Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Comisión Lancet

Comisión Lancet

Uploaded by

Kaya CromoCopyright:

Available Formats

You might also like

- Wiltshire HRT Guidance 2014Document5 pagesWiltshire HRT Guidance 2014andrewmmwilmot100% (1)

- Genentech Student Worksheet - ResultDocument10 pagesGenentech Student Worksheet - ResultArijit MajiNo ratings yet

- Integration of Oncology and Palliative Care A Lancet OncologyDocument66 pagesIntegration of Oncology and Palliative Care A Lancet Oncologybastosdebora99No ratings yet

- 1 s2.0 S1836955319300803 MainDocument3 pages1 s2.0 S1836955319300803 MainRegina CeballosNo ratings yet

- Frara 2020Document12 pagesFrara 2020anocitora123456789No ratings yet

- 21.policy Palliative CareDocument3 pages21.policy Palliative CareCaio CandidoNo ratings yet

- Journal of Palliative Care & Medicine: Nurses' Knowledge and Practice Toward Gynecologic Oncology Palliative CareDocument6 pagesJournal of Palliative Care & Medicine: Nurses' Knowledge and Practice Toward Gynecologic Oncology Palliative CareNindi MuthoharNo ratings yet

- European Definition of Family MedicineDocument35 pagesEuropean Definition of Family MedicineAqsha AzharyNo ratings yet

- Oncology Nursing Trends and Issues 1Document8 pagesOncology Nursing Trends and Issues 1DaichiNo ratings yet

- Jaoa 2019 053Document10 pagesJaoa 2019 053MordjNo ratings yet

- General Practice and The Community Research On Health Service Quality Improvements and Training Selected Abstracts From The EGPRN Meeting in VigoDocument10 pagesGeneral Practice and The Community Research On Health Service Quality Improvements and Training Selected Abstracts From The EGPRN Meeting in VigoGrupo de PesquisaNo ratings yet

- Proposal First Draft 03.02.2019Document35 pagesProposal First Draft 03.02.2019Hammoda Abu-odah100% (1)

- Abordaje Clinico 2Document37 pagesAbordaje Clinico 2Samuel Monrroy CervantesNo ratings yet

- Demetzos Et Al., 2016Document4 pagesDemetzos Et Al., 2016manoscharNo ratings yet

- Manejo Perioperatorio en El Cáncer de Ovario ESGO 2021Document145 pagesManejo Perioperatorio en El Cáncer de Ovario ESGO 2021Daniel La Concha RodriguezNo ratings yet

- Avaliacao Rede CP EspanhaDocument12 pagesAvaliacao Rede CP EspanhaJoana Brazão CachuloNo ratings yet

- 3821Document3 pages3821WarangkanaNo ratings yet

- Article ReviewDocument3 pagesArticle ReviewElena Cariño De GuzmanNo ratings yet

- Annalsofoncology Resumo Munique 2018Document2 pagesAnnalsofoncology Resumo Munique 2018Fatima AlchadlaouiNo ratings yet

- Protecting The Next Generation of Europeans Against Liver Disease ComplicationsDocument56 pagesProtecting The Next Generation of Europeans Against Liver Disease ComplicationsGustavoJPereiraSNo ratings yet

- Definisi DK Eropa-WoncaDocument32 pagesDefinisi DK Eropa-WoncaHanif Alienda WardhaniNo ratings yet

- Cuidado de SOporteDocument6 pagesCuidado de SOporteMIGUEL MORENONo ratings yet

- Main 6Document8 pagesMain 6Nitin SharmaNo ratings yet

- spb46 MedResEuropeDocument20 pagesspb46 MedResEuropeمصطفى محمودNo ratings yet

- Correspondence: Overcoming Fragmentation of Health Research in Europe: Lessons From COVID-19Document2 pagesCorrespondence: Overcoming Fragmentation of Health Research in Europe: Lessons From COVID-19kayegi8666No ratings yet

- 2020, JCO - disseminationandImplementationofPalliative CareinOncologyDocument8 pages2020, JCO - disseminationandImplementationofPalliative CareinOncologycharmyshkuNo ratings yet

- Role of Geriatric Oncologists in Optimizing Care of Urological Oncology PatientsDocument10 pagesRole of Geriatric Oncologists in Optimizing Care of Urological Oncology PatientsrocioNo ratings yet

- Assessment of Nurses' Knowledge, Attitude, Practice and Associated Factors Towards Palliative Care: in The Case of Amhara Region HospitalsDocument15 pagesAssessment of Nurses' Knowledge, Attitude, Practice and Associated Factors Towards Palliative Care: in The Case of Amhara Region HospitalsjetendraNo ratings yet

- A New International Framwork - Human RightDocument9 pagesA New International Framwork - Human RightHrund HelgadóttirNo ratings yet

- International Journal of Pharmacy Practice AbstractsDocument40 pagesInternational Journal of Pharmacy Practice AbstractsFabiola NogaNo ratings yet

- Septian Reva Yanti - 1041921018 - Review Jurnal FarmakoekonomiDocument15 pagesSeptian Reva Yanti - 1041921018 - Review Jurnal Farmakoekonomiseptian revaNo ratings yet

- Conroy 2013Document6 pagesConroy 2013Pilar Diaz VasquezNo ratings yet

- 7 PubmedDocument12 pages7 PubmedNydia Isabel Ruiz AntonioNo ratings yet

- SdarticleDocument8 pagesSdarticlePao ItzuryNo ratings yet

- DICE Roadmap Colorectal Cancer Europe FINALDocument53 pagesDICE Roadmap Colorectal Cancer Europe FINALHuy Trần ThiệnNo ratings yet

- 182 604 1 PBDocument10 pages182 604 1 PBAngel Nikiyuluw100% (1)

- Comprehensive Geriatric Assessment: British Journal of Hospital Medicine (London, England: 2005) August 2014Document5 pagesComprehensive Geriatric Assessment: British Journal of Hospital Medicine (London, England: 2005) August 2014FadhilannisaNo ratings yet

- Journal of Clinical Nursing - 2018 - Tuominen - Effectiveness of Nursing Interventions Among Patients With Cancer AnDocument19 pagesJournal of Clinical Nursing - 2018 - Tuominen - Effectiveness of Nursing Interventions Among Patients With Cancer AnThu ThảoNo ratings yet

- IT-supported Integrated Care Pathways For Diabetes: A Compilation and Review of Good PracticesDocument15 pagesIT-supported Integrated Care Pathways For Diabetes: A Compilation and Review of Good PracticesKenny BellodasNo ratings yet

- Principles of Haemophilia Care: The Asia-Pacific PerspectiveDocument10 pagesPrinciples of Haemophilia Care: The Asia-Pacific PerspectiveAnindya aninNo ratings yet

- International Journal of Nursing StudiesDocument9 pagesInternational Journal of Nursing Studiesdwi vaniNo ratings yet

- End of Life Care DissertationDocument8 pagesEnd of Life Care DissertationCustomCollegePapersMadison100% (1)

- Heliyon: O.S. Ayanlade, T.O. Oyebisi, B.A. KolawoleDocument10 pagesHeliyon: O.S. Ayanlade, T.O. Oyebisi, B.A. KolawoleCameliaNo ratings yet

- 1 s2.0 S0923753419346502 Main PDFDocument7 pages1 s2.0 S0923753419346502 Main PDFCarlosNo ratings yet

- Running A Colorectal Surgery ServiceDocument21 pagesRunning A Colorectal Surgery ServicebloodsphereNo ratings yet

- UntitledDocument15 pagesUntitledMARTIN DANIEL COLMENAREZ RODRIGUEZNo ratings yet

- 11 3 23 Tonya Project Themes PapenotesDocument32 pages11 3 23 Tonya Project Themes PapenotesGeoffrey OdhiamboNo ratings yet

- ESGOESTROESP Guidelines For The Management of Patients With Cervical Cancer - Update 2023Document32 pagesESGOESTROESP Guidelines For The Management of Patients With Cervical Cancer - Update 2023Limbert Rodríguez TiconaNo ratings yet

