Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Mechanical Computers:: The Abacus (C. 3000 BCE)

Mechanical Computers:: The Abacus (C. 3000 BCE)

Uploaded by

Meshal M ManuelOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Mechanical Computers:: The Abacus (C. 3000 BCE)

Mechanical Computers:: The Abacus (C. 3000 BCE)

Uploaded by

Meshal M ManuelCopyright:

Available Formats

A Brief History of Computers Blaise Pascal’s - Pascaline (1645)

By

Bernard John Poole, MSIS

Associate Professor of Education and Instructional Technology This famous French philosopher and mathematician

University of Pittsburgh at Johnstown invented the first digital calculator to help his father

Johnstown, PA 15904

with his work collecting taxes. He worked on it for

three years between 1642 and 1645. The device,

Mechanical computers: called the Pascaline, resembled a mechanical

calculator of the 1940's. It could add and subtract by

The Abacus (c. 3000 BCE) the simple rotation of dials on the machine’s face.

The abacus is still a mainstay of basic

computation in some societies. Slide the beads

up and down on the rods to add and subtract.

Gottfried Wilhelm von Leibnitz’s Stepped Reckoner (1674)

Leibnitz’s Stepped Reckoner could not only add and subtract,

Napier’s Bones and Logarithms (1617) but multiply and divide as well. Interesting thing about the

John Napier, a Scotsman, invented logarithms which use lookup

Stepped Reckoner is that Leibnitz’s design was way ahead of

tables to find the solution to otherwise tedious and error-prone his time. A working model of the machine didn’t appear till

mathematical calculations. To quote Napier himself: 1791, long after the inventor was dead and gone.

Seeing there is nothing (right well-beloved Students of the

Mathematics) that is so troublesome to mathematical practice, nor

that doth more molest and hinder calculators, than the

multiplications, divisions, square and cubical extractions of great

numbers, which besides the tedious expense of time are for the

most part subject to many slippery errors, I began therefore to Joseph-Marie Jacquard and his punched card controlled looms (1804)

consider in my mind by what certain and ready art I might remove

those hindrances. Joseph-Marie Jacquard was a weaver. He was very familiar

with the mechanical music boxes and pianolas, pianos

And having thought upon many things to this purpose, I found at length some excellent brief rules to be treated of (perhaps)

played by punched paper tape, which had been around for

hereafter. But amongst all, none more profitable than this which together with the hard and tedious multiplications, divisions, some time. One day he got the bright idea of adapting the

and extractions of roots, doth also cast away from the work itself even the very numbers themselves that are to be multiplied, use of punched cards to control his looms. If you look

divided and resolved into roots, and putteth other numbers in their place which perform as much as they can do, only by carefully at the picture on the right, and those on the

addition and subtraction, division by two or division by three. following slide, you can see a continuous roll of these

cards, each linked to the other, the holes in them punched

Oughtred’s (1621) and Schickard‘s (1623] slide rule

strategically to control the pattern of the weave in the

cloth produced by the loom.

This is a slide rule from the

collection of Phil Scholl whose

All the weaver had to do was work the loom without needing to think about the design of the cloth. Brilliant!

homepage can be visited at

Jacquard revolutionized patterned textile weaving. His invention also provided a model for the input and output of

http://www.angelfire.com/ego/p

hilster/sliderule/main.html. The data in the electro-mechanical and electronic computing industry.

slide rule works on the basis of

The picture of Jacquard on the left, based on a copper portrait, was woven with the aid of one of his machines!

logarithms.

Preparing the cards with the pattern for the cloth to be woven Charles Babbage’s Analytical Engine

Here you see Jacquard’s workers

preparing the cards for the Beautiful….. The Science Museum in

looms. The looms became South Kensington, London, England has

known as Jacquard looms, and

an impressive display of Babbage’s work

today one of the premier fabric

manufacturers is named after which can also be researched on the web

Joseph-Marie Jacquard. at http://www.sciencemuseum.org.uk/.

