Professional Documents

Culture Documents

String Student

String Student

Uploaded by

silacanCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

String Student

String Student

Uploaded by

silacanCopyright:

Available Formats

595611

research-article2015

JRMXXX10.1177/0022429415595611Journal of Research in Music EducationHewitt

Article

Journal of Research in Music Education

2015, Vol. 63(3) 298–313

Self-Efficacy, Self-Evaluation, © National Association for

Music Education 2015

and Music Performance Reprints and permissions:

sagepub.com/journalsPermissions.nav

of Secondary-Level Band DOI: 10.1177/0022429415595611

jrme.sagepub.com

Students

Michael P. Hewitt1

Abstract

In the present study, relationships between two components of self-regulation

(self-efficacy and self-evaluation) and gender, school level, instrument family, and

music performance were examined. Participants were 340 middle and high school

band students who participated in one of two summer music camps or who were

members of a private middle school band program. Students indicated their level of

self-efficacy for playing a musical excerpt before performing it and then self-evaluated

their performance immediately afterward. Findings suggest that there is a strong

and positive relationship between self-efficacy and both music performance and self-

evaluation. There was also a strong negative relationship between self-evaluation

calibration bias and music performance, indicating that as music performance ability

increased, students were more underconfident in their self-evaluations. Gender

differences were found for self-evaluation calibration accuracy, as female students

were more accurate than males at evaluating their performances. Middle school males

were more inclined than females to overrate their self-efficacy and self-evaluation

as compared to their actual music performance scores. These gender differences

were reversed for high school students. There were no other statistically significant

findings.

Keywords

self-efficacy, self-evaluation, music performance, gender differences

1University of Maryland, College Park, MD, USA

Corresponding Author:

Michael P. Hewitt, University of Maryland School of Music, 2110CSPAC, College Park, MD 20742, USA.

Email: mphewitt@umd.edu

Downloaded from jrm.sagepub.com at Doðu Akdeniz Üniversitesi on December 3, 2015

Hewitt 299

Good musicians spend countless hours developing the skills necessary for individual

and ensemble performance. For successful practice to occur, musicians must be prop-

erly motivated to practice, set goals for their practice sessions, and select appropriate

practice strategies to develop their ability to perform music of their own and others’

choosing. Furthermore, they need to monitor their progress while practicing and then

make judgments concerning the success (or lack of success) of their efforts. This infor-

mation then is used to readjust goals and practice plans. Because musicians generally

practice in isolation, it is particularly important for them to develop dispositions,

skills, and abilities that allow them to self-regulate their learning.

Zimmerman’s (2000) cyclical view of self-regulation has provided a theoretical

framework for the study of student learning in academic contexts. He described self-

regulation as the “self-generated thoughts, feelings, and actions that are planned and

cyclically adapted to the attainment of personal goals” (p. 14) and posited that it

incorporates three sequential phases: forethought, performance, and self-reflection.

The forethought stage precedes action and includes motivational structures, such as

self-efficacy, along with task analysis, goal setting, and planning. The performance

stage involves strategies related to the action being attempted; it includes the tactics

that a learner uses to accomplish a given goal and the metacognitive processes used

to self-monitor progress during performance. Self-reflection occurs after perfor-

mance, as students make judgments about their performance and modify strategies

based on those decisions. Judgments include self-evaluation of the performance and

decisions about what may have caused the results. These conclusions then influence

forethought and the beginning of another self-regulatory cycle (Labuhn, Zimmerman,

& Hasselhorn, 2010).

Zimmerman’s (1998a) framework, or theory, of self-regulation has its roots in the

social cognitive theory of Bandura (1997), which seeks to explain the triangular and

reciprocal relationship among an individual’s behaviors, personal factors, and envi-

ronmental circumstances. Bandura believes that reciprocity is best illustrated in the

notion of self-efficacy, or the beliefs that one has about his or her capabilities to per-

form specified tasks. Self-efficacy beliefs are related to a student’s choice of tasks,

persistence, achievement, and effort. Behaviors, such as self-observation and record-

ing, can impact the student’s efficacy beliefs by causing the student to view his or her

activity more or less favorably. The environment impacts the framework as students

receive feedback from teachers, parents, and others as to their progress toward specific

goals (Schunk, 1995). Variables, such as gender (e.g., Nielsen, 2004), school level

(e.g., Hewitt, 2005), and instrument type (e.g., Wrigley & Emmerson, 2013), also may

be related to self-efficacy.

In the present study, I examined the relationships among a number of components

of self-regulation, including motivational orientations (i.e., self-efficacy beliefs),

metacognitive elements of practice (i.e., accuracy of self-evaluation), and music per-

formance. Self-efficacy has been defined by Bandura (1997) as the judgments of an

individual’s capability to organize and execute a course of action required to achieve

selected performance goals, while self-evaluation is the comparison of self-monitored

information with a standard or goal (Zimmerman, 1998b). Additionally, I examined

Downloaded from jrm.sagepub.com at Doðu Akdeniz Üniversitesi on December 3, 2015

300 Journal of Research in Music Education 63(3)

the impact of gender (male, female), school level (middle school, high school), and

instrument family (woodwind, brass, percussion) and the interaction effects that these

attributes may have on the dependent variables.

Literature Review

The study of self-efficacy is important in education, as students who feel more effica-

cious about their learning are more likely to engage in self-regulatory actions and create

ideal learning environments for themselves (Schunk & Pajares, 2009). Sources of musi-

cal self-efficacy can include individual and group performances, observational experi-

ences, particular forms of social persuasion, and certain physiological elements, such as

sweating, headaches, and rapid heartbeat experienced by an individual while perform-

ing musical tasks (Schunk, 1991). Self-efficacy influences individual choices, because

people tend to select tasks and activities in which they feel competent and confident and

avoid those in which they do not (Schunk & Pajares, 2004). Self-efficacy correlates

positively with children’s effort and achievement in various educational contexts and

content areas, including reading (Salomon, 1984), ability to employ general learning

strategies (Pintrich & De Groot, 1990), math and verbal skills (Zimmerman & Martinez-

Pons, 1990), and writing (Meier, McCarthy & Schmeck, 1984). One possible reason for

this relationship is that students with higher self-efficacy tend to engage in tasks for a

longer period while also investing in activities that they believe will produce learning

(Meece & Painter, 2012; Schunk, 1995). High self-efficacy does not appear, however,

to produce competent performances when students lack the knowledge and skills to

perform the task competently (Schunk, 1995). Teaching learning strategies and instill-

ing positive beliefs have been shown to help students develop a higher sense of self-

efficacy and achievement (Schunk & Gunn, 1985).

