Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Implementing Total Quality Management in Construction Firms PDF

Implementing Total Quality Management in Construction Firms PDF

Uploaded by

Gabriel PreviattoOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Implementing Total Quality Management in Construction Firms PDF

Implementing Total Quality Management in Construction Firms PDF

Uploaded by

Gabriel PreviattoCopyright:

Available Formats

Implementing Total Quality Management

in Construction Firms

Low Sui Pheng1 and Jasmine Ann Teo2

Downloaded from ascelibrary.org by UNIVALI - UNIVERSIDADE DO VALE DO ITAJAI on 09/14/19. Copyright ASCE. For personal use only; all rights reserved.

Abstract: As building projects get larger and more complex, clients are also increasingly demanding higher standards for their delivery.

Total quality management 共TQM兲 has been recognized as a successful management philosophy in the manufacturing and service indus-

tries. TQM can likewise be embraced in the construction industry to help raise quality and productivity. Two case studies of construction

companies showed how TQM can be successfully implemented in the construction industry. The benefits experienced include reduction

in quality costs, better employee job satisfaction because they do not need to attend to defects and client complaints, recognition by

clients, work carried out correctly right from the start, subcontractors with proper quality management systems, and closer relationships

with subcontractors and suppliers. TQM performance measures were also reflected through top management commitment, customer

involvement and satisfaction, employee involvement and empowerment, customer–supplier relationships, and process improvement and

management. Finally, a framework for implementing TQM in construction is recommended.

DOI: 10.1061/共ASCE兲0742-597X共2004兲20:1共8兲

CE Database subject headings: Quality control; Project management; Construction industry; Engineering firms.

Introduction vidual at each level. Ideas of continuous learning allied to con-

cepts such as empowerment and partnership, which are facets of

Total quality management 共TQM兲 is often termed a journey, not a TQM, also imply that a change in behavior and culture is required

destination 共Burati and Oswald 1993兲. Much research has been if construction firms are to become learning organizations 共Love

done with regard to the implementation of TQM and it is believed et al. 2000兲.

that the benefits of higher customer satisfaction, better quality Idris et al. 共1996兲 showed that the electrical and electronic

products, and higher market share are often obtained following engineering industry in Malaysia has widely adopted TQM and

the adoption of TQM by construction companies. It requires a the main benefits that resulted were improved customer satisfac-

complete turnaround in corporate culture and management ap- tion, teamwork, productivity, communication, and efficiency. Mc-

proach 共Quazi and Padibjo 1997兲 as compared to the traditional Cabe 共1996兲 reported a study of UK companies from different

way of top management giving orders and employees merely industries which have already implemented TQM. The results

obeying them. showed that a majority had achieved greater success against per-

It is believed that the single most important determinant of the

formance indicators than was the average for their respective in-

success an organization in implementing TQM is its ability to

dustries. Culp 共1993兲 cited an example of HDR Inc., Omaha,

translate, integrate, and ultimately institutionalize TQM behaviors

Nebraska, a large engineering firm that has implemented TQM.

into everyday practice on the job. TQM is a way of thinking about

The experience of applying TQM concepts provided the organi-

goals, organizations, processes, and people to ensure that the right

things are done right the first time. Motwani 共2001兲 feels that zation with improvements, information, and learning that oc-

implementing TQM is a major organizational change that requires curred only because of the TQM process. This is in addition to

a transformation in the culture, process, strategic priorities, be- positive customer responses and client referrals that the organiza-

liefs, etc. of an organization. tion received as a result of implementing TQM.

TQM is an approach to improving the competitiveness, effec- There are also other means of achieving TQM success. Ford

tiveness, and flexibility of the whole organization. Oakland Motor Company has found success by implementing its own

共1995兲 observed that it is essentially a way of planning, organiz- Ford’s Q1 Award process which, in essence, involves the imple-

ing, and understanding each activity that depends on each indi- mentation of many quality principles and tools that are often as-

sociated with a TQM organization 共Stephens 1997兲.

1

Associate Professor and Vice-Dean, School of Design and According to Ghosh and Wee 共1996兲, manufacturing compa-

Environment, National Univ. of Singapore, 4 Architecture Drive, nies in Singapore have reached a certain state of development

Singapore 117566. E-mail: sdelowsp@nus.edu.sq with regard to TQM and, hence, are on their way to world-class

2

Research Assistant, Department of Building, National Univ. of manufacturing. However, their survey indicated that Japanese

Singapore, 4 Architecture Drive, Singapore 117566. manufacturing companies showed a greater commitment to TQM

Note. Discussion open until June 1, 2004. Separate discussions must than their local/regional counterparts. In a survey carried out by

be submitted for individual papers. To extend the closing date by one

the National Productivity Board in Singapore, Quazi and Padibjo

month, a written request must be filed with the ASCE Managing Editor.

The manuscript for this paper was submitted for review and possible 共1997兲 reported that out of the 300 firms surveyed, only one-third

publication on September 17, 2002; approved on August 16, 2003. This of the manufacturing companies and one-fourth of the services

paper is part of the Journal of Management in Engineering, Vol. 20, No. and construction companies had implemented TQM programs. Of

1, January 1, 2004. ©ASCE, ISSN 0742-597X/2004/1-8 –15/$18.00. those companies that have implemented TQM, most were of

8 / JOURNAL OF MANAGEMENT IN ENGINEERING © ASCE / JANUARY 2004

J. Manage. Eng., 2004, 20(1): 8-15

foreign origin. This appears to suggest that local companies were Resistance to Total Quality Management

lagging behind their foreign competitors. in Construction

The aim of this paper is to examine how TQM can be applied

more actively in the construction industry. It seeks to assist con- The factors which may cause resistance in the implementation of

tractors in identifying the steps necessary for the implementation TQM in construction are discussed below.

of TQM. For this purpose, a comparison of the benefits experi-

enced and the TQM performance measures in two case studies are Product Diversity

presented.