Charles Babbage (1791-1871) - The Father of Computers

Charles Babbage is recognized today as the Father of Computers because his Lady Augusta Ada Countess of Lovelace

impressive designs for the Difference Engine and Analytical Engine Read Lady Augusta Ada’s translation of Menabrea’s

foreshadowed the invention of the modern electronic digital computer. Try

Sketch of the Analytical Engine

and get a biography of Babbage if you can. He led a fascinating life, as did all

the folks involved in the history of computers. He also invented the

cowcatcher, dynamometer, standard railroad gauge, uniform postal rates,

occulting lights for lighthouses, Greenwich time signals, heliograph

opthalmoscope. He also had an interest in cyphers and lock-picking, but Babbage owes a great debt to Lady Augusta Ada, Countess of Lovelace.

abhorred street musicians. Daughter of the famous romantic poet, Lord Byron, she was a brilliant

mathematician who helped Babbage in his work. Above all, she

documented his work, which Babbage never could bother to do. As a

Charles Babbage’s Difference Engine result we know about Babbage at all. Lady Augusta Ada also wrote

programs to be run on Babbage’s machines. For this, she is recognized

as the first computer programmer. Remember that guys. Women are

The precision machine tooling that produced just as talented as men when it comes to math, science, and

these intricate machines could not have been engineering, and society should recognize that and do its utmost to

achieved in an earlier age. Babbage’s inventions encourage girls to get into these important and lucrative fields.

were born of the advances in technology that

accompanied the Industrial Revolution. The

Difference Engine was never fully built. Babbage

drew up the blueprints for it while still an

undergrad at Cambridge University in England.

But while it was in process of being

manufactured, he got a better idea and left this

work unfinished in favor of the Analytical Engine

illustrated on the next slide.

The Analytical Engine was eventually built completely in the latter half of the 19th century, by Georg and Edvard

Schuetz as per Babbage’s blueprints. Film footage exists of the machine in operation, and it is truly a sight to

behold, a testament not only to Babbage’s genius, but also to the manufacturing prowess of the age.

You might also like

- 307.1074.3.5 (En) Air Cooled Engine Serie 1000Document172 pages307.1074.3.5 (En) Air Cooled Engine Serie 1000Lacatusu Mircea100% (1)

- Method Statement For Kamoa CampDocument28 pagesMethod Statement For Kamoa CampAdam MulengaNo ratings yet

- Triangles and Angle Sums: Practice 14.5Document1 pageTriangles and Angle Sums: Practice 14.5Meshal M ManuelNo ratings yet

- ISO 4427-1 (2019) - Polyethylene (PE) Pipes and Fittings - Part I GeneralDocument24 pagesISO 4427-1 (2019) - Polyethylene (PE) Pipes and Fittings - Part I GeneralFelipe Barrientos100% (1)

- Electrical Supplies and Materials - Docx TLE 7Document3 pagesElectrical Supplies and Materials - Docx TLE 7Meshal M Manuel100% (3)

- Nutrition Month Cert of RecognitionDocument1 pageNutrition Month Cert of RecognitionMeshal M Manuel100% (3)

- Vturn-NP16 NP20Document12 pagesVturn-NP16 NP20José Adalberto Caraballo Lorenzo0% (1)

- Shipyards in AsiaDocument200 pagesShipyards in AsiaUnmesh Lohite100% (1)

- Ict7 Las 1Document5 pagesIct7 Las 1Jessica Jane ToledoNo ratings yet

- Computer Evolution Comp6Document3 pagesComputer Evolution Comp6Jhoize Cassey Belle OrenNo ratings yet

- Com FundDocument31 pagesCom FundKenneth LorenzoNo ratings yet

- Introduction To ComputersDocument60 pagesIntroduction To ComputersPriyaSrihariNo ratings yet

- History of ComputerDocument5 pagesHistory of ComputerGlad RoblesNo ratings yet

- Las CN Ict 7 Q1 WK 1 FP PDFDocument17 pagesLas CN Ict 7 Q1 WK 1 FP PDFJohn Benedict DizonNo ratings yet

- Assignment 1 Computer Fundamentals and Programming 1 History of ComputersDocument33 pagesAssignment 1 Computer Fundamentals and Programming 1 History of ComputersCyrus De LeonNo ratings yet

- MST 103 Written Report HistoryDocument25 pagesMST 103 Written Report HistoryAira Cane EvangelistaNo ratings yet

- Bartolome Clarisse E. - Bsce 1B A111l Assignment 1Document36 pagesBartolome Clarisse E. - Bsce 1B A111l Assignment 1Cyrus De LeonNo ratings yet

