Professional Documents

Culture Documents

The Limits of Investment Theory: Full Text

The Limits of Investment Theory: Full Text

Uploaded by

Lorjie Bargaso BationOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

The Limits of Investment Theory: Full Text

The Limits of Investment Theory: Full Text

Uploaded by

Lorjie Bargaso BationCopyright:

Available Formats

The Limits of Investment Theory

Publication info: Dow Jones Institutional News ; New York [New York]14 Apr 2018.

ProQuest document link

FULL TEXT

by Steven D. Bleiberg

More than 40 years ago, Tom Wolfe gently skewered the multidecade ascendancy of art theory in The Painted

Word, a book triggered by the following statement in a 1974 New York Times review of an exhibition of realist

painters by the art critic Hilton Kramer: "Realism does not lack its partisans, but it does rather conspicuously lack a

persuasive theory....[T]o lack a persuasive theory is to lack something crucial..." In other words (Wolfe's words),

"without a theory, I can't see a painting."

Studying finance in business school the year after the book's publication, I was struck by the similarities between

what Wolfe described in the world of art and what was then happening in the world of finance. Modern portfolio

theory, or MPT -- a body of work developed in the 1950s and '60s that asserts we can quantify the relationship

between risk and return, and concludes that active investment management is fruitless because markets

efficiently price in all relevant information -- was beginning to dominate investment thinking. And yet, investing

isn't a theoretical exercise, any more than viewing a work of art.

Investors' devotion to modern portfolio theory has only strengthened over time, with the rise of passive investing

and the struggles of active managers. Many investors now think it's a waste of time to try to understand anything

about the companies in which they invest. MPT tells them to just buy the index and ignore company details. But

the pre-MPT view of the world still holds valuable insights. To illustrate, let's consider three questions, and contrast

the pre- and post-MPT answers.

What is a stock? Fifty years ago, the answer was simple: Shares represent ownership of a business. Then MPT

came along and told us that individual stocks were really just a statistical cog in a portfolio, of interest only for

their expected return and volatility. The main thing that mattered was a stock's level of "systematic risk," or how its

behavior over time related to the behavior of the overall market, a relationship captured by a statistic called beta.

The "stock specific" risk of an individual stock could be diversified away by holding many stocks. Later, MPT broke

this systematic risk down into multiple factor risks beyond the original beta -- factors such as company size,

valuation, growth, leverage, and more. Today, when looking back at a stock's return, we attribute that performance

to its factor exposures, and show how the various "factor returns" drove the stock.

But this is getting things precisely backward. As an investor from 1968 could tell us, stocks do well or poorly

because the underlying businesses do well or poorly. After the fact, we can use stock returns to derive a set of

factor returns, but it is a mistake to view the factor returns as if they have an independent existence, driving the

returns of individual stocks as if in a vacuum.

Why have stocks performed better than bonds? Modern investment analysis focuses on something called the

"equity risk premium," or ERP, the margin by which stocks are expected to outperform bonds. To read most

analyses of the ERP, you would think it is a mysterious force of nature, like gravity. But there is no mystery. Our

1968 investor knew that every company, regardless of industry, is trying to do the same thing: take a dollar of

capital and, net of the cost of that capital, turn it into something more than a dollar. That is by definition how a

company grows the value of its business.

Over time, companies have been able to do just that, and the long-term appreciation in the stock market reflects

PDF GENERATED BY SEARCH.PROQUEST.COM Page 1 of 3

(and has been well correlated with) the return on invested capital that businesses have earned. Bonds, by their

nature, don't offer the kind of upside participation in the value of a business that equities do. The fact that equities

are more volatile than bonds is just a function of the range of outcomes that each type of security offers.

What is the role of an index? Fifty years ago, an index was just a measure of overall market performance. But under

MPT, an index represents the optimal portfolio. To reach that conclusion, one has to assume that we all agree on

how to define and measure risk, which is unrealistic. The logic of indexing ignores the fact that not all businesses

are worth owning, and simply says "buy them all."

What's more, the use of indexing has had unintended consequences on the behavior of asset owners and asset

managers; it changes the focus of both away from "which businesses are good businesses worth owning?" to

"how do we look relative to the index?" Focusing on the second question makes it less likely that you will

successfully answer the first.

MPT is an elegant body of theory that has contributed greatly to our understanding of investing. But it is a model

of the way the world works, not a description of the real world. The relationship between risk and return isn't rigidly

quantifiable; it might be better thought of as another of the many "trade-offs" that economists study.

Ultimately, equity investors are buying into actual businesses and would be better served by seeking to understand

them: Do they have competitive advantages that enable them to earn good returns on invested capital? Are those

advantages sustainable?

