Professional Documents

Culture Documents

1998generalintelligencefactor PDF

1998generalintelligencefactor PDF

Uploaded by

Delaila Irma Tan CalindasCopyright:

Available Formats

You might also like

- TL Design Manual - Rev0.5Document64 pagesTL Design Manual - Rev0.5Syed Ahsan Ali Sherazi100% (2)

- Spectrophotometric Method For Simultaneous Estimation of Levofloxacin and Ornidazole in Tablet Dosage FormDocument14 pagesSpectrophotometric Method For Simultaneous Estimation of Levofloxacin and Ornidazole in Tablet Dosage FormSumit Sahu0% (1)

- 2011 Instant Expert IntelligenceDocument9 pages2011 Instant Expert IntelligenceJamie RobinsonNo ratings yet

- Umbrella Term Mind Reason Plan Solve Problems Abstractly Language Learn Creativity Personality Character Knowledge WisdomDocument7 pagesUmbrella Term Mind Reason Plan Solve Problems Abstractly Language Learn Creativity Personality Character Knowledge WisdomAVINANDANKUMARNo ratings yet

- Deary Penke Johnson 2010 - Neuroscience of Intelligence ReviewDocument12 pagesDeary Penke Johnson 2010 - Neuroscience of Intelligence ReviewAndres CorzoNo ratings yet

- Intelligence: Theories about Psychology, Signs, and StupidityFrom EverandIntelligence: Theories about Psychology, Signs, and StupidityNo ratings yet

- Intelligence: Sta. Teresa CollegeDocument5 pagesIntelligence: Sta. Teresa Collegeaudree d. aldayNo ratings yet

- (1987) Suggested Two Different FormsDocument6 pages(1987) Suggested Two Different FormsAllan DiversonNo ratings yet

- Psychology 101 INTELLIGENCEDocument17 pagesPsychology 101 INTELLIGENCEAEDRIELYN PICHAYNo ratings yet

- 2 Schooling Makes You Smarter PDFDocument12 pages2 Schooling Makes You Smarter PDFvalensalNo ratings yet

- Text 4.1 Intelligence: What Is It?Document7 pagesText 4.1 Intelligence: What Is It?NURULHIKMAH NAMIKAZENo ratings yet

- Cognition (Contd.) Aptitude and IntelligenceDocument13 pagesCognition (Contd.) Aptitude and IntelligenceMajid JamilNo ratings yet

- IntelligenceDocument18 pagesIntelligencetasfia2829No ratings yet

- RSPM ReportDocument16 pagesRSPM ReportRia ManochaNo ratings yet

- Intelligence LectureDocument32 pagesIntelligence LectureHina SikanderNo ratings yet

- IQ (The Intelligence Quotient) : Louis D Matzel Bruno SauceDocument10 pagesIQ (The Intelligence Quotient) : Louis D Matzel Bruno SauceHouho DzNo ratings yet

- EducationDocument145 pagesEducationVictor ColivertNo ratings yet

- Chapter 9 Summary NotesDocument6 pagesChapter 9 Summary Notesshiela badiangNo ratings yet

- IQ & Creativity: Jalalabad, CantonmentDocument19 pagesIQ & Creativity: Jalalabad, CantonmentDipto PaulNo ratings yet

- Proposition 1 - DebateDocument3 pagesProposition 1 - DebateLydia CLNo ratings yet

- LDRSHP IntelligenceDocument13 pagesLDRSHP IntelligenceMazin HayderNo ratings yet

- Intellegance 9: DR Mohammad A.S. KamilDocument21 pagesIntellegance 9: DR Mohammad A.S. Kamilمصطفى رسول هاديNo ratings yet

- 12 Psychology Theory of IntelligenceDocument3 pages12 Psychology Theory of IntelligenceBerryNo ratings yet

- Intelligence TestingDocument4 pagesIntelligence Testinghina FatimaNo ratings yet

- Title-: Intelligence and It's Various ExplanationsDocument15 pagesTitle-: Intelligence and It's Various ExplanationsShreya BasuNo ratings yet

- College of Education: Lesson 9Document4 pagesCollege of Education: Lesson 9Mikaela Albuen VasquezNo ratings yet

- The G-FactorDocument4 pagesThe G-FactorBig AllanNo ratings yet

- G Factor of IntelligenceDocument2 pagesG Factor of IntelligenceElena-Andreea MutNo ratings yet

- Cognitive Psychology and Psychometrictheories of IntelligenceDocument3 pagesCognitive Psychology and Psychometrictheories of IntelligenceMartha Lucía Triviño LuengasNo ratings yet

- Why IQ Tests Don PDFDocument2 pagesWhy IQ Tests Don PDFPhanet HavNo ratings yet

- CFITDocument18 pagesCFITKriti ShettyNo ratings yet

- APPsych Chapter 9 Targets IntelligenceDocument5 pagesAPPsych Chapter 9 Targets IntelligenceDuezAPNo ratings yet

- Human Behavior - Chap 9Document4 pagesHuman Behavior - Chap 9BismahMehdiNo ratings yet

- (Psych) Intelligence HandoutsDocument6 pages(Psych) Intelligence HandoutsAyesha JanelleNo ratings yet

- Social Consequences of Group Differences in Cognitive Ability PDFDocument43 pagesSocial Consequences of Group Differences in Cognitive Ability PDFBautista LasalaNo ratings yet

- What Is Intelligence?Document4 pagesWhat Is Intelligence?Michellene TadleNo ratings yet

- Stanovich ThePsychologist PDFDocument4 pagesStanovich ThePsychologist PDFluistxo2680100% (1)

- Intelligence: Controversy Over Definition: ©john Wiley & Sons, Inc. 2007 Huffman: Psychology in Action (8e)Document28 pagesIntelligence: Controversy Over Definition: ©john Wiley & Sons, Inc. 2007 Huffman: Psychology in Action (8e)anisha batraNo ratings yet

- Intelligence, Artificial Intelligence and Other Forms ofDocument75 pagesIntelligence, Artificial Intelligence and Other Forms ofZoha MerchantNo ratings yet

- B.Ed Psychology Unit 5Document28 pagesB.Ed Psychology Unit 5Shah JehanNo ratings yet

- V Eebrtik4O7C&Ab - Channel Manofallcreation V Hy5T3Snxplu&Ab - Channel JordanbpetersonclipsDocument20 pagesV Eebrtik4O7C&Ab - Channel Manofallcreation V Hy5T3Snxplu&Ab - Channel JordanbpetersonclipsTamo MujiriNo ratings yet