- EMST History of ComputerDocument3 pagesEMST History of Computerr.cayetano.546375No ratings yet

- Gee-Lie-Activity No.1 - (Pabadora, Joel Nino F.Document7 pagesGee-Lie-Activity No.1 - (Pabadora, Joel Nino F.joel pabadoraNo ratings yet

- History of ComputersDocument50 pagesHistory of ComputersSantino Puokleena Yien GatluakNo ratings yet

- Evolution of Computers With Key ContributorsDocument31 pagesEvolution of Computers With Key ContributorsPrachi TayadeNo ratings yet

- Origin of ComputerDocument106 pagesOrigin of ComputerMenesKhidaAngelicaNo ratings yet

- Computing Devices: Otto Von GürckeDocument3 pagesComputing Devices: Otto Von GürckeIje NicolNo ratings yet

- De Leon, Cyrus Q. BSIE 1A, Assignment 1Document33 pagesDe Leon, Cyrus Q. BSIE 1A, Assignment 1Cyrus De LeonNo ratings yet

- History of ComputerDocument1 pageHistory of ComputerLinard BelmoresNo ratings yet

- Antiguos ComputadoresDocument1 pageAntiguos Computadoreswjimenez1938No ratings yet

- What Is A ComputerDocument8 pagesWhat Is A ComputerAhrvin SGNo ratings yet

- NCM 110 I Prelim I Solidum I CompleteDocument5 pagesNCM 110 I Prelim I Solidum I CompletekjayjocsinNo ratings yet

- Abhishek MBA Project ReportDocument68 pagesAbhishek MBA Project ReportjagrutiNo ratings yet

- The History of Computers: Michelle P. Navarro Tle-Ict TeacherDocument95 pagesThe History of Computers: Michelle P. Navarro Tle-Ict TeacherMichelle NavarroNo ratings yet

- Computer FundamentalsDocument52 pagesComputer FundamentalsLowell FaigaoNo ratings yet

- CP1 Lec1aDocument24 pagesCP1 Lec1ajhaz sayingNo ratings yet

- History of ComputersDocument88 pagesHistory of ComputersShane TaylorNo ratings yet

- Lecturer: Wamusi Robert Phone: 0787432609: UCU Arua Campus FS 1102 Basic ComputingDocument72 pagesLecturer: Wamusi Robert Phone: 0787432609: UCU Arua Campus FS 1102 Basic ComputingAyikoru EuniceNo ratings yet

- History of ComputersDocument86 pagesHistory of ComputersJhon Bryan CantilNo ratings yet

- The History of Computers: (Or "How We've Come A Long Way in A Short Time.")Document34 pagesThe History of Computers: (Or "How We've Come A Long Way in A Short Time.")Elvin TinioNo ratings yet

- Electronics Week5f 5Document16 pagesElectronics Week5f 5Nicole MediodiaNo ratings yet

- LIE - History of ComputerDocument88 pagesLIE - History of ComputerJustin Acuña DungogNo ratings yet

- The History of Computers: Computer ProgrammingDocument88 pagesThe History of Computers: Computer ProgrammingJane MoracaNo ratings yet

- Computer History Presentation Part1Document46 pagesComputer History Presentation Part1api-3784038100% (5)

- Evolution of ComputerDocument18 pagesEvolution of Computerbhavneet971sNo ratings yet

- Intro To ComputingDocument50 pagesIntro To ComputingJhierry Elustrado FrancoNo ratings yet

- Timeline of ComputerDocument81 pagesTimeline of ComputerKanwal AtifNo ratings yet

- History of ComputersDocument100 pagesHistory of ComputersGaurav Kumar SinghNo ratings yet

- Harsh 1Document3 pagesHarsh 1Kalyan HamberNo ratings yet

- Mind MapDocument1 pageMind MapJhuwen Acob ValdezNo ratings yet

- Module - Midterm ICTDocument76 pagesModule - Midterm ICTGracelyn EsagaNo ratings yet

- M2: History of Computer: Basic Computing PeriodsDocument9 pagesM2: History of Computer: Basic Computing PeriodsJerome LopezNo ratings yet

- Eric John Medina - EVOLUTION OF COMPUTERDocument12 pagesEric John Medina - EVOLUTION OF COMPUTEREric John Ocampo MedinaNo ratings yet

