Professional Documents

Culture Documents

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

20 viewsParmenides

Parmenides

Uploaded by

Reyvincent V PaloParmenides of Elea was an ancient Greek philosopher considered the founder of metaphysics and a pivotal figure in philosophy. He wrote a poem arguing that reality is unified and unchanging, challenging previous systems. The poem had three sections: the Proem describing a journey, Reality making claims about what exists, and Opinion describing the world of change and motion but denoting it as mere opinion. The central question is how to reconcile the claims of Reality with the contradictory account in Opinion.

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as DOCX, PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

You might also like

- Philosophy 101: From Plato and Socrates to Ethics and Metaphysics, an Essential Primer on the History of ThoughtFrom EverandPhilosophy 101: From Plato and Socrates to Ethics and Metaphysics, an Essential Primer on the History of ThoughtRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (36)

- Parminides Basic InfoDocument2 pagesParminides Basic InfoMark SangoyoNo ratings yet

- Ammonius in Isagog Intro PDFDocument12 pagesAmmonius in Isagog Intro PDFbachmp7No ratings yet

- The Eleatic SchoolDocument14 pagesThe Eleatic Schoolhajra0% (1)

- Lecture#2 1Document17 pagesLecture#2 1Ульяна КасымбековаNo ratings yet

- Ancient PhilosophersDocument20 pagesAncient PhilosophersElaissa MoniqueNo ratings yet

- Parmenides (C. 485 BCE) Was A Greek Philosopher From The Colony of Elea inDocument2 pagesParmenides (C. 485 BCE) Was A Greek Philosopher From The Colony of Elea indave1997No ratings yet

- Ancient Greek PhilosophersDocument6 pagesAncient Greek PhilosophersChrizzer CapaladNo ratings yet

- Development of The Eleatic SchoolDocument5 pagesDevelopment of The Eleatic SchoolJennifer AranillaNo ratings yet

- Socrates: PlatoDocument4 pagesSocrates: PlatolenerNo ratings yet

- 15 Early Greek PhilosophersDocument9 pages15 Early Greek Philosophersmeri janNo ratings yet

- Philosopher Profiles ParmenidesDocument5 pagesPhilosopher Profiles ParmenidesBently JohnsonNo ratings yet

- Aristotle On The Ancient Theologians - John A. Palmer (Apeiron, 2000)Document26 pagesAristotle On The Ancient Theologians - John A. Palmer (Apeiron, 2000)Đoàn DuyNo ratings yet

- Ancient Greek and Roman PhilosophersDocument14 pagesAncient Greek and Roman PhilosophersKai GrenadeNo ratings yet

- Ancient Tradition Concerning TheDocument9 pagesAncient Tradition Concerning TheCARLOS PONCENo ratings yet

- The First Philosophers NotesDocument7 pagesThe First Philosophers NotesAlex Mark PateyNo ratings yet

- Favorinus: Favorinus of Arelate (C. 80 - C. 160 AD) Was An Intersex RomanDocument4 pagesFavorinus: Favorinus of Arelate (C. 80 - C. 160 AD) Was An Intersex RomancrppypolNo ratings yet

- From Ta Metá Ta Physiká To Metaphysics Piotr Jaroszyński: Espíritu LXII (2013) Nº 145Document25 pagesFrom Ta Metá Ta Physiká To Metaphysics Piotr Jaroszyński: Espíritu LXII (2013) Nº 145Berk ÖzcangillerNo ratings yet

- Winborn Kidd Astudillo PDFDocument1 pageWinborn Kidd Astudillo PDFWinborn Kidd AstudilloNo ratings yet

- Synoptic EssayDocument6 pagesSynoptic EssayGABRO DEACONNo ratings yet

- Toledo Group Activity Infographics EthicsDocument3 pagesToledo Group Activity Infographics EthicsJillian Gwen ToledoNo ratings yet

- Abigail D. Mariano Bsed 4A EnglishDocument3 pagesAbigail D. Mariano Bsed 4A EnglishAbigail MarianoNo ratings yet