All buildings constructed are unique. Quality is seen as consisting

The objectives of this paper are as follows:

Downloaded from ascelibrary.org by UNIVALI - UNIVERSIDADE DO VALE DO ITAJAI on 09/14/19. Copyright ASCE. For personal use only; all rights reserved.

of those product features which meet the personalized needs of

1. To address the issue of applying TQM in the construction the customers and thereby provide product satisfaction, supple-

industry; mented with a proviso of freedom from deficiencies 共Sommerville

2. To examine possible steps for restructuring an organization and Robertson 2000兲.

for TQM; and

3. To propose an implementation framework for TQM.

Organizational Stability

The construction industry has a high number of organizational

Restructuring for Total Quality Management collapses, especially during a downturn in the economy 共Sommer-

ville and Robertson 2000兲. Thus, commitment toward TQM strat-

TQM is generally perceived to de-emphasize status distinctions egies and policies that may take several years to provide ‘‘pay

while emphasizing employee empowerment 共Plutat 1994兲. TQM offs’’ may be perceived as futile or a misdirection of resources. As

gurus preach horizontal coordination based on the flow of work compared to the head office, the building site is transitory. Teams

processes and linkages with suppliers and customers. Hunt and specially formed for a project may cease to exist after contractual

Daniel 共1993兲 envisage a TQM-oriented organization to have pro- obligations end.

cess rather than function as the basic fundamental unit of analysis.

Since a TQM organization is basically a customer-oriented Misconception of the Cost of Quality

organization, Brown et al. 共1994兲 suggested organizing to maxi-

mize customer satisfaction rather than internal efficiency. Each Baden-Hallard 共1993兲 defined the cost of quality as costs associ-

person within the organization must consider the needs of the next ated with conformance to requirements and costs associated with

person in line who uses his output. Measurements must be made nonconformance to requirements. Costs in the construction indus-

try are being compounded by prevention and appraisal costs

to find out how well the organization is meeting its customer

coupled with nonconformance costs.

needs and expectations.

Contractors often perceive TQM as an extra cost, but they do

Without upper-management involvement, commitment, and

not realize that it is not the quality that costs but rather the non-

leadership, a TQM program cannot succeed. Chase 共1993兲 sug-

conformance to quality that is expensive. The sources of costs

gested that teams should consist of employees from various parts

associated with the nonachievement of quality include the costs of

of the company to work together to improve processes. The orga-

rework, correcting errors, reacting to customer complaints, having

nization should always look toward 100% customer satisfaction

deficient project budgets due to poor planning, and missing dead-

and error-free performance. The focus should not be on the 80%

lines 共Culp 1993兲.

that is doing well, but rather on the 20% that is not. Strange and

Biggar 共1990兲 argues that the costs associated with implement-

Vaughan 共1993兲 further stressed that constantly measuring and

ing a TQM system could be substantial, depending on the size and

analyzing factors that truly impact performance and then creating

nature of the company. However, Biggar 共1990兲 pointed out that

channels to communicate the lessons learned will result in perfor-

the costs incurred from not achieving quality can cost owners up

mance improvement. to 12% of the total project cost.

Employees need to be trained and shown how to reallocate

their time and energy to studying their processes in teams, search-

ing for causes of problems, and correcting the causes, not the Implementing Total Quality Management

symptoms, once and for all. Quality improvement teams should in Construction

be set up 共Baden-Hallard 1993; Costin 1994; Dale 1994; Oakland

1995兲 to ensure that the quality mentality is instilled in everyone In developing a total quality culture in construction, one impor-

within the organization and that there is continuous improvement tant step is to develop a construction team of a main contractor

in the quality systems. and subcontractors who would commit to the quality process and

The organization should also integrate suppliers into its TQM develop a true quality attitude 共Low and Peh 1996兲. Thus, the

process. Williams 共1997兲 stated that supplier relations should main contractor should only select subcontractors who have dem-

progress in the direction of supplier partnerships with both parties onstrated quality attitude and work performance on previous jobs.

benefiting from the relationship. Both parties should seek to im- Low and Peh 共1996兲 outlined the following basic steps to imple-

prove quality and work toward the intention of forming long-term menting TQM in construction projects: 共1兲 Obtain the commit-

relationships. ment of the client to quality; 共2兲 generate awareness, educate, and

In summary, the requirements for restructuring for an organi- change the attitudes of staff; 共3兲 develop a process approach to-

zation wanting to implement TQM would include consideration ward TQM; 共4兲 prepare project quality plans for all levels of

to be given to the following 共Chase 1993; Dale 1994兲: customer work; 共5兲 institute continuous improvement; 共6兲 promote staff

focus, continuous improvement, leadership, employee involve- participation and contribution using quality control circles and

ment, teamwork, customer–supplier relationship, and process im- motivation programs; and 共7兲 review quality plans and measure

provement. performance.

JOURNAL OF MANAGEMENT IN ENGINEERING © ASCE / JANUARY 2004 / 9

J. Manage. Eng., 2004, 20(1): 8-15

Burati and Oswald 共1993兲 explained that TQM may be imple- would be enjoyed most by organizations that were not already

mented in an organization in the following three phases: The ex- certified to the ISO 9001:1994 standard.

ploration and commitment phase, the planning and preparation

phase, and the implementation phase. Chileshe 共1996兲 showed

Organization B

that most organizations in the construction industry were reluctant

to implement TQM because they felt that the ISO 9000 series was A local G8 construction firm, Organization B is known for its

enough and that they did not want to subject their employees to high-quality standards in design-and-build projects. The person-

anymore ‘‘cultural shock.’’ Organizations also felt that there were nel interviewed was the Quality Systems Manager who has

other pressing issues to consider, such as survival. In addition, worked for Organization B for three years. The firm seeks to

Downloaded from ascelibrary.org by UNIVALI - UNIVERSIDADE DO VALE DO ITAJAI on 09/14/19. Copyright ASCE. For personal use only; all rights reserved.

