Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Association Between Pregnancy and Perinatal Outcomes Among Women With Epilepsy

Association Between Pregnancy and Perinatal Outcomes Among Women With Epilepsy

Uploaded by

Qinthara MuftiCopyright:

Available Formats

You might also like

- Nurse ExamDocument17 pagesNurse ExamRn nadeen100% (2)

- Nej Mo A 1414838Document10 pagesNej Mo A 1414838anggiNo ratings yet

- Predictive Value of The sFlt-1:PlGF Ratio in Women With Suspected PreeclampsiaDocument10 pagesPredictive Value of The sFlt-1:PlGF Ratio in Women With Suspected PreeclampsiaIgnacio Quiroz JerezNo ratings yet

- Aspirin in The Prevention of Preeclampsia in High Risk WomenDocument11 pagesAspirin in The Prevention of Preeclampsia in High Risk WomenSemir MehovićNo ratings yet

- Does Use of Low-Molecular-Weight Heparin During Pregnancy Influence The Risk of Prolonged Labor: A Population-Based Cohort StudyDocument17 pagesDoes Use of Low-Molecular-Weight Heparin During Pregnancy Influence The Risk of Prolonged Labor: A Population-Based Cohort StudyKris AdinataNo ratings yet

- Anxiety During Pregnancy and Preeclampsia: A Case-Control StudyDocument7 pagesAnxiety During Pregnancy and Preeclampsia: A Case-Control StudyCek GuevaraNo ratings yet

- Aspirina PDFDocument11 pagesAspirina PDFmajosbptNo ratings yet

- RiskfactorretainedplacentaDocument9 pagesRiskfactorretainedplacentaDONNYNo ratings yet

- Association Between Hypertensive Disorders of Pregnancy and Later Risk of CardiomyopathyDocument8 pagesAssociation Between Hypertensive Disorders of Pregnancy and Later Risk of CardiomyopathyPujiyono SuwadiNo ratings yet

- Ner Enberg 2017Document7 pagesNer Enberg 2017Ruben Dario Choque CutipaNo ratings yet

- Articles: BackgroundDocument13 pagesArticles: BackgroundDayannaPintoNo ratings yet

- Prediction of Recurrent Preeclampsia Using First-Trimester Uterine Artery DopplerDocument6 pagesPrediction of Recurrent Preeclampsia Using First-Trimester Uterine Artery Dopplerganesh reddyNo ratings yet

- Quadrivalent HPV Vaccination and The Risk of Adverse Pregnancy OutcomesDocument11 pagesQuadrivalent HPV Vaccination and The Risk of Adverse Pregnancy OutcomesRastia AlimmattabrinaNo ratings yet

- New England Journal Medicine: The ofDocument9 pagesNew England Journal Medicine: The ofIrmagian PaleonNo ratings yet

- Antiseizure Medication Use During Pregnancy and Risk of ASD and ADHD in ChildrenDocument10 pagesAntiseizure Medication Use During Pregnancy and Risk of ASD and ADHD in Childrenmhegan07No ratings yet

- Selected Pregnancy and Perinatal Outcomes of Patients With and Without A Previous Placenta AccreteDocument2 pagesSelected Pregnancy and Perinatal Outcomes of Patients With and Without A Previous Placenta AccreteMuhammad IkbarNo ratings yet

- Kew 043Document8 pagesKew 043Firdaus Septhy ArdhyanNo ratings yet

- Joi 150159Document10 pagesJoi 150159siti hazard aldinaNo ratings yet

- General Perinatal Medicine: Oral Presentation at Breakfast 1 - Obstetrics and Labour Reference: A2092SADocument1 pageGeneral Perinatal Medicine: Oral Presentation at Breakfast 1 - Obstetrics and Labour Reference: A2092SAElva Diany SyamsudinNo ratings yet

- Jamaneurology BJRK 2022 Oi 220027 1656444956.23113Document10 pagesJamaneurology BJRK 2022 Oi 220027 1656444956.23113cikun solihatNo ratings yet

- New England Journal Medicine: The ofDocument10 pagesNew England Journal Medicine: The ofTiffany Rachma PutriNo ratings yet

- Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand - 2013 - SKR Stad - A Randomized Controlled Trial of Third Trimester Routine Ultrasound in ADocument8 pagesActa Obstet Gynecol Scand - 2013 - SKR Stad - A Randomized Controlled Trial of Third Trimester Routine Ultrasound in ADayang fatwarrniNo ratings yet

- Prevention of Preeclampsia With Aspirin: Liona - Poon@cuhk - Edu.hkDocument12 pagesPrevention of Preeclampsia With Aspirin: Liona - Poon@cuhk - Edu.hkranggaNo ratings yet

- Labour Dystocia: Risk Factors and Consequences For Mother and InfantDocument86 pagesLabour Dystocia: Risk Factors and Consequences For Mother and Infantproject rakornasNo ratings yet

- Articol TSADocument8 pagesArticol TSAFlorinaDanilaNo ratings yet

- 33873-Article Text-121761-1-10-20170831Document6 pages33873-Article Text-121761-1-10-20170831AnggaNo ratings yet

- First-Trimester Pregnancy Exposure To Venlafaxine or Duloxetine and Risk of Major Congenital Malformations: A Systematic ReviewDocument5 pagesFirst-Trimester Pregnancy Exposure To Venlafaxine or Duloxetine and Risk of Major Congenital Malformations: A Systematic Reviewjose luisNo ratings yet

- Anxiety During Pregnancy and Preeclampsia - A Case-Control StudyDocument9 pagesAnxiety During Pregnancy and Preeclampsia - A Case-Control StudyJOHN CAMILO GARCIA URIBENo ratings yet

- Aust NZ J Obst Gynaeco - 2022 - Silveira - Placenta Accreta Spectrum We Can Do BetterDocument7 pagesAust NZ J Obst Gynaeco - 2022 - Silveira - Placenta Accreta Spectrum We Can Do BetterDrFeelgood WolfslandNo ratings yet

- Draft Proof HiDocument27 pagesDraft Proof Hiqwq kjkjNo ratings yet

- Obstetric Outcomes in Pregnant Women With Seizure Disorder: A Hospital-Based, Longitudinal StudyDocument16 pagesObstetric Outcomes in Pregnant Women With Seizure Disorder: A Hospital-Based, Longitudinal Studyniluh putu erikawatiNo ratings yet

- Acetaminophen Use During Pregnancy, Behavioral Problems, and Hyperkinetic DisordersDocument8 pagesAcetaminophen Use During Pregnancy, Behavioral Problems, and Hyperkinetic DisordersAnn DahngNo ratings yet

- Cesarean Scar Defect: A Prospective Study On Risk Factors: GynecologyDocument8 pagesCesarean Scar Defect: A Prospective Study On Risk Factors: Gynecologynuphie_nuphNo ratings yet

- Etiology and Management Therapy EpilepsyDocument6 pagesEtiology and Management Therapy Epilepsyduwik indahsariNo ratings yet

- Httpbitly wsPcoIDocument6 pagesHttpbitly wsPcoIHamdah RidhakaNo ratings yet

- Prenatal Exposure To Antiseizure Medications and Risk of Epilepsy in Children of Mothers With EpilepsyDocument13 pagesPrenatal Exposure To Antiseizure Medications and Risk of Epilepsy in Children of Mothers With Epilepsyyuly.gomezNo ratings yet

- Association of Biochemical Markers With The Severity of Pre EclampsiaDocument7 pagesAssociation of Biochemical Markers With The Severity of Pre EclampsiaFer OrnelasNo ratings yet

- 29 Sumatriptan RecomendadoDocument2 pages29 Sumatriptan RecomendadoJUAN GARCIANo ratings yet

- 11 Hal 558Document4 pages11 Hal 558Aditya SanjayaNo ratings yet

- Chakravarty 2005Document8 pagesChakravarty 2005Sergio Henrique O. SantosNo ratings yet

- 10 1001@jamapsychiatry 2020 2453Document10 pages10 1001@jamapsychiatry 2020 2453Kassandra González BNo ratings yet

- Hipertensão e DM Na Gestação - Consequencia Exposição Ruido OcupacionalDocument9 pagesHipertensão e DM Na Gestação - Consequencia Exposição Ruido OcupacionalnilfacioNo ratings yet

- Heavy Prenatal Alcohol Exposure and Obstetric and Birth2023Document8 pagesHeavy Prenatal Alcohol Exposure and Obstetric and Birth2023pau.reccNo ratings yet

- Yoa 8230Document7 pagesYoa 8230FortuneNo ratings yet

- Fetal Heart Defects and Measures of Cerebral Size: Objectives Study DesignDocument8 pagesFetal Heart Defects and Measures of Cerebral Size: Objectives Study DesignAdrian KhomanNo ratings yet

- SLE in Pregnancy MedicationDocument9 pagesSLE in Pregnancy MedicationCindy AgustinNo ratings yet

- 2021 Article 1541Document6 pages2021 Article 1541bintangNo ratings yet

- A Comprehensive Analysis of Adverse ObstetricDocument7 pagesA Comprehensive Analysis of Adverse Obstetricagustin OrtizNo ratings yet

- Prevention of Preeclampsia With AspirinDocument15 pagesPrevention of Preeclampsia With AspirinDownload FilmNo ratings yet

- Role of Low Dose AspirinDocument11 pagesRole of Low Dose AspirinYudha GanesaNo ratings yet

- Jurnal CohortDocument21 pagesJurnal CohortAstri Anindita UtomoNo ratings yet

- Antipsychotic Use in Pregnancy and The Risk For Congenital MalformationsDocument9 pagesAntipsychotic Use in Pregnancy and The Risk For Congenital MalformationsRirin WinataNo ratings yet

- Good18.Prenatally Diagnosed Vasa Previa A.30Document9 pagesGood18.Prenatally Diagnosed Vasa Previa A.30wije0% (1)

- 1 s2.0 S0002937822007281 MainDocument9 pages1 s2.0 S0002937822007281 MainkrisnawatiNo ratings yet

- Video 12 PDFDocument5 pagesVideo 12 PDFAndreas NatanNo ratings yet

- Asthma in Pregnancy - Matthew C.H. Rohn, BS, and Laura Felder, MDDocument8 pagesAsthma in Pregnancy - Matthew C.H. Rohn, BS, and Laura Felder, MDFQFerdianNo ratings yet

- MidwiferyDocument8 pagesMidwiferyRiyanti Ardiyana SariNo ratings yet

- 10 3233@hab-180359Document7 pages10 3233@hab-180359Sergio Henrique O. SantosNo ratings yet