- Breast CancerDocument12 pagesBreast CancerSherly RositaNo ratings yet

- Atow 502 00Document9 pagesAtow 502 00hnzzn2bymdNo ratings yet

- Oncology NursingDocument6 pagesOncology NursingHonora Lisset Neri DionicioNo ratings yet

- Nudge and Missed Apointments-2015Document8 pagesNudge and Missed Apointments-2015cjbae22No ratings yet

- Nursing Care For Stroke Patients: A Survey of Current Practice in Eleven European CountriesDocument22 pagesNursing Care For Stroke Patients: A Survey of Current Practice in Eleven European CountriesSiti Ariatus AyinaNo ratings yet

- 2 PBDocument19 pages2 PBPralhad TalavanekarNo ratings yet

- Priorities of Nursing ResearchDocument37 pagesPriorities of Nursing ResearchJisna AlbyNo ratings yet

- Hand in Hand - A Multistakeholder Approach For Co-Production ofDocument2 pagesHand in Hand - A Multistakeholder Approach For Co-Production ofGustavo BritoNo ratings yet

- Patient-Clinician CommunicationDocument17 pagesPatient-Clinician CommunicationFreakyRustlee LeoragNo ratings yet

- Radiotherapy Seizing The Opportunity in Cancer CareDocument16 pagesRadiotherapy Seizing The Opportunity in Cancer CareAlinaNo ratings yet

- Review: Search Strategy and Selection CriteriaDocument13 pagesReview: Search Strategy and Selection CriteriaWindiGameliNo ratings yet

- Patient-Reported Outcome Measures and Health Informatics.: ArticleDocument24 pagesPatient-Reported Outcome Measures and Health Informatics.: ArticleValerie LascauxNo ratings yet

- Management of Peritoneal Metastases- Cytoreductive Surgery, HIPEC and BeyondFrom EverandManagement of Peritoneal Metastases- Cytoreductive Surgery, HIPEC and BeyondAditi BhattNo ratings yet

- Endometrial CancerDocument192 pagesEndometrial CancerAbhishek VijayakumarNo ratings yet

- Rianti Soediro Suryo Tumor & Reconstruction Unit Cicendo Eye Hospital BandungDocument55 pagesRianti Soediro Suryo Tumor & Reconstruction Unit Cicendo Eye Hospital BandungyantiNo ratings yet

- 500 Medical Surgical Sample QuestionDocument323 pages500 Medical Surgical Sample QuestionElizabella Henrietta TanaquilNo ratings yet

- University of Miami Division or Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery Position Paper On Drug Induced Osteonecrosis of The Jaws 2014Document26 pagesUniversity of Miami Division or Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery Position Paper On Drug Induced Osteonecrosis of The Jaws 2014Deb SNo ratings yet

- 473-Article Text-903-1-10-20181112Document122 pages473-Article Text-903-1-10-20181112unaiza100% (1)

- Appendigeal TumoursDocument3 pagesAppendigeal TumourspritanuNo ratings yet

- C. Andrew L. Bassett - Beneficial Effects of Electromagnetic FieldsDocument7 pagesC. Andrew L. Bassett - Beneficial Effects of Electromagnetic FieldsDsgmmmmNo ratings yet

- Decade Report Full Report Final-LinkedDocument250 pagesDecade Report Full Report Final-LinkedJosh Arno M SilitongaNo ratings yet

- Immulite and Immulite 2000 Reference Range Compendium: First English EditionDocument76 pagesImmulite and Immulite 2000 Reference Range Compendium: First English EditiondonpuriNo ratings yet

- Primary Multiple Skin MelanomasDocument8 pagesPrimary Multiple Skin MelanomasCentral Asian StudiesNo ratings yet

- Reiki Science & ResearchDocument21 pagesReiki Science & ResearchGiritharanNaiduEsparanNo ratings yet

- Bromelain A Potential Bioactive Compound: A Comprehensive Overview From A Pharmacological PerspectiveDocument26 pagesBromelain A Potential Bioactive Compound: A Comprehensive Overview From A Pharmacological PerspectiveMehdi BnsNo ratings yet

- CRS and HIPEC in Patients With PC - Yang Et Al. Jgo-2019 PDFDocument15 pagesCRS and HIPEC in Patients With PC - Yang Et Al. Jgo-2019 PDFDiego EskinaziNo ratings yet

- ESMO Follicular LymphomaDocument11 pagesESMO Follicular LymphomaRonald WiradirnataNo ratings yet

- Lower Urinary Tract CancerDocument18 pagesLower Urinary Tract CancerFábio RanyeriNo ratings yet

- Wa0004.Document20 pagesWa0004.Mayra AlejandraNo ratings yet

- TUMORDocument13 pagesTUMORGabrielle Joyce TagalaNo ratings yet

- Histopathological Description of Testis Carcinoma and Therapy in Patients at Dr. Hasan Sadikin General Hospital During 2017-2020 REV 31 - 08Document15 pagesHistopathological Description of Testis Carcinoma and Therapy in Patients at Dr. Hasan Sadikin General Hospital During 2017-2020 REV 31 - 08Titus RheinhardoNo ratings yet

- (GYNE) Ovarian Neoplasms-Dr. Delos Reyes (MRA)Document9 pages(GYNE) Ovarian Neoplasms-Dr. Delos Reyes (MRA)adrian kristopher dela cruzNo ratings yet

- Differentiated Thyroid Cancer: How Do Current Practice Guidelines Affect Management?Document8 pagesDifferentiated Thyroid Cancer: How Do Current Practice Guidelines Affect Management?wafasahilahNo ratings yet

- Ancient Indian ChemistryDocument45 pagesAncient Indian ChemistryPravin Tandel100% (1)

- A Lexicon For Endoscopic Adverse Events: Report of An ASGE WorkshopDocument9 pagesA Lexicon For Endoscopic Adverse Events: Report of An ASGE WorkshopResci Angelli Rizada-NolascoNo ratings yet

- Lab Manual Oral PathologyDocument48 pagesLab Manual Oral PathologyAmr KhattabNo ratings yet

- Fake Cosmetics Product Effects On HealthDocument5 pagesFake Cosmetics Product Effects On Healthdiana ramzi50% (2)

- Cause and Effect Relationship General Principles in Detecting Causal Relations and Mills CanonsDocument8 pagesCause and Effect Relationship General Principles in Detecting Causal Relations and Mills CanonsVidya Nagaraj Manibettu0% (1)

- Herbal Therapy in CancerDocument11 pagesHerbal Therapy in CancerLouisette AgapeNo ratings yet

- Week 1 Health Determinents 122Document27 pagesWeek 1 Health Determinents 122maureen njeruNo ratings yet

- AXA Client Info Sheet - TemplateDocument7 pagesAXA Client Info Sheet - TemplateJayson YuzonNo ratings yet

Comisión Lancet

Comisión Lancet

Uploaded by

Kaya CromoOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Comisión Lancet

Comisión Lancet

Uploaded by

Kaya CromoCopyright:

Available Formats

Lancet Oncology Commission

Integration of oncology and palliative care: a Lancet Oncology

Commission

Stein Kaasa*, Jon H Loge*, Matti Aapro, Tit Albreht, Rebecca Anderson, Eduardo Bruera, Cinzia Brunelli, Augusto Caraceni, Andrés Cervantes,

David C Currow, Luc Deliens, Marie Fallon, Xavier Gómez-Batiste, Kjersti S Grotmol, Breffni Hannon, Dagny F Haugen, Irene J Higginson,

Marianne J Hjermstad, David Hui, Karin Jordan, Geana P Kurita, Philip J Larkin, Guido Miccinesi, Friedemann Nauck, Rade Pribakovic, Gary Rodin,

Per Sjøgren, Patrick Stone, Camilla Zimmermann, Tonje Lundeby

Full integration of oncology and palliative care relies on the specific knowledge and skills of two modes of care: the Lancet Oncol 2018

tumour-directed approach, the main focus of which is on treating the disease; and the host-directed approach, which Published Online

focuses on the patient with the disease. This Commission addresses how to combine these two paradigms to achieve October 18, 2018