- Omeara MetaphysicsDocument7 pagesOmeara MetaphysicsblavskaNo ratings yet

- Understanding The Self: ASSIGNMENT #4 - Sept. 5, 2019Document4 pagesUnderstanding The Self: ASSIGNMENT #4 - Sept. 5, 2019Jonah Garcia TevesNo ratings yet

- Theorizing About Philosophos or The Love For Sophos/wisdomDocument16 pagesTheorizing About Philosophos or The Love For Sophos/wisdomulrichNo ratings yet

- Dominic - Omeara@unifr - CH: T T M L ADocument17 pagesDominic - Omeara@unifr - CH: T T M L AMikhail SilianNo ratings yet

- AssignmentDocument3 pagesAssignmentVladimir LegisNo ratings yet

- Some Disputed Questions in The Interpretation of ParmenidesDocument13 pagesSome Disputed Questions in The Interpretation of ParmenidesNikola Tatalović100% (1)

- Pre-Socratic PhilosophyDocument11 pagesPre-Socratic PhilosophyBen EdwardsNo ratings yet

- Thales of Miletus-: Everything Is Made of Water. It Was Thales Cosmological Doctrine That The Water Was TheDocument2 pagesThales of Miletus-: Everything Is Made of Water. It Was Thales Cosmological Doctrine That The Water Was Theaugustine abellanaNo ratings yet

- PLATO Docx-1Document3 pagesPLATO Docx-1granada.carldavid1No ratings yet

- Ancient Philo ReviewerDocument18 pagesAncient Philo ReviewerGarbo TrickNo ratings yet

- Ancient Philosophy (Essay)Document12 pagesAncient Philosophy (Essay)Julia MNo ratings yet

- Imp Commentators SorabjiDocument67 pagesImp Commentators SorabjiPablo Diaz StariNo ratings yet

- Philosophy and contributionsVANESSAMARTINDocument5 pagesPhilosophy and contributionsVANESSAMARTINVince BulayogNo ratings yet

- Plato Family PDFDocument40 pagesPlato Family PDFDelos NourseiNo ratings yet

- Zeno of EleaDocument1 pageZeno of Elealelismay_06100% (1)

- Lesson 1. Introduction To Philo ModifedDocument28 pagesLesson 1. Introduction To Philo ModifedIra Jesus Yapching Jr.No ratings yet

- Endress (1995) PDFDocument41 pagesEndress (1995) PDFLuciano A.No ratings yet

- Ancient Greek PhilosophersDocument50 pagesAncient Greek PhilosophersJor Garcia100% (1)

- Iamblichus' Egyptian Neoplatonic Theology in de MysteriisDocument42 pagesIamblichus' Egyptian Neoplatonic Theology in de MysteriisalexandertaNo ratings yet

- Parmenides-Mourelatos-Route-Review in Journal of Ancient Philosophy-EnglishDocument10 pagesParmenides-Mourelatos-Route-Review in Journal of Ancient Philosophy-EnglishgfvilaNo ratings yet

- Beginners Guide To Logic: Submitted by Rexiel Val M. Adolfo Ryan Christian Anora Lanz Dela Cruz Keith ReveloDocument52 pagesBeginners Guide To Logic: Submitted by Rexiel Val M. Adolfo Ryan Christian Anora Lanz Dela Cruz Keith ReveloRez AdolfoNo ratings yet

- Plato: For Other Uses, See andDocument2 pagesPlato: For Other Uses, See andMilanka IzgarevicNo ratings yet

- Plato - Uts Ab-Comm1a - Chris Ardinazo - Joshua AlbaniaDocument13 pagesPlato - Uts Ab-Comm1a - Chris Ardinazo - Joshua AlbaniaDiyes StudiosNo ratings yet

- The Beginnings of Doing PhilosophyDocument11 pagesThe Beginnings of Doing PhilosophyAnita SaguidNo ratings yet