- Intelligence: The Sophisticated Art of Being Smart from the StartFrom EverandIntelligence: The Sophisticated Art of Being Smart from the StartNo ratings yet

- Brain ResearchDocument2 pagesBrain ResearchSary MpoiNo ratings yet

- ALTH106 Week 6 TimDocument2 pagesALTH106 Week 6 TimSophia ANo ratings yet

- Intelligence: The Ultimate Guide to Understanding and Increasing Your Brain SkillsFrom EverandIntelligence: The Ultimate Guide to Understanding and Increasing Your Brain SkillsNo ratings yet

- The Transition of Object To Mental Manipulation: Beyond A Species Specific View of IntelligenceDocument11 pagesThe Transition of Object To Mental Manipulation: Beyond A Species Specific View of Intelligencemafia criminalNo ratings yet

- Analyzing The Nature of IntelligenceDocument2 pagesAnalyzing The Nature of IntelligenceRicardo RomeroNo ratings yet

- How Can We Measure IntelligenceDocument4 pagesHow Can We Measure Intelligenceyahyaelbaroudi01No ratings yet

- Intelligence and IQ: Landmark Issues and Great DebatesDocument7 pagesIntelligence and IQ: Landmark Issues and Great DebatesRaduNo ratings yet

- IntelligenceDocument2 pagesIntelligenceAhmadul HoqNo ratings yet

- Running Head: Reframing Intelligence 1Document8 pagesRunning Head: Reframing Intelligence 1Misha Mathews Bradley BeesonNo ratings yet

- Intelligence: Intelligence Creativity Psychometrics: Tests & Measurements Cognitive ApproachDocument37 pagesIntelligence: Intelligence Creativity Psychometrics: Tests & Measurements Cognitive ApproachPiyush MishraNo ratings yet

- Multiple Intelegence-Howard GardnerDocument9 pagesMultiple Intelegence-Howard GardnerziliciousNo ratings yet

- APMyers3e - Unit 11 - Strive Answer KeyDocument21 pagesAPMyers3e - Unit 11 - Strive Answer KeyRobert LewisNo ratings yet

- Chapter 1 IntellignceDocument26 pagesChapter 1 IntellignceAlyka MachadoNo ratings yet

- Intelligence: Personalities, Traits, and Ways to Work SmarterFrom EverandIntelligence: Personalities, Traits, and Ways to Work SmarterNo ratings yet

- Group 3 Report HardDocument18 pagesGroup 3 Report HardZhelParedesNo ratings yet

- Intelligence: Develop Reason and Emotional Intelligence through Brain TrainingFrom EverandIntelligence: Develop Reason and Emotional Intelligence through Brain TrainingNo ratings yet

- NIH Public Access: Author ManuscriptDocument21 pagesNIH Public Access: Author ManuscriptfandyNo ratings yet

- EJ1354165Document19 pagesEJ1354165Taks RaydricNo ratings yet

- Child Psychology Notes - OCR Psychology A-LevelDocument13 pagesChild Psychology Notes - OCR Psychology A-LevelsamNo ratings yet

- Child Psychology Notes - OCR Psychology A-LevelDocument13 pagesChild Psychology Notes - OCR Psychology A-LevelSam JoeNo ratings yet

- OmniTurn Manual g3Document210 pagesOmniTurn Manual g3CESAR MTZNo ratings yet

- Brochure FinalDocument2 pagesBrochure FinalHanamant HunashikattiNo ratings yet

- He Strange Case of DRDocument8 pagesHe Strange Case of DRveritoNo ratings yet

- Velalar College of Engineering and TechnologyDocument47 pagesVelalar College of Engineering and TechnologyKartheeswari SaravananNo ratings yet

- Aec514 Lecture 1Document33 pagesAec514 Lecture 1Ifeoluwa Segun IyandaNo ratings yet

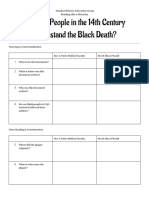

- Understanding The Black DeathDocument2 pagesUnderstanding The Black Deathapi-286657372No ratings yet

- BL Form OoclDocument1 pageBL Form OoclWinda RahmawatiNo ratings yet

- Models of PreventionDocument80 pagesModels of Preventionsunielgowda88% (8)

- Communications Strategy TemplateDocument5 pagesCommunications Strategy TemplateAmal Hameed0% (1)

- Kathy J Abbi Mccoy Kaylee Smith - Frugal Teacher AssignmentDocument4 pagesKathy J Abbi Mccoy Kaylee Smith - Frugal Teacher Assignmentapi-510126964No ratings yet

- Legal Methods Topic: An Overview of Fast Track Courts in IndiaDocument18 pagesLegal Methods Topic: An Overview of Fast Track Courts in IndiaSayiam JainNo ratings yet

- Pyramid Guide n39 Jan-Feb 1979Document12 pagesPyramid Guide n39 Jan-Feb 1979lahodnypetr9No ratings yet

- IntelDocument57 pagesIntelanon_981731217No ratings yet

- Sepsis PCR Diagnostics: Sepsitest Ce IvdDocument4 pagesSepsis PCR Diagnostics: Sepsitest Ce IvdMohammed Khair BashirNo ratings yet

- Wiederhold 2015Document2 pagesWiederhold 2015M. D. EnriquezNo ratings yet

- Chandra Sreenivasulu Mobile: 9606191854: BjectiveDocument4 pagesChandra Sreenivasulu Mobile: 9606191854: BjectiveKavithaNo ratings yet

- Time Allowed Is: City Govenmentof Addis Ababa Yeka Sub-City Education Office English Model Examination For Grade 12Document19 pagesTime Allowed Is: City Govenmentof Addis Ababa Yeka Sub-City Education Office English Model Examination For Grade 12Daniel100% (2)

- Fitting ManualDocument72 pagesFitting Manualayush bindalNo ratings yet

- 03 - Electrical PowerDocument11 pages03 - Electrical Power郝帅No ratings yet

- Sample Thesis For Transportation EngineeringDocument7 pagesSample Thesis For Transportation EngineeringlisathompsonportlandNo ratings yet

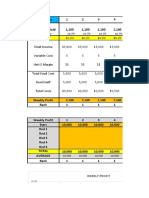

- Restaurant Price Game 2021Document43 pagesRestaurant Price Game 2021Lee JonathanNo ratings yet

- Enthalpy and The Second Law of Thermodynamics: David KeiferDocument5 pagesEnthalpy and The Second Law of Thermodynamics: David KeiferEduardo AndresNo ratings yet

- NMAT Review 2018 Module - PhysicsDocument35 pagesNMAT Review 2018 Module - PhysicsRaf Lin DrawsNo ratings yet