- Coumputer History PDFDocument4 pagesCoumputer History PDFFurqan AfzalNo ratings yet

- Mathematics For Computer Science Today's LectureDocument14 pagesMathematics For Computer Science Today's LectureLatha PundiNo ratings yet

- Ge Elect 2 1Document9 pagesGe Elect 2 1QUIJANO, FLORI-AN P.No ratings yet

- G1 2A History of ComputersDocument28 pagesG1 2A History of ComputersCampos , Carena JayNo ratings yet

- Cc101 Lesson 2 - Computing AgesDocument42 pagesCc101 Lesson 2 - Computing AgesGina May DaulNo ratings yet

- IT Chapter 1Document21 pagesIT Chapter 1jingerasimNo ratings yet

- Lie History of ComputerDocument6 pagesLie History of ComputerJoyceNo ratings yet

- Ict1 - Unit 1 - Lesson 1 - History of ComputingDocument5 pagesIct1 - Unit 1 - Lesson 1 - History of ComputingEverlyn D. BuglosaNo ratings yet

- HISTORY OF COMPUTER - LotaDocument1 pageHISTORY OF COMPUTER - LotaCrisia Jane LotaNo ratings yet

- The History of Computers: By: AbbypaculdoDocument55 pagesThe History of Computers: By: AbbypaculdoAbejah PaculdoNo ratings yet

- The History of Computers: (Or "How We've Come A Long Way in A Short Time.")Document34 pagesThe History of Computers: (Or "How We've Come A Long Way in A Short Time.")Elvin TinioNo ratings yet

- AbacusDocument10 pagesAbacusRavi ChawlaNo ratings yet

- History of Computers.1Document87 pagesHistory of Computers.1Rey CuntapayNo ratings yet

- Lesson 1 NotesDocument3 pagesLesson 1 NotesLiryc Andales Rosales DomingoNo ratings yet

- Com7 Act 1.3Document3 pagesCom7 Act 1.3Dhine LimbagaNo ratings yet

- The History of ComputersDocument2 pagesThe History of ComputersDanela Besana PaulinoNo ratings yet

- History of Computer1Document9 pagesHistory of Computer1Edrian AguilarNo ratings yet

- Quantum Computing: The Transformative Technology of the Qubit RevolutionFrom EverandQuantum Computing: The Transformative Technology of the Qubit RevolutionNo ratings yet

- Module Printing Weekly Reports As of October 16, 2020Document11 pagesModule Printing Weekly Reports As of October 16, 2020Meshal M ManuelNo ratings yet

- Load and Access Using Browser 1. Open Google Chrome or Any Browser E.G Mozilla Firefox, Internet Explorer and Others 2. Type: 192.168.254.254Document1 pageLoad and Access Using Browser 1. Open Google Chrome or Any Browser E.G Mozilla Firefox, Internet Explorer and Others 2. Type: 192.168.254.254Meshal M ManuelNo ratings yet

- Semi-Detailed Lesson Plan in Tvl/Tle-Ict Computer System ServicingDocument4 pagesSemi-Detailed Lesson Plan in Tvl/Tle-Ict Computer System ServicingMeshal M Manuel100% (1)

- Least Learned CompetenciesDocument2 pagesLeast Learned CompetenciesMeshal M ManuelNo ratings yet

- Module TagDocument1 pageModule TagMeshal M ManuelNo ratings yet

- CDRRMC TrainingDocument2 pagesCDRRMC TrainingMeshal M ManuelNo ratings yet

- Volcanoes EarthquakeDocument83 pagesVolcanoes EarthquakeMeshal M ManuelNo ratings yet

- Activity Design - Career GuidanceDocument1 pageActivity Design - Career GuidanceMeshal M ManuelNo ratings yet

- Certificate of Recognition: Is Given ToDocument1 pageCertificate of Recognition: Is Given ToMeshal M ManuelNo ratings yet

- Certificate of Participation: Math and Science Month Celebration 2019Document1 pageCertificate of Participation: Math and Science Month Celebration 2019Meshal M ManuelNo ratings yet

- Boy Scouts of The Philippines: Davao Oriental Council 8200 Davao OrientalDocument1 pageBoy Scouts of The Philippines: Davao Oriental Council 8200 Davao OrientalMeshal M ManuelNo ratings yet

