJournal CholeMary JoyceNo ratings yet

- Nephrectomy - An OverviewDocument4 pagesNephrectomy - An OverviewNikesh DoshiNo ratings yet

- Revision 2 32838Document12 pagesRevision 2 32838chatarina anugrahNo ratings yet

- Editorial What Is The Best Endoscopic Treatment For Pancreatic PseudocystDocument4 pagesEditorial What Is The Best Endoscopic Treatment For Pancreatic PseudocystLogical MonsterNo ratings yet

- Wind2007 PDFDocument5 pagesWind2007 PDFanatolioNo ratings yet

- 'Mini' Extravesical Reimplant With 'Mini' Tapering For Infants Younger Than 6 Months. 2019. ESTUDIO CLINICODocument5 pages'Mini' Extravesical Reimplant With 'Mini' Tapering For Infants Younger Than 6 Months. 2019. ESTUDIO CLINICOJulio GomezNo ratings yet

- Post Aua ReconstructivaDocument14 pagesPost Aua ReconstructivaIndhira Sierra SanchezNo ratings yet

- Duct Cholecystectomy: Major LaparoscopicDocument10 pagesDuct Cholecystectomy: Major LaparoscopicShahnawaz AhangarNo ratings yet

- Visual Internal Urethrotomy For Adult Male UrethraDocument6 pagesVisual Internal Urethrotomy For Adult Male UrethraGd SuarantaNo ratings yet

- Ma 280 287Document8 pagesMa 280 287IlincaNo ratings yet

- V34n4a05 PDFDocument10 pagesV34n4a05 PDFvictorcborgesNo ratings yet

- Stenting in Pediatric TransplantationDocument27 pagesStenting in Pediatric TransplantationChris FrenchNo ratings yet

- Yu 2013Document4 pagesYu 2013raissametasariNo ratings yet

- Vaginoplasty ComplicationDocument8 pagesVaginoplasty Complicationdr sutardiNo ratings yet

- 1 s2.0 S1879522615003929 MainDocument4 pages1 s2.0 S1879522615003929 MainsagaNo ratings yet

- Manejo de Estenosis Recidivante2016Document8 pagesManejo de Estenosis Recidivante2016Salv L RomoNo ratings yet

- Article 39794Document4 pagesArticle 39794d.amouzou1965No ratings yet

- Comparison of Open and Laproscopic Live Donor NephrectomyDocument7 pagesComparison of Open and Laproscopic Live Donor NephrectomyEhab Omar El HalawanyNo ratings yet

- Surgery Illustrated Surgical AtlasDocument12 pagesSurgery Illustrated Surgical AtlasmohamedomarabdelNo ratings yet

- The Experience of A Tertiary Referral Center With Laparoscopic Pyelolithotomy For Large Renal Stones During 18 YearsDocument8 pagesThe Experience of A Tertiary Referral Center With Laparoscopic Pyelolithotomy For Large Renal Stones During 18 YearsDaniel StrubNo ratings yet

- Pancreatic ®stula After Pancreatic Head ResectionDocument7 pagesPancreatic ®stula After Pancreatic Head ResectionNicolas RuizNo ratings yet

- 1 Bjs 10662Document8 pages1 Bjs 10662Vu Duy KienNo ratings yet

- Gozzi2010 1Document3 pagesGozzi2010 1Anonymous GwP922jlNo ratings yet

- Transurethral Incision of Ureterocele: Does The Time of Presentation Affect The Need For Further Surgical Interventions?Document6 pagesTransurethral Incision of Ureterocele: Does The Time of Presentation Affect The Need For Further Surgical Interventions?ErikNo ratings yet

- Ureteral Stent For Ureteral Stricture: James F. Borin and Elspeth M. McdougallDocument13 pagesUreteral Stent For Ureteral Stricture: James F. Borin and Elspeth M. McdougallOoNo ratings yet

- Manejo Pós-ProstatectomiaDocument8 pagesManejo Pós-Prostatectomiapg230532No ratings yet

- Laparoscopic Simple Prostatectomy With Prostatic Urethra Preservation For Benign Prostatic HyperplasiaDocument5 pagesLaparoscopic Simple Prostatectomy With Prostatic Urethra Preservation For Benign Prostatic Hyperplasiajuan jose velascoNo ratings yet

- Pi Is 2210261215001479Document3 pagesPi Is 2210261215001479hussein_faourNo ratings yet

- Review StrikturDocument13 pagesReview StrikturFryda 'buona' YantiNo ratings yet

- 104854-Article Text-283461-1-10-20140701Document6 pages104854-Article Text-283461-1-10-20140701Joan Marie S. FlorNo ratings yet

- Reoperative Antireflux Surgery For Failed Fundoplication: An Analysis of Outcomes in 275 PatientsDocument8 pagesReoperative Antireflux Surgery For Failed Fundoplication: An Analysis of Outcomes in 275 PatientsDiego Andres VasquezNo ratings yet