Love et al. 共2000兲 noted that organizations in the construction adopt the ‘‘do it right the first time’’ approach and to strive for

industry have abstained from implementing TQM practices be- zero wastage and zero defects. Like Organization A, Organization

cause they feel that the short-term benefits are relatively minimal. B is also committed to understanding the needs of its customers to

Due to the complex nature and ever-changing environment of deliver quality products through a continual improvement pro-

construction projects, Biggar 共1990兲 suggested that the manage- cess.

ment system must be flexible, sensitive to effective communica- At the time of this study, Organization B was expected to

tion, and continually improving. obtain their certification to the ISO 9001:2000 standard in the

Clients should move away from the usual practice of awarding third quarter of 2002. It was then preparing for the ISO

tenders to the lowest price and advocate rewarding the best 9001:2000 audit. The Quality System Manager agreed that certi-

designers and suppliers who could provide the best service. fication to the ISO 9001:2000 standard will help in facilitating

Mohrman et al. 共1995兲 established a correlation between various continual improvement to allow Organization B to respond more

market conditions and the application of TQM practices. This positively toward client needs and expectations. The Quality Sys-

suggests that competitive pressures will lead to the adoption of tem Manager opined that organizations will only carry out TQM

TQM. Organizations should create supplier partnerships by principles that are required in the ISO 9001:2000 standard, and

choosing suppliers based on quality rather than price. that unless an organization is aware of these principles, TQM will

not be implemented in totality. The quality system manager noted

that the new ISO 9001:2000 standard focuses on process flow that

Background of Case Studies can help to identify what needs to be controlled. This is unlike the

old ISO 9001:1994 standard which focused on individual quality

Two construction companies in Singapore who have implemented elements, thus failing to highlight the relationship between them.

TQM in their organizations were studied. The case studies aim to

examine how each organization practices TQM and the tools used

to assist them in doing so. In addition, the methods of measuring History of Total Quality Management

the performance of TQM within each organization are presented. Implementation

The two case studies were conducted in late 2001. The studies Since Organization A is a branch company of a large Japanese

made use of interviews and reviews of relevant company publi- firm, TQM was implemented right from the start. Its headquarters

cations in Singapore. in Japan sent 30 of its staff to Singapore to help with the imple-

mentation of TQM initially. The locals then learned from the

Japanese with on-the-job training and other routines. There were

Organization A

only four Japanese employees in the organization at the time of

Organization A is a G8 Japanese contractor who has involved in the study. All employees were sent for TQM training when they

local construction projects for more than 22 years. 共Note: Con- first joined the firm. The successful implementation of TQM was

struction companies in Singapore are registered with the Building largely due to the commitment of the top management. In terms

and Construction Authority’s Central Registry of Public Sector of employee empowerment, employees are aware of their respon-

Contractors in one of eight financial categories. These range from sibilities and obligations, including aspects of TQM. This is one

G1, the smallest, to G8, the largest financial category.兲 The Man- of the ways in which the organization cultivates the TQM culture

agement Representative, who has worked for the firm for 19 among its people. The organization gives the project manager full

years, was interviewed for this case study. Organization A has authority to handle the cost and quality matters of the project but

won several quality awards before, including one from a Japanese with an obligation to ensure that the budget is not exceeded. To

client for quality workmanship for a chemical plant project. This date, there has not been any major rework on construction sites

is not surprising because the quality mission of the company has and this is due, in no small way, to the well coordinated shop

incorporated certain aspects of TQM that is to: ‘‘Provide quality drawings. When asked if there was any formal measurement sys-

construction that meets customer requirements and contı́nual im- tem for the cost of quality, the Management Representative ex-

provement to enhance customer satisfaction.’’ plained that they had a system to measure the costs of defects by

At the time of this study, Organization A was audited and means of an index. This ensures that preventive actions are taken

awaiting certification to the ISO 9001:2000 standard. The Man- before defects occur. The client attends a progress and quality

agement Representative highlighted that the ISO 9001:2000 stan- meeting at least once a month to ensure that customer satisfaction

dard emphasizes continual improvement and is more systematic is attained. Organization A recently set up an objective for all

than the old ISO 9001:1994 standard which concentrated on projects: There should not be more than six complaints from cli-

documentation. Nevertheless, the Management Representative ad- ents within 6 months and this is followed up by a customer survey

mitted that the reason behind ISO 9001:2000 certification was form. The Management Representative has the responsibility to

largely motivated by regulatory requirements in Singapore and maintain the quality management system and to ensure that qual-

not because it will help in TQM implementation in the first in- ity processes are carried out properly. He is also responsible for

stance. He added that the benefits of ISO 9001:2000 certification carrying out the internal quality audits regularly and conducting

10 / JOURNAL OF MANAGEMENT IN ENGINEERING © ASCE / JANUARY 2004

J. Manage. Eng., 2004, 20(1): 8-15

the yearly management review. Top management attends this the start. The Management Representative also felt that subcon-

meeting to see if there is a need for improvement. Quality meet- tractors should be selected with care and that the main contractor

ings are held once a week in the head office to study the progress should always ensure that the subcontractors have proper quality

of all sites. In addition, quality meetings are held on site everyday management systems in place.

to allow staff to highlight problem areas on site and to make sure Since Organization B is no longer implementing TQM, it is

that these are rectified immediately. These meetings also act as difficult to see if it had benefited from its six months of initial

team-building sessions for the personnel on site. There are no implementation. But the organization has kept some of the TQM

specific task teams formed especially for TQM. It was understood principles within its company policy: Customer satisfaction, con-

that everyone in the organization is involved in running the needs tinual improvement, and close relationships with a number of

Downloaded from ascelibrary.org by UNIVALI - UNIVERSIDADE DO VALE DO ITAJAI on 09/14/19. Copyright ASCE. For personal use only; all rights reserved.

of TQM through their daily activities. Employees who contribute subcontractors and suppliers. The quality systems manager agreed

to the quality objectives of the company are rewarded through the that if TQM is properly implemented, it would require monetary

staff appraisal system and this gives them more incentives to and manpower resources as well as top management commitment.

carry out their responsibilities according to TQM principles.