Relatively little research exists on self-efficacy in music students. Perhaps the most

important are two studies of young instrumentalists preparing for solo examinations

(McCormick & McPherson, 2003; McPherson & McCormick, 2006). Using structural

equation modeling, the authors examined the impact that a variety of variables (includ-

ing self-efficacy) had on music performance. In the first study (McCormick &

McPherson, 2003), 332 Australian instrumentalists, ages 9 to 18, who were perform-

ing graded exams, were participants. They completed multiple measurement scales

immediately prior to performing the graded piece. The second study (McPherson &

McCormick, 2006) involved 686 students in Grades 1 though 8 (64.7% female) who

completed a graded instrument exam along with a self-efficacy measure immediately

prior to the performance. Together, the studies revealed that self-efficacy was the best

predictor of music performance among the variables examined, including anxiety,

grade level, and time spent in practice. Nielsen (2004) found that 1st-year college

music students who exhibited high self-efficacy used more specific learning strategies

than students with lower self-efficacy.

The relationship between self-efficacy and self-evaluation has been investigated in

a number of educational contexts. White, Kjelgaard, and Harkins (1995) found that

self-efficacy may rise with periodic self-evaluation. Self-evaluation was associated

Downloaded from jrm.sagepub.com at Doðu Akdeniz Üniversitesi on December 3, 2015

Hewitt 301

with higher self-efficacy among fourth graders learning to solve fraction problems

(Schunk, 1996) and among college students studying computer applications (Schunk

& Ertmer, 1999). Positive self-evaluations appear to lead students to feel efficacious

about their learning and motivate them to continue to work diligently, because they

believe they are capable of making further progress (Schunk, 1991). In music perfor-

mance, one study showed a moderate and positive correlation (r = .30) between self-

evaluation of the quality of progress of learning and self-efficacy for learning (Ritchie

& Williamon, 2013). Furthermore, students with low self-evaluations who neverthe-

less believe that they are capable of completing a task tend to alter learning strategies

in order to obtain the specified goals (Schunk, 1990).

The degree of accuracy of learners’ self-assessments is important for effective per-

formance and academic success (Bandura, 1997; Chen, 2003; Chen & Zimmerman,

2007). When self-efficacy judgments are in line with performances, they are said to be

well calibrated (Garavalia & Gredler, 2002; Pajares & Kranzler, 1995; Schunk &

Pajares, 2004). Most empirical studies on the accuracy of self-evaluation show that

low-ability students have difficulty calibrating their performances accurately (Labuhn

et al., 2010). Students who overestimate their capabilities often attempt—and fail at—

challenging tasks, with the result that their motivation to continue attempting the task

decreases; on the other hand, those who underestimate their abilities seek to avoid

challenging tasks (Ramdass & Zimmerman, 2008; Schunk & Pajares, 2004), reducing

their motivation for future learning.

In music education, the calibration of music performance has been investigated in

terms of a musician’s ability to accurately assess performance through self-evaluation

(Aitchison, 1995; Bergee, 1993, 1997; Hewitt, 2002, 2005, 2011; Kostka, 1997;

Morrison, Montemayor, & Wiltshire, 2004). Generally, findings suggest that instru-

mentalists are not particularly effective at evaluating their performances (Hewitt,

2005, 2011; Morrison et al., 2004), although the precise nature of the inconsistency is

in doubt. While Hewitt (2002, 2005) discovered that middle and high school students

overrated their performances, Kostka (1997) found that college students rated their

own performances lower than experts did. Bergee (1993, 1997) found that university

musicians showed no consistency in the direction of their assessments. While accu-

racy of self-evaluation has been investigated in instrumental music, the accuracy of a

musician’s self-efficacy as it relates to performance (self-efficacy calibration) in music

has not yet been investigated. Given that high self-efficacy is important for music

performance success (Faulkner, Davidson, & McPherson, 2010; McPherson &

McCormick, 2006), examining the accuracy of student musicians’ perceived musical

competence seems warranted.

Gender differences have been reported for self-efficacy in a number of fields and

appear to vary according to subject area. A meta-analysis of 187 studies (Huang,

2013) showed that males displayed higher self-efficacy than females in math and

computer skills, while females showed higher self-efficacy in language arts. Hansen

and Bubany (2008) found that men tend to have high opinions of their capabilities in

technology, mechanical fields, math, science, and data management, while women

report high capability scores in cultural sensitivity, teamwork, office services, and

Downloaded from jrm.sagepub.com at Doðu Akdeniz Üniversitesi on December 3, 2015

302 Journal of Research in Music Education 63(3)

project management. In academic areas, girls report high self-efficacy in writing

(e.g., Andrade, Wang, Du, & Akawi, 2009), while boys report it in math (T. Williams

& Williams, 2010) and some computer skills (He & Freeman, 2010), while other

curricular areas show no clear gender pattern. Females appear to use more self-

evaluation strategies when learning (Leutwyler, 2009). Girls sometimes tend to

report lower self-efficacy than do boys, especially at higher academic levels, even

when their performance is equivalent (Pajares & Miller, 1997). While differences

may exist in self-efficacy, females’ self-beliefs appear to be more accurate than

those of males in math achievement, and females are less inclined to overrate them-

selves (Pajares, 1996).

Differences in music performance self-regulation skills and beliefs based on gen-

der, age, or instrument type/family have received very little attention in peer-reviewed

research. Nielsen (2004) examined the self-efficacy beliefs of 130 first-year college

music students and found that males displayed higher self-efficacy for music perfor-

mance and greater use of critical thinking strategies than did female students. When

broken down by program, results showed that male students in performance and

church music programs displayed higher self-efficacy than did females, while females

in the music education program had higher scores than males concerning their music

performance capabilities. Middle school music students exhibited lower music perfor-

mance self-evaluation scores than high school students in some aspects of individual

performance (Hewitt, 2005), but scores were similar when evaluation took place in an

ensemble setting (Morrison et al., 2004). In subjects other than music, research sug-

gests that gender may be related to differences in achievement as children move from

elementary to middle school, with differences being fully articulated in high school

and beyond (e.g., Willingham & Cole, 1997). However, others have shown consistent

gender differences favoring girls in literacy achievement (e.g., Ready, LoGerfo,

Burkham, & Lee, 2005). Finally, in a middle school sample, Duckworth and Seligman

(2006) found a significant gender gap favoring girls in classroom grades in English,

math, and social studies but a nonexistent or small gap favoring boys on standardized

achievement and IQ tests. Instrument family may be minimally related to some meta-

cognitive aspects of music performance (e.g., Wrigley & Emmerson, 2013), but it has

been examined only sparingly in music performance.