- Case Analysis For TEK280 (Team)Document5 pagesCase Analysis For TEK280 (Team)smartheNo ratings yet

- Manual of Practice Sun Direct V 7.0 Feb 20Document10 pagesManual of Practice Sun Direct V 7.0 Feb 20Charandas KothareNo ratings yet

- Forbidden Lands Legends and Adventurers 5th PrintingDocument40 pagesForbidden Lands Legends and Adventurers 5th PrintingRubens Beraldo PaulicoNo ratings yet

1998generalintelligencefactor PDF

1998generalintelligencefactor PDF

Uploaded by

Delaila Irma Tan CalindasOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

1998generalintelligencefactor PDF

1998generalintelligencefactor PDF

Uploaded by

Delaila Irma Tan CalindasCopyright:

Available Formats

Despite some popular

The General assertions, a single factor

for intelligence, called g,

Intelligence can be measured with IQ

tests and does predict

Factor success in life

by Linda S. Gottfredson

N o subject in psychology has pro-

voked more intense public controversy

downplayed or ignored. This misrepresen-

tation reflects a clash between a deeply

mental tests are often designed to mea-

sure specific domains of cognition—ver-

than the study of human intelligence. felt ideal and a stubborn reality. The ideal, bal fluency, say, or mathematical skill,

From its beginning, research on how implicit in many popular critiques of spatial visualization or memory—people

and why people differ in overall mental intelligence research, is that all people are who do well on one kind of test tend to

ability has fallen prey to political and born equally able and that social inequali- do well on the others, and people who

social agendas that obscure or distort ty results only from the exercise of unjust do poorly generally do so across the

even the most well-established scientific privilege. The reality is that Mother board. This overlap, or intercorrelation,

findings. Journalists, too, often present a Nature is no egalitarian. People are in fact suggests that all such tests measure

view of intelligence research that is unequal in intellectual potential—and some global element of intellectual abil-

exactly the opposite of what most intel- they are born that way, just as they are ity as well as specific cognitive skills. In

ligence experts believe. For these and born with different potentials for height, recent decades, psychologists have

other reasons, public understanding of physical attractiveness, artistic flair, ath- devoted much effort to isolating that

intelligence falls far short of public con- letic prowess and other traits. Although general factor, which is abbreviated g,

cern about it. The IQ experts discussing subsequent experience shapes this poten- from the other aspects of cognitive abili-

their work in the public arena can feel tial, no amount of social engineering can ty gauged in mental tests.

as though they have fallen down the make individuals with widely divergent The statistical extraction of g is per-

rabbit hole into Alice’s Wonderland. mental aptitudes into intellectual equals. formed by a technique called factor

The debate over intelligence and Of course, there are many kinds of analysis. Introduced at the turn of the

intelligence testing focuses on the ques- talent, many kinds of mental ability and century by British psychologist Charles

tion of whether it is useful or meaning- many other aspects of personality and Spearman, factor analysis determines the

ful to evaluate people according to a character that influence a person’s minimum number of underlying dimen-

single major dimension of cognitive chances of happiness and success. The sions necessary to explain a pattern of

competence. Is there indeed a general functional importance of general mental correlations among measurements. A

mental ability we commonly call “intel- ability in everyday life, however, means general factor suffusing all tests is not,

ligence,” and is it important in the prac- that without onerous restrictions on as is sometimes argued, a necessary out-

tical affairs of life? The answer, based on individual liberty, differences in mental come of factor analysis. No general factor

decades of intelligence research, is an competence are likely to result in social has been found in the analysis of per-

unequivocal yes. No matter their form inequality. This gulf between equal sonality tests, for example; instead the

or content, tests of mental skills invari- opportunity and equal outcomes is per- method usually yields at least five dimen-

ably point to the existence of a global haps what pains Americans most about sions (neuroticism, extraversion, consci-

factor that permeates all aspects of cog- the subject of intelligence. The public entiousness, agreeableness and openness

nition. And this factor seems to have intuitively knows what is at stake: when to ideas), each relating to different sub-

considerable influence on a person’s asked to rank personal qualities in order sets of tests. But, as Spearman observed,

practical quality of life. Intelligence as of desirability, people put intelligence a general factor does emerge from analy-

measured by IQ tests is the single most second only to good health. But with a sis of mental ability tests, and leading

effective predictor known of individual more realistic approach to the intellectual psychologists, such as Arthur R. Jensen of

performance at school and on the job. It differences between people, society could the University of California at Berkeley

also predicts many other aspects of well- better accommodate these differences and John B. Carroll of the University of

being, including a person’s chances of and minimize the inequalities they create. North Carolina at Chapel Hill, have con-

divorcing, dropping out of high school, firmed his findings in the decades since.

being unemployed or having illegitimate Extracting g Partly because of this research, most intel-

children. ligence experts now use g as the working

By now the vast majority of intelli- Early in the century-old study of definition of intelligence.

gence researchers take these findings for intelligence, researchers discovered that The general factor explains most

granted. Yet in the press and in public all tests of mental ability ranked individ- differences among individuals in perfor-

debate, the facts are typically dismissed, uals in about the same way. Although mance on diverse mental tests. This is

24 Scientific American Presents Human Intelligence

Copyright 1998 Scientific American, Inc.

BRIDGEMAN ART LIBRARY

Ad Parnassum, by Paul Klee HIERARCHICAL MODEL of intelligence

is akin to a pyramid, with g at the apex;

true regardless of what specific ability a intelligence researchers can statistically other aptitudes are arrayed at successively

test is meant to assess, regardless of the separate the g component of IQ. The abil- lower levels according to their specificity.

test’s manifest content (whether words, ity to isolate g has revolutionized research

numbers or figures) and regardless of the on general intelligence, because it has

way the test is administered (in written allowed investigators to show that the

or oral form, to an individual or to a predictive value of mental tests derives stitutes intelligence in action. Indeed,

group). Tests of specific mental abilities almost entirely from this global factor intelligence can best be described as the

do measure those abilities, but they all rather than from the more specific apti- ability to deal with cognitive complexity.

reflect g to varying degrees as well. Hence, tudes measured by intelligence tests. This description coincides well with

the g factor can be extracted from scores In addition to quantifying individual lay perceptions of intelligence. The g fac-

on any diverse battery of tests. differences, tests of mental abilities have tor is especially important in just the

Conversely, because every mental also offered insight into the meaning of kind of behaviors that people usually

test is “contaminated” by the effects of intelligence in everyday life. Some tests associate with “smarts”: reasoning, prob-

specific mental skills, no single test mea- and test items are known to correlate bet- lem solving, abstract thinking, quick

sures only g. Even the scores from IQ ter with g than others do. In these items learning. And whereas g itself describes

tests—which usually combine about a the “active ingredient” that demands the mental aptitude rather than accumulated

dozen subtests of specific cognitive exercise of g seems to be complexity. knowledge, a person’s store of knowledge

skills—contain some “impurities” that More complex tasks require more mental tends to correspond with his or her g

reflect those narrower skills. For most manipulation, and this manipulation of level, probably because that accumulation

purposes, these impurities make no prac- information—discerning similarities and represents a previous adeptness in learn-

tical difference, and g and IQ can be used inconsistencies, drawing inferences, ing and in understanding new informa-

interchangeably. But if they need to, grasping new concepts and so on—con- tion. The g factor is also the one attribute

The General Intelligence Factor Exploring Intelligence 25

Copyright 1998 Scientific American, Inc.