- Top 10 Ancient Greek PhilosophersDocument9 pagesTop 10 Ancient Greek PhilosophersAngelo Rivera ElleveraNo ratings yet

- Philosophical Concerns Across The Centuries - g1Document21 pagesPhilosophical Concerns Across The Centuries - g1fnestudiosNo ratings yet

- Lecture 3. Ancient Greec-Roman Philosophy, February 2016 2Document65 pagesLecture 3. Ancient Greec-Roman Philosophy, February 2016 2Алдияр БериккалиевNo ratings yet

- Ancient Western Philosophy OverviewDocument7 pagesAncient Western Philosophy OverviewMMHCNo ratings yet

- Topic No.03-Early Ancient PhilosphersDocument16 pagesTopic No.03-Early Ancient PhilosphersSaif Ur RehmanNo ratings yet

- Ancient Philosophy Final Output.....Document6 pagesAncient Philosophy Final Output.....Nujer RobarNo ratings yet

- 8utDgP1sTxmXWXzF0jtI - Turning Points From Plato - Two Lectures - Plato and Aristotle - Plato and The PresocraticsDocument20 pages8utDgP1sTxmXWXzF0jtI - Turning Points From Plato - Two Lectures - Plato and Aristotle - Plato and The PresocraticsEduardo Gutiérrez GutiérrezNo ratings yet

- Ancient Ideas On The Nature of MatterDocument14 pagesAncient Ideas On The Nature of MatterEd TapuroNo ratings yet

- Ancientphilo SolisDocument17 pagesAncientphilo SolisJerick Mercado RosalNo ratings yet

- Aristotle Thepoetics PDFDocument60 pagesAristotle Thepoetics PDFhemantNo ratings yet

- History of Buckling of ColumnDocument10 pagesHistory of Buckling of ColumnSorin Viorel CrainicNo ratings yet

- DP Barte: DesignsDocument1 pageDP Barte: DesignsJjammppong AcostaNo ratings yet

- Servo SystemsDocument17 pagesServo SystemsAzeem .kNo ratings yet

- 02 LRDocument11 pages02 LRDebashish DekaNo ratings yet

- Nondestructive Testing of Pavements and Backcalculation of Moduli: Third Volume, ASTM STP 137.5, S. DDocument15 pagesNondestructive Testing of Pavements and Backcalculation of Moduli: Third Volume, ASTM STP 137.5, S. DMahdi SardarNo ratings yet

- 110-10 Terminal ApplicationDocument16 pages110-10 Terminal ApplicationAnonymous L7XrxpeI1zNo ratings yet

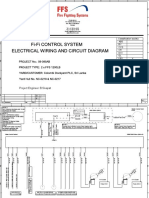

- Electrical Wiring and Circuit Diagram Fi-Fi Control SystemDocument16 pagesElectrical Wiring and Circuit Diagram Fi-Fi Control SystemDamithaNo ratings yet

- Mobile CodesDocument353 pagesMobile CodesManav GuptaNo ratings yet

- BoeingDocument9 pagesBoeingnavala_pra0% (1)

- Spectroscopy Part A1 PDFDocument385 pagesSpectroscopy Part A1 PDFMarciomatiascosta100% (1)

- University of CalcuttaDocument94 pagesUniversity of CalcuttaAmlan SarkarNo ratings yet

- Experiment No. 1Document7 pagesExperiment No. 1Judith LacapNo ratings yet

- Zoom Timetable BFC KahutaDocument5 pagesZoom Timetable BFC KahutaYumna ArOojNo ratings yet

- Another AMSI-Bypass PaperDocument19 pagesAnother AMSI-Bypass PaperHangup9313No ratings yet

- How To Bypass The Windows 11 TPM 2.0 RequirementDocument1 pageHow To Bypass The Windows 11 TPM 2.0 Requirementdaniel100% (1)