Purpose

It is desirable for instrumental music teachers to understand and monitor student

beliefs concerning their ability to achieve success in music performance so that stu-

dents can further develop as independent, self-regulated musicians. A greater under-

standing of motivational beliefs also could lead to better teaching and learning.

Relationships among these beliefs, music performance, and other variables—such as

gender, school level, and instrument family—have not been explored. Therefore, in

the present study I investigated the relationships among self-efficacy, self-evaluation,

and music performance of secondary school band students. Specifically, the following

questions were addressed:

Downloaded from jrm.sagepub.com at Doðu Akdeniz Üniversitesi on December 3, 2015

Hewitt 303

1. What correlations exist among self-efficacy, self-evaluation, and music perfor-

mance among secondary school band students?

2. What differences based on gender, school level, and instrument family (con-

sidered alone or in combination) exist in secondary school band students’ self-

efficacy, self-evaluation, and music performance and in their calibration of

self-efficacy and self-evaluation?

Method

Participants

Instrumentalists (N = 354) were selected from three sites: (a) a summer band camp

sponsored by a large suburban school district (n = 51), (b) a summer band camp spon-

sored by a large mid-Atlantic university (n = 92), and (c) a private middle school

located in a large metropolitan area in which all students were enrolled in band (n =

211). Data sets for 14 students were incomplete and not used in the analysis, leaving

340 participants in the study: 175 females and 165 males. There were 215 woodwind,

105 brass, and 20 percussion players. The students ranged from 5th to 12th grades (see

Table S1 in online supplemental materials, http://jrme.sagepub.com/supplemental).

Data were collected at three separate points between 2006 and 2012.

Students from the school district band camp were selected after auditioning for a

panel of district music teachers. Teachers selected students based on grade level, per-

formance ability, and the number of spaces available for each instrument at the camp.

The mean grade level of students at this camp was 9.40 (SD = 1.50), while the mean

amount of performing experience was 4.51 years (SD = 1.82), and the mean private

lesson experience was 2.35 years (SD = 2.24). Students attending the university band

camp had a mean grade level of 7.51 (SD = 1.11), mean instrumental experience of

2.68 years (SD = 1.08), and mean private lesson experience of 0.87 years (SD = 1.08).

Finally, the mean grade level for students enrolled at the private middle school was

6.46 (SD = 1.18), while the mean years of experience was 1.95 (SD = 1.13). Twenty-

one (10%) of the private middle school participants were taking private lessons at the

time of data collection. Institutional review board approval was obtained, and signed

informed parent/guardian consent forms and student assent forms were acquired prior

to the collection of data.

Tasks

Students in the two band camps performed an excerpt from the first movement of

Highbridge Excursions (M. Williams, 1995). Students at the private middle school

performed an étude in three parts developed by the researcher from a number of

sources and approximately 2 min in length. The first was slow, legato, and in the con-

cert key of B♭. The second was titled “Gigue” and marked at a tempo of allegro with

a meter signature indicating 6/8. The third section was marked allegretto con moto

with a meter of 2/4 and in the concert key of A♭. The music was transposed into

Downloaded from jrm.sagepub.com at Doðu Akdeniz Üniversitesi on December 3, 2015

304 Journal of Research in Music Education 63(3)

appropriate keys and ranges to equalize difficulty among instruments. The music was

selected in order to (a) incorporate a variety of musical demands appropriate for the

grade level, (b) be at a difficulty level to ensure that neither a floor nor ceiling effect

be established during the pretest or posttest performances, and (c) show a similarity in

difficulty for each instrument within each grade level. The two instrumental music

teachers at the private middle school affirmed that the music was appropriate for stu-

dents at each grade level. Separate music selections were chosen for both fifth and

sixth grade (with one selection overlapping both grades’ tasks), while seventh- and

eighth-grade musicians learned identical music.

The entire data collection process took approximately 5 min for each participant.

Each student entered an isolated room where he or she was greeted by the researcher

or a research assistant. The student first completed a self-efficacy measure (described

in the following section), in which the student indicated how capable he or she thought

he or she was at performing the musical selection. The student then performed the

assigned music, which was recorded using an M-Audio MicroTrack digital recorder.

Immediately following the performance, each participant evaluated his or her perfor-

mance by completing the Woodwind Brass Solo Evaluation Form (WBSEF; Saunders

& Holahan, 1997). He or she was then thanked for his or her participation and left the

room.

Measures

Music performance. Students’ music performance achievement was assessed using the

Solo Evaluation portion of the WBSEF, which measures instrumental performance in

seven subareas: tone, intonation, melodic accuracy, rhythmic accuracy, tempo, inter-

pretation, and technique/articulation. Six subareas utilize a 5-point scale, while tech-

nique/articulation uses an additive assessment approach that lists five descriptors. The

authors state that the instrument’s validity is strong, as there are low correlations

among subareas and strong correlations between each subarea and the overall score.

The median reliability has been reported as α = .92 across components and subareas of

the WBSEF, while interrater reliability has been reported as strong (r = .50–.97;

Hewitt, 2002, 2005). Possible total scores ranged from 6 to 35.

Two separate three-judge panels were used: one to evaluate performances of

Highbridge Excursions and a different panel for recordings of the solo étude. For each

set, recordings were transferred to a computer, edited for length so that only the ele-

ments to be evaluated were heard, and placed on a CD in randomized order. Judges

were all experienced band directors unfamiliar with the aims of the project. A different

order was used for each set of recordings. A mean score was calculated for each per-

formance and converted to a 10-point scale for easier comparison to other variables

during analysis and to more easily compute the derived variables. The mean judge

performance scores were analyzed for internal consistency and found to be high

(Cronbach’s α = .92), supporting the notion that the judges were evaluating the same

construct.

Downloaded from jrm.sagepub.com at Doðu Akdeniz Üniversitesi on December 3, 2015

Hewitt 305

Self-efficacy. The self-efficacy measure consisted of a single question developed using

Bandura’s (2006) guidelines and adapted for use in music (McPherson & McCormick,

2006). Bandura proposed that self-efficacy be measured immediately prior to under-

taking a given event. Thus, students rated their capability for performing using a

10-point scale by circling the number that best represented how capable they thought

they were at performing the piece. Descriptive anchors were provided, with 0 listed as

not capable at all and 9 as highly capable.