Thinking about stocks this way -- as real businesses, rather than aggregates of return and volatility statistics -- is

something many investors have lost sight of since the rise of MPT. In a world where so many people aren't even

bothering to try to understand those businesses, the opportunities for those who make the effort are even greater.

--

Steven D. Bleiberg is a portfolio manager at Epoch Investment Partners in New York. This essay is adapted from

"The Limits of Theory," a white paper published this month by Epoch and available at eipny.com.

To subscribe to Barron's, visit http://www.barrons.com/subscribe

(END)

April 14, 2018 06:00 ET (10:00 GMT)

DETAILS

Subject: Theory; Investments; Stock exchanges; Volatility

Location: New York

People: Wolfe, Tom

Company / organization: Name: New York Times Co; NAICS: 511110, 511120, 515112, 515120

Publication title: Dow Jones Institutional News; New York

Publication year: 2018

Publication date: Apr 14, 2018

Publisher: Dow Jones &Company Inc

Place of publication: New York

PDF GENERATED BY SEARCH.PROQUEST.COM Page 2 of 3

Country of publication: United States, New York

Publication subject: Business And Economics

Source type: Wire Feeds

Language of publication: English

Document type: News

ProQuest document ID: 2024919063

Document URL: https://search.proquest.com/docview/2024919063?accountid=31259

Copyright: Copyright Dow Jones &Company Inc Apr 14, 2018

Last updated: 2018-04-15

Database: ProQuest Central

Database copyright 2019 ProQuest LLC. All rights reserved.

Terms and Conditions Contact ProQuest

PDF GENERATED BY SEARCH.PROQUEST.COM Page 3 of 3

You might also like

- Solution Manual For International Financial Management 8th Edition Eun, ResnickDocument9 pagesSolution Manual For International Financial Management 8th Edition Eun, Resnicka456989912No ratings yet

- Raising Capital: Get the Money You Need to Grow Your BusinessFrom EverandRaising Capital: Get the Money You Need to Grow Your BusinessRating: 3 out of 5 stars3/5 (1)

- ECF Group16Document26 pagesECF Group16Priyank ShahNo ratings yet

- Comparative Financial Ratios For Airline Industry in The PhilippinesDocument11 pagesComparative Financial Ratios For Airline Industry in The PhilippinesMarlene Regalado100% (1)

- Solution For Case 10 Valuation of Common StockDocument8 pagesSolution For Case 10 Valuation of Common StockHello100% (1)

- Due Diligence ReportDocument139 pagesDue Diligence Reportkamara100% (1)

- BA 99.1 Course OutlineDocument10 pagesBA 99.1 Course OutlineCharmaine Bernados BrucalNo ratings yet

- IPOsDocument186 pagesIPOsBhaskkar SinhaNo ratings yet

- Shareholder Value: Jan 25th 2001 From The Economist Print EditionDocument3 pagesShareholder Value: Jan 25th 2001 From The Economist Print EditionAnisha GyawaliNo ratings yet

- Stock Analysis Strategy For US's Stock Market Based On Risk, Profitability, and Market Value InsightsDocument5 pagesStock Analysis Strategy For US's Stock Market Based On Risk, Profitability, and Market Value InsightsAsmaa BaaboudNo ratings yet

- Underpricing and Top Brand CompaniesDocument26 pagesUnderpricing and Top Brand CompaniesD. AtanuNo ratings yet

- Research Paper On NyseDocument5 pagesResearch Paper On Nysecats1yax100% (1)

- This Content Downloaded From 37.111.141.85 On Wed, 29 Sep 2021 08:41:17 UTCDocument21 pagesThis Content Downloaded From 37.111.141.85 On Wed, 29 Sep 2021 08:41:17 UTCTahir SajjadNo ratings yet

- Why Do Companies Go PublicDocument38 pagesWhy Do Companies Go Publicroberan10No ratings yet

- Full Paper VALUATION OF TARGET FIRMS IN MERGERS AND ACQUISITIONS A CASE STUDY ON MERGERDocument19 pagesFull Paper VALUATION OF TARGET FIRMS IN MERGERS AND ACQUISITIONS A CASE STUDY ON MERGERPaul GhanimehNo ratings yet

- Evans Jovanovic 1989Document21 pagesEvans Jovanovic 1989Kevin AndrewNo ratings yet

- Kripto 4Document32 pagesKripto 4Hanafi IndahNo ratings yet

- Why Do Firms Go Public Chapter SSRNDocument45 pagesWhy Do Firms Go Public Chapter SSRNVishal Sadanand SankheNo ratings yet

