Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Poor People Deserve To Taste Something Other Than Shame

Poor People Deserve To Taste Something Other Than Shame

Uploaded by

Jose ClavijoOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Poor People Deserve To Taste Something Other Than Shame

Poor People Deserve To Taste Something Other Than Shame

Uploaded by

Jose ClavijoCopyright:

Available Formats

Poor People Deserve To Taste Something Other Than

Shame

Ijeoma Oluo

May 12, 2016 · 5 min read

“They’re buying steak and lobster with food stamps!”

Every few months this headline, or one like it, finds its way

around conservative publications, into political pundit shows,

and onto senate floors. A relic of the “Welfare Queen” stories of

the ’80s, the fear of poor people squandering the charity of

hard-working American tax dollars leads to countless classist

memes, reactionary petitions, and tighter restrictions on the

ways in which poor Americans are allowed to live.

When I hear these words, I don’t think of lobster or steak, I think

of Boston cream pie. A Boston cream pie was what my mother

came home with one evening when I was in the 6th grade. She

walked in the house after another evening of working late and

placed a paper grocery bag on the dining table.

“Kids!” she announced excitedly, “I’ve got a treat for you!”

My brother and I gathered around the table as she produced a

cake from the grocery bag. “Ever have a Boston cream pie?” she

asked.

I was furious with her.

By 6th grade I had already figured out that we were poor and that

it was a moral failure on our part. We were defective, and

therefore unable to afford the things that normal families could

afford. My friends had snack cabinets full of treats that they could

just reach into whenever they felt like it. We had no phone, often

no electricity, and if there was a package of ramen in our

cupboard, it was a very good day. I wasn’t quite sure why, but I

knew that this was all my mom’s fault. She had married the wrong

man, she had gotten the wrong job, she hadn’t saved enough or

scraped enough or worked hard enough. But we had no food in

our fridge and I was pretty sure this Boston cream pie was why.

And it wasn’t even pie; it’s a cake. I was so embarrassed and

ashamed and angry to see it sitting there on our table.

Nonetheless, at my mom’s insistence, I sat at the table with my

mother and brother to eat some of it, resentfully choking down

small bites and picking at the cream filling while my brother

devoured his in seconds. My mother slowly lifted each bite to her

mouth, closing her eyes as she chewed, making small sighing

noises. She talked about the first time she had ever had Boston

cream pie as a kid, when she was about our age, on vacation with

her parents. “It was so indulgent,” she remembered.

I didn’t want any part of it. I didn’t want my mom to enjoy any

part of our poor existence. I wanted her to be ashamed and sorry.

I didn’t understand that my mom already was ashamed and sorry.

I didn’t know that she walked around ashamed and sorry every

day. I didn’t see that she stood in food bank and church lines

ashamed and sorry. I didn’t see that she went to holiday collection

services ashamed and sorry. I didn’t see that she took us to our

free dental appointments ashamed and sorry. I didn’t see that

every time she passed over those food stamps to try to feed us she

was ashamed and sorry. I didn’t realize that every message that

had surrounded me and told me that we were poor because my

mom was a bad mom who couldn’t take care of us had not only

surrounded my mom, but had filled her lungs and rested in her

heart. I understood only what the pundits had wanted me to see —

that she was a poor woman who was squandering what she

already didn’t deserve.

And that is what we are saying, when we talk disdainfully about

poor people buying lobster and steak, or nice phones, or new

clothes. We are saying, you are not sorry and ashamed enough.

You do not hate your poor existence enough. Because when you

are poor, you are supposed to take the help that is never enough

and stretch it so you have just enough misery to get by. Because

when you are poor you are supposed to eat ramen every day and

you are supposed to know that every bite of that nutrition-less

soup is your punishment for bad life decisions. Your kids are

supposed to be mocked at school for their outdated clothes — how

else will they know to not end up like you when they grow up?

And for heaven’s sake, the last thing you should be allowed to do

is to take one evening with your kids to sit at a table and eat a dish

of pure indulgence in the hopes that your children will have a few

minutes to feel the same way you did when you were a kid and you

weren’t ashamed to exist.