Six years ago, Organization B implemented TQM for a period

of only six months before the system was abandoned. Even then, Total Quality Management Performance Measures

not all the TQM principles were implemented. What Organization

B lacked was top management commitment. When the person in Organizations A and B have different ways of measuring the per-

charge of implementing TQM left the company, the director de- formance of TQM. These are discussed below.

cided to forgo its implementation. Thus, TQM training was car-

ried out only for the directors of the organization. The quality

systems manager mentioned that many contractors have the view Top Management Commitment

that quality would cost money, take up time, and that there is no The degree of visibility and support that management takes in

TQM mindset in the Singapore construction industry as yet. The implementing a total quality environment is critical to the success

staff of Organization B found it difficult to grasp TQM concepts of TQM implementation. Organization B lacked that commitment

and would only apply what was relevant for their work. Top man- from top management, which was why TQM was unable to be

agement was not willing to commit resources for training staff, as implemented in its entirety. There were no commitments to re-

they perceived it to be time consuming. The quality system man- place the person responsible for implementing TQM and there

ager stated that contractors are already competing with time to was no sharing of TQM knowledge. In Organization A, top man-

complete projects and even if the TQM system is in place, there is agement supported TQM through the allocation of budgets, plan-

no guarantee that there will be substantial results. An interesting ning for change 共right at the beginning of implementation兲, and

comment made by the quality system manager was that Japanese providing methods of monitoring progress of construction works.

firms do not multitask their employees; thus employees can con- The main support came from the visibility of this commitment.

centrate on their specific jobs. Japanese firms employ more staff The staff from its headquarters believed that if it is clearly visible

compared to the local firms, and that is probably why Japanese that top management was committed to implementing TQM, em-

firms can ‘‘afford quality.’’ With regard to a formal measurement ployees would naturally follow suit. Management also reduced

system for the cost of quality, Organization B also used the mea- traditionally structured operational levels and unnecessary posi-

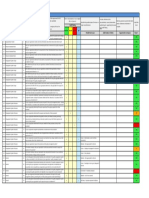

surement of defect works as a guide for quality and takes into tions within the organization. This can be seen in the lean orga-

account the cost of material used for rework. But the quality nization chart of Organization A in Fig. 1 when compared with

systems manager noted that this form of measurement is difficult that of Organization B in Fig. 2. They believed that simplifying

to undertake during construction and that it is more suited during the organization would lead to the establishment of an infrastruc-

the defects liability period. Organization B has formed long-term ture of integrated business functions participating as a team and

relationships with a few suppliers and subcontractors who know supporting the strategic vision of the company.

what Organization B expects from them in terms of quality. When

new partners are required, through design-and-build prequalifica-

tion exercises by the client, the firm will take steps to ensure that Customer Involvement and Satisfaction

the partner selected has a good track record for quality. An evalu- Organizations A and B both have customer feedback forms to

ation is conducted at the end of every contract. assess the level of customer satisfaction for each project. In addi-

tion to that, timely and dependable deliveries are ensured. Orga-

nization A aims to provide customers with timely information and

Benefits Experienced quick responses to complaints, whilst maintaining the corporate

goal of reducing the number of complaints. Organization B uti-

Organization A experienced a reduction in quality costs by ensur- lizes customer surveys, measures the percentage of repeat cus-

ing that the defect cost indices meet the requirements stated in the tomers, and uses this information to assess customer satisfaction.

project quality manual. Employees can achieve job satisfaction as Within the project structure, customer satisfaction is achieved by

they do not have to attend to defects or complaints from clients. ensuring that drawings and specifications are communicated to

The greatest benefit is recognition by clients. Clients are aware the rest of the parties should there be any changes. The parties

that Organization A had implemented TQM and subsequently rec- affected by the changes can then promptly adjust their informa-

ommended it to other clients. The Management Representative tion and help to reduce the amount of time wasted.

felt that top management commitment is essential for the decision

to implement TQM. Top management should not create an im-

Employee Involvement and Empowerment

pression of placing an additional burden on the employees. Like

Organization A, firms should convince staff that TQM would be Organization A demonstrates empowerment by allowing its

beneficial because everything will be done correctly right from project managers to take full responsibility and make decisions

JOURNAL OF MANAGEMENT IN ENGINEERING © ASCE / JANUARY 2004 / 11

J. Manage. Eng., 2004, 20(1): 8-15

Downloaded from ascelibrary.org by UNIVALI - UNIVERSIDADE DO VALE DO ITAJAI on 09/14/19. Copyright ASCE. For personal use only; all rights reserved.

Fig. 1. Chart of Organization A

for their project. Project managers are allowed to make financial they work closely. These partnerships are based on the quality of

decisions but must ensure that the project budget is not exceeded. their work and their actions in documenting improvement pro-

They should refer the issue back to the top management of Orga- cesses for continuous improvement in quality standards.

nization A if they are not sure of the appropriate decision. Em-

ployees are encouraged to present improvement and cost saving

Process Improvement and Management

suggestions to management and to a certain degree, are allowed to

self-implement solutions. However, the quality systems manager TQM is also concerned with adding value to processes, increasing

of Organization B mentioned that this system of feedback and quality levels, and raising productivity. As for raising productiv-

suggestions did not work for them. This was because the ideas ity, Organization A measures productivity on site by calculating

were either not substantial enough to warrant change or nobody the amount of finished work divided by the number of hours used

made any suggestions. When employees first joined Organization to complete the work, using fewer but higher skilled workers. A

A, they were oriented to the philosophy of the company of com- defect cost index was set up to calculate the cost and number of

mitment to never-ending improvement. They were informed of defects for all completed projects to enable the organization to

the strategic goals of the company and made to feel that they are prevent such defects from occurring again. The costs of defects

part of a team. Training was extended to the employees of Orga- during the defect liability period and the estimated costs of de-

nization A as opposed to the case of Organization B where train- fects during the project are added up. This is then divided by the

ing was only extended to top management. As Organization A had direct costs of defects, including that of subcontractors and mul-

resources from its headquarters in Japan, they were more willing tiplied by 100. The index should not have a value larger than 3.