- Bushee-2004-Journal of Applied Corporate FinanceDocument10 pagesBushee-2004-Journal of Applied Corporate Financeaa2007No ratings yet

- LBOs From 1999 To 2009Document86 pagesLBOs From 1999 To 2009rolandsudhofNo ratings yet

- Trust Markets GovDocument10 pagesTrust Markets GovwhitestoneoeilNo ratings yet

- Sharma Seraphim Je38Document29 pagesSharma Seraphim Je38Irisha AnandNo ratings yet

- Regulation of Crypto AssetsDocument23 pagesRegulation of Crypto AssetsdavNo ratings yet

- Thesis Topics On Stock MarketDocument7 pagesThesis Topics On Stock MarketCustomThesisPapersSingapore100% (2)

- Essay Topics For PsychologyDocument5 pagesEssay Topics For Psychologylwfdwwwhd100% (2)

- Big Business Is Beginning To Accept Broader Social Responsibilities (22 Aug, Economist)Document11 pagesBig Business Is Beginning To Accept Broader Social Responsibilities (22 Aug, Economist)shewaxedlyricalNo ratings yet

- Philip J. Romero - Tucker Balch - Hedge Fund Secrets - An Introduction To Quantitative Portfolio Management-Business Expert Press (2018)Document117 pagesPhilip J. Romero - Tucker Balch - Hedge Fund Secrets - An Introduction To Quantitative Portfolio Management-Business Expert Press (2018)Mohamed Hussien100% (1)

- Theory of Ipo WavesDocument39 pagesTheory of Ipo WavesVanyaa KansalNo ratings yet

- Investing in Junk Bonds: Inside the High Yield Debt MarketFrom EverandInvesting in Junk Bonds: Inside the High Yield Debt MarketRating: 3 out of 5 stars3/5 (1)

- What Are Companies ForDocument12 pagesWhat Are Companies ForSavitri AyuNo ratings yet

- Final Individual Exam - Pham Thi Huyen Trang K10 - Financial StatementDocument5 pagesFinal Individual Exam - Pham Thi Huyen Trang K10 - Financial StatementHuyền Trang Phạm ThịNo ratings yet

- Credit Ratings As Coordination MechanismsDocument39 pagesCredit Ratings As Coordination MechanismscherenfantasyNo ratings yet

- Building Public TrustDocument9 pagesBuilding Public TrustworldbestNo ratings yet

- Anot Bib 1st DRFTDocument7 pagesAnot Bib 1st DRFTapi-707178590No ratings yet

- Why Do Companies Go Public? An Empirical Analysis: Marco Pagano, Fabio Panetta, and Luigi ZingalesDocument38 pagesWhy Do Companies Go Public? An Empirical Analysis: Marco Pagano, Fabio Panetta, and Luigi ZingalesEgi SatriaNo ratings yet

- Corporate Governance and IPO Underpricing: Evidence From The Italian MarketDocument39 pagesCorporate Governance and IPO Underpricing: Evidence From The Italian MarketminnvalNo ratings yet

- Political Economy DissertationDocument5 pagesPolitical Economy DissertationPayToWriteAPaperMinneapolis100% (1)

- Venture Capital and The Performance of Blockchain Technology-Based Firms: Evidence From Initial Coin Offerings (Icos)Document46 pagesVenture Capital and The Performance of Blockchain Technology-Based Firms: Evidence From Initial Coin Offerings (Icos)uknickruckNo ratings yet

- NewLaw New Rules: A conversation about the future of the legal services industryFrom EverandNewLaw New Rules: A conversation about the future of the legal services industryNo ratings yet

- Big Business Is Beginning To Accept Broader Social ResponsibilitiesDocument7 pagesBig Business Is Beginning To Accept Broader Social ResponsibilitiesnickNo ratings yet

- Trying To Grasp The Intangible: Leading EdgeDocument4 pagesTrying To Grasp The Intangible: Leading Edgekkv_phani_varma5396No ratings yet

- Summary of Louis C. Gerken & Wesley A. Whittaker's The Little Book of Venture Capital InvestingFrom EverandSummary of Louis C. Gerken & Wesley A. Whittaker's The Little Book of Venture Capital InvestingNo ratings yet

- MP15-03 (Nabeel Ahmad)Document4 pagesMP15-03 (Nabeel Ahmad)Umar DrazNo ratings yet

- New Investment ParadigmDocument3 pagesNew Investment ParadigmJeremy HeffernanNo ratings yet

- Factiva 20190909 2242Document4 pagesFactiva 20190909 2242Jiajun YangNo ratings yet