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/

the best outcome of patient care. Randomised clinical trials on integration of oncology and palliative care point to S1470-2045(18)30415-7

health gains: improved survival and symptom control, less anxiety and depression, reduced use of futile chemotherapy

See Online/Comment

at the end of life, improved family satisfaction and quality of life, and improved use of health-care resources. Early http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/

delivery of patient-directed care by specialist palliative care teams alongside tumour-directed treatment promotes S1470-2045(18)30605-3,

patient-centred care. Systematic assessment and use of patient-reported outcomes and active patient involvement in http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/

S1470-2045(18)30600-4,

the decisions about cancer care result in better symptom control, improved physical and mental health, and better use

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/,

of health-care resources. The absence of international agreements on the content and standards of the organisation, S1470-2045(18)30484-4,

education, and research of palliative care in oncology are major barriers to successful integration. Other barriers http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/

include the common misconception that palliative care is end-of-life care only, stigmatisation of death and dying, and S1470-2045(18)30486-8, and

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/

insufficient infrastructure and funding. The absence of established priorities might also hinder integration more S1470-2045(18)30568-0

widely. This Commission proposes the use of standardised care pathways and multidisciplinary teams to promote

*Contributed equally

integration of oncology and palliative care, and calls for changes at the system level to coordinate the activities of

European Palliative Care

professionals, and for the development and implementation of new and improved education programmes, with the Research Centre, Department

overall goal of improving patient care. Integration raises new research questions, all of which contribute to improved of Oncology, Oslo University

clinical care. When and how should palliative care be delivered? What is the optimal model for integrated care? What Hospital and Institute of

Clinical Medicine, University of

is the biological and clinical effect of living with advanced cancer for years after diagnosis? Successful integration

Oslo, Oslo, Norway

must challenge the dualistic perspective of either the tumour or the host, and instead focus on a merged approach (Prof S Kaasa PhD,

that places the patient’s perspective at the centre. To succeed, integration must be anchored by management and Prof J H Loge PhD,

policy makers at all levels of health care, followed by adequate resource allocation, a willingness to prioritise goals and T Lundeby PhD,

M J Hjermstad PhD); Institute of

needs, and sustained enthusiasm to help generate support for better integration. This integrated model must be

Basic Medical Sciences, Faculty

reflected in international and national cancer plans, and be followed by developments of new care models, education of Medicine, University of Oslo,

and research programmes, all of which should be adapted to the specific cultural contexts within which they are Oslo, Norway (Prof J H Loge);

situated. Patient-centred care should be an integrated part of oncology care independent of patient prognosis and Genolier Cancer Centre,

Clinique de Genolier, Genolier,

treatment intention. To achieve this goal it must be based on changes in professional cultures and priorities in

Switzerland (M Aapro MD);

health care. Centre for Health Care

(T Albreht PhD), and Centre for

Introduction families. Now, for the most part, oncological and Promotion and Prevention

Programme Management

The overall aim of this Commission is to show why and palliative care cultures are still separate.

(R Pribakovic MD), National

how palliative care can be integrated with oncology for Research on integrating oncology and palliative care is Institute of Public Health,

adults with cancer, irrespective of treatment intention, heterogeneous. Almost all studies have been done Ljubljana, Slovenia; Marie Curie

in high-income and middle-income countries. This in high-income countries, but the variation across Palliative Care Research

Department, Division of

integration will combine two main paradigms, tumour countries, systems, and settings often limits the gener Psychiatry, University College

directed and patient (host) directed, through the use of alisability of findings. The 2018 Lancet Commission London, London, UK

the most effective and optimal resources from oncology report on palliative care focusing on low-income and (R Anderson MSc,

and palliative care in well-planned, patient-centred care middle-income countries stated, “Poor people in all Prof P Stone MD); Department

of Palliative, Rehabilitation

pathways. parts of the world live and die with little or no palliative and Integrative Medicine,

The two paradigms might be understood to be care or pain relief.”1 That Commission gave a series of University of Texas MD

representing two different cultures. Oncology has roots recommendations, such as how to quantify serious Anderson Cancer Center,

in mainstream medicine (ie, internal medicine), and is health-related suffering, and proposes an Essential Houston, TX, USA

(Prof E Bruera MD, D Hui MD);

primarily based on the acute care model. From the mid Package of palliative care, which might also be relevant Palliative Care, Pain Therapy

1960s, hospice and palliative care were established to high-income countries as a basic benchmark of and Rehabilitation Unit,

outside the main health-care systems, often financed by successful implementation at the patient level. Their Fondazione IRCCS Istituto

charities. At the time, the primary focus of palliative previous Commission also recommended international Nazionale dei Tumori di Milan,

Milan, Italy (C Brunelli PhD,

care was end-of-life care, with care provided by and collective action to receive universal coverage of Prof A Caraceni MD);

multidisciplinary teams working with patients and their palliative care and pain relief, and better evidence and

www.thelancet.com/oncology Published online October 18, 2018 http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S1470-2045(18)30415-7 1

The Lancet Oncology Commission

Department of Medical priority-setting tools to measure the global need for one or the other,7 and neither ESMO nor ASCO

Oncology, Biomedical Research palliative care and implementation policies. Given the differentiate between the content of supportive care and

Institute INCLIVA, CiberOnc,

University of Valencia,

empirical basis presented in the 2018 Lancet palliative care. Despite a similar focus, the starting points

Valencia, Spain Commission, the recommendations are primarily for palliative and supportive care differ; whereas palliative

(Prof A Cervantes PhD); focused on high-income countries, but the findings, care started as end-of-life care, supportive care initially

IMPACCT, Faculty of Health, experiences, and models presented might be highly focused side-effects of anticancer treatment, such as

University of Technology

Sydney, Sydney, NSW, Australia

relevant to other contexts as well. chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting, and

(Prof D C Currow PhD); Wolfson The WHO definition of palliative care states that the neutropenia. The overall goal of palliative care is to

Palliative Care Research Centre, competence, attitudes, and skills of palliative care should improve the patient’s quality of life congruent with the

Hull York Medical School, be integrated in health care in general and in cancer care, patient’s preferences—ie, the patient (host)-centred

University of Hull, Hull, UK

(Prof D C Currow); End-of-Life

“Palliative care is an approach that improves the quality perspective. Thus, improve ment of function, optimal

Care Research Group, Vrije of life of patients and their families facing the problem symptom management, mobilisation of resources and

Universiteit Brussel and Ghent associated with life-threatening illness, and is applicable active involvement of patient and family throughout the

University, Brussels, Belgium early in the course of the illness, in conjunction with care process are key components. This improvement can

(Prof L Deliens PhD);

Department of Medical

other therapies that are intended to prolong life.”2 The be achieved by an integration of oncology and palliative

Oncology, Ghent University present paper accepts, but builds on this definition, care guided by the patient’s needs

Hospital, Ghent, Belgium which differs substantially from the common perception Symptom management is a key element of both

(Prof L Deliens); Institute of

of palliative care as being synonymous with end-of-life supportive and palliative care. Symptoms inform

Genetics and Molecular

Medicine, University of care. diagnosis and treatment in all parts of medicine, and

Edinburgh, Edinburgh, UK Hospital-based specialised palliative care alongside play a central role throughout the disease trajectory. They

(Prof M Fallon MD); WHO tumour-directed and life-prolonging treatment has been are a particular focus in palliative care, in that symptom

Collaborating Center for

shown to contribute to better oncology care for patients alleviation is the main target for interventions.2 Symptom

Palliative Care Public Health

Programs, Catalan Institute of and families, in terms of better symptom management, assessment is often not done systematically in oncology

Oncology, University of quality of life, satisfaction with care, and less psycho practice or not routinely incorporated into the clinical

Vic/Central Catalonia, logical distress; some studies even suggest survival decision-making processes.