- VNT Brochure NewDocument5 pagesVNT Brochure Newda vin ciNo ratings yet

- Pov Nori Apr2007Document31 pagesPov Nori Apr2007DMRNo ratings yet

- PFD Asam Benzoat - Noor Wahyu & NurulDocument1 pagePFD Asam Benzoat - Noor Wahyu & NurulFahmi ZakariaNo ratings yet

- Avro Quick GuideDocument28 pagesAvro Quick Guidersreddy.ch5919No ratings yet

- Lecture 4Document63 pagesLecture 4InfragNo ratings yet

- Labels Independent Heating BMW E60 Sedan 47750Document2 pagesLabels Independent Heating BMW E60 Sedan 47750Kifah ZaidanNo ratings yet

- Pipe Flow: Philosophy, Sizing, and Simulation: Presenter: RizaldiDocument55 pagesPipe Flow: Philosophy, Sizing, and Simulation: Presenter: RizaldiRizaldi RizNo ratings yet

- Envelope Theorem and Identities (Good)Document17 pagesEnvelope Theorem and Identities (Good)sadatnfsNo ratings yet

- Biokerosene From Coconut and PalmDocument8 pagesBiokerosene From Coconut and PalmNestor Armando Marin SolanoNo ratings yet

- Eng Pcdmis 2021.1 Core ManualDocument3,285 pagesEng Pcdmis 2021.1 Core ManualGuest User100% (1)

- Flow and LevellingDocument2 pagesFlow and LevellingKrushna KakdeNo ratings yet

- New Approach To The Characterisation of Petroleum Mixtures Used in The Modelling of Separation ProcessesDocument14 pagesNew Approach To The Characterisation of Petroleum Mixtures Used in The Modelling of Separation ProcessesHerbert SenzanoNo ratings yet

- Baking Ambient Occlusion (Transfer Map Method)Document11 pagesBaking Ambient Occlusion (Transfer Map Method)angelbladecobusNo ratings yet

- Mechanics Midterm Exam 2023 - Answer KeyDocument4 pagesMechanics Midterm Exam 2023 - Answer KeySovann_LongNo ratings yet

- Axial Flow CompressorDocument18 pagesAxial Flow Compressorankit100% (1)

Parmenides

Parmenides

Uploaded by

Reyvincent V Palo0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

20 views1 pageParmenides of Elea was an ancient Greek philosopher considered the founder of metaphysics and a pivotal figure in philosophy. He wrote a poem arguing that reality is unified and unchanging, challenging previous systems. The poem had three sections: the Proem describing a journey, Reality making claims about what exists, and Opinion describing the world of change and motion but denoting it as mere opinion. The central question is how to reconcile the claims of Reality with the contradictory account in Opinion.

Original Description:

Story of Parmenides

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

DOCX, PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentParmenides of Elea was an ancient Greek philosopher considered the founder of metaphysics and a pivotal figure in philosophy. He wrote a poem arguing that reality is unified and unchanging, challenging previous systems. The poem had three sections: the Proem describing a journey, Reality making claims about what exists, and Opinion describing the world of change and motion but denoting it as mere opinion. The central question is how to reconcile the claims of Reality with the contradictory account in Opinion.

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as DOCX, PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Download as docx, pdf, or txt

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

20 views1 pageParmenides

Parmenides

Uploaded by

Reyvincent V PaloParmenides of Elea was an ancient Greek philosopher considered the founder of metaphysics and a pivotal figure in philosophy. He wrote a poem arguing that reality is unified and unchanging, challenging previous systems. The poem had three sections: the Proem describing a journey, Reality making claims about what exists, and Opinion describing the world of change and motion but denoting it as mere opinion. The central question is how to reconcile the claims of Reality with the contradictory account in Opinion.