Matrix Reasoning

1. 2.

A B C D E A B C D E

Number Series Analogies

3. 2, 4, 6, 8, _, _ 7. brother: sister father:

4. 3,6,3,6, _,_ A. child B. mother C. cousin D. friend

8.

LINDA S. GOTTFREDSON

5. 1,5,4,2,6,5, _, _ joke: humor law:

6. 2,4,3,9,4,16, _,_ A. lawyer B. mercy C. courts D. justice

Answers: 1. A; 2. D; 3. 10, 12; 4. 3, 6; 5. 3, 7; 6. 5, 25; 7. B; 8. D

SAMPLE IQ ITEMS resembling those on current tests require in the images, numbers or words. Because they can vary in

the test taker to fill in the empty spaces based on the pattern complexity, such tasks are useful in assessing g level.

that best distinguishes among persons pendent of g (or each other). Further- by-product of one’s opportunities to

considered gifted, average or retarded. more, it is not clear to what extent learn skills and information valued in a

Several decades of factor-analytic Gardner’s intelligences tap personality particular cultural context. True, the

research on mental tests have confirmed a traits or motor skills rather than mental concept of intelligence and the way in

hierarchical model of mental abilities. aptitudes. which individuals are ranked according

The evidence, summarized most effec- Other forms of intelligence have to this criterion could be social artifacts.

tively in Carroll’s 1993 book, Human been proposed; among them, emotional But the fact that g is not specific to any

Cognitive Abilities, puts g at the apex in intelligence and practical intelligence are particular domain of knowledge or men-

this model, with more specific aptitudes perhaps the best known. They are proba- tal skill suggests that g is independent of

arrayed at successively lower levels: the bly amalgams either of intellect and per- cultural content, including beliefs about

so-called group factors, such as verbal sonality or of intellect and informal expe- what intelligence is. And tests of differ-

ability, mathematical reasoning, spatial rience in specific job or life settings, ent social groups reveal the same con-

visualization and memory, are just below respectively. Practical intelligence like tinuum of general intelligence. This

g, and below these are skills that are “street smarts,” for example, seems to observation suggests either that cultures

more dependent on knowledge or experi- consist of the localized knowledge and do not construct g or that they construct

ence, such as the principles and practices know-how developed with untutored the same g. Both conclusions undercut

of a particular job or profession. experience in particular everyday settings the social artifact theory of intelligence.

Some researchers use the term “mul- and activities—the so-called school of Moreover, research on the physiolo-

tiple intelligences” to label these sets of hard knocks. In contrast, general intelli- gy and genetics of g has uncovered bio-

narrow capabilities and achievements. gence is not a form of achievement, logical correlates of this psychological

Psychologist Howard Gardner of Harvard whether local or renowned. Instead the phenomenon. In the past decade, stud-

University, for example, has postulated g factor regulates the rate of learning: it ies by teams of researchers in North

that eight relatively autonomous “intelli- greatly affects the rate of return in knowl- America and Europe have linked several

gences” are exhibited in different edge to instruction and experience but attributes of the brain to general intelli-

domains of achievement. He does not cannot substitute for either. gence. After taking into account gender

dispute the existence of g but treats it as and physical stature, brain size as deter-

a specific factor relevant chiefly to acade- The Biology of g mined by magnetic resonance imaging

mic achievement and to situations that is moderately correlated with IQ (about

resemble those of school. Gardner does Some critics of intelligence research 0.4 on a scale of 0 to 1). So is the speed

not believe that tests can fruitfully mea- maintain that the notion of general of nerve conduction. The brains of

sure his proposed intelligences; without intelligence is illusory: that no such bright people also use less energy during

tests, no one can at present determine global mental capacity exists and that problem solving than do those of their

whether the intelligences are indeed inde- apparent “intelligence” is really just a less able peers. And various qualities of

26 Scientific American Presents Human Intelligence

Copyright 1998 Scientific American, Inc.

brain waves correlate strongly (about 0.5 g is as reliable and global a phenomenon little to do with IQ. Many people still

to 0.7) with IQ: the brain waves of indi- at the neural level as it is at the level of mistakenly believe that social, psycho-

viduals with higher IQs, for example, the complex information processing logical and economic differences among

respond more promptly and consistently required by IQ tests and everyday life. families create lasting and marked differ-

to simple sensory stimuli such as audible The existence of biological corre- ences in IQ. Behavioral geneticists refer

clicks. These observations have led some lates of intelligence does not necessarily to such environmental effects as

investigators to posit that differences in mean that intelligence is dictated by “shared” because they are common to

g result from differences in the speed and genes. Decades of genetics research have siblings who grow up together. Research

efficiency of neural processing. If this shown, however, that people are born has shown that although shared envi-

theory is true, environmental conditions with different hereditary potentials for ronments do have a modest influence

could influence g by modifying brain intelligence and that these genetic on IQ in childhood, their effects dissi-

physiology in some manner. endowments are responsible for much pate by adolescence. The IQs of adopted

Studies of so-called elementary cog- of the variation in mental ability among children, for example, lose all resem-

nitive tasks (ECTs), conducted by Jensen individuals. Last spring an international blance to those of their adoptive family

and others, are bridging the gap between team of scientists headed by Robert members and become more like the IQs

the psychological and the physiological Plomin of the Institute of Psychiatry in of the biological parents they have never

aspects of g. These mental tasks have no London announced the discovery of the known. Such findings suggest that sib-

obvious intellectual content and are so first gene linked to intelligence. Of lings either do not share influential

simple that adults and most children can course, genes have their effects only in aspects of the rearing environment or do

do them accurately in less than a second. interaction with environments, partly not experience them in the same way.