- Internship 20117Document44 pagesInternship 20117Tangirala AshwiniNo ratings yet

- June 2011 TrialDocument21 pagesJune 2011 TrialjackefellerNo ratings yet

- Venture Capital: April 2013Document38 pagesVenture Capital: April 2013Shruti PalavNo ratings yet

- Trying To Save The World With Company Law? Some ProblemsDocument22 pagesTrying To Save The World With Company Law? Some Problemsfatima amjadNo ratings yet

- Value: InvestorDocument4 pagesValue: InvestorAlex WongNo ratings yet

- The Big Market DelusionDocument38 pagesThe Big Market DelusionsarpbNo ratings yet

- 2376 BarrouxDocument3 pages2376 BarrouxWendy SequeirosNo ratings yet

- Quarterly Journal of Economics: Vol. 134 2019 Issue 4Document71 pagesQuarterly Journal of Economics: Vol. 134 2019 Issue 4franco hautevilleNo ratings yet

- 193 Uday Kumar - Online Trading-AngelDocument62 pages193 Uday Kumar - Online Trading-AngelMohmmedKhayyumNo ratings yet

- Cryptocurrencies & Initial Coin Offerings: Are They Scams? - An Empirical StudyDocument7 pagesCryptocurrencies & Initial Coin Offerings: Are They Scams? - An Empirical Studymarsela gaxhaNo ratings yet

- Envoping: Or Interacting with the Operating Environment During the ''Age of Regulation''From EverandEnvoping: Or Interacting with the Operating Environment During the ''Age of Regulation''No ratings yet

- Master Thesis Venture CapitalDocument8 pagesMaster Thesis Venture Capitalbriannajohnsonwilmington100% (2)

- International Treasurer - October 2008 - The Financial Crisis Heats UpDocument16 pagesInternational Treasurer - October 2008 - The Financial Crisis Heats UpitreasurerNo ratings yet

- Research Paper On Rent SeekingDocument7 pagesResearch Paper On Rent Seekingafnkqsrmmueqal100% (1)

- Triantis (2001)Document19 pagesTriantis (2001)jpgallebaNo ratings yet

- Master Thesis Ipo UnderpricingDocument8 pagesMaster Thesis Ipo Underpricingkezevifohoh3100% (3)

- The Journal of Finance - March 1994 - PETERSEN - The Benefits of Lending Relationships Evidence From Small Business DataDocument35 pagesThe Journal of Finance - March 1994 - PETERSEN - The Benefits of Lending Relationships Evidence From Small Business DatahaadiNo ratings yet

- Mergers and Acquisitions in Banking and FinanceDocument317 pagesMergers and Acquisitions in Banking and FinanceSunil ShawNo ratings yet

- CURRICULUM VITAE ExampleDocument1 pageCURRICULUM VITAE ExampleLorjie Bargaso BationNo ratings yet

- Resolution Realignment Sample FormatDocument7 pagesResolution Realignment Sample FormatLorjie Bargaso BationNo ratings yet

- Office of The Punong BarangayDocument7 pagesOffice of The Punong BarangayLorjie Bargaso Bation100% (1)

- First Cry of RebellionDocument3 pagesFirst Cry of RebellionLorjie Bargaso BationNo ratings yet

- SK LogoDocument1 pageSK LogoLorjie Bargaso BationNo ratings yet

- First Cry of RebellionDocument3 pagesFirst Cry of RebellionLorjie Bargaso BationNo ratings yet

- Know Thy Self: An Input On Self-AwarenessDocument12 pagesKnow Thy Self: An Input On Self-AwarenessLorjie Bargaso BationNo ratings yet

- Magtunod Purok Members 701STDocument3 pagesMagtunod Purok Members 701STLorjie Bargaso BationNo ratings yet

- Magtunod Purok MembersDocument2 pagesMagtunod Purok MembersLorjie Bargaso BationNo ratings yet

- Lumon Members List Per Committe - BagangaDocument3 pagesLumon Members List Per Committe - BagangaLorjie Bargaso BationNo ratings yet

- Lorjie Bargaso BationDocument3 pagesLorjie Bargaso BationLorjie Bargaso BationNo ratings yet

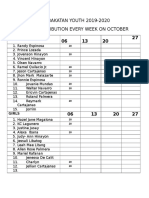

- PAGBAKATAN YOUTH 2019-2020 Youth Distribution Every Week On OctoberDocument4 pagesPAGBAKATAN YOUTH 2019-2020 Youth Distribution Every Week On OctoberLorjie Bargaso BationNo ratings yet