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as DOCX, PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Download as docx, pdf, or txt

You are on page 1of 1

PARMENIDES

PHILOSOPHY: Parmenides of Elea was

a Presocratic Greek philosopher. As the first philosopher to

inquire into the nature of existence itself, he is incontrovertibly

credited as the “Father of Metaphysics.” As the first to employ

deductive, a prioriarguments to justify his claims, he competes

with Aristotle for the title “Father of Logic.” He is also commonly

thought of as the founder of the “Eleatic School” of thought—a

philosophical label ascribed to Presocratics who purportedly

argued that reality is in some sense a unified and unchanging singular entity. This has often been

understood to mean there is just one thing in all of existence. In light of this questionable

interpretation, Parmenides has traditionally been viewed as a pivotal figure in the history of

philosophy: one who challenged the physical systems of his predecessors and set forth for his

successors the metaphysical criteria any successful system must meet. Other thinkers, also commonly

thought of as Eleatics, include: Zeno of Elea, Melissus of Samos, and (more

controversially) Xenophanes of Colophon.

Parmenides’ only written work is a poem entitled, supposedly, but likely erroneously, On Nature.Only

a limited number of “fragments” (more precisely, quotations by later authors) of his poem are still in

existence, which have traditionally been assigned to three main sections—Proem, Reality(Alétheia),

and Opinion (Doxa). The Proem (prelude) features a young man on a cosmic (perhaps spiritual)

journey in search of enlightenment, expressed in traditional Greek religious motifs and geography.

This is followed by the central, most philosophically-oriented section (Reality). Here, Parmenides

positively endorses certain epistemic guidelines for inquiry, which he then uses to argue for his

famous metaphysical claims—that “what is” (whatever is referred to by the word “this”) cannot be in

motion, change, come-to-be, perish, lack uniformity, and so forth. The final section (Opinion)

concludes the poem with a theogonical and cosmogonical account of the world, which paradoxically

employs the very phenomena (motion, change, and so forth) that Reality

seems to have denied. Furthermore, despite making apparently true claims (for example, the moon

gets its light from the sun), the account offered in Opinion is supposed to be representative of the

mistaken “opinions of mortals,” and thus is to be rejected on some level.

All three sections of the poem seem particularly contrived to yield a cohesive and unified thesis.

However, discerning exactly what that thesis is supposed to be has proven a vexing, perennial

problem since ancient times. Even Plato expressed reservations as to whether Parmenides’ “noble

depth” could be understood at all—and Plato possessed Parmenides’ entire poem, a blessing denied to

modern scholars. Although there are many important philological and philosophical questions

surrounding Parmenides’ poem, the central question for Parmenidean studies is addressing how the

positively-endorsed, radical conclusions of Reality can be adequately reconciled with the seemingly

contradictory cosmological account Parmenides rejects in Opinion. The primary focus of this article is

to provide the reader with sufficient background to appreciate this interpretative problem and the

difficulties with its proposed solutions.

You might also like

- Philosophy 101: From Plato and Socrates to Ethics and Metaphysics, an Essential Primer on the History of ThoughtFrom EverandPhilosophy 101: From Plato and Socrates to Ethics and Metaphysics, an Essential Primer on the History of ThoughtRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (36)

- Parminides Basic InfoDocument2 pagesParminides Basic InfoMark SangoyoNo ratings yet

- Ammonius in Isagog Intro PDFDocument12 pagesAmmonius in Isagog Intro PDFbachmp7No ratings yet

- The Eleatic SchoolDocument14 pagesThe Eleatic Schoolhajra0% (1)

- Lecture#2 1Document17 pagesLecture#2 1Ульяна КасымбековаNo ratings yet

- Ancient PhilosophersDocument20 pagesAncient PhilosophersElaissa MoniqueNo ratings yet

- Parmenides (C. 485 BCE) Was A Greek Philosopher From The Colony of Elea inDocument2 pagesParmenides (C. 485 BCE) Was A Greek Philosopher From The Colony of Elea indave1997No ratings yet

- Ancient Greek PhilosophersDocument6 pagesAncient Greek PhilosophersChrizzer CapaladNo ratings yet

- Development of The Eleatic SchoolDocument5 pagesDevelopment of The Eleatic SchoolJennifer AranillaNo ratings yet