I look back on this time and I do feel shame. Not for being poor,

but for allowing the judgement of others to dehumanize both me

and my mom. I’m ashamed because as I sat at that table, I didn’t

taste a single bite of that Boston cream pie. I haven’t had Boston

cream pie since, and I doubt I ever will, because the opportunity

for it to taste like indulgence and humanity and normality has

been lost, and now it can only taste like regret.

And that is all that we accomplish, when we shame poor people

for daring to live for a moment like they are not at the mercy of

others. We deny them the opportunity to live like actual human

beings worthy of dignity and respect. Everyone should be able to

bring home a steak or a lobster, or a Boston cream pie, once in a

while.

Questions:

1. Is there a clear Thesis Statement? If yes, what is it? If no, what is the main idea?

Yes there is a clear thesis statement: When we talk disdainfully about poor people

buying lobster and steak, or nice phones, or new clothes. We are saying, you are not

sorry and ashamed enough.

2. Is there a clear PCR? Can you write the different parts? If not, what is the purpose of this

article?

3. How does the author make her point? (Think technique)

4. Have you ever thought of poverty from this point of view?

5. What connections/inferences can you make between this article and the reading in your

textbook on pages 42-43?

6. Can you find examples of Gerunds and Infinitives after Certain Verbs, Relative Clauses

or the Present Perfect/Present Perfect Progressive in the text and highlight them?

You might also like

- BTF-ELAC Local Government Empowerment ProgramDocument10 pagesBTF-ELAC Local Government Empowerment ProgramAbdullah M. MacapasirNo ratings yet

- Holiness by Micah Stampley (Chords)Document1 pageHoliness by Micah Stampley (Chords)Jesse Wilson100% (3)

- Erie Flowchart 2Document1 pageErie Flowchart 2diannecl-1No ratings yet

- Pub The-Snouters PDFDocument90 pagesPub The-Snouters PDFJeremy VargasNo ratings yet

- Poor People Deserve To Taste Something Other Than ShameDocument5 pagesPoor People Deserve To Taste Something Other Than ShameDaniela MorelosNo ratings yet

- Thanks To My Parents: Pangasinan Damacion Immigrants of Suisun Valley, California, 1912-2013Document4 pagesThanks To My Parents: Pangasinan Damacion Immigrants of Suisun Valley, California, 1912-2013Fo FoFabulousNo ratings yet

- MidtermDocument3 pagesMidtermapi-565341764No ratings yet

- Collard Green Curves: A Fat Girl’s Journey from Childhood Obesity to Healthy LivingFrom EverandCollard Green Curves: A Fat Girl’s Journey from Childhood Obesity to Healthy LivingRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (2)

- The Krakauer Table: Shakira SisonDocument8 pagesThe Krakauer Table: Shakira SisonKyle Mendrez-MaurerNo ratings yet

- The Price of Admission: Embracing a Life of Grief and JoyFrom EverandThe Price of Admission: Embracing a Life of Grief and JoyRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- 7 Ways To Love Your MotherDocument5 pages7 Ways To Love Your MotherFrederick PatacsilNo ratings yet

- A Harlot's Cry: One Woman's Thirty-Five-Year Journey through the Sex IndustryFrom EverandA Harlot's Cry: One Woman's Thirty-Five-Year Journey through the Sex IndustryNo ratings yet

- Backbone: From Terror to Triumph: Taking Control of Your DestinyFrom EverandBackbone: From Terror to Triumph: Taking Control of Your DestinyNo ratings yet

- Where the Sun Don’T Shine and the Shadows Don’T Play: Growing up with an Obsessive-Compulsive HoarderFrom EverandWhere the Sun Don’T Shine and the Shadows Don’T Play: Growing up with an Obsessive-Compulsive HoarderNo ratings yet

- It Makes Sense!: Directions: Read The Essay Below. Write A Review of The Essay Expressing Your Personal Idea orDocument4 pagesIt Makes Sense!: Directions: Read The Essay Below. Write A Review of The Essay Expressing Your Personal Idea orlopezacilegnaNo ratings yet