Barcelona, Spain

benefits.3–5 Thus, we think it is timely to rethink and WHO defines integrated health services as “the

(Prof X Gómez-Batiste PhD);

Regional Advisory Unit for reorganise the delivery of oncology and palliative care to organization and management of health services, so that

Palliative Care, Department of improve treatment and promote collaboration at the people get the care they need, when they need it, in ways

Oncology, Oslo University appropriate levels of care. We propose models of that are user-friendly, achieve the desired results and

Hospital, Oslo, Norway

integration that fit the tasks and responsibilities of the promote value for money”.8 In oncology, the multi

(K S Grotmol PhD); Department

of Supportive Care, Princess two main hospital categories—ie, university hospitals disciplinary team approach that combines competence

Margaret Cancer Centre, (tertiary) and local hospitals (secondary), and community and skills in the planning of treatment care has become

University Health Network, health care (primary). standard.9 This approach is an integration of disciplines

Toronto, ON, Canada

(B Hannon MD, Prof G Rodin MD,

Integration of care is a complex intervention based on at the hospital level of care (eg, among surgeons,

Prof C Zimmermann PhD); organisational structure and patient-centred plans. The oncologists, pathologists, radiologists, and specialist

Division of Medical Oncology, use of standardised care pathways (SCPs) is a method or nurses). The multidisciplinary team can include palliative

Department of Medicine planning tool for the implementation of such complex care specialists at any stage of the disease trajectory,

(B Hannon,

Prof C Zimmermann), Institute

processes. The European Pathway Association (EPA) irrespective of whether treatment intention is curative,

of Medical Science defines SCPs as “a complex intervention of the mutual life-prolonging, or palliative. Given the definition of

(Prof G Rodin), and Department decision making and organisation of care processes for a palliative care, interventions provided by palliative care

of Psychiatry (Prof G Rodin, well-defined group of patients during a well-defined have a broad focus and can therefore not be delivered by

Prof C Zimmermann) University

of Toronto, Toronto, ON,

period”. SCPs facilitate transitions within hospitals and a single profession; multiple professions organised in

Canada; Regional Centre of between health-care levels, which should be seamless, to teams are therefore common. The composition of the

Excellence for Palliative Care, ensure the continuity and coordination of care. The teams might vary, depending on local resources and

Western Norway, Haukeland present Commission proposes the use of SCPs as a traditions, and the internal organisation of the teams

University Hospital, Bergen,

Norway (Prof D F Haugen PhD);

method for the integration of oncology and palliative care. might also vary, but multidisciplinarity, which draws on

Cicely Saunders Institute of Supportive care and palliative care focus on the knowledge from different disciplines but stays within

Palliative Care, Policy and patient—the host of the cancer—whereas the primary their boundaries,10 are probably the most common

Rehabilitation, King’s College focus in oncology is on the tumour. During the past internal organisation. The term multidisciplinary teams

London, London, UK

(Prof I J Higginson PhD);

15 years, semantic discussions have been had regarding will therefore be used throughout this Commission.

Department of Medicine, definitions and distinctions between supportive and From a societal, ethical, and political perspective, the

Haematology, Oncology and palliative care. The European Society for Medical escalating costs of health care are a major problem.

Rheumatology, Heidelberg

Oncology (ESMO) states that supportive care should be Although spending on cancer care comprises only 5% of

University Hospital,

Heidelberg, Germany available at any stage of the disease, whereas palliative the overall health-care budget,11 these costs continue to

(Prof K Jordan MD); Palliative care is focused on treatment when cure is no longer rise more rapidly than in other health-care areas.12 The

Research Group, Department of possible.6 The American Society of Clinical Oncology escalating costs can be attributed to the ageing of the

Oncology (G P Kurita PhD,

(ASCO) does not specify a particular time for delivery of population, new and expensive diagnostic and treatment

2 www.thelancet.com/oncology Published online October 18, 2018 http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S1470-2045(18)30415-7

The Lancet Oncology Commission

options, more prolonged survival of patients with mation sharing, including discussion of prognosis and Prof P Sjøgren PhD) and

metastatic disease, and a growing public demand for options for supportive care, are often missing from Multidisciplinary Pain Centre,

Department of

tumour-directed treatment at all stages of the disease. interviews.28 A more patient-centred focus might be Neuroanaesthesiology

The increased complexity and escalating costs also apply enhanced by a multidisciplinary team approach, with (G P Kurita),

to care at the end of life; about a third of the cost of cancer systematic collaboration among team members from Rigshospitalet–Copenhagen

care is spent during the patient’s last year of life.13 different professions within and across levels of care. University Hospital, Denmark;

Department of Clinical

Planning and structure of cancer care and palliative care This implies an empathic approach by health-care Medicine, Faculty of Health

has the potential to reduce costs, especially when the professionals with willingness and skills to assess and and Medical Sciences,

complexity of treatment and care increases.14 understand the patient’s needs. Health-care providers University of Copenhagen,

Evidence-based medicine is the norm in oncology need to understand, accept, communicate, and plan for Copenhagen, Denmark

(Prof P Sjøgren); Centre

practice, but evidence as to when to start and stop home care because most patients want to spend as much Hospitalier Universitaire

anticancer treatment near the end of life has been time as possible at home during their last phase of life. Vaudoise and Institut

scarce.15 The quality and quantity of research in this area Universitaire de Formation et

has been questioned.16,17 This also applies to research on Palliative care and oncology care—development de Recherche en Soins,

University of Lausanne,

the effects of newly registered targeted therapies and over the past four decades Switzerland

immunotherapies. There is little scientific evidence for In this section we briefly outline the developmental and (Prof P J Larkin PhD); Clinical

the effect of chemotherapy in most areas of symptom conceptual issues of relevance to the present focus on Epidemiology Unit,

Oncological Network,

management, including the treatment of pain,18 although integration of oncology and palliative care. For years

Prevention and Research

palliative radiotherapy might be highly effective in that cancer care has been criticised for its disproportionate Institute, Florence, Italy

regard.19 focus on the tumour, compared with attention to the (G Miccinesi MD); Department

It is especially important during the patient’s last year of patient with the cancer. The concept of hospice care, and of Palliative Medicine,

University Medical Center

life that the attention given to the effect of tumour-directed later palliative care, was introduced partly as a reaction to

Göttingen,

treatment is congruent with the individual patient’s the absence of a patient-centred focus. Attention to Georg-August-Universität

perception of benefits, in terms of symptom burden and palliative cancer care emerged in the 1970s, partly Göttingen, Göttingen,

quality of life.20 Few, if any, trials give guidance for such through efforts of researchers such as Jan Stjernswärd, Germany (Prof F Nauck PhD)

choices. This has led to the recommendation that a set of who was attached to WHO at that time.29 The term Correspondence to:

criteria (eg, disease progression, performance status, palliative care was probably first coined by the Canadian Prof Stein Kaasa, European

Palliative Care Research Centre,

nutritional status, weight loss, and symptom burden) surgeon Balfour Mount in 1974.30 At the time, palliative Department of Oncology, Oslo

should guide the discontinuation of tumour-directed care had a strong focus on end-of life-care and it is University Hospital and Institute

treatment.21,22 These criteria could also apply to phase 1 commonly still equated with this timeframe,31 despite its of Clinical Medicine, University of

Oslo, Oslo 0424, Norway

trials, which might have therapeutic intent, but for which subsequent redefinition. A dichotomised perception of

stein.kaasa@medisin.uio.no

the likelihood of benefit to the individual patient might be oncology care and palliative care is outlined in figure 1.