Self-evaluation. To measure self-evaluation, students completed the WBSEF immediately

following their performance. These scores were converted to a 10-point scale using the

following formula: x = 10y/35, where x is the 10-point scale score and y represents the

WBSEF score. The Cronbach’s alpha measure of internal reliability was .88.

Self-efficacy calibration bias. Self-efficacy calibration bias was calculated by subtracting

the music performance score from the self-efficacy score (Pajares & Miller, 1997) and

shows the direction of errors in judgment. Thus, if a student’s self-efficacy assessment

(e.g., 10) and actual performance were roughly equivalent (e.g., 9.5), the bias score

(0.5) would be close to zero. If a student made a low assessment of his or her own

capability (3) but then performed well (5.5), the bias score would be negative (–2.5),

suggesting underconfidence. If a student expressed a high degree of capability (8) but

performed poorly (4), the bias score would be positive, indicating overconfidence.

Self-efficacy calibration accuracy. To calculate this measure, the absolute value of each

bias score was subtracted from 9 (Pajares & Miller, 1997). This score conveyed the

degree of error in judgment. A score of 0 represented maximum possible inaccuracy,

while 9 denoted complete accuracy.

Self-evaluation calibration scores. Self-evaluation calibration bias and accuracy scores

were calculated similarly to self-efficacy bias and accuracy scores, respectively, using

student self-evaluation scores and music performance ratings.

Results

To answer the study’s first question, Spearman rank correlations were calculated to

examine relationships among self-efficacy, self-evaluation, music performance, and

the four calculated calibration variables. Table 1 presents a correlation matrix for all

variables along with the means and standard deviations associated with each variable.

There was a statistically significant, strong, positive relationship (r = .69) between

self-efficacy and music performance. The relationship between self-efficacy bias and

self-evaluation bias was also statistically significant, strong and positive (r = .59),

indicating that students’ confidence in their capabilities before the performance and

their self-evaluations after the performance were similar. The performance itself did

not appear to mediate the students’ beliefs about their capabilities.

Downloaded from jrm.sagepub.com at Doðu Akdeniz Üniversitesi on December 3, 2015

306 Journal of Research in Music Education 63(3)

Table 1. Music Performance, Self-Efficacy, Self-Evaluation, and Calibrated Variables: Means,

Standard Deviations, and Spearman’s Correlations (N = 340).

Variable M SD 1 2 3 4 5 6

1. Self-efficacy 7.06 1.89 —

2. Music performance 6.80 2.18 .69* —

3. Self-evaluation 6.38 1.51 .44* .27* —

4. Self-efficacy bias 0.25 1.61 .26* –.52* .15* —

5. Self-efficacy acc. 7.77 1.07 .01 .41* –.07 –.53* —

6. Self-evaluation bias –0.41 2.25 –.36* –.76* .42* .59* –.43* —

7. Self-evaluation acc. 7.13 1.30 –.34* –.29* .21* –.02 .09 .42*

Note. acc. = accuracy.

*p < .01.

We used a multivariate analysis of variance (MANOVA) to investigate the impact

of gender, instrument family (woodwind or brass), and school level (middle or high

school) on self-efficacy, music performance, self-evaluation, and each calibrated vari-

able. Data obtained from each collection site were standardized using T scores

(Guilford, 1978; Jaccard & Becker, 1997) before being combined for analysis. Because

MANOVA procedures are particularly sensitive to the presence of outliers, the 20

participants who exceeded 1.5 times the interquartile range were removed (Tukey,

1977). Each statistically significant multivariate test was followed by a univariate test.

The nature of any differences was examined using Bonferonni post hoc tests, while

relationship strength was determined using partial eta squared (ηp2). An alpha level of

.05 was set. Because Box’s M test of equality of covariance matrices was significant

and because cell sizes were unequal, the robust Pillai’s trace statistic was used.

Statistically significant findings were identified for only the main effect of gender,

F(7, 306) = 4.37, p < .01, ηp2 = .09, and the interaction of gender and school level, F(7,

306) = 3.87, p < .01, ηp2 = .08. Univariate ANOVA tests for the gender main effect

revealed statistically significant findings for self-evaluation calibration accuracy only,

F(1, 312) = 5.79, p < .05, ηp2 = .02, as females (M = 52.03, SD = 1.26) were more

accurate in their self-evaluation than males (M = 47.76, SD = 1.25). Univariate ANOVA

tests for the interaction of gender and school level revealed significant findings for

music performance, F(1, 312) = 4.24, p < .05, ηp2 = .01; self-efficacy bias, F(1, 312) =

7.68, p < .01, ηp2 = .02; and self-evaluation bias, F(1, 312) = 9.39, p < .01, ηp2 = .03.

Middle school female music performance scores (M = 50.28, SD = 1.08) were higher

than middle school male scores (M = 48.02, SD = .83), while high school female

scores (M = 48.15, SD = 2.18) were lower than those of males (M = 52.96, SD = 2.28).

Middle school female self-efficacy bias scores (M = 49.35, SD = 1.05) were lower than

middle school male scores (M = 51.76, SD = .81), whereas high school female scores

(M = 54.03, SD = 2.14) were higher than those of high school males (M = 47.12, SD =

2.23). Female middle school self-evaluation bias scores (M = 48.36, SD = 1.10) were

lower than those of middle school males (M = 51.89, SD = .84), though high school

Downloaded from jrm.sagepub.com at Doðu Akdeniz Üniversitesi on December 3, 2015

Hewitt 307

female scores (M = 54.21, SD = 2.22) were higher than those of males (M = 47.04,

SD = 2.32). No other statistically significant findings were identified.

Discussion and Conclusion

The purpose of this study was to investigate relationships among self-efficacy, self-

evaluation, and music performance of secondary school band students. Self-efficacy

appears to be a predictor of music performance, as the correlation between these two

variables was strong and positive. This result supports Bandura’s (1997) theory and is

similar to previous findings, both in music (e.g., Faulkner et al., 2010; McPherson &

McCormick, 2006) and in other academic areas (e.g., Ramdass & Zimmerman, 2008;

Schunk & Gunn, 1985; Zimmerman & Martinez-Pons, 1990). Self-efficacy is impor-

tant for learning a music instrument, as students with higher self-efficacy tend to

engage in tasks necessary for improvement, such as practicing their instrument for

longer periods, and investing in tasks that they believe will help them to learn

(McPherson & McCormick, 2006). Pajares (1996) suggested that teachers should pay

as much attention to students’ predictions about their capabilities as to their actual

capabilities, as student predictions may be a better indicator of future motivation.