- Kids Are Turds: Brutally Honest Humor for the Pooped-Out ParentFrom EverandKids Are Turds: Brutally Honest Humor for the Pooped-Out ParentNo ratings yet

- Akin to the Truth: A Memoir of Adoption and IdentityFrom EverandAkin to the Truth: A Memoir of Adoption and IdentityRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (3)

- IBA Gas Field QuestionsDocument19 pagesIBA Gas Field Questionssazzadmunna5950% (1)

- Invitation To BidDocument92 pagesInvitation To BidAnita QueNo ratings yet

- Ubuntu 1404 Server GuideDocument380 pagesUbuntu 1404 Server GuideelvischomioNo ratings yet

- Jamb CRK Past QuestionsDocument79 pagesJamb CRK Past Questionsabedidejoshua100% (1)

- Aspire Budget 2.8 PDFDocument274 pagesAspire Budget 2.8 PDFLucas DinizNo ratings yet

- Apollo and Daphne Whats Love Got To Do W PDFDocument1 pageApollo and Daphne Whats Love Got To Do W PDFGraceNo ratings yet

- 25 MM BushmasterDocument2 pages25 MM BushmasterMatthew Moonie Herbert100% (1)

- Customer Services A Part of Market OrientationDocument5 pagesCustomer Services A Part of Market OrientationMajeed AnsariNo ratings yet

- 3 Transcripts From The Fasting Transformation SummitDocument42 pages3 Transcripts From The Fasting Transformation SummitgambouchNo ratings yet

- Annexure ADocument1 pageAnnexure Atoocool_sashi100% (2)

- 08 - QT Essentials - Model View ModuleDocument32 pages08 - QT Essentials - Model View ModuleChristiane MeyerNo ratings yet

- Brand ManagementDocument79 pagesBrand ManagementTrinh Thi Thu TrangNo ratings yet

- Cant Hurt Me Master Your Mind and Defy The OddsDocument32 pagesCant Hurt Me Master Your Mind and Defy The Oddspatrick.knapp196100% (46)

- Walk in Interview - TO-IIDocument2 pagesWalk in Interview - TO-IIRohit ChauhanNo ratings yet

- VIOS Physical & Virtual Ethernet CFG For 802.1qDocument1 pageVIOS Physical & Virtual Ethernet CFG For 802.1qVasanth VuyyuruNo ratings yet

- Mastermind 2 Unit 1 Grammar and Vocabulary Test ADocument7 pagesMastermind 2 Unit 1 Grammar and Vocabulary Test ARolando Guzman Martinez100% (1)

- GST ProjectDocument20 pagesGST ProjectHarshithaNo ratings yet

- $ROW9KSXDocument18 pages$ROW9KSXRoberto SangregorioNo ratings yet

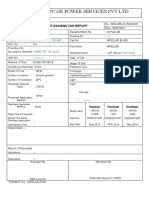

- NTPC Ge Power Services PVT LTD: Liquid Penetrant Examination ReportDocument2 pagesNTPC Ge Power Services PVT LTD: Liquid Penetrant Examination ReportBalkishan DyavanapellyNo ratings yet

- What Exactly Is ShivlingDocument1 pageWhat Exactly Is ShivlingApoorva BhattNo ratings yet

- Redeeming Time: Heidegger, Woolf, Eliot and The Search For An Authentic TemporalityDocument10 pagesRedeeming Time: Heidegger, Woolf, Eliot and The Search For An Authentic TemporalityazraNo ratings yet

- NR446 RUA-Guideines and Rubric-Revised July 14 2015Document10 pagesNR446 RUA-Guideines and Rubric-Revised July 14 2015the4gameNo ratings yet

- Econ IA International Economics TextDocument3 pagesEcon IA International Economics TextPavel VondráčekNo ratings yet

- Reb 611Document76 pagesReb 611Adil KhanNo ratings yet

- Types of PropagandaDocument13 pagesTypes of PropagandaDarren NipotseNo ratings yet

- AOCS Recommended Practice Ca 12-55 Phosphorus PDFDocument2 pagesAOCS Recommended Practice Ca 12-55 Phosphorus PDFWynona Basilio100% (1)