For the European Pathway

extremely small.23 As the disease progresses, the main This perception fits with palliative care as equal to end-of- Association see http://e-p-a.org/

outcomes of treatment should be continually assessed and life care, but is not in line with the present definition of

redefined as they vary from tumour response to symptom palliative care as formulated by WHO (“applicable earlier

control, preservation of function, and wellbeing.24 in the disease trajectory”).2 A perception in line with this

Shared decision-making (SDM) is a key element of definition, in which the two are integrated or given in

cancer care, but the degree to which patients can parallel, is outlined in figure 1.

participate as active partners in the decision-making

process has been questioned, when multiple options for

Traditional palliative care

tumour-directed treatment are available and when life-

prolonging treatment with marginal benefits are offered.25

Some patients want to live as long as possible and are Palliative care to

manage symptoms

willing to try intensive treatment, even if the likelihood of Life-prolonging or curative treatment and improve quality

benefit is extremely small and the risk of side-effects that of life

might impair quality of life and reduce residual time at

home is high.26 Active patient participation presupposes Diagnosis Death

sufficient and relevant knowledge of the disease and

treatment options. This amount of knowledge can only be Early palliative care

reached by the continuous provision of realistic patient-

centred information. To provide this information, good Life-prolonging or curative treatment

communication skills among the oncologists and

palliative care specialists are required, and the needs and

Palliative care to manage symptoms and improve quality of life

wishes of patients and families need to be assessed

systematically and used in the decision-making Diagnosis Death

processes.27 For decision making for phase 1 trials,

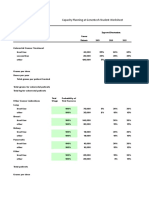

fundamental components of communication and infor Figure 1: Traditional versus early palliative care

www.thelancet.com/oncology Published online October 18, 2018 http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S1470-2045(18)30415-7 3

The Lancet Oncology Commission

Supportive care emerged as a concept and care approach The content and professional competence needed to

in the late 1980s, somewhat later than palliative care, but provide palliative care and supportive care are similar,

with a similar focus on the individual patient with cancer, with both focusing on the host—the patient living with

the host, not the tumour.32 Supportive care focused on the the disease or with side-effects after the treatment, or

entire disease trajectory, including when curative both. Palliative care and supportive care are differently

treatments, often accompanied by multiple side-effects, are organised across locations, on the basis of resources and

still being delivered. Late effects began to receive attention traditions. In some centres, the two are organised as one

during the 1980s as new health problems in cancer care, service, whereas in others they are completely separate.

and spawned the field of cancer survivorship, which can be Independent of organisational structure, the focus on the

regarded as an extension of supportive cancer care.33,34 host with a patient-centred focus is similar. Therefore,

The difference between palliative care and supportive when resources permit, integration of palliative care and

care is primarily related to differences in the stage of supportive care might be most effective in terms of

disease to which they are applied, rather than to the treatment delivery and as a direction to strengthen the

treatment itself.35 This is reflected in the similar patient-centred culture in cancer care delivery.

definitions of the concepts by the US National Cancer WHO’s most recent (2002) definition of palliative care,

Institute (NCI) and WHO.36 According to the WHO revised from its 1989 definition, points to the integration

definition, palliative care focuses on patients with a life- of oncology and palliative care by stating, “Palliative care

limiting disease, whereas supportive care is applicable is applicable early in the course of illness, in conjunction

irrespective of treatment intention and might also include with other therapies that are intended to prolong life,

rehabilitation of cured cancer survivors. Therefore, in such as chemotherapy or radiation therapy, and includes

our view, treatments of pain, fatigue, physical, and those investigations needed to better understand and

psychological distress after curative treatment are best manage distressing clinical complications.”37 The inte

characterised as supportive care. grated care model has also become a topic in cardiology,

pulmonology, and other specialties.

Health-care system

Patients live longer with metastatic disease—the need

for coordination and planning

The possibilities for tumour-directed treatments have

General Local Cancer

practitioner hospital centre increased exponentially during the past decade. Multiple

treatment lines have become the rule for common

cancers, such as breast, lung, colorectal, and prostate

Standardised care pathways

cancer, and many more patients are now living with

metastatic disease. New immune therapies are being

introduced to standard oncology care, with side-effects

that differ from those of traditional chemotherapeutic

Cancer centre

agents. We do not have systematic data on the effect of

these new therapies on the host and their clinical

presentations; however, we do know that the increase in

the number of patients living with advanced disease will

Colonoscopy Imaging Pathology Surgery have implications on coordination and planning of care,

laboratory MRI

and will require the combination of tumour-centred and

the patient-centred approaches.

Standardised care pathways This development has reshaped cancer into a chronic

illness, with WHO recognising cancer as one of four

major chronic diseases in 2010.38 The development has

Department of oncology also made the terms curative and palliative tumour-

directed treatment even more vague and prone to

misunderstanding by patients and possibly some medical

staff. We prefer terms related to treatment intention; ie,

curative, life prolonging, or palliative.39 An increasing

Medical Radiation Cancer

oncology oncology palliative care number of patients with advanced cancer will probably

die from other comorbid diseases after a prolonged

Standardised care pathways period of tumour-directed treatment; thus, the chronic

care model will become increasingly relevant for

oncology–palliative care. However, the traditional disease

model still dominates within cancer care. The chronic

Figure 2: Health care includes silos at different levels care model was launched at the end of the 20th century,

4 www.thelancet.com/oncology Published online October 18, 2018 http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S1470-2045(18)30415-7

The Lancet Oncology Commission

and represents a paradigm shift within health care.40 The

model emphasises patient-centred elements (eg, patient Panel 1: Three levels of integration

empowerment, patient preferences, and family and Linkage

social support)40 and therefore has obvious similarities • Patients are cared for in a planned system

with patient-centredness, although the two seem to have • Based on an understanding of special needs (formalised in

been developed in parallel. a standardised care pathway)

• Work in parallel or in series

Integration in health care • Basic understanding of the various professional skills

The availability of new tumour-directed treatments for

advanced cancer points to a basic challenge in health care Coordination

in general and in cancer care specifically: how can • Patients are cared for in a well-structured plan, on the

complex care pathways be organised in a flexible and basis of patients’ needs and the content of the

optimal structure, involving multiple professionals standardised care pathway

working simultaneously or in parallel? Health care is • Integration operates in separate structures within a

currently most often organised in silos of primary, system (eg, pathology, imaging, surgery, radiation, or

secondary, and tertiary levels of care, with levels within tumour-directed chemotherapy symptom management)

each silo as well. Surgical oncology, medical oncology, • Integration has been an implementation plan

radiation oncology, and palliative care within the cancer (of the standardised care pathway) and follow-ups and

centre are examples of such silos, organised with separate monitoring of the plan

leaders from different departments with individual Full integration

budgets. Patients and their families might experience • Resources (competence and skills of medical staff) are

great difficulty navigating between and within each of pooled into one unit or section, taking from existing

these silos, and understanding mixed messages about systems

the main focus of care presented by two different cultures • Silos are eliminated (partially or totally) and the

within the same department or hospital. As exemplified organisation is based on the standardised care pathway

in figure 2, these silos should be connected to provide the • The multidisciplinary team meetings can, as a dynamic

varying needs for care of each individual patient. SCPs structure, be an example of full integration as they meet

can be used to foresee, establish, and administer such

Panel adapted from Leutz.42

connections.

In 2007, the WHO Director-General Margaret Chan

stated, “We need a comprehensive, integrated approach

to service delivery. We need to fight fragmentation.”41 The In an influential article, Leutz42 defined integration as

current challenge to service delivery is the specification “the search to connect the health care system with other

of the nature of integrated services in different settings, human service system to improve outcome (clinical,

and the establishment of how integration can contribute satisfaction and efficiency)”. He proposed three levels of

to the intended aim of ensuring that patients with cancer, integration: linkage, coordination, and full integration.

and their families, receive the care they need. The WHO In panel 1, examples and understanding of these three

technical brief8 on the inte gration of health services levels are provided from a general health-care perspective

aimed to show that integrated service delivery is best and from an oncology or palliative care perspective, or

seen as a continuum involving technical discussions both. The levels of integration can be understood as both

about tasks that need to be done to provide good-quality static and dynamic. Integration as outlined in this panel

health. challenge the internal life and individual priorities in

Integration aims to coordinate the activities of cultures and subcultures in both oncology and palliative

professionals, with the overall goal of improving patient care. To reach achievable and practical solutions,

care. The achievement of such coordination requires integration can be formalised and made routine in some

change at the system level on the basis of a common situations (eg, multidisciplinary team meetings as one

understanding and acceptance of the two paradigms in component in a planned structure [SCPs]), or added

this context. From an organisational perspective, the flow according to patient needs to optimise care in other

of patients between levels, or silos, of the organisation situations.