to spend time and money on training employees in the manage- So far, all projects of Organization A were below this value. Or-

ment of TQM principles, problem-solving, and most importantly, ganization B also measures the amount of defects but they do not

teamwork. The quality systems manager of Organization B did use a special index.

not have the details of the training program implemented for top

management except that the training was to educate them about

TQM concepts and principles. The employees of Organization B Conclusion

were not sent for training as the decision against implementing

TQM was made before training could commence. Construction organizations should realize that results cannot be

gained overnight and that an organization needs time to adapt,

change, and learn. The biggest hurdle for the organization is to

Customer – Supplier Relationship

change its status quo and develop a culture that will support

As for evaluating suppliers in order to identify if the organization TQM. A framework recommended for implementation is ex-

should offer more jobs to them in the future, Organizations A and plained in Fig. 3. This consolidates research findings and suggests

B monitor the percentage or the number of orders that were de- a routine to follow for TQM implementation. In relation to Fig. 3,

livered late. Organization B has a vendor evaluation form for all it is evident that different TQM principles were implemented in

suppliers and subcontractors in terms of delivery and work per- Organizations A and B. It can be seen that the commitment of top

formance. Both organizations have a few suppliers with whom management is crucial in decision making and for successful

12 / JOURNAL OF MANAGEMENT IN ENGINEERING © ASCE / JANUARY 2004

J. Manage. Eng., 2004, 20(1): 8-15

Downloaded from ascelibrary.org by UNIVALI - UNIVERSIDADE DO VALE DO ITAJAI on 09/14/19. Copyright ASCE. For personal use only; all rights reserved.

Fig. 2. Chart of Organization B

TQM implementation. Organization B appears to lack this com- mentation: An understanding of TQM requirements 共including

mitment, which was why TQM was not fully carried out. Both customer/supplier involvement, continuous improvement, top

Organizations A and B have not used a statistical approach to management commitment, etc.兲, strategic review of education and

TQM because they were not familiar with statistical tools and felt implementation plans, provision of ample budgets and resources,

that the time and resources needed to train their employees would teamwork, training, and timely feedback.

be long and tedious. When the decision to set up a company in Nevertheless, the limitation of the two case studies is that the

Singapore was made, the headquarters of Organization A in Japan two organizations were reluctant to divulge information relating

sent their employees to Singapore to help with TQM education. to their strategy used to implement TQM and details of their

Hence, Organization A started the process of TQM implementa- training programs. In addition, the authors were also unable to

tion right from day one. It appears easier for a new organization interview the general managers of both organizations. Conse-

to train its employees in TQM practices than one whose employ- quently, the Management Representative of Organization A and

ees already have fixed ways of doing things. In the latter, TQM Quality Systems Manager of Organization B were interviewed

may be seen as an additional burden rather than to help them to instead. Although they may be able to provide appropriate infor-

improve quality. Hence, linking the two case studies with Fig. 3, mation because of their in-depth knowledge of quality systems,

it is clear that implementing TQM requires a major organizational they may not be able to articulate other information such as those

change that would transform the culture, processes, strategic pri- relating to top management commitment.

orities, and beliefs of an organization. Apart from commitment, Based on a literature review and case study interviews, the

top management must educate its employees on the need for problems that construction firms may face during the implemen-

TQM and communicate clearly to them that TQM is not an addi- tation phase of TQM could include the following.

tional burden to the organization. Instead, TQM will help to re- • Managers fail to understand the concept and philosophy be-

duce the amount of work for employees if they no longer need to hind TQM.

attend to customer complaints and defect problems. In summary, • Unless the organization is very motivated, the impetus from

the two case studies confirmed that the following factors, as high- the government authorities may be needed. This may include

lighted in Fig. 3, are important considerations for TQM imple- government grants for companies to undergo training in TQM.

JOURNAL OF MANAGEMENT IN ENGINEERING © ASCE / JANUARY 2004 / 13

J. Manage. Eng., 2004, 20(1): 8-15

Downloaded from ascelibrary.org by UNIVALI - UNIVERSIDADE DO VALE DO ITAJAI on 09/14/19. Copyright ASCE. For personal use only; all rights reserved.

Fig. 3. Framework for implementing total quality management

• TQM has yet to be proven to work in the construction industry References

and organizations may be waiting for a ‘‘champion’’ to lead

the way. Baden-Hallard, R. 共1993兲. Total quality in construction projects, Thomas

• Contractors are usually more inclined toward profit generation Telford, London.

rather than quality improvements, especially if they have al- Biggar, J. L. 共1990兲. ‘‘Total quality management in construction.’’ Trans.

Am. Assn. Cost Eng., August, 14共1兲, 1– 4.

ready met the minimum requirements for quality.

Brown, M. G., Hichcock, D. E., and Willard, M. L. 共1994兲. Why total

• In addition to the above, initial costs of implementing TQM

quality management fails and what to do about it, Irwin, New York.

are perceived to be high although these may be offset by lower Burati, J. L., and Oswald, T. H. 共1993兲. ‘‘Implementing total quality

quality costs in the long run. management in engineering and construction.’’ J. Manage. Eng., 9共4兲,

• TQM may not be so feasible for small firms. 456 – 470.

• It may be more difficult to implement TQM on a building site Chase, G. W. 共1993兲. ‘‘Effective total quality management process.’’ J.

than within the organization because the other parties in the Manage. Eng., 9共4兲, 433– 443.

project team may resist this process. Chileshe, N. 共1996兲. ‘‘An investigation into the problematic issues asso-

• Employees within the organization may be resistant to change, ciated with the implementation of Total Quality Management within a

which will render TQM education and awareness more diffi- constructional operational environment and the advocacy of their so-

cult. lutions.’’ MSc dissertation, Sheffield Hallam University, U.K.