Therefore, music teachers may want to spend time teaching learning strategies and

helping to instill positive beliefs in students, as these interventions raise self-efficacy.

There was a statistically significant, strong, negative correlation (r = –.52) between

students’ self-efficacy calibration bias scores and their music performance scores.

Furthermore, self-efficacy calibration accuracy scores showed a statistically signifi-

cant moderate and positive relationship (r = .41) with music performance. Combined,

these results suggest that students with higher scores were less confident in their per-

formance ability (relative to their actual performance), though more accurate, than

students with lower scores. The latter result, regarding accuracy of assessment, is simi-

lar to the finding by Pajares and Miller (1997) that more capable math students were

better judges of their competence than those with less skill. It seems, as suggested by

Pajares and Kranzler (1995), that teachers may wish to assist students in determining

what they know and do not know so that they can implement effective learning strate-

gies. This approach could be of particular assistance to lower-achieving musicians,

who tend to overrate performances and be less accurate in assessments than higher

achieving students.

The correlation between self-evaluation calibration bias and music performance

scores was statistically significant and demonstrated a strong and negative (r = –.76)

relationship, while the statistically significant correlation between self-evaluation cali-

bration accuracy and music performance was weak and negative (r = –.29). These data

suggest that higher-performing students in the present study underrated their perfor-

mance ability while lower-performing students overrated their achievement. This

result supports and extends the findings of earlier music studies that students are not

particularly adept at evaluating their music performance capabilities. Furthermore, the

data support past research concerning the direction of the inaccuracies in relation to

student ability. Hewitt (2005, 2011) found that middle school students tended

Downloaded from jrm.sagepub.com at Doðu Akdeniz Üniversitesi on December 3, 2015

308 Journal of Research in Music Education 63(3)

to overrate their performances, while Kostka (1997) determined that college-level

musicians underrated their capabilities. Interestingly, in the present study, as perfor-

mance ability increased, self-evaluation accuracy decreased. The reason for this rela-

tionship is not clear, though there is evidence that more gifted females may be

especially critical of themselves in some subject areas (Pajares, 1996).

The relationship between self-efficacy and self-evaluation was statistically signifi-

cant, moderate, and positive (r = .44), while the relationship between self-efficacy

calibration bias and self-evaluation calibration bias was also statistically significant,

strong, and positive (r = .59), indicating that students’ self-ratings both before and

after their performance were similar and that the direction of their misdiagnoses did

not change. These data reinforce the conclusion that students were consistent in their

ratings and that the performance did not affect their self-perception. However, the cor-

relations between self-efficacy and self-evaluation calibration bias (r = –.36) and

accuracy (r = –.34), while statistically significant, were moderate and negative, indi-

cating that students who thought they were more capable of performing prior to the

performance were less accurate in their assessment and more inclined to underrate

their performance after it took place. Some researchers (Hewitt, 2002, 2005;

Zimmerman, 2000) have suggested that having students record and then listen to their

own performances may improve their ability to listen to their performance while play-

ing. Further investigation of this particular strategy and others could be helpful in

enabling students to become more capable of self-regulating their music performance

behavior.

The effect sizes for all statistically significant findings related to the MANOVA

were very small, indicating that while differences related to gender and the other mea-

sured variables existed, the magnitude of any differences was quite small. With this in

mind, it is still important to point out that a gender difference was found for self-

evaluation calibration accuracy, as females were more accurate judges of their perfor-

mance than males. Pajares (1996) found that girls tended to be better self-evaluators in

math, but the present study is the first to examine relationships among these variables

in music. The interaction of gender and school level showed differences regarding

calibration bias of both self-efficacy and self-evaluation. At the middle school level,

females were more overconfident in both self-efficacy and self-evaluation, while male

high school students were more overconfident than female high school students; again,

the differences were relatively small. These findings tend to support previous research

indicating that self-efficacy and self-evaluation gender differences may change with

age or life stage (Huang, 2013).

While males and females demonstrated slight differences for self-evaluation cali-

bration accuracy, they viewed their capabilities for self-efficacy and self-evaluation

similarly. In previous studies, males displayed higher self-efficacy in some subject

areas (e.g., Hansen & Bubany, 2008) and females in other areas (e.g., Andrade et al.,

2009). This was the first study to examine differences in gender on these variables, and

at this global level of evaluation, there were none. It may be interesting to examine, in

future studies, whether any gender differences appear with regard to particular ele-

ments of music performance (e.g., tone quality, expression).

Downloaded from jrm.sagepub.com at Doðu Akdeniz Üniversitesi on December 3, 2015

Hewitt 309

Some researchers have found that gender contributes to achievement disparity as

students move from elementary to middle school and that these gender differences

become even more apparent in high school and thereafter (e.g., Willingham & Cole,

1997); others (e.g., Ready et al., 2005) have found that that gender differences remain

relatively constant over time. While the present study did not examine elementary

grade–level students, gender differences were found between middle and high school

students in terms of both music achievement and self-perception. Males outperformed

females and were more overconfident in their abilities, as reflected by self-efficacy

and self-evaluation calibration bias scores; however, when school level is considered,

the results show that high school males outperformed their female counterparts while

middle school males did not. Furthermore, males were more underconfident (relative

to actual performance) in both self-efficacy and self-evaluation than were females at

the high school level, while the opposite was true for middle school musicians. Further

studies should be undertaken to examine this transformation from middle to high

school.

The present study did not explain all of the variance among the variables related to

self-regulation. Clearly, there are other variables in the forethought, performance, and

self-reflection stages of Zimmerman’s (2000) model that may impact an individual’s

ability to self-regulate for music performance. These unexamined variables should be

investigated through descriptive and experimental studies to better understand the

development of independence among young musicians. The impact of specific task

strategies, such as imagery, goal setting, and self-recording, should be examined to

help researchers and teachers alike develop successful teaching strategies for instru-

mentalists. An all-inclusive self-regulation model, developed through structural equa-

tion modeling, of instrumental music performance may be helpful to the profession.