- The Effects of Bladder Training On Bladder Functions After Transurethral Resection of ProstateDocument21 pagesThe Effects of Bladder Training On Bladder Functions After Transurethral Resection of Prostatetrisna workNo ratings yet

- Peustow ArticleDocument6 pagesPeustow ArticleAjay GujarNo ratings yet

- Endourological Management of Iatrogenic Ureterovaginal Fistula Following Obstetric and Gynecological Surgeries at Tertiary Referral CenterDocument6 pagesEndourological Management of Iatrogenic Ureterovaginal Fistula Following Obstetric and Gynecological Surgeries at Tertiary Referral CenterArika EffiyanaNo ratings yet

- Surgical Techniques For Pancreas Transplantation: Ugo Boggi, Gabriella Amorese and Piero MarchettiDocument10 pagesSurgical Techniques For Pancreas Transplantation: Ugo Boggi, Gabriella Amorese and Piero MarchettiNatalindah Jokiem Woecandra T. D.No ratings yet

- Jurnal OG 5Document9 pagesJurnal OG 5Wa Ode Meutya ZawawiNo ratings yet

- DereviDocument6 pagesDereviDerevie Hendryan MoulinaNo ratings yet

- Urinary Diversions: A Primer of The Surgical Techniques and Imaging FindingsDocument12 pagesUrinary Diversions: A Primer of The Surgical Techniques and Imaging FindingsMCFNo ratings yet

- MainDocument8 pagesMainAdityaRestuRahayuNo ratings yet

- Rectal Computer 2Document5 pagesRectal Computer 2Su-sake KonichiwaNo ratings yet

- A Modified Supine Position Facilitates Bladder Function in Patient Undergoing Percutaneous Coronary InterventionDocument8 pagesA Modified Supine Position Facilitates Bladder Function in Patient Undergoing Percutaneous Coronary InterventionVelicia MargarethaNo ratings yet

- Risk of Failure in Pediatric Ventriculoperitoneal Shunts Placed After Abdominal SurgeryDocument31 pagesRisk of Failure in Pediatric Ventriculoperitoneal Shunts Placed After Abdominal SurgeryWielda VeramitaNo ratings yet

- Modified Young-Dees-Leadbetter Bladder Neck Reconstruction in Patients With Successful Primary Bladder Closure Elsewhere.2018Document3 pagesModified Young-Dees-Leadbetter Bladder Neck Reconstruction in Patients With Successful Primary Bladder Closure Elsewhere.2018Gunduz AgaNo ratings yet

- Urologic Complications in Renal Transplants: Hannah R. Choate, Laura A. Mihalko, Bevan T. ChoateDocument7 pagesUrologic Complications in Renal Transplants: Hannah R. Choate, Laura A. Mihalko, Bevan T. ChoateNidhin MathewNo ratings yet

- Tau 08 02 141bvDocument8 pagesTau 08 02 141bvNidhin MathewNo ratings yet

- Ureterovaginal FistulasDocument4 pagesUreterovaginal Fistulasalfreleo992No ratings yet

- A Prospective Treatment Protocol For Outpatient Laparoscopic Appendectomy For Acute AppendicitisDocument5 pagesA Prospective Treatment Protocol For Outpatient Laparoscopic Appendectomy For Acute AppendicitisBenjamin PaulinNo ratings yet

- 2007-03 - Intestinal Autotransplantation For Adenocarcinoma of Pancreas Involving The Mesenteric Root - Our Experience and Literature Review PDFDocument3 pages2007-03 - Intestinal Autotransplantation For Adenocarcinoma of Pancreas Involving The Mesenteric Root - Our Experience and Literature Review PDFNawzad SulayvaniNo ratings yet

- International Journal of Nursing Studies: SciencedirectDocument4 pagesInternational Journal of Nursing Studies: Sciencedirectyoga madaniNo ratings yet

- 1 s2.0 S2214751921001584 MainDocument7 pages1 s2.0 S2214751921001584 MainfitriNo ratings yet

- Assessment of Urological Complications Following Obstetric and Gynaecological Surgery-Afive Years ReviewDocument4 pagesAssessment of Urological Complications Following Obstetric and Gynaecological Surgery-Afive Years ReviewAhmad YasinNo ratings yet

- Do Et AlDocument10 pagesDo Et AltnsourceNo ratings yet

- Perineal Rectal TraumaDocument1 pagePerineal Rectal TraumatnsourceNo ratings yet

- Robertson 2017Document10 pagesRobertson 2017tnsourceNo ratings yet

- Yoshimaru Et AlDocument8 pagesYoshimaru Et AltnsourceNo ratings yet

- Colorectal and Vaginal Injuries in Personal Watercraft PassengersDocument4 pagesColorectal and Vaginal Injuries in Personal Watercraft PassengerstnsourceNo ratings yet

- Ureteric ComplicationsDocument7 pagesUreteric ComplicationstnsourceNo ratings yet