Costin, H. 共1994兲. Readings in total quality management, Dryden, New

In conclusion, in spite of these problems, TQM embraces the

York.

philosophy, principles, procedures, and practices necessary for Culp, G. 共1993兲. ‘‘Implementing total quality management in consulting

providing customer satisfaction as well as achieving productivity engineering firm.’’ J. Manage. Eng., 9共4兲, 340–355.

and business performance in the construction industry. Commit- Dale, B. G. 共1994兲. Managing quality, 2nd Ed., Prentice-Hall, New York.

ment and perseverance are necessary when embarking on this Ghosh, B. C., and Wee, H. H. 共1996兲. ‘‘Total quality management in

journey. practice: A survey of Singapore’s manufacturing companies on their

14 / JOURNAL OF MANAGEMENT IN ENGINEERING © ASCE / JANUARY 2004

J. Manage. Eng., 2004, 20(1): 8-15

total quality management practices and objectives.’’ The TQM Maga- firms.’’ Employee Relations, 17共3兲, 26 – 41.

zine, 8共2兲, 52–54. Motwani, J. 共2001兲. ‘‘Critical factors and performance measures of total

Hunt, V., and Daniel, G. 共1993兲. Managing for quality. Integrating quality quality management.’’ The TQM Magazine, 13共4兲, 292–300.

and business process, Irwin, Burr Ridge, Ill. Oakland, J. S. 共1995兲. Total quality management: Text with cases,

Idris, M. A., McEwan, W., and Belavendram, N. 共1996兲. ‘‘The adoption Butterworth–Heinemann, London, U.K.

of ISO 9000 and total quality management in Malaysia.’’ The TQM Plutat, B. M. 共1994兲. ‘‘Total quality management: A framework for ap-

Magazine, 8共5兲, 65– 68. plication in manufacturing.’’ The TQM Magazine, 6共1兲, 44 – 49.

Love, P. E. D., Li, H., Irani, Z., and Holt, G. D. 共2000兲. ‘‘Rethinking total Quazi, H. A., and Padibjo, S. R. 共1997兲. ‘‘A journey toward total quality

quality management: Toward a framework for facilitating learning and management through ISO 9000 certification-a Singapore experience.’’

change in construction organizations.’’ The TQM Magazine, 12共2兲,

Downloaded from ascelibrary.org by UNIVALI - UNIVERSIDADE DO VALE DO ITAJAI on 09/14/19. Copyright ASCE. For personal use only; all rights reserved.

The TQM Magazine, 9共5兲, 364 –371.

107–116.

Strange, P. S., and Vaughan, G. D. 共1993兲. ‘‘Total quality management: A

Low, S. P., and Peh, K. W. 共1996兲. ‘‘A framework for implementing total

view from the playing field.’’ J. Manage. Eng., 9共4兲, 390–398.

quality management in construction.’’ The TQM Magazine, 8共5兲, 39–

46. Sommerville, J., and Robertson, H. W. 共2000兲. ‘‘A scorecard approach to

McCabe, S. 共1996兲. ‘‘Creating excellence in construction companies: UK benchmarking for total quality construction.’’ Int. J. Quality Reliabil-

contractors’ experiences of quality initiatives.’’ The TQM Magazine, ity Management, 17共4/5兲, 453– 466.

8共6兲, 14 –19. Williams, N. 共1997兲. ‘‘ISO9000 as a route to total quality management in

Mohrman, S. A., Tenkasi, R. V., Lawler, E. E., and Ledford, G. E. 共1995兲. small- to medium-sized enterprises: Snake or ladder?’’ The TQM

‘‘Total quality management: practice and outcomes in the largest US Magazine, 9共1兲, 8 –13.

JOURNAL OF MANAGEMENT IN ENGINEERING © ASCE / JANUARY 2004 / 15

J. Manage. Eng., 2004, 20(1): 8-15

You might also like

- ISO 13485 Quality Manual SampleDocument5 pagesISO 13485 Quality Manual SampleNader Shdeed33% (6)

- E 1421Document256 pagesE 1421abdelmutalabNo ratings yet

- Applying Quality StandardsDocument11 pagesApplying Quality StandardsKay Tracey Urbiztondo100% (1)

- (Asce) TQM 1Document6 pages(Asce) TQM 1Jesus sagiliNo ratings yet

- Construction Project Teams For TQM: A Factor-Element Impact ModelDocument12 pagesConstruction Project Teams For TQM: A Factor-Element Impact ModelYazan Al-HoubiNo ratings yet

- A Process Approach in Measuring Quality Costs ofDocument15 pagesA Process Approach in Measuring Quality Costs ofRommel BaesaNo ratings yet

- The Effect of Total Quality Management Implementation On Quality Performance Through Knowledge Management and Quality Culture As Mediating Variable at PT XYZDocument11 pagesThe Effect of Total Quality Management Implementation On Quality Performance Through Knowledge Management and Quality Culture As Mediating Variable at PT XYZInternational Journal of Innovative Science and Research TechnologyNo ratings yet

- Effects of Total Quality Management On Performance of Construction Industry in Tanzania: A Case of Construction Companies in MwanzaDocument8 pagesEffects of Total Quality Management On Performance of Construction Industry in Tanzania: A Case of Construction Companies in MwanzaInternational Journal of Innovative Science and Research TechnologyNo ratings yet

- Quality Assurance in Building Construction: A Questionnaire Survey of OccupantsDocument6 pagesQuality Assurance in Building Construction: A Questionnaire Survey of Occupantsrizwan hassanNo ratings yet

- Study On Factors Influencing The TQM Practices and Its ConsequencesDocument5 pagesStudy On Factors Influencing The TQM Practices and Its ConsequencesNgô DinNo ratings yet

- Quality Assurance in Building Construction: A Questionnaire Survey of OccupantsDocument6 pagesQuality Assurance in Building Construction: A Questionnaire Survey of OccupantsnandiniNo ratings yet

- Al Sinawi 2022 IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 982 012036Document9 pagesAl Sinawi 2022 IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 982 012036beemagani9No ratings yet

- Total Quality Management Practices and Organizational Performance The Mediating Roles of Strategies For Continuous ImprovementDocument17 pagesTotal Quality Management Practices and Organizational Performance The Mediating Roles of Strategies For Continuous Improvementalyssa suyatNo ratings yet

- 1 - Customer - Satisf - On TQM - 2003Document5 pages1 - Customer - Satisf - On TQM - 2003Angga Putra MargaNo ratings yet