Researchers also may wish to better control, a priori, the performance tasks under-

taken. The present study involved participants who performed one of two sets of music

in different contexts. While similar procedures have been used in other music studies

of self-regulation (McCormick & McPherson, 2003; McPherson & McCormick,

2006), and statistical controls were undertaken prior to analysis, it may be interesting

to examine results based on a more controlled design, though doing so presents other

issues related to generalizability. For instance, the behaviors, comments, and attitudes

toward the musicians and camp instructors may have influenced students’ self-beliefs

concerning the future and past performances.

Accurate self-efficacy and self-evaluation skills are important for musicians to

develop if they wish to become self-regulated musicians; both of these variables are

associated closely with music performance. Efforts to improve music students’ self-

regulation capacity are needed as the profession continues to examine ways in which

young students learn. As practitioners develop effective methods and curricular mate-

rials for developing independent musicianship skills, they may also wish to be aware

of gender and school-level differences among students’ beliefs, so that they can adopt

appropriate instructional approaches. Researchers can contribute to the quality of

instruction by continuing to examine other components of self-regulation of music

performance.

Downloaded from jrm.sagepub.com at Doðu Akdeniz Üniversitesi on December 3, 2015

310 Journal of Research in Music Education 63(3)

Declaration of Conflicting Interests

The author declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship,

and/or publication of this article.

Funding

The author received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this

article.

Supplemental Material

Table S1 is available at http://jrme.sagepub.com/supplemental.

References

Aitchison, R. A. (1995). The effects of self-evaluation techniques on the musical performance,

self-evaluation accuracy, motivation, and self-esteem of middle school instrumental music

students. Dissertation Abstracts International, 56(10A), 3875.

Andrade, H. L., Wang, X., Du, Y., & Akawi, R. L. (2009). Rubric-referenced self-assessment

and self-efficacy for writing. Journal of Educational Research, 102, 287–301. doi:10.3200/

JOER.102.4.287-302

Bandura, A. (1997). Self-efficacy: The exercise of control. New York, NY: Freeman.

Bandura, A. (2006). Guide for constructing self-efficacy scales. In F. P. T. Urdan (Ed.), Self-

efficacy beliefs of adolescents (pp. 307–337). Charlotte, NC: Information Age.

Bergee, M. J. (1993). A comparison of faculty, peer, and self-evaluation of applied brass jury

performances. Journal of Research in Music Education, 41, 19-27. doi:10.2307/3345476

Bergee, M. J. (1997). Relationships among faculty, peer, and self-evaluations of applied per-

formances. Journal of Research in Music Education, 45, 601–612. doi:10.2307/3345425

Chen, P. P. (2003). Exploring the accuracy and predictability of the self-efficacy beliefs of

seventh-grade mathematics students. Learning and Individual Differences, 14, 79–92.

doi:10.1016/j.lindif.2003.08.003

Chen, P. P., & Zimmerman, B. J. (2007). A cross-national comparison study on the accuracy

of self-efficacy beliefs of middle-school mathematics students. Journal of Experimental

Education, 75, 221–244. doi:10.3200/JEXE.75.3.221-244

Duckworth, A. L, & Seligman, M. E. P. (2006). Self-discipline gives girls the edge: Gender in

self-discipline, grades, and achievement test scores. Journal of Educational Psychology,

98, 198–208.

Faulkner, R., Davidson, J. W., & McPherson, G. E. (2010). The value of data mining in

music education research and some findings from its application to a study of instrumen-

tal learning during childhood. International Journal of Music Education, 28, 212–230.

doi:10.1177/0255761410371048

Garavalia, L. S., & Gredler, M. E. (2002). An exploratory study of academic goal setting,

achievement calibration and self-regulated learning. Journal of Instructional Psychology,

29, 221–230.

Guilford, J. P. (1978). Fundamental statistics in psychology and education. New York, NY:

McGraw-Hill.

Hansen, J. T., & Bubany, S. T. (2008). Do self-efficacy and ability self-estimate scores reflect

distinct facets of ability judgments? Measurement and Evaluation in Counseling and

Development, 41, 66–88.

Downloaded from jrm.sagepub.com at Doðu Akdeniz Üniversitesi on December 3, 2015

Hewitt 311

He, J., & Freeman, L.A. (2010). Are men more technology-oriented than women? The role of

gender on the development of general computer self-efficacy of college students. Journal

of Information Systems Education, 21, 203–212.

Hewitt, M. P. (2002). Self-evaluation tendencies of junior high instrumentalists. Journal of

Research in Music Education, 50, 215–226. doi:10.2307/3345799

Hewitt, M. P. (2005). Self-evaluation accuracy among high school and middle school

instrumentalists. Journal of Research in Music Education, 53, 148–161. doi:10.2307/

3345515

Hewitt, M. P. (2011). The impact of self-evaluation instruction on student self-evaluation,

music performance, and self-evaluation accuracy. Journal of Research in Music Education,

59, 6–20. doi:10.1177/0022429410391541

Huang, C. (2013). Gender differences in academic self-efficacy: a meta-analysis. European

Journal of Psychology of Education, 28(1), 1–35. doi: 10.1007/s10212-011-0097-y

Jaccard, J., & Becker, M. A. (1997). Statistics for the behavioral sciences (3rd ed.). Pacific

Grove, CA: Brooks/Cole.

Kostka, M. J. (1997). Effects of self-assessment and successive approximations on “know-

ing” and “valuing” selected keyboard skills. Journal of Research in Music Education, 45,

273–281. doi:10.2307/3345586

Labuhn, A. S., Zimmerman, B. J., & Hasselhorn, M. (2010). Enhancing students’ self-regulation

and mathematics performance: The influence of feedback and self-evaluative standards.

Metacognition and Learning, 5(2), 173–194. doi:10.1007/s11409-010-9056-2

Leutwyler, B. (2009). Metacognitive learning strategies: Differential development patterns in

high school. Metacognition Learning, 4, 111–123. doi:10.1007/s11409-009-9037-5

McCormick, J., & McPherson, G. (2003). The role of self-efficacy in a musical performance

examination: An exploratory structural equation analysis. Psychology of Music, 31, 37–51.

doi:10.1177/0305735603031001322

McPherson, G. E., & McCormick, J. (2006). Self-efficacy and music performance. Psychology

of Music, 34, 322–336. doi:10.1177/0305735606064841

Meece, J. L., & Painter, J. (2012). Gender, self-regulation, and motivation. In D. H. Schunk &

B. J. Zimmerman (Eds.), Motivation and self-regulated learning: Theory, research, and

applications (pp. 339–368). New York, NY: Rutledge.