In the most basic reaction-time tests, for by enhancing an individual’s exposure Much behavioral genetics research cur-

example, the subject must react when a or sensitivity to formative experiences. rently focuses on the still mysterious

light goes on by lifting her index finger Differences in general intelligence, processes by which environments make

off a home button and immediately whether measured as IQ or, more accu- members of a household less alike.

depressing a response button. Two mea- rately, as g are both genetic and environ-

surements are taken: the number of mil- mental in origin—just as are all other g on the Job

liseconds between the illumination of psychological traits and attitudes studied

the light and the subject’s release of the so far, including personality, vocational Although the evidence of genetic

home button, which is called decision interests and societal attitudes. This is and physiological correlates of g argues

time, and the number of milliseconds old news among the experts. The experts powerfully for the existence of global

between the subject’s release of the home have, however, been startled by more intelligence, it has not quelled the crit-

button and pressing of the response but- recent discoveries. ics of intelligence testing. These skeptics

ton, which is called movement time. One is that the heritability of IQ argue that even if such a global entity

In this task, movement time seems rises with age—that is to say, the extent exists, it has no intrinsic functional

independent of intelligence, but the deci- to which genetics accounts for differ- value and becomes important only to

sion times of higher-IQ subjects are slight- ences in IQ among individuals increases the extent that people treat it as such:

ly faster than those of people with lower as people get older. Studies comparing for example, by using IQ scores to sort,

IQs. As the tasks are made more complex, identical and fraternal twins, published label and assign students and employ-

correlations between average decision in the past decade by a group led by ees. Such concerns over the proper use

times and IQ increase. These results fur- Thomas J. Bouchard, Jr., of the University of mental tests have prompted a great

ther support the notion that intelligence of Minnesota and other scholars, show deal of research in recent decades. This

equips individuals to deal with com- that about 40 percent of IQ differences research shows that although IQ tests

plexity and that its influence is greater among preschoolers stems from genetic can indeed be misused, they measure a

in complex tasks than in simple ones. differences but that heritability rises to capability that does in fact affect many

The ECT-IQ correlations are compa- 60 percent by adolescence and to 80 kinds of performance and many life out-

rable for all IQ levels, ages, genders and percent by late adulthood. With age, dif- comes, independent of the tests’ inter-

racial-ethnic groups tested. Moreover, ferences among individuals in their pretations or applications. Moreover, the

studies by Philip A. Vernon of the Uni- developed intelligence come to mirror research shows that intelligence tests

versity of Western Ontario and others more closely their genetic differences. It measure the capability equally well for

have shown that the ECT-IQ overlap appears that the effects of environment all native-born English-speaking groups

results almost entirely from the common on intelligence fade rather than grow in the U.S.

g factor in both measures. Reaction times with time. In hindsight, perhaps this If we consider that intelligence

do not reflect differences in motivation should have come as no surprise. Young manifests itself in everyday life as the

or strategy or the tendency of some indi- children have the circumstances of their ability to deal with complexity, then it

viduals to rush through tests and daily lives imposed on them by parents, is easy to see why it has great functional

tasks—that penchant is a personality schools and other agents of society, but or practical importance. Children, for

trait. They actually seem to measure the as people get older they become more example, are regularly exposed to com-

speed with which the brain apprehends, independent and tend to seek out the plex tasks once they begin school.

integrates and evaluates information. life niches that are most congenial to Schooling requires above all that stu-

Research on ECTs and brain physiology their genetic proclivities. dents learn, solve problems and think

has not yet identified the biological A second big surprise for intelli- abstractly. That IQ is quite a good pre-

determinants of this processing speed. gence experts was the discovery that dictor of differences in educational

These studies do suggest, however, that environments shared by siblings have achievement is therefore not surprising.

The General Intelligence Factor Exploring Intelligence 27

Copyright 1998 Scientific American, Inc.

Life High Uphill Keeping Out Yours CORRELATION OF IQ SCORES with

Chances Risk Battle Up Ahead to Lose occupational achievement suggests that

g reflects an ability to deal with cogni-

Very explicit, Written materials, Gathers, infers tive complexity. Scores also correlate with

hands-on plus experience own information

Training some social outcomes (the percentages

Style apply to young white adults in the U.S.).

Slow, simple, Mastery learning, College

supervised hands-on format

ing in the nine specialties studied,

Career Assembler, Clerk, teller, Manager, Attorney, among them infantry, military police

Potential food service, police officer, teacher, chemist,

nurse’s aide machinist, sales accountant executive and medical specialist. Research in the

civilian sector has revealed the same pat-

tern. Furthermore, although the addition

IQ 70 80 90 100 110 120 130 of personality traits such as conscien-

tiousness can help hone the prediction

of job performance, the inclusion of

Population Percentages specific mental aptitudes such as verbal

fluency or mathematical skill rarely does.

Total The predictive value of mental tests in

population 5 20 50 20 5

distribution the work arena stems almost entirely

Out of labor from their measurement of g, and that

force more value rises with the complexity and

than 1 month 22 19 15 14 10 prestige level of the job.

out of year

(men) Half a century of military and civil-

ian research has converged to draw a

Unemployed portrait of occupational opportunity

more than

1 month out 12 10 7 7 2 along the IQ continuum. Individuals in

of year (men) the top 5 percent of the adult IQ distrib-

ution (above IQ 125) can essentially

Divorced in

5 years 21 22 23 15 9 train themselves, and few occupations

are beyond their reach mentally. Persons

Had illegitimate of average IQ (between 90 and 110) are

children 32 17 8 4 2

(women) not competitive for most professional

and executive-level work but are easily

Lives in trained for the bulk of jobs in the

poverty 30 16 6 3 2

American economy. In contrast, adults

Ever in the bottom 5 percent of the IQ distri-

incarcerated 7 7 3 1 0 bution (below 75) are very difficult to

(men) train and are not competitive for any

occupation on the basis of ability.