- Avitanrg RG RDocument2 pagesAvitanrg RG RPrasetio Kristianto BudionoNo ratings yet

- 5BJPCBS201005.195D20Holanda20et - Al .2C202019 PDFDocument15 pages5BJPCBS201005.195D20Holanda20et - Al .2C202019 PDFputri vinia /ilove cuteNo ratings yet

- Diabetes in Children and Adolescents: A Guide to Diagnosis and ManagementFrom EverandDiabetes in Children and Adolescents: A Guide to Diagnosis and ManagementNo ratings yet

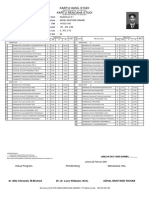

- Kartu Hasil Studi Kartu Rencana StudiDocument2 pagesKartu Hasil Studi Kartu Rencana StudiQinthara MuftiNo ratings yet

- Kjim 2016 350Document8 pagesKjim 2016 350Qinthara MuftiNo ratings yet

- DafpusDocument3 pagesDafpusQinthara MuftiNo ratings yet

- Pembimbing Tugas Koas Bedah RSUP Persahabatan Periode 26 Agustus S.D. 2 November 2019Document2 pagesPembimbing Tugas Koas Bedah RSUP Persahabatan Periode 26 Agustus S.D. 2 November 2019Qinthara MuftiNo ratings yet

- "What Are The Effects of Moderate Drinking On Stroke Risk?": Continuing Medical EducationDocument13 pages"What Are The Effects of Moderate Drinking On Stroke Risk?": Continuing Medical EducationQinthara MuftiNo ratings yet

- OUTPUTDocument1 pageOUTPUTQinthara MuftiNo ratings yet

- Tanya Catering ServiceDocument6 pagesTanya Catering ServiceQinthara MuftiNo ratings yet

- Chest X-Ray: Oleh: Diana Octavina Preseptor: Dr. Moh. Rizal Syafe'i, SP.B-KBDDocument46 pagesChest X-Ray: Oleh: Diana Octavina Preseptor: Dr. Moh. Rizal Syafe'i, SP.B-KBDDiana OCtavinaNo ratings yet

- 19 Daftar PustakaDocument2 pages19 Daftar PustakahfniayuNo ratings yet

- FWA Prepayment Review Records Request: InstructionsDocument7 pagesFWA Prepayment Review Records Request: Instructionsabdulla.mho23No ratings yet

- Concept MapDocument3 pagesConcept Mapphelenaphie menodiado panlilioNo ratings yet

- Role of Homoeopathy in Psychological Disorders: January 2020Document6 pagesRole of Homoeopathy in Psychological Disorders: January 2020Madhu Ronda100% (1)

- @MBS - MedicalBooksStore 2018 Depression, 3rd EditionDocument150 pages@MBS - MedicalBooksStore 2018 Depression, 3rd EditionRIJANTONo ratings yet

- Facial Nerve ParalysisDocument36 pagesFacial Nerve ParalysisSylvia Diamond100% (1)

- EBP 2 Minggu PenelitianDocument23 pagesEBP 2 Minggu PenelitianMuhammad MulyadiNo ratings yet

- JSommers ONLDocument171 pagesJSommers ONLTopaz CompanyNo ratings yet

- BPQ Questionnaire PDFDocument4 pagesBPQ Questionnaire PDFAymen DabboussiNo ratings yet

- Soal No.1 Bedah DigestifDocument11 pagesSoal No.1 Bedah DigestifRaniPradnyaSwariNo ratings yet

- Veterinary Clinic Design For Earth Centre, SierraDocument22 pagesVeterinary Clinic Design For Earth Centre, SierraThamir A. HijaziNo ratings yet

- Kuliah Respirologi Anak: Divisi Respirologi Departemen Ilmu Kesehatan Anak FK Undip / Rsup DR Kariadi SemarangDocument114 pagesKuliah Respirologi Anak: Divisi Respirologi Departemen Ilmu Kesehatan Anak FK Undip / Rsup DR Kariadi SemarangLailatuz ZakiyahNo ratings yet

- Prometric-MOH PageDocument22 pagesPrometric-MOH Pageprabha.s198784No ratings yet

- RENCANA OPERASI OK IBS ORTHOPAEDI DAN TRAUMATOLOGI OKTOBER 3rdWEEKDocument1 pageRENCANA OPERASI OK IBS ORTHOPAEDI DAN TRAUMATOLOGI OKTOBER 3rdWEEKjemierudyanNo ratings yet

- Cold Stress PDFDocument2 pagesCold Stress PDFfriends_nalla100% (1)

- Wound ManagementDocument33 pagesWound Managementdr.yogaNo ratings yet

- Overview of Mucocutaneous Symptom ComplexDocument5 pagesOverview of Mucocutaneous Symptom ComplexDaphne Jo ValmonteNo ratings yet

- Food Allergy Vs Food Intolerance 1684503076Document33 pagesFood Allergy Vs Food Intolerance 1684503076Kevin AlexNo ratings yet

- Product Development Pipeline - FebruaryDocument4 pagesProduct Development Pipeline - FebruaryCebin VargheseNo ratings yet

- Home Care RN Skills ChecklistDocument2 pagesHome Care RN Skills ChecklistGloryJaneNo ratings yet

- Stunting DR AmanDocument63 pagesStunting DR AmantotoksaptantoNo ratings yet

- Filipino Family Physician 2022 60 Pages 23 29Document7 pagesFilipino Family Physician 2022 60 Pages 23 29Pia PalaciosNo ratings yet

- Oral Hygiene Index - OHI-: Jurusan Kedokteran Gigi Universitas Jenderal SoedirmanDocument55 pagesOral Hygiene Index - OHI-: Jurusan Kedokteran Gigi Universitas Jenderal SoedirmanachandrariniNo ratings yet

- Auras Epilépticas: Clasificación, Fisiopatología, Utilidad Práctica, Diagnóstico Diferencial y ControversiasDocument7 pagesAuras Epilépticas: Clasificación, Fisiopatología, Utilidad Práctica, Diagnóstico Diferencial y ControversiasMartinAnteparraNo ratings yet

- Disaster Nursing SAS Sesion 10Document8 pagesDisaster Nursing SAS Sesion 10Niceniadas CaraballeNo ratings yet

- Failed Spinal Anesthesia PDFDocument2 pagesFailed Spinal Anesthesia PDFShamim100% (1)

- Basic Clinical SkillsDocument4 pagesBasic Clinical Skillsbijuiyer5557No ratings yet

- Cam CMD 2022 Presentation SepDocument156 pagesCam CMD 2022 Presentation SepLeBron JamesNo ratings yet

Association Between Pregnancy and Perinatal Outcomes Among Women With Epilepsy

Association Between Pregnancy and Perinatal Outcomes Among Women With Epilepsy

Uploaded by

Qinthara MuftiOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Association Between Pregnancy and Perinatal Outcomes Among Women With Epilepsy

Association Between Pregnancy and Perinatal Outcomes Among Women With Epilepsy

Uploaded by

Qinthara MuftiCopyright:

Available Formats

Research

JAMA Neurology | Original Investigation

Association Between Pregnancy and Perinatal

Outcomes Among Women With Epilepsy

Neda Razaz, PhD; Torbjörn Tomson, MD; Anna-Karin Wikström, MD, PhD; Sven Cnattingius, MD, PhD

Supplemental content

IMPORTANCE To date, few attempts have been made to examine associations between

exposure to maternal epilepsy with or without antiepileptic drug (AED) therapy and

pregnancy and perinatal outcomes.

OBJECTIVES To investigate associations between epilepsy in pregnancy and risks of

pregnancy and perinatal outcomes as well as whether use of AEDs influenced risks.

DESIGN, SETTING, AND PARTICIPANTS A population-based cohort study was conducted on all

singleton births at 22 or more completed gestational weeks in Sweden from 1997 through

2011; of these, 1 424 279 were included in the sample. Information on AED exposure was

available in the subset of offspring from July 1, 2005, to December 31, 2011. Data analysis was

performed from October 1, 2016, to February 15, 2017.

MAIN OUTCOMES AND MEASURES Pregnancy, delivery, and perinatal outcomes. Multivariable

Poisson log-linear regression was used to estimate adjusted risk ratios (aRRs) and 95% CIs,

after adjusting for maternal age, country of origin, educational level, cohabitation with a

partner, height, early pregnancy body mass index, smoking, year of delivery, maternal

pregestational diabetes, hypertension, and psychiatric disorders.

RESULTS Of the 1 429 652 births included in the sample, 5373 births were in 3586 women

with epilepsy; mean (SD) age at first delivery of the epilepsy cohort was 30.54 (5.18) years.

Compared with pregnancies of women without epilepsy, women with epilepsy were at

increased risks of adverse pregnancy and delivery outcomes, including preeclampsia (aRR

1.24; 95% CI, 1.07-1.43), infection (aRR, 1.85; 95% CI, 1.43-2.29), placental abruption (aRR,

1.68; 95% CI, 1.18-2.38), induction (aRR, 1.31; 95% CI, 1.21-1.40), elective cesarean section

(aRR, 1.58; 95% CI, 1.45-1.71), and emergency cesarean section (aRR, 1.09; 95% CI, 1.00-1.20).

Infants of mothers with epilepsy were at increased risks of stillbirth (aRR, 1.55; 95% CI,

1.05-2.30), having both medically indicated (aRR, 1.24; 95% CI, 1.08-1.43) and spontaneous

(aRR, 1.34; 95% CI, 1.20-1.53) preterm birth, being small for gestational age at birth (aRR, 1.25;

95% CI, 1.13-1.30), and having neonatal infections (aRR, 1.42; 95% CI, 1.17-1.73), any congenital

malformation (aRR, 1.48; 95% CI, 1.35-1.62), major malformations (aRR, 1.61; 95% CI,

1.43-1.81), asphyxia-related complications (aRR, 1.75; 95% CI, 1.26-2.42), Apgar score of 4 to 6

at 5 minutes (aRR, 1.34; 95% CI, 1.03-1.76), Apgar score of 0 to 3 at 5 minutes (aRR, 2.42; 95%

CI, 1.62-3.61), neonatal hypoglycemia (aRR, 1.53; 95% CI, 1.34-1.75), and respiratory distress

syndrome (aRR, 1.48; 95% CI, 1.30-1.68) compared with infants of unaffected women. In

Author Affiliations: Clinical

women with epilepsy, using AEDs during pregnancy did not increase the risks of pregnancy Epidemiology Unit, Department of

and perinatal complications, except for a higher rate of induction of labor (aRR, 1.30; 95% CI, Medicine Solna, Karolinska University

1.10-1.55). Hospital, Karolinska Institutet,

Stockholm, Sweden (Razaz,

Cnattingius); Department of Clinical

CONCLUSIONS AND RELEVANCE Epilepsy during pregnancy is associated with increased risks Neuroscience, Karolinska Institutet,

of adverse pregnancy and perinatal outcomes. However, AED use during pregnancy is Stockholm, Sweden (Tomson);

generally not associated with adverse outcomes. Department of Women’s and

Children’s Health, Uppsala University,

Uppsala, Sweden (Wikström).