- Nutrition Month CertificateDocument4 pagesNutrition Month CertificateMeshal M ManuelNo ratings yet

- Ship ConstructionDocument157 pagesShip ConstructionBehendu PereraNo ratings yet

- SD.010 S D: XXX - InventoryDocument67 pagesSD.010 S D: XXX - InventoryNitaiChand DasNo ratings yet

- Coal Dust Maintenance Guide - Rev8Document18 pagesCoal Dust Maintenance Guide - Rev8galuh galskiNo ratings yet

- 1 3 - 3 EN1991 1 7 Bridge Design Provisions of UK NA For EN1991 1 7 and PD6688 1 7Document14 pages1 3 - 3 EN1991 1 7 Bridge Design Provisions of UK NA For EN1991 1 7 and PD6688 1 7tim_lim12No ratings yet

- Veiland ModulesDocument13 pagesVeiland ModulesJavier FundoraNo ratings yet

- L30329 - Skate 3D - Stability Analysis Report - Rev.0Document33 pagesL30329 - Skate 3D - Stability Analysis Report - Rev.0harrys manaluNo ratings yet

- ANSWER Rule78 SampleExamDocument19 pagesANSWER Rule78 SampleExamrayzlazoNo ratings yet

- Scope of WorkDocument28 pagesScope of WorkShuhan Mohammad Ariful HoqueNo ratings yet

- Canada Easa 145Document7 pagesCanada Easa 145Marty008No ratings yet

- Rib DeckDocument38 pagesRib DeckUntuksign UpsajaNo ratings yet

- Lecture06 HandoutDocument7 pagesLecture06 HandoutBotlhe SomolekaeNo ratings yet

- Datasheet Viscosity Compensating Flow Meter Switch VKGDocument4 pagesDatasheet Viscosity Compensating Flow Meter Switch VKGJairo MoralesNo ratings yet

- 03 Direct On-Line Starter (D.o.l)Document10 pages03 Direct On-Line Starter (D.o.l)Muhammad NaguibNo ratings yet

- Sigma Ecofleet 530Document2 pagesSigma Ecofleet 530Haresh BhavnaniNo ratings yet

- 3.3 Heat and Humidity - Psychrometers and Psychrometric CalculationsDocument14 pages3.3 Heat and Humidity - Psychrometers and Psychrometric CalculationsDeepakKattimaniNo ratings yet

- Is There An Environmental Benefit From Remediation of A Contaminated SiteDocument12 pagesIs There An Environmental Benefit From Remediation of A Contaminated SiteTecnohidro Engenharia AmbientalNo ratings yet

- Mechatronics Module 2Document53 pagesMechatronics Module 2ASWATHY V RNo ratings yet

- ControllerDocument2 pagesControlleral-if0% (1)

- ME524 - Chapter 2 - Calculation of Elastic Properties of Composite - Spring 2022Document23 pagesME524 - Chapter 2 - Calculation of Elastic Properties of Composite - Spring 2022Sulaiman AL MajdubNo ratings yet

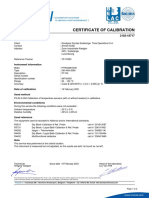

- Certificate of Calibration: Customer InformationDocument2 pagesCertificate of Calibration: Customer InformationSazzath HossainNo ratings yet

- Pump DatasheetDocument1 pagePump DatasheetNavneet SinghNo ratings yet

- Unit Conversation: Feet Inch Inch Sut Inch Feet 12 Sut Inch 8 Feet Meter 3.28Document41 pagesUnit Conversation: Feet Inch Inch Sut Inch Feet 12 Sut Inch 8 Feet Meter 3.28Er Puspendra Pratap SinghNo ratings yet

- EnergySupply A1 A3 HN 202 069Document11 pagesEnergySupply A1 A3 HN 202 069cabecavilNo ratings yet

- Pulse-Width Modulation Inverters: Pulse-Width Modulation Is The Process of Modifying The Width of The Pulses in A PulseDocument7 pagesPulse-Width Modulation Inverters: Pulse-Width Modulation Is The Process of Modifying The Width of The Pulses in A PulseEngrAneelKumarAkhani100% (1)