JOHN MENGEL Ponzi & Weill

Chronic welfare

recipient 31 17 8 2 0 Serious problems in training low-IQ mil-

(mothers) itary recruits during World War II led

High school Congress to ban enlistment from the

55 35 6 0.4 0

dropout lowest 10 percent (below 80) of the pop-

Adapted from Intelligence, Vol. 24, No. 1; January/February 1997

ulation, and no civilian occupation in

modern economies routinely recruits its

When scores on both IQ and standard- military tasks. Similarly, in school set- workers from that range. Current mili-

ized achievement tests in different sub- tings the ratio of learning rates between tary enlistment standards exclude any

jects are averaged over several years, the “fast” and “slow” students is typically individual whose IQ is below about 85.

two averages correlate as highly as dif- five to one. The importance of g in job perfor-

ferent IQ tests from the same individual The scholarly content of many IQ mance, as in schooling, is related to

do. High-ability students also master tests and their strong correlations with complexity. Occupations differ consider-

material at many times the rate of their educational success can give the impres- ably in the complexity of their demands,

low-ability peers. Many investigations sion that g is only a narrow academic and as that complexity rises, higher g

have helped quantify this discrepancy. ability. But general mental ability also levels become a bigger asset and lower g

For example, a 1969 study done for the predicts job performance, and in more levels a bigger handicap. Similarly, every-

U.S. Army by the Human Resources complex jobs it does so better than any day tasks and environments also differ

Research Office found that enlistees in other single personal trait, including significantly in their cognitive complex-

the bottom fifth of the ability distribu- education and experience. The army’s ity. The degree to which a person’s g level

tion required two to six times as many Project A, a seven-year study conducted will come to bear on daily life depends

teaching trials and prompts as did their in the 1980s to improve the recruitment on how much novelty and ambiguity

higher-ability peers to attain minimal and training process, found that general that person’s everyday tasks and sur-

proficiency in rifle assembly, monitoring mental ability correlated strongly with roundings present and how much con-

signals, combat plotting and other basic both technical proficiency and soldier- tinual learning, judgment and decision

28 Scientific American Presents Human Intelligence

Copyright 1998 Scientific American, Inc.

making they require. As gamblers, stance yet studied is so deeply implicated apply to populations around the world,

employers and bankers know, even mar- in the nexus of bad social outcomes— to the extremely advantaged and disad-

ginal differences in rates of return will poverty, welfare, illegitimacy and educa- vantaged in the developing world or, for

yield big gains—or losses—over time. tional failure—that entraps many low-IQ that matter, to people living under

Hence, even small differences in g among individuals and families. Even the effects restrictive political regimes. No one

people can exert large, cumulative influ- of family background pale in comparison knows what research under different cir-

ences across social and economic life. with the influence of IQ. As shown most cumstances, in different eras or with dif-

In my own work, I have tried to syn- recently by Charles Murray of the Amer- ferent populations might reveal.

thesize the many lines of research that ican Enterprise Institute in Washington, But we do know that, wherever free-

document the influence of IQ on life out- D.C., the divergence in many outcomes dom and technology advance, life is an

comes. As the illustration on the opposite associated with IQ level is almost as wide uphill battle for people who are below

page shows, the odds of various kinds of among siblings from the same household average in proficiency at learning, solv-

achievement and social pathology change as it is for strangers of comparable IQ ing problems and mastering complexity.

systematically across the IQ continuum, levels. And siblings differ a lot in IQ—on We also know that the trajectories of

from borderline mentally retarded average, by 12 points, compared with 17 mental development are not easily

(below 70) to intellectually gifted (above for random strangers. deflected. Individual IQ levels tend to

130). Even in comparisons of those of An IQ of 75 is perhaps the most remain unchanged from adolescence

somewhat below average (between 76 important threshold in modern life. At onward, and despite strenuous efforts

and 90) and somewhat above average that level, a person’s chances of master- over the past half a century, attempts to

(between 111 and 125) IQs, the odds for ing the elementary school curriculum raise g permanently through adoption

outcomes having social consequence are are only 50–50, and he or she will have or educational means have failed. If

stacked against the less able. Young men a hard time functioning independently there is a reliable, ethical way to raise or

somewhat below average in general without considerable social support. equalize levels of g, no one has found it.

mental ability, for example, are more Individuals and families who are only Some investigators have suggested

likely to be unemployed than men somewhat below average in IQ face risks that biological interventions, such as

somewhat above average. The lower-IQ of social pathology that, while lower, are dietary supplements of vitamins, may be

woman is four times more likely to bear still significant enough to jeopardize more effective than educational ones in

illegitimate children than the higher-IQ their well-being. High-IQ individuals raising g levels. This approach is based in

woman; among mothers, she is eight may lack the resolve, character or good part on the assumption that improved

times more likely to become a chronic fortune to capitalize on their intellectual nutrition has caused the puzzling rise in

welfare recipient. People somewhat capabilities, but socioeconomic success average levels of both IQ and height in

below average are 88 times more likely in the postindustrial information age is the developed world during this century.

to drop out of high school, seven times theirs to lose. Scientists are still hotly debating whether

more likely to be jailed and five times the gains in IQ actually reflect a rise in g

more likely as adults to live in poverty What Is versus What Could Be or are caused instead by changes in less

than people of somewhat above-average critical, specific mental skills. Whatever

IQ. Below-average individuals are 50 The foregoing findings on g’s effects the truth may be, the differences in men-

percent more likely to be divorced than have been drawn from studies conducted tal ability among individuals remain,

those in the above-average category. under a limited range of circumstances— and the conflict between equal opportu-

These odds diverge even more namely, the social, economic and politi- nity and equal outcome persists. Only

sharply for people with bigger gaps in IQ, cal conditions prevailing now and in by accepting these hard truths about

and the mechanisms by which IQ creates recent decades in developed countries intelligence will society find humane

this divergence are not yet clearly under- that allow considerable personal freedom. solutions to the problems posed by the

stood. But no other single trait or circum- It is not clear whether these findings variations in general mental ability. SA

About the Author

LINDA S. GOTTFREDSON is professor gence shapes vocational choice and self-

of educational studies at the University of perception. Gottfredson also organized

Delaware, where she has been since 1986, the 1994 treatise “Mainstream Science on

and co-directs the Delaware–Johns Hopkins Intelligence,” an editorial with more than

Project for the Study of Intelligence and 50 signatories that first appeared in the

Society. She trained as a sociologist, and Wall Street Journal in response to the con-

her earliest work focused on career devel- troversy surrounding publication of The

opment. “I wasn’t interested in intelli- Bell Curve. Gottfredson is the mother of

COURTESY OF LINDA S. GOTTFREDSON

gence per se,” Gottfredson says. “But it identical twins—a “mere coincidence,”

suffused everything I was studying in my she says, “that’s always made me think

attempts to understand who was getting more about the nature and nurture of

ahead.” This “discovery of the obvious,” intelligence.” The girls, now 16, follow

as she puts it, became the focus of her Gottfredson’s Peace Corps experience of

research. In the mid-1980s, while at Johns the 1970s by joining her each summer for

Hopkins University, she published several volunteer construction work in the vil-

influential articles describing how intelli- lages of Nicaragua.

The General Intelligence Factor Exploring Intelligence 29

Copyright 1998 Scientific American, Inc.

30 Scientific American Presents Human Intelligence

Copyright 1998 Scientific American, Inc.