Corresponding Author: Neda Razaz,

PhD, Clinical Epidemiology Unit,

Department of Medicine Solna,

Karolinska University Hospital,

Karolinska Institutet, SE-171 76

JAMA Neurol. doi:10.1001/jamaneurol.2017.1310 Stockholm, Sweden

Published online July 3, 2017. (neda.razaz@gmail.com).

(Reprinted) E1

© 2017 American Medical Association. All rights reserved.

Downloaded From: http://archneur.jamanetwork.com/ by a University of California - San Diego User on 07/04/2017

Research Original Investigation Association Between Pregnancy and Perinatal Outcomes in Women With Epilepsy

B

etween 0.3% and 0.5% of all pregnancies occur among

women with epilepsy.1 To avoid the maternal and fe- Key Points

tal risks associated with seizures, maternal antiepilep-

Question What are the associations between maternal epilepsy,

tic drug (AED) therapy is often maintained during pregnancy, antiepileptic drug use during pregnancy, and risks of pregnancy

despite increased risk of congenital malformations and and perinatal outcomes?

adverse cognitive development in the offspring of women

Findings In this population-based cohort study including more

receiving AEDs.2,3

than 1.4 million singleton births, we found that antiepileptic drug

Follow-up studies of pregnant women with epilepsy have use during pregnancy is generally not associated with adverse

focused mainly on associations between exposure to AEDs and maternal and fetal or neonatal outcomes. However, a diagnosis of

congenital malformations and cognition of the offspring.4,5 epilepsy still implies moderately increased risks of adverse

However, pregnancy and perinatal complications among pregnancy, delivery, and perinatal outcomes.

women with epilepsy may extend beyond the effect of treat- Meaning Women with epilepsy should not be advised to

ment with AEDs. Maternal mortality has been shown to be 10 discontinue their treatment, if this is clinically indicated.

times higher in women with epilepsy than in those without the Preventive strategies aimed at mitigating the effect of maternal

disorder.6,7 Epilepsy in women could increase the risks of mis- epilepsy on pregnancy and perinatal outcomes are warranted.

carriage, preterm delivery, cesarean section, preeclampsia, and

gestational hypertension.8,9 A meta-analysis reported that, Sweden. This study was based on encrypted data, for which

among women with epilepsy, exposure to AEDs during preg- the ethics committees do not require informed consent.

nancy may increase the risks of fetal growth restriction, in-

duction of labor, postpartum hemorrhage, and admission to Maternal Epilepsy

the neonatal intensive care unit compared with those who are Maternal epilepsy was identified if it met any of the following

not exposed to AEDs.9 Still, robust evidence from population- conditions16,17: (1) an occurrence of 2 or more diagnostic codes

based studies is sparse on the association between maternal for epilepsy (ICD-9 code 345 and ICD-10 code G40) on sepa-

epilepsy and risks of adverse pregnancy outcomes and the con- rate dates or (2) an occurrence of 1 or more diagnosis codes for

tribution of AEDs to these outcomes. convulsions (ICD-9 code 780.3 and ICD-10 code R56) and 1 or

In a population-based study including more than 1.4 mil- more diagnosis codes for epilepsy among separate medical en-

lion singleton-birth infants in Sweden, we investigated the as- counters; diagnosis of convulsion had to precede that of epi-

sociations between epilepsy in pregnancy and risks of preg- lepsy. The epilepsy cohort was restricted to individuals whose

nancy and perinatal outcomes. We also investigated whether epilepsy onset occurred before their child’s birth and those with

AED use influenced the risks. active epilepsy (ie, diagnosis code for epilepsy within 10 years

prior to conception).18 We classified epilepsy as either focal

(ICD-10 codes G40.0, G40.1, and G40.2), generalized (ICD-10

code G40.3), or nonspecific (if the women could not be as-

Methods

signed to either the generalized or focal groups).

This retrospective, nationwide cohort study included all single-

ton births at 22 or more completed gestational weeks in Swe- AED Exposure

den from 1997 through 2011. Using the person-unique na- Using information from the Prescribed Drug Registry (start-

tional registration numbers of mothers and their offspring,10 ing July 1, 2005),14 we were able to define AED exposure in a

individual information was obtained from the Medical Birth subcohort of women as use of any redeemed medication be-

Register,11 which contains information on antenatal, obstet- longing to ATC class N03A (antiepileptic) from July 1, 2005,

ric, and neonatal care that is prospectively recorded on stan- to December 31, 2011. The exposure window was defined as

dardized forms on more than 98% of all births in Sweden; the 30 days before the estimated day of conception to the day of

nationwide National Patient Register,12,13 which has pro- birth.

vided diagnostic codes on hospital inpatient care since 1987

and hospital outpatient care from 2001; and the Prescribed Pregnancy and Perinatal Outcomes

Drug Registry, which stores data on all drugs prescribed in am- Pregnancy outcomes examined in this study were gestational

bulatory care and dispensed at a Swedish pharmacy since July diabetes, preeclampsia, chorioamnionitis, maternal infection,

1, 2005.14 Maternal educational level and country of origin were placental abruption, premature rupture of membranes, pro-

obtained from the Education Register15 and the Total Popula- longed labor, induction of labor, mode of delivery, and postpar-

tion Register.10 Diagnoses in these databases were coded using tum hemorrhage (eTable 1 in the Supplement reports specific

the Swedish version of the International Classification of Dis- codes).

eases, Ninth Revision (ICD-9) from 1987 through 1996, and In- Perinatal outcomes included stillbirth, preterm birth, spon-

ternational Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related taneous and medically indicated preterm birth, small-for-

Health Problems, Tenth Revision (ICD-10) from 1997 onward. gestational-age (SGA) live birth, neonatal infection, presence

Prescription medications were coded using the Drug Identifi- of congenital malformation detected during the first year of

cation Numbers and the Anatomical Therapeutic Chemical (ATC) life (divided into 2 categories: all malformations and major mal-

classification system. The study was approved by the Re- formations), asphyxia-related neonatal complications (includ-

search Ethics Committee at Karolinska Institutet, Stockholm, ing meconium aspiration, hypoxic ischemic encephalopathy

E2 JAMA Neurology Published online July 3, 2017 (Reprinted) jamaneurology.com

© 2017 American Medical Association. All rights reserved.

Downloaded From: http://archneur.jamanetwork.com/ by a University of California - San Diego User on 07/04/2017

Association Between Pregnancy and Perinatal Outcomes in Women With Epilepsy Original Investigation Research

and related conditions, and neonatal convulsions or sei- of 95% CIs, generalized estimating equations, with an

zures), 5-minute Apgar score, neonatal hypoglycemia, assumed unstructured correlation structure, were used to

neonatal jaundice, and respiratory distress (eTable 1 and account for the correlations of sequential births to the same

eTable 2 in the Supplement report specific ICD codes). The mother in the study. Models were adjusted for maternal age,

Birth Register includes live births from 22 completed gesta- country of origin, educational level, cohabitation with a

tional weeks onward. Information on stillbirths was avail- partner, parity, height, body mass index, smoking, year of

able from 28 weeks onward from 1997 to July 1, 2008, and delivery, pregestational diabetes, hypertension, and psychi-

thereafter from 22 gestational weeks. In the present study, atric disorders. Pregnancy and neonatal events were rare in

stillbirth was defined as a fetal death at 28 completed weeks the relatively small AED-treated cohort. For all analyses that

or later. included the AED-treated cohort (all births from July 1,

Gestational age in completed weeks was estimated 2005, to December 31, 2011 only), we therefore used a pro-

using the date of the early second trimester ultrasonogra- pensity score approach to optimize adjustment for the

phy (which is offered to all women; 95% accept) in 87.7% of above covariates.22 We calculated propensity scores using

the women,19 the date of the last menstrual period in 7.4% multivariable logistic regression, with exposure to AEDs as a

of the women, or postnatal assessment in 4.9% of the dependent variable and all adjustment covariates as predic-

women. Preterm birth was categorized as birth earlier than tors. To obtain adjusted estimates, the resulting propensity

37 completed weeks’ gestation. Medically indicated preterm score was entered into the Poisson log-linear regression

birth was defined as being born preterm and having an models as a continuous variable. Data were analyzed with

induced onset of labor or a cesarean section before onset of the use of SAS software, version 9.4 (SAS Institute). Two-

labor. The SGA was defined using the current Swedish stan- sided P values less than <.05 were considered to indicate

dard for normal fetal growth and categorized into less than statistical significance. No adjustment was made for mul-

the 10th percentile (SGA) and 10th percentile or higher tiple comparisons. Data analysis was performed from Octo-

(non-SGA).20 Induced abortion due to detected malforma- ber 1, 2016, to February 15, 2017.

tion at the 18 gestational weeks’ ultrasonography are legal

until 21 gestational weeks in Sweden. These pregnancies are

therefore not included in the Medical Birth Register.

Results

Other Covariates The final sample included 1 424 279 pregnancies of 869 947

Maternal characteristics included age at delivery, country of mothers without epilepsy and 5373 pregnancies of 3586 moth-

origin, educational level, cohabitation with a partner, parity, ers with epilepsy. Mean (SD) age at first delivery of the epi-

height, early pregnancy body mass index (calculated as weight lepsy cohort was 30.54 (5.18) years. During the period for which

in kilograms divided by height in meters squared), smoking we had information on AED exposure (July 1, 2005, to Decem-

during early pregnancy, year of delivery, and maternal pre- ber 31, 2011), there were 3231 offspring of mothers with epi-

existing chronic conditions, such as pregestational diabetes, lepsy, of whom 42.2% (n = 1363) were exposed to AEDs 1 month

hypertension, and any psychiatric disorders. Maternal age at before and/or during pregnancy. Lamotrigine (628 [46.1%]) and

delivery was calculated as date of delivery minus mother’s carbamazepine (418 [30.7%]) were the most commonly used

birth date. Parity was defined as the number of births of AEDs, and 181 infants (13.3%) were exposed to polytherapy

each mother. Body mass index, categorized according to the (eTable 3 in the Supplement).