- Socrates: PlatoDocument4 pagesSocrates: PlatolenerNo ratings yet

- 15 Early Greek PhilosophersDocument9 pages15 Early Greek Philosophersmeri janNo ratings yet

- Philosopher Profiles ParmenidesDocument5 pagesPhilosopher Profiles ParmenidesBently JohnsonNo ratings yet

- Aristotle On The Ancient Theologians - John A. Palmer (Apeiron, 2000)Document26 pagesAristotle On The Ancient Theologians - John A. Palmer (Apeiron, 2000)Đoàn DuyNo ratings yet

- Ancient Greek and Roman PhilosophersDocument14 pagesAncient Greek and Roman PhilosophersKai GrenadeNo ratings yet

- Ancient Tradition Concerning TheDocument9 pagesAncient Tradition Concerning TheCARLOS PONCENo ratings yet

- The First Philosophers NotesDocument7 pagesThe First Philosophers NotesAlex Mark PateyNo ratings yet

- Favorinus: Favorinus of Arelate (C. 80 - C. 160 AD) Was An Intersex RomanDocument4 pagesFavorinus: Favorinus of Arelate (C. 80 - C. 160 AD) Was An Intersex RomancrppypolNo ratings yet

- From Ta Metá Ta Physiká To Metaphysics Piotr Jaroszyński: Espíritu LXII (2013) Nº 145Document25 pagesFrom Ta Metá Ta Physiká To Metaphysics Piotr Jaroszyński: Espíritu LXII (2013) Nº 145Berk ÖzcangillerNo ratings yet

- Winborn Kidd Astudillo PDFDocument1 pageWinborn Kidd Astudillo PDFWinborn Kidd AstudilloNo ratings yet

- Synoptic EssayDocument6 pagesSynoptic EssayGABRO DEACONNo ratings yet

- Toledo Group Activity Infographics EthicsDocument3 pagesToledo Group Activity Infographics EthicsJillian Gwen ToledoNo ratings yet

- Abigail D. Mariano Bsed 4A EnglishDocument3 pagesAbigail D. Mariano Bsed 4A EnglishAbigail MarianoNo ratings yet

- Omeara MetaphysicsDocument7 pagesOmeara MetaphysicsblavskaNo ratings yet

- Understanding The Self: ASSIGNMENT #4 - Sept. 5, 2019Document4 pagesUnderstanding The Self: ASSIGNMENT #4 - Sept. 5, 2019Jonah Garcia TevesNo ratings yet

- Theorizing About Philosophos or The Love For Sophos/wisdomDocument16 pagesTheorizing About Philosophos or The Love For Sophos/wisdomulrichNo ratings yet

- Dominic - Omeara@unifr - CH: T T M L ADocument17 pagesDominic - Omeara@unifr - CH: T T M L AMikhail SilianNo ratings yet

- AssignmentDocument3 pagesAssignmentVladimir LegisNo ratings yet

- Some Disputed Questions in The Interpretation of ParmenidesDocument13 pagesSome Disputed Questions in The Interpretation of ParmenidesNikola Tatalović100% (1)

- Pre-Socratic PhilosophyDocument11 pagesPre-Socratic PhilosophyBen EdwardsNo ratings yet

- Thales of Miletus-: Everything Is Made of Water. It Was Thales Cosmological Doctrine That The Water Was TheDocument2 pagesThales of Miletus-: Everything Is Made of Water. It Was Thales Cosmological Doctrine That The Water Was Theaugustine abellanaNo ratings yet

- PLATO Docx-1Document3 pagesPLATO Docx-1granada.carldavid1No ratings yet

- Ancient Philo ReviewerDocument18 pagesAncient Philo ReviewerGarbo TrickNo ratings yet

- Ancient Philosophy (Essay)Document12 pagesAncient Philosophy (Essay)Julia MNo ratings yet

- Imp Commentators SorabjiDocument67 pagesImp Commentators SorabjiPablo Diaz StariNo ratings yet