- Toakley A R and Marosszeky M (2003) Towards Total Project Quality - A Review of Research Needs'Document10 pagesToakley A R and Marosszeky M (2003) Towards Total Project Quality - A Review of Research Needs'Hardeo Dennis ChattergoonNo ratings yet

- TQM The Construction IndustryDocument27 pagesTQM The Construction Industryducsonkt16No ratings yet

- The Total Quality Management (TQM) Journey of Malaysian Building ContractorsDocument8 pagesThe Total Quality Management (TQM) Journey of Malaysian Building ContractorsPaula Andrea Varela Hernandez100% (1)

- Study of Quality Assurance and Quality Management System in Multistroyed RCC BuildingDocument2 pagesStudy of Quality Assurance and Quality Management System in Multistroyed RCC BuildingEditor IJRITCCNo ratings yet

- Process Qualtiy 3Document10 pagesProcess Qualtiy 3Engr FaizanNo ratings yet

- Management TQM: Commerce. (Document2 pagesManagement TQM: Commerce. (Vijay Raj PanwarNo ratings yet

- Management TQM: Commerce. (Document2 pagesManagement TQM: Commerce. (Vijay Raj PanwarNo ratings yet

- Total Quality Management Frameworks: A Comparative Analysis in Construction CompaniesDocument6 pagesTotal Quality Management Frameworks: A Comparative Analysis in Construction CompaniesInternational Journal of Innovative Science and Research TechnologyNo ratings yet

- Sustainable Construction: Constructors: Who Should Read This Factsheet?Document5 pagesSustainable Construction: Constructors: Who Should Read This Factsheet?Chris FindlayNo ratings yet

- (Chase, G.W., 1993) EFFECTIVE TOTAL QUALITY MANAGEMENT (TQM) PROCESS FOR CONSTRUCTIONDocument11 pages(Chase, G.W., 1993) EFFECTIVE TOTAL QUALITY MANAGEMENT (TQM) PROCESS FOR CONSTRUCTIONViraj RaneNo ratings yet

- TQM in Construction Management A ReviewDocument6 pagesTQM in Construction Management A ReviewEditor IJTSRDNo ratings yet

- TQM AssignmentDocument13 pagesTQM Assignmentapi-477659838No ratings yet

- Study of Quality Management in Construction Projects: KeywordsDocument11 pagesStudy of Quality Management in Construction Projects: KeywordsJassimar SinghNo ratings yet

- Quality Management Practice in Highway ConstructionDocument19 pagesQuality Management Practice in Highway ConstructionSimon DunnNo ratings yet

- 28-Toward Managing Quality Cost Case StudyDocument21 pages28-Toward Managing Quality Cost Case StudyIslamSharafNo ratings yet

- Code of Quality Management Guide To BestDocument62 pagesCode of Quality Management Guide To BestYusuf TrunkwalaNo ratings yet

- Framework BPRDocument136 pagesFramework BPRNgan Tran Nguyen ThuyNo ratings yet

- 1 s2.0 S2090447922001885 MainDocument15 pages1 s2.0 S2090447922001885 Mainwelamoningka72No ratings yet

- The Total Quality Management TQM Journey of MalaysDocument8 pagesThe Total Quality Management TQM Journey of MalaysMariaNo ratings yet

- (Rounds and Chi 1985) TOTAL QUALITY MANAGEMENT FOR CONSTRUCTIONDocument12 pages(Rounds and Chi 1985) TOTAL QUALITY MANAGEMENT FOR CONSTRUCTIONViraj RaneNo ratings yet

- TQM ReportDocument3 pagesTQM ReportTom OwtramNo ratings yet

- Construction Management and EconomicsDocument13 pagesConstruction Management and Economics512781No ratings yet

- Ms Construction & Engineering ManagementDocument10 pagesMs Construction & Engineering ManagementNosharwhan AdilNo ratings yet

- (Forza & Filippini, 1998) TQM Impact On Quality Conformance and Customer Satisfaction A Causal ModelDocument20 pages(Forza & Filippini, 1998) TQM Impact On Quality Conformance and Customer Satisfaction A Causal ModelYounes El ManzNo ratings yet

- Cmmi GovDocument4 pagesCmmi Goveng.emanahmed2014No ratings yet

- Adopting Total Quality ManagmentDocument8 pagesAdopting Total Quality Managmentmoma3175No ratings yet

- Study of Quality Management in Construction Projects 2011Document12 pagesStudy of Quality Management in Construction Projects 2011Ages RahmanudinNo ratings yet

- Quality Management SystematconstructionprojectsDocument6 pagesQuality Management SystematconstructionprojectsChidi OkoloNo ratings yet

- Harkan, 2007Document11 pagesHarkan, 2007Rashid JehangiriNo ratings yet

- Evaluation On The Application of Quality Management System in Tanzania Building Construction ProjectsDocument6 pagesEvaluation On The Application of Quality Management System in Tanzania Building Construction ProjectsilovevinaNo ratings yet

- TQM - Lesson 1 Introduction To TQMDocument3 pagesTQM - Lesson 1 Introduction To TQMCzamille Rivera GonzagaNo ratings yet

- Ali, A.S. and Rahmat, I. (2010) The Performance Measurement of Construction Projects Managed by ISO-Certified Contractors in MalaysiaDocument11 pagesAli, A.S. and Rahmat, I. (2010) The Performance Measurement of Construction Projects Managed by ISO-Certified Contractors in MalaysiaDavid SabaflyNo ratings yet

- Quality Management at Construction Projects: Case Study of A Stormwater Network ProjectDocument9 pagesQuality Management at Construction Projects: Case Study of A Stormwater Network Projectmohammad hamdanNo ratings yet

- Organization Performance Improvement Using TQMDocument6 pagesOrganization Performance Improvement Using TQMaerdaitNo ratings yet

- TQM - Lesson 1 Introduction To TQMDocument3 pagesTQM - Lesson 1 Introduction To TQMCzamille Rivera GonzagaNo ratings yet