World Health Organization recommendation,21 was calcu- Compared with women without epilepsy, women with

lated using weight measured at registration to antenatal epilepsy were younger at the time of delivery, primiparous,

care, wearing light indoor clothing, and self-reported born in the Nordic countries, had a lower educational level,

height. Information on cohabitation with a partner was smoked, lived without a partner, were obese (body mass

obtained at the first antenatal visit. Mothers who reported index, ≥30), and had a higher frequency of chronic condi-

daily smoking at the first antenatal visit and/or at 30 to 32 tions, such as pregestational diabetes, hypertension, psychi-

gestational weeks were classified as smokers, whereas atric diagnosis, and substance abuse (Table). Among women

mothers who only stated that they were nonsmokers were with epilepsy, those receiving AEDs during pregnancy were

classified as nonsmokers. Any psychiatric morbidity and older, more often primiparous, and born in non-Nordic

substance abuse before the child’s birth were defined using countries.

inpatient and outpatient primary or secondary diagnoses of Pregnancies in women with epilepsy were associated with

any psychiatric condition and substance abuse (eTable 1 in elevated risks of preeclampsia (aRR, 1.24; 95% CI, 1.07-1.43),

the Supplement reports specific codes). infection (aRR, 1.85; 95% CI, 1.43-2.29), placental abruption

(aRR, 1.68; 95% CI, 1.18-2.38), induction (aRR, 1.31; 95% CI,

Statistical Analysis 1.21-1.40), elective cesarean section (aRR, 1.58; 95% CI, 1.45-

Maternal characteristics of women with and without epi- 1.71), and emergency cesarean section (aRR, 1.09; 95% CI,

lepsy and those receiving and not receiving AEDs during 1.00-1.20) compared with pregnancies in women without

pregnancy were compared using logistic regression. Multi- epilepsy (Figure 1A). There was a higher frequency of post-

variable Poisson log-linear regression models were used partum hemorrhage in pregnancies of women with epilepsy

to estimate adjusted risk ratios (aRRs). For the computation compared with those without epilepsy; however, this asso-

jamaneurology.com (Reprinted) JAMA Neurology Published online July 3, 2017 E3

© 2017 American Medical Association. All rights reserved.

Downloaded From: http://archneur.jamanetwork.com/ by a University of California - San Diego User on 07/04/2017

Research Original Investigation Association Between Pregnancy and Perinatal Outcomes in Women With Epilepsy

Table. Maternal Characteristics of First Recorded Pregnancy According to Maternal Epilepsy and Maternal AED Use During Pregnancya

No. (%)

Not Receiving

No Epilepsy Epilepsy AED Receiving AED

Maternal Characteristic (n = 869 947) (n = 3586) P Value (n = 1015) (n = 926)a P Value

Age, y

≤19 23 231 (2.7) 117 (3.3) 25 (2.5) 46 (5.0)

20-24 145 625 (16.7) 655 (18.3) 178 (17.5) 189 (20.4)

25-29 291 605 (33.5) 1144 (31.9) .03 304 (30.0) 294 (31.8) .003

30-34 268 613 (30.9) 1090 (30.4) 327 (32.2) 252 (27.2)

≥35 140 873 (16.2) 580 (16.2) 181 (17.8) 145 (15.7)

Country of birth

Nordic 708 737 (81.5) 3122 (87.1) 855 (84.2) 802 (86.6)

<.001 .33

Non-Nordic 160 342 (18.4) 462 (12.9) 159 (15.7) 123 (13.3)

Data missing 868 (0.1) 2 (0.06) 1 (0.1) 1 (0.1)

Educational level, y

≤9 82 308 (9.5) 542 (15.1) 139 (13.7) 159 (17.2)

10-11 142 011 (16.3) 654 (18.2) 126 (12.4) 108 (11.7)

12 220 672 (25.4) 976 (27.2) <.001 295 (29.1) 289 (31.2)

.15

13-14 124 051 (14.3) 458 (12.8) 131 (12.9) 114 (12.3)

≥15 286 750 (33.9) 892 (24.9) 304 (30.0) 243 (26.2)

Data missing 14 155 (1.6) 64 (1.8) 20 (2.0) 13 (1.4)

Cohabiting with partner

Yes 765 720 (88.0) 3051 (85.1) 875 (86.2) 781 (84.3)

<.001 .05

No 57 110 (6.6) 357 (10.0) 109 (10.7) 96 (10.4)

Data missing 47 117 (5.4) 178 (5.0) 31 (3.0) 49 (5.3)

Parity

1 248 355 (28.6) 1305 (36.4) 800 (78.8) 743 (80.2)

2 402 479 (46.3) 1521 (42.4) 151 (14.9) 103 (11.1)

<.001 <.001

3 157 088 (18.1 540 (15.1) 43 (4.2) 58 (6.3)

≥4 62 025 (7.1) 220 (6.1) 21 (2.1) 22 (2.4)

Median (Q1-Q3) 2 (1-3) 2 (1-2) 2 (1-2) 1 (1-2)

Height, cm

≤159 113 348 (13.0) 529 (14.8) 148 (14.6) 132 (14.3)

160-164 216 959 (24.9) 910 (25.4) 234 (23.1) 248 (26.8)

.02 .37

165-169 248 109 (28.5) 970 (27.1) 287 (28.3) 245 (26.5)

≥170 269 345 (31.0) 1083 (30.2) 315 (31.0) 279 (30.1)

Data missing 22 186 (2.6) 94 (2.6) 31 (3.1) 22 (2.4)

Smoking

No 736 252 (84.6) 2911 (81.2) 879 (86.6) 757 (81.7)

<.001 <.001

Yes 90 159 (10.4) 504 (14.1) 109 (10.7) 107 (11.6)

Data missing 43 536 (5.0) 171 (4.8) 27 (2.7) 62 (6.7)

Year of delivery

1997-1999 229 581 (26.4) 561 (15.6) NA NA

2000-2004 276 078 (31.7) 1084 (30.2) NA NA

<.001

2005-2008 204 935 (23.6) 999 (27.9) 458 (45.1) 541 (58.4)

2009-2011 159 353 (18.3) 942 (26.3) 557 (54.9) 385 (41.6)

BMI

<18.5 20 758 (2.4) 81 (2.3) 26 (2.6) 22 (2.4)

18.5-24.9 493 378 (56.7) 1792 (50.0) 491 (48.4) 474 (51.2)

25.0-29.9 182 556 (21.0) 856 (23.9) 281 (27.7) 202 (21.8)

<.001 .08

30.0-34.9 54 540 (6.3) 345 (9.6) 96 (9.5) 97 (10.5)

35.0-39.9 15 822 (1.8) 101 (2.8) 32 (3.2) 28 (3.0)

≥40.0 5344 (0.6) 38 (1.1) 10 (.99) 15 (1.6)

Data missing 97 549 (11.2) 373 (10.4) 79 (7.9) 88 (9.5)

(continued)

E4 JAMA Neurology Published online July 3, 2017 (Reprinted) jamaneurology.com

© 2017 American Medical Association. All rights reserved.

Downloaded From: http://archneur.jamanetwork.com/ by a University of California - San Diego User on 07/04/2017

Association Between Pregnancy and Perinatal Outcomes in Women With Epilepsy Original Investigation Research

Table. Maternal Characteristics of First Recorded Pregnancy According to Maternal Epilepsy and Maternal AED Use During Pregnancya (continued)

No. (%)

Not Receiving

No Epilepsy Epilepsy AED Receiving AED

Maternal Characteristic (n = 869 947) (n = 3586) P Value (n = 1015) (n = 926)a P Value

Pregestational diabetes

No 866 170 (99.6) 3552 (99.1) 1003 (98.8) 914 (98.7)

<.001 .82

Yes 3777 (0.4) 34 (0.9) 12 (1.2) 12 (1.3)

Pregestational hypertension

No 864 759 (99.4) 3550 (99.0) 1002 (98.7) 915 (98.8)

.002 .85

Yes 5188 (0.6) 36 (1.0) 13 (1.3) 11 (1.2)

Any psychiatric diagnoses

No 842 149 (96.8) 3148 (87.8) 905 (89.2) 812 (87.7) .31

<.001

Yes 27 798 (3.2) 438 (12.2) 110 (10.8) 114 (12.3)

Substance misuse

No 867 095 (99.7) 3505 (97.7) 991 (97.6) 904 (97.6)

<.001 .98

Yes 2852 (0.3) 81 (2.3) 24 (2.4) 22 (2.4)

Abbreviations: AED, antiepileptic drug; BMI, body mass index (calculated as weight in kilograms divided by height in meters squared); NA, not applicable.

a

Information on AED exposure was available only during the period from July 1, 2005, to December 31, 2011. Results determined with logistic regression.

ciation was of borderline significance (aRR, 1.11, 95% CI, of major malformations (10.6%) was obtained in pregnan-

0.97-1.26). No increased risks of premature rupture of mem- cies with fetal exposure to valproic acid (eTable 3 in the

branes and prolonged labor were observed in the epilepsy Supplement).

group.