- 2020 ASM ProgramDocument2 pages2020 ASM ProgramtnsourceNo ratings yet

- Perineal Hydrostatic TraumaDocument2 pagesPerineal Hydrostatic TraumatnsourceNo ratings yet

- Mi TsuyamaDocument8 pagesMi TsuyamatnsourceNo ratings yet

- Presacral Neuroendocrine Carcinoma Developed in A Tailgut CystDocument3 pagesPresacral Neuroendocrine Carcinoma Developed in A Tailgut CysttnsourceNo ratings yet

- Approach To The Dialysis Patient Summary - Kate Wyburn FinalDocument3 pagesApproach To The Dialysis Patient Summary - Kate Wyburn Finaltnsource100% (1)

- A Basic Approach To A Patient With A Psychiatric Problem - Jullian Nasti FinalDocument3 pagesA Basic Approach To A Patient With A Psychiatric Problem - Jullian Nasti FinaltnsourceNo ratings yet

- Anzcor Guideline 9 1 3 Burns Jan16 PDFDocument4 pagesAnzcor Guideline 9 1 3 Burns Jan16 PDFtnsourceNo ratings yet

- Nursing Care PlanDocument1 pageNursing Care Planlaehaaa67% (3)

- 375 - Logic ModelDocument4 pages375 - Logic Modelapi-242134939100% (1)

- Mandatory PhilHealth Coverage of Senior Citizens Pursuant To RA 10645 02.22.2015Document33 pagesMandatory PhilHealth Coverage of Senior Citizens Pursuant To RA 10645 02.22.2015Ralph Julius L. Mendoza100% (1)

- Module 2.2 - Concept of EBP PDFDocument24 pagesModule 2.2 - Concept of EBP PDFvincyNo ratings yet

- Pharmacokinetic and PharmacodynamicDocument5 pagesPharmacokinetic and PharmacodynamicdrblondyNo ratings yet

- AphasiaDocument28 pagesAphasiaEmilio Emmanué Escobar CruzNo ratings yet

- AAH v2 Acute AsthmaDocument81 pagesAAH v2 Acute AsthmaEssa SmjNo ratings yet

- Alicia Vick Personal StatementDocument5 pagesAlicia Vick Personal Statementapi-310904234No ratings yet

- Prostate SmallDocument1 pageProstate SmallChintya Permata SariNo ratings yet

- What Is Coronary Bypass Surgery?: HeartDocument2 pagesWhat Is Coronary Bypass Surgery?: HeartSebastian BujorNo ratings yet

- Accommodative Insufficiency A Literature and Record ReviewDocument6 pagesAccommodative Insufficiency A Literature and Record ReviewPierre A. RodulfoNo ratings yet

- Case ReportDocument29 pagesCase Reportannisa hayatiNo ratings yet

- San Juan de Dios Educational Foundation, IncDocument6 pagesSan Juan de Dios Educational Foundation, Incmae- athenaNo ratings yet

- Pancreatic Islet Transplantation: Research DevelopmentsDocument4 pagesPancreatic Islet Transplantation: Research Developmentskatia83No ratings yet

- 2012-0020 EMT Practical Exam HandbookDocument122 pages2012-0020 EMT Practical Exam HandbookLuckybryan Abala100% (1)

- Thailand Southeast AsiaDocument2 pagesThailand Southeast Asiaanne marieNo ratings yet

- Moisture-Associated Skin Damage (MASD) - Tear CollectionDocument14 pagesMoisture-Associated Skin Damage (MASD) - Tear CollectionIchigo RukiaNo ratings yet

- Prevention and Management of Vascular Complications in Middle Ear and Cochlear Implant SurgeryDocument10 pagesPrevention and Management of Vascular Complications in Middle Ear and Cochlear Implant SurgerySiska HarapanNo ratings yet

- Peripheral Artery Disease: Clinical PracticeDocument11 pagesPeripheral Artery Disease: Clinical Practiceapi-311409998No ratings yet

- Mass Casualty Disaster Plan Checklist: A Template For Healthcare FacilitiesDocument18 pagesMass Casualty Disaster Plan Checklist: A Template For Healthcare FacilitiesSagrina BangunNo ratings yet

- Causes of Spontaneous Abortion 2Document23 pagesCauses of Spontaneous Abortion 2kenNo ratings yet

- (2014-10) Solomon Islands GBR Assessment ReportDocument26 pages(2014-10) Solomon Islands GBR Assessment ReportDennis MokNo ratings yet

- Thoracotomy GuidelinesDocument9 pagesThoracotomy GuidelinesMuhammad Hassan RazaNo ratings yet

- Resume - Takamura, AimeeDocument1 pageResume - Takamura, AimeeAimeeNo ratings yet

- CatalogDocument49 pagesCatalogcamelia12102013No ratings yet

- Consenso EUR TQTDocument12 pagesConsenso EUR TQTCamila Villalobos BravoNo ratings yet

- Heart Failure PDFDocument2 pagesHeart Failure PDFErmita AaronNo ratings yet