You might also like

- TL Design Manual - Rev0.5Document64 pagesTL Design Manual - Rev0.5Syed Ahsan Ali Sherazi100% (2)

- Spectrophotometric Method For Simultaneous Estimation of Levofloxacin and Ornidazole in Tablet Dosage FormDocument14 pagesSpectrophotometric Method For Simultaneous Estimation of Levofloxacin and Ornidazole in Tablet Dosage FormSumit Sahu0% (1)

- 2011 Instant Expert IntelligenceDocument9 pages2011 Instant Expert IntelligenceJamie RobinsonNo ratings yet

- Umbrella Term Mind Reason Plan Solve Problems Abstractly Language Learn Creativity Personality Character Knowledge WisdomDocument7 pagesUmbrella Term Mind Reason Plan Solve Problems Abstractly Language Learn Creativity Personality Character Knowledge WisdomAVINANDANKUMARNo ratings yet

- Deary Penke Johnson 2010 - Neuroscience of Intelligence ReviewDocument12 pagesDeary Penke Johnson 2010 - Neuroscience of Intelligence ReviewAndres CorzoNo ratings yet

- Intelligence: Theories about Psychology, Signs, and StupidityFrom EverandIntelligence: Theories about Psychology, Signs, and StupidityNo ratings yet

- Intelligence: Sta. Teresa CollegeDocument5 pagesIntelligence: Sta. Teresa Collegeaudree d. aldayNo ratings yet

- (1987) Suggested Two Different FormsDocument6 pages(1987) Suggested Two Different FormsAllan DiversonNo ratings yet

- Psychology 101 INTELLIGENCEDocument17 pagesPsychology 101 INTELLIGENCEAEDRIELYN PICHAYNo ratings yet

- 2 Schooling Makes You Smarter PDFDocument12 pages2 Schooling Makes You Smarter PDFvalensalNo ratings yet

- Text 4.1 Intelligence: What Is It?Document7 pagesText 4.1 Intelligence: What Is It?NURULHIKMAH NAMIKAZENo ratings yet

- Cognition (Contd.) Aptitude and IntelligenceDocument13 pagesCognition (Contd.) Aptitude and IntelligenceMajid JamilNo ratings yet

- IntelligenceDocument18 pagesIntelligencetasfia2829No ratings yet

- RSPM ReportDocument16 pagesRSPM ReportRia ManochaNo ratings yet

- Intelligence LectureDocument32 pagesIntelligence LectureHina SikanderNo ratings yet

- IQ (The Intelligence Quotient) : Louis D Matzel Bruno SauceDocument10 pagesIQ (The Intelligence Quotient) : Louis D Matzel Bruno SauceHouho DzNo ratings yet

- EducationDocument145 pagesEducationVictor ColivertNo ratings yet

- Chapter 9 Summary NotesDocument6 pagesChapter 9 Summary Notesshiela badiangNo ratings yet

- IQ & Creativity: Jalalabad, CantonmentDocument19 pagesIQ & Creativity: Jalalabad, CantonmentDipto PaulNo ratings yet

- Proposition 1 - DebateDocument3 pagesProposition 1 - DebateLydia CLNo ratings yet

- LDRSHP IntelligenceDocument13 pagesLDRSHP IntelligenceMazin HayderNo ratings yet

- Intellegance 9: DR Mohammad A.S. KamilDocument21 pagesIntellegance 9: DR Mohammad A.S. Kamilمصطفى رسول هاديNo ratings yet

- 12 Psychology Theory of IntelligenceDocument3 pages12 Psychology Theory of IntelligenceBerryNo ratings yet

- Intelligence TestingDocument4 pagesIntelligence Testinghina FatimaNo ratings yet

- Title-: Intelligence and It's Various ExplanationsDocument15 pagesTitle-: Intelligence and It's Various ExplanationsShreya BasuNo ratings yet

- College of Education: Lesson 9Document4 pagesCollege of Education: Lesson 9Mikaela Albuen VasquezNo ratings yet

- The G-FactorDocument4 pagesThe G-FactorBig AllanNo ratings yet

- G Factor of IntelligenceDocument2 pagesG Factor of IntelligenceElena-Andreea MutNo ratings yet

- Cognitive Psychology and Psychometrictheories of IntelligenceDocument3 pagesCognitive Psychology and Psychometrictheories of IntelligenceMartha Lucía Triviño LuengasNo ratings yet

- Why IQ Tests Don PDFDocument2 pagesWhy IQ Tests Don PDFPhanet HavNo ratings yet

- CFITDocument18 pagesCFITKriti ShettyNo ratings yet

- APPsych Chapter 9 Targets IntelligenceDocument5 pagesAPPsych Chapter 9 Targets IntelligenceDuezAPNo ratings yet

- Human Behavior - Chap 9Document4 pagesHuman Behavior - Chap 9BismahMehdiNo ratings yet

- (Psych) Intelligence HandoutsDocument6 pages(Psych) Intelligence HandoutsAyesha JanelleNo ratings yet

- Social Consequences of Group Differences in Cognitive Ability PDFDocument43 pagesSocial Consequences of Group Differences in Cognitive Ability PDFBautista LasalaNo ratings yet

- What Is Intelligence?Document4 pagesWhat Is Intelligence?Michellene TadleNo ratings yet

- Stanovich ThePsychologist PDFDocument4 pagesStanovich ThePsychologist PDFluistxo2680100% (1)

- Intelligence: Controversy Over Definition: ©john Wiley & Sons, Inc. 2007 Huffman: Psychology in Action (8e)Document28 pagesIntelligence: Controversy Over Definition: ©john Wiley & Sons, Inc. 2007 Huffman: Psychology in Action (8e)anisha batraNo ratings yet

- Intelligence, Artificial Intelligence and Other Forms ofDocument75 pagesIntelligence, Artificial Intelligence and Other Forms ofZoha MerchantNo ratings yet

- B.Ed Psychology Unit 5Document28 pagesB.Ed Psychology Unit 5Shah JehanNo ratings yet

- V Eebrtik4O7C&Ab - Channel Manofallcreation V Hy5T3Snxplu&Ab - Channel JordanbpetersonclipsDocument20 pagesV Eebrtik4O7C&Ab - Channel Manofallcreation V Hy5T3Snxplu&Ab - Channel JordanbpetersonclipsTamo MujiriNo ratings yet

- Intelligence: The Sophisticated Art of Being Smart from the StartFrom EverandIntelligence: The Sophisticated Art of Being Smart from the StartNo ratings yet