- Book Review On Smoke and MirrorsDocument1 pageBook Review On Smoke and MirrorsLorjie Bargaso BationNo ratings yet

- All That Matters - ChristopherDocument33 pagesAll That Matters - ChristopherLorjie Bargaso BationNo ratings yet

- Lesson 4 Philo.Document4 pagesLesson 4 Philo.Lorjie Bargaso BationNo ratings yet

- Consent To Act As ParticipantDocument1 pageConsent To Act As ParticipantLorjie Bargaso BationNo ratings yet

- PAGBAKATAN YOUTH 2019-2020 Youth Distribution Every Week On OctoberDocument4 pagesPAGBAKATAN YOUTH 2019-2020 Youth Distribution Every Week On OctoberLorjie Bargaso BationNo ratings yet

- HinduismDocument77 pagesHinduismLorjie Bargaso BationNo ratings yet

- Blackrick Strategic FundsDocument31 pagesBlackrick Strategic FundssmysonaNo ratings yet

- How To Trade Stocks and BondsDocument28 pagesHow To Trade Stocks and Bondsmohitjainrocks100% (1)

- FED Master Direction No. 5 External Commercial Borrowings, Trade Credit Dec 2021Document27 pagesFED Master Direction No. 5 External Commercial Borrowings, Trade Credit Dec 2021Prabhat SinghNo ratings yet

- Lateritic Ore Capability ProfileDocument4 pagesLateritic Ore Capability Profileفردوس سليمانNo ratings yet

- Memorandum-Association of Construction Company-Takeovr of Propritary ConcernDocument8 pagesMemorandum-Association of Construction Company-Takeovr of Propritary ConcernVamshi Krishna100% (3)

- FaxForm en UsDocument1 pageFaxForm en UsEjah ChyslcNo ratings yet

- Accounting For IntangiblesDocument14 pagesAccounting For Intangiblesmanoj17188100% (2)

- Afar Section 402: Business CombinationsDocument3 pagesAfar Section 402: Business CombinationsDianna Tercino IINo ratings yet

- Study The Awareness of Mutual Fund in Mumbai PDFDocument48 pagesStudy The Awareness of Mutual Fund in Mumbai PDFnikki karma100% (1)

- Consolidated FS Subsequent To Date of Purchase TypeDocument158 pagesConsolidated FS Subsequent To Date of Purchase TypeSassy OcampoNo ratings yet

- Over The Counter Exchange of IndiaDocument3 pagesOver The Counter Exchange of IndiaDipali ManjuchaNo ratings yet

- Agent Banking in Mobile ApplicationDocument7 pagesAgent Banking in Mobile ApplicationCielo Cuisia0% (1)

- NOT To Sell in MayDocument23 pagesNOT To Sell in Maynom1237100% (1)

- Mark Scheme (Results) January 2008: GCE Accounting (6002) Paper 1Document20 pagesMark Scheme (Results) January 2008: GCE Accounting (6002) Paper 1Shah RahiNo ratings yet

- Balance Sheet Management - BFMDocument4 pagesBalance Sheet Management - BFMakvgauravNo ratings yet

- Ratio AnalysisDocument46 pagesRatio AnalysisRoshan RoyNo ratings yet

- (Company) : Basic Exit Multiples Cash SweepDocument26 pages(Company) : Basic Exit Multiples Cash Sweepw_fibNo ratings yet

- CIR v. PLDTDocument2 pagesCIR v. PLDTKing Badong100% (1)

- How To Leverage Market Contango and Backwardation - Futures MagazineDocument2 pagesHow To Leverage Market Contango and Backwardation - Futures Magazinethirusays29No ratings yet

- KIA India Dealer Application FormDocument22 pagesKIA India Dealer Application FormAditya BhalotiaNo ratings yet

- Review of Accounting Process 1Document2 pagesReview of Accounting Process 1Stacy SmithNo ratings yet

- Intermediate Accounting Chapters 19 21Document61 pagesIntermediate Accounting Chapters 19 21Jonathan NavalloNo ratings yet

- AP - TestbankDocument22 pagesAP - TestbankRamon Jonathan SapalaranNo ratings yet

- J. Kumar Infraprojects: Quality Urban Infra PlayDocument14 pagesJ. Kumar Infraprojects: Quality Urban Infra PlaypercysearchNo ratings yet

- Lemelson Capital Wants To Toss Geospace ExecsDocument3 pagesLemelson Capital Wants To Toss Geospace ExecsamvonaNo ratings yet

- Ap 59 PW - 5.06Document18 pagesAp 59 PW - 5.06xxxxxxxxxNo ratings yet