- Finals TQMDocument12 pagesFinals TQMJune philip ruizNo ratings yet

- Total Quality Management & Business ExcellenceDocument13 pagesTotal Quality Management & Business ExcellenceMichael AngeloNo ratings yet

- Quality Management System at Construction Projects: April 2015Document6 pagesQuality Management System at Construction Projects: April 2015Tushar KambleNo ratings yet

- Employee Involvement As A Key Determinant of Core Quality Management PracticesDocument19 pagesEmployee Involvement As A Key Determinant of Core Quality Management PracticesAntonio LopezNo ratings yet

- Kazaz, 2005 - Determination of Quality Level in Mass Housing Projects in TurkeyDocument8 pagesKazaz, 2005 - Determination of Quality Level in Mass Housing Projects in TurkeyDavid MartinezNo ratings yet

- Assessment of Quality Management Practices of Building Construction Firms in Uganda: A Case of Kamwenge DistrictDocument10 pagesAssessment of Quality Management Practices of Building Construction Firms in Uganda: A Case of Kamwenge DistrictChidi OkoloNo ratings yet

- Application of Costing System in The Small and Medium Sized Enterprises SME in TurkeyDocument9 pagesApplication of Costing System in The Small and Medium Sized Enterprises SME in TurkeySantosh DeshpandeNo ratings yet

- 123case Studyxyzzz PDFDocument9 pages123case Studyxyzzz PDFAnees Malik100% (1)

- Implementation of TQM: A Case Study in An Auto Company: Asia-Pacific Business ReviewDocument9 pagesImplementation of TQM: A Case Study in An Auto Company: Asia-Pacific Business ReviewShashi VermaNo ratings yet

- Paper IEIDocument6 pagesPaper IEIAssefa MogesNo ratings yet

- Guide for Asset Integrity Managers: A Comprehensive Guide to Strategies, Practices and BenchmarkingFrom EverandGuide for Asset Integrity Managers: A Comprehensive Guide to Strategies, Practices and BenchmarkingNo ratings yet

- Quality AssuranceDocument2 pagesQuality AssuranceAimee Gutierrez100% (1)

- Isu Module Template Subject: IT BPO 3Document13 pagesIsu Module Template Subject: IT BPO 3anne pascuaNo ratings yet

- Research Paper TQMDocument6 pagesResearch Paper TQMDrRam Singh KambojNo ratings yet

- M&E NoteDocument358 pagesM&E NoteAlex Choong100% (2)

- Fajardo, Jolina Mae (TQM Act.2)Document1 pageFajardo, Jolina Mae (TQM Act.2)Jolina mae fajardoNo ratings yet

- Total Quality Management Multiple Choice PDFDocument30 pagesTotal Quality Management Multiple Choice PDFNeel100% (1)

- Quality Assurance 608Document42 pagesQuality Assurance 608ENTREPRENEUR 8211No ratings yet

- Reviews of Standards and Related Material : Statistical Standards and ISO, Part 1Document10 pagesReviews of Standards and Related Material : Statistical Standards and ISO, Part 1Gaurav GuptaNo ratings yet

- Management Review: Dd-Mmm-YyyyDocument30 pagesManagement Review: Dd-Mmm-YyyyMani Rathinam RajamaniNo ratings yet

- TPM TQMDocument5 pagesTPM TQMSunny KumarNo ratings yet

- MODULE 4 Project-Quality-Management1Document52 pagesMODULE 4 Project-Quality-Management1Tewodros TadesseNo ratings yet

- MCQ PomDocument16 pagesMCQ Pomrohit khannaNo ratings yet

- Anixter Standard Reference 1179 Guide enDocument36 pagesAnixter Standard Reference 1179 Guide enVasile SilionNo ratings yet

- Creating A Culture of Excellence: How Healthcare Leaders Can Build and Sustain Continuous ImprovementDocument52 pagesCreating A Culture of Excellence: How Healthcare Leaders Can Build and Sustain Continuous ImprovementEd FitzgeraldNo ratings yet

- ISO CrossWalk WebDocument27 pagesISO CrossWalk WebNguyen Tan HiepNo ratings yet

- IATF 16949 - Guia Transicion - BSIDocument12 pagesIATF 16949 - Guia Transicion - BSIrenanmastacheNo ratings yet

- Prince2 Prep4sure Prince2-Practitioner v2019-05-11 by Mark 162q PDFDocument53 pagesPrince2 Prep4sure Prince2-Practitioner v2019-05-11 by Mark 162q PDFfaraonxxx100% (1)

- Acquin Program Akkreditation ESGDocument24 pagesAcquin Program Akkreditation ESGbukan hpNo ratings yet

- Software Quality ManagementDocument33 pagesSoftware Quality ManagementSamuel LambrechtNo ratings yet

- Iso 9001 2015Document15 pagesIso 9001 2015Julio NogueraNo ratings yet

- Software Quality Assurance QB PDFDocument4 pagesSoftware Quality Assurance QB PDFnagarajan888No ratings yet

- Total Quality Management (TQM) : Dr. Md. Mamun Habib Associate ProfessorDocument8 pagesTotal Quality Management (TQM) : Dr. Md. Mamun Habib Associate ProfessorMeer Mustafa NayeemNo ratings yet

- Business: Unit 3 Quality Progress QuizDocument3 pagesBusiness: Unit 3 Quality Progress QuizChhayNo ratings yet

- Ch.2 Management HistoryDocument54 pagesCh.2 Management HistoryFarida SerrygmNo ratings yet

- Final Leadership & Management Examination: I. Choose The Most Correct AnswerDocument5 pagesFinal Leadership & Management Examination: I. Choose The Most Correct Answerhasan ahmd100% (1)

- ISO 9001 2015 Internal Audit Checklist2 SampleDocument1 pageISO 9001 2015 Internal Audit Checklist2 SampleMuh MustagfirinNo ratings yet

- Introduction To Innovation Management System: - What It Is and Why It Is ImportantDocument13 pagesIntroduction To Innovation Management System: - What It Is and Why It Is Importantengr_rpcurbanoNo ratings yet