- Philosophy and contributionsVANESSAMARTINDocument5 pagesPhilosophy and contributionsVANESSAMARTINVince BulayogNo ratings yet

- Plato Family PDFDocument40 pagesPlato Family PDFDelos NourseiNo ratings yet

- Zeno of EleaDocument1 pageZeno of Elealelismay_06100% (1)

- Lesson 1. Introduction To Philo ModifedDocument28 pagesLesson 1. Introduction To Philo ModifedIra Jesus Yapching Jr.No ratings yet

- Endress (1995) PDFDocument41 pagesEndress (1995) PDFLuciano A.No ratings yet

- Ancient Greek PhilosophersDocument50 pagesAncient Greek PhilosophersJor Garcia100% (1)

- Iamblichus' Egyptian Neoplatonic Theology in de MysteriisDocument42 pagesIamblichus' Egyptian Neoplatonic Theology in de MysteriisalexandertaNo ratings yet

- Parmenides-Mourelatos-Route-Review in Journal of Ancient Philosophy-EnglishDocument10 pagesParmenides-Mourelatos-Route-Review in Journal of Ancient Philosophy-EnglishgfvilaNo ratings yet

- Beginners Guide To Logic: Submitted by Rexiel Val M. Adolfo Ryan Christian Anora Lanz Dela Cruz Keith ReveloDocument52 pagesBeginners Guide To Logic: Submitted by Rexiel Val M. Adolfo Ryan Christian Anora Lanz Dela Cruz Keith ReveloRez AdolfoNo ratings yet

- Plato: For Other Uses, See andDocument2 pagesPlato: For Other Uses, See andMilanka IzgarevicNo ratings yet

- Plato - Uts Ab-Comm1a - Chris Ardinazo - Joshua AlbaniaDocument13 pagesPlato - Uts Ab-Comm1a - Chris Ardinazo - Joshua AlbaniaDiyes StudiosNo ratings yet

- The Beginnings of Doing PhilosophyDocument11 pagesThe Beginnings of Doing PhilosophyAnita SaguidNo ratings yet

- Top 10 Ancient Greek PhilosophersDocument9 pagesTop 10 Ancient Greek PhilosophersAngelo Rivera ElleveraNo ratings yet

- Philosophical Concerns Across The Centuries - g1Document21 pagesPhilosophical Concerns Across The Centuries - g1fnestudiosNo ratings yet

- Lecture 3. Ancient Greec-Roman Philosophy, February 2016 2Document65 pagesLecture 3. Ancient Greec-Roman Philosophy, February 2016 2Алдияр БериккалиевNo ratings yet

- Ancient Western Philosophy OverviewDocument7 pagesAncient Western Philosophy OverviewMMHCNo ratings yet

- Topic No.03-Early Ancient PhilosphersDocument16 pagesTopic No.03-Early Ancient PhilosphersSaif Ur RehmanNo ratings yet

- Ancient Philosophy Final Output.....Document6 pagesAncient Philosophy Final Output.....Nujer RobarNo ratings yet

- 8utDgP1sTxmXWXzF0jtI - Turning Points From Plato - Two Lectures - Plato and Aristotle - Plato and The PresocraticsDocument20 pages8utDgP1sTxmXWXzF0jtI - Turning Points From Plato - Two Lectures - Plato and Aristotle - Plato and The PresocraticsEduardo Gutiérrez GutiérrezNo ratings yet

- Ancient Ideas On The Nature of MatterDocument14 pagesAncient Ideas On The Nature of MatterEd TapuroNo ratings yet

- Ancientphilo SolisDocument17 pagesAncientphilo SolisJerick Mercado RosalNo ratings yet

- Aristotle Thepoetics PDFDocument60 pagesAristotle Thepoetics PDFhemantNo ratings yet

- History of Buckling of ColumnDocument10 pagesHistory of Buckling of ColumnSorin Viorel CrainicNo ratings yet

- DP Barte: DesignsDocument1 pageDP Barte: DesignsJjammppong AcostaNo ratings yet