The frequency of stillbirth was higher in offspring

of women with epilepsy compared with those without epi-

lepsy (0.6% vs 0.3%) (Figure 1B). After adjustment for

Discussion

potential confounders, neonates of women with epilepsy In this nationwide cohort study, women with active epilepsy

had significantly higher risks of stillbirth, being born had higher risks of preeclampsia, maternal infection, placen-

SGA, both medically indicated and spontaneous preterm tal abruption, induction of labor, and both emergency and elec-

births, any and major congenital malformations, neonatal tive cesarean section. Offspring of women with epilepsy were

infections, asphyxia-related complications, low 5-minute at higher risks of stillbirth, both medically indicated and spon-

Apgar scores, and neonatal hypoglycemia and respiratory taneous preterm births, SGA live birth, neonatal infection, any

distress compared with neonates of unaffected women and major malformations, asphyxia-related neonatal compli-

(Figure 1B). cations, low 5-minute Apgar scores, and less severe but more

Among pregnancies in women with epilepsy who gave prevalent neonatal complications, including neonatal hypo-

birth between July 2005 and December 2011, the rate of pre- glycemia and respiratory distress. In women with epilepsy,

eclampsia was higher in those receiving AEDs compared with using AEDs during pregnancy did not increase the risks of preg-

pregnancies in women who did not receive AEDs (Figure 2A). nancy and perinatal complications significantly, except for a

However, in the propensity score–adjusted analyses, only higher rate of induction of labor.

induction of labor remained statistically significant (aRR, 1.30; Higher risks of pregnancy complications among women

95% CI, 1.10-1.55) (Figure 2A). with epilepsy have previously been reported in some6,9 but not

Offspring of women exposed to AEDs had a higher fre- all studies.23,24 In our study, we further observed increased risks

quency of major malformation (6.7% vs 4.7%), respiratory of placental abruption and maternal infection among women

distress (6.0% vs 4.5%), and being SGA (9.5% vs 6.9%) at with epilepsy compared with the unaffected women. In addi-

birth, compared with the nonexposed offspring (Figure 2B). tion, we confirmed the earlier described associations between

The propensity score–adjusted analyses showed no statisti- maternal epilepsy and higher risks of preterm birth, SGA live

cally significant increased risk of adverse neonatal out- birth, low Apgar score, and major malformation.6,9,25 The in-

comes between the 2 groups for any of the neonatal out- creased risk of stillbirth (55%) was also consistent with previ-

comes. ous studies that had supported a significant, albeit smaller, risk

Stratifying the analyses by type of AED monotherapy (1 increase.6,26 Moreover, our study showed that women with epi-

AED type during pregnancy) and polytherapy (>1 AED lepsy were more likely than women without epilepsy to have

type during pregnancy) and by gestational age (term ≥37 an infant who experienced asphyxia-related neonatal compli-

weeks vs preterm 22-36 weeks) revealed similar results, cations, neonatal hypoglycemia, and neonatal respiratory dis-

although statistical power was reduced. Among women tress. To date, few previous studies have explored the poten-

receiving relatively common monotherapy, the highest rate tial role of maternal epilepsy and the more prevalent neonatal

jamaneurology.com (Reprinted) JAMA Neurology Published online July 3, 2017 E5

© 2017 American Medical Association. All rights reserved.

Downloaded From: http://archneur.jamanetwork.com/ by a University of California - San Diego User on 07/04/2017

Research Original Investigation Association Between Pregnancy and Perinatal Outcomes in Women With Epilepsy

Figure 1. Delivery, Pregnancy, and Perinatal Outcomes Among Women With and Women Without Epilepsy,

Sweden, 1997-2011

A Pregnancy and delivery outcomes

Favors Favors

No. (%) Women Women

Without Epilepsy With Epilepsy Adjusted RR With Without

Outcome (n = 1 424 279) (n = 5373) (95% CI) Epilepsy Epilepsy

Gestational diabetes 14 015 (1.0) 69 (1.2) 1.14 (0.86-1.50)

Preeclampsia 39 964 (2.8) 214 (4.0) 1.24 (1.07-1.43)

Chorioamnionitis 2817 (0.2) 17 (0.3) 1.44 (0.87-2.39)

Maternal infection 9173 (0.6) 66 (1.2) 1.85 (1.43-2.29)

Placental abruption 5564 (0.4) 40 (0.7) 1.68 (1.18-2.38)

Premature rupture of membranes 22 160 (1.6) 97 (1.8) 1.20 (0.98-1.48)

Prolonged labor 11 072 (0.8) 40 (0.7) 0.86 (0.62-1.18)

Induced labor 155 430 (10.9) 844 (15.7) 1.31 (1.21-1.40)

Elective cesarean section 107 655 (7.6) 711 (13.2) 1.58 (1.45-1.71)

Emergency cesarean section 109 038 (7.7) 493 (9.2) 1.09 (1.00-1.20)

Postpartum hemorrhage 66 908 (4.7) 285 (5.3) 1.11 (0.97-1.26)

0 0.5 1.0 1.5 2.0 2.5 3.0 3.5 4.0

Adjusted RR (95% CI)

B Perinatal outcomes

Favors Favors

No. (%) Women Women

Without Epilepsy With Epilepsy Adjusted RR With Without

Outcome (n = 1 424 279) (n =.5373) (95% CI) Epilepsy Epilepsy

Stillbirth 4802 (0.3) 32 (0.6) 1.55 (1.05-2.30)

Preterm birth (<37 wk) 668 841 (4.7) 416 (7.7) 1.49 (1.34-1.66) Pregnancy and delivery (A) and

Medically indicated preterm birth 18 601 (1.3) 158 (2.9) 1.24 (1.08-1.43) perinatal (B) outcomes determined

Spontaneous preterm birth 48 517 (3.4) 248 (4.6) 1.34 (1.20-1.53) using multivariable Poisson log-linear

Small for gestational age 89 463 (6.3) 451 (8.4) 1.25 (1.13-1.30) regression models adjusted for

maternal age, country of origin,

Neonatal infections 21 332 (1.5) 116 (2.2) 1.42 (1.17-1.73)

educational level, cohabitation with a

Any congenital malformations 83 845 (5.9) 480 (8.9) 1.48 (1.35-1.62)

partner, parity, height, early

Major malformations 46 632 (3.3) 301 (5.6) 1.61 (1.43-1.81) pregnancy body mass index, smoking

Asphyxia-related complications 6053 (0.4) 44 (0.8) 1.75 (1.26-2.42) during pregnancy, prepregnancy

Apgar score 4–6 10 927 (0.8) 65 (1.2) 1.34 (1.03-1.76) hypertension, prepregnancy

Apgar score 0–3 2905 (0.2) 27 (0.5) 2.42 (1.62-3.61) diabetes, any psychiatric disorders,

Neonatal hypoglycemia 37 923 (2.7) 250 (4.7) 1.53 (1.34-1.75) and year of delivery. Denominator for

Neonatal jaundice 59 212 (4.2) 227 (4.2) 0.95 (0.83-1.09) stillbirth was all births at 28

completed weeks or later and the

Neonatal respiratory distress 44 729 (3.1) 282 (5.2) 1.48 (1.30-1.68)

denominator for the remaining

0 0.5 1.0 1.5 2.0 2.5 3.0 3.5 4.0 variables in the figure was live births

Adjusted RR (95% CI) at 22 completed weeks or later. RR

indicates risk ratio.

complications. Our results are in line with those of one previ- mazepine accounted for approximately 77% of the treated

ous study observing a 2-fold increased risk of respiratory dis- pregnancies, whereas valproic acid and topiramate, known to

tress in offspring of women with epilepsy.25 be associated with increased risks of malformations, were

We found that women with epilepsy who used AEDs during used in only 19.2% and 4.0% of the pregnancies, respec-

pregnancy were not at greater risk of adverse pregnancy out- tively. Nevertheless, in line with other studies, among

comes, with the exception of an increased risk of induction of women receiving relatively common monotherapy, our data

labor and a non-significantly increased risk of preeclampsia. also suggest that valproic acid poses a greater risk for major

This finding is in contrast to previous findings of higher risks malformation. Second, we utilized a previously validated

of antepartum and postpartum hemorrhage and cesarean case definition for epilepsy,16,17 rather than relying on a single

section in women with epilepsy using AEDs.9,27 Further- ICD code to identify epilepsy. Third, unlike a previous Swed-

more, unlike previous studies,25,28,29 we found no signifi- ish study,30 that used self-reported data from the Medical

cantly increased risk of adverse perinatal outcomes in off- Birth Registry, in our study, AED use in the most recent years,

spring of women with epilepsy exposed to AEDs compared was captured from the Prescribed Drug Registry. Fourth, we

with nonexposed infants (although the rates for SGA live included women with “active” epilepsy to ensure clinical rel-

birth and major malformation were borderline significant). evance, given that epilepsy is considered to be “resolved” for

Our study differs from previous studies examining the effects individuals who have remained seizure-free for the past 10

of AED exposure on pregnancy outcomes in a number of years.18 Fifth, in our study, we made comparisons between

ways. First, in this Swedish cohort, lamotrigine and carba- outcomes of women with epilepsy who were receiving AEDs

E6 JAMA Neurology Published online July 3, 2017 (Reprinted) jamaneurology.com

© 2017 American Medical Association. All rights reserved.

Downloaded From: http://archneur.jamanetwork.com/ by a University of California - San Diego User on 07/04/2017

Association Between Pregnancy and Perinatal Outcomes in Women With Epilepsy Original Investigation Research

Figure 2. Delivery, Pregnancy, and Perinatal Outcomes Among Women With Epilepsy by Antiepileptic Drug

(AED) Use During Pregnancy, Sweden, 2005-2011

A Pregnancy and delivery outcomes in epilepsy

Favors Favors

Women With Women With

No. (%) Epilepsy Epilepsy

Not Receiving Receiving AED Adjusted RR Receiving Not Receiving

Outcome AED (n = 1868) (n = 1363) (95% CI) AED Therapy AED Therapy

Gestational diabetes 27 (1.4) 23 (1.7) 0.94 (0.55-1.59)

Preeclampsia 56 (3.0) 67 (4.9) 1.39 (0.96-2.00)

Chorioamnionitis 8 (0.4) 3 (0.2) 0.41 (0.07-2.30)

Maternal infection 15 (0.8) 18 (1.3) 1.33 (0.66-2.65)

Placental abruption 12 (0.6) 7 (0.5) 0.83 (0.30-2.31)

Premature rupture of membranes 33 (1.8) 24 (1.8) 0.98 (0.56-1.74)

Prolonged labor 16 (0.9) 10 (0.7) 0.72 (0.28-1.86)

Induced labor 269 (14.4) 261 (19.1) 1.30 (1.10-1.55)

Elective cesarean section 237 (12.7) 191 (14.0) 1.02 (0.85-1.22)

Emergency cesarean section 162 (8.7) 138 (10.1) 1.03 (0.81-1.30)

Postpartum hemorrhage 95 (5.1) 90 (6.6) 1.08 (0.79-1.48)

0 0.5 1.0 1.5 2.0 2.5 3.0

Adjusted RR (95% CI)

B Perinatal outcomes in epilepsy

Favors Favors

Women With Women With

No. (%) Epilepsy Epilepsy

Not Receiving Receiving AED Adjusted RR Receiving Not Receiving

Outcome AED (n = 1868) (n = 1363) (95% CI) AED Therapy AED Therapy

Stillbirth 9 (0.5) 6 (0.4) 0.66 (0.17-2.60)

Preterm birth (<37 wk) 128 (6.9) 99 (7.3) 0.97 (0.74-1.27)

Medically indicated preterm birth 46 (2.5) 42 (3.1) 1.11 (0.77-1.61) Pregnancy and delivery (A) and