(ie, units, sections, departments, or hospitals) needs to be

taken into account. To reach the goal of integration, a Integration of oncology and palliative care

common understanding of a merging of the two paradigms, The term integration has been applied to the interplay

as well as budgetary reallocations and formal or informal between oncology and palliative care for decades; it

changes in the organisation, are probably needed. These was used by Malin in 2004,43 in an editorial that

changes might allow more flexible allocation of human recommended efforts be made to bridge the gap between

and treatment resources according to the needs defined in oncology and palliative care to provide better care

the SCPs. for those dying from cancer. The distinction between

www.thelancet.com/oncology Published online October 18, 2018 http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S1470-2045(18)30415-7 5

The Lancet Oncology Commission

Jordhøy et al Temel et al Zimmermann Bakitas et al Maltoni et al Temel et al Grønvold et al

(2000)47 (2010)3 et al (2014)5 (2015)48 (2016)49 (2017)50 (2017)51

Clinical structure

Palliative care inpatient consultation team Y Y Y Y ·· Y Y

Palliative care outpatient clinic Y Y Y Y Y Y Y

Community-based care or home palliative care Y ·· Y ·· ·· ·· ··

Clinical processes

Multidisciplinary specialised palliative care team Y Y Y Y Y Y Y

Routine symptom screening in the outpatient ·· ·· ·· ·· ·· ·· ··

oncology clinic

Administration of systemic cancer therapy Y Y Y Y Y Y Y

(eg, chemotherapy and targeted agents) possible

in patients admitted to palliative care service

Follow prespecified palliative care guidelines Y Y ·· ·· Y Y Y

Early referral to palliative care Y Y Y Y Y Y Y

Availability of clinical care pathways (automatic ·· ·· ·· ·· ·· ·· ··

triggers) for palliative care referral

Palliative care team routinely involved in ·· Y ·· ·· ·· ·· ··

multidisciplinary tumour conference for patient

case discussions

Communication, cooperation, and coordination Y Y ·· ·· Y ·· ··

between palliative and oncology service

Routine discussion of prognosis, advance care Y Y Y Y Y Y Y

planning with goals of care

Y=presence of component in trial. Table adapted from Hui and colleagues.44,52

Table 1: Components of integration from seven randomised trials

integration and early integration has not been clearly published reviews of the effectiveness of specialised

defined, but use of early integration might help to palliative care have mainly been based on mixed

counteract the commonly held belief that palliative care populations, without separation of the results for patients

is equivalent to end-of-life care. The strong focus on with cancer. The trials included in the 2017 review were

integration in contemporary oncology and palliative care published between 2001, and 2016, and all used different

has also led to experts formulating consensus-based designs and endpoints. The components of integration

indicators of integration.44 from the seven randomised trials included in the 2017

Temel and colleagues’ findings3 of improved survival review are shown in table 1.44,52

and better quality of life with early palliative care has At the turn of this century, Jordhøy and colleagues47

paved the way for the integration of palliative care in published the results of a cluster-randomised trial of

oncology as a means to provide better and more palliative care. We are not aware of any randomised trials

patient-centred care for patients with a life-limiting on the effects of palliative care programmes before this

cancer. Palliative care has also been proposed as a means publication. Some trials in the 1980s and early 1990s tried

to offset the rapidly increasing costs in oncology, to evaluate the effects of elements included in palliative

especially in the patients’ last year of life, and to address care, such as end-of-life care, with negative results.53–55

the anticipated shortage of resources due to increasing These early trials were hampered by methodological

demands and costs. Temel and colleagues’ study3 led to shortcomings, such as an absence of well-defined primary

the formulation of an ASCO provisional clinical opinion endpoints, control contamination, and problems with the

in 2012,45 which was revised into a clinical practice recruitment processes, and problematic attrition and

guideline in 2017.15 Without using the term early adherence. In their large study47 of mixed cancer diagnoses

integration, the provisional clinical opinion stated using well-validated instruments, Jordhøy and colleagues

palliative care is more than end-of-life care, and that circumvented many of these limitations; however, the main

patients would benefit from receiving palliative care focus of this comprehensive trial was integration of

while still receiving tumour-directed treatment, based on community and hospital care for patients with advanced

a low to medium amount of evidence.45 cancer. More patients died at home in the intervention

The current research on integration of oncology and group, compared with the control group, and these patients

palliative care primarily stems from studies of patients also spent less time in hospitals and more time at home

with cancer in outpatient hospital settings, and this and in nursing homes. No effect on symptom burden was

research has been synthesised in a 2017 review.46 Other shown, which was reported in a separate article.4

6 www.thelancet.com/oncology Published online October 18, 2018 http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S1470-2045(18)30415-7

The Lancet Oncology Commission

Several years later, Bakitas and colleagues56 designed first European trial to confirm the results of the important

ENABLE II, a randomised trial to test a telephone-based North American trials.3,5

psychoeducational palliative care intervention delivered Temel and colleagues’ 2017 study50 again drew attention

concurrent with oncological treatment. The programme to early palliative care by examining the effect of an

was found to significantly improve both mood and quality integrated palliative care model on patients with newly

of life in a sample of 322 patients with mixed cancer diagnosed gastrointestinal (non-colorectal) cancer and

diagnoses. However, a traditional palliative care model patients with lung cancer. In addition to improved quality

was not applied, because the study did not systematically of life and decreased depression, they showed that an

include the intervention of a (multidisciplinary) palliative integrated palliative care model improved the patients’

care team. ability to cope with their prognosis and enhanced their

Temel and colleagues’ study3 is usually referred to as the communication with clinicians about end-of-life

landmark trial of integration of oncology and palliative preferences. They showed that these positive effects vary

care. They showed, among patients with newly diagnosed by cancer types, but the two subsamples were too small

lung cancer, early palliative care not only reduced to substantiate these differences.

depression and symptom burden, and improved quality of The 2017 Danish palliative care trial (DanPaCT)51

life, but also produced a survival benefit. The intervention investigated the effect of a palliative care intervention

group reported improved prognostic awareness and among patients with a range of cancer diagnoses. Patients

received less intensive cancer treatment at the end of life. were included if they scored above a predefined threshold

However, the study was carried out in a highly specialised for self-reported symptoms or reduced functioning.

institution and some researchers have raised doubt as to The primary outcome was defined as the individual

its generalisability to other care settings.57 patient’s main problem, as defined by a screening

In a cluster-randomised trial in 2014, Zimmermann process. The sample was large with little loss to follow-up.

and colleagues5 investigated early involvement of No differences in either primary or secondary outcomes

specialised palliative care in the treatment of patients were reported. Grønvold and colleagues51 proposed

with a wide range of advanced cancers. This study several possible explanations for the absence of beneficial

provided evidence of benefits on quality of life and effects, including the absence of structure in the palliative

symptom burden, and was the first study to explore care visits and short observation time.

clinician-patient interactions, by specifically addressing A 2018 study58 confirmed Temel and colleagues’ 2010

the relationship with health-care providers and patients’ findings;3 however, the intervention was not palliative care

problems in their interactions with nurses and doctors per se, but consisted of monthly sessions with a palliative

(related to information seeking and communication). care nurse and inferred more use of consultations with a

The intervention group was more satisfied with care than psychologist. The study therefore adds to the variability in

the control group, but no differences were found in other the content of the palliative services (ie, the intervention)

measures of patient-staff interactions. and of how palliative care and oncology care are delivered

In the meantime, the initial model constituting in studies of integration of oncology and palliative care,59

ENABLE II had been expanded, and, in 2015, Bakitas and but the added element was patient centred, which is of

colleagues48 published the findings of the ENABLE III particular relevance in this context.