- Brain ResearchDocument2 pagesBrain ResearchSary MpoiNo ratings yet

- ALTH106 Week 6 TimDocument2 pagesALTH106 Week 6 TimSophia ANo ratings yet

- Intelligence: The Ultimate Guide to Understanding and Increasing Your Brain SkillsFrom EverandIntelligence: The Ultimate Guide to Understanding and Increasing Your Brain SkillsNo ratings yet

- The Transition of Object To Mental Manipulation: Beyond A Species Specific View of IntelligenceDocument11 pagesThe Transition of Object To Mental Manipulation: Beyond A Species Specific View of Intelligencemafia criminalNo ratings yet

- Analyzing The Nature of IntelligenceDocument2 pagesAnalyzing The Nature of IntelligenceRicardo RomeroNo ratings yet

- How Can We Measure IntelligenceDocument4 pagesHow Can We Measure Intelligenceyahyaelbaroudi01No ratings yet

- Intelligence and IQ: Landmark Issues and Great DebatesDocument7 pagesIntelligence and IQ: Landmark Issues and Great DebatesRaduNo ratings yet

- IntelligenceDocument2 pagesIntelligenceAhmadul HoqNo ratings yet

- Running Head: Reframing Intelligence 1Document8 pagesRunning Head: Reframing Intelligence 1Misha Mathews Bradley BeesonNo ratings yet

- Intelligence: Intelligence Creativity Psychometrics: Tests & Measurements Cognitive ApproachDocument37 pagesIntelligence: Intelligence Creativity Psychometrics: Tests & Measurements Cognitive ApproachPiyush MishraNo ratings yet

- Multiple Intelegence-Howard GardnerDocument9 pagesMultiple Intelegence-Howard GardnerziliciousNo ratings yet

- APMyers3e - Unit 11 - Strive Answer KeyDocument21 pagesAPMyers3e - Unit 11 - Strive Answer KeyRobert LewisNo ratings yet

- Chapter 1 IntellignceDocument26 pagesChapter 1 IntellignceAlyka MachadoNo ratings yet

- Intelligence: Personalities, Traits, and Ways to Work SmarterFrom EverandIntelligence: Personalities, Traits, and Ways to Work SmarterNo ratings yet

- Group 3 Report HardDocument18 pagesGroup 3 Report HardZhelParedesNo ratings yet

- Intelligence: Develop Reason and Emotional Intelligence through Brain TrainingFrom EverandIntelligence: Develop Reason and Emotional Intelligence through Brain TrainingNo ratings yet

- NIH Public Access: Author ManuscriptDocument21 pagesNIH Public Access: Author ManuscriptfandyNo ratings yet

- EJ1354165Document19 pagesEJ1354165Taks RaydricNo ratings yet

- Child Psychology Notes - OCR Psychology A-LevelDocument13 pagesChild Psychology Notes - OCR Psychology A-LevelsamNo ratings yet

- Child Psychology Notes - OCR Psychology A-LevelDocument13 pagesChild Psychology Notes - OCR Psychology A-LevelSam JoeNo ratings yet

- OmniTurn Manual g3Document210 pagesOmniTurn Manual g3CESAR MTZNo ratings yet

- Brochure FinalDocument2 pagesBrochure FinalHanamant HunashikattiNo ratings yet

- He Strange Case of DRDocument8 pagesHe Strange Case of DRveritoNo ratings yet

- Velalar College of Engineering and TechnologyDocument47 pagesVelalar College of Engineering and TechnologyKartheeswari SaravananNo ratings yet

- Aec514 Lecture 1Document33 pagesAec514 Lecture 1Ifeoluwa Segun IyandaNo ratings yet

- Understanding The Black DeathDocument2 pagesUnderstanding The Black Deathapi-286657372No ratings yet

- BL Form OoclDocument1 pageBL Form OoclWinda RahmawatiNo ratings yet

- Models of PreventionDocument80 pagesModels of Preventionsunielgowda88% (8)

- Communications Strategy TemplateDocument5 pagesCommunications Strategy TemplateAmal Hameed0% (1)

- Kathy J Abbi Mccoy Kaylee Smith - Frugal Teacher AssignmentDocument4 pagesKathy J Abbi Mccoy Kaylee Smith - Frugal Teacher Assignmentapi-510126964No ratings yet

- Legal Methods Topic: An Overview of Fast Track Courts in IndiaDocument18 pagesLegal Methods Topic: An Overview of Fast Track Courts in IndiaSayiam JainNo ratings yet

- Pyramid Guide n39 Jan-Feb 1979Document12 pagesPyramid Guide n39 Jan-Feb 1979lahodnypetr9No ratings yet

- IntelDocument57 pagesIntelanon_981731217No ratings yet

- Sepsis PCR Diagnostics: Sepsitest Ce IvdDocument4 pagesSepsis PCR Diagnostics: Sepsitest Ce IvdMohammed Khair BashirNo ratings yet

- Wiederhold 2015Document2 pagesWiederhold 2015M. D. EnriquezNo ratings yet

- Chandra Sreenivasulu Mobile: 9606191854: BjectiveDocument4 pagesChandra Sreenivasulu Mobile: 9606191854: BjectiveKavithaNo ratings yet

- Time Allowed Is: City Govenmentof Addis Ababa Yeka Sub-City Education Office English Model Examination For Grade 12Document19 pagesTime Allowed Is: City Govenmentof Addis Ababa Yeka Sub-City Education Office English Model Examination For Grade 12Daniel100% (2)

- Fitting ManualDocument72 pagesFitting Manualayush bindalNo ratings yet

- 03 - Electrical PowerDocument11 pages03 - Electrical Power郝帅No ratings yet

- Sample Thesis For Transportation EngineeringDocument7 pagesSample Thesis For Transportation EngineeringlisathompsonportlandNo ratings yet

- Restaurant Price Game 2021Document43 pagesRestaurant Price Game 2021Lee JonathanNo ratings yet

- Enthalpy and The Second Law of Thermodynamics: David KeiferDocument5 pagesEnthalpy and The Second Law of Thermodynamics: David KeiferEduardo AndresNo ratings yet

- NMAT Review 2018 Module - PhysicsDocument35 pagesNMAT Review 2018 Module - PhysicsRaf Lin DrawsNo ratings yet

- Case Analysis For TEK280 (Team)Document5 pagesCase Analysis For TEK280 (Team)smartheNo ratings yet

- Manual of Practice Sun Direct V 7.0 Feb 20Document10 pagesManual of Practice Sun Direct V 7.0 Feb 20Charandas KothareNo ratings yet

- Forbidden Lands Legends and Adventurers 5th PrintingDocument40 pagesForbidden Lands Legends and Adventurers 5th PrintingRubens Beraldo PaulicoNo ratings yet