Spontaneous preterm birth 82 (4.4) 55 (4.0) 0.91 (0.73-1.15) perinatal (B) outcomes determined

using propensity score approach to

Small for gestational age 128 (6.9) 130 (9.5) 1.25 (0.97-1.61)

adjust for confounders, including

Neonatal infections 26 (1.4) 27 (2.0) 1.28 (0.78-2.45)

maternal age, country of origin,

Any congenital malformations 135 (7.2) 123 (9.0) 1.17 (0.90-1.25) educational level, cohabitation with a

Major malformations 87 (4.7) 91 (6.7) 1.30 (0.95-1.77) partner, parity, height, early

Asphyxia-related complications 10 (0.5) 5 (0.4) 0.55 (0.17-1.75) pregnancy body mass index, smoking

Apgar score 4–6 16 (0.9) 16 (1.2) 1.10 (0.48-2.51) during pregnancy, prepregnancy

Apgar score 0–3 10 (0.5) 5 (0.4) 0.60 (0.21-1.65) hypertension, prepregnancy

Neonatal hypoglycemia 72 (3.9) 65 (4.8) 1.14 (0.81-1.59) diabetes, and any psychiatric

Neonatal jaundice 87 (4.7) 54 (4.0) 0.75 (0.53-1.08) disorders. Denominator for stillbirth

was all births at 28 completed weeks

Neonatal respiratory distress 84 (4.5) 81 (6.0) 1.30 (0.92-1.81)

or later and the denominator for the

0 0.5 1.0 1.5 2.0 2.5 3.0 remaining variables in the figure was

Adjusted RR (95% CI) live births at 22 completed weeks or

later. RR indicates risk ratio.

vs those with epilepsy who were not receiving AEDs, while lepsy who are receiving AEDs during pregnancy may receive

most previous studies compared AED use in women with extra surveillance and monitoring from their clinicians that may

epilepsy with a large reference cohort of women without epi- have contributed to the comparable outcomes observed in our

lepsy, which introduces confounding by indication bias.31 study. The teratogenicity of AEDs to the developing fetus has

Finally, we were able to account for data clustering arising been of concern for women in whom discontinuation of AED

from consecutive births of the same mother and adjust for therapy during pregnancy cannot be considered owing to the

several confounding variables not considered in previous possibility of seizures. 28 Our findings reveal that the in-

studies, such as maternal preexisting chronic conditions. creased risks of complications during pregnancy, labor, and the

The physiologic changes occurring in pregnancy signifi- neonatal period might be due to pathologic factors related to

cantly alter the volume of distribution and elimination of AEDs epilepsy as a chronic disease more than being the effect of AEDs

and consequently decrease the plasma concentration.32 This per se. Such epilepsy-related factors may be associated with

action could theoretically influence the potential adverse ef- the many comorbidities of epilepsy (eg, autoimmune

fects of AEDs on maternal and perinatal outcomes, unless dose disorders).29,33 Therefore, women with epilepsy should not be

adjustments are made. The clinical recommendation in Swe- advised to discontinue clinically indicated treatment. Ad-

den is to monitor AED serum concentrations with dose adjust- verse effects of AED use have also been shown to be counter-

ment throughout the pregnancy. In addition, women with epi- balanced by the seizure control effect of AEDs.34,35

jamaneurology.com (Reprinted) JAMA Neurology Published online July 3, 2017 E7

© 2017 American Medical Association. All rights reserved.

Downloaded From: http://archneur.jamanetwork.com/ by a University of California - San Diego User on 07/04/2017

Research Original Investigation Association Between Pregnancy and Perinatal Outcomes in Women With Epilepsy

Limitations disease severity, seizure frequency during pregnancy, dosage

The main limitation of our study was that the Patient Drug Reg- of AED exposure, AED serum levels, or exposure to other po-

ister only provides information on drugs that have been dis- tential teratogens, needs to be assessed in future studies.

pensed from pharmacies, and the adherence to treatment is

unknown. However, previous research has shown high agree-

ment between maternal reports of AED use during pregnancy

and filled prescriptions for AEDs.36 We also lacked informa-

Conclusions

tion about malformations subjected to induced abortions, Our findings provide reassurance to women with epilepsy that

which may have influenced the estimated association be- AED use during pregnancy is generally not associated with ad-

tween exposure to AEDs and risk of major malformation in the verse maternal and fetal or neonatal outcomes, although it is

offspring toward the null. In our AED-exposed cohort, we important to be aware that AEDs differ in their teratogenic po-

cannot rule out the possibility of false-negative results due to tential. However, a diagnosis of epilepsy still implies a mod-

a lack of power to detect a meaningful difference. Finally, given erately increased risk of adverse pregnancy, delivery, and peri-

our nonexperimental study design, the observed associa- natal outcomes. This information should improve counseling

tions between exposure to maternal epilepsy and AEDs and for women with epilepsy who contemplate discontinuing their

pregnancy outcomes are not evidence of a causal relation- treatment during pregnancy and provide useful information

ship. The impact of other possible confounders, such as to their health care clinicians.

ARTICLE INFORMATION 2. Meador K, Reynolds MW, Crean S, Fahrbach K, 13. Swedish National Board of Health and Welfare.

Accepted for Publication: May 9, 2017. Probst C. Pregnancy outcomes in women with Quality and content in the Swedish Patient Register

epilepsy: a systematic review and meta-analysis of http://www.socialstyrelsen.se/Lists/Artikelkatalog

Published Online: July 3, 2017. published pregnancy registries and cohorts. /Attachments/19490/2014-8-5.pdf. Published

doi:10.1001/jamaneurol.2017.1310 Epilepsy Res. 2008;81(1):1-13. 2013. Accessed February 19, 2016.

Author Contributions: Dr Razaz had full access to 3. Tomson T, Battino D. Teratogenic effects of 14. Wettermark B, Hammar N, Fored CM, et al. The

all the data in the study and takes responsibility for antiepileptic drugs. Lancet Neurol. 2012;11(9):803- new Swedish Prescribed Drug Register—

the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the 813. opportunities for pharmacoepidemiological

data analysis. research and experience from the first six months.

Concept and design: Razaz, Wikström, Cnattingius. 4. Koo J, Zavras A. Antiepileptic drugs (AEDs)

during pregnancy and risk of congenital jaw and Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2007;16(7):726-735.

Acquisition, analysis, or interpretation of data: All

authors. oral malformation. Oral Dis. 2013;19(7):712-720. 15. Statistics Sweden. Evaluation of the Swedish

Drafting of the manuscript: Razaz. 5. Christensen J, Grønborg TK, Sørensen MJ, et al. register of education. http://www.scb.se/statistik

Critical revision of the manuscript for important Prenatal valproate exposure and risk of autism /_publikationer/BE9999_2006A01_BR

intellectual content: All authors. spectrum disorders and childhood autism. JAMA. _BE96ST0604.pdf. Published 2006. Accessed

Statistical analysis: Razaz. 2013;309(16):1696-1703. February 15,2016.

Obtained funding: Cnattingius. 6. MacDonald SC, Bateman BT, McElrath TF, 16. Helmers SL, Thurman DJ, Durgin TL, Pai AK,

Administrative, technical, or material support: Hernández-Díaz S. Mortality and morbidity during Faught E. Descriptive epidemiology of epilepsy in

Razaz, Cnattingius. delivery hospitalization among pregnant women the US population: a different approach. Epilepsia.

Supervision: Razaz, Cnattingius. with epilepsy in the United States. JAMA Neurol. 2015;56(6):942-948.

Conflict of Interest Disclosures: Dr Tomson is 2015;72(9):981-988. 17. Thurman DJ, Beghi E, Begley CE, et al; ILAE

associate editor of Epileptic Disorders, he has 7. Edey S, Moran N, Nashef L. SUDEP and Commission on Epidemiology. Standards for

received speaker’s honoraria to his institution from epilepsy-related mortality in pregnancy. Epilepsia. epidemiologic studies and surveillance of epilepsy.

Livanova, Eisai, UCB, and BMJ India, honoraria to his 2014;55(7):e72-e74. Epilepsia. 2011;52(suppl 7):2-26.

institution for advisory boards from UCB and Eisai, 18. Fisher RS, Acevedo C, Arzimanoglou A, et al.

and research support from Stockholm County 8. Laganà AS, Triolo O, D’Amico V, et al.

Management of women with epilepsy: from ILAE official report: a practical clinical definition of

Council, CURE, GSK, Bial, UCB, Novartis, and Eisai. epilepsy. Epilepsia. 2014;55(4):475-482.

No other disclosures were reported. preconception to post-partum. Arch Gynecol Obstet.

2016;293(3):493-503. 19. Høgberg U, Larsson N. Early dating by

Funding/Support: The study was supported by ultrasound and perinatal outcome: a cohort study.

grant 2014-0073 from the Swedish Research 9. Viale L, Allotey J, Cheong-See F, et al; EBM

CONNECT Collaboration. Epilepsy in pregnancy and Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 1997;76(10):907-912.

Council for Health, Working Life and Welfare, an

unrestricted grant from Karolinska Institutet reproductive outcomes: a systematic review and 20. Marsál K, Persson PH, Larsen T, Lilja H, Selbing

(Distinguished Professor Award to Professor meta-analysis. Lancet. 2015;386(10006):1845-1852. A, Sultan B. Intrauterine growth curves based on

Cnattingius), and grant 2014-3561 from the Swedish 10. Ludvigsson JF, Almqvist C, Bonamy AK, et al. ultrasonically estimated foetal weights. Acta Paediatr.

Research Council (Dr Wikström). Registers of the Swedish total population and their 1996;85(7):843-848.

Role of the Funder/Sponsor: The funders had no use in medical research. Eur J Epidemiol. 2016;31(2): 21. World Health Organization. Global Database on

role in the design and conduct of the study; 125-136. Body Mass Index: BMI Classification.

collection, management, analysis, and 11. Swedish National Board of Health and Welfare. http://apps.who.int/bmi/index.jsp. Published

interpretation of the data; preparation, review, or The Swedish Medical Birth Register: a summary of 2006. Accessed February 19, 2016.

approval of the manuscript; and decision to submit content and quality. http://www.socialstyrelsen.se 22. Braitman LE, Rosenbaum PR. Rare outcomes,

the manuscript for publication. /Lists/Artikelkatalog/Attachments/8306/2009 common treatments: analytic strategies using

-125-15_200912515_rev2.pdf. Published 2003. propensity scores. Ann Intern Med. 2002;137(8):

REFERENCES Accessed February 15, 2016. 693-695.