trial. Through the application of a fast-track design, this The growing body of evidence for integration of

trial was the first to evaluate the optimal timing for the oncology and palliative care has been synthesised in

concurrent introduction of palliative care and standard reviews, statements, and guidelines, some of which focus

oncological care.48 The only difference between the specifically on integration and others more generically on

groups was longer 1-year survival for the group who specialised palliative care.15,57,60–62 Several issues complicate

received care early compared with the group who started attempts to evaluate and compile this literature. Most of

palliative care 3 months later. The intervention consisted the reviews underline that the heterogeneity in settings,

of an initial in-person palliative care consultation by a target populations, and study outcomes make it difficult

certified palliative care physician, followed by six to directly compare trials. The diversity in intervention

structured phone coaching sessions by an advanced content and the palliative care-specific component are

practice nurse using standardised curriculum. This type particularly cumbersome (table 1). In addition, the

of intervention raises the question of whether ENABLE III variability in methodological quality across trials was

is a sophisticated psychoeducational model, rather than a highlighted in a 2016 meta-analysis.63 When only trials

specialised palliative care intervention. with low risk of bias were considered, the authors

In 2016, in a multicentre randomised trial, Maltoni and concluded that the evidence for the effectiveness of

colleagues49 evaluated early palliative care efficacy for specialised palliative care interventions for improving

patients with advanced pancreatic cancer through both quality of life and symptom burden is relatively weak.63

patient-reported outcomes and health-care use. They However, a 2017 Cochrane review64 concluded that early

reported benefits in quality of life, symptom burden, and palliative care might have more beneficial effects on

reduced time spent in institutions. As such, this was the quality of life and intensity of symptoms among patients

www.thelancet.com/oncology Published online October 18, 2018 http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S1470-2045(18)30415-7 7

The Lancet Oncology Commission

with advanced cancer than among those given usual or life-prolonging, tumour-directed treatment ceases. The

standard cancer care alone. The effects are of clinical infrequent assessment of symptoms is a major factor

relevance for patients at an advanced disease stage with explaining inadequate symptom relief, with undue

limited prognosis, when further decline in quality of life suffering among patients with cancer who are

is the rule. approaching end of life. A key symptom in health care is

The heterogeneity in study outcomes and metho pain, and, according to the international definition by the

dological quality of studies of the effectiveness of palliative International Association for the Study of Pain,70 pain can

care are obvious limitations in research on integration. only be assessed reliably and validly by self-report, not by

However, although the evidence for integration of observations. Several other symptoms, only assessable by

oncology and palliative care might seem meagre, the patient report (ie, as PROMs), are important to consider

recommendation to integrate is strong because the overall in the care of patients with cancer. These include

picture shows that different kinds of early palliative care psychological symptoms (eg, anxiety and depression)

interventions have a positive effect on various patient and somatic symptoms (eg, anorexia, dyspnoea, fatigue),

outcomes. and overall quality of life.

Traditionally, PROMs were collected through the use of

Systematic symptom assessment paper-based questionnaires. Advances in health infor

To facilitate better patient involvement in cancer care and mation technology have prompted the development of

improved patient-centred outcomes, the patient’s voice electronic tools for the distribution of PROMs. Such tools

must be heard by their medical team during shared allow an effective integration of patient-related data from

decision-making, in terms of symptoms, functions, various sources, and permit follow-up from a distance of

quality of life, and preferences for information provision. patients who are not admitted to hospital or seen in

The recognition of the patients’ perspectives by health- consultations, and can promote data sharing between

care providers as valuable or even decisive when choosing care teams at different care levels. In oncology, electronic

how to care, where to care, and when to care, represents a assessments and rapid presentation of results facilitate

major shift in medicine over the past 10–20 years. communication, are perceived positively by patients and

Patients’ perspectives have now been recognised as valid clinicians, and might result in a more efficient and

outcomes in clinical medicine, as endorsed by the focused use of time.71,72 Further, a 2012 qualitative study73

National Institute of Health consensus conference.65 showed perceived usefulness of an electronic tool might

Although systematic symptom assessment is an be more important than functional aspects such as user-

established core clinical activity in palliative care, directly friendliness and speed to encourage its use. Immediate

derived from the WHO definition, symptom assessment display of easily interpretable results to the health-care

is still rarely done systematic or actively used in the providers is a crucial factor for successful implementation

patient decision-making processes in oncological and of electronic registration of PROMs into the clinics.74

palliative care practices. On the basis of this background information, we find it

In 2006, the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) pertinent to point to a 2016 study75 on the effects of

proposed the term patient-reported outcomes measures systematic symptom assessment by tablet computers in

(PROMs) for all measures that can best, or only, be patients with advanced solid tumours. The study showed

assessed by asking the patients themselves.66 By that, the positive outcomes of systematic symptom assessment in

FDA also formally recognised the importance and oncology practice, and that health-related quality of life

clinical utility of PROMs by releasing a new guideline for improved among the intervention group and worsened

industry on these issues. PROMs are therefore an among those receiving usual care. In a separate letter,76

umbrella term covering the patient’s perspective on the authors showed improved survival among those who

physical and psychological wellbeing, and symptoms and had their symptoms assessed systematically. The results

treatment effects.67 The recognition of PROMs as of this trial are a strong reminder of the importance and

independent outcomes in cancer68,69 is consolidated by positive effects of systematic symptom assessment in

the CONSORT-PRO extension statement69 developed to cancer care in general.

improve the reporting of PROMs on patients’ evaluation

of symptoms, functioning, and quality of life. Because Standardised care pathways

the patient is the primary source of information, PROMs Integrated care models can be understood as organ

supplement clinical observations and objective findings isational methods to solve the challenges of management

with individual patient information. of complex care processes, and particularly so in the

Symptom assessment tools are, for these reasons, growing elderly population. In integrated care, profes

grouped under the umbrella PROMs, which also encom sionals with different competencies and from distinct

passes other outcomes assessed similarly, such as quality organisations work together in complex and formalised

of life and functional status. Symptom assessment is structures. This model challenges the traditional vertical

pivotal for palliative care and supportive care efforts organisation of health care, as outlined earlier, structured

throughout the disease trajectory, and increasingly so as in pillars or silos.

8 www.thelancet.com/oncology Published online October 18, 2018 http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S1470-2045(18)30415-7

The Lancet Oncology Commission

Patients often experience gaps between services when were monitored in the SCP group through the use of

they must shift to a new level of care or specialisation.77 computer technology.82 A main feature of the included

A different matrix is hypothesised to better meet the trials was that the SCP was applied in a facility-specific

patient’s needs, which are complex and shifting over manner for a defined period of time, disregarding other

time, and to allow the patient to move between care levels elements involved in patient care and follow-up. Because

or specialisations in way that is more predictable and the SCPs tested were mainly paper based, the potential

transparent to the patient and to their care providers. For utility of a common and flexible electronic SCP was not

this to occur, communication and collaboration among evaluated. The way in which different SCPs were audited

the health-care providers must also be predictable and was also highly variable.81

clearly understood, with the roles of team members

clarified and agreed on. Conclusions

The achievement of integration among the different There is now a strong consensus for integration of

services and levels of health care is by no means oncology and palliative care in contemporary cancer care.

straightforward, because two different cultures with The newly released ASCO guidelines on the topic were,

different foci—ie, the tumour-centred and patient- for months, the most searched article in the Journal of

centred pathways—need to join forces and attend to the Clinical Oncology.15 The published randomised trials on

patient’s needs during the development and imple the subject point to health gains resulting from

mentation of the SCPs. Indeed, the greater the number integration, but what, when, and how to integrate are yet

of actors involved in a patient’s care, the more difficult to be established. Despite clear recommendations for

the communication and coordination. The development integration, this Commission has not identified any

of SCPs is a method for meeting these challenges. health-care system where the content and the constructs

With roots in the automobile and production of integration are implemented. This Commission will

industries, multiple SCPs have been developed and work on the assumption that broad implementation

published over the past 5 years, covering a wide area of plans are needed, adapted to national, regional, and local

health services, ranging from surgical procedures to organisations of oncology and palliative care, as well as

complex disease trajectories.78 Implementation of SCPs the culture of the organisation. Local variations, in terms

ensures care is organised with the right people, at the of resources and practices, also probably play a role.