Meier, S., McCarthy, P. R., & Schmeck, R. R. (1984) Validity of self-efficacy as a predic-

tor of writing performance. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 8, 107–120. doi:10.1007/

BF01173038

Morrison, S. J., Montemayor, M., & Wiltshire, E. S. (2004). The effect of a recorded model

on band students’ performance self-evaluations, achievement, and attitude. Journal of

Research in Music Education, 52, 116–129. doi:10.2307/3345434

Nielsen, S. G. (2004). Strategies and self-efficacy beliefs in instrumental and vocal individual

practice: A study of students in higher music education. Psychology of Music, 32, 418–431.

doi:10.1177/0305735604046099

Pajares, F. (1996). Self-efficacy beliefs and mathematical problem-solving of gifted students.

Contemporary Educational Psychology, 21, 325–344. doi:10.1006/ceps.1996.0025

Pajares, F., & Kranzler, J. (1995). Self-efficacy beliefs and general mental ability in mathemati-

cal problem solving. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 20, 426–443. doi:10.1006/

ceps.1995.1029

Pajares, F., & Miller, M. (1997). Mathematics self-efficacy and mathematical problem solving:

Implications of using different forms. Journal of Experimental Education, 65, 213–228. doi:

10.1080/00220973.1997.9943455

Downloaded from jrm.sagepub.com at Doðu Akdeniz Üniversitesi on December 3, 2015

312 Journal of Research in Music Education 63(3)

Pintrich, P. R., & De Groot, V. (1990). Motivational and self-regulated learning components

of classroom academic performance. Journal of Educational Psychology, 82, 33–40.

doi:10.1037/0022-0663.82.1.33

Ramdass, R., & Zimmerman, B. (2008). Effects of self-correction strategy training on middle

school students’ self-efficacy, self-evaluation, and mathematics division learning. Journal

of Advanced Academics, 20, 18–41.

Ready, D. D., LoGerfo, L. F., Burkam, D. T., & Lee, V. E. (2005). Explaining girls’ advantage

in kindergarten literacy learning: Do classroom behaviors make a difference? Elementary

School Journal, 106, 21–38. doi:10.1086/496905

Ritchie, L., & Williamon, A. (2013). Measuring musical self-regulation: Linking processes,

skills, and beliefs. Journal of Education and Training Studies, 1(1), 106–117. doi:10.11114/

jets.v1i1.81

Salomon, G. (1984). Television is “easy” and print is “tough”: The differential investment of

mental effort in learning as a function of perceptions and attributions. Journal of Educational

Psychology, 76, 647–658. doi:10.1037//0022-0663.76.4.647

Saunders, T. C., & Holahan, J. M. (1997). Criteria-specific rating scales in the evaluation of

high school instrumental performance. Journal of Research in Music Education, 45, 259–

272. doi:10.2307/3345585

Schunk, D. H. (1990). Goal setting and self-efficacy during self-regulated learning. Educational

Psychologist, 25, 71–86. doi:10.1207/s15326985ep2501_6

Schunk, D. H. (1991). Self-efficacy and academic motivation. Educational Psychologist, 26,

207–231. doi:10.1207/s15326985ep2603&4_2

Schunk, D. H. (1995). Self-efficacy and education and instruction. In J. E. Maddux (Ed.), Self-

efficacy, adaptation, and adjustment: Theory, research, and applications (pp. 281–303).

New York, NY: Plenum.

Schunk, D. H. (1996). Goal and self-evaluative influences during children’s cognitive skill learning.

American Educational Research Journal, 33, 359–382. doi:10.3102/00028312033002359

Schunk, D. H., & Ertmer, P. A. (1999). Self-regulatory processes during computer skill acquisi-

tion: Goals and self-evaluative influences. Journal of Educational Psychology, 91, 251–

260. doi:10.1037//0022-0663.91.2.251

Schunk, D. H., & Gunn, T. P. (1985). Modeled importance of task strategies and achievement

beliefs: Effects on self-efficacy and skill development. Journal of Early Adolescence, 5,

247–258. doi:10.1177/0272431685052008

Schunk, D. H., & Pajares, F. (2004). Self-efficacy in education revisited. Empirical and applied

evidence. In D. M. McInerney & S. V. Etten (Eds.), Big theories revisited (pp. 115–138).

Greenwich, CT: Information Age.

Schunk, D. H., & Pajares, F. (2009). Self-efficacy theory. In K. Wentzel & A. Wigfield (Eds.),

Handbook of motivation at school (pp. 35–53). New York, NY: Routledge.

Tukey, J. W. (1977). Exploratory data analysis. Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley.

White, P. H., Kjelgaard, M. M., & Harkins, S. G. (1995). Testing the contribution of self-

evaluation to goal-setting. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 69, 69–79.

doi:10.1037/0022-3514.69.1.69

Williams, M. (1995). Highbridge excursions. Van Nuys, CA: Alfred.

Williams, T., & Williams, K. (2010). Self-efficacy and performance in mathematics: Reciprocal

determinism in 33 nations. Journal of Educational Psychology, 102, 453–466. doi:10.1037/

a0017271

Willingham, W. W., & Cole, N. S. (Eds.). (1997). Gender and fair assessment: Mahwah, NJ:

Erlbaum.

Downloaded from jrm.sagepub.com at Doðu Akdeniz Üniversitesi on December 3, 2015

Hewitt 313

Wrigley, W. J., & Emmerson, S. B. (2013). The experience of the flow state in live music per-

formance. Psychology of Music, 41, 292–305. doi:10.1177/0305735611425903

Zimmerman, B. J. (1998a). Academic studying and the development of personal skill: A self-

regulatory perspective. Educational Psychologist, 33, 73–86. doi:10.1080/00461520.1998

.9653292

Zimmerman, B. J. (1998b). Developing self-fulfilling cycles of academic regulation: An analy-

sis of exemplary instructional models. In D. H. Schunk & B. J. Zimmerman (Eds.), Self-

regulated learning: From teaching to self-reflective practice (pp. 1–19). New York, NY:

Guilford.

Zimmerman, B. J. (2000). Attaining self-regulation: A social cognitive perspective. In

M. Boekaerts, P. Pintrich, & M. Zeidner (Eds.), Handbook of self-regulation (2nd ed.,

pp. 13–39). San Diego, CA: Academic Press.