1. Viinikainen K, Heinonen S, Eriksson K, Kälviäinen 12. Ludvigsson JF, Andersson E, Ekbom A, et al. 23. Katz O, Levy A, Wiznitzer A, Sheiner E.

R. Community-based, prospective, controlled study External review and validation of the Swedish Pregnancy and perinatal outcome in epileptic

of obstetric and neonatal outcome of 179 National Inpatient Register. BMC Public Health. women: a population-based study. J Matern Fetal

pregnancies in women with epilepsy. Epilepsia. 2011;11:450. Neonatal Med. 2006;19(1):21-25.

2006;47(1):186-192.

E8 JAMA Neurology Published online July 3, 2017 (Reprinted) jamaneurology.com

© 2017 American Medical Association. All rights reserved.

Downloaded From: http://archneur.jamanetwork.com/ by a University of California - San Diego User on 07/04/2017

Association Between Pregnancy and Perinatal Outcomes in Women With Epilepsy Original Investigation Research

24. Borthen I, Eide MG, Veiby G, Daltveit AK, Gilhus EURAP epilepsy pregnancy registry. Epilepsia. 2013; 33. Ong M-S, Kohane IS, Cai T, Gorman MP, Mandl

NE. Complications during pregnancy in women 54(9):1621-1627. KD. Population-level evidence for an autoimmune

with epilepsy: population-based cohort study. BJOG. 29. Keezer MR, Sisodiya SM, Sander JW. etiology of epilepsy. JAMA Neurol. 2014;71(5):569-

2009;116(13):1736-1742. Comorbidities of epilepsy: current concepts and 574.

25. Artama M, Gissler M, Malm H, Ritvanen A; Drug future perspectives. Lancet Neurol. 2016;15(1):106- 34. Kilic D, Pedersen H, Kjaersgaard MIS, et al. Birth

and Pregnancy Group. Effects of maternal epilepsy 115. outcomes after prenatal exposure to antiepileptic

and antiepileptic drug use during pregnancy on 30. Wide K, Winbladh B, Källén B. Major drugs—a population-based study. Epilepsia. 2014;

perinatal health in offspring: nationwide, malformations in infants exposed to antiepileptic 55(11):1714-1721.

retrospective cohort study in Finland. Drug Saf. drugs in utero, with emphasis on carbamazepine 35. Tomson T, Battino D, Bonizzoni E, et al; EURAP

2013;36(5):359-369. and valproic acid: a nation-wide, population-based Study Group. Withdrawal of valproic acid treatment

26. Veiby G, Daltveit AK, Engelsen BA, Gilhus NE. register study. Acta Paediatr. 2004;93(2):174-176. during pregnancy and seizure outcome:

Pregnancy, delivery, and outcome for the child in 31. Källén B. The problem of confounding in studies observations from EURAP. Epilepsia. 2016;57(8):

maternal epilepsy. Epilepsia. 2009;50(9):2130-2139. of the effect of maternal drug use on pregnancy e173-e177.

27. Borthen I, Eide MG, Daltveit AK, Gilhus NE. outcome. Obstet Gynecol Int. 2012;2012:148616. 36. Olesen C, Søndergaard C, Thrane N, Nielsen

Obstetric outcome in women with epilepsy: doi:10.1155/2012/148616 GL, de Jong-van den Berg L, Olsen J; EuroMAP

a hospital-based, retrospective study. BJOG. 2011; 32. Patsalos PN, Berry DJ, Bourgeois BF, et al. Group. Do pregnant women report use of

118(8):956-965. Antiepileptic drugs—best practice guidelines for dispensed medications? Epidemiology. 2001;12(5):

28. Battino D, Tomson T, Bonizzoni E, et al; EURAP therapeutic drug monitoring: a position paper by 497-501.

Study Group. Seizure control and treatment the Subcommission on Therapeutic Drug

changes in pregnancy: observations from the Monitoring, ILAE Commission on Therapeutic

Strategies. Epilepsia. 2008;49(7):1239-1276.

jamaneurology.com (Reprinted) JAMA Neurology Published online July 3, 2017 E9

© 2017 American Medical Association. All rights reserved.

Downloaded From: http://archneur.jamanetwork.com/ by a University of California - San Diego User on 07/04/2017

You might also like

- Nurse ExamDocument17 pagesNurse ExamRn nadeen100% (2)

- Nej Mo A 1414838Document10 pagesNej Mo A 1414838anggiNo ratings yet

- Predictive Value of The sFlt-1:PlGF Ratio in Women With Suspected PreeclampsiaDocument10 pagesPredictive Value of The sFlt-1:PlGF Ratio in Women With Suspected PreeclampsiaIgnacio Quiroz JerezNo ratings yet

- Aspirin in The Prevention of Preeclampsia in High Risk WomenDocument11 pagesAspirin in The Prevention of Preeclampsia in High Risk WomenSemir MehovićNo ratings yet

- Does Use of Low-Molecular-Weight Heparin During Pregnancy Influence The Risk of Prolonged Labor: A Population-Based Cohort StudyDocument17 pagesDoes Use of Low-Molecular-Weight Heparin During Pregnancy Influence The Risk of Prolonged Labor: A Population-Based Cohort StudyKris AdinataNo ratings yet

- Anxiety During Pregnancy and Preeclampsia: A Case-Control StudyDocument7 pagesAnxiety During Pregnancy and Preeclampsia: A Case-Control StudyCek GuevaraNo ratings yet

- Aspirina PDFDocument11 pagesAspirina PDFmajosbptNo ratings yet

- RiskfactorretainedplacentaDocument9 pagesRiskfactorretainedplacentaDONNYNo ratings yet

- Association Between Hypertensive Disorders of Pregnancy and Later Risk of CardiomyopathyDocument8 pagesAssociation Between Hypertensive Disorders of Pregnancy and Later Risk of CardiomyopathyPujiyono SuwadiNo ratings yet

- Ner Enberg 2017Document7 pagesNer Enberg 2017Ruben Dario Choque CutipaNo ratings yet

- Articles: BackgroundDocument13 pagesArticles: BackgroundDayannaPintoNo ratings yet

- Prediction of Recurrent Preeclampsia Using First-Trimester Uterine Artery DopplerDocument6 pagesPrediction of Recurrent Preeclampsia Using First-Trimester Uterine Artery Dopplerganesh reddyNo ratings yet

- Quadrivalent HPV Vaccination and The Risk of Adverse Pregnancy OutcomesDocument11 pagesQuadrivalent HPV Vaccination and The Risk of Adverse Pregnancy OutcomesRastia AlimmattabrinaNo ratings yet

- New England Journal Medicine: The ofDocument9 pagesNew England Journal Medicine: The ofIrmagian PaleonNo ratings yet

- Antiseizure Medication Use During Pregnancy and Risk of ASD and ADHD in ChildrenDocument10 pagesAntiseizure Medication Use During Pregnancy and Risk of ASD and ADHD in Childrenmhegan07No ratings yet

- Selected Pregnancy and Perinatal Outcomes of Patients With and Without A Previous Placenta AccreteDocument2 pagesSelected Pregnancy and Perinatal Outcomes of Patients With and Without A Previous Placenta AccreteMuhammad IkbarNo ratings yet

- Kew 043Document8 pagesKew 043Firdaus Septhy ArdhyanNo ratings yet

- Joi 150159Document10 pagesJoi 150159siti hazard aldinaNo ratings yet

- General Perinatal Medicine: Oral Presentation at Breakfast 1 - Obstetrics and Labour Reference: A2092SADocument1 pageGeneral Perinatal Medicine: Oral Presentation at Breakfast 1 - Obstetrics and Labour Reference: A2092SAElva Diany SyamsudinNo ratings yet

- Jamaneurology BJRK 2022 Oi 220027 1656444956.23113Document10 pagesJamaneurology BJRK 2022 Oi 220027 1656444956.23113cikun solihatNo ratings yet

- New England Journal Medicine: The ofDocument10 pagesNew England Journal Medicine: The ofTiffany Rachma PutriNo ratings yet

- Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand - 2013 - SKR Stad - A Randomized Controlled Trial of Third Trimester Routine Ultrasound in ADocument8 pagesActa Obstet Gynecol Scand - 2013 - SKR Stad - A Randomized Controlled Trial of Third Trimester Routine Ultrasound in ADayang fatwarrniNo ratings yet

- Prevention of Preeclampsia With Aspirin: Liona - Poon@cuhk - Edu.hkDocument12 pagesPrevention of Preeclampsia With Aspirin: Liona - Poon@cuhk - Edu.hkranggaNo ratings yet

- Labour Dystocia: Risk Factors and Consequences For Mother and InfantDocument86 pagesLabour Dystocia: Risk Factors and Consequences For Mother and Infantproject rakornasNo ratings yet

- Articol TSADocument8 pagesArticol TSAFlorinaDanilaNo ratings yet

- 33873-Article Text-121761-1-10-20170831Document6 pages33873-Article Text-121761-1-10-20170831AnggaNo ratings yet

- First-Trimester Pregnancy Exposure To Venlafaxine or Duloxetine and Risk of Major Congenital Malformations: A Systematic ReviewDocument5 pagesFirst-Trimester Pregnancy Exposure To Venlafaxine or Duloxetine and Risk of Major Congenital Malformations: A Systematic Reviewjose luisNo ratings yet

- Anxiety During Pregnancy and Preeclampsia - A Case-Control StudyDocument9 pagesAnxiety During Pregnancy and Preeclampsia - A Case-Control StudyJOHN CAMILO GARCIA URIBENo ratings yet

- Aust NZ J Obst Gynaeco - 2022 - Silveira - Placenta Accreta Spectrum We Can Do BetterDocument7 pagesAust NZ J Obst Gynaeco - 2022 - Silveira - Placenta Accreta Spectrum We Can Do BetterDrFeelgood WolfslandNo ratings yet

- Draft Proof HiDocument27 pagesDraft Proof Hiqwq kjkjNo ratings yet

- Obstetric Outcomes in Pregnant Women With Seizure Disorder: A Hospital-Based, Longitudinal StudyDocument16 pagesObstetric Outcomes in Pregnant Women With Seizure Disorder: A Hospital-Based, Longitudinal Studyniluh putu erikawatiNo ratings yet

- Acetaminophen Use During Pregnancy, Behavioral Problems, and Hyperkinetic DisordersDocument8 pagesAcetaminophen Use During Pregnancy, Behavioral Problems, and Hyperkinetic DisordersAnn DahngNo ratings yet