right time, in the right place. Therefore, SCPs can work By acknowledging integration of oncology and palliative

as a systematic way to organise integration in the or care as a complex process including different parts of the

ganisation to improve patient care and resource use; health-care system, both horizontally and vertically, and

however, such organisation requires the possibility of involving the patient, we propose SCPs as a means by

seamless patient flow in a customised organisational which future efforts could promote integration. For the

model. same reasons, this Commission will address integration

A wide range of methods have been used in the in different sections. Each section will address different

development of SCPs, mainly without a common aspects of integration, ranging from how to focus on the

framework or international consensus on how to develop patient, to societal changes and new research areas.

them in a standardised and evidence-based way.79,80 The This Commission is an international collaboration

generalisability of findings is also limited by the plethora between 30 experts in oncology, palliative care, public

of study designs, settings, and proposed pathways. This health, and psycho-oncology. In October 2016, a kick-off

situation makes the relevance of individual studies meeting was held in Milan, Italy, where panel leaders

difficult to evaluate and apply to clinical settings that are were appointed, the structure of the commission was

different from the one in which the specific SCP was decided, and a plan for the work was agreed on. During

developed and tested.81 In their review, Rotter and the 2 years that followed, each panel was expanded with

colleagues 7 assessed the effects of SCPs on professional experts within the relevant field, topical literature

practice, patient outcomes, and hospital costs. They searches were done, and experts participated in an

included 19 randomised trials comparing SCPs to interactive writing process. Both administrative and

standard practice, based on more than 3000 abstracts academic organisations were run, from Norway, by

identified in their search, covering a wide range of Stein Kaasa, Jon Håvard Loge, and Tonje Lundeby.

medical conditions and surgical procedures. Of the

included trials, nine gave some description of how the Policy—challenges and frameworks

SCP was developed and implemented. In those nine Demographic data show cancer incidence and prevalence

studies, the method applied to develop an SCP was are rapidly increasing, and that the population is ageing

mainly described in general terms—eg, a protocol was with multiple chronic comorbidities. A 2014 study83

developed by a multiprofessional team. Ten studies did a presenting various models for extrapolation in high-

follow-up on how health-care providers complied with income countries found that 69–82% of those who die

the SCP protocol, but none were done in a similar way. need palliative care. Consequently, an augmented need

Only one trial described how relevant clinical outcomes for palliative care at all health-care levels is expected.

www.thelancet.com/oncology Published online October 18, 2018 http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S1470-2045(18)30415-7 9

The Lancet Oncology Commission

Palliative care has been identified as an integrated part of Bismarck systems. Although the Beveridge system

the cancer care pathways by professional international seems to perform better in terms of care coordination

organisations such as ASCO, ESMO, and the European because health and social care are integrated in a

Association for Palliative Care (EAPC), but also by EU common welfare stem, this might only be the case at the

projects such as the European Partnership Against governmental level. In the Bismarck system, social and

Cancer.60,84–86 In sum, these statements indicate that other types of care (related to health but not necessarily

palliative care should be part of national cancer politics and inherent in health care) show a large degree of fragmen

plans.87 How this can be accomplished in present national tation because they are financed from different sources,

politics in Europe will be addressed in the following often as cash benefits or entitlements.

sections, where examples of different practices in At the 2011 conference for the Organisation for

organisation of palliative care in some European countries Economic Co-operation and Development,91 the sharp

and recommendations for future politics are given. distinction between these two systems was described as

mainly of historical interest, and the pure Bismarckian

Organisation and development of health policies and era as more or less over, because policies emphasised

systems universal coverage rather than a right of labour.

Health-care systems in Europe are generally classified with Furthermore, little, if any, scientific evidence for the

respect to the role of the state, health-care providers, and superiority of one system over the other exists, specifically

payers. This triad is furthermore amended by closer or regarding coordination of care, for which no universal

looser links with the social care sector. Countries with a definition presently exists.92 Palliative care has been

strong national health service tend to have closer links internationally acknowledged through a resolution by the

between health care and other sectors, including the social World Health Assembly.93

care sector. Health-care systems based on social health In Europe, the EAPC has, since its foundation, been

insurance systems have a looser link with the social care scientifically, clinically, socially, and politically influential

sector and, consequently, more often have gaps in the in the promotion, advocacy, and development of palliative

comprehensiveness and continuity of care. The type of care in Europe. In 2010, the EAPC launched the Prague

system is very relevant to palliative care, because the health charter,84 stating that access to palliative care is a legal

and social sectors often need to interact flexibly and quickly obligation and a human right, and thus beyond the

to meet the needs of the patient and family. established palliative care community. This charter was

Modern health-care systems in Europe build on the followed by the Lisbon challenge,94 identifying four major

experiences of the 20th century, when the state’s objectives related to access to essential medicines,

responsibility for delivery of health care became a social development of health policies that address the needs of

and political issue. This responsibility was primarily patients with life-limiting or terminal illnesses, adequate

approached in three different ways: the Bismarck palliative care training at undergraduate levels for health-

system,88 the Beveridge system,89 and the Semashko care providers, and a structured implementation of

system.90 The oldest of these systems, the social health palliative care. In 2013, the Budapest commitments

insurance system (Bismarck system), originated in presented frameworks for palliative care development as

1883.88 The coverage was gradually extended from a joint initiative by EAPC, the International Association

industrial workers to other categories of the workforce. for Hospice and Palliative Care (IAHPC),95 and the

In the 1940s, Lord Beveridge led the work on the Worldwide Palliative Care Alliance (WPCA).96 Key

development of the UK’s National Health Service,89 elements were policy, availability, education, and quality.97

which became a more comprehensive response to the In 2006, the European Palliative Care Research

demands for full coverage, irrespective of employment Collaborative (EPCRC) was the first palliative care

status (Beveridge system). Between these two systems is research project that received funding from the European

the Semashko system,90 which was developed in the Commission under the 6th framework programme for

1920s by the Soviet Union to deal with the organisational research. The promotion and financing of palliative care

aspects of health care, rather than financing or research within the EU framework was a major step

entitlements. forward for European palliative care research. Since then,

The main differences between the Beveridge and several high-quality projects on oncology and palliative

Bismarck systems are the degree of state control over care have received funding—eg, the IMPACT project, for

health care and how this control is exerted. In the the development and testing of quality indicators for

Beveridge system, the ministry of health is typically the dementia and cancer palliative care;98 EUROIMPACT,99 a

budget holder and therefore commissioning services multiprofessional research training programme; and,

through a network of health-care providers. In the the International Place of Death Study.100

Bismarck-type systems, budgets are predominantly with The objectives of the EU-funded PRISMA project

health insurance companies, regulated by the ministry of (7th Framework Programme) were to coordinate research

health and operating in public interest. The role of the priorities, measurement, and practice in end-of-life care

different partners has significantly more weight in in nine countries across Europe, resulting from an

10 www.thelancet.com/oncology Published online October 18, 2018 http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S1470-2045(18)30415-7

The Lancet Oncology Commission

identified need for high-quality palliative and end-of-life

Hospitals Outpatient Nursing homes Hospices Home care

care and research. The research agenda and subsequent clinic or day (and homes for

guidance should reflect the European cultural diversity care centres the elderly)

and be informed by public and clinical priorities.101 Belgium107 Y, PCU Y Y N Y

Consensus was reached on the following priorities for Bulgaria108 Y, including CCC N Y Y Y

end-of-life cancer care research in Europe: sympto and PCU

matology, issues related to care of the dying, policy and Denmark109 Y, including PCU N Y Y Y

organisation of services, and moving from descriptive to France110 Y, including PCU Y N N Y, including hospital

interventional studies.102 at home programme

Two EU-funded projects also addressing European Netherlands111 Y Y Y, including PCU Y Y

cancer politics have now come to an end: the European Norway112,113 Y Y Y N Y

Partnership on Action Against Cancer (EPAAC)103 and Slovenia114,115 Y Y N Y Y

the European Guide for Quality National Cancer Control Spain116,117 Y Y N N Y

Programs (CANCON).87 The EPAAC report on National