- Servo SystemsDocument17 pagesServo SystemsAzeem .kNo ratings yet

- 02 LRDocument11 pages02 LRDebashish DekaNo ratings yet

- Nondestructive Testing of Pavements and Backcalculation of Moduli: Third Volume, ASTM STP 137.5, S. DDocument15 pagesNondestructive Testing of Pavements and Backcalculation of Moduli: Third Volume, ASTM STP 137.5, S. DMahdi SardarNo ratings yet

- 110-10 Terminal ApplicationDocument16 pages110-10 Terminal ApplicationAnonymous L7XrxpeI1zNo ratings yet

- Electrical Wiring and Circuit Diagram Fi-Fi Control SystemDocument16 pagesElectrical Wiring and Circuit Diagram Fi-Fi Control SystemDamithaNo ratings yet

- Mobile CodesDocument353 pagesMobile CodesManav GuptaNo ratings yet

- BoeingDocument9 pagesBoeingnavala_pra0% (1)

- Spectroscopy Part A1 PDFDocument385 pagesSpectroscopy Part A1 PDFMarciomatiascosta100% (1)

- University of CalcuttaDocument94 pagesUniversity of CalcuttaAmlan SarkarNo ratings yet

- Experiment No. 1Document7 pagesExperiment No. 1Judith LacapNo ratings yet

- Zoom Timetable BFC KahutaDocument5 pagesZoom Timetable BFC KahutaYumna ArOojNo ratings yet

- Another AMSI-Bypass PaperDocument19 pagesAnother AMSI-Bypass PaperHangup9313No ratings yet

- How To Bypass The Windows 11 TPM 2.0 RequirementDocument1 pageHow To Bypass The Windows 11 TPM 2.0 Requirementdaniel100% (1)

- VNT Brochure NewDocument5 pagesVNT Brochure Newda vin ciNo ratings yet

- Pov Nori Apr2007Document31 pagesPov Nori Apr2007DMRNo ratings yet

- PFD Asam Benzoat - Noor Wahyu & NurulDocument1 pagePFD Asam Benzoat - Noor Wahyu & NurulFahmi ZakariaNo ratings yet

- Avro Quick GuideDocument28 pagesAvro Quick Guidersreddy.ch5919No ratings yet

- Lecture 4Document63 pagesLecture 4InfragNo ratings yet

- Labels Independent Heating BMW E60 Sedan 47750Document2 pagesLabels Independent Heating BMW E60 Sedan 47750Kifah ZaidanNo ratings yet

- Pipe Flow: Philosophy, Sizing, and Simulation: Presenter: RizaldiDocument55 pagesPipe Flow: Philosophy, Sizing, and Simulation: Presenter: RizaldiRizaldi RizNo ratings yet

- Envelope Theorem and Identities (Good)Document17 pagesEnvelope Theorem and Identities (Good)sadatnfsNo ratings yet

- Biokerosene From Coconut and PalmDocument8 pagesBiokerosene From Coconut and PalmNestor Armando Marin SolanoNo ratings yet

- Eng Pcdmis 2021.1 Core ManualDocument3,285 pagesEng Pcdmis 2021.1 Core ManualGuest User100% (1)

- Flow and LevellingDocument2 pagesFlow and LevellingKrushna KakdeNo ratings yet

- New Approach To The Characterisation of Petroleum Mixtures Used in The Modelling of Separation ProcessesDocument14 pagesNew Approach To The Characterisation of Petroleum Mixtures Used in The Modelling of Separation ProcessesHerbert SenzanoNo ratings yet

- Baking Ambient Occlusion (Transfer Map Method)Document11 pagesBaking Ambient Occlusion (Transfer Map Method)angelbladecobusNo ratings yet

- Mechanics Midterm Exam 2023 - Answer KeyDocument4 pagesMechanics Midterm Exam 2023 - Answer KeySovann_LongNo ratings yet

- Axial Flow CompressorDocument18 pagesAxial Flow Compressorankit100% (1)