- Cesarean Scar Defect: A Prospective Study On Risk Factors: GynecologyDocument8 pagesCesarean Scar Defect: A Prospective Study On Risk Factors: Gynecologynuphie_nuphNo ratings yet

- Etiology and Management Therapy EpilepsyDocument6 pagesEtiology and Management Therapy Epilepsyduwik indahsariNo ratings yet

- Httpbitly wsPcoIDocument6 pagesHttpbitly wsPcoIHamdah RidhakaNo ratings yet

- Prenatal Exposure To Antiseizure Medications and Risk of Epilepsy in Children of Mothers With EpilepsyDocument13 pagesPrenatal Exposure To Antiseizure Medications and Risk of Epilepsy in Children of Mothers With Epilepsyyuly.gomezNo ratings yet

- Association of Biochemical Markers With The Severity of Pre EclampsiaDocument7 pagesAssociation of Biochemical Markers With The Severity of Pre EclampsiaFer OrnelasNo ratings yet

- 29 Sumatriptan RecomendadoDocument2 pages29 Sumatriptan RecomendadoJUAN GARCIANo ratings yet

- 11 Hal 558Document4 pages11 Hal 558Aditya SanjayaNo ratings yet

- Chakravarty 2005Document8 pagesChakravarty 2005Sergio Henrique O. SantosNo ratings yet

- 10 1001@jamapsychiatry 2020 2453Document10 pages10 1001@jamapsychiatry 2020 2453Kassandra González BNo ratings yet

- Hipertensão e DM Na Gestação - Consequencia Exposição Ruido OcupacionalDocument9 pagesHipertensão e DM Na Gestação - Consequencia Exposição Ruido OcupacionalnilfacioNo ratings yet

- Heavy Prenatal Alcohol Exposure and Obstetric and Birth2023Document8 pagesHeavy Prenatal Alcohol Exposure and Obstetric and Birth2023pau.reccNo ratings yet

- Yoa 8230Document7 pagesYoa 8230FortuneNo ratings yet

- Fetal Heart Defects and Measures of Cerebral Size: Objectives Study DesignDocument8 pagesFetal Heart Defects and Measures of Cerebral Size: Objectives Study DesignAdrian KhomanNo ratings yet

- SLE in Pregnancy MedicationDocument9 pagesSLE in Pregnancy MedicationCindy AgustinNo ratings yet

- 2021 Article 1541Document6 pages2021 Article 1541bintangNo ratings yet

- A Comprehensive Analysis of Adverse ObstetricDocument7 pagesA Comprehensive Analysis of Adverse Obstetricagustin OrtizNo ratings yet

- Prevention of Preeclampsia With AspirinDocument15 pagesPrevention of Preeclampsia With AspirinDownload FilmNo ratings yet

- Role of Low Dose AspirinDocument11 pagesRole of Low Dose AspirinYudha GanesaNo ratings yet

- Jurnal CohortDocument21 pagesJurnal CohortAstri Anindita UtomoNo ratings yet

- Antipsychotic Use in Pregnancy and The Risk For Congenital MalformationsDocument9 pagesAntipsychotic Use in Pregnancy and The Risk For Congenital MalformationsRirin WinataNo ratings yet

- Good18.Prenatally Diagnosed Vasa Previa A.30Document9 pagesGood18.Prenatally Diagnosed Vasa Previa A.30wije0% (1)

- 1 s2.0 S0002937822007281 MainDocument9 pages1 s2.0 S0002937822007281 MainkrisnawatiNo ratings yet

- Video 12 PDFDocument5 pagesVideo 12 PDFAndreas NatanNo ratings yet

- Asthma in Pregnancy - Matthew C.H. Rohn, BS, and Laura Felder, MDDocument8 pagesAsthma in Pregnancy - Matthew C.H. Rohn, BS, and Laura Felder, MDFQFerdianNo ratings yet

- MidwiferyDocument8 pagesMidwiferyRiyanti Ardiyana SariNo ratings yet

- 10 3233@hab-180359Document7 pages10 3233@hab-180359Sergio Henrique O. SantosNo ratings yet

- Avitanrg RG RDocument2 pagesAvitanrg RG RPrasetio Kristianto BudionoNo ratings yet

- 5BJPCBS201005.195D20Holanda20et - Al .2C202019 PDFDocument15 pages5BJPCBS201005.195D20Holanda20et - Al .2C202019 PDFputri vinia /ilove cuteNo ratings yet

- Diabetes in Children and Adolescents: A Guide to Diagnosis and ManagementFrom EverandDiabetes in Children and Adolescents: A Guide to Diagnosis and ManagementNo ratings yet

- Kartu Hasil Studi Kartu Rencana StudiDocument2 pagesKartu Hasil Studi Kartu Rencana StudiQinthara MuftiNo ratings yet

- Kjim 2016 350Document8 pagesKjim 2016 350Qinthara MuftiNo ratings yet

- DafpusDocument3 pagesDafpusQinthara MuftiNo ratings yet

- Pembimbing Tugas Koas Bedah RSUP Persahabatan Periode 26 Agustus S.D. 2 November 2019Document2 pagesPembimbing Tugas Koas Bedah RSUP Persahabatan Periode 26 Agustus S.D. 2 November 2019Qinthara MuftiNo ratings yet

- "What Are The Effects of Moderate Drinking On Stroke Risk?": Continuing Medical EducationDocument13 pages"What Are The Effects of Moderate Drinking On Stroke Risk?": Continuing Medical EducationQinthara MuftiNo ratings yet

- OUTPUTDocument1 pageOUTPUTQinthara MuftiNo ratings yet

- Tanya Catering ServiceDocument6 pagesTanya Catering ServiceQinthara MuftiNo ratings yet

- Chest X-Ray: Oleh: Diana Octavina Preseptor: Dr. Moh. Rizal Syafe'i, SP.B-KBDDocument46 pagesChest X-Ray: Oleh: Diana Octavina Preseptor: Dr. Moh. Rizal Syafe'i, SP.B-KBDDiana OCtavinaNo ratings yet

- 19 Daftar PustakaDocument2 pages19 Daftar PustakahfniayuNo ratings yet

- FWA Prepayment Review Records Request: InstructionsDocument7 pagesFWA Prepayment Review Records Request: Instructionsabdulla.mho23No ratings yet

- Concept MapDocument3 pagesConcept Mapphelenaphie menodiado panlilioNo ratings yet

- Role of Homoeopathy in Psychological Disorders: January 2020Document6 pagesRole of Homoeopathy in Psychological Disorders: January 2020Madhu Ronda100% (1)

- @MBS - MedicalBooksStore 2018 Depression, 3rd EditionDocument150 pages@MBS - MedicalBooksStore 2018 Depression, 3rd EditionRIJANTONo ratings yet

- Facial Nerve ParalysisDocument36 pagesFacial Nerve ParalysisSylvia Diamond100% (1)

- EBP 2 Minggu PenelitianDocument23 pagesEBP 2 Minggu PenelitianMuhammad MulyadiNo ratings yet

- JSommers ONLDocument171 pagesJSommers ONLTopaz CompanyNo ratings yet

- BPQ Questionnaire PDFDocument4 pagesBPQ Questionnaire PDFAymen DabboussiNo ratings yet

- Soal No.1 Bedah DigestifDocument11 pagesSoal No.1 Bedah DigestifRaniPradnyaSwariNo ratings yet

- Veterinary Clinic Design For Earth Centre, SierraDocument22 pagesVeterinary Clinic Design For Earth Centre, SierraThamir A. HijaziNo ratings yet

- Kuliah Respirologi Anak: Divisi Respirologi Departemen Ilmu Kesehatan Anak FK Undip / Rsup DR Kariadi SemarangDocument114 pagesKuliah Respirologi Anak: Divisi Respirologi Departemen Ilmu Kesehatan Anak FK Undip / Rsup DR Kariadi SemarangLailatuz ZakiyahNo ratings yet

- Prometric-MOH PageDocument22 pagesPrometric-MOH Pageprabha.s198784No ratings yet

- RENCANA OPERASI OK IBS ORTHOPAEDI DAN TRAUMATOLOGI OKTOBER 3rdWEEKDocument1 pageRENCANA OPERASI OK IBS ORTHOPAEDI DAN TRAUMATOLOGI OKTOBER 3rdWEEKjemierudyanNo ratings yet

- Cold Stress PDFDocument2 pagesCold Stress PDFfriends_nalla100% (1)

- Wound ManagementDocument33 pagesWound Managementdr.yogaNo ratings yet

- Overview of Mucocutaneous Symptom ComplexDocument5 pagesOverview of Mucocutaneous Symptom ComplexDaphne Jo ValmonteNo ratings yet

- Food Allergy Vs Food Intolerance 1684503076Document33 pagesFood Allergy Vs Food Intolerance 1684503076Kevin AlexNo ratings yet

- Product Development Pipeline - FebruaryDocument4 pagesProduct Development Pipeline - FebruaryCebin VargheseNo ratings yet

- Home Care RN Skills ChecklistDocument2 pagesHome Care RN Skills ChecklistGloryJaneNo ratings yet

- Stunting DR AmanDocument63 pagesStunting DR AmantotoksaptantoNo ratings yet

- Filipino Family Physician 2022 60 Pages 23 29Document7 pagesFilipino Family Physician 2022 60 Pages 23 29Pia PalaciosNo ratings yet

- Oral Hygiene Index - OHI-: Jurusan Kedokteran Gigi Universitas Jenderal SoedirmanDocument55 pagesOral Hygiene Index - OHI-: Jurusan Kedokteran Gigi Universitas Jenderal SoedirmanachandrariniNo ratings yet

- Auras Epilépticas: Clasificación, Fisiopatología, Utilidad Práctica, Diagnóstico Diferencial y ControversiasDocument7 pagesAuras Epilépticas: Clasificación, Fisiopatología, Utilidad Práctica, Diagnóstico Diferencial y ControversiasMartinAnteparraNo ratings yet

- Disaster Nursing SAS Sesion 10Document8 pagesDisaster Nursing SAS Sesion 10Niceniadas CaraballeNo ratings yet

- Failed Spinal Anesthesia PDFDocument2 pagesFailed Spinal Anesthesia PDFShamim100% (1)

- Basic Clinical SkillsDocument4 pagesBasic Clinical Skillsbijuiyer5557No ratings yet

- Cam CMD 2022 Presentation SepDocument156 pagesCam CMD 2022 Presentation SepLeBron JamesNo ratings yet