Zimmerman, B. J., & Martinez-Pons, M. (1990). Student differences in self-regulated learning:

Relating, grade, sex, and giftedness to self-efficacy and strategy use. Journal of Educational

Psychology, 82, 51–59. doi:10.1037//0022-0663.82.1.51

Author Biography

Michael P. Hewitt is professor of music education at the University of Maryland. His research

interests include self-regulation in music, music performance assessment, and music teacher

education.

Submitted September 18, 2013; accepted November 14, 2014.

Downloaded from jrm.sagepub.com at Doðu Akdeniz Üniversitesi on December 3, 2015

You might also like

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5820)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1093)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (845)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (590)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (898)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (540)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (349)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (822)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (122)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (401)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- 2020 Good Intern Programme BookletsDocument85 pages2020 Good Intern Programme BookletsDineshan RanasingheNo ratings yet

- The Code of Jewish ConductDocument295 pagesThe Code of Jewish ConductNicolás Berasain0% (1)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- Kami Export - Minh Le - CA Intersession Earth Science A Credit 2 SSDocument28 pagesKami Export - Minh Le - CA Intersession Earth Science A Credit 2 SShNo ratings yet

- Chapter 2Document7 pagesChapter 2James Brian Garcia Garay67% (6)

- The Importance of Communication in The Workplace-4 PDFDocument2 pagesThe Importance of Communication in The Workplace-4 PDFmgNo ratings yet

- Using Data Mining For Predicting Relationships Between Online Question Theme and Final GradeDocument12 pagesUsing Data Mining For Predicting Relationships Between Online Question Theme and Final GradesilacanNo ratings yet

- British Council ABRSM 2019 Practical Application FormDocument3 pagesBritish Council ABRSM 2019 Practical Application FormsilacanNo ratings yet

- Kodaly Violin2Document19 pagesKodaly Violin2silacanNo ratings yet

- Cyprus DanceDocument6 pagesCyprus DancesilacanNo ratings yet

- Dancla Petites Pieces PDFDocument13 pagesDancla Petites Pieces PDFsilacanNo ratings yet

- Crickboom MatheuDocument42 pagesCrickboom MatheusilacanNo ratings yet

- Accolay - Concierto No 1 La Menor - Violin PianoDocument18 pagesAccolay - Concierto No 1 La Menor - Violin PianoCarlos Garcia MurilloNo ratings yet

- Westside Test Anxiety ScaleDocument2 pagesWestside Test Anxiety ScaleClaire Ann SeldaNo ratings yet

- TEACHING RECEPTIVE SKILL ListeningDocument4 pagesTEACHING RECEPTIVE SKILL ListeningTenri Fada TajuddinNo ratings yet

- Reflection On 4as Lesson PlanDocument4 pagesReflection On 4as Lesson Planofelia guinitaran100% (1)

- Second Story Window Fluency HomeworkDocument6 pagesSecond Story Window Fluency Homeworkerrrw8mg100% (1)

- Walter CDocument2 pagesWalter Capi-438993118No ratings yet

- The Philippine Health Care Delivery SystemDocument4 pagesThe Philippine Health Care Delivery SystemKris Elaine GayadNo ratings yet

- Scheme of Work English Year 5 KSSR: First TermDocument15 pagesScheme of Work English Year 5 KSSR: First TermAnonymous YIY6axQNo ratings yet

- Detailed Narrative Report of What Has Been Transpired From The Start and End of ClassDocument4 pagesDetailed Narrative Report of What Has Been Transpired From The Start and End of ClassMaribel LimsaNo ratings yet

- Articulo Familiar MinuchiDocument19 pagesArticulo Familiar MinuchiHanna GarnicaNo ratings yet

- If We Are All So UniqueDocument2 pagesIf We Are All So UniqueEvelina VirNo ratings yet

- InsightDocument73 pagesInsightSanjana Garg100% (1)

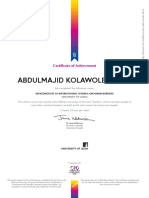

- Abdulmajid Kolawole Yusuf: Certificate of AchievementDocument2 pagesAbdulmajid Kolawole Yusuf: Certificate of AchievementKolawole Kolawole YUSUFNo ratings yet

- Mathematics: Quarter 1 - Module 3: Multiplication of FractionsDocument32 pagesMathematics: Quarter 1 - Module 3: Multiplication of FractionsYna FordNo ratings yet

- Final Graduation ListDocument108 pagesFinal Graduation ListJonn MashNo ratings yet

- Classified 2015 08 17 000000Document7 pagesClassified 2015 08 17 000000sasikalaNo ratings yet

- Dvaya ChurukkuDocument26 pagesDvaya Churukkuajiva_rts100% (1)

- A1PLUS UNIT 1 Test Answer Key Standard PDFDocument2 pagesA1PLUS UNIT 1 Test Answer Key Standard PDFana maria csalinas100% (1)

- Teaching Derived Relational Responding To Young ChildrenDocument10 pagesTeaching Derived Relational Responding To Young ChildrenErik AlmeidaNo ratings yet

- Concept of Supervision: B. Ed (1.5 Year) Online Workshop Course Code: 8605Document34 pagesConcept of Supervision: B. Ed (1.5 Year) Online Workshop Course Code: 8605ilyas100% (1)

- The Sexuality Scale An Instrument To Measure Sexual-Esteem, Sexual-Depression, and Sexual-PreoccupationDocument29 pagesThe Sexuality Scale An Instrument To Measure Sexual-Esteem, Sexual-Depression, and Sexual-PreoccupationRalu S.No ratings yet

- 西南太平洋群岛鸟类(文字为主)Document537 pages西南太平洋群岛鸟类(文字为主)Yogi HwangNo ratings yet

- By Jane Cadwallader: Miss Pilar Labanda Miss Analía OvejeroDocument14 pagesBy Jane Cadwallader: Miss Pilar Labanda Miss Analía OvejeroJorge RuizNo ratings yet

- ICAO Handbook For Cabin Crew Recurrent Training During COVID-19Document32 pagesICAO Handbook For Cabin Crew Recurrent Training During COVID-19Olga100% (1)

- Bobby LeBlanc ProfileDocument5 pagesBobby LeBlanc ProfileCiera-Sadé WadeNo ratings yet

- JD - FAE or Test EngineerDocument2 pagesJD - FAE or Test EngineerChanti KumpatlaNo ratings yet